A Spreading-Stem-Growth Mutation in Lolium perenne: A New Genetic Resource for Turf Phenotypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Colchicine Treatment and VIROIZ Mutant Discovery

2.2. Plant Material and Field Evaluation of F1, F2, and S1 Generations

2.3. Divergent Selection for Axillary Tiller in the Greenhouse Pot Experiment

2.4. Candidate Gene Amplification, Sequencing, and Analysis

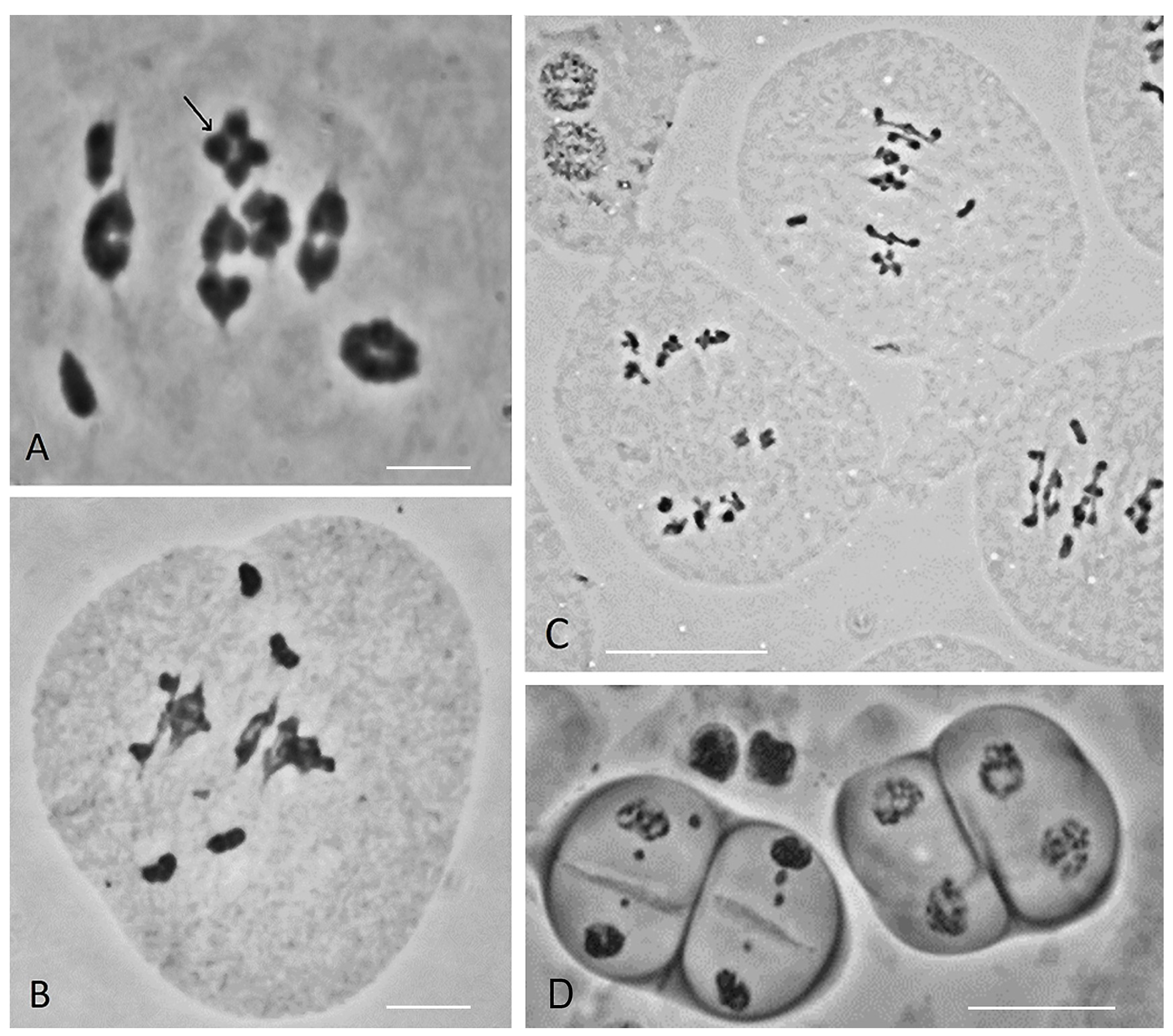

2.5. Chromosome Pairing Analysis in Meiosis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

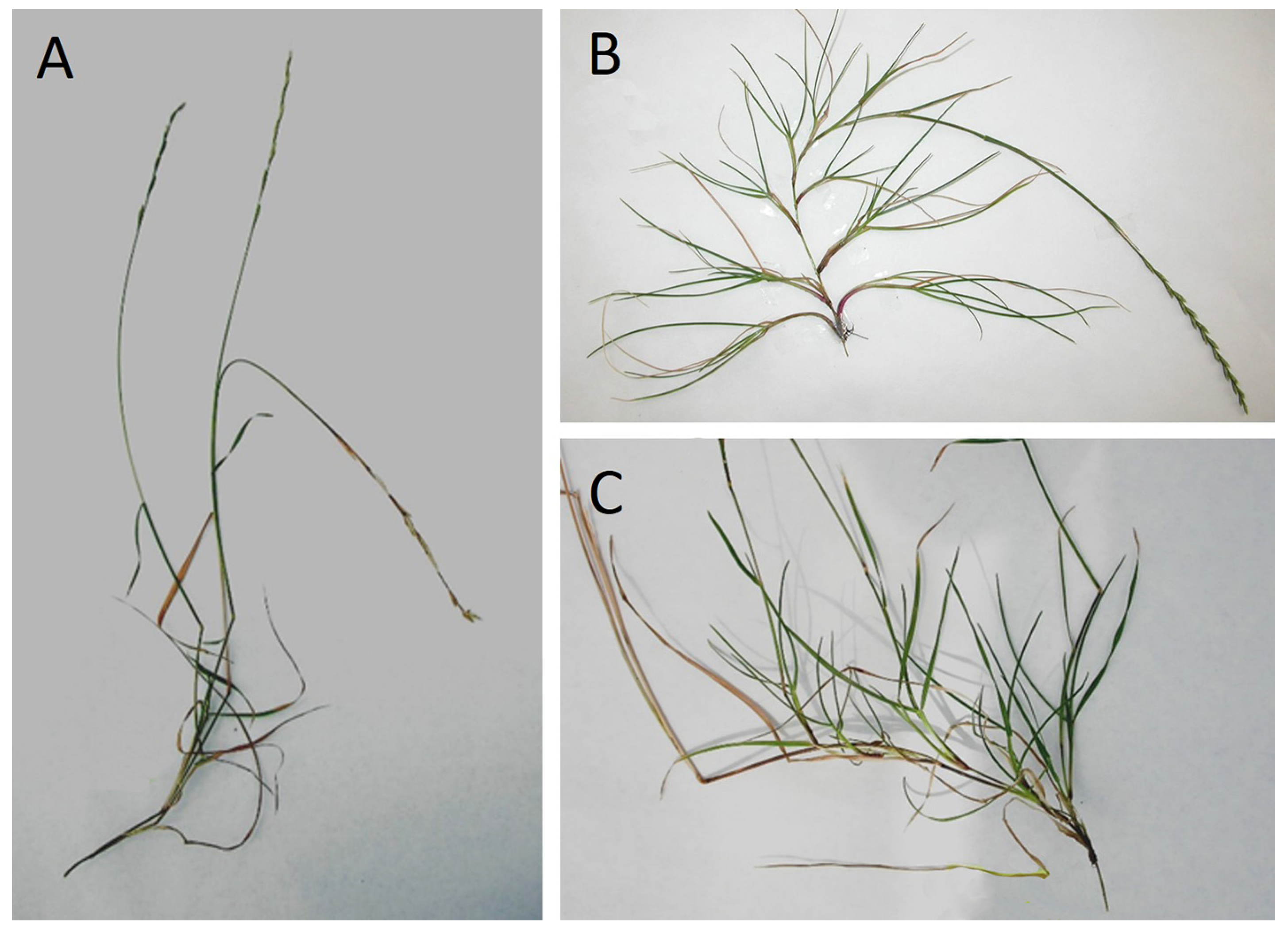

3.1. VIROIZ Morphotype

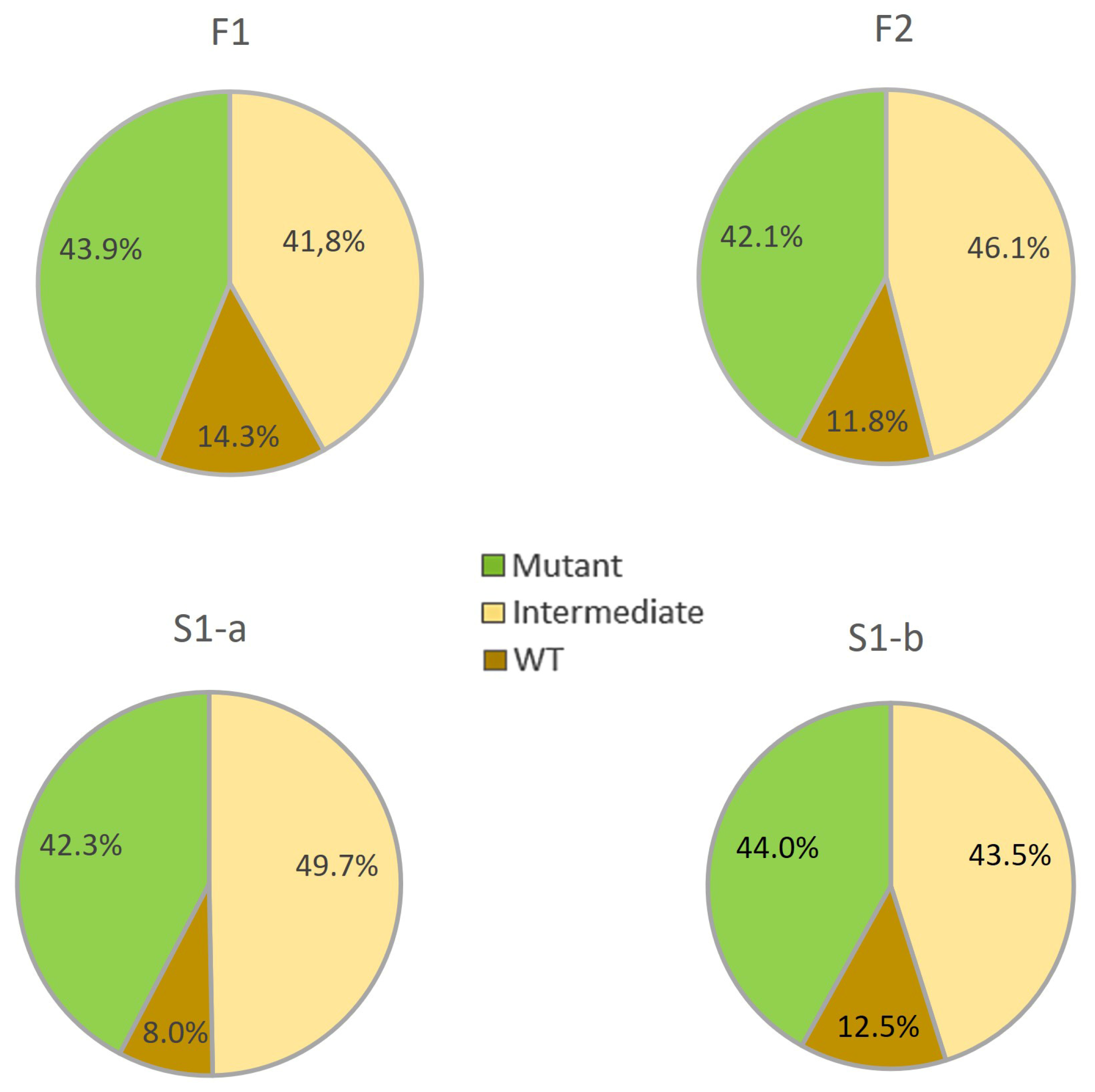

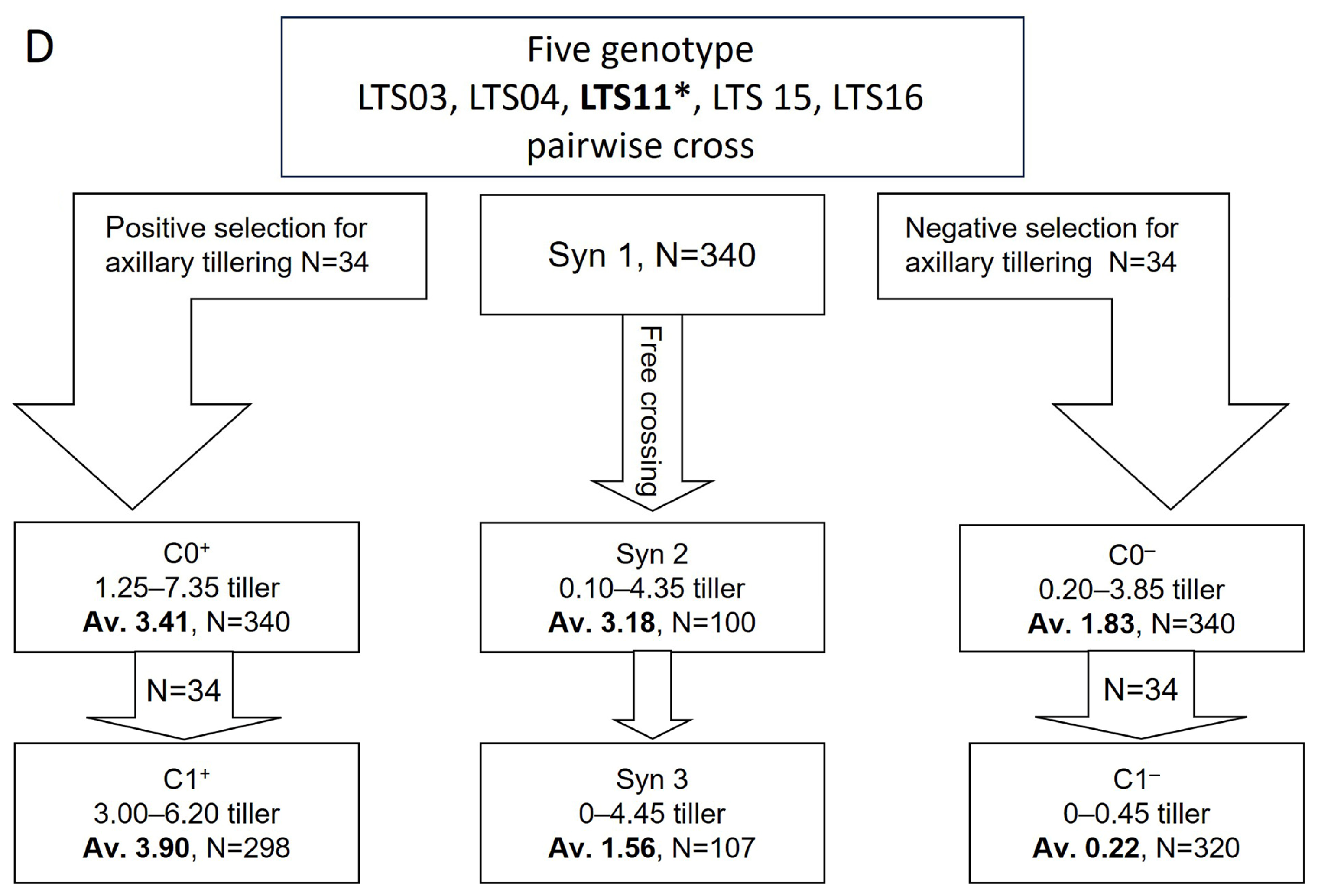

3.2. The Inheritance of the Spreading Growth Habit Evaluated in Field and Pot Experiments

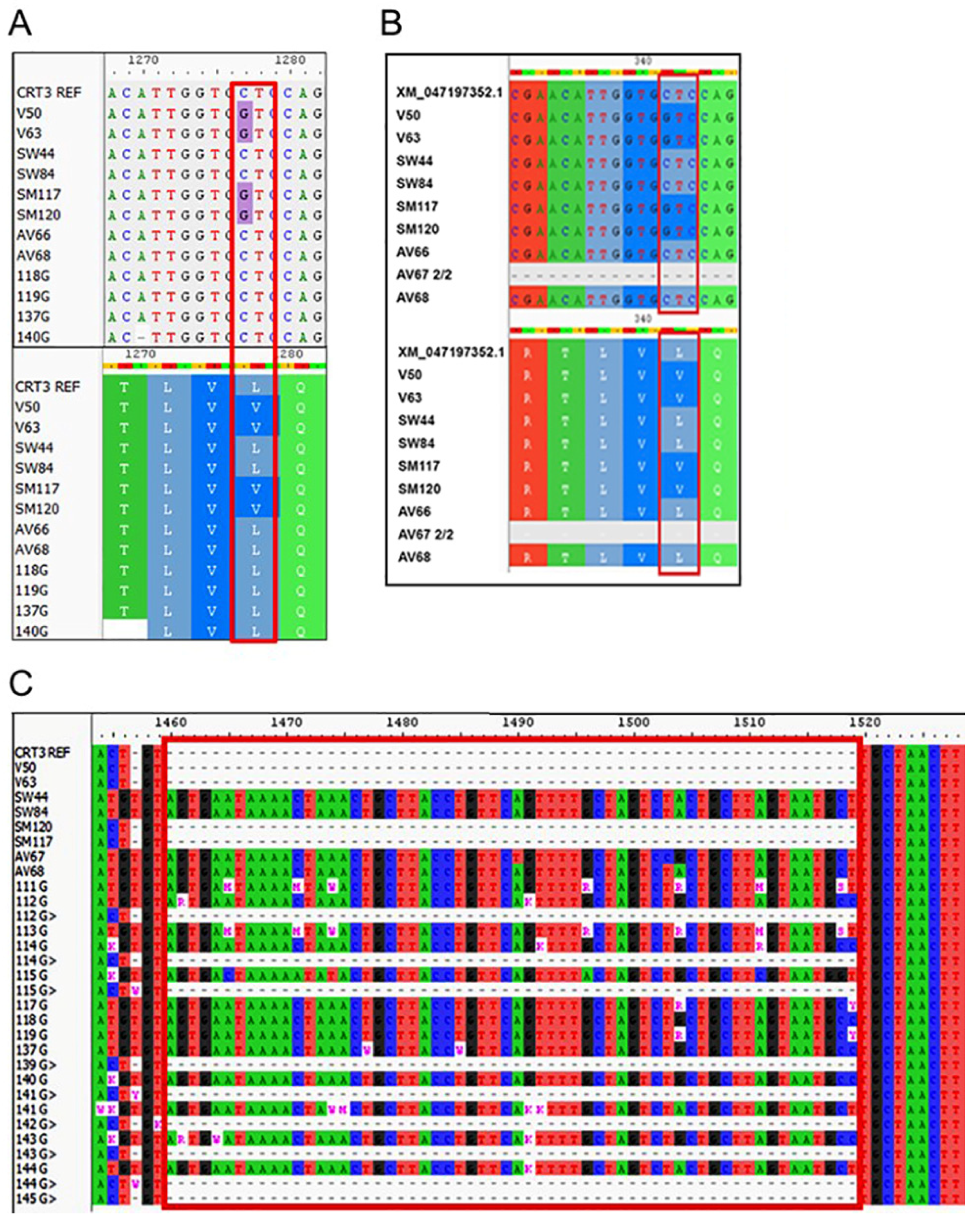

3.3. Mutation Analysis of Candidate Genes Implicated in Shoot Morphogenesis

3.4. Chromosome Pairing Irregularities in Meiosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkins, P.W. Breeding Perennial Ryegrass for Agriculture. Euphytica 1991, 52, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfourier, F.; Charmet, G.; Ravel, C. Genetic Differentiation within and between Natural Populations of Perennial and Annual Ryegrass (Lolium perenne and L. rigidum). Heredity 1998, 81, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, P.W.; Humphreys, M.O. Progress in Breeding Perennial Forage Grasses for Temperate Agriculture. J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 140, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y. Phenotypic and Genotypic Diversity for Drought Tolerance among and within Perennial Ryegrass Accessions. HortScience 2015, 50, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, N.F.; Lovatt, A.; Hegarty, M.; Lovatt, A.; Skøt, K.P.; Kelly, R.; Blackmore, T.; Thorogood, D.; King, R.D.; Armstead, I.; et al. Implementation of Genomic Prediction in Lolium perenne (L.) Breeding Populations. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaškūnė, K.; Aleliūnas, A.; Statkevičiūtė, G.; Kemešytė, V.; Studer, B.; Yates, S. Genome-Wide Association Study to Identify Candidate Loci for Biomass Formation under Water Deficit in Perennial Ryegrass. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 570204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toporan, S.; Samfira, I. Review on the Genetic and Biochemical Characterization of Lolium perenne Species. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 53, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Sampoux, J.P.; Baudouin, P.; Bayle, B.; Beguier, V.; Bourdon, P.; Chosson, J.F.; de Bruijn, K.; Deneufbourg, F.; Galbrun, C.; Ghesquière, M.; et al. Breeding Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) for Turf Usage: An Assessment of Genetic Improvements in Cultivars Released in Europe, 1974–2004. Grass Forage Sci. 2012, 68, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornaro, C.; Menegon, A.; Macolino, S. Stolon Development in Four Turf-Type Perennial Ryegrass Cultivars. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 2159–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, E.E. A Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Lolium, Technical Bulletin; United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1968; No. 171644.

- Langer, R.H.M. How Grasses Grow; Edward Arnold Publishers Limited: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kydd, D.D. The Effect of Intensive Sheep Stocking over a Five-Year Period on the Development and Production of the Sward. J. Br. Grassl. Soc. 1966, 21, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, P. Stoloniferous Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) in Northern Ireland Paddocks. Rec. Agric. Res. Minist. Agric. N. Irel. 1971, 19, 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, W.; Pandey, K.K.; Gray, Y.S.; Couchman, P.K. Observations on the Spread of Perennial Ryegrass by Stolons in a Lawn. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 1979, 22, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wipff, J.K.; Singh, D. Lolium perenne subsp. Stoloniferum; Perennial Ryegrass with Determinate Stolons. U.S. Plant Patent No. US8927804B2, 6 January 2015. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Masin, R.; Macolino, S. Seedling Emergence and Establishment of Annual Bluegrass (Poa annua) in Turfgrasses of Traditional and Creeping Perennial Ryegrass Cultivars. Weed Technol. 2016, 30, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.A.; Brewer, P.B.; Beveridge, C.A. Strigolactones: Discovery of the Elusive Shoot Branching Hormone. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domagalska, M.A.; Leyser, O. Signal Integration in the Control of Shoot Branching. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 211–221. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/nrm3088 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.A.; de Saint Germain, A.; Rameau, C.; Beveridge, C.A. Dynamics of Strigolactone Function and Shoot Branching Responses in Pisum sativum. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dun, E.A.; Brewer, P.B.; Gillam, E.M.J.; Beveridge, C.A. Strigolactones and Shoot Branching: What Is the Real Hormone and How Does It Work? Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongaro, V.; Leyser, O. Hormonal Control of Shoot Branching. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, C.A.; Dun, E.A.; Rameau, C. Pea Has Its Tendrils in Branching Discoveries Spanning a Century from Auxin to Strigolactones. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, Y.; Gui, S.; Wang, Y. Regulation of Tillering and Panicle Branching in Rice and Wheat. J. Genet. Genom. 2025, 52, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakinskienė, I. Creeping Stem and Barren Inflorescence: A New Mutation in Lolium perenne “VIROIZ”. In Recent Advances in Genetics and Breeding of the Grasses; Institute of Plant Genetics: Poznan, Poland, 2005; pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, A.; Jones, R.N. Heritable Nature of Colchicine-Induced Variation in Diploid Lolium perenne. Heredity 1989, 62, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazauskas, G.; Pašakinskienė, I.; Asp, T.; Lübberstedt, T. Nucleotide Diversity and Linkage Disequilibrium in Five Lolium perenne Genes with Putative Role in Shoot Morphology. Plant Sci. 2010, 179, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, S.D. Brassinosteroid Signal Transduction: From Receptor Kinase Activation to Transcriptional Networks Regulating Plant Development. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.; Chu, C. Functional Specificities of Brassinosteroid and Potential Utilization for Crop Improvement. Trends Plant Sci. 2018, 23, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bioassays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakinskienė, I. Culture of Embryos and Shoot Tips for Chromosome Doubling in Lolium perenne and Sterile Hybrids between Lolium and Festuca. Plant Breed. 2000, 119, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posselt, U.K.; Barre, P.; Brazauskas, G.; Turner, L.B. Comparative Analysis of Genetic Similarity between Perennial Ryegrass Genotypes Investigated with AFLPs, SSRs, RAPDs, and ISSRs. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2006, 42, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.B.; Andersen, J.R.; Frei, U.; Xing, Y.; Taylor, C.; Holm, P.B.; Lübberstedt, T. QTL Mapping of Vernalization Response in Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) Reveals Co-Location with an Orthologue of Wheat VRN1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 110, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A Fast and Lightweight Alignment Viewer and Editor for Large Datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, B.; Yu, T.; Qi, J.; Meyerowitz, E.M.; Jiao, Y. The Stem Cell Niche in Leaf Axils Is Established by Auxin and Cytokinin in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 26, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, H.; Readshaw, A.; Kania, U.; de Jong, M.; Pasam, R.K.; McCulloch, H.; Ward, S.; Shenhav, L.; Forsyth, E.; Leyser, O. Artificial Selection Reveals Complex Genetic Architecture of Shoot Branching and Its Response to Nitrate Supply in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2023, 19, e1010863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Khourchi, S.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Delaplace, P. Unlocking the Multifaceted Mechanisms of Bud Outgrowth: Advances in Understanding Shoot Branching. Plants 2023, 12, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Hong, Z.; Su, W.; Li, J. A Plant-Specific Calreticulin Is a Key Retention Factor for a Defective Brassinosteroid Receptor in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13612–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; He, Y. Roles of Brassinosteroids in Plant Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Li, J. Regulation of Three Key Kinases of Brassinosteroid Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Dong, H.; Yin, Y.; Song, X.; Gu, X.; Sang, K.; Zhou, J.; Shi, K.; Zhou, Y.; Foyer, C.H.; et al. Brassinosteroid Signaling Integrates Multiple Pathways to Release Apical Dominance in Tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2004384118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelin, L.; Mutwil, M.; Sommarin, M.; Persson, S. Diverging Functions among Calreticulin Isoforms in Higher Plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, T.; Yang, T.; Wang, B.; Yang, H.; Tuerdiyusufu, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, Q. Comprehensive Genomic Characterization and Expression Analysis of Calreticulin Gene Family in Tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1397765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluška, F.; Šamaj, J.; Napier, R.; Volkmann, D. Maize Calreticulin Localizes Preferentially to Plasmodesmata in Root Apex. Plant J. 1999, 19, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyser, O. The Control of Shoot Branching: An Example of Plant Information Processing. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, C.A.; Kyozuka, J. New Genes in Strigolactone-Related Shoot Branching Pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W.; Sui, N.; Zhu, J. Biological Functions of Strigolactones and Their Crosstalk with Other Phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 821563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Comai, L.; Henry, I.M. Chromoanagenesis from Radiation-Induced Genome Damage in Populus. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Protein Function | Full-Length Genomic DNA, bp | Gene Coverage in VIROIZ, bp (%) | Indel Allelic Variants | SNP Allelic Variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Status in VIROIZ | No. | Unique in VIROIZ | ||||

| IAA1 | Auxin-inducible transcriptional repressor | 2552 | 1821 (71.4) | - | - | 7 | N* |

| BRI1 | Receptor in brassinosteroids signaling | 3837 | 1931 (50.3) | - | - | 6 | N |

| CRT3 | ER chaperon for folding of BR receptors | 4396 | 2584 (58.8) | 1378_1440 indel, in3 | Homozygote 62 bp (−/−) deletion | 7 | c.1277C>G (p.L427V) |

| D27 † | Strigolactone biosynthesis | 2374 | 2138 (90.0) | g.463_467, in2; g.878_884, in3 | Homozygote 5 bp insertion (+/+); Homozygote 7 bp deletion (−/−) | 5 | N |

| CCD8 † | 3752 | 1572 (41.9) | g.3054_3072 indel, in3 | Homozygote for 19 bp deletion (−/−) | 8 | N | |

| MAX2 † | F-box protein in strigolactone signaling | 4684 | 2840 (60.6) | - | - | 1 | N |

| UBC4 † | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) | 2670 | 2274 (85.2) | - | - | - | N |

| UBC10 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) | 3174 | 1361 (42.9) | - | - | 2 | N |

| RHF2A † | RING-E3 ubiquitin ligase | 3408 | 1457 (42.8) | - | - | - | N |

| RPT2A | A 26S proteasome subunit | 3104 | 1328 (42.8) | - | - | 1 | N |

| CIPK9 † | Protein kinase in signaling | 4298 | 3905 (90.7) | - | - | - | N |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pašakinskienė, I. A Spreading-Stem-Growth Mutation in Lolium perenne: A New Genetic Resource for Turf Phenotypes. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2541. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112541

Pašakinskienė I. A Spreading-Stem-Growth Mutation in Lolium perenne: A New Genetic Resource for Turf Phenotypes. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2541. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112541

Chicago/Turabian StylePašakinskienė, Izolda. 2025. "A Spreading-Stem-Growth Mutation in Lolium perenne: A New Genetic Resource for Turf Phenotypes" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2541. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112541

APA StylePašakinskienė, I. (2025). A Spreading-Stem-Growth Mutation in Lolium perenne: A New Genetic Resource for Turf Phenotypes. Agronomy, 15(11), 2541. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112541