Abstract

Photoluminescent liquid crystals with photoluminescence (PL) and liquid-crystalline (LC) properties have attracted attention as PL-switching materials owing to their thermally induced phase transitions, such as crystal → smectic A/nematic → isotropic phase transitions. Our group previously developed tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers linked by flexible alkylene-1,n-dioxy spacers, demonstrating that the position of the tetrafluorinated aromatic ring critically influences the LC behavior. However, these compounds exhibited very weak fluorescence owing to an insufficient D–π–A character of the π-conjugated mesogens, which facilitated internal conversion from emissive ππ* to non-emissive πσ* states. We designed and synthesized derivatives in which the mesogen–spacer linkage was modified from ether to ester, thereby enhancing the D–π–A character. Thermal and structural analyses revealed spacer-length parity effects: even-numbered spacers induced nematic phases, whereas odd-numbered spacers stabilized smectic A phases. Photophysical studies revealed multi-state PL across solution, crystal, and LC phases. Strong blue PL (ΦPL = 0.39–0.48) was observed in solution, while crystals exhibited aggregation-induced emission enhancement (ΦPL = 0.48–0.77) with spectral diversity. In LC states, ΦPL values up to 0.36 were maintained, showing reversible intensity and spectral shifts with phase transitions. These findings establish design principles that correlate spacer parity, phase behavior, and PL properties, enabling potential applications in PL thermosensors and responsive optoelectronic devices.

1. Introduction

Organic solid-state luminescent materials are indispensable functional components in modern optoelectronic devices, particularly organic light-emitting diodes and organic electroluminescent displays [1,2,3]. In general, luminescent molecules with extended π-conjugated systems exhibit strong emission in dilute solutions; however, their luminescence in the solid state is often quenched owing to aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ) [4,5,6] originating from π-π stacking and subsequent energy transfer. In contrast, the phenomenon of aggregation-induced emission (AIE) [7,8,9,10], first reported by Tang et al. in 2001 [11], provides a molecular design strategy to circumvent ACQ. This discovery has since then led to significant progress in solid-state luminescent materials. Moreover, compounds presenting aggregation-induced emission enhancement (AIEE), which fluoresce in solution state but exhibit much stronger luminescence in the solid state, have been identified [12,13], broadening the scope of dual-state emissive materials capable of functioning in both solution and solid states.

Our research group has explored photoluminescent liquid crystals by employing tolane, a compact linear π-conjugated unit, as a luminescent mesogen and introducing flexible chains to confer both emissive and liquid-crystalline (LC) properties. Although tolane has long been used as a mesogenic unit in LC compounds [14,15,16], it was traditionally considered a poor luminophore because of the rapid internal conversion of its photoexcited ππ* state to a non-emissive πσ* state [17,18,19]. However, in the context of tolane-based dimers, restricted intramolecular rotation can effectively suppress this non-radiative pathway, thereby leading to AIEE. Recent studies have demonstrated that tolane scaffolds can become highly emissive when molecular motions are constrained, as exemplified by AIE-active tolane systems [20] and crystallization-induced emission enhancement active derivatives [21]. In addition, it has been reported that enforcing a twisted conformation between the two aromatic rings of tolane produces phosphorescence at low temperatures, highlighting an unusual emissive behavior [22,23].

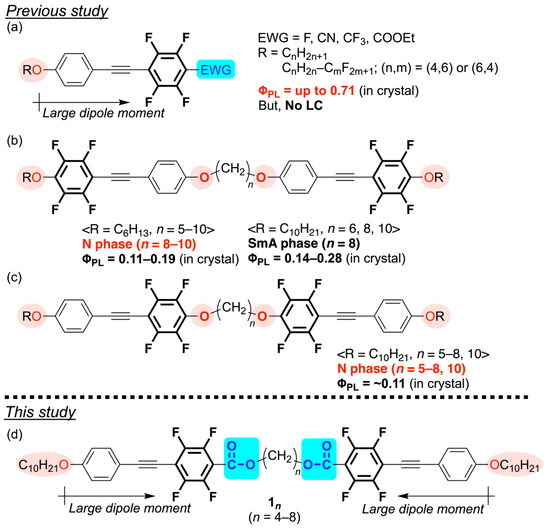

Previously, we reported photoluminescent tetrafluorinated tolane derivatives with four fluorine atoms positioned along the short molecular axis of the aromatic ring. These compounds displayed strong solid-state photoluminescence (PL) and enhanced crystalline stability via intermolecular C–H···F interactions (Figure 1a) [24,25,26].

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the research. (a) D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane derivatives [24,25,26], (b,c) tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers connected by alkylene-1,n-dioxy spacers examined in the previous study [27,28], and (d) the D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers designed in this study.

However, the strong aggregation induced by these interactions suppressed LC phase formation, even when the flexible chains were elongated [26], hindering the simultaneous realization of PL and LC behaviors. To address this, we designed mesogenic dimers, in which two tetrafluorinated tolane units were linked by an alkylene-1,n-dioxy spacer [27,28]. This approach reduced the crystallinity of the material and enabled the coexistence of PL and LC properties (Figure 1b,c). Nonetheless, the electron density distribution within the π-conjugated framework remained insufficient, resulting in weak PL in both solution and solid states.

In this study, we sought to enhance the PL performance of tolane-based mesogens by replacing the electron-donating ether linkage with an electron-withdrawing ester linkage, thereby increasing the dipole moment of the donor–π–acceptor (D–π–A) mesogenic unit [29]. This molecular design was expected to improve the PL efficiency of the mesogen in solution, solid, and LC states. Specifically, we designed novel D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane-based mesogenic dimers incorporating decyloxy substituents as electron-donating groups (EDGs) and ester linkages as electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs), connected by flexible alkylene spacers (Figure 1d). Here, we present a systematic evaluation of the LC and PL properties of these mesogenic dimer compounds and discuss how their molecular structures influence these characteristics. In addition, we report PL measurements conducted in the LC state, thereby demonstrating that these compounds serve as effective multi-state fluorescent materials, with distinct emission characteristics observed in solution, crystalline, and LC phases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

Melting temperatures (Tm) were measured through polarizing optical microscopy (POM; BX-53, Olympas, Tokyo, Japan) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; DSC-60 Plus, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on an AVANCE III 400 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) in CDCl3 (1H: 400 MHz; 13C: 100 MHz; and 19F: 376 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to residual solvent peaks for 1H and 13C or relative to C6F6 (δF = −163 ppm) for 19F. Infrared (IR) spectra were obtained with an FT/IR-4100 type A spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) using the KBr method. High-resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS) was conducted using a JMS-700MS spectrometer (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) using the fast-atom bombardment method.

All reactions were performed under an argon atmosphere in dried glassware with magnetic stir bars. Column chromatography was conducted using silica gel (Wakogel® 60N, 38–100 μm), and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel TLC plates (60F254, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

The target compounds 1n (n = 4–8) were synthesized from commercially available ethyl 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-iodobenzoate via a Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction, hydrolysis under basic conditions, and esterification with alkane-1,n-diol (Scheme 1). The 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra of compounds 1n are provided in the Supplementary Material (Figures S3–S18).

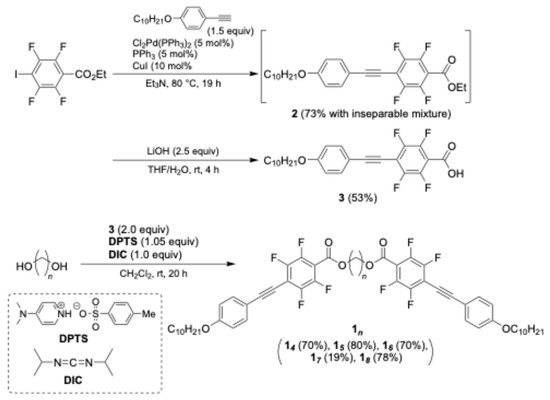

Scheme 1.

Synthetic schemes of D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers 1n.

2.2. Synthesis of 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-4-[2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl]benzoic Acid (3)

A two-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with a Teflon®-coated magnetic stirring bar was charged with 4-(decyloxyphenyl)acetylene (7.75 g, 30 mmol), Cl2Pd(PPh3)2 (0.71 g, 1.0 mmol), ethyl 2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-iodobenzoate (6.96 g, 20 mmol), and triphenylphosphine (0.55 g, 2.0 mmol) in triethylamine (100 mL). Copper(I) iodide (0.39 g, 2.0 mmol) was then added to the suspension. The reaction mixture was heated at 80 °C under stirring for 19 h. After being cooled to room temperature, the resulting precipitate was removed by atmospheric filtration under air, and the filtrate was poured into an aqueous NH4Cl solution (100 mL). The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (75 mL, three times), and the combined organic layer was washed once with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was purified by silica-gel column chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 10:1) to obtain compound 2 (14.5 mmol, 73% yield, determined by 19F NMR) along with an inseparable byproduct. The obtained compound 2, as a mixture with the inseparable byproduct, was directly subjected to the subsequent hydrolysis without further purification.

A two-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with a Teflon®-coated magnetic stirring bar was charged with compound 2 (14.5 mmol) and LiOH·H2O (1.52 g, 36.2 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF; 72 mL) and H2O (30 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h and then acidified with 10% aqueous HCl until the pH was below 1. The crude product was extracted with Et2O (50 mL, three times) and the combined organic layer was washed once with brine. The organic layer was subsequently dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was recrystallized from CH2Cl2 to afford compound 3 (4.74 g, 10.5 mmol) in 53% overall yield (two steps).

2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-4-[2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl]benzoic Acid (3)

Yield: 53% in two steps (pale yellow solid); M.P.: 138 °C determined by POM; 1H NMR (Acetone-d6): δ 0.87 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 1.25–1.41 (m, 12H), 1.48 (quin, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.79 (quin, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.07 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 23.1, 26.4, 29.8 (for two carbons), 30.0, 30.1, 32.4, 68.7, 73.1 (t, J = 4.4 Hz), 104.8 (t, J = 2.9 Hz), 107.9 (t, J = 2.2 Hz), 113.2, 113.4, 113.6, 115.7, 134.3, 143.7–146.7 (dm, J = 253.7 Hz), 145.7–148.6 (dm, J = 250.8 Hz), 160.0 (t, J = 3.0 Hz), 161.6; 19F NMR (Acetone-d6, C6F6): δ −136.90 to −137.05 (m, 2F), −140.21 to −140.37 (m, 2F); IR (KBr): ν 3744, 2953, 2926, 2852, 2213, 1684, 1476, 1419, 1254, 1169, 994, 838 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C25H26F4O3: 450.1818; Found: 450.1815.

2.3. Typical Synthetic Procedure for Target Compounds 14

Compound 3 (0.45 g, 1.0 mmol) and butane-1,4-diol (0.045 g, 0.5 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (2.0 mL) in a two-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with a Teflon®-coated magnetic stirring bar. To this solution, 4-(dimethylamino)pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (DPTS; 0.31 g, 1.05 mmol) and N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC; 0.13 g, 1.0 mmol) were added at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 20 h. It was then poured into saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (30 mL). The crude product was extracted with CHCl3 (15 mL, three times), and the combined organic layer was washed once with brine. The organic layer was subsequently dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (hexane/CH2Cl2 = 3:1), followed by recrystallization from hexane to recover the target compound 14 in 70% isolated yield (0.33 g, 0.35 mmol) as a white solid.

2.3.1. 1,4-Bis[2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-{2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl}benzoyloxy]butane 14

Yield: 70% (White solid); M.P.: 111 °C (determined by DSC); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.21–1.54 (m, 28H), 1.79 (quin, J = 6.8 Hz, 8H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 4.40 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 25.4, 26.0, 28.3, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 29.6, 31.9, 66.5, 68.2, 73.0 (t, J = 3.7 Hz), 104.7 (t, J = 2.9 Hz), 108.1 (tt, J = 2.9 Hz), 111.9 (t, J = 16.2 Hz), 113.0, 114.8, 133.8, 143.1–146.1 (dm, J = 256.8 Hz), 145.1–148.0 (dm, J = 253.0 Hz), 159.6, 160.6; 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −137.32 to −137.48 (m, 4F), −141.22 to −141.39 (m, 4F); IR (KBr): ν 2953, 2921, 2850, 2213, 1730, 1602, 1515, 1474, 1329, 1295, 1167, 994 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C54H58F8O6: 954.4106; Found: 954.4109.

2.3.2. 1,5-Bis[2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-{2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl}benzoyloxy]pentane 15

Yield: 80% (White solid); M.P.: 77 °C (determined by DSC); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.21–1.40 (m, 24H), 1.45 (quin, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.58–1.66 (m, 2H), 1.74–1.88 (m, 8H), 3.97 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 4H), 4.42 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.3, 22.7, 26.0, 28.0, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 29.6 (for two carbons), 31.9, 66.3, 68.2, 73.0 (t, J = 4.4 Hz), 104.7 (t, J = 3.6 Hz), 108.2 (tt, J = 17.6, 2.9 Hz), 111.7 (t, J = 16.1 Hz), 113.0, 114.7, 133.7, 143.1–146.2 (dm, J = 255.2 Hz), 145.0–148.0 (dm, J = 253.0 Hz), 159.6, 160.6; 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −137.43 to −137.60 (m, 4F), −141.36 to −141.52 (m, 4F); IR (KBr): ν 2921, 2851, 2218, 1728, 1605, 1475, 1331, 1261, 1172, 990, 830 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C55H60F8O6: 968.4262; Found: 968.4267.

2.3.3. 1,6-Bis[2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-{2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl}benzoyloxy]hexane 16

Yield: 70% (White solid); M.P.: 98 °C (determined by DSC); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.21–1.40 (m, 26H), 1.4–1.55 (m, 6H), 1.79 (quin, J = 6.8 Hz, 8H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 4.40 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 25.4, 26.0, 28.3, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5 (for two carbons), 31.9, 66.5, 68.2, 73.0 (t, J = 3.7 Hz), 104.6 (t, J = 2.9 Hz), 108.1 (tt, J = 18.3, 2.9 Hz), 111.9 (t, J = 16.2 Hz), 113.0, 114.7, 133.7, 143.1–146.0 (dm, J = 255.2 Hz), 145.1–148.0 (dm, J = 251.6 Hz), 159.6, 160.6; 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −137.43 to −137.57 (m, 4F), −141.38 to −141.52 (m, 4F); IR (KBr): ν 2952, 2925, 2853, 2212, 1733, 1603, 1478, 1337, 1254, 1171, 991, 838 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C56H62F8O6: 982.4419; Found: 982.4416.

2.3.4. 1,7-Bis[2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-{2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl}benzoyloxy]heptane 17

Yield: 19% (White solid); M.P.: 82 °C (determined by DSC); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 6H), 1.22–1.40 (m, 26H), 1.40–1.52 (m, 8H), 1.72–1.84 (m, 8H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 4.40 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (CDCl3); δ 14.1, 22.7, 25.6, 26.0, 28.3, 28.6, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5 (for two carbons), 31.9, 66.7, 68.2, 73.0 (t, J = 3.6 Hz), 104.6 (t, J = 2.9 Hz), 108.1 (tt, J = 16.2, 3.7 Hz), 111.9 (t, J = 16.1 Hz), 113.0, 114.4, 133.8, 143.0–146.5 (m), 145.0–148.0 (m), 159.6, 160.6; 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −137.45 to −137.60 (m, 4F), −141.38 to −141.53 (m, 4F); IR (KBr): ν 2922, 2853, 2215, 1721, 1604, 1479, 1332, 1269, 1173, 995, 832 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C57H64F8O6: 996.4575; Found: 996.4570.

2.3.5. 1,8-Bis[2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-4-{2-(4-decyloxyphenyl)ethyn-1-yl}benzoyloxy]octane 18

Yield: 78% (White solid); M.P.: 98 °C (determined by DSC); 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.88 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H), 1.22–1.50 (m, 36H), 1.72–1.85 (m, 8H), 3.98 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 4.39 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 4H), 6.89 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 14.1, 22.7, 25.7, 26.0, 28.4, 29.0, 29.1, 29.3, 29.4, 29.5 (for two carbons), 31.9, 66.8, 68.2, 73.0 (t, J = 4.4 Hz), 104.6 (t, J = 3.6 Hz), 108.1 (tt, J = 16.8, 3.0 Hz), 111.9 (t, J = 16.1 Hz), 113.0, 114.7, 133.7, 143.1–146.0 (dm, J = 256.0 Hz), 145.1–147.9 (dm, J = 253.0 Hz), 159.6, 160.6; 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −137.46 to −137.62 (m, 4F), −141.41 to −141.56 (m, 4F); IR (KBr): ν 2932, 2853, 2223, 1734, 1606, 1476, 1469, 1250, 1172, 990, 843 cm−1; HRMS: (FAB+) m/z [M]+ Calcd. for C58H66F8O6: 1010.4732; Found: 1010.4725.

2.4. Density Functional Theory Calculation

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 16 software (Rev. B.01; Gaussian, Wallingford, CT, USA) [30]. Geometrical optimizations were performed at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level of theory [31] using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) implicit solvation model [32] to simulate CH2Cl2. Vertical electronic transitions were evaluated through time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) at the same level of theory [33].

2.5. Phase-Transition Behavior

The phase-transition behaviors of the specimens were examined by POM using a BX-53 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a heating–cooling stage (10.002 L, Linkam Scientific Instruments, Redhill, UK). The phase sequences and transition enthalpies were determined by DSC (Shimadzu DSC-60 Plus) under a N2 atmosphere at heating and cooling rates were 5.0 °C min−1. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were acquired using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku MiniFlex600, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an X-ray tube (Cu Kα, λ = 1.54 Å) and semiconductor detector (D/teX Ultra2). The sample powder was mounted on a silicon non-reflecting plate set on a benchtop heating stage (Anton Paar, BTS-500, Graz, Austria). The temperature, heating/cooling rate, and time of X-ray exposure were precisely controlled.

2.6. Photophysical Behavior

UV–visible absorption spectra were recorded using a V-750 absorption spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). PL spectra in the solution and crystalline (Cr) states were acquired using an RF-6000 spectrofluorophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The absolute quantum yields of the materials in solution and Cr phases were measured using a Quantaurus-QY C11347-01 absolute PL quantum yield spectrometer (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The PL lifetime (τPL) was measured using a Quantaurus-Tau C11367-34 fluorescence lifetime spectrometer (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermophysical Properties

The target compounds were synthesized according to Scheme 1 and purified by silica gel column chromatography followed by recrystallization. A decyloxy group and an ester moiety were introduced as the EDG and EWG, respectively, into D–π–A fluorinated tolanes. The resulting compounds constitute a homologous series of mesogenic dimers, ranging from dimer 14 with a butylene spacer to dimer 18 with an octylene spacer. The phase-transition behaviors of these compounds were first investigated using DSC. Each compound was subjected to three consecutive heating–cooling cycles to evaluate its thermal behavior. Furthermore, the mesophases formed upon phase transitions were identified by POM and PXRD. Figure 2 presents the phase-transition sequences observed during the second heating–cooling cycle and the POM texture images; the detailed thermograms are presented in Figures S19–S23 in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

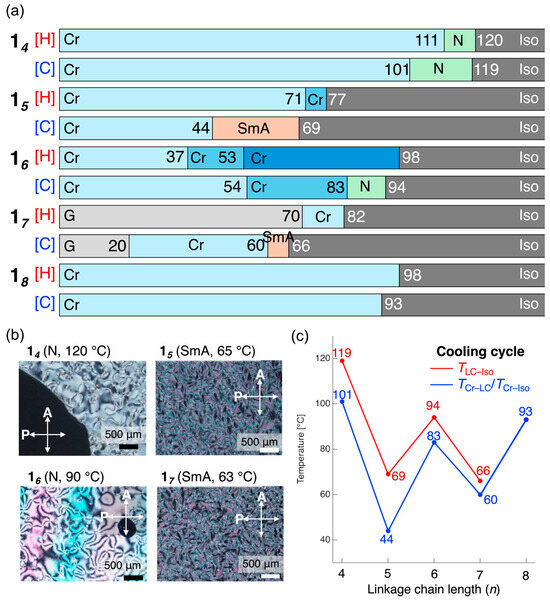

Figure 2.

(a) Phase sequence and transition temperatures of compounds 14–18 during the second heating and cooling cycle. The phase-transition temperatures were determined by differential scanning calorimetry (10 °C min−1 under N2 atmosphere). (b) Optical texture images of 14–18 in the mesophase obtained by polarized optical microscopy. (c) Dependence of the phase-transition temperature on the number of carbon atoms in the liking spacer of 1n during the cooling cycle.

DSC and POM observations revealed that compounds 14–17 form mesophases upon both heating and cooling. By contrast, in compound 18, which contains an octylene spacer, only a crystal–isotropic (Cr–Iso) transition was observed under the present conditions as the sample could not be sufficiently supercooled to detect any potential monotropic mesophase (Figures S19–S23). POM observations of the mesophases revealed that compounds with even-numbered spacers (14 and 16) exhibit Schlieren textures, whereas those with odd-numbered spacers (15 and 17) display fan-shaped textures consisting of small domains (Figure 2b). PXRD and small-angle X-ray scattering measurements were performed on the mesophases obtained upon cooling. For even-spacer compounds 14 and 16, only a diffuse halo peak was observed at 2θ ≈ 20°, with no sharp diffractions detected across the entire region (Figure S24b,e). In contrast, odd-spacer compounds 15 and 17 exhibited distinct diffraction peaks in the low-angle region, indicating the presence of layered order along the molecular long axis (Figure 3).

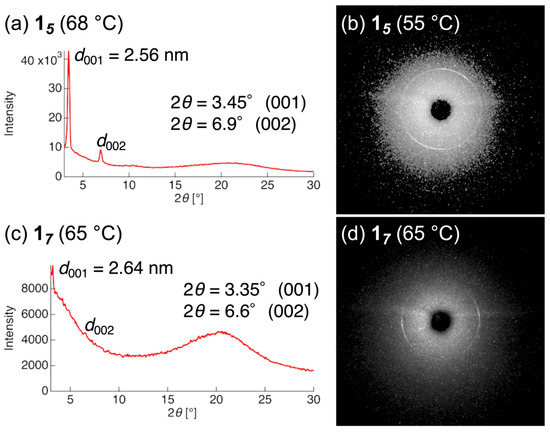

Figure 3.

One-dimensional PXRD patterns of compounds (a) 15 and (c) 17, and two-dimensional small-angle X-ray scattering profiles of (b) 15 and (d) 17, as measured for the mesophase formed during the cooling process.

Based on the POM and PXRD results, the mesophases formed by even-spacer compounds 14 and 16 were assigned to nematic (N) phases, which possess orientational order only. Conversely, the mesophases formed by odd-spacer compounds 15 and 17 were identified as smectic (Sm) phases characterized by both orientational and positional order. Furthermore, the PXRD patterns of compounds 15 and 17 displayed sharp (001) reflections at 2θ = 3.45° and 3.35°, respectively. Using Bragg’s equation, the corresponding layer spacings (d-spacing) of compounds 15 and 17 were calculated to be 2.56 and 2.64 nm, respectively.

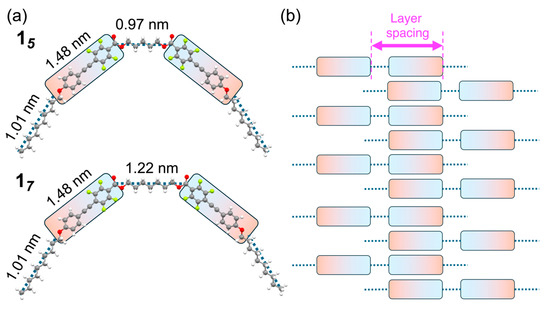

Further, structural optimizations were performed on compounds 15 and 17, which formed Sm phases with layered aggregated structures, and the resulting optimized geometries are shown in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

(a) Optimized geometries of compounds 15 and 17, and (b) the proposed layered structures of these compounds in the SmA phase.

The optimized geometries exhibited a bent conformation, in which the π-conjugated mesogens were deflected in the same direction as the linking spacer. The molecular lengths of each structural unit were approximately 1.48 nm for the D–π–A fluorinated tolane unit, 1.01 nm for the terminal decyloxy chain, and 0.97 and 1.22 nm for the linking spacers in compounds 15 and 17, respectively. In the SmA phase, intermolecular interactions between the D–π–A-type π-conjugated mesogens, which possess large dipole moments, are predominant (Figure 4b). Under these conditions, the sum of the molecular lengths of the π-conjugated mesogen and the linking spacer corresponds to the layer spacing of the Sm structure, which in turn coincides with the d-spacing associated with the (001) reflection observed in the PXRD pattern. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the mesophases formed by compounds 15 and 17 can be assigned to the SmA phase because the observed layer spacing corresponds to the molecular length along the layer normal.

Furthermore, Figure 2c shows the relationship between the number of carbon atoms in the linking spacer chain and the phase-transition temperature during the cooling process for the 1n mesogens. Here, the Iso-to-LC transition temperature is defined as TLC–Iso and the LC-to-Cr phase-transition temperature is defined as TCr–LC. Remarkably, a distinct odd-even effect was observed, with both transition temperatures being higher for mesogens with even-numbered spacers than for the mesogens with odd-numbered spacers. The mesophases formed by the molecules with odd-numbered spacers were identified as SmA phases, which have a higher degree of order than the N phases formed by the molecules with even-numbered spacers. Consequently, the direct formation of the ordered SmA phase from the Iso phase upon cooling was hindered, leading to a decrease in the TLC–Iso value. In addition, the optimized geometries of the mesogens with odd-numbered spacers exhibited bent conformations. Assuming that this bent structure reflects the molecular arrangement in the Cr phase, the transition from the SmA phase to a bent molecular conformation is also unfavorable, resulting in the phase transition occurring at lower temperatures.

These phase-transition behaviors indicate that the D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers designed and synthesized in this study, with spacers ranging from butylene to heptylene, form LC phases. Notably, the results clearly reveal that the type of mesophase, that is, N or SmA, can be controlled by the parity of the spacer length. An examination of the relationship between the molecular lengths calculated by DFT and the exhibited mesophases revealed that the molecular lengths of the compounds with even-numbered spacers showing the N phase were 56.61 Å for 14, 57.69 Å for 16, and 59.16 Å for 18. By contrast, the molecular lengths of the derivatives with odd-numbered spacers exhibiting the SmA phase were 25.49 Å for both 15 and 17 (Figure S32). These results suggest that molecules with more linear structures tend to form the N phase, whereas those with bent structures are inclined to form the SmA phase.

3.2. Photophysical Properties

3.2.1. UV-Visible (UV-Vis) and PL Behavior in CH2Cl2 Solutions

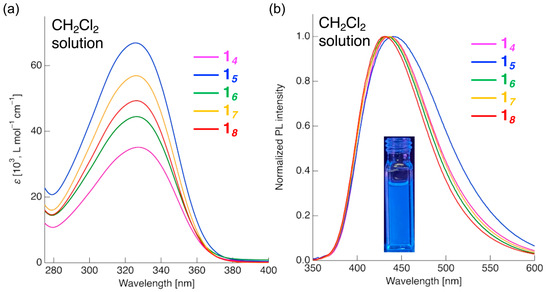

Having examined the phase-transition behavior, the photophysical properties of D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers with linking spacers of varying chain lengths, viz., 14–18, were investigated. To gain fundamental insight into their electronic characteristics, the UV–vis absorption and PL properties were examined in a CH2Cl2 solution. The UV–vis. and PL spectra of compounds 14–18 are shown in Figure 5 and Figure S25, and the detailed photophysical data are provided in Table 1.

Figure 5.

(a) UV-visible absorption and (b) PL spectra of compounds 14–18 in CH2Cl2 solutions. Excitation wavelength: λex = 327 nm for 14 and 326 nm for 15–18; slit widths (ex/em): 5.0 nm/5.0 nm; scan rate: 600 nm min−1 for all samples; concentrations: 1.0 × 10−5 mol L−1 for absorption measurements and 1.0 × 10−6 mol L−1 for PL measurements.

Table 1.

Photophysical data of compounds 14–18 in CH2Cl2 solutions.

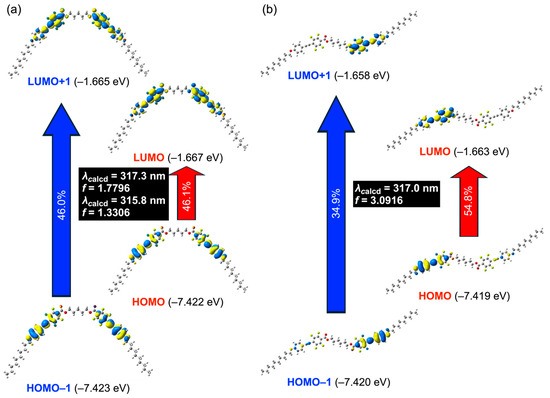

The CH2Cl2 solutions of compounds 14–18 were transparent in the 400–800 nm region. Below 400 nm, they exhibited absorption maxima (λabs) at 326–327 nm, as shown in Figure 6a. To elucidate the nature of these absorptions, time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculations were performed using the optimized geometries obtained from DFT and including the CPCM solvation model for CH2Cl2 (Figure 6, Table 2).

Figure 6.

Vertical electronic transitions of (a) compound 15 with a bent geometry and (b) compound 16 with an N-shaped geometry, obtained by TD-DFT calculations.

Table 2.

Theoretical data for vertical electronic transitions of compounds 14–18 1.

The results revealed that the number of electronically allowed excited states depends on the parity of the spacer length. For compounds with even-numbered spacers, whose optimized structures adopt an N-type geometry, a single excited state transition dominated. In contrast, compounds with odd-numbered spacers, which adopt bent geometries, allowed transitions to two excited states. All these excited states correspond to transitions from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) or HOMO–1 to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) or LUMO+1. The analysis of molecular orbital distributions revealed that for compounds with odd-numbered spacers, the bent geometry endowed higher symmetry, resulting in orbital delocalization from HOMO–1 to LUMO+1 over both groups of π-conjugated mesogens. In contrast, in compounds with even-numbered spacers that adopt N-type geometries, the same set of orbitals was localized on one of the two π-conjugated mesogens. This difference in orbital delocalization accounts for the disparity in the number of accessible excited states.

Furthermore, molecular orbital diagrams of HOMO/HOMO–1 and LUMO/LUMO+1 revealed substantial electron density on the electron-rich alkoxy-substituted aromatic rings, whereas the electron-deficient ester-substituted aromatic rings exhibited smaller electron distributions. These results confirm the presence of a typical D–π–A electronic structure. Indeed, our previous studies demonstrated π-π* transitions originating from intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) states in fluorinated tolanes bearing ester functionality as electron-withdrawing substituents [24,26], and a similar ICT-based π-π* transition is inferred here for the present mesogenic dimer systems.

The theoretically calculated absorption maxima (λcalcd) of the allowed transitions with high oscillator strengths (f) were 316–318 nm, slightly blue-shifted relative to the experimental λabs values of 326–327 nm. This small discrepancy can be attributed to environmental effects. Therefore, the absorption processes of tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers 14–18 can be assigned to ICT-based π-π* transitions involving HOMO/HOMO–1 → LUMO/LUMO+1, as supported by theoretical calculations.

Using the observed λabs values as excitation wavelengths, the PL properties of compounds 14–18 in CH2Cl2 solutions were further investigated (Figure 5b and Figure S25). Independent of the spacer length, all compounds exhibited a single blue PL band with emission maxima (λPL) at 430–441 nm. The PL quantum yields (ΦPL = emitted photons/absorbed photons) were moderate, ranging from 0.39 to 0.48. In contrast, previously reported ether-linked analogs emitted at ~360 nm with ΦPL ≈ 0.035, exhibiting only very weak near-UV PL [27,28]. Thus, the substitution of the ether linkage with an ester linkage enhances the D–π–A character, leading to comparatively stronger PL in the visible region. Fluorescence decay measurements revealed average lifetimes (τPL) of 1.97–5.26 ns for mesogenic dimers 14–18 (Table 2, Figure S26). The nano-second lifetimes indicate that the radiative decay arises from fluorescence. In most cases, the decay profiles could be fitted well with biexponential functions, suggesting the involvement of at least two emissive excited states. Although the detailed excited-state structures remain to be determined, the introduction of the EDG and EWG into the π-conjugated core induces a strong D–π–A character, implying that in addition to monomeric CT-state emission, partial aggregation-derived emission (either intramolecular or intermolecular) may also contribute to PL. From ΦPL and τave, the radiative (kr) and non-radiative (knr) decay rate constants were calculated to be 0.91–1.98 × 108 and 0.99–3.10 × 108 s−1, respectively. The knr/kr ratios ranged from 1.08 to 1.56, indicating that non-radiative decay can be up to 1.56 times faster than radiative decay. In general, diphenylacetylenes are known to undergo ultrafast internal conversion from a linear fluorescent ππ* excited state to a non-fluorescent trans-bent πσ* excited state [17,18,19]. Although the incorporation of the EDG and EWG at the longitudinal molecular termini to form a D–π–A structure has been reported to suppress this internal conversion [29], in the present D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimeric systems, rapid internal conversion remains predominant, resulting in a greater knr than the kr.

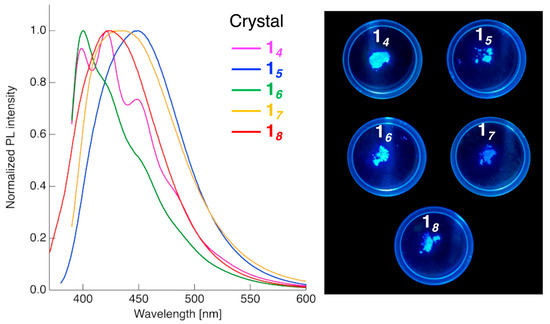

3.2.2. PL Behavior of the Mesogenic Dimers in the Cr Phase

Next, the PL behaviors of the D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers, which exhibited relatively strong blue fluorescence in CH2Cl2 solutions, were investigated in the Cr state. For PL measurements, the Cr samples obtained by recrystallization after silica gel column chromatography were used. Figure 7 and Figure S27 present the PL spectra of the Cr samples, along with the photographs of their emission under UV irradiation. The corresponding photophysical data are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 7.

PL spectra in the crystalline state for compounds 14 (λex = 370 nm), 15 (λex = 349 nm), 16 (λex = 364 nm), 17 (λex = 370 nm), and 18 (λex = 347 nm), and photographs showing their PL behavior under UV irradiation (λ = 365 nm). Slit widths (ex/em): 5.0 nm/5.0 nm; scan rate: 600 nm min−1 for all samples.

Table 3.

Photophysical data of compounds 14–18 in the crystalline state.

In contrast to the PL behaviors observed in CH2Cl2 solutions, the spectral profiles and λPL values of the Cr state varied significantly depending on the spacer length, although no clear correlation between the spacer length and PL behavior could be established. Specifically, compound 14, with the shortest spacer, exhibited a PL spectrum with maxima at 399, 421, and 449 nm. Compound 16, which also has an even-numbered spacer, showed a main λPL at ~400 nm, accompanied by shoulder peaks at ~420 and 449 nm. Compound 18 displayed a broad single PL band centered at 423 nm. In contrast, compound 15 with an odd-numbered spacer exhibited a single PL band at λPL = 449 nm, while compound 17 showed a blue-shift of the λPL by approximately 18 nm relative to that of compound 15. These variations are likely attributable to the differences in the molecular packing of the different mesogenic dimers in the Cr state; however, the crystal structures of these compounds remain undetermined. A notable feature of the Cr-state PL behavior is that all compounds exhibited enhanced ΦPL values relative to those measured in CH2Cl2 solutions, resulting in a strong blue emission. In general, compounds with extended π-conjugation tend to undergo π-π stacking in the Cr state, which facilitates non-radiative deactivation, leading to fluorescence quenching, in a phenomenon known as ACQ. In contrast, compounds 14–18 did not exhibit ACQ; rather, they showed AIEE.

Fluorescence decay measurements revealed τPL values of 1.42–10.73 ns, confirming that the radiative decay processes in the Cr state originate from fluorescence (Figure S28). From the ΦPL and τPL values, the kr and knr were calculated to be 0.63–4.51 × 108 and 0.30–3.06 × 108 s−1, respectively. Notably, the knr/kr ratios ranged from 0.30 to 1.08, indicating that all compounds, except compound 17 with a relatively low ΦPL, show significantly accelerated kr values. Although the crystal structures remain unresolved, it is reasonable to conclude that stronger intermolecular interactions and restricted molecular motions in the Cr state suppress non-radiative deactivation pathways, thereby enhancing the PL efficiency.

3.2.3. PL Behavior in the Mesophase

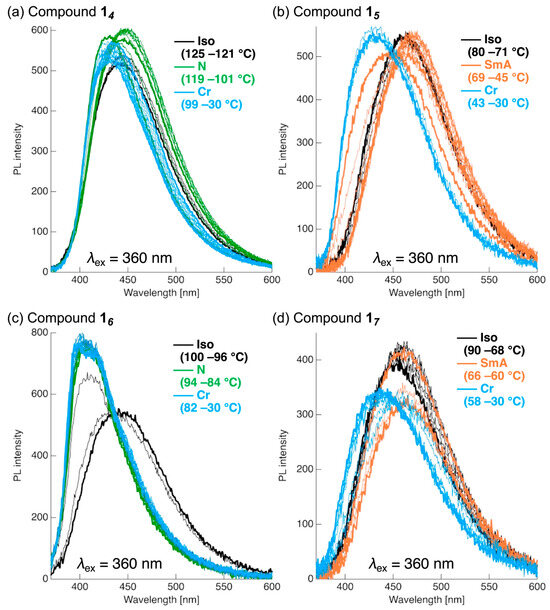

Finally, the PL behaviors of compounds 14–17, which exhibited an LC phase upon cooling, were investigated in the mesophase during the cooling process; the samples were first heated to the Iso phase and subsequently cooled gradually, during which the PL spectra were recorded at each temperature, at 2 °C intervals near the phase transition and at 5 °C intervals otherwise (Figure 8 and Figure S29).

Figure 8.

PL spectral changes in 14–17 during the cooling process from the Iso to the Cr phase for (a) compound 14, (b) compound 15, (c) compound 16, and (d) compound 17. Excitation wavelength: λex = 360 nm for 14–17. Black: Iso phase; green: N phase; orange: SmA phase; and pale blue: Cr phase.

For compound 14, a single PL band was observed at λPL ≈ 430 nm (ΦPL = 0.288) upon transition to the Iso phase. During cooling, the ΦPL gradually increased while the λPL underwent a slight redshift. In the N phase, the λPL further shifted to 450 nm, and the ΦPL reached 0.35. Upon transition from the N to Cr phase, the λPL returned to ~430 nm, and the ΦPL decreased to 0.281. Thereafter, the ΦPL recovered, whereas the λPL remained nearly constant, resulting in λPL = 433 nm and ΦPL = 0.310 at 30 °C. Compound 16, which also forms an N phase, displayed a somewhat different behavior. In the Iso phase, λPL was ~445 nm with ΦPL = 0.33. Upon transition to the N phase, the λPL blue-shifted to ~406 nm, and the ΦPL slightly decreased to 0.31. Further cooling induced a gradual blue shift of the λPL to ~400 nm, while the ΦPL increased. At 30 °C, the λPL reached 395 nm, and the ΦPL was 0.38. In contrast, 15 and 17, which form SmA phases, exhibited different trends. For compound 15, a red-shift from λPL = 449 nm (Cr phase) to λPL = 457 nm (Iso phase) was observed, accompanied by a decrease in the ΦPL to 0.34. In the SmA phase, the λPL further red-shifted to 466 nm, but the ΦPL remained nearly constant (0.32). Upon transitioning back to the Cr phase, the λPL blue-shifted markedly to 426 nm, whereas the ΦPL remained at 0.34. Similarly, compound 17 exhibited a red-shift of the λPL and a decrease in the ΦPL upon transitioning from the Cr phase (λPL = 431 nm) to the Iso one (λPL = 453 nm, ΦPL = 0.24). In the SmA phase, the λPL further red-shifted to 456 nm, whereas the ΦPL remained constant at 0.28. Ultimately, the λPL blue-shifted again in the Cr phase, yielding λPL = 435 nm and ΦPL = 0.233 at 30 °C.

Overall, for all compounds, the λPL values in the cooled Cr phases were blue-shifted relative to those before heating. This behavior is attributed to differences in the crystallization processes, which may lead to distinct crystal polymorphs. Moreover, the red-shifts observed in the SmA phases were also evident in the absorption spectra (Figure S31), suggesting the formation of J-aggregate-like assemblies of the π-conjugated moieties.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we developed multi-state PL materials operating in dilute solution, solid, and LC states. Specifically, we produced novel mesogenic dimers by linking D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane units, which consisted of a decyloxy group as an electron donor and an ester functionality as an electron acceptor, with flexible alkylene spacers. Analyses of their phase-transition behavior revealed a strong dependence on spacer parity: even-numbered spacers produced N phases, while odd-numbered spacers yielded layered SmA phases. Photophysical studies revealed that all compounds exhibited blue PL in the solution state while showing enhanced PL in the crystalline state owing to AIEE. In the LC phases, phase transitions were accompanied by shifts in the PL wavelength and efficiency, and the PL quantum yields (ΦPL) reached 0.36. These results establish that D–π–A tetrafluorinated tolane mesogenic dimers represent an effective design strategy for multi-state PL materials, providing PL across solution, solid, and LC states. This approach offers important guidelines for developing next-generation photoluminescent LC materials through controlled molecular assembly, resulting in potential applications in optoelectronic devices, such as light-emitting displays, luminescent sensors, optical switches, and stimuli-responsive functional materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cryst15121050/s1. Figures S1–S18: NMR spectrum of compounds 3 and 14–18; Figures S19–S23: DSC thermogram and POM image of compounds 14–18; Figure S24: PXRD patterns; Figure S25: absorption and PL spectrum of compounds 14–18 in CH2Cl2 solution; Figure S26: PL decay profile of compounds 14–18 in CH2Cl2 solution; Figure S27: excitation and PL spectrum of compounds 14–18 in crystalline state; Figure S28: PL decay profile of compounds 14–18 in crystalline state; Figure S29: PL spectral changes during the cooling process from Iso to the Cr phases; Figure S30: PL spectra (left) and PLQY values (right) during Cr ⇄ LC ⇄ Iso phase transitions over 10 cycles for (a) 14, (b) 15, (c) 16, and (d) 17; Figure S31: Absorption spectra in crystalline and mesophases; Figure S32: Optimized geometries and calculated molecular length of (a) 14, (b) 15, (c) 16, (d) 17, and (e) 18; Tables S1–S5: Phase transition data of compounds 14–18; Table S6: Comparison of photophysical properties among ether-linked mesogenic dimers (C6-On, C10-On, and C10-In) and ester-linked derivatives (1n); Table S7: PLQY values of 14–18 at each temperature during the 1st cooling process; Tables S8–S17: cartesian coordinates of optimized geometry for 14–18 in S0 and S1 states.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I. and S.Y.; methodology, S.I. and S.Y.; validation, S.Y.; investigation, S.I., Y.E., M.M., M.Y., T.K. and S.Y.; resources, M.Y., T.K. and S.Y.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.I., Y.E., M.M., M.Y., T.K. and S.Y.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, S.Y.; project administration, S.Y.; funding acquisition, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the present study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted by sharing research equipment under the MEXT Project focused on promoting the public utilization of advanced research infrastructure (Program for supporting the introduction of the new sharing system; Grant No. JPMXS042180022025). Computations were performed using Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (Project: 25-IMS-C285). The authors thank Tsuneaki Sakurai (Kyoto Inst. Tech.) and Yoichi Takanishi (Kyoto Prefectural Med. Univ.) for their assistance with the VT-PXRD and small-angle X-ray scattering measurements and fruitful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACQ | Aggregation-caused quenching |

| AIE | Aggregation-induced emission |

| ICT | Intramolecular charge transfer |

| LC | Liquid-crystalline |

| PXRD | Powder X-ray diffraction |

| IR | Infrared |

| EDG | Electron-donating group |

| EWG | Electron-withdrawing group |

| POM | Polarizing optical microscopy |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| Cr | Crystalline |

| N | Nematic |

| SmA | Smectic A |

| Iso | Isotropic |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

References

- He, X.; Wei, P. Recent advances in tunable solid-state emission based on α-cyanodiarylethenes: From molecular packing regulation to functional development. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 6636–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.D.; Hall, D.; Basumatary, B.; Bryden, M.; Chen, D.; Choudhary, P.; Comerford, T.; Crovini, E.; Danos, A.; De, J.; et al. The golden age of thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials: Design and exploitation. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 13736–14110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Guo, S.; Lv, H.; Chen, F.; Wei, L.; Gong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, C. Molecular design for organic luminogens with efficient emission in solution and solid-state. Dye. Pigment. 2022, 198, 109958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xing, J.; Gong, Q.; Chen, L.C.; Liu, G.; Yao, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q. Reducing aggregation caused quenching effect through co-assembly of PAH chromophores and molecular barriers. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, C.K.; Lin, L. Theoretical study of the mechanism of aggregation-caused quenching in near-infrared thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: Hydrogen-bond effect. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 24705–24713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, S.R.; Jayakannan, M. Probing the π-stacking induced molecular aggregation in π-conjugated polymers, oligomers, and their blends of p-phenylenevinylenes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, J.; Leung, N.L.C.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission: Together we shine, united we soar! Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11718–11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.J.; Xin, Z.Y.; Su, X.; Hao, L.; Qiu, Z.; Li, K.; Luo, Y.; Cai, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Alam, P.; et al. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens realizing high-contrast bioimaging. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, G.R.; Pandey, M.; Chakravarthy, A.S.J. Review on new horizons of aggregation induced emission: From design to development. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 1541–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission: New vistas at the aggregate level. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 9888–9907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xie, Z.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Cheng, L.; Chen, H.; Qiu, C.; Kwok, H.S.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, D.; et al. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 2001, 18, 1740–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.K.; Gierschner, J.; Park, S.Y. π-Conjugated cyanostilbene derivatives: A unique self-assembly motif for molecular nanostructures with enhanced emission and transport. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.K.; Kwon, S.K.; Jung, S.D.; Park, S.Y. Enhanced emission and its switching in fluorescent organic nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14410–14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Tang, J.; Mao, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, P.; An, Z. High-Δn tolane-liquid crystal diluters with low melting point and low rotational viscosity. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 398, 124312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, R.; Khalfallah, C.B.; Soltani, T. Synthesis and study of physicochemical properties of relatively high birefringence liquid crystals: Tolane-type with symmetric alkoxy side groups. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 310, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsu, H. Development and industrialization of liquid crystalline tolanes. J. Syn. Org. Chem. Jpn. 1999, 57, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, C.; Kensy, U.; Dick, B. Does diphenylacetylene (tolan) fluoresce from its second excited singlet state? Semiempirical MO calculations and fluorescence quantum yield measurements. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 13457–13463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgierski, M.Z.; Lim, E.C. Nature of the ‘dark’ state in diphenylacetylene and related molecules: State switch from the linear ππ* state to the bent πσ* state. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 387, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, J.; Kumar, V.K.R. Photophysics of diphenylacetylene: Light from the ‘dark state’. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 10548–10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Yang, Y. Light emission properties and self-assembly of a tolane-based luminogen. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 38690–38695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Wang, Y.J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, J.Z.; Tang, B.Z. Crystallization-induced emission enhancement of a simple tolane-based mesogenic luminogen. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 21875–21881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menning, S.; Krämer, M.; Duckworth, A.; Rominger, F.; Beeby, A.; Dreuw, A.; Bunz, U.H.F. Bridged tolanes: A twisted tale. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6571–6578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhemyakin, Y.; Krämer, M.; Rominger, F.; Dreuw, A.; Bunz, U.H.F. A tethered tolane: Twisting the excited state. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 15219–15222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Yamada, S.; Konno, T. Fluorine-induced emission enhancement of tolanes via formation of tight molecular aggregates. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 6704–6708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Mitsuda, A.; Miyano, K.; Tanaka, T.; Morita, M.; Agou, T.; Kubota, T.; Konno, T. Development of novel solid-state light-emitting materials based on pentafluorinated tolane fluorophores. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 9105–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Kataoka, M.; Yoshida, K.; Nagata, M.; Agou, T.; Fukumoto, H.; Konno, T. Photophysical and thermophysical behavior of D–π–A-type fluorinated diphenylacetylenes bearing an alkoxy and an ethoxycarbonyl group at both longitudinal molecular terminals. J. Fluor. Chem. 2022, 261–262, 110032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.; Uto, E.; Sakurai, T.; Konno, T. Development of thermoresponsive near-ultraviolet photoluminescent liquid crystals using hexyloxy-terminated fluorinated tolane dimers connected with an alkylene spacer. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inui, S.; Kitaoka, H.; Eguchi, Y.; Yasui, M.; Konno, T.; Yamada, S. Design of near-UV photoluminescent liquid-crystalline dimers: Role of fluorinated aromatic ring position and flexible linker. Crystals 2025, 15, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szyszkowska, M.; Bylińska, I.; Wiczk, W. Influence of an electron-acceptor substituent type on the photophysical properties of unsymmetrically substituted diphenylacetylene. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2016, 326, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian16, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Incorporated: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, M.; Harvey, A.J.A.; Sen, A.; Dessent, C.E.H. Performance of M06, M06-2X, and M06-HF density functionals for conformationally flexible anionic clusters: M06 functionals perform better than B3LYP for a model system with dispersion and ionic hydrogen-bonding interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 12590–12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jensen, J.H. Improving the efficiency and convergence of geometry optimization with the polarizable continuum model: New energy gradients and molecular surface tessellation. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1449–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, R.B.; Buch, V.; Ratner, M.A. Time-dependent self-consistent field approximation for intramolecular energy transfer. I. Formulation and application to dissociation of van der Waals molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).