Regulatory Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Stoichiometry in a Temperate Agroecosystem

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composting Materials and Preparation

2.2. Experimental Site and Design

2.3. Soil Sampling and Processing

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.4.1. Determination of Soil Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Fractions

2.4.2. Soil Urease Activity and Enzymatic Kinetics

2.5. Data Processing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Fractions

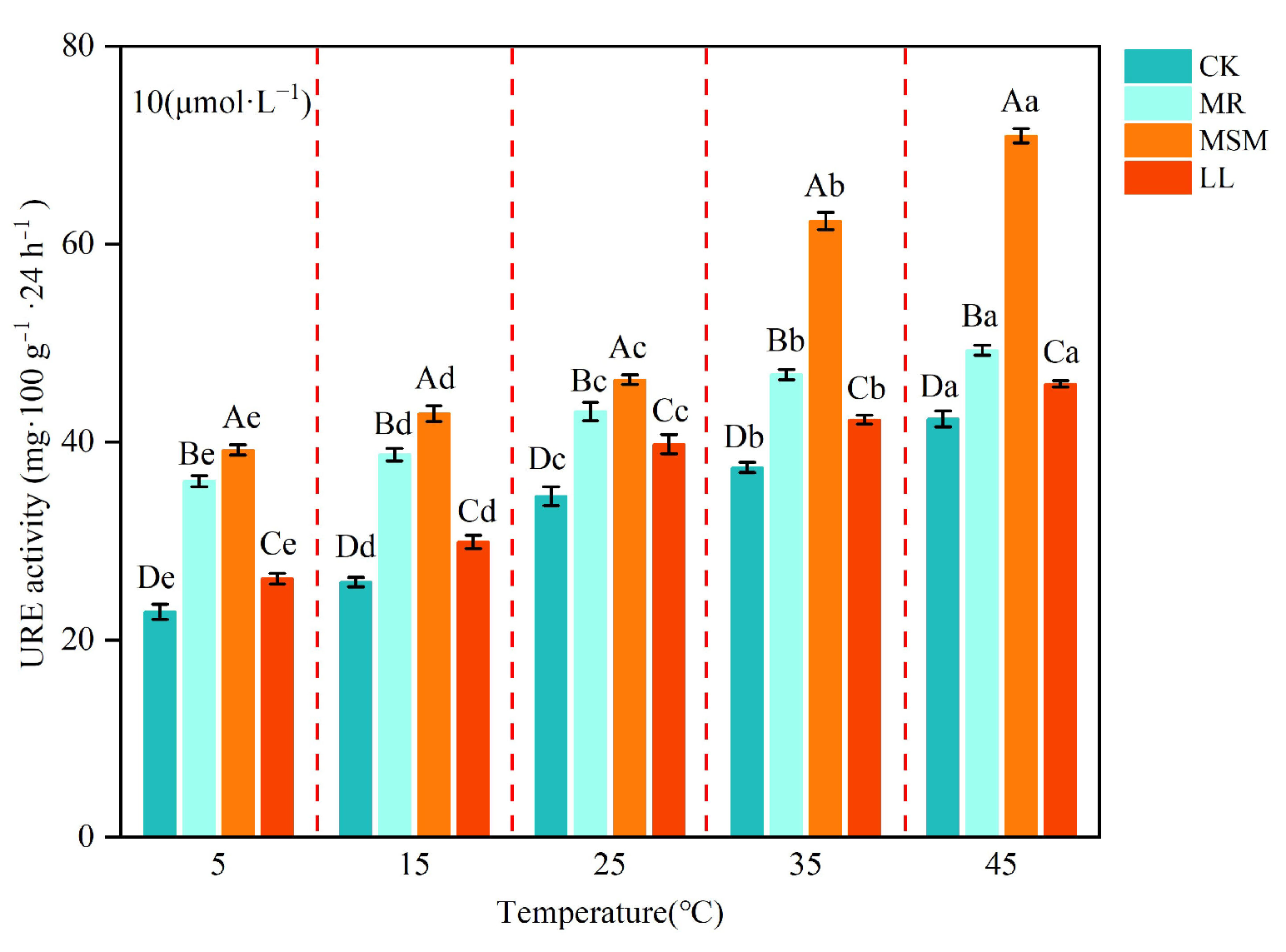

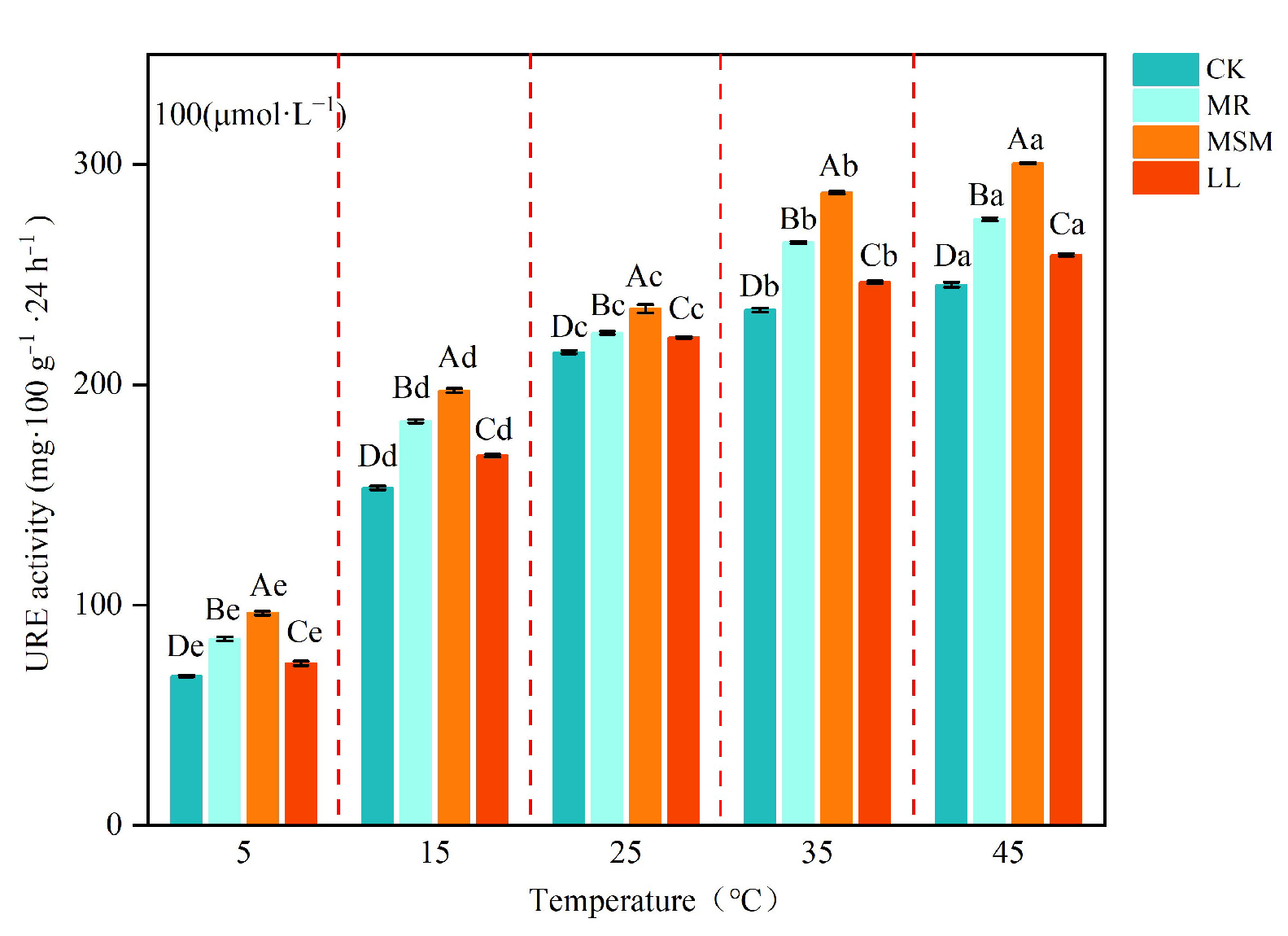

3.2. Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Activity

3.3. Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetic Parameters

3.4. Effects of Compost Amendments on Temperature Sensitivity

3.5. Effects of Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Thermodynamic Parameters

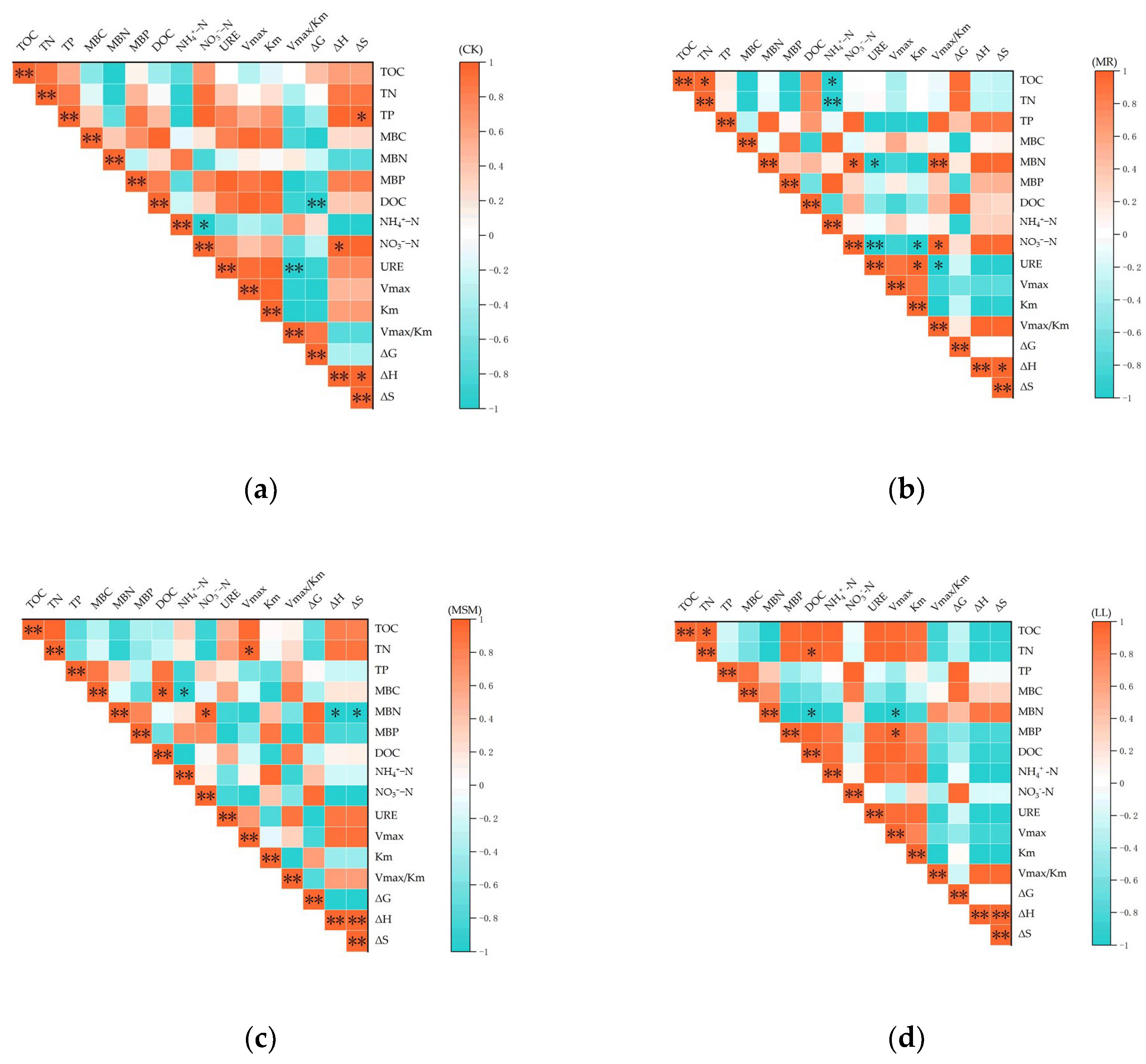

3.6. Correlation Between Urease Kinetic Parameters and Soil C and N Fractions

3.7. Redundancy Analysis of Soil Enzyme Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Fractions

3.8. Mechanistic Pathway Analysis of Soil Fertility Enhancement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inoue, A.; Kameya, T.; Oya, M. Probability Density Functional Method of Enzyme Effect on Denatured Protein Soil. J. Oleo Sci. 2024, 73, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, X. Long-Term Organic Manure Application Alters Urease Activity and Ureolytic Microflora Structure in Agricultural Soils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Ge, T.; Nie, M.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Alharbi, S.; Fang, C.; Deng, Z. Contrasting effects of maize litter and litter-derived biochar on the temperature sensitivity of paddy soil organic matter decomposition. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1008744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, Y.; Dou, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, L.; An, S. Linkage between soil ectoenzyme stoichiometry ratios and microbial diversity following the conversion of cropland into grassland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 314, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; He, D.; Fu, S.; Wan, S.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; et al. Responses of litter, organic and mineral soil enzyme kinetics to 6 years of canopy and understory nitrogen additions in a temperate forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhu, B.; Zeng, H. Soil extracellular enzyme stoichiometry reflects the unique habitat of karst tiankeng and helps to alleviate the P-limitation of soil microbes. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 144, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.; Abdelkerim-Ouba, D.; Liu, D.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. Impacts of Partial Substitution of Chemical Fertilizer with Organic Manure on the Kinetic and Thermodynamic Characteristics of Soil β–Glucosidase. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Niu, S.; Yang, H.; Yu, G.; Wang, H.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Tian, D.; et al. Contrasting responses of phosphatase kinetic parameters to nitrogen and phosphorus additions in forest soils. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 32, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Y.H.; Chen, Z.H.; Chen, L.J.; Qiu, W.W.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, Y.L. Kinetics of Soil Urease in Four Agricultural Soils Affected by Urease Inhibitor PPD at Contrasting Moisture Regimes. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2014, 45, 2268–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Z.; Agathokleous, E.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, D.; Han, J. Unveiling a New Perspective on Cadmium-Induced Hormesis in Soil Enzyme Activity: The Relative Importance of Enzymatic Reaction Kinetics and Microbial Communities. Agriculture 2024, 14, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Hartemink, A.E.; Shi, Z.; Liang, Z.; Lu, Y. Land use and climate change effects on soil organic carbon in North and Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunito, T.; Moro, H.; Mise, K.; Sawada, K.; Otsuka, S.; Nagaoka, K.; Fujita, K. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry as a temporally integrated indicator of nutrient availability in soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 70, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagodatskaya, E.; Blagodatsky, S.; Khomyakov, N.; Myachina, O.; Kuzyakov, Y. Temperature sensitivity and enzymatic mechanisms of soil organic matter decomposition along an altitudinal gradient on Mount Kilimanjaro. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 4284-2018; Control Standards of Pollutants in Sludge for Agricultural Use. National Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Kamruzzaman, M.; Rees, R.M.; Islam, M.T.; Drewer, J.; Sutton, M.; Bhatia, A.; Bealey, W.J.; Hasan, M. Improvement of Physical and Chemical Properties of Calcareous Dark Gray Soil Under Different Nitrogenous Fertilizer Management Practices in Wetland Rice Cultivation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 994–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, W.; Zheng, H.; Chi, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, F.; Liu, Y.J.C. Reseeding restoration significantly improves the physical and chemical properties of degraded grassland soil in China—A meta-analysis. CATENA 2025, 252, 108849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yu, N.; Huang, L. Study on rhizosphere microbial community structure and soil physical and chemical properties of rare trees in Xiangxi Region. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2023, 43, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; He, N.; Wen, X.; Sun, X.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Kuzyakov, Y. Hydrolase kinetics to detect temperature-related changes in the rates of soil organic matter decomposition. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2017, 81, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Xue, S. Kinetic Parameters of Soil Enzymes and Temperature Sensitivity Under Different Mulching Practices in Apple Orchards. Agronomy 2025, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.; Wei, X.; Razavi, B.S.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Jones, D.L.; Wu, J. Stability and dynamics of enzyme activity patterns in the rice rhizosphere: Effects of plant growth and temperature. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, B.; Ibrahim, Z.; Rüger, L.; Ganther, M.; Maccario, L.; Sørensen, S.J.; Heintz-Buschart, A.; Tarkka, M.T.; Vetterlein, D.; Bonkowski, M.; et al. Soil texture is a stronger driver of the maize rhizosphere microbiome and extracellular enzyme activities than soil depth or the presence of root hairs. Plant Soil 2022, 478, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, W.; Zhao, Q.; Liang, M.; Chen, W.; Guo, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Temperature sensitivity of soil enzyme kinetics under N and P fertilization in an alpine grassland, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, N. Thermodynamics of Soil Microbial Metabolism: Applications and Functions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Tie, L.; Huang, C.; Sardans, J.; Javier, D.L.C.; Bose, A.K.; Ouyang, S.; Duan, H.; Wang, J.; Peuelas, J.J.G.E.; et al. The Effects, Patterns and Predictors of Phosphorus Addition on Terrestrial Litter Decomposition. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2025, 34, 70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Kumar, A.; Van Zwieten, L.; Auwal, M.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil Aggregates Mediate the Thermal Response of Soil Carbon Mineralization and Microbial Enzyme Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamayunova, V.; Honenko, L.; Baklanova, T.; Pylypenko, T.J.E.E.; Technology, E. Changes in soil fertility in the southern steppe zone of Ukraine. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2025, 26, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holz, M.; Lewin, S.; Kolb, S.; Becker, J.N.; Bergmann, J. How to get to the N—A call for interdisciplinary research on organic N utilization pathways by plants. Plant Soil 2025, 508, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shady, A.J.S.; Research, T. Explore the potential for improving phosphorus availability in calcareous soil through electrokinetic methods. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 250, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, J.Y.; Sun, L.; Wu, J. The combined application of swine manure and straw strips to the field can promote the decomposition of corn straw in “broken skin yellow” of black soil. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahongnao, S.; Sharma, P.; Ahamad, A.; Nanda, S. Analysis of the Fertilizing and Bioremediation Potential of Leaf Litter Compost Amendment in Different Soils through Indexing Method. J. Environ. Prot. 2024, 15, 265–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, B.; Wu, X.; Yu, R.; Shen, L.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, W.J.M. Exploration of the Vermiculite-Induced Bacterial Community and Co-Network Successions during Sludge-Waste Mushroom Co-Composting. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilik, B.; Akdağ, A.; Ocak, N. Different milling byproduct supplementations in mushroom production compost composed of wheat or rice straw could upgrade the properties of spent mushroom substrate as a feedstuff. Cienc. E Agrotecnologia 2024, 48, e000524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindi, A.M.; Zaman, U.; Saleh, E.A.M.; Kassem, A.F.; Rahman, K.U.; Khan, S.U.; Alharbi, M.; Rizg, W.Y.; Omar, K.M.; Majrashi, M.A.A.; et al. Biochemical and thermodynamic properties of de novo synthesized urease from Vicia sativa seeds with enhanced industrial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.W.; Wu, Y.; Chen, W.J.; Sun, W.; Wang, Z.H.; Liu, G.B.; Xue, S. Soil enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics in response to long-term vegetation succession. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 882, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintari, M.; Tuhec, A.; Tratnik, E.; Langerholc, T.J.M. Spent Mushroom Substrate Improves Microbial Quantities and Enzymatic Activity in Soils of Different Farming Systems. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xing, J.; Hu, C.; Song, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.J.F. Decomposition and Carbon and Nitrogen Releases of Twig and Leaf Litter Were Inhibited by Increased Level of Nitrogen Deposition in a Subtropical Evergreen Broad-Leaved Forest in Southwest China. Forests 2024, 15, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Li, T.; Jing, Y. Thermal Pyrolysis Behavior and Decomposition Mechanism of Lignin Revealed by Stochastic Cluster Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 3832–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Sun, W.; Zhu, F.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, S.; Goloran, J.; Xue, S. Straw addition increases enzyme activities and microbial carbon metabolism activities in bauxite residue. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 135, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, E.; Jia, Z.; Siddique, K.H.; et al. Straw-derived biochar regulates soil enzyme activities, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, and enhances carbon accumulation in farmland under mulching. Field Crop. Res. 2024, 317, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Zhou, X.; Luo, G.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, R.; Tian, C.; Peng, J. Soil mineral nitrogen, soil urease activity, nitrogen losses and nitrogen footprint under machine-planted rice with side-deep fertilization. Plant Soil 2024, 494, 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalidi, R.J.H.; Al-Taweel, L. The Effect of Humic Acid and Urea on the Activity of the Urease Enzyme in Soil Planted with Daughter Potatoes. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P.; Das, T.K.; Sen, S.; Govindasamy, P.; Singh, R.; Raj, R.; Mahanta, D.; Meena, M.C.; Bhatia, A.; Shukla, L.; et al. The interplay between external residue addition, and soil organic carbon dynamics and mineralization kinetics: Experiences from a 12-year old conservation agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 122998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehuddin, N.F.; Mansor, N.; Yahya, W.Z.N.; Affendi, N.M.N.; Manogaran, M.D. Organosulfur Compounds as Soil Urease Inhibitors and Their Effect on Kinetics of Urea Hydrolysis. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 2652–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolnik, M.; Irgolič, M.; Perva, A.; Škerget, M. Hydrolytic Decomposition of Corncobs to Sugars and Derivatives Using Subcritical Water. Processes 2025, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; He, Y.; Elgamal, R. Effect of biological enzyme pretreatment on the kinetics, microstructure, and quality of vacuum drying of wolfberry. LWT 2025, 217, 117455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu; Gangadhara, S. Swelling Characteristics of Bioenzyme Stabilized Black Cotton Soil. In Proceedings of the Indian Young Geotechnical Engineers Conference, Silchar, India, 15 March 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Parik, P.; Patra, N.R. Applicability of Clay Soil Stabilized with Red Mud, Bioenzyme, and Red Mud–Bioenzyme as a Subgrade Material in Pavement. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2023, 27, 04023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-B.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Teng, H.H. Kinetic and thermodynamic characteristics of typical soil clay-grained minerals adsorbing soil dissolved organic matter (DOM). Acta Petrol. Mineral. 2025, 44, 451. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Guo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Q. Soil ph promoted respiration is stimulated by exoenzyme kinetic properties for a pinus tabuliformis forest of northern china. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 202, 109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Su, Y.G. Microorganisms exert overriding impacts on the temperature sensitivity of soil C decomposition than substrate quality. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2025, 7, 250303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, S. Long-term phosphorus addition alters soil enzyme kinetics with limited impact on their temperature sensitivity in an alpine meadow. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vanapalli, S.K. Correction functions for soil–water characteristics curves extending the principles of thermodynamics. Can. Geotech. J. 2024, 61, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, N.; Popovic, M.; Molina-Valero, J.; Lestido-Cardama, Y.; Pérez-Cruzado, C. Unravelling the thermodynamic properties of soil ecosystems in mature beech forests. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Weilandt, D.R.; Hatzimanikatis, V. Optimal enzyme utilization suggests that concentrations and thermodynamics determine binding mechanisms and enzyme saturations. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Han, Z.; Wang, D.; Mai, L.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, J.; Yu, X.; Li, G. Effects of different coverings on the simplified static composting and humification process of cheery-tomato straw. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 273–283. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.Y.; Phong, N.V. Phenolic compounds from the stems of Zanthoxylum piperitum and their inhibition of β-glucuronidase: Enzyme kinetics, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1317, 139117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ji, J.; Hao, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, N. Effect of Different Fertilization on Soil Fertility, Biological Activity, and Maize Yield in the Albic Soil Area of China. Plants 2025, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Ni, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Z. Remediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soil Using Soybean Urease-Induced Carbonate Precipitation. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2025, 34, 1973–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Mao, R.; Li, Z.L.; Chen, F.S.; Xu, B.; He, J.; Huang, Y.X.; Fang, X.M. Tree species mixture effect on extracellular enzyme kinetics varies with enzyme type and soil depth in subtropical plantations. Plant Soil 2023, 493, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccà, M.L.; Francesco, C.; Enrico, C.; Flavio, F. Fungal β-glucosidase gene and corresponding enzyme activity are positively related to soil organic carbon in unmanaged woody plantations. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 240238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, K.; Schierling, L.; Sun, Y.; Schuchardt, M.A.; Jentsch, A.; Deola, T.; Wolff, P.; Kiese, R.; Lehndorff, E.; Pausch, J.J.B. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration declines with climate warming in subalpine and alpine grassland soils. Biogeochemistry 2024, 167, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | pH | EC (mS·cm−1) | TOC (g·kg−1) | TN (g·kg−1) | TP (g·kg−1) | TK (g·kg−1) | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | 8.17 ± 0.10 a | 3.32 ± 0.05 a | 281.54 ± 0.25 a | 18.49 ± 0.22 a | 7.73 ± 0.20 a | 32.24 ± 0.06 a | 15.23 ± 0.06 a |

| MSM | 8.27 ± 0.14 a | 2.81 ± 0.02 b | 282.98 ± 0.17 a | 16.45 ± 0.15 b | 13.22 ± 0.07 b | 26.18 ± 0.05 b | 17.20 ± 0.09 b |

| LL | 7.66 ± 0.11 b | 1.52 ± 0.05 c | 254.83 ± 0.05 b | 14.31 ± 0.12 c | 9.94 ± 0.23 c | 38.85 ± 0.11 c | 17.81 ± 0.13 c |

| Treatment | CK | MR | MSM | LL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOC (g·kg−1) | 12.28 ± 0.20 c | 18.21 ± 0.10 b | 18.81 ± 0.03 a | 18.02 ± 0.04 b |

| TN (g·kg−1) | 0.85 ± 0.07 c | 1.27 ± 0.10 b | 1.55 ± 0.09 a | 0.97 ± 0.16 c |

| TP (g·kg−1) | 0.12 ± 0.01 c | 0.15 ± 0.01 bc | 0.2 ± 0.02 a | 0.19 ± 0.01 ab |

| MBC (mg·kg−1) | 185.67 ± 0.37 d | 313.12 ± 2.26 b | 428.83 ± 0.53 a | 236.80 ± 1.79 c |

| MBN (mg·kg−1) | 14.54 ± 0.14 d | 22.32 ± 0.25 b | 28.03 ± 0.07 a | 16.47 ± 0.04 c |

| MBP (mg·kg−1) | 7.20 ± 0.06 d | 8.30 ± 0.05 b | 9.51 ± 0.02 a | 8.01 ± 0.05 c |

| DOC (mg·kg−1) | 100.60 ± 0.08 d | 122.18 ± 0.72 a | 115.06 ± 0.61 c | 120.31 ± 0.68 b |

| NH4 +-N (mg·kg−1) | 4.17 ± 0.01 b | 4.31 ± 0.03 a | 4.34 ± 0.03 a | 4.19 ± 0.01 b |

| NO3−-N (mg·kg−1) | 3.11 ± 0.09 c | 3.44 ± 0.14 b | 3.12 ± 0.13 c | 4.50 ± 0.17 a |

| TOC/TN | 14.47 ± 0.78 b | 14.35 ± 0.96 b | 12.19 ± 0.66 b | 18.88 ± 3.08 a |

| TN/TP | 7.28 ± 0.54 a | 8.27 ± 0.67 a | 7.73 ± 0.82 a | 5.17 ± 0.50 b |

| TOC/TP | 105.48 ± 12.59 ab | 118.38 ± 8.21 a | 94.28 ± 12.27 b | 96.80 ± 10.00 ab |

| Factor | Urease Activity | Kinetic Parameter | Thermodynamic Parameter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km | Vmax | Vmax/Km | ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | ||

| Compost product (C) | 6.33 ** | 231.29 ** | 1159.41 ** | 2494.42 ** | 1062.39 ** | 960.98 ** | 1964.05 ** |

| Temperature (T) | 90.12 ** | 368.83 ** | 38,958.12 ** | 9276.47 ** | 2.79 | 48.34 ** | 294,700.82 ** |

| C × T | 0.48 ** | 81.99 ** | 257.75 ** | 191.34 ** | 0 | 0.40 | 172.68 ** |

| Parameter | Temperature (°C) | CK | MR | MSM | LL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG (kJ·mol−1) | 5 | 69.923 ± 0.07 Ae | 69.702 ± 0.01 Ce | 69.114 ± 0.01 De | 69.819 ± 0.03 Be |

| 15 | 70.746 ± 0.01 Ad | 70.343 ± 0.01 Cd | 69.921 ± 0.01 Dd | 70.577 ± 0.01 Bd | |

| 25 | 72.387 ± 0.01 Ac | 72.203 ± 0.01 Dc | 72.221 ± 0.01 Cc | 72.282 ± 0.01 Bc | |

| 35 | 74.681 ± 0.01 Ab | 74.394 ± 0.07 Cb | 74.307 ± 0.01 Db | 74.574 ± 0.01 Bb | |

| 45 | 77.045 ± 0.01 Aa | 76.792 ± 0.01 Ca | 76.685 ± 0.01 Da | 76.879 ± 0.01 Ba | |

| ΔH (kJ·mol−1) | 5 | 19.682 ± 0.49 Aa | 19.276 ± 0.09 Aa | 14.982 ± 0.13 Ba | 19.711 ± 0.19 Aa |

| 15 | 19.599 ± 0.49 Aa | 19.192 ± 0.09 Aab | 14.900 ± 0.13 Bab | 19.628 ± 0.19 Aa | |

| 25 | 19.516 ± 0.49 Aa | 19.110 ± 0.09 Aabc | 14.816 ± 0.13 Bab | 19.545 ± 0.19 Aa | |

| 35 | 19.433 ± 0.49 Aa | 19.026 ± 0.09 Abc | 14.733 ± 0.13 Bab | 19.462 ± 0.19 Aa | |

| 45 | 19.350 ± 0.49 Aa | 18.943 ± 0.09 Ac | 14.650 ± 0.13 Bb | 19.379 ± 0.19 Aa | |

| ΔS (J·mol−1) | 5 | −180.626 ± 1.50 Ab | −181.295 ± 0.30 Ad | −194.614 ± 0.42 Bd | −180.145 ± 0.55 Ac |

| 15 | −177.502 ± 1.67 Aa | −177.514 ± 0.29 Aa | −190.947 ± 0.42 Ba | −176.813 ± 0.66 Aa | |

| 25 | −177.330 ± 1.61 Aa | −178.077 ± 0.28 Ab | −192.537 ± 0.41 Bb | −176.881 ± 0.62 Aa | |

| 35 | −179.291 ± 1.55 Aab | −179.677 ± 0.30 Ac | −193.329 ± 0.43 Bc | −178.848 ± 0.59 Ab | |

| 45 | −181.348 ± 1.54 Ab | −181.830 ± 0.29 Ae | −194.989 ± 0.42 Bd | −180.734 ± 0.58 Ac | |

| Ea(kJ·mol−1) | — | 21.995 ± 0.49 A | 21.588 ± 0.09 A | 17.295 ± 0.13 B | 22.024 ± 0.19 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Qu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xing, Y.; Dong, Z.; Yu, W.; Zhang, G.; Wu, P. Regulatory Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Stoichiometry in a Temperate Agroecosystem. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112544

Liu Q, Zhang X, Guo X, Qu Y, Zheng J, Xing Y, Dong Z, Yu W, Zhang G, Wu P. Regulatory Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Stoichiometry in a Temperate Agroecosystem. Agronomy. 2025; 15(11):2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112544

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qian, Xu Zhang, Xingchi Guo, Ying Qu, Junyan Zheng, Yuhe Xing, Zhiyu Dong, Wei Yu, Guoyu Zhang, and Pengbing Wu. 2025. "Regulatory Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Stoichiometry in a Temperate Agroecosystem" Agronomy 15, no. 11: 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112544

APA StyleLiu, Q., Zhang, X., Guo, X., Qu, Y., Zheng, J., Xing, Y., Dong, Z., Yu, W., Zhang, G., & Wu, P. (2025). Regulatory Effects of Different Compost Amendments on Soil Urease Kinetics, Thermodynamics, and Nutrient Stoichiometry in a Temperate Agroecosystem. Agronomy, 15(11), 2544. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15112544