Abstract

To achieve sustainable agriculture development in arid regions, it is imperative to improve the soil quality of arid sandy soils. This study explored the effects of the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with soil conditioners on the physiological characteristics, yield, and quality of rapeseed in arid sandy lands. The aim was to provide a technical reference for improving sandy soil and increasing rapeseed yield in arid regions. This field study designed six treatments (control group: organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer (CK); T1: organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer + super absorbent polymer (SAP); T2: organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer + humic acid (PI); T3: organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer + attapulgite (PII); T4: organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer + PI + PII; HF: chemical fertilizer) to evaluate their effects on the nutrient absorption, physiological characteristics, yield, and quality of rapeseed. The results showed that the combination of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP, PI, PII, or PI + PII could significantly reduce the salinity of sandy soil while increasing the nutrient content in various parts of rapeseed. Among the combinations, the SAP treatment (T1) had the most significant effect, with the following specific impacts: (1) Alleviation of salt stress: The SAP treatment increased the root potassium ion content by 63.09% and reduced sodium ion content by 60.16% compared with CK, significantly increasing the potassium/sodium ratio. (2) Physiological improvement: The SAP treatment increased the total chlorophyll content (TCC), superoxide dismutase/catalase activity, and dry matter accumulation by 86.85%, 161.58%, and 376.8%, respectively, compared with CK. (3) Yield and quality enhancement: The SAP treatment increased rapeseed yield and the crude protein content in stems and leaves by 148.32% and 86.05%, respectively, but decreased crude fiber content by 43.59% compared with CK. (4) Economic benefits: The net revenue (NR) of the SAP treatment reached 197.62 USD per hectare, which was significantly higher than that of other treatments. A comprehensive evaluation showed that the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP enhanced plant antioxidant enzyme activity and photosynthetic efficiency, synergistically enhancing the yield and quality of rapeseed in sandy areas. This study provides an economically efficient solution for sustainable agricultural development in arid regions.

1. Introduction

Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) is an important raw material for edible oil and feed. China is the world’s largest producer of rapeseed, with a global share of nearly 40%. In 2023, China’s total rapeseed production reached 16.3174 million tons (China National Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Xinjiang is located in the hinterland of the Eurasian continent, with a wide range and a large area of deserts. In recent years, the rapeseed planting area in Xinjiang, China, has steadily increased. However, the area of salinized land in Xinjiang reaches 74.6821 million hectares [1]. Soil salinization and the frequent occurrence of extreme weather events such as drought have led to a significant yield reduction (approximately 3.5 million tons) in cereal crops (about 8%) [2] and forage in Xinjiang, exacerbating the shortage of forage. The lack of forage limits the development of animal husbandry. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop efficient, low-consumption, and sustainable soil improvement and agronomic measures to mitigate the adverse effects of environmental changes on forage crop production [3,4]. In arid areas, improving salinized soils is crucial for enhancing agricultural productivity and promoting sustainable agricultural development.

Soil conditioners and fertilizer nutrients can enhance crop response to abiotic stresses [5,6]. Compared with starch and potassium soil conditioners, Super Absorbent Polymer (SAP) is more effective in alleviating stresses in crops, showing significant economic and environmental advantages [7]. SAP is a high-molecular-weight polymer with low cross-linking density, low solubility, and high water-adsorption and swelling ability. It is widely used as a soil conditioner in agricultural fields [8]. The chain structure of SAP can improve the adhesion between easily dispersed particles (1–100 nm) [9]. In addition, SAP can promote the formation of large aggregates in soil and increase soil moisture content, pH, electrical conductivity, and bulk density. This can alleviate the negative effects of drought and salt stresses on crop growth and increase crop yield. Notably, SAP achieves better results when combined with organic fertilizers [10]. However, its yield-increasing effect depends on the SAP application time and the strength of crop nutrient requirements, as well as soil microbial and climatic conditions [11]. While SAP provides notable benefits in enhancing soil properties, it may also pose adverse effects on the natural environment. Its components are safe under appropriate use. However, excessive use (especially polyacrylamide) can lead to health risks. Extended exposure may lead to skin allergies, respiratory irritation, and liver or kidney damage [12]. In addition, excessive use of SAP may also lead to environmental pollution. For example, xylene emissions generated during its production process can contaminate water and soil, disrupting ecosystems [13]. Therefore, the dosage should be determined based on specific environmental conditions [13,14].

At present, the research on improving desertified lands in Xinjiang, China, mostly focuses on water-saving irrigation, sand fixation, and farmland shelterbelts [15]. A few studies are exploring the comprehensive (physiological and economic) benefits of soil improvement using SAP on crop yield and quality [16,17]. The synergistic interaction between the soil ecosystem and crop root nutrient absorption and transport is crucial for crop growth and yield formation [18,19,20]. Soil physicochemical properties, microbial activity, and nutrient accumulation can directly reflect the effects of SAP on crop growth [21,22,23]. In addition, the comprehensive evaluation based on multiple indicators can reveal the effects of SAP and avoid the bias of human evaluation, providing an objective reference for sandy soil improvement and rapeseed yield increase.

In this field experiment in Hotan, Xinjiang, China, the effects of the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with soil conditioners on the nutrients of various organs, leaf photosynthesis, enzyme activity, yield, and quality of rapeseed in sandy land were evaluated. The aim was to investigate whether the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with conditioners could reduce drought stress and increase rapeseed yield. At the same time, the optimal rapeseed planting strategy in arid and desertified regions using the combination of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP was proposed. The research results will contribute to the improvement of desertified land and the enhancement of the growth and yield of rapeseed in arid areas. This study, different from previous research on single soil conditioners [24], not only broadens the scope of research but also introduces innovations in materials, soil improvement methods, and a novel planting system for rapeseed in arid regions, offering new insights for the enhancement of arid sandy soils. The study results provide important references for sustainable agricultural development and dryland planting management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The field experiment was conducted at Pishan Farm in Hotan, Xinjiang, China (37°13′35.2″ N, 77°47′38.9″ E) (Figure 1b). The soil in the experimental site is desertified soil (Figure 1a). Before the experiment, topsoil (0–20 cm) was collected, and its properties were measured (Table 1). This region has a temperate continental climate, with an average temperature of 11.9 °C, an annual sunshine hours of 2466.8 h, a frost-free period of 190–205 days, an annual average precipitation of 48.2 mm, and an annual average evaporation of 2450 mm.

Figure 1.

The aerial photo (a) and coordinates (b) of the experimental site.

Table 1.

Soil properties of the experimental site (0–20 cm soil layer).

2.2. Experimental Design

Super Absorbent Polymer (SAP) is a high-molecular compound primarily composed of polyacrylamide (a white, high-molecular-weight, and water-soluble powder with strong heat resistance), humic acid (a weakly acidic and organic macromolecular mixture in a black colloidal form), and attapulgite (an alkaline and gray-white block with a density of 2.0–2.3 g/cm3). The SAP was synthesized via aqueous solution-based polymerization. All the materials were obtained from Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

The rapeseed variety used in this experiment was Huayouza 62. To determine the optimal application rate of SAP, a field pre-test was conducted in April 2021. The experimental design were as follows: organic fertilizer (18 t·hm−2) + chemical fertilizer (N: 180 kg·hm−2, P: 120 kg·hm−2, K: 105 kg·hm−2) + different concentrations of SAP (0% SAP (CK), 0.25% SAP (1.5 t·hm−2), 0.5% SAP (3 t·hm−2), and 1% SAP (6 t·hm−2)). According to the comprehensive analysis of the first cut, among the above treatments, the 1% SAP (6 t·hm−2) treatment had the most significant increase in soil water and fertilizer retention capacity and microbial diversity indices and abundance, as well as the most significant alleviation of soil salt damage compared with CK. Therefore, organic fertilizer + chemical fertilizer + 1% SAP (6 t·hm−2) was the optimal combination.

This experiment employed a randomized block design. The specific experimental design is detailed in Table 2. There was a total of six treatments. Each treatment has three replicates. The width of each plot was 6 m, and the length was 10 m. After thoroughly mixing organic and chemical fertilizers with conditioners according to the experimental design, they were applied to the soil on 10 August 2021, followed by tilling using a rotary tiller (depth: 5–10 cm). Rapeseed seeds were sown on August 15. The plant spacing was 20 cm, and the row spacing was 50 cm. An embankment with a width of 0.45 m was built between plots. Relevant indicators were measured on the 15th, 30th, 45th, and 60th day after emergence.

Table 2.

Application rates of organic and inorganic fertilizers and soil conditioners under different treatments.

On the day after sowing, all plots were irrigated with the same amount of water (45 mm) to promote seed germination. According to local production practices, irrigation was not carried out from the emergence of rapeseed to the canopy rapid growth stage (0–45 days). Irrigation was carried out at the seedling (on the 45th day), budding, flowering, and ripening stage, and ended three weeks before harvest, with a total irrigation amount of 4000 m3/hm2. Other field management measures were consistent with local practices.

2.3. Determination of Plant Nutrient Content

On the 15th, 30th, 45th, and 60th day after emergence, three rapeseed plants with fully unfolded leaves were selected from each plot. The total nitrogen content of plants (roots, stems, leaves) was determined using the Kjeldahl method. According to the phosphorus content determination method of Deng et al. [25], the absorbance was determined at 440 nm using a UV-1900i spectrophotometer (Shimadzu (China) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), followed by the calculation of the total phosphorus content based on the absorbance values and the standard curve. The K+ and Na+ contents of plants were determined using flame photometry [26].

2.4. Determination of Chlorophyll Content

To investigate the physiological response of rapeseed to SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII, five leaf samples were randomly selected from each plot. Chlorophyll pigments were extracted from frozen mature leaf samples, and analyzed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer UV-1900i (Shimadzu (China) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 665, 649, and 453 nm [27,28].

2.5. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

The superoxide (SOD) activity was determined according to the method of Safavi et al. [29], based on the ability of SOD to inhibit nitro-blue tetrazolium (NBT) photochemical reduction at 560 nm. The POD activity was analyzed according to the method of Safavi et al. [29], based on the ability of POD to oxidize orthomethoxyphenol to 4-orthomethoxyphenol with hydrogen peroxide at 470 nm.

2.6. Determination of Dry Matter Accumulation (DMA)

Five plants were randomly selected from each plot, and their roots, stems, and leaves were dried in an oven (DHG-9030A, Jinghong Laboratory Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 105 °C for 30 min. Then, the sample was dried at 85 °C until a constant weight. Finally, DMA was calculated according to the method of Feng et al. [30].

2.7. Determination of Yield, Quality, and Net Revenue (NR)

During the harvest period, 3 m2 of rapeseed were harvested from each plot. Rapeseed grains were collected and weighed, followed by the calculation of total yield using formula (1) [31]. The content of crude protein (CP), crude ether extract (CEE), and crude fiber (CF) in the stems and leaves was determined. The content of CP was directly calculated based on formula (2) [32]. The content of CEE was determined using the Soxhlet extraction method, and that of CF was determined using the method of Liu et al. [33].

Net revenue (NR, USD ha−1) was calculated using Formulas (3) and (4) based on total revenue (TR, USD ha−1), agronomic costs (AC, USD ha−1), and other costs (OC, USD ha−1).

where TR represents total revenue, calculated by multiplying the two-cut yield (TY, t ha−1) by the price of the year (Tprice, USD t−1) (the price in 2021 was 1520 USD t−1). AC represents agronomic costs, including expenses for purchasing organic, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium fertilizers, soil conditioners, irrigation water, seeds, and pesticides. OC represents other costs, including machinery usage costs (pre-sowing plowing, intercropping), fuel costs (for water pumps), land rent, and labor costs.

2.8. Model Description and Application

Entropy Weight Method (EWM) is an objective assignment method used to reduce bias caused by subjective assignment and determine the weights of indicators. TOPSIS is a multi-objective decision-making method that can identify the best solution from comparative studies of multiple options and objectives [34]. In this study, EWM was combined with TOPSIS (EWM-TOPSIS) to determine the optimal treatment that balanced the TY, Quality, TCC, and NR.

Firstly, a raw data matrix (X) was established for 6 treatments (xi, i = 1, 2, 3, …, n) and 4 evaluation metrics (xij = 1, 2, 3, …, m). Then, EWM was used to determine the weights of these indicators based on Formulas (5)–(9). Notably, the four evaluation indicators were all positive indicators (the larger the value, the better the outcomes). There is no need to perform inverse processing before calculating the weights [35,36].

where xij represents the value of the j-th evaluation index processed in the i-th step; bij is the ratio of the i-th evaluation objective to indicator j; ej is the entropy value of indicator j; Wj is the weight of indicator j.

Secondly, according to Formulas (10)–(13), the data were normalized to obtain the normalization matrix. The weighted matrix was obtained by multiplying the normalization matrix by the weights of each evaluation indicator. The positive and negative ideal solutions (Z+ and Z−) were determined using the weighted matrix.

Finally, based on formulas (14) and (15), the Euclidean distance (D+ and D−) and the relative closeness (Ci) of each indicator to the positive and negative ideal solutions were determined. The higher the Ci value, the better the effect. The treatments were sorted according to the Ci value.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Before analyzing the data, Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests were performed on the collected data using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). When the test results met p > 0.05, the data met the requirements of variance homogeneity and normality, indicating that subsequent analysis of variance could be conducted. In this study, SPSS 25.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), with days after emergence and conditioner treatments as fixed factors, and harvest as a random factor. Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare the significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05). In addition, the statistical data were visualized using Origin 2024 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). Redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted to elucidate the impact of each treatment on the nutrient content, leaf chlorophyll content (LCC), K+ content, Na+ content, yield, and quality of rapeseed.

3. Results

3.1. Root K+ and Na+ Content and K+/Na+ Ratio

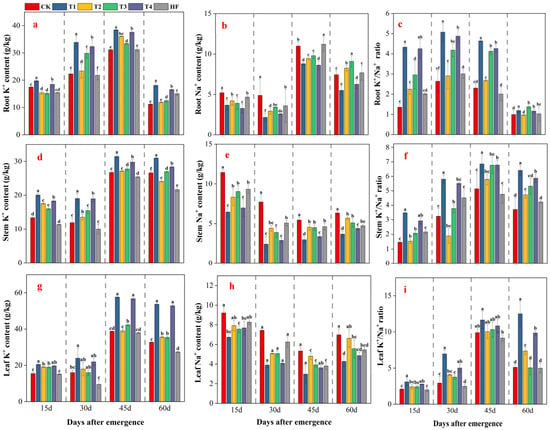

The combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP, PI, PII, or PI + PII all led to an increase in root K+ content and K+/Na+ ratio and a decrease in the root Na+ content compared with CK. On the 60th day, the root K+ content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 57.14% and 63.09% higher than that of CK, respectively (p < 0.05) (Figure 2a). The root Na+ content of the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments was lower than that of CK. Particularly, the Na+ content of the T1 treatment was 60.16% lower than that of CK (p < 0.05) on the 30th day (Figure 2b). The root K+/Na+ ratio of the conditioner treatments, particularly the T1 treatment (p < 0.05), was higher than that of CK (Figure 2c). Therefore, SAP had a stronger effect within 60 days compared to the other conditioners.

Figure 2.

Changes of potassium (K+) content, sodium (Na+) content, and K+/Na+ ratio in the roots (a–c), stems (d–f), and leaves (g–i) of rapeseed plants on day 15 (n = 3), 30 (n = 3), 45 (n = 3), and 60 (n = 3) under the treatments of various combinations of organic–inorganic fertilizers and soil conditioners. Lowercase letters denote significant differences in the K+, Na+ and K+/Na+ ratio among various soil conditioner application treatments (p < 0.05); there is no significant difference in parameters with the same letters.

3.2. Stem K+ and Na+ Content and K+/Na+ Ratio

The stem K+ content of the T1 treatment was 114.12% higher than that of CK on the 30th day (p < 0.05) (Figure 2d). Consequently, the K+/Na+ ratio of the T1 treatment was 468.15% higher than that of CK (p < 0.05). The effect of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments (Figure 2f) was weaker than that of the T1 treatment. Meanwhile, the stem Na+ content of all conditioner treatments was lower than that of CK within 60 days (Figure 2e).

3.3. Leaf K+ and Na+ Content and K+/Na+ Ratio

The leaf K+ content of the TI treatment was 6.99%, 49.56%, 45.29%, and 49.21% higher than that of CK at 15, 30, 45, and 60 days, respectively (Figure 2g), leading to a higher (48.45%, 138.69%, 12.75%, and 145.49%, respectively) leaf K+/Na+ ratio (Figure 2i). Simultaneously, despite a significantly higher K+ content and K+/Na+ ratio of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments, the effect of the T1 treatment was significantly stronger than that of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments (p < 0.05). Moreover, the leaf Na+ content of the conditioner treatments (Figure 2h) was significantly lower than that of CK within 60 days (p < 0.05).

3.4. Root Nutrient Content

On the 60th day, the nitrogen content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 268.18% and 254.55% higher than that of CK, respectively (Figure 3a), whereas the phosphorus content was 30.30% and 30.09% higher than that of CK, respectively (Figure 3b). Conversely, the nitrogen and phosphorus content of the T2 and T3 treatments was lower than that of CK over the 60 days. The effect of SAP on the nitrogen and phosphorus content in the roots (p < 0.05) was stronger than that of the PI, PII, and PI + PII. Additionally, the effect of PI + PII was stronger than that of PI and PII.

Figure 3.

The nitrogen and phosphorus content in the roots (a,b), stems (c,d), and leaves (e,f) of rapeseed at 15 (n = 3), 30 (n = 3), 45 (n = 3), and 60 (n = 3) days after emergence. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences in nutrient organs under different amendment application treatments (p < 0.05); there is no significant difference in parameters with the same letters.

3.5. Stem Nutrient Content

The stem nitrogen and phosphorus content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 80.85% and 68.09% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 60th day (p < 0.05) (Figure 3c). The stem phosphorus content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 18.83% and 15.23% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 45th day (p < 0.05) (Figure 3d). The stem nitrogen and phosphorus content of the TI treatment was significantly higher than that of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments (p < 0.05).

3.6. Leaf Nutrient Content

The leaf nitrogen and phosphorus content of the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments was significantly higher than that of CK. The effect of the T4 treatment was stronger than that of the T2 and T3 treatments, but was weaker than that of the T1 treatment (p < 0.05). The leaf nitrogen content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 28.30% and 25.37% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 45th day, and 103.23% and 87.90% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 60th day (Figure 3e). The leaf phosphorus content of the T1 and T4 treatments was 30.68% and 29.39% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 45th day, and 19.65% and 19.30% higher than that of CK, respectively, on the 60th day (Figure 3f).

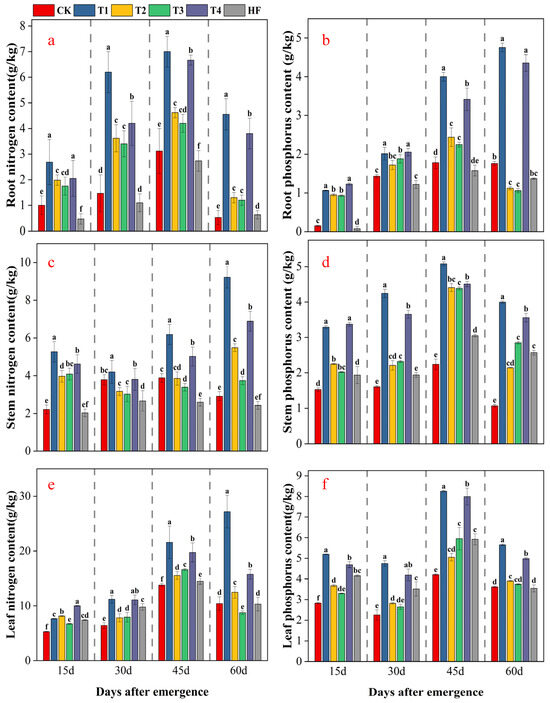

3.7. Chlorophyll Content

The leaf chlorophyll content of the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments was significantly higher than that of CK. SAP had the strongest effect, followed by PI + PII (Figure 4). The content of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), carotenoids, and total chlorophyll in the leaves of the T1 treatment was significantly higher than that of the T4 treatment at most growth stages (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Chlorophyll content in rapeseed leaves on different days after emergence. (a) Chlorophyll a (Chl a) content; (b) total chlorophyll content (TCC); (c) Chlorophyll b (Chl b) content; (d) Carotenoid content; (e) The overall trend of chlorophyll changes. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences in Chlorophyll content under different amendment application treatments (p < 0.05); there is no significant difference in parameters with the same letters.

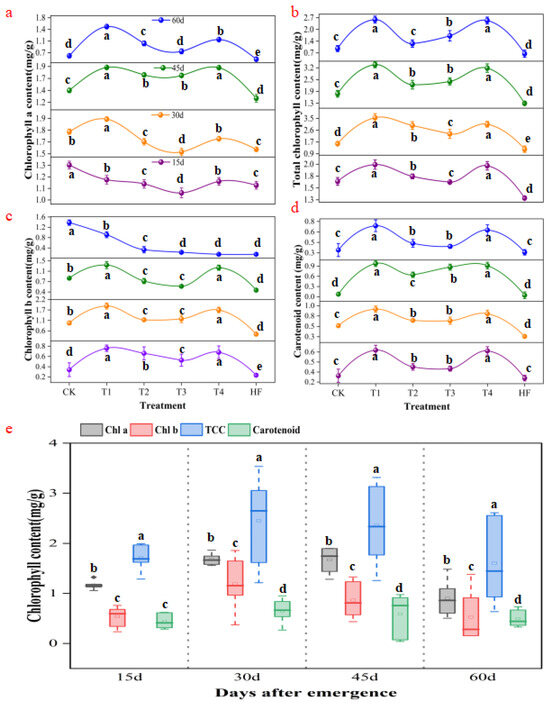

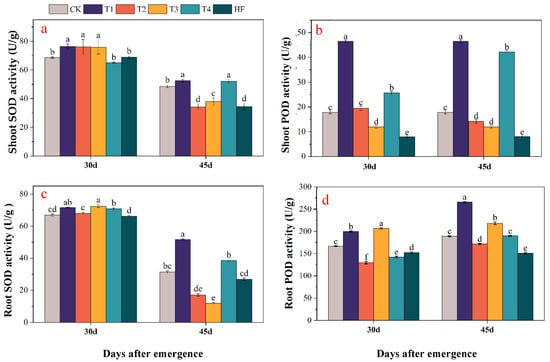

3.8. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) activities in the shoots and roots between the conditioner treatments (T1, T2, T3, T4) and CK on the 30th and 45th day (Figure 5). The activity of SOD and POD in the shoots and roots of the T1, T2, T3, and T4 treatments was higher than that of CK, with SAP (T1) showing the most significant effect (p < 0.05). The overall difference in SOD activity in the shoots and roots between the conditioner treatments and CK was small, with the root SOD activity of the T1 treatment 65.29% higher than that of CK on the 45th day. There was also a significant difference in POD activity in the shoots and roots between the conditioner treatments and CK (p < 0.05). The shoot POD activity of the T1 treatment was 161.56% and 161.58% higher than that of CK on the 30th and 45th day, respectively, and the root POD activity was 19.94% and 40.31% higher than that of CK, respectively.

Figure 5.

Superoxide (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) activities in the shoots and roots of rapeseed under different treatments.Note: (a) is shoot SOD; (b) is shoot POD; (c) is Root SOD; (d) is Root POD. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences in SOD/POD activity under different amendment application treatments (p < 0.05); there is no significant difference in parameters with the same letters.

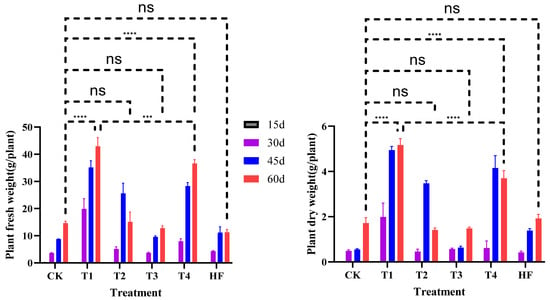

3.9. Fresh Weight and Dry Matter Accumulation

The application of SAP and PI + PII had a significant effect on the DMA and fresh weight (p < 0.0001). The fresh weight of the T1 treatment was 366.27% higher than that of CK on the 30th day, and the fresh weight of the T4 treatment was 152.83% higher than that of CK on the 45th day (Figure 6). The DMA of the T1 treatment was 376.8%, 258.21%, and 196.56% higher than that of CK on the 30th, 45th, and 60th day, respectively. The DMA of the T4 treatment was 151.69% and 93.04% higher than that of CK on the 45th and 60th day, respectively (p < 0.0001). In addition, the effect of the T1 treatment on the fresh weight and DMA of plants was stronger than that of the T2, T3, and T4 treatments.

Figure 6.

Fresh weight and dry matter accumulation of rapeseed under different treatments. ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; ns, insignificant difference; the error line only represents the error of each treatment.

3.10. Comprehensive Evaluation

The comprehensive evaluation of total yield (TY), Quality, TCC, and NR of rapeseed using EWM-TOPSIS (Table 3) showed that similar Ci (comparative index) and Rank values were obtained across two growing seasons. The T1 (SAP) treatment exhibited the highest Ci, as recommended by the model, followed by the T4 (PI + PII) treatment.

Table 3.

Comprehensive evaluation of total yield (TY), quality, total chlorophyll content, and net revenue of rapeseed using EWM-TOPSIS in two growing seasons.

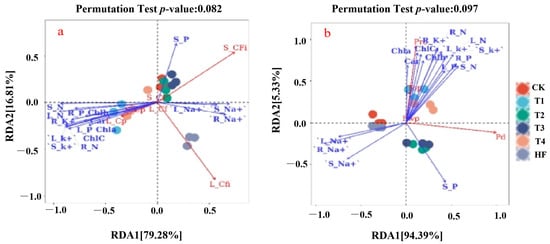

3.11. Redundancy Analysis of Yield and Quality

Leaf crude fiber was positively correlated with Na+ content in the roots, stems, and leaves, and negatively correlated with crude protein and fat content in the stems and leaves (Figure 7a). Stem fiber content was positively correlated with stem phosphorus content. The crude protein and fat content in the stems and leaves were positively correlated with root nitrogen, phosphorus, and K+ content, stem nitrogen and K+ content, and leaf nitrogen, phosphorus, K+, Chl a, Chl b, TCC, and carotenoids content. The T1 and T4 treatments were positively correlated with crude fat and crude protein content in the stems and leaves, while the HF treatment was positively correlated with leaf crude fiber content. In summary, Na+ content in the roots, stems, and leaves hindered the formation of crude fat and crude protein. The application of SAP and PI + PII enhanced the contents of nutrients, K+, and chlorophyll in rapeseed compared with CK, thereby promoting the synthesis of crude protein and crude fat.

Figure 7.

(a) RDA of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment content, K+ content, Na+ content, and quality in different organs of rapeseed. (b) RDA of nutrient content, photosynthetic pigment content, K+ content, Na+ content, and yield in different organs of rapeseed.

The content of Na+ in the roots, stems, and leaves was positively correlated with CK and HF treatments (Figure 7b). Stem phosphorus content was positively correlated with T2 and T3 treatments. Yield and fresh weight per plant were positively correlated with the content of root nitrogen, root phosphorus, root K+, stem nitrogen, stem K+, leaf nitrogen, leaf phosphorus, and leaf K+. The T1 and T2 treatments were positively correlated with yield and fresh weight per plant.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Combined Application of Organic–Inorganic Fertilizers with SAP Enhanced the Soil Environment, Rapeseed Leaf Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, and Plant Growth

The combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP enhanced soil nutrition content by reducing soil salinity, thereby fostering the growth of rapeseed. Rapeseed not only eliminates excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) by enhancing leaf SOD and POD activities under salt and drought stresses but also enhances osmotic potential by retaining soil water and fertilizers to prevent excessive water loss [37,38]. The application of SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII significantly enhanced soil physicochemical properties, plant nutrient content, and the activity of SOD and POD in rapeseed leaves under salt stress compared with CK, and SAP had the most significant effect. This may be attributed to the up-regulation of drought-resistant genes, cell stability [39,40,41], as well as related metabolic enzyme activity [42,43] induced by SAP.

4.2. The Combined Application of Organic–Inorganic Fertilizers with SAP Enhanced the Photosynthetic Capacity, Yield, and Quality of Rapeseed

The combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP positively affected the physiological characteristics of rapeseed. The application of SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII enhanced DMA by increasing the TCC in rapeseed leaves, with SAP having the most significant effect. The increase in TCC in plant leaves after SAP application may be linked to the increase in leaf nutrients and photosynthetic enzyme activity [44,45]. This increase allows plants to accumulate dry matter more efficiently [46,47], thereby enhancing the rapeseed yield. The increase in TCC may be due to the deposition of nutrient elements around the leaf cell wall after the application of SAP, which protects the cell membrane and inhibits the decrease in LCC [48,49]. In addition, increases in the activity of chlorophyll synthesis enzymes could also lead to an increase in LCC [38,50]. Both increases enable plant leaves to capture more light for photoassimilate production. With the growth of rapeseed, the application of SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII significantly increased plant biomass compared with CK, with SAP exhibiting the most pronounced effect. Therefore, the application of SAP is more effective in boosting the yield of rapeseed compared with PI, PII, and PI + PII. Notably, fresh rapeseed quality is vital for animal husbandry. SAP could significantly enhance the rapeseed quality by increasing crude protein content while reducing crude fiber content compared with CK [51,52]. It was found that the application of SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII increased the crude protein content in the stems and leaves by 65.98–70.10% and 86.05–86.85%, respectively, and decreased the crude fiber content by 22.21–43.59% and 12.37–18.86%, respectively. This aligns with the actual growth of the plants [53]. Among them, the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP demonstrated the best effect and significantly improved the quality of rapeseed.

4.3. The Combined Application of Organic–Inorganic Fertilizers with SAP Enhanced Nutrient Absorption in Rapeseed and Environmental Benefits

The mechanisms through which roots absorb and transport nutrient ions and subsequently plants maintain their concentrations in cell fluid are crucial for the survival of plants in sandy lands [54]. The combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP, PI, PII, or PI + PII could enhance the total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and total potassium (TK) content of rapeseed, with SAP exhibiting the most significant effect. This enhancement may be due to that SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII enhance soil adsorption and gas exchange capacity, accelerate shoot water consumption, and promote root extension into deeper soil layers [55]. It was also observed that the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP significantly increased the TY and NR of rapeseed compared with CK. The application of SAP, PI, PII, and PI + PII prevents economic losses by increasing crop TY. Moreover, the SAP treatment did not increase NR more than the PI + PII treatment. This may be due to the effectiveness of related polymer materials being limited. Consequently, future research can explore materials with superior effects to polyacrylamide, humic acid, and attapulgite for combined application with organic and chemical fertilizers. Notably, SAP is characterized by its non-toxicity to plants and the environment, high absorbability, and rapid transport within various plant organs [31]. However, long-term application of SAP may lead to soil compaction, reduce the soil’s ion exchange capacity, and inhibit microbial activity. It may also potentially accumulate in human bodies through the food chain, posing a risk to human health. Humic acid may alter the form of pollutants, increasing the migration risks. Attapulgite, as a mineral material, may cause the accumulation of non-degradable particles in the soil and disrupt the balance of the microbial community. Therefore, in practical applications, excessive use should be avoided to prevent negative environmental impacts [56,57,58]. This research on SAP as a novel soil conditioner offers a valuable strategy for mitigating abiotic stresses in crops.

4.4. Practical Application Potential and the Differences from Single Soil Conditioners

Water-saving irrigation projects and other measures were employed to mitigate drought stress in most arid regions in Xinjiang, China. SAP has demonstrated significant potential for conserving water, increasing crop yields, and improving soil quality in practical applications [59,60,61]. When SAP is integrated into actual farming practices, it can further enhance the quality of agriculture. Furthermore, the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP offered more benefits over single soil conditioners, with a clear distinction from the latter. This advantage likely stems from the ability of polymer materials to combine substances through physical or chemical means, thereby leveraging the strengths of each component and offsetting the limitations of individual materials [62,63]. Concurrently, the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP achieved rapeseed yield and quality enhancement. Given the high cost of polymer materials and the conditions of arid regions, it is imperative to further investigate the value of the proposed strategy in sustainable agriculture by incorporating precision agriculture technology in the future.

5. Conclusions

The combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP significantly enhanced the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium content in rapeseed compared with CK. Moreover, it also significantly reduced the adverse effects of soil salts. Compared with organic and inorganic fertilizers, this SAP-based approach improved the physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant mechanisms in rapeseed. Notably, 6 t·hm−2 was identified as the optimal SAP application rate. Field experiments demonstrated that the best combination based on local planting practices in sandy soil was 18 t·hm−2 of organic fertilizer (OF) + chemical fertilizers (N: 180 kg·hm−2; P: 120 kg·hm−2; K: 105 kg·hm−2) + 6 t·hm−2 of SAP. This regimen is recommended for improving sandy soil fertility and rapeseed growth. Furthermore, comprehensive evaluations of all treatments revealed that the combined application of organic–inorganic fertilizers with SAP was an environmentally sustainable and superior practice for enhancing rapeseed growth, yield, and quality in arid sandy lands, offering a novel solution for soil improvement. Taking cost into consideration, future research can explore more polymer materials for combined applications to further enhance economic and environmental benefits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization K.W. and H.F.; methodology K.W. and H.F.; software K.W. and H.F.; validation H.W. and M.L.; formal analysis. H.W. and M.L.; investigation. K.W. and H.F.; resources. H.W. and M.L.; data curation. H.W.; writing—original draft preparation. K.W. and H.F.; writing—review and editing. H.W. and M.L.; visualization: K.W. and H.F.; supervision. K.W. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Special Fund for Key Science & Technology Program of Xinjiang, China (No. 2022B02053-1), the Leading Science and Technology Project of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (2023ZD063), the Science and Technology Program of Shihezi City (2024BX03), the Research and Demonstration of Key Technologies for Soil Improvement and Ecological Prevention and Control in Desert Areas with Excessive Wind and Sand in Southern Xinjiang (2022ZY010) and the Science and Technology Plan Project of Huyanghe City (2025D07).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Pishan Farm in Xinjiang for providing climate data and to the staff of the farm for assisting in conducting field experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Liang, Z. Advances in the Application of Biochar for Saline-Alkali Soil Amelioration. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; Chen, G. Research Progress on the Effects of Biochar in Ameliorating Saline-Alkali Soils and Its Impact on Plant Growth. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 55, 551–561. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Guo, X. Effects of Shallow Buried Straw Interlayer on Water-Salt Transport and Tomato Growth in Coastal Saline Soil. J. Irrig. Drain. 2023, 42, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Wei, Z.; Yu, J.; Shi, J.; Wu, D. Study on the long-term effect of water-retaining agent on soil properties. J. Irrig. Drain. 2013, 32, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tarolli, P.; Luo, J.; Park, E.; Barcaccia, G.; Masin, R. Soil Salinization in Agriculture: Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies Combining Nature-Based Solutions and Bioengineering. iScience 2024, 27, 108830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K.; Kalbitz, K. Cycling downwards-dissolved organic matter in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 52, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaeil, P.; Habibi, D.; Boojar, M.M.A.; Tarighaleslami, M.; Khoshouei, S. Effects of superabsorbent application on agronomic characters of red bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars under drought stress conditions. Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 2012, 4, 1874–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Pouresmaeil, P.; Habibi, D.; Boojar, M.M.A.; Tarighaleslami, M.; Khoshouei, S. Effect of super absorbent polymer application on chemical and biochemical activities in red bean (Phaseolus volgaris L.) cultivars under drought stress. Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 3, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Mehraban, A.; Afrazeh, H. The effect of irrigation intervals and consumption of super absorbent polymers on yield and yield components of the local mung beans in Khash region. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2014, 8, 118–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E.M.; El-Tohamy, W.A.; El-Abagy, H.M.H.; Aggor, F.S.; Nada, S.S. Response of snap bean plants to super absorbent hydrogel treatments under drought stress conditions. Curr. Sci. Int. 2015, 4, 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrokhian, Z.; Mirzaei, F.; Heidari, A. Effects of super absorbent polymer on tomato’s yield under water stress conditions and its role in the maintenance and release of nitrate. World Rural. Obs. 2013, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Q.; Wang, S. Analysis and Exploration of Saline-Alkali Land Management Trends in China. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2020, 59, 302–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, A.M.; Ragavan, T.; Begam, S.N. Superabsorbent Polymers (SAPs) Hydrogel: Water Saving Technology for Increasing Agriculture Productivity in Drought Prone Areas: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2021, 42, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholinezhad, E.; Eyvazi, A.R. The effect of super absorbent polymer and manure fertilizer on water use efficiency of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars under different irrigation regimes. J. Crops Improv. 2019, 21, 275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. A Brief Analysis of Desertification in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Environ. Res. Monit. 2017, 18, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah, D.; Karak, N. Biodegradable superabsorbent hydrogel for water holding in soil and controlled-release fertilizer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, T.N.; Aruggoda, A.G.B.; Disanayaka, C.K.; Kulathunge, S. Evaluating the effects of different watering intervals and prepared soilless media incorporated with a best weight of super absorbent polymer (SAP) on growth of tomato. J. Eng. Technol. Open Univ. Sri Lanka (JET-OUSL) 2014, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Dong, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, M.; Cheng, M.; Ma, J. Research Progress on Soil Improvement and Resource Utilization of Coastal Saline-Alkali Land in China. World For. Res. 2020, 33, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Meng, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Chen, W. Effects of Straw and Biochar Addition on Soil Nitrogen, Carbon, and Super Rice Yield in Cold Waterlogged Paddy Soils of North China. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shao, T.; Lv, Z.; Yue, Y.; Liu, A.; Long, X.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, X.; Rengel, Z. The Mechanisms of Improving Coastal Saline Soils by Planting Rice. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sagan, M.A.M. Effect of polymer on drought tolerance of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Eur. J. Acad. Essays 2015, 2, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Xia, Z.L.; Zhou, C.J.; Wang, G.; Meng, X.; Yin, P.C. Insights into Salinity Tolerance in Wheat. Genes 2024, 15, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, A.V.G.; Neamati, S.H.; Tehranifar, A.; Emami, H. Evaluation of chlorophyll florescence and biochemical traits of lettuce under drought stress and super absorbent or bentonite application. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 10, 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- El-Tohamy, W.A.; El-Abagy, H.M.H.; Ahmed, E.M.; Aggor, F.S.; Hawash, S.I. Application of super absorbent hydrogel poly (acrylate/acrylic acid) for water conservation in sandy soil. Trans. Egypt. Soc. Chem. Eng. 2014, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, P.; Feng, N.; Zheng, D. Regulation of Photosynthetic Capacity and Ion Metabolism of Oilseed Rape Under Salt Stress by Prohexadione-Calcium Priming. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najar, R.; Aydi, S.; Sassi-Aydi, S.; Zarai, A.; Abdelly, C. Effect of salt stress on photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence in Medicago truncatula. Plant Biosyst. 2019, 153, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.H.; Pu, H.M.; Zhang, J.F.; Qi, C.K.; Zhang, X.K. Screening of Brassica napus for salinity tolerance at germination stage. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2013, 35, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, T.; Wang, Y.; Ning, S.; Mao, J.; Sheng, J.; Jiang, P. Assessment of the Effects of Biochar on the Physicochemical Properties of Saline–Alkali Soil Based on Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safavi, F.; Galavi, M.; Ramroodi, M.; Chaman, M.R.A. Effect of super absorbent polymer, potassium and manure animal to drought stress on qualitative and quantitative traits of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo). Int. J. Farming Allied Sci. 2016, 5, 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, N.J.; Yu, M.L.; Li, Y.; Jin, D.; Zhang, D.F. Prohexadione-calcium alleviates saline-alkali stress in soybean seedlings by improving the photosynthesis and up-regulating antioxidant defense. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 220, 112369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauth, D.M.; Bouldin, J.L.; Green, V.S.; Wren, P.S.; Baker, W.H. Evaluation of a polyacrylamide soil additive to reduce agricultural-associated contamination. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008, 81, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lu, H.; Fu, Z.; Luo, Z.; Duan, J. A Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation of the Model of Salt-Tolerant Crops Irrigated by Mariculture Wastewater Based on a Field Plot Experiment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, Z.Q.; Wu, B.C.; Xu, M.L.; Liu, C.; Shi, H.S.; Pang, B.; Miao, X.F. Effects of Compound Saline-Alkali Stress on Germination Period of Different Foxtail Millet Varieties and Screening of Saline-Alkali Tolerance Varieties. Crops 2024, 3, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.M.; Li, A.G.; Li, H.P.; Guan, M.W.; Wu, J.Y.; Shun, W.C.; Zhai, L.J.; Ma, L.; Guo, A.Q. Identification and screening of saline-alkali tolerant winter rapeseed varieties in the Bohai Rim region. Chin. J. Oil Crop Sci. 2025, 47, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Y.; Peng, T.; Xue, S.W. Mechanisms of plant saline-alkaline tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 281, 153916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Wang, S.B.; Wang, X.Y.; Ren, M.; Zhao, P.J.; Huang, Z.Y.; Jia, H.J.; Wang, J.H.; Lin, A.J. Effective strategies for reclamation of saline-alkali soil and response mechanisms of the soil-plant system. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, C.; Cosentino, S.L.; Romano, D.; Toscano, S. Relative Water Content, Proline, and Antioxidant Enzymes in Leaves of Long Shelf-Life Tomatoes Under Drought Stress and Rewatering. Plants 2022, 11, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenther, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoides: Pigments of photosynthesis. Methods Enzymol. INRA EDP Sci. 1987, 57, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, E.C.; Forstreuter, M.; Rillig, M.C.; Kohler, J. Biochar Increases Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Plant Growth Enhancement and Ameliorates Salinity Stress. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 96, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, W. Effects of Biochar on the Physicochemical Properties, Soil Biomass, and Maize Seedling Growth of Saline-Alkali Soil. Jiangsu J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, J.; Li, X.Y.; Li, Z.Q.; Wang, X.T.; Hou, N.; Li, D.P. Remediation of soda-saline-alkali soil through soil amendments: Microbially mediated carbon and nitrogen cycles and remediation mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; Qin, S.; Liu, Z. Revegetated shrub species recruit different soil fungal assemblages in a desert ecosystem. Plant Soil 2018, 435, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.W. The role of soil organic matter in maintaining soil quality in continuous cropping systems. Soil Tillage Res. 1997, 43, 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanté, M.; Riah-Anglet, W.; Cliquet, J.B.; Trinsoutrot-Gattin, I. Soil enzyme activity and stoichiometry: Linking soil microorganism resource requirement and legume carbon rhizodeposition. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D.; Vitousek, P.M. Responses of extracellular enzymes to simple and complex nutrient inputs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Duan, H.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S.; Xu, T.; Guo, B. Improved Effects of Combined Application of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria Azotobacter beijerinckii and Microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa on Wheat Growth and Saline-Alkali Soil Quality. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nava-Arsola, N.E.; Beltrán-Paz, O.; Martínez-Jardines, G.; Chávez-Vergara, B. Metabolic quotient and specific enzymatic activity in response to the addition of organic amendments to mining tailings. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 4239–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslya, A.V.; Iashnikov, A.V.; Poshvina, D.V.; Stepanov, A.A.; Vasilchenko, A.S. Extracellular Enzymes of Soils Under Organic and Conventional Cropping Systems: Predicted Functional Potential and Actual Activity. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Singh, B.P.; Collins, D.; Armstrong, R.; Van Zwieten, L.; Tavakkoli, E. Nutrient stoichiometry and labile carbon content of organic amendments control microbial biomass and carbon-use efficiency in a poorly structured sodic-subsoil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Soriano, M.C.; Kerré, B.; Kopittke, P.M.; Horemans, B.; Smolders, E. Biochar Affects Carbon Composition and Stability in Soil: A Combined Spectroscopy-Microscopy Study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilambo, O.A. Proline Content, Water Retention Capability and Cell Membrane Integrity as Parameters for Drought Tolerance in Two Peanut Cultivars. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2004, 70, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig-Oliver, M.; Fullana-Pericàs, M.; Bota, J.; Flexas, J. Genotype-Dependent Changes of Cell Wall Composition Influence Physiological Traits of a Long and a Non-Long Shelf-Life Tomato Genotypes under Distinct Water Regimes. Plant J. 2022, 112, 1396–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.; Lorenzo, H. The Nutritional Control of Root Development. Plant Soil 2001, 232, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiba, T.; Krapp, A. Plant Nitrogen Acquisition Under Low Availability: Regulation of Uptake and Root Architecture. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrasheed, K.G.; Mazrou, Y.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Osman, H.S.; Nehela, Y.; Hafez, E.M.; Rady, A.M.S.; El-Moneim, D.A.; Alowaiesh, B.F.; Gowayed, S.M. Soil Amendment Using Biochar and Application of K-Humate Enhance the Growth, Productivity, and Nutritional Value of Onion (Allium cepa L.) Under Deficit Irrigation Conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Jing, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Q. Effects of biochar amendment on rapeseed and sweet potato yields and water stable aggregate in upland red soil. Catena 2014, 123, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiaz, K.; Danish, S.; Younis, U.; Malik, S.A.; Raza Shah, M.H.; Niaz, S. Drought impact on Pb/Cd toxicity remediated by biochar in Brassica campestris. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2014, 14, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Arolu, F.; Chukwu, S.C.; Salisu, M.A.; Fagbohun, I.K.; Muftaudeen, T.K.; Swaray, S.; Haliru, B.S. Superabsorbent Polymer Hydrogels for Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttermann, A.; Orikiriza, L.J.B.; Agaba, H. Application of Superabsorbent Polymers for Improving the Ecological Chemistry of Degraded or Polluted Lands. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2009, 37, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andry, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Irie, T.; Moritani, S.; Inoue, M.; Fujiyama, H. Water Retention, Hydraulic Conductivity of Hydrophilic Polymers in Sandy Soil as Affected by Temperature and Water Quality. J. Hydrol. 2009, 373, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Mei, P.; Wang, W.; Yin, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, M.; Ou, X.; Cui, Z. Effects of Super Absorbent Polymer on Crop Yield, Water Productivity and Soil Properties: A Global Meta-Analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 282, 108290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaeil, P.; Habibi, D.; Boojar, M.M.A. Yield and yield component quality of red bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) cultivars in response to water stress and super absorbent polymer application. Ann. Biol. Res. 2012, 3, 5701–5704. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Gao, C.; Lu, D.; Tang, D.W.S. Effect of Long Term Application of Super Absorbent Polymer on Soil Structure, Soil Enzyme Activity, Photosynthetic Characteristics, Water and Nitrogen Use of Winter Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).