Abstract

The AP2/ERF (APETALA2/ethylene-responsive factor) superfamily is one of the largest transcription factor families in plants and is not only vital for plant growth and development but also participates in responding to various abiotic stresses. However, few studies have investigated the function of the AP2/ERF gene family in natural rubber (NR) biosynthesis in Hevea brasiliensis. Here, 174 HbAP2/ERF genes were identified genome-wide and classified into 18 subclades based on gene-conserved structure and phylogenetic analysis. Gene duplication analysis revealed that 7 tandem and 100 segmental duplication events were major drivers of this gene family. Cis-element analysis in HbAP2/ERF promoters identified light-, hormone-, stress-, and development-associated cis-elements. Tissue-specific expression profiles revealed that 160 HbAP2/ERFs were expressed in at least one tissue. The protein–protein interaction network identified 59 potential interactions among the HbAP2/ERFs. Critically, dual-luciferase reporter assays confirmed that two key regulators exhibit distinct regulatory modes on NR biosynthesis-related genes: HbAP2/ERF25 significantly repressed the transcriptional activities of HbMVD1, HbCPT7, and HbSRPP1, whereas HbAP2/ERF46 repressed HbMVD1 but activated HbHMGR1, HbFPS1, and HbSRPP1. These findings reveal the complex regulatory network of HbAP2/ERFs in NR biosynthesis, establish a comprehensive framework for understanding their evolution and functional diversification, and provide novel molecular targets for genetic improvement of NR yield in rubber tree breeding and metabolic engineering.

1. Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) play crucial roles in regulating plant growth, development, and stress responses. Among them, the APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element-binding factor (AP2/ERF) family stands as one of the largest and most diverse groups in plants [1]. This special type of TFs is characterized by one or more AP2 domains, containing the YRG (DNA-binding) and RAYD (structural stabilization) sub-motifs, which specifically bind to GCC-box (AGCCGCC) and DRE/CRT (ACCGAC) cis-elements in the promoter of target genes [2]. Based on structural characteristics and functional divergence, the AP2/ERF superfamily is generally divided into five subfamilies: dehydration-responsive element-binding (DREB), ethylene-responsive element-binding protein (ERF), APETALA2 (AP2), related to ABI3/VP (RAV), and Soloists [3]. The sizes of the AP2/ERF gene family vary among species, with 147 members in Arabidopsis thaliana, 170 in Oryza sativa [4], 112 in Prunus sibirica [5], 135 in Rosa chinensis [6], and 200 in Populus trichocarpa [7]. In Hevea brasiliensis, Duan et al. identified 173 AP2/ERF contigs through in silico analysis of the draft genome based on the amino acid sequence of the conserved AP2 domain [8].

AP2/ERF TFs have been extensively characterized for their roles in plant growth, stress responses, and secondary metabolism across diverse species—including their involvement in hormone signaling and metabolic pathway regulation [9]. In stress responses, members like ERF2 and ERF5 mediate β-aminobutyric acid (BABA)-induced resistance (BABA-IR) by regulating salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) pathways—with species specificity: Arabidopsis thaliana ERFs positively regulate SA signaling, while Hordeum vulgare ERF2 promotes JA pathways but represses SA-related genes. In development, AP2 class members control A. thaliana floral transition, mediating floral organ identity and meristem maintenance via feedback networks (e.g., miR156/miR172 axis). Notably, BABA reshapes AP2/ERF expression to coordinate plant defense and development (e.g., flowering delay), underscoring its role in linking stress adaptation and growth [10,11]. Two AP2/ERF members, AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6, have been shown to regulate shoot and flower development by modulating auxin polar transport [12]. PUCHI, an Arabidopsis AP2/ERF gene, was involved in lateral root initiation and development by regulating auxin signaling [13]. In rice, the crown rootless 5 mutant displayed fewer crown roots due to the loss of CRL5, a key AP2/ERF member that balances the auxin and cytokinin signaling pathways [14]. In addition to developmental regulation, AP2/ERF TFs serve as core regulators of response to stresses. For instance, AtDREB1B/CBF1, AtDREB1C/CBF2, and AtDREB1A/CBF3 were involved in low-temperature signal transduction pathways [15,16]. JcERF1, cloned from the woody oil plant Jatropha curcas L., has been demonstrated to enhance salt tolerance in transgenic lines [17]. GmERF5 and GmERF113 imparted resistance to Phytophthora sojae by upregulating the expressions of defense-related genes, including PR1-1, PR10, and PR10-1 genes [18,19]. Recent evidence indicated that AP2/ERF TFs were involved in regulating the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In Salvia miltiorrhiza, SmERF1b-like binds to the GCC-box motif in the promoter of SmKSL1 and activates the biosynthesis of tanshinone [20]. In Dendrobium officinale, DoAP2/ERF89 activated the terpene synthase gene DoPAES and participated in the β-patchoulene biosynthesis [21].

Natural rubber (NR) is a polyisoprene polymer [22] that is widely used in industry owing to its superior resilience, heat dispersion, and durability [23]. Although over 2500 plant species can produce NR, the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) remains the sole commercial source worldwide [24]. In the rubber tree, NR is synthesized and stored in laticifers, specialized bark tissues whose cytoplasm, known as latex, contains 30–50% NR [25,26]. In the rubber tree, although the first AP2/ERF family was reported in 2013, the severe fragmentation of the genome has greatly affected the completeness and accuracy of the family members’ identification. Recently, several high-quality chromosome-level rubber tree genomes have been reported, providing a new perspective for the precise analysis of the AP2/ERF family. In this study, we performed a genome-wide identification and characterization of the H. brasiliensis AP2/ERF family (designated HbAP2/ERF), defining their phylogenetic classification, gene duplication patterns, and promoter cis-element profiles. We further analyzed their tissue-specific expression patterns and protein–protein interaction networks to prioritize candidates with potential roles in NR biosynthesis. Finally, using dual-luciferase reporter assays, we validated the regulatory activity of key HbAP2/ERF members on core NR biosynthesis genes, thereby modulating NR biosynthesis. These results provided theoretical insights to guide the high-quality rubber tree breeding through genetic engineering.

2. Materials and Methods

First, bioinformatics approaches (genome search, duplication analysis, promoter analysis, expression analysis, and PPI network) were used to identify AP2/ERF family members in Hevea brasiliensis and predict the properties and functions of these genes. Subsequently, the transcriptional activity of HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 towards natural rubber biosynthesis-related proteins in Hevea brasiliensis was verified via dual-luciferase assay.

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of AP2/ERFs in Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis)

AP2/ERF proteins in the Hevea brasiliensis CATAS8-79 genome (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7123623, accessed on 17 October 2025) were identified via Hidden Markov Model (HMM) analysis using the AP2 domain profile (PF00847) from PFAM (version 37.2). The HMM search was performed with HMMER (version 3.0, http://www.hmmer.org/, accessed on 17 October 2025) using an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5. In parallel, Arabidopsis AP2/ERF protein sequences (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000001735.4/, accessed on 17 October 2025) were used for BLASTP searches against the rubber tree protein database, and hits with E values less than 1 × 10−10 were retained for further analysis. Both HMM Search and BLASTP used low-complexity filtering. All hits obtained from HMM and BLASTP were merged, and the presence of the AP2 domain in each candidate sequence was verified using SMART (version 9, http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/, accessed on 17 October 2025), PFAM, and CDD search (version 3.2.1, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi, accessed on 17 October 2025). Transmembrane domains and signal peptides were predicted using TMHMM (version 2.0, https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/, accessed on 17 October 2025) and Phobius (version 1.01, http://phobius.sbc.su.se/, accessed on 17 April 2025), respectively. Protein physicochemical properties, including molecular weight, isoelectric point, and amino acid length, were calculated using ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 15 October 2025).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of 147 Arabidopsis AP2/ERFs and 174 Hevea brasiliensis AP2/ERFs was performed using Clustal Omega (version 1.2.2, http://www.clustal.org/omega/, accessed on 17 October 2025). An unrooted phylogenetic tree was then constructed in MEGA 11 using the maximum-likelihood method with 500 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree was visualized with the TVBOT online tool (version 2.6.1, https://www.chiplot.online/tvbot.html, accessed on 17 October 2025) [27].

2.3. Chromosomal Localization, Conserved Motif, and Gene Structure Analysis

Genomic data of HbAP2/ERFs were extracted from the rubber tree genome database; their chromosomal locations and gene structures were visualized with TBtools (version 2.225) [28]. Conserved motifs in HbAP2/ERFs were identified with the MEME (version 5.5.7, https://meme-suite.org/meme/, accessed on 17 October 2025) with the site distribution set to zero or one occurrence per sequence (ZOOPS) and the maximum number of motifs set to 10, while other parameters remained at default settings.

2.4. HbAP2/ERF Duplication and Synteny Analysis

For identification of gene duplications, the protein sequences of 174 HbAP2/ERFs were aligned using BLASTP (E-value < 1 × 10−5). The MCScanX toolkit integrated with TBtools (version 2.225) was used to detect the duplication pattern of HbAP2/ERF. Genes located within 200 kb of each other and sharing >70% sequence similarity were defined as tandem duplications. A synteny plot was drawn using the circos program to illustrate duplicated rubber tree gene pairs and the synteny blocks of orthologous AP2/ERF genes between Hevea brasiliensis and Arabidopsis thaliana (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000001735.4/, accessed on 17 October 2025), Populus tomentosa Carr. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_018804465.1/, accessed on 17 October 2025), and Manihot esculenta Crantz (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_001659605.2/, accessed on 17 October 2025). To evaluate gene divergence following duplication, synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates were calculated for each duplicated gene pair using the Ka/Ks Calculator 2.0 tool integrated with TBtools.

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Regulatory Elements of HbAP2/ERFs

The 2 kb upstream promoter sequences of the HbAP2/ERF genes were extracted from the rubber tree genome and analyzed using the PlantCARE database (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 17 October 2025) with default parameters. The minimum width of motifs was 6, and the maximum width was 50. Common consensus elements (e.g., TATA-box, CAAT-box) were filtered out because they just maintain basal gene housekeeping expression, while functional cis-elements were retained for further analysis.

2.6. Tissue-Specific HbAP2/ERFs Expression Patterns

Based on published transcriptome data for seven tissues (cambium, inner bark, primary latex, secondary latex, female flower, male flower, and leaf) from the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/, accessed on 17 October 2025) under project number PRJCA004986. After removing adapters, the clean reads were mapped to the CATAS8-79 genome using HISAT2 (version 2.2.1) [29], and gene expression levels were quantified as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments) using StringTie (version 2.2.3) [30]. Expression profiles of HbAP2/ERFs were obtained and visualized using TBtools (version 2.2.2.5).

2.7. Protein–Protein Interactions of HbAP2/ERFs

The protein–protein interaction network of HbAP2/ERFs was established via STRING (version 12.0, https://string-db.org, accessed on 17 October 2025) with default parameters (required score: 0.4, FDR stringency: 0.05) and Arabidopsis thaliana as the reference organism. The resulting network was further visualized and analyzed in Cytoscape (version 3.9.1) using a grid layout model.

2.8. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

The dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed following the method of Sherf et al. [31]. The transcription factors HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46, along with the promoters of HbHMGR1, HbMVK1, HbMVD1, HbGPS1, HbFPS1, HbSRPP1, and HbCPT7, were cloned previously (primers used to clone these sequences are recorded in Table S1). Transcription factors were inserted into pCambia2300-35S to generate 35S::HbAP2/ERF25 and 35S::HbAP2/ERF46, while promoters were inserted into pGreen Ⅱ 0800-LUC to obtain HbHMGR1pro::LUC, HbMVK1pro::LUC, HbMVD1pro::LUC, HbGPS1pro::LUC, HbFPS1pro::LUC, HbSRPP1pro::LUC, and HbCPT7pro::LUC. Amplicons of the expected size were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) for Sanger sequencing to confirm the insert sequence. Correctly sequenced plasmids were subsequently extracted and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 (harboring the psoup plasmid) strains. Agrobacterium infiltration was performed following the protocol of Zhu et al. [32]. LUC activity was measured according to the manual of the dual-luciferase reporter gene assay kit (Yeasen, 11402ES80), and luminescence was detected with a living imaging apparatus. For each combination, at least three biological replicates were performed.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Descriptive statistical data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from at least three independent biological replicates. For comparisons between two groups, the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences. For multiple group comparisons, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, SAS 6.11) followed by Duncan’s multiple range test or Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. Statistical significance was defined as p > 0.05 (Ns), p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). All statistical graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9.0, with data visualization optimized based on the distribution characteristics of experimental data1.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Characterization of HbAP2/ERFs in Rubber Tree

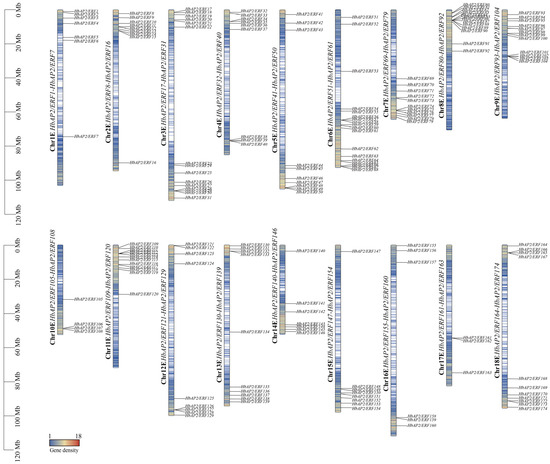

To systematically characterize the HbAP2/ERF family in rubber tree, we used the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) of the AP2/ERF domain (PF00847) to search for HbAP2/ERF and obtained a total of 174 candidate genes. Pfam and NCBI-CDD analyses confirmed that all candidate AP2/ERF proteins contained intact AP2/ERF domains. The genes were designated HbAP2/ERF1 to HbAP2/ERF174 according to their chromosome mapping (Figure 1, Table S1), which revealed their non-random distribution across 18 chromosomes: chromosome 6 harbored the most members (18), while chromosome 17 contained the fewest (3). The pattern suggests preferential expansion of the family on specific chromosomes.

Figure 1.

Location of HbAP2/ERF genes on the chromosome of the rubber tree. The chromosome numbers are labeled on the left side of each chromosome. The gene density is represented by the color scale. The leftmost scale represents the chromosome length (Mb).

Physicochemical property analysis indicated that the molecular weights of the 174 HbAP2/ERFs ranged from 9.88 kDa for HbAP2/ERF132 to 133.31 kDa for HbAP2/ERF163, with an average weight of 35.20 kDa. The isoelectric points (PIs) varied between 4.51 for HbAP2/ERF162 and 10.83 for HbAP2/ERF35. Predicted aromaticity values were observed to range from 0.04 for HbAP2/ERF10 to 0.12 for HbAP2/ERF117. Most of the HbAP2/ERFs exhibited instability indices exceeding 40, indicating a tendency toward instability, with the exceptions being HbAP2/ERF12 (39.12), HbAP2/ERF41 (38.27), HbAP2/ERF42 (38.64), HbAP2/ERF (39.61), HbAP2/ERF96 (37.59), HbAP2/ERF98 (37.75), HbAP2/ERF119 (36.14), and HbAP2/ERF132 (33.07). Furthermore, signal-peptide (SP) analysis suggested that 11 members, including HbAP2/ERF26, HbAP2/ERF28, HbAP2/ERF52, HbAP2/ERF64, HbAP2/ERF82, HbAP2/ERF84, HbAP2/ERF122, HbAP2/ERF141, HbAP2/ERF155, HbAP2/ERF159, and HbAP2/ERF163, contained SPs. This suggests their potential involvement in extracellular signal transduction pathways.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of Rubber Tree HbAP2/ERFs

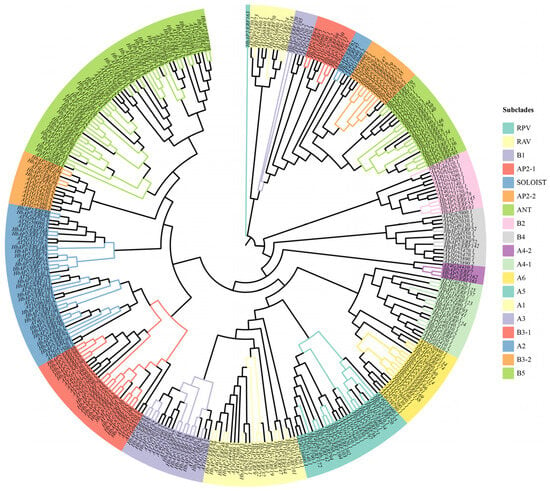

To investigate the evolutionary relationships among AP2/ERF family members, we constructed an unrooted maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree that included 174 HbAP2/ERFs and 147 AtAP2/ERFs. The phylogenetic analysis classified the HbAP2/ERFs into 19 distinct subclades, following the naming conventions of their Arabidopsis homologs (Figure 2, Table S2). To evaluate the structural diversity of the HbAP2/ERF genes, the full-length cDNA sequences were compared with the corresponding genomic DNA sequences to determine the numbers and positions of exons and introns within each gene. Notably, the RPV subclade exhibited significant divergence in its AP2 domain compared to all AtAP2/ERFs. The subclades varied markedly in size, with subclade B5 being the largest, comprising 33 HbAP2/ERFs and 19 AtAP2/ERFs. Conserved domain analysis identified 10 motifs in HbAP2/ERFs (Figure 3A, Figures S1 and S2). Motifs 1 and 5 were present in almost all HbAP2/ERFs and represented conserved structural domains characterized by sequence elements such as YRG and RAYD [33]. By contrast, motif 10 was restricted to the B3-1 and A2 subclades, whereas motifs 6 and 9 were shared by the AP2, ANT, and soloist subclades. These features serve as useful markers for distinguishing subclades. Analysis of the exon–intron structure indicated significant differences across subclades while demonstrating considerable conservation within individual subclades. For example, subclades B2 and B3-2 contained fewer than three exons, whereas subclades ANT, AP2, SOLOIST, and RPV contained more than ten exons (Figure 3B and Figure S2). These structural analyses of HbAP2/ERFs reveal that subclade-specific divergence in conserved motifs, AP2 domain sequences, and exon–intron architectures reflects functional specialization of the family, while intra-subclade structural conservation maintains the evolutionary stability of core AP2/ERF functions.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of 174 HbAP2/ERFs and 147 AtAP2/ERFs. Different color bands represent distinct subclades. AtAP2/ERF branches within each subclade are shown in black.

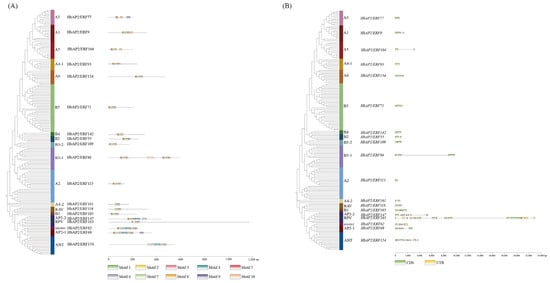

Figure 3.

Analysis of conserved motifs and gene structure of HbAP2/ERFs in the rubber tree. (A) Conserved motif of HbAP2/ERF proteins. Ten conserved motifs are shown in different colors. (B) Exon–intron organization of HbAP2/ERF coding sequences (CDSs). Green, CDSs; yellow, untranslated regions (UTRs).

3.3. Duplication and Synteny Analysis of HbAP2/ERF Genes

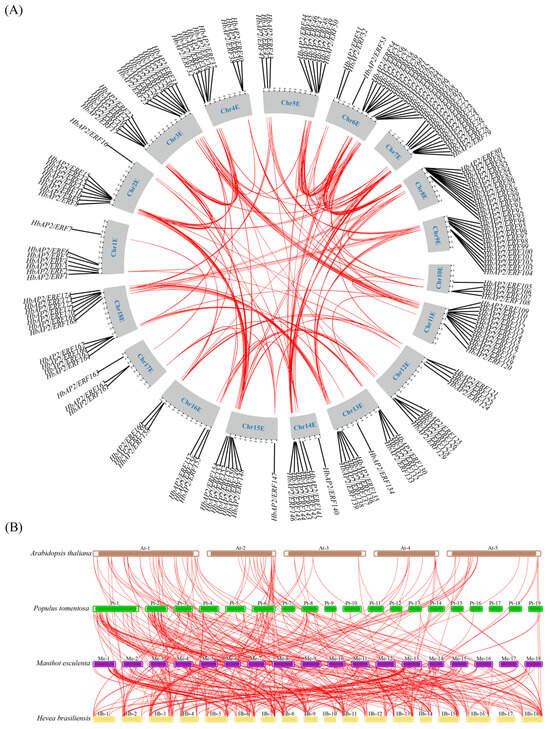

Gene duplication is a major driving force of genome evolution. Analyses of segmental and tandem duplications provide insights into the mechanisms underlying gene family expansion. Gene duplication events were analyzed using the MCScanX function implemented in TBtools (version 2.225) to explore the evolutionary mechanisms driving the expansion of the HbAP2/ERF family. We detected seven tandem duplication events on chromosomes 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 18. Intraspecific collinearity analysis revealed that 65.52% (114/174) of the HbAP2/ERFs were involved in 100 segmental duplication events (Figure 4A, Table S3). The Ka/Ks ratio was assessed for selective pressure: values > 1 indicate positive selection, <1 indicate negative selection, and =1 indicate neutral evolution. For both types of duplicated HbAP2/ERF homologous pairs, Ka/Ks ratios were below 1 (ranging from 0.05 to 0.53), suggesting that these genes have undergone purifying selection, thereby maintaining their functional integrity while allowing for subtle diversification.

Figure 4.

Synteny and collinearity analysis of AP2/ERFs. (A) Synteny of HbAP2/ERFs in the rubber tree. The red lines indicate the duplicated gene pairs. (B) Collinearity of AP2/ERF families among four species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus tomentosa, Manihot esculenta, and Hevea brasiliensis). The red lines expand the collinearity of AP2/ERF gene pairs.

To further investigate the mechanisms of expansion, we conducted a comparative synteny analysis involving the rubber tree and three other species (Arabidopsis thaliana, Populus tomentosa, and Manihot esculenta). This analysis revealed 157 collinear AP2/ERF gene pairs between the rubber tree and cassava, followed by 150 pairs with poplar and 113 pairs with Arabidopsis, suggesting a closer genetic relationship between the rubber tree and cassava (Figure 4B). Interestingly, HbAP2/ERFs on chromosome 17 displayed only 9 syntenic relationships with the other three species, indicating distinct evolutionary trajectories for these genes and chromosomes within the rubber tree.

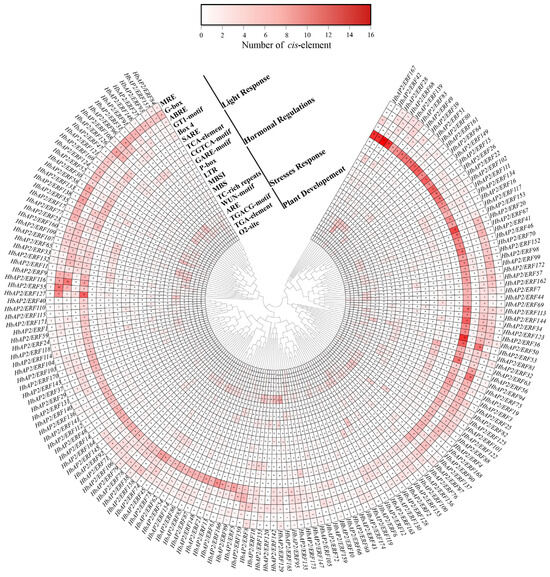

3.4. Cis-Regulatory Element Analysis of HbAP2/ERFs

Cis-acting elements in the ~2 kb promoter of HbAP2/ERFs were identified using PlantCARE. A total of 19 functional cis-acting elements were identified and categorized into four groups: plant development, biotic/abiotic stress response, hormonal regulations, and light response (Figure 5, Figure S3 and Table S4). Among them, Box 4, GT1-motif, ABRE, and G-box were the most abundant elements, which were found in the light response category, whereas TGA-element was the most frequent in plant development, LTR in low-temperature response, ARE in biotic/abiotic stress responses, and CGTCA-motif in hormonal regulation. Notably, the number of cis-acting elements varied significantly among HbAP2/ERF promoters, ranging from as few as six in HbAP2/ERF66 to as many as 41 in HbAP2/ERF50. These results suggest that HbAP2/ERFs are involved in growth, development, and stress responses in the rubber tree.

Figure 5.

Statistical analysis of the cis-acting elements in HbAP2/ERF promoter regions. The number of cis-acting elements is displayed in shades of red.

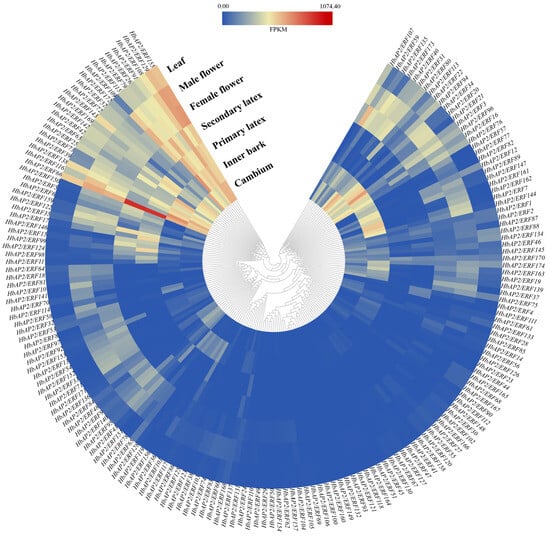

3.5. Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of HbAP2/ERFs

The HbAP2/ERF gene family is closely associated with plant growth and development [10]. To further determine the expression patterns of HbAP2/ERFs, we analyzed the transcriptome data of seven tissues (cambium, inner bark, primary latex, secondary latex, female flowers, male flowers, and leaves). A total of 169 genes were expressed in at least one of those 7 tissues, except for HbAP2/ERF100, HbAP2/ERF132, HbAP2/ERF106, HbAP2/ERF149, and HbAP2/ERF160. Sixty genes showed constitutive expression across all tissues (Figure 6). Flower tissues contained the highest number of expressed genes (142 in both male and female flowers), whereas latex tissues contained the lowest (74 in primary latex and 84 in secondary latex). Several genes displayed tissue-specific expression, including HbAP2/ERF111, which was expressed exclusively in second latex; HbAP2/ERF45 and HbAP2/ERF51 in inner bark; and HbAP2/ERF69, HbAP2/ERF102, HbAP2/ERF105, and HbAP2/ERF166 in leaves. Interestingly, HbAP2/ERF66 showed extremely high expression in both primary latex and secondary latex, suggesting a crucial role in regulating rubber synthesis. Comparative analysis of gene expression in latex tissues showed that HbAP2/ERF33, HbAP2/ERF53, HbAP2/ERF81, HbAP2/ERF82, HbAP2/ERF94, HbAP2/ERF139, and HbAP2/ERF163 were only expressed in primary latex. On the contrary, HbAP2/ERF7, HbAP2/ERF20, HbAP2/ERF21, HbAP2/ERF28, HbAP2/ERF31, HbAP2/ERF54, HbAP2/ERF68, HbAP2/ERF75, HbAP2/ERF84, HbAP2/ERF88, HbAP2/ERF89, HbAP2/ERF92, HbAP2/ERF111, HbAP2/ERF113, HbAP2/ERF117, HbAP2/ERF145, and HbAP2/ERF168 were only expressed in secondary latex. HbAP2/ERF17, HbAP2/ERF99, HbAP2/ERF115, HbAP2/ERF142, and HbAP2/ERF169 were significantly downregulated in secondary latex compared to primary latex, while HbAP2/ERF15, HbAP2/ERF35, HbAP2/ERF79, HbAP2/ERF109, and HbAP2/ERF150 were significantly upregulated, suggesting distinct regulatory roles in latex metabolism. The expression patterns of HbAP2/ERFs in latex indicate that their functions are likely to be directly involved in the transcriptional regulation of NR biosynthesis.

Figure 6.

Expression pattern of HbAP2/ERFs in seven tissues with hierarchical clustering. Colors from red to blue indicate higher and lower levels, respectively.

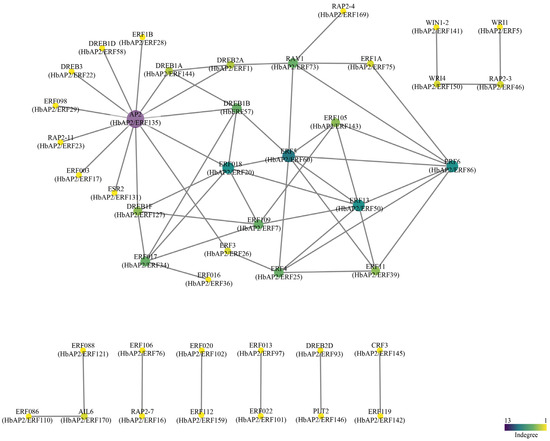

3.6. Prediction of the HbAP2/ERF Protein–Protein Interaction Network

To explore the functional interactions of HbAP2/ERFs, we established a protein–protein interaction network utilizing Arabidopsis orthologs in the STRING database. This analysis uncovered 59 potential interactions (Figure 7, Table S5). Among these, 13 HbAP2/ERFs were predicted to interact with HbAP2/ERF135, a homolog of Arabidopsis AP2, which is involved in flower and seed development [34,35]. HbAP2/ERF60 interacts with eight HbAP2/ERFs, is a homolog of AtERF5, and functions as an activator of GCC-box-dependent transcription in Arabidopsis leaves [36]. DREB is a key transcriptional activator in response to chilling tolerance [15]. In the present study, we detected a total of 11 potential interactions for three DREB homologs in the rubber tree.

Figure 7.

Characterization of protein structure and protein–protein interaction profiles. Protein–protein interaction networks were constructed using STRING (version 12.0). The degree of interaction is represented by both the color and the size of each node.

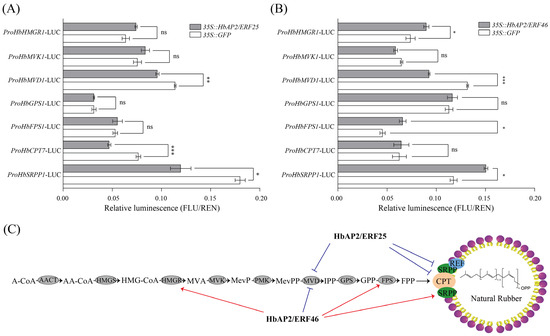

3.7. HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 Regulated Multiple NR Biosynthesis-Related Genes

Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (MVD) is a key enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of NR. We previously screened two potential transcription factors (HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46) for HbMVD1 by Y1H assay. To investigate their role in the regulation of NR biosynthesis, a comprehensive luciferase transcriptional activation assay related to eight NR biosynthesis-related genes was performed. It was clearly shown that HbAP2/ERF25 significantly repressed the transcriptional activities of HbMVD1, HbCPT7, and HbSRPP1 (Figure 8A). For HbAP2/ERF46, the transcriptional activity of HbMVD1 was repressed, while HbHMGR1, HbFPS1, and HbSRPP1 were activated (Figure 8B), suggesting the complex regulatory network of HbAP2/ERF in NR biosynthesis (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

Effect of HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 on the activation of the NR biosynthesis gene promoter. (A,B) Promoter activity assays. The relative LUC activities (LUC/REN) were normalized to the reference Renilla (REN) LUC. Error bars represent the SD of three biological replicates. ns, not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001. (C) Schematic representation of NR biosynthesis genes regulated by HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 in rubber tree laticifer cells. Red lines indicate activation, and blue lines indicate inhibition.

4. Discussion

Thousands of genes are involved in varied processes in plants. AP2/ERF is one of the largest transcription factor families and plays pivotal roles in plant development as well as in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses [1]. With the rapid development of plant genomics, AP2/ERF gene families have been systematically identified in many species, including Triticum aestivum (117) [37], Hordeum vulgare (121) [38], Zea mays (167) [39], Glycine max (301) [40], Malus domestica (259) [41], Brassica rapa (291) [42], and Solanum lycopersicum (173) [43]. In 2013, Duan identified 173 contigs containing the AP2/ERF domain by analyzing the rubber tree transcript sequence database [8]. However, the severe fragmentation of the contigs has greatly affected the accuracy of the family members’ identification in the rubber tree. Here, we systematically delineate the genomic landscape and functional potential of the HbAP2/ERF family, with a focus on identifying core regulators that shape NR biosynthesis. We further speculate that two members, HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46, may control NR biosynthesis by directly or indirectly regulating key NR biosynthesis genes.

A total of 174 candidate members were identified based on genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF in rubber tree CATAS8-79 (Figure 1, Table S1). Comparative analysis showed that the size of the HbAP2/ERF family is larger than that in Arabidopsis thaliana [4], Solanum lycopersicum [43], Oryza sativa [4], Triticum aestivum [37], Hordeum vulgare [38], Zea mays [39], and Prunus sibirica [5], but smaller than those in Populus trichocarpa [7], Glycine max [40], Malus domestica [41], and Brassica rapa [42]. Such interspecific variation in AP2/ERF family size can likely be attributed to evolutionary processes such as whole-genome duplications and polyploidization events. The dominance of segmental duplication (100 events) over tandem duplication (seven events) in driving HbAP2/ERF family expansion reflects adaptive evolution (Figure 4A), with latex-enriched segmentally duplicated pairs likely undergoing neofunctionalization for NR-specific roles. These proportions are comparable to those reported for the AP2/ERF gene family in Prunus sibirica [5], suggesting that gene duplication plays a conserved and significant role in the expansion of the AP2/ERF family.

In response to stresses, plants employ multiple strategies, such as activating the antioxidant system and increasing the contents of characteristic metabolites [44]. The expansion or contraction of gene families is a core driver of plant evolution for adapting to long-term environmental changes [45]. The 174 HbAP2/ERFs were classified into 18 subclades based on Arabidopsis homologs, plus one rubber-tree-specific subclade (RPV, HbAP2/ERF163). The pattern is indicative of lineage-specific functional diversification to support rubber tree-specific biological processes. HbAP2/ERF163 has the longest gene structure among 174 members. Cis-regulatory element analysis detected five low-temperature response (LTR) elements in the HbAP2/ERF163 promoter, indicating that this may be associated with the temperature response of the rubber tree in tropical regions. Functional studies in Arabidopsis have defined conserved roles of AP2/ERF members. RAP2-3, a member of the B3 subclade, mediates root hypoxia tolerance and root development under low-oxygen conditions, while ERF096 regulates heat stress responses [46]. Our ortholog annotation identified HbAP2/ERF109 as the Arabidopsis RAP2-3 ortholog and HbAP2/ERF111 as the ERF096 ortholog (Figure 2), with distinct tissue expression patterns (HbAP2/ERF109 expressed across all seven tissues; HbAP2/ERF111 latex-specific) further illustrating functional divergence from model plant homologs. The evolutionary and orthologous context underscores the biological significance of tissue-specific expression in HbAP2/ERFs: the enrichment of 92 HbAP2/ERFs (including HbAP2/ERF25 and 46) in latex tissue (vs. leaves/roots) is not just a spatial pattern but evidence of laticifer-specific transcriptional reprogramming.

Transcription factors regulate gene expression and play a key role in biological processes. Recently, several TFs have been reported to modulate the genes involved in NR biosynthesis. For example, HbWRKY27 was found to upregulate the expression of HbFPS1, while HbMADS4 negatively regulated HbSRPP [47,48]. HbTGA1 is a multi-functional transcription factor that represses the expression of HbCPT6 but activates HbHMGR2, HbCPT8, and HbSRPP2, respectively [49]. In the present study, we identified different regulatory patterns for two HbAP2/ERF members: HbAP2/ERF46 repressed HbMVD but activated HbHMGR, HbFPS1, and HbSRPP, while HbAP2/ERF25 repressed HbMVD, HbCPT, and HbSRPP. These findings underscore the crucial role of HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 in NR biosynthesis and suggest they might establish a complex regulatory network with key TFs for NR regulation. Studying the transgenics of HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 may provide further insights into the role of HbAP2/ERF in regulating NR biosynthesis in rubber trees. Protein–protein interactions are crucial for the transcriptional regulation of genes. In the rubber tree, the interaction with HbWRKY14 and HbVQ4/5 could relieve the inhibition of HbSRPP transcription [30]. Protein–protein interaction network analysis identified five putative interactors for HbAP2/ERF25 and two for HbAP2/ERF46, which provide valuable entry points for future mechanistic investigations into their precise regulatory roles in NR biosynthesis and stress responses.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we established a comprehensive genomic and functional framework for the AP2/ERF family in Hevea brasiliensis CATAS8-79, identifying 174 HbAP2/ERF genes (classified into 18 subclades, including one rubber-tree-specific RPV subclade) expanded mainly via 100 segmental and seven tandem repeats. Moreover, HbAP2/ERF25 and HbAP2/ERF46 are unique regulatory modules governing NR biosynthesis: HbAP2/ERF25 represses key NR pathway genes to maintain metabolic homeostasis, while HbAP2/ERF46 exerts dual-mode regulation to optimize NR metabolic flux—an adaptive mechanism unreported in woody plant AP2/ERF-mediated secondary metabolism. Beyond advancing understanding of AP2/ERF evolution and NR regulation, these two core regulators serve as actionable molecular targets for rubber tree precision breeding and metabolic engineering to enhance NR yield, laying the groundwork for future investigations into upstream signaling pathways modulating their activity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122881/s1, Figure S1: Ten conserved motifs in HbAP2/ERFs; Figure S2: Phylogenetic tree (A), conserved motif (B), and gene structure (C) analysis of HbAP2/ERFs in the rubber tree; Figure S3: Statistics of cis-regulatory elements of HbAP2/ERFs; Table S1: Primers used in this study; Table S2: Identification of AP2/ERFs in rubber tree genome; Table S3: Subfamily designation and sequence characteristics of the identified AP2/ERFs; Table S4: Ka/Ks analysis of segmental and tandem gene duplications of HbAP2/ERFs; Table S5: Cis-Regulatory element analysis of HbAP2/ERF promoters; Table S6: Interactions of HbAP2/ERFs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.D. and Y.S.; methodology, X.D. (Xiaoyu Du); software, X.D. (Xiaoyu Du) and W.C.; validation, S.Y., S.W. and M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, X.D. (Xiaomin Deng); resources, J.C.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.D. (Xiaoyu Du) and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. and J.C.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, H.Y. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (ZDYF2022XDNY252, ZDYF2022XDNY251), the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (325CXTD621), the Project of National Key Laboratory for Tropical Crop Breeding (NKLTCBCXTD20), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31800578), the National Key Research and Development Program (2023YFA0914800), and the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-33-YZ1).

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptome data presented in this study are openly available in the National Genomics Data Center under the BioProject accession number PRJCA004986.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Outstanding Talent Team Program of Hainan Province.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TF | Transcription factor |

| AP2/ERF | APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element-binding factor |

| DREB | Dehydration-responsive element binding |

| CBF | C-repeating binding factor |

| NR | Natural rubber |

| ABRE | ABA Responsive Element |

| CDS | Coding sequences |

| LTR | Low-temperature response |

| FPKM | Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads |

| LUC | Luciferase |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase |

| MVK | Mevalonate kinase |

| MVD | Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase |

| GPS | Geranyl pyrophosphate synthase |

| FPS | Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase |

| CPT | Cis-prenyltransferase |

| SRPP | Small rubber particle protein |

References

- Feng, K.; Hou, X.L.; Xing, G.M.; Liu, J.X.; Duan, A.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Li, M.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Xiong, A.S. Advances in AP2/ERF Super-Family Transcription Factors in Plant. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Shi, N.; Du, X.; Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, K.; Lin, Z.; Ma, D.; Li, Q.; et al. Bioinformatics Analysis and Expression Profiling Under Abiotic Stress of the DREB Gene Family in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Lan, Y.; Lin, M.H.; Zhou, H.K.; Ying, S.; Chen, M. Genome-Wide Identification and Transcriptional Analysis of AP2/ERF Gene Family in Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Suzuki, K.; Fujimura, T.; Shinshi, H. Genome-Wide Analysis of the ERF Gene Family in Arabidopsis and Rice. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Wang, S.P.; Zhao, X.; Dong, S.J.; Chen, J.H.; Sun, Y.Q.; Sun, Q.W.; Liu, Q.G. Genome-Wide Identification and Comprehensive Analysis of the AP2/ERF Gene Family in Prunus sibirica under Low-Temperature Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Geng, Z.W.; Zhang, C.P.; Wang, K.T.; Jiang, X.Q. Whole-Genome Characterization of Rosa chinensis AP2/ERF Transcription Factors and Analysis of Negative Regulator RcDREB2B in Arabidopsis. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Cai, B.; Peng, R.H.; Zhu, B.; Jin, X.F.; Xue, Y.; Gao, F.; Fu, X.Y.; Tian, Y.S.; Zhao, W.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of the AP2/ERF Gene Family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Argout, X.; Gébelin, V.; Summo, M.; Dufayard, J.; Leclercq, J.; Kuswanhadi; Piyatrakul, P.; Pirrello, J.; Rio, M.; et al. Identification of the Hevea brasiliensis AP2/ERF Superfamily by RNA Sequencing. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofuku, K.D.; Den Boer, B.G.; Van Montagu, M.; Okamuro, J.K. Control of Arabidopsis Flower and Seed Development by the Homeotic Gene APETALA2 (AP2). Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virág, E.; Tóth, B.B.; Kutasy, B.; Nagy, Á.; Pákozdi, K.; Pallos, J.P.; Kardos, G.; Hegedűs, G. Promoter Motif Profiling and Binding Site Distribution Analysis of Transcription Factors Predict Auto- and Cross-Regulatory Mechanisms in Arabidopsis Flowering Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virág, E.; Nagy, Á.; Tóth, B.B.; Kutasy, B.; Pallos, J.P.; Szigeti, Z.M.; Máthé, C.; Kardos, G.; Hegedűs, G. Master Regulatory Transcription Factors in β-Aminobutyric Acid-Induced Resistance (BABA-IR): A Perspective on Phytohormone Biosynthesis and Signaling in Arabidopsis Thaliana and Hordeum Vulgare. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizek, B.A. AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6 Regulate Auxin-Mediated Flower Development in Arabidopsis. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirota, A.; Kato, T.; Fukaki, H.; Aida, M.; Tasaka, M. The Auxin-Regulated AP2/EREBP Gene PUCHI Is Required for Morphogenesis in the Early Lateral Root Primordium of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2156–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitomi, Y.; Ito, H.; Hobo, T.; Aya, K.; Kitano, H.; Inukai, Y. The Auxin Responsive AP2/ERF Transcription Factor CROWN ROOTLESS5 (CRL5) Is Involved in Crown Root Initiation in Rice through the Induction of OsRR1, a type-A Response Regulator of Cytokinin Signaling. Plant J. 2011, 67, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Abe, H.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Two Transcription Factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA Binding Domain Separate Two Cellular Signal Transduction Pathways in Drought- and Low-Temperature-Responsive Gene Expression, Respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, S.J.; Zarka, D.G.; Stockinger, E.J.; Salazar, M.P.; Houghton, J.M.; Thomashow, M.F. Low Temperature Regulation of the Arabidopsis CBF Family of AP2 Transcriptional Activators as an Early Step in Cold-induced COR Gene Expression. Plant J. 1998, 16, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, C.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.H.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, W. Overexpression of the Jatropha curcas JcERF1 Gene Coding an AP2/ERF-Type Transcription Factor Increases Tolerance to Salt in Transgenic Tobacco. Biochemistry 2014, 79, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Cheng, Q.; Li, W.; Fan, S.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Z.; Kong, F.; Zhang, D.; et al. Overexpression of GmERF5, a New Member of the Soybean EAR Motif-Containing ERF Transcription Factor, Enhances Resistance to Phytophthora sojae in Soybean. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2635–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Chang, X.; Qi, D.Y.; Dong, L.D.; Wang, G.J.; Fan, S.J.; Jiang, L.Y.; Cheng, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, D.; et al. A Novel Soybean ERF Transcription Factor, GmERF113, Increases Resistance to Phytophthora sojae Infection in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.L.; Yan, Y.; Bai, Z.Q. The SmERF1b-like Regulates Tanshinone Biosynthesis in Salvia Miltiorrhiza Hairy Root. AoB PLANTS 2024, 16, plad086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.C.; Liu, L.; Li, X.H.; Wei, G.; Cai, Y.P.; Sun, X.; Fan, H.H. DoAP2/ERF89 Activated the Terpene Synthase Gene DoPAES in Dendrobium Officinale and Participated in the Synthesis of β-Patchoulene. Peer J. 2024, 12, e16760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.Y.; Kang, G.J.; Yan, D.; Qin, H.D.; Yang, L.F.; Zeng, R.Z. Downregulation of HbFPS1 Affects Rubber Biosynthesis of Hevea brasiliensis Suffering from Tapping Panel Dryness. Plant J. 2023, 113, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wu, S.H.; Chao, J.Q.; Yang, S.G.; Bao, J.; Tian, W.M. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of MYC Transcription Factor Family Genes in Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). Forests 2022, 13, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.T.; Liang, C.L.; Liu, X.; Tan, Y.C.; Lu, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Luo, H.L.; He, C.Z.; Cao, J.; Tang, C.R.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Candidate Genes Responsible for Inorganic Phosphorus and Sucrose Content in Rubber Tree Latex. Trop. Plants 2023, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Zhang, S.X.; Chao, J.Q.; Deng, X.M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Shi, M.; Tian, W.M. Transcriptome Analysis of the Signalling Networks in Coronatine-Induced Secondary Laticifer Differentiation from Vascular Cambia in Rubber Trees. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, J.; Wu, S.; Shi, M.; Xu, X.; Gao, Q.; Du, H.; Gao, B.; Guo, D.; Yang, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. Genomic insight into domestication of rubber tree. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.M.; Chen, Y.R.; Cai, G.J.; Cai, R.L.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization by One Table (tvBOT): A Web Application for Visualizing, Modifying and Annotating Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.W.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.H.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.L.; Feng, J.T.; Chen, H.; He, Y.H.; et al. TBtools-II: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-Based Genome Alignment and Genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-Genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie Enables Improved Reconstruction of a Transcriptome from RNA-Seq Reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherf, B.A.; Navarro, S.L.; Hannah, R.R.; Wood, K.V. Dual-LuciferaseTM Reporter Assay: An Advanced Co-Reporter Technology Integrating Firefly and Renilla Luciferase Assays. Promega Notes 1996, 57, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.H.; Qu, L.; Zeng, L.W.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.L.; Peng, S.Q.; Guo, D. Genome-Wide Identification of HbVQ Proteins and Their Interaction with HbWRKY14 to Regulate the Expression of HbSRPP in Hevea brasiliensis. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamuro, J.K.; Caster, B.; Villarroel, R.; Van Montagu, M.; Jofuku, K.D. The AP2 Domain of APETALA2 Defines a Large New Family of DNA Binding Proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 7076–7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drews, G.N.; Bowman, J.L.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Negative Regulation of the Arabidopsis Homeotic Gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 Product. Cell 1991, 65, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertran Garcia De Olalla, E.; Cerise, M.; Rodríguez-Maroto, G.; Casanova-Ferrer, P.; Vayssières, A.; Severing, E.; López Sampere, Y.; Wang, K.; Schäfer, S.; Formosa-Jordan, P.; et al. Coordination of Shoot Apical Meristem Shape and Identity by APETALA2 during Floral Transition in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Ohta, M.; Usui, A.; Shinshi, H.; Ohme-Takagi, M. Arabidopsis Ethylene-Responsive Element Binding Factors Act as Transcriptional Activators or Repressors of GCC Box–Mediated Gene Expression. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Chen, J.M.; Yao, Q.H.; Xiong, F.; Sun, C.C.; Zhou, X.R.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, A. Discovery and Expression Profile Analysis of AP2/ERF Family Genes from Triticum aestivum. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.J.; Wei, Y.F.; Xu, R.B.; Lin, S.; Luan, H.Y.; Lv, C.; Zhang, X.Z.; Song, X.Y.; Xu, R.G. Genome-Wide Analysis of APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) Gene Family in Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Deng, D.X.; Yao, Q.H.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, F.; Chen, J.M.; Xiong, A. Discovery, Phylogeny and Expression Patterns of AP2-like Genes in Maize. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 62, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Guan, S.; Li, L.C.; Li, A.; Guo, J.; Mao, L.; Ma, Y. Phylogeny, Gene Structures, and Expression Patterns of the ERF Gene Family in Soybean (Glycine max L.). J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 4095–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Yao, Q.H.; Xiong, A.; Zhang, J. Isolation, Phylogeny and Expression Patterns of AP2-Like Genes in Apple (Malus × domestica Borkh). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 29, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.M.; Li, Y.; Hou, X.L. Genome-Wide Analysis of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Superfamily in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.L.; Huang, S.Y.; Chen, X.Z.; Zai, W.S.; Xiong, Z.L. Re-identification of AP2/ERF Transcription Factors in Search for Disease Resistance-related Genes in Tomato Plant. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2025, 40, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammou, R.A.; Caid, M.B.E.; Harrouni, C.; Daoud, S. Germination Enhancement, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, and Metabolite Changes in Late Argania Spinosa Kernels under Salinity. J. Arid Environ. 2023, 219, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Jiang, C.H.; Zhang, X.T.; Yan, H.M.; Yin, Z.G.; Sun, X.M.; Gao, F.H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; Han, S.C.; et al. Upland rice genomic signatures of adaptation to drought resistance and navigation to molecular design breeding. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 22, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Zhao, X.B.; Bürger, M.; Wang, Y.R.; Chory, J. Two Interacting Ethylene Response Factors Regulate Heat Stress Response. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Wei, L.R.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.H.; Chen, X.T.; Peng, S.Q. HbMADS4, a MADS-Box Transcription Factor from Hevea brasiliensis, Negatively Regulates HbSRPP. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Li, H.L.; Guo, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.H.; Yin, L.Y.; Peng, S.Q. HbWRKY27, a Group IIe WRKY Transcription Factor, Positively Regulates HbFPS1 Expression in Hevea brasiliensis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Li, H.L.; Zhu, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, S.Q. HbTGA1, a TGA Transcription Factor From Hevea brasiliensis, Regulates the Expression of Multiple Natural Rubber Biosynthesis Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 909098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).