The Comparative Study of Four Hexachloroplatinate, Tetrachloroaurate, Tetrachlorocuprate, and Tetrabromocuprate Benzyltrimethylammonium Salts: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures, Non-Classical Synthon Preference, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, and Quantum Chemical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Salts 1–4

2.2. Crystallography

2.3. Computational Study

2.3.1. Quantum Chemical Studies

2.3.2. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

2.3.3. Enrichment Ratio

2.3.4. Energy Frameworks

2.3.5. CSD-Materials Module

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystallographic Study

3.2. Supramolecular Features of 1–4

3.3. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis

3.4. Energy Frameworks

3.5. Quantum Chemical Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hasan, M.; Kozhevnikov, I.V.; Siddiqui, M.R.H.; Steiner, A.; Winterton, N. Gold compounds as ionic liquids. Synthesis, structures, and thermal properties of N, N ‘-Dialkylimidazolium tetrachloroaurate salts. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38, 5637–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Inada, S. Liquid-liquid distribution of ion associates of tetrahalogenoaurate (III) with quaternary ammonium counter ions. Anal. Sci. 1995, 11, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, H.; Uota, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Fujikawa, D.; Sakai, G.; Arakawa, R.; Kijima, T. Self-Organization of Surfactant−Metal-Ion Complex Nanofibers on Graphite Surfaces and Their Application to Fibrously Concentrated Platinum Nanoparticle Formation. Langmuir 2007, 23, 11540–11545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacheva, A.; Sharutin, V.; Sharutina, O.; Shlepotina, N.; Kolesnikov, O.; Shishkova, Y.S.; Peshikova, M. Tetravalent platinum complexes: Synthesis, structure, and antimicrobial activity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2020, 90, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Xu, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, N.; Zhou, Q. The role played by amine and ethyl group in the reversible thermochromic process of [(C2H5)2NH2]2CuCl4 probing by FTIR and 2D-COS analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1161, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mande, H.M.; Ghalsasi, P.S.; Navamoney, A. Synthesis, structural and spectroscopic characterization of the thermochromic compounds A2CuCl4:[(Naphthyl ethylammonium)2CuCl4]. Polyhedron 2015, 91, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, B.F.; Andrews, G.P.; Borberly, G.; Earle, M.J.; Gilea, M.A.; Gorman, S.P.; Lowry, A.F.; McLaughlin, M.; Seddon, K.R. Enhanced antimicrobial activities of 1-alkyl-3-methyl imidazolium ionic liquids based on silver or copper containing anions. New J. Chem. 2013, 37, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, S.; Dilbaghi, N.; Bhanjana, G.; Guru, S.K.; Bhushan, S.; Jaglan, S.; Hassan, P.; Aswal, V. Hybrid surfactants decorated with copper ions: Aggregation behavior, antimicrobial activity and anti-proliferative effect. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23961–23970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, X.-M.; Zhao, H.-X.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Coexistence of magnetic-optic-electric triple switching and thermal energy storage in a multifunctional plastic crystal of trimethylchloromethyl ammonium tetrachloroferrate (III). Inorg. Chem. 2018, 58, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Saha, S.; Hamaguchi, H. A new class of magnetic fluids: Bmim [fecl/sub 4/] and nbmim [fecl/sub 4/] ionic liquids. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2006, 42, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiraju, G.R. Crystal engineering: A holistic view. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8342–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakeröy, C.B.; Champness, N.R.; Janiak, C. Recent advances in crystal engineering. CrystEngComm 2010, 12, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarska, J.; Łyczko, K.; Breza, M.; Mieczkowski, A. Recurrent Supramolecular Patterns in a Series of Salts of Heterocyclic Polyamines and Heterocyclic Dicarboxylic Acids: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-ray Structure, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, Energy Framework, and Quantum Chemical Calculations. Crystals 2024, 14, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarska, J.; Łyczko, K.; Mieczkowski, A. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Supramolecular Features of Novel 2, 4-Diaminopyrimidine Salts. Crystals 2024, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarska, J.; Łyczko, K.; Mieczkowski, A. Novel Salts of Heterocyclic Polyamines and 5-Sulfosalicylic Acid: Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Hierarchical Supramolecular Interactions. Crystals 2024, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, L.; Zhang, P.; Gao, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J. Self-assemblies of isomeric copper iodide trimers with geometry-dependent photophysical properties. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 9339–9345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, M.; Gągor, A.; Stroppa, A.; Gonçalves, J.N.; Zaręba, J.K.; Stefańska, D.; Pikul, A.; Drozd, M.; Sieradzki, A. Two-dimensional metal dicyanamide frameworks of BeTriMe [M(dca)3(H2O)] (BeTriMe = benzyltrimethylammonium; dca = dicyanamide; M = Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+): Coexistence of polar and magnetic orders and nonlinear optical threshold temperature sensing. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 11735–11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczka, M.; Ptak, M.; Trzebiatowska, M.; Kucharska, E.; Hanuza, J.; Palka, N.; Czerwinska, E. THz, Raman, IR and DFT studies of noncentrosymmetric metal dicyanamide frameworks comprising benzyltrimethylammonium cations. Spectrochim. Acta Part A-Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 251, 119416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chempath, S.; Boncella, J.M.; Pratt, L.R.; Henson, N.; Pivovar, B.S. Density functional theory study of degradation of tetraalkylammonium hydroxides. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 11977–11983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgeon, M.R.; Macomber, C.S.; Engtrakul, C.; Long, H.; Pivovar, B.S. Hydroxide based benzyltrimethylammonium degradation: Quantification of rates and degradation technique development. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, F366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karibayev, M.; Myrzakhmetov, B.; Kalybekkyzy, S.; Wang, Y.; Mentbayeva, A. Binding and degradation reaction of hydroxide ions with several quaternary ammonium head groups of anion exchange membranes investigated by the DFT method. Molecules 2022, 27, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrum, I.; Hickner, M.; Janik, M. Quaternary ammonium cation specific adsorption on platinum electrodes: A combined experimental and density functional theory study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, F114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, K.; Tao, L.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, N.; Wan, H.; Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Anti-corrosion for reversible zinc anode via a hydrophobic interface in aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2103557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J. Exploration of catalytic species for highly efficient preparation of quinazoline-2,4(1H, 3H)-diones by succinimide-based ionic liquids under atmospheric pressure: Combination of experimental and theoretical study. Fuel 2022, 319, 123628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamico, M.; Dessy, G.; Vaciago, A. The crystal structure of bis-trimethylbenzylammoniumtetrachlorocuprate (II). Theor. Chim. Acta 1967, 7, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Liu, N.; Li, Y.-J.; Wu, D.-H. Bis (benzyltrimethylammonium) tetrabromidocuprate (II). Struct. Rep. 2011, 67, m1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yu, C.-H.; Zhang, W. Structural diversity of a series of chlorocadmate (II) and chlorocuprate (II) complexes based on benzylamine and its N-methylated derivatives. J. Coord. Chem. 2014, 67, 1156–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlis, C. CrysAlis Red. Xcalibur PX Software, version 1.171.40.67a; Oxford Diffraction Ltd.: Abingdon, UK, 2008.

- Clark, R.; Reid, J. The analytical calculation of absorption in multifaceted crystals. Found. Crystallogr. 1995, 51, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71 Pt 1, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Found. Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head-Gordon, M.; Pople, J.A.; Frisch, M.J. MP2 energy evaluation by direct methods. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 153, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head-Gordon, M.; Head-Gordon, T. Analytic MP2 frequencies without fifth-order storage. Theory and application to bifurcated hydrogen bonds in the water hexamer. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1994, 220, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.; Scuseria, G.; Robb, M.; Cheeseman, J.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.; Nakatsuji, H. GAUSSIAN09, version 9.0; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2011.

- Marenich, A.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 6378–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varetto, U. Molekel, version 5.4. 0.8; Swiss National Supercomputing Centre: Manno, Switzerland, 2009.

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader Richard, F. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, T.A. AIMAll, version 17.11. 14; TK Gristmill Software: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2017.

- Biegler-Konig, F.; Schonbohm, J.; Bayles, D. Software News and Updates-AIM2000-A Program to Analyze and Visualize Atoms in Molecules; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 545–559. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, L. The AxPyMOL Molecular Graphics Plugin for Microsoft PowerPoint, version 1.8; Schroedinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Kabsch, W. A solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Found. Crystallogr. 1976, 32, 922–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; McKinnon, J.; Wolff, S.; Grimwood, D.; Spackman, P.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M. CrystalExplorer, version 17.5; University of Western Australia: Crawley, Australia, 2017.

- Spackman, M.A.; Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsch, C.; Ejsmont, K.; Huder, L. The enrichment ratio of atomic contacts in crystals, an indicator derived from the Hirshfeld surface analysis. IUCrJ 2014, 1, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spackman, P.R.; Turner, M.J.; McKinnon, J.J.; Wolff, S.K.; Grimwood, D.J.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer: A program for Hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. Appl. Crystallogr. 2021, 54, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.F.; Spackman, P.R.; Jayatilaka, D.; Spackman, M.A. CrystalExplorer model energies and energy frameworks: Extension to metal coordination compounds, organic salts, solvates and open-shell systems. IUCrJ 2017, 4, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA—type density functional constructed with a long—range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. Appl. Crystallogr. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, P.A.; Olsson, T.S.; Cole, J.C.; Cottrell, S.J.; Feeder, N.; Galek, P.T.; Groom, C.R.; Pidcock, E. Evaluation of molecular crystal structures using Full Interaction Maps. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Davis, R.E.; Shimoni, L.; Chang, N.L. Patterns in hydrogen bonding: Functionality and graph set analysis in crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1555–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C. Encoding and decoding hydrogen-bond patterns of organic compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.L.; Jotani, M.M.; Tiekink, E.R. Utilizing Hirshfeld surface calculations, non-covalent interaction (NCI) plots and the calculation of interaction energies in the analysis of molecular packing. Struct. Rep. 2019, 75, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Nagata, C.; Shingu, H. Molecular orbital theory of orientation in aromatic, heteroaromatic, and other conjugated molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1954, 22, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. Science 1982, 218, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Pivovar, B.S. Hydroxide degradation pathways for substituted benzyltrimethyl ammonium: A DFT study. ECS Electrochem. Lett. 2015, 4, F13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Compound | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical formula | C20H32Cl6N2Pt | C10H16AuCl4N | C20H32Cl4CuN2 | C20H32Br4CuN2 |

| Formula weight | 708.26 | 489.00 | 505.81 | 683.65 |

| Temperature/K | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) | 100(2) |

| Crystal system | monoclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic |

| Space group | P21/c | C2/c | P21/n | P212121 |

| a/Å | 10.9703(2) | 16.7055(3) | 9.49010(16) | 9.1205(2) |

| b/Å | 11.9807(3) | 14.3876(2) | 9.02423(19) | 9.6086(3) |

| c/Å | 9.6767(2) | 13.9779(2) | 27.9964(4) | 28.8970(7) |

| α/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β/° | 91.7727(19) | 114.613(2) | 92.1082(14) | 90 |

| γ/° | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume/Å3 | 1271.22(5) | 3054.37(9) | 2396.01(8) | 2532.38(11) |

| Z | 2 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.850 | 2.127 | 1.402 | 1.793 |

| μ/mm−1 | 16.206 | 10.308 | 5.442 | 8.661 |

| F(000) | 692.0 | 1840.0 | 1052.0 | 1340.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.39 × 0.06 × 0.05 | 0.18 × 0.09 × 0.04 | 0.24 × 0.17 × 0.08 | 0.36 × 0.28 × 0.06 |

| Radiation | CuKα (λ = 1.54184) | MoKα (λ = 0.71073) | CuKα (λ = 1.54184) | CuKα (λ = 1.54184) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 8.064 to 136.446 | 4.28 to 52.744 | 6.318 to 134.158 | 6.118 to 134.138 |

| Index ranges | −13 ≤ h ≤ 13, −14 ≤ k ≤ 13, −11 ≤ l ≤ 11 | −20 ≤ h ≤ 20, −17 ≤ k ≤ 17, −17 ≤ l ≤ 17 | −9 ≤ h ≤ 11, −10 ≤ k ≤ 10, −33 ≤ l ≤ 32 | −10 ≤ h ≤ 8, −11 ≤ k ≤ 11, −30 ≤ l ≤ 34 |

| Reflections collected | 18,563 | 30,718 | 24,060 | 8980 |

| Independent reflections | 2327 [Rint = 0.0414, Rsigma = 0.0185] | 3126 [Rint = 0.0305, Rsigma = 0.0149] | 4294 [Rint = 0.0305, Rsigma = 0.0194] | 4524 [Rint = 0.0271, Rsigma = 0.0313] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2327/0/136 | 3126/0/150 | 4294/0/250 | 4524/0/250 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.072 | 1.069 | 1.202 | 1.049 |

| Final R indexes [I ≥ 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0203, wR2 = 0.0466 | R1 = 0.0120, wR2 = 0.0250 | R1 = 0.0361, wR2 = 0.0873 | R1 = 0.0226, wR2 = 0.0562 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0223, wR2 = 0.0481 | R1 = 0.0145, wR2 = 0.0257 | R1 = 0.0388, wR2 = 0.0884 | R1 = 0.0240, wR2 = 0.0567 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole/e Å−3 | 1.65/−0.92 | 0.61/−0.35 | 0.56/−0.45 | 0.31/−0.51 |

| D-H…A | D-H [Å] | H…A [Å] | D…A [Å] | H…A [o] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| C7-H7A…Cl15 i | 0.97 | 2.63 | 3.563(4) | 162 |

| C10-H10A…Cl13 | 0.96 | 2.76 | 3.655(4) | 155 |

| Symmetry code: (i) x, 3/2-y, ½ + z | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| C7-H7A…Cl16 i | 0.97 | 2.82 | 3.701(2) | 152 |

| (i) 3/2-x, −1/2 + y, 3/2-z | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| C4A-H4A…Cl15 i | 0.93 | 2.77 | 3.615(3) | 152 |

| C7B-H7BB…Cl13 ii | 0.97 | 2.83 | 3.724(3) | 154 |

| C9B-H9BB…Cl16 iii | 0.96 | 2.82 | 3.688(3) | 151 |

| C11B-H11D…Cl16 iv | 0.96 | 2.75 | 3.646(3) | 155 |

| C11B-H11E…Cl16 iii | 0.96 | 2.77 | 3.654(3) | 153 |

| Symmetry codes: (i) x, −1 + y, z; (ii) 1 + x, −1 + y, z; (iii) 1 + x, y, z; (iv) 3/2-x, −1/2 + y, ½-z | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| C9A-H9AA…Br13 i | 0.96 | 2.92 | 3.802(5) | 153 |

| C4B-H4B…Br15 ii | 0.93 | 2.86 | 3.693(5) | 149 |

| C11A-H11A…Br13 iii | 0.96 | 2.89 | 3.786(5) | 155 |

| C11B-H11D…Br14 iv | 0.96 | 2.91 | 3.838(5) | 164 |

| Symmetry codes: (i) −1 + x, y, z; (ii) ½ + x, ½-y, 1-z; (iii) −1/2 + x, ½-y, 1-z; (iv) ½-x, 1-y, ½ + z | ||||

| Compound | (BTMA)2[PtCl6] | (BTMA)[AuCl4] | (BTMA)2[CuCl4] | (BTMA)2[CuBr4] | BTMA+ in H2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | X-ray | X-ray | X-ray | X-ray | MP2 |

| Bond lengths [Å] | |||||

| C1–C2 | 1.393(5) | 1.392(3) | 1.396(4)/1.392(4) | 1.391(6)/1.393(7) | 1.399 |

| C2–C3 | 1.392(5) | 1.389(3) | 1.386(5)/1.389(4) | 1.388(7)/1.370(7) | 1.393 |

| C3–C4 | 1.383(6) | 1.379(4) | 1.382(5)/1.381(5) | 1.379(8)/1.379(7) | 1.395 |

| C4–C5 | 1.383(6) | 1.380(4) | 1.384(4)/1.386(6) | 1.388(7)/1.379(7) | 1.395 |

| C5–C6 | 1.385(5) | 1.379(3) | 1.388(4)/1.390(4) | 1.377(7)/1.402(6) | 1.393 |

| C6–C1 | 1.395(5) | 1.388(3) | 1.394(4)/1.384(4) | 1.391(7)/1.383(6) | 1.399 |

| C1–C7 | 1.505(5) | 1.500(3) | 1.503(4)/1.502(4) | 1.497(6)/1.511(6) | 1.495 |

| C7–N | 1.521(4) | 1.532(2) | 1.527(4)/1.530(4) | 1.528(5)/1.532(5) | 1.516 |

| N–Cmet | 1.488(4) | 1.508(3) | 1.494(4)/1.499(4) | 1.499(5)/1.493(6) | 1.488 |

| 1.518(4) | 1.499(3) | 1.502(4)/1.498(4) | 1.507(6)/1.507(6) | 1.490 | |

| 1.492(4) | 1.497(3) | 1.500(4)/1.500(4) | 1.504(5)/1.495(6) | 1.488 | |

| Bond angles [deg] | |||||

| C1–C2–C3 | 120.6(3) | 119.9(2) | 120.1(3)/120.3(3) | 120.5(5)/120.2(4) | 120.3 |

| C2–C3–C4 | 120.1(4) | 120.4(2) | 120.1(3)/120.2(3) | 120.2(4)/120.7(5) | 120.0 |

| C3–C4–C5 | 119.6(3) | 119.8(2) | 120.2(3)/119.9(3) | 119.5(5)/119.5(4) | 119.9 |

| C4–C5–C6 | 120.8(4) | 120.1(2) | 120.1(3)/119.8(3) | 120.4(5)/120.7(4) | 120.0 |

| C5–C6–C1 | 120.3(3) | 120.6(2) | 120.0(3)/120.7(3) | 120.7(4)/119.0(4) | 120.3 |

| C6–C1–C2 | 118.7(3) | 119.1(2) | 119.4(3)/119.1(3) | 118.6(4)/119.9(4) | 119.3 |

| C2–C1–C7 | 120.6(3) | 119.8(2) | 119.9(3)/120.5(3) | 120.7(4)/119.5(4) | 120.3 |

| C6–C1–C7 | 120.4(3) | 121.0(2) | 120.7(2)/120.4(3) | 120.6(5)/120.6(4) | 120.3 |

| C1–C7–N | 115.3(2) | 114.7(2) | 114.0(2)/113.3(2) | 113.9(3)/113.9(3) | 113.9 |

| C7–N–Cmet | 111.1(3) | 110.6(2) | 111.2(2)/109.2(2) | 111.5(3)/111.3(3) | 111.1 |

| 106.8(2) | 107.6(2) | 107.2(2)/107.6(2) | 107.7(3)/107.4(3) | 107.4 | |

| 111.9(2) | 112.1(2) | 111.2(2)/111.0(2) | 110.7(3)/111.2(3) | 111.1 | |

| Dihedral angles [deg] | |||||

| C1–C2–C3–C4 | −1.1(5) | −1.0(4) | −0.5(5)/0.5(5) | 0.8(7)/0.6(7) | 0.0 |

| C2–C3–C4–C5 | 1.0(6) | 0.1(4) | 0.0(5)/−1.6(5) | −1.9(7)/−1.5(7) | 0.0 |

| C3–C4–C5–C6 | −0.3(5) | 0.2(4) | −0.2(5)/0.7(5) | 0.4(7)/0.9(6) | 0.0 |

| C4–C5–C6–C1 | −0.3(5) | 0.4(4) | 1.0(5)/1.3(5) | 2.3(7)/0.5(6) | 0.0 |

| C6–C1–C2–C3 | 0.5(5) | 1.6(3) | 1.3(5)/1.5(5) | 1.9(7)/0.8(6) | 0.0 |

| C3–C2–C1–C7 | 174.8(3) | 178.6(2) | 179.0(3)/−177.1(3) | −178.3(4)/179.8(4) | 179.7 |

| C2–C1–C7–N | 90.7(4) | 89.8(3) | 92.0(3)/92.2(3) | 94.2(5)/91.6(5) | 90.7 |

| C1–C7–N–Cmet | 71.6(3) | 63.0(2) | 62.5(3)/63.7(3) | 65.6(4)/68.9(5) | 61.0 |

| −167.5(3) | −177.7(2) | −178.4(3)/−177.4(2) | −175.6(3)/−172.3(4) | 180.0 | |

| −51.8(4) | −57.8(2) | −59.7(3)/−58.4(3) | −56.2(5)/−53.8(5) | −61.0 |

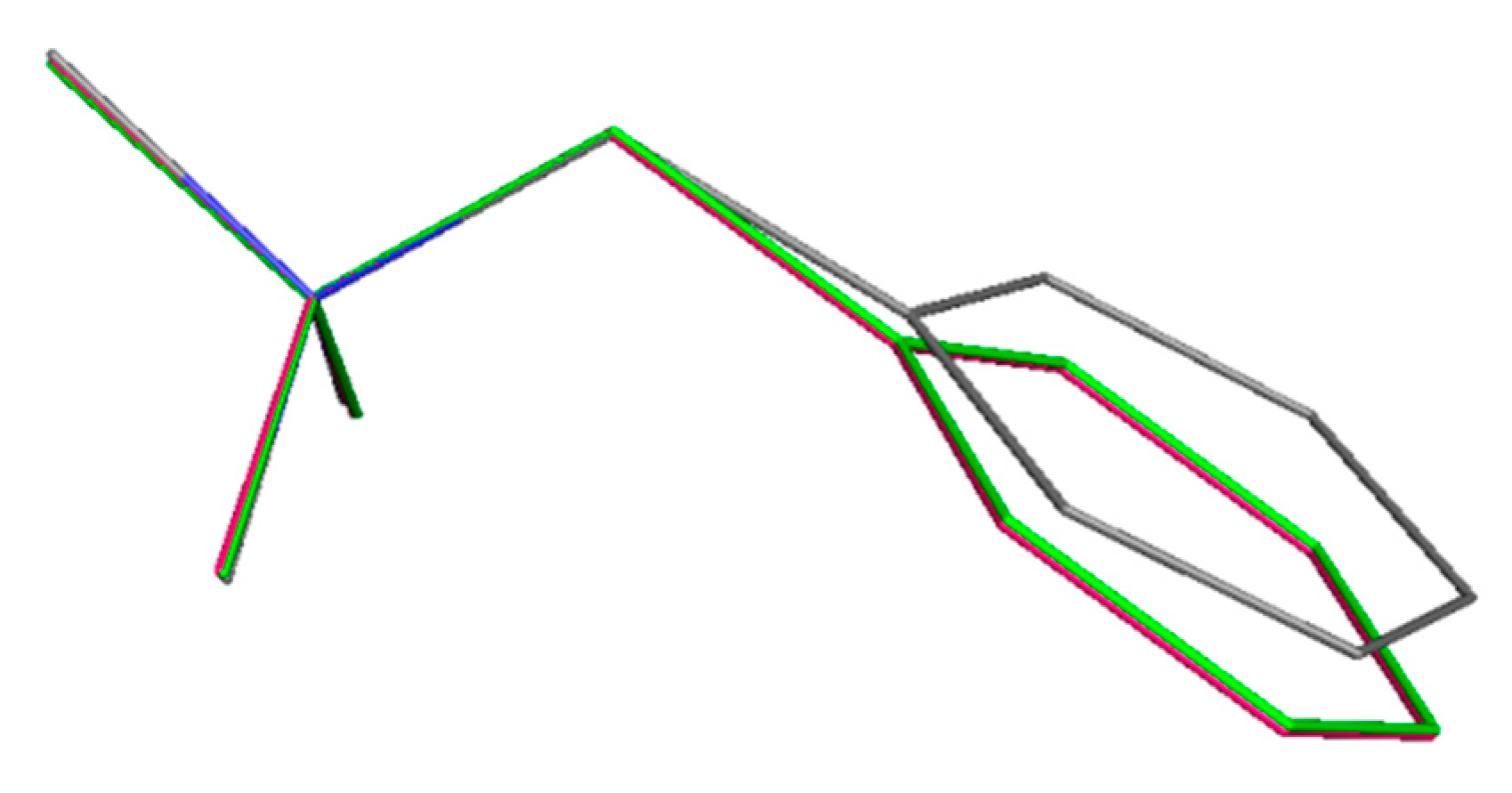

| MP2 optimized in vacuum vs. X-ray structure | 0.131 |

| MP2 optimized in solvent vs. X-ray structure | 0.130 |

| MP2 optimized in vacuum vs. in solution | 0.006 |

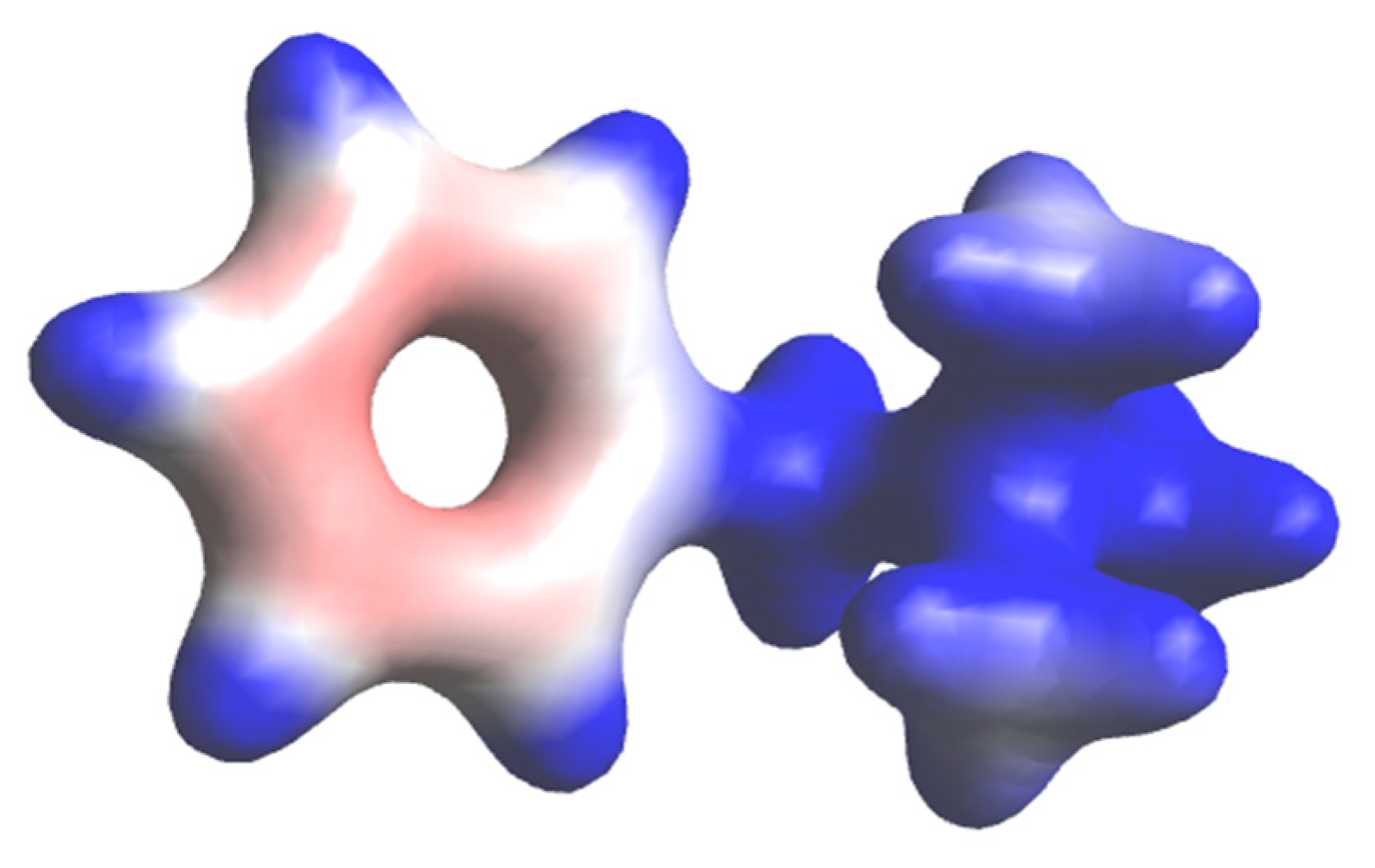

| Environment | Vacuum | Aqueous Solution |

|---|---|---|

| εHOMO [eV] | −12.66 | −9.28 |

| εLUMO [eV] | −0.70 | 3.01 |

| Δε [eV] | 11.96 | 12.28 |

| q | V [bohr3] | |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | −0.04 | 65 |

| C2 | −0.05 | 80 |

| C3 | −0.05 | 85 |

| C4 | −0.05 | 85 |

| C5 | −0.05 | 85 |

| C6 | −0.05 | 80 |

| C7 | 0.24 | 52 |

| N | −0.98 | 49 |

| Cmet | 0.25 (3×) | 62 (3×) |

| H2 | 0.07 | 46 |

| H3 | 0.07 | 47 |

| H4 | 0.07 | 47 |

| H5 | 0.07 | 47 |

| H6 | 0.07 | 46 |

| H7 | 0.09 (2×) | 43 (2×) |

| Hmet | 0.08 (9×) | 44 (9×) |

| ρBCP [e/bohr3] | ∇2ρBCP [e/bohr5] | εBCP | DI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1–C2 | 0.3163 | −1.0245 | 0.194 | 1.134 |

| C2–C3 | 0.3196 | −1.0543 | 0.192 | 1.177 |

| C3–C4 | 0.3188 | −1.0507 | 0.187 | 1.173 |

| C4–C5 | 0.3188 | −1.0507 | 0.187 | 1.173 |

| C5–C6 | 0.3196 | −1.0543 | 0.192 | 1.177 |

| C6–C1 | 0.3163 | −1.0245 | 0.194 | 1.134 |

| C1–C7 | 0.2660 | −0.7386 | 0.019 | 0.867 |

| C7–N | 0.2350 | −0.5842 | 0.034 | 0.734 |

| N–Cmet | 0.2472 (2×) | −0.6567 (2×) | 0.010 (2×) | 0.759 (2×) |

| 0.2464 | −0.6542 | 0.003 | 0.756 | |

| C2–H2 | 0.2930 | −1.1807 | 0.012 | 0.830 |

| C3–H3 | 0.2940 | −1.1901 | 0.012 | 0.843 |

| C4–H4 | 0.2940 | −1.1902 | 0.012 | 0.844 |

| C5–H5 | 0.2940 | −1.1901 | 0.012 | 0.843 |

| C6–H6 | 0.2930 | −1.1807 | 0.012 | 0.830 |

| C7–H7 | 0.2945 (2×) | −1.1864 (2×) | 0.019 (2×) | 0.790 (2×) |

| Cmet–Hmet | 0.295 (2×) | −1.19 (9×) | 0.024 (9×) | 0.80 (2×) |

| 0.294 (7×) | 0.81 (7×) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bojarska, J.; Breza, M.; Jelemenska, I.; Madura, I.D.; Jafari, S.; Trzybiński, D.; Woźniak, K.; Mieczkowski, A. The Comparative Study of Four Hexachloroplatinate, Tetrachloroaurate, Tetrachlorocuprate, and Tetrabromocuprate Benzyltrimethylammonium Salts: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures, Non-Classical Synthon Preference, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, and Quantum Chemical Study. Crystals 2025, 15, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121051

Bojarska J, Breza M, Jelemenska I, Madura ID, Jafari S, Trzybiński D, Woźniak K, Mieczkowski A. The Comparative Study of Four Hexachloroplatinate, Tetrachloroaurate, Tetrachlorocuprate, and Tetrabromocuprate Benzyltrimethylammonium Salts: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures, Non-Classical Synthon Preference, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, and Quantum Chemical Study. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121051

Chicago/Turabian StyleBojarska, Joanna, Martin Breza, Ingrid Jelemenska, Izabela D. Madura, Sepideh Jafari, Damian Trzybiński, Krzysztof Woźniak, and Adam Mieczkowski. 2025. "The Comparative Study of Four Hexachloroplatinate, Tetrachloroaurate, Tetrachlorocuprate, and Tetrabromocuprate Benzyltrimethylammonium Salts: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures, Non-Classical Synthon Preference, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, and Quantum Chemical Study" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121051

APA StyleBojarska, J., Breza, M., Jelemenska, I., Madura, I. D., Jafari, S., Trzybiński, D., Woźniak, K., & Mieczkowski, A. (2025). The Comparative Study of Four Hexachloroplatinate, Tetrachloroaurate, Tetrachlorocuprate, and Tetrabromocuprate Benzyltrimethylammonium Salts: Synthesis, Single-Crystal X-Ray Structures, Non-Classical Synthon Preference, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, and Quantum Chemical Study. Crystals, 15(12), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121051