Abstract

The species Caesalpinia spinosa, is a native forest tree of the Andes, which has multiple and valuable uses. In this study, a total of 39 guarango accessions from INIAP´s Gene Bank collection, were evaluated to determine their morphological and ecogeographical diversity. Seventeen quantitative and seven qualitative descriptors were used to characterize morphologically seeds and trees. Multivariate analyses revealed four morphological groups mainly differentiated by seed germination, viability rates, total tree height, and seed and leaflet dimensions, whereas descriptors such as seed color, shape and hilum position, presence of spines, and stem color were not discriminant. On the other hand, ecogeographical characterization, based on 21 bioclimatic, edaphic, and geophysical variables, identified six groups distributed latitudinally along the Ecuadorian Andes. A lack of significant correlation between morphological and ecogeographical variation (Mantel test) was found, suggesting that phenotypic expression is shaped by independent genetic and environmental drivers. This research is the first comprehensive morphological and ecogeographical characterization of the species in Ecuador. This new information will strengthen in situ and ex situ conservation efforts as well as promote the sustainable use of the species in the near future.

1. Introduction

The species Caesalpinia spinosa, also known as Tara spinosa (Feuillée ex Molina) Britton & Rose, is a native forest tree of the Andes [1]. It is a perennial species currently in the early stages of domestication, and therefore mainly exploited in situ [2,3]. Its distribution ranges from 4° N to 32° S, from Venezuela to northern Chile, at elevations between 1500 and 3200 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.) [4,5]. It is known by several common names, including guarango, campeche or vainillo in Ecuador; tara or taya in Peru and Bolivia; and dividivi in Colombia [6].

According to Mancero [7], guarango is a hardy and plastic species capable of adapting to a wide range of climatic conditions and thrives on shallow, dry and low-fertility soils. It has multiple uses since its fruits (pods and seeds) are highly valued. The tannins contained in its pods are used by the leather tanning industry as a natural substitute for chromium (Cr), a highly polluting element that poses serious health risks to humans and animals [8,9,10,11,12]. Additionally, it is an excellent pollen and nectar producer and can be incorporated into agroforestry systems [13]. Because of its economic potential, C. spinosa has also been cultivated commercially in several Andean countries [14].

In Ecuador, populations of guarango have been disappearing because most natural stands have been cut down, largely due to the lack of knowledge about its properties and uses and the absence of a local market [15]. The remaining wild trees are mostly found in remote, difficult-to-access areas with irregular topography [16]. Considering the ecological, economic, and cultural importance of guarango, it is essential to implement strategies to promote its conservation, sustainable cultivation, integration of traditional knowledge and value addition at the level of smallholders; otherwise, the species will continue to face genetic erosion [17,18].

Morphological characterization enables the identification of traits useful for taxonomic differentiation of plants using defined descriptors [19]. It has been widely used to assess genetic diversity for breeding and conservation purposes, given that some traits are highly heritable, easily observable, and consistently expressed across environments [20,21]. For guarango, more than 20 qualitative and quantitative descriptors have been identified for seed, fruit, seedling, and tree traits [22,23]. It is important to note that studies on the morphological characterization of guarango populations exist in Peru but not for Ecuador; these types of study contribute significantly to the understanding of its intraspecific variability and are crucial for establishing effective management and conservation strategies [2,22,23,24,25,26].

On the other hand, ecogeographical characterization involves the analyses of the environmental information of sites where a plant species develops, as it is closely linked to its adaptive processes to both biotic and abiotic factors [27]. An ecogeographical study, therefore, consists of collecting and synthesizing taxonomic, geographic, and ecological data. Characterizing ecogeographically a set of germplasm accessions allows assigning bioclimatic, geophysical, and edaphic information to each collection site. Such results can guide the prioritization of collecting and conservation strategies for any species [28].

Studies on the influence of edaphic and climatic factors on the natural remnants of guarango in tropical mountain forests are scarce. In Ecuador, examples include modeling of potential distribution [29]; analysis of geo-ecological factors influencing the distribution of forest species [30]; and evaluation of the response of native species to drought conditions [31]. However, these studies have been conducted only at the canton level of one province (Loja). This has resulted in the absence of an integrated evaluation that captures the environmental heterogeneity and spatial variability across the full ecological range of C. spinosa in the Ecuadorian Andes. On the other hand, regional studies conducted in Peru have explored the ecophysiological responses of the species to abiotic constraints [32], its altitudinal distribution and biotype differentiation [25], as well as taxonomic, ecological, and phylogenetic dimensions [33]. Then, in contrast to regional studies in Peru, a comprehensive morphological and ecogeographical characterization across the entire Andean region of Ecuador is lacking, limiting conservation and use strategies.

The combination of morphological features with bioclimatic, geophysical, and edaphic characteristics of collection sites can provide insights into the genetic diversity present within a given area [34]. This integration, facilitated by Geographic Information Systems (GIS), enhances diversity monitoring, understanding of plant evolution and the development of more effective conservation strategies [27,35].

Therefore, this study aimed to identify patterns of morphological and ecogeographical diversity and their interaction, within the national collection of guarango conserved at INIAP’s gene bank (Ecuador). We hypothesized that (i) accessions exhibit morphological differentiation linked to their ecogeographical origin and (ii) environmental gradients influence phenotypic expression, even under uniform management. These hypotheses would help to understand how environmental variability shapes intraspecific diversity in arid-land legumes, and in the selection of genotypes with potential for restoration, domestication, and sustainable production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genetic Material

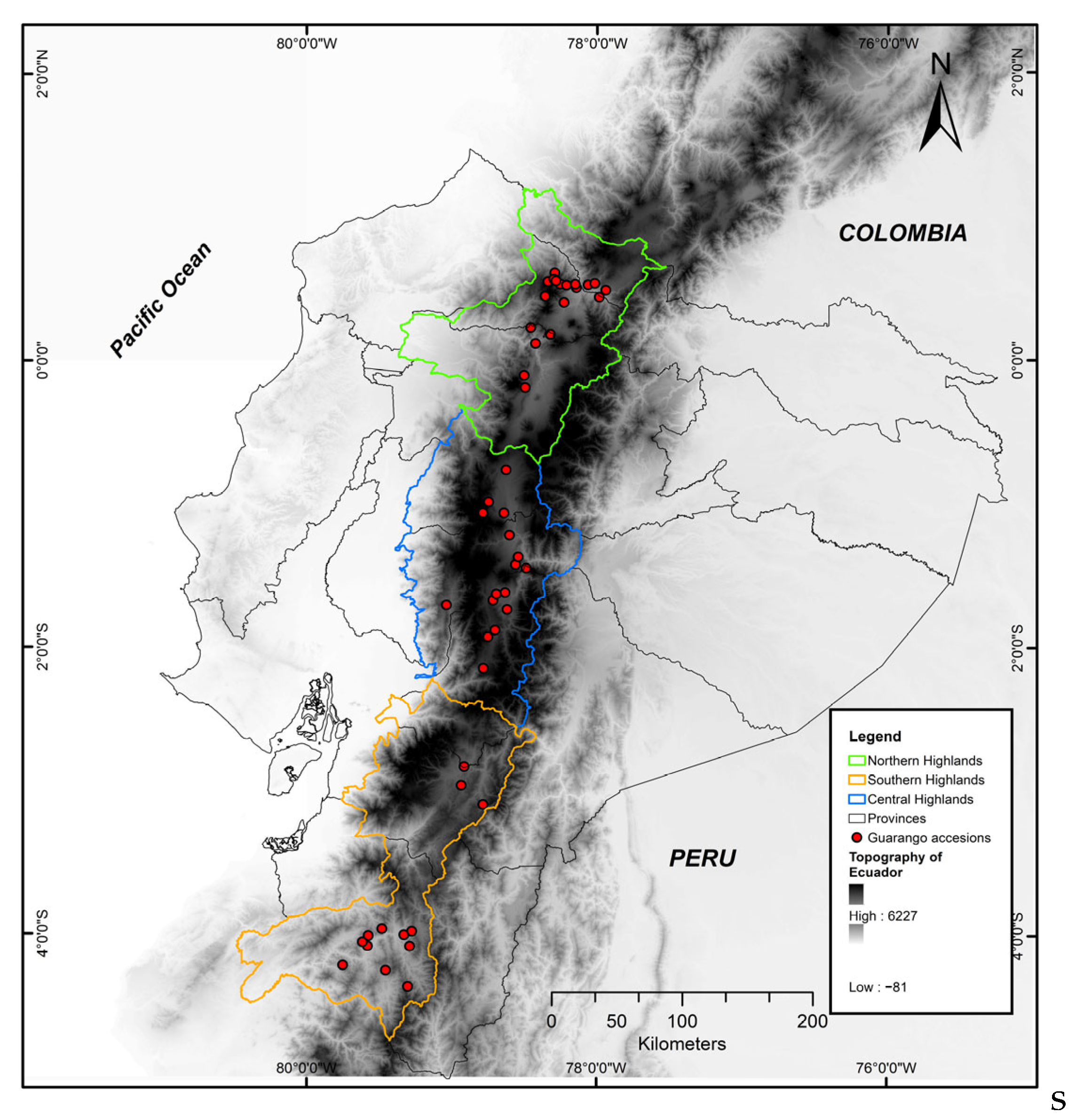

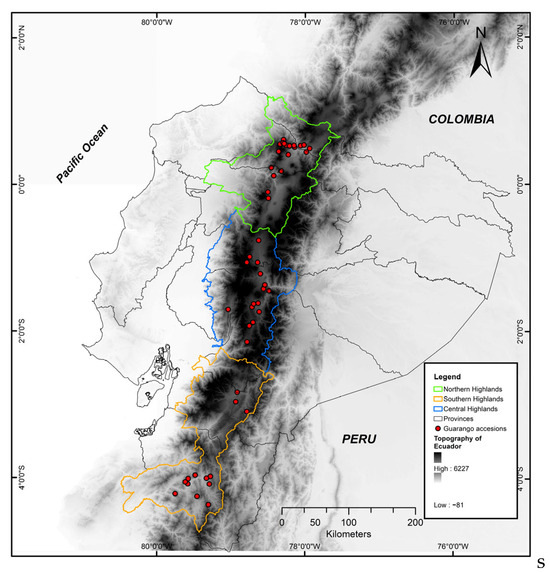

This study analyzed 39 guarango accessions originally collected in 2011 and conserved ever since at INIAP’s gene bank (base collection) under long-term storage at −15 °C with 10–12% of seeds’ moisture content [36]. Játiva [37] described the 2011 guarango’s original collection, along the Andean region of Ecuador, as a population-based strategy in which mature fruits were sampled at the micro-ecological niche level rather than from single trees, to maximize genetic representation within each site. No additional collecting missions were conducted for this study. The germplasm collection sites, corresponding to the ecoregions of the Ecuadorian Andes, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of 39 guarango accessions collected in ten provinces of the Andean region of Ecuador.

The studied germplasm corresponds to materials collected across ten provinces of the Ecuadorian highlands, at altitudes ranging from 1500 to 3000 (m.a.s.l.) (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the relative frequency of accessions within the three Andean geographical sub regions (north, central, and south), reflecting a uniform representation throughout the species’ distribution range in Ecuador.

Table 1.

Guarango accessions collected and conserved at INIAP’s Gene Bank in Ecuador.

2.2. Morphological Characterization

2.2.1. Seed Characterization

The laboratory evaluation of seeds at INIAP’s Gene Bank in Santa Catalina Experimental Station (Quito) began by retrieving the accessions from the base collection. The following seed quantitative descriptors were recorded: shape, color, length (mm), width (mm), thickness (mm), hilum position, weight of 50 seeds (g) (10–12% moisture), germination percentage, and the tetrazolium test [38] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quantitative morphological descriptors for seed, leaf, and stem used to characterize 39 guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) accessions.

For the germination tests, 20 seeds from each accession were randomly selected and divided into four replicates of five seeds. Seeds were mechanically scarified with a small cut on the lower cotyledon opposite the hilum to facilitate water absorption and then treated with a fungicide powder (Vitavax 300 WP, 125 g L−1). This pre-germination protocol was selected based on results reported by Reyes-Ramírez [39] and Guamán [16]. Seeds were placed on moistened filter paper in plastic containers and incubated in a Memmert germination chamber at 24 °C. Evaluation was performed after four days; any seed was considered germinated when the radicle—the first embryonic structure—had emerged [38,40].

For the tetrazolium viability tests, four replicates of five randomly selected seeds per accession were used. A 0.05% aqueous solution of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (C19H15N4Cl) was prepared with distilled water [38]. Seeds were treated as in the germination test, but the testa was removed. Embryos were submerged in the tetrazolium solution for 5 h at 35 °C in darkness. One cotyledon was detached to expose the inner tissues (plumule, radicle and hypocotyl) for staining evaluation [41]. Bright red or pink tissues were considered viable; white or yellow tissues dead; and, dark red tissues deteriorated, according to Fogaça et al. [42].

2.2.2. Field Characterization

For seedling production, 20 seeds per accession were subjected to the same scarification and hydration treatment used in the seed germination tests. Each seed was sown in polyethylene bags (1 kg capacity) containing a substrate composed of 60% sand and 40% topsoil and maintained in a greenhouse (25 °C average) for six months until reaching approximately 30 cm in height, at which point they were ready for field transplantation [7].

The field trial was established at Granja-INIAP-Yachay at Imbabura Province, Ecuador (00°27.76′ N, 78°09.74′ W, 1909 m.a.s.l.), characterized by a dry to semi-humid mesothermic equatorial climate. Mean annual temperatures range between 12 and 20 °C with minor seasonal variation; annual rainfall averages 500–1000 mm, with two rainy seasons (February–May and October–November) and a pronounced dry season (June–September). Soils are sandy-loam in texture, alkaline in pH, with 12–25% slopes, low organic matter, low cation exchange capacity and high base saturation [43].

Field morphological characterization included the 17 quantitative and 7 qualitative descriptors (Table 2 and Table 3); the descriptors followed the scales proposed by Villena et al. and Bonilla et al. [2,44], adapted from Monge-Solis et al., Doster et al., and Bianciotto et al. [45,46,47]. Variables were measured one year after planting in the field. Seed, stem, and leaflet colors were determined by using the RHS Color Chart [48]. The qualitative descriptors for seed, leaf and stem are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Qualitative morphological descriptors used to characterize 39 guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) accessions.

Field evaluation began when the trees were one year old after transplanting. The assessment focused on two plant organs of leaves and stem, as follows:

Tree traits: Total height (cm), collar diameter (mm, measured 10 cm above soil), diameter at breast height (DBH, cm, at 130 cm above ground for trees >150 cm tall), number of prickles per dm, and bark color [49].

Leaf traits: Leaflet length (mm), rachis length (mm), number of leaflets per leaf, number of subleaflets per leaflet, subleaflet length and width (mm), adaxial and abaxial subleaflet color, and presence/absence of spines [50].

2.3. Experimental Design

The 39 accessions were arranged in a Randomized Complete Block Design with three replications, each consisting of two trees per accession.

2.4. Silvicultural Management

Land preparation involved one-disc harrow pass and planting spacing was 5 × 5 m; guarango accessions were planted in October 2023. Mechanical weed control was performed every 60 days after planting and irrigation was applied every 15 days as needed to ensure establishment. Thirty days after transplanting, a chemical control treatment was applied against Hoplopactus cf. segnipes, which caused severe defoliation (30% of trees). The following insecticides were applied: Engeo® (lambda-cyhalothrin, 106 g L−1, and thiamethoxam, 141 g L−1) at a rate of 0.1 L ha−1; and Cyperpac® (cypermethrin, 200 g L−1) at a rate of 0.3 L ha−1. A second application was performed seven days after the initial treatment.

2.5. Ecogeographical Characterization

Ecogeographical characterization was performed using passport data from collection sites stored in the GRIN-Global database of the INIAP’s Gene Bank. Data were processed with five tools from CAPFITOGEN 3 software [27]: Testable v.3, GEOQUAL v.3, Selecvar v.3, ECOGEO, v.3 and Divmaps v.3. The resulting maps were further processed using ArcGIS® 10.8 [51], for interpretation.

The CAPFITOGEN 3 [27] software was used to select ecogeographical variables relevant to the formation of adaptation groups in guarango from 80 biophysical and 31 geophysical variables (available at WorldClim v2.1), as well as 66 edaphic variables obtained from the HWSD and SoilGrids databases. The variable selection was based on two complementary criteria: (i) expert consultation with researchers experienced in the species and (ii) the application of the SelecVar module, which integrates three statistical approaches—Random Forest, bivariate correlation, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)—to identify the most informative and non-redundant variables [52].

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.6.1. Morphological Characterization

Morphological data from both seed and field characterizations were analyzed using InfoStat Professional v.2020 [52] and R statistical software v.4.3.2 [53]. The dataset included both qualitative and quantitative variables, with mean and modal values computed from six experimental units (six trees) per accession.

Qualitative descriptors were analyzed using frequency distributions, while quantitative traits were summarized using mean, coefficient of variation (CV), and minimum and maximum values. A principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on quantitative variables. Qualitative variables were converted into binary form (0/1) for color and presence/absence descriptors (seed color, leaflet adaxial/abaxial color, and stem color).

The cluster analysis was conducted using both qualitative and quantitative variables. Hierarchical clustering employed Ward’s minimum variance method [54] and Gower’s similarity coefficient [55] Variables contributing most to group formation were determined using ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD test [56].

2.6.2. Ecogeographical Characterization

The ecogeographical data were analyzed with software packages Infostat v.2020 (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina) [52], and R software v.4.3.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) [53]. The database included 21 quantitative variables averaged across 39 collection sites.

The cluster analysis used Ward’s method and Euclidean distance. Variables contributing most to group differentiation were identified via ANOVA and Fisher’s LSD test [56]. In addition, cophenetic correlation coefficients and bootstrap support values (minimum 1000 resamples) were computed in R to assess clustering robustness. All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed using the following R packages: pvclust v.2.2-0 [57], cluster v.2.1.6 [58], tidyverse v.2.0.0 [59], factoextra v.1.0.7 [60], and caret v.6.0-94 [61].

The Mantel test [62] was applied to assess correlation between morphological and ecogeographical distance matrices, using 999 random permutations. Analyses were performed in R [53].

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Characterization of the Ecuadorian Collection of Guarango

3.1.1. Quantitative Variables

From 17 quantitative variables (seed and field characterizations), four showed the most significant variation. In descending order, the variables that stood out were as follows: germination percentage (CV = 50.95%) ranging from 6.67 to 73.33%; tetrazolium staining test (CV = 34.39%) ranging from 20 to 100%; total height (CV = 28.30%) ranging from 60.17 to 208.67 cm; and DBH (diameter at breast height) (CV = 24.29%), ranging from 4.51 to 15.33 mm.

Variables with a CV < 10% exhibited the least variability, mainly related to leaf and seed traits as follow: number of leaflets (CV = 9.68%), weight of 50 seeds (CV = 9.63%), followed by thickness, length/width ratio, seed length, and seed width (CV = 4.84, CV = 4.41, CV = 4.11, and CV = 3.76, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean, standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), and minimum and maximum of 17 quantitative morphological descriptors evaluated in the Ecuadorian collection of guarango.

The variable with the highest standard deviation (28.30) and CV was total height, expressed in centimeters (measured at 12 months of growth after transplanting), revealing accessions with heights ranging from 60.17 to 208.67 cm, with an average of 116.42 cm. Notably, four accessions exceeded 150 cm in height (ECU-17733, ECU-17735, ECU-17741, and ECU-17750).

3.1.2. Qualitative Variables

In the case of seeds, 100% of the accessions presented an obovate-globose shape, a centrally located basal hilum and a dark brown color (distributed in four shades: 200A—18%, 200B—56%, 200C—23%, and 200D—3%). Regarding the leaves, 100% of the accessions exhibited spines and the adaxial (upper) surface of the subleaflet showed a dark brownish-green color. On the other hand, for the abaxial (lower) surface of the subleaflet, 20.51% of the accessions displayed a dark brownish-green color, while 79.49% presented an intermediate brownish-green color. Finally, regarding bark color, 53.85% of the accessions showed a dark brown color and 46.15% showed an intermediate brown color (Table 5).

Table 5.

The frequency analysis of qualitative descriptors of seeds, leaves, and stem of the guarango collection.

3.1.3. Multivariate Analysis

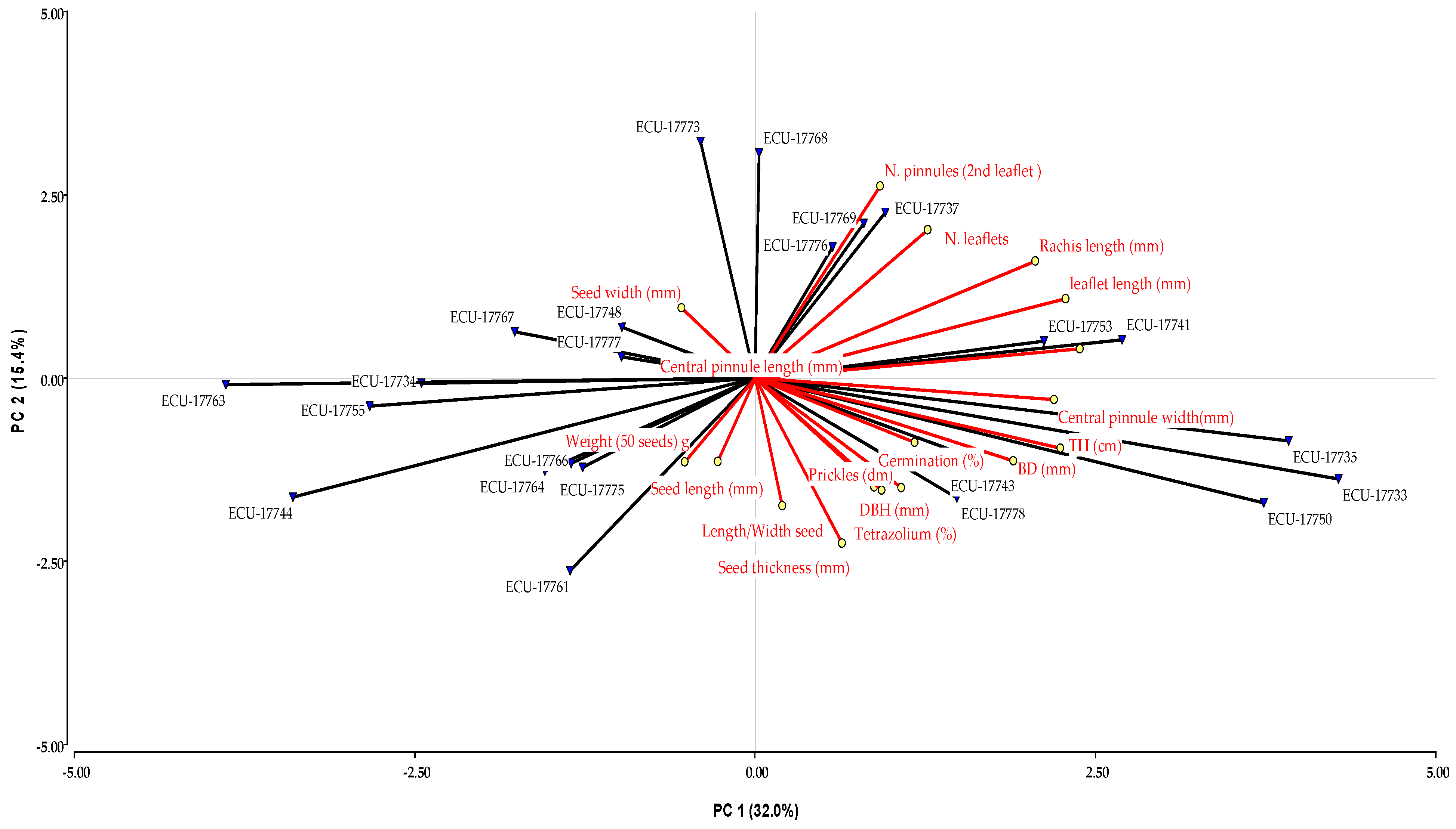

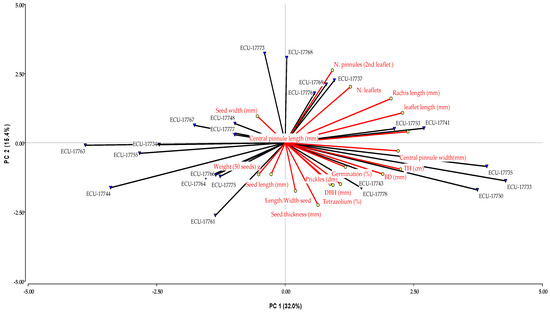

Principal Component Analysis

In the PCA, five principal components with eigenvalues greater than one were selected, accounting for a cumulative variability of 81%. Figure 2 shows the first two components, which explained 32.0% and 15.4% of the total variance, respectively.

Figure 2.

PCA on the guarango collection, based on quantitative data. The first two axes represent 47% of the total variance.

The first component, which explains 32% of the variance, is associated with the length and width of the central subleaflet, leaflet length, rachis length, total tree height, and collar diameter. The second component, accounting for 15% of the variance, is related to the number of leaflets and subleaflet per leaf, seed thickness, and the number of prickles per dm. The third component explains 14% of the variance and is associated with the weight of 50 seeds, as well as seed length and width. The fourth component explains 12% of the variance and is mainly related to seed width and the seed length-to-width ratio. Finally, the fifth component, explaining 7% of the variance, Is associated with seed germination percentage and tetrazolium viability test results.

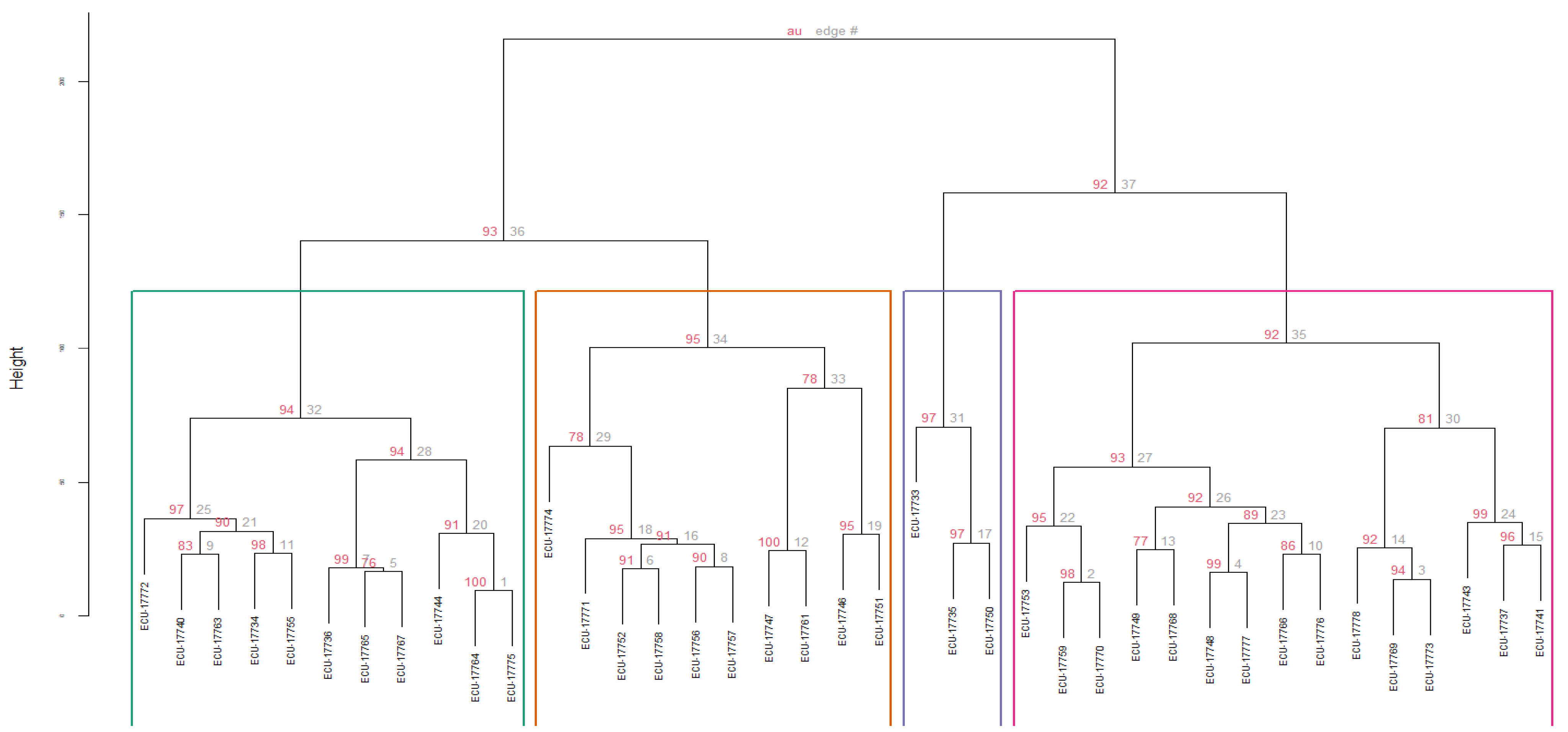

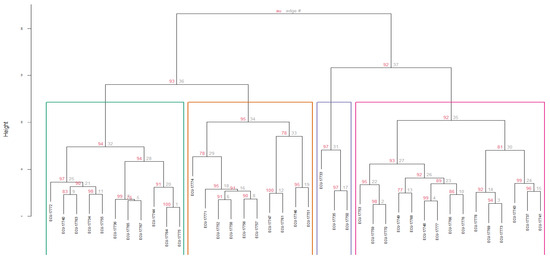

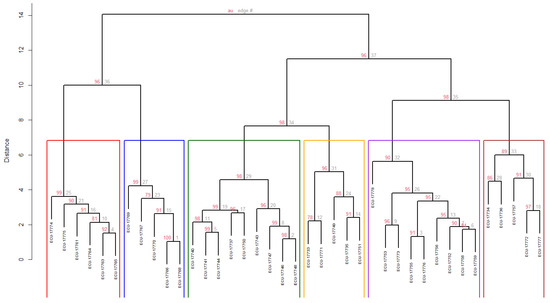

Cluster Analysis

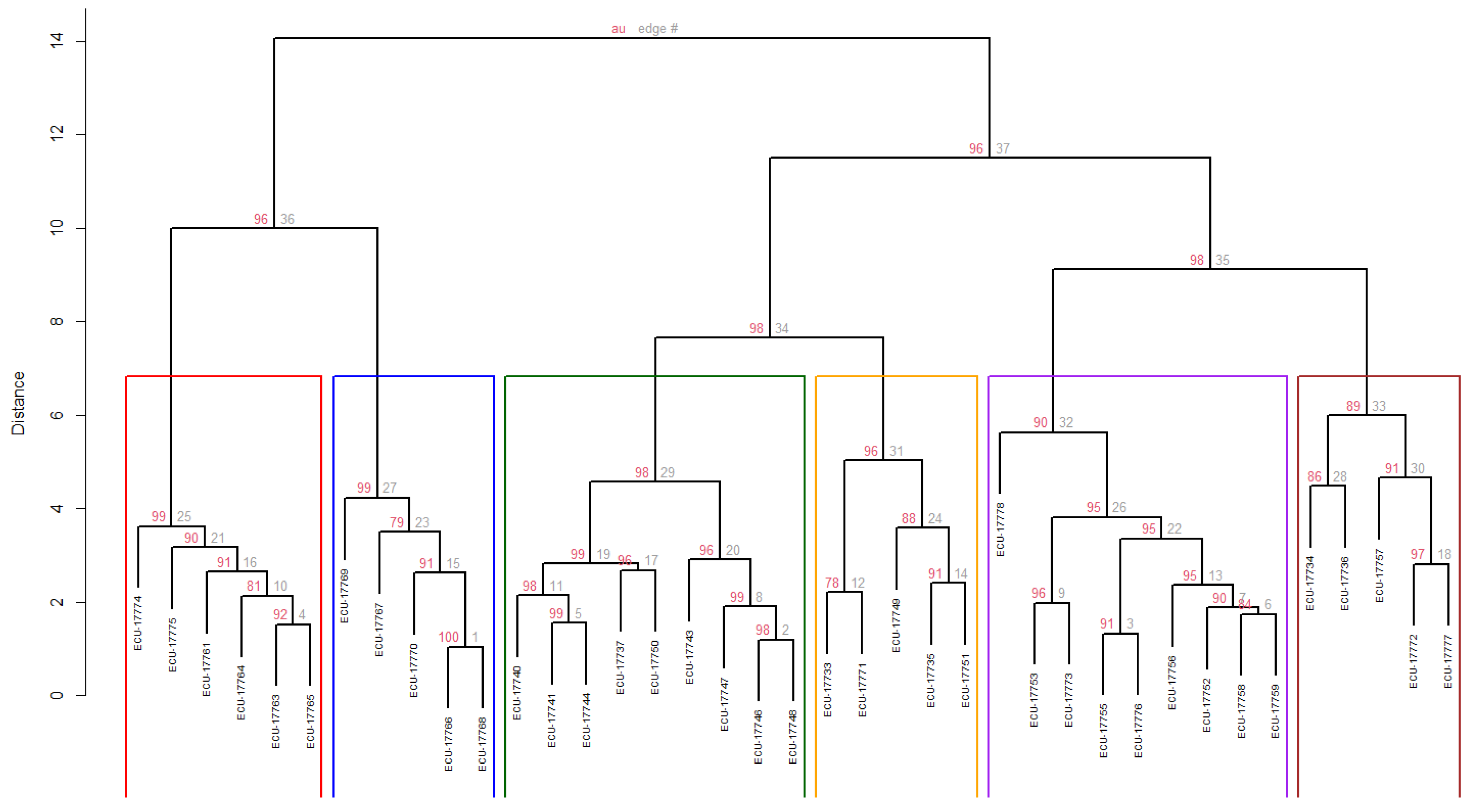

For the cluster analysis, a total of 16 quantitative descriptors (those with the highest discriminatory power based on the PCA) and four qualitative descriptors (those showing significant differences among accessions) were used. Four groups were identified, defined by a cophenetic coefficient (CCC) of 0.7135. No accession exhibited a phenotypic distance equal to zero, indicating the absence of duplicates within the collection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dendrogram obtained through hierarchical cluster analysis (Ward’s method) using Gower’s similarity distance for qualitative and quantitative variables in 39 accessions of guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa). Bootstrap of 1000 permutations.

3.1.4. Morphological Variability of Quantitative Variables

Regarding the group structure, Cluster 1 (C1) comprised eleven accessions (28%), which is represented in green in the Figure 3, grouped with an Approximately Unbiased bootstrap probability (AU) of 95%. This group was characterized by the lowest germination rates (%G = 22.42%) and viability with the tetrazolium test (TST = 47.27%). This group ranked second last in average tree height (TH at 107.90 cm, root collar diameter (CD) at 15.40 mm, subleaflet width (CSL_W) at 8.79 mm, subleaflet length (CSL_L) at 18.98 mm, length of the leaflet (L_L) at 86.88 mm, rachis length (R_L) at 80.17 mm, number of subleaflets (N_SL) at 12.94, and number of leaflet (N_L) at 8. For the seeds (W_S50), they weighed 14.03 g per 50 seeds, with a thickness (S_T) of 4.88 mm, a width (SW) of 7.91 mm, and a length (S_L) of 9.98 mm.

Cluster 2 (C2), consisting of ten accessions (26%), presented an AU of 95%, which is represented in orange in the Figure 3. This group exhibited the highest value among all groups for %G (56.67%) and the second highest for TS_T (68%). Conversely, this group ranked last in TH at 94.04 cm, CD at 13.78 mm, CSL_W at 8.63 mm, CSL_L at 17.85 mm, L_L at 81.12 mm, R_L at 73.00 mm, N_SL at 12.83, and N_L at 7.42. Regarding W_S50, it was 13.85 g per 50 seeds, S_T was 4.96 mm, SW was 7.71 mm, and S_L was 9.93 mm.

Cluster 3 (C3) included three accessions (8%) and was grouped with an AU of 97%, which is represented in blue in the Figure 3. This group displayed the second-highest value among all groups for %G (55.56%) and the highest for TS_T (86.67%). This group achieved the highest values for TH (182.11 cm), CD (25.00 mm), CSL_W (11.33 mm), CSL_L (25.00 mm), L\_L (113.22 mm), and R_L (107.72 mm. On the other hand, the group ranked second in N_SL (13.89) and N_L (8.67). Related to the seeds, this cluster presents W_S50 of13.17 g per 50 seeds, S_T 5.05 mm, SW 7.60 mm, and S_L 9.79 mm.

Cluster 4 (C4) comprised fifteen accessions (38%) with an AU of 94%, which is represented in pink in the Figure 3. This group presented the highest values for N_SL (14.09) and N_L (8.78), and the second last value among all groups for %G (42.67%) and TS_T (49.33%). This group achieved the second-highest values for TH (124.45 cm), CD (15.52 mm), CSL_W (9.81 mm), CSL_L (22.12 mm), L_L (104.08 mm), and R_L (104.48 mm). Related to seeds, the W_S50 was 14.01 g per 50 seeds, S_T 4.90 mm, SW 7.95 mm, and S_L 9.91 mm. Table 6 presents the mean values of quantitative traits across the four clusters established from the guarango accessions.

Table 6.

Mean values of quantitative traits among the four groups identified in guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) accessions.

In the analysis of variance, ten variables (CSL_W, T_H, DC, %G, CSL_L, L_L, R_L, N_SL, N_L, TS_T)- exhibited significant differences (p < 0.05) for group differentiation. For the meaning of the variables see Table 2.

Based on the CV, %G was the variable with the highest dispersion (CV = 40.90%) and TS_T (CV = 27.69%). Variables with dispersions between 10 and 20% included TH (CV = 15.04%), CD (CV = 12.06%), and R_L (CV = 10.81%).

In comparison, the variables N_L (CV = 7.04%) and N_SL (CV = 5.24%) were the most homogeneous. Nonetheless, they were found to be significant (p = 0.001) for group differentiation (Table 6).

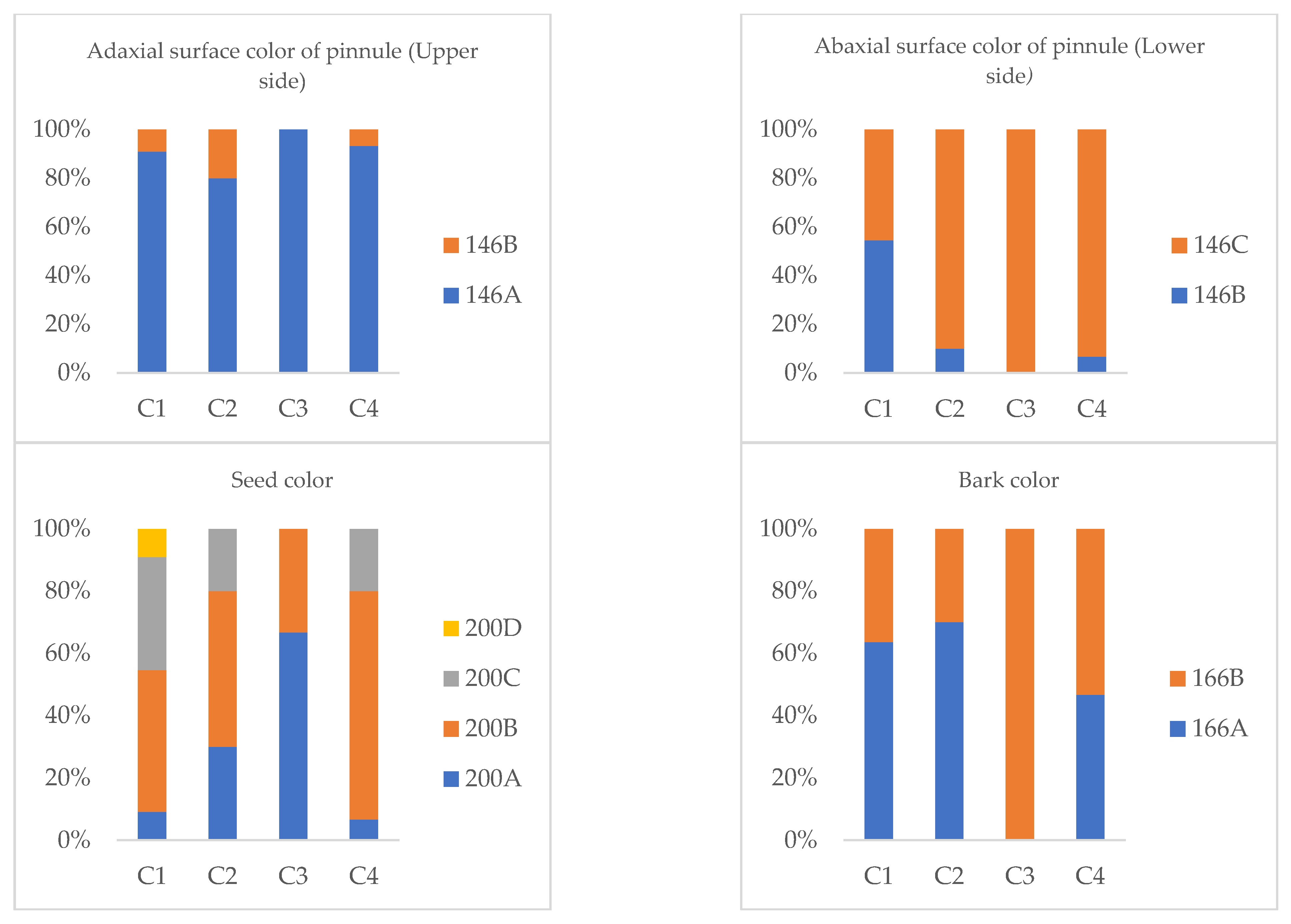

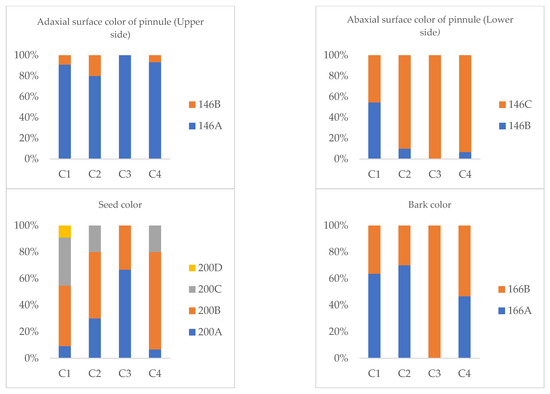

3.1.5. Morphological Variability of Qualitative Variables

The observed morphological variability revealed that all accessions within the groups exhibited a brownish-green color on the upper surface of the leaflets. C3 presented a single shade (146A), while C1, C2, and C4 presented a combination of shades of 146A and 146B, the latter being present in 10–20% of the samples. A similar pattern was observed for the color of the lower surface of the leaflets, where all groups were brownish green; C3 presented a single shade (146C), while C1, C2, and C4 presented a combination of shades 146B and 146C.

For seed color, the following differences were identified: C1 presented dark brown seeds in three shades (200A = 9%, 200B = 46%, 200C = 36%) and medium brown seeds (200D = 9%). C2 presented dark brown seeds in three shades (200A = 30%, 200B = 50%, and 200C = 40%). Similarly, C3 presented three shades of dark brown (200A = 7%, 200B = 73%, 200C = 20%). Finally, C4 showed dark brown seeds in two shades (200A = 67% and 200B = 33%).

Regarding the color of the bark, all accessions showed a medium brown coloration, with different shades: C1 (166A = 64%, 166B = 36%), C2 (166A = 70%, 166B = 30%), C3 (166B = 100%), and C4 (166A = 47%, 166B = 53%).

Figure 4 describes the frequency distribution of color categories for the adaxial and abaxial subleaflet surfaces, seeds, and bark among guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) accessions.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution of color categories for the adaxial and abaxial leaflet surfaces, seeds, and bark of guarango accessions.

3.2. Ecogeographical Characterization of the Ecuadorian Collection of Guarango

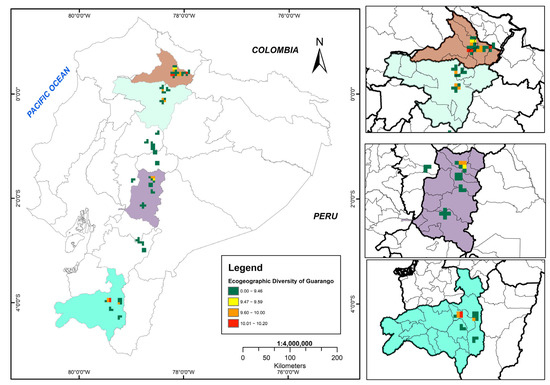

Cluster Analysis

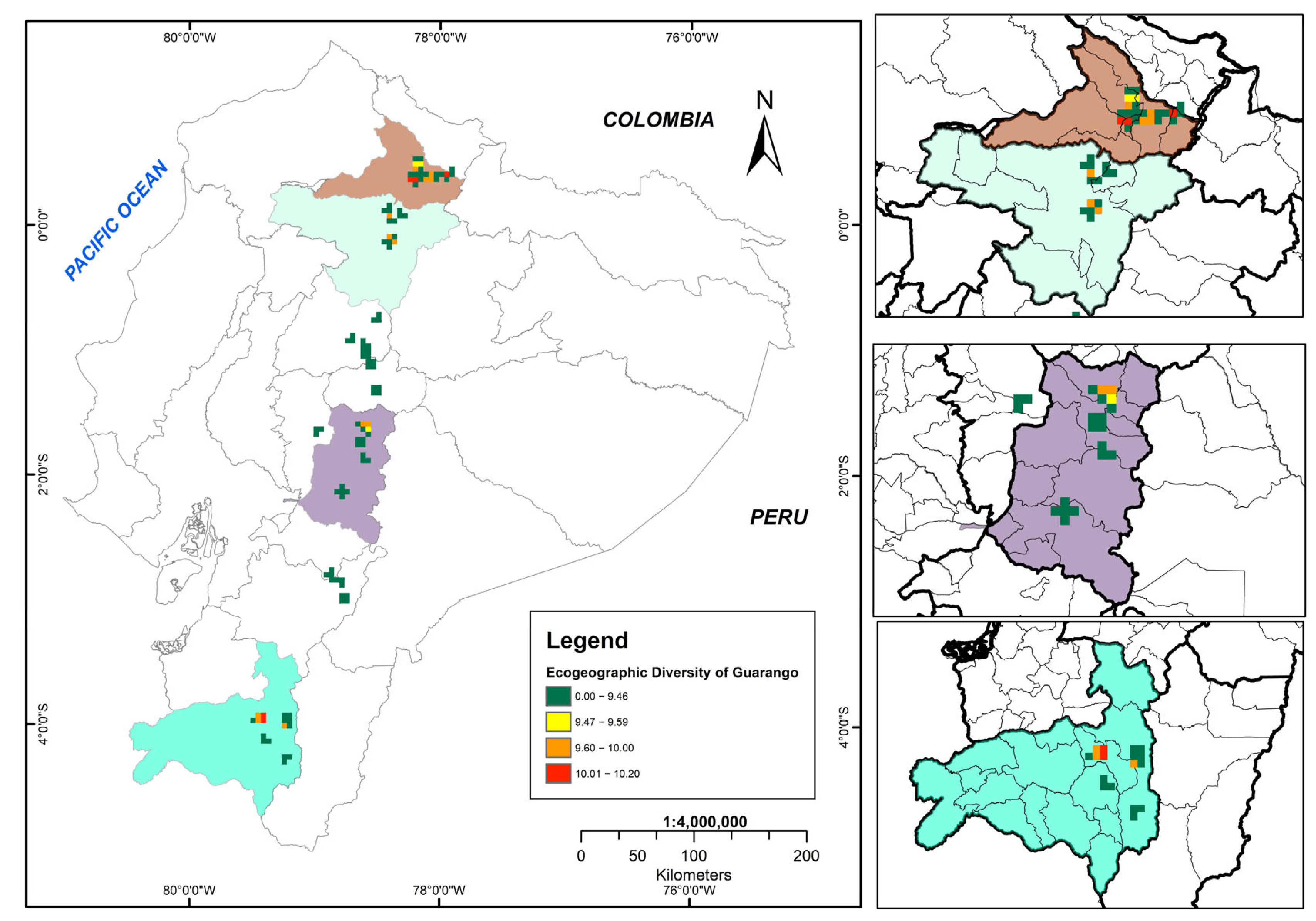

For the cluster analysis, 21 quantitative ecogeographical descriptors were used (Table 7), identifying six groups defined by a CCC of 0.7349. No accession exhibited a distance equal to zero, indicating that no duplicates were identified within the collection (Figure 5).

Table 7.

Mean values of 21 quantitative ecogeographical variables—bioclimatic (10), edaphic (8), and geophysical (3)—for the six groups of guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) accessions, including statistical results from Fisher’s test.

Figure 5.

Dendrogram of the guarango collection showing six clusters of accessions based on quantitative ecogeographical data, using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance. Bootstrap of 1000 permutations.

Regarding group structure, Cluster 1 (C1) consisted of six accessions (15%) grouped at an Approximately Unbiased bootstrap probability (AU) of 86%, which is represented in red in the Figure 5. The accessions in this group are mainly distributed in the southern highlands (subregion south), particularly in the provinces of Azuay and Loja, with one accession from Tungurahua (central subregion). This cluster was characterized by the lowest solar radiation (13,858.22 kJ m−2), the smallest mean diurnal temperature range (10.62 °C), the greatest precipitation during the driest month (50.67 mm) and one of the highest annual precipitation values (933.17 mm).

Cluster 2 (C2) included five accessions (13%) grouped at an AU of 99%, which is represented in blue in the Figure 5. This group is located exclusively in the province of Loja (south subregion) and is characterized by the lowest elevation (1911 m.a.s.l.), the lowest precipitation during the driest month (13.40 mm), the lowest soil water availability across the three soil horizons (h1 = 14.57%, h2 = 11.19%, h3 = 9.30%), the lowest cation exchange capacity (18.39 cmol kg−1), the lowest silt content (26.53%) and the lowest soil pH (5.82). Conversely, it presented the highest values for maximum temperature of the warmest month (25.40 °C), minimum temperature of the coldest month (12 °C), mean annual temperature (18.48 °C), mean temperatures of the wettest, warmest, and coldest quarters (18.36, 18.76, and 18.12 °C, respectively), and annual precipitation (962 mm).

Cluster 3 (C3) comprised nine accessions (23%) clustered at an AU of 98%, which is represented in darkgreen in the Figure 5. The accessions in this group are exclusively from the province of Imbabura (north subregion) and are characterized by the lowest wind speed (7.44 km h−1), the highest soil cation exchange capacity (30.73 cmol kg−1), the highest silt content (34.06%) and the lowest sand content (40.24%).

Cluster 4 (C4) comprised five accessions (13%) grouped at an AU of 96%, which is represented in orange in the Figure 5. This group is geographically located in the northern highlands (north subregion), specifically in the provinces of Pichincha and Carchi. It exhibited the highest values among all groups for solar radiation (15,655.85 kJ m−2), mean diurnal temperature range (13.22 °C), annual temperature range (15.24 °C), sand content (47.80%) and soil pH (6.77).

Cluster 5 (C5) included nine accessions (23%) clustered at AU of 90%, which is represented in purple in the Figure 5. Geographically, these are in the central highlands (central subregion), within the provinces of Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, and Cañar. This group is characterized by the highest mean elevation (2645 m.a.s.l.), the lowest annual precipitation (624 mm), one of the lowest sand contents (41%), and the second-highest soil pH (6.53).

Finally, Cluster 6 (C6) comprised five accessions (13%) grouped at an AU of 89%, which is represented in brown in the Figure 5. These accessions originate from the provinces of Pichincha, Cotopaxi, Chimborazo, and Bolivar (central subregion). This group exhibited the highest wind speed (11.09 km h−1), the greatest soil water availability across the three soil horizons (h1 = 17.84%, h2 = 14.09%, h3 = 11.76%), the lowest mean annual temperature (10.90 °C), the narrowest annual temperature range (12.44 °C) and the lowest mean temperatures for the wettest, warmest, and coldest quarters (11.06, 11.14 and 10.38 °C, respectively).

All variables showed significant differences (p < 0.05) for cluster differentiation. According to the mean coefficient of variation (CV), the precipitation of the driest month (CV = 34.01%) was the most dispersed variable. Variables with intermediate dispersion (CV between 10 and 20%) included the cation exchange capacity (CV = 19.26%), annual precipitation (CV = 16.88%), minimum temperature of the coldest month (CV = 12.90%) and clay content (CV = 12.57%).

In contrast, variables such as silt content (CV = 5.00%), pH (CV = 3.82%) and annual solar radiation (CV = 3.63%) exhibited the lowest coefficients of variation, therefore the most homogeneous, although statistically significant (p = 0.001) for group differentiation (Table 7).

3.3. Ecogeographic Diversity Map of Guarango

The bioclimatic, geophysical, and edaphic variability of the study area is represented by variables such as precipitation, temperature, altitude, soil texture and pH, which reflect the geographic adaptation range of guarango in Ecuador. Figure 6 illustrates the ecogeographic diversity map, where red areas indicate the highest diversity and green areas indicate lower diversity.

Figure 6.

Ecogeographic diversity map of the Ecuadorian collection of guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa).

Six cantons exhibited very high ecogeographic diversity (10.01–10.20), distributed across two provinces: Imbabura (north subregion) and Loja (south subregion). The maximum diversity value (10.20) was recorded in Imbabura province, particularly in the cantons of Cotacachi, Antonio Ante, Ibarra, Urcuquí and Pimampiro. In Loja Province, high diversity was concentrated in the central zone of Catamayo canton.

The medium ecogeographic diversity category (9.60–10.00) encompassed six cantons across four highland provinces: Imbabura, Pichincha (north subregion) and Chimborazo and Loja (south subregion).

Areas with low ecogeographic diversity (9.47–9.59) were in four cantons of two provinces (Imbabura and Chimborazo), whereas very low diversity (0.00–9.46) occurred throughout the ten provinces of the Andean region.

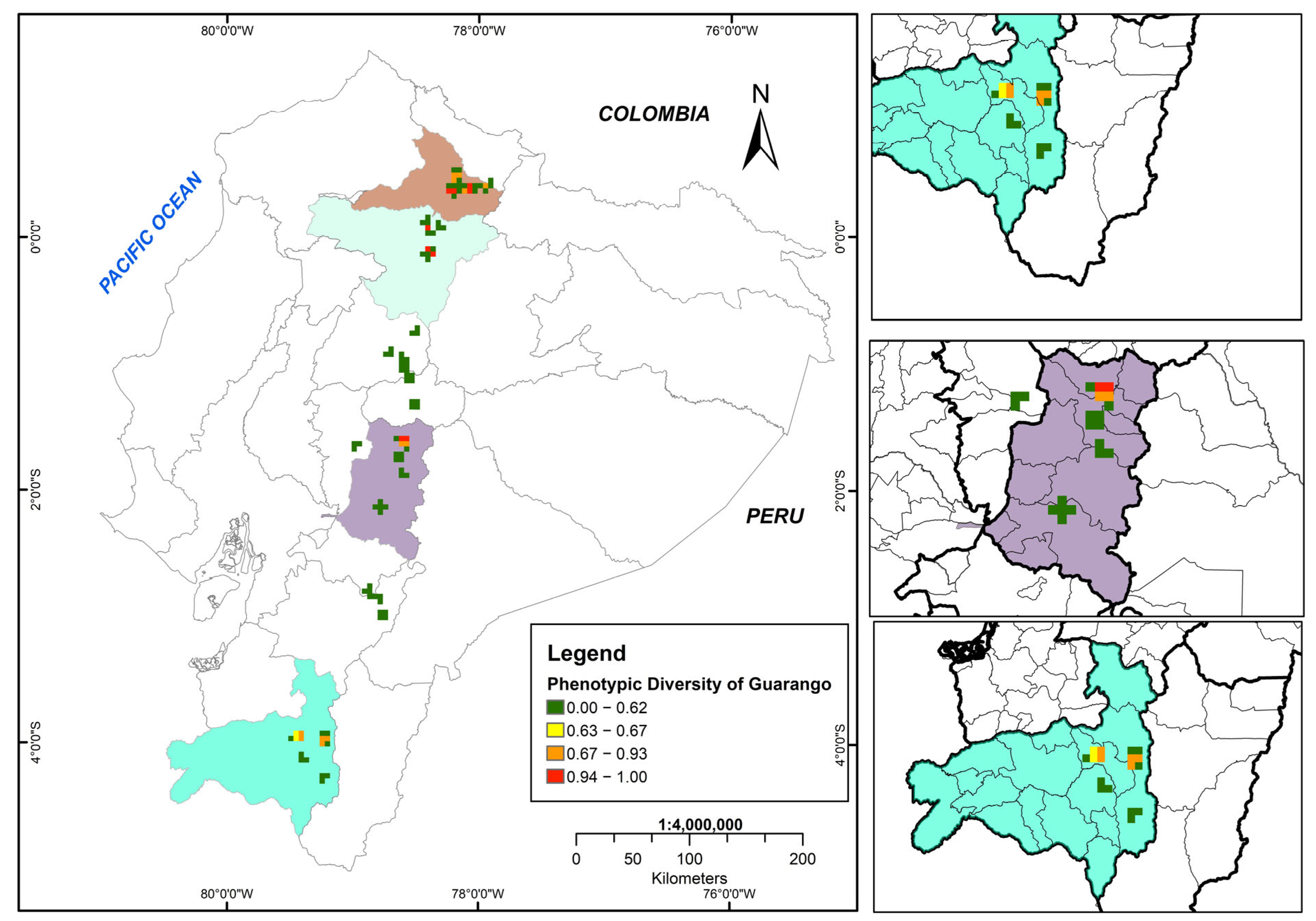

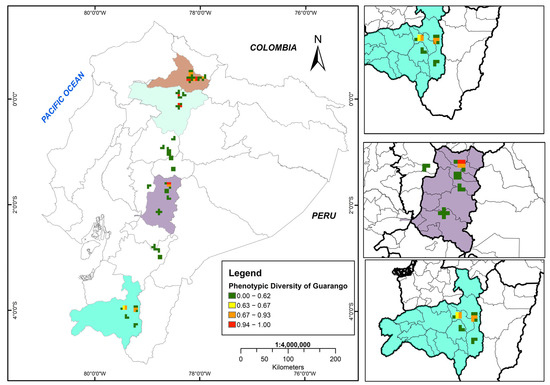

3.4. Morphological Diversity Map of Guarango

In Ecuador’s inter-Andean region, six cantons across three provinces exhibited high phenotypic diversity in guarango (0.94–1.00), corresponding to Imbabura (Cotacachi, Urcuquí, Antonio Ante and Ibarra), Pichincha (Quito)–north subregion, and Chimborazo (Guano)–central subregion.

Moderate morphological diversity (0.67–0.93) was recorded in seven cantons from three provinces: north subregion of Imbabura (Urcuquí, Ibarra and Pimampiro), central subregion of Chimborazo (Guano and Riobamba), and south subregion of Loja (Loja and Catamayo). The Catamayo Canton in Loja Province presented low morphological distances (0.63–0.66).

Finally, along the inter-Andean corridor, zones of very low morphological diversity (0.00–0.62) were identified. These results reveal a clear spatial gradient in the distribution of morphological variation throughout the study area (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The morphological diversity map of the Ecuadorian guarango collection (Caesalpinia spinosa), where green tones represent low diversity (0.00), and red tones indicate high diversity (1.00).

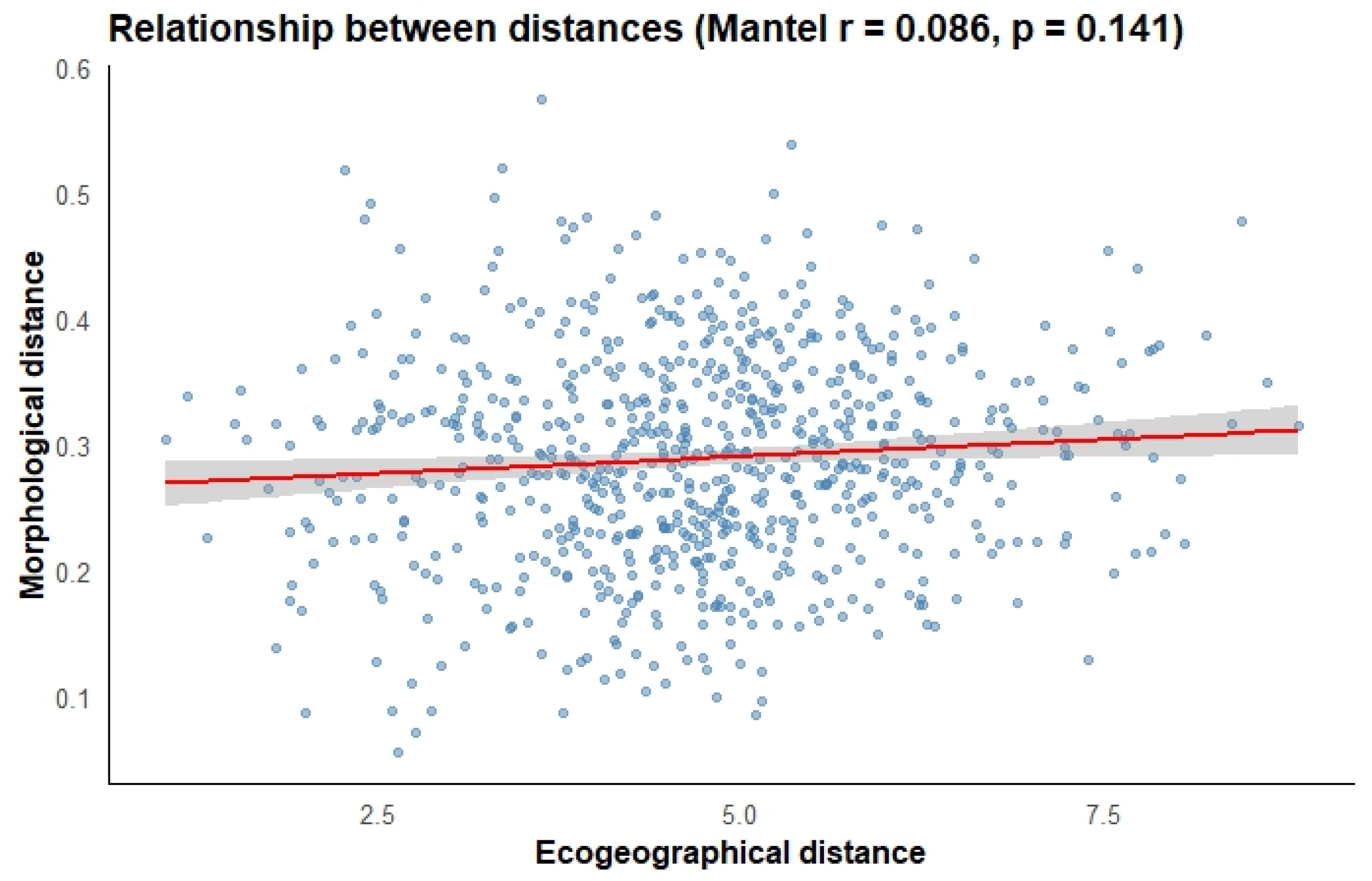

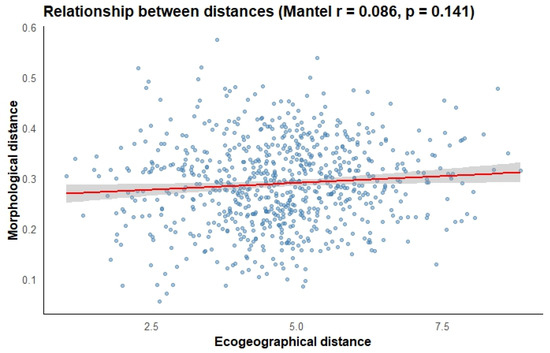

3.5. Correlation Between Morphological and Ecogeographic Data

The correlation analysis between the morphological distance matrix and the ecogeographic distance matrix of guarango revealed no significant correlation (p = 0.141) and a low correlation coefficient (r = 0.086) (Figure 8). Nevertheless, the combined results of the morphological and ecogeographic characterizations indicate that certain guarango accessions possess distinct morphological traits and adaptation to specific agroecological conditions.

Figure 8.

Relationship between morphological and ecogeographic distance matrices.

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Characterization

Substantial variability was observed in the tree height descriptor within the guarango collection. The uniformity of the agronomic management applied across the Imbabura trial suggests that this pronounced phenotypic variation reflects intrinsic genotypic differences in response to the environment, a valuable trait for selection [63]. This height range variability during the first year (94 to 182 cm), represents values notably higher to previous reports showing slow juvenile growth, with annual increments typically between 5 and 15 cm [46,64]. Probably the favorable site conditions at Imbabura—particularly soil moisture, soil fertility, and temperature regime—significantly enhanced the growth and physiological performance of guarango [32,65]. Additionally, this superior early growth may be due to the different seed vigor of the seed-lots [66]. These combined factors could explain why some accessions reached height values approaching those reported for two-year-old commercial plantations in Peru under intensive management [13]. On the other hand, Narváez et al. [14] observed that specific phenotypic variability in natural C. spinosa populations was directly attributed to genotype-by-environment interaction (GxE); if this is the case, there is a necessity to evaluate our genotypes across multiple environments and with the use of any molecular analysis.

For leaf descriptors, significant differences were found in the number of leaflets (three to four pairs) or subleaflets per leaf (13–14), consistent with the five morphotypes proposed for tara varieties along an altitudinal gradient in Ayacucho, Peru [25]. Subleaflet size ranged between 1.4 and 4.5 cm in length and 1 and 2.5 cm in width, in agreement with Doster et al. [46].

Morphological characterization also allowed the identification of materials with desirable traits such as plant vigor, growth habit and seed dimensions-features relevant for breeding programs [67]. The principal component analysis showed that most components were associated with seed traits, which are key determinants for the genetic breeding of guarango. In Peru, Bonilla et al. [44], Florián [68], and Villena et al. [69] reported a total variance of 91.3%, 79.05%, and 73%, respectively, all based on seed and pod descriptors. The results of the present study are consistent with these findings, although here trunk, seed and leaf descriptors were included, while pod traits were excluded due to the young age of the trees.

The cluster analysis showed that all guarango groups exhibited the same seed shape (globose-abovate), hilum position (basal-central) and seed color (brown, 200A–D). By contrast, Villena et al. [69] reported three seed shapes (globose-abovate, flattened-abovate, and rhomboid), two hilum positions (basal-central and basal-lateral) and two seed colors (brown, 200A–D, and grayish brown, 199A), suggesting lower variability in the Ecuadorian collection compared to Peru.

Regarding seed dimensions, no differences were detected among clusters, the results for seed length, according to the classification proposed by Villena [2], correspond to a single morphotype (Blanca). In contrast, the values for seed width, thickness, and weight in this study exceeded those reported for the six morphotypes described by that author. Compared with the findings of Portal [25], the seed length observed here matches the Roja Ayacuchana variety, the seed width falls within the range of three varieties (Almidón Gigante, Roja Ayacuchana, and Verde Esmeralda) and the seed thickness corresponds to four varieties (Morocho, Almidón Gigante, Roja Ayacuchana, and Verde Esmeralda). The seed weight values recorded in this study were higher than those reported in previous studies conducted in Peru [44,70]. Regarding the length-to-width ratio, although statistically significant differences were found among groups, all values fell within the intermediate ratio category (≥1 ≤1.5), similar to five of the seven groups identified in Villena et al. [69] for Peru.

Germination rates among groups ranged from 22 to 56%, values comparable to the maximum germination percentages of 44.75% (mature and scarified seeds) reported by Mancheno-Cárdenas et al. [71]; 48.5% by using sulfuric acid scarification in Plaza et al. [72]; and 24–62% hydrated and scarified seeds in Guerrero Sosa et al. [38]. These results confirm that guarango seed germination depends on seed maturity, scarification type and temperature, but additional germination studies are needed. The tetrazolium viability test revealed variability ranging from 47 to 87%, lower than the 73.45% and 87% reported by Mancheno-Cárdenas et al. [71] and Guerrero Sosa et al. [38] these differences may be attributed to the physiological maturity of seeds and seasonal variation in the environmental conditions during collection, rather than to genetic factors [71,73]. These findings reinforce the notion of low natural regeneration rates [65]; which stresses the importance of conducting additional research such as better understanding of guarango’s phenology (fruiting period, duration of seed maturity) or morpho-anatomical seed evaluation, etc. which will contribute to the propagation and conservation of this species [74]. These factors could be especially important once currently in situ seed collection requires significant time, cost, and effort [75,76,77].

Although productivity as a desirable trait could not be evaluated in this study because the guarango trees, at the time of this publication, did not reached their productive phase. However, the observed phenotypic variability highlights the importance of continuing the morphological characterization of the Ecuadorian collection.

4.2. Ecogeographic Characterization

According to the ecogeographic characterization results, the clusters showed a latitudinal arrangement across northern, central and southern zones of Ecuador’s Andean region. Five clusters occupied altitudinal ranges between 1900 and 2385 m.a.s.l., whereas Cluster 2 average altitude is 2645 m.a.s.l., similar to the altitudinal range of the Almidón Gigante ecotype from Peru [25].

Regarding the Biophysical variables, Annual solar radiation ranged from 13,000 to 16,000 kJ·m−2, lower than the 61,174 kJ·m−2 reported in studies of morphological variation and climatic influence on fruit and seed morphology in Peru [22]. The wind speed across clusters ranged from 7.8 to 11.09 km·h−1, classified as a light breeze on the Beaufort scale [78]. Wind can affect height–diameter growth relationships due to tension on outer trunk and branch fibers, although morphological responses vary intra- and interspecifically, even among species of the same genus, despite eco-physiological and morphological similarities [22,79]. The mean annual temperature ranged from 10 to 19 °C, consistent with the 4.3–25 °C range reported by Villena et al. [22] the 15.92–18.68 °C reported by Hidalgo [29] and the 15–25 °C range described by Gómez [33]. Annual precipitation ranged from 623 to 962 mm, which aligns with the distribution reported by Hidalgo [29] in southern Ecuador (Loja Province) and with the findings of Villena [22,80].

Regarding the edaphic variables e.g., soil texture, the groups were primarily classified as loam and clay loam [81], consistent with two of the four texture classes (loam, clay loam, clay, and sandy clay loam) reported by Hidalgo [29] for guarango distribution models in Loja province (Ecuador). Villena [22] found similar textures (sandy, loam, sandy loam, and clay loam) in guarango site-quality studies in Cajamarca (Peru); Gómez et al. [33] also described loam, clay, and clay loam textures in taxonomic and ecological research in Peru. Regarding Soil pH variable, it ranged from 5.82 to 6.77, at the lower limit of values reported in Peru (pH 5.0–12.0). However, optimal guarango production has been associated with pH 7.0–9.0 [33].

The highest ecogeographic diversity was found in areas with strong environmental heterogeneity, influenced by the Andes Mountain Range, watersheds, inter-Andean valleys, and multiple life zones [67]. This pattern was evident in the provinces of Imbabura and Loja. In Imbabura, the combination of altitudinal gradients and contrasting climates fosters high floristic richness and diverse traditional uses of native species [82]; this province conserves remnants of the diverse Chocó Biogeográfico humid forests [83]. On the other hand, Loja locates at the convergence of two biodiversity hotspots—the Tropical Andes and Tumbes–Chocó–Darién–Magdalena—where ecological complexity and limited documentation of native flora are noteworthy [84].

4.3. Correlation Between Morphological and Ecogeographic Data

According to Mantel test, no correlation was found between morphological and ecogeographic distance matrices (p = 0.141), indicating that morphological variation is not determined by spatial proximity among accessions. This pattern is likely driven by multiple underlying mechanisms. First, phenotypic plasticity may allow individuals to adjust their morphological traits in response to fine-scale environmental heterogeneity rather than broad ecological gradients, a mechanism widely documented in plants [85,86]. Second, historical biogeographical processes, including past dispersal routes or human-mediated seed movement, may have shaped current morphological differentiation independently of current ecogeographic structure [87,88]. Third, unmeasured micro-environmental factors (e.g., soil heterogeneity, localized water availability, understory light conditions) may exert stronger selective pressures than coarse scale ecogeographic variables [89]. A comparable situation was observed in a study on geographical variation and leaf/flower morphology in Embothrium coccineum, which found only a weak positive association between geographic distance and leaf morphology [90].

Maps derived from morphological and ecogeographic data for 39 guarango accessions showed that areas of high ecogeographic diversity do not necessarily coincide with high morphological diversity. According to Parra-Quijano et al. [27] ecogeographic diversity maps reflect differences among adaptive environments from which accessions originate, primarily based on abiotic variables. Such differences may reveal areas with germplasm adapted to divergent environmental conditions and potential sources of phenotypic and genotypic variability.

In Pichincha and the northern part of Chimborazo provinces, areas of medium ecogeographic diversity displayed high morphological diversity, suggesting that in certain locations, phenotypic expression may be more influenced by genetic and local micro-environmental factors than by broader ecological gradients. A similar pattern has been reported in other Andean but cultivated legume with high adaptive plasticity, such as Lupinus mutabilis, in Ecuador’s inter-Andean region [67].

While ecogeographical and morphological diversity helps identify environments with unique adaptive potential [27], relying solely on this criterion may overlook the current conservation status of these areas [91]. Ecogeographically and morphologically diverse sites may be simultaneously exposed to high levels of habitat loss, deforestation, or land-use change, which can compromise the long-term persistence of local populations [92]. Therefore, incorporating threat-based indicators—such as recent land-use change, deforestation dynamics, fire frequency, road expansion, or agricultural frontier growth—would substantially refine conservation prioritization [93]. Integrating indicators of adaptive value (ecogeographical and morphological diversity) with risk-based metrics provides a more realistic framework for germplasm conservation, ensuring that populations with both high adaptive relevance and high vulnerability are prioritized for in situ protection or urgent ex situ collection [94].

In the case of areas showing high morphological and ecogeographical diversity of guarango in Ecuador, many overlap with regions currently facing significant environmental pressures. For example, between years 1990 and 2020, provinces with key guarango diversity in the Inter-Andean region experienced substantial forest loss e.g., approximately 150,000 ha were deforested in Loja, followed by ~120,000 ha in Pichincha and ~100,000 ha in Bolívar, whereas the remaining seven provinces each lost <50,000 ha [95]. These trends indicate that some regions with high adaptive potential for guarango are also among the most threatened, underscoring the need to integrate ecogeographical and morphological information with explicit threat assessments to guide effective conservation and germplasm collection strategies.

The multivariate results for morphological and ecogeographic data demonstrated morphological variability and the absence of duplicates within the collection. However, it is pending the development of molecular studies to gain a comprehensive understanding of intraspecific variability [27,67]. Genetic studies are particularly relevant to determine whether the observed morphological variability truly reflects genetic differentiation rather than environmental effects [96]. This information would be crucial to understand plant adaptive mechanisms and rules of phenotypic variation, which in turn support germplasm collection, conservation, and evaluation [97].

This study faced some unavoidable limitations. First, the studied materials came out of limited number of seeds conserved at a gene bank, which also presented low germination rates (22–56%), limiting to a single site evaluation and low number of tree replications in the field. Second, the characterization was preliminary, as the evaluated trees were in a juvenile stage, preventing the inclusion of pod and seed descriptors in this paper, which are key traits for this species. Therefore, medium-term research will complement the phenotypic characterization of the pods and seeds, coupled with a chemical analysis of the polyphenol content across the entire collection. Furthermore, to validate the stability and adaptability of the material, it is essential to replicate the field experiment in other locations. Finally, molecular data were not included in this publication (which limits the inferences regarding genetic structure and diversity). However, the SSR analysis is under execution and will be included as part of a subsequent publication to complement the present findings.

5. Conclusions

Guarango variability is reflected in vigor-related traits such as total tree height and basal diameter. On the other hand, uniform traits across accessions—such as seed shape, color, and hilum position—may indicate low phenotypic variation in these descriptors. However, this pattern does not necessarily imply a lack of genetic variability, as it could also result from environmental canalization or stabilizing selection acting on seed morphology. This combination of variability and stability may be attributed to the phenotypic plasticity of the species and high gene flow within a genetically homogeneous sampling region. Further research on the germplasm’s productive stage is needed as descriptors for productive vegetative organs could not be registered, and it remains unknown. Molecular studies are also essential to assess intra- and inter-population variability of guarango in Ecuador.

No positive correlation was found between morphological and ecogeographic data, indicating that morphological diversity may or may not occur in homogeneous or heterogeneous ecosystems. The adaptability of guarango to diverse environments can be partly explained by its hardiness and tolerance to adverse abiotic factors, such as low-fertility soils and climate variables.

This research is the first morphological and ecogeographical characterization of the species in Ecuador. This new information will strengthen in situ and ex situ conservation efforts as well as to promote the use of the species in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.S. and Á.R.M.-A.; study design and supervision, F.A.S. and Á.R.M.-A.; material collection and field experiment maintenance, F.A.S.; data acquisition, F.A.S.; data curation and statistical analysis, F.A.S. and Á.R.M.-A.; result interpretation and preparation of the first manuscript draft, F.A.S., Á.R.M.-A., and M.B.D.-H.; writing—review and final editing, F.A.S., Á.R.M.-A., and M.B.D.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Field experiment, mobilization, and evaluation logistics were supported by the project FIASA-EESC-2024-022 “Conservation and Management of the INIAP Gene Bank”.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this publication, including the morphological and ecogeographical databases and the results of the data curation process performed using CAPFITOGEN 3, are publicly available in the guarango GitHub repository: https://github.com/FSigcha/Guarango (Commit ID: dda7b7e), accessed on 15 December 2025.

Acknowledgments

We thank INIAP and the University of Santiago de Compostela, particularly the doctoral program in Agriculture and Environment, for their technical guidance and academic support. Financial support was provided by the project FIASA-EESC-2024-022 “Conservation and Management of the INIAP Germplasm Bank”. We also express our gratitude to César Tapia for his technical assistance and to Mauricio Parra-Quijano for the training provided on the CAPFITOGEN3 program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPNI (International Plant Names Index). International Plant Names Index. Available online: https://www.ipni.org (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Villena, J. Variabilidad Morfológica de la Taya, Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze, en Bosques Naturales de Nueve Provincias de Cajamarca. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, I. Producción y Comercio de la Tara en el Perú; Dirección General de Políticas Agrarias: Lima, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, P.; Ulloa, C. Seed Plants of the High Andes of Ecuador: A Checklist. AAU Reports 34; Dept. of Systematic Botany Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; Aarhus University, Departamento de Ciencías Biológicas: Quito, Ecuador, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.; Prajapati, V.; Chandarana, C. Chemistry, Biological Activities, and Uses of Tara Gum. In Gums, Resins and Latexes of Plant Origin; Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, L. La Tara, Beneficios Ambientales y Recomendaciones para su Manejo Sostenible en Relictos de Bosque y Sistemas Agroforestales; CONDENSAN: Quito, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mancero, L. La Tara (Caesalpinia spinosa) en Perú, Bolivia y Ecuador: Análisis de la Cadena Productiva en la Región; Programa Regional ECOBONA—INTERCOOPERTION: Quito, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Orrillo, H.; Palomino-Rosillo, L.; Hilares-Vargas, S.; Aliaga-Pereyra, M.; Seminario-Cunya, A.; Abanto-Rodríguez, C. First Report of Tanaostigmodes Sp. as the Main Pest of Caesalpinia Spinosa: Morphological and Biological Aspects. Sci. Agropecu. 2021, 12, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, S.; Ramírez, K. Evaluación del Estado de Conservación de la Tara Caesalpinia spinosa en el Departamento de Ayacucho; Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales: Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Epiquin Rojas, M.L.; Román Peña, A.; Chichipe Vela, E.; Arce Inga, M. Evaluación de Carbono Total En Bosque de Tara (Caesalpinia spinosa Kuntze): Centro Poblado Señor de Los Milagros. Rev. Investig. Agroproducción Sustentable 2019, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, E. Estudio de los Factores para la Exportación de la Tara en polvo (Caesalpinia spinosa) Como Producto Natural Hacia Minnesota, Estados Unidos; año 2020. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Privada del Norte, Lima, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pedreschi, F.; Matus, J.; Bunger, A.; Pedreschi, R.; Huamán-Castilla, N.L.; Mariotti-Celis, M.S. Effect of the Integrated Addition of a Red Tara Pods (Caesalpinia spinosa) Extract and NaCl over the Neo-Formed Contaminants Content and Sensory Properties of Crackers. Molecules 2022, 27, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, F. La tara Caesalpinia spinosa (Mol.) O. Kuntze, especie prodigiosa para los sistemas agroforestales en valles interandinos. Acta Nova 2009, 4, 300. [Google Scholar]

- Narváez, A.; Calvo, A.; Troya, A. Las Poblaciones Naturales de la Tara (Caesalpinia spinosa) en el Ecuador: Una Aproximación al Conocimiento de la Diversidad Genética y el Contenido de Taninos por Medio de Estudios Moleculares y Bioquímicos; Programa regional ECOBONA: Quito, Ecuador, 2009; ISBN 978-9942. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, C.; Barona, N. El Guarango Una Opción Agroindustrial y de Exportación Para “Conservación Productiva”, 1st ed.; Freire, L., Ed.; Fundación desde el Surco—ECOBONA: Quito, Ecuador, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guamán, B. Evaluación de la Germinación de Semilla de Guarango (Caesalpinia spinosa) (Mol.) O. Kuntze Aplicando dos Métodos de Escarificación en la Comunidad Alacao, Guano, Chimborazo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Politécnica del Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzon, F.; Rios, L.W.A.; Cepeda, G.M.C.; Polo, M.C.; Cabrera, A.C.; Figueroa, J.M.; Hoyos, A.E.M.; Calvo, T.W.J.; Molnar, T.L.; León, L.A.N.; et al. Conservation and Use of Latin American Maize Diversity: Pillar of Nutrition Security and Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Agronomy 2021, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, G.A.; López-Feldman, A.; Yúnez-Naude, A.; Taylor, J.E. Genetic Erosion in Maize’s Center of Origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14094–14099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Santiago, J.; Nieto-Ángel, R.; Barrientos-Priego, A.F.; Rodríguez-Pérez, E.; Colinas-Leon, M.T.; Borys, M.W.; González-Andrés, F. Selección de Variables Morfológicas para la Caracterización del Tejocote (Crataegus spp.). Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2008, 14, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Onamu, R.; Solano, J.P.L.; Castellanos, J.S.; Rodríguez De La O, J.L.; Nieto, J.P. Análisis de marcadores morfológicos y moleculares en papa (Solanum tuberosum L.). Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2012, 35, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Villarreal, A. Caracterización morfológica de recursos fitogenéticos. Rev. Bio Cienc. 2013, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Villena, J. Variación Morfológica e Influencia de Factores Climáticos Sobre la Morfología de Fruto y Semilla de Tara spinosa en el Departamento de Cajamarca. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Alemán, F.; Canelas, C.; Ugarte, C. Validación de descriptores en poblaciones de Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze (tara) en los valles interandinos de Bolivia. Rev. Agric. 2015, 55, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Villena Velásquez, J.J.; Muñoz Chávarry, P.; Seminario, J.F.; Martínez Sovero, G. Caracteres Morfométricos Como Indicadores de Calidad de Sitio de Tara Spinosa (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae) En Cajamarca, Perú. Lilloa 2022, 59, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal, E. Distribución Altitudinal y Elaboración de Clave Dicotómica y Pictórica de Biotipos de Tara (Caesalpinia Spinosa). Biológica Huamangensis 2010, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Villena-Velásquez, J.J.; Seminario-Cunya, A.; Soto-Sánchez, S.; Valderrama-Cabrera, M.A.; Seminario, J.F. Seedling Descriptors and New Grouping of the Tara Spinosa Germoplasm from the Cajamarca Region, Peru. Bonplandia 2024, 33, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra Quijano, M.; Iriondo, J.M.; Torres, E.; López, F.; Phillips, J.; Kell, S. CAPFITOGEN3: A Toolbox for the Conservation and Promotion of the Use of Agricultural Biodiversity; Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021; ISBN 9789585050389. [Google Scholar]

- Vaca, J. Ecogeografía de la Agrobiodiversidad del Chocho (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet.) en el Ecuador. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, F. Evaluación de dos Métodos de Generación de Modelos de Distribución Potencial para Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze en Cuatro Cantones de la Provincia de Loja. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Veintimilla, J. Influencia de los Factores Geo-Ecológicos en la Distribución de las Especies Forestales Nativas del Cantón Catamayo, Provincia de Loja. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chirino, E.; Ruiz-Yanetti, S.; Vilagrosa, A.; Mera, X.; Espinoza, M.; Lozano, P. Morpho-Functional Traits and Plant Response to Drought Conditions in Seedlings of Six Native Species of Ecuadorian Ecosystems. Flora Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2017, 233, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, I. Respuesta ecofisiológica de Caesalpinia spinosa (Mol.) Kuntze a condicionantes abióticos, bióticos y de manejo, como referente para la restauración y conservación del bosque de nieblas de Atiquipa (Perú). Ecosistemas 2016, 25, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gómez, J.; Campos, J.; Felix, R.; Barbara, L. Estudio Taxonómico, Ecológico, Fitogenético y Manejo Agronómico de la Tara—Caesalpinia spinosa; Asociación Tecnología y Desarrollo: Lima, Peru, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Tacán, M.; Peña, G.; Tapia, C.; Paredes, N.; Lima, L. Guía Para el Manejo de los Recursos Fitogenéticos en Ecuador: Protocolos, 1st ed.; INIAP-FAO: Mejía, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neffa, V.G.S. Geographic Patterns of Morphological Variation in Turnera Sidoides Subsp. Pinnatifida (Turneraceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2010, 284, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteros-Altamirano, Á.; Tapia, C.; Paredes, N.; Roura, A.; Naranjo, E.; Tacán, M.; Sigcha, F.; Mora, V. Plant Genetic Resources in Ecuador. In Plant Gene Banks; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Játiva, S. Determinación del Contenido de Tanino Procedente del Guarango (Caesalpinia Spinosa) y Evaluación de Uso Como Fungicida. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Politécnica Nacional, Quito, Ecuador, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Sosa, R.; Lombardi Indacochea, I.; Gonzales Mora, H.E.; Figueroa Serrudo, C.; Calderón Rodríguez, A. Determinación de La Viabilidad de Semilla de Caesalpinia Spinosa (Molina) Kuntze y Su Correlación Con El Contenido de Goma y Tanino. Rev. For. Perú 2016, 31, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Ramírez, S.; Chalco-Sandoval, W.; Valarezo-Aguilar, K.; Ordóñez Gutiérrez, O. Tratamientos Pre-germinativos de Semillas de Caesalpinia spinosa (Mol) O. Kuntze con Distintos Sustratos en el Vivero de la Universidad Nacional de Loja. Bosques Latid. Cero 2023, 13, 43–55. Available online: https://revistas.unl.edu.ec/index.php/bosques/article/view/1868 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- ISTA (International Seed Testing Association). Reglas Internacionales Para El Análisis de Las Semillas 2016; International Seed Testing Association: Zurich, Suiza, 2016; Volume 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Portela De Oliveira, G.; Clarete Camili, E.; Magalhães Morais, O. Methodology for Tetrazolium in Cowpea Seeds. Investig. Agrar. 2018, 20, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogaça, C.A.; De Matos Malavasi, M.; Zucareli, C.; Malavasi, U.C. Aplicação do Teste de Tetrazólio em Sementes de Gleditschia amorphoides Taub. Caesalpinaceae. Rev. Bras. Sementes 2006, 28, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Ganadería Acuacultura y Pesca. Caracterización Edafoclimática para el Plan de Manejo Integral de la Granja Experimental INIAP-YACHAY; Coordinación General Del Sistema De Información Nacional (CGSIN): Quito, Ecuador, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, H.; López, A.; Carbajal, Y.; Siles, M. Análisis de variables morfolométricas de frutos de “tara “ provenientes de Yauyos y Ayacucho para identificar caracteres agromorfológicos de interés. Sci. Agropecu. 2016, 7, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge-Solís, J.; Echeverría-Beirute, F. Validación de descriptores para la caracterización morfológica de cinco materiales de Cas [Psidium friedrichsthalianum (O. Berg) Niedenzy] en Costa Rica. Agron. Costarric. 2023, 47, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dostert, N.; Roque, J.; Brokamp, G.; Cano, A.; La Torre, M.; Weigend, M. Datos botánicos de Tara Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze; Forma e Imagen: Lima, Peru, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bianciotto, V.T.; Fontana, M.L.; Luna, C.V. Carecterización Morfológica y Clave Dendrológica de Cuatro Especies Forestales del Arboretum de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias—Universidad Nacional del Nordeste (FCA-UNNE) Corrientes, Argentina. Folia Amaz. 2019, 28, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Horticultural Society. RHS Colour Chart, 5th ed.; Royal Horticultural Society: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rondeux, J. La Mesure Des Arbres et Des Peuplements Forestiers, 1st ed.; Les Presses Agronomiques de Genbloux: Gembloux, Bélgica, 2010; ISBN 978-84-8476-386-4. [Google Scholar]

- Batlle, I.; Tous, J. Carob Tree Ceratonia siliqua L. Promoting the Conservation and Use of Underutilized and Neglected Crops. 17; International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1997; ISBN 92-9043-328-X. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop [Software]; Release 10.8; Esri: Redlands, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rienzo, J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.; González, L.; Tablada, E.; Robledo, C. InfoStat 2020 [Software]; Professional Version 2020; InfoStat Group: Córdoba, Argentina, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Software]; Version 4.3.2; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. A Comparison of Some Methods of Cluster Analysis. Biometrics 1967, 23, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.A. The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, R.; Shimodaira, H. Pvclust: An R Package for Assessing the Uncertainty in Hierarchical Clustering. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M.; Hornik, K. Cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions [Software], R package Version 2.1.8.1; Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factorextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses, R package version 1.0.7; 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Kuhn, M. Caret: Classification and Regression Training [Software]; R package Version 6.0-94; Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN): Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=caret (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Mantel, N. The Detection of Disease Clustering and a Generalized Regression Appoach Cancer Research. Cancer Res. 1967, 27, 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, T.L.; Hidalgo, R. Análisis Estadístico de Datos de Caracterización Morfológica de Recursos Fitogenéticos; Instituto Internacional de Recursos Fitogenéticos: Cali, Colombia, 2003; ISBN 9290435437. [Google Scholar]

- Reynel, C.; Marcelo, J. Árboles de los Ecosistemas Forestales Andinos. Manual de Identificación de Especies, 1st ed.; Intercooperation Fundación Suiza para el Desarrollo y la Cooperación Internacional: Lima, Peru, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Orrillo, H.; Lobo, F.D.A.; Santos Silva Amorim, R.; Fernandes Silva Dionisio, L.; Nuñez Bustamante, E.; Chu-Koo, F.W.; López, L.A.A.; Arévalo-Hernández, C.O.; Abanto-Rodriguez, C. Increased Production of Tara (Caesalpinia Spinosa) by Edaphoclimatic Variation in the Altitudinal Gradient of the Peruvian Andes. Agronomy 2023, 13, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishel, C.; Arturo, R.; Milena, G.; Eduardo, L.; Alejandra, R. Coeficiente de cultivo de Caesalpinia spinosa (guarango) en etapa de vivero. Polo Conoc. 2022, 6, 340–352. Available online: https://polodelconocimiento.com/ojs/index.php/es/issue/view/95 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Chalampuente-Flores, D.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Ron, A.M.D.; Tapia Bastidas, C.; Sørensen, M. Morphological and Ecogeographical Diversity of the Andean Lupine (Lupinus Mutabilis Sweet) in the High Andean Region of Ecuador. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florián, E. Morfología y Biometría de la Vaina y Semilla de la “Tara” (Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina) Kuntze) del Valle de Cajamarca. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Villena Velásquez, J.J.; Seminario Cunya, J.F.; Cabrera, M.A.V. Variabilidad morfológica de la “tara” Caesalpinia spinosa (Molina.) Kuntze (Fabaceae), en poblaciones naturales de Cajamarca: Descriptores de fruto y semilla. Arnaldoa 2019, 26, 555–574. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?pid=S2413-32992019000200003&script=sci_abstract (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Orihuela, C. Evaluación de la Diversidad Genética de Tres Poblaciones de Caesalpinia spinosa Procedentes de Cajamarca, Junín y Ayacucho Mediante Marcadores Morfométricos de Frutos y Marcadores Moleculares RAPD”. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mancheno Cárdenas, M.X.; Malo, I.P.; León, M.D.; Muñoz, J.T.; Solorzano, J.J.; Rojas, J.S. Viability, Germination and in Vitro Growth of Caesalpinia Spinosa from Seeds at Different Phenological Stages. One Ecosyst. 2025, 10, e153308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, Â.; Castillo, M. Germination Rates of Four Chilean Forest Trees Seeds: Quillaja Saponaria, Prosopis Chilensis, Vachellia Caven, and Caesalpinia Spinosa. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iura, J.; Mello, O.; Barbedo, C.J.; Salatino, A.; De Cássia, R.; Figueiredo-Ribeiro, L. Reserve Carbohydrates and Lipids from the Seeds of Four Tropical Tree Species with Different Sensitivity to Desiccation. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2010, 53, 889–899. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Saritama, J.M.; Pérez Ruiz, C. Rasgos morfológicos de semillas y su implicación en la conservación ex situ de especies leñosas en los bosques secos Tumbesinos. Ecosistemas 2016, 25, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, R. Common Difficulties Encountered in Collecting Native Seed. In Revegetation with Native Species: Proceedings of de 1197 Society for Ecological Restoration Annual Meeting; Holzworth, L., Brown, R.W., Eds.; U.S. Deparment of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain: Ogden, UT, USA, 1999; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, F.A.O.; Fuzessy, L.; Phartyal, S.S.; Dayrell, R.L.C.; Vandelook, F.; Vázquez-Ramírez, J.; Tavşanoǧlu, Ç.; Abedi, M.; Naidoo, S.; Acosta-Rojas, D.C.; et al. Overcoming Major Barriers in Seed Ecology Research in Developing Countries. Seed Sci. Res. 2023, 33, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Gibson-Roy, P.; Trivedi, C.; Gálvez-Ramírez, C.; Hardwick, K.; Shaw, N.; Frischie, S.; Laverack, G.; Dixon, K. Collection and Production of Native Seeds for Ecological Restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, S228–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaña-Villegas, E.; Ramos-Herrera, S.; Hernández-Barajas, J.R.; Valdés-Manzanilla, A. Diseño del software de análisis de datos meteorológicos: Fase de prueba. Kuxulkab 2010, 16, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, G.G.; Yu, M. Morphological Response of Eight Quercus Species to Simulated Wind Load. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, R. Silvicultura y Comercialización de la Tara (Caesalpinia spinosa (Feuillée ex Molina) Kuntze). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Jaén, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Guidelines for Soil Description, 4th ed.; Food & Agriculture Organization: Roma, Italy, 2006; ISBN 9251055211. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez, P.; Pabón, G. Estudio etnobotánico de las especies de flora nativa representativa de la provincia de Imbabura. Axioma 2011, 7, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta, F.; Peralvo, M.; Baquero, F.; Bustamante, M.; Merino-Viteri, A.; Muriel, P.; Freile, J.; Torres, O.; Jaramillo, R. Áreas Prioritarias Para La Conservación de La Biodiversidad En El Ecuador Continental; Consorcio para el Desarrollo Sostenible de la Ecorregión Andina: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Mendoza, Z. Biodiversidad de La Provincia de Loja, Ecuador. Arnaldoa 2017, 24, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicotra, A.B.; Atkin, O.K.; Bonser, S.P.; Davidson, A.M.; Finnegan, E.J.; Mathesius, U.; Poot, P.; Purugganan, M.D.; Richards, C.L.; Valladares, F.; et al. Plant Phenotypic Plasticity in a Changing Climate. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio-López, K.; Beckage, B.; Scheiner, S.; Molofsky, J. The Ubiquity of Phenotypic Plasticity in Plants: A Synthesis. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 5, 3389–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, A.; Ronce, O.; Robledo-Arnuncio, J.J.; Guillaume, F.; Bohrer, G.; Nathan, R.; Bridle, J.R.; Gomulkiewicz, R.; Klein, E.K.; Ritland, K.; et al. Long-Distance Gene Flow and Adaptation of Forest Trees to Rapid Climate Change. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cui, C.; Shen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X. Morphological Variation and Its Correlation with Bioclimatic Factors in Odorrana Graminea Sensu Stricto. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1139995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Gianoli, E.; Gómez, J.M. Ecological Limits to Plant Phenotypic Plasticity. New Phytol. 2007, 176, 749–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalcoff, V.R.; Ezcurra, C.; Aizen, M.A. Uncoupled Geographical Variation between Leaves and Flowers in a South-Andean Proteaceae. Ann. Bot. 2008, 102, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxted, N.; Brehm, J.M.; Kell, S. Resource Book for the Preparation of National Plans for Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives and Landraces; Roma, Italy, 2013. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/PGR/PubPGR/ResourceBook/TEXT_ALL_2511.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Belote, R.T.; Barnett, K.; Dietz, M.S.; Burkle, L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Dreiss, L.; Aycrigg, J.L.; Aplet, G.H. Options for Prioritizing Sites for Biodiversity Conservation with Implications for “30 by 30”. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 264, 109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Deus Vidal Junior, J.; Mori, G.M.; Cruz, M.V.; da Silva, M.F.; de Moura, Y.A.; de Souza, A.P. Differential Adaptive Potential and Vulnerability to Climate-Driven Habitat Loss in Brazilian Mangroves. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2022, 3, 763325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Santos, R.; Hernández-Sandoval, L.; Parra-Quijano, M. Spatial Analysis of the Ecogeographic Diversity of Wild Creeping Cucumber (Melothria Pendula L.) for In Situ and Ex Situ Conservation in Mexico. Plants 2024, 13, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio del Ambiente Agua y Transición Ecológica. El Estado de los Bosques en el Ecuador Continental 1990–2022; Consorcio para el Desarrollo Sostenible de la Ecorregión Andina: Quito, Ecuador, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chalampuente, D. Estudio de la Diversidad Morfológica y Ecogeográfica en tres Cultivos Andinos del Ecuador: El Caso del Tarwi (Lupinus mutabilis Sweet.), jícama (Smallanthus sonchifolius [Poepp. & Endl.] H. Robinson), y miso (Mirabilis expansa Ruiz & Pav. Standley.); Universidad Santiago de Compostela: Lugo, España, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Guo, Q.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zuo, W.; Long, C. Estimation of Morphological Variation in Seed Traits of Sophora Moorcroftiana Using Digital Image Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1185393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).