Abstract

Bone is one of the most important organs of mammals, consisting of collagen and apatite. Various diseases, such as osteoporosis, can affect the components of bone tissue, their chemical composition and bone ultrastructure, which leads to changes in properties. In this paper, the effect of initial osteoporosis on the chemical composition of bone apatite and the ultrastructure of bone tissue from a mineralogical point of view is analyzed using rat femurs as an example. The chemical composition of bone apatite was studied using SEM, EDS and FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. The bone ultrastructure was examined using a transmission electron microscope. An increase in the content of carbonate ion in the position of the phosphorus group and a change in the orientation of apatite crystals inside mineral plates were revealed against the background of initial osteoporosis, which can affect not only the mechanical properties of bone, but also the stability of apatite under biological conditions.

1. Introduction

Bone tissue as an object of research has been of great interest to researchers for centuries. It is a mineral–organic composite. The organic component is mainly collagen (protein). The inorganic component is the bone apatite (BA) [1,2].

Bone tissue can be described as a natural composite material formed by osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), in which the matrix has the following structure. Collagen occurs in cylindrical fibrils about 50 nm in diameter in which individual collagen triple helices are staggered with a repetition period of 67 nm. At the same time, a gap—is formed between the end of one collagen helix and the beginning of the next. Due to the staggered arrangement of the molecules, these gaps line up, forming gap zones 40 nm long [3,4,5]. BA is located as 5 nm thick curved platelets surrounding the collagen fibers. BA ultrastructure in bone tissue is debated in the scientific community [6]. In our recent work, we recorded extrafibrillary mineral platelets (MPs) in the cortical bone of healthy Wistar rats. The blocks had different orientations of the c-axis of the unit cell, and the MPs themselves were parallel to the long axis of the collagen fibril [7].

There are several hypotheses explaining the formation of BA in the collagen matrix. The process of BA formation may begin with a precursor phase in the form of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) although this has never been detected in human bone. Some researchers suggest the existence of an intermediate phase—octacalcium phosphate (Ca8H2(PO4)6·5H2O) [8,9], but no direct evidence of its presence has been found [10,11]. In addition, all modern hypotheses of bone matrix mineralization are based on the fact that this process is cell-dependent, that is, the formation of the precursor phase occurs within osteoblasts [12].

Osteoporosis Mineralogical Aspect

Osteoporosis consists of the gradual impairment of bone mass, strength, and microarchitecture of skeletal bone, which increases its probability of fracture. A routine method to determine its occurrence is through the measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). About 40% of postmenopausal women exhibit osteoporosis. The lifetime fracture risk of a patient with osteoporosis is as high as 40%, most commonly in the spine, hip, or wrist. However, the trochanter, humerus, ribs and other bones can also be affected [13].

Osteoporosis research is usually considered a field of medical and pharmaceutical research. Such studies do not investigate changes in the chemical composition and structure of bone mineral. Considered from a mineralogical point of view, osteoporosis represents a change in the conditions of mineral formation. Therefore, it would be interesting to investigate changes occurring in bone tissue from a mineralogical point of view. In this paper, we will consider changes in bone tissue apatite in osteoporosis both in terms of the chemical composition of BA in relation to the nanostructure of bone tissue.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods for Obtaining Biological Samples

It is possible to experimentally induce osteoporosis in an ovariectomized rat. In previous studies anatomical site specific, time dependent alterations in BMD and microarchitecture of trabecular bone have been reported [14]. Experiments with laboratory rabbits have shown that changes also occur in cortical bone tissue [15].

The study was conducted on 12 sexually mature female Wistar rats weighing 180–230 g obtained from a certified breeder, which after a quarantine period of 14 days were kept in standard vivarium conditions with natural light conditions and a standard diet with free access to water and food (without a diet containing a limited amount of calcium). Relative humidity of 50–65% and air temperature of 20–25 °C were maintained in the vivarium around the clock. All procedures with animals were performed in the morning hours (from 9:00 to 11:00 local time) in accordance with the rules and recommendations for the humane treatment of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes (Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation dated 1 April 2016 No. 199n “On approval of the Rules of Good Laboratory Practice”).

The animals were randomized into two groups. Six animals of the experimental group underwent laparotomy and bilateral ovariectomy under sterile conditions under intramuscular anesthesia (Zoletil 100 (Virbac, Carros, France)). The control group consisted of six animals that were not subjected to any treatment. After the end of the study period (after 21 days), the animals were taken out of the experiment by simultaneous decapitation under CO2-anesthesia. Then, the femur bones were collected for further studies.

2.2. Chemical Composition Studies

To study the morphological features of cortical bone tissue and the chemical composition of BA, we obtained cross sections of femurs. Sections were obtained from the central diaphysis of each animal. This yielded 12 sections: 6 for the control group and 6 for the osteoporotic group. The chemical composition of BA was determined using X-ray spectral microanalysis and ATR FTIR. Analyses were performed evenly across all four quadrants of the section in the mesocortex: 6–10 analyses per quadrant for X-ray spectral microanalysis, 1 analysis per quadrant for ATR FTIR. To study trabecular bone tissue, longitudinal sections were made through the center of the pineal gland. One section was also obtained from each animal. Two fields of view with 8–12 dimensions were obtained per bone.

SEM investigation were carried out by X-ray spectral microanalysis using a Tescan VEGA II scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic), combined with INCA X-act Energy350 Oxford spectrometers (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK). To do this, the samples were coated with a conductive material (carbon) in a vacuum. Parameters for the analysis of the chemical composition of minerals with an energy-dispersive analyzer: accelerating voltage 20 kV, active acquisition time 120 s, tungsten cathode, probe beam size 1–2 μm. MAC standard samples were used (55 Standard Universal Block Layout + F/Cup, Micro-Analysis Consultants Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK): SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, Ca3Si3O9, NaAlSi3O8, KAlSi3O8, NaCl, MgF2, BaF2, FeS2, GaP. Quantitative optimization was performed for cobalt. Precision (reproducibility) of analysis was ± 0.05 wt% for all elements. Calculation of crystal chemical coefficients of apatite was carried out by the cation method (for 16 cations).

For statistical analysis, logarithmic data were analyzed using the STATISTICA 12 software package. Cluster analysis was performed using the Ward method.

The infrared (IR) spectra of the sections were recorded using an attenuated total reflection (ATR) method with a Micran-3 IR microscope and a Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, the Simex FT-801 (Simex, Novosibirsk, Russia), equipped with a 25 µm Ge-ATR probe and an MCT detector. The spectra were measured in the range of 650 to 4000 cm−1, with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 accumulations. Processing and deconvolution of spectra was carried out in the ArDi web-app [16].

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy

One section cut along the length of a femur was prepared. Due to the complexity of sample preparation, three femurs from each group were randomly selected for TEM examination. Six fragments of the central diaphysis mesocrex were prepared for TEM examination. The section was thinned by grinding on a hard substrate. The SiC abrasive was changed when a fixed thickness was reached: up to 1 mm, number 1000 was used, up to 0.4 mm—2500, and up to 0.3 mm—5000. Next, polishing was performed on a Model 200 Dimpling Grinder (Fischione instruments, Export, PA, USA), resulting in the formation of opposite depressions on each side of the plate, the thickness of the material between which was about 20 μm. Then, the samples were subjected to ion thinning on a Model 1051 TEM Mill (Fischione instruments, Export, PA, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV, resulting in perforation in the previously obtained depression. The obtained samples were examined using a JEM-2100 TEM (Jeol, Tokio, Japan), equipped with an attachment for energy dispersive analysis (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK), at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV, in bright field and dark field imaging.

3. Results

3.1. Micromorphology of Bone Tissue and Chemical Composition of BA

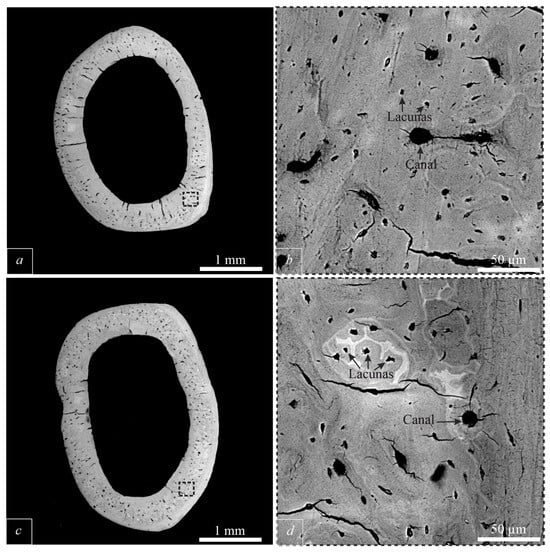

Images of femoral cortical bone tissue were obtained in the backscattered electron mode (Figure 1). Based on these images, measurements were made of the main morphological elements of bone tissue: canals (canals in which blood vessels and nerves pass) and lacunae (cavities in which osteoblasts and osteocytes are located). Based on 48 images at 1000× magnification in BSE mode (24 for each group), the number of lacunae and canals within the field of view was measured. The number of lacunae within the field of view of healthy bone tissue ranged from 26 to 40, while that of osteoporotic bone tissue ranged from 27 to 42. The number of canals in both cases ranged from 3 to 5.

Figure 1.

SEM BSE images of the cross section femur. (a)—cross section of healthy bone; (b)—enlarged image; (c)—cross section of bone with initial osteoporosis; (b,d)—enlarged images of images (a,c).

Table 1 presents the calculated coefficients of atoms per formula unit (apfu) of elements. In osteoporosis, the calcium content increases in the BA of cortical bone tissue with a decrease in the phosphorus content. Of the elements that isomorphically replace phosphorus, sulfur should be noted. In osteoporosis, the content of this element increases slightly. In trabecular bone tissue, in osteoporosis, the calcium content decreases with an increase in the phosphorus content. In addition, an increase in the sulfur content.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of BA from healthy and osteoporosis bone tissues. The number of measurements is indicated in brackets.

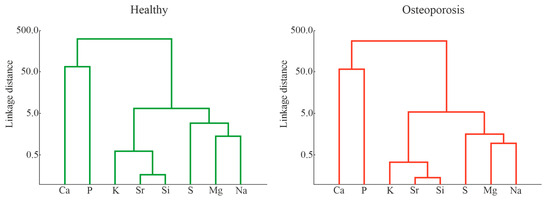

A statistical analysis of the chemical composition data of BA was performed. Four groups are distinguished on the dendrograms (Figure 2). Two mono element (I—Ca; II—P), which are contrasted with multi element groups (III—K, Sr, Si; IV—S, Mg, Na). These clusters are distinguished both for the BA of the bone tissue of the control group and for the bone tissue susceptible to osteoporosis. Given the identical nature of the grouping of elements on the dendrograms, it can be assumed that the nature of isomorphism does not change when the disease occurs.

Figure 2.

Dendrograms obtained by cluster analysis of the Ward method based on the results of the analysis of the chemical composition of healthy bones and bones with initial osteoporosis.

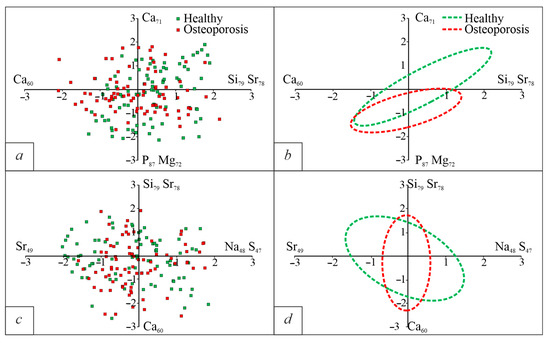

Factor analysis of the sample using the principal component method revealed 3 factors describing 80.76% of the system variability. The identified factors are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factor loadings of BA elements from healthy and osteoporotic bone tissue.

The results of the factor analysis are shown in Figure 3. Using Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Application with Nose on Python 3.0, we identified areas with the highest point density (Figure 3b,d). The areas have large overlapping areas. Only a small separation can be seen on factor number 1.

Figure 3.

Diagrams of chemical characteristics of BA in the coordinates of factor loads. (a)—F1/F2; (b)—areas of the densest distribution of points for the F1/F2 diagram; (c)—F2/F3; (d)—areas of the densest distribution of points for the F2/F3 diagram.

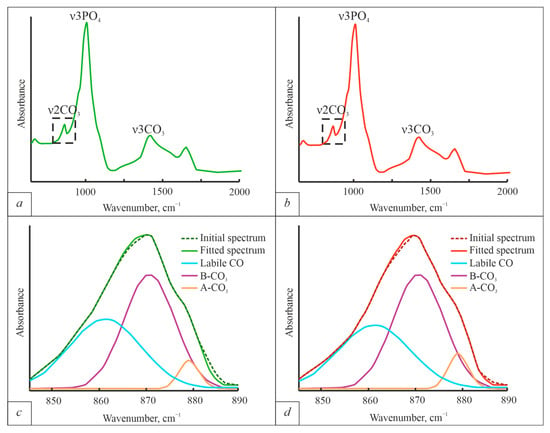

ATR-FT-IR spectra of BA were obtained (Figure 4). The spectra were pre-smoothed and the regions 840–890 cm−1, where the ν2 CO3 bands are located (Figure 4c,d), were studied in detail following the methods shown by [17].

Figure 4.

ATR-FTIR spectra of BA bone tissue. (a)—spectrum obtained from the bone of a healthy individual; (b)—spectrum obtained from the bone of an individual with osteoporosis; (c)—region 840–890 cm−1 with ν2 CO3 bands and deconvolution results of healthy bone; (d)—region 840–890 cm−1 with ν2 CO3 bands and deconvolution results of osteoporotic bone. The experimental curves were deconvoluted using Gaussian peak shape functions.

The ATR-FTIR results show that both A-type and B-type substitutions are present in BA. B-type substitutions are dominant in both diseased and healthy BA. However, when the disease occurs, the integral intensity of the A-type carbonate group bands increases (from 1.10 ± 0.04 in healthy bone, to 1.21 ± 0.03 in osteoporotic bone) without changing in integral intensities of the B-type carbonate group bands (9.42 ± 0.37 for healthy bone and 9.43 ± 0.43). The average B-type/A-type bands area ratio decreases from 8.6 in healthy individuals to 7.8 when the disease occurs.

3.2. Bone Tissue Ultrastructure and Structural Characteristics of BA

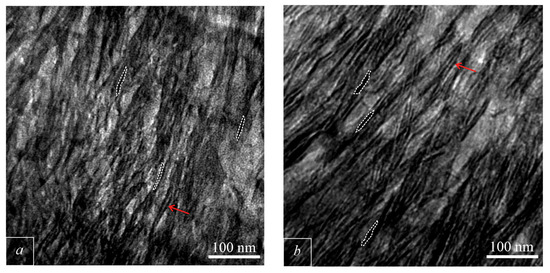

Bright field TEM images of bone tissue were obtained. The images obtained from healthy bone tissue show extrafibrillary MPs of BA measuring up to 50 × 10 nm (Figure 5a). The axis of the BA unit cells of the MPs are oriented along the collagen fibers, parallel to bone elongation. When osteoporosis occurs, the morphology of MPs remains unchanged, the thickness of the MPs also remains unchanged (Figure 5b). We observe that MPs are packed in stacks (red arrow on Figure 5). The number of MPs in one stack may exceed ten.

Figure 5.

TEM light field images of bone. (a)—healthy bone; (b)—osteoporotic bone. Red arrows shows stacks of MPs. The dotted line outlines the MP.

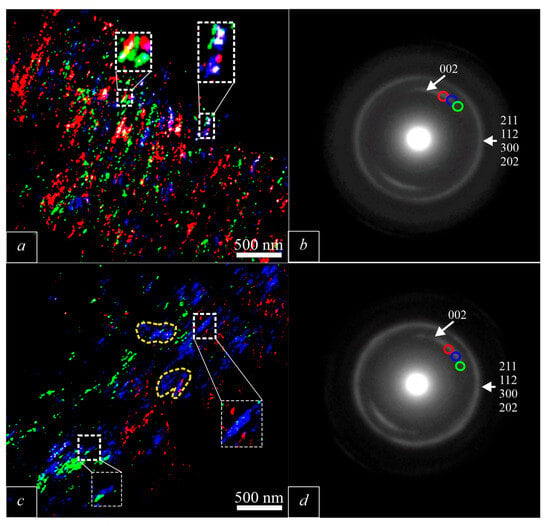

In order to obtain detailed information about the orientation of the c-axis in the MP, a series of dark-field images of different sections of the reflex arc (002) were obtained. In the obtained images, the grayscale gradations were replaced by gradations of other colors for ease of perception, after which the obtained images were superimposed on each other. Previously, we obtained dark-field images of the (002) reflex MPs of BA with a subblock structure (Figure 6a). This structure of the MPs is expressed in the presence of blocks with different orientations of the BA c-axis.

Figure 6.

Compilation of dark field images generated from different areas of (002) arc. The color of the area in figures (a,c) corresponds to the color of the point on the arc (002) from which the dark-field image in figures (b,d) was obtained. (a)—dark field image of healthy bone [7]; (b)—electron diffraction pattern obtained from the a area [7]; (c)—dark field image of osteoporotic bone; (d)—electron diffraction pattern obtained from the c-area.

In the dark-field images of osteoporotic bone tissue (Figure 6), we record two types of changes. The mosaic structure characteristic of BA in healthy bone tissue disappears with the onset of osteoporosis (white frame in Figure 6c). The c-axis of BA in healthy bone tissue does not have a preferred orientation, while with the onset of osteoporosis, BA forms clusters with a preferred orientation of the c-axis (yellow dotted line in Figure 6c).

4. Discussion

Based on the obtained results, a number of characteristic features of the mineral platelets of bone tissue in the early stage of osteoporosis can be seen.

4.1. Morphology of Bone Tissue and Chemical Composition of BA and Their Changes in Early Osteoporosis

In cases of early osteoporosis, no change in the number of lacunae and canals was recorded. Our data show that bone tissue BA is represented by carbonate-containing calcium-deficient BA, which is consistent with the results of other researchers [2,18,19]. Despite this, a number of clarifications are necessary. The structure of non-biological BA suggests that along the c-axis there are channels formed by Ca2+, ions, in which additional anions are located in the form of fluorine, chlorine and hydroxyl group. Experimentally, in the work [20] it was shown that the OH- anion in the channels along the c-axis is significantly less than it should be. In this case, the existence of a stable structure can provide heterovalent substitution CO32− ↔ 2OH− (A-type). However, measurement of the ratio of the peak areas of CO32− A and B types according to ATR-FTIR data (Figure 4c) shows that most CO3 ions are at B rather than A sites. These data are in excellent agreement with the data obtained by other authors [21,22]. In connection with the above, it can be assumed that apatite of this composition is metastable and can exist in this state only in bone tissue. In the review [6] it is noted that the mechanism of BA structure stabilization still remains unresolved, a number of assumptions can be made on this account. In the work [23] it is noted that in the temperature range of 100–500 °C there is a slight narrowing of the peaks (002) and (310), which indicates an increase in the areas of coherent scattering along the c axis and the a axis. This is associated with the onset of the BA recrystallization process. In the same temperature range, a significant loss of bone tissue mass occurs, while the content of the species-forming elements of BA remains unchanged. This temperature range corresponds to the complete disappearance of collagen traces [24]. Therefore, we assume that the main factor stabilizing the BA structure is collagen. We will touch on this in more detail below when we discuss changes in the BA ultrastructure in osteoporosis.

Pathological change in the form of osteoporosis does not lead to a change in the stoichiometry of apatite, which can be seen from Table 1. The principles of isomorphic substitutions and the “antagonism” of the elements included in apatite are also not violated, which can be judged by the nature of the dendrograms obtained during cluster analysis (Figure 3). The results of factor analysis also do not allow us to identify changes in the chemical composition of bone apatite in osteoporosis. Nevertheless, it can be seen that in the case of osteoporosis, the role of phosphorus and magnesium becomes more noticeable. Analysis of the ATR FTIR spectra shows that the intensity of the ν2 PO4 peak decreases, while the intensity of the ν2 AB-CO3 peak increases. The integrated intensity of the B-type CO3 absorption band remains unchanged, while the integrated intensity of the A-type absorption band increases. It can be assumed that this indicator will change as the disease progresses.

We intentionally did not use the Ca/P ratio, which is often used by osteoporosis researchers as a criterion for changes in chemical composition, since this indicator demonstrates extremely contradictory results regarding BA analysis [25,26]. A recent review [6] also notes the contradictory nature of this indicator. Largely, this contradiction is due to the extreme simplification of the chemical composition of BA. When analyzing the Ca/P indicator, both cationic substitutions of the isovalent type Ca2+ ↔ Sr2+, Mg2+, heterovalent type Ca2+ ↔ 2K+, 2Na+, and extremely complex substitutions in the anionic part are completely ignored. We agree with the conclusions in the review [6], it is indeed necessary to develop alternative indicators before introducing such a clear and strictly defined criterion. In our work, we recorded only an increase in CO3 at the PO4 position in the mineral structure, so we believe that this indicator requires close attention.

4.2. Changes in the Ultrastructure of Bone Tissue in Osteoporosis

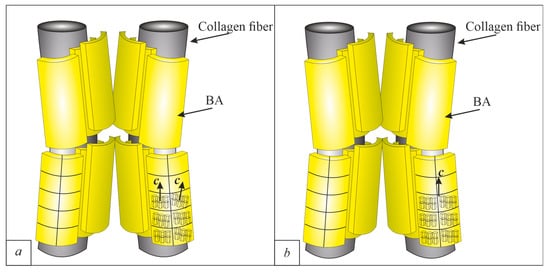

The mineral crystals have been under close attention of researchers recently. This is logical, because the location of apatite, its orientation, and relationship with organic components of bone are the key to understanding the unique mechanical properties of bone. Figure 5a shows the images we obtained during the TEM study of healthy bone tissue. In the bright field images, mineral platelets of BA formed packs. The number of MPs in one pack ranges up to 10 or more. We interpret these MPs as extrafibrillar MPs. These MPs are not BA single crystals, but are polycrystalline aggregates with a mosaic structure (Figure 6), which we noted in our previous work [7]. The Mosaic structure is expressed in the form of different orientations of the c-axis of the BA unit cell inside the MP, and the MPs are twisted around collagen fibrils [7]. The presence of such blocks was noted by the presence of moire patterns by Schwarcz [27]. Based on these data, as well as on the scheme proposed by Schwarcz [27,28] a scheme of the BA ultrastructure was made (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Ultrastructure of apatite in bone. (a)—healthy bone from [7]; (b)—osteoporotic bone (from this work).

The space between the MPs is filled with a less dense substance, judging by the contrast in bright-field images. This space is filled with citrate ions ([C6H5O7]3−), which act as a “glue” between MPs [29]

As in the case of healthy mineral formation, in the case of pathology, in bone tissue, MPs of BA up to 50 × 10 nm in size are extended along collagen. The c axis of the BA unit cell is co-directed with collagen fibers. Despite the apparent lack of changes in the BA ultrastructure in osteoporosis, these changes are clearly recorded in dark field TEM images. The subblock structure of MPs disappears (Figure 6c). In osteoporosis, we observe the formation of areas with preferential orientations of the c axis of BA. This is the first recorded changes in bone affected by osteoporosis ultrastructure. To explain such changes in the mineral during the onset of the disease, it is necessary to consider the process of BA formation in bone tissue.

The mechanism of BA formation in bone tissue is still a subject of debate. Despite the large number of views, all hypotheses can be divided into cell-independent [30] and cell-dependent [12,31,32]. In cell-dependent mechanisms of BA formation, BA formation begins inside the osteoblast with the formation of nanosized molecular clusters in vesicles. After that, it is released into the extracellular environment, where Ap formation occurs [33]. These clusters are called “Posner clusters” [34]. The BA precursor phase, amorphous calcium phosphate, consists of these components. This was confirmed in a recent study [35]. In the extracellular space, Posner’s clusters begin to stick together, forming amorphous calcium phosphate, which is subsequently transformed into polycrystalline MPs of BA. There are works indicating that the lamellar form of MPs arises from gradual sticking of clusters, which leads to the formation of hexagonal columns, from which MPs are formed [36]. However, recent work using high-resolution TEM has shown that bone apatite is a monoclinic phase, which would explain the morphology of the mineral plates well [37].

This is how BA is formed in the case of a healthy physiological process. The reasons for the change in the BA ultrastructure in bone tissue even at the earliest stage of the disease are hidden in the BA growth environment. With the onset of osteoporosis, a systemic disruption of the functioning of all bone cells, including osteoblasts, occurs [38]. Since the presence of CO3 in BA is detected at the earliest stage of mineralization [39], then changes in the CO3 content in BA, which we record using ATR-FTIR, are logically considered as one of the indirect signs of osteoblast dysfunction. However, this is not the only reason. In [40,41,42], it is noted that collagen crosslinking (the connection between adjacent collagen fibers) worsens in osteoporosis caused by menopause. It is important that collagen crosslinking provides the packaging and density of the collagen fibrils [43]. In case of damage to the collagen matrix, the BA structure of MPs does not manifest itself. This is similar to the mechanism of stabilization of metastable BA when removing the organic component, which we wrote about earlier. Changes in the distribution of crystal orientations in combination with changes in collagen crosslinking will inevitably lead to changes in the mechanical properties of such a composite-like material as bone, even at the initial stages, when no noticeable loss of bone mass is recorded.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the effect of early-stage osteoporosis on the chemical composition of BA and bone ultrastructure.

In the anionic part, an increase in carbonate (CO3) content at the hydroxyl group (OH) position occurs. To identify more distinct trends in the mineral’s chemical composition, it is necessary to examine these changes over the course of the disease.

Alterations in bone ultrastructure are detected in initial osteoporosis. These changes are characterized by the disappearance of the block structure of mineral platelets and the formation of clusters of mineral platelets with a preferred orientation of the BA c-axis. These changes are the first data on changes in bone ultrastructure in early osteoporosis. Most likely, such changes are caused by a disruption of osteoblast function, which leads to changes in the collagen matrix and subsequent abnormal formation of apatite mineral platelets in the bone.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization A.A.B., O.V.B.; methodology, E.A.K., A.A.B., O.V.B.; investigation A.A.B., R.Y.S., O.V.B.; writing—original draft A.A.B.; writing—review and editing H.P.S., D.V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out within the framework of the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (project № FSWM-2025-0015).

Data Availability Statement

All new data are presented in this article.

Acknowledgments

The TEM investigations have been carried out using the equipment of Share Use Centre “Nanotech” of the ISPMS SB RAS. SEM investigations were performed using the equipment center for collective use “Analytical Center Geochemistry of Natural Systems” TSU. The IR measurements were performed at the Center of Isotope and Geochemical Research for Collective Use (A. P. Vinogradov Institute of Geochemistry of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- LeGeros, R.Z.; LeGeros, J.P. Dense Hydroxyapatite. In An Introduction to Bioceramics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1993; pp. 139–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Kamenetskaya, O.V. Structure, Chemistry and Synthesis of Carbonate Apatites—The Main Components of Dental and Bone Tissues. In Minerals as Advanced Materials I; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Petruska, J.A.; Alan, J.H. A subunit model for the tropocollagen macromolecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1964, 51, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orgel, J.P.R.O.; Irving, T.C.; Miller, A.; Wess, T.J. Microfibrillar Structure of Type I Collagen in Situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9001–9005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blair, H.C.; Larrouture, Q.C.; Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Beer-Stoltz, D.; Liu, L.; Tuan, R.S.; Robinson, L.J.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Nelson, D.J. Osteoblast Differentiation and Bone Matrix Formation In Vivo and In Vitro. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2016, 23, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.A. Revisiting the Physical and Chemical Nature of the Mineral Component of Bone. Acta Biomater. 2025, 196, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibko, A.A.; Lychagin, D.V.; Bukharova, O.V.; Kostrub, E.A.; Khrushcheva, M.O. Nanocomposition of Hydoxylapatite from Cortical Bone Tissue. Mineralogy 2024, 10, 20–31. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pompe, W.; Worch, H.; Habraken, W.J.E.M.; Simon, P.; Kniep, R.; Ehrlich, H.; Paufler, P. Octacalcium Phosphate—A Metastable Mineral Phase Controls the Evolution of Scaffold Forming Proteins. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5318–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsson, M.S.-A.; Nancollas, G.H. The Role of Brushite and Octacalcium Phosphate in Apatite Formation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1992, 3, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimcher, M.J. Bone: Nature of the Calcium Phosphate Crystals and Cellular, Structural, and Physical Chemical Mechanisms in Their Formation. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2006, 64, 223–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, H. Bone Apatite Nanocrystal: Crystalline Structure, Chemical Composition, and Architecture. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.C. Matrix Vesicles and Calcification. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2003, 5, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the Future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.R.; Bates, D.; Black, D.M. Clinical Use of Bone Densitometry: Scientific Review. JAMA 2002, 288, 1889–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, K.D.; Hiebert, B.D.; Panahifar, A.; Andronowski, J.M.; Ashique, A.M.; King, G.A.; Arnason, T.; Swekla, K.J.; Pivonka, P.; Cooper, D.M.L. Cortical Bone Porosity in Rabbit Models of Osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 2211–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnov, S.; Shendrik, R.; Myasnikova, A.; Plechov, P. ArDI: Machine-Learning-Driven Raman Phase Analysis for Decoding Complex Mineral Assemblages in Fluid Inclusions. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madupalli, H.; Pavan, B.; Tecklenburg, M.M.J. Carbonate Substitution in the Mineral Component of Bone: Discriminating the Structural Changes, Simultaneously Imposed by Carbonate in A and B Sites of Apatite. J. Solid State Chem. 2017, 255, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, L.T.; Grynpas, M.D.; Rey, C.C.; Wu, Y.; Ackerman, J.L.; Glimcher, M.J. A Comparison of the Physical and Chemical Differences between Cancellous and Cortical Bovine Bone Mineral at Two Ages. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2008, 83, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteris, J.D.; Wopenka, B.; Freeman, J.J.; Rogers, K.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Van der Houwen, J.A.M.; Silva, M.J. Lack of OH in Nanocrystalline Apatite as a Function of Degree of Atomic Order: Implications for Bone and Biomaterials. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.; Wu, Y.; Ackerman, J.L. Detection of Hydroxyl Ions in Bone Mineral by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Science 2003, 300, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, C.; Renugopalakrishman, V.; Collins, B.; Glimcher, M.J. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Study of the Carbonate Ions in Bone Mineral during Aging. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1991, 49, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou-Yang, H.; Paschalis, E.P.; Mayo, W.E.; Boskey, A.L.; Mendelsohn, R. Infrared Microscopic Imaging of Bone: Spatial Distribution of CO32−. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001, 16, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsbeek, N.; Richter, J. Preservation of Burned Bones: An Investigation of the Effects of Temperature and PH on Hardness. Stud. Conserv. 2006, 51, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspanti, M.; Guizzardi, S.; De Pasquale, V.; Martini, D.; Ruggeri, A. Ultrastructure of Heat-Deproteinated Compact Bone. Biomaterials 1994, 15, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourkoumelis, N.; Balatsoukas, I.; Tzaphlidou, M. Ca/P Concentration Ratio at Different Sites of Normal and Osteoporotic Rabbit Bones Evaluated by Auger and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy. J. Biol. Phys. 2012, 38, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baslé, M.F.; Rebel, A.; Mauras, Y.; Allain, P.; Audran, M.; Clochon, P. Concentration of Bone Elements in Osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1990, 5, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, H.P.; McNally, E.A.; Botton, G.A. Dark-Field Transmission Electron Microscopy of Cortical Bone Reveals Details of Extrafibrillar Crystals. J. Struct. Biol. 2014, 188, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, H.P.; Nassif, N.; Kis, V.K. Curved Mineral Platelets in Bone. Acta Biomater. 2024, 183, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarcz, H.P.; Jasiuk, I. The Function of Citrate in Bone: Platelet Adhesion and Mineral Nucleation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 170, 107077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimcher, M.J. Recent Studies of the Mineral Phase in Bone and Its Possible Linkage to the Organic Matrix by Protein-Bound Phosphate Bonds. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1984, 304, 479–508. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, H.C. Molecular Biology of Matrix Vesicles. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1995, 314, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, J.; Sharir, A.; Addadi, L.; Weiner, S. Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Is a Major Component of the Forming Fin Bones of Zebrafish: Indications for an Amorphous Precursor Phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 12748–12753. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, M. Phosphate Metabolism in Health and Disease. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2021, 108, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, A.S.; Betts, F. Synthetic Amorphous Calcium Phosphate and Its Relation to Bone Mineral Structure. Acc. Chem. Res. 1975, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Euw, S.; Wang, Y.; Laurent, G.; Drouet, C.; Babonneau, F.; Nassif, N.; Azaïs, T. Bone Mineral: New Insights into Its Chemical Composition. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsari, A.; Rajasekharan, A.K.; Halvarsson, M.; Andersson, M. Transformation of Amorphous Calcium Phosphate to Bone-like Apatite. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, V.K.; Schwarcz, H.P.; Nassif, N.; Szekanecz, Z. Bone Mineral Platelets Are Mesocrystals Formed by Monoclinic Nanocrystals. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Han, L.; Ambrogini, E.; Bartell, S.M.; Manolagas, S.C. Oxidative Stress Stimulates Apoptosis and Activates NF-ΚB in Osteoblastic Cells via a PKCβ/P66shc Signaling Cascade: Counter Regulation by Estrogens or Androgens. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitiputri, K.; Ramasse, Q.M.; Autefage, H.; McGilvery, C.M.; Boonrungsiman, S.; Evans, N.D.; Stevens, M.M.; Porter, A.E. Nanoanalytical Electron Microscopy Reveals a Sequential Mineralization Process Involving Carbonate-Containing Amorphous Precursors. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6826–6835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Fujii, K.; Marumo, K. Degree of Mineralization-Related Collagen Crosslinking in the Femoral Neck Cancellous Bone in Cases of Hip Fracture and Controls. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2006, 79, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Marumo, K.; Kida, Y.; Ushiku, C.; Kato, S.; Takao-Kawabata, R.; Kuroda, T. Changes in the Contents of Enzymatic Immature, Mature, and Non-Enzymatic Senescent Cross-Links of Collagen after Once-Weekly Treatment with Human Parathyroid Hormone (1–34) for 18 Months Contribute to Improvement of Bone Strength in Ovariectomized Monkeys. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, T.L.; Pasquale, J.; Grynpas, M.D. Collagen Modifications in Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: Advanced Glycation Endproducts May Affect Bone Volume, Structure and Quality. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2014, 12, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, W.J.; Jacquet, R. Association of Calcium and Phosphate Ions with Collagen in the Mineralization of Vertebrate Tissues. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).