Abstract

A comprehensive study was conducted to develop an effective protocol for the clonal micropropagation and subsequent acclimatization of three mint (Mentha) cultivars: ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, ‘Botanicheskaya’, and ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’. This research investigated the influence of nutrient Murashige–Skoog medium composition with the addition of growth regulators (BAP/NAA) on in vitro morphogenesis, as well as the impact of two acclimatization methods to in vivo conditions (direct field planting and a two-stage acclimatization approach) on field performance, yield, and essential oil composition in three mint cultivars. The results revealed a distinct cultivar-specific response. The ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ cultivars showed high efficiency on the BAP/NAA medium and good survival rates with both acclimatization methods. In contrast, the ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ cultivar exhibited pronounced sensitivity to the medium with growth regulators and a low survival rate upon direct planting (40.5%). The two-stage acclimatization method proved critically important for this cultivar, enabling an increase in survival to 68%, as well as improvements in yield, essential oil output, and the restoration of its cultivar-specific linalool profile (59.5% linalool). It was established that, for cost-effective production, an individual selection of technological parameters for each genotype is necessary at all stages of microclonal propagation.

1. Introduction

Mint is widely used both in its raw form and as a raw material in the food, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries [1]. The composition of metabolites in plants of this genus varies significantly between species and between interspecific hybrids and is of interest precisely because of its diversity. The wide range of flavors, textures, and essential oil compositions offers ample opportunities for both pharmacopeia and the food and flavor industries. The genus Mentha is a medicinal and aromatic herbaceous plant used since ancient times [2]. Quantitative ratios of menthol, carvone, linalool and linalyl acetate, which are the main components of mint essential oil, are widely used in food, cosmetics and medicine [3]. In different regions of the world, mint is often popular in traditional folk medicine for its ability to alleviate various health disorders [4,5].

Mentha species vary greatly in height, from 250 mm for pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) to 1540 mm for Mentha × villosa. Leaf length also varies, from 10 mm for pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) to 150 mm for longleaf mint (Mentha longifolia). This also affects yield. For example, Mentha spicata and Mentha × piperita reportedly yield 3.70 and 4.35 kg/ha, respectively, which is significantly higher than Mentha longifolia [6]. A specific concern is the ability to evaluate the productivity of different cultivars, which affects production profitability and the final cost of the product. This issue is often overlooked when comparing and selecting genotypes, forms, or cultivars, resulting in low predictability of economic viability for the producer and, often, seemingly unexpected financial losses. The differences in potential and actual productivity, quantitative indicators of raw material yield and essential oil content are so significant that ignoring them can lead to improper planning and a critical increase in the costs of agricultural enterprises [7]. This is especially important when irrigation or other expensive technologies are required to ensure proper plant growth and development. Accurate estimation of subtle propagation, cultivation, and production issues may justify the higher cost of essential oil obtained from these cultivars for the consumer [8].

Some components of mint essential oil, such as menthol and linalool, give it special value and may predominate in the composition or be completely absent in the composition of certain genotypes. High linalool content gives the essential oil a well-rounded and sophisticated aroma, an excellent safety profile, distinct relaxing properties, and good stability. This unique blend of consumer appeal and therapeutic benefits makes these oils especially and high valuable in quality [9,10]. However, while high-menthol cultivars and hybrids are highly profitable in the field, linalool-containing cultivars, among others, are less productive due to lower biomass yield and produce less essential oil on a dry-weight basis. This is particularly related to the morphological features. First of all, these cultivars often have more hairiness, caused by closely spaced trichomes, and fewer glandular hairs responsible for the accumulation and production of essential oils. Thus, three objective circumstances can be noted that reduce productivity: a decrease in height, a decrease in the number of shoots, and a smaller number of glandular hairs. This issue should be taken into account by manufacturers when calculating and forecasting the final product and its cost.

Furthermore, modern mint varieties, characterized by particularly valuable essential oil compositions, are hybrids and are practically incapable of preserving their qualities when propagated by seeds [11,12]. Hybrids obtained at different times possess unique essential oil compositions, but they cannot be preserved through sexual reproduction either due to impaired anther development (male sterility) [13,14] or due to ploidy imbalances in seed progeny [11,15]. Therefore, various methods of vegetative propagation are used for their multiplication, such as division of the bush, propagation by layering, green cuttings, cryopreservation, and clonal micropropagation [16,17,18]. The latter technology allows for the maintenance of large and unique collections without occupying the space of collection and testing plots in farm nurseries, and reduces the risk of loss of genotypes due to exposure to unfavorable conditions and pathogens [19]. This is especially important for avoiding viral damage, which leads to irreparable loss of a valuable specimen [20]. The use of in vitro technology allows for the maintenance of a collection for a long time at low temperatures [21,22]. Furthermore, clonal micropropagation can provide a farm with the necessary amount of planting material in a short period of time [23,24]. The main issue is that optimal productivity of mint, like other perennial plants, even with vegetative propagation, is achieved in the 2nd or 3rd year [25]. The quantity and quality of essential oil with a given m position are influenced by numerous factors; therefore, it is necessary to consider the properties of each genotype, quantitatively assess its field productivity, and evaluate the essential oil yield per unit area.

Furthermore, we also hypothesize that the propagation coefficient and survival rate of different mint cultivars may vary significantly, as these traits are indirectly linked to the above-mentioned morphological and physiological traits of each cultivar.

The aim of this study is to determine the most effective protocol for in vitro propagation and field acclimatization of various mint genotypes (cultivars), as well as to evaluate their yield and essential oil production. A central premise of this work is that the accuracy of predicting essential oil yield and quality can be significantly enhanced by accounting for genotype-specific characteristics, which is particularly crucial for non-menthol mint cultivars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The plants of three mint species were used in this study: Sakhalin mint M. arvensis var. piperascens L. cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, long-leaved mint M. longifolia var. crispa cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’ and peppermint Mentha × piperita cv ‘Botanicheskaya’. The cultivars were obtained from the collection of the Department of Experimental Biology and Plant Pathology of the Main Botanical Garden (MBG) of the Russian Academy of Sciences and grown on the experimental plot of this department (55.864 N, 37.597 E) (Figure 1 and Figure S1). The mints were kept in a mother nursery with a maximum vegetation period of 3 years. The cultures of mother plants of the collection are renewed annually. The same protocol is used for all plants: they are planted in furrows at a distance of 15 cm from each other with 50 cm between rows.

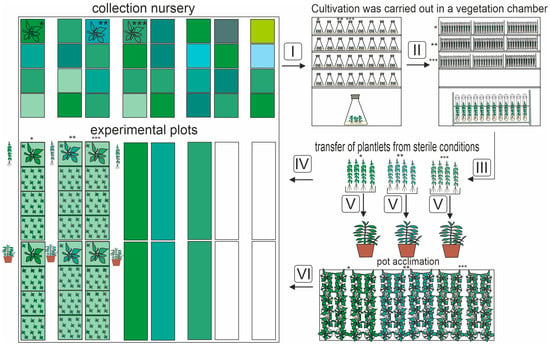

Figure 1.

Methodology for assessing the productivity of three mint genotypes (Figure S1) depending on the acclimatization protocol after clonal micropropagation to predict the yield of essential oil. Four replicates of 12 plants per 1 m2 are used: 3 experimental plots and 1 spare plot (used to replace fallen plants). Stage designations: I—establishment of in vitro culture (includes explant sterilization and cultivation); II—clonal micropropagation to obtain 96 plantlets of each genotype; III—extracting from sterile conditions; IV—planting plantlets in the field without the pre-acclimatization stage; V—planting plantlets in pots and growing them in a greenhouse for preliminary acclimatization (1 month); VI—transplanting plants from pots to field conditions after pre-acclimatization; *—cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’; **—cv ‘Serebryanoe chudo’; and ***—cv ‘Botanicheskaya’.

Cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ (M. arvensis var. piperascens L. (Sakhalin mint)) has a compact, tall, unbranched bush; the stem in the lower part has a red-purple (anthocyanin) color, pubescent; the leaves are deeply serrated, light green with narrow and sharp edges. The flowers are purple, the calyxes are tubular, and the teeth are long, finely pointed [26] (Figure 1 and Figure S1). The characteristic smell and taste of this type of mint is due to the high content of menthol (up to 75–80%) in the essential oil from the above-ground parts (stems, leaves and inflorescences) of the plants.

Cv ‘Serebryanoe chudo’ (M. longifolia var. crispa L.) is a variety of long-leaved mint. The bush is loose, not branched, up to 90 cm high; the stem has a pronounced red-purple (anthocyanin) color, heavily pubescent. The leaves are large, oblong-elliptical, and heavily pubescent. Whorls of light purple flowers are collected in dense spikes [26]. The characteristic floral smell of this variety of mint is due to the high content of linalool (up to 85%) in the essential oil from the above-ground parts (stems, leaves and inflorescences) of the plants (Figure 1).

Cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ (M. × piperita L. (peppermint)) is a highly productive species characterized by a high yield of essential oil. The bush is compact, hemispherical; the plant height is 62–68 cm. The stem has a pronounced red-purple (anthocyanin) color; the leaves are dark green, elliptical, and pubescent. The flowers are purple (Figure 1 and Figure S1). The yields of aboveground mass are 15.0–16.5 t/ha, dry leaf up to 2.5 t/ha. The content of essential oil from the above-ground parts (stems, leaves and inflorescences) of the plants in terms of absolutely dry raw materials is up to 7.0%, menthol in essential oil is 45–60%, and menthone is 10–22%.

A detailed scheme of the experiment for estimating the yield amount of essential oil depending on the productivity of the genotype is shown in the scheme (Figure 1).

2.2. In Vitro Cultivation

The primary cultivation method was the activation of axillary meristem development. Apical and lateral buds from the current year’s shoots, with a small stem section (from the middle part of the stem) containing one node (10–15 mm), were used as explants. A detailed description of the cultivation methodology for these mint cultivars was described previously [27]. Each experimental variant consisted of at least 96 (48 + 48) explants. They were initially treated with 70% ethanol (exposure time: 30 s) and then sterilized with a 4% sodium hypochlorite solution (JSC “VTE Yugo-Vostok,” Moscow, Russia) (exposure time: 5 min) with the addition of 2 drops of Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Sterile explants were planted on growth regulator-free Murashige and Skoog standard nutrient medium (MS) and on the same medium with the addition of growth regulators: BAP (1 mg/L) and NAA (0.5 mg/L). The pH of all media was adjusted to 5.6–5.8. Agar (0.8% w/v) was added to media. The media were sterilized by autoclaving (2540EKA, Tuttnauer, Beit Shemesh, Israel) at 121 °C for 20 min.

Cultivation was carried out in a dedicated room at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C, with a photoperiod of 16 h of light (2500–3000 lux)/8 h of darkness, and a humidity level of 70%. The experiment was conducted with five replications. After four weeks of cultivation, the following morphometric parameters were determined: shoot length (mm), number of internodes, average width of 5 leaves from the middle tier (mm), root length (mm), number of stolons, stolon length (mm), number of lateral shoots, lateral shoot length (mm), and the weight of 10 plants (g). We used three biological replicates of 12 plants each and included an additional set of reserve plants in case of losses, for a total of 48 plants per variety. These 48 plants were selected from the initial sets of 96 plants of both acclimated in pots and nonacclimated plants (Figure 1 and Figure S2).

2.3. Acclimatization Stage to In Vivo Conditions

Four-week microcloned plantlets obtained from the explants were used for acclimatization. Two strategies were used for plantlet acclimatization to in vivo conditions. Cotton plugs were removed from some of the culture tubes where mint plants were growing to allow for acclimatization and normal stomatal functioning in these rooted plantlets, and in this form the plants were adapted to non-sterile conditions for three days (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The plants were then removed from the test-tubes, their roots were rinsed with water to remove residual agar, and directly planted in the experimental plots in the field.

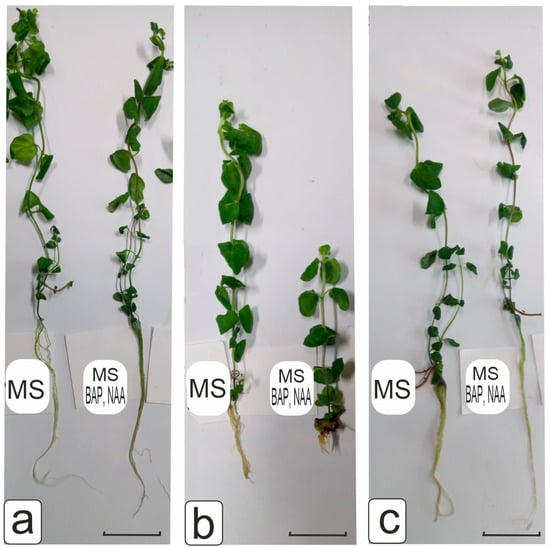

Figure 2.

Appearance of plants of three mint cultivars ((a)—M. arvensis var. piperascens L. cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’; (b)—M. longifolia var. crispa cv ‘Serebryannoye chudo’; (c)—M. × piperita cv ‘Botanicheskaya’) in vitro cultivation variants on regulator-free MS medium and MS medium with growth regulators (BAP/NAA). Bar 10 mm.

Another group of mint plants was removed from the culture tubes, their roots were also rinsed with water to remove residual agar, and they were planted in pots with pre-sterilized substrate. This represented a two-stage acclimatization method: preliminary cultivation in greenhouse conditions in pots followed by transplanting to the field (greenhouse pre-acclimatized plants) (Figure 1 and Figure S2).

The plants were acclimatized at 23 ± 2 °C with a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark at a light intensity of 160 μM photons m−2 s−1 and a humidity level of 70% for 4 weeks, after which they were planted in open field in the experimental plot.

Each experimental variant consisted of at least 96 explants (from 48 plants without pre-acclimatization and 48 acclimatized plants).

2.4. In Vivo Cultivation

The plants were cultivated in the field under natural illumination on the experimental plots. The plot soil was sod-podzolic, cultivated; pH 5.8–6.0; humus content 6.4%; sand content 18.0%. We used a traditional plant spacing scheme—50 cm between rows, 20–25 cm between plants in a row (a planting rate of up to 60,000 plants per hectare). Four replicates of 12 plants per 1 m2 were used. During the budding phase, yield and essential oil yield were measured (Figures S1 and S2).

Weeding and loosening were carried out once every two weeks, starting from the time of planting. Fertilizing was carried out once a month after weeding at the rate of 3.5 g of complex nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium fertilizer per 1 L of water per plant. During the budding phase, yield and essential oil yield were measured. The harvesting of raw materials was performed by cutting off all the above-ground mass located above 5–6 cm from the ground. The plants were formed into sheaves for further drying, extraction of essential oil and analysis of its qualitative composition. The sheaves were dried in a ventilated dark place for 5 days. After drying, the raw materials were stored in craft bags until the oil began to be extracted.

2.5. Determination of Essential Oil in Mint Plants

The air-dried above-ground part (inflorescences, leaves and stems) of the plants was crushed manually immediately before essential oil extraction (Figures S1 and S2). Flasks with mint samples were subjected to hydrodistillation for 2 h in accordance with the standard procedure described earlier [28]. Essential oils were stored in the dark until analysis.

The qualitative composition of the oil was determined by gas chromatography at the Collective Use Center of the Federal Research Center “Biotechnology” of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RFMEFI62114X0002) using a Shimadzu GC-MS QP 2010 Ultra EI gas chromatograph with a GCMS-QP 2010 mass detector (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). A detailed description of the chromatography conditions was described previously [28].

2.6. Determining the Productivity of Genotypes to Calculate Product Yield

To determine the productivity of genotypes, an additional experimental plot was established with a traditional planting scheme for plants obtained by planting acclimatized plants using traditional technology. At the end of April 2025, 12 pre-adapted in pots (9 cm × 9 cm) plants of each cultivar were planted per 1 square meter on the territory of the collection area of the MBG, and the same number was planted in the open ground without acclimatization, shading the area with lutrasil for 10 days.

Each experimental variant consisted of at least 96 explants (from 48 plants without pre-acclimatization and 48 pots acclimatized) (Figure 1 and Figure S2). The plants were watered immediately upon planting and then twice a month at the rate of 1 L per plant during May–July. In early September, the plants were cut at the base of the root. After this, the plant height, leaf size, wet and air-dry biomass was recorded. A portion of the plants without foliage was removed before drying, amounting to 7 to 12 cm. Drying was carried out in a warm, shaded place until air-dry. Next, the raw material was crushed to a fraction of 0.3–0.7 cm, and the essential oil was obtained (with preliminary weighing of an equal amount of raw material) by the hydrodistillation method as described above. The obtained data were used to evaluate the predicted efficiency of clonal micropropagation and to determine the productivity of the studied samples. For the calculations, it was taken into account that the mint planting rate per hectare depends on the propagation method, which is approximately 120,000 plants per hectare to ensure normal planting density.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean.

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

The statistical data processing was performed in the PAleontological STatistics Version 4.10 (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway) environment [29]. Since the data met the assumption of normality, a parametric approach was applied. The data were processed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When the assumption of homogeneity of variances (tested by Levene’s test) was violated, Welch’s ANOVA was used. For pairwise comparisons of groups, the Tukey HSD post hoc test was applied. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The results of this study on the effect of nutrient medium composition on the morphogenesis of three mint cultivars under in vitro conditions demonstrate a distinct cultivar-specific response to its composition (Table 1). The MS with growth regulators has a divergent effect: while it stimulates the development of the root system in the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’, the same medium acts as an inhibitory factor for the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’, causing a sharp suppression of growth processes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average values of morphometric parameters of cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ and cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ microshoots at the proliferation stage after four weeks of in vitro cultivation on MS with and without growth regulators.

The cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ exhibits the greatest performance, showing high shoot length values (18.7 cm on regulator-free MS medium) and active stolon formation. On the MS with growth regulators, this cultivar shows improved root system development (an increase in root length from 10.5 to 12.7 cm) while maintaining satisfactory biomass indicators. Statistical analysis using Welch’s ANOVA (Welch F test) revealed no significant differences between the regulator-free MS medium and the MS medium with regulators, F(22.39) = 0.0433, p = 0.99.

The cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ also shows optimal results precisely on the MS medium with regulators, where it reaches maximum values for biomass (6.39 g) and root length (12.8 cm). Although this indicates a positive response of this genotype to cytokinin–auxin stimulation, the differences between the medium variants are not statistically significant (F(15.95) = 0.0045, p = 0.95).

In contrast, the cv ‘Serebryannoe Chudo’ exhibits a pronounced sensitivity to the MS medium with growth regulators, showing a sharp decrease in all studied parameters: shoot length decreased from 14.8 to 9.2 cm, stolon formation ceased completely, and biomass is reduced by 33%. This reaction indicated the necessity for developing a specialized micropropagation protocol for this particular cultivar. Statistical analysis using Welch’s ANOVA (Welch F test) revealed significant differences between the regulator-free MS medium and the MS medium with regulators, F(18.10) = 3.98, p = 0.04.

The obtained data confirm the importance of an individualized selection of the nutrient medium composition for each genotype during the clonal micropropagation of mint, which is a key factor in optimizing the technology for producing healthy planting material.

The propagation coefficient of the three studied mint cultivars also revealed cultivar-specific differences when using different nutrient media. The cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ exhibited high and stable propagation efficiency on both media, showing coefficients of 11.7 on the growth regulator-free MS medium and 12.4 on the MS with growth regulators. The slight increase in the indicator on the medium with the growth regulator indicates good adaptability of this cultivar.

The most pronounced positive response to growth regulators was demonstrated by the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’, whose propagation coefficient increased from 10.8 to 12.4 when using MS with growth regulators. This indicates that this particular medium is optimal for the effective clonal micropropagation of this cultivar.

In contrast to the previous genotypes, the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ exhibited a pronounced sensitivity to the MS medium with growth regulators. Its propagation coefficient decreased from 6.5 on the standard MS medium to 4.8 on the MS medium with growth regulators, confirming the negative impact of the applied hormonal composition on the morphogenesis processes in this cultivar.

Comparative analysis revealed an almost threefold difference in propagation efficiency between the best (12.4 for the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ on MS with growth regulators) and the worst (4.8 for ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ on MS with regulators) variants. Such significant differences are critically important for the economic efficiency of planting material production.

The obtained results confirm the necessity of individual selection of in vitro conditions for each mint cultivar. For industrial application, the most promising are the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ on the MS medium with regulators, while, for the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’, the development of an alternative micropropagation protocol with a specialized hormonal composition is required.

Plants of three mint cultivars, propagated in vitro, were acclimatized to in vivo conditions using two methods. Both methods proved effective for the menthol-rich cultivars ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ (Figure 2).

During direct planting of rooted plantlets into field conditions, the survival rate of ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ was 83%, while that of ‘Botanicheskaya’ was 90% (Figure 3). When using the two-stage acclimatization method with preliminary cultivation under greenhouse conditions in a pot culture followed by transplantation to the field, this indicator was higher: the survival rate of ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and that of ‘Botanicheskaya’ increased by 7 and 5%. No significant differences were recorded between the two acclimatization methods for the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ (F(4.01) = 0.252, p = 0.055 and F(3.45) = 0.212, p = 0.059, respectively).

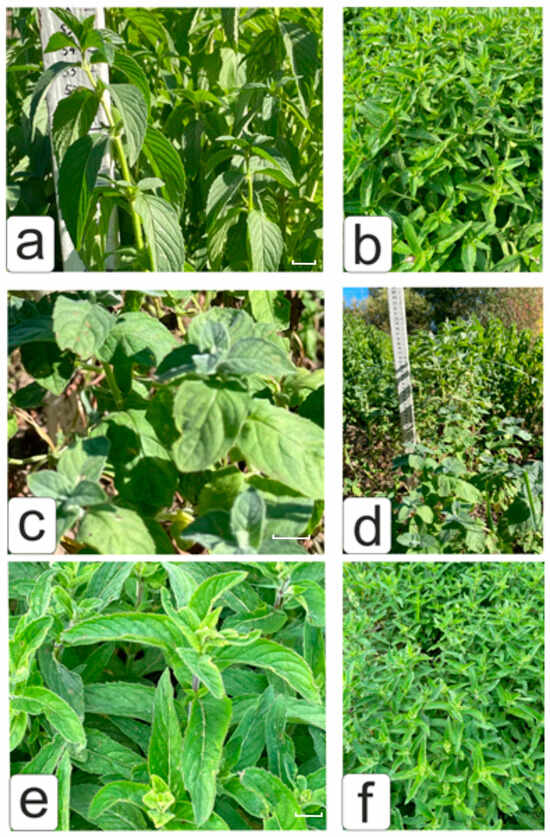

Figure 3.

Appearance of mint cultivars ((a,b)—M. arvensis var. piperascens L. cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’; (c,d)—M. longifolia var. crispa cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’; (e,f)—M. × piperita cv ‘Botanicheskaya’) in field conditions after direct planting of in vitro rooted regenerants in field conditions. Bar 10 mm.

In contrast to the menthol-rich cultivars, the linalool-type cultivar ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ demonstrated significantly lower effectiveness. During direct planting in field, the survival rate of rooted plantlets was only 40.5%. Although the greenhouse pre-acclimatization method increased this rate to 68%, the data indicate statistically significant differences between the two acclimatization methods: F(25.8) = 3.26, p = 0.0032. However, the survival rate of the cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ remained substantially lower than that of the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’.

The budding phase began for the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’ in the second ten-day period of August, while, for the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, it began in the third ten-day period of August (after 74 days).

The green mass yield of the ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ cultivar was the highest both when directly planted in the field and after greenhouse pre-acclimatization, ranging from 410.5 to 501.0 g/m2. No significant differences between these experimental variants were recorded (F(5.78) = 0.033, p = 0.862). The yield of the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ was 3–4% lower, and that of the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ was 24–26% lower than that of the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, accordingly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Yield and essential oil content of M. arvensis var. piperascens L. cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, M. longifolia var. crispa cv ‘Serebryannoye chudo’ and M. × piperita cv ‘Botanicheskaya’.

At the same time, no significant differences in yield were found between the cultivars ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’, either after direct planting in the field or after greenhouse pre-acclimation. No significant differences in yield were found between the cultivars ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’, either after direct planting in the field or after greenhouse pre-acclimation. The essential oil content in the green biomass of the mint cultivars ‘Botanicheskaya’ and ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ did not statistically differ significantly when directly planted in the field. In greenhouse pre-acclimatized plants of the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’, the oil content was 1.26 times higher (Table 2). The essential oil yield in plants of these cultivars directly planted in the field did not differ statistically significantly, whereas it did differ statistically significantly in greenhouse pre-acclimatized plants—Welch’s ANOVA did not reveal differences between these experimental variants, F(6.64) = 0.019, p = 0.996.

The cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ demonstrated higher productivity after greenhouse pre-acclimation than after direct planting in the field: the yield and essential oil content were observed in the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ plants when directly planted in the field, while, in greenhouse pre-acclimatized plants, these indicators increased by 1.35 and 1.62 times, respectively. The obtained data indicate the presence of statistically significant differences between the experimental variants—F(15.78) = 3.31, p = 0.048.

Up to 60 components were found in the essential oil of three mint cultivars; all components with a content of more than 0.1% of the total amount were easily identified by retention time and mass spectra. The obtained essential oil of menthol mint cultivars complies with the recommendations of the national standards GOST ISO 31791-2017 and GOST ISO 9776-2017 [30,31]. The essential oil of the cv Pamyati Kirichenko crystallized at room temperature, and menthol was dominant in its composition (Table 3). And if in the collection plants (parent forms), menthol content in different years of observation was 40.3–62.8%; then, in the essential oil of plants directly planted in the field, it was 40.8%, and, in greenhouse pre-acclimatized plants, it increased to 52.6%. Menthone, menthol and menthyl acetate in the essential oil of cv Botanicheskaya plants were dominant. The content of the first two compounds in the essential oil of mint plants, both directly planted in the field and greenhouse pre-acclimatized, was at the same level as that of the collection plants. The menthyl acetate content in the essential oil of in vitro regenerated plants, then directly planted in the field, and greenhouse pre-acclimatized was 3.5 times higher than that of the collection mother plants.

Table 3.

Variation in the main components of the essential oil of three cultivars of mint (M. arvensis var. piperascens L. cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’, M. longifolia var. crispa cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’ and M. × piperita cv ‘Botanicheskaya’) as affected by the acclimatization method, %.

Plants of the cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ synthesize mainly acyclic compounds, while the essential oil of collection plants is practically monocomponent, and the content of linalool in it in some years reaches 80%. For in vitro propagated plants of this variety, the composition of the essential oil has changed, the proportion of sabinene, limonene, 1,8-Cineol, α-terpineol and germacrene D has increased. The mass fraction of linalool has significantly decreased—by 40% with direct planting of plantlets in the field but has increased due to two-stage acclimatization method of greenhouse pre-acclimatized plantlets—up to 59.5%.

Modeling of the field productivity of the studied samples revealed that different samples differ significantly in biomass, weight of the obtained raw materials, and even more so, in the amount of essential oil obtained from the raw materials. The cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ demonstrated the highest productivity across all indicators, significantly exceeding the indicators of the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’, both when using adaptation and when planted directly into the field. The cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’, with a high linalool content, is of interest for obtaining valuable essential oil with a delicate floral aroma but requires a significantly larger (more than an order of magnitude) area to obtain the same volume of essential oil. This is probably due to the fact that the height of the cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’ plants is lower, and the number of stems per plant is almost half as much. The leaf length of the cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’ is on average shorter than that of the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and only slightly shorter than that of the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ (Figure 3). In addition, the survival rate of the cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ was significantly lower than that of the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’.

The evaluation of the field performance of two acclimatization methods for microclonal plants of the three studied mint cultivars revealed that the cultivars differed in yield and essential oil production (Figures S3–S7). While greenhouse pre-acclimatization of mint plants was optimal for maximizing yield and standardizing quality, direct planting into the field offered specific advantages. Thus, for resistant varieties with high menthol content, it is a cost-effective alternative that delivers a good commercial result. Furthermore, for the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’, it is a way to obtain essential oil with a pronounced emphasis on menthyl acetate.

4. Discussion

For the cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’, the advantages of the greenhouse pre-acclimatization method are fundamental and decisive for its successful commercial use. This method ensures a radical increase in survival rate and, consequently, a significant growth in yield, an improvement in raw material quality, and the highest gain in essential oil output, which made the cultivation of this cultivar economically viable. This greenhouse pre-acclimatization method stabilized the biosynthesis and allowed for the restoration of the cultivar-specific profile, raising the linalool content to 59.5%. This guarantees the production of essential oil with a predictable, high-quality, and marketable aroma. For the ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ cultivar, the greenhouse pre-acclimatization method is not merely an effective agricultural technique but a necessary precondition for its profitable cultivation and the production of high-quality essential oil that corresponds to its declared chemotype. Without this method, the cultivar exhibits low viability and loses its main value—high linalool content.

The inclusion of menthol mint cultivars in the in vitro culture system presents no particular problems; the regenerative potential of nodal fragments exceeds that of shoot apical explants [32,33]. Our results are consistent with our previous data and those of other authors, which indicate that the most optimal medium for micropropagation of the studied cultivars of the three mint species is MS medium supplemented with cytokinin BAP [34,35,36]. Similar results of BAP efficacy were also recorded for other Mentha species [37]. The synthetic growth regulators BAP and NAA used in this study are analogs of natural cytokines and auxins, widely used in in vitro culture.

Synthetic phytoregulators can alter the composition of essential oils by changing the ratio of various components, significantly altering the odor character by changing the concentration of linalool, limonene, and other terpenoids, and modulating the biological activity of the essential oil [38]. The effects of these preparations, included in many in vitro culture protocols, vary due to their nature, mimicking natural processes in plant tissues and cells [39]. The long-term consequences of this “tandem” effect of these two synthetic phytohormones are listed in the table and, in our opinion, should be considered when used in colonial micropropagation technology, at least for essential oil crops (link to table).

The explanation for the observed effects is likely related to the fact that cytokinins, acting on mature mesophyll, vascular, and other tissues, are capable of long-term modulation of metabolite production through modification of gene expression [40]. It can be hypothesized that, without the use of BAP, auxins could have caused an “accelerating” modification of secondary metabolites, the consequences of which require further study. Addition of NAA auxin to the MS medium resulted in a slight increase in root length only in the cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ of the Sakhalin mint (M. arvensis var. piperascens) and a significant decrease in root length and all other morphological parameters in the cv ‘Serebryanoye chudo’ of the long-leaved mint (M. longifolia var. crispa). We previously noted spontaneous root formation in peppermint cultivars on a propagation medium, without additional treatment with auxin to induce rooting [28]. The same effect was also recorded in the cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ of peppermint. This advantage of in vitro multiplication of the studied cultivars of three mint species reduces the cost and time for obtaining planting material for propagation by at least four weeks.

We observed a slight decrease in menthol accumulation in samples obtained from plants without pre-adaptation in pots, which may be due to the residual effect of BAP. However, it is also possible that this is due to another, as yet unidentified, reason. This will likely be clarified by conducting targeted experiments testing the effect of other cytokinins. The in vitro effects of growth regulators on various mint genotypes can affect growth and development, morphology, composition, and ratios of individual essential oil components [38]. This is due to the direct and indirect consequences of these effects, as they can alter both primary and secondary metabolism [13,38,41]. In the former case, growth regulators influence the plant signaling system, causing reversible modifications of growth, photosynthesis, and sugar and hormone transport [41]. In the latter case, growth regulators, being relatively small molecules, can penetrate various cellular compartments, including the nucleus, causing modification of the genetic apparatus. This leads to changes in gene expression that ensure a long-term effect, and in the case of modification of DNA and/or proteins associated with the regulation or packaging of chromatin, to long-lasting effects at the epigenetic level, persisting for a relatively long time [42]. Although such rearrangements can significantly affect the phenotype, they are not always transmitted to sexual or even vegetative offspring. Most epigenetic modifications can be “canceled” by stress factors, as well as by a series of meiotic divisions [43]. In the case of vegetatively propagated crops, which include a large number of valuable mint genotypes, the use of hormone-like regulators requires caution [44]. An effect on the composition of essential oil components may be observed, but this effect disappears over time, presumably as a result of metabolic modification after the dormant period [28]. In the present study, we observed the combined effects of propagation method, acclimatization, and growth regulators. We believe that these modifications of essential oil composition, in the analysis of which we were interested, are the most valuable components determining the value of the essential oil composition-menthol and linalool [45]. The synthesis of secondary metabolites is a process dependent on stressful conditions often accompanying mint cultivation, such as drought, high temperatures, excess ultraviolet radiation, etc. [46]. Synthetic hormone-like compounds and natural hormones can also significantly influence the biosynthesis and subsequent enzymatic transformations of essential oil components [38]. It is advisable to control these processes to prevent negative effects, such as those associated with the formation of pulegone, which has some toxicity [47].

We believe that the proposed method for planting mint seedlings obtained in vitro could be used in regions with a limited growing season, such as mountainous areas and at higher latitudes, expanding the areas available for this plant to grow [48].

Two tested methods for acclimatization in vitro regenerated mint seedlings to in vivo cultivation showed that, for menthol mint cultivars, both direct planting of rooted plantlets in the field and greenhouse pre-acclimatization of rooted plantlets in pot culture (traditional technology) followed by their planting in the field are suitable. The high survival rate of peppermint seedlings propagated in vitro and adapted using traditional technology has been noted by several authors [34,36]. However, the relatively high survival rate of rooted shoots of menthol mint cultivars we observed when directly planted in the field conditions has not been previously observed. Therefore, for these cultivars, this adaptation method also offers advantages in terms of cost and time savings for planting material production. For the linalool cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ of long-leaved mint, the traditional method of adaptation remains optimal, since the survival rate of in vitro regenerated mint seedlings was significantly higher than when directly planted in the field. This result can probably be explained by differences in the structure of the stem, which determines more or less rapid root regeneration. Lower viability of explants of linalool mint cultivars compared to menthol mint cultivars was also noted previously [35].

According to other authors, even after three and four cycles of in vitro preservation, the menthol and linalool chemotypes of mint are characterized by genetic stability: complete correspondence (length and number of amplicons) of the profiles of regenerated and parental samples according to ISSR primers was recorded [21,35,49].

The composition of the essential oil from in vitro regenerants is restored to the parental forms 100–120 days after the transfer of plants to field conditions, but mint plants in the second year of vegetation are considered to be the most productive in terms of the yield of produced essential oil and the mass fraction of major components in it [50,51]. A comparative assessment of the major components of the essential oil of menthol mint cultivars adapted in two ways showed a decrease in the main component of the oil, menthol, compared to collection plants, but the proportion of menthone and menthyl acetate in the oil composition increased. In the biosynthesis of monoterpenes of the genus Mentha, menthyl acetate is a precursor of menthone, and menthone is a precursor of menthol [51]. And although the accumulation of these compounds as the main component of the essential oil indicates suboptimal functioning of the reducing enzymes that catalyze the conversion of menthyl acetate into menthone and subsequently into menthol, it should be expected that, in the second year of vegetation of these mint cultivars, the component composition of the oil will be similar to the collection plants. It should be noted that the reduction in the time of in vitro propagation of menthol mint cultivars led to the absence of menthofuran in the composition of the essential oil, which is quite often recorded by other researchers [52]. In vitro regenerated linalool from the cv ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ mint, adapted using traditional methods, although the linalool content was lower than that of the collection plants, the mass percentage of this component was 60%. Such a high content of the main essential oil component provides a significant advantage to the planting material of this variety and makes it highly sought after [53,54].

Differences between cultivars predictably lead to differences in their productivity: for example, cultivars with high menthol content (‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’) demonstrated higher productivity than the ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ variety. Therefore, the obtained results indicate that the two-stage acclimatization method is absolutely necessary for microclonal plants of the linalool-rich ‘Serebryanoye Chudo’ variety, as it provides a comprehensive positive effect on both agronomic performance and the biochemical characteristics of the essential oil. This study demonstrates that a preliminary assessment of the genotype and production technology at a specific farm should serve as a benchmark for adjusting calculations, even when working with a well-known plant species.

Differences between cultivars predictably lead to differences in their productivity, so the cultivars high in menthol (‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ and ‘Botanicheskaya’) had higher productivity than the cv ‘Serebryannoye Chudo’. Therefore, the results indicate that producing the same amount of essential oil with high linalool content (cv ‘Serebryannoye Chudo’) will require 1.5 or more times as many cloned plants and more than 19 times as much area. Thus, taking all costs into account, it can be assumed that producing equal quantities of essential oil will require at least 28.5 times more investment, which will impact the price of the product and should be taken into account when making production decisions. This study demonstrates that a preliminary assessment of the genotype and production technology at an individual farm should serve as a standard for adjusting calculations, even when dealing with a well-known plant species.

5. Conclusions

At the in vitro propagation stage, the mint cultivars exhibited different responses to the nutrient medium composition. Cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ demonstrated stability, ‘Botanicheskaya’ showed optimal results on the medium with the addition of growth regulators (BAP/NAA), whereas, for cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’, this medium was inhibitory, indicating the necessity of developing a specialized protocol.

This study successfully identified distinct, optimal cultivation strategies for each mint cultivar, underscoring the necessity of a genotype-specific approach. Cv ‘Pamyati Kirichenko’ emerged as a highly reliable cultivar, demonstrating consistent performance on the BAP/NAA medium in vitro and successful adaptation under both acclimatization methods. This robustness offers producers valuable flexibility, allowing them to choose between the more economical direct planting method and the higher-yielding two-stage strategy based on their specific resources and production goals.

Cv ‘Botanicheskaya’ proved to be the most responsive to in vitro stimulation by growth regulators. Its cultivation strategy can be tailored to target specific product outcomes: the method of direct planting in field conditions is optimal for producing an essential oil with a uniquely high concentration of menthyl acetate, whereas the method with greenhouse pre-acclimatization is superior for maximizing the total volume of essential oil produced.

Conversely, cv ‘Serebryanoe Chudo’ was the most demanding cultivar, with its successful commercial cultivation being entirely contingent upon the use of the greenhouse pre-acclimatization method. This protocol is crucial, as it ensures acceptable survival rates and yield. Furthermore, it stabilizes the biosynthetic pathway, ensuring the production of high-quality essential oil with a linalool content consistent with its declared chemotype.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122870/s1, Figure S1: Mother plants of mint in a collection nursery.; Figure S2: Scheme of obtaining essential oil; Figure S3: The effect of the acclimatization method of regenerated plantlets on phenotypic features of the morphology of aboveground organs of three mint cultivars title; Figure S4: The effect of the method of acclimatization of regenerated plantlets on the production of green biomass in three mint cultivars; Figure S5: The effect of the acclimatization method of regenerated plants on the amount of essential oil obtained from one plant in three mint varieties; Figure S6: The effect of the acclimatization method of regenerated plants on the area required to obtain 1 L of essential oil; and Figure S7: The effect of acclimatization method of in vitro regenerants on the number of plants required to produce 1 L of essential oil in three mint cultivars.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.V.S. and E.N.B.; methodology, O.V.S., N.O.Y. and E.N.B.; validation, O.V.S. and A.A.G.; formal analysis, N.O.Y., L.S.O. and L.N.K.; investigation, O.V.S., N.O.Y., A.A.G., L.S.O., L.N.K. and E.N.B.; resources, O.V.S., N.O.Y. and A.A.G.; data curation, O.V.S., N.O.Y. and E.N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.V.S., A.A.G. and E.N.B.; writing—review and editing, A.A.G. and E.N.B.; visualization, A.A.G. and E.N.B.; project administration, E.N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financially supported within the state assignments of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation themes No. FGUM-2025-0003 (ARRIAB: E.N.B., A.A.G.), 124030100058-4 (MBG RAS: O.V.S., L.N.K., L.S.O., E.N.B.), and No. 122042600086-7 (IPP; N.O.Y.). APC for open access is paid from the personal funds of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lawrence, B.M. Mint. The Genus Mentha; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, H.A. Descriptive overview of the medical uses given to Mentha aromatic herbs throughout history. Biology 2020, 9, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafrihi, M.; Imran, M.; Tufail, T.; Gondal, T.A.; Caruso, G.; Sharma, S.; Atanassova, M.; Atanassov, L.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Pezzani, R. The wonderful activities of the genus Mentha: Not only antioxidant properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Stojanovic-Radic, Z.; Matejic, J.; Sharopov, F.; Antolak, H.; Kregiel, D.; Sen, S.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Acharya, K.; Sharifi-Rad, R.; et al. Plants of genus Mentha: From farm to food factory. Plants 2018, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, A.; Iraji, A.; Esmaealzadeh, N.; Salehi, M.; Hashempur, M.H. Peppermint and menthol: A review on their biochemistry, pharmacological activities, clinical applications, and safety considerations. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 1553–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil, M. The effect of different planting times on yield and quality features in some mint species (Mentha longifolia, Mentha × piperita, Mentha spicata). Emir. J. Food Agric. 2021, 33, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothe, N.B.; Mazeed, A.; Pandey, J.; Patairiya, V.; Verma, K.; Semwal, M.; Verma, R.S.; Verma, R.K. Maximizing yields and economics by supplementing additional nutrients for commercially grown menthol mint (Mentha arvensis L.) cultivars. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 160, 113110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar, A.S.; Buttar, G.S.; Singh, M.; Singh, S.; Vashist, K.K. Improving bio-physical and economic water productivity of menthol mint (Mentha arvensis L.) through drip fertigation. Irrig. Sci. 2021, 39, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, F.A.; Mushtaq, A. The five most traded compounds worldwide: Importance, opportunities, and risks. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2023, 23, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Cao, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, J. Diversity and profiles of volatile compounds in twenty-five peppermint genotypes grown in China. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 1472–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippes, N.; Tsai, H.; Lieberman, M.; Culp, D.; McCormack, B.; Wilson, R.G.; Dowd, E.; Comai, L.; Henry, I.M. Diploid mint (M. longifolia) can produce spearmint type oil with a high yield potential. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.; Gupta, A.; Singh, V.; Kumar, B. Impact of induced mutation-derived genetic variability, genotype and varieties for quantitative and qualitative traits in Mentha species. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2024, 100, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghini, H.; Sabzalian, M.R.; Rahimmalek, M.; Garavand, T.; Maleki, A.; Mirlohi, A. Seed set in inter specific crosses of male sterile Mentha spicata with M. longifolia. Euphytica 2020, 55, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, K.J.; Hummer, K.E.; Bassil, N.V.; Lange, B.M.; Khoury, C.K.; Carver, D. Crop wild relatives as germplasm resource for cultivar improvement in mint (Mentha L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vining, K.J.; Pandelova, I.; Hummer, K.E.; Bassil, N.V.; Contreras, R.; Neill, K.; Chen, H.; Parrish, A.N.; Lange, B.M. Genetic diversity survey of Mentha aquatica L. and Mentha suaveolens Ehrh., mint crop ancestors. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, R.; Singh, A.K.; Verma, K.; Singh, K.P.; Nilofer; Kumar, A.; Parminder, K.; Singh, A.; Pandey, J.; et al. Influence of planting methods on production of suckers (rhizome or propagative material), essential oil yield, and quality of menthol mint (Mentha arvensis L.). Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2020, 9, 3675–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triharyanto, E.; Pujiasmanto, B.; Pardono, P.; Fa’izah, A.T. Response of growth and yield of mint (Mentha spicata) cuttings to auxin and composition of planting media. Agrotechnol. Res. J. 2023, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreckel, H.D.; Samuels, F.M.; Bonnart, R.; Volk, G.M.; Stich, D.G.; Levinger, N.E. Tracking permeation of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in Mentha × piperita shoot tips using coherent Raman microscopy. Plants 2023, 12, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutsol, T.; Priss, O.; Kiurcheva, L.; Serdiuk, M.; Panasiewicz, K.; Jakubus, M.; Barabasz, W.; Furyk-Grabowska, K.; Kukharets, M. Mint plants (Mentha) as a promising source of biologically active substances to combat hidden hunger. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Singh, H.; Pandey, R.; Samad, A.; Patra, N.; Kumar, S. Diseases in mint: Causal organisms, distribution, and control measures. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2005, 11, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Senula, A.; Gonzalez, I.; Acosta, A.; Keller, E.R.J.; Gonzalez-Benito, M.E. Genetic identity of three mint accessions stored by different conservation procedures: Field collection, in vitro and cryopreservation. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Cremer, C.; Gonzalez, I.; Gonzalez-Benito, M.E. Influence of the cryopreservation technique, recovery medium and genotype on genetic stability of mint cryopreserved shoot tips. Plant Cell Tissue Org. Cult. 2015, 122, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.; Bartos, P.; Martins, A.; Oliveira, S.; Schewinski-Pereira, J. Assessment of mint (Mentha spp.) species for large-scale production of plantlets by micropropagation. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2015, 37, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyczko, J.; Piotrowski, K.; Kolasa, K.; Galek, R.; Szumny, A. Mentha piperita L. micropropagation and the potential influence of plant growth regulators on volatile organic compound composition. Molecules 2020, 25, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltanbeigi, A.; Özgüven, M. Influence of planting date on growth, yield, and volatile oil of menthol mint (Mentha arvensis) under marginal land conditions. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2021, 24, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Commission of the Russian Federation for Testing and Protection of Selection Achievements (FSBI “Gossortkomissiya”). Available online: https://gossortrf.ru/registry/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Shelepova, O.V.; Konovalova, L.N.; Baranova, E.N.; Dilovarova, T.A. Comparison of the chemical composition of essential oils of two species of Mentha L., propagated in vitro and in vivo. Biotechnology 2023, 39, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shelepova, O.V.; Dilovarova, T.A.; Gulevich, A.A.; Olekhnovich, L.S.; Shirokova, A.V.; Ushakova, I.T.; Zhuravleva, E.V.; Konovalova, L.N.; Baranova, E.N. Chemical components and biological activities of essential oils of Mentha × piperita L. from field-grown and field-acclimated after in vitro propagation plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- GOST ISO 31791-2017; Essential Oils and Floral-Herbaceous Essential Oil Raw Materials. Technical Conditions. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2017; pp. 1–28.

- GOST ISO 9776-2017; Essential Oil of Cornmint (Mentha arvensis), Partially Dementholized (Mentha arvensis L. var. piperascens Malinv. and var. glabrata Holmes). Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2017; pp. 1–16.

- Khan, S.; Shende, S.M.; Bonde, D.R. In vitro micropropagation of mint (Mentha). World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 10, 1688–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Shelepova, O.V.; Olekhnovich, L.S.; Konovalova, L.N.; Khusnetdinova, T.I.; Gulevich, A.A.; Baranova, E.N. Assessment of essential oil yield in three mint species in the climatic conditions of Central Russia. Agron. Res. 2021, 19, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya, B.N.; Asanakunov, B.; Shahin, L.; Jernigan, H.L.; Joshee, N.; Dhekney, S.A. Improving micro-propagation of Mentha × piperita L. using a liquid culture system. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2019, 55, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorskaya, M.S.; Abdurashytov, S.F. Genetic identity of mint cultivars after in vitro conservation, assessed by ISSR primers. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 937, 042014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomir, A.M.; Stan, R.; Pandelea, M.L.; Vizitiu, D.E. In vitro multiplication of Mentha piperita L. and comparative evaluation of some biochemical compounds in plants regenerated by micropropagation and conventional method. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2022, 21, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorskaya, M.S.; Yegorova, N.A. Optimization of the nutrient medium composition for the clonal micropropagation in vitro mint cultivars Azhurnaya and Bergamotnaya. Sci. Notes V.I. Vernadsky CFU Biol. Chem. 2018, 70, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Paric, A.; Karalija, E.; Jasmina, C. Growth, secondary metabolites production, antioxidative and antimicrobial activity of mint under the influence of plant growth regulators. Acta Biol. Szeged. 2017, 61, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Agudelo-Morales, C.E.; Lerma, T.A.; Martinez, J.M.; Palencia, M.; Combatt, E.M. Phytohormones and plant growth regulators—A review. J. Sci. Technol. Appl. 2021, 10, 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaldari, I.; Afshoon, E.; Nik, S.H. Phytohormonal elicitation triggers oxidative stress and enhances menthol biosynthesis through modulation of key pathway genes in Mentha piperita L. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, D.; Mohammad, F. Effect of structurally different plant growth regulators (PGRs) on the concentration, yield, and constituents of peppermint essential oil. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 2018, 23, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Chen, C.Y.; Qiao, H. How chromatin senses plant hormones. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2024, 81, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ke, M.; Sun, Y.; Niu, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. Epigenetic regulation and epigenetic memory resetting during plant rejuvenation. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaski, C.; Giannoulis, K.D.; Alexopoulos, A.A.; Petropoulos, S.A. Biostimulant application alleviates the negative effects of deficit irrigation and improves growth performance, essential oil yield and water-use efficiency of mint crop. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Pang, X. Comparative investigation on aroma profiles of five different mint (Mentha) species using a combined sensory, spectroscopic and chemometric study. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, M.M.; Guo, S.; Mei, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, X. Environmental factors on secondary metabolism in medicinal plants: Exploring accelerating factors. Med. Plant Biol. 2024, 3, e016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, V.; Franke, H.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Risk assessment of pulegone in foods based on benchmark dose–response modeling. Foods 2024, 13, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Singh, S.; Pandey, P.; Semwal, M.; Kalra, A. Menthol mint (Mentha arvensis L.) crop acreage estimation using multi-temporal satellite imagery. J. Indian Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedrzejczyk, I.; Rewers, M. Genome size and ISSR markers for Mentha L. (Lamiaceae) genetic diversity assessment and species identification. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 120, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, M.-H.; San, H.; De Hys, L.; Grenier, E.; David, H.; David, A. How plant regeneration from Mentha × piperita L. and Mentha × citrata Ehrh. leaf protoplasts affects their monoterpene composition in field conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 149, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fejér, J.; Gruľová, D.; De Feos, V.; Ürgeová, E.; Obert, B.; Preťová, A. Mentha × piperita L. nodal segments cultures and their essential oil production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 112, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoli, A.; Leosnardi, M.; Krzyzanowska, J.; Oleszek, W.; Pistelli, L. In vitro production of Mentha × piperita not containing pulegone and menthofuran. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2012, 59, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Jnanesha, A.C.; Talha, M.; Srivastava, A.; Lal, R.K. Industrial mint crop revolution, new opportunities, and novel cultivation ambitions: A review. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 27, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Akhtar, M.T.; Akram, F.; Gohar, U.F. Mentha. In Essentials of Medicinal and Aromatic Crops; Zia-Ul-Haq, M., Al-Huqail, A.A., Riaz, M., Gohar, U.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).