Abstract

This study aimed to address the limited infiltration capacity of the double ridge–furrow mulching system (DRFM) under heavy rainfall on the Loess Plateau, which exacerbates surface runoff and mid-summer soil water deficits in semi-arid rainfed areas. By incorporating infiltration holes to optimize the system, we evaluated their effects on soil water storage, maize growth, and water use efficiency (WUE). A two-year field experiment (2021–2022) comprised four treatments: conventional flat planting (CK), the traditional ridge-furrow system (CWC), the double ridge-furrow system (DWC), and the double ridge-furrow system with infiltration holes (DWCR). The experimental periods represented a normal precipitation year (2021, 410 mm) and a dry year (2022, 270 mm). Results indicated that the DWCR treatment established preferential flow pathways, significantly enhancing deep soil water storage and its utilization efficiency during critical phenological stages, particularly under drought. This improved deep water accelerated crop growth and boosted yield. Compared to the CK, CWC, and DWC treatments, the DWCR treatment significantly increased plant height, aboveground dry matter (ADM), yield, and WUE. Specifically, the DWCR treatment improved yield and WUE by 0.24–20.04% and 2.75–26.27%, respectively. In the dry year, the yield of the DWC treatment increased by 12.72% compared to its yield in the normal year, whereas the DWCR treatment achieved a greater increase of 19.18%. Root analysis confirmed that the DWCR treatment significantly increased root weight density in the 20–60 cm soil layer under drought, optimizing root spatial distribution and thereby enhancing deep water uptake and drought resistance. In conclusion, incorporating infiltration holes into the DRFM is an effective strategy for optimizing soil water distribution, improving crop drought tolerance and WUE, and promoting sustainable semi-arid rainfed agriculture.

1. Introduction

Climate change has led to significant fluctuations in global rainfall patterns and their seasonal distribution, posing serious challenges to agricultural productivity. Crop yields are influenced not only by genetic potential but also by environmental factors, including water availability, temperature, and nutrient supply [1,2,3]. This challenge is particularly pronounced in semi-arid regions, where water scarcity remains a major constraint to sustainable agricultural development [4,5]. In the face of global water shortages and rising populations, ensuring food security has become an urgent priority worldwide [6,7]. Notably, yield growth in irrigated agriculture has plateaued, with limited scope for further expansion [8]. In contrast, rainfed agriculture accounts for approximately 60% of global grain production, using around 80% of the world’s cultivated land, and sustains nearly 70% of the global population [9,10]. Therefore, unlocking the full potential of dryland farming through optimized water management strategies is critical for ensuring future food security.

The Chinese Loess Plateau is a typical rainfed agricultural region where crop production is heavily dependent on natural precipitation [6,11]. However, precipitation in this region is highly uneven, with over 60% occurring between July and September, and it is characterized by significant interannual variability, which severely constrains stable crop production [12]. As the dominant grain crop, spring maize occupies 27.3% of the total cultivated area [13]. However, when solely reliant on precipitation, it often struggles to achieve high and stable yields. Spring droughts commonly lead to insufficient soil water storage at sowing, impairing seedling emergence and early growth, whereas the middle and late phenological stages are often affected by summer drought stress, resulting in yield losses [14,15]. Therefore, developing effective soil and water conservation techniques to improve water use efficiency (WUE) is essential for promoting sustainable agricultural development in the region [16,17].

In response to these challenges, the double ridge–furrow mulching system (DRFM) was developed. By integrating ridge rainwater harvesting, furrow planting, and full plastic film coverage, this system has proven effective in improving agricultural productivity in dryland regions [3,6,18,19]. However, its effectiveness on the Loess Plateau is limited by inadequate water infiltration during concentrated, intense rainfall events [20]. Short-term heavy rainfall often exceeds the soil’s infiltration capacity, resulting in precipitation loss as surface runoff [21]. Furthermore, long-term continuous tillage has led to the formation of a compacted plow pan at a depth of 20–40 cm [22]. The compaction of the plow pan restricts deep water infiltration, which promotes surface runoff and increases evaporation during periods of intense rainfall [23,24]. This issue is exacerbated by progressive soil compaction in the root zone during the middle and late phenological stages, which further impedes the downward movement of water [25]. Collectively, these factors prevent substantial rainfall from being stored in deep soil layers. Consequently, storm rainfall is underutilized during periods of high crop water demand, ultimately reducing the ability of crops to withstand summer drought [19].

To overcome the limitations of mismatched rainfall harvesting and infiltration capacity, this study introduces infiltration holes into the DRFM as an optimization measure. These holes, with a depth of 50 cm, are designed to penetrate the plow pan typically located at 30–40 cm, thereby creating artificial preferential flow pathways. This design enhances water infiltration, reduces surface runoff, and promotes the downward movement of moisture into deeper soil layers [26,27]. From a hydraulic perspective, infiltration holes alter soil water movement by enhancing local hydraulic conductivity, which allows water to bypass low-permeability layers and promotes rapid infiltration [28,29]. Additionally, infiltration holes form micro-scale wetting zones around the pores, which encourage downward root growth and improve the uptake of deep soil water [30]. In recent years, this technique has been applied and validated in various dryland farming systems, demonstrating its potential to improve soil water storage (SWS) and mitigate crop water stress [31]. However, the synergistic effects of combining infiltration holes with the DRFM on maize growth and WUE remain underexplored. Based on this rationale, we propose integrating infiltration holes into the DRFM to enhance the capture of intense rainfall, improve deep SWS, and provide a sustained water supply during critical crop phenological stages.

We hypothesize that (1) the DWCR system enhances rainwater infiltration and deep SWS by creating preferential flow pathways; (2) it alleviates drought stress during key reproductive stages, thereby promoting plant growth and dry matter (ADM); and (3) without significantly increasing total water consumption, the DWCR system synergistically improves grain yield and WUE.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

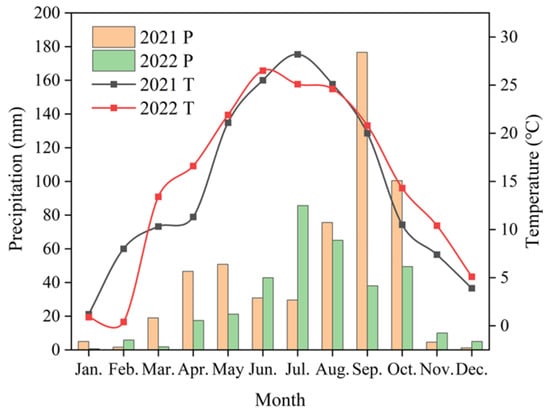

The experiment was conducted from 2021 to 2022 at a rainfed agricultural experimental site in Pengyang County, Ningxia, China (35°51′ N, 106°47′ E, 1695 m above sea level). The region experiences a typical semi-arid continental monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of ~8 °C, and 2518 annual sunshine hours. The long-term average precipitation in the area is between 350 mm and 550 mm, with over 60% of rainfall occurring from July to September. During the experimental period, the two growing seasons exhibited contrasting precipitation patterns. In 2021, the region received 410 mm of rainfall, which falls within the range of the long-term climatological normals for the area (350–550 mm). In contrast, 2022 received only 270 mm of rainfall, which is substantially below this climatological average and therefore represents a dry year (Figure 1). The soil type in the study area is Loessial soil with a silt loam texture. Before sowing in 2021, baseline soil properties were measured at a depth of 0–40 cm and found to be as follows: bulk density, 1.26 g cm3; pH, 8.2; organic matter, 6.39 g kg−1; total nitrogen, 0.78 g kg−1; and available phosphorus, 4.62 mg kg−1. The experimental field had a consistent history of maize cultivation and tillage practices, ensuring uniform initial conditions across all experimental plots.

Figure 1.

Monthly precipitation distribution and temperature variation in the study area during 2021 and 2022. Precipitation (P); temperature (T).

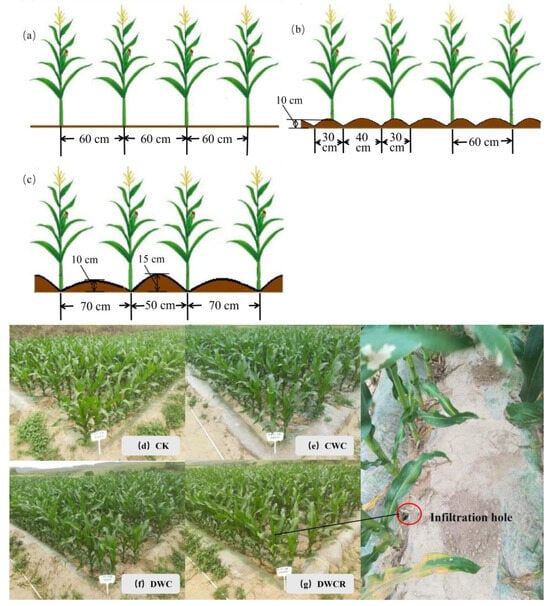

2.2. Experimental Design and Field Management

Four treatments were established, comprising a control and three ridge-furrow configurations with plastic film mulching: conventional flat planting (CK), a traditional ridge-furrow system (CWC), a double ridge-furrow system (DWC), and the double ridge-furrow system with infiltration holes (DWCR). A detailed description of each treatment is provided in Table 1, and schematic diagrams are shown in Figure 2. These infiltration holes, installed annually in the planting furrows before the rainy season (early July), were positioned 10 cm laterally from the plants. Each hole had a diameter of 10 cm and a depth of 50 cm, spaced 1 m apart. The walls of the holes were naturally compacted to maintain stability, creating preferential flow pathways for enhanced rainwater infiltration. All treatments were entirely covered with 0.01 mm transparent polyethylene film, and a consistent fertilization rate was applied across all treatments. The experiment employed a randomized complete block design with four treatments and three replications, resulting in 12 plots, each measuring 57.6 m2 (8 m × 7.2 m). To prevent lateral water movement, soil ridges (50 cm wide × 20 cm high) were constructed around each plot, and the edges of the plastic film were buried 10 cm deep to ensure effective sealing.

Table 1.

Description of experimental treatments.

Figure 2.

Diagram of different ridging planting methods. CK, conventional flat planting (a,d); CWC, a traditional ridge-furrow system (b,e); DWC, a double ridge-furrow system (c,f); DWCR, the double ridge-furrow system with infiltration holes (g).

The test cultivar used was Zhengcheng 018 (Henan Seed Industry Group Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China), a locally dominant spring maize variety. Sowing was carried out on 17 April 2021, and 19 April 2022, using a hand operated planter for hill placement within the planting furrows. Seeds were sown at a depth of 5 cm, with a spacing of 25 cm × 60 cm, achieving a theoretical planting density of 67,500 plants ha−1. Thinning and final seedling establishment were performed 15 days after emergence. A uniform fertilization scheme was applied to all treatments, with total application rates of N 260 kg ha−1, P2O5 100 kg ha−1, and K2O 75 kg ha−1 [3,6]. Before sowing, the entire amounts of phosphorus and potassium fertilizers, along with 40% of the nitrogen fertilizer, were broadcast as a basal application and incorporated into the 20–30 cm soil layer via rotary tillage. The remaining nitrogen fertilizer was split applied in two equal doses (30% each) in late June and early August. Ridge formation and film mulching were completed one week before sowing, with the film edges buried under soil (width ≥ 5 cm) to protect against wind. Throughout the growing season, crops relied exclusively on natural precipitation and received no irrigation. Manual weeding was performed three times, corresponding to the seedling, jointing, and silking stages. Maize was harvested at physiological maturity (3 October 2021, and 5 October 2022), and the plastic film was retained in the field post-harvest and remained until the following year’s sowing to reduce soil water evaporation.

2.3. Sampling and Measurements

2.3.1. Soil Water Storage

Soil water dynamics were monitored using a Neutron Probe–CNC 503 (Beijing Nuclear Instrument Factory, Beijing, China). A 3 m long access tube was installed at the center of each plot for this purpose. Measurements were taken at key maize phenological stages (seedling, jointing, silking, filling, and physiological maturity), with readings recorded at 10 cm vertical intervals. To calibrate the neutron probe readings against absolute soil water content, soil samples were collected using an auger at 10 cm intervals from the 0–300 cm soil layer, both before sowing and after harvest. The samples were immediately sealed and transported to the laboratory, where they were oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight (a process that took approximately 24 h). The gravimetric soil water content was then calculated using the following equation:

where SWC is the gravimetric soil water content (%), W1 is the fresh soil weight (g), and W2 is the oven-dried soil weight (g).

SWC = (W1 − W2)/W2 × 100%

A standard calibration curve was developed to convert neutron probe counts to volumetric water content. Three locations within the experimental area were randomly selected for access tube installation. Calibration began after the soil around the tubes had stabilized. A 50 cm × 50 cm area was demarcated around each tube, and borders were constructed with the surface leveled. This area was then continuously irrigated for 4 h and allowed to equilibrate for 24 h to ensure complete water infiltration. The standard count rate of the neutron probe was recorded first. Subsequently, neutron counts were measured at 10 cm depth intervals along each access tube, with three replicates per location. Immediately following these measurements, soil samples were collected at 10 cm intervals from the 0–100 cm depth adjacent to each tube. The volumetric water content of these samples was determined using the gravimetric method. These values were then regressed against the average neutron counts from the corresponding depths to establish the calibration curve (Figure S1). All neutron counts obtained during the monitoring period were converted to volumetric soil water content using the regression equation derived from this calibration. Based on the resulting volumetric water content data, SWS (mm of water per layer) in the 0–300 cm layer was calculated using the following formula:

where SWCi is the volumetric soil water content of the i-th layer (%), BDi is the soil bulk density of the i-th layer (g cm−3), SDi is the soil depth of the i-th layer (cm), and i represents the soil layer identifier (0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, …, 290–300 cm).

SWS = Σ (SWCi × BDi × SDi × 10)

To elucidate the relationship between vertical soil water storage dynamics and maize growth, this study divided the 0–300 cm soil profile into three layers based on maize root distribution and water uptake characteristics [32,33]. The shallow layer (0–50 cm), characterized by dense root systems, responds rapidly to precipitation and evaporation and serves as the primary source of water during the early and middle phenological stages. The middle layer (50–200 cm) is a critical water extraction zone during the mid-to-late phenological stages of maize, playing an essential role in alleviating drought stress during key reproductive periods. The deep layer (200–300 cm) can be utilized under extreme drought conditions, reflecting the system’s drought resistance capacity and the potential of deep SWS. All subsequent spatiotemporal analyses of soil water storage dynamics were conducted within this stratified framework.

2.3.2. Soil Bulk Density

Soil bulk density was determined before sowing in April 2021. Three sampling areas were randomly selected within the experimental field. From each area, undisturbed soil cores were collected at 10 cm intervals, ranging from 0–10 cm to 90–100 cm depth, using 100 cm3 stainless steel cutting rings, with three replicates per layer. After transport to the laboratory, the samples were cleared of surface plant residues and oven-dried at 105 °C to a constant weight. Bulk density for each layer was calculated by dividing the oven-dried soil mass by the volume of the cutting ring.

Due to practical constraints, direct sampling below 100 cm was not feasible. Given that the Loessial soil in this region exhibits deep, homogeneous profiles, we estimated the bulk density for deeper layers using the average value from the 90–100 cm layer. This approach is further supported by direct regional evidence: a specialized study on deep Loess profiles confirmed that soil bulk density remains highly stable below 100 cm, with minimal variation down to depths exceeding 200 m [34]. This estimation method, grounded in the principle of soil homogeneity and regional empirical data, is well established in soil physics research [35,36]. We assert that this approach is methodologically sound, maintains potential errors within an acceptable margin, and does not compromise the validity of relative comparisons of SWS among treatments.

2.3.3. Dry Matter and Plant Height

At five critical maize phenological stages (seedling, jointing, silking, filling, and physiological maturity), five representative plants were randomly selected from each plot. Plant height (PH) was measured, after which the plants were cut at ground level. The samples were placed in paper bags, transported to the laboratory, and prepared for ADM determination. They were initially fixed at 105 °C in a forced air oven for 30 min and then dried at 65 °C until constant weight was achieved (approximately 48–72 h). After weighing, the average ADM from the five plants was calculated and recorded as the per-plant ADM for the plot.

2.3.4. Root Sampling and Root Weight Density

At maize physiological maturity, three representative plants were randomly selected from each plot for root sampling using the profile excavation method. A rectangular sampling area of 40 cm × 25 cm was marked around the base of each plant stem. Soil was excavated in successive layers at depths of 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, …, 50–60 cm, with soil from each layer kept separate. The samples were placed in nylon mesh bags and gently rinsed with flowing tap water until the roots were completely separated from the soil and free of adhering particles. The cleaned roots were carefully examined to remove any remaining impurities. These root samples were then placed in envelopes, oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight and weighed to determine the root dry weight (M, mg) for each soil layer. Root weight density (RWD, mg cm−3) was calculated using the following formula:

where M is the root dry weight of the layer (g), A is the sampling area (cm2), and D is the thickness of the corresponding soil layer (cm).

RWD = M/(A × D)

2.3.5. Maize Yield

At maize physiological maturity, three yield quadrats (30 m2 each, 5 m × 6 m) were established in the central area of each plot, excluding border rows. All maize ears within these quadrats were harvested. The grain yield was determined and adjusted to 14% moisture content.

2.3.6. Total Evapotranspiration, Water Use Efficiency, and Precipitation Use Efficiency

The seasonal total evapotranspiration (ET, mm) for maize was calculated using the soil water balance method. The experimental site is a rainfed agricultural area with no irrigation, and the groundwater table is too deep (>15 m) to contribute to the root zone soil water via capillary rise [37]. Therefore, the water balance calculation can be simplified to the following equation:

where P is the total growing season precipitation (mm), and ΔSWS is the difference in SWS in the 0–300 cm layer between pre-sowing and post-harvest (mm).

ET = P + ∆SWS

WUE (kg ha−1 mm−1) measures the efficiency of converting a unit of water into maize yield. Precipitation use efficiency (PUE, kg ha−1 mm−1) reflects how efficiently natural precipitation is converted into maize yield in rainfed systems. These parameters were calculated using the following formulas:

where GY is the maize grain yield (kg ha−1), ET is the total seasonal evapotranspiration (mm), and P is the total precipitation during the growing period (mm).

WUE = GY/ET

PUE = GY/P

2.4. Statistical Analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to compare SWS, maize growth parameters, and WUE among ridge-furrow configurations at each growth stage or soil layer separately. When a significant treatment effect was found (p < 0.05), means were separated using Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) post hoc test. Two-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the effects of ridge-furrow configuration, year, and their interaction on these variables. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to assess pairwise linear relationships between SWS and maize growth and WUE. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 10.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Figures were produced using OriginPro 2024 (Version 2024b, OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA), except for the correlation heatmap, which was generated with the “corrplot” package in R (version 4.3.1).

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Soil Water Storage

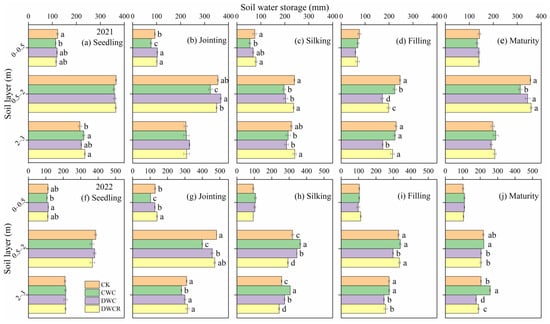

The spatiotemporal dynamics of SWS were significantly influenced by the combined factors of year, treatment, soil depth, and maize phenological stage (Table 2). The DWCR treatment notably enhanced the spatiotemporal distribution of soil water storage by improving infiltration processes. The effectiveness of this treatment exhibited systematic variation across years with differing precipitation patterns (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Mean square significance among treatments and interactions for soil water storage, maize growth, and water use efficiency.

Figure 3.

Dynamic variation in soil water storage during two growing seasons of maize. Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Tukey’s HSD test.

During the early phenological stages (from seedling to jointing), differences in SWS between treatments were primarily observed in the 0–50 cm soil layer. The DWCR treatment maintained significantly higher SWS at the jointing stage in both years (2021: 101.26 mm; 2022: 140.33 mm), outperforming both the CWC and CK treatments (Figure 3b,g).

During the late phenological stages (from silking to physiological maturity), the vertical redistribution of soil water storage showed distinct annual variations, particularly in the 200–300 cm soil layer. The year with near-normal precipitation (2021), the DWCR treatment achieved deep layer SWS of 241.44 mm at silking and 214.75 mm at filling, representing significant increases of 16.29% and 23.59%, respectively, compared with the DWC treatment (p < 0.05) (Figure 3c,d). In contrast, during the dry year of 2022, the DWCR treatment consistently maintained lower SWS at the same depths throughout the late phenological stages compared to the other treatments. It also exhibited significantly reduced SWS in the primary root zone (50–200 cm) during the silking stage. By physiological maturity, deep SWS in both the DWCR and DWC treatments was largely depleted, whereas the CWC treatment maintained the highest storage capacity (257.08 mm) (Figure 3j). This water depletion pattern suggests that, under drought conditions, crops in the DWCR treatment more effectively utilized middle and deep soil water reserves to cope with water stress during critical reproductive stages, ensuring grain filling and yield formation.

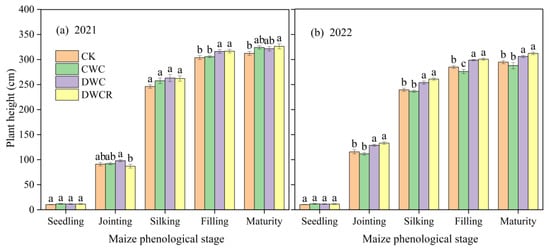

3.2. Plant Height

Maize PH was significantly influenced by both year and treatment (Table 2), underscoring the critical role of water availability in vegetative growth. The effect of the DWCR treatment varied significantly with phenological stage and precipitation year (Figure 4). After the jointing stage, treatment effects became evident and followed distinct patterns depending on precipitation conditions. In the normal precipitation year of 2021, the DWC treatment achieved the maximum PH (98 cm), which was significantly higher than that of the DWCR treatment (86.89 cm) (Figure 4a). In contrast, during the dry year of 2022, the DWCR treatment exhibited a clear growth advantage, reaching a PH of 133 cm, which was significantly taller than both the CK and CWC treatments (Figure 4b). From silking to physiological maturity, the growth advantage of the DWCR treatment was particularly pronounced under drought conditions. In 2021, its PH was only significantly greater than that of the CK treatment. However, in 2022, the DWCR treatment consistently maintained the highest PH across the silking (260.89 cm), filling (300.56 cm), and physiological maturity (312.22 cm) stages, with significant differences observed among treatments (Figure 4a,b). These results suggest that under drought conditions, the DWCR treatment captured water more effectively during the middle and late phenological stages, supporting stable and superior PH development.

Figure 4.

Dynamic variation in plant height of maize during two growing seasons. Values are mean ± SE (n = 5). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Tukey’s HSD test.

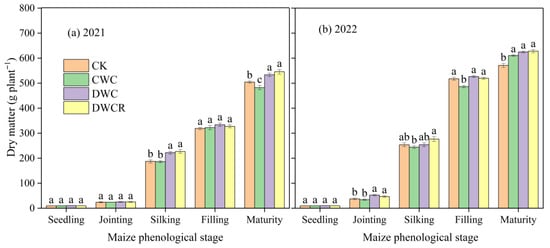

3.3. Dry Matter

ADM in maize was significantly influenced by both year and treatment (Table 2). The effectiveness of the DWCR treatment became more evident across phenological stages, with particularly pronounced advantages under drought conditions (Figure 5). During the early phenological stages (from seedling to jointing), no significant differences in ADM were observed among treatments, as crop growth was primarily influenced by initial soil and environmental conditions. In the mid- phenological stages (from jointing to silking), treatment effects became more evident. In the dry year of 2022, the DWC treatment achieved the highest ADM at the jointing stage (52.41 g plant−1). However, by the silking stage, the DWCR treatment showed the highest ADM in both years (2021: 226.75 g plant−1, 2022: 276.52 g plant−1), significantly surpassing the CWC treatment (Figure 5a,b). During the late phenological stages (from filling to physiological maturity), the DWCR treatment maintained its advantage. At physiological maturity, it achieved the highest ADM in the normal year (2021: 545.63 g plant−1) and maintained the highest level in the dry year (2022: 627.74 g plant−1). All ridge–furrow treatments exhibited significant superiority over the CK treatment. These results suggest that the DWCR treatment effectively sustained photosynthetic activity during the reproductive growth phase, demonstrating a strong capacity for ADM, particularly under drought stress.

Figure 5.

Dynamic variation in dry matter accumulation of maize across two growing seasons. Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Tukey’s HSD test.

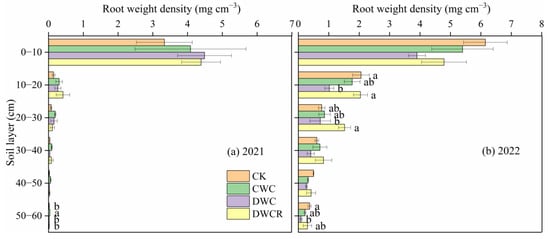

3.4. Root Weight Density

The vertical distribution of maize RWD was significantly affected by both year and treatment (Table 2). The DWCR treatment demonstrated a pronounced ability to optimize root architecture under drought conditions (Figure 6). In the normal year (2021), no significant differences in RWD were observed among treatments within the 0–60 cm soil profile, although the DWCR treatment tended to exhibit higher total RWD than other treatments. In contrast, during the dry year (2022), significant differences emerged, particularly within the 20–60 cm soil layer. In this critical zone, the DWCR treatment achieved root weight densities of 2.04 g cm−3 (10–20 cm) and 1.52 g cm−3 (20–30 cm), significantly higher than those of the DWC treatment (Figure 6b). Additionally, the overall RWD across all treatments was generally higher in 2022 than in 2021. This trend corresponded with increases in PH and ADM accumulation observed during the dry year, reflecting the crop’s adaptive strategy of developing a more robust root system in response to water scarcity.

Figure 6.

Root weight density of maize after harvest in two growing seasons. Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 according to Tukey’s HSD test.

3.5. Maize Yield, Water Use Efficiency, and Precipitation Use Efficiency

Maize yield, WUE, and PUE were significantly affected by both year and treatment (Table 2). Overall, all ridge–furrow mulching treatments consistently improved productivity and WUE compared to flat planting, with the DWCR treatment showing superior performance under drought conditions. In the normal year of 2021, the DWC treatment achieved the highest yield (13,028.6 kg ha−1), which was not significantly different from that of the DWCR treatment. In contrast, during the dry year of 2022, both the DWCR (14,721.1 kg ha−1) and DWC (14,685.2 kg ha−1) treatments significantly outperformed the CWC and CK treatments (Table 3), demonstrating stable yield performance under water stress. Across the two years, the DWCR treatment improved maize yield by 0.24% to 20.04% and enhanced WUE by 2.75% to 26.27% compared to the other treatments (CK, CWC, and DWC). The DWCR treatment also maintained the highest WUE in both years (2021: 32.2 kg ha−1 mm−1; 2022: 33.6 kg ha−1 mm−1), highlighting its stability across varying precipitation conditions (Table 3). Similarly, all ridge–furrow treatments exhibited significantly higher PUE than the CK treatment. Notably, in the low-precipitation year of 2022, PUE was significantly higher across all treatments compared to 2021. Under drought conditions, the DWCR treatment achieved the highest PUE (54.5 kg ha−1 mm−1), confirming its exceptional capacity to convert limited precipitation into maize yield and underscoring its critical role in water-saving and yield-enhancing strategies for drought-prone regions.

Table 3.

Maize yield and water use efficiency during two growing seasons.

4. Discussion

4.1. Adding Infiltration Holes to the DRFM Optimized the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Soil Water Storage

Preferential flow is a critical hydrological process in which water rapidly bypasses the soil matrix through macropores, root channels, and fissures to reach deeper soil layers [28,29]. In agricultural ecosystems, this non-equilibrium flow enhances WUE and typically results from natural processes such as bioturbation, root growth, and cycles of wetting and drying [38,39,40]. In recent years, artificial approaches to creating preferential flow pathways, such as drilling infiltration holes, have been demonstrated to improve deep soil water recharge and rainfall use efficiency [21,27,41,42]. The DRFM with infiltration holes used in this study represents a systematic application of this principle.

The results demonstrate that the DWCR treatment significantly altered the vertical distribution and dynamics of soil water storage by establishing preferential water transport pathways. This mechanism was particularly pronounced during the later crop phenological stages and supports the first hypothesis of this study. During the normal precipitation year of 2021, the DWCR treatment markedly increased SWS at the 200–300 cm depth from the silking to the filling stages (Figure 3c,d). This improvement can be attributed to the infiltration holes, which acted as rapid conduits that efficiently channeled intense mid-season rainfall into deeper soil layers, creating a “soil water reservoir” for subsequent crop use. These findings are consistent with the mechanism of preferential flow enhancing water infiltration reported by Wang et al. (2021) and align with agricultural management strategies in semi-arid regions that aim to increase deep soil water recharge [27,43].

In the drier year of 2022, the DWCR treatment exhibited a distinct pattern of soil water regulation. Limited rainfall was rapidly diverted to deeper soil layers through the infiltration holes, resulting in significantly lower water storage within the 50–200 cm profile during the silking stage compared with other treatments (Figure 3h). This “water bypass flow” effect is consistent with earlier reports of preferential deep percolation under moisture-deficient conditions [28]. Importantly, the redirected water in the deep layers was not lost but became available during subsequent critical phenological stages, particularly the filling period. The marked depletion of soil water in the 200–300 cm layer under the DWCR treatment at physiological maturity indicates an active reliance on deeply stored water to sustain plant functions under drought stress. This adaptive mechanism highlights the ecological significance of DWCR in promoting deep soil water utilization and enhancing crop resilience in water-limited environments [44].

In summary, compared to the DRFM, the DWCR system addresses the bottleneck of runoff loss during heavy rainfall by creating point source preferential flow pathways [25,45]. This significantly enhances its ability to capture and store intense, erratic precipitation. The mechanism aligns with the concept of optimizing micro-catchment design in rainwater harvesting to improve PUE [46]. Overall, the DWCR system offers a novel technical approach and theoretical foundation for farmland water management in semi-arid regions.

4.2. Adding Infiltration Holes to the DRFM Promoted Root–Shoot Synergistic Growth and ADM

The spatial distribution of soil water storage is a critical ecological factor that governs the adaptive architecture of crop root–shoot systems. Our findings strongly support the second hypothesis regarding water-mediated growth regulation. During the severe drought of 2022, the DWCR treatment promoted superior root architecture in the 20–60 cm soil layer. Specifically, in the 20–30 cm soil layer, the RWD under the DWCR treatment was 1.52 g cm−3, 111.1% higher than that under the DWC treatment (Figure 6b). This increase reflects not only a typical hydrotropic response but also a systematic optimization of root spatial distribution in search of water [30,47]. The preferential flow paths created by the infiltration holes improved moisture conditions in the mid-deep soil layers, forming humid micro-zones that encouraged roots to explore greater depths and enhance their ability to utilize deep soil water [30]. Although our root measurements were confined to 0–60 cm, the marked depletion of water in the 200–300 cm layer under DWCR (Figure 3j), coupled with the sustained canopy growth during drought, strongly implies that roots effectively accessed and utilized these deep water reserves. This deep root architecture laid a solid foundation for canopy development and biomass accumulation, proving crucial for improving crop drought resistance [48,49].

Corresponding to the optimized root distribution, the DWCR treatment also showed consistent advantages in canopy development. From the jointing stage onward, it exhibited significantly greater PH (133 cm) and a higher ADM. By physiological maturity, it achieved the highest ADM (627.74 g plant−1) (Figure 4b and Figure 5b). This root–shoot synergy suggests that water stored in deep soil layers through the infiltration holes during earlier stages was crucial during the water-sensitive silking to filling period. It effectively alleviated summer drought stress and sustained high photosynthetic activity [18].

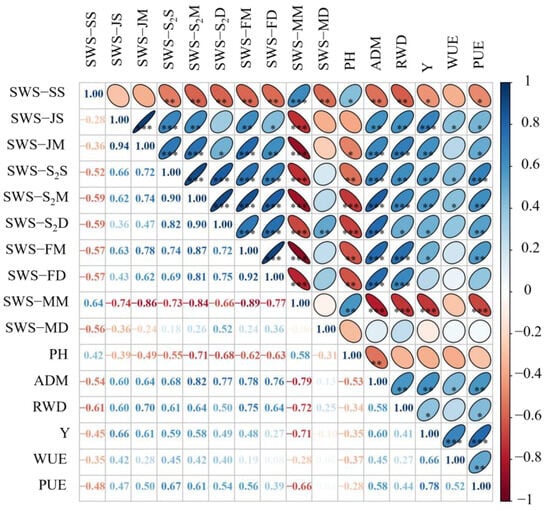

The root–shoot-water relationship revealed that, although RWD was not significantly correlated with final yield, it was significantly and positively correlated with soil water status during critical phenological stages (Figure 7). This highlights that the primary function of the root system lies in its efficiency for water absorption and transport, rather than in biomass accumulation alone [50]. RWD correlated most strongly with soil water storage in the middle layer during the filling stage (SWS-FM, r = 0.75, p < 0.01). This indicates that the root system measured at maturity was not merely a residual product of earlier growth conditions but was actively involved in water uptake during the filling period. The DWCR treatment exhibited a distinct water use pattern: storing more water in deeper soil layers earlier (at the silking stage) and subsequently depleting it primarily from the middle layers later (at the filling stage). Therefore, this correlation supports the view that, during the critical filling stage, roots actively forage for water in the relatively moist middle layer—a direct consequence of the earlier deep percolation event (Figure 7). In summary, optimized soil water management promoted root extension into deeper layers, establishing a more effective water absorption system. This system ensured canopy water supply during critical demand periods and, through root–shoot synergy, ultimately facilitated efficient ADM production and yield formation.

Figure 7.

The relationship between soil water storage and maize growth. Seedling stage shallow soil water storage (SWS-SS); jointing stage shallow soil water storage (SWS-JS); jointing stage middle soil water storage (SWS-JM); silking stage shallow soil water storage (SWS-S2S); silking stage middle soil water storage (SWS-S2M); silking stage deep soil water storage (SWS-S2D); filling stage middle soil water storage (SWS-FM); filling stage deep soil water storage (SWS-FD); maturity stage middle soil water storage (SWS-MM); maturity stage deep soil water storage (SWS-MD); plant height (PH); aboveground dry matter (ADM); root weight density (RWD); yield (Y); water use efficiency (WUE); precipitation use efficiency (PUE). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

4.3. Synergistic Enhancement of Maize Yield and WUE

Optimizing management practices to enhance maize yield and WUE is a common agricultural management approach in semi-arid regions [7,51,52]. The DWCR treatment in our study led to simultaneous improvements in both maize yield and WUE, thereby validating the third hypothesis. Across both growing seasons, although the DWCR and DWC treatments showed no significant difference in yield (e.g., 14,721.1 kg·ha−1 and 14,685.2 kg·ha−1 in 2022), both significantly outperformed the other treatments (Table 3). This suggests that the DRFM alone can ensure high yields under normal precipitation, while the synergistic effect of infiltration holes becomes critical during dry years. The infiltration holes effectively converted otherwise ineffective precipitation into a spatially and temporally optimized water source, safeguarding filling and ensuring stable yields under high stress conditions. This mechanism works by storing water in deep soil layers (spatially) and releasing it during critical stages, such as filling (temporally) [18]. Although this study did not include scenarios for wet years, the water regulation mechanism of the DWCR treatment—enhancing deep percolation during intense rainfall—suggests a potential to store surplus precipitation in deeper soil layers, which could be available later in the same season. The creation of a ‘deep soil water reservoir’ within the growing season is a key mechanism for mitigating intra-seasonal drought stress, as observed in our study. Furthermore, this mechanism holds promise for improving water productivity across seasons [15]. Future research monitoring soil water dynamics over multiple years, including fallow periods, is needed to explicitly quantify the potential of the DWCR system for cross-seasonal water storage and its benefit for subsequent crops, such as alleviating sowing-time drought stress.

The enhanced WUE observed in the DWCR treatment (32.2 kg ha−1 mm−1 in 2021 and 33.6 kg·ha−1 mm−1 in 2022) results from a dual-driven mechanism combining source expansion and sink reduction. Source expansion involves the creation of preferential flow pathways through infiltration holes, which redirect runoff prone water from heavy rainfall into deeper soil layers, transforming it into available reserves for later crop use [53]. Sink reduction is achieved through complete plastic film mulching, which maximizes the suppression of unproductive soil evaporation [54]. Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between SWS at maturity and ADM (Figure 7), confirming that high-yielding populations deplete soil water storage more thoroughly. Therefore, lower profile water storage at maturity should not be viewed as a system deficiency but rather as an indicator of efficient water use, where more soil water is converted into biomass [55].

Particularly noteworthy is that, under the 51.8% rainfall reduction in 2022, all treatments exhibited significantly higher PUE compared to the normal year of 2021, with the DWCR treatment achieving the highest efficiency (54.5 kg ha−1 mm−1). This high efficiency under low rainfall highlights the considerable potential of the DWCR treatment to address climate variability and increasing aridity. Research indicates that, while the absolute amount of precipitation is important, the ability to capture, store, and convert it is ultimately more critical in semi-arid agricultural systems [56,57]. By combining film mulching for evaporation suppression with infiltration holes for water diversion, the DWCR treatment actively regulates the spatiotemporal distribution of limited precipitation, significantly enhancing its conversion to maize yield. This strategy of storing water in soil for use during critical periods has significant practical value for mitigating both seasonal and interannual droughts [58].

5. Conclusions

This two-year field study demonstrates that incorporating infiltration holes into the DRFM significantly enhances maize production in semi-arid China. The infiltration holes create preferential flow paths, improving deep SWS, stimulating root growth, and alleviating drought stress during critical phenological stages. Compared with the DWC treatment, DWCR increased SWS in the 200–300 cm layer by 16.29–23.59% in a normal year and promoted efficient use of middle–deep soil water storage (50–300 cm) during a dry year. Enhanced root development supported greater PH, ADM, yield, and WUE, with the DWCR treatment achieving a 19.2% yield increase and the highest PUE (54.5 kg ha−1 mm−1) under drought conditions. These results indicate that DWCR effectively overcomes the limited infiltration of conventional double-ridge systems, providing a practical strategy for sustainable rainfed agriculture under variable rainfall and seasonal drought.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122871/s1, Figure S1: Calibration curve of neutron probe. y is soil volumetric water content; x is the rate of the measured value of the neutron probe to the standard value; R2 is the coefficient; R is the measured value of the neutron probe, and Rs is the standard value of the neutron probe; Table S1: Dynamic variation in soil water storage during two growing seasons of maize. Values are mean ± SE. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among all treatments at p < 0.05; Table S2: Vertical distribution of maize root weight density under different treatments (2021–2022).

Author Contributions

J.G., Writing—Review and Editing, Writing—Original Draft, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization; K.W., Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; X.Z., Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; G.L., Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; G.W., Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; Z.Z., Writing—Review and Editing, Investigation; J.Z., Writing—Review and Editing, Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was jointly funded by the Key Research and Development Plan of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2020BCF01001, 2023BEG02042) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42107363).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lobell, D.B.; Gourdji, S.M. The influence of climate change on global crop productivity. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, M.; Langridge, P. Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science 2010, 327, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.D.; Kamran, M.; Xue, X.K.; Zhao, J.; Cai, T.; Jia, Z.K.; Zhang, P.; Han, Q.F. Ridge-furrow mulching system drives the efficient utilization of key production resources and the improvement of maize productivity in the Loess Plateau of China. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 190, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.L.; Wang, S.Y.; Li, Y.P.; Yang, X.M.; Li, S.Z.; Ma, M.S. Film mulched furrow-ridge water harvesting planting improves agronomic productivity and water use efficiency in Rainfed Areas. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.Q.; Chen, Y.L. Mulching improves yield and water-use efficiency of potato cropping in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2018, 221, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, H.L.; Li, L.C.; Liu, X.L.; Qian, R.; Wang, J.J.; Yan, X.Q.; Cai, T.; Zhang, P.; Jia, Z.K.; et al. Ridge-furrow mulching system regulates hydrothermal conditions to promote maize yield and efficient water use in rainfed farming area. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 232, 106041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Wang, H.; Sui, Q.Q.; Dong, B.X.; Liao, Z.Q.; Yang, C.L.; Deng, X.W.; Li, Z.J.; Fan, J.L. Effects of mulching cultivation patterns on maize yield, resources use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions of rainfed summer maize on the Loess Plateau of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 315, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, X.Y.; Li, F.C.; Hu, G.R.; Liu, Q.L.; Zhang, E.H.; Wang, H.L.; Davies, R. Optimum ridge-furrow ratio and suitable ridge-mulching material for Alfalfa production in rainwater harvesting in semi-arid regions of China. Field Crops Res. 2015, 180, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Thornton, P.K.; Power, B.; Bogard, J.R.; Remans, R.; Fritz, S.; Gerber, J.S.; Nelson, G.; See, L.; Waha, K.; et al. Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: A transdisciplinary analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e33–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashnik, D.; Jacobus, H.; Barghouth, A.; Wang, E.J.; Blanchard, J.; Shelby, R. Increasing productivity through irrigation: Problems and solutions implemented in Africa and Asia. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2017, 22, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.L.; Zhang, P.; Liu, X.L.; Ali, S.; Chen, X.L.; Jia, Z.K. Impacts of different mulching patterns in rainfall-harvesting planting on soil water and spring corn growth development in semihumid regions of China. Soil Res. 2017, 55, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.L.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.L.; Guo, J.J.; Jia, Z.K. Effect of different mulches under rainfall concentration system on corn production in the semi-arid areas of the Loess Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, S.J.; Li, S.Q.; Chen, X.P.; Chen, F. Growth and development of maize (Zea mays L.) in response to different field water management practices: Resource capture and use efficiency. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Xie, B.T.; Dong, S.X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Li, A.X.; Wang, Q.M. Effect of plastic mulching on the photosynthetic capacity, endogenous hormones and root yield of summer-sown sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L). Lam.) in Northern China. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.M.; Chen, K.Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Ali, S.; Manzoor Sohail, A.; Fahad, S. Mulch covered ridges affect maize yield of maize through regulating root growth and root-bleeding sap under simulated rainfall conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhou, H.; Luo, C.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Li, X.Y.; Li, F.M.; Xiong, L.B.; Kavagi, L.; Nguluu, S.N.; et al. Ridge-furrow plastic-mulching with balanced fertilization in rainfed maize (Zea mays L.): An adaptive management in east African Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 236, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, W.J.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.M.; Li, C.B. Is crop biomass and soil carbon storage sustainable with long-term application of full plastic film mulching under future climate change? Agric. Syst. 2017, 150, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, X.Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.J.; Zhang, T.B.; Dong, Q.G.; Feng, H.; Zhang, W.X.; Siddique, K.H.M. Ridge planting with transparent plastic mulching improves maize productivity by regulating the distribution and utilization of soil water, heat, and canopy radiation in arid irrigation area. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.K.; Fan, J.L.; Xing, Y.Y.; Xu, G.C.; Wang, H.D.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, F.C.; Li, P.; Li, Z.B. The effects of mulch and nitrogen fertilizer on the soil environment of crop plants. Adv. Agron. 2019, 153, 121–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.L.; Li, S.Z.; Zhao, G.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, L.; Dang, Y.; Cheng, W.L. Response of dryland crops to climate change and drought-resistant and water-suitable planting technology: A case of spring maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2067–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, K.; Li, G.L.; Zheng, J.Y. Infiltration holes enhance the deep soil water replenishment from a level ditch on the Loess Plateau of China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 34, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Li, H.J.; Qu, H.C.; Wang, Y.L.; Misselbrook, T.; Li, X.; Jiang, R. Water stress in maize production in the drylands of the Loess Plateau. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 180117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, A.; Lipiec, J.; Gerke, H.H. A review of the changes in the soil pore system due to soil deformation: A hydrodynamic perspective. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 115, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudley, M.W.; Green, T.R.; Ascough, J.C. Tillage effects on soil hydraulic properties in space and time: State of the science. Soil Tillage Res. 2008, 99, 4–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantha, K.H.; Garg, K.K.; Akuraju, V.; Sawargaonkar, G.; Purushothaman, N.K.; Das, B.S.; Singh, R.; Jat, M.L. Sustainable intensification opportunities for Alfisols and Vertisols landscape of the semi-arid tropics. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 284, 108332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ma, J.B.; Ma, Z.H.; Li, G.L.; Zheng, J.Y. Combining infiltration holes and level ditches to enhance the soil water and nutrient pools for semi-arid slope shrubland revegetation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, G.L.; Ma, J.B.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zheng, J.Y. Effect of using an infiltration hole and mulching in fish-scale pits on soil water, nitrogen, and organic matter contents: Evidence from a 4-year field experiment. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4203–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, S.E.; Roulier, S.; Cessna, A.J. Quantifying preferential flow in soil: A review of different techniques. J. Hydrol. 2009, 378, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunek, J.; Jarvis, N.J.; van Genuchten, M.T.; Gardenas, A. Review and comparison of models for describing non-equilibrium and preferential flow and transport in the vadose zone. J. Hydrol. 2003, 272, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Ding, R.S.; Chen, J.L.; Wu, S.Y.; Gao, W.C.; Wen, Z.L.; Tong, L.; Du, T.S. Crop root system phenotyping with high water-use efficiency and its targeted precision regulation: Present and prospect. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 309, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, K.; Duan, C.H.; Li, G.L.; Zhen, Q.; Zheng, J.Y. Evaporation effect of infiltration hole and its comparison with mulching. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 275, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.J.; Tan, W.J.; Hou, H.Z.; Wang, H.L.; Yin, J.D.; Zhang, G.P.; Lei, K.N.; Dong, B.; Qin, A.Z. Effects of deep vertical rotary tillage on soil water use and yield formation of forage maize on semiarid land. Agriculture 2024, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Liu, W.Z.; Xue, Q.W. Spring maize yield, soil water use and water use efficiency under plastic film and straw mulches in the Loess Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2016, 7, 42455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.B.; Zhu, Y.J.; Jia, X.X.; Huang, L.M.; Shao, M.A. Spatial variation and simulation of the bulk density in a deep profile (0–204 m) on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2018, 164, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Q.; Zhu, Q. Response of deep soil moisture to different vegetation types in the Loess Plateau of northern Shannxi, China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Ma, L.; Zhu, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gou, Q.; Shen, M. The variability in soil water storage on the loess hillslopes in China and its estimation. Catena 2019, 172, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.B.; Liu, Z.H.; Rao, W.B.; Jin, B.; Zhang, Y.D. Understanding recharge in soil-groundwater systems in high loess hills on the Loess Plateau using isotopic data. Catena 2017, 156, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, N.J. A review of non-equilibrium water flow and solute transport in soil macropores: Principles, controlling factors and consequences for water quality. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 523–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Linking principles of soil formation and flow regimes. J. Hydrol. 2010, 393, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, C.; Cuezva, S.; Martinez-Martinez, J.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Garcia-Anton, E.; Fusi, N.; Crosta, G.B.; Cuevas-Gonzalez, J.; Canaveras, J.C.; Sanchez-Moral, S. Role of soil pore structure in water infiltration and CO2 exchange between the atmosphere and underground air in the vadose zone: A combined laboratory and field approach. Catena 2017, 149, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.L.; Wu, P.T.; Ga, X.D.; Yao, J.; Zou, Y.F.; Zhao, X.N.; Siddiqu, K.H.M.; Hu, W. Rainwater collection and infiltration (RWCI) systems promote deep soil water and organic carbon restoration in water-limited sloping orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 242, 106400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Y.; Wang, K.; Ma, J.B.; He, H.H.; Liu, Y. Fish-scale pits with infiltration holes enhance water conservation in semi-arid loess soil: Experiments with soil columns, mulching, and simulated rainfall. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2019, 19, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdAllah, A.M.; Mashaheet, A.M.; Burkey, K.O. Super absorbent polymers mitigate drought stress in corn (Zea mays L.) grown under rainfed conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 254, 106946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.C.; Gou, X.H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, D.Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.J. Increasing deep soil water uptake during drought does not indicate higher drought resistance. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hou, X.Y.; Zhang, J.M.; Wang, Y.J.; Hu, M.J.; Jiang, G.S.; Tang, C.S. Exploring the effects of weather-driven dynamics of desiccation cracks on hydrological process of expansive clay slope: Insights from physical model test. J. Hydrol. 2025, 656, 133011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diop, M.; Chirinda, N.; Beniaich, A.; El Gharous, M.; El Mejahed, K. Soil and water conservation in Africa: State of play and potential role in tackling soil degradation and building soil health in agricultural lands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Bao, Z.L.; Smoljan, A.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, H.H.; Friml, J. Foraging for water by MIZ1-mediated antagonism between root gravitropism and hydrotropism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2427315122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Rightsizing root phenotypes for drought resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3279–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Harnessing root architecture to address global challenges. Plant J. 2022, 109, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- York, L.M.; Lynch, J.P. Intensive field phenotyping of maize (Zea mays L.) root crowns identifies phenes and phene integration associated with plant growth and nitrogen acquisition. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 5493–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamombe, S.M.; Nyamadzawo, G.; Oborn, I.; Smucker, A.; Chirinda, N.; Kihara, J.; Nkurunziza, L. Seasonal rainfall patterns affect rainfed maize production more than management of soil moisture and different plant densities on sandy soils of semi-arid regions. Field Crops Res. 2025, 331, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.W.; Wang, Y.C.; Gu, J.; Ma, N.N.; Hou, W.J.; Sun, J.Q.; Fan, X.B.; Yin, G.H. Effects of increasing maize planting density on yield, water productivity and irrigation water productivity in China: A comprehensive meta-analysis incorporating soil and climatic factors. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 317, 109671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, G.; Nakhforoosh, A.; Kaul, H.P. Management of crop water under drought: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 401–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Turner, N.C.; Li, X.G.; Niu, J.Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, L.; Chai, Q. Ridge-furrow mulching systems: An innovative technique for boosting crop productivity in semiarid rain-fed environments. Adv. Agron. 2013, 118, 429–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Richards, R.A. Improvement of crop yield in dry environments: Benchmarks, levels of organisation and the role of nitrogen. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1981–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.Z.; Hao, X.M.; Du, T.S.; Tong, L.; Su, X.L.; Lu, H.N.; Li, X.L.; Huo, Z.L.; Li, S.E.; Ding, R.S. Improving agricultural water productivity to ensure food security in China under changing environment: From research to practice. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 179, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.D.; Yang, L.C.; Xue, X.K.; Kamran, M.; Ahmad, I.; Dong, Z.Y.; Liu, T.N.; Jia, Z.K.; Zhang, P.; Han, Q.F. Plastic film mulching stimulates soil wet-dry alternation and stomatal behavior to improve maize yield and resource use efficiency in a semi-arid region. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Dold, C. Water-use efficiency: Advances and challenges in a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).