Abstract

Maize requires substantial nitrogen input, and nitrogen deficiency significantly impairs root development, reducing yield. Therefore, improving maize root system architecture under low-nitrogen (LN) conditions is critical for improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). However, the genetic relationship between nitrogen efficiency and root traits is unclear in maize. Here, we conducted a hydroponic experiment during the seedling stage using maize single-segment substitution lines (SSSLs) derived from a cross between the N-efficient inbred line Xu178 and the N-inefficient inbred line Zong3. Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping was performed for root architecture traits under both high-nitrogen (HN) and LN conditions. We identified a total of 160 QTLs, with 101 and 59 detected under HN and LN conditions, respectively. These included 19 for root total length (RTL), 43 for root surface area (RSA), 24 for root average diameter (RAD), 60 for root volume (RV), and 14 for root tip number (RTN), distributed across all ten chromosomes, with the highest number on chromosome 1. Additive effects of individual QTLs ranged from −33.14% to 331.16%. Notably, we discovered a major HN-specific QTL cluster on segments end–umc1929 (Bin 7.00) and bnlg1655 (Bin 10.03), and a key LN-specific cluster on segment umc1883–bnlg249 (Bin 6.00). These findings not only highlight distinct genetic bases for nitrogen adaptation at the seedling stage but also provide valuable molecular markers and candidate genomic regions for the marker-assisted breeding of nitrogen-efficient maize varieties.

1. Introduction

Maize is one of the world’s most important multi-purpose crops. While high-yield breeding has achieved significant progress, these yields heavily rely on intensive nitrogen (N) fertilizer input [1,2]. The low use efficiency of applied nitrogen not only constrains further yield improvements but also increases environmental risks [3]. Therefore, improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) is essential for sustainable maize production [4].

As the primary organ for nutrient acquisition, the root system is vital for nitrogen uptake. A well-developed root architecture can enhance nitrogen absorption and minimize leaching [5,6]. The seedling stage represents a critical phase for the establishment of the root system, which lays the foundation for nutrient acquisition throughout the plant’s life cycle. Therefore, understanding the genetic control of root architecture at this stage is pivotal for improving NUE [7,8,9]. Maize root system architecture (RSA) exhibits considerable plasticity in response to soil nitrogen availability. Under low-nitrogen (LN) conditions, roots often show developmental adjustments such as increased total root length, making RSA a key target for improving NUE [10,11].

Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping is a powerful tool for dissecting the genetic architecture of complex traits like RSA [12]. Although numerous QTLs for root and nitrogen efficiency traits have been identified in various crops (e.g., in wheat [13] and rice [14]) and specifically in maize [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], the majority of these studies were conducted under sufficient nitrogen conditions. Research focusing on QTL mapping under low-nitrogen (LN) stress remains limited, and a significant gap persists in the systematic identification of root architecture QTLs under LN using genetically precise materials like single-segment substitution lines (SSSLs).

To address this gap, we constructed a single-segment substitution line (SSSL) population in the uniform genetic background of the N-efficient inbred line Xu178, using the N-inefficient line Zong3 as the donor parent [25]. This population offers a distinct advantage for precise QTL mapping, as phenotypic differences can be directly attributed to the introgressed segments. Seedlings were cultivated under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) hydroponic conditions, and QTL mapping was performed for five root architecture traits: root total length (RTL), root surface area (RSA), root average diameter (RAD), root volume (RV), and root tip number (RTN). This study thus aimed to: (1) identify QTLs for these root traits under HN and LN stress, and (2) elucidate the genetic relationships between nitrogen efficiency and root architecture, thereby providing a foundation for marker-assisted selection of maize with improved root systems for LN tolerance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Using Zong3 as the donor parent and Xu178 as the recurrent parent, 239 homozygous SSSLs were developed through four generations of backcrossing and three generations of selfing, combined with simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker-assisted selection [25]. These SSSLs were distributed across all ten maize chromosomes, covering 68% of the maize genome. The donor parent, Zong3, was an N-inefficient inbred line sensitive to LN stress, whereas the recurrent parent, Xu178, was an N-efficient line exhibiting tolerance to LN stress. Among these, 150 SSSLs were selected for QTL mapping of root traits under different nitrogen conditions.

2.2. Culturing of Seedlings

A total of 150 SSSLs and their parental lines were selected. For each line, 30 full and intact seeds were surface-sterilized using 10% H2O2 for 30 min, followed by 3–4 rinses with distilled water. The seeds were placed on moist gauze to promote germination and then transferred to clean quartz sand for seedling culture. The growth chamber was maintained at a photosynthetic photon flux density of 400 µmol·m−2·s−1, with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, day/night temperatures of 25 °C/20 °C, and relative humidity of 60–70%. Seedlings were grown in distilled water until the two-leaf stage. In each of the two independent experiments (Exp. 1 and Exp. 2), each genotype under each nitrogen treatment (HN or LN) was represented by six biological replicates. Each biological replicate consisted of one seedling, resulting in a total of 6 seedlings per genotype per treatment per experiment, and 12 seedlings in total across both experiments. Seedlings were placed on 0.5 cm thick plastic boards with 2 cm diameter holes and secured using sponge. Black square plastic boxes (38 × 28 × 12 cm, length × width × height), each accommodating twelve seedlings and 10 L of nutrient solution, were used as culture containers [26,27]. The nutrient solution was renewed every three days and contained: 2 mM Ca(NO3)2·4H2O; 0.75 mM K2SO4; 0.65 mM MgSO4·7H2O; 0.1 mM KCl; 0.25 mM KH2PO4; 0.001 mM H3BO3; 0.001 mM MnSO4·H2O; 0.0001 mM CuSO4·5H2O; 0.001 mM ZnSO4·7H2O; 5 × 10−6 mM (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O; 0.1 mM FeSO4·7H2O; 0.1 mM Na2EDTA; and 2 mM CaCl2. The nitrogen concentration was maintained at 0.05 mM and 4 mM in the LN and HN solutions, respectively. Two independent experiments were conducted in the same greenhouse at Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, China. Experiment 1 was conducted from 10 June to 15 July 2022, and Experiment 2 from 1 August to 31 August 2023. Each experiment lasted 20 days.

2.3. Measurement of Phenotypic Traits

After 20 days of cultivation, four healthy and uniformly vigorous seedlings from each replicate group (twelve seedlings per treatment) were selected and washed with distilled water. Root systems were excised using scissors. Root systems were scanned and analyzed using WinRHIZO Pro software (Regent Instruments, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada) [28]. The scanning area was 21.6 cm × 28 cm, using a transmission scanning mode (dual light source illumination), grayscale image type, and a resolution of 400 dpi to ensure accurate extraction of root architectural parameters. Root total length (RTL), root surface area (RSA), root average diameter (RAD), root volume (RV), and root tip number (RTN) were measured.

2.4. Data Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson’s correlation analyses between different traits and tests were conducted in SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Prior to ANOVA, the homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) and normality of residuals (Shapiro–Wilk test) were verified for all datasets. All trait data met the fundamental assumptions of ANOVA. Any missing data points were excluded from the calculation of the replicate mean for that genotype and trait. Graphics were generated using Origin Pro 8.5 (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

2.5. QTL Mapping

Quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping was performed based on the phenotypic differences between each SSSL and the recurrent parent (Xu178). For each root trait under each nitrogen condition, the phenotypic value of an SSSL was compared to that of Xu178 using Student’s t-tests. Given the unique genetic design of the SSSL population, where each line differs from the recurrent parent by only a single homozygous introgressed segment, a significant phenotypic difference (p < 0.05) was directly attributed to the substituted segment, and a QTL was declared to be present in that segment, which is a well-established standard for QTL analysis in such nearly isogenic line populations [29]. Differences between each SSSL and the recurrent parent (Xu178) were assessed by comparing the observed values of Xu178 using variance analysis and t-tests. A QTL was considered present on the corresponding SSSL segment when p < 0.05, and absent when p > 0.05. Following the method of Eshed and Zamir [29], the additive effect and contribution of each QTL were estimated using the specified formulas:

Additive effect value = (SSSL phenotypic value − Xu178 phenotypic value)/2

Additive effect contribution = (Additive effect value/Xu178 phenotypic value) × 100%

The QTLs were named according to the previous guidelines [30]. The prefix “q” denoted QTL, “hn” indicated high nitrogen, and “ln” low nitrogen. “RTL” referred to root total length, “RSA” to root surface area, “RAD” to root average diameter, “RV” to root volume, and “RTN” to root tip number. The initial number specified the chromosome on which the QTL was located, while the final letter indicated the QTL number for that trait on the chromosome.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Variation and Correlation Analysis Among Traits

Root traits were examined in the two parents under HN and LN conditions (Table 1 and Table 2). Under HN conditions, no significant differences were detected between the two parents in RTL, RSA, RAD, or RV, except for RTN. Under LN conditions, the nitrogen-efficient parent Xu178 developed a larger root system, exhibiting longer RTL, greater RSA, thicker RAD, larger RV, and more RTN than Zong3.

Table 1.

Phenotypic values (mean, range, standard deviation (SD), skewness, kurtosis, and coefficient of variation (CV)) for five root traits of the parents (Xu178, Zong3) and the SSSL population under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) treatments in two experiments (Exp. 1, 2).

Table 2.

Results of three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the effects of environment (E), nitrogen level (N), genotype (G), and their interactions on five root traits in the parents and the SSSL population under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) treatments.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant effects of environment (E) and nitrogen (N) level on RTL, RSA, RAD, RV, and RTN. Significant genotype (G) effects were detected for RSA, RAD, and RTN, but not for RTL and RV. A significant E × N interaction was observed for RTL, RSA, and RTN. The E × G interaction was highly significant only for RAD, whereas the N × G interaction significantly affected RTL, RSA, RV, and RTN, but not RAD. The three-way interaction (E × N × G) was significant only for RSA.

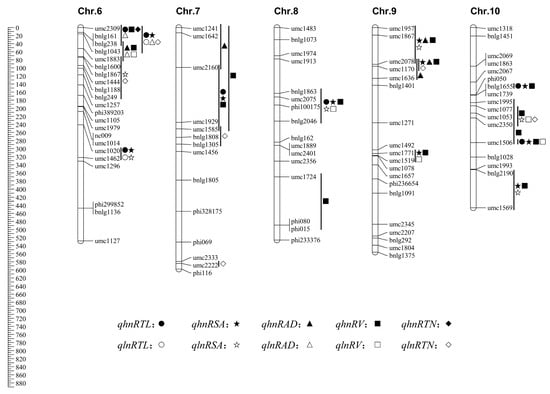

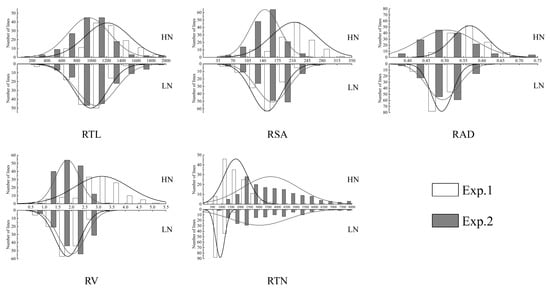

In both experiments, all five traits showed continuous distributions in the SSSL population (Table 1, Figure 1). The coefficients of variation (CV) ranged from 5.62% to 48.01%. Significant transgressive segregation was observed for all traits under both nitrogen conditions. ANOVA results indicated that environment, nitrogen level, genotype, and their interactions had highly significant effects on all five traits in the SSSL population.

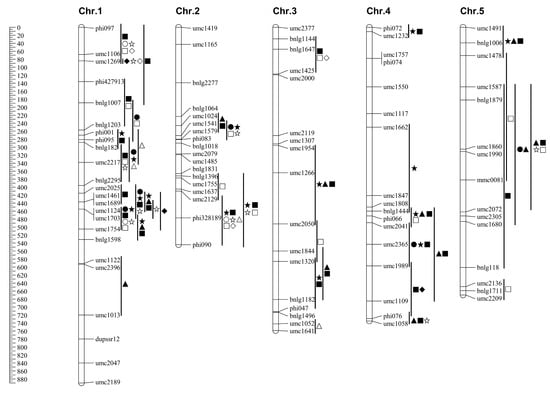

Figure 1.

Chromosomal locations of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for maize seedling root traits identified under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) conditions. QTLs for different traits are represented by distinct symbols, as indicated in the figure legend. The chromosomal positions of QTLs are shown to the right of each chromosome, with HN-specific and LN-specific QTLs highlighted in different colors for clarity. Important QTL clusters mentioned in the text are annotated. Genetic markers and their corresponding bin locations are displayed to the left of the chromosomes. The figure illustrates the distribution of nitrogen condition-specific and stably expressed QTLs across the maize genome.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between traits were calculated (Table 3). Significant positive correlations (p < 0.01) were observed among the five traits under both HN and LN conditions in each experiment. These findings indicated that the SSSL population selected in this study was sensitive to nitrogen stress, rendering it suitable for identifying and further analyzing QTLs associated with root traits.

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between traits under HN condition (below diagonal) and LN condition (above diagonal) in the SSSL population.

3.2. QTL Analysis of Maize Root Traits Under HN Condition

As shown in Table 4, a total of 101 significant QTLs (p < 0.05) were repeatedly detected across two experiments under HN conditions. These QTLs were distributed across 10 chromosomes, with additive effect contributions ranging from 5.20% to 331.16%. Most QTLs for RTL, RSA, RAD, and RV showed positive additive effects, whereas those for RTN showed negative effects under HN conditions.

Table 4.

QTLs identified for maize root morphology traits in the SSSL population under high-nitrogen (HN) condition.

Fourteen QTLs for RTL were identified under HN conditions, located on all chromosomes except 3 and 9, with contributions from −5.29% to 52.48%. While qhnRTL5 and qhnRTL6a showed negative effects, the majority of RTL QTLs exhibited positive additive effects. Twenty-six QTLs for RSA were mapped, all with positive additive effects and distributed across all chromosomes. The contribution of these QTLs varied substantially, from 6.30% (qhnRSA10c) to 166.76% (qhnRSA3a). Seventeen RAD-related QTLs were detected, all with positive effects and contributions between 5.20% to 39.07%. These QTLs were located on all chromosomes except 8 and 10. A total of 40 QTLs were associated with RV, all exhibiting positive additive effects ranging from 8.80% to 331.16% and distributed across all chromosomes. Only four QTLs were identified for RTN under HN. Among them, qhnRTN1a on chromosome 1 exhibited a positive effect (35.57–45.48%), while the other three (qhnRTN1b, qhnRTN4, and qhnRTN6) displayed negative effects, with qhnRTN6 showing the largest effect (−33.14%) in Experiment 1.

Collectively, under high-nitrogen conditions, QTLs for root architecture traits were identified across the entire genome, with chromosome 1 emerging as a major hotspot, harboring numerous QTLs across multiple bins (e.g., 1.01, 1.03, 1.05) for all traits except RAD. Additionally, chromosomes 3 (Bin 3.05) and 10 (Bin 10.03) were identified as key locations for large-effect QTLs influencing RSA and RV.

3.3. QTL Analysis of Maize Root Traits Under LN Condition

Under LN conditions, a total of 59 significant QTLs (p < 0.05) were consistently identified for five root-related traits across two experiments (Table 5). These QTLs were distributed across all 10 maize chromosomes, with additive effect contributions ranging from 3.15% to 170.30%. Most QTLs showed positive additive effects, while nine exhibited negative effects, indicating that synergistic alleles were contributed by the parental line Xu178.

Table 5.

QTLs identified for maize root morphology traits in the SSSL population under low-nitrogen (LN) condition.

Five QTLs associated with RTL were detected on chromosomes 1, 2, and 6. Among them, only qlnRTL2 exhibited a negative additive effect, while the other four had positive effects, with qlnRTL1a showing the largest contribution (35.86% in Exp. 1). Seventeen significant QTLs for RSA were identified, located on all chromosomes except 3 and 7. All RSA QTLs showed positive additive effects, with six clusters on chromosome 1. For RAD, seven QTLs were found, primarily on chromosomes 1 and 6. Two of these (qlnRAD2 and qlnRAD6c) had positive additive effects, while the other five showed negative effects. Twenty RV QTLs, all with positive effects, were distributed on all chromosomes except 7. Ten QTLs were identified for RTN, located on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, and 10. Three of these had negative effects, while the remaining seven were positive, with qlnRTN1a exhibiting an exceptionally large effect (170.30% in Exp. 2).

In summary, under low-nitrogen stress, chromosomes 1 and 6 were identified as major QTL hotspots, harboring multiple co-localized loci for RTL, RSA, RAD, and RV. Notably, the region on chromosome 1 (Bin 1.01) was associated with strong positive effects on RTL, RV, and RTN, highlighting its critical role in shaping root architecture under nitrogen deficiency.

3.4. Distribution of QTL on the Chromosomes

The distribution of QTLs across chromosomes under both nitrogen levels was shown in Figure 1. A total of 160 QTLs associated with root traits (RTL, RSA, RAD, RV, and RTN) were identified across all ten maize chromosomes, with the highest number on chromosome 1 and the fewest on chromosome 8. By separately analyzing QTLs under LN and HN conditions, nitrogen condition-specific QTLs were identified. For example, certain chromosomal segments harbored QTLs exclusively under LN conditions, including segments umc1052–end on chromosome 3, umc2136–end on chromosome 5, umc1883–bnlg249 on chromosome 6, and locus umc2222 on chromosome 7. These QTLs were undetectable under HN conditions and were thus classified as LN-specific. Their presence in substitution lines containing the corresponding segments suggested trait regulation specific to LN conditions, aiding the identification of LN-specific QTLs. Similarly, as shown in Figure 1, several chromosomal segments harbored QTLs only under HN conditions, such as umc2025–umc1689 and umc1122–umc1013 on chromosome 1, umc1954–umc2050 on chromosome 3, end–phi072 and umc2041–umc1989 on chromosome 4, umc2160–umc1585 on chromosome 7, and bnlg1655 on chromosome 10. These were undetectable under LN conditions and were designated as HN-specific QTLs. Together, the LN-specific and HN-specific QTLs were defined as nitrogen condition-specific QTLs, indicating the involvement of distinct metabolic pathways under differing nitrogen regimes. Additionally, some chromosomal segments harbored QTLs under both LN and HN conditions and were defined as stable expression QTLs.

4. Discussion

Maize is a globally important crop, but its high yield potential heavily depends on substantial nitrogen fertilizer inputs [31]. Improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) is therefore crucial for sustainable agriculture [7]. Root morphology plays a key role in nitrogen acquisition from the soil [32], and an ideal root system architecture—characterized by greater root volume, length, and density—can enhance both nitrogen uptake and grain yield [11,33,34]. These findings highlight the importance of root system architecture (RSA) in determining NUE.

RSA is strongly influenced by the nitrogen availability. Under nitrogen-deficient conditions, the number of roots decreased, while total root length increased [10]. This architectural adjustment enabled maize to acquire more nitrogen to support growth and development. Selecting root traits that improve NUE is a promising breeding strategy, but progress has been limited by insufficient knowledge of the genetic relationships between RSA and NUE, as well as a lack of well-defined genomic regions for targeted improvement.

In this study, we used a population of SSSLs derived from crosses between an N-efficient (Xu178) and an N-inefficient (Zong3) inbred lines. Using hydroponic cultures at the seedling stage, we performed QTL mapping for five RSA traits under HN and LN conditions. We identified 160 QTLs with additive effects ranging from −33.14% to 331.16%. Important QTL clusters were detected on chromosomes 2 (umc1024–phi083 and bnlg1396–end), 6 (end–umc1883), and 9 (end–umc1636). These results provide valuable genetic insights and support marker-assisted breeding for nitrogen-efficient maize.

Nitrogen uptake and RSA are complex traits controlled by both genetic and environmental factors. Previous studies have identified QTLs for NUE-related traits such as biomass [35], grain nitrogen content [36], post-silking nitrogen uptake, and nitrogen recycling [37]. Many QTLs influencing RSA have also been reported across maize linkage groups [18,19]. For example, Burton et al. [38] detected 15 QTLs for 21 root traits, with phenotypic variation ranging from 0.44% to 13.5%. Ren et al. [34] confirmed that the auxin-related genes ZmRSA3.1 and ZmRSA3.2 regulate root angle and depth, while Wu et al. [39] identified four candidate genes associated with maize RSA.

In this study, SSSL-based QTL mapping at the seedling stage identified root traits QTLs in bins 1.03, 1.04, and 7.03, consistent with previous studies [38]. Under HN conditions, 101 QTLs were detected, with the highest density on chromosome 1 (Table 4; Figure 2). HN-specific QTLs often formed clusters in specific chromosome segments. For instance, the HN-specific region umc1954–umc2050 (Bin 3.05) overlapped with a root morphology QTL reported by Lebreton et al. [40]. Similarly, QTLs in bins 4.08 and 7.00 reported by Song et al. [19] coincide with the HN-specific regions umc2365–umc1109 (Bin 4.08) and end–umc1585 (Bin 7.00) identified here. Additionally, we also detected HN-specific QTLs on chromosomes 4 (end–phi072), 5 (umc1491–umc1478), and 10 (bnlg1655), suggesting that these regions may contain major-effect loci influencing RSA under high fertility.

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of five root architecture traits in the SSSL population under high-nitrogen (HN) and low-nitrogen (LN) conditions across two independent experiments (Exp. 1 and Exp. 2). Traits measured are: RTL, root total length (cm); RSA, root surface area (cm2); RAD, root average diameter (mm); RV, root volume (cm3); RTN, root tip number.

Given the difficulty in significantly reducing nitrogen fertilizer use in the short term [41], breeding varieties with improved nitrogen uptake under HN conditions represents a practical strategy for enhancing NUE [42]. However, high-yield cultivation systems often involve high nitrogen inputs, which can lead to nitrate leaching and root growth inhibition. Optimized root architecture—with normal lateral root development, high total root length, and density—can improve nitrogen absorption under such conditions [43,44]. The HN-specific QTL clusters identified in this study were considered important for elucidating the genetic basis of nitrogen uptake under high-nitrogen conditions.

Under LN stress, we detected 59 root trait QTLs. Several localized to previously reported regions, including chromosome 5 (bnlg1711–end; Bin 5.07) and 7 (umc2222; Bin 7.05) [19]. Li et al. [20] identified 331 QTLs for NUE and RSA under both HN and LN and found ~70% of NUE-related QTL clusters overlapped with those for RSA, supporting a strong genetic relationship between the two. This suggests that marker-assisted selection for root traits could enhance maize NUE [33].

Our findings are consistent with Li et al. [20], who identified key QTL clusters in Bin 6.00 and 7.02 associated with large root system and enhanced nitrogen absorption. These intervals overlap with the QTLs umc1883–bnlg249 (Bin 6.00) and umc1585–bnlg1305 (Bin 7.02) identified here, suggesting that these regions likely harbor major-effect QTLs for NUE. Fine mapping using SSSLs can help identify candidate genes underlying these effects.

Gallais et al. [45] identified QTLs for post-anthesis nitrogen absorption, nitrogen remobilization, grain yield, and enzyme activities related to nitrogen metabolism. Several co-localized with genes encoding cytosolic glutamine synthetase (GS), and GS loci on chromosome 5 were associated with variation in NUE. Our study detected root trait QTLs in regions overlapping those reported, including segments associated with nitrogen recycling, and GS/GDH activity. Additionally, QTLs for leaf nitrate content, GS, and nitrate reductase activity near umc1587–umc1680 on chromosome 5 are adjacent to one of the QTL clusters identified here [45].

Qi et al. [46] found that segment umc2217–umc1770 on chromosome 1 influences ear traits and partially overlaps with the QTL phi001–umc2217 identified in this study. This suggests that LN-specific QTLs in this region may contribute to nitrogen uptake under low nitrogen. Li et al. [47] and Moussa et al. [48] also identified RSA QTLs across all ten maize chromosomes, with overlaps at umc1954–umc2050 (Bin 3.05) and end–umc1232 (Bin 4.00), supporting the polygenic nature of root development.

We detected multiple QTLs under both HN and LN conditions in several genomic intervals, including chromosome 2 (umc1024–phi083 and bnlg1396–end), chromosome 6 (end–umc1883), and chromosome 10 (umc1995–umc1506). The presence of these environment-specific QTL clusters suggests that maize employs distinct genetic mechanisms under varying nitrogen conditions. Identifying HN- and LN-specific QTLs is essential for understanding adaptation to nitrogen stress and can facilitate the discovery of nitrogen efficiency genes and the development of improved cultivars. While the SSSL population used here provides a powerful system for precise QTL mapping, it does not cover the entire maize genome. Future studies combining the high-resolution mapping of SSSLs with the broad diversity captured by genome-wide association studies (GWASs) could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic control of root traits and nitrogen efficiency.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully identified a total of 160 QTLs governing maize root architecture at the seedling stage under different nitrogen supplies. A key finding was the detection of nitrogen condition-specific QTL clusters: a major LN-specific cluster was mapped to the segment umc1883–bnlg249 (Bin 6.00), while HN-specific QTLs were concentrated in the intervals end–umc1929 (Bin 7.00) and bnlg1655 (Bin 10.03). These genomic regions, which overlap with those previously associated with nitrogen efficiency, represent high-priority candidates for the marker-assisted breeding of nitrogen-efficient maize. Future work will focus on validating the effects of these key QTLs on yield under field conditions and identifying the underlying causal genes.

Author Contributions

Data curation, D.L. and Y.L.; Formal analysis, D.L. and Y.L.; Investigation, D.L. and Y.L.; Supervision, Y.W.; Writing—original draft, D.L.; Writing—review and editing, Y.W.; Study design, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32372811).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.-J.; Liu, J.; Zhai, Z.; Dai, M.; Tian, F.; Wu, Y.; Tang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jackson, D. Maize2035: A decadal vision for intelligent maize breeding. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, W.; Yu, W.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Qi, G.; Yin, M.; Kang, Y.; Ma, Y. A meta-analysis of the effects of nitrogen fertilizer application on maize (Zea mays L.) yield in Northwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1485237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliya, R.; Saharan, V.; Dimkpa, C.; Biswas, P. Nanofertilizer for precision and sustainable agriculture: Current state and future perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 66, 6487–6503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Lemaire, G. From use efficiency to effective use of nitrogen: A dilemma for maize breeding improvement. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBruin, J.; Messina, C.D.; Munaro, E.; Thompson, K.; Conlon-Beckner, C.; Fallis, L.; Sevenich, D.M.; Gupta, R.; Dhugga, K.S. N distribution in maize plant as a marker for grain yield and limits on its remobilization after flowering. Plant Breed. 2013, 132, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhuang, Z.; Cai, H.; Cheng, S.; Soomro, A.A.; Liu, Z.; Gu, R.; Mi, G.; Yuan, L.; Chen, F. Use of genotype-environment interactions to elucidate the pattern of maize root plasticity to nitrogen deficiency. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, H.; Li, S.; Dong, X.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, Z.; Yuan, L. Genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying nitrogen use efficiency in maize. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zou, T.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; Xia, Y.; Yang, L. Auxin synthesis promotes N metabolism and optimizes root structure enhancing N acquirement in maize (Zea mays L.). Planta 2024, 259, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, X.; Chen, F.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Yuan, L.; Mi, G. Genetic improvement of root growth increases maize yield via enhanced post-silking nitrogen uptake. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 63, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengwilai, P.; Tian, X.; Lynch, J.P. Low Crown Root Number Enhances Nitrogen Acquisition from Low-Nitrogen Soils in Maize. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P. Steep, cheap and deep: An ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbs Cortes, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J. Status and prospects of genome-wide association studies in plants. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A. QTL mapping of seedling biomass and root traits under different nitrogen conditions in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yao, S.; Wang, C. QTL mapping for seedling traits related to low nitrogen tolerance in rice. Acta Agric. Bor.-Sin. 2015, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kimutai, C.; Ndlovu, N.; Chaikam, V.; Ertiro, B.T.; Das, B.; Beyene, Y.; Kiplagat, O.; Spillane, C.; Prasanna, B.M.; Gowda, M. Discovery of genomic regions associated with grain yield and agronomic traits in Bi-parental populations of maize (Zea mays L.) Under optimum and low nitrogen conditions. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1266402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse Ertiro, B.; Olsen, M.; Das, B.; Gowda, M.; Labuschagne, M. Genetic dissection of grain yield and agronomic traits in maize under optimum and low-nitrogen stressed environments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gao, K.; Shan, S.; Gu, R.; Wang, Z.; Craft, E.J.; Mi, G.; Yuan, L.; Chen, F. Comparative analysis of root traits and the associated QTLs for maize seedlings grown in paper roll, hydroponics and vermiculite culture system. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochholdinger, F.; Tuberosa, R. Genetic and genomic dissection of maize root development and architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, B.; Hauck, A.L.; Dong, X.; Li, J.; Lai, J. Genetic dissection of maize seedling root system architecture traits using an ultra-high density bin-map and a recombinant inbred line population. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Chen, F.; Cai, H.; Liu, J.; Pan, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gu, R.; Mi, G.; Zhang, F.; Yuan, L. A genetic relationship between nitrogen use efficiency and seedling root traits in maize as revealed by QTL analysis. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3175–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.L.; Liu, S.; Ibrahim, R.; Blanco, M.; Lübberstedt, T. Genome-wide association studies of doubled haploid exotic introgression lines for root system architecture traits in maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Sci. 2018, 268, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, D.; Li, P.; He, K.; Ali, F.; Mi, G.; Chen, F.; Yuan, L.; Pan, Q. Plasticity of root anatomy during domestication of a maize-teosinte derived population. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wei, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Qian, J.; Fan, Y.; Ni, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Integrating GWAS and Gene Expression Analysis Identifies Candidate Genes for Root Morphology Traits in Maize at the Seedling Stage. Genes 2019, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Liu, C.; Mei, X.; Jiang, D.; Wang, X.; Dong, E.; Zhang, J.; Cai, Y. QTL identification in backcross population for brace-root-related traits in maize. Euphytica 2020, 216, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Li, W.; Fu, Z. Development of a set of single segment substitution lines of an elite inbred line Zong 3 on the genetic background Xu 178 in maize (Zea mays L.). J. Henan Agric. Univ. 2013, 47, 6–915. [Google Scholar]

- Long, W.; Li, Q.; Wan, N.; Feng, D.; Kong, F.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, J. Root morphological and physiological characteristics in maize seedlings adapted to low iron stress. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.; Jin, R.; Kong, F.; Ke, Y.; Shi, H.; Yuan, J. Cultivar differences in root nitrogen uptake ability of maize hybrids. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescio, R.; Abenavoli, M.R.; Sorgonà, A. Single and combined abiotic stress in maize root morphology. Plants 2020, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshed, Y.; Zamir, D. An introgression line population of Lycopersicon pennellii in the cultivated tomato enables the identification and fine mapping of yield-associated QTL. Genetics 1995, 141, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCouch, S.R. Report on QTL nomenclature. Rice Genet. Newsl. 1997, 14, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, X.-Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, J.-W.; Zhao, B.; Ren, B.-Z.; Liu, P. Deep nitrogen fertilizer placement improves the yield of summer maize (Zea mays L.) by enhancing its photosynthetic performance after silking. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, B.G. Nitrogen signalling pathways shaping root system architecture: An update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014, 21, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, M.F.; Li, M.; Liu, C.; Liaqat, W.; Altaf, M.T.; Barutçular, C.; Baloch, F.S. Multivariate Analysis of Root Architecture, Morpho-Physiological, and Biochemical Traits Reveals Higher Nitrogen Use Efficiency Heterosis in Maize Hybrids During Early Vegetative Growth. Plants 2025, 14, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Zhao, L.; Liang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Genome-wide dissection of changes in maize root system architecture during modern breeding. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1408–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Chu, Q.; Yuan, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; Mi, G.; Zhang, F. Identification of quantitative trait loci for leaf area and chlorophyll content in maize (Zea mays) under low nitrogen and low phosphorus supply. Mol. Breed. 2012, 30, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qin, J.; Li, T.; Liu, E.; Fan, D.; Edzesi, W.M.; Liu, J.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Xiao, L. Fine mapping and candidate gene analysis of qSTL3, a stigma length-conditioning locus in rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coque, M.; Martin, A.; Veyrieras, J.B.; Hirel, B.; Gallais, A. Genetic variation for N-remobilization and postsilking N-uptake in a set of maize recombinant inbred lines. 3. QTL detection and coincidences. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 117, 729–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.L.; Johnson, J.M.; Foerster, J.M.; Hirsch, C.N.; Buell, C.R.; Hanlon, M.T.; Kaeppler, S.M.; Brown, K.M.; Lynch, J.P. QTL mapping and phenotypic variation for root architectural traits in maize (Zea mays L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 2293–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Ren, W.; Zhao, L.; Li, Q.; Sun, J.; Chen, F.; Pan, Q. Genome-wide association study of root system architecture in maize. Genes 2022, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, C.; Lazić-Jančić, V.; Steed, A.; Pekić, S.; Quarrie, S.A. Identification of QTL for drought responses in maize and their use in testing causal relationships between traits. J. Exp. Bot. 1995, 46, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, W.F.; Chen, X.P.; Cui, Z.L.; Fan, M.S.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, F.S. Nitrogen fertilizer input and nitrogen use efficiency in Chinese farmland. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2016, 4, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- York, L.M.; Galindo-Castañeda, T.; Schussler, J.R.; Lynch, J.P. Evolution of US maize (Zea mays L.) root architectural and anatomical phenes over the past 100 years corresponds to increased tolerance of nitrogen stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, G.; Chen, F.; Wu, Q.; Lai, N.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, F. Ideotype root architecture for efficient nitrogen acquisition by maize in intensive cropping systems. Sci. China Life Sci. 2010, 53, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, D.; Zhang, S.; Gu, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Huang, S. Optimizing root system architecture to improve root anchorage strength and nitrogen absorption capacity under high plant density in maize. Field Crop. Res. 2023, 303, 109109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallais, A.; Hirel, B. An approach to the genetics of nitrogen use efficiency in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Huang, J.; Zheng, Q.; Huang, Y.; Shao, R.; Zhu, L.; Yue, B. Identification of Significant Loci for Yield and Yield-related Traits in Maize with Introgression Lines. J. Maize Sci. 2013, 21, 24–27, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, G.; Zhao, Z.; He, K.; Yang, X.; Pan, Q.; Mi, G.; Jia, Z.; Yan, J. Genomic basis determining root system architecture in maize. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, A.A.; Mandozai, A.; Jin, Y.; Qu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, H.; Anwari, G.; Khalifa, M.A.S.; Lamboro, A.; Noman, M. Genome-wide association screening and verification of potential genes associated with root architectural traits in maize (Zea mays L.) at multiple seedling stages. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).