Abstract

Importin α (IMPα) proteins are key mediators of nucleocytoplasmic transport and play crucial roles in plant development and stress adaptation. Here, we performed a genome-wide identification of the IMPα gene family in Glycine max, followed by gene structure and conserved motif analyses, chromosomal distribution and duplication inference, synteny and selection (Ka/Ks) analyses, and expression profiling across tissues and stress conditions using public RNA-seq datasets and expression browsers. The GmIMPα genes exhibited diverse gene structures and conserved motifs, suggesting functional diversification within the family. Segmental duplication was identified as the main contributor to family expansion, and most duplicated gene pairs underwent purifying selection. Promoter analysis revealed numerous stress- and hormone-responsive cis-elements, implying complex transcriptional regulation. Expression profiling demonstrated that GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα7 were strongly induced under drought, heat, and salt stresses, indicating potential roles in abiotic stress tolerance. Collectively, our results provide a comprehensive framework for the evolution and functional divergence of the GmIMPα family in soybean and offer candidates for improving stress resilience.

1. Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max), a globally cultivated crop, is the world’s leading source of vegetable oil and plant-derived protein, with byproducts serving as essential components of animal feed and forage [1,2,3]. According to the latest statistics from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (https://www.fao.org/home/en/, accessed on 30 October 2025), global soybean production exceeded 371 million metric tons in 2023, highlighting its central role in the global supply of vegetable oil and protein. However, its yield and quality are severely constrained by biotic stresses such as pests, diseases, and weeds, as well as abiotic factors including extreme temperatures, drought, and salinity [4,5,6]. Considerable research has therefore focused on drought and salt stress, particularly their inhibitory effects on germination and seedling growth [7,8]. Meanwhile, advances in soybean genomics and bioinformatics have enabled systematic analyses of gene families, shedding light on their evolution, molecular features, and biological functions [9,10,11]. Therefore, exploring the functions of stress-resistance genes will provide a powerful tool for improving and optimizing cultivated soybean varieties, while offering high-quality resources for soybean production.

Nucleocytoplasmic transport is a fundamental and conserved process in eukaryotes [12]. It is mediated by nuclear transport receptors (NTRs), Ran GTPase, and nuclear pore complexes (NPCs) [13,14,15]. Within this system, the Karyopherin (KAP) superfamily—including Importin α (IMPα) and Importin β (IMPβ)—is central [16]. IMPα proteins act as adaptors that recognize nuclear localization signals (NLSs) and mediate cargo transport through NPCs [17,18]. The IMPα family, conserved yet functionally diversified across eukaryotes, contains three canonical domains: the N-terminal importin β-binding (IBB) domain, central armadillo (Arm) repeats, and a C-terminal domain for export factor binding [19,20,21]. Initially identified in algae [22], IMPα proteins have since been shown to regulate not only nuclear import but also diverse processes including gene expression, disease resistance, cell cycle progression, and developmental differentiation [23,24,25].

In plants, IMPα family members play critical roles in development [26,27,28]. Arabidopsis thaliana and Zea mays possess nine and seven IMPα genes, respectively, which exhibit diverse tissue-specific expression patterns and notable functional redundancy [27,29]. The Arabidopsis impα1,2,3 triple mutant exhibits abnormal trichome development and impaired nuclear localization of GLABRA2 (GL2) in trichomes [30]. AtIMPα6 interacts with the Aux/IAA protein BODENLOS (BDL) to regulate hypophysis development during embryogenesis and primary root formation [31]. The down-regulated expression of IMPα genes in rice spikelets is involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression and cell division [32]. In tomato, the slimp3 mutation triggers premature leaf senescence and accelerated fruit ripening [33]. Structural analyses further reveal that binding specificity between IMPα and the NLS of DNA repair proteins is essential for cellular homeostasis [21,34]. These findings highlight the dual roles of IMPα proteins in both nuclear transport and developmental regulation Interestingly, studies have shown that IMPα gene also participates in responses to abiotic stress and disease resistance [35,36]. Arabidopsis SWO1 (SWOLLEN 1) interacts with IMPα1 and IMPα2 to regulate cell wall-related gene expression, thereby enabling plants to maintain cell wall integrity in response to high salinity [37]. Arabidopsis IMPα2 protein confers nonhost resistance against the rice sheath blight pathogen Rhizoctonia solani by activating SA-mediated early immunity [38]. Arabidopsis impα3 single mutant displayed significantly increased susceptibility to virulent oomycete pathogens [39]. Arabidopsis impα1/2/4 triple mutant accumulates SA and reactive oxygen species (ROS), enhancing resistance to Colletotrichum higginsianum [40]. PsIMPα1 mediates the oxidative stress response and is required for the pathogenicity of Phytophthora sojae [41]. In rice, the impα4 knockout mutant confers resistance to rice stripe virus (RSV) by increasing callose deposition [42]. Partial downregulation of IMPα gene expression enhances resistance to yellow dwarf disease (BYDV) in common wheat [43].

We identified and analyzed the GmIMPα gene family in soybean, detailing features such as physicochemical properties, gene structures, chromosomal locations, and expression patterns. We also examined phylogenetic relationships, cis-acting regulatory elements, and protein–protein interaction networks. Expression profiling revealed rapid upregulation of GmIMPα genes in response to drought, heat, low-temperature, salt, and hormone stresses. These results offer insights into GmIMPα-mediated stress responses and provide genetic resources for enhancing soybean stress resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of GmIMPα Family Members in Soybean

A total of 27 soybean genomes, representing a diverse array of Glycine max cultivars and lines, were analyzed (Table S1). High-quality genome sequences and annotation files were retrieved from the SoyOmics database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/soyomics/index, accessed on 15 July 2025) [44]. Hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles for the IMPα protein domains—Arm_3 (PF16186), IBB (PF01741), and Arm (PF00514)—were obtained from the InterPro database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/, accessed on 20 July 2025) [45]. Candidate GmIMPα proteins were identified using the Simple HMM Search function in TBtools-II [46], applying an E-value threshold of 1 × 10−5 to eliminate redundant sequences. Candidate proteins were subsequently screened using the SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/, accessed on 1 August 2025) and NCBI Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd, accessed on 1 August 2025) to confirm the presence of Arm_3, IBB, and Arm domains [47]. This validation step was essential for the accurate identification of members within the soybean IMPα gene family. Based on the presence/absence patterns of IMPα genes across 27 soybean accessions, the genes were categorized into core, soft core, dispensable, and private groups, following the established pangenome definitions [48]. A total of 17 authentic GmIMPα gene were identified and confirmed, then named GmIMPα1 to GmIMPα17 according to their chromosomal positions. The physicochemical characteristics of the identified IMPα proteins—such as amino acid count, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity—were analyzed using the ProtParam tool on the ExPASy server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 5 August 2025).and subcellular localization was predicted with Cell-PLoc 2.0 (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/Cell-PLoc-2/, accessed on 5 August 2025) [49].

2.2. Evolutionary Relationships, Conserved Domain, and Gene Structure of GmIMPα Family Genes

Protein sequences of the identified GmIMPα proteins were used to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree in MEGA version 11.0, the maximum likelihood (ML) method was applied with 1000 bootstrap replicates (sequence information provided in Table S2) [50]. Conserved motifs were identified using the MEME Suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme, accessed on 7 August 2025), with a maximum of 10 motifs specified and a motif width range of 6 to 50 amino acids [51]. The resulting MEME XML output file was imported into TBtools-II for the visualization of protein motifs. Gene structures were visualized using GSDS 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/, accessed on 10 August 2025) in combination with the soybean genome annotation file [52].

2.3. Chromosome Localization, Collinearity, and Ka/Ks Analysis of GmIMPα Gene Family

Chromosomal positions of GmIMPα genes were mapped using the genomic GFF3 annotation file in TBtools-II. Collinear gene pairs within the GmIMPα family were detected using the Multiple Collinearity Scan toolkit (MCScanX) in TBtools-II. Both segmental and tandem duplication events were then defined based on the synteny results. Furthermore, KaKs_Calculator 3.0 software was used to compute the synonymous substitution rate (Ks), nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka), and the evolutionary ratio (Ka/Ks) between duplicate pairs of GmIMPα genes [53]. Protein sequence similarity was analyzed using the Protein Pairwise Similarity Matrix toolkit within TBtools-II, and the results were visualized through its integrated HeatMap graphics module.

2.4. Evolutionary Analysis Between Glycine max and Other Plants

Genome sequences, protein sequences, and GFF3 annotation files for Arabidopsis thaliana (TAIR10), Glycine soja (W05.a1), Gossypium hirsutum (TM-1_v2.1), Triticum aestivum (ChineseSpring_725_v2.1), Oryza sativa (IRGSP_1_0), and Zea mays (B73-REFERENCE-NAM-5.0) were retrieved from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/, accessed on 15 August 2025) [54]. Homology of IMPα genes between cultivated soybean (Glycine max) and six comparative species (Glycine soja, Arabidopsis thaliana, Gossypium hirsutum, Triticum aestivum, Oryza sativa, and Zea mays) was analyzed using the Dual-Synteny Plot program in TBtools-II. Collinear relationships were further assessed using the One-Step MCScanX module in TBtools-II, and the resulting syntenic networks were visualized to illustrate evolutionary conservation patterns across species. Full-length IMPα protein sequences from Arabidopsis, soybean, and maize were aligned using the Muscle algorithm in MEGA11 (sequence information provided in Table S2). Phylogenetic trees were constructed utilizing the maximum likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and the resulting trees were visualized on the iTOL online platform (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 15 August 2025) [55].

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements, Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment Analysis, and Protein Interaction of GmIMPα Gene Family

Cis-acting regulatory elements in the 2000 bp promoter regions upstream of the ATG start codon in GmIMPα genes were predicted using the PlantCARE online platform (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 20 August 2025) [56]. The cis-acting elements were categorized based on the downloaded prediction file, with a focus on categories such as light responsiveness, growth and development, environmental stress response, and hormone response. The sorted files were visualized as heat maps using TBtools-II. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of GmIMPα proteins was conducted, and the results were visualized using the GO enrichment toolkit in TBtools-II. The protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of GmIMPα proteins was constructed using STRING version 11.5 (https://cn.string-db.org/, accessed on 20 August 2025) [57].

2.6. Tissue-Specific and Stress-Related Expression Profiles of GmIMPα Gene Family

RNA-seq datasets for the GmIMPα genes were retrieved from the SoyOmics database (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/soyomics/index, accessed on 23 August 2025) [44]. The data encompassed various developmental stages across different tissues, including leaves, roots, stems, pods, and flowers. The RNA-seq expression patterns of GmIMPα genes were visualized using the eFP tool within the transcriptomics module of the SoyOmics database. RNA-seq datasets derived from soybean subjected to various stress conditions—including drought and heat (Accession: PRJNA399013), low temperature (Accession: PRJNA482945), salinity (Accession: PRJNA246058), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA; Accession: PRJNA218823), jasmonic acid (JA; Accession: PRJNA218821), and ethylene (ETH; Accession: PRJNA218825)—were obtained from the Soybean Expression Atlas v2 (https://soyatlas.venanciogroup.uenf.br/, accessed on 23 August 2025) [58]. Gene expression levels were normalized as transcripts per million (TPM), and heatmaps of expression profiles were generated in TBtools-II.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Physicochemical Properties Analysis of GmIMPα Gene Family

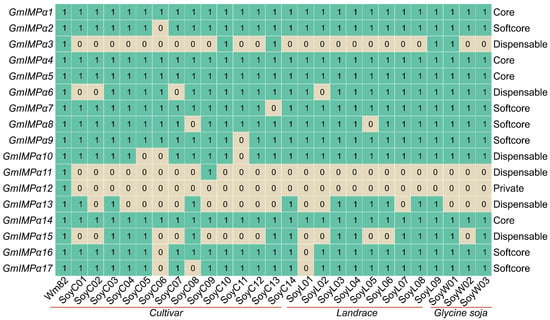

A total of 17 GmIMPα genes were systematically identified in the Williams 82 soybean genome (Figure 1). Based on their presence across 27 soybean genomes, these genes were classified into four categories. Core genes (present in all 27 genomes) comprised four members: GmIMPα1, GmIMPα4, GmIMPα5, and GmIMPα14. Softcore genes (present in 25–26 genomes) included six members: GmIMPα2, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα8, GmIMPα9, GmIMPα16, and GmIMPα17. Dispensable genes (present in 2–24 genomes) encompassed six members, among which GmIMPα11 was detected in only two soybean cultivars. Finally, a single Private gene (GmIMPα12) was identified, present in only one genome. This classification framework provides an important foundation for elucidating the evolutionary dynamics and functional diversification of soybean IMPα genes.

Figure 1.

Number of IMPα homologs in wild and cultivated soybean pan-genomes. Rows represent GmIMPα family genes arranged by chromosomal physical position; columns correspond to different individual genomes (see Table S1 for variety numbers). Gene classification follows pan-genome definitions: Core genes are shared by all individuals (100%); soft core genes are part of the non-essential genome subset, present in 95–98% of individuals; dispensable genes are shared by 5–94% of individuals; private genes are those found only in a single individual. The numbers within the boxes indicate gene presence, where ‘1’ denotes the gene is present and ‘0’ denotes it is absent.

Table 1 summarizes the identification and physicochemical properties of seventeen GmIMPα genes (GmIMPα1–GmIMPα17) in the soybean genome. The deduced protein sequences range from 438 to 532 amino acids, with predicted molecular weights between 48.78 and 59.00 kDa and theoretical isoelectric points (pI) of 4.75–5.55. Protein stability analysis revealed that GmIMPα14 had the highest instability index (55.20), whereas GmIMPα1 exhibited the highest aliphatic index (113.35). With the exception of GmIMPα1 (GRAVY = 0.02) and GmIMPα6 (GRAVY = 0.03), all GmIMPα proteins displayed negative GRAVY values, indicating a predominantly hydrophilic nature. Subcellular localization predictions suggested that 14 GmIMPα proteins were localized to both the cytoplasm and nucleus, while GmIMPα1, GmIMPα6, and GmIMPα14 were predicted to be cytoplasmic only. Collectively, these physicochemical features highlight the structural diversity and potential functional specialization of the soybean importin α protein family.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characterization of IMPα gene family members in Glycine max.

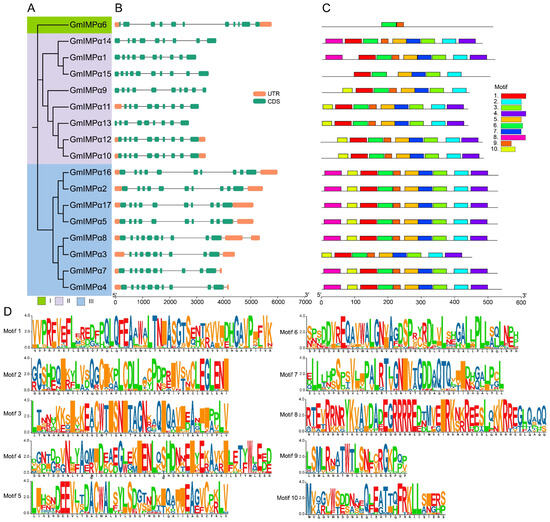

3.2. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of GmIMPα Genes

Phylogenetic analysis classified the soybean GmIMPα gene family into three subfamilies (Figure 2A), each distinguished by a different background color in the phylogenetic tree. Gene structure analysis revealed that members of the GmIMPα gene family contain 9 to 11 exons and 8 to 10 introns, with significant variation in gene length among the different subfamilies. Specifically, the average gene length of Clade II members is considerably shorter than that of Clade I and Clade III. Notably, some genes located on adjacent branches of the phylogenetic tree often exhibit similar gene structure characteristics. For example, in Clade II, the gene lengths of GmIMPα10 and GmIMPα12 are comparable (3369 bp and 3357 bp, respectively), and both genes possess 10 exons. Further sequence analysis of the GmIMPα family proteins identified ten conserved motifs (Figure 2C,D), with amino acid lengths as follows: Motifs 1, 4, and 8 consist of 50 amino acids; Motif 6 consists of 44 amino acids; Motifs 2, 3, 5, and 7 each comprise 41 amino acids; Motif 10 consists of 29 amino acids; and Motif 9 is the shortest, containing only 21 amino acids. Among these conserved motifs, Motif 6 is highly conserved and consistently positioned across all GmIMPα protein sequences, whereas Motifs 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 are conserved in 16 members except GmIMPα6. It is particularly noteworthy that, although Clade I contains only GmIMPα6 and its gene structure is similar to those of other subfamily members, its motif composition displays significant differences, suggesting possible functional divergence of this gene. In summary, the combined analysis of gene structure and conserved motifs provides strong evidence supporting the phylogenetic relationships within the GmIMPα gene family.

Figure 2.

Structural and conserved motif analysis of GmIMPα genes. (A) Phylogenetic tree of GmIMPα genes constructed using MEGA. Subfamilies are designated as Clades I–III. (B) Exon–intron structures visualized using the GSDS web server. The scale bar at the bottom indicates the gene length in base pairs (bp). (C) Distribution of 10 conserved motifs identified with the MEME suite. The motif patterns illustrate the similarities among members within their respective subfamilies, with a scale bar at the bottom indicating protein length. (D) Schematic representation of conserved motif organization.

3.3. Gene Duplication Analysis and Chromosomal Distribution of GmIMPαs

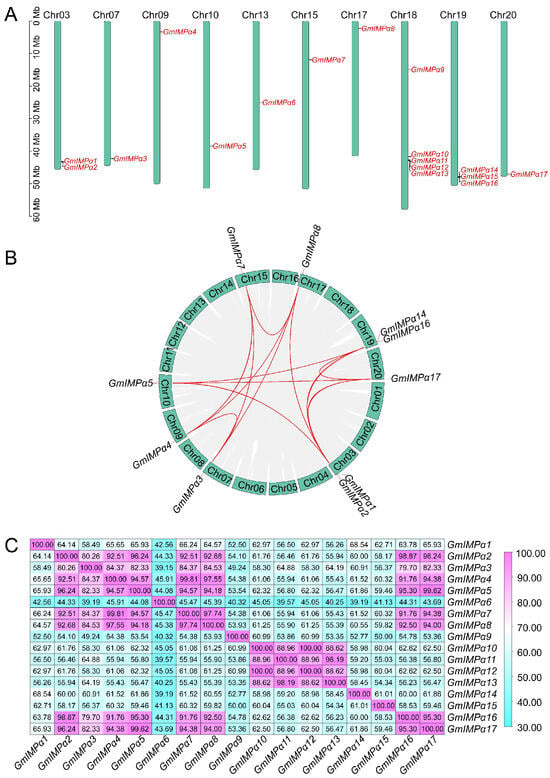

Chromosomal mapping showed that the 17 GmIMPα genes were distributed across 10 soybean chromosomes (Figure 3A). Among them, chromosomes 7, 9, 10, 13, 15, 17, and 20 each contained one GmIMPα gene, chromosome 3 harbored two, and chromosome 19 carried three. Notably, five genes—GmIMPα9, GmIMPα10, GmIMPα11, GmIMPα12, and GmIMPα13—were clustered on chromosome 18, indicating a broad yet uneven genomic distribution of the GmIMPα family.

Figure 3.

Genomic analysis of soybean GmIMPα genes. (A) Chromosomal distribution of GmIMPα family members. Chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of each chromosome. A scale bar on the left shows the actual chromosome length (in megabase pairs, Mb). This panel highlights the specific genomic locations of GmIMPα genes, providing insight into their chromosomal distribution within the soybean genome. (B) Syntenic relationships of GmIMPα genes within the soybean genome. Chromosome numbers are shown in green boxes. Red lines indicate syntenic relationships among GmIMPα gene pairs, while gray lines represent collinear blocks across the soybean genome. (C) Heatmap of protein sequence similarity among GmIMPα members. Darker pink shades indicate higher levels of protein sequence similarity.

Gene duplication is a major evolutionary force driving gene family expansion. Whole-genome duplication analysis revealed 14 segmental duplication events involving 10 GmIMPα genes (Figure 3B), whereas no tandem duplication was detected. Most GmIMPα genes participated in multiple duplication events, with GmIMPα2 showing the highest frequency (four duplication pairs). This suggests that segmental duplication has been the predominant mechanism underlying the expansion of the GmIMPα gene family. Selection pressure analysis (Table 2) demonstrated that 13 GmIMPα segmental duplication pairs exhibited Ka/Ks ratios < 1, indicative of purifying selection. In contrast, the GmIMPα1/GmIMPα14 pair displayed a Ka/Ks ratio of 1.167 (>1), suggesting that this duplication pair underwent positive selection, with advantageous mutations likely retained during evolution. Protein sequence alignment (Figure 3C) further showed that, except for GmIMPα1/GmIMPα14, all other duplicated pairs shared more than 80% sequence similarity. Together, these findings highlight the uneven chromosomal distribution, predominant role of segmental duplication, and contrasting selective pressures that have shaped the evolutionary trajectory of the soybean GmIMPα gene family.

Table 2.

The ratio of Nonsynonymous substitution (Ka) and Synonymous substitution (Ks) of segmental duplication gene pairs in the soybean GmIMPα family.

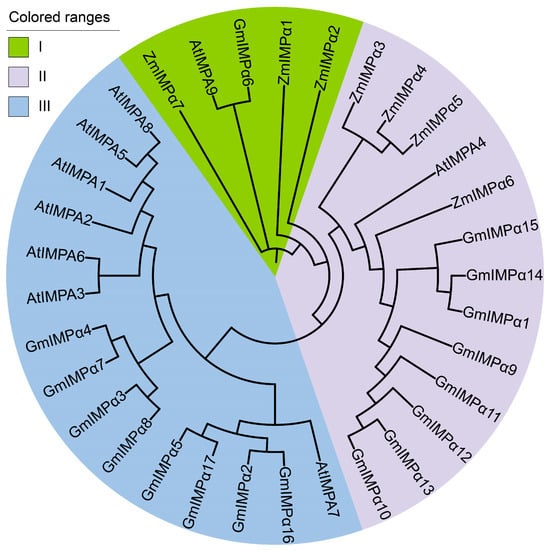

3.4. Phylogenetic and Syntenic Analyses of IMPα Genes in Glycine max and Representative Plants

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of the IMPα gene family, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using IMPα protein sequences from soybean (Glycine max), Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), and maize (Zea mays) (Figure 4). The analysis revealed that the 17 soybean GmIMPα proteins, 9 Arabidopsis AtIMPα proteins, and 7 maize ZmIMPα proteins were clustered into three distinct evolutionary clades (Clades I–III). Clade I comprised 1 GmIMPα protein, 1 AtIMPα protein, and 3 ZmIMPα proteins. Clade II contained 8 GmIMPα proteins, 1 AtIMPα protein, and 4 ZmIMPα proteins. Clade III was composed of 8 GmIMPα proteins, 7 AtIMPα proteins, and 4 ZmIMPα proteins. This distribution indicates that soybean IMPα genes are widely dispersed among the three clades, suggesting both lineage-specific expansion and conservation of gene family members. Cross-species comparative analysis further supports the presence of conserved evolutionary constraints acting on the IMPα gene family, highlighting shared ancestral origins among monocot and dicot lineages. The complete sequence datasets used for phylogenetic reconstruction are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of IMPα proteins in soybean, Arabidopsis, and maize. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using full-length IMPα protein sequences. Species abbreviations are as follows: At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Gm, Glycine max; and Zm, Zea mays. Distinct phylogenetic groups are highlighted in different colors to illustrate evolutionary divergence among the three species.

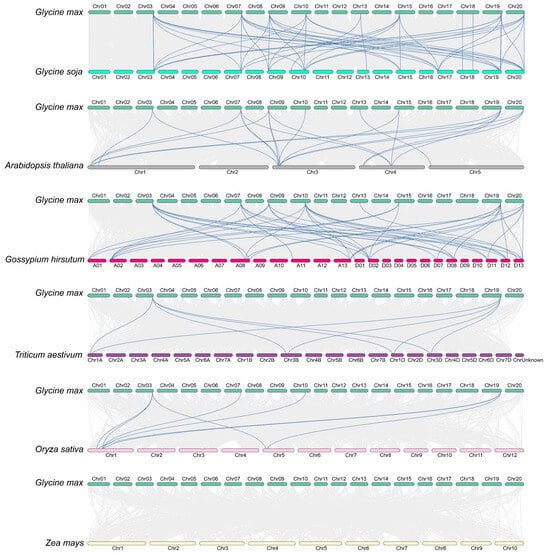

To further clarify the evolutionary relationships within the GmIMPα gene family, we conducted comparative synteny analyses between soybean and six representative plant species: wild soybean, Arabidopsis, cotton, wheat, rice, and maize (Figure 5). The analyses identified the following numbers of syntenic gene pairs between soybean GmIMPα genes and each species: 49 with wild soybean, 21 with Arabidopsis, 43 with cotton, 8 with wheat, 8 with rice, and none with maize. Notably, the largest number of syntenic pairs was observed between soybean and wild soybean, reflecting their close evolutionary relationship. Among the soybean genes, GmIMPα1 and GmIMPα2 showed syntenic connections with homologs in wild soybean, Arabidopsis, cotton, wheat, and rice, strongly suggesting that these genes are highly conserved and play fundamental roles in plant evolution. Moreover, the number of syntenic pairs between soybean and eudicot species was substantially higher than that with monocot species, underscoring a closer evolutionary relationship between GmIMPα genes and those of Arabidopsis. This conclusion is further supported by phylogenetic tree analysis. Collectively, these findings provide new insights into the evolutionary history of the GmIMPα gene family in soybean and lay a foundation for future functional characterization of these genes.

Figure 5.

Comparative synteny analysis of IMPα genes across seven plant species. Syntenic relationships were analyzed among Glycine max (soybean), Glycine soja (wild soybean), Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), Gossypium hirsutum (cotton), Triticum aestivum (wheat), Oryza sativa (rice), and Zea mays (maize). Gray lines represent whole-genome syntenic blocks between chromosomes; blue lines specifically highlight collinear IMPα gene pairs.

3.5. Characterization of Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements in the GmIMPα Promoters

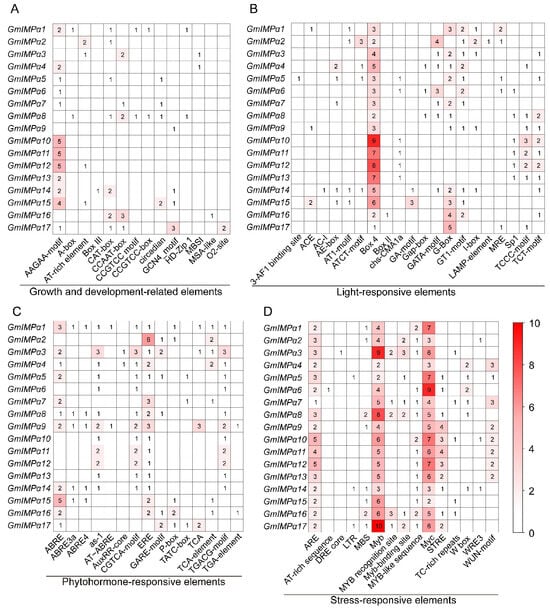

For promoter characterization, 2000 bp sequences upstream of the translation start codon (ATG) of all 17 GmIMPα genes were retrieved from the soybean genome. Cis-acting elements were predicted using the PlantCARE database and visualized with TBtools software (Figure 6). A total of 64 regulatory elements were identified and classified into four major functional categories: growth and development-related elements, light-responsive elements, hormone-responsive elements, and stress-responsive elements. Among these, light- and stress-responsive elements predominated. Within the growth and development-related group, 14 distinct elements were detected, including abundant AAGAA-motif, CAT-box, and CCAAT-box elements. Additionally, MYB binding sites potentially involved in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis were observed. Twenty distinct light-responsive elements were identified, such as Box 4, G-Box, GT1-motif, TCT-motif, TCCC-motif, and GATA-motif. Hormone-responsive elements encompassed six major categories: auxin-responsive (AuxRR-core, TGA-element), salicylic acid-responsive (as-1, TCA-element), gibberellin-responsive (GARE-motif, P-box, TATC-box), abscisic acid-responsive (ABRE, ABRE3a, ABRE4, AT~ABRE), ethylene-responsive (ERE), and methyl jasmonate-responsive elements (CGTCA-motif, TGACG-motif). Importantly, all GmIMPα promoters contained stress-responsive elements, including anaerobic induction-responsive elements (ARE), low-temperature stress-responsive elements (LTR), drought-inducible motifs (DRE core, MYB, MYC, MBS), and defense/stress-responsive elements (STRE, TC-rich repeat, W box, WRE3, WUN-motif). Collectively, these results indicate that the GmIMPα gene family is widely involved in mediating hormone signaling, stress responses, and the regulation of plant growth and development.

Figure 6.

Analysis of cis-acting elements in GmIMPα gene promoters. (A) Growth and development-related elements. (B) Light-responsive elements. (C) Phytohormone-responsive elements. (D) Stress-responsive elements. The bottom section displays the types of cis-acting elements. The numbers within the boxes represent the count of each type of element, and the color key on the right illustrates the correspondence between the number of elements and the color of the corresponding box.

3.6. GO Enrichment Analysis of the GmIMPα Family

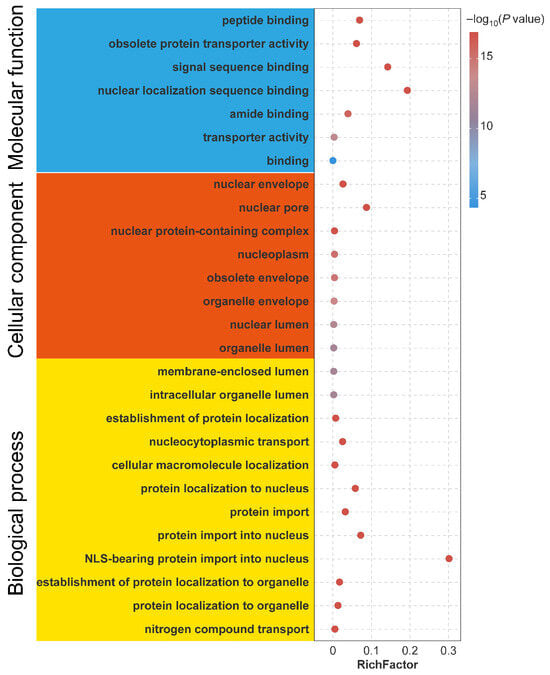

To gain functional insights into the GmIMPα gene family, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed (Figure 7). A total of 55 GO terms were identified, which were classified into three primary categories: Molecular Function (MF), Cellular Component (CC), and Biological Process (BP). The MF category included 7 GO terms, with enrichment in peptide binding (GO:0042277), obsolete protein transporter activity (GO:0008565), signal sequence binding (GO:0005048), and nuclear localization sequence binding (GO:0008139). The CC category comprised 23 GO terms, of which only the 8 major GO terms are shown in Figure 7. These terms are mainly associated with the nuclear envelope (GO:0005635), nuclear pore (GO:0005643), nuclear protein-containing complex (GO:0140513), and nucleoplasm (GO:0005654). The BP category contained 25 GO terms, of which only the 12 major GO terms are shown in Figure 7. These terms are significantly represented in processes such as establishment of protein localization (GO:0045184), nucleocytoplasmic transport (GO:0006913), cellular macromolecule localization (GO:0070727), protein localization to the nucleus (GO:0034504), and protein import into the nucleus (GO:0006606). Together, these findings highlight the central role of GmIMPα family members in nuclear import signal receptor activity, nuclear localization sequence (NLS) binding, and the transport of NLS-bearing proteins into the nucleus.

Figure 7.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the GmIMPα gene family. The vertical axis represents functional categories of the GO, while the horizontal axis displays the rich factor. The dots indicate −log10 (p value). Entries with blue backgrounds denote molecular function terms, orange-red backgrounds represent cellular component terms, and yellow backgrounds correspond to biological processes.

3.7. GmIMPα Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis

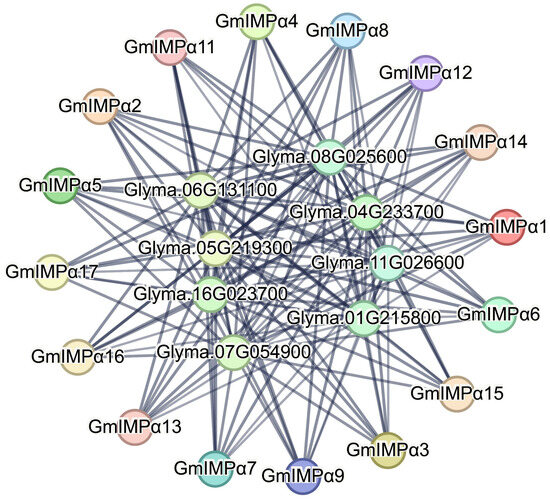

In living systems, proteins typically function within intricate protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks that mediate essential biological processes and physiological activities. To explore potential interactions of the GmIMPα family, we predicted PPIs among all 17 soybean GmIMPα proteins using the STRING database (Figure 8). The analysis revealed that the primary interactors were importin N-terminal domain-containing proteins (e.g., Glyma.04G233700, Glyma.05G219300, Glyma.06G131100, Glyma.07G054900, Glyma.08G025600, Glyma.16G023700), which share biological functions with GmIMPα proteins, particularly nuclear import. In addition, GmIMPα proteins were found to interact with RanBD1 domain-containing proteins (e.g., Glyma.04G233700, Glyma.05G219300), which are mainly involved in intracellular transport, mRNA trafficking, and protein translocation. These findings are consistent with established mechanisms whereby importin-α regulates nuclear import of NLS-bearing cargo proteins through interactions with importin N-terminal domains.

Figure 8.

Protein–protein interaction network analysis of GmIMPα proteins. The network was constructed using the STRING database. Proteins are represented as nodes, and interactions as edges. Gray edges denote direct interactions with GmIMPα proteins. Edge thickness reflects interaction confidence scores (>0.4), with thicker lines representing stronger experimental or functional evidence.

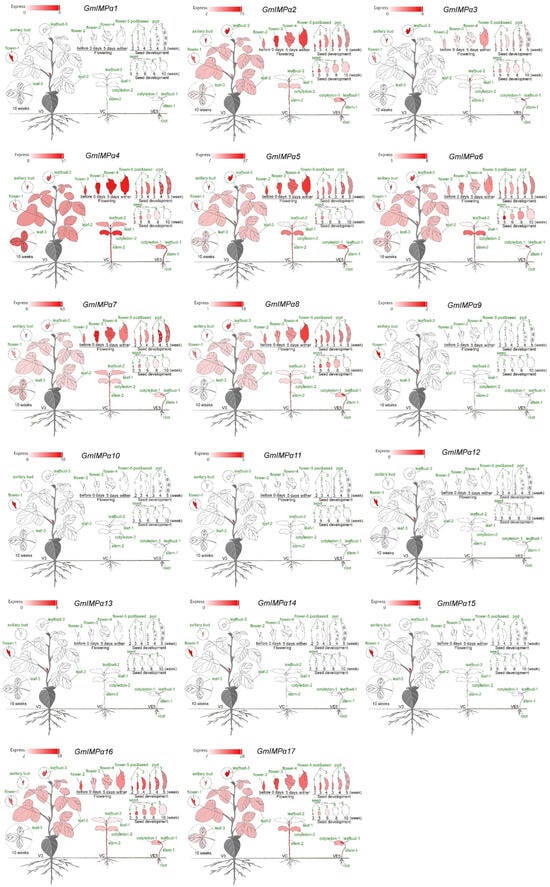

3.8. Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of GmIMPα Genes

To investigate the biological functions of GmIMPα genes, we analyzed their transcript levels across 28 soybean tissues using RNA-seq data available in the SoyOmics platform (Figure 9). All 17 GmIMPα genes exhibited detectable expression in at least one tissue, and distinct expression patterns were observed. For instance, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα7, and GmIMPα17 were highly expressed in cotyledons; GmIMPα2, GmIMPα4, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα8, GmIMPα16, and GmIMPα17 showed high transcript levels in the hypocotyl. Specific subsets of genes exhibited strong expression in other tissues, including nine genes in the shoot apex, four in the simple leaf, four in the trifoliate leaf, seven in the flower, six in the pod, seven in the seed, eight in the axillary bud, and seven in the root. Remarkably, GmIMPα1, GmIMPα9, GmIMPα10, GmIMPα11, GmIMPα12, GmIMPα13, GmIMPα14, and GmIMPα15 displayed flower-specific expression, with nearly undetectable transcript levels in other tissues, strongly suggesting their potential involvement in flower development. GmIMPα genes exhibit tissue-specific expression and likely play roles in various developmental processes at different stages of soybean growth.

Figure 9.

Differential expression of GmIMPα genes across 28 soybean tissues Expression patterns across various tissues, including leaves, roots, stems, pods, and flowers, were visualized using Electronic Fluorescent Pictographs (eFP) generated via SoyOmics.

3.9. Expression Analysis of GmIMPα Genes Under Abiotic Stress

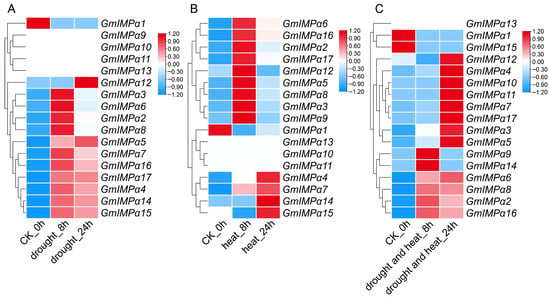

To investigate the responsiveness of the GmIMPα gene family to abiotic and hormonal stimuli, we performed a comprehensive expression analysis under drought, heat, low temperature, salt, and hormone treatments (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Overall, GmIMPα genes exhibited diverse and dynamic expression profiles depending on the stress conditions and treatment duration. Under drought stress in leaves (Figure 10A), GmIMPα2, GmIMPα3, GmIMPα6, and GmIMPα8 were strongly induced after 8 h, whereas GmIMPα12 reached its peak expression at 24 h. Notably, GmIMPα5 exhibited continuous induction throughout the drought treatment in leaves, suggesting a pivotal role in drought tolerance. In contrast, GmIMPα9, GmIMPα10, GmIMPα11, and GmIMPα13 remained transcriptionally silent under both control and drought conditions. Under heat stress in leaves (Figure 10B), nine genes (GmIMPα2, GmIMPα3, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα6, GmIMPα8, GmIMPα9, GmIMPα12, GmIMPα16, and GmIMPα17) were transiently induced, reaching peak expression at 8 h before subsequently declining. In contrast, GmIMPα4, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα14, and GmIMPα15 displayed sustained induction in leaves, implicating them in long-term heat response. Interestingly, GmIMPα16 showed an early upregulation followed by a gradual decline in leaves under drought, heat, and combined drought–heat treatments. Under combined drought–heat stress in leaves (Figure 10C), GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα17 maintained constitutively high expression, suggesting a potential role in conferring broad-spectrum stress tolerance. Collectively, these results indicate that while certain GmIMPα members exhibit stress-specific induction in leaves, others display broad responsiveness across multiple stress conditions, highlighting functional diversification within the gene family.

Figure 10.

Heatmap of GmIMPα gene expression in leaves at 0 h, 8 h, and 24 h under various stress conditions. (A) Expression profile under drought stress in leaves. (B) Expression profile under heat stress in leaves. (C) Expression profile under combined drought and heat stress in leaves.

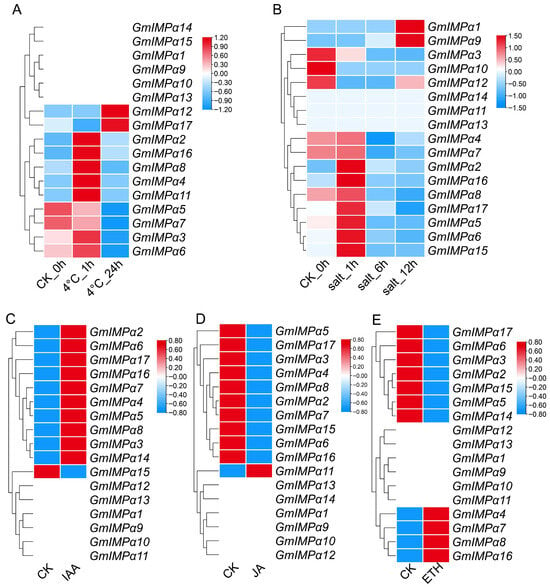

Figure 11.

Expression dynamics of GmIMPα genes under abiotic and hormone treatments, illustrating both early transient responses and sustained induction. (A) Expression profiles in leaves subjected to low-temperature stress at 0, 1, and 24 h. (B) Expression patterns in roots under salt stress at 0, 1, 6, and 12 h. (C) Expression profiles in roots following indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) treatment. (D) Expression profiles in roots following jasmonic acid (JA) treatment. (E) Expression profiles in roots following ethylene (ETH) treatment.

Responses to low temperature, salt, and hormone treatments further highlighted functional diversification within the GmIMPα family (Figure 11). After 1 h of cold treatment in leaves, GmIMPα2, GmIMPα4, GmIMPα6, GmIMPα8, and GmIMPα16 were rapidly induced, indicating their involvement in early cold response (Figure 11A). Conversely, GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα7 were continuously repressed, whereas GmIMPα12 and GmIMPα17 exhibited persistent induction. Under salt stress in roots (Figure 11B), GmIMPα2, GmIMPα4, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα6, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα8, GmIMPα16, and GmIMPα17 were transiently upregulated within 1 h but subsequently declined, while GmIMPα3 showed consistent downregulation. Notably, GmIMPα13 and GmIMPα14 remained weakly expressed under both cold and salt conditions in roots, suggesting limited involvement in these pathways. Hormone treatments produced distinct expression responses. Under IAA treatment in roots (Figure 11C), nine genes (GmIMPα2–8, GmIMPα16, and GmIMPα17) were upregulated. In contrast, JA treatment generally suppressed expression in roots (Figure 11D), although GmIMPα4, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα8, and GmIMPα16 were induced, highlighting a gene-specific divergence in JA responsiveness. ETH treatment in roots enhanced the expression of GmIMPα2, GmIMPα3, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα6, and GmIMPα17, but repressed GmIMPα4, GmIMPα7, GmIMPα8, and GmIMPα16 (Figure 11E).

4. Discussion

The nucleocytoplasmic transport system is a central mechanism in plants for maintaining cellular homeostasis and regulating gene expression, with the IMPα gene family playing a critical role in recognizing NLSs and mediating nuclear import [20]. This transport pathway serves as a pivotal regulatory hub linking environmental cues to nuclear gene expression, thereby enabling rapid transcriptional reprogramming under stress. With the advancement of high-throughput sequencing technologies and functional genomics, increasing numbers of IMPα genes have been identified in crops such as Arabidopsis, maize, rice, tomato, and wheat [29,32,33,43,59]. Soybean, as one of the most important oilseed and protein crops worldwide, is often challenged by multiple stresses, including salinity, drought, low temperature, and pathogen invasion [4,6]. However, systematic identification and functional characterization of the soybean IMPα gene family are still lacking. In this study, we identified 17 IMPα genes in the soybean genome, a number significantly higher than the nine found in Arabidopsis and the seven in maize [29,36]. This notable expansion is likely related to two whole-genome duplication (WGD) events during soybean’s evolutionary history, which substantially increased gene copy numbers [9]. Such expansion provides the structural and evolutionary basis for functional diversification of nuclear import adaptors in soybean.

Pan-genome analysis revealed that the 17 GmIMPα genes could be categorized into four groups: core genes, soft core genes, dispensable genes, and private genes (Figure 1), reflecting marked variation and dynamics across different soybean germplasms. For example, GmIMPα11 was present in only two cultivars, while GmIMPα12 was exclusive to a single germplasm. This classification system provides a solid theoretical framework for exploring the functional conservation, divergence, and evolutionary drivers of soybean IMPα genes. The 17 GmIMPα genes are unevenly distributed across 10 chromosomes (Table 1, Figure 3), with a strong concentration on chromosome 18 (five genes) and chromosome 19 (three genes), suggesting the existence of evolutionary hotspots. Previous studies have shown that many IMPα genes act as nuclear import receptors that recognize NLSs and mediate transport between the cytoplasm and nucleus [25]. For example, the tomato gene SlIMPA3 is primarily localized to the nucleus, with weak cytoplasmic distribution [33]. Consistently, our subcellular localization predictions indicated that all GmIMPα genes are targeted to either the cytoplasm or the nucleus (Table 1), supporting their potential role as nuclear transport proteins in cargo protein import. These results together imply that nuclear import mechanisms are evolutionarily conserved but may have acquired specialized regulatory properties in soybean. Gene exon–intron structures and conserved protein domains are key determinants of molecular function and functional diversity. Our results revealed that the 17 GmIMPα genes can be divided into three subgroups, with members within the same clade sharing clade-specific structural and motif characteristics, thus supporting the phylogeny-based classification. Most GmIMPα genes contain 10 exons; however, the GmIMPα6 protein exhibits notable motif losses, suggesting possible functional diversification within the family. Such motif variations may alter cargo recognition capacity or binding affinity to IMPβ, potentially leading to distinct transport efficiencies for specific stress-related transcription factors.

The IMPα gene family is widely distributed across eukaryotes and is evolutionarily highly conserved [24,25]. Phylogenetic analyses based on Arabidopsis, maize, and rice (Figure 4) revealed that soybean GmIMPα genes and their homologs in these species clustered into three main clades. Interestingly, soybean IMPα homologs tended to group closely with those of Arabidopsis, implying that functional conservation may be stronger among dicot species. Further synteny analysis across seven species demonstrated that cultivated soybean shares the closest evolutionary relationship with wild soybean, with the highest number of orthologous gene pairs, highlighting the strong evolutionary conservation of this family. Moreover, synteny between soybean and other dicots was stronger than with monocots, suggesting possible lineage-specific functional divergence during evolution. Gene duplication events, as a major driving force of gene family expansion, facilitate adaptation to diverse environmental conditions [60,61]. Our results indicated that the expansion of the GmIMPα gene family was mainly driven by 14 segmental duplication events (Figure 3, Table 2). Selection pressure analysis showed that most gene pairs are under strong purifying selection, maintaining functional stability. However, the GmIMPα1/GmIMPα14 gene pair exhibited a Ka/Ks ratio greater than 1, suggesting that it may have undergone positive selection and acquired novel functions. Such selective divergence likely underpins neofunctionalization processes that fine-tune nuclear import in response to environmental stress. This observation is consistent with previous findings in maize IMPα genes, indicating that expansion of this family involves not only gene redundancy but also functional innovation [29]. These results enhance our understanding of genomic dynamics and evolutionary relationships among soybean and other plant species, offering new insights into the genetic background and evolutionary history of soybean.

As crucial molecular switches, cis-acting regulatory elements fine-tune plant physiological processes and environmental adaptation under stress by regulating the expression of tissue-specific and stress-responsive genes [62]. Our analysis revealed that GmIMPα promoters are enriched in numerous hormone-responsive elements, particularly those responsive to salicylic acid, abscisic acid, and ethylene. In Arabidopsis, AtIMPα6 interacts with auxin-related proteins to regulate root development [31]. Ethylene, as a key signaling molecule, can enhance plant salt tolerance by regulating reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis [63]. The widespread presence of ethylene-responsive elements in the promoters of GmIMPα genes suggests their potential role in integrating ethylene signaling networks to regulate adaptive stress response pathways. Previous studies have also shown that plant resistance genes activate salicylic acid–mediated early immune responses to achieve atypical resistance, indicating that GmIMPα genes may participate in SA-mediated disease resistance [40]. Additionally, cis-elements responsive to cold, drought, anaerobic stress, and defense, as well as light and growth-related elements, were identified in some GmIMPα promoters, further underscoring their integrative roles in hormone signaling, stress responses, and growth regulation. These regulatory profiles point to a complex transcriptional network in which GmIMPα genes may act as downstream effectors of hormone and stress signaling cascades, linking external stimuli to the nuclear transport machinery. Transcriptomic data further revealed that GmIMPα genes exhibit broad yet differential expression profiles across tissues (Figure 11). For example, GmIMPα1/9/10/11/12/13/14/15 were exclusively expressed in flowers, indicating their involvement in reproductive development. In contrast, GmIMPα5, GmIMPα7, and GmIMPα17 exhibited high expression levels in roots and cotyledons, suggesting roles in environmental sensing and nutrient uptake. In Arabidopsis, IMPα1 and IMPα2 regulate cell wall-related gene expression, thereby enhancing salinity tolerance [37]. Expression profiling of soybean IMPα genes under abiotic stresses (Figure 10, 11) showed that GmIMPα2/3/6/8 were strongly upregulated after 8 h of drought treatment. GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα12 peaked after 24 h of drought but were downregulated after 24 h of heat treatment, suggesting divergent regulatory roles in drought versus heat stress responses. Furthermore, GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα7 were consistently downregulated under cold stress, while GmIMPα2/5/6/8/15/16/17 were rapidly induced within 1 h of salt stress, highlighting the functional diversity of the GmIMPα family in stress responses. This dynamic expression behavior indicates that different GmIMPα members may specialize in transporting transcription factors or regulatory proteins specific to each stress type, thereby fine-tuning stress signal transduction through selective nuclear import.

In conclusion, IMPα genes play indispensable roles in regulating plant growth, development, immunity, and stress adaptation. Given the current limited understanding of GmIMPα gene functions in soybean, integrating molecular genetics with transgenic approaches is essential to elucidate their regulatory mechanisms and functional diversity under stress conditions. Such insights will not only deepen our knowledge of plant stress adaptation mechanisms but also provide valuable theoretical and practical strategies for enhancing stress resistance and advancing molecular breeding in soybean.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we systematically identified 17 IMPα genes in soybean, a number significantly greater than that reported in Arabidopsis and maize. Pan-genome analysis categorized these genes into four groups—core, soft core, dispensable, and private—indicating substantial genetic variation among different soybean germplasms. The GmIMPα genes were unevenly distributed across 10 chromosomes, with pronounced clusters on chromosomes 18 and 19, suggesting that these regions may hold particular evolutionary significance. Phylogenetic and structural analyses demonstrated that, while GmIMPα genes are broadly conserved, subgroup-specific structural features and motif variations point to potential functional diversification. Notably, the GmIMPα1/GmIMPα14 gene pair showed evidence of positive selection, implying the acquisition of novel functions. Promoter analysis revealed enrichment of hormone- and stress-responsive elements, and subcellular localization predictions supported their roles in nucleocytoplasmic transport. Transcriptome data further showed that GmIMPα genes exhibit tissue-specific and stress-inducible expression. Several members, including GmIMPα5 and GmIMPα7, were markedly upregulated under drought, heat, and salt stresses, indicating diverse regulatory roles in stress responses. Collectively, this study provides a comprehensive view of the structural characteristics, phylogeny, and expression diversity of the GmIMPα gene family, offering theoretical foundations and genetic resources for elucidating stress resistance mechanisms and guiding soybean genetic improvement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112603/s1, Table S1: Versions of 27 soybean genome sequences and annotation files, each representing diverse cultivars and lines of Glycine max. Table S2: IMPα protein sequences from Glycine max, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Zea mays. Table S3: Orthologous relationships between Glycine max and six other plant species.

Author Contributions

Z.-Q.Z.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing—original draft. M.-M.L.: Data curation, Resources, Writing—original draft. G.L.: Data curation, Resources, Writing—original draft. X.C.: Data curation, Resources, Writing—original draft. R.-M.T.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing—original draft. Z.-W.W.: Software, Writing—original draft. K.-L.L.: Data curation, Writing—original draft. L.-H.L.: Data curation, Writing—original draft. L.L.: Data curation, Writing—original draft. N.-N.L.: Data curation, Writing—original draft. L.W.: Investigation, Writing—original draft. K.-H.J.: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. Y.-Y.Y.: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2025LZGC009, 2024TZXD052, 2023LZGC001, and 2022LZGC022), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of SAAS (CXGC2023F13, CXGC2025B02, CXGC2025H21), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province for Young Scholars (ZR2023QC153), and the earmarked fund for Shandong Agriculture Research System (SDARS-05).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Requests for additional data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all reviewers for their valuable insights during the manuscript review process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Graham, P.H.; Vance, C.P. Legumes: Importance and Constraints to Greater Use. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; Ren, H.; Sun, R.; Wei, Z.; Hong, H.; Luan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Soybean genetic resources contributing to sustainable protein production. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4095–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Tayade, R.; Kang, B.-H.; Hahn, B.-S.; Ha, B.-K.; Kim, Y.-H. Genome-Wide Association Studies of Seven Root Traits in Soybean (Glycine max L.) Landraces. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Sonah, H.; Patil, G.; Chen, W.; Prince, S.; Mutava, R.; Vuong, T.; Valliyodan, B.; Nguyen, H.T. Integrating omic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitham, S.A.; Qi, M.; Innes, R.W.; Ma, W.; Lopes-Caitar, V.; Hewezi, T. Molecular Soybean-Pathogen Interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2016, 54, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Borja Reis, A.F.; Moro Rosso, L.; Purcell, L.C.; Naeve, S.; Casteel, S.N.; Kovács, P.; Archontoulis, S.; Davidson, D.; Ciampitti, I.A. Environmental Factors Associated with Nitrogen Fixation Prediction in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 675410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakkoli, E.; Rengasamy, P.; McDonald, G.K. High concentrations of Na+ and Cl− ions in soil solution have simultaneous detrimental effects on growth of faba bean under salinity stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 4449–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammadov, J.; Buyyarapu, R.; Guttikonda, S.K.; Parliament, K.; Abdurakhmonov, I.Y.; Kumpatla, S.P. Wild Relatives of Maize, Rice, Cotton, and Soybean: Treasure Troves for Tolerance to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmutz, J.; Cannon, S.B.; Schlueter, J.; Ma, J.; Mitros, T.; Nelson, W.; Hyten, D.L.; Song, Q.; Thelen, J.J.; Cheng, J.; et al. Genome Sequence of the Palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 2010, 463, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-S.; Vuong, T.D.; Qiu, D.; Robbins, R.T.; Grover Shannon, J.; Li, Z.; Nguyen, H.T. Advancements in breeding, genetics, and genomics for resistance to three nematode species in soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 2295–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hossain, M.S.; Lyu, Z.; Schmutz, J.; Stacey, G.; Xu, D.; Joshi, T. SoyCSN: Soybean context-specific network analysis and prediction based on tissue-specific transcriptome data. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, I.; Richards, E.J.; Evans, D.E. Cell Biology of the Plant Nucleus. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M. Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.B.; Görlich, D. Transport Selectivity of Nuclear Pores, Phase Separation, and Membraneless Organelles. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K. Nuclear pore complex-mediated gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Res. 2020, 133, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, C.E.; Fung, H.Y.J.; Chook, Y.M. Karyopherin-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, M.E.; Plafker, K.; Smith, A.E.; Clurman, B.E.; Macara, I.G. Npap60/Nup50 Is a Tri-Stable Switch That Stimulates Importin-Alpha: Beta-Mediated Nuclear Protein Import. Cell 2002, 110, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Masi, R.D.; Lintermann, R.; Wirthmueller, L. Nuclear Import of Arabidopsis Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 2 Is Mediated by Importin-α and a Nuclear Localization Sequence Located Between the Predicted SAP Domains. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, E.; Uy, M.; Leighton, L.; Blobel, G.; Kuriyan, J. Crystallographic Analysis of the Recognition of a Nuclear Localization Signal by the Nuclear Import Factor Karyopherin α. Cell 1998, 94, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, A.; Mills, R.E.; Lange, C.J.; Stewart, M.; Devine, S.E.; Corbett, A.H. Classical Nuclear Localization Signals: Definition, Function, and Interaction with Importin α. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 5101–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfori, M.; Mynott, A.; Ellis, J.J.; Mehdi, A.M.; Saunders, N.F.W.; Curmi, P.M.; Forwood, J.K.; Bodén, M.; Kobe, B. Molecular basis for specificity of nuclear import and prediction of nuclear localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 1562–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Choi, H.I.; Kim, J.W.; Yun, J.-H.; Lee, Y.H.; Jeon, E.J.; Kwon, K.K.; Cho, D.-H.; Choi, D.-Y.; Park, S.-B.; et al. Cas9-mediated gene-editing frequency in microalgae is doubled by harnessing the interaction between importin α and phytopathogenic NLSs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2415072122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lee, L.-Y.; Oltmanns, H.; Cao, H.; Veena; Cuperus, J.; Gelvin, S.B. IMPa-4, an Arabidopsis Importin α Isoform, Is Preferentially Involved in Agrobacterium-Mediated Plant Transformation. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2661–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Yamada, K.; Yoneda, Y. Importin α: A key molecule in nuclear transport and non-transport functions. J. Biochem. 2016, 160, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, M.; Yoneda, Y. Importin α: Functions as a nuclear transport factor and beyond. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2018, 94, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimoto, C.; Moriyama, T.; Tsujii, A.; Igarashi, Y.; Obuse, C.; Miyamoto, Y.; Oka, M.; Yoneda, Y. Functional characterization of importin α8 as a classical nuclear localization signal receptor. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 2676–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helizon, H.; Rösler-Dalton, J.; Gasch, P.; von Horsten, S.; Essen, L.-O.; Zeidler, M. Arabidopsis phytochrome A nuclear translocation is mediated by a far-red elongated hypocotyl 1-importin complex. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 96, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P.J.; Mosqueda, N.; Brownlee, C.W. Palmitoylated Importin α Regulates Mitotic Spindle Orientation through Interaction with NuMA. EMBO Rep. 2025, 26, 3280–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, G.; Yang, G.; Dong, J. Identification of the Karyopherin Superfamily in Maize and Its Functional Cues in Plant Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Lerma-Reyes, R.; Mukherjee, T.; Nguyen, H.V.; Weber, A.L.; Cummings, E.E.; Schulze, W.X.; Comer, J.R.; Schrick, K. Nuclear localization of Arabidopsis HD-Zip IV transcription factor GLABRA2 is driven by importin α. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 6441–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herud, O.; Weijers, D.; Lau, S.; Jürgens, G. Auxin responsiveness of the MONOPTEROS-BODENLOS module in primary root initiation critically depends on the nuclear import kinetics of the Aux/IAA inhibitor BODENLOS. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2016, 85, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Panda, B.B.; Sekhar, S.; Kariali, E.; Mohapatra, P.K.; Shaw, B.P. Comparative proteomics of the superior and inferior spikelets at the early grain filling stage in rice cultivars contrast for panicle compactness and ethylene evolution. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 202, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Peng, X.-J.; Liu, N.-N.; Lu, Z.-X.; Zhao, Y.-Q.; Yao, G.-F.; Li, J.; Xu, R.-F.; Hu, K.-D.; Zhang, H. An Importin Protein SlIMPA3 Interacts with SlLCD1 and Regulates Tomato Fruit Ripening. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1492–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, M.R.M.; Cardoso, F.F.; Kobe, B. Transport of DNA repair proteins to the cell nucleus by the classical nuclear importin pathway—A structural overview. DNA Repair 2025, 149, 103828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.; Lüdke, D.; Klenke, M.; Quathamer, A.; Valerius, O.; Braus, G.H.; Wiermer, M. The truncated NLR protein TIR-NBS13 is a MOS6/IMPORTIN-α3 interaction partner required for plant immunity. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 92, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdke, D.; Roth, C.; Kamrad, S.A.; Messerschmidt, J.; Hartken, D.; Appel, J.; Hörnich, B.F.; Yan, Q.; Kusch, S.; Klenke, M.; et al. Functional requirement of the Arabidopsis importin-α Nuclear transport receptor family in autoimmunity mediated by the NLR protein SNC1. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2021, 105, 994–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Yang, C.; Zhao, L.; Qin, G.; Peng, L.; Zheng, Q.; Nie, W.; Song, C.-P.; Shi, H.; et al. SWO1 modulates cell wall integrity under salt stress by interacting with importin α in Arabidopsis. Stress Biol. 2021, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parween, D.; Sahu, B.B. An Arabidopsis nonhost resistance gene, IMPORTIN ALPHA 2 provides immunity against rice sheath blight pathogen, Rhizoctonia solani. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. An importin alpha homolog, MOS6, plays an important role in plant innate immunity. Curr. Biol. CB 2005, 15, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, T.; Gaudin, V.; Matsuura, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Tamura, K. The importin α proteins IMPA1, IMPA2, and IMPA4 play redundant roles in suppressing autoimmunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2025, 121, e17203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ding, F.; Zhang, L.; Sheng, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Y. The importin α subunit PsIMPA1 mediates the oxidative stress response and is required for the pathogenicity of Phytophthora sojae. Fungal Genet. Biol. FG B 2015, 82, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ge, P.; Ma, Y.; Lin, F.; Jing, D.; Zhou, T.; Cui, F. Loss-of-Function of Two PD-Associated Proteins Confers Resistance to Rice Stripe Virus. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 26, e70121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; Kang, G.; Liu, Y.; You, L.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Wang, D.; et al. Appropriate reduction of importin-α gene expression enhances yellow dwarf disease resistance in common Wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Shen, Y.; Tian, D.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Ni, L.; Zhang, Z.; Song, S.; et al. SoyOmics: A deeply integrated database on soybean multi-omics. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, M.; Andreeva, A.; Florentino, L.C.; Chuguransky, S.R.; Grego, T.; Hobbs, E.; Pinto, B.L.; Orr, A.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Ponamareva, I.; et al. InterPro: The protein sequence classification resource in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D444–D456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Gonzales, N.R.; Gwadz, M.; Lu, S.; Marchler, G.H.; Song, J.S.; Thanki, N.; Yamashita, R.A.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Shannon, L.M.; Samac, D.A. A stepwise guide for pangenome development in crop plants: An alfalfa (Medicago sativa) case study. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-C.; Shen, H.-B. Cell-PLoc: A package of Web servers for predicting subcellular localization of proteins in various organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: Calculating Selective Pressure on Coding and Non-coding Sequences. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodstein, D.M.; Shu, S.; Howson, R.; Neupane, R.; Hayes, R.D.; Fazo, J.; Mitros, T.; Dirks, W.; Hellsten, U.; Putnam, N.; et al. Phytozome: A comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D1178–D1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Silva, F.; Pedrosa-Silva, F.; Venancio, T.M. The Soybean Expression Atlas v2: A comprehensive database of over 5000 rna-seq samples. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 116, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Gao, Y.; Gong, W.; Laux, T.; Li, S.; Xiong, F. A tripartite transcriptional module regulates protoderm specification during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 2038–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.-H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallemand, T.; Leduc, M.; Landès, C.; Rizzon, C.; Lerat, E. An Overview of Duplicated Gene Detection Methods: Why the Duplication Mechanism Has to Be Accounted for in Their Choice. Genes 2020, 11, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinnen, G.; Goossens, A.; Pauwels, L. Lessons from Domestication: Targeting Cis-Regulatory Elements for Crop Improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Smith, J.A.C.; Harberd, N.P.; Jiang, C. The regulatory roles of ethylene and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant salt stress responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 91, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).