Abstract

Agroecological weed management is important for agriculture’s shift toward sustainability. This study evaluated stale seedbed and intercropping combinations for weed management in vetch (Vicia sativa L.) cultivation in Greece during the 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 growing seasons. A Randomized Complete Block Design was established using a split-plot arrangement. Two weed management practices served as the main plots: untreated control (CON) and stale seedbed (SSB). Four intercropping methods formed the subplots: vetch monocropping (VM), vetch–barley mixed intercropping (VBMXIC), vetch–barley row intercropping (VBROWIC), and vetch–barley relay intercropping (VBRELIC). The interaction between weed management and intercropping influenced weed NDVI (p < 0.001), weed biomass, and vetch NDVI (p < 0.01). Weed NDVI and biomass were highest for CON × VM, CON × VBMXIC, CON × VBROWIC, and CON × VBRELIC interactions. Vetch NDVI was highest (0.71) for SSB × VM. Grain yield was affected by growing season (p < 0.05), weed management (p < 0.001), and intercropping (p < 0.001). SSB resulted in a 42% higher yield compared to CON. VBRELIC and increased yields by 7%, 22%, and 29% compared to VBROWIC, VM, and VBMXIC, respectively. Further research is needed to evaluate additional agroecological weed management practices in more crops and environments.

1. Introduction

Herbicides have been the most widely adopted tool for weed management since the 1960s because they are effective for weed control, cost-effective, cause less soil erosion, and have a lower carbon footprint compared to mechanical weed control [1]. However, agriculture’s overreliance on herbicides has created environmental, human health, and herbicide-resistance concerns, while the evolution and rapid spread of herbicide-resistant weeds globally have hindered their efficacy during a period when no new herbicide mode of action has been developed since the 1980s [2].

As the era of herbicide dominance in weed management fades, alternative weed management practices are expected to play a pivotal role [3]. Agroecological weed management should be considered a fair representation of the shift in agriculture toward more sustainable and holistic practices [4]. Agroecological practices can contribute to weed suppression while maintaining high yields comparable to those achieved through conventional production systems [5]. In addition, integrating agroecology into integrated weed management (IWM) systems has significant potential to reduce herbicide inputs; this benefits environmental health and is also essential for maintaining the efficacy of current herbicide modes of action over time [6].

False and stale seedbeds are among the most promising cultural practices that align with the concept of agroecology and can facilitate effective weed control in agricultural fields [7]. To implement both practices, the field is left undisturbed after seedbed preparation, and sowing of the crop is delayed for several weeks to allow weeds to emerge. Weed emergence is stimulated by rainfall during winter and irrigation during the spring–summer growing season [8,9]. The emerged weeds can be controlled before sowing the crop with shallow tillage or with the application of a non-selective herbicide in stale seedbeds [10]. To avoid using the non-selective post-emergence herbicide glyphosate (HRAC/WSSA Group 9) in stale seedbeds, pelargonic acid can be used instead [11]. Pelargonic acid (CH3(CH2)7CO2H, n-nonanoic acid) is a saturated, nine-carbon fatty acid (C9:0) that naturally occurs as esters in the essential oil of Pelargonium spp. plants [12]. It is applied as a contact burndown herbicide which attacks cell membranes and causes cell leakage and the breakdown of membrane acyl lipids.

In annual crops, because it is a non-selective bioherbicide, pelargonic acid can be applied to control weeds only in stale seedbeds before sowing the crop [9,11]. It is also possible to perform direct spraying in the inter-row areas of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), as glyphosate is used for this purpose [13]. In perennial crops, this natural herbicide can control weeds in the inter-row and intra-row areas of orchards, representing the definition of a “glyphosate alternative”, but with efficacy that depends on multiple factors [14,15]. Other researchers have also evaluated the selectivity of pelargonic acid on onions (Allium cepa L.) and weed control efficacy in field trials where climate conditions exerted a significant influence on its performance [16]. Another use of pelargonic acid in agriculture is the desiccation of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) haulms [17]. In any case, as a natural bioherbicide, its applications should be further evaluated as a component of agroecological weed management strategies.

Another sustainable agroecological practice to suppress weeds is the inclusion of intercropping in IWM systems [2]. Intercropping means the simultaneous cultivation of at least two crops with different functional traits for a period of time that aims to optimize resource use and uptake [18]. There are four types of intercropping according to the methodology by which this agroecological cultural practice is implemented, they are as follows: mixed intercropping, row intercropping, strip intercropping, and relay intercropping [19]. Mixed intercropping includes two or more crop species in the same row; row intercropping includes sowing two or more crops in alternate rows; strip intercropping refers to the cultivation of two or more crops in alternate strips of uniform width; while relay intercropping means that the companion crop and the major crop are not sown at the same time [20]. Regardless of how it is applied, when species from different functional groups are grown as an intercrop, intercropping leads to spatial diversification of resource use [21]. This can theoretically maximize crop biomass production and improve crop competition against weeds, which are more deprived of resources compared to when a monocrop is present in the field [22].

A wide range of such cultural practices are included in the toolbox of “ONE GREEN”, a research project currently underway in Greece and funded by the European Union under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0”, which focuses on developing and implementing agroecological practices. Following a multi-actor and participatory approach, the project aims to evaluate various agroecological weed and crop management practices in six Living Labs (LLs) located in different agricultural areas throughout the country.

The objective of this work was to assess the integrated effects of stale seedbed manipulation and different intercropping methods on weed growth and the grain yield of vetch (Vicia sativa L.) in Central Greece, where vetch is one of the most important crops for animal nutrition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

A field trial was conducted during the 2023–2024 and 2024–2025 growing seasons in Thiva, Central Greece (38°19′51.7″ north latitude (N), 23°23′58.9″ east longitude (E)). Soil type was sandy clay loam (SCL) with the following particle size distribution: 47.8% sand, 30.3% clay, and 21.9% silt; a pH value of 7.34; and an organic matter content of 1.28%. The average air temperature at the experimental site over the past 30 years (1979–2024) was 16.5 °C, and the mean annual precipitation height from 1979 to 2024 was 442.0 mm. As for the climate conditions which were observed in the experimental field during the trial period (2023–2024 and 2024–2025), total precipitation was much higher in the second growing season (491.4 mm) than in the first (321.0 mm). During the 2023–2024 growing season, the lowest temperature was 8.7 °C in February 2024, while in the 2024–2025 growing season, the coldest month was again February, with an average air temperature of 7.1 °C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average, maximum, and minimum temperature (°C) and precipitation (mm) observed in the experimental area for each month during the two growing seasons (2023–2024 and 2024–2025).

Vetch was studied as the main crop. The vetch cultivar “Tempi” (National Agricultural Research Foundation, Athens, Greece) was grown due to its high productivity, earliness, and excellent adaptability to the soil–climate conditions of Greece. Regarding crop rotation history, durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) has been grown as a monoculture in the wider area. The dominant weeds of this site are sterile oat (Avena sterilis L.), wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis L.), corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas L.), cleavers (Galium aparine L.), scented mayweed (Matricaria chamomilla L.), chickweed [Stellaria media (L.) Vill.)], and ivy-leaved speedwell (Veronica hederifolia L.). These weeds infested the experimental field throughout the experimental period (2023–2024 and 2024–2025), and the species composition in the weed community remained stable because these species were well adapted to the same cultural practices—such as tillage, fertilization, and weed control—that had been implemented at this site for many years during continuous durum wheat monoculture.

2.2. Trial Setup and Design

A Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with four replications (blocks) was established according to the split-plot design. Weed management was the trial factor studied in the main plots with two levels: untreated control, where weeds were left to grow uncontrolled, and stale seedbed, where weeds were controlled before crop sowing with pelargonic acid application.

Intercropping method was the subplot factor with four levels, which were as follows: vetch monocropping, which acted as the control level (VMC), vetch–barley mixed intercropping (VBMXIC), vetch–barley row intercropping (VBROWIC), and vetch–barley relay intercropping (VBRELIC). Trial factors and their levels, as well as their abbreviations used hereafter in the text, are briefly summarized in the following table (Table 2).

Table 2.

Trial factors in main plots and subplots, and the definitions of their levels. The abbreviations used hereafter in the text are also included.

Subplots were 3 m long and 5 m wide, having a size of 15 m2. Main plots were 12 m long and 20 m wide, resulting in a size of 240 m2. In total, 32 experimental units were formed, and the total size of the experimental area was 480 m2 (12 m long and 40 m wide). Weed-free borders without crop plants were maintained between subplots (1 m) and main plots (2 m). Different trial units were established on the same site in 2023 and 2024 to avoid the effects of two consecutive years of trial factors on measured parameters.

Each growing season, the soil was reverse-plowed to a depth of 30–35 cm after the first September rainfalls, then disked twice in mid-November to a depth of 20 cm to break up soil clods and prepare a firm seedbed. In the main plots of the untreated control, vetch was sown immediately after seedbed preparation in rows. Row spacing was 20 cm, defined with handmade metal row markers [9]. A calibrated Pannon K1 hand seed drill (Pannon Machine and Equipment Manufacturer Ltd. Liability Co., Vecsés, Hungary) was used for sowing. Sowing depth was set to 3 cm in all experimental units, and sowing rate varied according to the four intercropping methods. Vetch monocrop was sown at a rate of 200 kg ha−1. In all other subplots where vetch was intercropped with barley, vetch was sown at 150 kg ha−1 and barley at 50 kg ha−1 as a companion supporting crop. For mixed intercropping, seeds of both species were mixed and sown in the same row. In row intercropping subplots, each vetch row alternated with a barley row. In subplots where relay intercropping was applied, barley was sown about five weeks after vetch sowing during short rain-free periods. Additionally, barley sowing was scheduled before predicted rainfall. The barley cultivar “Sebastian” (Sejet Planteforædling I/S, Horsens, Denmark) was grown.

In the main plots of the stale seedbed, no seeds were sown after seedbed preparation. The field was left undisturbed for four weeks to allow weeds to emerge. Weed emergence was stimulated by rainfall. The emerged weed seedlings were controlled with two applications of pelargonic acid. During the 2023–2024 growing season, the first treatment was carried out about three weeks after seedbed preparation, and the second treatment was applied about six weeks after seedbed preparation. However, in the second growing season (2024–2025), pelargonic acid was first applied about two weeks after seedbed preparation, and the second application was conducted about five weeks after seedbed preparation. The initial plan was to follow the manufacturer’s instructions to apply the product twice at a 14-day interval, but this was not possible due to rainfall during those dates. As a result, treatments were performed during periods when there was no rainfall for at least one week before treatment, allowing workers to enter the field.

In addition, application days were scheduled according to weather forecasts, indicating that the day after treatment would also be rain-free. For both treatments, pelargonic acid (Beloukha®, Basf Hellas S.A., Athens, Greece) was applied at an application rate of 1088 g a.i. ha–1 using a Volpi V. black Elektron battery sprayer (Davide & Luigi Volpi S.p.a., Mantua, Italy) calibrated to deliver 300 L ha–1 of spray solution through a brass conical nozzle at a constant pressure of 250 kPa. The applications were performed on sunny days with low wind speed (1–2 km ha−1) during midday hours (14:30–15:30), where the air temperature was not below 15 °C, which is crucial for the efficacy of pelargonic acid. Two days after performing the repeated pelargonic acid treatments, vetch seeds were drilled into the soil.

2.3. Data Collection

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) of weeds was measured around six weeks after treatment completion. “Treatment completion” refers to the day when the last crop was sown in the corresponding plots. In addition to NDVI, vetch NDVI was also measured around eight weeks after treatment completion. The dates of treatment completion differed between experimental units because sowing was delayed to enable pre-sowing weed control with pelargonic acid treatments. Moreover, in subplots where relay intercropping was implemented, weed NDVI was measured around six weeks after barley sowing to not lose the effect of intercropping on weeds. Vetch NDVI and weed biomass were measured around nine weeks after barley sowing. The plan was to perform these measurements around eight weeks after barley sowing, but this could not be achieved due to unfavorable weather conditions.

All assessments were conducted in four square metal quadrats of 0.25 m2 in each subplot, placed in central areas with uniform weed flora. Weed and vetch NDVI were measured using a Trimble GreenSeeker portable optoelectronic sensor (Trimble Agriculture Division, Westminster, CO, USA). The sensor has self-contained illumination in both the red and near-infrared (NIR) regions and measures reflectance in the red and NIR regions of the electromagnetic spectrum according to the following equation:

The sensor measures the green area of the scanned vegetation [23]. In our experiment, NDVI was measured at midday (10:00–14:00) on sunny days by placing the sensor 50 cm above the vegetation of each quadrat [24]. To measure vetch NDVI, weeds and barley plants were removed from the sampling areas, while before measuring weed NDVI, vetch and barley plants had been uprooted from the quadrats. In the areas where vetch NDVI was measured, weeds were uprooted by hand.

These weed samples were also placed in numbered plastic bags and taken to the laboratory, where they were oven-dried at 65 °C (DHG-9025, Knowledge Research S.A., Athens, Greece) for 48 h to measure their dry weight using a digital scale (KF-H2, Zenith S.A., Athens, Greece). Vetch was harvested at the pod maturity stage when grain moisture percentage was 13% in each subplot. The plants were harvested at ground level using scissors from two central 1 m2 subplot areas denoted from a wooden quadrat of this size to measure the number of plants per unit area, the number of pods per plant, the number of grains per pod, and the weight of 1000 grains to estimate the final grain yield of the crop, which is presented.

The exact dates of key field activities for completing experimental treatments, successfully establishing the trial field, and collecting all data are presented below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Dates of key field activities during the experimental period.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normal distribution of all data was checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test [25], while homoscedasticity was validated with Levene’s test [26]. All data were subjected to a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), in which the effects of growing season, weed management, and intercropping were considered fixed, while replicates (blocks) were considered as random effects. All analyses were performed at a significance level of a = 0.05. Pairwise mean comparisons were performed using Fischer’s least significant difference (LSD) test. Statistix 10 (Analytical Software 2105 Miller Landing Rd., Tallahassee, FL, USA) was the software used for data analysis.

3. Results

The factors of weed management and intercropping affected weed NDVI, weed biomass, vetch NDVI, and vetch grain yield (p < 0.001). The interaction between weed management and intercropping factors had a significant effect on weed NDVI (p < 0.001), weed biomass, and vetch NDVI (p < 0.01). Moreover, vetch grain yield was significantly (p < 0.05) influenced by the growing season (Table 4).

Table 4.

The effects of growing season (GS), weed management (WM), intercropping (IC), and their interactions on weed NDVI, weed biomass, vetch NDVI, and vetch grain yield. Error (a), Block × GS; Error (b), Block × WM (GS); Error (c), Block × IC (WM) × GS.

3.1. Weed Parameters

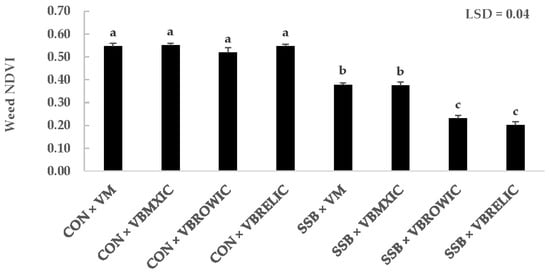

Weed NDVI received the highest values (above 0.52) in all experimental units where weeds were not controlled through the stale seedbed cultural practice, i.e., CON × VM, CON × VBMXIC, CON × VBROWIC, and CON × VBRELIC. The combinations of stale seedbed along with vetch–barley row and relay intercropping, i.e., SSB × VBROWIC and CON × VBRELIC, resulted in the lowest index values (below 0.23). Intermediate values of weed NDVI (0.37–0.38) corresponded to the interactions SSB × VM and SSB × VBMXIC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pairwise mean comparisons of weed NDVI between the levels of the significant interaction (WM × IC) between weed management (WM) and intercropping (IC). The different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. Vertical bars indicate standard errors.

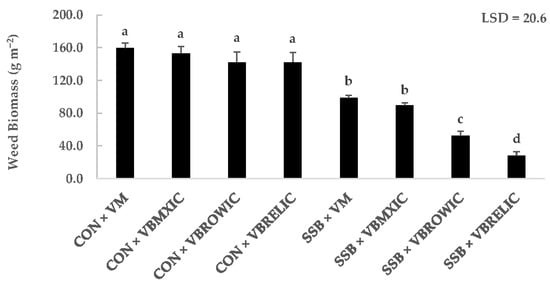

Weed biomass ranged between 140 and 160 g m−2 in all trial units assigned to the untreated main plots where weeds were not controlled with pelargonic acid (CON × VM, CON × VBMXIC, CON × VBROWIC, and CON × VBRELIC). It was found that these combinations did not differ significantly from each other (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pairwise mean comparisons of weed biomass (g m−2) between the levels of the significant interaction (WM × IC) between weed management (WM) and intercropping (IC). The different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. Vertical bars indicate standard errors.

In comparison to these combinations, SSB × VM and SSB × VBMXIC caused some reduction (30–44%) in weed dry weight per unit area, with no significant difference observed between these two interactions. However, SSB × VBROWIC reduced weed biomass by 41% and 47% compared to SSB × VBMXIC and SSB × VM, respectively. The most weed-suppressive interaction out of all studied interactions was SSB × VBRELIC, which resulted in only 28.3 g m−2 of weed biomass—up to 83% lower than that recorded for CON × VM. In the trial units of SSB × VBRELIC, weed biomass decreased by 46% compared to SSB × VBRELIC. Moreover, compared to SSB × VBMXIC and VM, SSB × VBRELIC reduced weed biomass by 68% and 71%, respectively.

3.2. Vetch Parameters

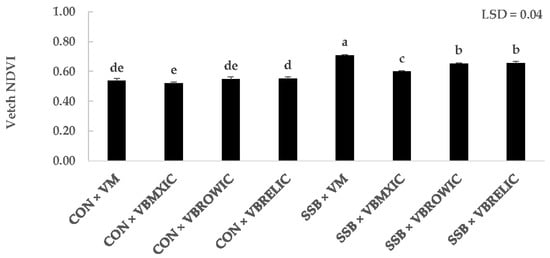

Vetch NDVI was highest (0.71) in the trial units where the stale seedbed was combined with vetch monocropping (SSB × VM). The next highest values corresponded to SSB × VBROWIC and SSB × VBRELIC. Lower values that were below 0.55 were observed in experimental units where weeds were left uncontrolled. Furthermore, the interaction CON × VBRELIC showed a significantly higher vetch NDVI than CON × VBMXIC. CON × VBROWIC and CON × VM tended to improve NDVI compared to CON × VBMXIC, but the differences were not clearly significant. The same pattern was observed when CON × VBRELIC was compared with CON × VBROWIC and CON × VM (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pairwise mean comparisons of vetch NDVI between the levels of the significant interaction (WM × IC) between weed management (WM) and intercropping (IC). The different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. Vertical bars indicate standard errors.

Vetch grain yield was slightly but statistically significantly higher (7%) during the second growing season (2024–2025) compared to the first growing season (2023–2024), as shown in the table below (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pairwise mean comparisons of vetch grain yield (kg ha−1) between the different levels of the main effects which were as follows: growing season (GS), weed management (WM), and intercropping (IC). The different lowercase letters indicate significant differences.

In addition, the double application of pelargonic acid in stale seedbed (SSB) main plots resulted in almost 42% higher grain yield compared to the untreated control (CON), where weeds were left to grow without receiving any weed control treatment. As for the mean comparisons among the four different intercropping manipulations, relay intercropping of vetch and barley (VBRELIC) increased vetch grain yield by 7%, 22%, and 29% compared to row intercropping of vetch and barley (VBROWIC), monocropping of vetch (VM), and mixed intercropping of vetch and barley (VBMXIC), respectively. VBROWIC resulted in 16% and 23% higher grain yield compared to VM and VBMXIC, respectively, while VM subplots displayed 8% higher value than VBMXIC.

4. Discussion

Stale seedbed along with barley intercropping resulted in the lowest NDVI and biomass of weeds in the vetch crop. These results agree with recent works in forage crops in Greece, where a false seedbed along with mixed annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) intercropping achieved notable levels of weed suppression [8]. In stale seedbed plots, row intercropping suppressed weeds more effectively than mixed intercropping, probably due to better space exploitation by the cultivated plants and improved resource exploitation compared to weeds. This has also been recommended by Gu et al. [27], who noted that a more spatially uniform distribution of crop plants is known to better reduce weeds, especially when a competitive component crop is used in intercropping schemes to preempt resources.

The combination of stale seedbed and relay intercropping was also effective in reducing weed growth in the trial field. This indicates that the application of pelargonic acid in the stale seedbed main plots eliminated the first early cohorts of weeds, as in previous works [11]. Vetch plants had the chance to grow in a less competitive environment and gain competitive advantage against weeds. Afterwards, the presence of barley and its coexistence with well-developed vetch plants facilitated longer period of weed suppression when relay intercropping was implemented [28,29,30]. However, there is always a concern regarding weed adaptation to stale seedbed cultural practices via shifting germination timing to later in the season i.e., after application of the burndown non-selective herbicide for pre-sowing weed control. There is also a concern that the implementation of this cultural practice may favor the emergence of different weed species that may be more competitive and aggressive. It is rational to consider such potential limitations, as weeds consistently exhibit adaptability to various environments [31].

When combined with a cultural practice that improves crop competition, weed suppression becomes optimal, especially when expressed in terms of weed biomass [9]. Regarding weed parameters, there were no significant differences between growing seasons, most probably due to similar rainfall distribution during the periods when the field was prepared according to the stale seedbed technique [32,33,34]. Differences between growing seasons would probably have been observed if the years were characterized by different precipitation heights; when water deposition in soil increases, weed emergence increases, and stale seedbeds are expected to be more effective [35]. Concerning vetch NDVI, it was higher in trial units where weeds were controlled with the double pelargonic acid application and the crop was grown as a monoculture. Our results can be explained by the fact that, in this plot, vetch plants grew with less weed competition compared to the untreated control and without competition from the companion crop, i.e., barley. This indicates that a common challenge in intercropping systems is interspecific competition between intercropped plants, as emphasized by other researchers [36,37,38].

In contrast to weed biomass and the other parameters investigated in this study, vetch grain yield was significantly influenced by the growing season and was specifically higher in the second than in the first year of the trial. The slight yield increase during 2024–2025 may be attributed to the higher rainfall observed from April to June in 2025 (98.2 mm) compared to the rainfall observed during the same months in 2024 (18.2 mm). When vetch is cultivated for grain harvest, sufficient water supply during the flowering, pod formation, and seed filling periods is crucial for achieving optimal yields [39,40,41]. The stale seedbed led to an increase in grain yield compared to the untreated control due to satisfactory weed control achieved through pelargonic acid applications. Similar results have been previously reported under similar soil–climate conditions [8,11,32].

In addition, the higher yields in relay intercropping subplots indicate that vetch did not suffer from interspecific competition in the crucial early growth stages. After these crucial periods, barley shaded the ground, and some broadleaf weeds, such as wild mustard and corn poppy did not cause yield reduction [42,43,44,45]. Even in relay intercropping subplots, barley competed with vetch, but a companion crop in an intercrop is much more manageable than weeds, which can show unpredictable aggressiveness and cause severe yield losses in any crop and under any environment [2].

5. Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that a stale seedbed along with either relay or row intercropping with barley can provide sufficient weed suppression in vetch grown for grain. Stale seedbed and relay intercropping appear to result in higher yields, although their effects may vary between growing seasons. This is one of the first studies to highlight the importance of pelargonic acid as a new weed control tool in annual crops when the stale seedbed concept is adopted. Further research is needed to evaluate additional agroecological weed management practices in more cropping systems and environments to support the agroecological transition of agriculture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G. and I.T.; methodology, P.K.; software, I.G.; validation, D.P., N.A. and P.K.; formal analysis, D.P.; investigation, N.A.; resources, H.K.; data curation, D.P.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.T.; visualization, P.K.; supervision, I.T.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research project was implemented under the framework of the H.F.R.I call “Basic Research Financing (Horizontal Support of All Sciences)”, under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan “Greece 2.0”, funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (H.F.R.I. Project Number: 16383).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the need for proper guidance in interpreting the experimental datasets.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the local landowners for providing part of their land to conduct this two-year field trial and to establish the project’s Living Lab (LL).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gianessi, L.P. The increasing importance of herbicides in worldwide crop production. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E. Agronomic weed control: A trustworthy approach for sustainable weed management. In Non-Chemical Weed Control; Jabar, K., Chauhan, B.S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Westwood, J.H.; Charudattan, R.; Duke, S.O.; Fennimore, S.A.; Marrone, P.; Slaughter, D.C.; Swanton, C.; Zollinger, R. Weed management in 2050: Perspectives on the future of weed science. Weed Sci. 2018, 66, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Andujar, J.L. Integrated Weed Management: A shift towards more sustainable and holistic practices. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutagayout, A.; Bouiamrine, E.H.; Synowiec, A.; El Oihabi, K.; Romero, P.; Rhioui, W.; Nassiri, L.; Belmaha, S. Agroecological practices for sustainable weed management in Mediterranean farming landscapes. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 8209–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, F.E. Current status and future prospects in herbicide discovery. Plants 2019, 8, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merfield, C.N. Integrated weed management in organic farming. In Organic Farming, 2nd ed.; Chandran, S., Unni, M.R., Sabu, T., Meena, D.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 31–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gazoulis, I.; Kanatas, P.; Antonopoulos, N.; Tataridas, A.; Travlos, I. False seedbed for agroecological weed management in forage cereal–legume intercrops and monocultures in Greece. Agronomy 2023, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazoulis, I.; Papazoglou, E.G.; Petraki, D.; Antonopoulos, N.; Danaskos, M.; Kokkini, M.; Kanatas, P.; Travlos, I. Stale Seedbed and narrow row spacing combinations to suppress weeds in kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). Weed Res. 2025, 65, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merfield, C.N. False and Stale Seedbeds: The most effective non-chemical weed management tools for cropping and pasture establishment. FFC Bull. 2015, 2015, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kanatas, P.; Travlos, I.; Papastylianou, P.; Gazoulis, I.; Kakabouki, I.; Tsekoura, A. Yield, quality and weed control in soybean crop as affected by several cultural and weed management practices. Not. Bot. Hort. Agrobot. 2020, 48, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.; Penner, D. Organic acid enhancement of pelargonic acid. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frans, R.; McClelland, M.; Kennedy, S. Chemical and cultural methods for bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon) control in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Weed Sci. 1982, 30, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanatas, P.; Antonopoulos, N.; Gazoulis, I.; Travlos, I.S. Screening glyphosate-alternative weed control options in important perennial crops. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.A.; Ransom, C.V.; Reeve, J.R.; Black, B.L. Mulch and organic herbicide combinations for in-row orchard weed suppression. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2011, 11, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.; Eigenmann, M.; Keller, M. Pelargonic acid for weed control in onions: Factors affecting selectivity. Jul. Kühn Arch. 2020, 464, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Kardasz, P.; Miziniak, W.; Bombrys, M.; Kowalczyk, A. Desiccant activity of nonanoic acid on potato foliage in Poland. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2019, 59, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Khanal, U.; Stott, K.J.; Armstrong, R.; Nuttall, J.G.; Henry, F.; Christy, B.P.; Mitchell, M.; Riffkin, P.A.; Wallace, A.J.; McCaskill, M.; et al. Intercropping—Evaluating the advantages to broadacre systems. Agriculture 2021, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Shrestha, S.; Kunwar, S.; Tseng, T.-M. Crop diversification for improved weed management: A review. Agriculture 2021, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, A.; Sadras, V.O.; Roberts, P.; Doolette, A.; Zhou, Y.; Denton, M.D. Legume-oilseed intercropping in mechanised broadacre agriculture—A review. Field Crops Res. 2021, 260, 107980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, J.; Reckling, M.; Ewert, F. Diverse approaches to crop diversification in agricultural research. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebman, M.; Dyck, E. Crop rotation and intercropping strategies for weed management. Ecol. Appl. 1993, 3, 92–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, N.; Wang, Z.; Ma, B.L.; Belec, C.; Vigneault, P. A comparison of crop data measured by two commercial sensors for variable-rate nitrogen application. Precis. Agric. 2009, 10, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Si, J.; Feng, B.; Li, S.; Wang, F.; Sayre, K. Differential responses of two types of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to autumn- and spring-applied mesosulfuron-methyl. Crop Prot. 2009, 28, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. Robust tests of equality of variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics, Essays in Honor of Harold Hoteling; Olkin, I., Ghurye, S.G., Hoeffding, W., Madow, W.G., Mann, H.B., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Bastiaans, L.; Anten, N.P.; Makowski, D.; van der Werf, W. Annual intercropping suppresses weeds: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 322, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amossé, C.; Jeuffroyb, M.H.; Celettea, F.; Davida, C. Relay-intercropped forage legumes help to control weeds in organic grain production. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 49, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, F.; Lazzaro, M.; Ruggeri, M.; Carlesi, S.; Meriggi, P.; Moonen, A.C. Relay intercropping can efficiently support weed management in cereal-based cropping systems when appropriate legume species are chosen. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, L.; Xiang, B.; Yang, W.Y. Suppression of weeds and increases in food production in higher crop diversity planting arrangements: A case study of relay intercropping. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S. Grand challenges in weed management. Front. Agron. 2020, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, S.; Selvi, M.; Mercati, S.; Cardinali, G.; Mercati, V.; Mazzoncini, M. Stale seedbed preparation for sustainable weed seed bank management in organic cropping systems. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemens, M.M.; Van Der Weide, R.; Bleeker, P.; Lotz, L. Effect of stale seedbed preparations and subsequent weed control in lettuce (cv. Iceboll) on weed densities. Weed Res. 2007, 47, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhullar, M.S.; Gill, G. Integrated weed management in dry-seeded rice using stale seedbeds and post sowing herbicides. Field Crop. Res. 2018, 224, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shem-Tov, S.; Fennimore, S.A.; Lanini, W.T. Weed management in lettuce (Lactuca sativa) with preplant irrigation. Weed Τechnol. 2006, 20, 1058–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celette, F.; Findeling, A.; Gary, C. Competition for nitrogen in an unfertilized intercropping system: The case of an association of grapevine and grass cover in a Mediterranean climate. Eur. J. Agron. 2009, 30, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Dai, J.; Ding, K.; He, N.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xu, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, H. Managing interspecific competition to enhance productivity through selection of soybean varieties and sowing dates in a cotton–soybean intercropping system. Field Crops Res. 2024, 316, 109513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, C.; Waswa, W.; Aliyu, K.T.; Claessens, L.; Mead, A.; Schöb, C.; Vanlauwe, B.; Storkey, J. Predicting intercrop competition, facilitation, and productivity from simple functional traits. Field Crops Res. 2023, 297, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E. Effect of supplemental irrigation on vetch yield components. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 213, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fırıncıoğlu, H.K.; Ünal, S.; Erbektaş, E.; Doğruyol, L. Relationships between seed yield and yield components in common vetch (Vicia sativa ssp. sativa) populations sown in spring and autumn in central Turkey. Field Crops Res. 2010, 116, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, S.K.; Ryan, J. Differential impacts of climate variability on yields of rainfed barley and legumes in semi-arid Mediterranean conditions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2013, 59, 1659–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitich, L.W. Corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas L.). Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinke, G.; Kapcsándi, V.; Czúcz, B. Iconic Arable Weeds: The significance of corn poppy (Papaver rhoeas), cornflower (Centaurea cyanus), and field larkspur (Delphinium consolida) in Hungarian ethnobotanical and cultural heritage. Plants 2023, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, S.I.; Beckie, H.J.; Thomas, A.G.; McDonald, T. The biology of Canadian weeds. 8. Sinapis arvensis L. (updated). Can. J. Plant Sci. 2000, 80, 939–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, M.; Kavhiza, N.J.; Bayat, M.; Pakina, E. Wild mustard (Sinapis arvensis) competition and control in rain-fed spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 2021, 11, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).