Abstract

Soil moisture (SM) is crucial for ecosystems and agriculture. Since the root systems of plants absorb water at different depths with different intensities, monitoring multi-layer SM can better respond to the water demand of plants and offer a crucial technical backing for drought monitoring and precision irrigation. Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and multispectral (MS) have been widely used in SM estimation; however, their combined application for multi-layer SM profiling remains underexplored. Existing research based on these two data types has primarily focused on surface soil moisture (SSM), with limited investigation into estimating SM at deeper or varying depths. Therefore, the aims of this research are to integrate Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 MS data and employ machine learning algorithms to estimate multi-layer SM in the Shandian River Basin. The results showed that (1) MS + SAR-based SM estimation significantly outperformed single-source data (MS or SAR alone). Specifically, MS data performed better in the root-zone estimation, while SAR data showed superior performance in SSM estimation. (2) The BKA-CNN estimation accuracy significantly outperformed RF and XGBoost. The results of its five-fold cross-validation are as follows: R2 = 0.768 ± 0.011 at 3 cm, R2 = 0.777 ± 0.013 at 5 cm, R2 = 0.799 ± 0.011 at 10 cm, R2 = 0.792 ± 0.01 at 20 cm, and R2 = 0.782 ± 0.011 at 50 cm. (3) The BKA-CNN model performed better in grassland than in farmland. These findings indicate that the BKA-CNN model proposed in this study effectively improves the estimation precision of multi-layer SM by fusing SAR and MS data, demonstrating considerable generalization ability and robustness. It holds potential application value in ecological protection and agricultural water resource management.

1. Introduction

Soil moisture (SM) plays a crucial role in the Earth’s ecosystem. It facilitates the exchange among lakes, rivers, groundwater, and the atmosphere [1,2,3]. Additionally, it supports the administration of water resources, environmental strategies, crop cultivation, and various other domains [4,5]. Plant water uptake varies with root depth and intensity, i.e., different root depths have different absorb intensities for SM [6], using surface or average SM alone to characterise plant water demand will deviate from reality. Therefore, understanding root-zone soil moisture (RZSM), particularly the vertical distribution of soil moisture at different depths, is far more important than focusing solely on surface soil moisture (SSM). This understanding is essential for precise drought monitoring and advanced irrigation management [7].

Traditional SM monitoring is obtained by means of in situ measurements such as gravimetry [8], time-domain reflectometry [9], and cosmic ray neutronometry [10,11]. Given that soil texture and structure can vary widely in different regions, along with the variations in land cover, landscape, and weather, obtaining SM data from only one location does not provide a comprehensive understanding [12,13]. Therefore, utilizing only manual or station-based measurements offers information limited to one location, which does not fulfill the need for mapping SM over larger expanses.

The progress of remote sensing technology provides the possibility of capturing the spatial distribution characteristics of SM [14,15]. Remote sensing mainly realizes the monitoring of SM over a large area in three ways, namely: multispectral (MS), thermal infrared (TIR), and microwave remote sensing, whose main principle depends on the construction of empirical models that establish linear or non-linear relationships between remote sensing data from different data sources and SM [16]. The methods for SM mapping based on MS data usually characterize the state change of SM indirectly by calculating vegetation indices, such as normalized vegetation index NDVI [17], vegetation condition index (VCI) [18]. Babaeian et al. [19] developed correlative equations for vegetation condition index and SM in the surface, near-surface and root zone and obtained good inversion results. Existing research on employing Thermal Infrared (TIR) remote sensing to invert SM predominantly devises equations grounded in the associations between land surface temperature, plant foliage temperature, and SM. Kogan et al. [20] constructed the connection equation between the Temperature Condition Index (TCI) and SM, and others have used Apparent Thermal Inertia (ATI), calculated based on daily temperature variations, to invert SM [21,22,23,24]. To take advantage of both, some researchers have constructed some vegetation indices based on MS data and TIR data, such as temperature-vegetation drought index (TVDI) [25], crop water stress index CWSI [26], and certain studies have utilized machine learning models incorporating multiple MS indices and TIR indices to realize multilayer SM inversion in agricultural fields with significantly improved modeling [27,28]. Table 1 summarizes recent studies addressing the same topic, detailing their application contexts, model architectures, data sources, investigated soil depths, and reported accuracies for comparative analysis. Compared with their research, our study uses multiple vegetation coverage scenarios (farmland, grassland) and a more refined depth division (3 cm, 5 cm, 10 cm, 20 cm, and 50 cm) to conduct a more in-depth exploration of the estimation capabilities of MS and synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) data. Microwave frequencies (commonly less than 12 GHz) possess sensitivity to the dielectric features of soil, while the dielectric features are influenced by the alterations in SM [6,29]. Therefore, many satellite missions for SM monitoring have been developed based on microwave sensors, such as SMAP [30,31], ASCAT [32], and SMOS [33,34] However, these satellite products can only access the surface SM (0–5 cm) and have relatively coarse resolutions, ranging from a few kilometers to tens of kilometers. To improve resolution, certain studies have utilized Sentinel-1 SAR images and machine learning algorithm to achieve high-resolution SM inversion and have obtained good estimation accuracy [35,36,37]. Nevertheless, recent scholars indicates that the purported benefits of using SAR for SM inversion may be overly optimistic due to different scenarios [38]. Moreover, since the backscattering intensity of radar is affected by vegetation, these SM products are discontinuous in areas featuring thick vegetation [39,40]. For the purpose of eliminating the interference exerted by vegetation on the radar, Oh et al. [41] proposed the Water Cloud Model (WCM), which characterizes the attenuation impact of vegetation on microwave signal through the Leaf Area Index (LAI) and Vegetation Water Content (VWC), and then outputs the backscattering coefficient related to SM. Subsequent researchers have widely applied the Water Cloud Model in SSM inversion and have obtained good inversion results [42,43]. Another approach to solving this problem is to consider the impacts of both SM and vegetation on the radar simultaneously. For example, certain studies have utilized machine learning models to fuse Sentinel-1,2 data to achieve high-resolution farmland SSM inversion and have obtained good inversion accuracy [44,45,46]. Evidently, integrating MS data with SAR data holds substantial promise for boosting the precision of SM inversion. However, all these studies are limited to SSM, so the ability of these two data sources to estimate SM at deeper or different depths remains in a gray area. In contrast, our study synergistically integrates MS and SAR data through machine-learning algorithms to estimate soil moisture at multiple depths. A systematic evaluation of their respective retrieval capabilities and relative contributions across different soil layers is conducted, offering methodological insights and data support for future investigations.

Over recent years, propelled by the ceaseless evolution of computer science, machine-learning algorithms have seen progressive application in multi-layer SM inversion, yielding highly satisfactory outcomes, such as Random Forest (RF) [27,47], Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) [48], and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [6,49]. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), initially put forward in 1988 [50], serves as a crucial sub-field within machine learning. Owing to its remarkable prowess in extracting image features, CNN has found extensive application across the computer vision field. In recent years, researchers have gradually attempted to apply CNN to SM inversion and have achieved good results. Chen et al. [51] used the CNN algorithm to learn the complex relationship between laboratory-measured visible light-near-infrared reflectance and SM, constructing a 1D-CNN SM inversion model, under the same measurement conditions, the model’s determination coefficient R2 can reach 0.854–0.983. Multiple studies have integrated Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) into the inversion of farmland SSM. Under identical experimental set-ups, direct comparisons were made between CNNs and traditional machine-learning models. Empirical results demonstrate that CNN-based models outperform traditional machine-learning counterparts to varying extents [44,45]. In order to further explore the application scope of CNN, certain studies have utilized CNN to estimate the RZSM (0–20 cm) and have achieved good estimation accuracy: the Sentinel-1 dataset R2 is 0.8664, RMSE is 0.0274 m3/m3; while the Sentinel-2 dataset achieves a precision of R2 is 0.7094, RMSE is 0.0418 m3/m3 using the optimal input combination [35,52]. It is thus evident that CNN has great potential in the field of SM inversion, but it is noteworthy that the current application scenarios of CNN are in the laboratory, SSM inversion, or considering RZSM as a whole value, which cannot meet the application needs of multi-layer SM. Compared with previous efforts, the present study extends the application of CNNs to heterogeneous landscapes (e.g., cropland and grassland) and evaluates their capacity for multi-layer SM estimation. Consequently, the spatial (land-cover types) and vertical (soil depths) dimensions of CNN-based soil-moisture retrieval are simultaneously expanded.

Table 1.

Comparison Of Relevant Studies.

Table 1.

Comparison Of Relevant Studies.

| Paper | Application Scenario | Model | Data Source | Soil Depth | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [47] | agricultural watershed | RF | meteorology, vegetation, soil | 5/10/20/40/80 cm | R2: 0.752–0.861 |

| [27] | farmland/grassland forest | RF | multispectral, thermal infrared | 10/20/40/60/80 cm | R2: 0.73–0.81 |

| [28] | cron | GBM/SVM | multispectral, thermal infrared | 10/20/30/40 cm | R2: 0.79 |

| [6] | conterminous united states | XGBoost | SM product, soil, elevation, vegetation indices, temperature | 5/10/20/50/100 cm | R: 0.79–0.87 |

| [44] | cropland | CNN/SVM/GNN | Sentinel-1 + Sentinel-2 | 5 cm | CNN: R2: 0.8947 SVM: R2: 0.7619 GNN: R2: 0.7098 |

| [48] | chinese loess plateau | ANN | evapotranspiration, temperature, vegetation indices, soil | 0–5 m | R2: 0.697 |

| [51] | laboratory | CNN | multispectral | -- | R2: 0.854–0.983 |

| [35] | grassland | CNN | Sentinel-1 | 0–20 cm | R2: 0.87 |

| [52] | grassland | CNN | Sentinel-2 | 0–20 cm | R2: 0.71 |

| [45] | wheat cropland | CNN+SVM | Sentinel-1 + Sentinel-2 | 3 cm | R2: 0.72 |

Note: R2 denotes the coefficient of determination, whereas R denotes the correlation coefficient.

Collectively, current research indicates that integrating MS and thermal TIR data can markedly boost the precision of multi-layer SM inversion. In addition, a complete appraisal of the performance of these two data sources at different soil depths has been carried out. On the other hand, the integration of SAR and MS data has demonstrated remarkable potential in SM inversion. However, the majority of existing research remains confined to the surface soil layer. Therefore, exploring the performance of these two data sources in estimating SM at different depths remains an area of uncertainty. Traditional machine learning models are relatively mature in the inversion of root zone and multi-layer SM, and previous studies indicate that CNN has strong potential in estimating SM, although its application in multi-layer SM inversion is less common. Accordingly, the objectives of this reserch are: (1) to use machine learning algorithms to explore the performance of different data combinations (MS, SAR, and MS + SAR) in estimating SM at various depths; (2) to investigate the performance differences of three models (RF, XGBoost, and CNN) in estimating SM at different depths; (3) to validate the optimal model at sites with different vegetation cover and explore how vegetation types affect the model’s functionality. Therefore, the principal contributions of this study are threefold:

Systematic evaluation of MS, SAR and their fused data is conducted to quantify their respective performances in soil-moisture estimation across varying depths;

The feasibility and applicability of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) optimized by BKA (Black-winged Kite Algorithm) for multi-layer soil-moisture retrieval are initially explored.

High-resolution maps of multi-layer soil moisture are produced, offering technical support for precision irrigation management and drought monitoring.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Research Area and In-Situ Network

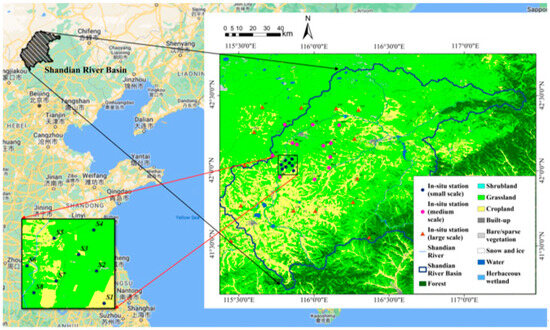

The Shandian River Basin lies along the boundary between Hebei Province and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in China. It exhibits a temperate continental climate. The precipitation pattern is such that precipitation predominantly occurs during the summer months. In most regions of the basin, annual precipitation values fluctuate from 300 to 500 mm. The basin encompasses an area of around 12,700 square kilometers. The SMN-SDR is a SM monitoring network deployed by Zhao et al. [3] during the SMELR experiment in the Shandian River Basin, consisting of 34 sites. Each site is equipped with five 5TM SM sensors, measuring once every hour, within the time frame of 11 September 2018, to 31 December 2019. For ease of description, this study names the measured SM at each layer as follows: 3 cm (SM003), 5 cm (SM005), 10 cm (SM01), 20 cm (SM02), and 50 cm (SM05). The SM data are available for download from the International SM Network, which can be accessed via the International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN) [53]. Regarding sensor calibration and quality control, the ISMN website has uniformly processed the soil moisture data and marked the abnormal data. Subsequently, the downloaded SM data can be extracted using the Python-based toolkit ISMN (version 1.5) with Python 3.8, and we removed the outliers. The vegetation cover types at the site locations are mainly grassland and farmland, with their distribution and the vegetation cover types of the basin shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of SMN-SDR station locations and vegetation coverage in the study area.

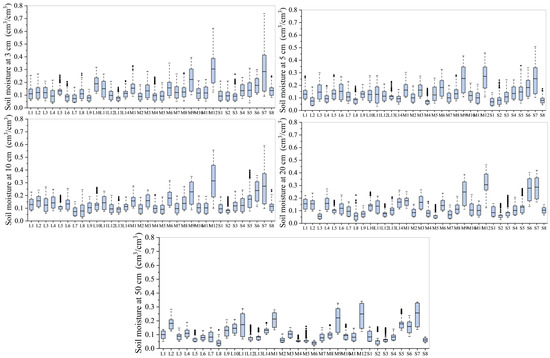

The statistical situation of the five five-layer SM data from 34 sites in SMN-SDR [54] is shown in Figure 2, where the whiskers of each boxplot represent the maximum and minimum values of soil moisture at the sites, and the horizontal lines inside the boxes denote the median. Data from each site were extracted using a strategy of instantaneous matching with remote sensing images. To ensure consistent data quality, we only used data where the soil moisture at all 5 layers was normal during matching; thus, the number of soil moisture samples at each depth was consistent, totaling 889 (including 835 samples in the dataset and 27 samples each from the two validation sites, L10 and S6). Detailed information on the dataset construction is provided in Section 2.3. The SM values at most sites are mostly distributed within 0–0.4 m3/m3 at different depths, with the mean values mainly distributed between 0.05–0.3 m3/m3. The SM values at the surface layer vary greatly among different sites, but as the depth increases, the distribution of SM values at almost all sites shows a trend of narrowing range and decreasing maximum values. Particularly, when the depth reaches 50 cm, the SM values at different sites tend to stabilize. Overall, SMN-SDR can provide sufficient and rich multi-layer in-situ SM measurement data for this study, offering strong data support for the research work in this paper.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of SM distribution at five layers for each station of SMN-SDR.

2.2. Satellite Data Processing

In this research, the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform was exploited to retrieve preprocessed image datasets of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and Multispectral (MS) imagery sourced from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 satellites respectively. The SAR data from Sentinel-1 was sourced from the dataset “COPERNICUS/-S1_GRD”, which has undergone preprocessing steps including Orbit Correction, Radiometric Calibration, Speckle Filtering, Thermal Noise Removal, and Terrain Correction via its built-in Sentinel-1 Toolbox. The data was acquired using the IW mode with polarization modes including VV and VH. The dataset products also include an angle band indicating the radar incidence angle for each pixel at the time of imaging. Given that variations in the local incidence angle induce distinct back-scattering signatures for the same surface target under differing acquisition geometries—thereby degrading model accuracy [43]—we explicitly incorporate the incidence angle as an auxiliary input variable to mitigate this systematic bias and to enhance the model’s adaptability to diverse imaging configurations. Consequently, the Sentinel-1-derived output variables in our dataset comprise VV, VH, and angle. During the study period, the Sentinel-1 mission provided dual-satellite monitoring capabilities for the study area, achieving a temporal resolution of 6 days. Table 2 provides details regarding the bands of the dataset. For this study, the Sentinel-1 incidence-angle band (originally ~20 km) was bilinearly resampled to 10 m to match the VV/VH backscatter grid and co-registered with the SAR features.

Table 2.

Sentinel-1 Band Details.

The MS data of Sentinel-2 employed in the present study are sourced from the dataset named ‘COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARMONIZED’ that is offered by the GEE platform. This dataset is the L2A level product processed from the Sentinel-2 L1C data product by the Sen2Cor toolbox. Therefore, the bands in each pixel of this dataset represent the actual apparent reflectance of the ground objects. The Sentinel-2 satellite delivers MS data with 13 bands. To quantify the vegetation properties within the study area, this research computed 13 vegetation indices using these bands. The specific calculation formulas are presented in Table 3. The Sentinel-2 mission, like Sentinel-1, has a dual-satellite monitoring capability, with a temporal resolution of 3 days. During the process of band extraction, the QA60 and SCL bands of Sentinel-2 were used to build a mask to screen the images and remove pixels affected by clouds and snow. Specifically, the 10th and 11th binary bits of the QA60 band were used to determine whether a pixel was obscured by clouds, and the SCL (Scene Classification Layer) was used to identify snow and ice with the category code 11.

Table 3.

Vegetation index definition formula based on sentinel-2 imagery.

2.3. Data Fusion

Considering that the earliest data from the Sentinel-2 L2A product ‘COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARM-ONIZED’ provided by the GEE platform can only be accessed from 14 December 2018, and the latest SM data provided by SMN-SDR is up to 31 December 2019, this study defines its research window from 14 December 2018, through 31 December 2019. To improve the efficiency of extracting image data, this study extracts the image bands of the research period based on the SMN-SDR site locations on the GEE platform. The extracted SAR image band values and the vegetation indices calculated based on MS are spliced with the multi-layer SM at the SMN-SDR sites according to time, forming two sets of single-source datasets, namely 34 sites SAR and multi-layer SM, MS vegetation index and multi-layer SM. To explore the advantages of multi-source data in the inversion of multi-layer SM, the two sets of single-source data are fused into a multi-source dataset. Since there is a certain time difference between the SAR dataset and the MS dataset, it is necessary to unify the time of the dataset. This study uses the site as the unit and takes the MS dataset time as the baseline to fuse the SAR dataset within 2 days before and after, ultimately forming a multi-source dataset of 34 sites. To avoid factors causing sensor collection failures at a specific layer (such as the day’s weather and soil conditions) from affecting the overall soil moisture collection quality of the site on that day, we selected data with normal collection at every layer on the same day as samples for the dataset; that is, the number of samples at each layer was consistent, specifically 835. The final multi-source input set comprises the Sentinel-1-derived variables VV, VH, and incidence angle, together with thirteen vegetation indices calculated from the Sentinel-2 spectral bands. To prevent spatial bias and safeguard the model’s generalizability, this study applies a stratified random sampling scheme, partitioning the dataset at the station level into a training subset (80%) and a validation subset (20%). In an effort to delve into the model’s generalization capacity and assess its performance at locations with varying degrees of vegetation coverage, two sites that were excluded from the model training process and exhibited distinct vegetation coverages were chosen for additional validation of the model. These sites were L10 (situated in farmland) and S6 (situated in grassland), with each site having 27 samples. It is important to emphasize that the data from these two sites were not used in the model construction process, which means the model will predict in a completely unfamiliar environment. This is undoubtedly a severe test for the adaptability and robustness of the model.

3. Methods

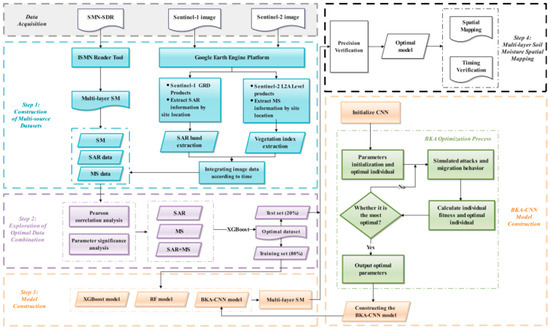

The entire workflow presented in this paper is illustrated in Figure 3. After the dataset construction is completed, this paper mainly achieves the predetermined research objectives through the following three steps. First, it constructs a multi-layer SM inversion model based on XGBoost and different data source combinations (SAR, MS, and MS + SAR) and discusses the optimal data source combination; then, it constructs a BKA-CNN model based on the optimal data source combination and compares it with RF and XGBoost models; finally, carry out the temporal validation of the BKA-CNN at sites with diverse vegetation coverages, and execute the multi-layer SM spatial mapping for the study region.

Figure 3.

Research workflow diagram of this study.

3.1. Black-Winged Kite Algorithm

Wang J. et al. [64] developed the Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA), a swarm intelligence optimization algorithm inspired by nature. It draws inspiration from the survival tactics of the Black-winged Kite, a particular bird species. The BKA simulates the high adaptability and intelligent behavior exhibited by the Black-winged Kite during attacks and migrations. The algorithm integrates Cauchy mutation and leader strategies to boost global search capabilities and accelerate algorithm convergence. It has strong advantages in areas such as engineering optimization, machine learning, and data mining. In this study, the authors compared the BKA with other common optimization algorithms (e.g., PSO [65]) across different benchmark functions. The experimental results demonstrated that the BKA exhibits strong capability in searching for optimal parameters. Therefore, this study attempts to apply the BKA to optimize the hyperparameters of models, including RF, XGBoost, and CNN. Additionally, to explore the optimization performance of the BKA, we compared the optimization quality of the CNN model achieved by the grid search, PSO, and BKA algorithms.

To ensure sufficient search breadth and depth for the BKA, we set the population size to 30 and the number of iterations to 80. Each individual is initialized randomly within the range of each hyperparameter to be optimized. The fitness function for each depth is identical, and the fitness is represented by the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

3.2. RF Model

The Random Forest (RF) model, an ensemble learning algorithm formulated by Breiman [66], is predominantly applied to address classification and regression problems. The RF model is distinguished by its remarkable capacity to withstand overfitting, its proficiency in dealing with high-dimensional data, and its robustness against outliers and noise. This model has a relatively wide application in the field of SM inversion, In this study, the optimized hyperparameters of Random Forest (RF) include n_estimators, max_depth, and max_features. n_estimators controls the number of trees, with an adjustment range of 200–350. Increasing the number of trees generally improves the stability and performance of the model, but it also increases computational overhead. Too few trees may lead to underfitting, while too many trees significantly increase training time and computational costs. Therefore, selecting this value appropriately helps balance performance and computational efficiency. max_depth determines the maximum depth of the trees, with an adjustment range of 5–15. A larger max_depth can make the tree more complex and capture more features, but it also tends to cause overfitting. A smaller depth can prevent overfitting and maintain the model’s generalization ability. max_features controls the maximum number of features considered by each tree when splitting, with an adjustment range of 0.5–1. A smaller max_features value makes the splitting of each tree more independent, which helps reduce overfitting, especially when there are many features. When the value is larger, the tree will consider more features, which may improve accuracy but also increase the risk of overfitting.

3.3. XGBoost Model

The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) regression model developed by Chen Tianqi in 2016, is an efficient regression algorithm based on the gradient boosting framework [67]. It is characterized by its strong regularization capabilities, preventing overfitting by incorporating L1 and L2 regularization terms. Additionally, XGBoost possesses efficient parallel computing capabilities, capable of handling large-scale datasets. In recent years, XGBoost has gradually been applied to SM inversion research and has achieved good results. In this study, the optimized hyperparameters of XGBoost include n_estimators, eta (learning_rate), max_depth, and min_child_weight. The n_estimators is set to 300 to ensure that the model has enough trees for sufficient training, thereby improving prediction accuracy. Eta (also known as learning_rate) controls the contribution of each tree to the final prediction result, with an adjustment range of 0.01–0.1. A smaller eta value helps improve the generalization ability of the model, but it requires increasing the number of trees (i.e., increasing n_estimators), which also means a longer training time. Max_depth controls the maximum depth of the tree, with an adjustment range of 3–10. A smaller depth is suitable for simple datasets, while a larger depth is applicable to complex datasets, as it can capture more nonlinear relationships but tends to cause overfitting. Min_child_weight determines the minimum sum of sample weights for leaf nodes, with an adjustment range of 5–20. A larger min_child_weight value makes the model more conservative, reduces the splitting of leaf nodes, and helps lower the risk of overfitting. Generally, a larger value is chosen to simplify the model structure and avoid overfitting.

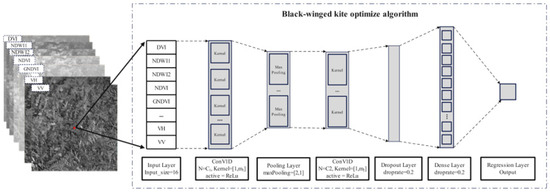

3.4. BKA-CNN Model

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is an algorithm based on deep learning, initially proposed in the 1990s [50], primarily for image processing. CNN employs stacked convolutional and pooling layers to perform hierarchical feature extraction on input data, excelling at capturing local spatial features. Recently, CNNs have been applied to regression problems because, compared to other machine learning models, their hierarchical structure can extract multi-scale features from low-level to high-level through deep networks, making them suitable for handling complex non-linear relationships. However, CNN models have relatively complex hyperparameters, and most existing research adopts manual tuning methods, which are less efficient and can limit model accuracy due to parameter constraints. Therefore, this study constructs a 1D-CNN model based on the BKA optimization algorithm for inverting profile SM. As demonstrated in Figure 4, the architecture of the CNN model utilized in this study is composed of a one-dimensional input layer, two convolutional layers, a single max pooling layer, a fully connected layer, and a regression layer. The input layer is a one-dimensional vector of length 16, which represents 16 input features for a single pixel. The convolutional layers are of vital importance in extracting the characteristic elements of the data. To better extract features, we set the stride of the convolution kernel to 1 and the padding to 0. In these convolutional layers, the ReLu activation function is employed. This function is particularly effective in addressing the issue of gradient vanishing, and it also significantly speeds up the training process. The max pooling layer serves the purpose of decreasing the amount of data while preserving the significant features, with its pool size set to 2. A dropout layer (rate = 0.2) is applied after the second convolutional layer to reduce overfitting. For training, we normalized the data using Min-Max Normalization and adopted RMSE as the loss function. To achieve the optimal model performance, we set the number of training epochs to 150 and implemented an early stopping mechanism: training would be terminated if the RMSE did not improve within 10 consecutive epochs.

Figure 4.

The BKA-CNN model structure proposed in this study.

The BKA optimization algorithm is implemented to optimize the crucial hyperparameters of the CNN model. These hyperparameters encompass the initial learning rate, the batch size, the regularization coefficient, the quantity of convolutional kernels in each layer, and the length of the convolutional kernels. The initial learning rate controls the step size in weight updates during training. A higher learning rate may cause the model to overshoot the optimal weights, while a lower learning rate results in slower convergence. Therefore, our range is set between 0.01 and 0.05 to balance effective learning without excessive training time. The batch size determines the number of samples processed in each iteration. A larger batch size reduces noise but may cause slower convergence, while a smaller batch size increases variance in gradient estimates. Thus, we choose a range of 100 to 150 to ensure stable training while maintaining efficiency. The regularization coefficient prevents overfitting by penalizing large weights. A higher value increases regularization, potentially underfitting the model, while a lower value reduces regularization, risking overfitting. The range of 0.0001 to 0.001 strikes a balance, avoiding both underfitting and overfitting. The length of the convolutional kernels determines the spatial extent of features learned. Larger kernels capture broader patterns but increase complexity, while smaller kernels focus on finer details. We set the range between 2 and 4 to capture both detailed and abstract features without excessive complexity. The number of convolution kernels influences the model’s capacity to learn diverse features. More kernels enhance feature extraction but increase computational cost, while fewer kernels may limit feature diversity. Therefore, our range is 16 to 48 to allow sufficient feature learning without overwhelming computational resources.

3.5. Performance Evaluation

To verify the accuracy of the model in predicting multi-layer SM, five-fold cross-validation is implemented. Furthermore, three indicators, namely the coefficient of determination (R2), the root mean square error (RMSE, unit: m3/m3), and the mean absolute error (MAE, unit: m3/m3), are utilized to quantitatively assess the model performance. R2 represents the consistency of the simulated outputs of the model with the actual data, while RMSE and MAE are utilized to gauge the disparity between the simulated outputs of the model and the actual data. The particular calculation formulas are given below:

where denotes the actual measured value, stands for the arithmetic mean of all the measured values, corresponds to the value forecasted by the model.

To explore the influence of various factors such as mixtures of data sources, and types of models on the accuracy of the model, this research utilizes the One-way Analysis of Variance (One-way ANOVA) to assess and contrast the significance of how different conditions affect the estimation accuracy of SM.

4. Results

4.1. Data Correlation and Analysis

Before model construction, this study used SPSS 27.0 to conduct a correlation analysis between the variables of the dataset and the five-layer SM. The outcomes of this analytical procedure are presented in Table 4. There exists a pronounced correlation among SM values corresponding to different depths, especially between adjacent layers, which can achieve a stronger correlation than other layers. For instance, the correlation coefficient for SM003 and SM005 is 0.931. This may be due to the vertical transfer of moisture and the physical continuity between soil layers. As the depth progresses, the strength of the correlation diminishes. For instance, the correlation coefficient between SM003 and SM05 is 0.754. This attenuation may be associated with factors including soil type and its moisture-retention capabilities [19].

Table 4.

Dataset correlation analysis results.

The correlation between the vegetation index and SM is statistically significant (p < 0.01), and the correlation of most indices with SM tends to strengthen with increasing depth, achieving the highest correlation at 10 cm and 20 cm. Among them, NDVI has the highest correlation, with a correlation of 0.523 at 10 cm and 0.536 at 20 cm. However, the correlation of all vegetation indices gradually decreases at 50 cm, and most correlations are below 0.4. Notably, Because liquid water strongly absorbs in the SWIR, increasing moisture reduces SWIR reflectance; hence MSI increases under drier conditions and is negatively correlated with soil moisture. Moreover, vegetation indices calculated based on SWIR2 (NDWI, MSI) have a higher correlation than those calculated based on SWIR1. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the central band of SWIR2 lies within a more intense water absorption band than SWIR1. As a result, SWIR2 is more responsive to fluctuations in SM. Therefore, vegetation indices calculated based on SWIR2 are relatively more sensitive and are more conducive to capturing the dynamic evolution in SM.

As is evident from Table 4, the magnitude of correlation between the Sentinel-1 SAR backscatter coefficient and SM is typically lower than that of vegetation indices. This phenomenon can potentially be attributed to the significant impact of surface vegetation on backscatter, resulting in more complex scattering information. Among all depths, the backscatter coefficients of the two polarization modes demonstrate the strongest correlation with the SM at 5 cm. Specifically, for the VH band, the correlation coefficient is 0.426, and for the VV band, the correlation coefficient is 0.429. However, as the depth increases, the correlation gradually decreases. This may be due to the depth of soil information obtained by radar signals being influenced by the penetration of C-band microwave radiometers [68]. The backscatter coefficient of the VV polarization mode presents a marginally stronger correlation with the SM compared to that of the VH polarization mode, which may be due to the VH polarization being more susceptible to vegetation interference [69]. Interestingly, the correlation between the radar incidence angle and SM is low, but statistically significant (p < 0.05). This is because different orbital observations and different ascending and descending angles of the same orbit lead to different surface characteristics being captured by the radar. Consequently, these factors influence the sensitivity of the relationship between the backscatter coefficient and SM [43].

To fully exploit the representational capacities of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 observations, the model ingests, as input variables, the Sentinel-1-derived VV and VH backscatter coefficients together with the corresponding incidence angle, complemented by thirteen vegetation indices computed from Sentinel-2 spectral bands.

4.2. Data Performance Evaluation

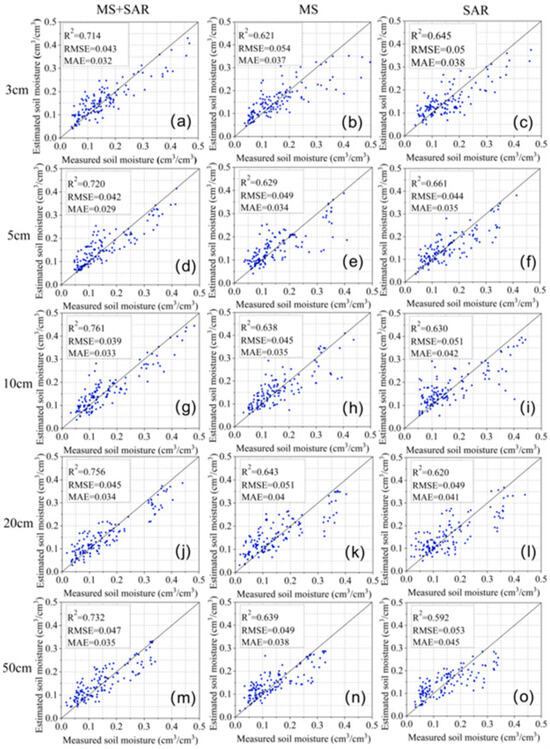

With the aim of examining the impact of distinct data sources on the accuracy of multi-layer SM inversion, this study took three data source combinations (MS, SAR, and MS + SAR) as inputs for the XGBoost model and constructed three multi-layer soil moisture inversion models. The accuracy at different depths are presented in Figure 5. Generally speaking, the accuracies of the three models exhibit a pattern where they initially rise and subsequently decline as the soil depth increases. As can be seen from Figure 5b,k, the model constructed using only the MS vegetation index achieved the best accuracy at 20 cm, with R2 = 0.643, while the accuracy was relatively poorer at the surface layer, 3 cm, with R2 = 0.621. This is because the vegetation index indirectly characterizes SM information at different depths by reflecting the characteristics of vegetation, and the growth status of vegetation is related to the root system that absorbs water [70]. Therefore, higher accuracy is obtained at deeper layers. As demonstrated in Figure 5c,f,o, when compared with the model constructed by using only MS data, the model built solely with SAR data shows superior performance in the surface layers (at 3 cm and 5 cm), and it reaches the peak accuracy level at a depth of 5 cm, with R2 = 0.661, while SAR performs poorly at 50 cm, with R2 = 0.592. On one hand, the backscattering coefficients of the two polarizations, VV and VH, have the highest correlation with SM at 5 cm, thus achieving better estimation accuracy at the surface layer. On the other hand, the information obtained from the backscattering coefficients is affected by the penetration of radar microwaves, which prevents the acquisition of deeper soil information, thereby limiting the model accuracy [71]. Therefore, it performs worse at deeper layers.

Figure 5.

Model performance corresponding to different soil depths with various data source combinations: (a) Joint use of MS and SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 3 cm, (b) Use of MS to estimate SM at a depth of 3 cm, (c) Use of SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 3 cm, (d) Joint use of MS and SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 5 cm, (e) Use of MS to estimate SM at a depth of 5 cm, (f) Use of SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 5 cm, (g) Joint use of MS and SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 10 cm, (h) Use of MS to estimate SM at a depth of 10 cm, (i) Use of SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 10 cm, (j) Joint use of MS and SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 20 cm, (k) Use of MS to estimate SM at a depth of 20 cm, (l) Use of SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 20 cm, (m) Joint use of MS and SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 50 cm, (n) Use of MS to estimate SM at a depth of 50 cm, (o) Use of SAR to estimate SM at a depth of 50 cm.

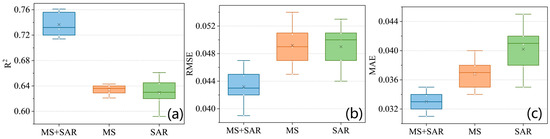

It is noteworthy that when models are constructed using both data sources simultaneously, the model accuracy is significantly improved, with R2 ranging from 0.714 to 0.761, RMSE from 0.039 m3/m3 to 0.047 m3/m3, and MAE from 0.029 m3/m3 to 0.035 m3/m3. Figure 6 is a boxplot of the accuracy indicators of the three models, where the horizontal lines represent the median and “×” denotes the mean. The figure shows that the accuracy of the model using both MS and SAR data at different depths is significantly better than that of models constructed using only MS or SAR data (p < 0.05). This is because the two data sources characterize SM information at different depths from different perspectives, forming a complementary advantage that enhances the overall performance of the model. Furthermore, as presented in Figure 5g, the model achieved the best accuracy at 10 cm, with R2 = 0.761, which is different from the optimal depth when using the two data sources separately. This may be because MS and SAR obtained the greatest SM information gain at 10 cm, achieving a better complementary advantage of the two data sources, thus bringing the model accuracy to a higher level. Overall, the outcomes of this research illustrate that the joint employment of MS and SAR data has substantial potential to monitor and understand the dynamic characteristics of RZSM.

Figure 6.

Boxplot of model accuracy comparison constructed from different data sources: (a) R2, (b) RMSE, (c) MAE.

4.3. All Model Hyperparameter Optimization Results

To investigate the applicability of the CNN model in multi-layer SM inversion, this study constructed a 1D-CNN model based on the MS + SAR dataset for inverting SM in five layers. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model incorporates a substantial number of hyperparameters, and its accuracy is highly susceptible to fluctuations in these hyperparameters. Therefore, in this study, the hyperparameters of the CNNs model for estimating the SM at five layers are optimized based on the Black-winged Kite Optimization Algorithm (BKA). In addition, for a fair comparison, we also used BKA to optimize the hyperparameters of RF and XGBoost. Before optimization, we set the hyperparameter ranges for these three models respectively; the set ranges and their reasons are provided in Section 3. Methods, and Table 5 presents the final results of hyperparameter optimization for the three models at different depths.

Table 5.

BKA optimization results for all model hyperparameters.

4.4. Model Performance Comparison

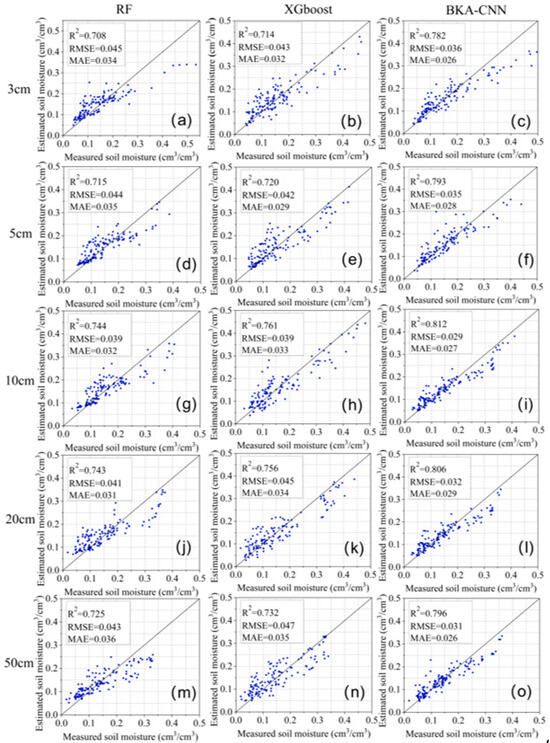

In this study, in an attempt to acquire the optimal model, three multi-layer SM inversion models, namely RF, XGBoost, and BKA-CNN, using the MS + SAR dataset were compared. Figure 7 illustrates the optimal accuracy of these models. The determination coefficients R2 of all models reached 0.7 or above, which further demonstrates the advantage of model fusion of MS and SAR for profile SM inversion. Notably, as presented in Figure 7g–i, the accuracy of the three models increased with depth until reaching the best accuracy at 10 cm, where RF: R2 = 0.744, XGBoost: R2 = 0.761, and BKA-CNN: R2 = 0.812, indicating that the fusion effect of MS and SAR reached the greatest gain at 10 cm.

Figure 7.

Accuracy of three models in estimating SM at different depths: (a) RF estimating SM at 3 cm depth, (b) XGBoost estimating SM at 3 cm depth, (c) BKA-CNN estimating SM at 3 cm depth, (d) RF estimating SM at 5 cm depth, (e) XGBoost estimating SM at 5 cm depth, (f) BKA-CNN estimating SM at 5 cm depth, (g) RF estimating SM at 10 cm depth, (h) XGBoost estimating SM at 10 cm depth, (i) BKA-CNN estimating SM at 10 cm depth, (j) RF estimating SM at 20 cm depth, (k) XGBoost estimating SM at 20 cm depth, (l) BKA-CNN estimating SM at 20 cm depth, (m) RF estimating SM at 50 cm depth, (n) XGBoost estimating SM at 50 cm depth, (o) BKA-CNN estimating SM at 50 cm depth.

However, as the depth continues to increase, the model accuracy constantly decreases, especially at the 50 cm mark where the accuracy of all models significantly drops. One the one hand, it can be seen from Table 4 that as the separation between soil layers becomes greater, the correlation of soil moisture shows a downward trend. Consequently, the accuracy for estimating SM in deeper layers is reduced [6]. On the other hand, as the deeper SM is described indirectly through the plant root system, which is associated with RZSM, an elevation in error occurs [70]. Moreover, an analysis reveals that across locations characterized by higher SM, the estimated values generated by all models exhibit a degree of underestimation when compared to site measurements. This can be attributed to the relatively scarce high-value SM data incorporated during dataset construction. As a result, the models demonstrate reduced sensitivity to higher SM levels during the training process.

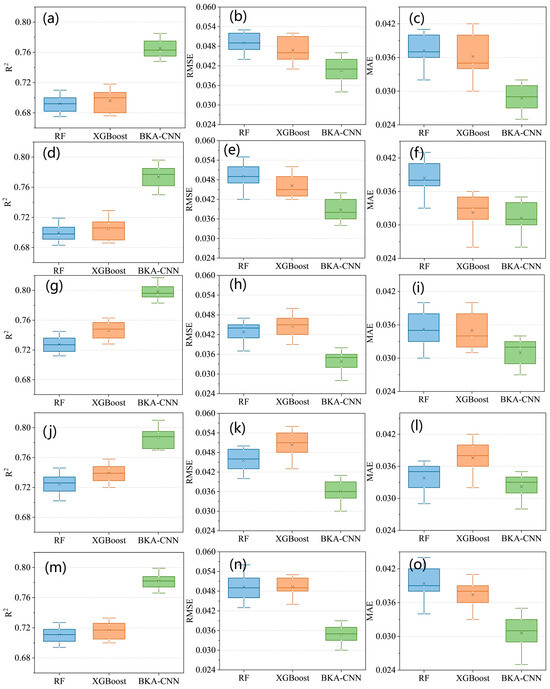

As depicted in Figure 7, the precision of the BKA-CNN model varies with different depths, with R2 ranging from 0.782 to 0.812, RMSE from 0.029 to 0.036, and MAE from 0.026 to 0.029. Moreover, it exhibits higher accuracy than the other two models involved in the study. In this research, to better investigate the stability of the performance of distinct models, five-fold cross-validation was utilized to verify the precision of SM estimation at various depths for the three models. The boxplots of all model cross-validation results are shown in Figure 8. The BKA-CNN model has a higher R2 at different depths than both RF and XGBoost, attaining a statistically significant degree (p < 0.01), while RMSE and MAE are lower than the other two models and also reached a significant level (p < 0.05). The mean values and standard deviations of its five-fold cross-validation metrics at different depths are as follows: 3 cm: R2 = 0.768 ± 0.011, RMSE = 0.041 ± 0.004 m3/m3, MAE = 0.029 ± 0.003 m3/m3; 5 cm: R2 = 0.777 ± 0.013 m3/m3, RMSE = 0.038 ± 0.003 m3/m3, MAE = 0.031 ± 0.003 m3/m3; 10 cm: R2 = 0.799 ± 0.011, RMSE = 0.034 ± 0.004 m3/m3, MAE = 0.031 ± 0.003 m3/m3; 20 cm: R2 = 0.792 ± 0.01, RMSE = 0.036 ± 0.004 m3/m3, MAE = 0.032 ± 0.003 m3/m3; 50 cm: R2 = 0.782 ± 0.011, RMSE = 0.035 ± 0.003 m3/m3, MAE = 0.031 ± 0.003 m3/m3. Therefore, the BKA-CNN model put forward in this research demonstrates a statistically significant edge over traditional machine learning models in multi-layer SM inversion.

Figure 8.

Box plots of cross-validation results for different evaluation metrics of the three models at various depths: (a) R2 of the three models at 3 cm depth, (b) RMSE of the three models at 3 cm depth, (c) MAE of the three models at 3 cm depth, (d) R2 of the three models at 5 cm depth, (e) RMSE of the three models at 5 cm depth, (f) MAE of the three models at 5 cm depth, (g) R2 of the three models at 10 cm depth, (h) RMSE of the three models at 10 cm depth, (i) MAE of the three models at 10 cm depth, (j) R2 of the three models at 20 cm depth, (k) RMSE of the three models at 20 cm depth, (l) MAE of the three models at 20 cm depth, (m) R2 of the three models at 50 cm depth, (n) RMSE of the three models at 50 cm depth, (o) MAE of the three models at 50 cm depth.

Moreover, even though RF and XGBoost have seen extensive application in the domain of SM inversion, there is a scarcity of research comparing their inversion outcomes. This holds especially true when considering multi-layer SM scenarios. inversion. As demonstrated in Figure 8—where “×” denotes the mean value and the horizontal line represents the median—the R2 values of the XGBoost model at distinct depth levels surpass those of the RF model by a small margin. This implies that XGBoost has a better ability to discern and represent the changing patterns of SM. However, at depths of 10 and 20 cm, the RMSE and MAE indicators for XGBoost are slightly inferior to RF, as shown in Figure 8h,i,k,l.

To investigate the effect of different optimization algorithms on improving the accuracy of the CNN model, we also used grid search and PSO algorithm to optimize the hyperparameters of the CNN, i.e., comparing three models: Grid-CNN, PSO-CNN, and BKA-CNN, and analyzing the performance of different optimizations at various depths. To reduce the research burden, we only conducted comparisons at 3 cm, 10 cm, and 50 cm. The final results are shown in Table 6, from which it can be seen that compared with grid search and PSO algorithm, BKA can obtain the optimal hyperparameters for the CNN, enabling the BKA-CNN model to achieve the best accuracy at different depths.

Table 6.

Performance comparison of different optimization algorithms on CNN accuracy.

4.5. Temporal Validation of BKA-CNN

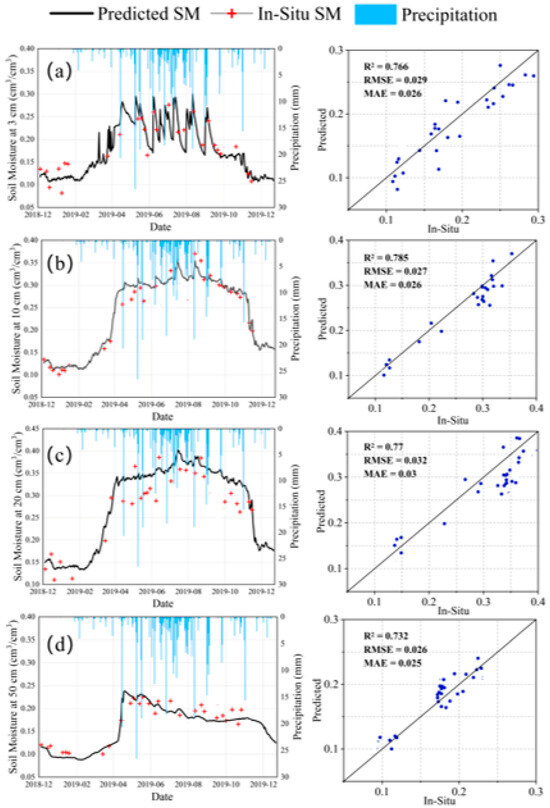

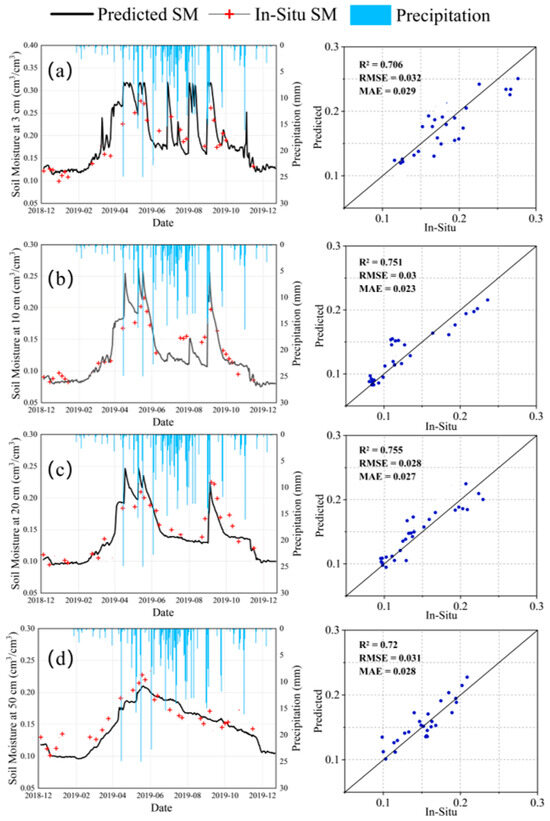

Various types of vegetation cover exert a substantial influence on the precision of SM estimation achieved by models, as reported by Cheng et al. [27]. To gain deeper insights into how effectively the BKA-CNN model, put forward in this study, carries out the estimation of multi-layer SM in various vegetation scenarios, data sourced from two sites which were not involved in the training process and were characterized by distinct vegetation coverage types were utilized to conduct validation of the model. These two sites are S6 (grassland) and L10 (farmland). The temporal validation results of the model at four soil depths (3 cm, 10 cm, 20 cm, and 50 cm) at the two sites are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Temporal validation results of BKA-CNN at different depths in the grassland site: (a) 3 cm, (b) 10 cm, (c) 20 cm, (d) 50 cm.

Figure 10.

Temporal validation results of BKA-CNN at different depths in the farmland site: (a) 3 cm, (b) 10 cm, (c) 20 cm, (d) 50 cm.

Overall, as presented in Figure 9, the BKA-CNN combined with MS + SAR performed well at the grassland site, with R2 ranging from 0.732 to 0.785, RMSE ranging from 0.029 to 0.032, and MAE ranging from 0.025 to 0.03. The highest accuracy was obtained at the 10 cm depth, where R2 was 0.785, RMSE was 0.027 m3/m3, and MAE was 0.025 m3/m3. However, as depicted in Figure 10, the model performed relatively worse at the farmland site, with R2 ranging from 0.706 to 0.758, RMSE ranging from 0.028 m3/m3 to 0.032 m3/m3, and MAE ranging from 0.023 m3/m3 to 0.028 m3/m3. The highest accuracy at the farmland site was obtained at the 20 cm depth, where R2 was 0.758, RMSE was 0.028 m3/m3, and MAE was 0.027 m3/m3. Specifically, the R2 at the grassland site was higher by 0.027, the RMSE was lower by 0.001 m3/m3, and the MAE was lower by 0.002 m3/m3, compared to the farmland site. The higher accuracy at the grassland site may be due to the shorter height and root system of the grassland compared to the farmland, which results in less influence of vegetation on the radar backscatter coefficient, thus contributing to better estimation performance by the model, especially in the surface layer. The lower accuracy at the farmland site may be due to several factors, including irrigation causing increased errors in the model, uneven irrigation within a pixel leading to errors in the in-situ measured SM, and differences in crop phenology that affect the radar signal’s interaction with the soil, further complicating the moisture estimation [72].

Overall, the BKA-CNN proposed in this study demonstrates strong generalization ability and robustness in predicting at sites not involved in training. This is due to the fact that during the training procedure, the model has thoroughly grasped the intricate relationship existing between the input parameters and the multi-layer SM. Meanwhile, the sites whose characteristics were unknown prior to the analysis possess vegetation cover that is comparable to that which was present during the model’s training phase. This similarity enables the model to more accurately forecast SM at various depth levels.

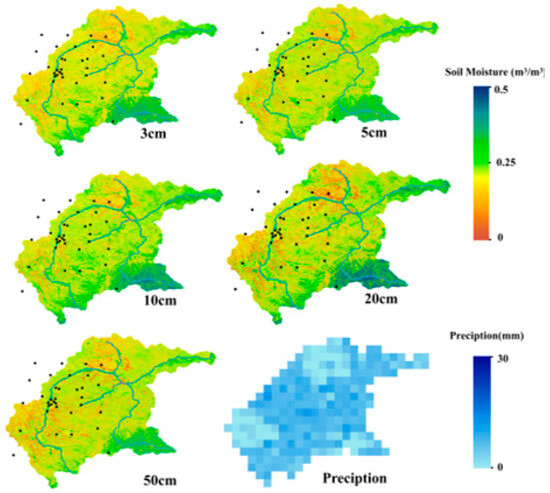

4.6. Spatial Mapping

In order to delve deeper into the spatial performance of the BKA-CNN model that has been proposed, this study generated a high-resolution (10 m) five-layer SM spatial distribution map for the Shandian River Basin on 23 May 2019, based on BKA-CNN. Figure 11 shows the soil moisture distribution at different depths and the cumulative precipitation distribution of the previous week, i.e., 17–23 May 2019. The model captured the continuous spatial characteristics of SM, demonstrating its effectiveness in spatial applications. Horizontally, the central-southern and northwestern parts of the Shandian River Basin are relatively moist, while the northern and southwestern parts are relatively dry due to less precipitation.

Figure 11.

High-resolution (10 m) SM map of five layers in the Shandian River Basin on 23 May 2019, along with the cumulative precipitation map for the period 17–23 May 2019 (one week).

In the vertical direction of the Shandian River Basin, SM increases with depth, until at the 20 cm depth, SM gradually shows a trend of lower values, especially in the northern and southwestern regions, which are relatively arid. This is likely due to the shorter hydrological scale of soils at different depths in the vertical direction, leading to a weakened relationship between surface SM and RZSM [73]. As depth increases, the degree of aridity is alleviated, which is attributed to the persistence of RZSM [6]. Notably, along the vertical profile in the southeastern portion of the study zone, soil moisture demonstrates a consistent upward trend starting at the ground surface and extending to the root zone, before a deceleration emerges at 50 cm. This trend varies from that at other horizontal locations. On the one hand, this phenomenon likely stems from the vertical variability in the physical structure of the soil within these two kinds of regions, leading to different hydrological properties of different soil layers. On the other hand, the vegetation cover types are different, with the southeastern part mainly forest, while other parts are mainly grasslands and farmlands, which leads to significant differences in root distribution in the vertical direction. These two factors exert a profound influence on the dynamic operation of SM [74].

5. Discussion

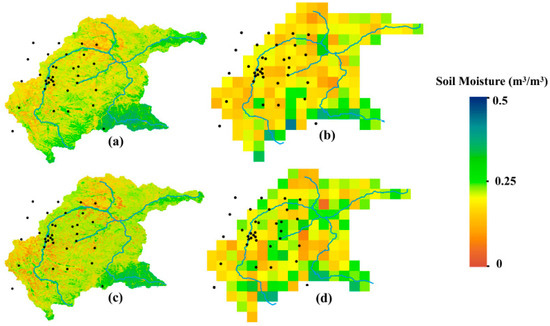

5.1. Comparison with SMAP Data

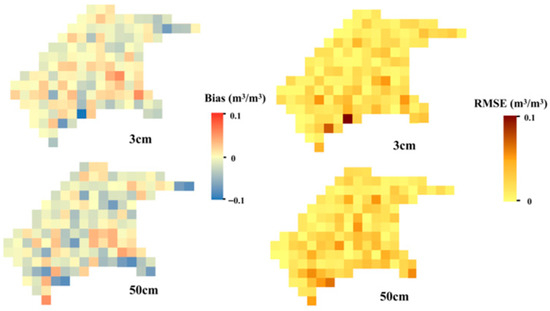

To further investigate the capability of the proposed method in spatially capturing the SM heterogeneity of the Shandian River Basin, we compared the SM maps generated by BKA-CNN with the SMAP L4 product. The benchmark SMAP Level-4 Soil Moisture product (SMAP L4_SM), disseminated by NASA, is employed for comparative purposes. Characterized by a spatial resolution of 9 km and a temporal resolution of 3 h, it provides volumetric soil moisture estimates for two distinct depth intervals: 0–5 cm (surface layer) and 0–100 cm (root zone). Generated through the assimilation of SMAP L-band brightness temperature observations into the GEOS-5 land surface model, this product has been extensively adopted for global-scale soil moisture monitoring. Since the SM measurement depths at SMN-SDR stations are 3 cm, 5 cm, 10 cm, 20 cm, and 50 cm, respectively, while the SMAP L4 SM product depths are 0–5 cm and 0–100 cm, for a better comparison between the two datasets, we selected the SM inversion results at 3 cm and 50 cm to compare with the SMAP L4 0–5 cm and 0–100 cm data products, respectively. The comparison results are shown in Figure 12. Meanwhile, we used the regional weighted average method to resample the generated 10 m-resolution 3 cm and 50 cm depth soil moisture maps to the scale of SMAP products, i.e., 9 km. We then calculated the bias and RMSE between the resampled soil moisture maps and the SMAP products to identify representative errors, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Comparison between BKA-CNN surface and root zone SM data products and SMAP L4 data: (a) Generated 3 cm SM product, (b) SMAP L4 0–5 cm data, (c) Generated 50 cm SM product, (d) SMAP L4 0–100 cm data.

Figure 13.

Graphs of Bias and RMSE between the 3 cm and 50 cm SM maps generated by BKA-CNN and the SMAP surface and root zone SM maps.

At the soil surface, the SMAP product indicates that most areas around the station distribution are relatively arid, which aligns well with the SM inversion results of this study. However, it is noteworthy that the SM data generated in this study captures more detailed spatial variations of SM, demonstrating the significant advantage of the proposed method in capturing the spatial heterogeneity of SM in the study area. As depth increases, the SM values from the SMAP product gradually rise, but in arid regions such as the northern and southwestern parts of the basin, an opposite trend is observed—these areas become drier in the root zone, which is consistent with our RZSM inversion results. Similarly, the RZSM maps generated in this study exhibit more detailed spatial variations of SM compared to the SMAP data.

As can be seen from Figure 13, most of the inversion results of this study maintain small errors compared with the SMAP products, especially in the areas where soil moisture stations are distributed, which can maintain low bias and RMSE. However, in forest-covered areas, particularly in the southern, southeastern, and northeastern parts of the study area, relatively high errors exist. This discrepancy arises due to the lack of station data in these regions and the predominance of forest vegetation, which significantly impacts model accuracy. In addition, the high vegetation optical depth (VOD) in forests can interfere with the propagation of electromagnetic waves, further increasing model errors. Future work should consider using longer electromagnetic wave bands (e.g., the L-band) as model inputs to reduce the impact of forest VOD, and incorporating more forest-based stations as the target values for the model.

5.2. Advantages and Limitations of the BKA-CNN Model

This study investigates the advantages of integrating SAR and MS data in multi-layer SM inversion using a deep learning CNN model, while employing BKA to optimize the model’s hyperparameters, ultimately constructing the BKA-CNN model for multi-layer SM inversion. Experimental results demonstrate that BKA-CNN outperforms other models, effectively learning the relationship between input parameters and multi-layer SM. Furthermore, its temporal validation accuracy remains high across sites with different vegetation types. It highlights its capability in capturing SM temporal variations and also demonstrates strong generalization ability and robustness. In terms of spatial resolution, compared to SMAP products, BKA-CNN successfully retrieves detailed spatial variations of multi-layer SM, indicating its significant advantages in high-resolution multi-layer SM inversion.

However, the BKA-CNN model also has certain limitations. Due to the constraints of station distribution, the model can only learn the relationship between input parameters and SM under identical or similar environmental conditions. Furthermore, the spatiotemporal constraints of the study area, the model is susceptible to overfitting, which may lead to divergent performance when extrapolated to regions or landscapes with distinct characteristics. Compounding this issue, the uneven distribution of in-situ SM observations induces a systematic underestimation of high values. It is therefore recommended that subsequent investigations incorporate additional representative in-situ soil-moisture stations as data sources to enhance and validate the model’s generalizability and stability. Moreover, model accuracy exhibits an initial increase followed by a pronounced decline with depth. This trend can be attributed to two principal factors. First, as shown in Table 4, as the depth increases, the correlation between the input variables and soil moisture at greater depths decreases due to the limitations of C-band penetration depth and the reduced sensitivity of multispectral data, such as the SWIR band, to water absorption. Therefore, it is advisable to consider using the more penetrating L-band for future research. Second, as shown in Table 4, the vertical autocorrelation of soil moisture decays markedly with depth, leading to a gradual attenuation of inter-layer correlations as the vertical separation increases, thereby compounding estimation errors in deeper strata. Future studies could incorporate soil properties, elevation, and other information highly correlated with the root zone into the model [6]. The estimation frequency of the model is strictly constrained by the revisit cycles of Sentinel-1/2; consequently, soil-moisture retrieval becomes infeasible during periods of limited remote-sensing data availability. In the future, consideration may be given to using time-series prediction models (such as ConvLSTM) or combining land surface models with data assimilation to fill the temporal gaps.

6. Conclusions

In the course of this research, we integrated remote sensing data derived from MS and SAR sources and utilized them as inputs for machine learning algorithms, with the aim of estimating the multi-layer SM within the Shandian River Basin. This approach has yielded the subsequent three primary conclusions:

- (1)

- Model and data fusion superiority. MS + SAR consistently outperforms single-source inputs, and a CNN optimized with BKA provides the most stable mapping of vertical SM structure across layers.

- (2)

- Depth of maximum gain. The fusion signal delivers its strongest incremental benefit around 10 cm, indicating this depth is the most informative layer for profile retrieval and downstream decisions.

- (3)

- Vegetation-dependent performance. Retrieval skill is modulated by land cover: grassland conditions are generally more favorable than cropland, consistent with the effects of irrigation timing and crop phenology on the radar–optical response.

Therefore, given the 10 cm layer’s primacy, scheduling observations to capture this layer’s dynamics is most actionable: (i) prioritize MS + SAR co-occurring windows when possible; (ii) in cropland, avoid immediate post-irrigation periods and account for key phenological stages to reduce signal confounding; and (iii) use fusion-based maps as triggers for field verification and targeted irrigation adjustments.

In summary, the BKA-CNN model proposed in this study effectively enhances the estimation precision of multi-layer SM via integrating SAR and MS data, and meanwhile demonstrates remarkable stability. It has potential application value in the fields of ecological protection and agricultural water resource management. However, the model is subject to several limitations. The restricted spatiotemporal scope of the present study renders its transferability to other contexts yet to be rigorously validated. Furthermore, the scarcity of in-situ measurements at high soil-moisture levels engenders systematic underestimation. It is therefore imperative that future research expand the training and validation dataset to encompass additional stations distributed across diverse regions, vegetation covers, and—crucially—uniformly spanning the full range of soil-moisture values, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness and stability.

Author Contributions

M.J. and X.L. contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors. Conceptualization, M.J., X.L. and J.W.; methodology, M.J. and X.L.; validation, R.T., X.S. and Y.B.; investigation, M.J., X.L., X.S. and J.W.; resources, T.Z. and R.T.; writing-original draft preparation, M.J.; writing-review and editing, M.J., X.L., J.W. and T.Z.; visualization, X.S. and Y.B.; supervision, X.L. and J.W.; project administration, T.Z. and R.T.; funding acquisition, X.S. and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research endeavor supported by the Innovation Base for Natural Resources Monitoring Technology in the Lower Reaches of Yongding River, Geological Society of China (KY02202501), the Central government guide local science and technology development fund project Science and technology innovation base project (246Z7401G), the Open Fund of State Key Laboratory of Remote Sensing Science (Grant No. OFSLRSS202303), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFB3900104) and the Graduate Innovation Funding Project of North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering (YKY-2024-91).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions and key supporting data presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Chen, B.; Fan, H.; Huang, J.; Zhao, H. The Potential Use of Multi-Band SAR Data for Soil Moisture Retrieval over Bare Agricultural Areas: Hebei, China. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Magagi, R.; Goita, K.; Jagdhuber, T. Refining a Polarimetric Decomposition of Multi-Angular UAVSAR Time Series for Soil Moisture Retrieval Over Low and High Vegetated Agricultural Fields. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 1431–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Shi, J.; Lv, L.; Xu, H.; Chen, D.; Cui, Q.; Jackson, T.J.; Yan, G.; Jia, L.; Chen, L.; et al. Soil moisture experiment in the Luan River supporting new satellite mission opportunities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111680. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, P.; Song, X.; Duan, S.B.; Li, Z.L. A practical algorithm for estimating surface soil moisture using combined optical and thermal infrared data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 52, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Zribi, M.; Belaud, G.; Cheviron, B.; Courault, D.; Charron, F. Soil moisture retrieval over irrigated grassland using X-band SAR data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 176, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, L.; Mishra, A.K. Multi-layer high-resolution soil moisture estimation using machine learning over the United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Ines, A.V.; Das, N.N.; Khedun, C.P.; Singh, V.P.; Sivakumar, B.; Hansen, J.W. Anatomy of a local-scale drought: Application of assimilated remote sensing products, crop model, and statistical methods to an agricultural drought study. J. Hydrol. 2015, 526, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Campbell, C.S.; Hopmans, J.W.; Hornbuckle, B.K.; Jones, S.B.; Knight, R.; Ogden, F.; Selker, J.; Wendroth, O. Soil Moisture Measurement for Ecological and Hydrological Watershed-Scale Observatories: A Review. Vadose Zone J. 2008, 7, 358–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noborio, K. Measurement of Soil Water Content and Electrical Conductivity by Time Domain Reflectometry: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2001, 31, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreda, M.; Shuttleworth, W.J.; Zeng, X.; Zweck, C.; Desilets, D.; Franz, T.; Rosolem, R. COSMOS: The COsmic-Ray Soil Moisture Observing System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 4079–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbüchel, I.; Güntner, A.; Blume, T. Use of Cosmic-Ray Neutron Sensors for Soil Moisture Monitoring in Forests. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 20, 1269–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocca, L.; Morbidelli, R.; Melone, F.; Moramarco, T. Soil moisture spatial variability in experimental areas of central Italy. J. Hydrol. 2007, 333, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, L.; Chawla, I.; Mishra, A.K. A review of remote sensing applications in agriculture for food security: Crop growth and yield, irrigation, and crop losses. J. Hydrol. 2020, 586, 124905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Babaeian, E.; Tuller, M.; Jones, S.B. The optical trapezoid model: A novel approach to remote sensing of soil moisture applied to Sentinel-2 and Landsat-8 observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 198, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Sadeghi, M.; Jones, S.B.; Montzka, C.; Vereecken, H.; Tuller, M. Ground, Proximal, and Satellite Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 530–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, V.L.; De Bruin, S.; Schaepman, M.E.; Mayr, T.R. The use of remote sensing in soil and terrain mapping—A review. Geoderma 2011, 162, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A modified soil adjusted vegetation index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agutu, N.O.; Awange, J.L.; Zerihun, A.; Ndehedehe, C.E.; Kuhn, M.; Fukuda, Y. Assessing multi-satellite remote sensing reanalysis and land surface models products in characterizing agricultural drought in East Africa. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaeian, E.; Paheding, S.; Siddique, N.; Devabhaktuni, V.K.; Tuller, M. Estimation of root zone soil moisture from ground and remotely sensed soil information with multisensor data fusion and automated machine learning. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 260, 112434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, F.N. Application of vegetation index and brightness temperature for drought detection. Adv. Space Res. 1995, 15, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Rowen, L.C.; Offieid, T.W. Application of thermal modeling in the geologic interpretation of IR image. Remote Sens. Environ. 1971, 21, 2017–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Tian, G.L. The Application of Thermal Inertia Method the Monitoring of Soil Moisture of North China Plain Based on NOAA-AVHRR Data. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 1, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Peng, Y.; Wang, G.; Hu, Y. Improving Estimation of Soil Moisture Content Using a Modified Soil Thermal Inertia Model. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, R.; Nobahar, M.; Alzeghoul, O.E.; Khan, S.; La Cour, I.; Amini, F. Near-Surface Soil Moisture Characterization in Mississippi’s Highway Slopes Using Machine Learning Methods and UAV-Captured Infrared and Optical Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandholt, I.; Rasmussen, K.; Andersen, J. A simple interpretation of the surface temperature/vegetation index space for assessment of surface moisture status. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 79, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akuraju, V.R.; Ryu, D.; George, B. Estimation of Root-Zone Soil Moisture Using Crop Water Stress Index (CWSI) in Agricultural Fields. GISci. Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Li, B.; Jiao, X.; Huang, X.; Fan, H.; Lin, R.; Liu, K. Using multimodal remote sensing data to estimate regional-scale soil moisture content: A case study of Beijing, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, M.; Shafian, S.; Frame, W. Depth-specific soil moisture estimation in vegetated corn fields using a canopy-informed model: A fusion of RGB-thermal drone data and machine learning. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Shi, J.; Entekhabi, D.; Jackson, T.J.; Hu, L.; Peng, Z.; Kang, C.S. Retrievals of soil moisture and vegetation optical depth using a multi-channel collaborative algorithm. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 257, 112321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entekhabi, D.; Njoku, E.G.; O’neill, P.E.; Kellogg, K.H.; Crow, W.T.; Edelstein, W.N.; Entin, J.K.; Goodman, S.D.; Jackson, T.J.; Johnson, J.; et al. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Mission. Proc. IEEE 2010, 98, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, T.; Shi, J.; Hu, L.; Rodríguez-Fernández, N.J.; Wigneron, J.P.; Wei, Z. First mapping of polarization-dependent vegetation optical depth and soil moisture from SMAP L-band radiometry. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 302, 113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Hahn, S.; Kidd, R.; Melzer, T.; Bartalis, Z.; Hasenauer, S.; Figa-Saldaña, J.; De Rosnay, P.; Jann, A.; Schneider, S.; et al. The ASCAT Soil Moisture Product: A Review of its Specifications, Validation Results, and Emerging Applications. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, Y.H.; Waldteufel, P.; Wigneron, J.P.; Martinuzzi, J.A.M.J.; Font, J.; Berger, M. Soil moisture retrieval from space: The Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Zhao, T.; Jia, L.; Cosh, M.H.; Shi, J.; Peng, Z.; Wigneron, J.P. A multi-temporal and multi-angular approach for systematically retrieving soil moisture and vegetation optical depth from SMOS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 280, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, E.H.; Yang, L.; Huang, J. A Convolutional Neural Network Algorithm for Soil Moisture Prediction from Sentinel-1 SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cui, N.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Jin, X.; Gong, D.; Xing, L.; Zhao, L.; Wen, S.; Yang, Y. Estimating soil moisture content in citrus orchards using multi-temporal sentinel-1A data-based LSTM and PSO-LSTM models. J. Hydrol. 2024, 637, 131336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, X.; García-García, A.; Schmidt, T.; Samaniego, L.; Peng, J. A Sentinel-1 SAR-based global 1-km resolution soil moisture data product: Algorithm and preliminary assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 318, 114579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Dai, J.; Jin, J.; Yuan, S.; Xiong, Z.; Walker, J.P. Are the Current Expectations for SAR Remote Sensing of Soil Moisture Using Machine Learning Overoptimistic? IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 4501815. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, M.C.; Ulaby, F.T. Preliminary evaluation of the SIR-B response to soil moisture, surface roughness, and crop canopy co Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Images for Operational Soil Moisture Mapping at High Spatial ver. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1986, GE-24, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Corti, T.; Davin, E.L.; Hirschi, M.; Jaeger, E.B.; Lehner, I.; Orlowsky, B.; Teuling, A.J. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 2010, 99, 125–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Sarabandi, K.; Ulaby, F.T. An empirical model and an inversion technique for radar scattering from bare soil surfaces. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska-Zielinska, K.; Musial, J.; Malinska, A.; Budzynska, M.; Gurdak, R.; Kiryla, W.; Bartold, M.; Grzybowski, P. Soil Moisture in the Biebrza Wetlands Retrieved from Sentinel-1 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, T.; Shi, J.; Wang, H.; Ji, D.; Yao, P.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, X.; Xu, X. 1-km soil moisture retrieval using multi-temporal dual-channel SAR data from Sentinel-1 A/B satellites in a semi-arid watershed. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 131336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, J. Soil Moisture Retrieval in Farmland Areas with Sentinel Multi-Source Data Based on Regression Convolutional Neural Networks. Sensors 2021, 21, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Yang, H.; Li, N. Inversion of Soil Moisture in Wheat Farmlands Using the RIME-CNN-SVR Model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.T.; Arenas-Castro, S.; Punalekar, S.M.; Cunha, M.; Mendes, I.; Giamberini, M.; da Costa, E.M.; Fava, F.; Lucas, R. Remote sensing of vegetation and soil moisture content in Atlantic humid mountains with Sentinel-1 and 2 satellite sensor data. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, C.; Nolet, C.; Pezij, M.; van der Ploeg, M. Root zone soil moisture estimation with Random Forest. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 125840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Jia, X.; Wang, J.; Shao, M. Prediction of Deep Soil Water Content (0–5 m) with in-Situ and Remote Sensing Data. Catena 2023, 222, 106852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Yuan, X.; Ji, P. The important role of reliable land surface model simulation in high-resolution multi-source soil moisture data fusion by machine learning. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Whiting, M.; Chen, F.; Sun, Z.; Song, K.; Wang, Q. Convolutional neural network model for soil moisture prediction and its transferability analysis based on laboratory Vis-NIR spectral data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazi, E.H.; Samak, A.A.; Yang, L.; Huang, R.; Huang, J. Prediction of Soil Moisture Content from Sentinel-2 Images Using Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Agronomy 2023, 13, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Soil Moisture Network (ISMN). Available online: https://ismn.earth/en/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Zheng, J.; Zhao, T.; Lü, H.; Shi, J.; Cosh, M.H.; Ji, D.; Jiang, L.; Cui, Q.; Lu, H.; Yang, K.; et al. Assessment of 24 soil moisture datasets using a new in situ network in the Shandian River Basin of China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 271, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.M.; Huang, J.F.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, X.Z. New vegetation index and its application in estimating leaf area index of rice. Chin J Rice Sci. 2007, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R. Normalized difference chlorophyll index: A novel model for remote estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in turbid productive waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Cao, W.; Luo, W.; Dai, T.; Zhu, Y. Monitoring Leaf Nitrogen Status in Rice with Canopy Spectral Reflectance. Agron. J. 2004, 96, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Berjón, A.; López-Lozano, R.; Miller, J.R.; Martín, P.; Cachorro, V.; González, M.R.; De Frutos, A. Assessing vineyard condition with hyperspectral indices: Leaf and canopy reflectance simulation in a row-structured discontinuous canopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 99, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Baret, F.; Filella, I. Semi-empirical indices to assess carotenoids/chlorophyll alpha ratio from leaf spectral reflectance. Photosynthetica 1995, 31, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P.; Roberts, D.A.; Kyriakidis, P.C. A VARI-based relative greenness from MODIS data for computing the Fire Potential Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]