Abstract

This study investigates the effect of electrolytic-plasma hardening time on the microstructure formation, hardness distribution, and corrosion behavior of grade 45 structural steel. The treatment was performed in a 15% aqueous sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution at an applied voltage of 300 V for different holding times (8, 10, and 12 s). Scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction analyses revealed that increasing the EPH duration promotes the formation of a more uniform martensitic layer and reduces the amount of residual cementite. Microhardness measurements showed an increase in surface hardness from 190 HV for the untreated steel to 770 HV after the longest treatment. The cross-sectional hardness profile indicated the presence of a thin decarburized sublayer and a zone of maximum hardness corresponding to the martensitic structure. Potentiodynamic polarization tests in a 0.5 M NaCl solution showed a slight increase in corrosion current density after treatment; however, the corrosion rate remained within the range of 0.19–0.45 mm year−1, confirming the satisfactory corrosion resistance of the hardened layer. The results demonstrate that controlling the EPH duration allows for optimizing the balance between enhanced hardness and maintained corrosion resistance of grade 45 steel.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, extending the service life of machine components through targeted modification of surface layers has been recognized as one of the key approaches to saving materials and energy. Medium-carbon steel grade 45 is widely used for friction units, shafts, axles, and drive components due to its good processability, low cost, and suitability for strengthening heat treatments [1]. However, its performance in aggressive or impact–abrasive environments is largely determined by the condition of the surface layer—specifically, the hardness distribution with depth, the presence of residual stresses, and corrosion behavior.

A review of the heat treatment of low- and medium-carbon steels shows that an increased fraction of martensite and finer carbide dispersion lead to maximum hardness; however, variations in quenching and tempering parameters can significantly influence both the corrosion resistance and fracture toughness of the material [2].

Traditional surface-hardening methods for grade 45 steels—such as high-frequency induction hardening, laser or electron-beam hardening, carburizing, and nitrocarburizing—provide high hardness and wear resistance but require complex equipment, substantial energy input, and are often accompanied by deformation or overheating of large components [2]. Moreover, many of these technologies must be conducted in vacuum or controlled atmospheres, which complicates their industrial implementation.

Against this background, electrolytic plasma processing (EPP) has emerged as a promising alternative. It is performed in aqueous solutions under atmospheric pressure, provides extremely high heating and cooling rates, and allows for flexible control of processing parameters by adjusting the electrolyte composition, current density, and holding time [3,4,5,6]. Electrolytic-plasma hardening and related treatments (such as electrolytic-plasma saturation, nitriding, and boriding) operate through the formation of a gas–plasma sheath around the cathodic sample, accompanied by micro-discharges in the thin electrolyte layer. These discharges rapidly raise the surface temperature above the austenitization point within fractions of a second; upon power shut-off, the surface is instantly cooled in the same electrolyte, forming a hardened layer [3,4]. Depending on the solution composition, polarity, and electrical mode, the process can be used not only for hardening but also for chemical surface modification (e.g., nitrogen or boron enrichment), cleaning, and polishing [5,6].

In recent years, numerous studies have been devoted to electrolytic-plasma hardening and saturation of grade 45 steels. In particular, it has been shown that electrolytic-plasma hardening in carbonate electrolytes leads to the formation of a martensitic layer several millimeters thick, accompanied by a 2–3-fold increase in microhardness and enhanced wear resistance under dry friction conditions [7]. Electrolytic-plasma nitriding of grade 45 steel in solutions based on urea and ammonium nitrate forms nitrogen-containing phases (γ’-Fe4N and ε-Fe2–3N) on the surface, resulting in a significant improvement in contact endurance and performance in aggressive environments [8].

Investigations of wheel and rail steels have demonstrated that EPP produces a gradient-layered structure—from highly dispersed martensite at the surface to troostite–martensite and ferrite–pearlite layers deeper within—which reduces stress concentration at the hardened-layer boundary and enhances contact fatigue strength [9,10,11].

A particular area of interest is the formation of gradient structures in steels and alloys, where properties gradually vary from the surface to the core. Such structures combine high surface hardness and wear resistance with a sufficiently ductile and impact-resistant substrate, thereby reducing the likelihood of crack initiation and propagation [12,13,14]. Functionally graded layers in steels can be produced by both diffusion-based processes (carburizing, nitriding, boriding) and controlled decarburization during high-temperature treatment. It has been shown that a controlled gradient in carbon content and dislocation density can significantly increase contact fatigue resistance and slow the progression of corrosion–mechanical damage [12,15].

At extreme temperatures and in oxidizing atmospheres, surface decarburization becomes an inevitable accompanying effect. For chromium–molybdenum and structural steels, it has been shown that the depth of fully and partially decarburized layers strongly depends on temperature and holding time, reaching its maximum within a narrow range of austenitizing temperatures [15,16]. Under electrolytic-plasma hardening (EPH) conditions, where high temperatures, intense electrolyte boiling, and electrical discharges occur simultaneously, one can expect competing processes of hardening (martensite formation and residual compressive stress development) and surface decarburization or oxidation. However, quantitative data on how these processes manifest in the gradient profiles of microhardness and phase composition remain limited.

The corrosion behavior of hardened steels is determined not only by their chemical composition but also by the state of the surface layer—specifically, by phase transformations, residual stresses, and the presence of microgalvanic couples. For quenched and tempered structural steels, it has been shown that variations in the fractions of martensite, cementite, and retained austenite, as well as changes in tempering conditions, can either enhance or deteriorate corrosion resistance in aqueous and chloride-containing media [16,17]. Studies on electrolytic-plasma hardening of grade 45 and 65 G steels have reported significant changes in tribological and corrosion properties compared with the initial state; however, the direction of the effect (improvement or degradation of corrosion resistance) depends on the electrolyte composition, processing parameters, and structure of the formed layer [18,19]. This highlights the need for a comprehensive structure–hardness–corrosion analysis for specific EPP systems and processing modes.

Despite the active development of electrolytic-plasma technologies, most studies have focused on the influence of electrolyte composition, additives (such as urea, ammonium nitrate, or boric acid), or current polarity [4,5,6,8]. The effect of electrolytic-plasma hardening time—one of the key parameters governing the balance between heating rate, phase transformations, decarburization, and residual stress formation—has been studied far less comprehensively, particularly for the widely used grade 45 steel [20,21]. It remains unclear how variations in the holding time influence:

(i) The morphology and phase composition of the surface layer (martensite, bainite, retained pearlite, carbide phases);

(ii) The microhardness gradient from the surface to the core, including the possible formation of a decarburized sublayer;

(iii) The corrosion behavior in aqueous electrolytes, where structural and electrochemical factors act simultaneously.

In this context, grade 45 steel was selected as a model material representative of general engineering components. The objective of this study is to elucidate the effect of electrolytic-plasma hardening (EPH) time on the formation of gradient microstructures, microhardness distribution, and corrosion behavior in grade 45 steel.

Overall, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how variations in EPH time can be used to control the structure and properties of the gradient layer in grade 45 steel, highlighting the trade-off between increased hardness and corrosion performance. The obtained results provide a basis for optimizing electrolytic-plasma hardening modes for grade 45 and other medium-carbon steels used in engineering applications.

2. Materials and Methods

Samples of structural carbon steel grade 45 were used for electrolytic plasma hardening. The chemical composition of the steel is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of steel 45, wt.%.

Samples with dimensions of 20 × 20 × 15 mm were cut from the base material. Prior to processing, the surfaces were cleaned of contaminants by wiping with ethyl alcohol and then air-dried at room temperature. This preliminary treatment ensured the removal of grease films and particulate impurities that could affect the reproducibility of the experimental results.

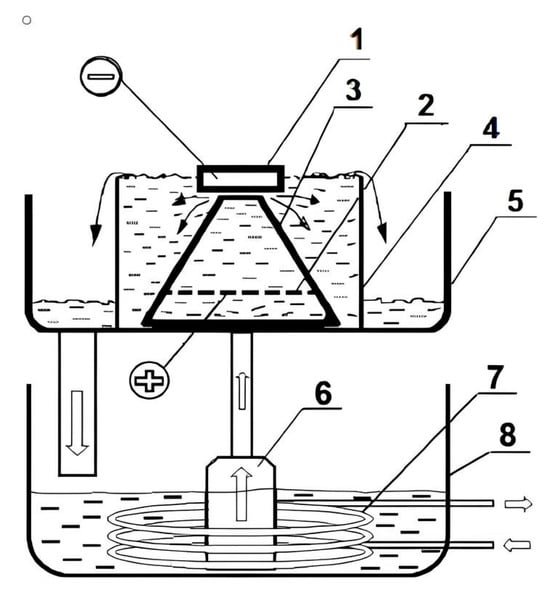

Electrolytic plasma hardening (EPH) was performed on a pilot plant. A 40 kW power source provided voltage up to 380 V and current up to 150 A. The plant diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Electrolytic plasma hardening diagram: 1—sample being processed (cathode); 2—stainless steel anode; 3—cone-shaped partition; 4—electrolytic cell; 5—tray; 6—pump; 7—heat exchanger; 8—electrolyte bath.

A 15% aqueous solution of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) was used as the electrolyte. Heat exchange between the plasma and the metal occurred with a high heat flux density, ensuring rapid heating of the surface layer. After reaching the required heating time, the current was interrupted, and cooling occurred in the same electrolyte, which served as the quenching medium. Electrolyte circulation was used to increase the cooling intensity and maintain temperature stability in the bath. The main parameters of electrolytic-plasma processing are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of EPH Regimes for Steel 45.

The microstructure of the surface layers was examined using a Tescan Vega 3 scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) in both secondary and backscattered electron modes. Before SEM examination, the cross-sections were etched using 4% nitric acid in 96% ethyl alcohol (Nital 4%) for 10 s, rinsed with ethanol, and dried in air. The phase composition of the hardened layers was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using an X’Pert PRO diffractometer (PANalytical, Bruker, Germany) within the angular range of 2θ = 20–90°, with a step size of 0.02°. Microhardness measurements were performed using an HLV-1DT tester (Shanghai Hualong Test Instruments Corporation, Shanghai, China) under a load of 0.2 N with a dwell time of 10 s. The obtained values from at least ten measurements were averaged for each sample. Corrosion resistance was evaluated by potentiodynamic polarization using a Corrtest CS300M potentiostat/galvanostat (Corrtest Instruments, Wuhan, China) in a 0.5 M NaCl solution at 25 °C. Prior to recording the polarization curves, the open-circuit potential (OCP) was monitored for 400 s until stabilization. An Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference while a platinum mesh served as the counter electrode. Before testing, the sample surfaces were ground with SiC papers up to 1200 grit, polished, ultrasonically cleaned in ethanol for 5 min, and dried in air. The electrochemical measurements were carried out using a standard corrosion cell in which the working area of the sample is mechanically defined as 1.0 cm2 based on the cell geometry; therefore, no additional insulation of the remaining sample surface was required. Only this exposed 1 cm2 region was in contact with the electrolyte during the polarization scan. All measurements were carried out at least three times, and the statistical significance of the results was assessed using Student’s t-test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

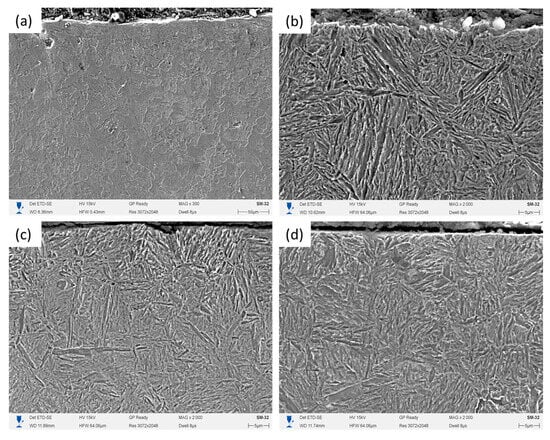

Figure 2 presents SEM images of the surface layer of the untreated steel (Figure 2a) and the samples subjected to EPH for 8, 10, and 12 s (Figure 2b–d). After EPH, the surface layer transforms into a characteristic acicular martensitic morphology. The martensitic laths become increasingly well-defined and uniformly distributed as the treatment time increases, which is consistent with earlier observations for electrolytic-plasma hardening of medium-carbon steels [22,23]. The near-surface region also contains a thin carbon-depleted (decarburized) sublayer, which appears as a relatively smoother band directly beneath the surface and results from oxidation and carbon loss during plasma exposure [24].

Figure 2.

Microstructure of the surface layer of steel after electrolytic plasma hardening: (a) untreated steel; (b) No. 1; (c) No. 2; (d) No. 3.

At the shortest treatment time (8 s), the surface exhibits a heterogeneous morphology consisting of both partially transformed and more developed martensitic regions. The mixture of morphologies indicates that austenitization was not yet fully completed at this duration, which is consistent with previous reports on short-time plasma hardening where incomplete transformation is confined to the near-surface zone [25].

With an increase in exposure time to 10 s, the martensitic morphology becomes more homogeneous, and the acicular crystals appear more uniformly distributed across the surface. Although differences between the 10 s and 12 s samples are subtle at this magnification, a general trend toward structural homogenization with increasing treatment time is observed, in agreement with the literature data on EPH-treated steels [26].

After 12 s of treatment, the surface layer shows a predominantly martensitic morphology with densely packed lath-type crystals. The microstructure remains largely uniform across the examined area; local variations in surface relief may be associated with oxidation-induced carbon depletion near the surface, consistent with the formation of a thin decarburized sublayer [27].

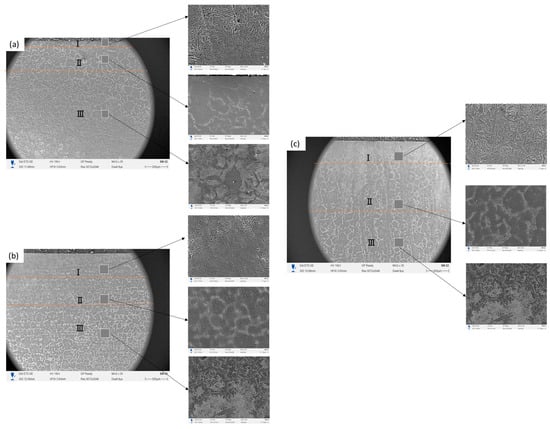

Figure 3 presents a combined macro–microstructural view of the hardened layers obtained after EPH treatment. The low-magnification cross-sectional image reveals three distinct regions: (I) the near-surface zone, (II) the transition region, and (III) the underlying base metal. As the treatment time increases (a → b → c), the contrast and visibility of the hardened region become sharper, reflecting the gradual development of a deeper thermally affected layer. Zone I corresponds to the surface region where rapid heating and quenching during EPH promote the formation of a martensitic microstructure. The high-magnification images show densely packed acicular features at the surface for all samples, with increasing homogeneity from No. 1 to No. 3. Local smooth areas in Zone I are associated with the thin decarburized sublayer formed as a result of oxidation and carbon depletion. Zone II represents the transition region between the hardened surface and the base metal. In this area, the microstructure gradually changes from predominantly martensitic to a mixture of partially transformed constituents. This zone visually coincides with the region of decreasing microhardness on the hardness profile. The micrographs confirm the presence of less pronounced martensitic features and an increasing fraction of partially transformed structures as depth increases, consistent with partial austenitization during EPH and subsequent diffusion-controlled cooling. Zone III corresponds to the unaffected base metal. The SEM micrograph shows the typical ferrite–pearlite morphology of grade 45 steel, and this region corresponds to the area where the microhardness reaches values characteristic of the untreated material. No structural modifications are observed here, confirming that the thermal influence of EPH is limited to the upper part of the sample and does not extend into the core.

Figure 3.

Cross-section of steel after EPH: I—hardened layer; II—transition zone; III—original matrix. (a) No. 1; (b) No. 2; (c) No. 3.

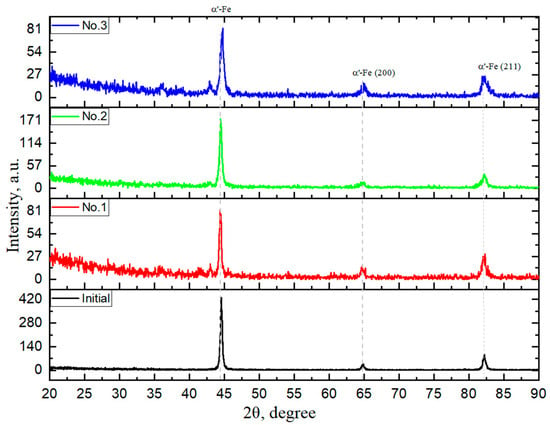

Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the initial steel and the samples after electrolytic-plasma hardening (EPH) at different treatment times. All diffraction patterns are dominated by α-Fe reflections with a body-centered cubic (bcc) structure, located at 2θ ≈ 44.5°, 64.7°, and 82.1°, which correspond to the (110), (200), and (211) planes, respectively [28,29,30,31]. Within the resolution limits of the XRD method, no additional diffraction peaks corresponding to new crystalline phases were detected after electrolytic-plasma treatment.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction patterns of grade 45 steel samples before and after electrolytic-plasma hardening.

The diffraction pattern of the initial steel is characterized by sharp α-Fe peaks typical of ferrite–pearlite microstructure. After EPH for 8 s (sample No. 1), the α-Fe reflections remain dominant, indicating that the primary crystal structure of steel is preserved during short-term plasma exposure. These results are consistent with previously reported data on electrolytic-plasma treatment of medium-carbon steels, where martensitic transformation occurs without the formation of detectable secondary crystalline phases [28,29,30,31].

With an increase in treatment duration to 10 s and 12 s (samples No. 2 and No. 3), the positions of the α-Fe peaks remain unchanged, confirming the structural stability of the bcc iron phase after high-temperature plasma exposure and rapid quenching. Minor changes in peak width and shape were observed; however, no quantitative analysis was performed due to the absence of profile refinement methods such as Rietveld analysis or Williamson–Hall evaluation. Therefore, phase interpretation in this study is based exclusively on peak positions rather than on peak intensities [5,32,33].

Overall, the XRD results indicate that increasing the EPH duration promotes martensitic transformation of the near-surface layer while maintaining the α-Fe bcc phase as the dominant crystalline structure. This conclusion is in good agreement with the SEM observations and microhardness results, which demonstrate progressive structural refinement and hardening of the surface layer with increasing treatment time.

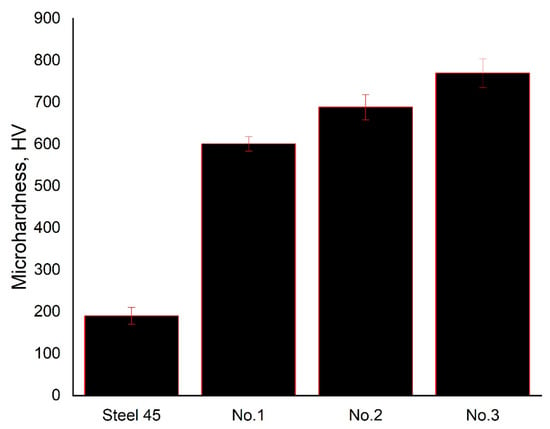

Figure 5 shows the surface layer microhardness values of the original cast steel and samples after electrolytic plasma hardening at different treatment times. The original steel is characterized by a microhardness of approximately HV = 190 ± 20 HV. After EPH, a sharp increase in hardness is recorded:

Figure 5.

Variation in the microhardness of the surface layer of grade 45 steel before and after electrolytic-plasma hardening.

For sample No. 1, the average value is HV = 601 ± 41 HV, ε ≈ 6.8%, α = 0.95;

For sample No. 2, HV = 689 ± 58 HV, ε ≈ 8.4%, α = 0.95;

For sample No. 3, HV = 770 ± 81 HV, ε ≈ 10.5%, α = 0.95.

Thus, the surface microhardness increases by approximately 3–4 times compared to the original steel, and with increasing processing time, a monotonous increase in the hardness level and a slight increase in the spread of values is observed, which is associated with a more pronounced heterogeneity of the hardened layer.

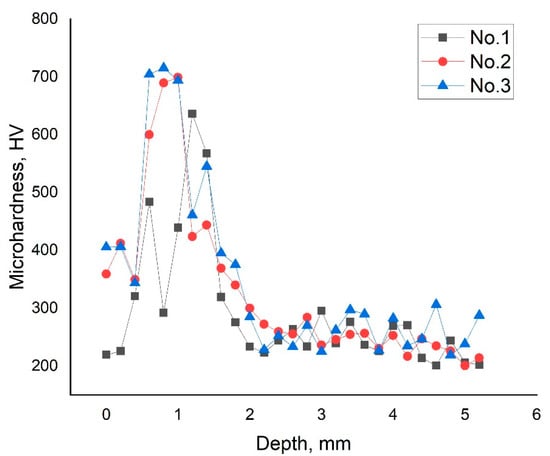

The microhardness profiles of the hardened samples (Figure 6) exhibit a clearly zonal character, which corresponds well to the microstructural gradient revealed in the cross-sectional macro–micrographs. In all cases, the first points near the surface show reduced hardness compared with the underlying hardened region. This decrease is attributed to the thin decarburized sublayer formed during plasma exposure, where local carbon depletion leads to lower hardness values. For sample No. 1, the hardness in this zone lies in the range of approximately 220–320 HV, whereas for sample No. 3, it reaches 340–400 HV, reflecting the greater thermal impact at longer treatment times. Beneath the decarburized region lies the zone of maximum hardness, associated with the formation of a predominantly martensitic microstructure. The peak hardness reaches ~600–650 HV for sample No. 1, ~650–700 HV for sample No. 2, and ~700–750 HV for sample No. 3. The increase in peak hardness with increasing EPH duration is consistent with the progressive enlargement of the fully transformed martensitic zone observed. At deeper locations, the hardness gradually decreases and approaches 200–280 HV, corresponding to the transition to the unaffected base metal. This depth region coincides with Zone III in the macrograph where the initial ferrite–pearlite structure is preserved. The alignment between the hardness gradient and the microstructural zones confirms that the hardened depth increases with increasing treatment time, which is in agreement with the general trend observed for medium-carbon steels subjected to EPH.

Figure 6.

Depth distribution of microhardness in the surface layer of grade 45 steel after electrolytic-plasma hardening.

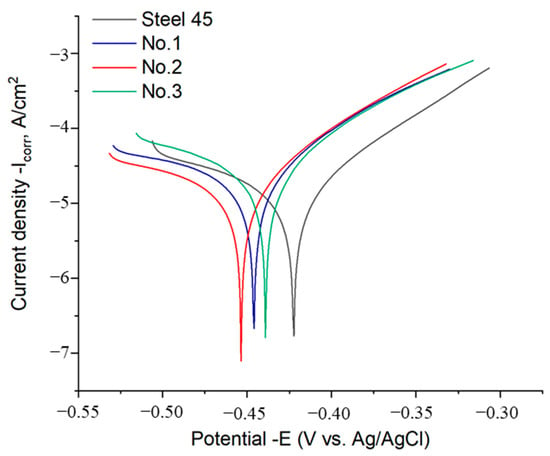

The potentiodynamic polarization curves of the initial and EPH-treated samples are shown in Figure 7, and the corresponding electrochemical parameters are listed in Table 3. Electrolytic-plasma treatment noticeably modifies the corrosion behavior of grade 45 steel. For the initial material, the corrosion current density is 1.52 ± 0.45 × 10−5 A·cm−2, whereas all treated samples exhibit higher Icorr values. This increase indicates a moderate reduction in corrosion resistance after EPH, which is primarily associated with surface-related factors rather than bulk microstructural transformations.

Figure 7.

Polarization curves of the samples.

Table 3.

Electrochemical parameters of corrosion of steel 45 and samples after electrolytic-plasma hardening.

The EPH process produces a modified surface relief that includes local oxidation, partial decarburization, and changes in roughness due to rapid heating and cooling. These effects influence the electrochemical response of the surface and contribute to the observed increase in corrosion current density. Importantly, no microcracks were observed in the SEM images of the hardened layers; therefore, this factor was excluded from the interpretation, as recommended by the reviewer.

Among the treated samples, the highest corrosion current density is observed for sample No. 3 (3.85 ± 0.78 × 10−5 A·cm−2). This behavior may be related to the more pronounced modification of the surface condition at longer treatment times, including increased surface roughness and oxidation, as well as the higher fraction of martensitic structure in the near-surface region. These factors can enhance the electrochemical activity of the surface even though the underlying hardened layer exhibits improved mechanical properties.

Overall, the corrosion behavior does not directly correlate with the linear trends observed in the microhardness or XRD results. This is expected, as corrosion is highly sensitive to surface phenomena—such as oxidation, carbon depletion, and microrelief—rather than only to the bulk martensitic transformation within the hardened layer.

The corrosion potential varied within the range from −0.379 V (original steel 45) to −0.413 V (sample No. 2), demonstrating a slight shift to the negative side. This indicates an increase in the thermodynamic tendency to oxidation, but the corrosion rate remained at an acceptable level. The average corrosion rate (r) was 0.188–0.452 mm/year, with the lowest value characteristic of the original steel 45 and the highest observed with sample No. 3. Despite a slight increase in the corrosion current after treatment, the obtained corrosion rate values remain within the range characteristic of hardened carbon steels, which confirms the satisfactory stability of the formed layer in the NaCl environment [8,9,17].

Thus, it can be concluded that electrolytic-plasma hardening leads to a change in the electrochemical properties of steel 45, but the resulting surface layers retain sufficient corrosion resistance for further use of the material in aggressive environments.

4. Conclusions

Electrolytic plasma hardening (EPH) of grade 45 steel was carried out in a 15% Na2CO3 aqueous electrolyte at a voltage of 300 V with treatment durations of 8, 10, and 12 s. The results demonstrate that processing time is a key parameter controlling microstructure evolution, hardness distribution, and corrosion behavior of the modified surface layers.

With increasing EPH time, the microstructure of grade 45 steel evolves from a mixed ferrite–pearlite state toward a predominantly martensitic structure. SEM observations revealed progressive refinement and homogenization of the martensitic morphology with longer treatment duration, indicating more complete austenitization followed by rapid quenching.

Surface microhardness increased from 190 HV for the untreated steel to 601 ± 41 HV, 689 ± 58 HV, and 770 ± 81 HV for samples treated for 8, 10, and 12 s, respectively. This systematic increase confirms the effectiveness of EPH in enhancing the mechanical performance of medium-carbon steel. Cross-sectional microhardness profiles revealed a pronounced gradient structure consisting of a thin decarburized subsurface layer and an underlying zone of maximum hardness associated with a refined martensitic structure. The thickness of the hardened layer increased with processing time, reflecting progressive thermal penetration and structural transformation.

Electrochemical measurements in 0.5 M NaCl solution showed a moderate increase in corrosion current density after EPH treatment, accompanied by a slight shift in the corrosion potential toward more negative values. Although the corrosion rate increased from 0.188 mm·year−1 for the untreated steel to 0.452 mm·year−1 for the longest treatment duration, the overall corrosion resistance of the modified layers remained within the range typical for hardened carbon steels.

Based on the combined microstructural, mechanical, and electrochemical results, an EPH treatment duration of 8–10 s at 300 V provides an optimal balance between enhanced surface hardness and acceptable corrosion resistance. This processing mode enables the formation of a dense martensitic surface layer with sufficient electrochemical stability, making electrolytic plasma hardening a promising technique for improving the durability of steel components operating in chloride-containing environments.

Future work will focus on systematic investigation of surface oxidation phenomena induced by electrolytic-plasma treatment and their correlation with corrosion behavior. The non-linear dependence observed between EPH duration and electrochemical parameters suggests that oxide layer formation plays an important role in determining corrosion performance and requires further study using surface-sensitive characterization techniques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and A.S.; methodology, A.S. and B.R.; software, A.Z.; validation, Y.M., B.R. and N.K.; formal analysis, A.Z. and N.K.; investigation, K.O. and N.K.; resources, N.I.; data curation, A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.M. and B.R.; visualization, K.O.; supervision, Y.M.; project administration, Y.M.; funding acquisition, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19178097).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Becerra, L.H.C. A review of heat treatments applied to low and medium and high carbon steels used in cold drawn. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berton, E.M.; das Neves, J.C.K.; Mafra, M.; Borges, P.C. Quenching and tempering effect on the corrosion resistance of nitrogen martensitic layer produced by SHTPN on AISI 409 steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 395, 125921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, W.; Lin, J.; Hao, G.; Qu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, H. Electrolytic plasma processing-an innovative treatment for surface modification of 304 stainless steel. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, B.; Wu, J. Review of cathode plasma electrolysis treatment: Progress, applications, and advancements in metal coating preparation. Materials 2024, 17, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletis, E.I.; Nie, X.; Wang, F.L.; Jiang, J.C. Electrolytic plasma processing for cleaning and metal-coating of steel surfaces. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002, 150, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbad, V.R.; Chel, A.; Verma, U.; Kaushik, G. Application of electrolytic plasma process in surface improvement of metals: A review. Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 2020, 9, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.; Kussainov, R.; Kalitova, A.; Satbayeva, Z.; Shynarbek, A. The impact of technological parameters of electrolytic-plasma treatment on the changes in the mechano-tribological properties of steel 45. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2024, 11, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satbayeva, Z.; Maulit, A.; Ispulov, N.; Baizhan, D.; Rakhadilov, B.; Kusainov, R. Electrolytic plasma nitriding of medium-carbon steel 45 for performance enhancement. Crystals 2024, 14, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.K.; Tabiyeva, Y.Y.; Uazyrkhanova, G.K.; Zhurerova, L.G.; Popova, N.A. Effect of electrolyte-plasma surface hardening on structure wheel steel 2. Bull. Karaganda Univ. Phys. Ser. 2020, 98, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsembayeva, T. Gradient-layered structure formed on the surface of the wheel steel during plasma quenching. Sci. Bull. Kazakh Agrotech. Univ. Named After S. Seifullin Multidiscip. 2020, 2. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossanova, I.M.; Kanayev, A.T.; Jaksymbetova, M.A.; Akhmedyanov, A.U.; Kirgizbayeva, K.Z. Effect of Electrolytic-Plasma Surface Treatment on Structure, Mechanical, and Tribological Properties of Grade 1 Wheel Steel. Metallurgist 2022, 66, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Yang, B. Research Progress of Gradient Nanostructured Steels. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 3706–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.X.; Wang, Q.; Hou, J.P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, Z.F.; Langdon, T.G. The nature of the maximum microhardness and thickness of the gradient layer in surface-strengthened Cu-Al alloys. Acta Mater. 2021, 215, 117073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wu, G.; Zhang, X.; Fu, W.; Hansen, N.; Huang, X. Gradient microstructure in a gear steel produced by pressurized gas nitriding. Materials 2019, 12, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.M. Functionally Graded Martensitic Stainless Steel Obtained Through Partial Decarburization. Ph.D. Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Feng, G.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Lin, P.; Wang, N.; Zheng, J. Characterization of surface decarburization and oxidation behavior of Cr–Mo cold heading steel. High Temp. Mater. Process. 2022, 41, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-rubaiey, S.I.; Anoon, E.A.; Hanoon, M.M. The influence of microstructure on the corrosion rate of carbon steels. Eng. Technol. J. 2013, 31, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.K.; Kussainov, R.; Bakyt, Z.; Baizhan, D.; Kadyrbolat, N. Tribological and corrosion properties of 45 and 65g steels used in agricultural machinery after electrolytic-plasma hardening. Shakarim Univ. Bulletin. Tech. Sci. Ser. 2024, 3, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhadilov, B.K.; Bayatanova, L.B.; Satbayeva, Z.A.; Kozhanova, R.S.; Yerbolatova, G.U.; Sakenova, R.Y. Investigation of changes in phase composition and tribological properties of 65G steel during electrolyte-plasma hardening. Bull. Karaganda Univ. Phys. Ser. 2023, 111, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagdoldina, Z.; Zhurerova, L.; Tyurin, Y.; Baizhan, D.; Kuykabayeba, A.; Abildinova, S.; Kozhanova, R. Modification of the Surface of 40 Kh Steel by Electrolytic Plasma Hardening. Metals 2022, 12, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombayev, K.; Kim, A.; Yelemanov, D.; Sypainova, G. Strengthening of low-carbon alloy steel by electrolytic-plasma hardening. Int. Rev. Mech. Eng. (I. RE. ME) 2022, 16, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.J.; Hu, X.; Sun, X.; Ren, Y.; Choi, K.; Barker, E.; Speer, J.G.; Matlock, D.K.; De Moor, E. Austenite formation and cementite dissolution during intercritical annealing of a medium-manganese steel from a martensitic condition. Mater. Des. 2021, 203, 109598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostryzhev, A.G.; Rizwan, M.; Killmore, C.R.; Yu, D.; Li, H. Edge Microstructure and Strength Gradient in Thermally Cut Ti-Alloyed Martensitic Steels. Metals 2021, 11, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthymiou, S.; Banis, A.; Bouzouni, M.; Petrov, R.H. Effect of Ultra-Fast Heat Treatment on the Subsequent Formation of Mixed Martensitic/Bainitic Microstructure with Carbides in a CrMo Medium Carbon Steel. Metals 2019, 9, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaefthymiou, S.; Bouzouni, M.; Petrov, R.H. Study of carbide dissolution and austenite formation during ultra-fast heating in medium carbon chromium molybdenum steel. Metals 2018, 8, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, H.; Sun, X.; Mao, M.; Guo, J. Effects of austenitizing conditions on the microstructure of AISI M42 high-speed steel. Metals 2017, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettanini, A.M.; Ding, L.; Mithieux, J.D.; Parrens, C.; Idrissi, H.; Schryvers, D.; Delannay, L.; Pardoen, T.; Jacques, P.J. Influence of M23C6 dissolution on the kinetics of ferrite to austenite transformation in Fe-11Cr-0.06 C stainless steel. Mater. Des. 2019, 162, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, G.; Alvares, L.F.; Karsi, M.; Andres, M.R. Study of the kinetics of dissolution and preciptitation of complex carbides and their effect on martensitic transformation in corrosion-resistant steels. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 1991, 33, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchi, J.; Gaudez, S.; Geandier, G.; Teixeira, J.; Denis, S.; Bonnet, F.; Allain, S.Y. Dislocation densities in a low-carbon steel during martensite transformation determined by in situ high energy X-Ray diffraction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 800, 140249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, J.; Sanket, K.; Srikar, S.; Nambissan, P.M.G.; Chandan, A.K.; Jena, P.S.M.; Sinha, S.; Dwarapudi, S. Lattice distortion in nanocrystalline Fe powder studied by positron annihilation and X-ray diffraction. Philos. Mag. 2025, 105, 546–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, S.Y.; Aoued, S.; Quintin-Poulon, A.; Gouné, M.; Danoix, F.; Hell, J.C.; Bouzat, M.; Soler, M.; Geandier, G. In situ investigation of the iron carbide precipitation process in a Fe-C-Mn-Si Q&P steel. Materials 2018, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanović, Ž.; Gligorijević, B.; Prvulović, S.; But, A.; Svoboda, P.; Piteľ, J.; Vencl, A. Decarburization and Its Effects on the Properties of Plasma-Nitrided AISI 4140 Steel: A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprilia, A.; Maharjan, N.; Zhou, W. Decarburization in laser surface hardening of AISI 420 martensitic stainless steel. Materials 2023, 16, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).