Abstract

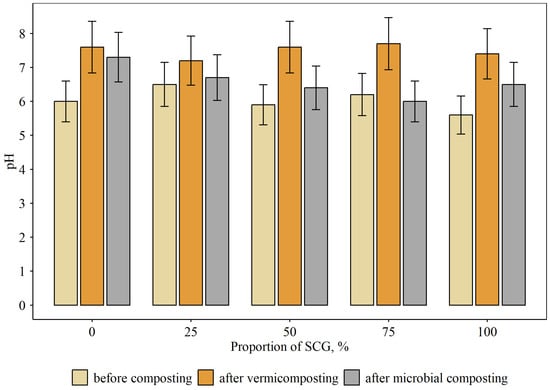

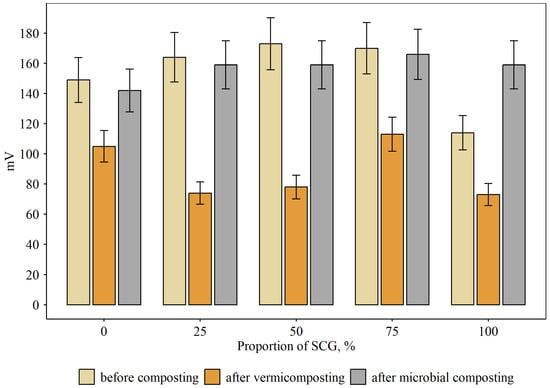

Annually, up to 15 million tons of coffee production waste are produced worldwide. Among them are spent coffee grounds (SCG), which have the potential to be recycled and used as organic fertilizers. However, their direct application to soil is limited due to the presence of ecotoxic compounds (phenols, tannins, and caffeine). Composting is a promising approach; however, the highly variable properties of the raw coffee materials require the selection of optimal production and application modes. In this study, we performed two composting methods for SCG, i.e., vermicomposting and microbial composting, in mixtures with co-composting substrate at five SCG/substrate ratios (0, 25, 50, 75, and 100% SCG). First, the acute toxicity of raw SGC and its mixtures to earthworm Eisenia andrei was evaluated. After 30 days of composting, chemical and microbiological properties, including pH, RedOx potential (Eh), organic carbon (Corg), lignin content, bacteria count, diversity, and potential metabolic activity, were determined in the end products. As composting went on, the pH increased from 5.6–6.2 to 6.0–7.3 and 7.4–7.7 under microbial composting and vermicomposting, respectively. RedOx potential levels achieved 142–166 mV for microbial composting and 73–113 mV for vermicomposting. Organic matter (OM) content reached 86–94%, with an increasing proportion of lignin, demonstrating the decomposition of more readily accessible organic matter. Vermicomposting and microbial composting produced chemically safe and microbiologically highly active composts. An initial SCG content of 25–50% of the compost mixture’s weight yielded the most favorable properties for the resulting compost (high organic matter content and optimal pH levels). Due to the high biological activity of both composting methods, the resultant composts are likely to have a positive effect on plant growth and development and soil health when used as organic nutrient resources.

1. Introduction

Large amounts of wastes are increasingly accumulating worldwide because of urbanization and population growth. Wastes that are high in nutrients and organic matter may be potentially utilized in agriculture as soil amendments. Among these are organic wastes from the coffee industry, including spent coffee grounds (SCG).

Coffee is produced in more than 80 countries worldwide and is the second largest commercial crop exported by developing countries [1]. According to the International Coffee Organization, global coffee consumption reached approximately 10 million tons of green beans by 2022 [2]. Coffee industry waste includes primarily pulp, coffee husks, and spent coffee grounds, generated at coffee processing plants and at points of sale [3]. According to current estimates, the annual global production of coffee waste is up to 15 million tons [4,5]. Conventional disposal techniques for SCG include landfilling and incineration, which frequently result in environmental problems such as greenhouse gas emissions and the release of ecotoxic compounds [6]. Given the high costs of landfilling, and stricter environmental laws, the coffee industry unavoidably needs more economical and ecologically appropriate methods of disposing of SCG.

Recently, the practice of applying SCG as mulch and organic soil amendment has been gaining interest [7,8]. SCG are rich in carbon (40–50%) and nitrogen (1–2.5%); organic matter is dominated by hemicellulose (about 38%) and cellulose (9%), polysaccharides, and lipids, as well as phenolic compounds, tannins, and caffeine (1–2%) [9,10]. However, due to the high content of ecotoxic substances, such as phenols, tannins, and caffeine, there are several limitations and environmental concerns in using raw SCG in agriculture [11,12]. To reduce the toxicity of SCG, various technologies of composting and co-composting with other organic wastes are practiced [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. One of the technologies that accelerates the composting process and improves the compost quality is the addition of microbial inoculants [13,14,15,16]. Many methods have been published for composting SCG with the addition of microorganisms of different groups, in most cases Bacillus, Streptomyces, Corynebacterium, and other bacteria that promote plant growth and development [17,18,19]. SCG microbial composting allows for an increased speed and degree of material processing, reduced toxic content, and the production of highly biologically active fertilizer.

Another approach for managing SCG is vermicomposting [20,21,22]. Vermicomposting is a process of recycling organic waste using earthworms, which combines the activities of microorganisms and worms [23]. Fragmentation of the organic substrate increases microbial activity [24,25], substrate oxidation and decomposition, and stabilization with mucilage, contributing to the formation of a nutrient-rich organic fertilizer [26]. Compared to traditional composting, the vermicomposting of coffee waste can be 2–3 times faster, providing more stable end-product characteristics and reduced nitrogen loss [6].

Summarizing findings from previous studies on the most effective composting methods for coffee waste and the performance of the resulting fertilizers is challenging due to the diversity of experimental approaches, raw materials, and plant species [27]. In general, both composting and vermicomposting have been reported to yield fertilizers with high content of organic carbon, nutrients (N, P, and K), C/N ratios of 10–20, neutral pH values, and low levels of toxicity [14,22,28,29,30,31]. Typically, composts from coffee waste contain a high diversity of microorganisms, including plant-growth-promoting microorganisms. However, in some cases, because of poor composting techniques, the end-product SCG-based compost was characterized by low N and P content, unsuitable pH values for cultivated plants, and sometimes excessive levels of caffeine [32,33,34].

The characteristics of the final SCG-based fertilizers differ greatly depending on several factors. For example, the worm species employed in vermicomposting have an impact on the product’s physicochemical properties as well as on the variety of microorganisms inhabiting it [22,35]. Vermicomposting with coffee waste has been tested by several researchers using various substrates. These commonly include manure, plant waste, and food waste. In each case, the optimal substrate/coffee waste ratios and composting time and conditions must be determined. For example, González-Moreno et al. [6] conducted a 60-day laboratory vermicomposting experiment with varying ratios of horse manure (HM), SCG, and CS, with HM as a reference. Adi and Noor [20] showed that the quality of the resulting vermicompost improved when using SCG compared to using only kitchen waste as a control after 49 days of vermicomposting. Hanc et al. [31] used SCG and straw pellets as a vermicomposting substrate, evaluating the differences between successive straw layers added during the composting process. It has been shown that co-composting with manure, food wastes, and plant residues generally improves the quality of (vermi)compost and reduces the time needed for (vermi)composting but occasionally results in notable losses of organic carbon [20,29,31].

The proportion of coffee waste and other organic matter in the (vermi)compost mixture is the most crucial factor. When using raw coffee waste or its high proportion in mixtures, overheating of the substrate, death of worms, and inhibition of microorganism growth can occur due to extremely high or low pH values, high caffeine content, and elevated ammonia levels [6,31,36,37]. In some studies, the best results were observed with a coffee waste content of 25 to 75% in the (vermi)compost mixture [6,30,31].

There are sufficient data showing that both composting methods are prospective tools for the utilization of coffee waste in the production of organic fertilizers suitable for soil fertility management. However, due to the high variability of the properties of (vermi)compost, depending on the raw materials used and how the composting process is arranged, the best production and application regime must be chosen for each specific case.

In our study, we used a ready-to-use commercial vermiproduct supplemented with granulated cow manure for feeding worms as a substrate. The chosen technology for the preparation of the vermicompost made it possible to speed up the composting process due to the maturity and stability of the initial substrate, and it also allowed for the comparison of the chemical and biological properties of the finished substrate obtained without the addition of SCG and the finished substrate obtained with its addition after 30 days of composting. An important factor that accelerated the composting process was the use of a pH-neutral substrate, which facilitated the neutralization of the potential acidity of the untreated compost raw materials and ensured a 100% survival rate for the earthworms. The objectives of this work were to (1) analyze the potential of vermicomposting and microbial composting in SCG decomposition and (2) determine the optimum rate of SCG for the process of composting based on a complex of biological, chemical, and microbiological indicators describing the reduction in potentially toxic compounds while maintaining potential phytostimulation properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The SCG were provided by Just Roast 13 LLC (Moscow, Russia). The main coffee varieties used in this production are Arabica and Robusta, with Arabica being predominant. SCG are spent coffee obtained after brewing in espresso machines, which are common in food service establishments. This coffee production waste is a secondary waste generated during consumption.

As co-composting material, we used commercially available “vermiground” with 25% vermicompost content, with the rest composed of Sphagnum peat and biochar (production of LLC “MFC Tochka Opory” (Moscow, Russia). This ground was selected after preliminary acute toxicity tests on Eisenia andrei.

2.2. Acute Toxicity Tests

As the first step in assessing the suitability of SCG for vermicomposting and further use as organic fertilizer, we performed a standard E. andrei acute toxicity test, following OECD Test Guideline 207. For this test, artificial soil composed of 70% quartz sand with a predominance of particles in the 50–200 µm range (more than 50%), 20% kaolin clay with a kaolin content of more than 30%, and 10% ground sphagnum peat (pH 5.5–6.0) was used. The pH of the artificial substrate was in the range of 6.0–6.5. Earthworms, Eisenia andrei, weighing approximately 300–400 mg, were used in the experiment. This earthworm species is used primarily for assessing the toxicity of pesticides and other agricultural chemicals [38].

A portion of artificial soil (500 g) was spread on a tray, then a sample of SCG was added at rates of 4, 8, and 12 g·kg−1 of artificial soil. These amounts of SCG were selected based on the optimal final substrate volume (as adding more SCG would exceed the vessel’s capacity). The minimum number of control points required to determine the degree of impact on worm survival and weight was three. Thus, using equal intervals, in reverse order (from 12 g·kg−1 and below), the ratios were 12, 8, and 4 g·kg−1. In addition, 100 mL of distilled water was added, and the mixture was allowed to soak in, mixed, and then transferred to a glass vessel.

One day before the test, earthworms were transferred from their habitat to a vessel with a substrate moistened with distilled water for acclimatization. On the first day of the experiment, earthworms were rinsed in distilled water and weighed then transferred to the surface of the test vessels at a rate of 10 individuals per vessel. In total, three replicates were taken for each of the listed rates of SCG. The vessels were covered with transparent film with ventilation holes. Illumination was maintained at 480–530 lux using fluorescent lamps in a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle. The temperature was maintained at 20 ± 2 °C throughout the experiment.

The vessels were exposed for 14 days. After exposition, earthworms were removed from the vessels, washed, and weighed, and the number of live and dead individuals was recorded.

2.3. Composting

We conducted composting experiments in two modes: vermicomposting and microbial composting. In both modes, we used “vermiground” as the compost base. SCG were added to “vermiground” at five ratios: 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%. Each component was moistened with water at a ratio of 3:1 and thoroughly mixed.

2.3.1. Vermicomposting

For composting, we used Worm Cafe® composters (Tumbleweed, Australia) with a capacity of 0.113 m3. Each composter was filled with 8 kg of composting mixtures and approximately 1000 individuals of earthworm Eisenia andrei. Due to its efficiency and rapid reproduction, Eisenia andrei is one of the most widely used earthworm species for vermicomposting [27], including in processing of SCG [22]. During the one month of vermicomposting, humidity in the room was maintained at 50–80%, and temperature was maintained at 20–24 °C. Weekly, the composters with worm culture were fed with granulated cow manure and pre-soaked in water at a ratio of 1:2, with a final mass of 1.5 kg per composter. Every 14 days, the composters were moistened with 1 L of water.

2.3.2. Microbial Composting

For microbial bioconversion, the same composters, humidity, and temperature regimes were used. Five-day-old cultures of the following microorganisms were added to the composting mixtures: Azotobacter chroococcum, Agrobacterium sp., Arthrobacter globiformis, Bacillus subtilis, Enterobacter sp., and Rhizobium sp. Bacteria used for composting were obtained from the Lomonosov Moscow State University collection of bacteria isolated from soil and conjugated substrates. Catalogue is available online at URL: https://depo.msu.ru/ assessed on 20 October 2025. Pure bacterial cultures were grown on liquid LB nutrient medium for 5 days. The biomass of each bacterial species was washed three times and resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline to a final count of 109 CFU/mL. The resulting suspensions were added to the corresponding compost mixtures at a ratio of 10 mL of suspension per 1 kg of compost. The added microbial suspensions were evenly distributed throughout the substrate. Thus, the final bacterial count of each species was 105 CFU·g−1. The contents of the composters containing the microorganisms were thoroughly mixed weekly. Final bacterial count was estimated by direct quantitative microscopy.

2.4. Chemical Analyses

Values of pH and RedOx potential were measured potentiometrically in water extracts of compost mixtures (1:5 w/v suspension) using a platinum electrode. Dry combustion method of Nelson and Sommers [39] was used for determining the organic carbon content. Lignin was determined by acid hydrolysis [40]. Content of Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd before and after both composting methods was determined by atomic absorption spectrometry in ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.8) and water extract. Content of both toxic elements—Pb and Cd—was below the detection limit. Levels of Cu and Zn were 1–25 ppm in ammonium acetate buffer (AAB) extract and 0.5–2 ppm in water extract. At these levels, the metals listed above could be considered microelements. Chemical analyses were performed in triplicate. The chemical data were statistically analyzed using Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and expressed as means ± standard errors. ANOVA was performed to analyze the significant differences between treatments at 5% level of significance.

2.5. Biological Analyses

Bacterial abundance was assessed using the R2A solid nutrient medium, a universal method for identifying culturable aerobic heterotrophic bacteria native to soils and other natural environments [41].

Mixed compost samples (150 g each) were collected using the envelope method 30 days after the start of composting and placed in sterile polypropylene containers. The samples were air-dried under aseptic conditions, ground in a mortar, and sieved through a 1 mm sieve. For inoculation on solid nutrient media, a 5 g sample of each compost sample was placed in a sterile 50 mL vial containing a phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) with a pH of 7.2–7.6 (Eco-Service, Murmansk, Russia). The vials were vortexed in a Multi Reax (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany) at 2000 rpm for 15 min to desorb cells from the surface of the mineral particles. After desorption, a series of tenfold dilutions from 1:101 to 1:109 were prepared. From each resulting suspension, cultures were then cultured in triplicate. The cultures were incubated at 28 °C for 14 days. After incubation, colonies on the plates were counted. Bacterial counts were calculated using the standard formula:

where N is the total number of colonies per plate, P is the dilution of the test sample, and V is the volume of suspension taken for inoculation (mL). The analysis was performed in triplicate.

X = N × P/V,

Microscopic analysis of the cellular morphology of the isolates was performed using a Primostar phase-contrast microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using the crushed drop method. Gram staining and physiological and biochemical tests were also performed, according to Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria [42], to identify the isolates.

The functional state of the microbial communities in the compost samples was assessed based on the consumption spectra of organic substrates obtained using the multisubstrate testing (MST) method [43]. A 0.7 g sample was placed in a sterile 50 mL vial, 30 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline was added, and the resulting suspension was vortexed in a Multi Reax (Heidolph Instruments, Schwabach, Germany) for 20 min at 2000 rpm to desorb bacterial cells from the mineral soil particles, which were then precipitated by centrifugation (2000 rpm, 2 min). A dehydrogenase activity indicator (triphenyltetrazolium chloride) was added to the microbial cells desorbed from the mineral carrier and then mixed, and 200 μL of the admixture was added to each well of a 96-well microplate containing a set of 47 test substrates in duplicate. The test substrates used included pentoses, hexoses, oligosaccharides, amino acids, polymers, nucleosides, organic acid salts, alcohols, amines, and amides. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for 72 h. After incubation, the optical density of the wells was measured at λ = 492 nm using a Sunrise photometer (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The data from photometric measurements of optical density values for all cells (all substrates) represent the spectrum of substrate consumption by the microbial community. On the basis of Shannon and Pielou indices, characteristics of functional diversity and metabolic state of the studied microbial community were calculated as described in [43]. The analysis was performed in two replicates.

Numbers of cultured bacteria and multisubstrate testing indices were compared by analysis of variance with Tukey test to assess differences between samples studied using IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Toxicity Tests

Evaluation of the acute toxicity assessment of SCG for E. andrei (Table 1) showed that at concentrations up to 12 g·kg−1, they did not affect worm weight or survival. Changes in worm weight across experimental conditions were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Mortality and biomass growth of earthworms as affected by different doses of SCG.

3.2. Chemical Properties

Prior to composting, all the original substrates had slightly acidic pH values between 5.6 and 6.2 (Figure 1). The pH increased as composting went on, with the vermicomposting mode experiencing a more noticeable increase (up to 7.4–7.7) than microbial composting (6.0–7.3). The ideal pH range for a mature compost is 6.0 to 7.5; the permissible range of pH for vermicompost according to national standards is 6.0–8.0 [44]. Increases in the proportion of SCG in the compost mixture did not significantly affect pH values during vermicomposting. However, a rise in the amount of SCG caused slight acidification by 0.6–1.3 pH units. The most likely explanation is that organic acid-secreting bacteria are actively pulled. According to Hayat et al. [45], pH values between 6 and 7 units are ideal for the bacteria promoting plant growth.

Figure 1.

pH values in compost mixtures at different proportions of SGC and modes of composting (mean and standard error).

Good aeration was maintained throughout the composting process, creating aerobic conditions for the decomposition of organic matter. RedOx potential levels achieved 142–166 mV for microbial composting (Figure 2). However, for vermicomposting, they were 1.7 times lower (73–113 mV). SCG addition had no noticeable effect on RedOx potential at any concentration.

Figure 2.

RedOx potential in compost mixtures at different proportions of SCG and modes of composting, mV (mean and standard error).

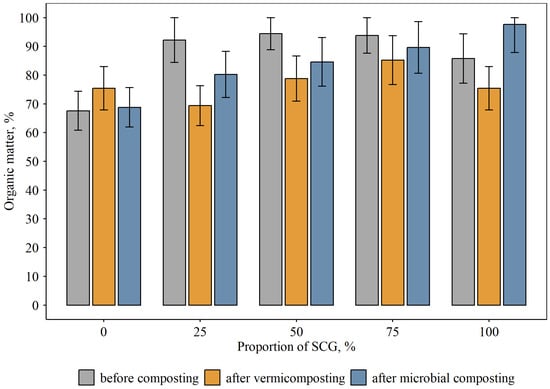

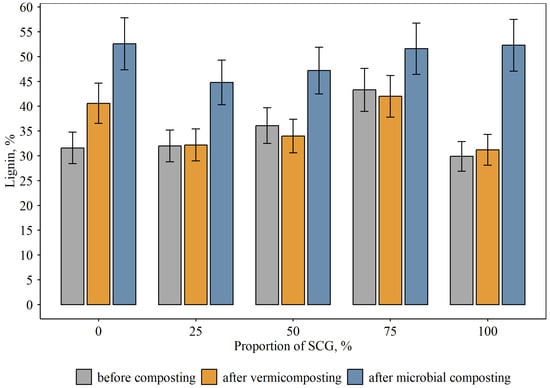

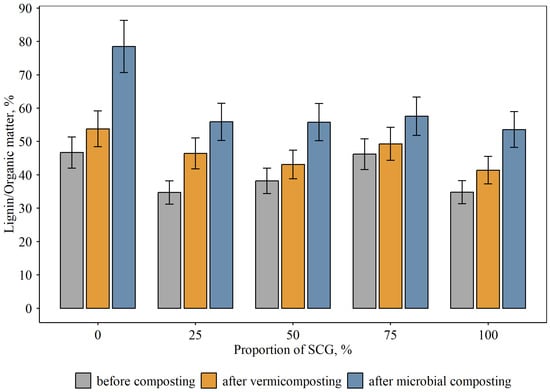

The initial control substrate was relatively high in organic matter, 68%, of which 47% was represented by lignin (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). In the substrate–SCG mixtures, the OM content increased up to 86–94%, and the amount of lignin slightly decreased. The lignin content in the initial control substrate without added SCG was also high, at 32%. It increased slightly during vermicomposting, apparently due to the decomposition of more readily accessible organic matter. In the compost with added microorganisms, this increase reached 56% of the OM content. Apparently, the native microorganisms in the compost, along with the added complex, quickly consumed the readily accessible organic matter, but more stable organic matter (lignin) was virtually not degraded. A different pattern of consumption of both readily accessible and less readily accessible organic matter was observed for both vermicomposting and the compost with added microorganisms when SCG were added. In this case, there was a slight increase in lignin content for the experimental variants with added waste. Consequently, the added SCG facilitated the rapid processing of both readily degradable organic matter and the recalcitrant lignin. Furthermore, lignin is considered a precursor of humic substances. This increases the value of the resulting biofertilizer.

Figure 3.

Content of organic matter (OM) in compost mixtures at different proportions of SCG and modes of composting, % dry matter (mean and standard error).

Figure 4.

Content of lignin in compost mixtures at different proportions of SCG and modes of composting, % dry matter (mean and standard error).

Figure 5.

Proportion of lignin in OM in compost mixtures at different proportions of SCG and modes of composting, % dry matter (mean and standard error).

3.3. Bacterial Abundance and Functional Biodiversity

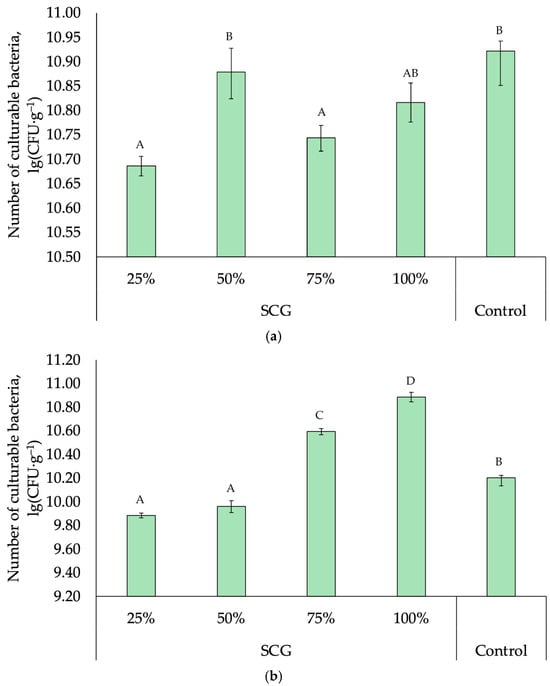

The total number of culturable bacteria in the compost samples, regardless of composting conditions, was 1011 CFU·g−1, corresponding to a high microbial content of the substrate (Figure 6). In both composting modes in samples with a low SCG content (25%), the number of culturable bacteria decreased by an order of magnitude, up to 1010 CFU·g−1.

Figure 6.

Number of culturable bacteria in the studied composts: (a) vermicomposts; (b) microbial composts. Error bars indicate the confidence interval for the mean with a significance level of p = 0.05. Superscript letters indicate Tukey test significant differences (p < 0.05).

In SCG-containing vermicomposts, the number of culturable bacteria was comparable to the control composting substrate without SCG, indicating the neutral effect of coffee production waste: neither suppression nor stimulation of the vermicompost microbiome occurred (Figure 6a).

In composts where the main agent of organic matter transformation was an artificially created and introduced bacterial consortium, a tendency toward an increase in the number of culturable bacteria was observed in SCG-containing samples (Figure 6b). The number of culturable bacteria was 3–4 times higher in SCG-containing compost compared to the control level. In addition, we recorded an increase in the number of culturable bacteria, correlated with the increase in the proportion of SCG in the compost: the difference in the numbers between the mixtures containing 25 and 100% of SCG was 10-fold.

The taxonomic composition of the aerobic heterotrophic bacteria in the studied composts is presented in Table 2. In all samples studied, microorganisms with the potential to plant growth promotion ability were detected. Among the bacteria cultured on R2A medium, representatives of the genus Bacillus dominated in all samples. In most samples, bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas, also known for their ability to stimulate plant growth, were found among the dominant bacteria. In addition, bacteria of the genera Micrococcus (in vermicompost with 25% SCG), Chromobacterium (in vermicompost with 50% SCG and compost with 75% SCG), Arthrobacter (in vermicompost and compost without added SCG, vermicompost with 75% SCG, and compost with 100% SCG), Flavobacterium (in vermicompost with 50% SCG and compost with 25% SCG), and Streptomyces (in compost without added SCG) were identified as dominants and subdominants.

Table 2.

Taxonomic composition of cultivated aerobic heterotrophic bacterial communities of the compost mixtures with different proportions of SGC and modes of composting.

In vermicompost with 100% SCG, bacteria of the genus Xanthomonas were found among the dominant bacteria, many representatives of which have phytopathogenic properties [46], while others can produce gibberellins that stimulate plant growth [47].

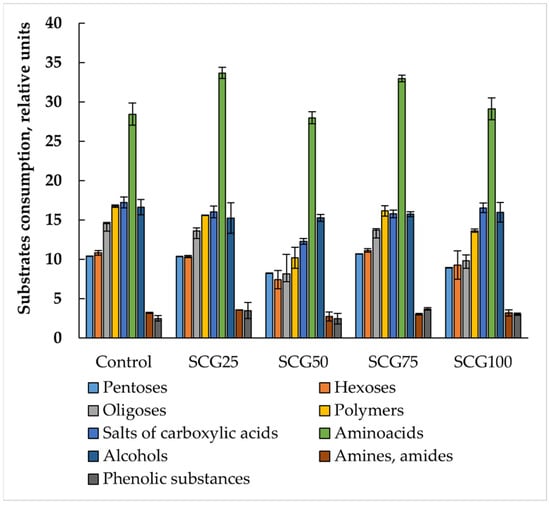

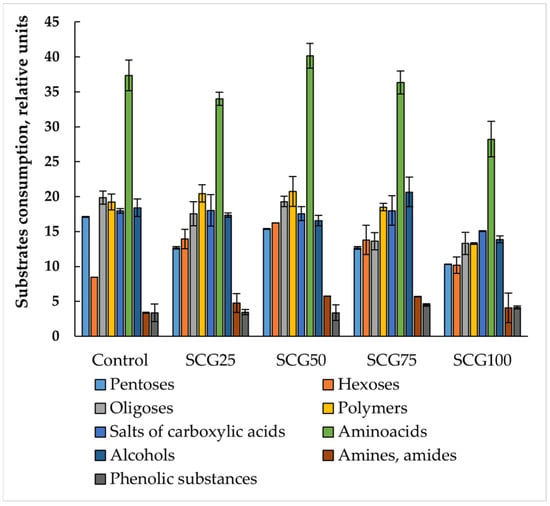

The microbial communities of all studied samples were characterized by high potential metabolic activity and functional diversity (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Consumption of substrates of different nominal groups by microbial communities of vermicomposts. Error bars represent standard deviation. Data on significance differences are presented in Table S1.

Figure 8.

Consumption of substrates of different nominal groups by microbial communities of microbial composts. Error bars represent standard deviation. Data on significant differences are presented in Table S1.

The number of consumed substrates ranged from 43 to 46, meaning that consumption of almost all studied substrates occurred, except for urea. Some communities did not consume methionine or tryptophan. In the vermicompost treatments with 50% and 75% SCG, as well as in the microbial compost, there was no consumption of soluble starch, which may be important for the microbial community’s capacity to decompose plant residues.

The microbial communities showed no differences in Shannon or Pielou indices. The Shannon index ranged from 5.24 to 5.33, while the Pielou index ranged from 0.95 to 0.97 (Table 3), indicating the high functional diversity and uniformity of the studied microbial communities. Some differences in the average optical density of the plate cell were, however, observed. The lowest values of this index were found for the microbial communities of the vermicomposts with the addition of 50% and 100% SCG and for the microbial compost with 100% SCG, for which this index was equal to 1.97, 2.28, and 2.31, respectively. The highest values (from 2.96 to 3.24) were observed for the composts with 25%, 50%, and 75% grounds and for the compost without the addition of SCG. In the remaining studied communities, this indicator was about 2.5.

Table 3.

Taxonomic composition of cultivated aerobic heterotrophic bacterial communities of the compost mixtures with different proportions of SGC and modes of composting. Error represents standard deviation. Treatments with the same superscript letter in a column are not statistically different at p < 0.05.

Minor differences in the consumption of substrates of different nominal groups were also observed. These differences were the smallest for amino acids, alcohols, and organic acid salts, with the coefficient of variation in the consumption of these groups ranging from 9 to 13%. For the remaining substrate groups, the coefficient of variation was approximately 20%. It should be noted that the microbial communities with the lowest average cell optical density values demonstrated a significant reduction in the consumption of hexoses, oligosaccharides, and polymers. The reduced ability to consume oligosaccharides and polymers indicates a reduced ability of the studied microbial communities to decompose plant residues. By contrast, composts with 25% and 50% SCG showed the highest polymer and oligosaccharide consumption.

4. Discussion

4.1. Vermicomposting Potential for Coffee Waste Conversion into Biofertilizer

The mortality and growth of earthworm species used for vermicomposting toxic organic wastes can be used to assess the efficiency of the process. In our study, no acute toxicity of SCG to E. andrei was revealed. The presence of SCG at concentrations up to 12 g/kg had no negative effect on the survival or weight of earthworms. On the one hand, we observed that the presence of coffee grounds in the substrate promoted favorable conditions for the life and reproduction of worms, as evidenced by the successful vermicomposting process. Similar results were reported by Adi and Noor [20], who used Lumbricus rubellus and noted a significant increase in the number and biomass of worms in SCG-based vermicompost, attributing this to improved substrate texture, water retention capacity, and aeration, as well as a pest repellent effect and pH stabilization. We hypothesize that similar mechanisms could explain the results obtained in our experiments.

On the other hand, a high mortality of E. andrei was observed in raw SCG (76–84%), but the addition of cardboard as an alkalizing buffer significantly increased survival by up to 62–81% [21]. In our case, using pre-prepared vermicompost with a neutral pH (7.6) as a compost base allowed for the neutralization of the potential acidity of the raw SCG and ensured the 100% survival of the earthworms, which confirms the importance of pH adjustment for successful vermicomposting.

However, despite the lack of toxicity to earthworms and successful vermicomposting, there are still some ecotoxicological concerns. Our findings are consistent with those of other authors highlighting the need for the pretreatment or composting of raw SCG to reduce their phytotoxicity before application to agrocenoses [4,48].

The results of biotesting, which showed an initially high hazard class (Class II) for the raw coffee grounds and its reduction to moderately hazardous (Class III) after vermicomposting, correlate with the data on the phytotoxic effect described in the work of Ciesielczuk et al. [48]. In their study, it was also noted that the inhibition of seedling growth, especially of watercress (Lepidium sativum L.), was most pronounced at high concentrations of SCG (10%) and was associated with high electrical conductivity and, possibly, the presence of phytotoxic compounds such as caffeine and polyphenols [48]. In our case, the vermicomposting process, as well as microbial composting, effectively neutralized this negative effect, transferring the material to the category of moderately hazardous and even stimulating plant growth at certain concentrations (25–50% SCG) [49]. This confirms that composting is a key step in converting SCG from waste into an organic fertilizer.

4.2. Chemical Parameters of Coffee Waste Conversion into Biofertilizer

Our data showed that aqueous extracts from SCG-containing composts had pH values ranging from slightly acidic to neutral (5.6–7.7), which is favorable for most agricultural crops and soil microorganisms [45]. This is consistent with the results of Ciesielczuk et al. [48], who also observed variations in the pH of SCG-based fertilizers from 5.61 to 9.15, depending on the additives (ash, magnesium sulfate). Our results indicate that the composting process stabilizes the pH, preventing the risk of excessive acidification or alkalization of the soil when applying the resulting fertilizers.

Microbial composting maintained RedOx potential at a constant level, while vermicomposting decreased Eh values. This could reflect the different pathways for organic matter transformation: the anaerobic/facultative-anaerobic nature of vermicomposting versus the more aerobic conditions of microbial composting. Both processes, however, promote the detoxification and stabilization of organic matter.

The high OM content (up to 98%) in our composts, especially after microbial treatment, and the ability of SCG to promote the degradation of recalcitrant fractions, such as lignin, highlight their value as a source of stable organic matter and a precursor to humic substances. This directly enhances the agronomic value of the resulting biofertilizer, as also noted in the study by Ciesielczuk et al. [48].

4.3. Biological Parameters of Coffee Waste Conversion into Biofertilizer

The numbers of culturable bacteria observed in our composts at the level of 109–1011 CFU·g−1 correspond to the levels found in previous similar studies [5,29,35,50,51]. We found a high biological activity of the compost containing SCG compared to the non-coffee composts [17]. We found that the composts combined with SCG are characterized by fast decomposition and depth of processing, but at high levels of SCG, an inhibition of biotransformation processes is observed, which is likely due to the content of toxic alkaloids and oils in coffee by-products [17,52,53]. Despite the small differences identified in this study, all studied microbial communities were characterized by high potential metabolic activity and functional diversity due to the high microbial abundance in the samples, as determined by culture-based assay.

The taxonomic diversity of the bacteria found in the composts’ microbiomes, represented by Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and actinobacteria, corresponds well with previously published data on the high proportion of plant-growth-promoting bacteria in different methods of coffee waste composting [7,35,51,52,54,55,56]. The same genera are common for coffee pulp, coffee rhizosphere, and coffee beans’ surface and interior [33,57,58,59]. Many bacteria of the Bacillus genus can stimulate plant growth [17,19,60]. Representatives of the Pseudomonas, Micrococcus, Chromobacterium, Arthrobacter, Flavobacterium, and Streptomyces genera have also been shown to have plant-growth-promoting properties [47,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

Due to the detected high potential metabolic activity and taxonomic diversity of both obtained composts’ microbial communities, it could be suggested that after addition into soil as fertilizer, SGC could contribute to phytostimulating processes both by activating the transformation of various carbon compounds (including those introduced with the compost) and by producing various enzymes, phytohormones, and other metabolites into the microbiome [10,17,19].

4.4. Limitations of the Study

This study confirms the potential of 30-day composting and vermicomposting as methods for the utilization of SCG to produce chemically safe and microbiologically highly active composts. We also conducted phyto- and biotesting of the resulting composts, which demonstrated the effectiveness of vermicomposting in reducing the hazard class of SCG while maintaining low levels of mobile heavy metals (Cu, Zn, and Pb) [49]. However, neither the cited nor the present studies can assess the potential of using the produced SCG composts to stimulate crop growth, taking into account their quantitative and qualitative indicators, or their long-term impact on soil fertility, or their ability to ensure microbial biodiversity in the soil, reduce heavy metal toxicity in the soil, or fix soil organic matter. Therefore, pot and micro-field experiments with the two types of produced composts are needed to better understand the potential of composted coffee products, such as soil amendment, nutrient supplier, and biostimulator on agricultural soils, to exert beneficial effects on soil quality and crop health.

5. Conclusions

The results of the present study showed that the potential phytotoxicity of SCG waste products can be effectively reduced by microbial composting and vermicomposting. Chemically safe and microbiologically highly active composts can be produced with an initial SCG content in the range of 25–50% of the initial organic substrate content. The high earthworm survival and the high taxonomic and functional diversity of the microflora in the end products suggest that potentially toxic SCG compounds are detoxified or immobilized within the organic matter after both vermicomposting and microbial composting. Our results are consistent with those obtained by other authors who have used vermicomposting of coffee wastes with such organic substrates as straw, horse manure, and food waste.

The composting process stabilizes the pH, preventing the risk of excessive acidification or alkalization of the soil when applied as fertilizer. The high OM content in the composts and the ability of SCG to promote the degradation of lignin highlight their value as a biofertilizer, a source of stable organic matter, and a precursor of humic substances.

An important result of vermicomposting and microbiological composting was the effective neutralization of the negative effects of phytotoxic compounds in a short period of time, which also eliminated the pretreatment period used by many authors. This was achieved by using an initial substrate with a neutral pH (7.6), which neutralized the potential acidity of raw SCG and ensured the 100% survival of earthworms during vermicomposting. Microbiological studies also confirmed that all the microbial communities studied were characterized by high metabolic activity potential and functional diversity, and the number of cultured bacteria correlated with the proportion of SCG in microbial composting.

At an SCG content higher than 50% in the compost, chemical parameters (RedOx potential, pH, and lignin content) that exceed established standards are more likely to be found. Both composting methods using 100% coffee waste also revealed a slight decrease in the potential metabolic activity of the microbial communities, including the reduced consumption of polymers and oligosaccharides, which may indicate a lower capacity to decompose plant residues. Given the high biological activity of both the resulting composts, as well as the presence of PGPB, their positive effect on plant growth and development can be expected when applied to the soil.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122823/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.K. and V.R.; methodology, V.R., E.S., O.Y., A.B. and V.C.; formal analysis, E.S., A.B. and V.C.; investigation, E.S., A.B., V.C., H.N., B.N.-M. and T.W.; resources, P.K. and V.R.; data curation, E.S., A.B. and V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S., V.C. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, E.S., V.C., A.B., O.Y., V.R., H.N., B.N.-M., T.W. and P.K.; visualization, E.S., V.C. and A.B.; supervision, P.K., V.R. and O.Y.; project administration and funding acquisition, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, project «Innovative fertilizers based on coffee by-products», agreement № 075-15-2024-662.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Rostislav Streletskii, Director of the Limited Liability Company “Center for Pesticide Laboratory Research” (LLC “Pest-Lab”), for his assistance in conducting the ecotoxicological study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCG | Spent coffee grounds |

| PGPB | Plant-growth-promoting bacteria |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Voora, V.; Bermudez, S.; Larrea, C. Global Market Report: Coffee; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378140395_Global_Market_Report_Coffee (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- International Coffee Organization. Historical Data on the Global Coffee Trade; International Coffee Organization: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, E.; Cruzat, V.; Singh, I.; Rose’Meyer, R.B.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. The potential of spent coffee grounds in functional food development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Ballesteros, L.F.; Martins, S.; Teixeira, J.A. Extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds from spent coffee grounds. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 83, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmar, A.K.; Albedwawi, S.T.; Alsalami, A.K.; Alshemeili, A.R.; Abu-Elsaoud, A.M.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Raish, S.M.A. The Effect of Recycled Spent Coffee Grounds Fertilizer, Vermicompost, and Chemical Fertilizers on the Growth and Soil Quality of Red Radish (Raphanus sativus) in the United Arab Emirates: A Sustainability Perspective. Foods 2024, 13, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moreno, M.A.; Gracianteparaluceta, B.G.; Sádaba, S.M.; Urdin, J.Z.; Domínguez, E.R.; Ezcurdia, M.A.P.; Meneses, A.S. Feasibility of vermicomposting of spent coffee grounds and silverskin from coffee industries: A laboratory study. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, A.S.C.; Oliveira, D.M.; Walling, E.; Babin, A.; Hersant, G.; Vaneeckhaute, C.; Dumont, M.J.; Rodrigue, D. Spent coffee grounds characterization and reuse in composting and soil amendment. Waste 2022, 1, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezerská, L.; Prokes, R.; Sassmanova, V.; Gelnar, D. The pelletization and torrefaction of coffee grounds, garden chaff and rapeseed straw. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Hernandez, J.C.; Domínguez, J. Vermicompost derived from spent coffee grounds: Assessing the potential for enzymatic bioremediation. In Handbook of Coffee Processing by-Products; Galanakis, C., Ed.; Academic Press, Elsevier: London, UK, 2017; pp. 369–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Z.; Yang, R. Spent Coffee Ground and Its Derivatives as Soil Amendments—Impact on Soil Health and Plant Production. Agronomy 2025, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.; Cocco, S.; Casucci, C.; Cardelli, V.; Corti, G. Coffee by-products derived resources. A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, F.G.; Floyd, D.; Mundaca, E.A.; Crisol-Martínez, E. Spent coffee grounds applied as a top-dressing or incorporated into the soil can improve plant growth while reducing slug herbivory. Agriculture 2023, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzung, N.A. Evaluation of coffee husk compost for improving soil fertility and sustainable coffee production in rural Central Highland of Vietnam. Resour. Environ. 2013, 3, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Amalia, N.; Widialip, N.F.; Safira, N.; Citrasari, N. The potential of coffee waste composting technology using microbial activators to reduce solid waste in the coffee industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 802, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmawati, F.N.; Pramudya, Y.; Pamungkas, S.S.T.; Rozaki, Z.; Irna, A.; Sukarji, S.; Rahmat, A.; Hanum, F.F. Quality analysis of coffee waste compost with the addition of cassava tapai local microorganism (LMO) bioactivator. Appl. Res. Sci. Technol. 2023, 3, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseini, M.; Cocco, S.; Casucci, C.; Cardelli, V.; Ruello, M.L.; Serrani, D.; Corti, G. Producing agri-food derived composts from coffee husk as primary feedstock at different temperature conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrijević, S.; Milić, M.; Buntić, A.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.; Filipović, V.; Popović, V.; Salamon, I. Spent coffee grounds, plant growth promoting bacteria, and medicinal plant waste: The biofertilizing effect of high-value compost. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, H.; Ozdemir, N.; Ates, A.; Koklu, R.; Ozturk Erdem, S.; Ozdemir, S. Circular Utilization of Coffee Grounds as a Bio-Nutrient Through Microbial Transformation for Leafy Vegetables. Life 2024, 14, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santhanarajan, A.E.; Han, Y.H.; Koh, S.C. The efficacy of functional composts manufactured using spent coffee ground, rice bran, biochar, and functional microorganisms. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, A.J.; Noor, Z.M. Waste recycling: Utilization of coffee grounds and kitchen waste in vermicomposting. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Price, G.W. Evaluation of three composting systems for the management of spent coffee grounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7966–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zergaw, Y.; Kebede, T.; Berhe, D.T. Direct application of coffee pulp vermicompost produced from epigeic earthworms and its residual effect on vegetative and reproductive growth of hot pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 7366925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Singh, P.; Araujo, A.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Sulaiman, O. Management of urban solid waste: Vermicomposting a sustainable option. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.A.; Arancon, N.Q.; Sherman, R.L. Vermiculture Technology: Earthworms, Organic Wastes, and Environmental Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, M.D.; Ay, A.; Ullah, I.; Demirkaya, S.; Kizikaya, R.; Mihoub, A.; Zia, A.; Jamal, A.; Ghfar, A.A.; Serio, A.D.; et al. Vermicompost rate effects on soil fertility and morpho-physio-biochemical traits of lettuce. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, B.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M.; Sekaran, G. Changes in earthworm gut associated enzymes and microbial diversity on the treatment of fermented tannery waste using epigeic earthworm Eudrilus eugeniae. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 74, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisa, D.; Jamal, A. Vermicompost in agricultural production: Mechanisms, importance, and applications. Multidiscip. Rev. 2025, 8, 2025325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, W.A.; Nogueira, F.N.; Devens, D.C. Temperature and pH control in composting of coffee and agricultural wastes. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemekite, F.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Franke-Whittle, I.H.; Praehauser, B.; Insam, H.; Assefa, F. Coffee husk composting: An investigation of the process using molecular and non-molecular tools. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadi, D.; Daba, G.; Beyene, A.; Luis, P.; Van der Bruggen, B. Composting and co-composting of coffee husk and pulp with source-separated municipal solid waste: A breakthrough in valorization of coffee waste. Int. J. Recycl. Org. Waste Agric. 2019, 8, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanc, A.; Hřebečková, T.; Grasserova, A.; Cajthaml, T. Conversion of spent coffee grounds into vermicompost. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela-Cano, M.; Gómez-Brandón, M.; Pesciaroli, C.; Insam, H.; González-López, J. Study of total bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea in response to irrigation with sewage sludge compost tea in agricultural soil. Compos. Sci. Util. 2018, 26, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urgiles-Gómez, N.; Avila-Salem, M.E.; Loján, P.; Encalada, M.; Hurtado, L.; Araujo, S.; Collahuazo, Y.; Guachanamá, J.; Poma, N.; Granda, K.; et al. Plant growth-promoting microorganisms in coffee production: From isolation to field application. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Burillo, S.; Cervera-Mata, A.; Arteaga, A.F.; Pastoriza, S. Why should we be concerned with the use of spent coffee grounds as an organic amendment of soils? A narrative review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael, K.; Velmourougane, K. Chemical and microbiological changes during vermicomposting of coffee pulp using exotic (Eudrilus eugeniae) and native earthworm (Perionyx ceylanesis) species. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Marques dos Santos Cordovil, C.S. Espresso coffee residues as a nitrogen amendment for small-scale vegetable production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera-Mata, A.; Navarro-Alarcón, M.; Rufián-Henares, J.A.; Pastoriza, S.; Montilla-Gómez, J.; Delgado, G. Phytotoxicity and chelating capacity of spent coffee grounds: Two contrasting faces in its use as soil organic amendment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cang, T.; Zhao, X.; Yu, R.; Chen, L.; Wu, C.; Wang, Q. Comparative acute toxicity of twenty-four insecticides to earthworm, Eisenia fetida. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 79, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Method of Soil Analysis, Part 2; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 539–579. [Google Scholar]

- Feofilova, E.P.; Mysyakina, I.S. Lignin: Chemical structure, biodegradation, and practical application (a review). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2016, 52, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reasoner, D.J. Microbiology of potable water and groundwater. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1983, 55, 891–895. [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, F. Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheptsov, V.S.; Vorobyova, E.A.; Manucharova, N.A.; Gorlenko, M.V.; Pavlov, A.K.; Vdovina, M.A.; Lomasov, V.N.; Bulat, S.A. 100 kGy gamma-affected microbial communities within the ancient Arctic permafrost under simulated Martian conditions. Extremophiles 2017, 21, 1057–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOST R 56004—2014; National Standard of the Russian Federation. Organic Fertilizers. Vermicomposts. Technical Specifications. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2020. Available online: https://internet-law.ru/gosts/gost/57362/ (accessed on 31 October 2025). (In Russian)

- Hayat, R.; Amara, U.; Khalid, R.; Ali, S. Soil beneficial bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion: A review. Ann. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, S.; Potnis, N.; Newberry, E.A.; Liyanapathiranage, P.; Iruegas-Bocardo, F.; White, F.F.; Goss, E.M.; Jones, J.B. Xanthomonas diversity, virulence and plant–pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif-Silini, H.; Silini, A.; Bouket, A.C.; Alenezi, F.N.; Luptakova, L.; Bouremani, N.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Oszako, T.; Belbahri, L. Tailoring next generation plant growth promoting microorganisms as versatile tools beyond soil desalinization: A road map towards field application. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielczuk, T.; Rosik-Dulewska, C.; Poluszyńska, J.; Miłek, D.; Szewczyk, A.; Sławińska, I. Acute Toxicity of Experimental Fertilizers Made of Spent Coffee Grounds. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 2157–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortova, S.M.; Voronina, L.P.; Smolskiy, E.Y.; Romanenkov, V.A.; Krasilnikov, P.V. Ecotoxicological assessment of coffee waste as a component of organic fertilizers. Eurasian Soil. Sci. 2025, 58, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martin Ruiz, M.; Reiser, M.; Kranert, M. Composting and methane emissions of coffee by-products. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, A.; Belguith, K.; Jedidi, N.; Cherif, A.; Cherif, M.; Boudabous, A. Microbial characterization during composting of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 80, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.C.; Inoue, Y.; Yasuta, T.; Yoshida, S.; Katayama, A. Chemical and microbial properties of various compost products. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2003, 49, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeć, M.; Baran, A.; Mierzwa-Hersztek, M.; Gondek, K.; Chmiel, M.J. Effect of the addition of biochar and coffee grounds on the biological properties and ecotoxicity of composts. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papale, M.; Romano, I.; Finore, I.; Lo Giudice, A.; Piccolo, A.; Cangemi, S.; Di Meo, V.; Nicolaus, B.; Poli, A. Prokaryotic diversity of the composting thermophilic phase: The case of ground coffee compost. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, A.; Son, Y.H.; Joo, S.H. Changes in physical, chemical, and biological traits during composting of spent coffee grounds. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2020, 39, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, S.A.; Yoo, J.; Kim, E.J.; Chang, J.S.; Park, Y.I.; Koh, S.C. Development of functional composts using spent coffee grounds, poultry manure and biochar through microbial bioaugmentation. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2017, 52, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Varela, P.A.; Duque-Dussán, E. Functional Characterization of Native Microorganisms from the Pulp of Coffea arabica L. Var. Castillo and Cenicafé 1 for Postharvest Applications and Compost Enhancement. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.F.; Schwan, R.F.; Dias, Ë.S.; Wheals, A.E. Microbial diversity during maturation and natural processing of coffee cherries of Coffea arabica in Brazil. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 60, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, B.; Marraccini, P.; Maeght, J.L.; Vaast, P.; Lebrun, M.; Duponnois, R. Coffee microbiota and its potential use in sustainable crop management. A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 607935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.V.B.; Bonifacio, A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Araujo, F.F.; Stamford, N.P. Beneficial microorganisms: Current challenge to increase crop performance. In Bioformulations for Sustainable Agriculture; Arora, N., Mehnaz, S., Balestrini, R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastager, S.G.; Deepa, C.K.; Pandey, A. Isolation and characterization of novel plant growth promoting Micrococcus sp. NII-0909 and its interaction with cowpea. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.L.; Payasi, D.K. Plant growth-promoting and bio-control activity of Micrococcus luteus strain AKAD 3-5 isolated from the soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) rhizosphere. Open Microbiol. J. 2021, 15, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Dhyani, R.; Ahmad, E.; Maurya, P.K.; Yadav, M.; Yadav, R.C.; Yadav, V.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Sharma, M.P.; Ramesh, A.; et al. Characterization and low-cost preservation of Chromobacterium violaceum strain TRFM-24 isolated from Tripura state, India. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, O.G.; Kim, J.B.; Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Sul, W.J.; Hwang, J.Y.; Lee, J.H. Flavobacterium sp. strain GJW24 ameliorates drought resistance in Arabidopsis and Brassica. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1257137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agunbiade, V.F.; Fadiji, A.E.; Agbodjato, N.A.; Babalola, O.O. Isolation and characterization of plant-growth-promoting, drought-tolerant rhizobacteria for improved maize productivity. Plants 2024, 13, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, S.W. The plant-associated Flavobacterium: A hidden helper for improving plant health. Plant Pathol. J. 2024, 40, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).