Abstract

Elucidating shrub ecohydrological adaptation is critical for optimizing vegetation-restoration strategies in arid regions and maintaining regional ecological stability. This study examined typical desert shrubs at the northern edge of the Mu Us Sand Land. During the growth peak season (July–September), we measured understory-soil δ18O, soil water content (SWC), leaf δ13Cp, stem δ18O, and gas-exchange rates, and evaluated shrub drought resistance and water-use efficiency using Mantel tests and principal component analysis (PCA). Based on the VPDB standard, the δ13Cp values of leaves ranked as follows: Caragana microphylla (−27.21‰) > Salix psammophila (−27.80‰) > Artemisia ordosica (−28.48‰). The results indicate that leaf δ13Cp and water δ18O are effective indicators of shrub water-use efficiency, reflecting Cᵢ/Cₐ dynamics and water-transport pathways, respectively. The three shrubs exhibit distinct water-use strategies: Caragana microphylla follows a conservative strategy that relies on deep-water sources and tight stomatal regulation; Salix psammophila shows an opportunistic strategy, responding to precipitation pulses and drawing from multiple soil layers; Artemisia ordosica displays a vulnerable, shallow-water-dependent strategy with high drought susceptibility. SWC was the primary driver of higher Long Water Use Efficiency (WUE), whereas Mean Air Temperature (MMAT) and Mean Relative Humidity (MMRH) exerted short-term regulation by modulating the vapor-pressure deficit (VPD). We conclude that desert-shrub water-use strategies form a complementary functional portfolio at the community scale. Vegetation restoration should prioritize high-WUE conservative species, complement them with opportunistic species, and use vulnerable species cautiously to optimize community water-use efficiency and ecosystem stability.

1. Introduction

Water availability is a primary limiting factor for plant growth and development, and its spatiotemporal variability directly influences plant performance and distribution patterns [1]. Under global climate change, hydrological regimes in arid and semi-arid regions have shifted markedly, affecting plant growth [2] and intensifying survival pressures. For decades, vegetation planting has been a central strategy for ecological restoration in arid and semi-arid regions [3], and its success depends strongly on the match between species and regional water regimes. Accordingly, plant adaptability to water conditions is fundamental for sustaining normal growth and for establishing stable, long-lived windbreak and sand-fixing vegetation systems [4]. With advances in stable-isotope techniques, oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13Cp) isotopes have become, respectively, natural tracers of plant water sources [5] and indicators of water-use efficiency [6]. δ18O is increasingly preferred over traditional approaches such as root surveys/excavations [7] and sap-flow measurements [8], providing a more sensitive and accurate means to quantify plant water sources [9]. These isotopic methods are widely applied in croplands [10,11], plantation forests [12,13], and wetland vegetation to resolve water sources [14,15]. McCole et al. [16] showed that root depth structures water-source allocation: deep-rooted trees and shrubs predominantly use relatively stable deep-soil water, whereas shallow-rooted herbs rely on more variable near-surface water. Baoqing Liu et al. [17] quantified soil-water uptake depths for Pinus tabulaeformis, Caragana microphylla, and Artemisia frigida in the Horqin Sandy Land, and Su Wenxu et al. [18] recorded water-use depths for Larix principis-rupprechtii and Salix psammophila in the Hunshandake Sandy Land. Together, these studies consistently corroborate this pattern. Plant water-use efficiency is commonly evaluated as WUE and WUEi. WUE, a core comprehensive parameter characterizing plant physiological status [19], is derived by measuring leaf δ13Cp of plants, calculating Δ13C, and converting the resulting values. It also serves as a critical criterion for evaluating species suitability under climate change and water scarcity [20]. Plant carbon isotopes (δ13Cp) reflect time-integrated carbon assimilation, thereby indicating adaptation to water use and water stress over the integration period. δ13Cp is positively correlated with WUE [4]. Environmental drivers such as precipitation, relative humidity, and air temperature are primary regulators of WUEi [21]. Consistently, Zhao et al. [22] reported that soil moisture, plant transpiration, and air temperature are the dominant factors controlling WUEi.

Δ13C and δ18O can be jointly analyzed to evaluate and apply plant drought-resistance traits [23]. At physiological and molecular levels, drought stress perturbs plant cells by triggering reactive-oxygen-species (ROS) bursts, disrupting osmotic balance, and damaging membrane systems. Moderate ROS acts as signals that induce stomatal closure and stress-response gene expression, whereas excessive accumulation causes oxidative injury. Redox homeostasis is maintained by the glutathione–ascorbate cycle together with enzymatic defenses (SOD, POD, CAT) and non-enzymatic antioxidants [24]. Concurrently, proline—a key osmotic regulator [25]—acts with soluble sugars to alleviate osmotic stress [24]. Studies of arid-zone plants by Lü, X.-P., Yang, F., and Chang, Y. conclude that organic osmolytes are central to adaptation under prolonged drought [26,27,28].

During vegetation surveys in the Mu Us Sandy Land, we observed that, despite a shared macroclimate, Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica showed distinct growth performance and physiological responses during the growth peak season. Caragana microphylla maintained stable growth, whereas Salix psammophila and Artemisia ordosica frequently exhibited leaf wilting. This observation raises a core question: within the same climatic zone, which mechanisms determine interspecific differences in drought tolerance and water-use efficiency? Based on preliminary surveys and prior literature, we hypothesize that these differences arise from the joint effects of plant physiological regulation and environmental moisture regimes.

This study investigated gas-exchange rates, SWC, and stable isotopes for three typical desert shrubs along the northern edge of the Mu Us Sandy Land, including depth-resolved δ18O of soil and stems and leaf δ13Cp. Through repeated sampling over a period of months during the growth peak season, we assessed drought-resistance traits and temporal changes in water-use efficiency. To elucidate physiological response mechanisms and dominant drivers under variable environments, we analyzed species-specific water-use strategies and provided guidance for species selection and configuration in ecological restoration of arid regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

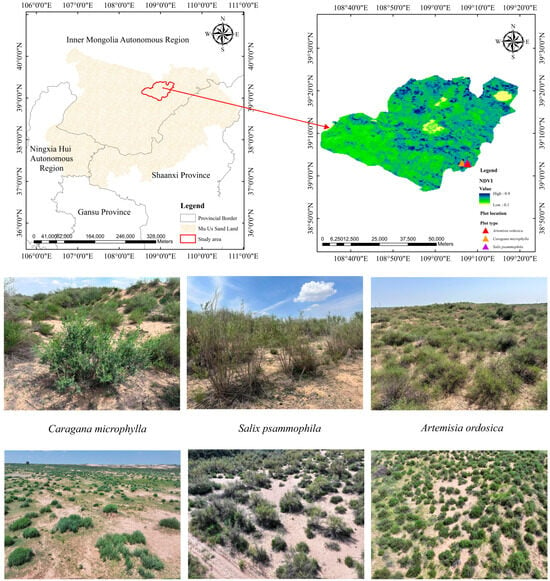

As shown in Figure 1, the study site is in the Wushen Banner, southwestern Ordos City, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. The area lies at the northern edge of the Mu Us Sandy Land and typifies a composite ecosystem of wind-blown sand, vegetation, and water resources. The study area is at an elevation of 1310–1330 m. Soils are typical sandy loam and are prone to severe wind erosion, which produces coarse soil structures. Groundwater generally occurs at depths of 3–5 m, and surface water consists mainly of seasonal rivers and lakes. The region has an arid–semi-arid temperate continental climate with pronounced diurnal temperature fluctuations. The annual average temperature is 6.0–8.5 °C, and annual precipitation is 350–400 mm, predominantly from May to August (over 75% of the annual total). Annual evaporation averages 2000–2800 mm, equivalent to 5–6 times the annual precipitation. Average annual sunshine is 2911.5 h, and the frost-free period is 123–156 d. Dominant plant species in this region include Salix matsudana, Salix psammophila, Juniperus sabina, Hippophae rhamnoides, Caragana microphylla, Artemisia ordosica, and Stipa grandis.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area and vegetation cover characteristics. Note: The base map is produced by the National Basic Geographic Information Center of the Ministry of Natural Resources, with the map review number “GS (2024) 0650”, and the boundaries of the base map have not been modified.

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Selection

Ecological restoration at the northern edge of the Mu Us Sandy Land relies heavily on local xerophytic shrubs. As dominant, functionally pivotal species, these shrubs are critical for maintaining ecosystem structure and function. The three most representative dominant shrubs in this area are Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica [4]. These shrubs play a leading role in local plant communities, exhibiting very high occurrence frequency and broad ecological niche breadth. This study was conducted during the peak vegetation growth season spanning July to September 2024. This study comprises three research sites, each dominated by a single plant species. The area of each site, delineated via UAV surveys and the corresponding vegetation coverage, is as follows: Caragana microphylla (28,164 m2, 34%), Salix psammophila (31,174 m2, 31%), and Artemisia ordosica (27,811 m2, 37%). Within each plot, three representative plants of similar topography and vigorous growth were selected. Three branches per plant were used as replicates. At a level site within each plot, a rain gauge, an evaporation pan, and an air temperature–humidity sensor were installed to monitor MMR (Monthly Mean Rainfall, mm), MME (Monthly Mean Evaporation, mm), MMAT (Monthly Mean Air Temperature, °C), and MMRH (Monthly Mean Relative Humidity, %). Data were logged every 10 min throughout the experimental phase. Table 1 summarizes plant growth status in the plots; Figure 2 presents the meteorological characteristics of the study area.

Table 1.

Growth status of plants in the plot.

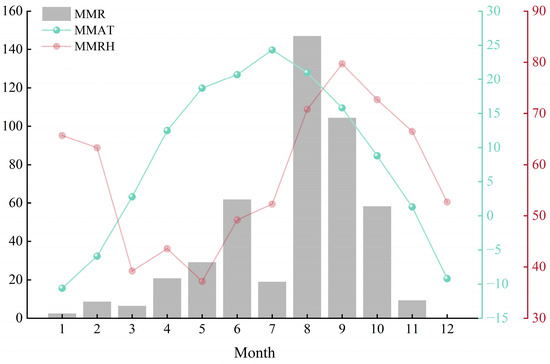

Figure 2.

Monthly variation characteristics of meteorological factors in the study area in 2024. MMR, NNE, MMAT, and MMRH denote the Monthly Mean Rainfall, Monthly Mean Evaporation, Mean Air Temperature, and Mean Relative Humidity, respectively.

Figure 2 presents the monthly variations in meteorological factors in the study area for 2024. Based on monthly records for 2024, the cumulative precipitation was 467.5 mm, the annual mean air temperature was 8.35 °C, and the annual mean relative humidity was 5.75%. MMR was uneven across months, and MMAT exhibited pronounced month-to-month variability. MMRH was strongly influenced by both MMR and MMAT, and the growth peak season occurred from July to September. The study used MME values for July, August, and September—179.9, 135.6, and 78.7 mm, respectively.

The total rainfall during the growth peak season in the study area was 270.4 mm, accounting for 57.84% of annual precipitation. Within this period, August recorded the highest MMR at 147 mm. July was exceptionally dry, with MMR of only 19 mm. Nevertheless, July recorded the highest MMAT of the year (24.3 °C), and MME reached 179.9 mm. At the same time, the evaporation in that month was 9.5 times the precipitation, indicating a severe drought climate. Relative humidity exhibited an inflection in July; the combination of low MMR and high MMAT likely subjected plants to drought stress. With increased rainfall in August, air temperature trended downward, whereas relative humidity continued to rise, peaking at 79.7% in September.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Determination of Leaf Carbon Isotopes

Field Sample Collection

The experiment was conducted during the growth peak season (July–September 2024). Sampling was performed three times per month on sunny days with no rainfall during the preceding three days. Sampling took place between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. on each sampling day. Forty to fifty intact leaves were collected from the sun-exposed central canopy of each plant and used as replicates. After collection, leaves were placed in kraft-paper sample bags.

Indoor Testing

Plant leaf samples were sent to the Wind-Sand Physics Experiment Building of the Inner Mongolia Agricultural University and dried in an oven at 65 °C for 24 h. After drying, samples were ground in a pulverizer, sieved through a 100-mesh screen, and stored in sealed polyethylene bags to prevent moisture reabsorption. The powdered sample was placed in a tin boat, weighed to approximately 2 mg on a microbalance, and sealed to complete sample preparation. The prepared samples were combusted at high temperatures in an elemental analyzer. Carbon (C) was oxidized to CO2, which was detected by a thermal conductivity detector. The carbon content was calculated by comparing sample peak areas with those of 2–3 working standards. The 13C/12C ratio of CO2 was determined using an isotope mass spectrometer.

Calculation Method

The δ13Cp value of the sample was calculated by comparing the measured CO2 13C/12C ratio with the international standard (VPDB). δ13Cp (plant leaf carbon-isotope ratio) reflects isotopic fractionation during photosynthesis. The calculation formula is:

δ13Cp denotes the per-mille (‰) deviation of the sample (13C/12C) ratio relative to the standard sample, 13C/12Cp represents the sample (13C/12C) ratio, and (13C/12C)VPDB denotes the (13C/12C) ratio of the standard material VPDB.

The atmospheric CO2 carbon-isotope ratio (δ13C) is a standardized parameter that describes the carbon-isotope composition of atmospheric CO2 [29]. It is used to remove the influence of atmospheric background values when calculating leaf stable carbon isotope ratios (Δ13C). The calculation formulas are:

δ13Ca is expressed in per mille (‰), t denotes the sampling year; in this study, t = 2024. Substituting into Equation (2) yields δ13Ca = −9.28‰.

Δ13C (stable carbon-isotope fractionation in plant leaves) reflects the extent of isotopic fractionation during photosynthesis. The calculation method for this indicator is as follows:

Δ13C is expressed in per mille (‰). δ13Cp and δ13Ca represent the carbon-isotope ratios of plant leaves and atmospheric CO2, respectively.

Ca (Atmospheric CO2 concentration) denotes the molar mixing ratio of CO2 in air, indicating the availability of carbon for plant photosynthesis. It is a pivotal variable linking the global carbon cycle to plant physiological processes; its dynamics directly regulate ecosystem productivity and climate adaptability. The calculation formula is as follows:

t denotes the sampling year; in this study, t = 2024. Substituting t = 2024 into Equation (4) yields Ca = 395.14 μmol/mol.

WUE (Long Water Use Efficiency) is the amount of carbon fixed per unit of water consumed over a plant’s growth cycle. It can be indirectly estimated from carbon-isotope resolution (Δ13C), thereby indicating a plant’s integrated regulation of the carbon-water balance and its adaptive strategy under variable environments. The calculation formula is:

WUE is expressed in μmol mol−1; a = −4.4‰ denotes the diffusive fractionation coefficient for CO2 entering stomata; b = 27‰ represents the fractionation coefficient during CO2 carboxylation by Rubisco; 1.6 is the diffusivity ratio of water vapor to CO2 in air; and Ca denotes the atmospheric CO2 concentration.

2.3.2. Plant and Soil Oxygen Isotope Analysis

Field Sample Collection

The experiment was conducted during the growth peak season (July–September 2024). To minimize sampling error, three sampling rounds were conducted per month. Sampling was carried out on sunny days with no rainfall during the preceding three days, between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. Each sampling point was located midway along the transect from the plant center (origin) to the canopy edge above the root zone. To minimize isotopic enrichment caused by stomatal transpiration, stems older than two years were selected. Branch segments approximately 0.3–0.5 cm in diameter and 3–5 cm in length were sampled from fully lignified, mature secondary woody branches. Three replicates were collected per plant after removing the outer bark. Within a 1 m radius of each plant, soil was extracted from 0 to 100 cm depth using a soil auger. The soil profile was partitioned into five layers, each 20 cm thick. All samples were immediately placed in 10 mL amber glass vials, sealed with parafilm, and stored in a portable refrigerator at 4 °C.

Indoor Testing

Within ten days following the completion of sampling, at the Wind-Sand Physics Laboratory of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, the LI–2100 Automatic Vacuum Cold Condensation Extraction System, developed by Beijing Ruijia United Technology Co., Ltd., was employed to extract moisture from plant stem and soil samples. Impurities were removed using a 0.22 µm membrane filter, and oxygen isotopes in the water samples were analyzed with an isotope mass spectrometer.

Calculation Method

The δ18O value (oxygen-isotope ratio of water from plant stems and soils) is calculated by comparing the sample 18O/16O ratio with the international standard (VSMOW). The calculation formula is:

δ18O is expressed in per mille (‰), (18O/16O)sample denotes the isotopic ratio of oxygen-18 to oxygen-16 in the sample, and (18O/16O)SMOW denotes the corresponding ratio in the standard material.

2.3.3. Determination of Soil Moisture Content

Field Sample Collection

Experiments were conducted during the growth peak season (July–September 2024). Sampling was conducted three times per month on sunny days with no rainfall during the preceding three days. Samples were collected between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. on each sampling day. Within a 1 m radius of each study plant, soil was extracted from 0 to 100 cm depth using a soil auger. The soil profile was partitioned into 10 layers, each 10 cm thick. Collected soil samples were placed in pre-weighed aluminum boxes (55 × 35 mm), and the total mass was recorded. Each soil layer was sampled in triplicate.

Indoor Testing

After sampling was complete, the samples were transported to the Wind-Sand Physics Experiment Building of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University. The samples were weighed on a precision balance with an accuracy of 0.0001 g, and the mass was recorded as the combined mass of fresh soil and the aluminum container. The container was opened and placed in an oven at 105 °C. The samples were then dried for 24 h, then removed and weighed. The mass was recorded as the combined mass of dried soil and the aluminum container.

Calculation Method

SWC (Soil Water Content) is the mass of water per unit mass of dry soil and is a fundamental metric of soil moisture. The test employed the oven-drying method using aluminum boxes; the gravimetric formula is:

WSC is expressed as a percentage (%), Mwet represents the combined mass of wet soil and the aluminum container, Mdry denotes the combined mass of oven-dried soil and the aluminum container, and Mtin indicates the mass of the aluminum container.

2.3.4. Measurement of Gas Exchange in Plants

Gas Exchange Measurements

The experiment was conducted during the growth peak season (July–September 2024). Measurements were taken three times per month to reduce measurement error. Field measurements were conducted on sunny days with no rainfall during the preceding three days, between 8:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. Ten unshaded, well-illuminated, fully expanded leaves were selected as replicates from the sunlit canopy. Measurements were conducted using the Li-6800 Portable Photosynthesis System (manufactured by LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA), which is equipped with a 2 cm2; fluorescent leaf chamber; external instrument parameters were adjusted to align with in situ field conditions. Pn and Tr were measured monthly for plants in the study area.

Calculation Method

WUEi (Instantaneous Water Use Efficiency) is the amount of CO2 fixed per unit water lost by a plant at a given moment. The calculation formula is:

WUEi is expressed in mmol·mol−1; Pn denotes net photosynthetic rate, Tr denotes transpiration rate.

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

One-way ANOVA tested monthly differences in photosynthetic parameters, soil water content, soil and stem δ18O, and plant water-use efficiency. Before ANOVA, data normality and homoscedasticity were assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Mantel tests quantified correlations between plant indices and meteorological factors; results were visualized as correlation heatmaps. For principal component analysis (PCA), variables were selected a priori based on ecological relevance and prior studies; all variables were standardized to z-scores to remove scale effects, and key drivers of plant water-use dynamics were identified using a 3D PCA plot. Data processing and statistical analyses were performed in Excel 2010 and SPSS Statistics 27, and figures were generated in Origin 2024 and R 4.5.0.

3. Results

3.1. Soil Moisture Content and Oxygen Isotope Characteristics in Shrubland Understory Soils

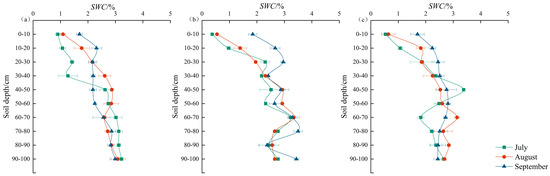

During the growth peak season, SWC (soil water content) in the study plots of Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica ranged from 0.90 to 3.22%, 0.37–3.37%, and 0.53–3.14%, respectively. The mean SWC values were 2.37% ± 0.68%, 2.44% ± 0.01, and 2.28% ± 0.03, respectively. Average SWC were ranked as follows: Salix psammophila > Caragana microphylla > Artemisia ordosica, indicating higher soil moisture under Salix psammophila. As shown in Figure 3a–c, the monthly mean SWC in Caragana microphylla plots generally increased initially and then declined. During the growth peak season, SWC rose continuously at 0–30 cm, increased and then decreased at 30–60 cm (peaking at 2.77% in August), and reached a maximum of 3.12% at 60–100 cm in July. In the Salix psammophila plot, monthly mean SWC generally exhibited an upward trend. During the growth peak season, SWC at 0–30 cm increased markedly, peaking at 2.49% in September. At 30–60 cm, SWC first increased and then decreased, peaking at 2.72% in August. At 60–100 cm, SWC remained stable before rising rapidly to a peak of 3.15%, the highest among all plots. In the Artemisia ordosica plot, the monthly mean SWC showed an overall gradual increase with a decelerating rate. During the growth peak season, SWC at 0–30 cm continued to rise, whereas at 30–60 cm it first decreased and then increased, reaching a trough of 2.46% in August. At 60–100 cm, SWC first increased and then decreased, peaking at 2.83% in August.

Figure 3.

Soil moisture characteristics in the shrubland understory. (a) Soil moisture content of Caragana microphylla, July–September; (b) soil moisture content of Salix psammophila, July–September; (c) soil moisture content of Artemisia ordosica, July–September.

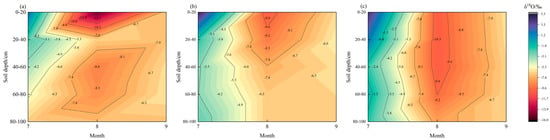

As shown in Figure 4a, δ18O values of soil water beneath Caragana microphylla shrubland generally decreased with increasing soil depth in July. At 0–20 cm, enhanced evaporation in July enriched δ18O in the surface soil, reaching 1.92‰. At 80–100 cm, δ18O was depleted, reaching −6.51‰. In August, a sharp increase in rainfall drove δ18O to a minimum of −15.18‰ across the Caragana microphylla soil profile, while values at 80–100 cm were −7.00‰, indicating strong precipitation effects in shallow layers and relative stability at depth. In September, δ18O values beneath Caragana microphylla converged across depths (−6.83 to −6.85‰), indicating thorough mixing of soil water. As shown in Figure 4b, in July, δ18O in soil water beneath Salix psammophila shrubland declined steeply and then stabilized. At 0–20 cm, enhanced evaporation enriched δ18O in surface soil, peaking at 5.04‰. At 40–60 cm, values decreased sharply to −2.92‰; at 80–100 cm, they stabilized with a slight increase to −2.24‰. In August, δ18O in soil water beneath Salix psammophila was uniformly depleted, indicating rainfall influenced the entire 0–100 cm profile. By September, δ18O at all depths converged to −5.71 to −6.42‰, suggesting a uniform water source. As shown in Figure 4c, in July, δ18O in soil water beneath Artemisia ordosica shrubland declined steeply and then stabilized. At 0–20 cm, enhanced evaporation enriched δ18O in the surface layer, reaching 4.37‰. At 60–80 cm, values rose slightly to −0.35‰. This depth range may have experienced short-term δ18O enrichment due to increased plant root exudates that enhanced local clay content, forming a biogenic microstructure layer that impeded water flow and intensified evaporation. In August, δ18O in soil water beneath Artemisia ordosica was uniformly depleted from 0 to 60 cm, indicating rainfall influence across this interval. At 80–100 cm, values reached −7.84‰. In September, δ18O beneath Artemisia ordosica converged across all depths (−6.45 to −6.05‰), indicating thorough soil-water mixing and a uniform water source.

Figure 4.

Soil-water oxygen-isotope characteristics. (a) Soil-water δ18O beneath Caragana microphylla, July–September; (b) Soil-water δ18O beneath Salix psammophila, July–September; (c) Soil-water δ18O beneath Artemisia ordosica, July–September.

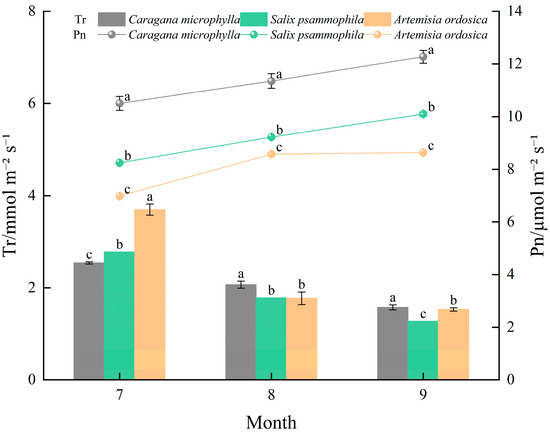

3.2. Gas Exchange Variables

As shown in Figure 5, photosynthetic parameters of the three shrubs showed highly significant correlations (p ≤ 0.01), and Pn exhibited an overall monthly upward trend from July to September, the net photosynthetic rates of Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica increased by 16.88%, 22.46%, and 23.74%, respectively, peaking in September at 12.27, 10.10, and 8.63 µmol·m−2·s−1. Tr showed an overall decreasing trend; from July to September, the reported percentage changes for Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica were +38.00%, +54.19%, and +58.64%, respectively, with trough values in September of 1.57, 1.27, and 1.53 mmol·m−2·s−1. Accordingly, during the growth peak season, the stability of photosynthetic parameters ranked as: Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica.

Figure 5.

Characteristics of gas exchange variables. Different lowercase letters above bars and lines denote significant differences in photosynthetic parameters among plant species within the same month (p < 0.05).

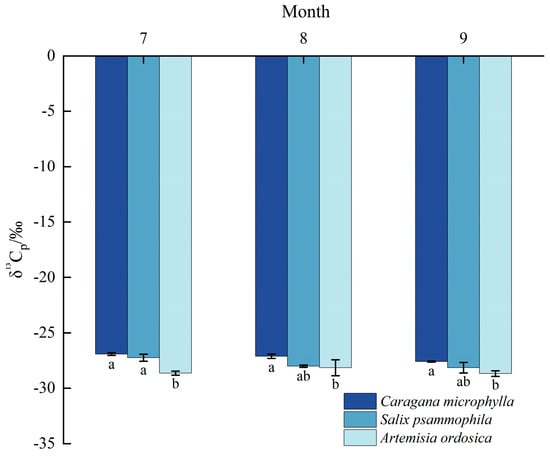

3.3. Characteristics of Stable Carbon Isotope Parameters in Typical Shrub Leaves

As shown in Figure 6, leaf δ13Cp ranged from −27.60 to −26.92‰ for Caragana microphylla, −28.66 to −27.05‰ for Salix psammophila, and −28.92 to −27.51‰ for Artemisia ordosica. The results indicate that during the growth peak season, the δ13Cp values ranked in descending order as Caragana microphylla (−27.21‰) > Salix psammophila (−27.80‰) > Artemisia ordosica (−28.48‰). Caragana microphylla reached its highest δ13Cp in July (−26.92‰); Salix psammophila also peaked in July (−27.25‰); Artemisia ordosica peaked in August (−28.15‰) during the growth peak season.

Figure 6.

Carbon−isotope ratio characteristics of shrub leaves. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences in leaf carbon−isotope ratios (δ13Cp) among plant species within the same month (p < 0.05).

Δ13C of plant leaves (stable carbon-isotope fractionation) reflects the extent of isotopic fractionation in plant tissues relative to the atmosphere. As shown in Figure 7, in July, the 13C fractionations during CO2 fixation were ranked as follows: Artemisia ordosica (19.32‰) > Salix psammophila (17.95‰) > Caragana microphylla (17.61‰). In August, Δ13C were ranked as follows: Artemisia ordosica (18.84‰) > Salix psammophila (18.70‰) > Caragana microphylla (17.82‰). In September, 13C fractionations were ranked as follows: Artemisia ordosica (19.36‰) > Salix psammophila (18.84‰) > Caragana microphylla (18.29‰). Accordingly, Caragana microphylla exhibited the lowest 13C fractionation throughout the growth peak season.

Figure 7.

Isotopic resolution. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences in Δ13C among plant species within the same month (p < 0.05).

3.4. Typical Desert Shrubs’ Drought Resistance Characteristics

In July, MMP was 19 mm, MME and MMAT peaked at 179.9 mm and 24.3 °C, respectively, characterizing a dry month. As shown in Figure 8a, leaf δ13Cp in July was −26.92‰ (Caragana microphylla), −27.75‰ (Salix psammophila), and −28.63‰ (Artemisia ordosica). These values indicate δ13Cp enrichment consistent with high WUE across all three species. Stem δ18O values were −8.56‰ (Caragana microphylla), −8.89‰ (Salix psammophila), and −6.23‰ (Artemisia ordosica), implying that Caragana microphylla and Salix psammophila maintained higher stomatal conductance—likely via groundwater uptake through deep root systems [30,31,32]—whereas Artemisia ordosica showed lower conductance due to its shallow root distribution [33]. Overall, July drought tolerance ranked as: Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica.

Figure 8.

Monthly variation characteristics of stem oxygen isotopes and leaf carbon isotopes. (a) δ13Cp of leaves and δ18O of stems of three shrubs in July; (b) δ13Cp of leaves and δ18O of stems of three shrubs in August; (c) δ13Cp of leaves and δ18O of stems of three shrubs in July and August. Different lowercase letters below bars denote significant differences (p < 0.05) in leaf carbon-isotope ratios (δ13Cp) and stem oxygen-isotope ratios (δ18O) among plant species within the same month.

In August, MMR rose to 147 mm, MME and MMAT reached 135.6 mm and 21 °C, respectively, indicating relief from drought stress that month. MMRH increased to 70.8%. As shown in Figure 8b, leaf δ13Cp in August was −27.12‰ (Caragana microphylla), −28.01‰ (Salix psammophila), and −28.15‰ (Artemisia ordosica). For Salix psammophila, a relatively enriched δ13Cp is consistent with maintaining higher WUE, whereas a more negative δ13Cp signal has been associated with photosynthetic recovery under pulse precipitation [34]. The slightly more negative δ13Cp of Artemisia ordosica and its reduced WUE are consistent with the findings of Yan Jiang et al. [35]. Stem δ18O values for the three shrubs ranged from −6.03‰ to −6.42‰. For Salix psammophila, stem δ18O increased to −6.03‰, indicating elevated stomatal conductance and high water consumption after rainfall pulses [36]. Artemisia ordosica remained relatively stable [37], showing a slight decrease to −6.53‰ and becoming the species with the lowest stomatal conductance during the same period. Taken together, drought tolerance in August ranked as: Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica.

In September, MMR declined to 104.4 mm, and MME and MMAT decreased to 78.7 mm and 15.8 °C, respectively, indicating moderate drought conditions. As shown in Figure 8c, Caragana microphylla maintained high WUE (−27.06‰) throughout September, whereas the WUE of Salix psammophila and Artemisia ordosica continued to decline while sustaining autumn photosynthetic carbon assimilation [38]. Stem δ18O values further increased, ranging from −4.59‰ to −5.81‰. Artemisia ordosica exhibited the highest value (−4.59‰) and the greatest stomatal conductance, indicating strong reliance on prior water reserves [39]. Salix psammophila showed a slightly lower value (−4.79‰), reflecting moderate regulation of stomatal conductance. Overall, September drought resistance ranked as: Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica.

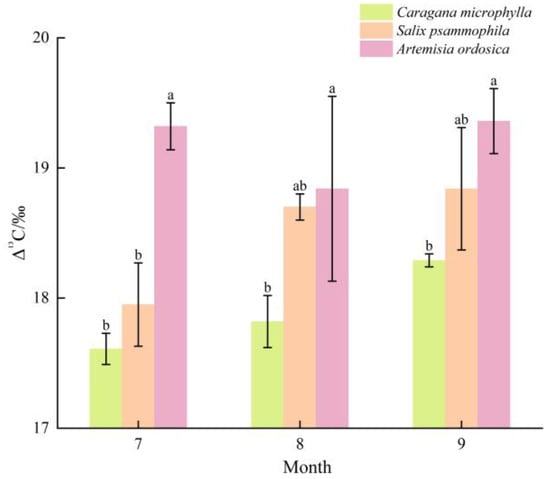

3.5. Water Use Efficiency Characteristics of Typical Sandy Shrubs

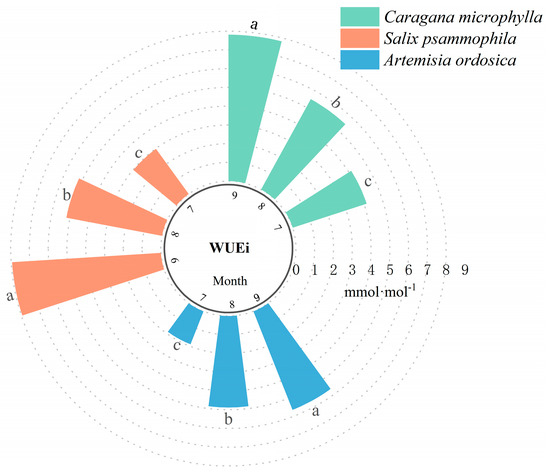

WUEi is a core indicator for assessing plant adaptation to arid environments in desert ecosystems [40]. Among-species comparisons of WUEi were highly significant (p ≤ 0.01). As shown in Figure 9, July WUEi were ranked as follows: Caragana microphylla (4.14 mmol·mol−1) > Salix psammophila (2.97 mmol·mol−1) > Artemisia ordosica (1.89 mmol·mol−1), indicating a pronounced among-species disparity. This disparity may arise from Caragana microphylla’s extensive root system [41], which enables deeper soil-moisture uptake [42] and results in higher WUEi. Artemisia ordosica exhibited the lowest WUEi during this period, as its shallow root distribution hampers maintaining a balance between carbon gain and water loss under arid conditions [43]. In August, WUEi were ranked as follows: Caragana microphylla (5.50 mmol·mol−1) > Salix psammophila (5.19 mmol·mol−1) > Artemisia ordosica (4.87 mmol·mol−1). This pattern suggests that increased regional precipitation partially alleviated drought stress, allowing WUEi across the three shrubs to increase more uniformly [44]. In September, the WUEi of the three shrubs reached their peak values, following the order of Salix psammophila (7.94 mmol·mol−1) > Caragana microphylla (7.81 mmol·mol−1) > Artemisia ordosica (5.65 mmol·mol−1). Salix psammophila maintained efficient growth through photosynthesis with stable photosynthetic enzyme activities in September [45]. Overall, during the peak growth period, the WUEi of these three typical psammophytic shrubs showed the order of Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica.

Figure 9.

WUEi characteristics of shrubs. Different lowercase letters above bars denote significant differences in WUEi among plant species within the same month (p < 0.05).

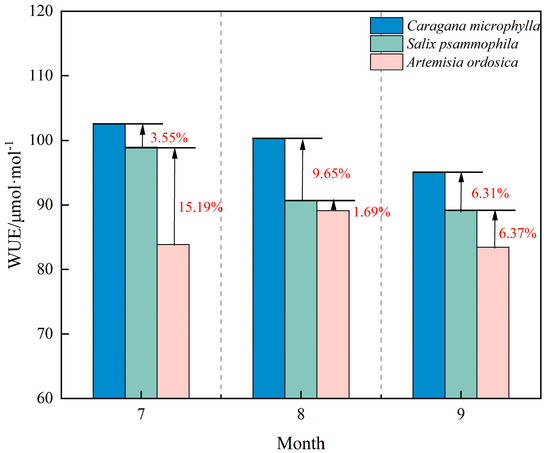

WUE is a core ecophysiological indicator integrating photosynthetic carbon fixation and water loss, directly reflecting plant carbon–water coupling. As shown in Figure 10, overall WUE ranked as Caragana microphylla > Salix psammophila > Artemisia ordosica. During the growth peak season, Caragana microphylla and Salix psammophila declined month by month, reaching troughs in September with reductions of 7.24% and 9.89%, respectively. This pattern suggests decreased Rubisco activity, with a greater decline in net photosynthetic rate than in transpiration rate [46], reflecting high responsiveness to environmental change. Artemisia ordosica showed little WUE variation across the growth peak season, following a symmetric increase-decrease pattern and peaking at 90.68 μmol·mol−1 in August.

Figure 10.

WUE characteristics of shrubs.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physiological Response Differences Among Three Shrub Species During the Growth Peak Season

Plant community adaptation to environmental conditions drives adjustments in physiological function. This study shows that during the growth peak season (July–September), three desert shrubs expressed differentiated physiological responses under distinct water-use efficiency strategies [4]. Across the growth peak season, Pn increased month by month in Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica by 16.88%, 22.46%, and 23.74%, respectively, while Tr decreased (Figure 5). These dynamics indicate that as the growth peak season progresses, plants regulate stomatal behavior and photosynthetic metabolism to track changing environmental conditions. Temporal shifts in shrub photosynthetic parameters are tightly coupled to seasonal water availability [47]. Caragana microphylla maintained high WUE and WUEi throughout the growth peak season and showed the most stable Pn and Tr trajectories. This performance is consistent with smaller xylem vessel diameters and thicker walls that confer higher resistance to pit-related hydraulic failure [48], sustaining water transport through September. Mechanistically, guard cells precisely regulate stomatal conductance (gs) via abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, while Pn is maintained by stable photosynthetic enzyme activity in mesophyll cells [49]. These traits reflect strong buffering against environmental stress and a conservative water-use strategy [48]. By contrast, Pn in Salix psammophila surged under intense August precipitation, evidencing sensitivity to precipitation pulses and an opportunistic water-use strategy [48], thereby maximizing carbon acquisition under ample water [50]. Artemisia ordosica exhibited lower WUE and WUEi with the greatest Tr reduction, revealing a drought-vulnerable water-use strategy linked to shallow rooting. Its early-drought stomatal-closure efficiency was lower than in the other two shrubs. Although larger xylem vessels facilitate rapid post-rainfall transport, they entail a higher risk of pit-mediated failure. Short-term drought induces vessel plugging, and even after water conditions improve, hydraulic function recovers slowly [51]. The conservative strategy of Caragana microphylla, the opportunistic strategy of Salix psammophila, and the vulnerable strategy of Artemisia ordosica align with Schwinning’s predictive framework [52]. Thus, water-use strategies in sandy ecosystems are non-random; they represent adaptive optima shaped by precipitation regimes to maximize carbon gain.

4.2. Plant Water Source Allocation and Drought Resistance Traits

Plant water-use strategies in arid environments are tightly linked to drought resistance, with source-water selection at the core of these strategies. By comparing stem-water and depth-resolved soil-water δ18O and integrating these with WUE, this study reveals fundamental interspecific differences in source-water allocation and the resulting drought-resistance traits [20]. Caragana microphylla followed a pattern typical of deep-rooted, drought-tolerant shrubs [47]. Prioritizing stable deep-water sources underpinned sustained high Pn and WUE during drought, providing the physiological basis for its drought resistance. This also reflects a conservative, stable drought-tolerance pattern [17]. By contrast, Salix psammophila exhibits an opportunistic water-use pattern. In July, stem-water δ18O (−8.89‰) approximated deep-soil water, indicating drought tolerance. After increased August precipitation, stem-water δ18O shifted toward enrichment to −6.03‰—the least negative among the three species. This shift paralleled soil-water δ18O depletion across depths, indicating rapid root-system reallocation and efficient use of pulse precipitation throughout the profile [53]. This strategy enables rapid growth during wet periods but renders water status and WUE highly sensitive to precipitation variability. Consequently, its drought tolerance is strongly environment-dependent and entails a higher risk [18]. However, Huang L. reported that Salix psammophila primarily relies on deep-soil water and groundwater as long-term sources [54]. This distinction likely reflects differences in groundwater recharge conditions and topographic variation within the study area. The water-use pattern of Artemisia ordosica reveals constraints inherent to shallow-water reliance. Throughout the growth peak season, its stem-water δ18O was the most enriched (least negative) among the three species—July (−6.24‰), August (−6.53‰), and September (−4.59‰). This pattern aligns with the δ18O signature of surface soil water, which is strongly enriched by evaporation and preferentially taken up. This constrained source-water allocation imposed severe drought stress during dry periods, resulting in persistently low WUE. The highest stem-water δ18O in September confirms heightened reliance on shallow soil water at the end of the growth peak season, further diminishing drought tolerance. This conclusion aligns with observations from the Tengger Desert reported by [54].

4.3. Plant Stomatal Control and Carbon Balance

In arid environments, plant survival hinges on balancing carbon fixation with water loss, a process primarily regulated by stomatal behavior [55]. Leaf δ13Cp, which integrates long-term variation in stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity, is a reliable indicator of carbon balance [49]. Across the growth peak season, leaf δ13Cp ranked as follows: Caragana microphylla (−27.21‰) > Salix psammophila (−27.80‰) > Artemisia ordosica (−28.48‰). This ordering corresponds to the interspecific ranking of WUE [Jan Binter]. According to the Farquhar model, a more negative δ13Cp indicates a higher Ci/Ca ratio at the leaf scale [56]. Such depletion typically reflects more open stomata or reduced carboxylation capacity, leading to stronger Δ13C and lower WUE. This point has been verified in the research of this article (Figure 7 and Figure 10). Nevertheless, under extreme stress, δ13Cp can yield biased inferences about stomatal control. Under severe drought or heat that markedly impairs Rubisco activity [57], the dominant constraint on photosynthesis shifts from stomatal to non-stomatal limitation. This shift causes an irreversible decline in Pn, whereas WUE fails to increase as expected. In this study, Pn in all three shrubs remained elevated and peaked in September. These patterns indicate that elevated δ13Cp together with high WUE primarily reflects efficient stomatal regulation that limits water loss while sustaining carbon fixation, rather than impaired photosynthetic function.

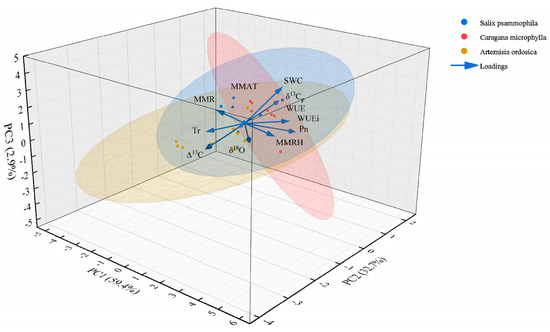

4.4. Effects of Meteorological Factors on Shrub Photosynthetic Parameters and Stable Isotopes

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) clarifies how environmental drivers intersect with species-intrinsic strategies to shape plant physiological patterns. As shown in Figure 11, PC1–PC3 together explained 95.08% of the total variance. Individually, PC1 = 59.43%, PC2 = 32.70%, and PC3 = 2.95%. PC1 captures the common physiological response of all species to synergistic water–heat dynamics during the growth peak season. Its gradient tracks the environmental continuum from July drought stress to improved moisture in September across the study area. This pattern aligns with Wang et al. [58], which emphasizes regional climate control over physiological rhythms and highlights the strong constraint of large-scale moisture regimes on physiological activity in sandy ecosystems. PC2 represents intrinsic differentiation in species’ water-use strategies. The three shrubs showed consistent and temporally stable positions along PC2. Caragana microphylla consistently occupied the positive end of PC2, maintaining stable Pn, elevated δ13Cp, and high WUE across the growth peak season. This configuration is consistent with a conservative strategy that combines deep-rooted access to stable water with efficient stomatal regulation [59]. However, the PC2 scores of Salix psammophila fluctuated markedly—especially after precipitation pulses—indicating a shift that prioritized growth over sustained WUE enhancement, a self-regulatory pattern consistent with an opportunistic strategy [59]. Artemisia ordosica consistently clustered at the negative end of PC2 and, in the dry month of July, simultaneously occupied low PC1 and low PC2 positions. This pattern corroborates vulnerability arising from shallow-water dependence and passive stomatal regulation, consistent with its narrow ecological niche [60].

Figure 11.

PCA of meteorological factors, plant photosynthetic parameters, and carbon−oxygen isotopes.

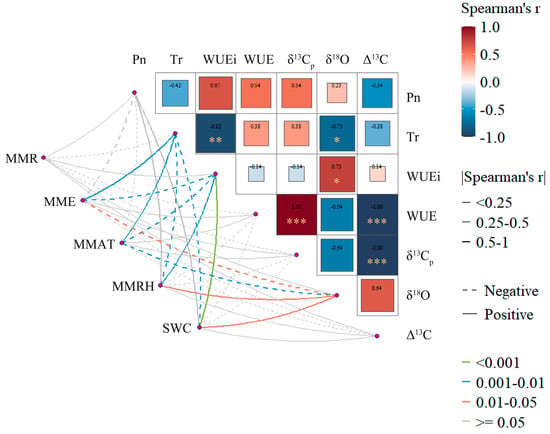

This study elucidated multiscale regulatory mechanisms of shrub water-use strategies using Mantel correlations among meteorological factors, gas-exchange parameters, and carbon–oxygen isotopes (Figure 12). Leaf δ13Cp correlated positively with WUE, whereas Δ13C correlated negatively with WUE, collectively indicating that carbon-isotope fractionation integrates long-term variation in intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). According to the Farquhar model, enrichment in δ13Cp directly reflects a reduction in the Ci/Ca ratio during the growth peak season. These results indicate that the three shrubs achieved high WUE primarily via tighter stomatal regulation that lowered Ci/Ca, rather than via increased biochemical capacity [56]. The negative correlation between WUEi and Tr indicates that Tr is the dominant driver of short-term fluctuations in WUEi. The observed negative Pn–Tr correlation further supports this inference. Physiologically, the divergence between WUE and WUEi is clarified: δ13Cp integrates stomatal effects on CO2 supply, whereas WUEi reflects transient stomatal regulation of water loss under short-term environmental variation. δ18O correlated positively with WUEi and negatively with Tr, indirectly corroborating stomatal regulation of water-transport processes. These findings align with the conclusions in Section 4.3.

Figure 12.

Mantel-test correlations among meteorological factors, plant photosynthetic parameters, and carbon−oxygen isotopes. The size and labels of the squares, together with the line colors, represent Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Asterisks denote significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05. Dotted lines indicate negative correlations, whereas solid lines indicate positive correlations.

Analysis of environmental drivers further clarifies the mechanisms above. The positive SWC−WUEi correlation indicates that sufficient soil moisture supports maintaining high Pn. The negative MMAT−WUEi correlation suggests that, at comparable moisture, higher temperature elevates vapor-pressure deficit (VPD), inducing partial stomatal closure and reducing water loss [61]. MMRH correlates positively with WUEi and negatively with Tr, indicating that atmospheric humidity modulates VPD and thereby contributes to multiscale regulation of water-use efficiency. Together, month-to-month increases in SWC, decreases in MMAT, and rises in MMRH underpinned the July–September increases in WUE and WUEi across the study area. Among these drivers, SWC was dominant, whereas MMAT and MMRH acted as short-term modulators that amplified or dampened the effects of stomatal regulation on carbon balance and water-use.

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study jointly measured leaf gas-exchange parameters, leaf δ13Cp, and δ18O of stem water and soil water, and related these indicators to key environmental drivers, thereby robustly discriminating the water-use strategies of three xerophytic shrubs. This integrative approach overcomes single-indicator bias and provides a rigorous basis for interpreting the physiological and ecological mechanisms underlying shrub adaptation to arid environments. Nevertheless, several limitations remain: sampling was confined to a single growth peak season. While this captures strategy contrasts during a critical window, it does not encompass interannual climate variability or responses across phenological stages. In addition, we did not directly quantify key physiological signals and metabolites, including abscisic acid (ABA), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and proline, thereby limiting inference on the proximal regulation of stomata and osmotic adjustment. Future work should expand the indicator set and implement long-term in situ, fixed-site observations in the study area to assess generalizability, deepen mechanistic understanding of strategy formation from physiological and biochemical perspectives, improve the predictive skill of vegetation models, and inform climate-adaptive species selection for ecological restoration.

5. Conclusions

Focusing on the northern edge of the Mu Us Sandy Land, this study investigates three typical xerophytic shrubs—Caragana microphylla, Salix psammophila, and Artemisia ordosica. During the growth peak season, we quantified gas-exchange fluxes (Pn, Tr), leaf δ13Cp, and δ18O of stem and soil water, and evaluated their coupling with hydrometeorological (water–heat) factors. Our objective is to resolve the mechanistic basis of shrub water-use efficiency under divergent water-use strategies, guiding the optimization of species composition and selecting vegetation-restoration models in arid and semi-arid regions. The conclusion is as follows:

- (1)

- During the growth peak season (July–September), Pn increased month by month across all three desert shrubs, whereas Tr decreased. Both WUE and WUEi showed overall upward trends. Leaf δ13Cp was significantly positively correlated with WUE, whereas Δ13C was significantly negatively correlated with WUE. Stem-water δ18O was significantly positively correlated with WUEi and significantly negatively correlated with Tr. Together, these patterns indicate that δ13Cp and δ18O effectively diagnose the regulation of shrub water-use efficiency via Ci/Ca dynamics and water-transport pathways.

- (2)

- Three shrub species show significant differences in water source utilization and drought resistance strategies: Caragana microphylla relies on stable deep-water sources and, via efficient stomatal regulation, maintains the highest and most stable WUE and WUEi, exemplifying a conservative water-use strategy. Salix psammophila is highly responsive to precipitation pulses, rapidly elevating Pn and exploiting newly recharged water across the soil profile during wet periods, consistent with an opportunistic water-use strategy. Artemisia ordosica depends long-term on evaporatively enriched shallow-water sources, exhibits low average WUE, and shows persistently enriched stem-water δ18O during late-drought stages, revealing drought vulnerability driven by shallow rooting and passive stomatal regulation.

- (3)

- The combined influence of meteorological factors governs the temporal dynamics of shrub water-use strategies. SWC shows a significant positive correlation with WUEi. MMAT is significantly negatively correlated, whereas MMRH is significantly positively correlated with WUEi, indicating that temperature and atmospheric humidity modulate water-use efficiency over short timescales by regulating VPD and stomatal conductance, thereby underpinning the month-to-month increase in WUE and WUEi from July to September.

This study demonstrates that shrub water-use strategies in sandy regions form a complementary portfolio of conservative, opportunistic, and vulnerable types rather than a random assemblage. This conclusion provides guidance for species selection and configuration in ecological restoration in arid areas, prioritizing conservative species with high water use efficiency and reliable access to deep water sources as the foundation. It judiciously combines opportunistic species that respond rapidly to precipitation pulses and deploys shallow-water-dependent, drought-vulnerable species with caution. Such a combination is expected to enhance the efficiency of large-scale water use in arid regions and strengthen the stability of ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z. and L.Y.; methodology, E.Z. and Z.M.; software, E.Z. and Z.S.; validation, Z.M., L.Y. and E.Z.; formal analysis, E.Z.; investigation, E.Z.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.Z.; visualization, Z.S. and N.W.; supervision, P.Z.; project administration, N.W.; funding acquisition, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF1306300); Scientific Research Service of Mu Us Sandy Land Development and Management Research Center, Forestry and Grassland Bureau of Wushen Banner (ESZCWSS-C-F-240085).

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to all the partners who participated in this study and the research platform provided by the Science and Technology Innovation Center of Forestry and Grassland. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their help and constructive comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MMR | Monthly mean rainfall |

| MME | Monthly mean evaporation |

| MMAT | Mean air temperature |

| MMRH | Mean relative humidity |

| SWC | Soil-water content |

| Pn | Net photosynthetic rate |

| Tr | Transpiration rate |

| WUE | Long water use efficiency |

| WUEi | Instantaneous water use efficiency |

| C | Stable carbon-isotope fractionation in plant leaves |

| δ13Cp | Plant leaf carbon-isotope ratio |

| δ18O | Oxygen-isotope ratio of water from plant stems and soils |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| Ci | Intercellular CO2 concentration |

| Ca | Atmospheric CO2 concentration |

| VPD | Vapor pressure deficit |

References

- Ding, D.; Jia, W.X.; Ma, X.G.; Wang, J. Water Source of Dominant Plants of the Subalpine Shrubland in the Qilian Mountains, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.J.; Ma, Q.; Yang, J.L.; Li, X.W.; Yang, J.; Liang, Y.L.; Li, J.Y. Characteristics of Soil Seed Banks and Their Influencing Factors in Ephedra rhytidosperma Communities at Different Altitudes on the Eastern Foothills of Helan Mountain, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.P. Review of the Ecohydrological Processes and Feedback Mechanisms Controlling Sand-Binding Vegetation Systems in Sandy Desert Regions of China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.Y.; Wu, Y.S.; Chen, X.H.; Feng, J.; Lu, L.Y.; Chasina, W.; Wang, C.Y.; Meng, Y.F.; Yin, Q. Spatial-Temporal Variation of Water Use Efficiency in Three Species of Sand-Fixing Shrubs on the Ordos Plateau. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 48, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Wang, J.D.; Zhang, M.J.; Qin, J.W.; Jin, W.X.; Zhang, S.L. Water Use Sources and Their Hydrological Niche Characteristics of Three Typical Plants in the South Slope of Qinling Mountains. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 45, 3946–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. The Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of Water Use Efficiency at Multiple Scales in Plantation Forests of Loess Hilly Regions. Doctoral Dissertation, Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.B.; Zhang, M.J.; Che, C.W.; Liu, Z.S.; Zhong, X.F.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y. Water Utilization Strategy of Ziziphus jujuba under Different Sand Cover Thicknesses Based on Stable Isotope Tracing. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 48, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.P. Research on the Influence of Nutrient Branch Number Based on Real-Time Stem Flow and Water Potential on Transpiration and Quality of Cut Rose Flowers. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Agricultural University, Kunming, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.J.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.G.; Lü, Y.M.; Yuan, R.F.; Gui, J. Characteristics of Stable Isotopes and Analysis of Water Vapor Sources of Precipitation at the Northern Slope of the Qilian Mountains. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 40, 5272–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Feng, T.J.; Xiao, H.J.; Xian, Z.M.; Liu, H.X.; Sun, Y.B.; Liu, Y.C. Study on the Moisture Source of Maize under the Configuration Structure of Different Farmland Shelterbelts. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2023, 37, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.L.; Xia, X.; Hu, D.Y.; Xiao, W.H.; Zhang, W.P.; Xu, Y.J.; Wu, Y.J. Quantifying the Water Sources of Camellia Oleifera during Fruit Growth Peak Period Using Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, L.H.; Yang, Z.Y.; Li, S.K.; Fan, M.Y.; Yang, S. Characteristics of Water Uses of Trees in Plantations with Different Configuration Patterns in Xining City. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 6390–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Han, L.; Wang, N.N.; Zhou, p.; Ma, Y.L.; Ma, J. Water Use Strategies of Caragana korshinskii and Populus bolleana in Pure and Mixed Plantations in the Eastern Sandy Land of the Yellow River in Ningxia. For. Sci. 2024, 60, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.Y.; Zhang, X.; Xia, J.Q.; Liu, H.Y.; Xu, J.; Xiong, X.J.; Yang, Y. Variations of Water, Carbon Isotopic Characteristics and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency of Vegetation in the Typical Beach Wetland of Lake Poyang. J. Lake Sci. 2024, 36, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.J.; Xu, Q.; Gao, D.Q.; Zhang, B.B.; He, D.M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, L. Response of Soil Water to Precipitation in Freshwater Wetland Forests in Lixiahe of Jiangsu Province. Terrest. Ecosyst. Conserv. 2023, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, A.A.; Stern, L.A. Seasonal Water Use Patterns of Juniperus ashei on the Edwards Plateau, Texas, Based on Stable Isotopes in Water. J. Hydrol. 2007, 342, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.Q.; Liu, Z.M.; Qian, J.Q.; Ala, M.S.; Zhang, F.L.; Peng, X.H. Water Sources of Dominant Sand-Binding Plants in Dry Season in Southern Horqin Sandy Land, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 28, 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.X.; Jia, D.B.; Gao, R.Z.; Lu, J.P.; Lu, F.Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F. Water Use Characteristics of Artificial Sand-Fixing Vegetation on the Southern Edge of Hunshandake Sandy Land, Inner Mongolia, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Xu, H.L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, X.F.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, Q.Q. Response of 15N Isotope in Plant to Water Change in Desert Grassland. Arid Zone Res. 2012, 29, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, A.D.B.; Ferguson, J.N.; Pignon, C.P.; Wu, A.; Jin, Z.; Hammer, G.L.; Lobell, D.B. Water Use Efficiency as a Constraint and Target for Improving the Resilience and Productivity of C3 and C4 Crops. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 781–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Zhao, X.N.; Gao, X.D.; Yu, L.Y. Difference of Water Use Efficiency between Ecological and Economic Forest and Its Response to Environment Using Carbon Isotope in the Loess Plateau of China. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.J.; Wang, X.G.; Zhang, Y.C.; Xie, C.; Liu, Q.Y.; Meng, F. Plant Water Use Strategies in the Shapotou Artificial Sand-Fixed Vegetation of the Southeastern Margin of the Tengger Desert, Northwestern China. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, I.H.; Poulton, P.R.; Auerswald, K.; Schnyder, H. Intrinsic Water—Use Efficiency of Temperate Seminatural Grassland Has Increased since 1857: An Analysis of Carbon Isotope Discrimination of Herbage from the Park Grass Experiment. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2010, 16, 1531–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanović, J.; Nepovimova, E.; Natić, M.; Kuča, K.; Jaćević, V. The Significance of Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense System in Plants: A Concise Overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 552969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Rejeb, K.; Abdelly, C.; Savouré, A. How Reactive Oxygen Species and Proline Face Stress Together. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, X.-P.; Gao, H.-J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.-P.; Shao, K.-Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.-L. Dynamic Responses of Haloxylon ammodendron to Various Degrees of Simulated Drought Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lv, G. Responses of Calligonum leucocladum to Prolonged Drought Stress through Antioxidant System Activation, Soluble Sugar Accumulation, and Maintaining Photosynthetic Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Lv, G. Nitraria sibirica Adapts to Long-Term Soil Water Deficit by Reducing Photosynthesis, Stimulating Antioxidant Systems, and Accumulating Osmoregulators. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, X.Y.; Jianxing, L.I.; Tao, W.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Guo, Y.L.; Lu, S.H.; Li, X.K.; Huang, P.Z. Water Use Efficiency of Dominant Tree Species during Natural Restoration of Vegetation in Karst Peak-Cluster Depression. J. Appl. Ecol. 2025, 36, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhao, J.Y.; Yang, R.X.; Yang, Y.Q. Water use efficiency of pioneer tree species in reclamation ecosystem of open-pit coal mine in loess hilly region. Arid Land Geogr. 2025, 48, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.Y.; Liu, Z.L.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.Z. Analysis on Plant Community Organization of Inner Mongolia Steppe. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2002, 16, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Xu, G.Q.; Mi, X.J.; Chen, T.Q.; Li, Y. Effects of Groundwater Depth and Seasonal Drought on the Physiology and Growth of Haloxylon ammodendron at the Southern Edge of Gurbantonggut Desert. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 8881–8891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Xu, G.Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Mi, X.J. Difference and Consistency of Responses of Five Sandy Shrubs to Changes in Groundwater Level in the Hailiutu River Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin 2021, 41, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.W.; Liu, J.J.; Sun, J.H.; Li, Y.F. Study on Root Distribution of Artemisa ordosica in Mu Us Sandy Land. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 17, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.Z. Growth and Physiological Response to Soil Water Change of Two Native Species in Loess Hilly-Gully Region Under Intercropping. Doctoral Dissertation, Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Xianyang, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zha, T.S.; Jia, X.; Bourque, C.P.-A.; Liu, P.; Jin, C.; Jiang, X.Y.; Li, X.H.; Wei, N.N.; et al. Dynamic Changes in Plant Resource Use Efficiencies and Their Primary Influence Mechanisms in a Typical Desert Shrub Community. Forests 2021, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, M.; Liu, X.Q. Simulation of Transpiration for Typical Xeromorphic Plants in Inland Arid Region of Northwestern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 7751–7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.S. Effect of Rainfall Pulses on Plant Growth and Transpiration of Two Xerophytic Shrubs in a Revegetated Desert Area: Tengger Desert, China. Catena 2016, 137, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.J.; Gong, J.R.; Zhai, Z.W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Shi, J.Y.; Zhang, W.Y.; Song, L.Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.Q. Response of the photosynthetic physiological characteristics to nitrogen addition of Stipa grandis leaves in a temperate grassland of the Inner Mongolia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 5994–6004. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=z8lpvlhA63GwsRyzpvhauj4IUqEjSg85WWeOjvbj5l2FT0o2YX5-yCXBpqMVH1G5xYzA8hJbNJ_1YVq-G8gnAKZm7h4oRAE5JuOgTVWr9JvvUTEUCxHqZeCiJO4e6yFdOeV-p8ZULIZGki3fGpjmHOlvhYhmxp4LmOHPziv7V1gV6fpvkiQ6zg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Liu, L.M.; Qi, H.; Luo, X.L.; Zhang, X. Coordination Effect between Vapor Water Loss through Plant Stomata and Liquid Water Supply in Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Continuum (SPAC): A Review. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008, 19, 2067–2073. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=z8lpvlhA63F9B5jyp1nMlUQyLNkyV1yU1W0KpwemHJ67ttglqDGyne4EnHOyo2bFSr6hR6D79CZVRzLwmoAqsJPA2iYsk565ux9w9p506_ODM9b3sK_Lx2A-h6NrStv33ZwzhpSHaAO3SeVYfcnh8dsO62AHezpBwIFHO1HOndpKyVZCDHUh_Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Huang, Y.R.; Ma, Y.B.; Hao, X.T.; Han, C.X.; Cui, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Pang, J.C.; Xu, G.F. The Impact of Different Stubble Heights on the Photosynthetic Characteristics and Water Use Efficiency of the Sand-Fixing Plant Haloxylon ammodendron. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2025, 53, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.T.; Hai, L.; Cao, W.X.; Li, X.; Li, Q.H. Effects of Caragana microphylla on Vegetation and Soil in the Restoration of Desertified Grasslands. Arid Zone Res. 2024, 41, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Q.; Zhu, Y.J.; Ma, Y.; Lin, F.C.; Liu, H.Y.; Li, X. Difference of Water Source of Two Ammopiptanthus mongolicus Communities in Ulan Buh Desert, China. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 1762–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.L. Evaluation and Optimization of a Model for Estimating Water Use Efficiency of Maize Cropland by Sunlight-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Master’s Thesis, Ningxia University, Yinchuan, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Z.; Sun, L.J.; Cha, X.F.; Guo, H.X.; Zeng, H.P.; Dong, Q. Effect of Simulated Patterns of Precipitation on the Growth and Photosynthetic Physiological Characteristics of Cyphomandra betacea Seedlings. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2025, 40, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J. Effects of Climate Warming on Photosynthetic Capacity and Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Larix gmelinii Needles Based on a Latitudinal Transplant Experiment. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.L.; Peng, Z.D.; L, X. Effects of soil moisture conditions on the leaf functional traits and the growth potential of Robinia pseudoacacia seedlings. J. Anhui Agric. Univ. 2025, 52, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Shi, H. Vulnerability to Drought-Induced Cavitation in Shoots of Two Typical Shrubs in the Southern Mu Us Sandy Land, China. J. Arid Land 2016, 8, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Ji, X.; Zhao, W.Y. Review of Research Advances and Future Perspectives of Modeling Stomatal Conductance of Plants Under Drought Stress. Adv. Earth Sci. 2025, 40, 877–889. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Zhou, M.C.; Hu, Z.Q.; Wu, Z.J.; Zhang, K.; Dong, L.Q. Response of stomatal and photosynthetic traits of Carex muliensis in the Ruoergai Alpine Marsh to water table drawdown. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 4405–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-C.; Gao, Y.-B.; Guo, H.-Y.; Wang, J.-L.; Wu, J.-B.; Xu, J.-S. Physiological Adaptations of Four Dominant Caragana Species in the Desert Region of the Inner Mongolia Plateau. J. Arid Environ. 2008, 72, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinning, S.; Ehleringer, J.R. Water Use Trade-offs and Optimal Adaptations to Pulse-driven Arid Ecosystems. J. Ecol. 2001, 89, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, L.; Wenninger, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, G.; Zhang, E.; Uhlenbrook, S. Climatic Controls on Sap Flow Dynamics and Used Water Sources of Salix psammophila in a Semi-Arid Environment in Northwest China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, Z. Stable Isotopic Analysis on Water Utilization of Two Xerophytic Shrubs in a Revegetated Desert Area: Tengger Desert, China. Water 2015, 7, 1030–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-Z.; Yang, X.-L.; Xu, Y.-S.; Feng, Z.-Z. Response of Key Parameters of Leaf Photosynthetic Models to Increased Ozone Concentration in Four Common Trees. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 46, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.; O’Leary, M.; Berry, J. On the Relationship between Carbon Isotope Discrimination and the Intercellular Carbon Dioxide Concentration in Leaves. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1982, 9, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.X.; Niu, X.W.; Akeyedeli, J.; Marhaba, A.; Rizwangul, H.; Lan, H.Y.; Cao, J. Overexpression of SaPEPC2 in tobacco results in stronger drought resistance and higher photosynthesis efficiency compared to non-transgenic plants. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2024, 59, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wen, X.; Lyu, S.; Guo, Q. Transition in Multi-Dimensional Leaf Traits and Their Controls on Water Use Strategies of Co-Occurring Species along a Soil Limiting-Resource Gradient. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 128, 107838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Knighton, J.; Evaristo, J.; Wassen, M. Contrasting Adaptive Strategies by Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila in a Semiarid Revegetated Ecosystem. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 300, 108323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.D.; Wo, X.T.; Diao, Y.F. Water Sources of Taxus cuspidata Based on Stable Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes Technique. For. Eng. 2025, 41, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernusak, L.A.; Ubierna, N.; Winter, K.; Holtum, J.A.M.; Marshall, J.D.; Farquhar, G.D. Environmental and Physiological Determinants of Carbon Isotope Discrimination in Terrestrial Plants. New Phytol. 2013, 200, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).