Abstract

Rhodotus palmatus is commercially marketed as ‘fruity-scented mushroom’, a novel cultivar first brought into commercial cultivation in China at the end of 2023. It is characterized by a distinct pinkish pigmentation, a pileus with a distinct reticulated surface pattern, and an intense fruity aroma. To date, only a few natural strains have been documented in China, and scientific research on this species remains scarce. This study successfully bred a new variety of Rhodotus palmatus and established corresponding efficient techniques for its industrial-scale cultivation. As a result, strain ZJGWG001, known for its short growth cycle (23 d), high yield potential (177.43 ± 10.08 g·bag−1) and biological efficiency (59.1%), and distinctive, stable phenotypic traits, is well suited for industrial cultivation. This cultivar is the first newly registered Rhodotus palmatus variety in China to receive provincial-level certification and has been officially designated as ‘Zhongjunguoweigu No. 1’. It represents an important discovery in the collection and exploration of wild fungal germplasm resources in recent years.

1. Introduction

Rhodotus palmatus (Bull.) Maire is a rare and distinctive edible mushroom, characterized by its rich nutritional content and potential medicinal properties [1]. It is classified within the phylum Basidiomycota, class Agaricomycetes, order Agaricales, family Physalacriaceae, and genus Rhodotus [2].

Multiple reports from around the world indicate that this species is relatively rare in the wild, particularly in Asia. It has been classified as a threatened species in numerous countries across Europe, North America, and other regions [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. It is characterized by an orange-red to pink pileus exhibiting a reticulate pattern, orange droplets on the stipe, and a pronounced fruit-like fragrance throughout its growth cycle [11]. The fruit body of this mushroom is rich in protein, 18 amino acids, calcium, iron, zinc, and vitamins. Natural products isolated from R. palmatus have demonstrated potent anti-hepatitis C virus activity, as well as mild antimycotic and cytotoxic effects, along with protective effects on immune organs [12,13,14,15].

R. palmatus was first discovered by He in the cities of Jiaohe, Shulan, and Dunhua in Jilin Province, China, in 1992 [11]. Tolgor and Fan achieved the first successful domestication and cultivation of the wild strain in China [16]. Currently, R. palmatus is cultivated only on a small scale in Henan, China. As a fruity edible mushroom, its crisp, smooth texture, accompanied by a sweet aftertaste, has elicited positive consumer responses in China’s first-tier cities from 2023 to the present [17].

As a novel edible fungus characterized by a short growth cycle, distinctive color, and unique aroma, it exhibits considerable developmental potential and significant value in enriching rare edible fungal germplasm resources. In this study, we report the first successful selection and breeding of this cultivar in accordance with the Chinese national standard ‘Technical inspection for mushroom selection and breeding’ and developed a set of efficient factory-based cultivation techniques. It encompassed strain collection, strain isolation and purification, molecular phylogeny identification, primary and secondary trial cultivation, physiological performance determination, intermediate cultivation test, demonstration of commercial cultivation, and determination of nutrient contents in the fruiting body. This achievement underscores the importance of enhancing the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources and highlights the critical role of the edible fungus industry in advancing high-quality and sustainable agricultural development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains Collection

The fruiting bodies of Rhodotus palmatus were collected from trunks within mixed coniferous and broad-leaved forest in Donggang Town, Fusong County, Baishan City, Jilin Province (42.081° N, 127.416° E, altitude: 748.9 m), on 8 September 2022 (Figure 1). After that, we performed strain isolation of this mushroom on PDA medium. All media were prepared manually.

Figure 1.

The habitat of R. palmatus.

2.2. Tissue Isolation and Purification

A PDA enrichment medium was employed for the isolation and cultivation of pure strains. The medium consisted of 200 g of potato (obtained through boiling extraction), 20 g of glucose, 15 g of agar, 1.5 g of yeast extract, 1 g of potassium dihydrogen phosphate, 0.5 g of magnesium sulfate, and 0.01 g of thiamine, with all components dissolved in 1 L of distilled water. All reagents are procured from Biosharp, a brand of Beijing LABGIC Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) (https://www.labgic.com/, (accessed on 5 November 2025)).

Firstly, the dirt from the fruiting body surface was briefly cleaned, and then a piece of mushroom tissue was cut from the interior of the junction of the fruiting body pileus and stipe, about 5 mm in diameter, and placed in the center of the PDA enrichment medium, using a sterile scalpel. The inoculated PDA plates were maintained in the dark at 25 °C for approximately 15 days. After two to three rounds of purification, the best growing isolates were selected as the experimental strain named ZJGWG001. The strain has been deposited in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) and assigned the accession number 41297.

2.3. Molecular Phylogeny Identification

DNA was extracted from the dried specimens using the MolPure Fungal DNA Kit (Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The nuclear ribosomal ITS region was amplified using the primer pair ITS5 and ITS4 [18]. The PCR procedure for ITS followed the protocol described by Zhao and Wu [19].

Sequences were aligned in MAFFT 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/, (accessed on 10 September 2024)) and manually adjusted in BioEdit [20]. The datamatrix was analyzed using a maximum likelihood (ML) approach with RAxML-HPC2 version 8.2.12 through the CIPRES Science Gateway (www.phylo.org, (accessed on 10 September 2024)) [21]. The sequence of Physalacria auricularioides was used as the outgroup. Branch support for ML analysis was determined by 1000 bootstrap replicates and evaluated under the gamma model. Branches were regarded as strongly supported when they exhibited a maximum likelihood bootstrap value (BS) exceeding 70%.

2.4. Primary and Secondary Screening of Trial Cultivation

The breeding tests were conducted in accordance with the Chinese national standard GB/T 21125-2007, ‘Technical Inspection for Mushroom Selection and Breeding’ [22]. A total of 750 g of homogenously mixed substrate—consisting of sawdust (36%), corn cob (35%), bran (8%), cottonseed hulls (5%), wheat (7%), soybean meal (8%), gypsum (1%), with a moisture content of 60%—was packed into each polypropylene plastic bag (18 × 35 × 0.005 cm). The moisture content is measured using the MB120ZH moisture tester from Ohaus Instruments Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China). The filled bags were sterilized at 121 °C under a pressure of 0.15 MPa for 120 min. Two sets of cultivation trials were carried out using 30 and 60 bags, respectively. A seed culture was prepared in a 1500 mL conical flask containing a liquid inoculum composed of 5 g corn flour, 20 g glucose, 6 g yeast powder, 2 g peptone, 3 g disodium hydrogen phosphate, and 2 g magnesium sulfate dissolved in 1 L of water. Ten mycelial agar plugs (5 mm in diameter), obtained from the plating medium described in Section 2.2, were inoculated into the liquid medium. After approximately 7 days of cultivation at 24 °C and 160 rpm, when the mycelium had colonized approximately 80% of the liquid volume, the culture was aseptically transferred to a fermenter containing a nutrient solution consisting of 600 g soybeans, 1.6 kg glucose, 240 g yeast extract, 100 g peptone, 100 g monopotassium phosphate, 50 g magnesium sulfate, and 1 g thiamine dissolved in 80 L of water. Aerobic culture was conducted at 22 °C and 0.05 MPa. The 100 L fermenter was purchased from Wenzhou Sanxiong Fluid Equipment Co., Ltd., Wenzhou, China. After an additional cultivation period of approximately 6 days, the mycelial biomass grown in fermented medium could be inoculated into sterilized bags at a volume of 25 mL per bag. The inoculated bags were then incubated in darkness at a constant temperature of 22 °C for 15 days.

Once the mycelium had colonized 60% of the substrate, the bags were transferred to the intelligent mushroom growing room, where primordia induction was carried out under controlled conditions: 20 °C, 80% relative humidity, 1100 ppm carbon dioxide, and a light intensity of 400 lx for 2 days. After the appearance of rudiments, the bags were opened and maintained under fruiting conditions–95% relative humidity, 600–800 ppm carbon dioxide, and scattered light–for an additional 8 days until harvest. The agronomic traits, including cap and stipe morphology, growth cycle duration, yield, and biological efficiency, were recorded.

In the formula, Z refers to biological efficiency; X indicates the yield weight per bag in grams; Y represents the dry substrate weight per bag, also expressed in grams.

2.5. Physiological Performance Determination

- Antagonism Test

The tests were performed according to the Chinese industry standard NY/T 1845-2010 ‘Identification of Distinctness for Edible Mushroom Cultivar by Antagonism’ [23].

The main commercial cultivation variety of R. palmutus in Henan Province, designated as GGR-001, was used as the control. Mycelium pieces with a diameter of 5 mm were excised from the 18-day-old pure culture of ZJGWG001 and GGR-001, and placed 15 mm away from the center point of the PDA enrichment medium, cultured at 20 °C. The hyphal morphology at the junction of the colonies of the two strains was observed.

- Temperature Gradient Test

Mycelium pieces with a diameter of 5 mm, derived from ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 at the same age, were excised and placed in the center of PDA enrichment media. The samples were then incubated in the dark at temperatures ranging from 5 to 30 °C for a duration of 20 days, with experimental setups established at intervals of 5 °C.

- Antifungal Interaction Assay

Mycelium pieces with a diameter of 5 mm were aseptically excised from actively growing margins of ZJGWG001, GGR-001, Trichoderma harzianum, and Penicillium fellutanum cultures, and inoculated onto PDA enrichment medium in parallel. Fungal colony growth was monitored over time in darkness at a constant temperature of 25 °C for 15 days. All experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.6. Intermediate Cultivation Test

For ZJGWG001, a total of 1500 bags were cultivated per group, with three replicate groups established, according to the procedure described in Section 2.4. A random sample of 100 bags was selected from each group to determine yield, and agronomic traits of the fruiting bodies were recorded.

2.7. Demonstration of Commercial Cultivation

From August 2023 to August 2024, three demonstration cultivation trials were conducted in Jinning District (24.57° N, 102.58° E), Kunming City, Yunnan Province, and two were conducted in Luliang County (24.97° N, 103.62° E), Qujing City, Yunnan Province, and Chenghai (23.47° N, 116.76° E) District, Shantou City, Guangdong Province. The strains ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 were cultivated using the industrial cultivation method described in Section 2.4. Each trial involved 10,000 bags and was divided into three replicate groups, with the ratio of ZJGWG001 to GGR-001 set at 9:1. Metrics such as yield, number of buds per bag, and agronomic traits of single fruit were counted.

2.8. Determination of Nutrient Contents in Fruiting Body

More than 300 g of dried fruiting body samples collected from each of the two strains were submitted to Yunnan Sanzheng Technical Testing Co., Ltd. (Kunming, China) for compositional analysis, including assessments of proteins, amino acids, total saccharides, polysaccharides, trace elements, and vitamins, along with other constituents [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

2.9. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSSAU (https://spssau.com, (accessed on 8 July 2025)). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (±s). To compare differences across multiple groups, one-way ANOVA was applied, followed by the least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

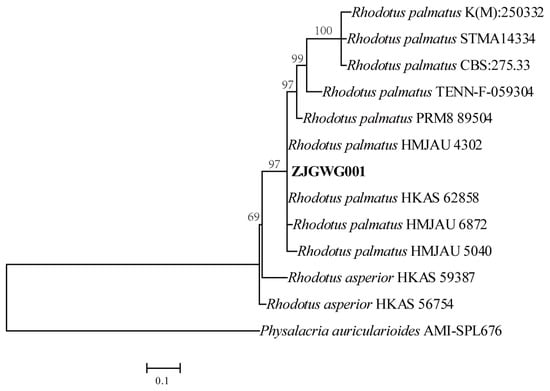

All of the newly generated sequences were deposited in NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, (accessed on 10 September 2024)) (Table 1). The phylogenetic tree based on ITS sequences indicates that ZJGWG001, along with the other known R. palmatus strains, is clustered in the large clade (Figure 2).

Table 1.

List of species, specimens, and GenBank accession numbers of sequences used in this study.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the phylogeny of ZJGWG001 and related species in Rhodotus, based on ITS sequences.

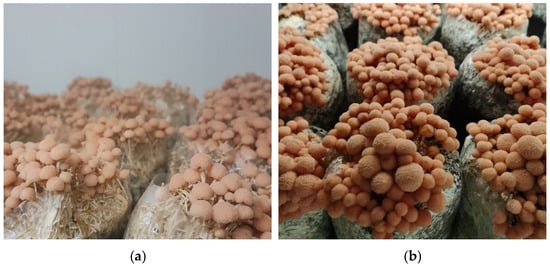

3.2. Results of Primary and Secondary Screening

ZJGWG001 is suitable for large-scale cultivation due to its good consistency, short growth cycle, and high stability, as indicated in Figure 3 and Table 2. Fruit bodies can be harvested 25 days after liquid inoculum injection, with a pinkish stipe and an orange-red pileus. Its yield reached 131.21 ± 8.5 g per bag in the primary test and 136.34 ± 7.88 in the secondary. The pileus was of small size, with a diameter of 2.11 ± 0.36 cm in the primary test and 2.30 ± 0.18 in the secondary. The length of the stipe was 2.80 ± 0.25 cm in the primary test and 3.07 ± 0.19 in the secondary. Subsequently, physiological performance tests were conducted on ZJGWG001 and GGR-001.

Figure 3.

Photos of fruiting observed at 23 days. (a) primary screening; (b) secondary screening.

Table 2.

Agronomic trait results of ZJGWG001 from primary and secondary screening.

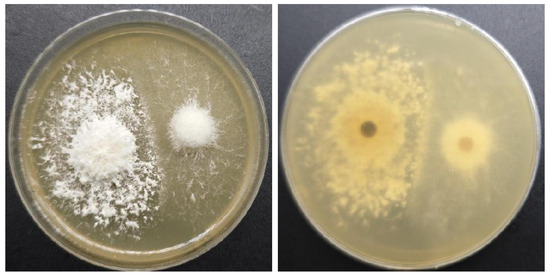

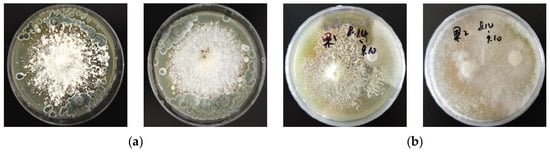

3.3. Results of Antagonistic Reaction

The results of the antagonism tests reveal an isolated antagonistic interaction between ZJGWG001 and GGR-001, as depicted in Figure 4. Additionally, distinct differences were observed in the mycelial morphology.

Figure 4.

Antagonistic reaction between ZJGWG001 (left) and GGR-001 (right).

The antagonism assay results show a clear isolated antagonistic response between ZJGWG001 and GGR-001, as illustrated in Figure 4. Moreover, noticeable variations were detected in the mycelial morphological characteristics.

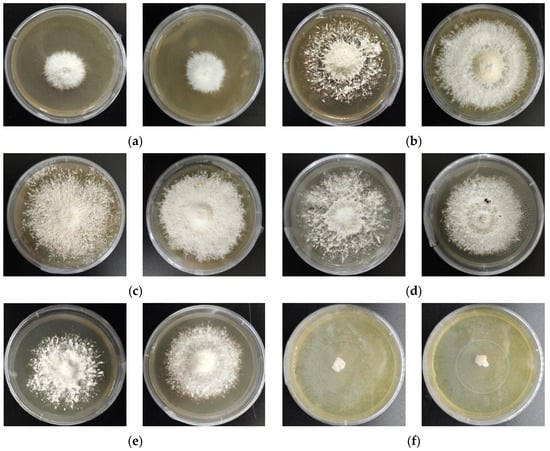

3.4. Results of Temperature Gradient Test

As depicted in Figure 5 and Table 3, both strains can grow within the temperature range of 5 to 30 °C. Moreover, at 15 °C and 20 °C, ZJGWG001 shows better growth performance than GGR-001.

Figure 5.

Temperature Gradient Test between ZJGWG001 (left) and GGR-001 (right) at 20 days. (a) 5 °C; (b) 10 °C; (c) 15 °C; (d) 20 °C; (e) 25 °C; (f) 30 °C.

Table 3.

Colony diameters of ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 measured at 20 days of growth.

3.5. Results of Antifungal Interaction Assay

As depicted in Figure 6, during the antifungal evaluation against Trichoderma harzianum and Penicillium fellutanum, ZJGWG001 exhibits a significant antagonistic effect against both T. harzianum and P. fellutanum, whereas the mycelium of the GGR-001 colony was overgrown by Trichoderma, indicating the absence of inhibitory activity against this fungal species.

Figure 6.

Antifungal interaction assay. (a) ZJGWG001 (left) and GGR-001 (right) with P. fellutanum; (b) ZJGWG001 (left) and GGR-001 (right) with T. harzianum.

3.6. Results of Intermediate Test

In the intermediate test, the size and yield of the fruiting bodies have significantly increased compared to the secondary screening, as indicated in Figure 7 and Table 4. ZJGWG001 has a stipe length of 5.97 ± 0.25 cm, compared to 3.07 ± 0.19 before. The individual fruiting bodies were relatively small, with stipe diameters up to 3.42 ± 0.14 mm. The pileus diameter was 2.63 ± 0.15 cm, compared with 2.30 ± 0.18 cm in the secondary screening. Accordingly, the yield of ZJGWG001 increased to 156.45 ± 7.10 compared to 136.34 ± 7.88 before. The intermediate test has shown that ZJGWG001 has a short growing cycle, high yield, and high stability. Moreover, management techniques can be further optimized to increase yield even more.

Figure 7.

Photos of fruiting.

Table 4.

Result of intermediate test.

3.7. Results of Demonstration Cultivation

Compared to GGR-001, as shown in Table 5, ZJGWG001 exhibited significant differences in stipe diameter and bud number. The stipe diameter of ZJGWG001 was 2.64 ± 0.57 compared to GGR-001’s 4.75 ± 1.18. While the stipe length, pileus diameter, and yield of the two strains were so close, the bud number of ZJGWG001 was 10 more per bag than GGR-001.

Table 5.

Result of Demonstration Cultivation.

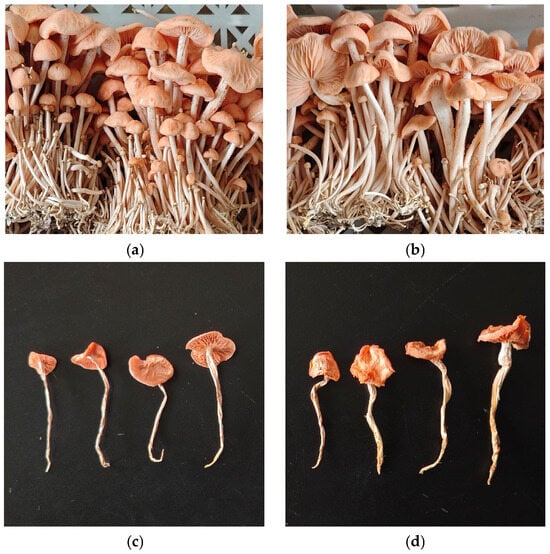

The results of these trials for ZJGWG001 satisfy the criteria for new cultivar identification, as shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. On 26 May 2025, ZJGWG001 passed the identification of non-major crop varieties in Yunnan Province by Yunnan Seed Management Station, which was the first new variety of R. palmatus to obtain the provincial-level new variety recognition in China.

Figure 8.

Industrial cultivation of ZJGWG001. (a) Fruiting for 18 days; (b) fruiting for 22 days.

Figure 9.

Dried and fresh fruiting bodies. (a) Fresh fruiting bodies of ZJGWG001; (b) fresh fruiting bodies of GGR-001; (c) dried fruiting bodies of ZJGWG001; (d) dried fruiting bodies of GGR-001.

3.8. Nutrient Contents of ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 Fruiting Bodies

The nutrient contents of ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 are shown in Table 6. The levels of 15 amino acids, total amino acids, protein, total sugar, iron, zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin C, and vitamin D2 in ZJGWG001 were all higher than those in GGR-001.

Table 6.

Nutrient contents of ZJGWG001 and GGR-001.

4. Discussion

During the breeding of new varieties, the fruiting bodies of strain ZJGWG001 exhibited a clustered arrangement, with caps that were orange to pink in color, hemispherical in shape, and featured a soft leathery surface marked by a network of raised ridges. The stipes were light pink, bearing liquid droplets on the surface, with colors ranging from honey yellow to orange-red. Both the mycelium and fruiting bodies emitted a distinct fruity aroma. Morphologically, ZJGWG001 differed significantly from common edible mushrooms in the Physalacriaceae, such as Flammulina velutipes and Armillaria mellea.

Primary and secondary screening trial cultivation confirmed that ZJGWG001 is amenable to artificial cultivation and displayed unique agronomic traits, particularly an exceptionally short growth period. Physiological performance tests indicated that ZJGWG001 and GGR-001 represent distinct varieties within R. palmatus. The optimal temperature range for mycelial growth was 15–25 °C, under which the strain demonstrated strong vitality and superior antifungal activity compared to the control. In the intermediate cultivation test, ZJGWG001 exhibited a short and consistent period from primordia formation to harvest. Subsequent demonstration-scale experiments encompassed five cultivation cycles conducted across three locations, with results indicating a growth period of 23 days, with an average of 62.25 ± 6.73 buds per bag, stipe length of 8.50 ± 1.39 cm, stipe diameter of 2.64 ± 0.57 mm, cap diameter of 3.83 ± 0.69 cm, yield of 177.43 ± 10.08 g per bag, and a biological efficiency of 59.1%.

In comparison, the fruiting body size and yield of F. velutipes variety Shangyan 1820 (stipe diameter (2.05 ± 0.12 mm), cap diameter (6.77 ± 0.34 cm), stipe length (11.50 ± 0.749 cm), number of primordia (506 ± 21.28 per bag), and biological efficiency (87.5%)) all exceeded those of ZJGWG001. This gap may be attributed to the lack of systematic optimization of the solid cultivation substrate formulation for R. palmatus. Notably, while Shangyan 1820 fruits at a low temperature of 5–8 °C with a longer fruiting cycle of 47 days, ZJGWG001 fruits at 20 °C and has a significantly shorter growth period of 23 days [36]. Drawing from the successful management practices of F. velutipes cultivation, further optimization may enhance primordia induction and increase yields of ZJGWG001. In addition, to align with market preferences, a period of targeted investigation is still required. Currently, we consider that industrial cultivation should focus on producing fruiting bodies with smaller caps and clearly defined surface patterns.

The nutrient content of ZJGWG001 was compared with that of F. velutipes and Hericium erinaceus cultivated at the same site in Jinning District, using an identical detection method. The protein content of ZJGWG001 was comparable to that of H. erinaceus (12.7 g/100 g) and F. velutipes (15.8 g/100 g). Crude fiber content was significantly lower than that of F. velutipes (54.4 g/100 g) and H. erinaceus (4.4 g/100 g). Crude fat content was also lower than both reference species, with values of 1.9 g/100 g in F. velutipes and 1.4 g/100 g in H. erinaceus. Thiamine (Vitamin B1) content in ZJGWG001 exceeded that of F. velutipes (0.044 mg/100 g) but was below that of H. erinaceus (0.165 mg/100 g). Riboflavin (Vitamin B2) content was higher than that of F. velutipes (0.212 mg/100 g), yet remained lower than that of H. erinaceus (0.318 mg/100 g). It can be observed that R. palmatus exhibits the characteristic profile of major edible fungi, namely, high protein and low fat content, and is rich in various nutrients essential for human health. According to the principles of compound nutrition, a balanced intake of nutrients can be achieved through the combined consumption of grains, vegetables, fungi, and animal-based foods [37].

China has a long history of cultivating edible fungi, with the earliest written records dating back to 100 BC. Throughout the development of edible fungus cultivation, China has played a pivotal role in advancing the global industry. Among the major cultivated species, the vast majority were first domesticated in China, with only a few exceptions—such as Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Hypsizygus marmoreus—which were initially cultivated outside the country [38]. Prior to the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the edible fungi industry developed slowly due to social unrest and other adverse factors. However, since 1950, China’s edible fungi production has experienced rapid growth, accompanied by a steady expansion in the variety of cultivated species. According to statistics from the China Edible Fungi Association, the total production of edible fungi in China reached 43.3417 million tons in 2023, accounting for more than 90% of global output (https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzAxMzAwMjM0MQ==&mid=2652710010&idx=1&sn=a62bf89909b572f06d056800bd64f930&chksm=819ca418e43f370d51ebf5fff36bca83c697c2d4747f4dea2b460d2f352c244b8797dc218184&scene=27, (accessed on 1 December 2025)).

The factory-based production model for edible fungi represents a key developmental direction for the industry. The rapid growth of the sector has accelerated this transition, yet shifting from traditional workshop-style cultivation to fully industrialized production remains a gradual and long-term process. Currently, only a limited number of species, such as F. velutipes and Pleurotus eryngii, have achieved large-scale and high-yield cultivation under controlled factory conditions in China. For other widely cultivated species like Lentinula edodes and Auricularia auricula, which are not well-suited to conventional industrial models for wood-decay fungi, Tan proposed an innovative approach: centralized production of mushroom bags by enterprises, coupled with decentralized fruiting management by farmers. This model significantly lowers technical entry barriers and effectively improves farmers’ income [38,39].

Our research team, based in Yunnan Province, has been systematically collecting rare and potentially valuable wild fungal strains throughout the country for decades. To date, R. palmatus has been documented only a few times, all within the Changbai Mountain region. Yunnan Province lies at the intersection of the Arctic-flora zone and the ancient tropical flora zone, serving as a habitat for plant species originating from frigid, temperate, and tropical regions. The province encompasses seven climate types, 18 soil types, and up to 288 soil varieties. Most areas receive an average annual precipitation exceeding 1000 mm, and the altitudinal gradient spans over 6000 m [40]. Owing to these characteristics, Yunnan is widely recognized as China’s ‘Kingdom of Wild Fungi’. Nearly 2800 species of macromycetes have been documented there, including approximately 900 edible species—accounting for 90% of China’s edible fungal diversity and 45% of the global total [41]. Its unique geographical position and favorable ecological conditions foster exceptional wild fungal diversity. However, recent reports have increasingly highlighted promising rare edible fungal species in temperate continental mountainous regions and tropical low-altitude areas [42]. These findings indicate that expanding exploration beyond Yunnan—particularly into regions with contrasting climatic and topographical profiles—may reveal additional fungal species with significant biological and economic potential.

R. palmatus is currently marketed in China under the commercial name ‘Guoweigu’, meaning ‘fruity-scented mushroom’. Although cultivation is confined to a small scale and limited to a single province, findings from our field investigations and analyses of media platform engagement indicate substantial public interest, suggesting that this mushroom possesses considerable developmental potential. As a distinctive and novel edible fungal species, research on its cultivation techniques, basic biology, pharmacological properties, and product development remains in the early stages, pointing to broad prospects for future advancement.

5. Conclusions

This research successfully cultivated a new type of edible fungus with great potential through natural selection. The main achievements include: A strain exhibiting robust mycelial growth was isolated and purified from a wild specimen collected from a natural habitat. Following primary and secondary screening, the cultivation potential of the strain was identified based on its favorable agronomic traits and growth characteristics. An antagonism assay was performed between strain ZJGWG001 and GGR-001, the only other known domestic variety, revealing a significant antagonistic interaction between the two strains. In the antifungal interaction assay, the resistance of ZJGWG001 was markedly higher than that of GGR-001. The results of intermediate trials and demonstration cultivation demonstrate that ZJGWG001 exhibits favorable traits, including a short growth cycle (23 d), a high number of buds (62.25 ± 6.73), a small stipe diameter (2.64 ± 0.57 mm), high phenotypic stability, and excellent trait consistency. Significant differences in agronomic characteristics are observed between the two strains, with ZJGWG001 showing overall superior performance compared to GGR-001. ZJGWG001 was officially recognized as the non-major crop variety ‘Zhongjunguoweigu No. 1’ by the Yunnan Provincial Seed Management Station on 26 May 2025. We have concluded that ZJGWG001 is considered suitable for industrialized cultivation based on its short growth cycle, high resistance and yield, and distinctive, stable phenotypic traits.

6. Patents

The strain ZJGWG001 of Rhodotus palmatus with its cultivation method has the patent number 2024 1 1512792.01. Authorization proclamation date: 11 March 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., S.L., R.H., and D.S.; resources, X.L., J.Z., and F.Z.; methodology, X.L., S.L., J.L., Q.L., and L.W.; bibliographic retrieval, X.L., Q.L., C.L., and L.W.; investigation, X.L., C.L., and L.W.; formal analysis, X.L., S.L., J.L., J.Z., and C.L.; validation, X.L., F.Z., and Q.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., S.L., F.Z., J.L., and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.H. and D.S.; supervision, R.H. and D.S.; project administration, R.H. and D.S.; funding acquisition, R.H. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Innovation Guidance and Cultivation Program for Technology-based Enterprises (202404BI090003), Special Project for Provincial-Municipal Integration in Yunnan Province (202402AN360003), and Science and Technology Talent and Platform Program (202205AD160042).

Data Availability Statement

For further information or inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Tolgor, B. Chinese Changbai Mountain Mushrooms; China Science Publishing: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.L.; Qin, J.; Guo, T.; Hao, Y.J. The phylogeny and evolution of the Physalacriaceae family. Abstract Collection of Papers from the 2016 Academic Annual Conference of the Chinese Mycological Society. 2016, pp. 181–182. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=8XsFQqBkIey2jFvGvQ0v4b5MD0yq_QDNeLNaeh-hwJoySLRbWmB0zsQUaeJwgv27XP2DuTYyX_lSNpq5vqVrA03tDH_oH99kz9P3NvilP4QWdgmrG29DVh0t_hB3OnRnnLiBGzSjnCTMg18EytYEc7b2lrTBiFFwPkAdVUXeGNg5vmzh9mxbSFzv820zy2eo&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Wang, B.; Zhang, M.J. A new record species of the genus Rhodotus. Microbiol. China 1992, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujakiewicz, A. Gloiodon strigosus (Swartz: Fr.) P. Karst. (Bondarzewiaceae) in Poland. Acta Mycol. 2007, 42, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volobuev, S.V.; Popov, E.S.; Bolshakov, S.Y.; Tsutsupa, T.A. Species of fungi recommended for inclusion in the 2nd edition of the Red Data Book of Oryol Region. Разнooбразие растительнoгo мира 2021, 3, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.K.; Park, Y.J.; Choi, S.K.; Lee, J.O.; Choi, J.H.; Sung, J.M. Some unrecorded higher fungi of the seoraksan and odaesan national parks. Mycobiology 2006, 34, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.P.; Hao, Y.J.; Cai, H.Q.; Tolgor, B.; Yang, Z.L. Morphological and molecular evidence for a new species of Rhodotus from tropical and subtropical Yunnan, China. Mycol. Prog. 2014, 13, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrici, A.; Legon, N. BMS Day Foray Reports. Mycologist 1999, 13, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, W.J.; Methven, A.S.; Monoson, H.L. Rhodotus palmatus (Basidiomycetes, Agaricales, Tricholomataceae) in Illinois. Mycotaxon 1997, 65, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. A new species and a new record of Tricholomataceae from China. Acta Mycol. Sin. 1992, 11, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.G. Studies on Conservation Biology of Endangered Macrofungi in Changbai Mountain Nature Reserve. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elkhateeb, W.A.; Daba, G.M. The wild non edible mushrooms, what should we know so far. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2022, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandargo, B.; Michehl, M.; Stadler, M.; Surup, F. Antifungal sesquiterpenoids, rhodocoranes, from submerged cultures of the wrinkled peach mushroom, Rhodotus palmatus. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 83, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandargo, B.; Michehl, M.; Praditya, D.; Steinmann, E.; Stadler, M.; Surup, F. Antiviral meroterpenoid rhodatin and sesquiterpenoids rhodocoranes A–E from the wrinkled peach mushroom, Rhodotus palmatus. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3286–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Cao, R.K.; Bao, H.Y. Effects of Rhodotus palmatus polysaccharide on immunodeficient mice induced by cyclophosphamide. Acta Edulis Fungi 2023, 30, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolgor, B.; Fan, Y.G. Study on domesticaion of Rhodotus palmatus. Edible Fungi China 2008, 27, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commercial cultivation of mushrooms (Rhodotus palmatus) has been achieved. Edible Med. Mushrooms 2024, 32, 210.

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.L.; Wu, Z.Q. Ceriporiopsis kunmingensis sp. nov. (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) evidenced by morphological characters and phylogenetic analysis. Mycol. Prog. 2017, 16, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user–friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.A.; Holder, M.T.; Vos, R.; Midford, P.E.; Liebowitz, T.; Chan, L.; Hoover, P.; Warnow, T. The CIPRES Portals. CIPRES. Available online: www.phylo.org/sub_sections/portal (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- GB/T 21125-2007; Technical Inspection for Mushroom Selecting and Breeding. National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2007.

- NY/T 1845-2010; Identification of Distinctness for Edible Mushroom Cultivar by Antagonism. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB5009.5-2016; Determination of Protein in Food of National Standard for Food Safety. China Food and Drug Administation: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.124-2016; Determination of Amino Acids in Food of National Standard for Food Safety. China Food and Drug Administation: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB/T 15672-2009; Determination of Total Saccharide in Edible Mushroom. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- SN/T 4260-2015; Determination of Crude Polysaccharides in Plant Source Foods for Export-Phehol-Sulfuric Acid Colorimetry. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB5009.14-2017; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Zinc in Food. People’s Republic of China National Health and Family Planning Commission, National Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2017.

- GB5009.90-2016; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Iron in Food. People’s Republic of China National Health and Family Planning Commission, National Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.92-2016; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Calcium in Food. People’s Republic of China National Health and Family Planning Commission, National Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.84-2016; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Vitamin B1 in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.85-2016; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Vitamin B2 in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China, National Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.86-2016; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Ascorbic Acid in Food. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- GB5009.296-2023; National Food Safety Standards, Determination of Vitamin D in Food. National Health Commission, State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Vu, D.; Groenewald, M.; de Vries, M.; Gehrmann, T.; Stielow, B.; Eberhardt, U.; Al-Hatmi, A.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Cardinali, G.; Houbraken, J.; et al. Large–scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 92, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.J.; Lu, H.; Xu, Z.; Song, C.Y.; Tan, Q.; Liu, J.Y.; Shang, X.D. A new variety of Flammulina velutipes, ‘Shangyan 1820’, was developed through single-spore hybridization. Mycosystema 2023, 42, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lu, S.J.; Sun, J.M.; Xu, Z.Q.; Qi, J.; Liu, P.; Huang, J.Z. Analysis and evaluation on nutritional components of 26 common edible fungi in market. Edible Fungi China 2021, 40, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q. The development history of edible fungus cultivation. Acta Edulis Fungi 2024, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.R.; Yu, H.L.; Jiang, N.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shang, X.D.; Song, C.Y.; Tan, Q. The current status and trends of the development of industrialized production of edible mushrooms in China. Edible Med. Mushrooms 2024, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.Y. Re search on Brand Promotion of Yunnan Wild Edible Fungus in A Company. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China, December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yunnan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau. List of Biological Species in Yunnan Province (2016 Edition); Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.J.; Zhang, C.X.; He, M.X.; Liang, Z.Q.; Deng, X.H.; Zeng, N.K. Buchwaldoboletus xylophilus and Phlebopus portentosus, two non–ectomycorrhizal boletes from tropical China. Phytotaxa 2021, 520, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).