Optimizing Caffeine Treatments for Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Management in Laboratory Bioassays

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Samples

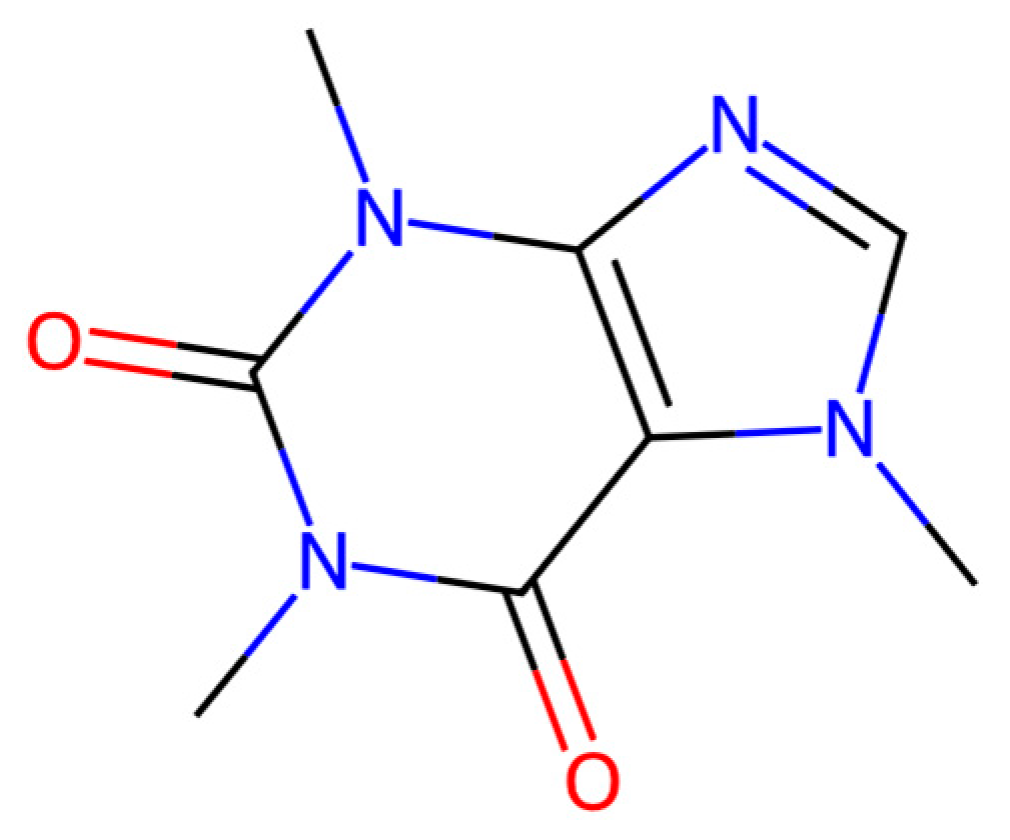

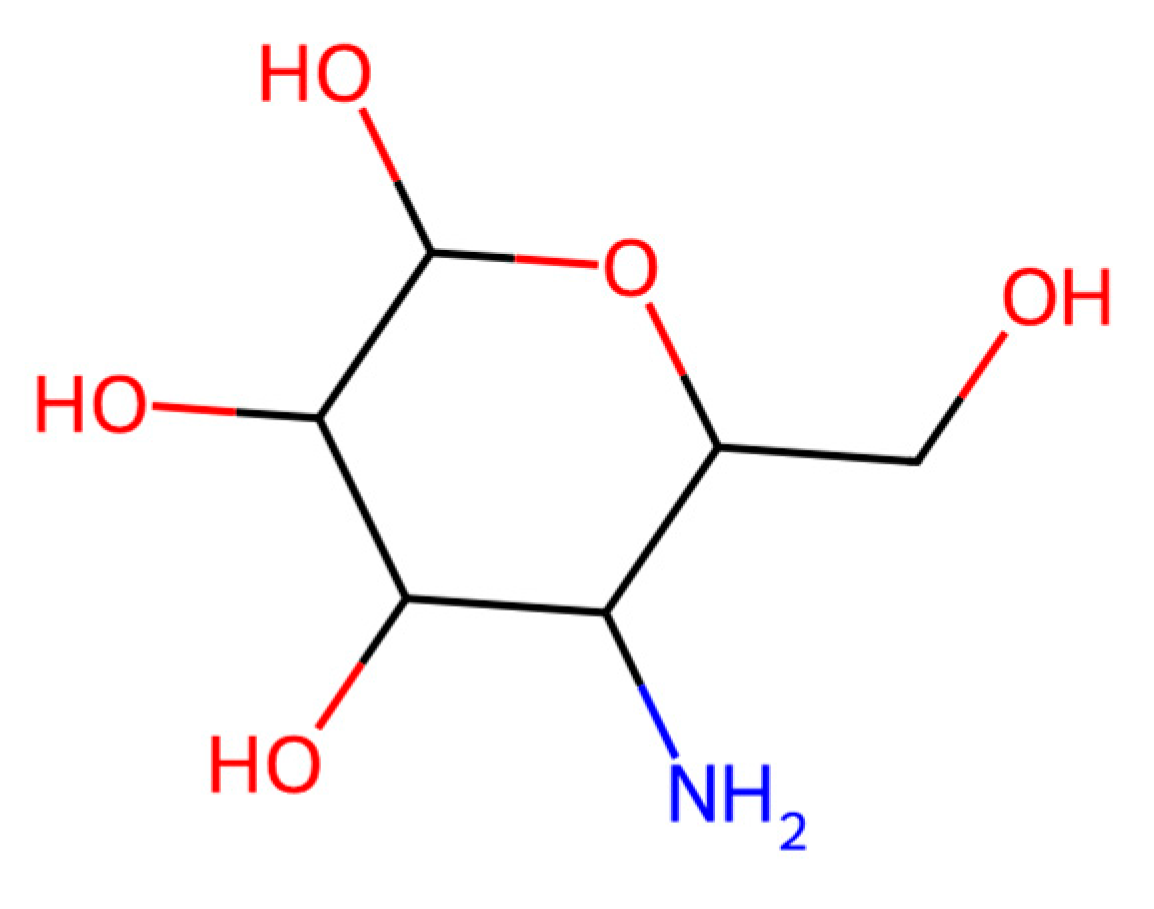

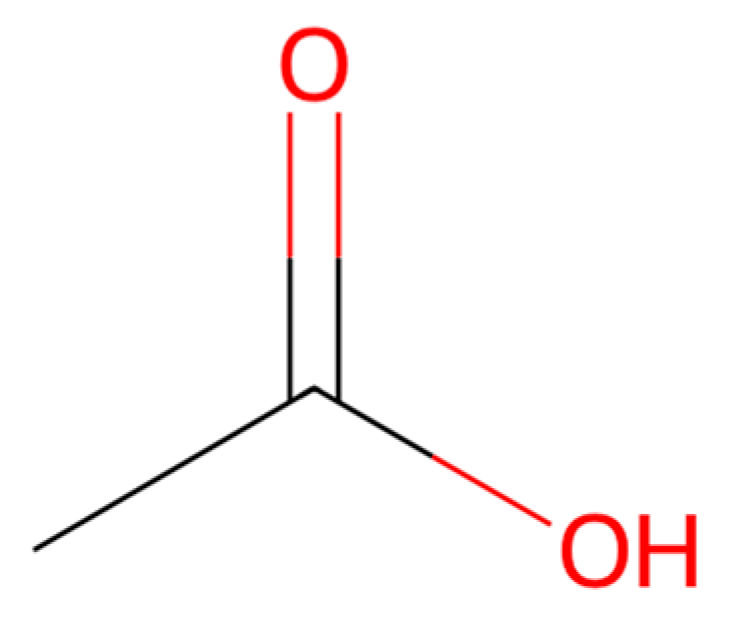

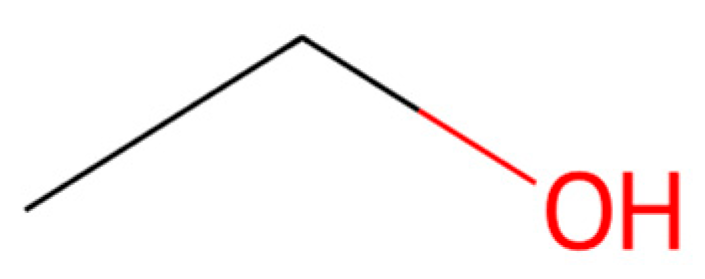

2.2. Treatment Preparation

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. The Assessment of the Results

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, D.-H.; Short, B.D.; Joseph, S.V.; Bergh, J.C.; Leskey, T.C. Review of the Biology, Ecology, and Management of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leskey, T.C.; Nielsen, A.L. Impact of the Invasive Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in North America and Europe: History, Biology, Ecology, and Management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoebeke, E.R.; Carter, M.E. Halyomorpha halys (Stål) (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae): A Polyphagous Plant Pest from Asia Newly Detected in North America. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash 2003, 105, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Konjević, A. First Records of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in the Republic of North Macedonia. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2020, 72, 687–690. [Google Scholar]

- Derjanschi, V.; Chimișliu, C. The brown marmorated stink bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) (Heteroptera, Pentatomidae)—A new invasive alien species in the fauna of the Republic of Moldova. Bul. Ştiinţific Rev. Etnogr. Ştiinţele Nat. Muzeol. 2019, 30, 18–22. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1290055 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Šapina, I.; Šerić Jelaska, L. First Report of the Invasive Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Croatia. Bull. OEPP/EPPO Bull. 2018, 48, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajač Živković, I.; Skendžić, S.; Lemić, D. Rapid Spread and First Massive Occurrence of Halyomorpha halys (Stål, 1855) in Agricultural Production in Croatia. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajač Beus, M.; Lemić, D.; Skendžić, S.; Čirjak, D.; Pajač Živković, I. The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)—A Major Challenge for Global Plant Production. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriticos, D.J.; Kean, J.M.; Phillips, C.B.; Senay, S.D.; Acosta, H.; Haye, T. The Potential Global Distribution of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys, a Critical Threat to Plant Biosecurity. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rot, M.; Persolja, J.; Bohinc, T.; Žežlina, I.; Trdan, S. Seasonal Dynamics of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), in Apple Orchards of Western Slovenia Using Two Trap Types. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, M.; Reding, K.; Pick, L. Establishment of Molecular Genetic Approaches to Study Gene Expression and Function in an Invasive Hemipteran, Halyomorpha halys. EvoDevo 2017, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keszthelyi, S.; Gibicsár, S.; Jócsák, I.; Fajtai, D.; Donkó, T. Analysis of the Destructive Effect of the Halyomorpha halys Saliva on Tomato by Computer Tomographical Imaging and Antioxidant Capacity Measurement. Biology 2022, 11, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, K.B.; Bergh, C.J.; Bergmann, E.J.; Biddinger, D.J.; Dieckhoff, C.; Dively, G.P.; Fraser, H.; Gariepy, T.; Hamilton, G.C.; Haye, T.; et al. Biology, Ecology, and Management of Brown Marmorated Stink Bug (Halyomorpha halys) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2014, 5, A1–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, W.R., III; Blaauw, B.R.; Short, B.D.; Nielsen, A.L.; Bergh, J.C.; Krawczyk, G.; Park, Y.-L.; Butler, B.; Khrimian, A.; Leskey, T.C. Successful Management of Halyomorpha halys (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in Commercial Apple Orchards with an Attract-and-Kill Strategy. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candian, V.; Pansa, M.G.; Briano, R.; Peano, C.; Tedeschi, R.; Tavella, L. Exclusion Nets: A Promising Tool to Prevent Halyomorpha halys from Damaging Nectarines and Apples in NW Italy. Bull. Insectology 2018, 71, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, V.; Yonow, T.; Paull, C.; Talamas, E.J.; Avila, G.A.; Hoelmer, K.A. Preempting the Arrival of the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys: Biological Control Options for Australia. Insects 2021, 12, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, S.V.; Dho, M.; Orrù, B.; Gonella, E.; Alma, A. Symbiont-Targeted Control of Halyomorpha halys Does Not Affect Local Insect Diversity in a Hazelnut Orchard. Insects 2025, 16, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurić, S.; Vincenković, M.; Marijan, M.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Galešić, M.A.; Orešković, M.; Lemić, D.; Čirjak, D.; Pajač Živković, I. Effectiveness of Aqueous Coffee Extract and Caffeine in Controlling Phytophagous Heteropteran Species. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2023, 21, 1499–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Uefuji, H.; Ogita, S.; Sano, H. Transgenic Tobacco Plants Producing Caffeine: A Potential New Strategy for Insect Pest Control. Transgenic Res. 2006, 15, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceja-Navarro, J.; Vega, F.; Karaoz, U.; Hao, Z.; Jenkins, S.; Lim, H.C.; Kosina, P.; Infante, F.; Northen, T.R.; Brodie, E.L. Gut Microbiota Mediate Caffeine Detoxification in the Primary Insect Pest of Coffee. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, J.A. Caffeine and Related Methylxanthines: Possible Naturally Occurring Pesticides. Science 1984, 226, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora, C.E.; Tapias, J.; Jaramillo, J.; Medina, R.; González, S.; Restrepo, T.; Casanova, H.; Benavides, P. A Novel Caffeine Oleate Formulation as an Insecticide to Control Coffee Berry Borer, Hypothenemus hampei, and Other Coffee Pests. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque, P.; Casanova, H.; Ortiz, C.; Henao, B.; Peláez, C. Insecticidal Activity of Caffeine Aqueous Solutions and Caffeine Oleate Emulsions against Drosophila melanogaster and Hypothenemus hampei. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6918–6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanasoponkul, W.; Changbunjong, T.; Sukkurd, R.; Saiwichai, T. Spent Coffee Grounds and Novaluron Are Toxic to Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Larvae. Insects 2023, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusoff, S.N.M.; Kamari, A.; Aljafree, N.F.A. A Review of Materials Used as Carrier Agents in Pesticide Formulations. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 13, 2977–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Chitosan: Sources, Processing and Modification Techniques. Gels 2022, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenaim, L.; Conti, B. Chitosan as a Control Tool for Insect Pest Management: A Review. Insects 2023, 14, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Kandasamy, S.; Rajarajeswaran, J.; Sundaram, T.; Bjeljac, M.; Surendran, R.P.; Ganesan, A.R. Chitosan-Based Insecticide Formulations for Insect Pest Control Management: A Review of Current Trends and Challenges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, X. Risks of Caffeine Residues in the Environment: Necessity for a Targeted Ecopharmacovigilance Program. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Du, Y.; Fan, L.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y. Chitosan–Metal Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents: Synthesis, Characterization and Structure–Activity Study. Polym. Bull. 2005, 55, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenne, M.; Kambham, M.; Tollamadugu, N.V.K.V.P.; Karanam, H.P.; Tirupati, M.K.; Reddy Balam, R.; Shameer, S.; Yagireddy, M. The Use of Slow-Releasing Nanoparticle Encapsulated Azadirachtin Formulations for the Management of Caryedon serratus O. (Groundnut Bruchid). IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 12, 963–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, M.E.I. Preparation and antimicrobial activity of some chitosan–metal complexes against some plant pathogenic bacteria and fungi. J. Pest Control Environ. Sci. 2010, 18, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Arachchi, J.K.V.; Jeon, Y.J. Food Applications of Chitin and Chitosan. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerberg, J.H.; Al-Tikriti, Y.; Ragnarsson, G.; Bergström, C.A.S. Ethanol Effects on Apparent Solubility of Poorly Soluble Drugs in Simulated Intestinal Fluid. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 1942–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, C.N.; Galván, M.V.; Solier, Y.N.; Inalbon, M.C.; Zanuttini, M.A.; Mocchiutti, P. High-Strength Biobased Films Prepared from Xylan/Chitosan Polyelectrolyte Complexes in the Presence of Ethanol. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poshina, D.N.; Khadyko, I.A.; Sukhova, A.A.; Serov, I.V.; Zabivalova, N.M.; Skorik, Y.A. Needleless Electrospinning of a Chitosan Lactate Aqueous Solution: Influence of Solution Composition and Spinning Parameters. Technologies 2020, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.J.L.; Ojeda, C.; Cirelli, A.F. Advances in Surfactants for Agrochemicals. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2014, 12, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A Method of Computing the Effectiveness of an Insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gylling Data Management Inc. ARM 2025® GDM Software, Revision 2025.2 (16 October 2025); Gylling Data Management Inc.: Brookings, SD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Parisi, O.I.; Puoci, F.; Restuccia, D.; Farina, G.; Iemma, F.; Picci, N. Polyphenols and Their Formulations. In Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padamini, R.; Bhumita, P.; Hazarika, S.; Nm, R.; Gowda, G.R.V.; Chaturvedi, K.; Panigrahi, C.K.; Karanwal, R. Exploring the Role of Chitosan: A Natural Solution for Plant Disease and Insect Management. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2024, 24, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkawy, A.; Barreiro, M.F.; Rodrigues, A.E. Chitosan-Based Pickering Emulsions and Their Applications: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thadathil, N.; Velappan, S.P. Recent Developments in Chitosanase Research and Its Biotechnological Applications: A Review. Food Chem. 2014, 150, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyereisen, R. Insect P450 Enzymes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999, 44, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafont, R.; Balducci, C.; Dinan, L. Ecdysteroids. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 1267–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, M.E.; Bansal, R.; Benoit, J.B.; Blackburn, M.B.; Chao, H.; Chen, M.; Cheng, S.; Childers, C.; Dinh, H.; Doddapaneni, H.V.; et al. Brown Marmorated Stink Bug, Halyomorpha halys (Stål), Genome: Putative Underpinnings of Polyphagy, Insecticide Resistance Potential and Biology of a Top Worldwide Pest. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Negro, A.S. Environmental Assessment for Food Contact Notification, FCN 1783; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/food/published/Environmental-Assessment-for-Food-Contact-Notification-No.-1783.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Sarmah, K.; Anbalagan, T.; Marimuthu, M.; Mariappan, P.; Angappan, S.; Vaithiyanathan, S. Innovative Formulation Strategies for Botanical- and Essential Oil-Based Insecticides. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment No. | Sample Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Distilled water (control) |

| 2 | 1% CAF + H2O |

| 3 | 3% CAF + H2O |

| 4 | 5% CAF + H2O |

| 5 | 1% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC |

| 6 | 1% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 5% ET |

| 7 | 3% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 5% ET |

| 8 | 3% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC |

| 9 | 5% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 3% ET |

| 10 | 5% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC |

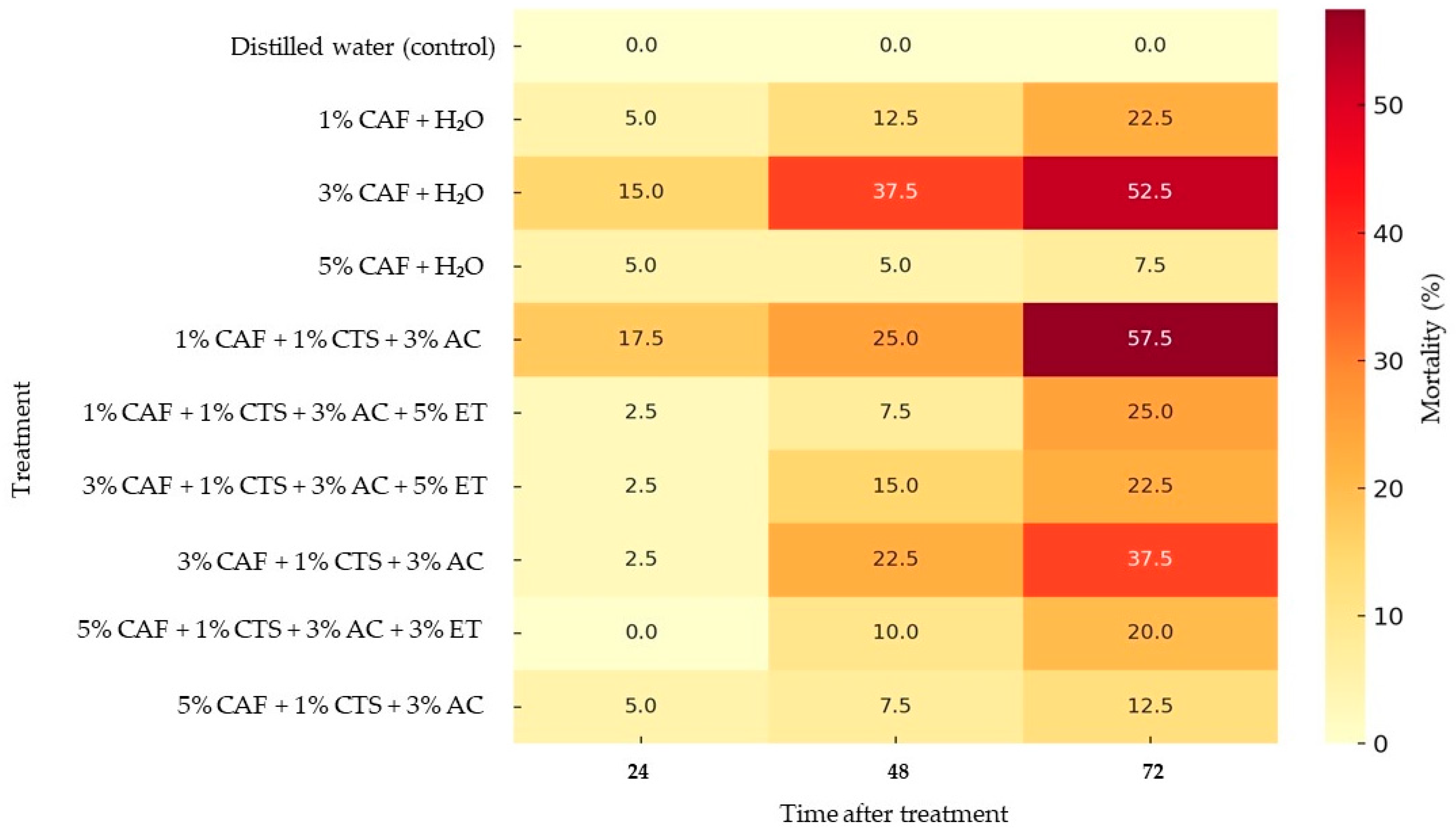

| Treatment | Efficacy (%) | Confidence Level 95% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | |

| 1% CAF + H2O | 5.0 ± 2.9 ns * | 12.5 ± 4.8 ab | 22.5 ± 13.2 bcd | 0.0–17.5 | 0.0–33.2 | 0.0–78.9 |

| 3% CAF+ H2O | 15.0 ± 6.5 ns | 37.5 ± 6.3 a | 52.5 ± 4.8 ab | 0.0–43.9 | 10.3–64.7 | 31.8–73.2 |

| 5% CAF + H2O | 5.0 ± 2.9 ns | 5.0 ± 2.9 b | 7.5 ± 4.8 cd | 0.0–17.5 | 0.0–17.5 | 0.0–28.2 |

| 1% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC | 17.5 ± 8.5 ns | 25.0 ± 6.5 ab | 57.5 ± 8.5 a | 0.0–54.1 | 0.0–53.9 | 20.9–94.1 |

| 1% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 5% ET | 2.5 ± 2.5 ns | 7.5 ± 4.8 b | 25.0 ± 8.7 bcd | 0.0–13.3 | 0.0–28.2 | 0.0–62.5 |

| 3% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 5% ET | 2.5 ± 2.5 ns | 15.0 ± 8.7 ab | 22.5 ± 7.5 bcd | 0.0–13.3 | 0.0–52.5 | 0.0–54.8 |

| 3% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC | 2.5 ± 2.5 ns | 22.5 ± 6.3 ab | 37.5 ± 4.8 abc | 0.0–13.3 | 0.0–47.6 | 16.8–58.2 |

| 5% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC + 3% ET | 0.0 ± 0.0 ns | 10.0 ± 4.1 b | 20.0 ± 4.1 cd | 0.0–0.0 | 0.0–27.6 | 2.4–37.6 |

| 5% CAF + 1% CTS + 3% AC | 5.0 ± 2.9 ns | 7.5 ± 2.5 b | 12.5 ± 4.8 cd | 0.0–17.5 | 0.0–18.3 | 0.0–33.2 |

| Tukey’s HSD p = 0.05 | 19.68 | 26.59 | 31.46 | |||

| Standard Deviation | 8.09 | 10.93 | 12.94 | |||

| Coefficient of variation CV | 140.71 | 74.12 | 49.28 | |||

| Levene’s F ^ | 1.456 | 0.524 | 1.954 | |||

| Levene’s Prob(F) | 0.209 | 0.845 | 0.082 | |||

| Shapiro–Wilk ^ | 0.9476 | 0.981 | 0.9839 | |||

| P(Shapiro–Wilk) ^ | 0.0629 | 0.7273 | 0.83 | |||

| Skewness ^ | 0.9289 * | 0.4195 | 0.3874 | |||

| P(Skewness) ^ | 0.0215 * | 0.2859 | 0.3237 | |||

| Kurtosis ^ | 2.1832 * | 0.6552 | 0.1729 | |||

| P(Kurtosis) ^ | 0.0065 * | 0.3938 | 0.8212 | |||

| Replicate F | 1.057 | 0.411 | 2.804 | |||

| Replicate Prob(F) | 0.3838 | 0.7462 | 0.0588 | |||

| Treatment F | 2.041 | 3.739 | 7.579 | |||

| Treatment Prob(F) | 0.0735 | 0.0037 | 0.0001 | |||

| Partial η2 (treatment) | 0.405 | 0.555 | 0.716 | |||

| Cohen’s f | 0.95 | 1.29 | 1.84 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz, M.K.R.; Lemic, D.; Vinceković, M.; Pajač Beus, M.; Viric Gasparic, H.; Bažok, R.; Pajač Živković, I. Optimizing Caffeine Treatments for Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Management in Laboratory Bioassays. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122867

Cruz MKR, Lemic D, Vinceković M, Pajač Beus M, Viric Gasparic H, Bažok R, Pajač Živković I. Optimizing Caffeine Treatments for Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Management in Laboratory Bioassays. Agronomy. 2025; 15(12):2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122867

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz, Miko Keno R., Darija Lemic, Marko Vinceković, Martina Pajač Beus, Helena Viric Gasparic, Renata Bažok, and Ivana Pajač Živković. 2025. "Optimizing Caffeine Treatments for Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Management in Laboratory Bioassays" Agronomy 15, no. 12: 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122867

APA StyleCruz, M. K. R., Lemic, D., Vinceković, M., Pajač Beus, M., Viric Gasparic, H., Bažok, R., & Pajač Živković, I. (2025). Optimizing Caffeine Treatments for Brown Marmorated Stink Bug Management in Laboratory Bioassays. Agronomy, 15(12), 2867. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15122867