Abstract

Olive cultivation constitutes a fundamental Mediterranean rural activity in Greece, as it primarily accounts for the country’s substantial socio-economic development. Although the olive tree is one of the best acclimated species, its overall performance may be significantly impacted by changes in the climate. Thus, by considering the lack of scientific research on the climate suitability evaluation of olive groves over the entire Greek territory, a study between the geomorphological parameter mapping of Greece (altitude, aspect, slope, and terrain roughness) and the respective required atmospheric conditions for the olive crop’s growth (temperature, precipitation, and frost days) was performed. Every parameter is reclassified to translate its value into a score, and the final suitability map is the outcome of the aggregation of all score maps. Individually, the overall suitability for olive cultivation is high in Greece, given its extensive area, resulting in a high score (8–10); geomorphological and climatic conditions (34.44% and 59.40%, respectively); and overall suitability conditions (42.00%) for olive cultivation. Over the identified olive grove areas, the model gives a high score (8–10) for 91.59% of the cases. The model may be characterized by its simplicity, usability, flexibility, and efficiency. The current modelling procedure may serve as a means for identifying suitable areas for the sustainable and productive development of olive cultivation.

1. Introduction

Most olive cultivation (97.9%) occurs in Mediterranean countries, with Greece ranking fifth after Spain, Italy, Turkey, and Tunisia. It has one of the highest olive oil consumption rates per capita, according to the International Olive Council [1] (data as of 2024). The olive tree, Olea europaea L., named after the Greek word ‘elea,’ covers over 2 million acres in Greece, with approximately 130 million trees, accounting for 25% of the country’s farms and contributing to 70% of global production, alongside Spain and Italy [2,3,4]. Greece produces 300,000–400,000 tons of olive oil annually, with 80% of it being extra-virgin [5]. Olives are crucial for Greece’s socio-economic growth, ecology, and human health, with olive oil playing a key role in the Mediterranean diet due to its protective effects against cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, cognitive decline, and metabolic syndrome [6,7,8,9,10]. Olive cultivation is closely tied to the Mediterranean climate between 30° and 45° latitude, marked by hot, dry summers; mild, humid winters; and high solar radiation, which supports regular fruit production [11,12,13].

Greece is included in the Northern Hemisphere’s temperate continental climate zone [14]. Thus, the country’s climate conditions correspond to the typical Mediterranean features, mainly characterized by relatively warm and dry summers, mild rainy winters, and extensive sunshine throughout the annual period. The average annual temperature may exceed 20 °C or be less than 8 °C in certain mountainous areas of the northern parts. The average precipitation may reach approximately 300 mm per year in the Cyclades Islands, while it can amount to 2000 mm per year in the mountainous regions (e.g., the Pindos Mountain). Even with Greece’s relatively small surface area, its topography and surrounding seas create a noteworthy climatic variety. The climate’s suitability for olive cultivation extends across most of the country, thereby supporting the continued expansion of olive growing into new areas [15].

Several scientific studies and literature reviews focus on the latest research achievements in modelling olive cultivation to monitor crop behavior as affected by climatic conditions. Modelling of the olive crop involves the analysis of climatic and topographical conditions (utilizing GIS in conjunction with climatic variables) to characterize olive-growing areas [15]. Updated modelling and Decision Support Systems (DSSs) have been developed upon the open-source Geospatial Cyberinfrastructure (GCI) platform (namely, GeOlive), which provides a significant web-based operational tool that better connects olive productivity and environmental sustainability by processing static and dynamic data (e.g., pedology and daily climate) to perform simulation modelling via the Web [16,17]. The random forest algorithm has been exploited for the identification of suitable areas for olive cultivation based on the resulting suitability maps by taking into account pedoclimatic parameters (e.g., average annual temperature, average annual precipitation, solar radiation, slope, aspect, land use capability class, land use capability sub-class, soil depth, other soil properties, and land cover) [16]. Process-oriented simulation models (e.g., OliveCan) have been conceived for investigating the influence of environmental conditions and management applications on water relations, and the growth and productivity of the olive under different irrigation strategies [18,19], enabling, thus, the comprehension of the olive orchard’s productive dynamics as impacted by heterogeneous agricultural practices and climatic conditions [18], but also under different climate change scenarios [20]. The simulation of the effects of climate change and varying planting densities on the potential olive growth and olive oil production has also been performed using the three-dimensional modeling of canopy photosynthesis, respiration, and the dynamic distribution of assimilates among organs [21]. Dynamic modeling has been implemented for the forecasting of the expected olive flowering under natural temperature conditions [22]. Agro-hydrological models (e.g., the FAO-56 model) have been utilized for simulating the transpiration fluxes of table olive groves under soil water deficit conditions [23] and for evaluating the crop water use and crop coefficient (e.g., the SIMDualKc model) in irrigated olive groves [24,25]. Simple process-based model (including the phenological sub-model) simulations of the biomass accumulation and yield of olive groves have been conducted, interpreting the competition between ecosystem components, including olive tree growth and grass cover, for water [26].

Climate-crop models are essential tools for investigating the impacts of atmospheric parameters on crop development, growth, and potential production, combining the scientific knowledge of crop physiology with changing environmental conditions [27,28]. According to the aforementioned survey, several simulation models involving olive groves have been formulated so far in olive-oil-producing areas for various purposes. However, there is a lack of investigations corresponding to the climate suitability evaluation of specific cultivations in individual regions of Greece and even more so across the entire Greek territory. The most important role of a climatic modeling tool may be to establish a better scientific connection between atmospheric conditions and the development of olive groves. Having such a model could help project the spatial shifting of olive groves and the local pressures on the crop due to climate change. Moreover, the presented results can be an essential tool for agricultural policy, strategies, and practices for stakeholders.

Research-wise, the main goal of this investigation is to map the suitability of olive cultivation in Greece for the objective of predicting changes in the latter due to alterations in atmospheric conditions. This is the first step in a continuous process of modeling climate for olive groves using data from a climate reference period. The next step is to apply the model to climate projection data to map the future evolution of olive groves in Greece and elsewhere. Therefore, for the realization of this purpose, a conjunction between the geomorphological data of Greece and the required atmospheric conditions for the specific crop’s cultivation has been accomplished.

2. Materials and Methods

The study area is Greece (38.85° N 24.4° E), located in the southern part of the Balkan area, with a total surface of 131.957 km2. Nearly 80% of this area is continental, while 20% is divided among ~3.000 islands.

A digital elevation model (DEM) with a spatial resolution of 250 m was used to generate the necessary data for assessing the area’s suitability. From this dataset, spatial operations were performed to initiate digital data relative to the geomorphological indicators of aspect, slope, terrain roughness, and elevation (above sea level).

The Corine Land Cover (CLC) dataset [29] for the year 2018 (time extent 2017–2018) was exploited to compare the present study’s olive cultivation suitability results with established olive cultivation locations. Since the olive groves are perennial, the relocation of olive trees is scarce and rare for such small time period.

From a climatic perspective (1970–2000), data from the WorldClim [30] and ERA5-Land [31] datasets (for identifying the frost days) were exploited. WorldClim data provides a monthly temporal resolution, while ERA5-Land, which was utilized in this study, offers an initial hourly resolution. This allowed us to determine specific times when air temperatures fell below 0 °C, indicating the occurrence of frost. Days meeting this criterion were classified as frost days, and the annual number of frost days at each pixel was subsequently aggregated. We used the 30s version of the WorldClim dataset, which has a spatial resolution of 1 km, while the standard resolution of ERA5-Land is approximately 9 km. To align the resolutions between these two datasets, we made the necessary adjustments without altering the parameter values through interpolation. The spatial operations were conducted for the generation of digital data involving the climatic indicators of temperature (mean minimum values from November to March, mean January values (as a measure of the necessary cool temperatures), mean July values, and mean annual values), precipitation (annual precipitation), and frost days (annual number of frost days, and Spring frost days). Thus, a total of 11 parameters were utilized for the construction of the model. We selected this time period to establish a baseline for mapping the suitability of olive tree cultivation using our model. This interval represents a recent climatic era derived from observational data rather than projections, making it the most relevant and complete reference available. Consequently, it serves as a dataset benchmark for evaluating the performance and results of our model.

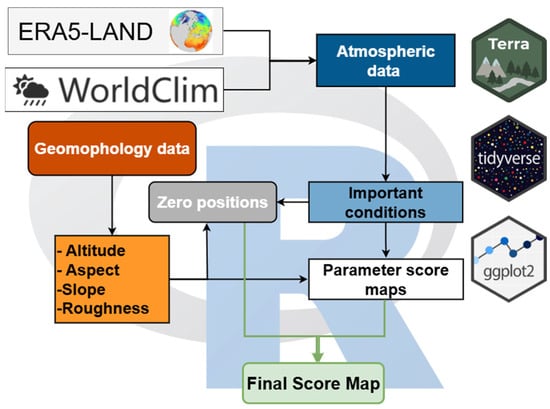

The generalized method’s flowchart is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The method’s flowchart.

The applied method for the construction of the suitability model is as follows:

- Each parameter is assigned a score ranging from 1 to 10. The score 1 is assigned to acceptable conditions of the parameter in relation to olive tree cultivation, and score 10 is assigned to the optimal conditions of this parameter. We can also assign a score of 0 where this parameter is unsuitable for cultivation. Therefore, in case the conditions are unsuitable for olive groves, the score is zero (0), and, when they are suitable for this cultivation, the score can range from 1 (the lower suitability) to 10 (the higher suitability). Suppose a model’s parameter score is 0 at a site. In that case, that site remains unsuitable, regardless of the scores of the other parameters. The score tables can be found in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S11).

- The geomorphological parameters, after classification into suitability scores (Figures S2–S5), have been summed to create a final geomorphological score raster. This raster has been linearly normalized to obtain a score from 1 to 10 for suitable sites. If one parameter receives a score of zero (0), this value remains in the final geomorphological map.

- The climatic parameter rasters have been classified according to the related score tables (Tables S5–S11) and mapped. After this step, the climatic score rasters have been summed up to a final climatic score raster. This raster has been linearly normalized to range from 1 for the less suitable areas to 10 for the optimal areas in terms of climatic conditions, and has been mapped accordingly. In cases where a climatic parameter does not allow olive cultivation, the final raster has been set to zero.

- Finally, the geomorphology raster score and the climatic raster score have been added to a final suitability score raster. Geomorphology accounts for 20% of the final score, while climate accounts for the remaining 80% in this version of the model. This proportion stems from the empirical observation of the olive tree’s ability to thrive in a variety of geomorphological settings. The final score map has been linearly normalized to have scores from 1 to 10 for the suitable areas and 0 for unsuitable areas.

To further clarify the data processing method, the low-temperature raster and its score map represent the minimum monthly mean air temperature between November and March at a given location. The annual precipitation raster and its score map come from the sum of annual precipitation in mm. The rest of the parameters are what their names declare.

All the above have been implemented using R language v. 4.4.2. [32]. Therefore, we utilized packages (libraries) such as dplyr v. 1.1.4 [33], terra v. 1.8-60 [34], ggplot2 v. 3.5.2 [35], and sf v. 1-21 [36] for the utilization, management, analysis, and visualization of the overall applied geomorphological and climatic data, as they constitute an appropriate tool for exploiting large volumes of data and creating maps and visualizations. Finally, comprehensive maps illustrating the optimal distribution/scoring of olive cultivation from a climatic and geomorphological perspective, as well as the conjunction of both elements, are presented over the entire area without further intervention.

3. Results and Discussion

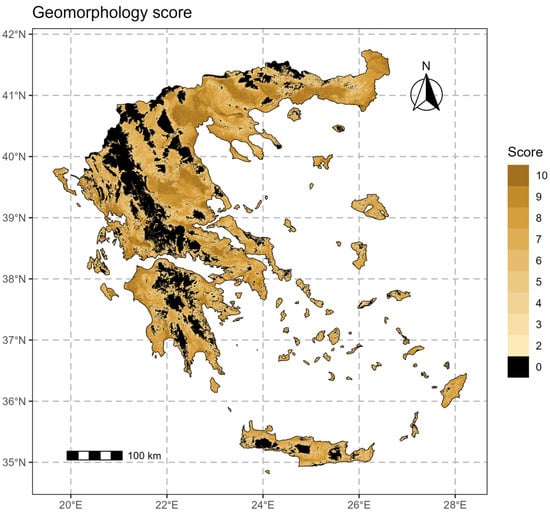

The resulting map of olive’s geomorphological suitability over Greece is shown in Figure 2. The presented color scale represents the geomorphological suitability scores, ranging from 0 (unsuitable areas) to 10 (suitable areas). The geomorphological suitability of each point on the map is determined by combining the results obtained from each of the parameters (Elevation, Aspect, Slope, and Terrain Roughness) for each point, as mentioned in the Materials and Methods section.

Figure 2.

Geomorphology score map.

As illustrated in Figure 2, many points correspond to the optimal suitability scores for olive cultivation. Overall, the geomorphology of Greece can be characterized as ideal for olive cultivation, except in its mountainous areas (black-colored mountainous points with a zero score), where most geomorphological parameters correspond to the lowest scores. The olive tree grows best in northeastern and central Greece, much of the Peloponnisos, many islands, and some western regions.

The overall surface coverage of each geomorphological suitability score over Greece is presented in Table 1. It is evident that, although a significant distribution of ~24% results in unsuitability (score 0), a large part of the country is suitable (41.44% relative to scores 2 to 7). In comparison, a pretty extensive area appears with the most optimal geomorphological conditions for olive cultivation (34.44% corresponding to scores 8 to 10).

Table 1.

The percentage of Greece’s surface covered by each geomorphological suitability score.

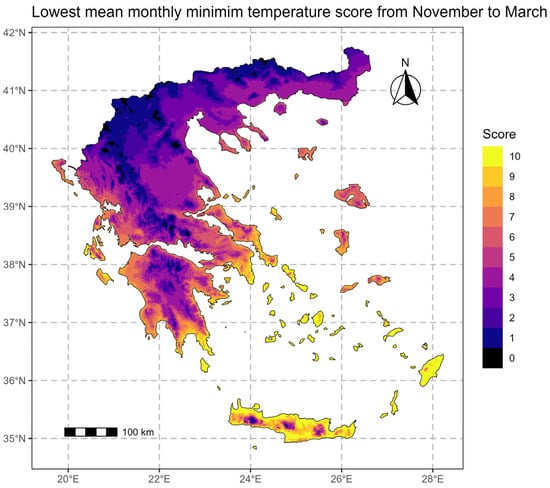

In Figure 3, we present the score of the spatial distribution of the lowest mean monthly minimum temperature over Greece (Table S5) for the months of November to March. Over most of the country, the area provides relatively suitable low-temperature conditions for olive groves, except for the mountainous terrain characterized by a 0 score. More suitable conditions gradually result southwards, with low temperature scores exceeding 7 (corresponding to low temperature values of 5 °C or lower from November to March; Table S5). These areas are primarily located near the sea, encompassing the country’s central eastern to central western regions, and substantial portions of the Peloponnisos, as well as the Ionian and Aegean Islands (Figure S6). Most of the latter have received a maximum score of 10.

Figure 3.

Low temperature score map (lowest mean monthly minimum temperature from November to March).

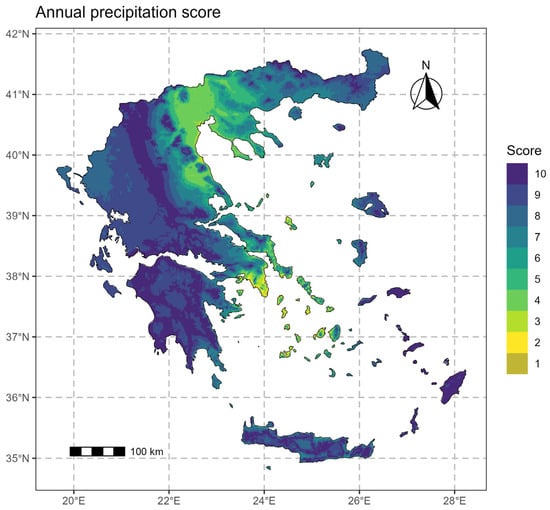

The annual precipitation score map is illustrated in Figure 4. According to the scoring map (Table S6), it appears that optimal precipitation conditions are formed over almost the entire Greek peninsula, with high scores between 7 and 10 (precipitation amount of 500–800 mm; Table S6). Less suitable areas are primarily in the north and east of the country, including some Aegean islands. This is due to the olive tree’s low water requirements.

Figure 4.

Annual precipitation score map.

For the January mean air temperature, optimum scores over 5 (exceeding 8 °C; Table S7) are demonstrated in a significant part of mainland Greece (Figure 5) except for approximately the whole of the country’s islands, where scores of 1 to 4 are dominant. Prohibitive conditions (0 score) are primarily found in relatively restricted areas, mainly in the upland regions of northern and central Greece.

Figure 5.

January mean temperature score map.

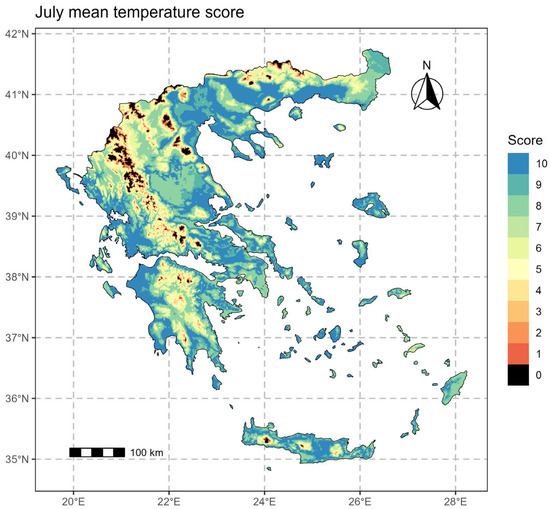

The domination of the optimal July mean temperature conditions is illustrated in Figure 6, given the extensive occurrence of scores 5 to 10 (respectively, 19–30 °C; Table S8). Relatively unsuitable temperature regimes (scores of above 32 or below 16.5 °C), along with the prohibitive 0 score, result in majorly over-dispersed mountainous terrains (north, central continental Greece, Peloponnisos, and Crete).

Figure 6.

July mean temperature score map.

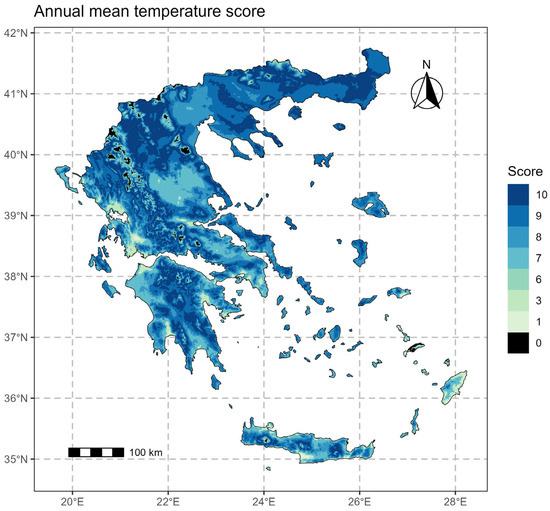

The mapping of the annual mean air temperature scores (Figure 7) reflects good to optimal conditions (8 to 10) for olive cultivation across the entire country (Table S9). The less suitable and prohibitive conditions (scores of below 3 and 0, respectively) result in limited areas in the western central regions and restricted uplands in the northern areas and the Aegean islands.

Figure 7.

Annual mean temperature score map.

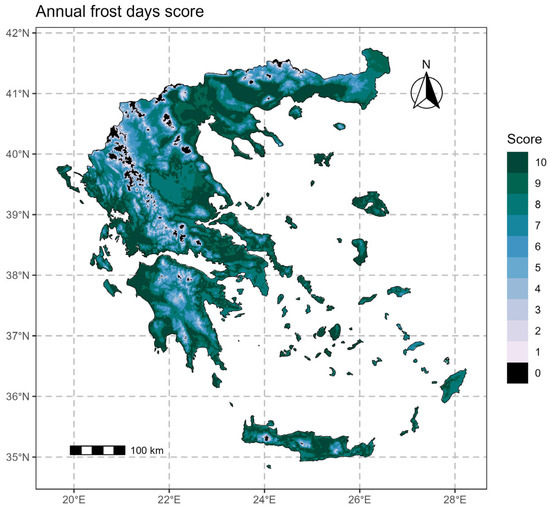

According to the annual frost days map (Figure 8), most satisfactory to optimal scores of 7 to 10 (corresponding to 0 to 20 frost days annually; Table S10) characterize substantial parts of the investigated area. Higher numbers of frost days (20 to 100) occur mainly for upland Greece. In contrast, the restricted number of more than 100 days (score 0; Table S10) corresponds to the mountainous terrain of considerable parts of continental Greece.

Figure 8.

Annual frost days score map.

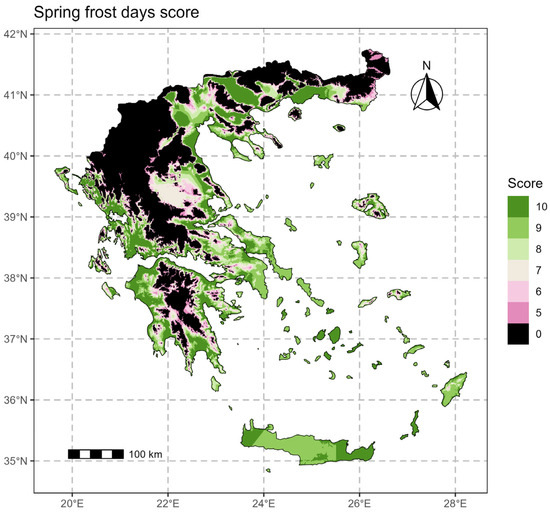

As exhibited in Figure 9, spring frost exceeding 5 days in duration (0 score; Table S11) is unsuitable over a considerably extensive area. Scattered parts of the northern, central, eastern, and western mainland, around the Peloponnese, and most of the islands are excluded, given their more optimal environment for olive cultivation, with scores of 8 to 10 (2 to 0 days; Table S11).

Figure 9.

Spring frost days score map.

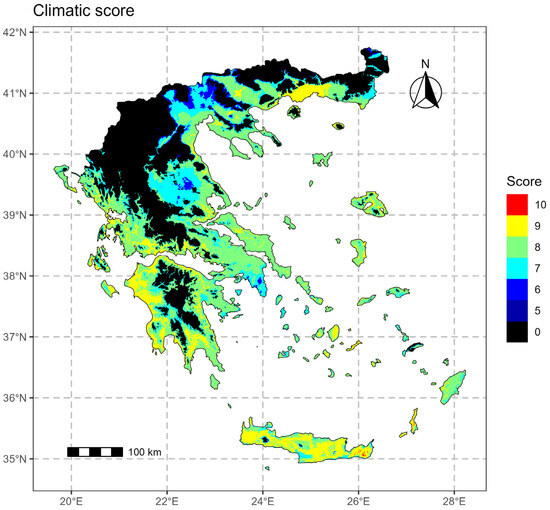

The overall score of each point of the resulting final climate suitability map is shown in Figure 10. The mapping is obtained by adding up the individual scores of each point in the individual maps on all climatological indicators, and maps of temperature parameters (mean minimum values from November to March, mean January values, mean July values, and mean annual values) and of frost days (annual number of frost days, and Spring frost days) (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 10.

Climatic score map.

As demonstrated (Figure 10), a substantial part of Greece is rated 0, pinpointing, thus, many parts of the country as climatically unsuitable for olive cultivation. These parts include most areas of northeastern and central Greece, as well as central Peloponnese, especially in the continental and mountainous regions. The same situation occurs in the Attica region and in minor parts of various islands, where the 0 score may be attributed to either low rainfall or high temperatures, or to a combination of both. However, many areas in central and southern Greece are well-suited for olive groves, and, in contrast, several others in which, although not corresponding to ideal conditions, the cultivation may be developed.

The overall surface coverage of each climatic suitability score over Greece is presented in Table 2. It is demonstrated that a significant coverage of 36.29% corresponds to a score of 0, highlighting unsuitable conditions for olive cultivation. However, more extensive areas covering 59.4% of the country’s surface result in scores of 8 to 10. In more detail, we observe the highest score (10) in the eastern part of Crete, as well as on the islands of Karpathos, Amorgos, and Naxos. The red sparse pixels indicate the optimum areas considering only the atmospheric conditions. The major extended areas with a score of 9 (in yellow) are the wider part of Crete, the western and southern parts of Peloponnisos, and a wide and uniform part of the coastal area of Thrace (northern Greece). In the areas mentioned above, we found areas scoring 8 for atmospheric conditions.

Table 2.

The percentage of Greece’s surface covered by each climatic suitability score.

There are no areas with scores ranging from 1 to 5. This situation may arise when one parameter for a particular site receives a low score. At the same time, another parameter is assigned a value of zero. For example, a site with a high-altitude score might simultaneously receive a score of zero for the frost parameter. This indicates the need to recalibrate the model in future updates to ensure a more balanced distribution of scores.

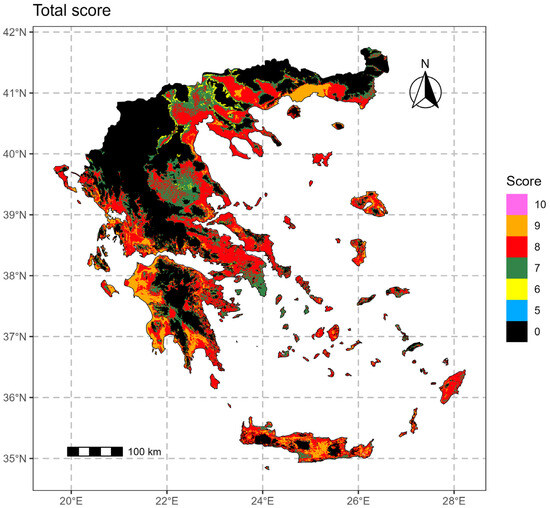

The final suitability map for olive cultivation in Greece combines the overall geomorphological and climatic score maps (Figure 2 and Figure 10, respectively) and is demonstrated in Figure 11. Each point’s final score was calculated by adding its geomorphological and climatic map scores, unless any were deemed unsuitable on either map. The resulting suitability map uses a color scale to show overall scores from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest); zero indicates no suitability.

Figure 11.

Total suitability score map.

According to the resulting final suitability map (Figure 11), a significant part of the country is deemed unsuitable for olive cultivation (score 0). The prevailing climate and mountainous terrain make much of Greece—especially the north, center, and upland areas—unsuitable. More suitable regions are found further south. Although the combination of both climatic and geomorphological parameters may form a prohibitive environment (score of 0) for olive cultivation in a significant part of the investigated area, it is demonstrated that good and high scores are found in several places across the country. Greece has largely favorable conditions for olive cultivation, which explains the extensive presence of olive farming. These findings are based solely on climate and geomorphology, excluding factors like irrigation, soil quality, labor costs, and pest risks.

Since there are no spatial olive grove productivity data available in Greece, we cannot directly evaluate our model. However, to test the accuracy of the presented model and mapping, we utilize the CLC dataset, which identifies several land cover classes across the European territory [29]. This dataset offers details regarding the presence of land cover, specifically olive groves. However, it does not include metrics on tree productivity or related aspects. However, it serves as a dependable evaluation for the model presented. Since the existence of an olive grove is not the result of local suitability only, we cannot examine the false positive error [37]. In some areas where conditions are suitable for olive trees, farmers may opt to grow different crops due to financial yield considerations. This practice is common within Greek agriculture. Olive trees are typically planted where soil fertility or irrigation does not support other higher-yield crops.

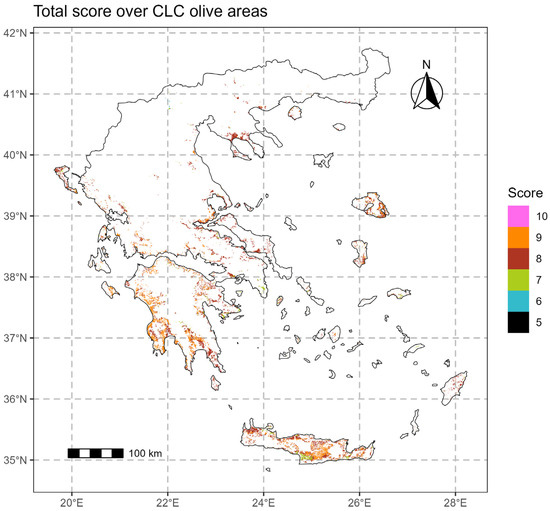

We can analyze the false negative errors produced by our model. In this context, a false negative occurs when an actual location with olive trees is incorrectly classified by the model as restricted (with a zero value). Therefore, Figure 12 presents the score over the existing olive groves according to CLC, and Table 3 presents the percentage of Greece’s surface covered by each total suitability score resulting from the model and the respective surface covered by olive groves. The model’s high value coincides with the identified olive cultivation areas according to the CLC. This is demonstrated, for example, by the resulting 32.23% total area with a suitability score of 8 and the identified olive grove area covering 58.53% of the country’s surface. We note that there are no zero scores over the identified olive areas, so we do not have false-positive errors. Moreover, we observe that, over existing olive areas (CLC), we have scored 6 and higher, which is a strong indication of the model’s reliability. On the other hand, we have low surface coverage (%) by score 10 over existing olive groves. This result indicates a need for the recalibration of the model in future versions, particularly if additional productivity or other qualitative and quantitative data become available.

Figure 12.

The total score over the olive areas according to CLC.

Table 3.

The percentage per total suitability score over the Greece area and over the identified olive groves’ positions by CLC.

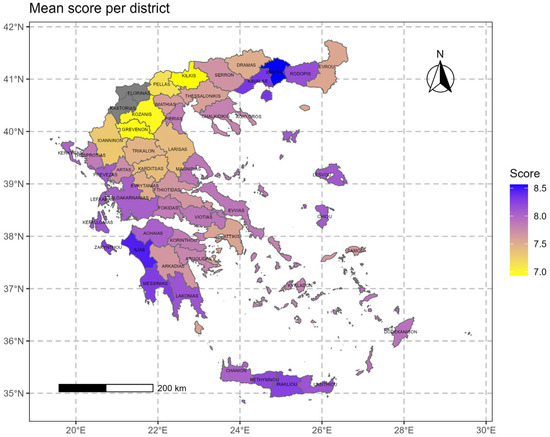

To clarify and enhance the usefulness of these results for policymakers and stakeholders, the mean score per Greece’s district is illustrated in Figure 13. The spatial mean suitability score was calculated, excluding zero values representing unsuitable sites. Higher mean scores are observed in the Xanthis (8.6) and Ilias (8.5) districts, followed by the Messinias, Zakynthou, Irakliou, and Kavalas districts (each at 8.3), as shown in Table S12 of the Supplementary Materials. This calculation covers all areas within each district except locations with zero values. The two grey-colored districts in northern Greece (Florinas and Kastorias) do not display suitability for olive tree cultivation.

Figure 13.

Mean suitability score per district (grey areas indicate absence of suitability).

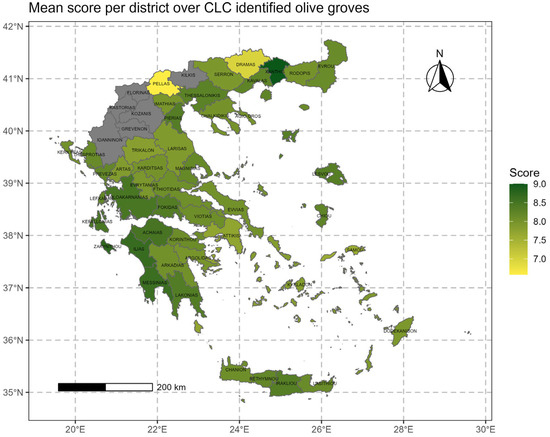

Figure 14 shows the mean suitability score per Greece’s district for sites identified as olive groves by the CLC dataset, with related statistics in Table S13. The Xanthis district has the highest mean score (9.0), followed by the Zakynthou and Ilias districts (8.7). Table S13 ranks Greece’s western, southern, and Crete districts as having high suitability scores. Overall, Figure 14 aligns with known patterns of olive tree productivity.

Figure 14.

Mean suitability score per district over olive groves according to CLC (grey areas indicate absence of suitability).

In Figure 14, we see some northern Greece districts that have grey colors. This indicates the absence of olive groves according to the CLC dataset. We must note that the spatial resolution of CLC is 100 m and the minimum mapping unit is 25 ha for real features (and 100 m width for linear features). Therefore, in the case of small and scattered olive groves, CLC is unable to identify them. It is evident that CLC underestimates the surface covered by olive trees.

Regrettably, there are currently no recent published studies on the climatic suitability for olive cultivation in Greece under present or near-present conditions, making it difficult to compare our findings with those reported in other studies. Accordingly, we reference the principal findings of recent studies concerning the suitability of olive cultivation across Europe to provide readers with a more comprehensive perspective on the subject. In their study, Khan and Verma [38] compiled the global geographic occurrence data of a wild olive (Olea europaea subsp. cuspidate) to project its potential distribution in current and future climate scenarios. By utilizing ensemble modeling, they predicted a significant decrease in habitat suitability, particularly in regions such as the coastal areas of Spain, France, Italy, and Greece. Guise et al. [39] employed a spatially explicit Ecological Niche Modelling approach to project environmental suitability for olive growing throughout the Iberian Peninsula under two distinct climate change scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathway RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5) within the 2050 time horizon. The authors documented the alteration of the spatial distribution patterns of environmentally suitable areas, along with the threatened ability of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) regions to retain their current distinctive environmental conditions. By exploiting Species Distribution Models (SDMs), Arenas-Castro et al. [40] have forecasted the reduction in the environmentally suitable areas for olive cultivation and, therefore, of the olive production in Andalusia (Southern Spain). By combining high-resolution GIS data with Papadakis’ agro-climate classification, Montsant et al. [41] have demonstrated that, in the 2031–2050 climate RCP4.5 scenario, over 15% of Catalonia (Northeastern Spain) will no longer be adequate for non-irrigated olive, at locations in which it has been traditionally a rainfed crop. Bordoni et al. [42] aimed to reconstruct different scenarios of environmental suitability for olive trees under current and future climatic scenarios, considering a marginal area (Oltrepò Pavese, South Lombardy, Northern Italy) that is not yet developed for olive cultivation. By applying a data-driven method based on predictors representative of the main geological, geomorphological, climatic, and plant cover variables, future projections at different periods (by the years 2050, 2070, and 2100) have demonstrated the expansion of the suitable areas for olive groves. The increased suitability was justified by the projected temperature increase and the number of frost days’ decrease, especially in sectors located at higher latitudes and altitudes. By constructing and exploiting simple and reliable equation modelling, Charalampopoulos et al. [43] have calculated and projected the olive GDDs (Growing Degree Days) over the Balkans. The time and latitude were most influential among input parameters (time, altitude, distance from seashore, and latitude). The projections revealed a vast sprawl of olive cultivation areas (23.9% by 2040 and 20.3% by 2060) towards the northern parts of the examined area. Under the scope of sustainable development, Tsiaras and Domakinis [44] have aimed at the selection of suitable olive tree crop cultivation sites in mountainous, favored areas. Climatic, topographic, pedological, and geological data layers were processed using a simple set of rules and with the aid of GIS geo-processing routines to identify optimal sustainable cultivation sites in the Pierion Municipal Unit (Municipality of Katerini, Northern Greece).

The sustainability of traditional Mediterranean olive systems is under threat due to climate change issues, primarily associated with future increases in temperature, reductions in rainfall [45,46], and the occurrence of more frequent and extreme weather events, which pose some of the problems that farmers will have to cope with in the upcoming decades. These impacts may potentially endanger the sustainability of traditional olive orchards in southern Europe, which are already barely economically viable under current environmental conditions [47]. This perspective highlights the need for the accurate identification and effective implementation of adaptation measures to climate change. For implementing immediate actions, the acquisition and processing of extensive knowledge related to olive cultivation are fundamental, as they will empower sustainable quantitative and qualitative production [48]. However, the present model relies on historical climate data from the closest to present conditions (1970–2000), which may not accurately represent present or future climatic conditions.

For example, precision agriculture technologies can be leveraged to support agricultural decision-makers and monitor complications related to various aspects of olive cultivation management. Such actions may involve the application of efficient irrigation management strategies and the adoption of precision irrigation technologies, establishing, thus, sustainable and resource-efficient olive cultivation [49,50]. Other adaptation strategies may involve implementing soil and cover crop management techniques (e.g., no-till soil management, and seed-mix cover crops) [6]. The application of spray compounds is used for protection against extreme weather conditions. Additionally, critical long-term adaptation measures may include the selection of suitable cultivars, the implementation of effective breeding systems [40,45], and the relocation of olive orchards [51].

Future versions of the model may require recalibration. We can also incorporate climatic data based on projected scenarios to map shifts in suitability due to climate change. Adding parameters like soil conditions and irrigation will make the model more comprehensive. In a more advanced version of this model, embodied information and parameters related to pests and pathogens, along with other socioeconomic factors such as labor availability and road network condition, are considered. Releasing it as an R package v. 4.4.2. would facilitate the work of agricultural scientists and researchers.

4. Conclusions

The conclusions deduced from the present investigation can be summarized as follows:

- Individually, the overall geomorphological and climate suitability for olive cultivation is high in Greece.

- A quite extensive area (34.44% surface coverage) appears with very high score geomorphological conditions for olive cultivation.

- Large areas (59.4% surface coverage) result in very high climatic conditions for olive cultivation.

- The conjunction of geomorphological suitability and climatic suitability mapping highlights a substantial part of the country’s area (approximately 60%) that appears as a very high score for olive groves.

- Overall, the olive suitability model may be characterized as efficient.

- The observed differences between the model-derived final suitability map and the recorded olive-growing areas in Greece (CLC) may be justified by the application of limited climate and geomorphology components in the model.

- This document provides mapping data to help policymakers organize the agricultural sector. Information on location and suitability scores supports targeted measures for olive cultivation, helping to create informed sustainability plans in response to climate change.

- The current modeling procedure can serve as a tool for identifying suitable areas for the development of sustainable and productive olive cultivation.

- The model is characterized by simplicity, usability, and flexibility.

- Introducing environmental parameters impacted by future climate change into the model may create a new map of climatic suitability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15112604/s1, Figure S1. Koppen–Geiger climate classification of Greece; Figure S2. Altitude score map; Figure S3. Aspect score map; Figure S4. Slope score map; Figure S5. Roughness score map; Figure S6. Map of Greece, including regions names referred in the manuscript; Table S1. The altitude score; Table S2. The aspect score; Table S3. The slope score; Table S4. The roughness score; Table S5. The low temperature from November to March score; Table S6. The annual precipitation score; Table S7. January mean air temperature score; Table S8. The July mean air temperature score; Table S9. The annual mean air temperature score; Table S10. The annual frost days score; Table S11. The spring frost days score; Table S12. The mean suitability score per Greece district; and Table S13. The mean suitability score per district over olive groves according to CLC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.; methodology, I.C.; investigation, I.C. and A.M.; resources, F.D.; writing, F.D.; writing—materials and methods, I.C.; review and editing, I.C., F.D., A.M. and P.A.R.; visualization, I.C.; supervision, I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Olive Council World Market of Olive Oil and Table Olives—Data from December 2024. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/world-market-of-olive-oil-and-table-olives-data-from-december-2024/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Marakis, G.; Gaitis, F.; Mila, S.; Papadimitriou, D.; Tsigarida, E.; Mousia, Z.; Karpouza, A.; Magriplis, E.; Zampelas, A. Attitudes towards Olive Oil Usage, Domestic Storage, and Knowledge of Quality: A Consumers’ Survey in Greece. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelenos, G.; Kiritsakis, A. Olive Tree History and Evolution. In Olives and Olive Oil as Functional Foods; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-119-13534-0. [Google Scholar]

- den Herder, M.; Moreno, G.; Mosquera-Losada, R.M.; Palma, J.H.N.; Sidiropoulou, A.; Santiago Freijanes, J.J.; Crous-Duran, J.; Paulo, J.A.; Tomé, M.; Pantera, A.; et al. Current Extent and Stratification of Agroforestry in the European Union. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, M.; Morin, J.-F. FoodIntegrity Handbook: A Guide to Food Authenticity Issues and Analytical Solutions; Eurofins Analytics France: Nantes, France, 2018; ISBN 2-9566303-0-X. [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos, G.; Kasapi, K.A.; Koubouris, G.; Psarras, G.; Arampatzis, G.; Hatzigiannakis, E.; Kavvadias, V.; Xiloyannis, C.; Montanaro, G.; Malliaraki, S.; et al. Adaptation of Mediterranean Olive Groves to Climate Change through Sustainable Cultivation Practices. Climate 2020, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomou, A.D.; Sfougaris, A. Contribution of Agro-Environmental Factors to Yield and Plant Diversity of Olive Grove Ecosystems (Olea europaea L.) in the Mediterranean Landscape. Agronomy 2021, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foscolou, A.; Critselis, E.; Panagiotakos, D. Olive Oil Consumption and Human Health: A Narrative Review. Maturitas 2018, 118, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvaniti, O.S.; Rodias, E.; Terpou, A.; Afratis, N.; Athanasiou, G.; Zahariadis, T. Bactrocera Oleae Control and Smart Farming Technologies for Olive Orchards in the Context of Optimal Olive Oil Quality: A Review. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Carpena, M.; Lourenço-Lopes, C.; Gallardo-Gomez, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Bioactive Compounds and Quality of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, H.; Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Santos, J.A. Mediterranean Olive Orchards under Climate Change: A Review of Future Impacts and Adaptation Strategies. Agronomy 2021, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Trombi, G.; Ferrise, R.; Brandani, G.; Dibari, C.; Ammann, C.M.; Lippi, M.M.; Bindi, M. Olive Trees as Bio-Indicators of Climate Evolution in the Mediterranean Basin. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 818–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Giorgi, F.; Rohling, E.; Seager, R. Chapter 3—Mediterranean Climate: Past, Present and Future. In Oceanography of the Mediterranean Sea; Schroeder, K., Chiggiato, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 41–91. ISBN 978-0-12-823692-5. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N.J.; Dufour, A.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, X.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Miralles, D.G. High-Resolution (1 Km) Köppen-Geiger Maps for 1901–2099 Based on Constrained CMIP6 Projections. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubouris, G.; Psarras, G. Pedoclimatic and Landscape Conditions of Greek Olive Groves. In The Olive Landscapes of the Mediterranean: Key Challenges and Opportunities for Their Sustainability in the Early XXIst Century; Muñoz-Rojas, J., García-Ruiz, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 223–227. ISBN 978-3-031-57956-1. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, P.; Bonfante, A.; Colandrea, M.; Di Vaio, C.; Langella, G.; Marotta, L.; Mileti, F.A.; Minieri, L.; Terribile, F.; Vingiani, S.; et al. A Geospatial Decision Support System to Assist Olive Growing at the Landscape Scale. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorio, F.; Aguirado, C.; Paniagua, L.L.; García-Martín, A.; Rebollo, L.; Rebollo, F.J. Exploring the Climate and Topography of Olive Orchards in Extremadura, Southwestern Spain. Land 2024, 13, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bernal, Á.; Morales, A.; García-Tejera, O.; Testi, L.; Orgaz, F.; De Melo-Abreu, J.P.; Villalobos, F.J. OliveCan: A Process-Based Model of Development, Growth and Yield of Olive Orchards. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozalp, A.Y.; Akinci, H. Evaluation of Land Suitability for Olive (Olea europaea L.) Cultivation Using the Random Forest Algorithm. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairech, H.; López-Bernal, Á.; Moriondo, M.; Dibari, C.; Regni, L.; Proietti, P.; Villalobos, F.J.; Testi, L. Is New Olive Farming Sustainable? A Spatial Comparison of Productive and Environmental Performances between Traditional and New Olive Orchards with the Model OliveCan. Agric. Syst. 2020, 181, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Leffelaar, P.A.; Testi, L.; Orgaz, F.; Villalobos, F.J. A Dynamic Model of Potential Growth of Olive (Olea europaea L.) Orchards. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 74, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairech, H.; López-Bernal, Á.; Moriondo, M.; Dibari, C.; Regni, L.; Proietti, P.; Villalobos, F.J.; Testi, L. Sustainability of Olive Growing in the Mediterranean Area under Future Climate Scenarios: Exploring the Effects of Intensification and Deficit Irrigation. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 129, 126319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoly, I.; Elbaz, H.; Engelen, C.; Wechsler, T.; Elbaz, G.; Ben-Ari, G.; Samach, A.; Friedlander, T. A Model Estimating the Level of Floral Transition in Olive Trees Exposed to Warm Periods during Winter. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 1266–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Sirera, À.; Rallo, G.; Paredes, P.; Paço, T.A.; Minacapilli, M.; Provenzano, G.; Pereira, L.S. Transpiration and Water Use of an Irrigated Traditional Olive Grove with Sap-Flow Observations and the FAO56 Dual Crop Coefficient Approach. Water 2021, 13, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, G.; Baiamonte, G.; Juárez, J.M.; Provenzano, G. Improvement of FAO-56 Model to Estimate Transpiration Fluxes of Drought Tolerant Crops under Soil Water Deficit: Application for Olive Groves. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2014, 140, A4014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; Darouich, H.; Oliveira, A.R.; Farzamian, M.; Monteiro, T.; Castanheira, N.; Paz, A.; Gonçalves, M.C.; Pereira, L.S. Water Use and Soil Water Balance of Mediterranean Tree Crops Assessed with the SIMDualKc Model in Orchards of Southern Portugal. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 279, 108209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Ferrise, R.; Trombi, G.; Brilli, L.; Dibari, C.; Bindi, M. Modelling Olive Trees and Grapevines in a Changing Climate. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 72, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Leolini, L.; Brilli, L.; Dibari, C.; Tognetti, R.; Giovannelli, A.; Rapi, B.; Battista, P.; Caruso, G.; Gucci, R.; et al. A Simple Model Simulating Development and Growth of an Olive Grove. Eur. J. Agron. 2019, 105, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, G. CORINE Land Cover and Land Cover Change Products. In Land Use and Land Cover Mapping in Europe; Manakos, I., Braun, M., Eds.; Remote Sensing and Digital Image Processing; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-94-007-7968-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-Km Spatial Resolution Climate Surfaces for Global Land Areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A.; Albergel, C.; Arduini, G.; Balsamo, G.; Boussetta, S.; Choulga, M.; Harrigan, S.; Hersbach, H.; et al. ERA5-Land: A State-of-the-Art Global Reanalysis Dataset for Land Applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K. Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Hijmans, R.J.; Bivand, R.; Forner, K.; Ooms, J.; Pebesma, E.; Sumner, M.D. Terra: Spatial Data Analysis. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Pebesma, E. Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. R J. 2018, 10, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Callaway, E.S.; Boykoff, M.T.; Yohe, G.; Root, T.y.L. Awareness of Both Type 1 and 2 Errors in Climate Science and Assessment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2014, 95, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Verma, S. Ensemble Modeling to Predict the Impact of Future Climate Change on the Global Distribution of Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 977691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, I.; Silva, B.; Mestre, F.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Duarte, M.F.; Herrera, J.M. Climate Change Is Expected to Severely Impact Protected Designation of Origin Olive Growing Regions over the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. Syst. 2024, 220, 104108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Castro, S.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Moreno, M.; Villar, R. Projected Climate Changes Are Expected to Decrease the Suitability and Production of Olive Varieties in Southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montsant, A.; Baena, O.; Bernárdez, L.; Puig, J. Modelling the Impacts of Climate Change on Potential Cultivation Area and Water Deficit in Five Mediterranean Crops. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 19, e0301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, M.; Gambarani, A.; Giganti, M.; Vivaldi, V.; Rossi, G.; Bazzano, P.; Meisina, C. Present and Projected Suitability of Olive Trees in a Currently Marginal Territory in the Face of Climate Change: A Case Study from N-Italy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, I.; Polychroni, I.; Psomiadis, E.; Nastos, P. Spatiotemporal Estimation of the Olive and Vine Cultivations’ Growing Degree Days in the Balkans Region. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiaras, S.; Domakinis, C. Use of GIS in Selecting Suitable Tree Crop Cultivation Sites in Mountainous Less Favoured Areas: An Example from Greece. Forests 2023, 14, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.M.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Soriano, M.A.; Gabaldón-Leal, C.; Santos, C.; Lorite, I.J. Identifying Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change for Mediterranean Olive Orchards Using Impact Response Surfaces. Agric. Syst. 2020, 185, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorite, I.J.; Gabaldón-Leal, C.; Ruiz-Ramos, M.; Belaj, A.; de la Rosa, R.; León, L.; Santos, C. Evaluation of Olive Response and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change under Semi-Arid Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 204, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonizzato, A. The Socio-Economic Impacts of Organic and Conventional Olive Growing in Italy. New Medit 2020, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, E.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Fountas, S. Trends in Remote Sensing Technologies in Olive Cultivation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 3, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkavou, K.; Gemtou, M.; Fountas, S. Drivers and Barriers to the Adoption of Precision Irrigation Technologies in Olive and Cotton Farming—Lessons from Messenia and Thessaly Regions in Greece. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkotos, E.; Zotos, A.; Tsirogiannis, G.; Patakas, A. Prediction of Olive Tree Water Requirements under Limited Soil Water Availability, Based on Sap Flow Estimations. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropero, R.F.; Rumí, R.; Aguilera, P.A. Bayesian Networks for Evaluating Climate Change Influence in Olive Crops in Andalusia, Spain. Nat. Resour. Model. 2019, 32, e12169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).