The Pressure Response of Bulk and Two−Dimensional MoS2 Crystals Studied by Raman and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Dimensionality and Pressure Transmitting Medium Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

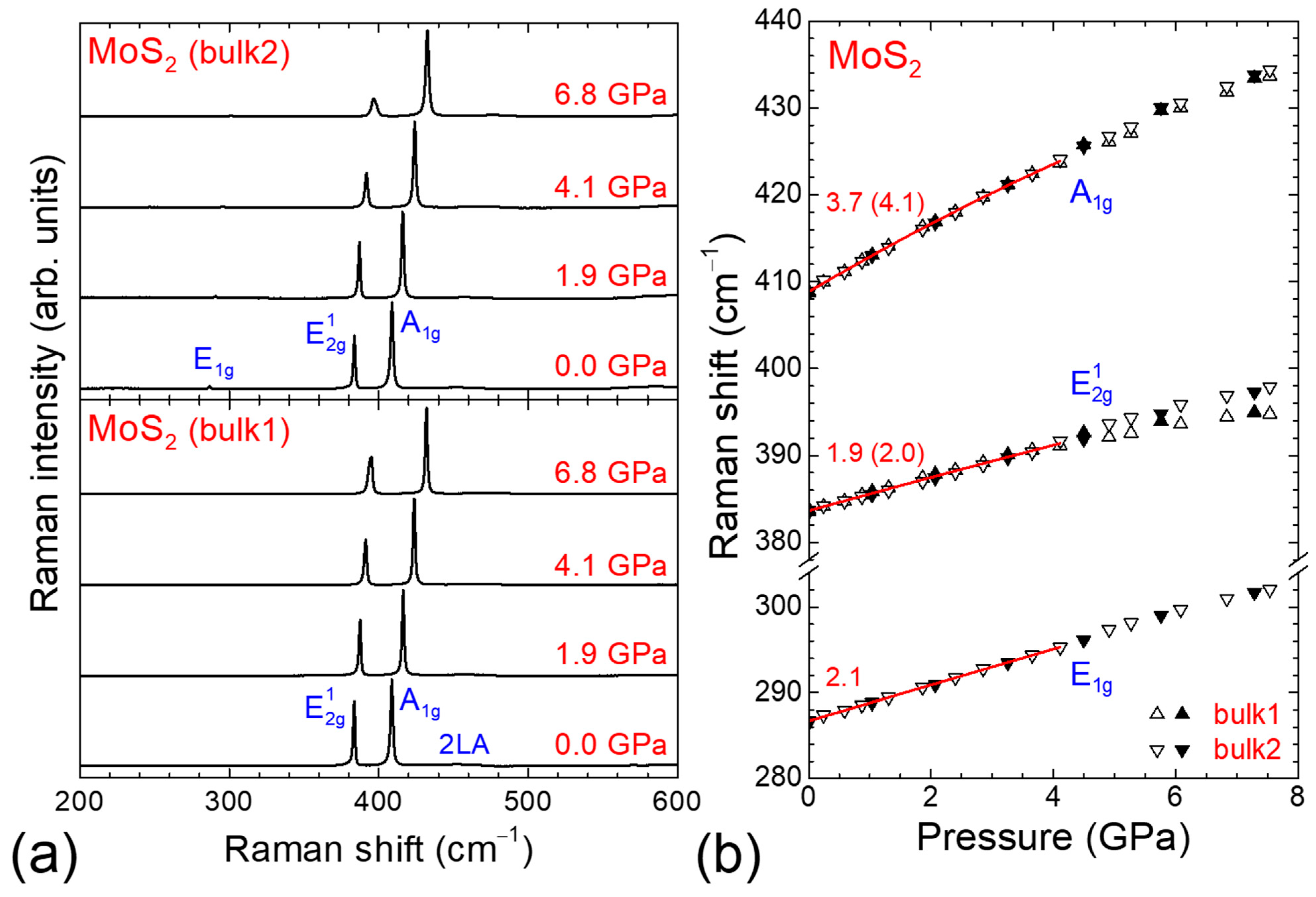

3.1. High-Pressure Raman Study of Bulk MoS2

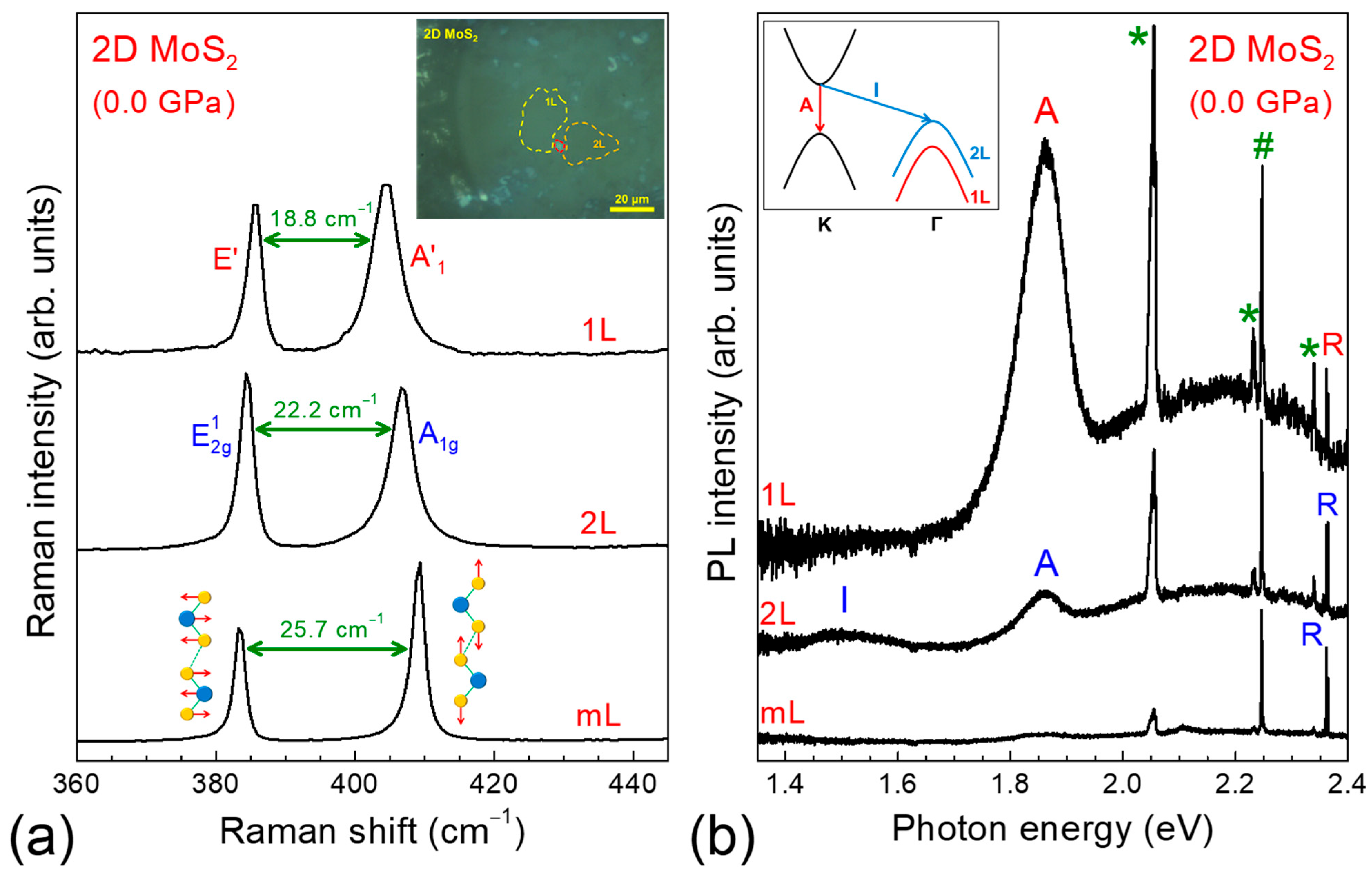

3.2. Raman and PL Spectra of 2D MoS2 at Ambient Pressure

3.3. High-Pressure Raman and PL Study of 2D MoS2

3.4. The Effect of the Pressure Transmitting Medium

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | Two−dimensional |

| DAC | Diamond anvil cell |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| PTM | Pressure-transmitting medium |

| TMD | Transition metal dichalcogenide |

| FL | Few−layered |

| 1L | Monolayer |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| mL | Many–layered |

| 2L | Bilayer |

| CB | Conduction band |

| VB | Valence band |

| 3D | Three−dimensional |

References

- He, Z.; Que, W. Molybdenum disulfide nanomaterials: Structures, properties, synthesis and recent progress on hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Mater. Today 2016, 3, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samy, O.; Zeng, S.; Birowosuto, M.D.; El Moutaouakil, A. A Review on MoS2 properties, synthesis, sensing applications and challenges. Crystals 2021, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaleghi, M.; Chaji, M.; Pishbin, F.; Sillanpää, M.; Sheibani, S. A review of molybdenum disulfide–based 3D printed structures for biomedical applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 1630–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.M.; de Conti, M.C.M.D.; Pereira, W.S.; Sczancoski, J.C.; Medina, M.; Corradini, P.G.; de Brito, J.F.; Nogueira, A.E.; Góes, M.S.; Ferreira, O.P.; et al. Recent advances in layered MX2-based materials (M = Mo, W and X = S, Se, Te) for emerging optoelectronic and photo(electro)catalytic applications. Catalysts 2024, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, A.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, O.P.; Pandey, R. Advancements in fabrication, polymorph diversity, heterostructure excitation dynamics, and multifunctional applications of leading 2D-transition metal dichalcogenides. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 151, 40–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alowakennu, M.; Khan, M.M.; Abdulwahab, K.O. Recent progress in photocatalytic applications of metals- and non-metals-doped MoS2. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2026, 201, 110082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente, E.; Santa Ana, M.A.; Mendizábal, F.; González, G. Intercalation chemistry of molybdenum disulfide. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 224, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, U.; Kaur, M.; Singh, K.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A. A synoptic review of MoS2: Synthesis to applications. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 128, 274–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounet, N.; Gibertini, M.; Schwaller, P.; Campi, D.; Merkys, A.; Marrazzo, A.; Sohier, T.; Castelli, I.E.; Cepellotti, A.; Pizzi, G.; et al. Two–dimensional materials from high–throughput computational exfoliation of experimentally known compounds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellanos–Gomez, A.; Poot, M.; Steele, G.A.; van der Zant, H.S.J.; Agraït, N.; Rubio–Bollinger, G. Elastic properties of freely suspended MoS2 nanosheets. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radisavljevic, B.; Radenovic, A.; Brivio, J.; Giacometti, V.; Kis, A. Single–layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct–gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.P.; Panda, D.K. Review–Next generation 2D material molybdenum disulfide (MoS2): Properties, applications and challenges. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 033012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Subbaiah, Y.P.; Saji, K.J.; Tiwari, A. Atomically thin MoS2: A versatile nongraphene 2D material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 2046–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundo, E.; Cappelluti, E.; Felici, M.; Pettinari, G.; Polimeni, A. Strain–tuning of the electronic, optical, and vibrational properties of two–dimensional crystals. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 021318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta Martins, L.G.; Carvalho, B.R.; Occhialini, C.A.; Neme, N.P.; Park, J.-H.; Song, Q.; Venezuela, P.; Mazzoni, M.S.C.; Matos, M.J.S.; Kong, J.; et al. Electronic band tuning and multivalley Raman scattering in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides at high pressures. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 8064–8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta Martins, L.G.; Comin, R.; Matos, M.J.S.; Mazzoni, M.S.C.; Neves, B.R.A.; Yankowitz, M. High–pressure studies of atomically thin van der Waals materials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2023, 10, 011313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel, A. Nanomaterials under high–pressure. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, X.; Ding, K.; Jiang, D.; Sun, B. Tuning and identification of interband transitions in monolayer and bilayer molybdenum disulfide using hydrostatic pressure. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7458–7464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yan, Y.; Han, B.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Yao, M.; Gong, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, B.; Zhu, C.; et al. Pressure confinement effect in MoS2 monolayers. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 9075–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.P.; Pandey, T.; Voiry, D.; Liu, J.; Moran, S.T.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C.; Chen, C.-H.; Li, L.-J.; Chhowalla, M.; et al. Pressure–dependent optical and vibrational properties of monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Li, F.; Gong, Y.; Yao, M.; Huang, X.; Fu, X.; Han, B.; Zhou, Q.; Cui, T. Interlayer coupling affected structural stability in ultrathin MoS2: An investigation by high pressure Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 24992–24998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Chu, X.; Xu, M.; Fang, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhai, Y.; et al. Pressure and temperature-dependent Raman spectra of MoS2 film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 242101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, R.S.; Saboia, K.D.A.; Machon, D.; Montagnac, G.; Meunier, V.; Ferreira, O.P.; San-Miguel, A.; Souza Filho, A.G. Atomic-layered MoS2 on SiO2 under high pressure: Bimodal adhesion and biaxial strain effects. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2017, 1, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Wan, Y.; Tang, N.; Ding, Y.-M.; Gao, J.; Yu, J.; Guan, H.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. K–Λ crossover transition in the conduction band of monolayer MoS2 under hydrostatic pressure. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, M.; Qi, Z. Anharmonicity of monolayer MoS2, MoSe2, and WSe2: A Raman study under high pressure and elevated temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 093108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, Y.; Shang, J.; Hu, C.; Ren, Y.; Liu, M.; Qi, Z. Thickness–dependent phase transition and optical behavior of MoS2 films under high pressure. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Yan, Z.; Han, J.; Lin, J.; Wang, S.; Qi, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. Tuning of optical behavior in monolayer and bilayer molybdenum disulfide using hydrostatic pressure. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Sun, H.; Fan, X.; Jin, M.; Liu, H.; Tang, T.; Xiong, L.; Niu, B.; Li, X.; Wang, G. Interlayer coupling and pressure engineering in bilayer MoS2. Crystals 2022, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, A.; Parthenios, J.N.; Anestopoulos, D.; Galiotis, C.; Christian, M.; Ortolani, L.; Morandi, V.; Papagelis, K. Controllable, eco–friendly, synthesis of highly crystalline 2D–MoS2 and clarification of the role of growth–induced strain. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 035035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.K.; Xu, J.; Bell, P.M. Calibration of the ruby pressure gauge to 800 kbar under quasi–hydrostatic conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 1986, 91, 4673–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica, A.; Rubio, A.; Muñoz, A.; Needs, R.J. High–pressure phases of group–IV, III–V, and II–VI compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2003, 75, 863–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco-López, A.; Han, B.; Lagarde, D.; Marie, X.; Urbaszek, B.; Robert, C.; Goñi, A.R. On the impact of the stress situation on the optical properties of WSe2 monolayers under high pressure. Pap. Phys. 2019, 11, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsema, K.D.; de Boer, J.L.; Jellinek, F. On the structure of molybdenum diselenide and disulfide. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1986, 540, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Yokogawa, K.; Yoshino, H.; Klotz, S.; Munsch, P.; Irizawa, A.; Nishiyama, M.; Iizuka, K.; Nanba, T.; Okada, T.; et al. Pressure transmitting medium Daphne 7474 solidifying at 3.7 GPa at room temperature. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2008, 79, 085101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Kato, S.; Kume, T.; Shimizu, H.; Okada, T.; Aoyama, S.; Kusuyama, F.; Murata, K. Elastic properties of new–pressure transmitting medium Daphne 7474 under high pressure. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 49, 106702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piermarini, G.J.; Block, S.; Barnett, J.S. Hydrostatic limits in liquids and solids to 100 kbar. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 44, 5377–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, A. Diamond anvil cell and high–pressure physical investigations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1983, 55, 65–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Sánchez, A.; Hummer, K.; Wirtz, L. Vibrational and optical properties of MoS2: From monolayer to bulk. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2015, 70, 554–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiao, X.-F.; Shi, W.; Wu, J.-B.; Jiang, D.-S.; Tan, P.-H. Phonon and Raman scattering of two–dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides from monolayer, multilayer to bulk material. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2757–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, T.; Spanier, J.E. A comprehensive multiphonon spectral analysis in MoS2. 2D Mater. 2015, 2, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yap, C.C.R.; Tay, B.K.; Edwin, T.H.T.; Olivier, A.; Baillargeat, D. From Bulk to Monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Raman Scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Matte, H.S.S.R.; Sood, A.K.; Rao, C.N.R. Layer–dependent resonant Raman scattering of a few layer MoS2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2013, 44, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar Sousa, J.H.; Araújo, B.S.; Ferreira, R.S.; San–Miguel, A.; Alencar, R.S.; Filho, A.G.S. Pressure tuning resonance Raman scattering in monolayer, trilayer, and many–layer molybdenum disulfide. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 14464–14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B.R.; Pimenta, M.A. Resonance Raman spectroscopy in semiconducting transition–metal dichalcogenides: Basic properties and perspectives. 2D Mater. 2020, 7, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livneh, T.; Eran Sterer, E. Resonant Raman scattering at exciton states tuned by pressure and temperature in 2H–MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 195209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-J.; Li, H.-P.; Dai, L.-D.; Hu, H.-Y.; Zhao, C.-S. Raman scattering of 2H–MoS2 at simultaneous high temperature and high pressure (up to 600 K and 18.5 GPa). AIP Adv. 2016, 6, 035214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Liu, B.; Yang, X.; Dong, Q.; Cui, T.; Liu, B. Raman and IR spectroscopic characterization of molybdenum disulfide under quasi–hydrostatic and non–hydrostatic conditions. Phys. Status Solidi B 2017, 254, 1600798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liang, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yan, L.; Tan, W.; Lu, M.; Lu, M. Theoretical and experimental Raman study of molybdenum disulfide. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2021, 156, 110154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, R.; Ma, Y.; Selvi, E.; Chyu, M.C.; Ertas, A.; White, A. X–ray diffraction study of molybdenum disulfide to 38.8 GPa. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2006, 67, 1914–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, N.; Kumar, R.S.; Sneed, D.; Tschauner, O.; Baker, J.; Antonio, D.; Luo, S.-N.; Hartmann, T.; Zhao, Y.; Venkat, R. Effect of pressure and temperature on structural stability of MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 3230–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnall, A.G.; Liang, W.Y.; Marseglia, E.A.; Welber, B. Raman studies of MoS2 at high pressure. Phys. B+C 1980, 99, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, S.; Ueda, T. High–pressure Raman spectroscopy in the layered materials 2H–MoS2, 2H–MoSe2, and 2H–MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 26, 6554–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, M.A.; del Corro, E.; Carvalho, B.R.; Fantini, C.; Malard, L.M. Comparative study of Raman spectroscopy in graphene and MoS2-type transition metal dichalcogenides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yan, H.; Brus, L.E.; Heinz, T.F.; Hone, J.; Ryu, S. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single- and few-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, Q.; Quek, S.Y. Anomalous frequency trends in MoS2 thin films attributed to surface effects. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 075320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuschner, N.; Ochedowski, O.; Kaulitz, A.-M.; Gillen, R.; Schleberger, M.; Maultzsch, J. Photoluminescence of freestanding single– and few–layer MoS2. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 125406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cong, C.; Qiu, C.; Yu, T. Raman spectroscopy study of lattice vibration and crystallographic orientation of monolayer MoS2 under uniaxial strain. Small 2013, 9, 2857–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Á.; Çakıroğlu, O.; Li, H.; Carrascoso, F.; Mompean, F.; Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Munuera, C.; Castellanos-Gomez, A. Improved strain transfer efficiency in large-area two-dimensional MoS2 obtained by gold-assisted exfoliation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 6355–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Montakim Tareq, A.; Qi, K.; Conti, Y.; Tung, V.; Chiang, N. High-resolution distance dependence interrogation of scanning ion conductance microscopic tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy enabled by two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide substrates. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 13805–13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filintoglou, K.; Papadopoulos, N.; Arvanitidis, J.; Christofilos, D.; Frank, O.; Kalbac, M.; Parthenios, J.; Kalosakas, G.; Galiotis, C.; Papagelis, K. Raman spectroscopy of graphene at high pressure: Effects of the substrate and the pressure transmitting media. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 045418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ves, S.; Cardona, M. A new application of the diamond anvil cell: Measurements under uniaxial stress. Solid State Commun. 1981, 38, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacha, A.; Ves, S.; Cardona, M. Effects of uniaxial strain on the exciton spectra of CuCl, CuBr, and CuI. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 6346–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. Physical Properties of Crystals: Their Representation by Tensors and Matrices; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassakis, E.; Cardona, M. Phonons, strains, and pressure in semiconductors. Semicond. Semimet. 1998, 55, 117–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J. Elastic constants of 2H–MoS2 and 2H–NbSe2 extracted from measured dispersion curves and linear compressibilities. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1976, 37, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre-Louis, O. Adhesion of membranes and filaments on rippled surfaces. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 78, 021603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolle, J.; Machon, D.; Poncharal, P.; Pierre-Louis, O.; San-Miguel, A. Pressure–mediated doping in graphene. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3564–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, A.W.; Feldman, J.L.; Skelton, E.F.; Towle, L.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Spain, I.L. High pressure investigations of MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1976, 37, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, H.; Wang, B.; Ziegler, J.; Haglund, R.F.; Pantelides, S.T.; Bolotin, K.I. Bandgap engineering of strained monolayer and bilayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 3626–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Chang, C.-H.; Zheng, W.; Kuo, J.-L.; Singh, D.J. The electronic properties of single–layer and multilayer MoS2 under high pressure. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 10189–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Q. Probing anisotropic deformation and near–infrared emission tuning in thin–layered InSe crystal under high pressure. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 3493–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, A.; Delikoukos, N.; Parthenios, J.; Galiotis, C.; Papagelis, K. Optical detection of strain and doping inhomogeneities in single layer MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 173102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, K.; Goto, K.; Klotz, S.; Bhoi, D.; Béneut, K.; Uwatoko, Y.; Yoshino, H.; Aoki, S. A new pressure medium, Daphne 7676, with solidification pressure of 5 GPa at 300 K and low melting point of around 110 K at ambient pressure. High Press. Res. 2025, 45, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, J.E.; Gregoryanz, E.; Novoselov, K.S.; Lotya, M.; Coleman, J.N.; Halsall, M.P. High–pressure Raman spectroscopy of graphene. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 073408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorogas, N.; Tersis, K.; Michail, A.; Ves, S.; Papagelis, K.; Christofilos, D.; Arvanitidis, J. The Pressure Response of Bulk and Two−Dimensional MoS2 Crystals Studied by Raman and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Dimensionality and Pressure Transmitting Medium Effects. Crystals 2025, 15, 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121056

Sorogas N, Tersis K, Michail A, Ves S, Papagelis K, Christofilos D, Arvanitidis J. The Pressure Response of Bulk and Two−Dimensional MoS2 Crystals Studied by Raman and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Dimensionality and Pressure Transmitting Medium Effects. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121056

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorogas, Niki, Krystallis Tersis, Antonios Michail, Sotirios Ves, Konstantinos Papagelis, Dimitrios Christofilos, and John Arvanitidis. 2025. "The Pressure Response of Bulk and Two−Dimensional MoS2 Crystals Studied by Raman and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Dimensionality and Pressure Transmitting Medium Effects" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121056

APA StyleSorogas, N., Tersis, K., Michail, A., Ves, S., Papagelis, K., Christofilos, D., & Arvanitidis, J. (2025). The Pressure Response of Bulk and Two−Dimensional MoS2 Crystals Studied by Raman and Photoluminescence Spectroscopy: Dimensionality and Pressure Transmitting Medium Effects. Crystals, 15(12), 1056. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121056