Abstract

In response to the challenges in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based poppy plant detection, such as dense small targets, occlusions, and complex backgrounds, an improved YOLOv8-based detection algorithm with multi-module collaborative optimization is proposed. First, the lightweight Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism was integrated into the YOLOv8 backbone network to construct a composite feature extraction module with enhanced representational capacity. Subsequently, a Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) was introduced into the neck network to establish adaptive cross-scale feature fusion through learnable weighting parameters. Furthermore, the Wise Intersection over Union (WIoU) loss function was adopted to enhance the accuracy of bounding box regression. Finally, a dedicated 160 × 160 pixels detection head was added to leverage the high-resolution features from shallow layers, thereby enhancing the detection capability for small targets. Under five-fold cross-validation, the proposed model achieved mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.989 ± 0.003 and 0.850 ± 0.013, respectively, with average increases of 1.3 and 3.2 percentage points over YOLOv8. Statistical analysis confirmed that these performance gains were significant, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method as a reliable solution for poppy plant detection.

1. Introduction

The development of a practical automated opium poppy detection model provides reliable technological support for rapid screening and dynamic monitoring of illicit cultivation, thereby contributing to agricultural ecological security and social stability. The deep integration of artificial intelligence and remote sensing technologies establishes UAV-based inspection as a critical solution for opium poppy detection. Equipped with multispectral cameras, UAVs not only deliver high-resolution imagery to accurately identify opium poppy characteristics but also overcome topographic constraints, enabling comprehensive monitoring coverage in challenging terrains such as mountainous and densely forested areas. Nevertheless, the practical application of UAV-based poppy detection confronts several critical challenges: (1) High Density of Small Targets. Opium poppy plants typically exhibit low pixel coverage and occur in high-density distributions within cluttered agricultural environments. (2) Significant Scale Variation. Opium poppy plants display pronounced scale variation even for the same plant across images due to varying UAV perspectives and flight altitudes. (3) Complex Background Interference. Opium poppy plants are often affected by interference from surrounding walls, soil, and artificial occlusions, which can easily lead to false detections. Therefore, significantly improving detection precision while reducing the missed identification of small opium poppy targets in complex and variable field environments remains a major challenge in this research area.

With the rapid development of deep learning, object detection algorithms based on convolutional neural networks are a major focus of research in computer vision. These algorithms are primarily categorized into two-stage and one-stage detectors. Two-stage detectors, represented by R-CNN [1] (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) and its successors, including Fast R-CNN [2] and Faster R-CNN [3], achieve high detection accuracy on benchmark datasets such as PASCAL VOC and COCO. However, their multi-stage processing pipelines inherently limit detection speed. To improve efficiency, one-stage detectors employ an end-to-end network architecture, with typical representatives being the Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [4] and the You Only Look Once (YOLO) [5] series.

To improve the YOLO model’s performance in detecting small objects, Wang et al. [6] proposed the MFP-YOLO algorithm, which introduced the Multi-path Inverse Residual Block (MIRB) and the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to collectively enhance the model’s focus on key feature regions of small targets. Building upon YOLOv5, Zhang et al. [7] introduced a Feature Enhancement Module (FEM), a Feature Fusion Module (FFM), and a Spatial Context-Aware Module (SCAM) to improve the accuracy and efficiency of small-object detection. Wu et al. [8] incorporated the Bi-level Routing Attention (BRA) mechanism and coupled it with a Dynamic Detection Head (DyHead) to enhance the model’s precision. Zhao et al. [9] enhanced the original PANet structure in YOLOv8 by proposing a multi-branch partial dilated convolution module, which enables the model to achieve a larger receptive field and thereby strengthens feature extraction for small targets. Chen et al. [10] enhanced the YOLOv8s backbone network by designing an Enhanced Convolutional Pyramid Bottleneck (ECPB) module, introducing a Large Separable Kernel Attention (LSKA) module, and designing a Task-adaptive Dynamic (TAD) detection head, which collectively enable the model to capture more information from small pedestrian targets. Huo et al. [11] modified the YOLOv8n architecture by replacing the C2f module with the RepLayer model and introducing a large-kernel depthwise separable convolution structure, thereby expanding contextual information and strengthening the model’s capacity to capture features of small objects.

Significant progress has been made in recent years in small-object detection techniques for agricultural applications, particularly in smart crop monitoring, pest and disease identification, and growth status evaluation. Previous efforts have primarily focused on optimizing network architectures, with researchers concentrating on lightweight design and multi-scale feature enhancement [12,13,14] to improve detection accuracy while simultaneously reducing model complexity. The introduction of attention mechanisms [15,16,17,18] directs model attention toward salient regions, effectively suppressing background interference and significantly enhancing feature discriminability for small targets. Concurrently, contextual information modeling [19,20] has emerged as a critical strategy for enhancing detection performance. By capturing target–environment interactions, this approach effectively compensates for the inherent limitation of insufficient semantic information in small objects. Moreover, in terms of data augmentation and generalization optimization, enhancement methods based on generative models and domain adaptation methods are becoming new research hotspots [21,22].

Remote sensing monitoring and automated identification of opium poppy have emerged as a critical research direction in agricultural informatics and illicit crop supervision. Early studies primarily utilized hyperspectral and multispectral imaging techniques, achieving opium poppy cultivation identification through spectral signature analysis. Nakazawa et al. [23] developed a technique for detecting illicit opium poppy fields using hyperspectral data by exploiting spectral signature differences between poppy and other crops. Subsequently, Calderón et al. [24] integrated multispectral and thermal infrared imaging from UAVs to develop a high-accuracy model for identifying poppy downy mildew, thereby demonstrating the potential of multi-source imagery in plant disease surveillance and species identification. The rapid advancement of deep learning has shifted research focus toward automated feature extraction and object detection using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Liu et al. [25] pioneered the application of deep learning to opium poppy detection, achieving notably high recognition accuracy even under complex background conditions. Building upon this foundation, Zhou et al. [26] refined the YOLOv3 architecture by incorporating SPP, GIoU, and MN modules, significantly enhancing both detection speed and accuracy for identifying opium poppy targets in UAV imagery. Simultaneously, Demir and Başayiğit [27] achieved spatial mapping of opium poppy cultivation plots using high-resolution satellite imagery, establishing a technical foundation for large-scale monitoring. Zhang et al. [28] developed a deep neural network-based rapid detection algorithm that achieved optimized real-time performance in UAV imagery. Recent research has increasingly concentrated on small object detection in complex operational environments and the development of lightweight network architectures. Pérez-Porras et al. [29] employed a YOLO-based framework to detect early-stage poppy weeds in wheat fields, achieving precise ground-level identification. Yao and Wang [30] and Zhang et al. [31] enhanced the robustness and generalization of poppy detection in UAV imagery, respectively, through network architecture modifications and refinements of the YOLOv5 architecture. In the latest research, Wang et al. [32] proposed a specialized algorithm, termed YOLO-Poppy, which improved downsampling strategy, integrated vegetation indices, and employed a unified metric loss function, demonstrating excellent performance in poppy detection tasks. Collectively, opium poppy detection technology is undergoing a notable shift from spectral analysis toward multisource data fusion and deep learning-based intelligent detection, marking a substantial leap from macroscopic remote sensing to high-precision target identification.

Although the aforementioned methods have improved small-target detection capability to some extent, the detection accuracy and robustness still struggle to meet practical demands, due to key technical challenges including insufficient feature information of small poppy targets, multi-scale target variability, and complex occlusion scenarios. To address these issues, we implemented several improvements. First, we introduced a refined C2f_ECA module into the backbone network to enhance small-target perception. This module employs an efficient channel attention mechanism that amplifies responses to weak textures and fine-grained features. Second, we introduced the BiFPN, proposed in EfficientDet [33], to achieve bidirectional and weighted fusion of multi-level features. This integration combined low-level spatial details with high-level semantic information, which enhanced the model’s overall feature representation and detection accuracy. Third, to mitigate the training imbalance between hard and easy samples, the WIoU loss function [34] was adopted. This approach effectively suppresses the interference from low-quality examples and improves localization accuracy and bounding box regression performance. Finally, a high-resolution P2 detection head was incorporated to substantially enhance the model’s detection performance for small-scale targets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.1.1. Image Acquisition

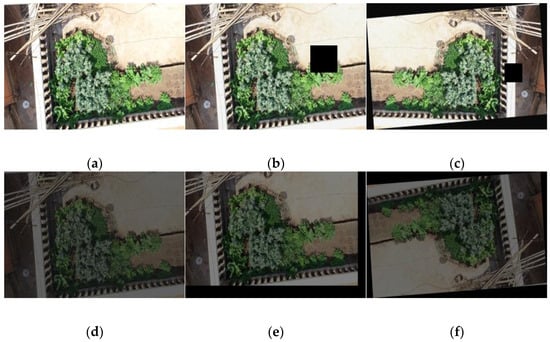

In this study, a DJI M210 UAV equipped with a visible-light camera (image resolution: 1920 × 1080 pixels; DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China) was used to acquire visible-light images of poppy plants from three collection sites in Yunnan Province. The acquisition process comprehensively covered different times of the day (morning, noon, and afternoon), a range of illumination conditions, and various complex environments, including courtyards, fields, and rooftops. Representative examples of the images are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample images from the raw dataset under various conditions. (a) Courtyard scene; (b) Farmland scene; (c) Rooftop scene; (d) Images captured between 09:00–12:00; (e) Images captured between 12:00–14:00; (f) Images captured between 14:00–18:00.

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

The 402 original poppy plant images collected by the UAV were processed using the OpenCV library. Data augmentation techniques, including random rotation, random regional masking, and hue-saturation variation, were applied to the dataset as illustrated in Figure 2. Following augmentation, a quality screening procedure was implemented, yielding a final curated dataset of 4690 high-quality poppy plant images. All samples were then manually annotated using the LabelImg tool (v1.8.6), with rectangular bounding boxes detected according to a unified object detection protocol. The marking process for poppy plants is illustrated in Figure 3. Finally, the complete dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using an 8:1:1 ratio, resulting in 3752, 469, and 469 images for each respective subset.

Figure 2.

Original and augmented dataset images. (a) Original image; (b) Random occlusion; (c) Random rotation with occlusion; (d) Saturation adjustment; (e) Random translation with saturation change; (f) Random rotation with saturation adjustment.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the annotation process for poppy plants in UAV imagery. White rectangular bounding boxes indicate manually annotated poppy plants, providing labeled samples for the subsequent small target detection task.

2.2. YOLOv8 Detection Algorithm

The YOLOv8 architecture is primarily composed of four core components: the Input module, the Backbone network, the Neck network, and the Detection head.

The Input module standardizes the input image resolution to 640 × 640 pixels for batch training, incorporating a composite data augmentation strategy that combines Mosaic, MixUp, and HSV color space perturbations.

The Backbone network is based on an improved CSPDarknet architecture [35]. It comprises standard Convolutional (Conv) layers, the C2f module, and the Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF) module. The standard convolution, serving as the fundamental processing unit, is composed of a 3 × 3 convolution, batch normalization, and a SiLU activation function [36]. It is responsible for feature extraction and downsampling. The C2f module incorporates the gradient combination philosophy of the ELAN architecture from YOLOv7 [37], achieving diversified gradient fusion by integrating deep features extracted from a primary pathway with shallow features preserved from an auxiliary pathway. The SPPF module utilizes max pooling operations at different scales to expand the spatial context of features, serving as a key bridge for multi-scale perception.

The Neck network adopts an FPN + PAN architecture for multi-scale feature fusion, thereby enhancing information flow across different feature scales. The Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [38] propagates high-level semantic information to the lower-level feature maps via a top–down pathway, strengthening the semantic representation of low-resolution features. The Path Aggregation Network (PAN) [39] improves boundary localization accuracy by reinforcing the bottom–up pathway, which directly infused primitive texture details into the final prediction layers.

The Detection head adopts a decoupled architecture, with separate dedicated branches for classification and regression tasks. This design is further enhanced by an Anchor-Free detection mechanism that directly predicts target center points and bounding box offsets, resulting in a more flexible and efficient detection process.

YOLOv8 represents one of the most effective models in the YOLO series. According to the network depth and feature map width, YOLOv8 models can be categorized into five versions: YOLOv8-n, s, m, l, and x. In this study, YOLOv8m was selected as the baseline model for our proposed improvements, offering a favorable trade-off between model size and detection accuracy.

2.3. The Proposed Algorithm

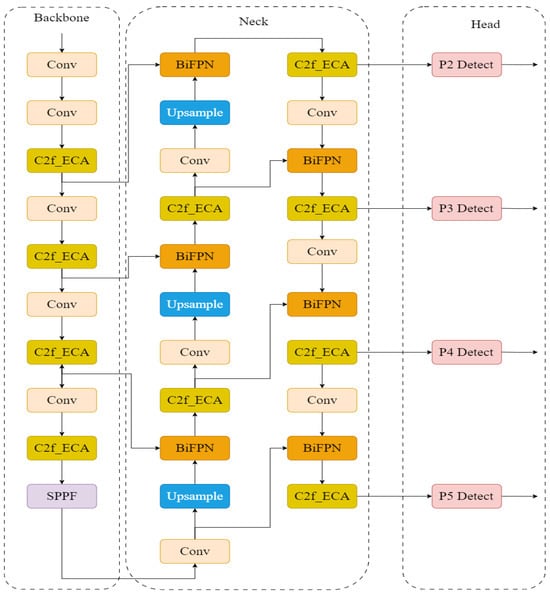

To address the challenges of inadequate feature representation, significant scale variations, and complex background interference in detecting small-target opium poppy plants from UAV imagery, this study proposed a novel YOLOv8m detection framework based on the collaborative optimization of multiple modules. The model structure was systematically improved in four key dimensions: feature enhancement, multi-scale fusion, loss function optimization, and small-target detection head design. Its overall structure is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Structure of the improved YOLOv8 model. Input UAV images are processed by the backbone network, which incorporates the C2f_ECA module to enhance channel-wise attention. The resulting features are fused in the BiFPN neck and subsequently passed to the high-resolution small-target detection head (P2) to detect small-scale poppy plants. Bounding box regression is guided by the WIoU loss, improving localization precision.

In the improved YOLOv8 model presented in this work, the input UAV-captured image was first processed through the backbone network to extract multi-scale features. A C2f_ECA module was embedded into the backbone to employ an efficient channel attention mechanism to adaptively recalibrate feature responses across channels. This mechanism enhanced semantics relevant to poppy plants while suppressing redundant background information, thereby providing a high-quality feature representation for subsequent multi-scale feature interaction. Subsequently, the enhanced features from the C2f_ECA module were fed into the BiFPN neck structure, where the high-resolution details of the shallow P2 layer were fully integrated with the semantic information of the deep P5 layer through bidirectional cross-scale connections and learnable weighting mechanisms. The fused feature maps were then passed to the high-resolution P2 detection head, enabling direct prediction of small-scale poppy plants. During the bounding box regression phase, the Wise-IoU loss function was employed to optimize localization accuracy throughout the training process.

The improved model exhibited a well-organized and functionally complementary architecture. The synergistic integration of feature extraction, multi-scale fusion, high-resolution prediction, and bounding box optimization enabled the enhanced YOLOv8m to achieve significant improvements in both detection accuracy and adaptability to complex scenarios in UAV aerial poppy small-target detection.

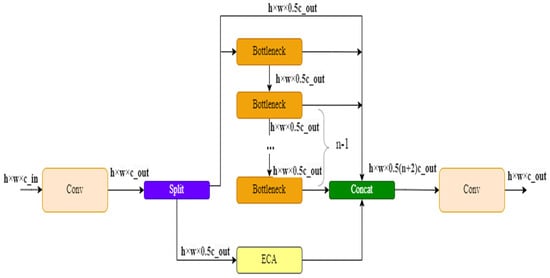

2.3.1. C2f_ECA Module

ECA [40] is a lightweight and efficient channel attention mechanism designed to enhance the network’s ability to represent channel-wise features while maintaining low computational complexity. In contrast to the conventional SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) module [41], ECA omits the channel dimensionality reduction and fully connected operations, thereby preventing information loss caused by dimensionality reduction. It employs a local cross-channel interaction strategy to model inter-channel dependencies.

As shown in Figure 5, the ECA module initially performs global average pooling on the input feature map. This operation compresses the spatial information into a channel-wise global response, resulting in a global context descriptor. Subsequently, a one-dimensional convolution of size k is applied to capture local cross-channel interactions, enabling efficient information transfer. The convolutional output is then activated by a Sigmoid function to generate a channel-wise weight vector. This vector is subsequently multiplied by with the original input features channel by channel to perform feature recalibration, producing an output endowed with channel-attentive characteristics. Through this mechanism, the ECA module enhances the network’s ability to focus on critical information without significantly increasing the parameter count.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the ECA mechanism. The input feature X is first processed by global average pooling (GAP) to produce a channel descriptor vector. A 1D convolution models local cross-channel interactions, followed by a Sigmoid function to generate channel attention weights. Finally, these weights are multiplied with the input feature map channel-wise to obtain the recalibrated output feature.

To further enhance the model’s capability in detecting small-target and weak-texture opium poppy plants, we introduced an improved feature extraction module—the C2f_ECA module into the original backbone architecture of YOLOv8m. The structure is shown in Figure 6. The input features are first processed through a convolutional layer and then split into two paths: One pathway undergoes multi-layer residual feature extraction in the Bottleneck branch, while the other enters the ECA module for channel attention modeling. During feature fusion, the outputs from the two pathways are concatenated, forming a feature representation that incorporates both deep semantic information and channel-wise weighted features. This combined representation is then integrated and output through a 1 × 1 convolutional layer. The C2f_ECA module preserves the multi-branch efficiency of YOLOv8m while enhancing feature fusion consistency through attention modeling, thereby providing more discriminative features for subsequent detection heads.

Figure 6.

Structure of the C2f_ECA module integrated into the YOLOv8 backbone. The input feature map is first processed by a convolution layer and then split into two branches. One branch employs the Bottleneck module for multi-layer residual feature extraction, while the other branch is fed into the ECA module for channel-wise attention modeling. The outputs from both branches are concatenated and subsequently fused through a convolution layer to produce the final output feature.

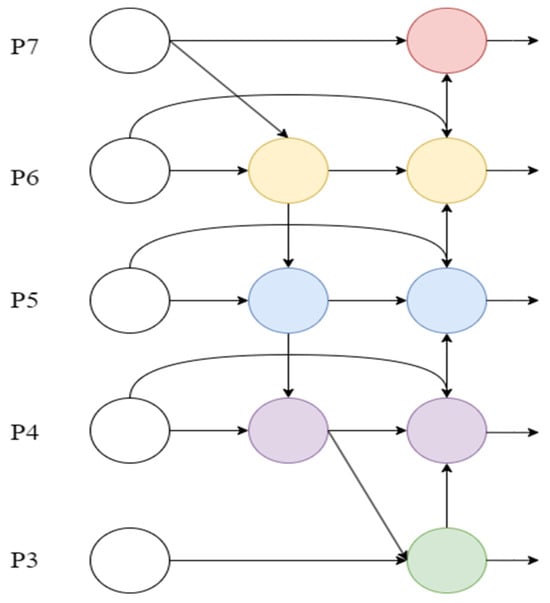

2.3.2. BiFPN Architecture

To strengthen multi-scale feature representation, we introduced a BiFPN in the neck of YOLOv8m, replacing the original PANet architecture. However, PANet exhibits limitations in feature flow direction and fusion strategy, particularly in complex backgrounds or scenes with dense occlusions of poppy plants, often leading to missed and false detections. BiFPN enhances small-target detection precision and robustness by enabling efficient cross-scale integration of semantic and spatial information through optimized feature flow paths and fusion mechanisms. The architecture is presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the BiFPN structure. The figure illustrates the bidirectional feature fusion mechanism of the BiFPN across multiple feature scales (P3 to P7). Each colored node represents a feature processing unit that supports both top–down and bottom–up information flow, while the directed edges indicate the propagation of feature maps.

The BiFPN architecture incorporates a learnable weighting mechanism, where each fusion node takes n input features with corresponding non-negative learnable weights , and produces a fused output expressed as:

Here, is the initial learnable parameter, with the ReLU function ensuring non-negative weights. A small constant is added to prevent numerical instability caused by a zero denominator.

In contrast to traditional softmax normalization, this simple weighted normalization avoids the exponential operations that can cause numerical inflation, thereby achieving superior training stability and inference efficiency. After normalization, the weights of the input features satisfy:

This study integrated BiFPN into the neck of YOLOv8m, which enhanced the expression of fine-grained details in low-level features through bidirectional feature flow and cross-scale fusion. Through this integration, the incorporated weighted fusion mechanism dynamically allocated weights based on input feature quality, thereby improving small object detection performance while maintaining inference efficiency.

2.3.3. WIoU Loss Function

The loss function is a pivotal component in object detection, critically influencing both the model’s convergence speed and its final detection performance. Although the traditional Intersection over Union (IoU) loss function can effectively measure the overlap between the predicted box and the ground truth box, it suffers from gradient disappearance in non-overlapping cases and is sensitive to low-quality samples, which can easily lead to model overfitting or a degraded generalization. To enhance the accuracy of bounding box regression and mitigate the influence of low-quality samples in the training process, we introduced the WIoU loss function as the bounding box localization loss in our YOLOv8m-based framework. The core idea of WIoU lies in introducing a dynamic non-monotonic focusing mechanism (FM) that, combined with the spatial outlier degree of anchor boxes, adaptively allocates gradients to samples of different qualities. This approach enhances regression accuracy while improving model robustness. The loss function is defined as:

where IoU denotes the overlap between the predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes, and is the focusing weight term that dynamically adjusts the loss contribution based on anchor box quality. This weight is defined as:

where is a modulating factor that regulates the degree of focus, and is an outlier score metric that quantifies the “anomaly degree” of a predicted box relative to others in the current feature space.

Unlike traditional loss functions such as CIoU, which can suffer from unstable convergence due to overly strong geometric penalties, WIoU diverges by applying a non-linear weighting focused on sample quality rather than uniformly to all positive examples. This mechanism reduces training noise from low-quality samples while effectively enhancing the model’s localization capability, making it particularly suited for the complex scenarios involving occluded and low-contrast poppy plants in our experiments.

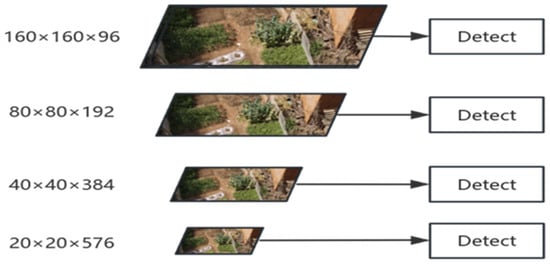

2.3.4. Small Object Detection Head

During preprocessing in the YOLOv8m model, all input images were resized to a fixed dimension of 640 × 640 pixels. This operation further reduced the relative scale of small poppy targets in the input imagery. The effective pixel area of some small targets was reduced to less than 8 × 8 pixels. The baseline YOLOv8m architecture is equipped with detection heads at three resolutions: 20 × 20, 40 × 40, and 80 × 80, corresponding to receptive fields of approximately 32 × 32, 16 × 16, and 8 × 8 pixels, respectively. When a target’s actual size in the input image is smaller than 8 × 8 pixels, missed detections of ultra-small poppy targets occur.

To address this issue, an additional 160 × 160 detection head was incorporated into the Head layer, as shown in Figure 8. This dedicated component operated with a compact receptive field to perform fine-grained feature extraction, which enhanced the network’s capability to capture small objects and preserved critical information that would otherwise be lost with larger receptive fields.

Figure 8.

Integration of the newly added 160 × 160 detection head in the YOLOv8m framework. The newly added high-resolution head complements the existing 20 × 20, 40 × 40, and 80 × 80 detection layers by providing a finer-grained receptive field. This enhancement effectively captures small poppy targets that are often overlooked by the baseline model due to limited spatial resolution.

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

We employed precision (P), recall (R), mean average precision (mAP), Giga Floating-Point Operations (GFLOPs), and the number of parameters as evaluation metrics for model performance. mAP@0.5 corresponds to the mean average precision with the IoU threshold fixed at 0.5. mAP@0.5:0.95 denotes the average precision over IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with a step size of 0.05. The computational formulas for Precision, Recall, AP, and mAP are as follows:

Here, denotes the number of positive samples correctly identified by the model. signifies the number of negative samples incorrectly identified as positive. refers to the number of positive samples mistakenly predicted as negative. represents the Precision value at the corresponding Recall . is the total number of object categories, and denotes the Average Precision for the -th class.

2.5. Experimental Environment and Parameter Configuration

The experiments utilized pre-trained weights obtained from the COCO128 dataset. The hardware and software configurations were documented in Table 1, while the corresponding training parameters were summarized in Table 2. The SGD optimizer was employed with the hyperparameters specified in Table 2 to accelerate model convergence. To ensure experimental consistency and fairness, the number of training epochs was fixed at 100 for all runs.

Table 1.

Experimental environment. The experiments are conducted on a CentOS Linux 7.6.1810 system with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Silver 4110 CPU @ 2.10 GHz and an NVIDIA Tesla M10 GPU. The deep learning framework is PyTorch 1.13.0, and Python 3.9 is used as the programming language. CUDA 11.6 is employed for GPU acceleration.

Table 2.

Training parameters. The model uses a batch size of 8 and an input image resolution of 640 × 640 pixels. The initial learning rate is 0.01 with a cosine annealing schedule and a momentum factor of 0.937. Weight decay is applied with a coefficient of 0.0005 to regularize the network. These hyperparameters are used consistently across all experiments unless otherwise specified.

2.6. Data Analysis Methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed modules and strategies for poppy detection, a series of experiments were conducted, including attention mechanism comparison, bounding box regression loss comparison, multi-model performance comparison, ablation studies, and visual assessment on representative UAV images.

- (1)

- Evaluation of Attention Mechanisms

To evaluate the effectiveness of different attention mechanisms, Triplet [42], SE, SGE [43], SA [44], and GAM [45] were integrated into the YOLOv8m baseline model. All models were trained under identical hyperparameter settings and dataset splits to ensure fair comparison. The impact of each attention mechanism on detection accuracy was quantified using mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 metrics.

- (2)

- Evaluation of Bounding Box Regression Loss Functions

To assess the effectiveness of WIoU for bounding box regression, it was compared with several established loss functions, including CIoU, DIoU [46], GIoU [47], SIoU [48], and NWD Loss [49], within the same YOLOv8m framework.

- (3)

- Evaluation of Multiple Network Models

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed algorithm, multiple mainstream object detection models were selected for comparison, including one-stage models (YOLOv8m, YOLOv3, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10, YOLOv11) and a transformer-based detector (RT-DETR). All comparative models were trained under standardized settings, ensuring consistent datasets, training epochs, learning rates, and data augmentation strategies to provide a fair and transparent evaluation.

- (4)

- Ablation Experiments

To verify the contribution of each improved module to the overall model performance, ablation experiments were conducted based on the YOLOv8m framework. Tests were performed individually and in combination on the C2f_ECA module, BiFPN feature fusion network, WIoU loss function, and the small-target detection layer (P2).

- (5)

- Visual Assessment

To further assess the practical detection capability of the improved algorithm, detection results of the proposed model and YOLOv8m were visually compared on representative UAV images. This evaluation intuitively demonstrates the advantages of the improved algorithm under challenging conditions, including dense small targets and complex backgrounds.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Attention Mechanisms

There were certain variations in the performance of different attention mechanisms in UAV poppy identification tasks, and the experimental results are presented in Table 3. The baseline model’s mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 were 0.976 and 0.823, respectively. In the comparison of individual modules, the ECA module demonstrated the best performance, with mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 0.978 and 0.824, respectively. The SGE module performed comparably to the baseline, whereas the SE and GAM modules exhibited modest reductions in detection accuracy, with mAP@0.5:0.95 values of 0.801 and 0.793, respectively. The SA module showed the lowest performance, attaining only 0.756 in mAP@0.5:0.95.

Table 3.

Ablation study on different attention mechanisms integrated into the YOLOv8m baseline. This experiment investigates the performance variations caused by incorporating multiple representative attention modules, including Triplet Attention, SE, SGE, ECA, SA, and GAM, into the baseline network. The detection accuracy is evaluated using mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95.

3.2. Comparison of Bounding Box Regression Loss Functions

As summarized in Table 4, the influence of different regression loss functions on model performance varied notably. When the baseline model employed the CIoU loss function, the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 were 0.976 and 0.823, respectively. Among the comparative methods, both DIoU and WIoU yielded modest improvements, with WIoU notably achieving the highest mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.827. The NWD Loss achieved an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.826, closely approaching the performance of WIoU, while GIoU and SIoU showed slightly lower accuracy, at 0.814 and 0.818, respectively. Overall, WIoU performed the best in terms of overall accuracy.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of different bounding box regression loss functions within the YOLOv8m framework. This ablation experiment evaluates the impact of six representative regression losses (CIoU, DIoU, GIoU, SIoU, WIoU, and NWD Loss) on detection performance. The assessment is conducted using mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 as the evaluation metrics.

3.3. Comparison of Network Model Performance

Table 5 presents the performance differences in various detection algorithms in the unmanned aerial vehicle poppy recognition task.

Table 5.

Comparison of the proposed algorithm with mainstream object detection methods. The performance of the proposed algorithm is evaluated against a variety of classical and state-of-the-art detectors, including one-stage models (YOLOv8m, YOLOv3, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10, YOLOv11) and a transformer-based detector (RT-DETR). Evaluation metrics include precision (P), recall (R), mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95, while computational efficiency is compared in terms of GFLOPs and parameter count wherever available.

Among the YOLO series models, YOLOv8m achieved high detection performance, with a mAP@0.5 of 0.976, serving as the baseline for comparison. YOLOv3 also showed strong accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 0.957) but required substantially higher computational resources (284.2 GFLOPs) and parameters (103.7 M). The lightweight model YOLOv8n greatly reduced computational cost to 8.1 GFLOPs, though with lower accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 0.951). YOLOv10 and YOLOv11 achieved competitive mAP@0.5 values of 0.970 and 0.967, respectively, with YOLOv10 incurring higher computational cost (58.9 GFLOPs) than YOLOv11 (21.5 GFLOPs).

RT-DETR demonstrated competitive detection performance, with a recall of 0.966 and mAP@0.5 of 0.989, but at the expense of high computational cost (103.4 GFLOPs) and parameter count (31.99 M).

The improved model achieved the best overall results, with precision, recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 0.979, 0.968, 0.993, and 0.835, respectively. Although its computational cost increased to 99.9 GFLOPs, the parameter count remained moderate, offering a more favorable balance between accuracy and complexity compared with both the YOLO series and RT-DETR.

3.4. Ablation Studies

The results of the ablation experiments are presented in Table 6. Overall, the baseline model’s mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 were 0.976 and 0.823, respectively. Introduction of the C2f_ECA module alone increased mAP@0.5 to 0.978 and mAP@0.5:0.95 to 0.824. Following the integration of BiFPN, the mAP@0.5:0.95 declined to 0.740. The incorporation of WIoU improved the mAP@0.5:0.95 to 0.827. Adding the small target detection head P2 significantly improved model performance, with mAP@0.5 reaching 0.989 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 0.855.

Table 6.

Ablation study of the contributions of individual components integrated into the YOLOv8m baseline, including the C2f_ECA module, BiFPN neck, WIoU loss, and the small object detection head (P2). Each module is added individually or in combination to evaluate its impact on precision (P), recall (R), mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, GFLOPs, and parameter count. The symbols √ and × indicate whether a specific module is used or not (√: included, ×: not used).

In multi-module configurations, the C2f_ECA + BiFPN model achieved an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.764, while C2f_ECA + WIoU and C2f_ECA + P2 achieved 0.823 and 0.852, respectively. The integrated C2f_ECA + BiFPN + P2 architecture achieved 0.981 mAP@0.5 and 0.796 mAP@0.5:0.95, indicating a slight reduction in accuracy under multi-scale fusion. The final model integrating all four modules achieved the best performance, with an mAP@0.5 of 0.993 and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.835, respectively, over the baseline model. The computational cost increased modestly from 78.7 to 99.9 GFLOPs, while the parameter count was slightly reduced to 25.55 M.

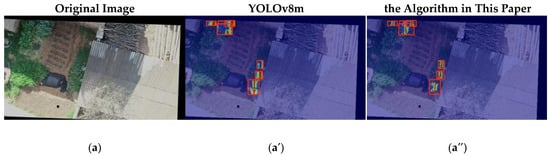

3.5. Visual Comparison of Detection Results

Figure 9 presents typical aerial detection results, with the left, middle, and right columns displaying the original images, YOLOv8m detections, and our model’s outputs, respectively.

Figure 9.

Comparison of detection results. (a) Original image; (a′) Detection results by YOLOv8m; (a″) Detection results by the proposed algorithm. (b) Original image; (b′) Detection results by YOLOv8m; (b″) Detection results by the proposed algorithm. (c) Original image; (c′) Detection results by YOLOv8m; (c″) Detection results by the proposed algorithm.

The visual results demonstrated that the detection performance of the improved algorithm was significantly better than that of YOLOv8m in scenarios with dense plants, complex backgrounds, and illumination variations. In the comparison between subfigures (a′) and (a″), YOLOv8m (a′) exhibited missed detections along the roof–shadow boundary and a notably weak response to low-contrast poppy plants near the ground. Similarly, when compared with (b″), YOLOv8m (b’) showed overlapping bounding boxes, boundary misalignments, and localized false positives. Furthermore, the comparison between (c’) and (c″) highlighted the performance gap under conditions of low illumination and severe occlusion, illustrating the superior robustness of the improved model.

3.6. Statistical Significance Analysis

To further ensure robust model evaluation, five-fold cross-validation was conducted within the training set. Specifically, the training set was evenly divided into five non-overlapping folds. In each iteration, one fold was used as a temporary validation set while the remaining four folds were used for training. This process was repeated five times so that each fold served as the validation set once.

The five-fold cross-validation results indicate that the baseline YOLOv8m model achieved an average mAP@0.5 of 0.976 ± 0.005 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.818 ± 0.007, whereas the improved model reached 0.989 ± 0.003 and 0.850 ± 0.013, respectively, showing consistent improvement.

Statistical analysis using a one-sided paired t-test revealed t(4) = 6.420, p = 0.0015 for mAP@0.5 and t(4) = 4.078, p = 0.0076 for mAP@0.5:0.95. The one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test yielded W = 15, p = 0.0313 for both metrics. These results confirm that the improvements in both mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 are statistically significant at the α= 0.05 level. Therefore, the proposed modifications reliably enhance YOLOv8m’s detection performance for small poppy plants.

3.7. Deployment

To verify the feasibility and application potential of the proposed model on embedded platforms, this study deployed the improved model on a Raspberry Pi 5 for poppy plant detection experiments. The device is equipped with a Quad-core Arm Cortex-A76 CPU running at 2.4 GHz, 6 GB of LPDDR4X-4267 SDRAM, a VideoCore VII graphics card, a Raspberry Pi Image Sensor Processor, and dual 4Kp60 HDMI display outputs. The model achieved an average inference time of 1101.61 ms per image, demonstrating stable operation and consistent detection accuracy under resource-constrained conditions. Although the current inference speed is limited, it can be further optimized through model pruning, quantization, or hardware acceleration, indicating the model’s potential for practical edge deployment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Collaborative Mechanism of the Proposed Algorithm

Experimental results demonstrated that each module in our method contributed positively to model performance. The C2f_ECA module enhanced feature selectivity through local cross-channel interaction mechanisms, enabling the backbone network to focus more effectively on fine-grained textures of poppy plants. The BiFPN architecture incorporated a learnable weighting mechanism into multi-scale feature fusion, facilitating bidirectional interaction between low-level details and high-level semantics, thereby providing more consistent feature representations for subsequent predictions. However, when used alone, BiFPN lacks support for channel feature enhancement, resulting in a decrease in mAP@0.5:0.95. Its repeated top–down and bottom–up feature aggregation can weaken the representation of fine-grained local features, particularly in scenarios with densely distributed small objects and complex backgrounds, thereby limiting its effectiveness for high-resolution small-object detection. The WIoU loss introduced a dynamic non-monotonic focusing mechanism during the regression stage, which adaptively allocated gradients based on sample quality, thereby enhancing the stability of bounding box regression. The P2 high-resolution detection head significantly enhanced the pixel-level representation of ultra-small objects in feature maps, enabling the model to more accurately identify densely distributed poppy plants.

When the aforementioned modules work collaboratively, the network forms a multi-level optimization pipeline characterized by “feature enhancement → scale fusion → boundary constraint → high-resolution detection.” ECA provided highly discriminative channel-wise inputs, BiFPN enabled cross-scale transmission of semantic and spatial features, WIoU stabilized regression optimization, and the P2 layer enhanced the detection response for small objects. Collectively, the modules complemented each other along the data flow, producing an end-to-end optimization pathway that experimentally improved both detection accuracy and stability.

Current methods for poppy detection in UAV imagery remain significantly limited in terms of feature representation, multi-scale robustness, and small object detection capability. Zhang et al. [28] improved feature modeling capability by integrating an HLA attention module with a repetitive learning strategy. However, the repetitive learning approach relied primarily on data-driven mechanisms and only proved effective in specific scenarios, failing to achieve texture feature enhancement at the network structural level. Pérez-Porras et al. [29] validated the applicability of YOLO series models in early-stage poppy detection within wheat fields. Nevertheless, their method did not involve feature enhancement or structural network improvements, making it difficult to overcome the structural bottleneck caused by the sparse features of small-sized poppy plants. Although the SD-YOLO model proposed by Yao and Wang [30] improved poppy detection through multi-module enhancements, it only achieved an mAP of 72.9% and a recall rate of 64%, still exhibiting high risks of false detections and missed detections in complex scenarios. The approach by Zhang et al. [31] only introduced a multi-scale attention mechanism into the backbone network, with improvements confined to a single module. Its small-object detection accuracy is 91.4%. It failed to collaboratively optimize feature fusion and regression layers, resulting in limited enhancement in small object detection capability. Wang et al. [32] addressed occlusion and viewpoint deformation in complex aerial scenes by improving detection performance through feature enhancement, vegetation index fusion, and loss function optimization, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 85.7%. However, their optimizations primarily focused on feature extraction and loss function design, lacking improvements to regression layers and detection heads, which constrained the model’s detection accuracy for small and dense objects.

Compared to previous approaches, the improved YOLOv8 model presented in this paper features a more systematic and holistic architectural design. By independently enhancing key components—including the attention mechanism, feature fusion strategy, loss function, and small-object detection head—the model effectively addressed performance bottlenecks at different levels. This achieves progressive refinements throughout the pipeline, from feature extraction and multi-scale fusion to boundary optimization and small-object detection. When these modules operated collaboratively, their benefits were not simply additive but generated synergistic effects through structural complementarity and data flow interactions, thereby significantly boosting overall detection performance. This evidence indicates that the modular design strategy establishes an effective pathway from localized optimization to holistic performance improvement for small object detection in complex UAV aerial scenarios.

4.2. Potential Applications and Limitations

This approach constructed a detection system with more stable performance. In our experiments, the method maintained high detection accuracy and stability under complex aerial photography conditions, providing a generalizable and systematic optimization approach for UAV platforms in tasks such as poppy plant identification, agricultural monitoring, and ecological inspection. The research results demonstrated that the multi-module collaborative mechanism exhibited good adaptability and robustness in complex agricultural scenarios, laying a technical foundation for the subsequent automation and intelligence of crop recognition.

However, several limitations of this study remain and warrant further investigation. First, the incorporation of attention mechanisms, multi-scale feature fusion structures, and high-resolution detection heads increases the model’s computational complexity and inference latency, which may hinder its ability to meet real-time requirements on resource-constrained UAV edge devices. The current framework still exhibits deficiencies in lightweight design and efficient deployment, indicating the need for further exploration of pruning, quantization, or structural optimization strategies.

Second, although the dataset covers multiple time periods and complex scenes, its overall scope has been confined to specific regions and a limited number of seasons. The lack of environmental diversity may lead to overfitting, resulting in an overestimation of accuracy and restricting the model’s generalization across different regions, seasons, and extreme conditions.

Moreover, the ablation experiments were not repeated, stability metrics such as mean and variance were not reported, and the model’s sensitivity to hyperparameters was not evaluated, which could further exacerbate overfitting. Future work should incorporate repeated experiments, statistical analyses, and data augmentation to systematically assess model stability and generalization.

5. Conclusions

Aiming at the challenges of dense distribution, significant size variation, and strong background interference in small-object recognition of poppy plants from UAV aerial imagery, this paper has proposed an improved small-object detection method based on YOLOv8. This method featured a collaborative design centered around four key aspects: feature representation, feature fusion, regression optimization, and detection scale. It introduced the C2f_ECA module into the backbone network to enhance channel-wise semantic selectivity, adopted BiFPN in the neck structure to strengthen cross-scale interaction, incorporated the WIoU loss into the regression branch to improve localization stability, and added a P2 high-resolution detection layer to enhance the response to tiny objects.

To validate the effectiveness of the method, a systematic experimental evaluation was conducted. Under five-fold cross-validation, the results showed that the proposed model achieved mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.989 ± 0.003 and 0.850 ± 0.013, respectively, with average increases of 1.3 and 3.2 percentage points over YOLOv8m. In addition, the paired t-test results indicated that the improvements in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 are both statistically significant at the α = 0.05 level, further confirming the reliability of the model performance enhancements. The model maintained high detection accuracy under conditions of dense small objects and complex backgrounds. Analysis of the modular collaborative mechanism indicated that feature extraction, multi-scale fusion, boundary optimization, and small-object detection created complementary gains in small-target recognition, constituting the core source of the performance improvement.

Future work will focus on the following directions: (1) Further balancing model performance and computational cost by exploring structural pruning, lightweight attention mechanisms, and knowledge distillation strategies to support real-time onboard deployment; (2) Expanding the collection of training data encompassing multiple regions, scales, and temporal phases to construct a more representative agricultural scene sample library, thereby enhancing the model’s adaptability to different crops, terrains, and lighting variations. (3) Conducting repeated experiments and statistical analyses to evaluate the model’s stability and robustness, as well as systematically investigating the sensitivity of the model to hyperparameter settings, in order to ensure reliable performance under various training configurations. Overall, this study has provided an effective small-object detection solution ranging from local feature enhancement to full pipeline collaborative optimization, offering a transferable technical foundation for the intelligent monitoring of agricultural vegetation targets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.F. and L.Y.; data curation, X.F. and H.Z.; investigation, X.F.; methodology, X.F. and H.Z.; supervision, L.Y.; validation, X.F. and C.W.; writing—original draft, X.F. and C.W.; writing—review and editing, X.F., L.Y., C.W., R.G., Y.M. and H.J.; literature search, R.G. and H.J.; data collection, R.G. and Y.M.; visualization, Y.M. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Project of Yunnan Province Applied Basic Research Program (funding number: 202401AS070034), Yunnan Province Forest and Grass Science and Technology Innovation Joint Special Project (funding number: 202404CB090002).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1440–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.Q.; He, K.M.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, Y.H.; Cheng, T. Lightweight object detection algorithm for uav aerial imagery. Sensors 2023, 23, 5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, M.; Zhu, G.Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, P.Y.; Yan, J.H. FFCA-YOLO for small object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.J.; Yun, L.J.; Chen, Z.Q.; Zhong, T.Z. Improved YOLOv5s small object detection algorithmin UAV view. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2024, 60, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.H.; Hao, Z.Y. Improved YOLOv8 aerial small target detection method: CRP-YOLO. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2024, 60, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Jia, M.B.; Zhou, L.Y. Improved YOLOv8s based pedestrian detection method in the perspective of UAV. Mod. Electron. Technol. 2024, 47, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.Y.; Su, H.R.; Wu, Z.Y.; Wang, T.J. Road traffic small target vehicle detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8. Comput. Eng. 2025, 51, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z.; Qiao, H.B.; Xi, L.; Ma, C.W.; Xu, X.; Hui, X.H.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H. Detecting small objects for field crop pests using improved YOLOv8. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, G.; Feng, Y.W.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Z.H. SRNet-YOLO: A model for detecting tiny and very tiny pests in cotton fields based on super-resolution reconstruction. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1416940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.E.; Ye, W.; Pan, Y.N.; Wang, J.Y.; Qiu, H.P.; Wang, H.K.; Li, Z.X.; Chen, T.H. GCPDFFNet: Small object detection for rice blast recognition. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.X.; Huang, C.P.; Hu, G.S.; Su, B.B.; Yang, X.J. Detection of Fusarium head blight in wheat using UAV remote sensing based on parallel channel space attention. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.D.; Huang, D.Y.; Wu, L.B.; Cheng, Z.X.; Ye, D.P.; Weng, H.Y. UAV rice panicle blast detection based on enhanced feature representation and optimized attention mechanism. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.X.; Dong, H.; Bai, S.Y.; Yu, Y.; Duan, Q.W. Image recognition and classification of farmland pests based on improved Yolox-tiny algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Chen, Y.P.; Xia, Y.X.; Wang, H.Q.; Jin, R.H.; Wang, C.; Fan, Z.P.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, B.J. Detection of small foreign objects in Pu-erh sun-dried green tea: An enhanced YOLOv8 neural network model based on deep learning. Food Control 2025, 168, 110890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Shi, F.H. Perceptive teacher: Semi-supervised small object detection of brassica chinensis seedlings and pest infestations. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, K.; Pazhanivelan, P.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Prabu, P.C. YOLO deep learning algorithm for object detection in agriculture: A review. J. Agric. Eng. 2024, 55, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xia, Y.T.; Xia, L.L.; Wang, Q.Y.; Gu, L.C. Dual discriminator GAN-based synthetic crop disease image generation for precise crop disease identification. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara, K.; Nakane, C.; Ebisawa, H.; Kuroda, T.; Iwaki, Y.; Utsumi, T.; Nomura, Y.; Koike, M.; Mineno, H. D4: Text-guided diffusion model-based domain adaptive data augmentation for vineyard shoot detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 230, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, A.; Kim, J.H.; Mitani, T.; Odagawa, S.; Takeda, T.; Kobayashi, C.; Kashimura, O. A study on detecting the poppy field using hyperspectral remote sensing techniques. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Munich, Germany, 22–27 July 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 4829–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Montes-Borrego, M.; Landa, B.B.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Detection of downy mildew of opium poppy using high-resolution multi-spectral and thermal imagery acquired with an unmanned aerial vehicle. Precis. Agric. 2014, 15, 639–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Tian, Y.C.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, F.F.; Yang, G. Opium poppy detection using deep learning. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tian, Y.C.; Yuan, C.; Yin, K.; Yang, G.; Wen, M.P. Improved UAV opium poppy detection using an updated YOLOv3 model. Sensors 2019, 19, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Başayiğit, L. Determination of opium poppy (Papaver Somniferum) parcels using high-resolution satellite imagery. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2019, 47, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Xia, W.D.; Xie, G.Q.; Xiang, S. Fast opium poppy detection in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) imagery based on deep neural network. Drones 2023, 7, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Porras, F.J.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; López-Granados, F.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.J. Early and on-ground image-based detection of poppy (Papaver rhoeas) in wheat using YOLO architectures. Weed Sci. 2022, 71, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.D.; Wang, W.J. Detection and recognition of poppy in UAV imagery based on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML), Shenzhen, China, 22–24 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.y.; Luo, D.w.; Zhou, L.; Dejiangmo. Opium poppy image detection based on improved YOLOV5. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Digital Home (ISDH), Guilin, China, 1–3 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, H.Y.; Wu, F.; Wang, J. YOLO-poppy: Opium poppy detection algorithm for complex aerial scenes. In Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application (ICCEA), Hangzhou, China, 25–27 April 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.X.; Pang, R.M.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Xu, Z.W.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: Bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.10051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Mark Liao, H.Y.; Wu, Y.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Hsieh, J.W.; Yeh, I.H. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, P.; Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Searching for activation functions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.05941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.M.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.F.; Shi, J.P.; Jia, J.Y. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.L.; Wu, B.G.; Zhu, P.F.; Li, P.H.; Zuo, W.M.; Hu, Q.H. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 11534–11542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, D.; Nalamada, T.; Arasanipalai, A.U.; Hou, Q.B. Rotate to attend: Convolutional triplet attention module. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3139–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, X.L.; Yang, J. Spatial group-wise enhance: Improving semantic feature learning in convolutional networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.09646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Yang, Y.B. SA-Net: Shuffle attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021—2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Shao, Z.R.; Hoffmann, N. Global attention mechanism: Retain information to enhance channel-spatial interactions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.05561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.H.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.Z.; Ye, R.G.; Ren, D.W. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 12993–13000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU loss: More powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Xu, C.; Yang, W.; Yu, L. A normalized Gaussian Wasserstein distance for tiny object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).