Responses of Rice Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity to Drought–Flood Abrupt Alternation: Implications for Yield and Water Use Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Treatment

2.3. Measurement and Methods

2.3.1. Experimental Observation Data

2.3.2. Photosynthetic Physiological Model

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

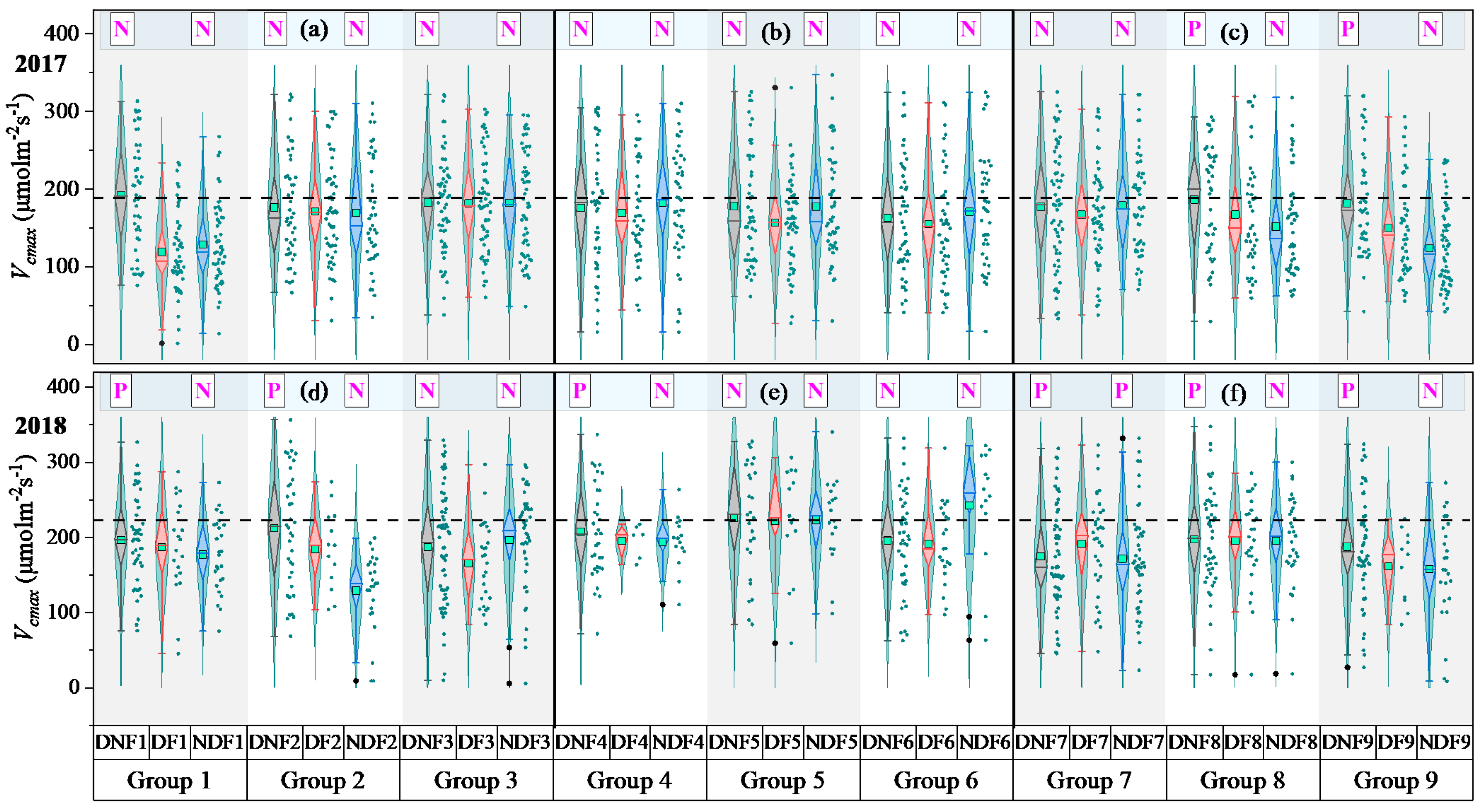

3.1. Effect of DF Events on of Rice

3.1.1. Recovery Characteristics of Rice After Drought and Flood Stresses

3.1.2. Role of Drought and Flooding Stress Degrees and Durations on

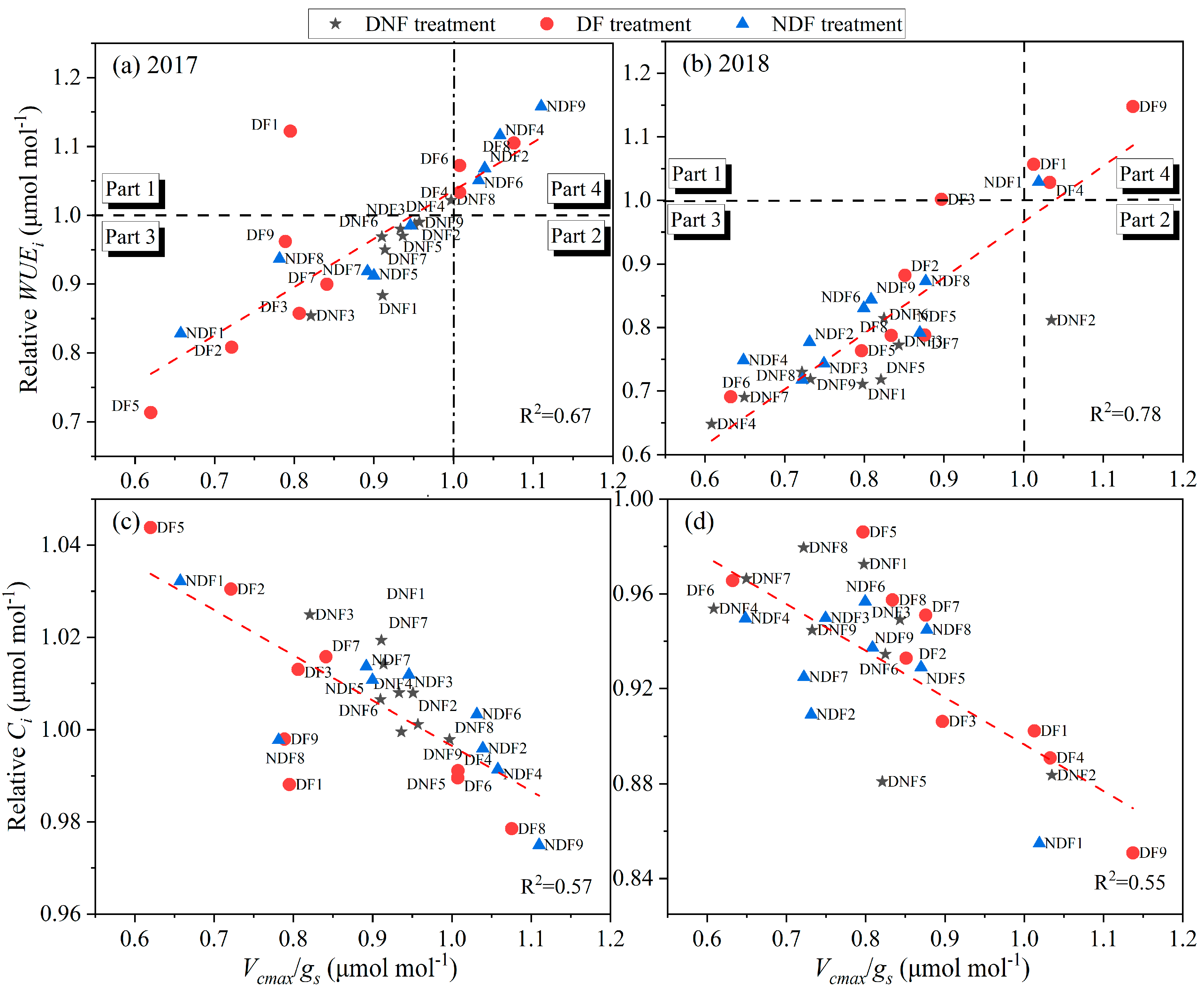

3.2. Interactions Between Drought and Flooding on Rice in DF Events

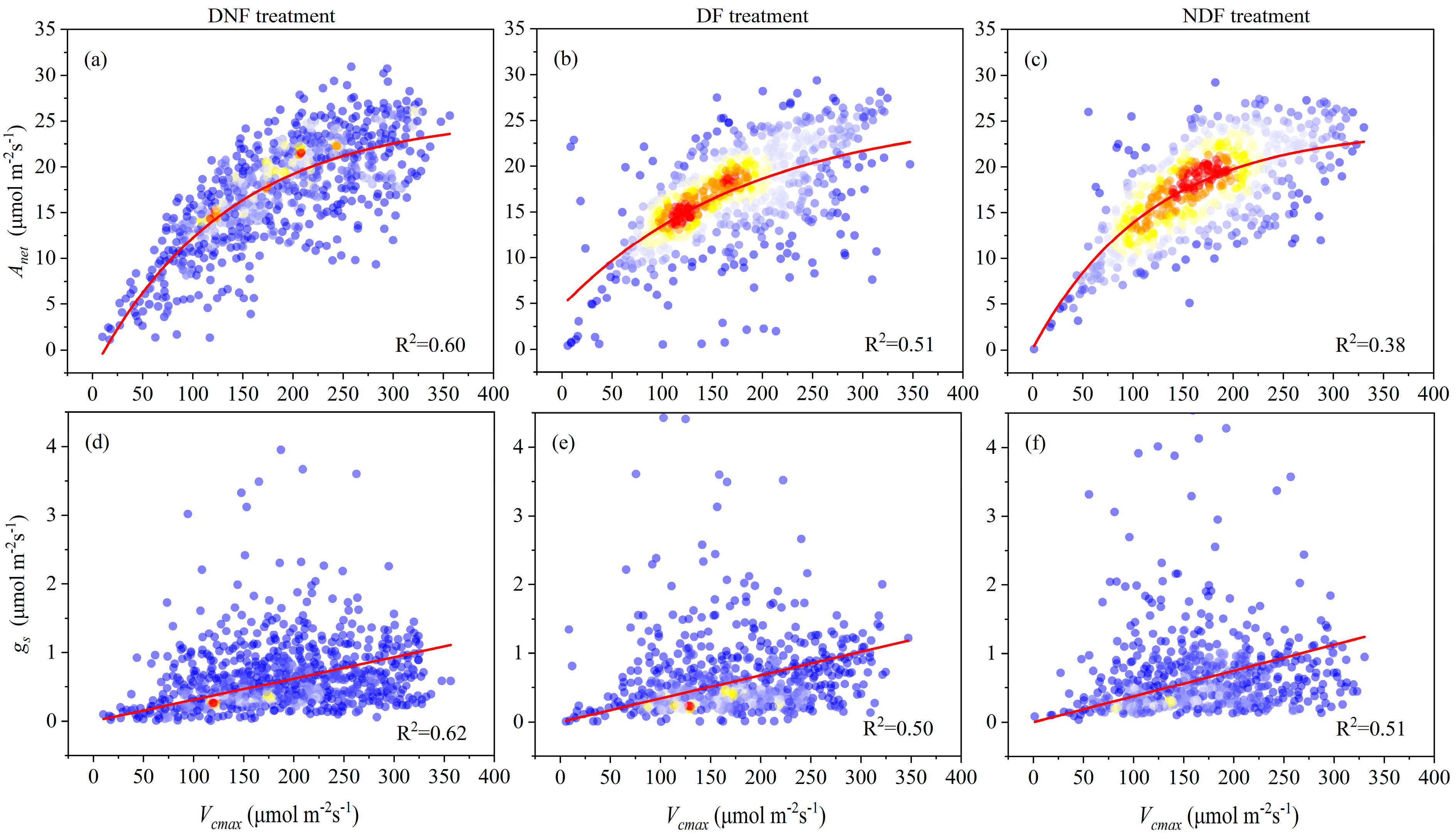

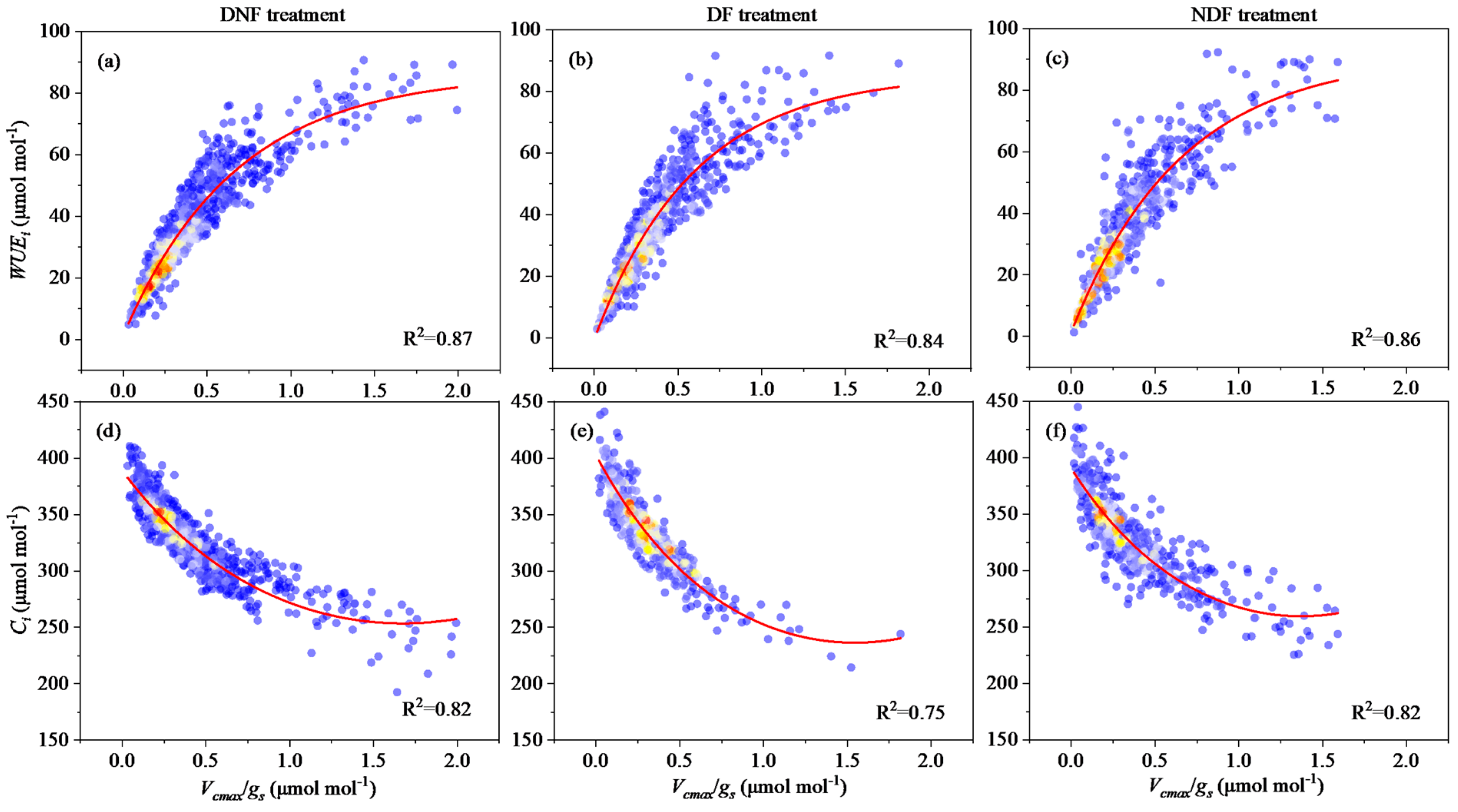

3.3. The Interrelation Between and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency in Different Treatments

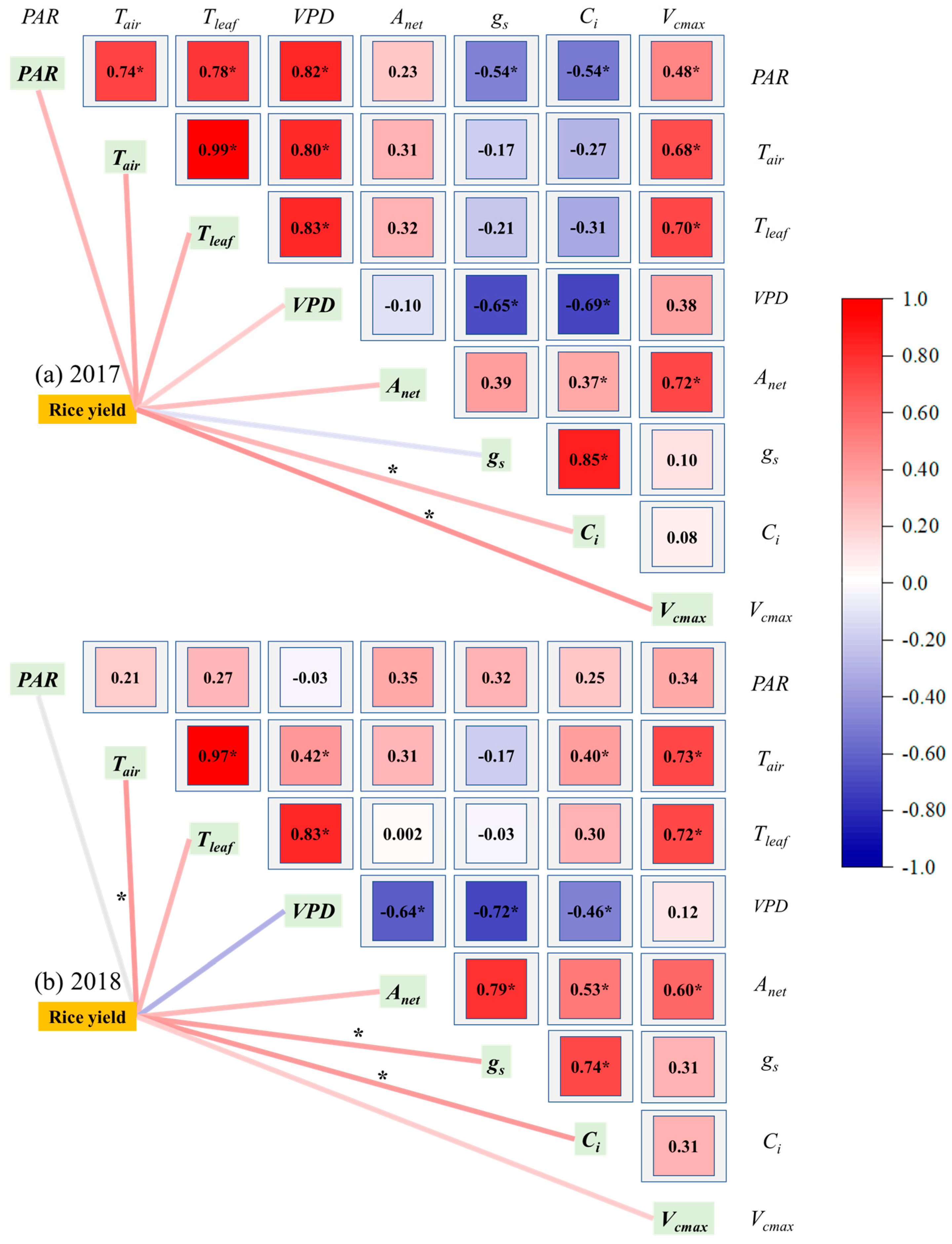

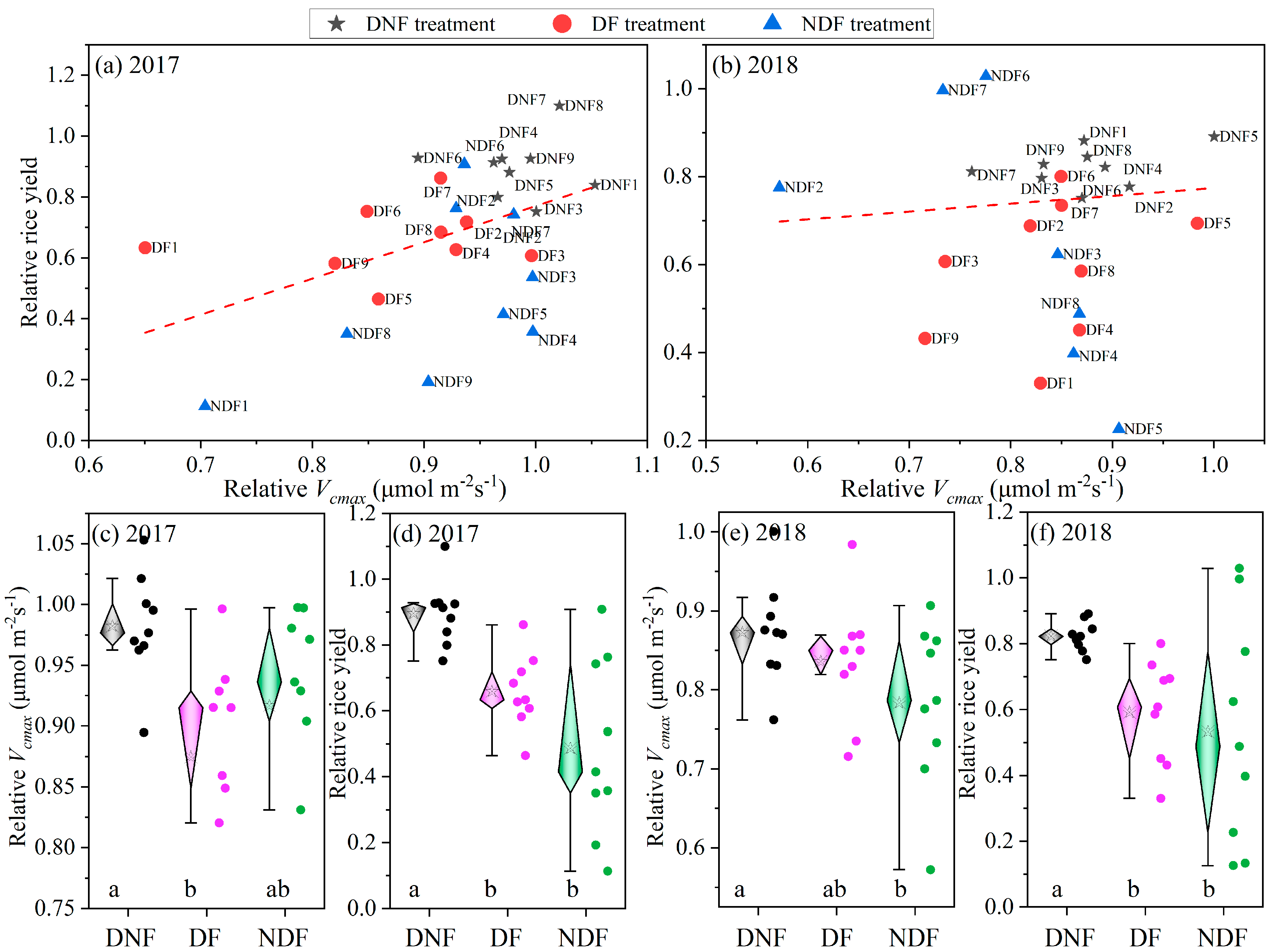

3.4. Correlation of Rice Yield with Key Biotic and Abiotic Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of DF Stress on Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity ()

4.2. Interactions Between Drought and Flooding on

4.3. Rice Improving Water Use by Investing in

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, W.; Huang, S.; Liu, D.; Huang, Q.; Han, Z.; Leng, G.; Wang, H.; Liang, H.; Li, P.; Wei, X. Drought-flood abrupt alternation dynamics and their potential driving forces in a changing environment. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; You, Q.; Ullah, S.; Chen, C.; Shen, L.; Liu, Z. Substantial increase in abrupt shifts between drought and flood events in China based on observations and model simulations. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhu, R.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Jing, P.; Mahmoud, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Response of rice’s hydraulic transport and photosynthetic capacity to drought-flood abrupt alternation. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencuccini, M.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Binks, O.; Knipfer, T.; Konings, A.G.; Novick, K.; Poyatos, R.; Martínez Vilalta, J. A new empirical framework to quantify the hydraulic effects of soil and atmospheric drivers on plant water status. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, X.; Liu, D.; Pedersen, O. Flooding-adaptive root and shoot traits in rice. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP23226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Ding, R.; Du, T.; Kang, S.; Tong, L.; Li, S. Stomatal conductance drives variations of yield and water use of maize under water and nitrogen stress. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 268, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Flexas, J. Photosynthetic limitations in response to water stress and recovery in Mediterranean plants with different growth forms. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, H.; Chen, J.M.; Luo, X.; Bartlett, P.; Chen, B.; Staebler, R.M. Leaf chlorophyll content as a proxy for leaf photosynthetic capacity. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 3513–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmes, J.; Flexas, J.; Keys, A.J.; Cifre, J.; Mitchell, R.; Madgwick, P.J.; Haslam, R.P.; Medrano, H.; Parry, M. Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2005, 28, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Hu, T.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y. Photosynthetic and hydraulic changes caused by water deficit and flooding stress increase rice’s intrinsic water-use efficiency. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Medlyn, B.; Sabate, S.; Sperlich, D.; Prentice, I.C. Short-term water stress impacts on stomatal, mesophyll and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis differ consistently among tree species from contrasting climates. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.X.; Medlyn, B.E.; Prentice, I.C. Long-term water stress leads to acclimation of drought sensitivity of photosynthetic capacity in xeric but not riparian Eucalyptus species. Ann. Bot. 2016, 117, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, G.; Wankmüller, F.; Ahmed, M.A.; Carminati, A. How the interactions between atmospheric and soil drought affect the functionality of plant hydraulics. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiago, D.S.L.; Oliveira De Freitas, R.M.; Da Silva Dias, N.; Dallabona Dombroski, J.L.; Nogueira, N.W. The interplay between leaf water potential and osmotic adjustment on photosynthetic and growth parameters of tropical dry forest trees. J. For. Res. 2023, 34, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Tan, N.; Tissue, D.T.; Huang, J.; Duan, H.; Su, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Physiological traits and response strategies of four subtropical tree species exposed to drought. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 203, 105046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, K.; Yamori, W.; Groszmann, M.; Evans, J.R. Stomatal, mesophyll conductance, and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis during induction. Plant Physiol. 2021, 185, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezara, W.; Driscoll, S.; Lawlor, D.W. Partitioning of photosynthetic electron flow between CO2 assimilation and O2 reduction in sunflower plants under water deficit. Photosynthetica 2008, 46, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voesenek, L.; Rijnders, J.; Peeters, A.; Van de Steeg, H.; De Kroon, H. Plant hormones regulate fast shoot elongation under water: From genes to communities. Ecology 2004, 85, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ten Tusscher, K.H.W.J.; Sasidharan, R.; Dekker, S.C.; de Boer, H.J. Parallels between drought and flooding: An integrated framework for plant eco-physiological responses to water stress. Plant-Environ. Interact. 2023, 4, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, K.L.; Maricle, B.R. Effects of Flooding on Photosynthesis, Chlorophyll Fluorescence, and Oxygen Stress in Plants of Varying Flooding Tolerance. Trans. Kans. Acad. Sci. 2012, 115, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.F.; Guo, X.P.; Zhen, B.; Wang, Z.C.; Zhou, X.G.; Li, X.P. Photosynthetic characteristics of Japonica rice leave under alternative stress of drought and waterlogging. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Q.Q.; Deng, Y.; Zhong, L.; He, H.H.; Chen, X.R. Effects of drought-flood abrupt alternation on yield and physiological characteristics of rice. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2018, 20, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Hu, T.; Yasir, M.; Gao, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhu, R.; Wang, X.; Yuan, H.; Yang, J. Root growth dynamics and yield responses of rice (Oryza sativa L.) under drought—Flood abrupt alternating conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 157, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.Q.; Shen, T.H.; Zhong, L.; Zhu, C.L.; Peng, X.S.; He, X.P.; Fu, J.R.; Ouyang, L.J.; Bian, J.M.; Hu, L.F.; et al. Comprehensive metabolomic, proteomic and physiological analyses of grain yield reduction in rice under abrupt drought-flood alternation stress. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 167, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wu, F.; Zhou, S.; Hu, T.; Huang, J.; Gao, Y. Cumulative effects of drought–flood abrupt alternation on the photosynthetic characteristics of rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 169, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, H.; Yang, J. Effect of drought–flood abrupt alternation on rice yield and yield components. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Rafii, M.Y.; Yusoff, M.M.; Ali, N.S.; Yusuff, O.; Arolu, F.; Anisuzzaman, M. Flooding tolerance in Rice: Adaptive mechanism and marker-assisted selection breeding approaches. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 2795–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xie, H.; Sun, S. Soil moisture assessment based on multi-source remotely sensed data in the huaihe river basin, China. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2020, 56, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.D.; Von Caemmerer, S.; Berry, J.A. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 1980, 149, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medlyn, B.E.; Dreyer, E.; Ellsworth, D.; Forstreuter, M.; Harley, P.C.; Kirschbaum, M.U.F.; Le Roux, X.; Montpied, P.; Strassemeyer, J.; Walcroft, A.; et al. Temperature response of parameters of a biochemically based model of photosynthesis. II. A review of experimental data. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, C.J.; Singsaas, E.L.; Pimentel, C.; Portis Jr, A.R.; Long, S.P. Improved temperature response functions for models of Rubisco-limited photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuning, R. Temperature dependence of two parameters in a photosynthesis model. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperry, J.S.; Venturas, M.D.; Anderegg, W.; Mencuccini, M.; Mackay, D.S.; Wang, Y.; Love, D.M. Predicting stomatal responses to the environment from the optimization of photosynthetic gain and hydraulic cost. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, B.; Guo, X.P.; Lu, H.F.; Zhou, X.G. Response of Rice Growth and Soil Redox Potential to Alternate Drought and Waterlogging Stresses at the Jointing Stage. J. Irrig. Drain. 2018, 37, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.F.; Guo, X.P.; Wang, Z.; Zhen, B.; Liu, C.C.; Yang, J.H. Effects of Alternative Stress of Drought and Waterlogging on Leaf Character. J. Irrig. Drain. 2017, 36, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Liu, Z.; Gao, S.; Wang, M.; Ding, J. Effects of Waterlogging and Drought Alternative Stress Patterns on Fluorescence Parameters and Photosynthetic Characteristics of Rice. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Lin, M.; He, L.; Tang, M.; Ma, J.; Sun, W. The Impact of Water-Saving Irrigation on Rice Growth and Comprehensive Evaluation of Irrigation Strategies. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Wei, Z.; Jiao, X. Intercellular CO2 condentration and stomatal or non-stomatallimitation of rice under water saving irrigation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2010, 26, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Lei, J.; Zhu, W.; Nanyan, L. Physiological and comparative transcriptome analysis of the response and adaptation mechanism of the photosynthetic function of mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves to flooding stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2094619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.P.; Yuan, J.; Guo, F.; Chen, Z. Effects of rapid shift from drought to waterlogging stress on physiological characteristics of rice in late tillering stage. J. Hohai Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2008, 36, 516–519. [Google Scholar]

- Faraloni, C.; Cutino, I.; Petruccelli, R.; Leva, A.R.; Lazzeri, S.; Torzillo, G. Chlorophyll fluorescence technique as a rapid tool for in vitro screening of olive cultivars (Olea europaea L.) tolerant to drought stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2011, 73, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, Z.U.R.; Ayub, M.A.; Zia Ur Rehman, M.; Sohail, M.I.; Usman, M.; Khalid, H.; Naz, K. Chapter 4—Regulation of drought stress in plants. In Plant Life Under Changing Environment; Tripathi, D.K., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.X.; Duursma, R.A.; Medlyn, B.E.; Kelly, J.; Prentice, I.C. How should we model plant responses to drought? An analysis of stomatal and non-stomatal responses to water stress. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 182, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannoura, M.; Epron, D.; Desalme, D.; Massonnet, C.; Tsuji, S.; Plain, C.; Priault, P.; Gerant, D. The impact of prolonged drought on phloem anatomy and phloem transport in young beech trees. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didion-Gency, M.; Gessler, A.; Buchmann, N.; Gisler, J.; Schaub, M.; Grossiord, C. Impact of warmer and drier conditions on tree photosynthetic properties and the role of species interactions. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.F.; Qin, Y.B.; Lin, J.J.; Chen, T.T.; Li, S.F.; Chen, Y.T.; Xiong, J.; Fu, G.F. Unraveling the nexus of drought stress and rice physiology: Mechanisms, mitigation, and sustainable cultivation. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Shu, Y.; Peng, S.; Li, Y. Leaf photosynthesis is positively correlated with xylem and phloem areas in leaf veins in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Ann. Bot. 2022, 129, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Gul, N.; Aslam, S.; Eslamian, S. Biotechnology and Flood-Resistant Rice. In Flood Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mathias, J.M.; Smith, K.R.; Lantz, K.E.; Allen, K.T.; Wright, M.J.; Sabet, A.; Anderson Teixeira, K.J.; Thomas, R.B. Differences in leaf gas exchange strategies explain Quercus rubra and Liriodendron tulipifera intrinsic water use efficiency responses to air pollution and climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3449–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katul, G.; Leuning, R.; Oren, R. Relationship between plant hydraulic and biochemical properties derived from a steady-state coupled water and carbon transport model. Plant Cell Environ. 2003, 26, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Navarro, J.D.; Padilla, Y.G.; Álvarez, S.; Calatayud, Á.; Colmenero-Flores, J.M.; Gómez-Bellot, M.J.; Hernández, J.A.; Martínez-Alcalá, I.; Penella, C.; Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; et al. Advancements in water-saving strategies and crop adaptation to drought: A comprehensive review. Physiol Plant. 2025, 177, e70332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Díaz Espejo, A.; Conesa, M.A.; Coopman, R.E.; Douthe, C.; Gago, J.; Gallé, A.; Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Ribas Carbo, M.; et al. Mesophyll conductance to CO2 and Rubisco as targets for improving intrinsic water use efficiency in C3 plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, L.K.; Creek, D.; Crous, K.Y.; Xiang, S.; Liddell, M.J.; Turnbull, M.H.; Atkin, O.K. Canopy position affects the relationships between leaf respiration and associated traits in a tropical rainforest in Far North Queensland. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrano, H.; Pou, A.; Tomás, M.; Martorell, S.; Gulias, J.; Flexas, J.; Escalona, J.M. Average daily light interception determines leaf water use efficiency among different canopy locations in grapevine. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 114, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Liao, Y.; Hu, T.; Yin, W. Responses of Rice Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity to Drought–Flood Abrupt Alternation: Implications for Yield and Water Use Efficiency. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112573

Liu Y, Zhou Y, Liu S, Liao Y, Hu T, Yin W. Responses of Rice Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity to Drought–Flood Abrupt Alternation: Implications for Yield and Water Use Efficiency. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112573

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yong, Yan Zhou, Sheng Liu, Yongxin Liao, Tiesong Hu, and Wei Yin. 2025. "Responses of Rice Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity to Drought–Flood Abrupt Alternation: Implications for Yield and Water Use Efficiency" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112573

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhou, Y., Liu, S., Liao, Y., Hu, T., & Yin, W. (2025). Responses of Rice Photosynthetic Carboxylation Capacity to Drought–Flood Abrupt Alternation: Implications for Yield and Water Use Efficiency. Agronomy, 15(11), 2573. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112573