Abstract

Aeschynomene indica L. has become a problematic weed in the upland direct-seeding rice fields of the lower Yangtze River region, China, leading to substantial yield reductions. A comprehensive understanding of its seed germination ecology and response to herbicides is crucial for developing effective control strategies. This study examined the effects of major environmental factors including temperature, light, pH, salt stress, osmotic potential, and burial depth on seed germination of A. indica and assessed the efficacy of 20 commonly used herbicides in rice under controlled conditions. Results revealed that germination was highly sensitive to temperature, with optimum constant and alternating temperatures of 35 °C and 40/30 °C (day/night), respectively, both achieving germination rates above 90%. The seeds were non-photoblastic, maintaining a high germination rate of 83.33% under complete darkness. Germination remained consistently high across a broad pH range from 4 to 9, with rates ranging from 83.33% to 96.67%. Salt and osmotic stresses markedly suppressed germination, with EC50 values of 195.08 mmol·L−1 NaCl and −0.43 MPa, respectively. Seedling emergence decreased significantly with increasing burial depth, with no emergence occurring at depths greater than 7 cm. The EC50 for emergence was 4.21 cm. Among the herbicides screened, saflufenacil and mesotrione were the most effective pre-emergence treatments, with GR50 values of 5.38 and 12.02 g ai ha−1, respectively. Florpyrauxifen-benzyl and fluroxypyr-meptyl exhibited the highest post-emergence activity, with GR50 values of 0.20 and 19.69 g ai ha−1, respectively. These results underscore the high ecological adaptability of A. indica to paddy fields conditions and provide a scientific foundation for integrating chemical control with cultural practices such as deep tillage into sustainable weed management systems for paddy fields.

1. Introduction

Weeds are a major biological constraint in global agricultural production, significantly reducing crop yield and quality [1]. With ongoing adjustments in agricultural planting structures and farming systems, weed species composition and community dynamics continue to evolve, posing persistent challenges to sustainable crop production [2]. Among these, Aeschynomene indica L., traditionally a weed of autumn-maturing crops, has recently emerged as a severe and problematic weed in the upland direct-seeding rice fields of the lower Yangtze River region, China [3]. Its rapid proliferation exerts substantial detrimental effects on rice (Oryza sativa L.) by competing for essential resources such as light, nutrients, and water, which ultimately hinders rice growth and reduces both grain yield and quality [4]. Furthermore, the high fecundity of A. indica, characterized by the production of abundant and readily dispersed seeds, significantly amplifies its soil se ed bank and complicates control efforts.

As an annual herbaceous plant of the Fabaceae family, A. indica exhibits strong ecological adaptability, with its life cycle (germinating in April and maturing in October) highly overlapping with that of direct-seeded rice [5,6], and its seeds possess a hard seed coat with a dormancy rate of 40–60%, which can be broken by mechanical scarification or freezing, while the soil seed bank (primarily distributed in the 0–5 cm surface layer) has a longevity of approximately 6 months, enabling persistent infestations [6,7]. Its rapid proliferation, coupled with high fecundity (producing 1000–3000 seeds per plant) and diverse dispersal pathways (via water, agricultural activities, and bird ingestion), significantly amplifies the soil seed bank and complicates control efforts [5,6]; by competing fiercely for essential resources such as light, nutrients, and water, A. indica profoundly hinders rice growth and reduces both grain yield and quality, with reported yield losses of 50% and 70% at densities of 4 plants/m2 and 8 plants/m2, respectively [3,5], and its ability to regenerate from adventitious roots after stem base damage further enhances its invasiveness [5].

The successful establishment of any weed population begins with seed germination, a critical life-stage transition profoundly influenced by environmental factors [8]. Key abiotic factors such as temperature, light, salinity, soil pH, osmotic potential, and seed burial depth are known to regulate the germination and emergence patterns of weed seeds, thereby influencing their spatial distribution and timing of infestation in agricultural fields [9,10,11]. For instance, temperature and light are primary determinants, with optimal germination thresholds and photoblastism varying considerably among species [12,13]. Additionally, factors like salt stress, osmotic stress, and burial depth can suppress germination rates and shape weed community assembly [11]. A thorough understanding of these species-specific germination requirements is, therefore, fundamental for predicting weed emergence timing and developing targeted, ecologically based management strategies [14].

In direct-seeded rice (DSR) production systems, the reliance on manual weeding has become increasingly uneconomical and unsustainable due to labor shortages, rising costs, and water constraints. Consequently, chemical weed control has emerged as the cornerstone of integrated weed management, owing to its efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and practicality [15]. However, the over-reliance and long-term application of herbicides with a single site of action readily select for herbicide-resistant weed populations, a growing global concern threatening sustainable rice production [16,17]. Therefore, proactively screening for effective herbicides against emerging weeds like A. indica and implementing sound resistance management strategies—such as herbicide rotation and tank mixtures—are essential for mitigating and delaying resistance evolution [18]. Concurrently, the implementation of Integrated Weed Management (IWM), which strategically combines chemical control with cultural practices (e.g., strategic tillage to manipulate the seed bank), biological control, and other methods, is widely advocated as the most sustainable approach for long-term weed control [16].

Despite its increasing notoriety as a paddy weed, comprehensive research on the germination biology and integrated management of A. indica remains relatively limited. A detailed understanding of its germination responses to key environmental factors prevalent in paddy fields is crucial yet understudied. Previous research on other problematic weed species, such as Cyperus difformis L. [19] and Phalaris canariensis L. field weeds [2], has demonstrated how elucidating species-specific germination ecology and population dynamics can directly inform and optimize management protocols, providing valuable models for this study.

This study was designed to elucidate the seed germination ecology of A. indica and to evaluate the efficacy of a broad spectrum of commercially available rice herbicides. The specific objectives were to: (1) systematically quantify the impact of key environmental factors—including temperature, light, pH, salt stress, osmotic potential, and burial depth—on seed germination and seedling emergence dynamics; and (2) assess the herbicidal activity of multiple pre- and post-emergence treatments to identify viable chemical control options. The resultant findings are expected to establish a critical scientific foundation for formulating sustainable Integrated Weed Management (IWM) strategies against A. indica, ultimately contributing to the mitigation of its impact and the stabilization of high yields in rice production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials

2.1.1. Tested Weed Seeds

Seeds of A. indica were collected in October 2021 from paddy fields in Xiaoxihe Town, Chuzhou City, Anhui Province, China (32.97° N, 117.68° E). After air-drying under natural conditions, they were stored in a seed storage facility at 0 to 5 °C until further use.

In accordance with the findings of Shen et al. [7], which demonstrated that freezing storage effectively breaks dormancy and enhances germination in A. indica seeds, a three-month freezing treatment at −20 °C was applied prior to the experiment to break seed dormancy. Prior to the commencement of all experiments, a standard germination test was conducted to assess seed viability. The test was performed with four replicates of 20 seeds each, placed on moist filter paper in 9 cm diameter Petri dishes. Seeds were incubated under an alternating temperature regime of 40/30 °C (day/night) with a 12 h photoperiod. The germination percentage recorded after 15 days exceeded 90% in all replicates, confirming high seed viability and justifying their use in subsequent experiments.

2.1.2. Test Herbicides

Ten pre-emergence herbicides and ten post-emergence herbicides commonly used in paddy fields were selected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Information and application rates of tested herbicides.

2.2. Test Methods

2.2.1. Seed Germination

To investigate the effects of key environmental factors on the germination of A. indica seeds, germination tests were conducted using the Petri dish method. Uniform, plump, and mature A. indica seeds were surface-sterilized with 75% ethanol and rinsed with distilled water. Two layers of filter paper were placed in 9 cm diameter Petri dishes. Twenty seeds were placed in each dish, and 10 mL of distilled water or test solution was added. Dishes were incubated in a GXZ intelligent illuminated incubator under standard conditions of 40 °C (light)/30 °C (dark), 12 h photoperiod, 75% relative humidity, and 12,000 lux light intensity. Specific temperature and photoperiod treatments deviated from these parameters. Four replicates per treatment were used, and the experiment was conducted twice. Germination was defined as radicle protrusion of approximately 2 mm. Germinated seeds were counted and recorded daily for 15 days [19].

- Experiment 1. Effect of Temperature on Germination

Two temperature regimes were tested: constant and alternating temperatures [19]. Constant temperatures: 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35 and 40 °C. Alternating temperatures: 25/15, 30/20, 30/15, 35/20, 35/25, 40/25, 40/30 °C.

- Experiment 2. Effect of Light on Germination

Five photoperiod treatments were tested: 0 h/24 h (complete darkness), 8 h/16 h, 12 h/12 h (12 h light/12 h dark alternation), 16 h/8 h, and 24 h/0 h (continuous light) [19].

- Experiment 3. Effect of pH on Germination

Buffer solutions with pH values of 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 were prepared according to Chachalis & Reddy [20]. with modifications. These solutions were added to Petri dishes containing A. indica seeds. Distilled water (pH 7.2) served as the control.

- Experiment 4. Effect of Salt Stress on Germination

NaCl solutions with concentrations of 0, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 mmol·L−1 were prepared and added to Petri dishes containing A. indica seeds [21,22].

- Experiment 5. Effect of Osmotic Potential on Germination

A graded series of polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) solutions with osmotic potentials of 0, −0.1, −0.2, −0.3, −0.4, −0.5, −0.6 and −0.8 MPa were prepared in accordance with established protocols [23]. Distilled water served as the control treatment, while concentration-to-osmotic potential conversions followed literature-standard methodologies.

- Experiment 6. Effect of Burial Depth on Germination

In contrast to the Petri dish assays simulating other environmental factors described above, seed burial depth effects on germination and emergence dynamics were assessed using pot assays [19]. Plastic pots (12 cm × 9 cm) with drainage holes were filled with test soil. Water was added from the bottom until the soil was moist. Twenty A. indica seeds were sown in each pot at depths of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 cm, with four replicates per treatment. Pots were placed in the illuminated incubator and watered from the bottom to maintain soil moisture. Other conditions were the same as in section germination seed protocol. Seedling emergence was recorded.

2.2.2. Herbicidal Activity of Common Herbicides Against A. indica

Concurrently with characterizing A. indica seed germination biology, we employed whole-plant bioassay to evaluate the efficacy of 20 conventional rice paddy herbicides for developing targeted chemical control strategies against this weed. The experiment was conducted according to the guidelines for laboratory bioassay of pesticides, utilizing the whole-plant bioassay method [24,25]. A. indica seeds were sown uniformly into plastic pots (12 cm × 9 cm) containing a nutrient soil mixture (sand: substrate = 2:1, produced by Shandong Shangdao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Jinan, China). Eight seeds were sown per pot and lightly covered with soil. Pots were bottom-watered to saturation and subsequently placed in a controlled-environment greenhouse under the following conditions: photoperiod 16 h/8 h (light/dark), temperature (35 ± 5) °C, and relative humidity 60 to 75%. Pre-emergence herbicides were applied 24 h after sowing. Post-emergence herbicides were applied at the 3- to 5-leaf stage. Spray applications were performed using an HCL-3000A motorized spray tower (Kunshan Hengchuangli Technology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) to ensure uniform coverage. A fan nozzle was positioned 50 cm above the target foliage. The spray volume was calibrated to 450 L·ha−1, delivered at a pressure of 0.275 MPa. Each treatment was replicated four times. After spraying, the weeds were placed in a greenhouse for further culture, and the symptoms of herbicide injury were observed regularly. The fresh weight of the aboveground part of the plant was measured 21 days after treatment [26,27,28,29,30].

2.3. Data Analysis and Processing

2.3.1. Seed Germination and Emergence Data Analysis

Data computation was performed using Microsoft Excel while statistical significance was determined through Duncan’s new multiple range test implemented in DPS software version 7.05. SigmaPlot version 14.0 facilitated nonlinear regression modeling of germination and emergence kinetics under three stress regimes: osmotic potential variation through NaCl gradients, matric potential manipulation, and burial depth stratification. Germination response profiles to photoperiod modulation, thermal regimes, and pH gradients were subsequently visualized using Origin version 2021.

The germination (emergence) rate calculation formula is as follows:

The nonlinear fitting formula of the effect of salt stress and water potential stress on the seed germination rate is

In the equation, G is the germination rate (%) at NaCl concentration or water potential x, Gmax is the maximum germination rate (%), x50 is the NaCl concentration or water potential at which the maximum germination rate is 50% and b is the slope of the equation.

2.3.2. Herbicide Bioassay Data Analysis

The data of the bioassay results were summarized using Excel software, and the fresh weight inhibition rate was calculated according to the fresh weight inhibition rate formula is

Here, C denotes the fresh weight of the aboveground plant part of the blank control. T indicates the fresh weight of the aboveground plant part for each treatment.

The GR50 of 20 herbicides on A. indica—defined as the dose inhibiting 50% of plant growth—was determined with SigmaPlot 14.0 using the equation:

Here, y represents the fresh weight of the aboveground plant biomass; b denotes the slope of the curve; c is the lower limit; d is the upper limit; and x0 corresponds to the herbicide dose that inhibits 50% of aboveground plant growth (GR50).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Temperature on Seed Germination

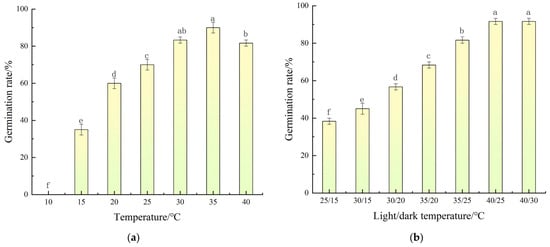

The experimental results on the effect of constant temperature conditions on the germination rate of A. indica seeds showed that under constant temperature conditions (Figure 1a), the germination rate of A. indica seeds presented an obvious increasing trend with the rise in temperature. Specifically, when the temperature increased from 10 °C to 35 °C, the seed germination rate significantly increased from 0.00% to 90.00% (an increase of 90 percentage points). At 40 °C, the germination rate slightly decreased to 81.67%, representing an 8.33% decrease relative to the optimum at 35 °C. Germination was completely inhibited at 10 °C, while even at the highest tested constant temperature (40 °C) it remained above 80%, indicating a relatively high upper thermal limit. These results demonstrate that 35 °C is the optimal constant temperature for the germination of A. indica seeds, and either excessively high or low temperature will reduce the germination rate and uniformity.

Figure 1.

Effects of constant (a) and alternating (b) temperatures on seed germination of Aeschynomene indica L. Germination rate (%) was recorded after 15 d. Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Different letters above bars indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05).

The experimental results on the effect of alternating temperature conditions on the germination rate of A. indica seeds showed that when the light/dark temperature changed from 25/15 °C to 40/30 °C, the seed germination rate showed a significant increasing trend. Specifically, the germination rate of the 25/15 °C treatment was 38.33%, while the germination rates of the 40/25 °C and 40/30 °C treatments were the highest, both being 91.67% (Figure 1b).

Collectively, these findings indicate that the optimal temperature range for A. indica seed germination lies between 30 °C and 40 °C. A constant temperature of 35 °C and the alternating regimes of 40/25 °C and 40/30 °C (day/night) were the most favorable conditions, both achieving germination rates above 90%. A. indica seed germination is not only thermophilic but also responsive to diurnal temperature fluctuations, with high-amplitude variations (particularly elevated day/night temperatures) synergistically enhancing both germination rate and uniformity.

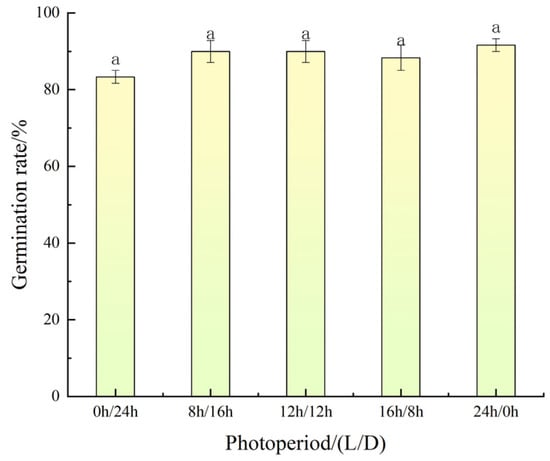

3.2. Effects of Light on Seed Germination

The results showed that A. indica seeds exhibited strong tolerance to light variations, maintaining high germination rates across all photoperiod treatments (Figure 2). Specifically, the germination rate under continuous light (24 h/0 h) was the highest at 91.67%, followed by 90.00% under 8 h/16 h and 12 h/12 h photoperiods, and 88.33% under 16 h/8 h. Even in complete darkness (0 h/24 h), the germination rate remained at 83.33%, which was not significantly lower than that under light conditions.

Figure 2.

Effect of photoperiod on the germination of A. indica seeds. Germination rate (%) was recorded after 15 d. Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Bars with the same letters are not significantly different at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

Its light insensitivity (germination rate > 83% in complete darkness) overcomes the germination constraints typical of photo dependent weeds, enabling germination within dense rice canopy shade, or at deeper soil layers. This significantly increases the difficulty of physical control measures.

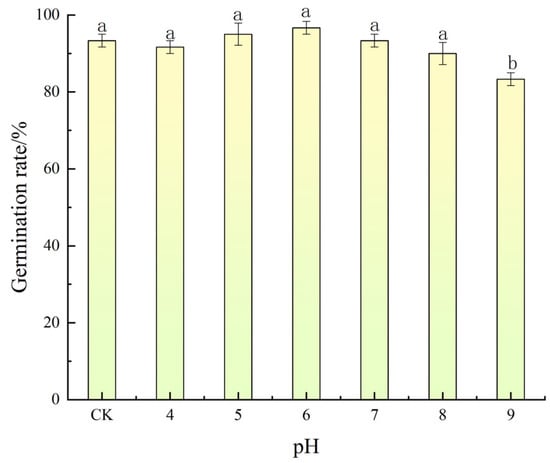

3.3. Effects of pH on Seed Germination

The germination of A. indica seeds was significantly influenced by pH levels, demonstrating a broad yet distinct tolerance range. As illustrated in Figure 3, the highest germination rate of 96.67% was observed at pH 6, indicating an optimal mildly acidic condition for germination. As the pH deviated from this optimum toward more acidic (pH 4 and 5) or alkaline conditions (pH 8 and 9), a gradual decline in germination was recorded. Specifically, at pH 9, germination decreased to 83.33%, reflecting a reduction of approximately 13.34% compared to the optimal pH. Germination remained consistently above 80% across the pH range of 4 to 9, underscoring the species’ adaptability to varying soil acidity and alkalinity.

Figure 3.

Effect of pH on the germination of A. indica seeds. Germination rate (%) was recorded after 15 d. Vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. Bars with different letters are significantly different at p < 0.05 according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

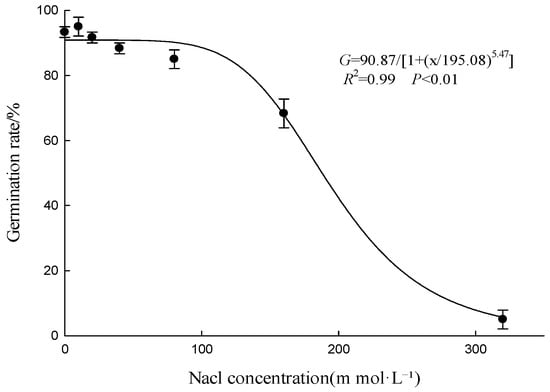

3.4. Effects of Salt Stress on Seed Germination

The germination rate of A. indica seeds was significantly influenced by salt stress (Figure 4). In the absence of salt stress (0 mmol·L−1 NaCl), the germination rate was 93.33%. As the NaCl concentration increased, the germination rate gradually decreased. For instance, at 10 mmol·L−1 NaCl, the germination rate was still relatively high at 83.33%, but it dropped to 60.00% at 80 mmol·L−1 NaCl and further to 5.00% at 320 mmol·L−1 NaCl. The nonlinear equation for the relationship between NaCl concentration and germination rate was G = 90.87/[1 + (x/195.08)5.47] (R2 = 0.99, p < 0.01), with the NaCl concentration inhibiting 50% germination rate being 195.08 mmol·L−1. Consequently, the moderate salt tolerance of A. indica implies that its proliferation may not be hindered, but rather exacerbated, in marginally saline paddies where rice vitality is reduced, presenting a heightened management challenge.

Figure 4.

Effect of salt stress on the germination of A. indica seeds. Germination rate (%) was recorded after 15 d. Points represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. The curve was fitted using a three-parameter logistic model (Equation (2)).

3.5. Effects of Osmotic Potential on Seed Germination

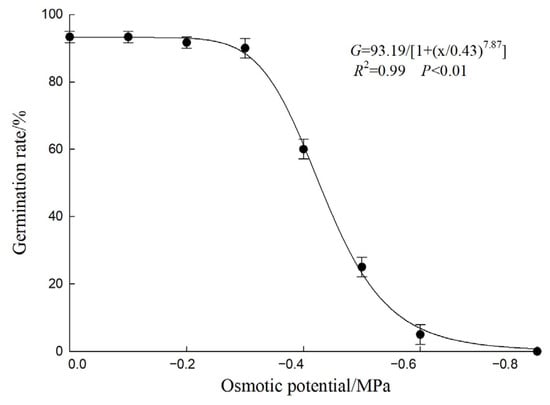

The germination rate of A. indica seeds was significantly affected by water potential (Figure 5). Under non-stress conditions (0 MPa), the germination rate was relatively high at 93.33%. As the water potential decreased, the germination rate showed a marked downward trend. Specifically, when the water potential dropped to −0.4 MPa, the germination rate significantly decreased to 60.00%; and when it further decreased to −0.6 MPa, the germination rate was extremely low at only 5.00%. The fitting curve equation for germination rate and water potential was G = 93.19/[1 + (x/0.43)7.87] (R2 = 0.99, p < 0.01), and the water potential required to inhibit 50% germination rate was −0.43 MPa.

Figure 5.

Effect of Osmotic potential on the germination of A. indica seeds. Germination rate (%) was recorded after 15 d. Points represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. The curve was fitted using a three-parameter logistic model (Equation (2)).

3.6. Effects of Burial Depth on Seed Emergence

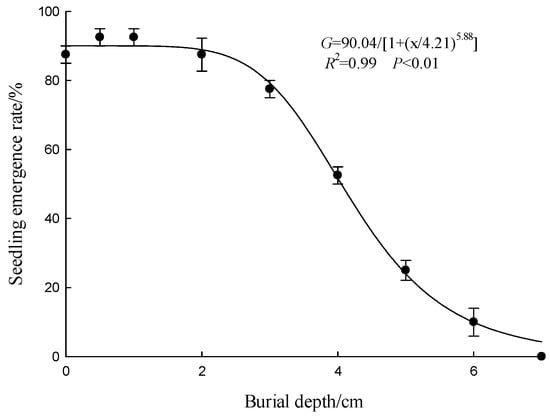

The germination and emergence rates of A. indica seeds were significantly influenced by burial depth. At shallow burial depths (0 cm and 1 cm), the emergence rates were relatively high, at 87.50% and 92.50%, respectively. As the burial depth increased to 2 cm and 3 cm, the emergence rates slightly decreased but remained substantial, at 87.50% and 77.50%, respectively. However, when the burial depth reached 4 cm and above, the emergence rates sharply declined to 52.50% at 4 cm, 25.00% at 5 cm, 10.00% at 6 cm, and nearly zero at 7 cm. The nonlinear equation for sowing depth and germination rate was G = 90.04/[1 + (x/4.21)5.88] (R2 = 0.98, p < 0.01). The emergence rate of A. indica seeds decreased sharply with increasing sowing depth, with the burial depth inhibiting 50% germination rate being 4.21 cm (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of burial depth on the germination of A. indica seeds Emergence rate (%) was recorded. Points represent the mean, and vertical bars represent ± standard error of the mean. The curve was fitted using a three-parameter logistic model (Equation (2)).

3.7. Herbicidal Activity Against A. indica

Screening of twenty herbicides against A. indica showed pronounced differences in efficacy between pre-emergence (Table 2) and post-emergence (Table 3) applications. The activity of all herbicides was further quantified by GR50 values (Table 4).

Table 2.

Fresh weight inhibition rate of pre-emergence herbicides on Aeschynomene indica L. in paddy field.

Table 3.

Fresh weight inhibition rate of post-emergence herbicides on A. indica in paddy field.

Table 4.

Effects of 20 Herbicides on A. indica Bioactivity.

Pre-emergence herbicides showed varying levels of control. At the recommended field rate, fresh weight inhibition ranged from 59.03% (acetochlor) to 97.04% (saflufenacil). Saflufenacil and mesotrione exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects, with inhibition rates of 97.04% and 87.96%, respectively, at their recommended doses. The GR50 values for pre-emergence herbicides ranged from 5.38 g ai ha−1 (saflufenacil) to 386.72 g ai ha−1 (butralin), indicating a wide spectrum of efficacy. Saflufenacil was the most potent, followed by mesotrione (GR50 = 12.02 g ai ha−1), while butralin and pendimethalin required substantially higher doses to achieve 50% growth inhibition.

Considerable variation was also observed in the control efficacy of post-emergence herbicides against A. indica. Florpyrauxifen-benzyl showed exceptional efficacy, with a GR50 of only 0.20 g ai ha−1 and a maximum inhibition rate of 90.59% at the highest tested dose (3.38 g ai ha−1). Fluroxypyr-meptyl was also highly effective, with a GR50 of 19.69 g ai ha−1 and 87.78% inhibition at the recommended rate. In contrast, MCPA-sodium and bentazone showed moderate activity, with GR50 values of 95.16 and 74.34 g ai ha−1, respectively. Among the ALS inhibitors, ethoxysulfuron had the lowest GR50 (1.97 g ai ha−1), while bensulfuron-methyl and penoxsulam also showed strong activity with GR50 values of 5.27 and 3.09 g ai ha−1, respectively.

These results highlight saflufenacil and mesotrione as the most effective pre-emergence options, and florpyrauxifen-benzyl and fluroxypyr-meptyl as the top post-emergence candidates for controlling A. indica in paddy fields.

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Environmental Factors on Seed Germination

The germination ecology of A. indica reveals a species highly adapted to the warm, fluctuating, and often stressful conditions of paddy fields. Temperature plays a crucial role in regulating weed seed germination by influencing the physiological and biochemical processes within seeds, which affects the germination rate and final germination percentage [31]. A. indica exhibits a temperature-dependent germination response, similar to Dinebra retroflexa (Vahl) Panzer and Ludwigia prostrata Roxb.; alternating temperature regimes enhance germination compared to constant conditions, suggesting thermal fluctuations break dormancy and stimulate germination in many weeds [32,33]. Optimal germination percentage and short time to 50% germination (T50) at elevated temperatures are consistent with thermophilic species like Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv. and C. difformis, indicating a shared adaptive strategy among annual weeds to warm and variable environment [19,31]. Extreme high and low temperatures can suppress germination, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved mechanism to avoid unfavorable conditions [34].

Alternating temperatures can increase germination and emergence by influencing endogenous hormones and enzyme activities in seeds [35]. Studies on Echinochloa P. Beauv. species show the influence of varying temperatures, light, osmotic, and saline conditions, and depth of seed burial on germination and seedling emergence [31]. Echinochloa crus-galli var. crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv., Echinochloa crus-galli var. mitis (Pursh) Petermann, and Echinochloa glabrescens Munro ex Hook. f. display interspecific and intraspecific differences in seed germination responses to different temperatures [36]. For instance, Eclipta prostrata (L.) L. exhibits greater germination under alternating temperatures, which is crucial for developing integrated weed management strategies [37].

Its light insensitivity (germination rate > 83% in complete darkness) overcomes the germination constraints typical of photodependent weeds, enabling germination within dense rice canopy shade or at deeper soil layers. This significantly increases the difficulty of physical control measures. The high germination rate in darkness is consistent with other problematic weeds in rice fields, such as E. crus-galli and C. difformis, which also exhibit facultative photoblastism or light-independent germination, enabling them to thrive in flooded and shaded environments [12,13].

Substantial research confirms that seeds of many pernicious weeds exhibit strong adaptability to varying soil pH levels. A. indica conforms to this trait, maintaining germination capability across a pH range of 4 to 9. For instance, Chauhan and Johnson [12] reported that Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M. King & H. Rob. and Tridax procumbens L. maintained high germination rates across a pH spectrum of 4 to 10, facilitating their invasion in tropical agroecosystems. Similarly, Nosratti et al. [9] observed that Centaurea balsamita Lam. germination was not significantly inhibited within pH 5–8, underscoring the ecological advantage of pH-insensitive germination in weed species. The ability of A. indica to germinate under both acidic and alkaline conditions may be attributed to physiological mechanisms such as ion homeostasis and enzyme stability, which allow seed metabolism to proceed under suboptimal pH conditions [38,39].

Moderate tolerance to salt (EC50 = 195.08 mmol L−1 NaCl) and osmotic stress (EC50 = −0.43 MPa) further underscores its ecological resilience. The results demonstrate that A. indica seed germination is moderately sensitive to osmotic stress, with germination being severely limited beyond −0.4 MPa. The EC50 value of −0.43 MPa is comparable to that reported for other troublesome weed species commonly found in agro-ecosystems, such as Digitaria insularis (L.) Mez ex Ekman (EC50 ≈ −0.4 to −0.5 MPa) and Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. [12,40]. This level of tolerance allows A. indica to germinate effectively under the fluctuating moisture conditions typical of paddy fields, where soil water potential may frequently drop but rarely reaches extremes for prolonged periods. However, the sharp decline in germination under moderate stress suggests that strategies which induce temporary soil moisture stress could be integrated into management programs to reduce A. indica emergence. For instance, careful water management practices, such as intermittent drying (AWD—alternate wetting and drying), could be explored as a cultural control tactic to suppress its germination without significantly impacting rice growth.

The response pattern of A. indica seeds to salt stress is similar to that of other common paddy weeds such as E. crus-galli and Leptochloa chinensis (L.) Nees, which also maintain considerable germination capacity under moderate salt stress, reflecting their strong ecological adaptability [12,33]. High salinity inhibits germination primarily by inducing osmotic stress and ion toxicity, which impede water uptake and disrupt enzymatic activities within the seeds [41]. The ability of A. indica to sustain germination under saline conditions may be associated with its origin in habitats characterized by seasonal flooding and fluctuating salinity. This adaptability suggests that A. indica could remain a potential weed threat even in mildly salinized paddy fields.

The inverse relationship between burial depth and seedling emergence is a common phenomenon in weeds, primarily due to the limited energy reserves within seeds, which are insufficient to support hypocotyl elongation through excessive soil layers. The rapid decline in A. indica emergence beyond 3 cm depth, with a complete lack of emergence from 7 cm, aligns closely with the pattern observed in many small-seeded broadleaf weeds. For instance, similar studies on Amaranthus retroflexus L. and Chenopodium album L. have shown near-complete suppression of emergence at depths of 5–8 cm [10,42].

This profound suppression of emergence at deeper layers has critical implications for integrated weed management (IWM). Firstly, it suggests that deep tillage operations, which bury seeds below their maximum emergence depth (≥7 cm), could be a highly effective cultural practice for depleting the surface seed bank of A. indica over time. Conversely, the high emergence from shallow depths (0–2 cm) indicates that no-till or reduced-till systems could favor the proliferation of this weed if not combined with effective pre-emergence herbicides or stale seedbed techniques. Therefore, these results advocate for an integrated management system that combines deep tillage (≥7 cm) to deplete the seed bank with targeted herbicide use to sustainably manage A. indica populations.

4.2. Herbicide Efficacy and Integrated Management Recommendations

The screening of 20 herbicides identified several highly effective chemical options. Among pre-emergence treatments, the PPO-inhibitor saflufenacil (GR50 = 5.38 g ai ha−1) and the HPPD-inhibitor mesotrione (GR50 = 12.02 g ai ha−1) were the most potent. Their mechanisms of action—inducing rapid oxidative damage and bleaching, respectively [43,44]—prove highly effective against A. indica.

For post-emergence control, the synthetic auxins florpyrauxifen-benzyl (GR50 = 0.20 g ai ha−1) and fluroxypyr-meptyl (GR50 = 19.69 g ai ha−1) exhibited exceptional activity. Florpyrauxifen-benzyl, in particular, has demonstrated broad-spectrum efficacy in rice [45], and its extreme potency against A. indica makes it a valuable tool for resistance management.

In contrast, the moderate efficacy of several ALS-inhibiting herbicides (e.g., bensulfuron-methyl, ethoxysulfuron) is a point of concern, given the widespread history of ALS-inhibitor resistance in global weed populations [46]. This underscores the risk of selecting for resistant A. indica biotypes under continuous use.

Based on these findings, a staged Integrated Weed Management (IWM) program is proposed for the sustainable control of A. indica:

- Pre-Planting (Cultural Seedbank Depletion): Implement deep tillage (to depths > 7 cm) after harvest or before land preparation. This buries freshly shed seeds below their maximum emergence depth, providing long-term cultural suppression of the soil seed bank.

- Crop Establishment (Preventive Chemical Barrier): At rice planting, apply a residual pre-emergence herbicide (e.g., saflufenacil or mesotrione) to create a chemical barrier in the soil, controlling the first and most critical flush of seedlings.

- Early-Mid Season (Corrective Control, if needed): For any established weed escapes, use a high-efficacy post-emergence herbicide (e.g., florpyrauxifen-benzyl) for targeted rescue control.

- Long-Term Sustainability (Resistance Management): To preserve herbicide efficacy, rotate sites of action and use tank mixtures across seasons. This chemical strategy should be integrated with the periodic use of deep tillage in a multi-year management plan [47].

5. Conclusions

This study elucidates the ecological traits that contribute to the success of A. indica as a paddy weed: high-temperature optimum, light-insensitive germination, broad pH tolerance, and moderate resilience to salt and osmotic stress. Crucially, its inability to emerge from burial depths ≥ 7 cm presents a key vulnerability.

Chemically, saflufenacil and mesotrione are identified as the most effective pre-emergence herbicides, while florpyrauxifen-benzyl and fluroxypyr-meptyl are the top candidates for post-emergence control.

For sustainable management, an integrated approach is recommended. This should commence with deep tillage to suppress the seed bank, followed by the application of a robust pre-emergence herbicide. Subsequent post-emergence applications should be made using high-efficacy herbicides with diverse modes of action. This strategy is particularly suited for dry direct-seeded rice systems, where early weed competition is intense and reliance on pre-emergence herbicides is critical. Adherence to this strategy, which combines cultural and chemical tactics, is essential for mitigating the impact of A. indica, managing resistance risks, and ensuring the long-term productivity of rice cropping systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C. and Y.B.; methodology, K.C. and Y.B.; software, Y.S. and M.F.; validation, K.C. and R.C.; formal analysis, K.C. and Y.S.; investigation, K.C. and R.C.; resources, Z.W. and Y.B.; data curation, K.C. and M.F.; writing—original draft, K.C. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, K.C., W.L., Z.W. and Y.B.; visualization, K.C. and R.C.; supervision, W.L., Z.W. and Y.B.; project administration, K.C.; funding acquisition, Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1400501) and this research was supported by the Anhui Provincial Academician Workstation, Filing Document No.: WKCM [2024] 369 (Collaborating Academician: PAN Canping, Russian Academy of Engineering).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Singh, M.; Kukal, M.S.; Irmak, S.; Jhala, A.J. Water Use Characteristics of Weeds: A Global Review, Best Practices, and Future Directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 794090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorner, Z.; Kovács, E.B.; Iványi, D.; Zalai, M. How the Management and Environmental Conditions Affect the Weed Vegetation in Canary Grass (Phalaris canariensis L.) Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, T.; Long, J.; Shen, G.; Tian, Z. Complete Chloroplast Genome and Comparison of Herbicides Toxicity on Aeschynomene indica (Leguminosae) in Upland Direct-Seeding Paddy Field. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korav, S.; Dhaka, A.; Singh, R.; Reddy, C. A Study on Crop Weed Competition in Field Crops. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 3235–3240. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.B.; Agostinetto, D.; Fogliatto, S.; Vidotto, F.; Andres, A. Aeschynomene spp. Identification and Weed Management in Rice Fields in Southern Brazil. Agronomy 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.B.; Munhos, T.F.; Schaedler, C.E.; Agostinetto, D.; Andres, A. Seed Dynamics of Aeschynomene denticulata and Aeschynomene indica. Weed Biol. Manag. 2021, 21, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.H.; Zeng, B.; Shi, M.F.; Liu, J.H.; Ayiqiaoli. Effects of Storage Condition and Duration on Seed Germination of Four Annual Species Growing in Water-Level-Fluctuation Zone of Three Gorges Reservoir. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2010, 30, 6571–6580. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhao, L. Response of Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) to Drought, Salinity, and pH in Karst Regions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratti, I.; Soltanabadi, S.; Honarmand, S.J.; Chauhan, B.S. Environmental Factors Affect Seed Germination and Seedling Emergence of Invasive Centaurea balsamita. Crop Pasture Sci. 2017, 68, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Macchia, M.; Miele, S. Light, Temperature and Burial Depth Effects on Rumex obtusifolius Seed Germination and Emergence. Weed Res. 2001, 41, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya-Altop, E.; Uysal, M.S.; Haghnama, K.; Mennan, H. Environmental Factors on Seasonal Germination of Different Weedy Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Biotypes. Ciênc. Rural 2023, 53, e20210728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Johnson, D.E. Germination Ecology of Two Troublesome Asteraceae Species of Rainfed Rice: Siam Weed (Chromolaena odorata) and Coat Buttons (Tridax procumbens). Weed Sci. 2008, 56, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.A.A.; Awan, T.H.; Cruz, P.C.S.; Chauhan, B.S. Influence of Environmental Factors, Cultural Practices, and Herbicide Application on Seed Germination and Emergence Ecology of Ischaemum rugosum Salisb. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, W.E. Exploiting Weed Seed Dormancy and Germination Requirements through Agronomic Practices. Weed Sci. 1995, 43, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Begum, M.; Rahman, M.; Akanda, M. Weed Management on Direct-Seeded Rice System—A Review. Progress. Agric. 2016, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, C.; Storkey, J.; Menegat, A.; Metcalfe, H.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K. An Ecological Future for Weed Science to Sustain Crop Production and the Environment. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L.; Streck, N.A.; Zanon, A.J.; Ribas, G.G.; Fruet, B.L.; Ulguim, A.R. Surveys of Weed Management on Flooded Rice Yields in Southern Brazil. Weed Sci. 2022, 70, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaragama, D.I.; Willenborg, C.J.; Shirtliffe, S.J.; Gulden, R.H. Revisiting Cropping Systems Research: An Ecological Framework towards Long-Term Weed Management. Agric. Syst. 2024, 213, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Chai, K.; Fida, M.; Fang, B.; Wang, K.; Bi, Y. Germination Biology of Three Cyperaceae Weeds and Their Response to Pre- and Post-Emergence Herbicides in Paddy Fields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachalis, D.; Reddy, K.N. Factors Affecting Campsis Radicans Seed Germination and Seedling Emergence. Weed Sci. 2000, 48, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; deSouza, L.L.; Yang, P.; Sosnoskie, L.; Hanson, B.D. Differential Tolerance of Glyphosate-Susceptible and Glyphosate-Resistant Biotypes of Junglerice (Echinochloa colona) to Environments during Germination, Growth, and Intraspecific Competition. Weed Sci. 2018, 66, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Hembree, K.J.; Shrestha, A. Biology, Germination Ecology, and Shade Tolerance of Alkaliweed (Cressa truxillensis) and Its Response to Common Postemergence Herbicides. Plants 2023, 12, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, B.E. Evaluation of the Water Potentials of Solutions of Polyethylene Glycol 8000 Both in the Absence and Presence of Other Solutes. Plant Physiol. 1983, 72, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NY/T 1155.3-2006; Pesticides Guidelines for Laboratory Bioactivity Tests Part 3: Soil Spray Application Test for Herbicide Bioactivity. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- NY/T 1155.4-2006; Pesticides Guidelines for Laboratory Bioactivity Tests Part 4: Foliar Spray Application Test for Herbicide Activity. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Park, H.-H.; Lee, D.-J.; Kuk, Y.-I. Effects of Various Environmental Conditions on the Growth of Amaranthus patulus Bertol. and Changes of Herbicide Efficacy Caused by Increasing Temperatures. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Ma, H.; Wei, S.; Lan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Huang, H.; Huang, Z. First Report of the Molecular Mechanism of Resistance to Tribenuron-Methyl in Silene conoidea L. Plants 2022, 11, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Leng, Q.; Su, W.; Sun, L.; Li, Q.; Wei, H.; Cheng, J.; Lu, C.; Wu, R. The Synergistic Effect and Mechanism of Different Adjuvants on Pinoxaden Efficacy against Lolium multiflorum Lam. Crop Prot. 2024, 184, 106844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtourou, M.; Osuna, M.D.; Vázquez-García, J.G.; De Prado, R.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Marín, G.M.; Hada, Z.; Souissi, T.; Torra, J. Several Point Mutations and Metabolism Confer Cross-Resistance to ALS-Inhibiting Herbicides in Tunisian Wild Mustard. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 225, 110043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Feng, Z.; Dong, L. Auxin Response Factor 3 (EcARF3) Regulates Ethylene and ABA Biosynthesis and Is Involved in Resistance to Synthetic Auxin Herbicides in Echinochloa crus-galli. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 312, 144172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Gao, Y.; Fang, J.; Shen, G.; Tian, Z. Environmental Influences on Seed Germination and Seedling Emergence in Four Echinochloa Taxa. Agronomy 2025, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, S.; Sharma, K.; Chauhan, B.S. Germination Responses of Vipergrass (Dinebra retroflexa) to Environmental Factors and Herbicide Options for Its Control. Weed Sci. 2023, 71, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Qian, H.; Yuan, G.; Fan, J.; Guo, S. Germination Ecology and Response to Herbicides of Ludwigia prostrata and Their Implication for Weed Control in Paddy Fields. Weed Technol. 2023, 37, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, H.; You, Q.; Cao, R.; Sun, G.; Yu, D. Jasmonate-Regulated Seed Germination and Crosstalk with Other Phytohormones. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 1162–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozden, E.; Light, M.E.; Demir, I. Alternating Temperatures Increase Germination and Emergence in Relation to Endogenous Hormones and Enzyme Activities in Aubergine Seeds. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 139, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Masoom, A.; Huang, Z.; Xue, J.; Chen, G. Interspecific and Intraspecific Differences in Seed Germination Response to Different Temperatures of Three Echinochloa Rice Weeds: A Case Study with 327 Populations. Weed Sci. 2025, 73, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lai, X.; Gu, T.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z. Seed Germination Ecology of Eclipta (Eclipta prostrata) in Dry Direct-Seeded Rice Fields from China. Weed Sci. 2025, 73, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Sarma, N.; Sarma, G.; Borthakur, U. Effects of Soil pH Stress on Plant Development: From Seed Germination to Early Seedling Growth. Afr. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 6, 3461–3473. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş, H.; Szpicer, A.; Strojny-Cieślak, B.; Borucki, W.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Kurek, M.A. Molecular Interplay between Plant Proteins and Polyphenols: pH as a Switch for Structural and Functional Assembly. Foods 2025, 14, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreja, F.H.; De La Fuente, E.B.; Fernandez-Duvivier, M.E. Response of Digitaria insularis Seed Germination to Environmental Factors. Crop Pasture Sci. 2017, 68, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranal, M.A.; Santana, D.G.D. How and Why to Measure the Germination Process? Rev. Bras. Bot. 2006, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Johnson, D.E. Seed Germination Ecology of Portulaca oleracea L.: An Important Weed of Rice and Upland Crops. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2009, 155, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.; Hutzler, J.; Caspar, G.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Brommer, C.L. Saflufenacil (KixorTM): Biokinetic Properties and Mechanism of Selectivity of a New Protoporphyrinogen IX Oxidase Inhibiting Herbicide. Weed Sci. 2011, 59, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, F.E.; Barker, A.; Tranel, P.J. Origins and Structure of Chloroplastic and Mitochondrial Plant Protoporphyrinogen Oxidases: Implications for the Evolution of Herbicide Resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 2226–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Norsworthy, J.K. Florpyrauxifen-Benzyl Weed Control Spectrum and Tank-Mix Compatibility with Other Commonly Applied Herbicides in Rice. Weed Technol. 2018, 32, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckie, H.J.; Tardif, F.J. Herbicide Cross Resistance in Weeds. Crop Prot. 2012, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Ward, S.M.; Shaw, D.R.; Llewellyn, R.S.; Nichols, R.L.; Webster, T.M.; Bradley, K.W.; Frisvold, G.; Powles, S.B.; Burgos, N.R.; et al. Reducing the Risks of Herbicide Resistance: Best Management Practices and Recommendations. Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).