Soil Physiochemical Property Variations and Microbial Community Response Patterns Under Continuous Cropping of Tree Peony

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Soil Sampling

2.1.1. Study Area

2.1.2. Experiment Setup and Soil Sampling

2.2. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties

2.2.1. Soil pH

2.2.2. Soil Organic Carbon and Macronutrient Contents

2.2.3. Available Metal or Micronutrient Contents

2.3. Soil DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physiochemical Properties

3.1.1. Soil pH

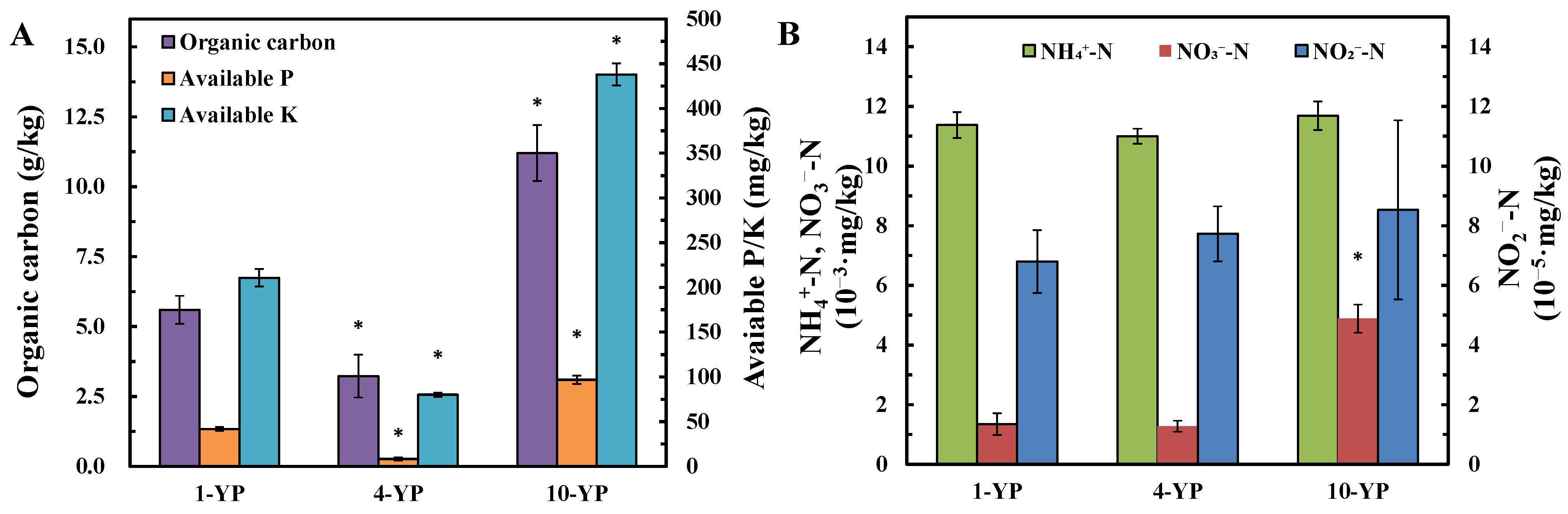

3.1.2. Soil Organic Carbon and Available P, K, and Inorganic N Contents

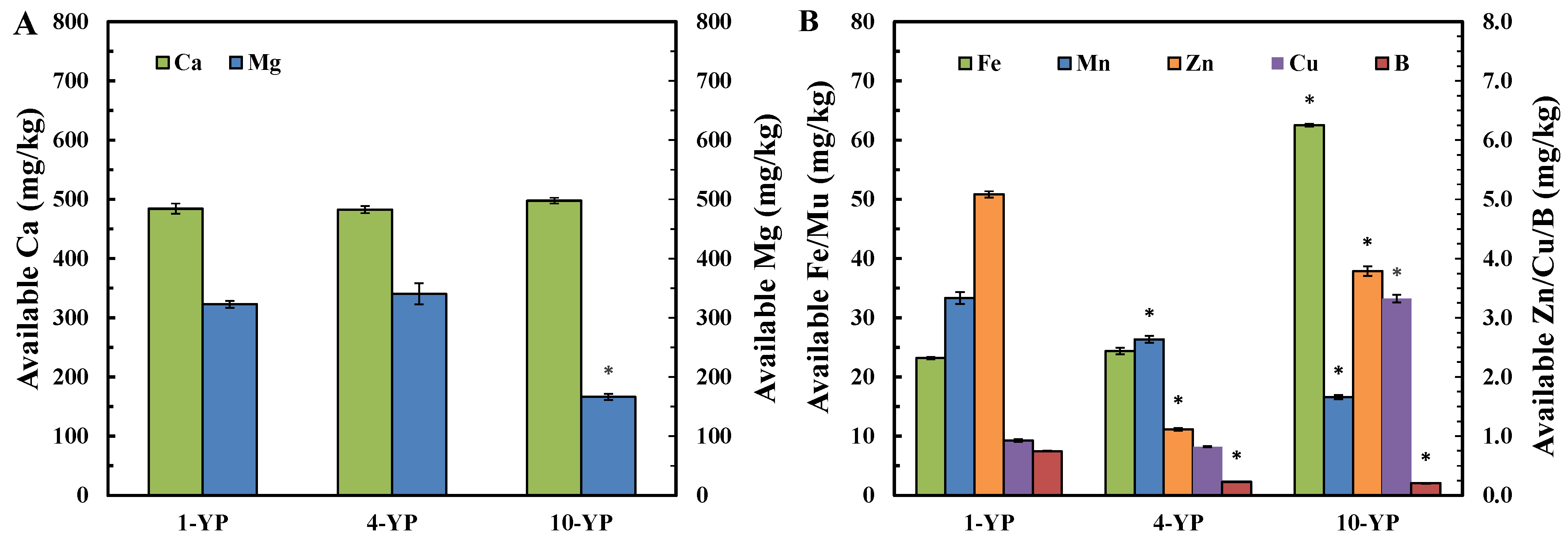

3.1.3. Available Micronutrient Contents

3.2. Microbial Community Structure and Composition Variations

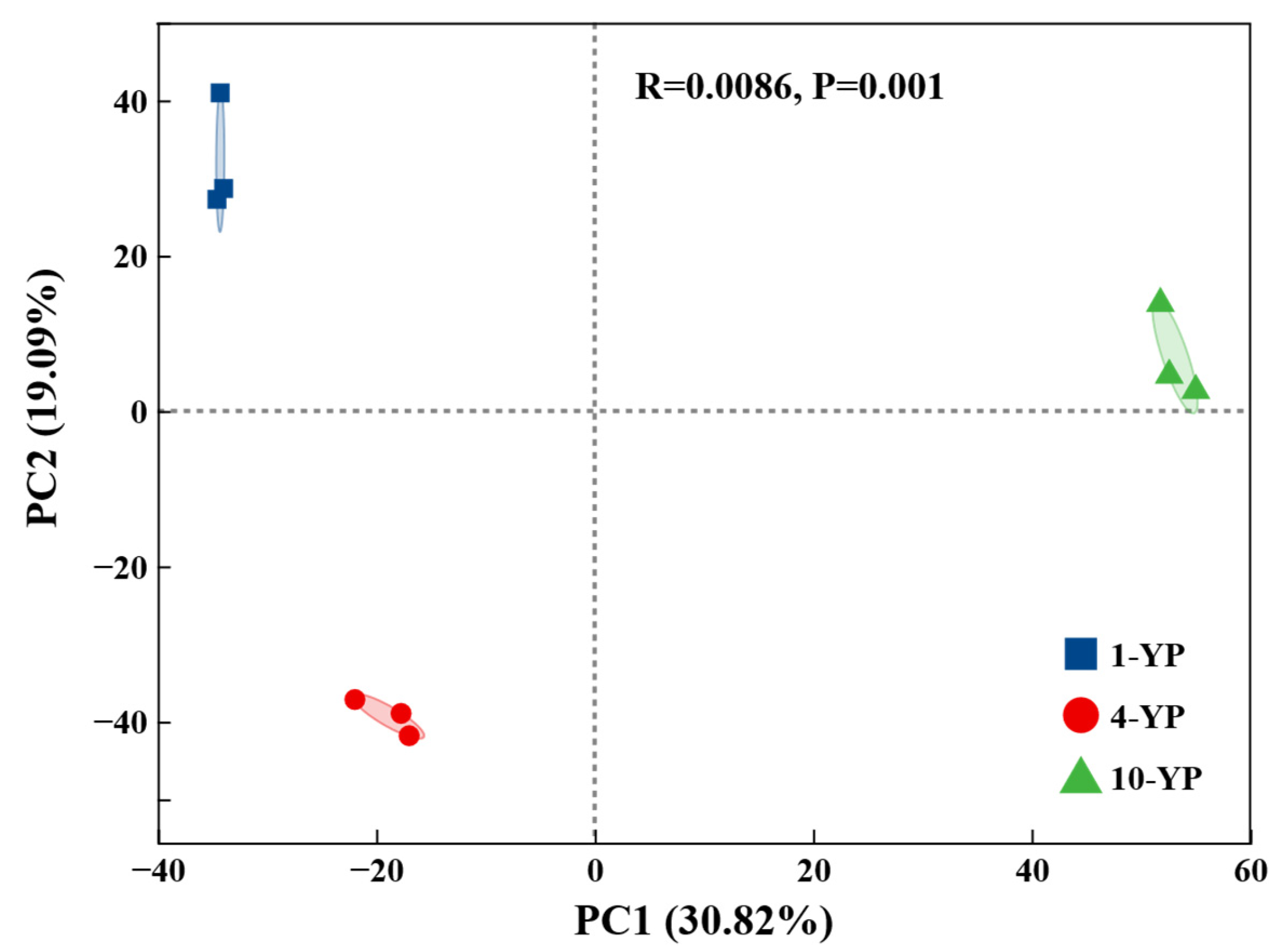

3.2.1. Microbial Community Diversity and Structure

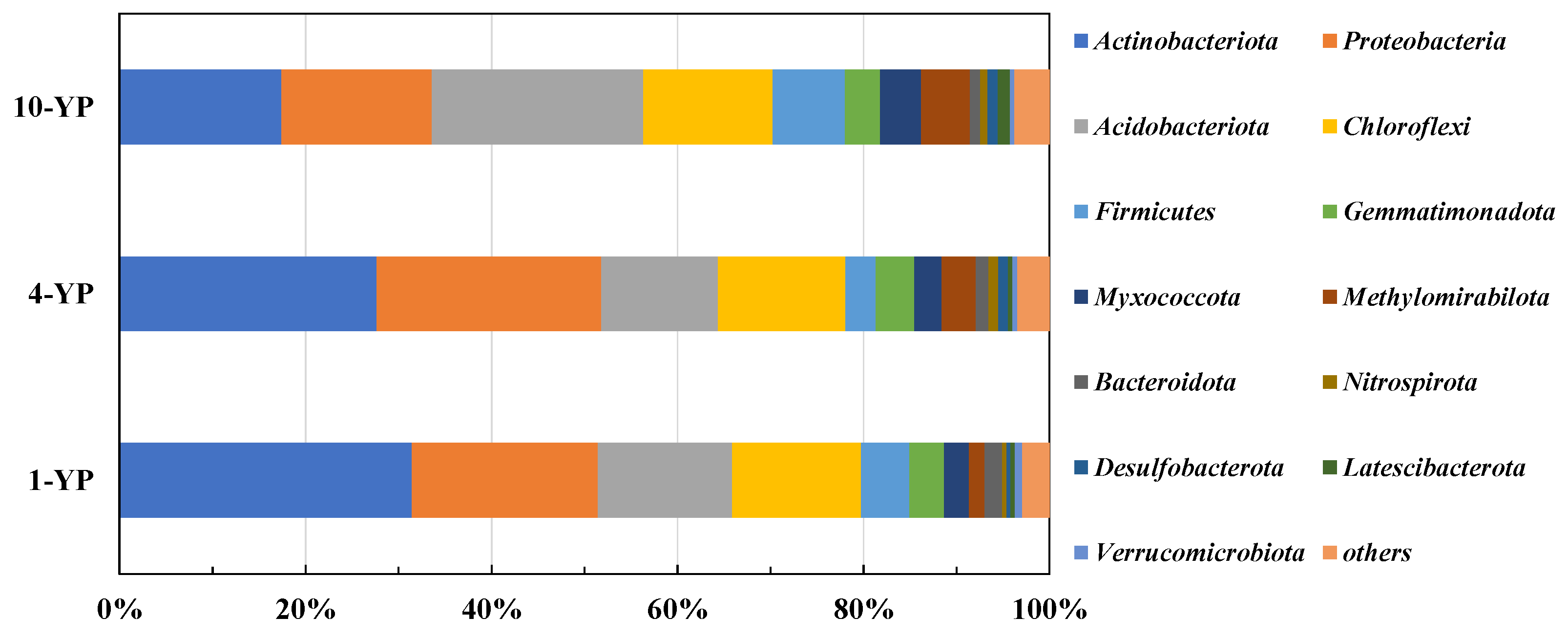

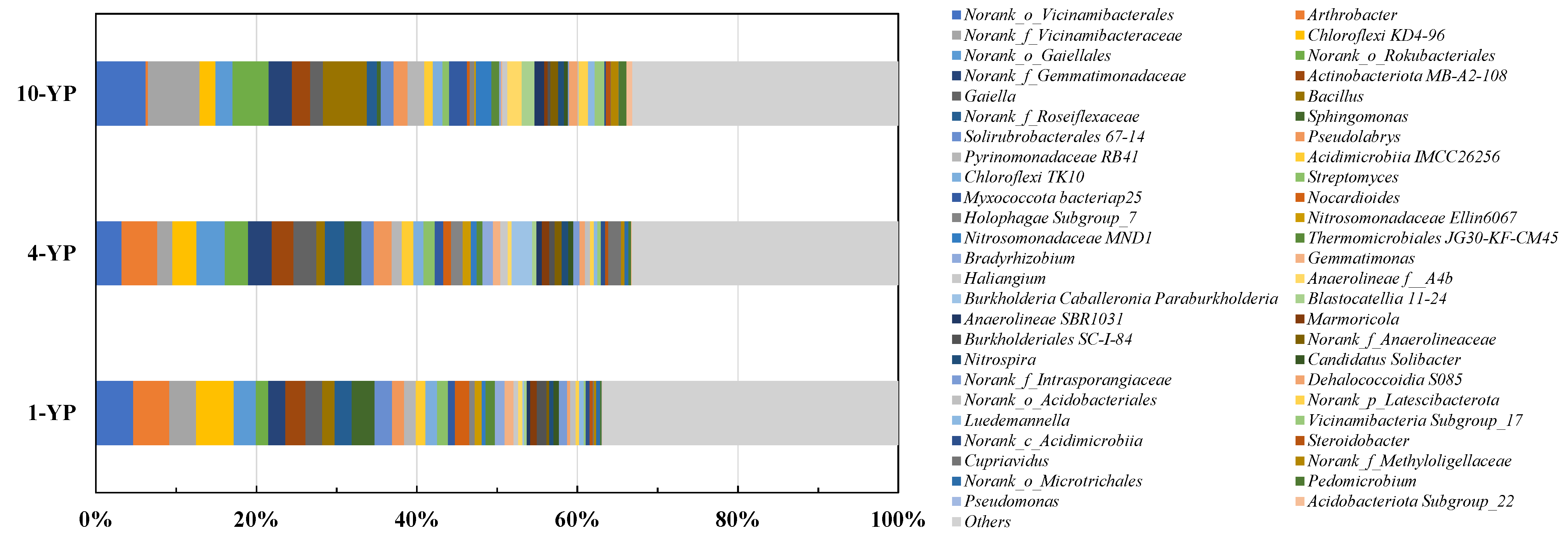

3.2.2. Microbial Community Compositions

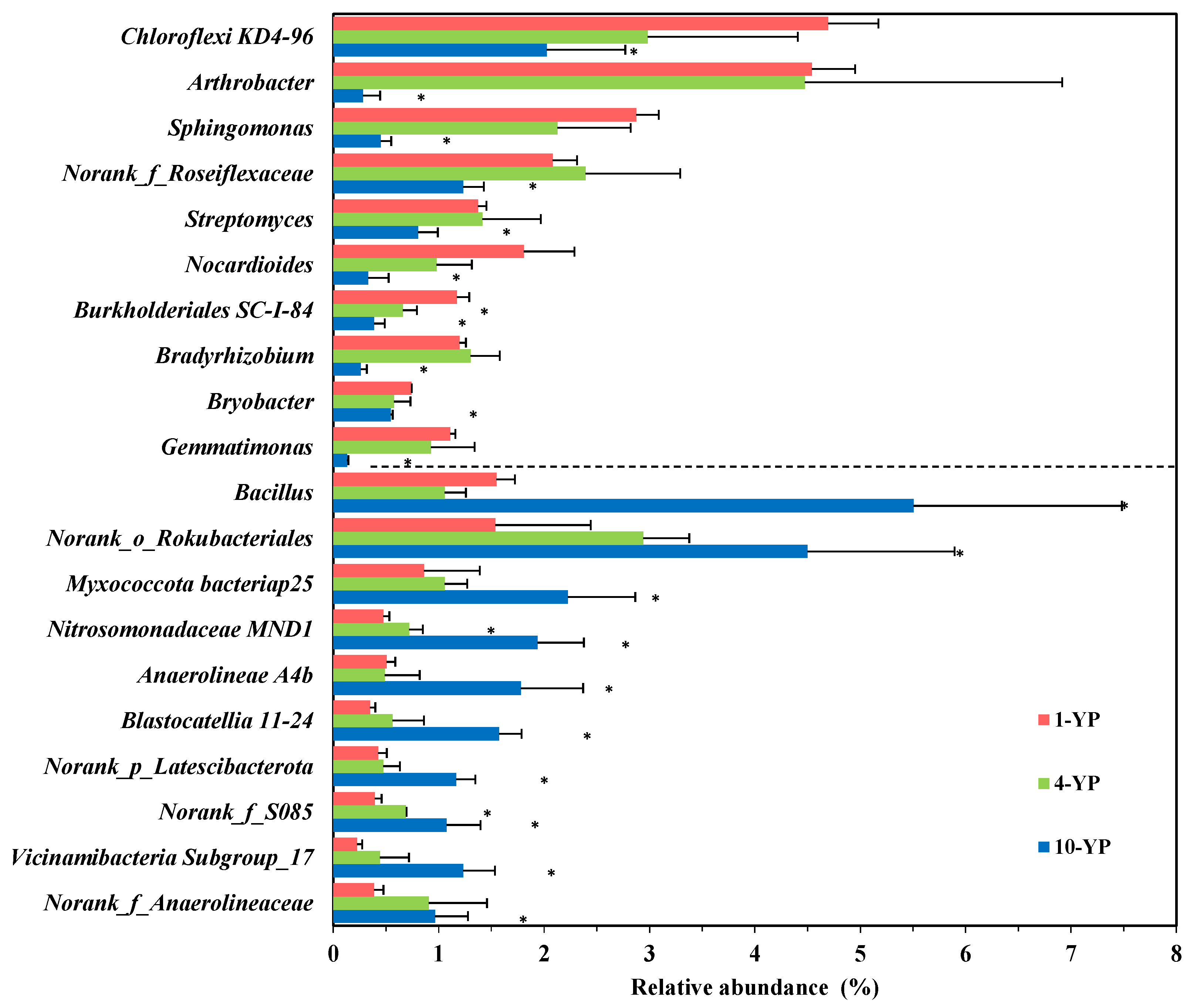

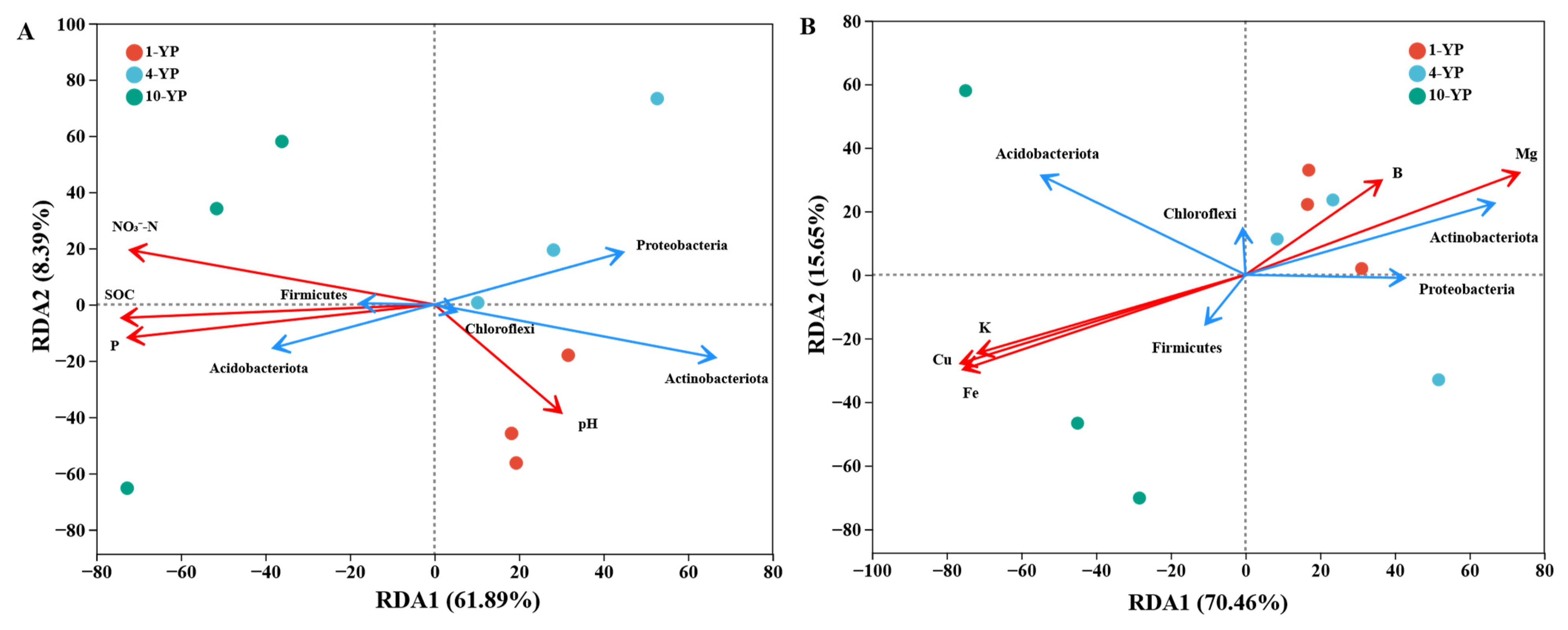

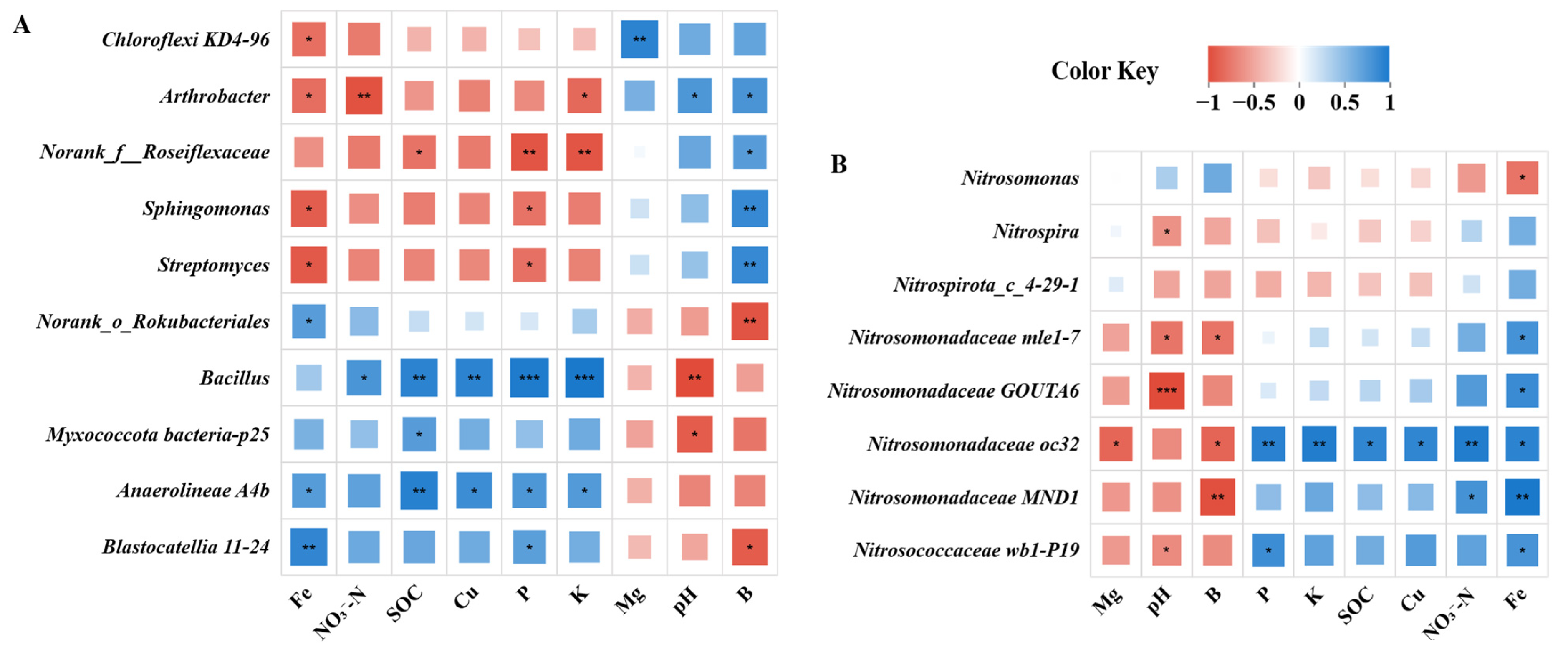

3.3. Linkages Between Soil Physiochemical Properties and Microbial Communities

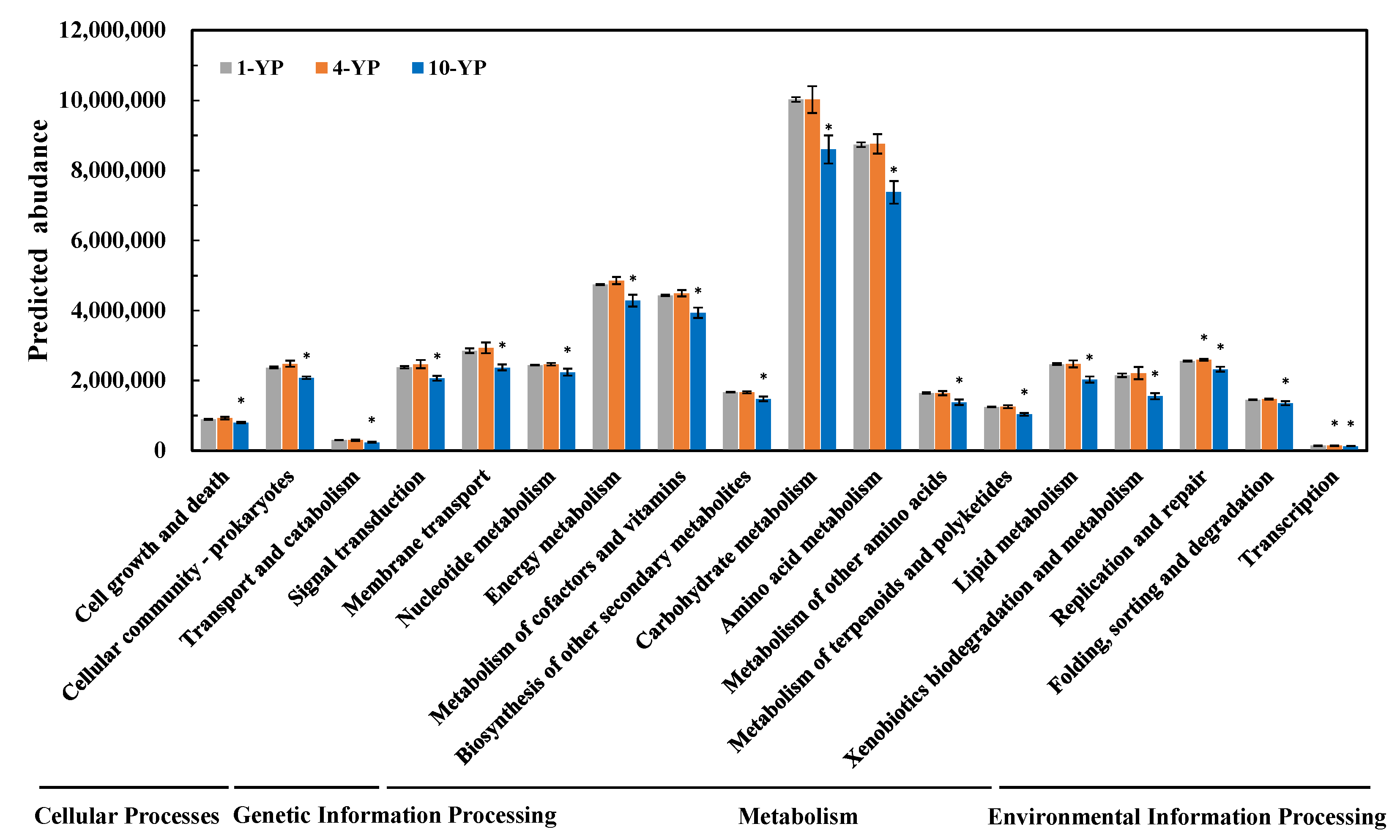

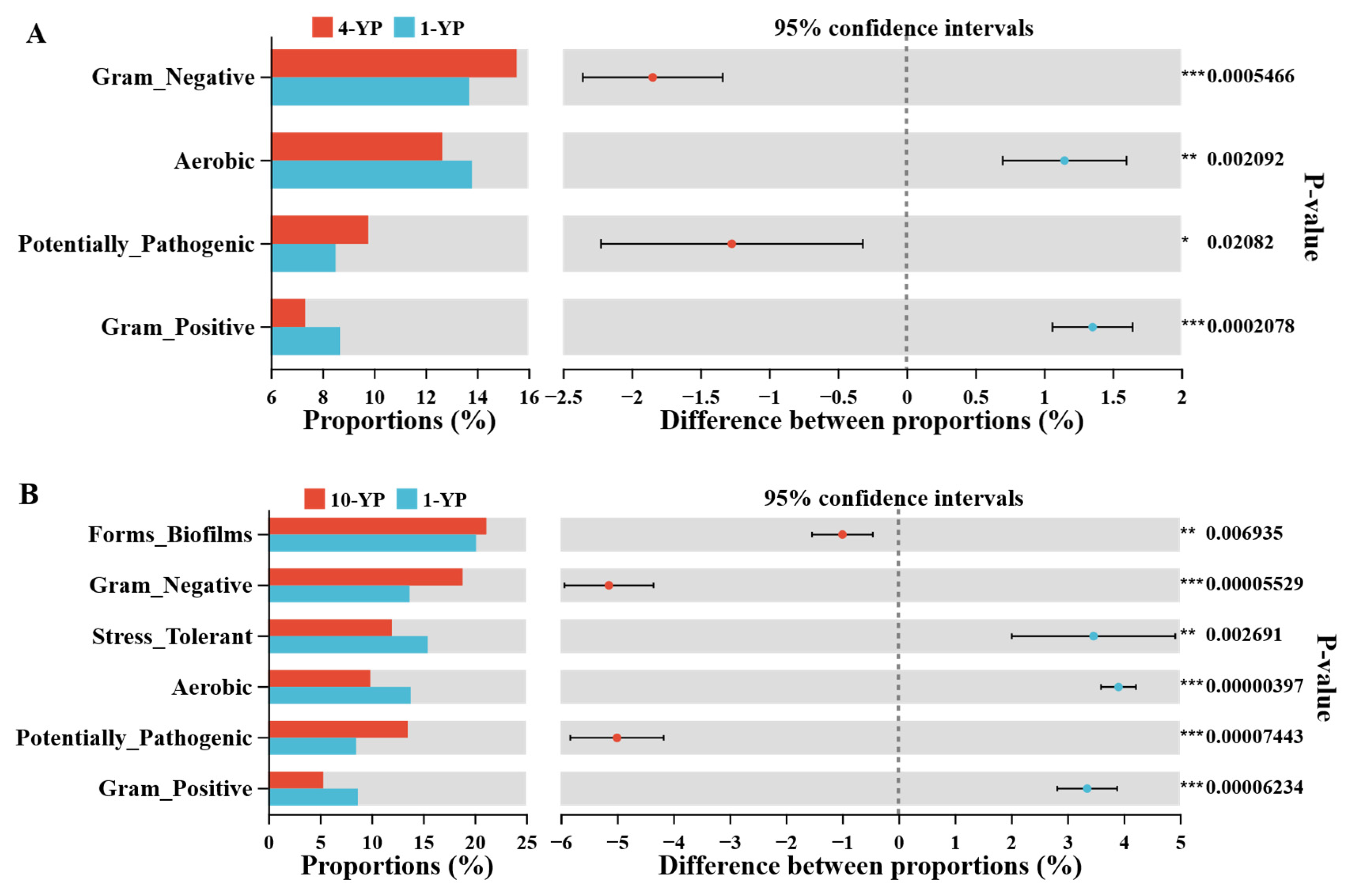

3.4. Microbial Metabolic Pathway and Function Responses

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Physiochemical Property Variations

4.2. Rhizosphere Microbial Community and Metabolic Function Responses

4.3. Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pervaiz, Z.H.; Iqbal, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, D.; Wei, H.; Saleem, M. Continuous cropping alters multiple biotic and abiotic indicators of soil health. Soil Syst. 2020, 4, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Huang, L.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Han, M.; et al. Obstacles in continuous cropping: Mechanisms and control measures. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Volume 179, pp. 205–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, Q.; Dou, Z.; Chi, Z.; Cui, D.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.; Kuang, J.; Wang, N.; Zuo, Y. A review of research progress on continuous cropping obstacles. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobermann, A.; Dawe, D.; Roetter, R.P.; Cassman, K.G. Reversal of rice yield decline in a long-term continuous cropping experiment. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Xiao, P. Genus Paeonia: A comprehensive review on traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, clinical application, and toxicology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 269, 113708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Shehzad, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Karrar, E.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.; Wu, G.; Wang, X. Influence of different extraction methods on the chemical composition, antioxidant activity, and overall quality attributes of oils from peony seeds (Paeonia suffruticosa Andr.). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 2953–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan Ul Haq, M.; Yu, J.; Yao, G.; Yang, H.; Iqbal, H.A.; Tahir, H.; Cui, H.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y. A systematic review on the continuous cropping obstacles and control strategies in medicinal plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.-K.; Guo, Z.; Li, J.-B.; Tian, C.; Hua, D.-W.; Shi, C.-D.; Wang, H.-Y.; Han, J.-C.; Xu, Y. Effects of conservation tillage on soil physicochemical properties and crop yield in an arid loess plateau, China. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Sun, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, X. Changes in the root system of the herbaceous peony and soil properties under different years of continuous planting and replanting. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Seo, Y.-J.; Choi, S.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Ha, S.-K.; Kim, J.-E. Soil physico-chemical properties and characteristics of microbial distribution in the continuous cropped field with Paeonia lactiflora. Korean J. Soil Sci. Fertil. 2011, 44, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zeng, S.; Wu, D.; Jacobs, D.F.; Sloan, J.L. Soil pH, organic matter, and nutrient content change with the continuous cropping of Cunninghamia lanceolata plantations in South China. J. Soils Sediments 2017, 17, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Han, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Tang, Z.; Jiao, W.; Jin, R.; Liu, M.; et al. Effects of continuous cropping of sweet potatoes on the bacterial community structure in rhizospheric soil. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, S.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, E.; Ji, L.; Li, Y.; Tian, L.; et al. Effect of different types of continuous cropping on microbial communities and physicochemical properties of black soils. Diversity 2022, 14, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Dong, F.; Liu, Q.; Lin, W.; Hu, C.; Yuan, Z. Soil metagenomics reveals effects of continuous sugarcane cropping on the structure and functional pathway of rhizospheric microbial community. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 627569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qi, G.; Luo, T.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhao, X. Continuous-cropping tobacco caused variance of chemical properties and structure of bacterial network in soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 4106–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, H.; Yin, Z.; Yang, L.; Ding, X. Evolutions and managements of soil microbial community structure drove by continuous cropping. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 839494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Xue, C.; Zhang, R.; Wu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. The effect of long-term continuous cropping of black pepper on soil bacterial communities as determined by 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Niu, J.; Dang, K.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Changes in physicochemical properties, enzymatic activities, and the microbial community of soil significantly influence the continuous cropping of Panax quinquefolius L. (American ginseng). Plant Soil 2021, 463, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Peng, M. Soil microbial and chemical properties influenced by continuous cropping of banana. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Nie, C.; Wu, T.; Dai, W.; Liu, H.; Yang, R. Analysis of unculturable bacterial communities in tea orchard soils based on nested PCR-DGGE. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 1967–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Yu, T.; Shi, Q.; Han, D.; Yu, K.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Xiang, H.; Wen, R.; Nian, H.; et al. Rhizosphere soil bacterial communities of continuous cropping-tolerant and sensitive soybean genotypes respond differently to long-term continuous cropping in mollisols. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 729047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Yu, Z.; Yao, Q.; Li, Y.; Liang, A.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; et al. Long-term continuous cropping of soybean is comparable to crop rotation in mediating microbial abundance, diversity and community composition. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 197, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Liu, Y.; Peng, S.; Yin, H.; Meng, D.; Tao, J.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, S.; Xiao, N.; et al. Soil potentials to resist continuous cropping obstacle: Three field cases. Environ. Res. 2021, 200, 111319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.; Li, W.; Mei, X.; Yang, X.; Cao, C.; Zhang, H.; Cao, L.; Li, M. Biological control of melon continuous cropping obstacles: Weakening the negative effects of the vicious cycle in continuous cropping soil. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01776-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.-Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, Q.; Xia, G.-Q.; Zhu, J.-Y. Diversity and composition of the Panax ginseng rhizosphere microbiome in various cultivation modesand ages. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Shen, J.; Qu, Z.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; Nie, X.; Zhu, L. Effects of long-term cotton continuous cropping on soil microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Dai, H.; He, Y.; Liang, T.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Cai, H.; Dai, B.; Xu, Y.; et al. Continuous cropping system altered soil microbial communities and nutrient cycles. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1374550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Dai, T.; Wu, H.; Tang, Y.; Ma, Y. Wet-dry alternating conditions regulated soil phosphorus mobilization in the water level fluctuation zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir tributary, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, W.; Xu, J.; Guan, P.; Chang, L.; Wu, X.; Wu, D. Fallow land enhances carbon sequestration in glomalin and soil aggregates through regulating diversity and network complexity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under climate change in relatively high-latitude regions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 930622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LY/T 1228-2015; Nitrogen Determination Methods of Forest Soils. State Forestry Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Lin, K.; Xu, J.; Dong, X.; Huo, Y.; Yuan, D.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Y. An automated spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of nitrite and nitrate in seawater: Nitrite removal with sulfamic acid before nitrate reduction using the vanadium reduction method. Microchem. J. 2020, 158, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LY/T 1232-2015; Phosphorus Determination Methods of Forest Soils. State Forestry Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- LY/T 1234-2015; Potassium Determination Methods of Forest Soils. State Forestry Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- LY/T 2445-2015; Technical Specification for Protection of Topsoil Used for Landscaping. State Forestry Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- HJ 804-2016; Soil-Determination of Bioavailable Form of Eight elements–Extraction with Buffered DTPA Solution/Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry. Ministry of Environmental Protection: Beijing, China, 2016.

- NY/T 1121.8-2006; Method for Determination of Available Boron in Soils. Ministry of Agriculture: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Wang, G.; Ren, Y.; Bai, X.; Su, Y.; Han, J. Contributions of beneficial microorganisms in soil remediation and quality improvement of medicinal plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.W. The role of soil organic matter in maintaining soil quality in continuous cropping systems. Soil Tillage Res. 1997, 43, 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkesford, M.; Horst, W.; Kichey, T.; Lambers, H.; Schjoerring, J.; Møller, I.S.; White, P. Chapter 6—Functions of macronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marschner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 135–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Lou, J.; Li, X.; Wei, M. Changes in rhizospheric microbiome structure and soil metabolic function in response to continuous cucumber cultivation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, H.; Kuang, A.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Ji, X. Rhizospheric soil and root endogenous fungal diversity and composition in response to continuous Panax notoginseng cropping practices. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 194, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadley, M.; Brown, P.; Cakmak, I.; Rengel, Z.; Zhao, F. Chapter 7—Function of nutrients: Micronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marschner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 191–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, M.; Shrivastava, N.; Bisht, S.; Sharma, S.; Varma, A. Interaction among rhizospheric microbes, soil, and plant roots: Influence on micronutrient uptake and bioavailability. In Plant, Soil and Microbes: Volume 2: Mechanisms and Molecular Interactions; Hakeem, K.R., Akhtar, M.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Wu, L.; Wu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Kong, L.; Lin, W. Analysis of physicochemical properties and microbial diversity in rhizosphere soil of Achyranthes bidentata under different cropping years. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 5621–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhong, S.; Mo, Y.; Guo, G.; Zeng, H.; Jin, Z. Effect of continuous cropping on soil chemical properties and crop yield in banana plantation. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2014, 16, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, L.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, D.; Sun, X. Analysis of changes in herbaceous peony growth and soil microbial diversity in different growing and replanting years based on high-throughput sequencing. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, M. Assessment and management of soil microbial community structure for disease suppression. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuppinger-Dingley, D.; Schmid, B.; Petermann, J.S.; Yadav, V.; De Deyn, G.B.; Flynn, D.F.B. Selection for niche differentiation in plant communities increases biodiversity effects. Nature 2014, 515, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Noll, L.; Böckle, T.; Dietrich, M.; Herbold, C.W.; Eichorst, S.A.; Woebken, D.; Richter, A.; et al. Soil multifunctionality is affected by the soil environment and by microbial community composition and diversity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 136, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradin, E.F.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Physiology and molecular aspects of Verticillium wilt diseases caused by V. dahliae and V. albo-atrum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharsini, P.; Dhanasekaran, D. Diversity of soil Allelopathic Actinobacteria in Tiruchirappalli district, Tamilnadu, India. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2015, 14, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielak, A.M.; Barreto, C.C.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; van Veen, J.A.; Kuramae, E.E. The ecology of Acidobacteria: Moving beyond genes and genomes. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber Christian, L.; Hamady, M.; Knight, R.; Fierer, N. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 5111–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Karwautz, C.; Andrei, S.; Klingl, A.; Pernthaler, J.; Lueders, T. A novel Methylomirabilota methanotroph potentially couples methane oxidation to iodate reduction. mLife 2022, 1, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettwig Katharina, F.; van Alen, T.; van de Pas-Schoonen Katinka, T.; Jetten Mike, S.M.; Strous, M. Enrichment and molecular detection of denitrifying methanotrophic bacteria of the NC10 phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 3656–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy Chelsea, L.; Yang, R.; Decker, T.; Cavalliere, C.; Andreev, V.; Bircher, N.; Cornell, J.; Dohmen, R.; Pratt, C.J.; Grinnell, A.; et al. Genomes of novel Myxococcota reveal severely curtailed machineries for predation and cellular differentiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e01706-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, S.; Francioli, D.; Ulrich, A.; Kolb, S. Crop host signatures reflected by co-association patterns of keystone Bacteria in the rhizosphere microbiota. Environ. Microbiome 2021, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, K.; Shang, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, T.; Wanyan, Y.; Wang, E.; Tian, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, W.; et al. Plant growth–promoting bacteria improve maize growth through reshaping the rhizobacterial community in low-nitrogen and low-phosphorus soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2021, 57, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freches, A.; Fradinho Joana, C. The biotechnological potential of the Chloroflexota phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e01756-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Kumar, A. Chapter 1—Arthrobacter. In Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology; Amaresan, N., Senthil Kumar, M., Annapurna, K., Kumar, K., Sankaranarayanan, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Muhammad, N.; Latif, K.A.; and Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: From diversity and genomics to functional role in environmental remediation and plant growth. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becraft, E.D.; Woyke, T.; Jarett, J.; Ivanova, N.; Godoy-Vitorino, F.; Poulton, N.; Brown, J.M.; Brown, J.; Lau, M.C.Y.; Onstott, T.; et al. Rokubacteria: Genomic giants among the uncultured bacterial phyla. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zi, H.; Zhu, H.; Liao, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, X. Rhizosphere microbiome of forest trees is connected to their resistance to soil-borne pathogens. Plant Soil 2022, 479, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.I.; Head, I.M.; Stein, L.Y. The family Nitrosomonadaceae. In The Prokaryotes: Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria; Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A.; Romero, D.; de Vicente, A. Plant protection and growth stimulation by microorganisms: Biotechnological applications of Bacilli in agriculture. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011, 22, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, J.; Hui, T.; and Ji, M. Bacillus species as versatile weapons for plant pathogens: A review. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2017, 31, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Marin, M.F.; Chávez-Avila, S.; Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.D.C.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Glick, B.R.; Santoyo, G. Survival strategies of Bacillus spp. in saline soils: Key factors to promote plant growth and health. Biotechnol. Adv. 2024, 70, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | 1-YP | 4-YP | 10-YP |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.28 ± 0.09 | 7.17 ± 0.27 | 6.98 ± 0.17 * |

| Samples | Ace | Chao | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-YP | 3577.737 ± 120.683 | 3551.170 ± 146.344 | 6.542 ± 0.022 | 5.221 ± 0.267 |

| 4-YP | 3286.975 ± 168.963 * | 3261.928 ± 138.040 * | 6.365 ± 0.092 * | 6.224 ± 2.239 |

| 10-YP | 3148.058 ± 122.833 * | 3188.067 ± 126.686 * | 6.539 ± 0.034 | 3.924 ± 0.208 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, H.; Zhu, M.; Ding, C.; Wu, J. Soil Physiochemical Property Variations and Microbial Community Response Patterns Under Continuous Cropping of Tree Peony. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112602

Pan H, Zhu M, Ding C, Wu J. Soil Physiochemical Property Variations and Microbial Community Response Patterns Under Continuous Cropping of Tree Peony. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112602

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Hao, Min Zhu, Chenlong Ding, and Junkang Wu. 2025. "Soil Physiochemical Property Variations and Microbial Community Response Patterns Under Continuous Cropping of Tree Peony" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112602

APA StylePan, H., Zhu, M., Ding, C., & Wu, J. (2025). Soil Physiochemical Property Variations and Microbial Community Response Patterns Under Continuous Cropping of Tree Peony. Agronomy, 15(11), 2602. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112602