Performance of Strip Intercropping of Genetically Modified Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Transgenic Maize and Soybean Events

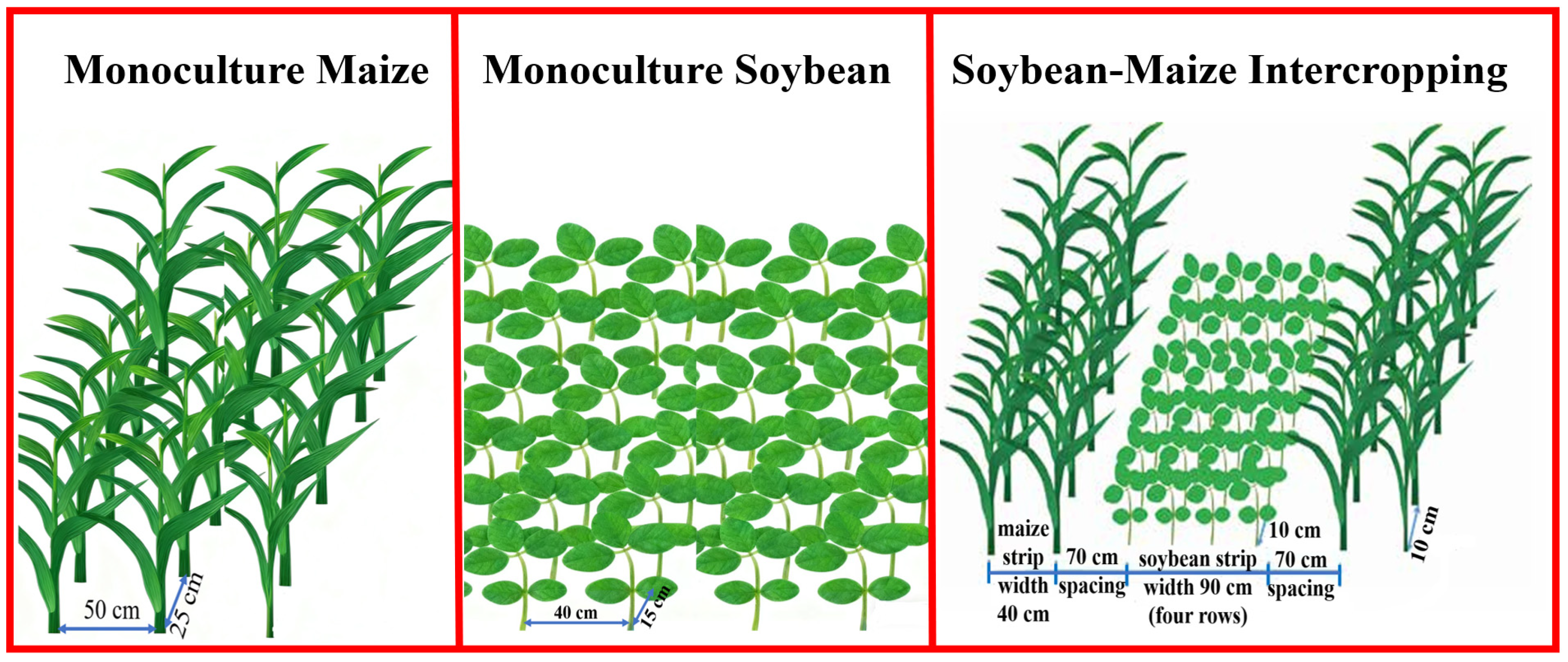

2.2. Experimental Design and Field Trial

2.3. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Control Efficacy of the Strip Intercropping of GM Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests

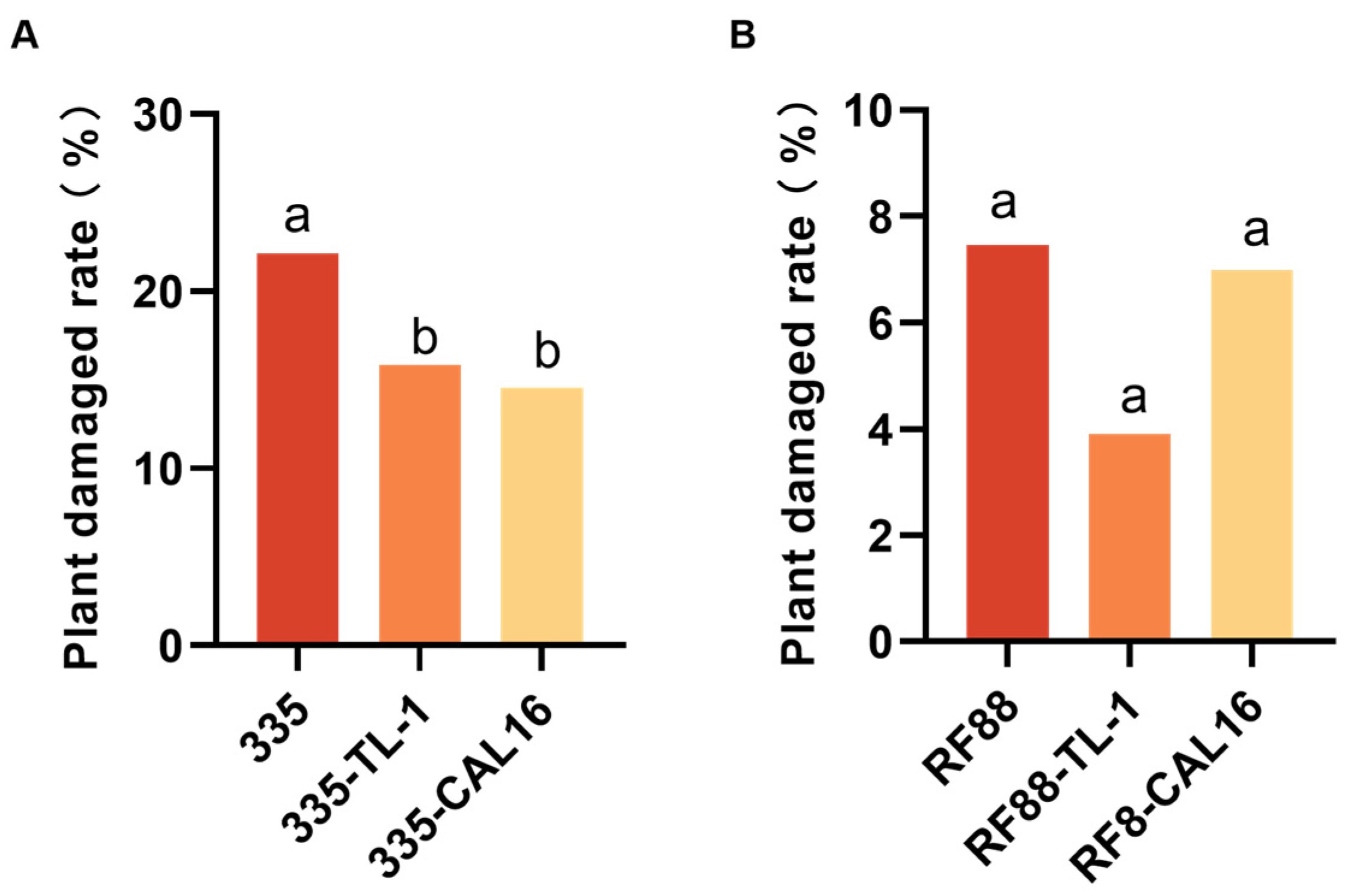

3.2. Control Efficacy of Strip Intercropping for H. armigera on Maize Plant

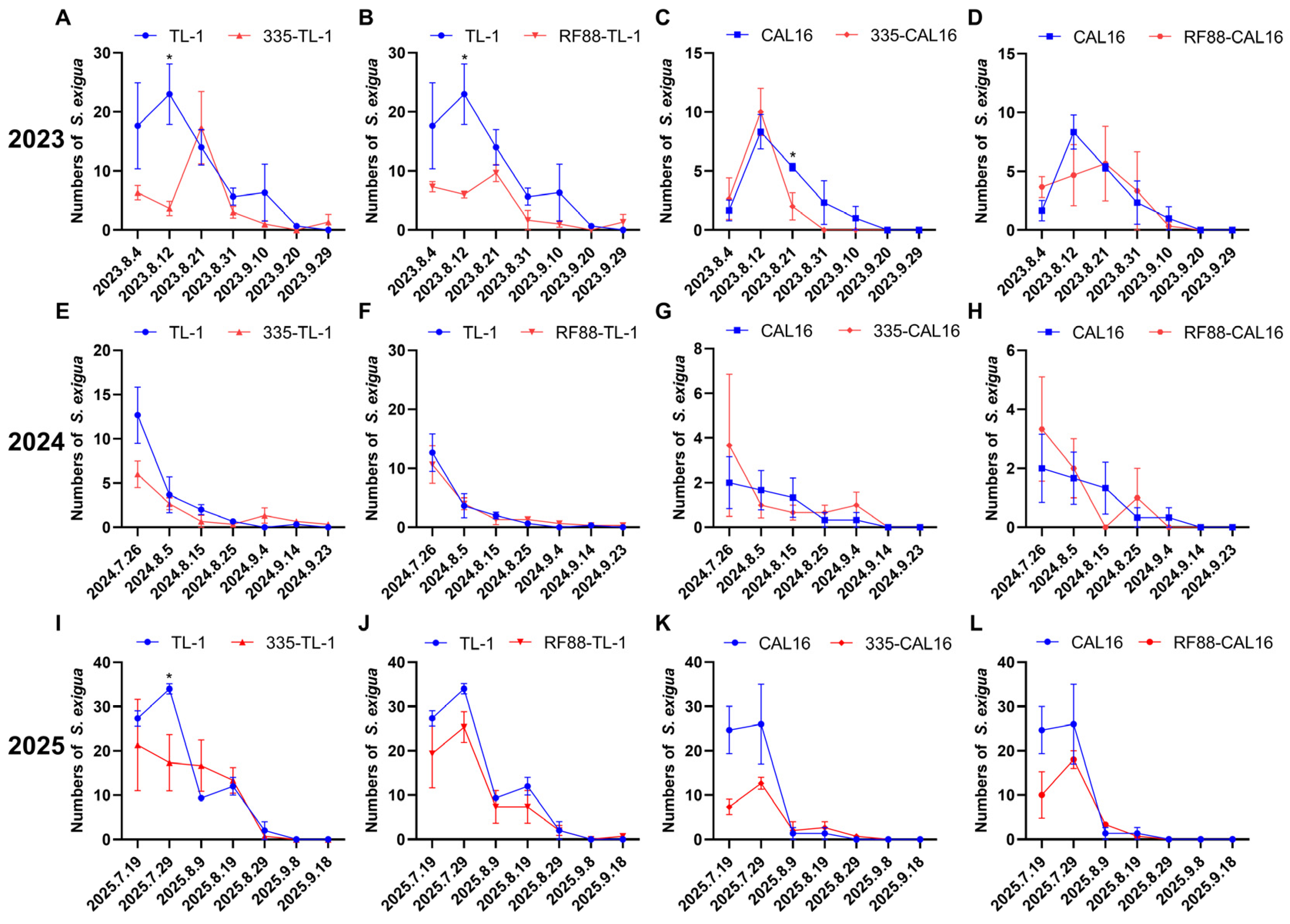

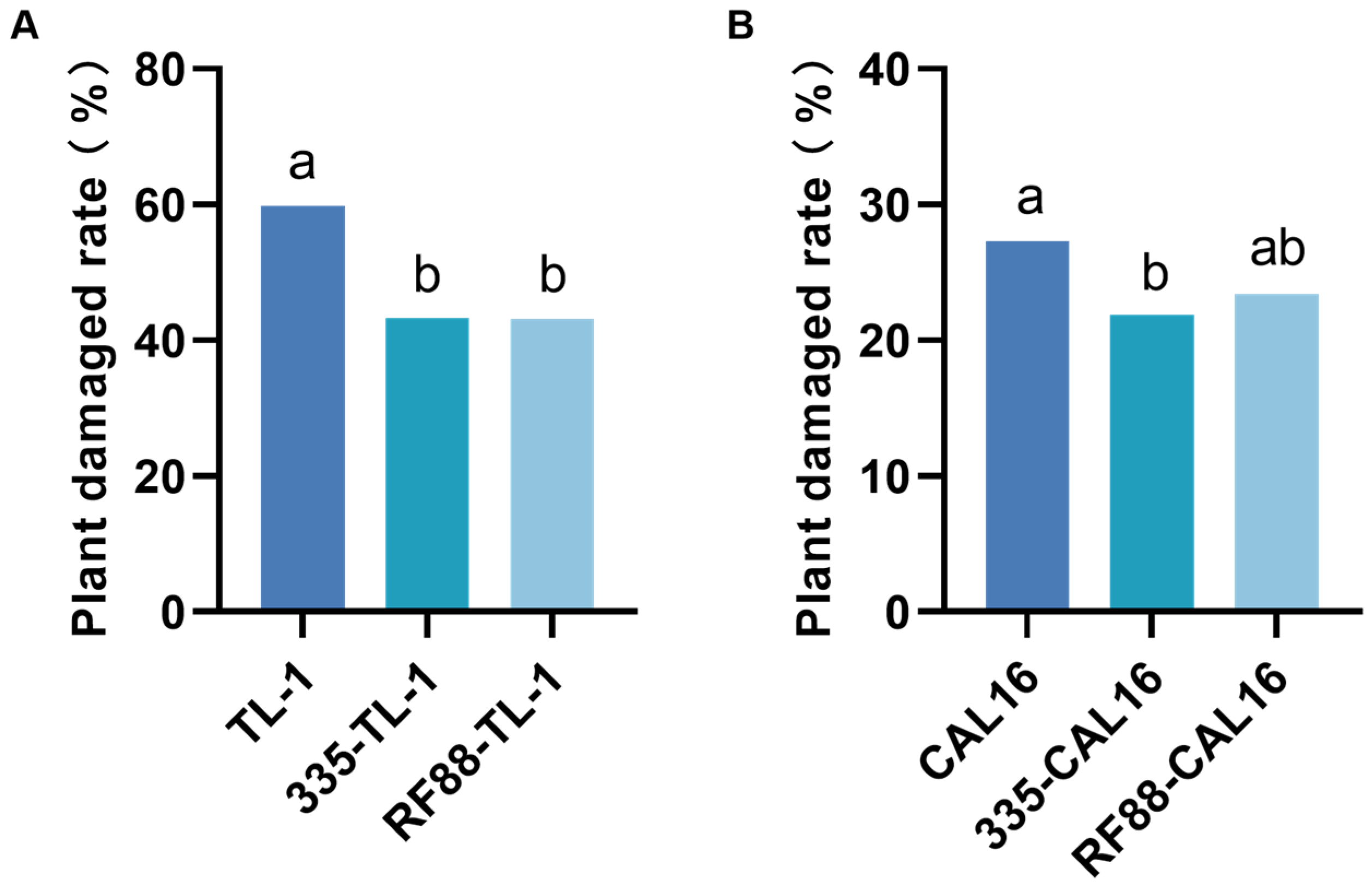

3.3. Control Efficacy of Strip Intercropping for S. exigua on Soybean Plant

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, D.; Song, G.Q. Expression of a maize SOC1 gene enhances soybean yield potential through modulating plant growth and flowering. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Jin, Z.; Christoph, M.; Thomas, A.; Chen, A.; Wang, T.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Occurrence of crop pests and diseases has largely increased in China since 1970. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Ficke, A.; Aubertot, J.N.; Holier, C. Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security. Food Secur. 2012, 4, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imura, O.; Shi, K.; Iimura, K.; Takamizo, T. Assessing the effects of cultivating genetically modified glyphosate-tolerant varieties of soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) on populations of field arthropods. Environ. Biosaf. Res. 2010, 9, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Gu, T.; Zhang, R.; Sun, X.; Yao, B.; Tu, T.; et al. Agricultural biotechnology in China: Product development, commercialization, and perspectives. aBIOTECH 2025, 6, 284–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Hussain, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Yong, T.; Du, J.; Shu, K.; Yang, W.; et al. Comparative analysis of maize–soybean strip intercropping systems: A review. Plant Prod. Sci. 2019, 22, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, D.J.; Gu, Y.; Cao, M.; Cui, Y.; Wang, X.; Asante-Badu, B. Overview of the advantages and limitations of maize-soybean intercropping in sustainable agriculture and future prospects: A review. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2022, 82, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Liu, X.; Hussain, S.; Ahmed, S.; Chen, G.; Yang, F.; Chen, L.; Du, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, W. Water use efficiency and evapotranspiration in maize-soybean relay strip intercrop systems as affected by planting geometries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, D.; Wang, E.; Liu, X.; Huth, N.I.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, W.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Yong, T.; et al. Modelling soybean and maize growth and grain yield in strip intercropping systems with different row configurations. Field Crops Res. 2021, 265, 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.S.; Adhikari, R.; Bhatta, D.; Poudel, A.; Subash, S.; Shrestha, S.; Shrestha, J. Initiatives for biodiversity conservation and utilization in crop protection: A strategy for sustainable crop production. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 4573–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W. Soybean maize strip intercropping: A solution for maintaining food security in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 2503–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Feng, C.; Li, N.; Sun, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, W. Soil biological health assessment based on nematode communities under maize and peanut intercropping. Ecol. Process. 2024, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Jia, W. Water and nitrogen utilization and growth simulation of soybean-maize strip intercropping: A review. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola Ambient. 2025, 29, e291193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Du, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhou, L.; Hussain, S.; Lei, L.; Song, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, F.; et al. Effects of reduced nitrogen inputs on crop yield and nitrogen use efficiency in a long-term maize-soybean relay strip intercropping system. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latati, M.; Benlahrech, S.; Lazali, M.; Sihem, T.; Ounane, S.M. Intercropping promotes the ability of legume and cereal to facilitate phosphorus and nitrogen acquisition through root-induced processes. Grain Legumes 2016, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, F.; Xing, G. Effects of fertilizer level and intercropping planting pattern with maize on the yield-related traits and insect community of soybean. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Xue, J.; Miu, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Huang, G. Effects of maize-soybean intercropping and nitrogen application on the characteristics of small and medium-soil animal communities in red soil. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 28, 2993–3002. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, Q.; Ouyang, F.; Gu, S.; Qiao, F.; Ge, F. Strip intercropping peanut with maize for peanut aphid biological control and yield enhancement. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 286, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Duan, R.; Li, R.; Zou, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Xing, G. Impacts of maize intercropping with soybean, peanut and millet through different planting patterns on population dynamics and community diversity of insects under fertilizer reduction. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 936039. [Google Scholar]

- Hüber, C.; Zettl, F.; Hartung, J.; Müller-Lindenlauf, M. The impact of maize-bean intercropping on insect biodiversity. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2022, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Tong, Q.; Xu, T.; Bi, S.J.; Hu, B.; Yun, H.; Hu, F.; Wang, Z. Effects of maize-soybean intercropping on the growth, development and reproduction of Spodoptera frugiperda grassland. J. Plant Prot. 2023, 50, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Gao, N.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, Y.; Niu, W.; Wang, L.; Feng, R. The use of soybean–corn strip compound planting implements in the yellow river basin of China for intercropping patterns in areas of similar dimensions. AgriEngineering 2024, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hallerman, E.M.; Liu, Q.; Wu, K.; Peng, Y. The development and status of Bt rice in China. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Desneux, N. Widespread adoption of Bt cotton and insecticide decrease 499 promotes biocontrol services. Nature 2012, 487, 362–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marvier, M.; McCreedy, C.; Regetz, J.; Kareiva, P. A meta-analysis of effects of Bt cotton and maize on nontar-501 get invertebrates. Science 2007, 316, 1475–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenbarger, L.L.; Naranjo, S.E.; Lundgren, J.G.; Bitzer, R.J.; Watrud, L.S. Bt crop effects on functional guilds of non-target arthropods: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2118. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Lu, Y.; Feng, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, J. Suppression of cotton bollworm in multiple crops in China in areas with Bt toxin-containing cotton. Science 2008, 321, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Li, S.; Yang, W.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X. Commercial genetically modified maize and soybean are poised following pilot planting in China. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, J.; Ren, Q.; Guo, J.; Ren, Q.; Guo, J.; Xiong, F.; Lu, D. Enhancing production efficiency through optimizing plant density in maize–soybean strip intercropping. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1473786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, M.; Gu, S.; Li, X. Egg-laying preference of female adults of cotton bollworm on 16 species of plants and their survival after larval feeding. J. Plant Prot. 2019, 45, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Specification for Environmental Safety Testing of Genetically Modified Soybean—Part 3: Detection of Impacts on Biodiversity; China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2003.

- Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China. Technical Specification for Environmental Safety Testing of Genetically Modified Maize—Part 3: Detection of Impacts on Biodiversity; China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2003.

- Hao, P.; Xiao, T.; Jing, X.; Li, T.; Yi, Z. Effects of intercropping on red soil aggregates and available phosphorus characteristics under different phosphorus levels. Soils Fertil. Sci. China 2022, 516, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Xiong, C.; Rui, Z.; Jing, L.; Min, H.; Ai, A. Effects of intercropping sorghum and soybeans on soil water distribution and water use efficiency. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2021, 50, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Research on the optimization of maize-soybean intercropping mode based on high yield and stable yield. Farm Mach. Using 2025, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, C.; Wen, M. Green, High-quality and high-efficiency cultivation techniques for soybean-maize strip intercropping. Agric. Henan 2025, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Higo, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Amano, T. Morphological characteristics to identify fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from common polyphagous noctuid pests for all instar larvae in Japan. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2022, 57, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.A.O.; Castaño Villa, G.J.; Pérez, E.M.O.; Rey, G.T.R.; Páez, F.A.R. Genus 1 sp. 2 (Diptera: Chironomidae): The potential use of its larvae as bioindicators. Environ. Anal. Ecol. Stud. 2018, 4, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.H.; Ivorra, T.; Heo, C.C.; Wardhana, A.H.; Hall, M.J.R.; Tan, S.H.; Mohamed, Z.; Khang, T.F. Accurate Identification of Fly Species in Forensic, Medical and Veterinary Entomology using Wing Venation Patterns. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.S.; Chang, H.H.; Jin, Z.T.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, X.M.; Ba, C.X.; Tian, X.H. The occurrence patterns of major pests in soybean maize intercropping and soybean maize monoculture. J. Appl. Entomol. 2024, 61, 864–870. [Google Scholar]

- Broatch, J.E.; Dietrich, S.; Goelman, D. Introducing data science techniques by connecting database concepts and dplyr. J. Stat. Educ. 2019, 27, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Tomalin, L.E.; Suárez-Fariñas, M. cosinoRmixedeffects: An R package for mixed-effects cosinor models. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.E.; Kristensen, K.; Van Benthem, K.J.; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C.W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H.J.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.M. Modeling zero-inflated count data with glmmTMB. bioRxiv 2017, 132753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilreath, R.T.; Kerns, D.L.; Huang, F.N.; Yang, F. No positive cross-resistance to Cry1 and Cry2 proteins favors pyramiding strategy for management of Vip3Aa resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1963–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.S.; Ward, J.M.; Levine, S.L.; Baum, J.A.; Vicini, J.L.; Hammond, B.G. The food and environmental safety of Bt crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likitvivatanavong, S.; Chen, J.; Evans, A.M.; Bravo, A.; Soberon, M.; Gill, S.S. Multiple receptors as targets of Cry toxins in mosquitoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, T.; Askari, M.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Abid, M.A.; Wei, Y.; Guo, S.; Liang, C.; Zhang, R. Current insights on vegetative insecticidal proteins (Vip) as next generation pest killers. Toxins 2020, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, R.; Wright, M.G. Effects of interplanting flowering plants on the biological control of corn earworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in sweet corn. J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soujanya, P.L.; Vanisree, K.; Giri, G.S.; Mahadik, S.; Jat, S.L.; Sekhar, J.C.; Jat, H.S. Intercropping in maize reduces fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) infestation, supports natural enemies, and enhances 541 yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 373, 109130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, S.; Collier, R.H. The influence of host and non-host companion plants on the behaviour of pest insects in field crops. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2012, 142, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansion-Vaquié, A.; Ferrer, A.; Ramon-Portugal, F.; Wezel, A.; Magro, A. Intercropping impacts the host location behaviour and population growth of aphids. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2020, 168, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conchou, L.; Lucas, P.; Meslin, C.; Proffit, M.; Staudt, M.; Renou, M. Insect odorscapes: From plant volatiles to natural olfactory scenes. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Owusu, J.; Vuts, J.; Caulfield, J.C.; Woodcock, C.M.; Withall, D.M.; Hooper, A.M.; Osafo-Acquaah, S.; Birkett, M.A. Identification of semiochemicals from cowpea, Vigna unguiculata, for low-input management of the legume pod borer, Maruca vitrata. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdei, A.L.; David, A.B.; Savvidou, E.C.; Džemedžionaitė, V.; Chakravarthy, A.; Molnár, B.P.; Dekker, T. The push–pull intercrop Desmodium does not repel, but intercepts and kills pests. eLife 2024, 13, e88695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letourneau, D.K.; Ambrecht, I.; Rivera, B.S.; Lerma, J.M.; Carmona, E.J.; Daza, M.C. Does plant diversity benefit agroecosystems? A synthetic review. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, S.; Palai, J.B.; Manasa, P.; Kumar, D.P. The potential of intercropping system in sustaining crop productivity. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannon, E.A.; Tamo, M.; Van, H.A.; Dicke, M. Effects of volatiles from Maruca vitrata larvae and caterpillar infested flowers of their host plant Vigna unguiculata on the foraging behavior of the parasitoid Apanteles taragamae. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Abrahams, P.; Bateman, M.; Beale, T.; Clottey, V.; Cock, M.; Colmenarez, Y.; Maizeiani, N.; Early, R.; Godwin, J.; et al. Fall armyworm: Impacts and implications for Africa. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2017, 28, 196–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdayanti, H.; Nurkomar, I. Diversity of natural enemies in maize-soybean intercropping with different plant compositions. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 985, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Pan, X.; Lan, X.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, R. Rational maize–soybean strip intercropping planting system improves interspecific relationships and increases crop yield and income in the China Hexi Oasis irrigation 567 area. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Liao, H.; Feng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shu, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of nitrogen supply on induced defense in maize (Zea mays) against fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, F.L.; Degrande, P.E.; Gauer, E.; Malaquias, J.B.; Scoton, A.M.N. Intercropped Bt and non-Bt corn with ruzigrass (Urochloa ruziziensis) as a tool to resistance management of Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith, 1797) 572 (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 3372–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, T.; Singh, A. Productivity potential, quality and economic viability of hybrid Bt cotton (Gossypium hirsutum)-based intercropping systems under irrigated conditions. Indian J. Agron. 2014, 59, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, A.R.; Thakare, S.K. Improving the fertilizer use efficiency and profitability of small farms by intercropping with transgenic Bt cotton. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 9, 3540–3548. [Google Scholar]

- Kusi, F.; Nboyine, J.A.; Adjebeng-Danquah, J.; Agrengsore, P.; Seidu, A.; Quandahor, P.; Sugri, I.; Adazebra, G.A.; Agyare, R.Y.; Asamani, E.; et al. Effect of insecticides and intercropping systems on fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith)) infestations and damage in maize in 491 northern Ghana. Crop Prot. 2024, 186, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Segura, V.; Grass, I.; Breustedt, G.; Rohlfs, M.; Tscharntke, T. Strip intercropping of wheat and oilseed rape enhances biodiversity and biological pest control in a conventionally managed farm scenario. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 59, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrare, V.S.; Kranthi, S.; Biradar, V.K.; Zade, N.N.; Sangode, V.; Kakde, G.; Shukla, R.M.; Shivare, D.; Khadi, B.M.; Kranthi, K.R. Widespread infestation of the exotic mealybug species Phenacoccus solenopsis (Tinsley) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) on cotton in India. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2009, 99, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Xia, B.; Li, P.; Feng, H.; Wyckhuys, K.; Guo, Y. Mirid bug outbreaks in multiple crops correlated with wide-scale adoption of Bt cotton in China. Science 2010, 328, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, R.; Ceddia, G.; Areal, F.J.; Park, J. The impact of secondary pest on Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesugi, R.; Köneke, A.; Sekine, T.; Tabuchi, K.; Herz, A.; Yoshimura, H.; Bockmann, E.; Shimoda, T.; Nagasaka, K. Intercropping and flower strips to enhance natural enemies and control aphids: A comparative study in cabbage fields of Japan and Germany. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2024, 59, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, D.; Baniwal, S.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S. Impact of alpha- terthienyl phototoxicity on mustard aphid (Lipaphis erysimi) and pea aphid (Acyrothosiphon pisum). Int. J. Entomol. Res. 2024, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sétamou, M.; Soto, Y.L.; Tachin, M.; Alabi, O.J. Report on the first detection of Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae) in the Republic of Benin, West Africa. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyenim-Boateng, K.G.; Lu, J.N.; Shi, Y.Z.; Yin, X.G. Review of leaf hopper (Empoasca flavescens): A major pest in castor (Ricinus communis). J. Genet Genom. Sci. 2018, 3, 009. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.A.; Ellsworth, P.C.; Faria, J.C.; Head, G.P.; Owen, M.D.; Pilcher, C.D.; Shelton, A.M.; Meissle, M. Genetically engineered crops: Importance of diversified integrated pest management for agricultural sustainability. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, K. Commercial strategy of transgenic insect-resistant maize in China. J. Plant Prot. 2022, 49, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Wu, K. Commercialization Strategy of Transgenic Soybean in China. Biotechnol. Bull. Chin. 2023, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Maize | Soybean | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lepidopterous Species | Number of Larvae (Mean ± SE) | Lepidopterous Species | Number of Larvae (Mean ± SE) | |

| 2023 | H. armigera | 2.37 ± 0.90 a | S. exigua | 9.62 ± 2.22 a |

| S. frugiperda | 0.67 ± 0.26 ab | H. recurvalis | 3.57 ± 1.36 ab | |

| S. exigua | 0.30 ± 0.01 b | L. indicata | 3.33 ± 1.46 b | |

| C. punctiferalis | 0.07 ± 0.06 b | Ascotis selenaria | 0.57 ± 0.19 b | |

| O. furnacalis | 0.07 ± 0.04 b | O. furnacalis | 0.52 ± 0.31 b | |

| M. separata | 0.07 ± 0.05 b | H. armigera | 0.43 ± 0.19 b | |

| 2024 | H. armigera | 13.48 ± 3.52 a | S. exigua | 3.22 ± 1.20 a |

| C. punctiferalis | 6.81 ± 2.62 ab | H. recurvalis | 0.19 ± 0.11 a | |

| O. furnacalis | 6.07 ± 1.02 ab | C. punctiferalis | 0.19 ± 0.11 a | |

| S. exigua | 0.89 ± 0.32 b | L. indicata | 0.10 ± 0.07 a | |

| S. litura | 0.15 ± 0.11 b | O. furnacalis | 0.05 ± 0.03 a | |

| L. indicata | 0.07 ± 0.05 b | A. selenaria | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | |

| 2025 | H. armigera | 14.52 ± 3.69 a | S. exigua | 12.10 ± 2.85 a |

| S. exigua | 3.78 ± 1.28 ab | A. selenaria | 0.19 ± 0.08 b | |

| O. furnacalis | 1.70 ± 0.54 b | H. armigera | 0.10 ± 0.05 b | |

| C. punctiferalis | 0.15 ± 0.07 b | H. recurvalis | 0.10 ± 0.06 b | |

| S.litura | 0.07 ± 0.02 b | - | - | |

| Source of Variation | H. armigera | S. exigua |

|---|---|---|

| Planting pattern (P) | 0.0232 * | 0.0023 ** |

| Genetically modified factors (G) | <0.0001 *** | <0.0001 *** |

| Year (Y) | <0.0001 *** | <0.0001 *** |

| G × P | 0.0933 | 0.7832 |

| G × Y | <0.0001 *** | 0.7139 |

| P × Y | 0.04813 * | 0.2037 |

| G × P × Y | 0.2542 | 0.1267 |

| Source of Variation | Damage Rate of Maize Plants | Damage Rate of Soybean Plants |

|---|---|---|

| Planting pattern (P) | 0.0007 *** | <0.0001 *** |

| Genetically modified factors (G) | <0.0001 ** | <0.0001 *** |

| Year (Y) | <0.0001 *** | <0.0001 *** |

| G × P | 0.1601 | 0.0236 * |

| G × Y | <0.0001 *** | <0.0001 *** |

| P × Y | 0.0962 | <0.0001 *** |

| G × P × Y | 0.1621 | <0.0001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, W.; Zhang, C.; Shen, Z.; Liu, L.; Ullah, M.S.; Yang, X.; Chen, G.; Han, L. Performance of Strip Intercropping of Genetically Modified Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122880

Zhao W, Zhang C, Shen Z, Liu L, Ullah MS, Yang X, Chen G, Han L. Performance of Strip Intercropping of Genetically Modified Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122880

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Wanxuan, Chen Zhang, Zhicheng Shen, Laipan Liu, Mohammad Shaef Ullah, Xiaowei Yang, Geng Chen, and Lanzhi Han. 2025. "Performance of Strip Intercropping of Genetically Modified Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122880

APA StyleZhao, W., Zhang, C., Shen, Z., Liu, L., Ullah, M. S., Yang, X., Chen, G., & Han, L. (2025). Performance of Strip Intercropping of Genetically Modified Maize and Soybean Against Major Target Pests. Agronomy, 15(12), 2880. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122880