Abstract

Powder metallurgy is an ideal technique for manufacturing metal matrix composites, owing to its capacity for near-net shape production and minimal material waste. However, a characteristic feature of the aluminum green compacts during the sintering process is the presence of natural oxide films on the surfaces of aluminum powders, which limits the application of aluminum powder metallurgy technology. To address this, we propose a sonication-assisted mixing and liquid metal sintering strategy by which aluminum powder can be easily sintered at the temperature as low as 623 K, two-thirds of the melting point of aluminum. The present investigation demonstrates that the molten gallium enhances metallurgical bonding between the aluminum particles by acting as a “bridge” between adjacent aluminum particles and disrupting the oxide film inevitably existing on the outermost layer of aluminum powder. According to the performance analysis results, when the sintering temperature is as low as two-thirds of the melting point of aluminum, the compressive strength of the Al-5Ga sample increases by 62.5% compared with that of pure aluminum. This innovation will help powder metallurgy researchers to pursue sintering at low-temperature and has a sweeping impact on a wide range of powder metallurgy applications.

1. Introduction

Aluminum as a lightweight metal has potential for use in both automotive and aerospace applications. In general, the higher the strength of aluminum alloys, the more challenging and expensive it is to shape into parts [1]. Thus, ever-increasing efforts have been made to advance all aspects of aluminum technology [2]. Developing new manufacturing technologies is of prime importance to enable broader applications of aluminum alloys [3]. Aluminum products can be processed via powder metallurgy techniques to manufacture net or near-net-shape components in a cost-effective and sustainable manner.

Aluminum powder metallurgy technology is a two-step process. First, the powder is consolidated into cylindrical and rectangular pellets using a uniaxial die. This step aims to reduce interparticle voids and impart a certain strength to the green compacts. The second step is sintering densification [4,5]. The compacted green compacts undergo heat treatment at temperatures below the melting point of aluminum. During the sintering process, powder particles bond with each other through diffusion, forming a dense solid structure that enhances the material’s strength. However, a characteristic feature of the aluminum powder sintering process is the presence of natural oxide films on the particle surfaces. During the sintering process, the oxide layer on the powder hinders sintering by slowing mass transport mechanisms responsible for neck formation [6,7,8]. Solid-state sintering of aluminum powder in green parts is kinetically unfeasible because the diffusion of aluminum atoms through the continuous oxide film is severely impeded [9]. This is because the diffusion coefficient of aluminum atoms through Al2O3 is several orders of magnitude lower in comparison to its self-diffusion coefficient [10].

To reduce energy consumption, powder metallurgy researchers have struggled to pursue sintering at low-temperature in recent decades [11]. However, the sintering temperature for most aluminum green compacts currently remains above 723 K. Zhang et al. [12] studied the effect of sintering temperature on the microstructure and properties of Al-7.5Cu-1Si alloy. They found that when the temperature was 843 K, aluminum particles achieved good metallurgical bonding, resulting in a favorable microstructure and the alloy’s highest strength. Yuan et al. [13] reported that when the green compacts of Al-based alloy by high-velocity compaction were sintered at 913 K, the mechanical properties of the samples were optimum. Ibrahim et al. [14] studied the sintering of Al-Mg-Si powder metallurgy alloys at temperatures in the range of 883–913 K. Their investigation showed that the optimum sintering profile of the Al-Mg-Si alloys consists of ramping to 903 K and holding it for 30 min. Wu et al. [15] proposed a novel low-pressure sintering process. They found that the 2024Al samples sintered under a low pressure of 0.1 MPa at 848 K could achieve good mechanical performance. Mendoza-Duarte et al. [11] reported that high-quality sintered nanocrystalline materials with optimal mechanical properties were obtained by high-frequency induction sintering at 723 K. From the above, it can be found that to obtain aluminum powder metallurgy parts with good metallurgical bonding, the sintering temperature (K) of most green compacts needs to be above 0.9 Tm (melting point) of aluminum. Even when high-frequency induction sintering is used, a temperature of 0.8 Tm of aluminum is still required.

Noticeably, gallium has been employed as an interlayer for the flux-free brazing of aluminum alloys [16]. Studies by Ferchaud et al. [17] indicate that gallium has the effect of disrupting the oxide film on the aluminum surface. By adopting the gallium diffusion bonding technique, a high-quality diffusion bonding joint between aluminum alloys was obtained, attributed to the surface activation of aluminum alloys induced by gallium during brazing. Importantly, gallium can break down the oxide film on the surface of aluminum, which facilitates the mutual diffusion of aluminum particles during the sintering process, resulting in the formation of good metallurgical bonding between aluminum particles. According to the Ga-Al binary phase diagram, aluminum cannot form intermetallic compounds with gallium, but can form an Al-Ga solid solution. Because intermetallic compounds are usually brittle, the excessive formation of intermetallic compounds leads to the deterioration of components’ performance. However, solid solutions usually exhibit good comprehensive mechanical properties. In addition, the formation of the Al-Ga solid solution facilitates interatomic diffusion. Therefore, gallium was applied to the sintering of aluminum powder.

To address this challenge, here, we propose a sonication-assisted mixing and liquid metal sintering strategy by which aluminum powder can be easily sintered at the temperature as low as 623 K, two-thirds of the melting point of aluminum. We conduct phase composition and microstructure analyses to clarify the underlying mechanisms. Moreover, we characterize the mechanical properties of the aluminum products to demonstrate the validity of our method and the novelty of the obtained materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The purities of gallium (Jiaru New Materials Group Co., Ltd., Nantong, China) and aluminum (Naiou Nano Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) used in the present study are 99.99% and 99.9%, respectively, and the average particle size of the aluminum powder is 10 μm. Any child building sandcastles realizes it is effortless to mix sand with water. Although gallium is in a liquid state near room temperature, for liquid gallium and aluminum particles, this mixing process becomes challenging due to the high surface tension of the liquid metal. Here, we propose a sonication-assisted method to mix aluminum and gallium, as shown in Figure 1. During the sonication process, bulk liquid gallium was added to absolute ethanol (≥99.9%; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 308 K. The bulk gallium was split into micro-sized spherical or quasi-spherical particles, as shown in Figure 1a. Then, the aluminum powder and gallium powder were mixed by mechanical stirring in an argon atmosphere, as illustrated in Figure 1b. Figure 1c shows the final morphological characteristics and distribution of gallium and aluminum mixed particles following sonication and mechanical agitation. According to the principle of backscattered electron imaging, the brightness of the image increases as the atomic number increases. Since gallium (atomic number: 31) has a higher atomic number than aluminum (atomic number: 13), the bright particles observed in Figure 1c are inferred to be gallium particles.

Figure 1.

Preparation of gallium and aluminum mixed particles: (a) Preparation process of gallium particles by sonication-assisted method; (b) Mixing process of gallium and aluminum particles; (c) Backscattered electron images of Al-5Ga mixed particles.

Afterwards, the gallium and aluminum mixed particles were consolidated into cylindrical blocks using a uniaxial die. The green compacts of Al-xGa (x = 0, 5, 10, 15) were prepared. The samples were sintered in a tube furnace in an argon atmosphere with the following heating profile: the samples were heated from room temperature to 623 K at a rate of 5 K/min, then held at the sintering temperature for 1 h, and finally cooled to room temperature naturally.

2.2. Characterization

The surface topography of the samples was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S4800, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). An X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D8 Advance, Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany) was employed to analyze the crystalline structures of the samples. The compressive strength of the samples was measured by an electronic universal testing machine (SANS-CMT5105, MTS, Shenzhen, China), and the testing speed for the compressive strength tests was set to 0.5 mm/min. The contact angle of gallium droplets on the bed of aluminum powder was determined using a contact angle analyzer (CA, SCI2000A, Shanghai Zhongchen Digital Technology and Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

3. Results and Discussion

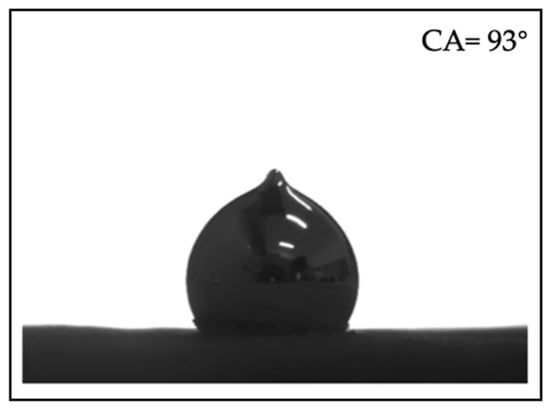

3.1. Wettability

Glass microscope slides were covered with double-sided adhesive tape, and aluminum powder was evenly placed on the tape surface to form “bed of aluminum powder”. The wettability of liquid gallium on the bed of aluminum powder was characterized by contact angle measurement at 308 K, as shown in Figure 2. The results show that the contact angle of gallium droplets on the bed of aluminum powder is 93°, which results in the difficulties in mixing gallium with aluminum. Traditional mechanical methods are ineffective for achieving the desired mixing of aluminum particles with gallium. Therefore, we adopted a sonication-assisted aluminum-gallium mixing method, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Contact angles of gallium droplets on the bed of aluminum powder.

3.2. Phase Composition and Microstructure

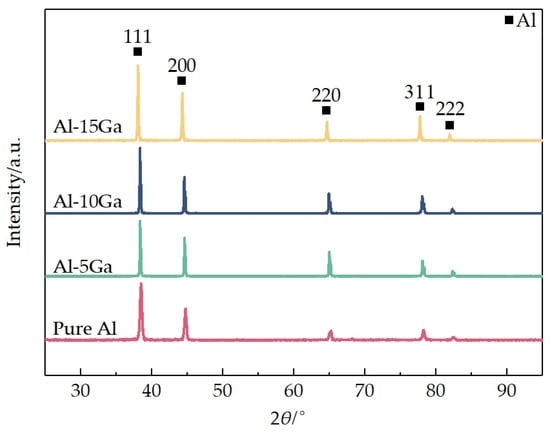

Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of the sintered samples. According to the Ga-Al binary phase diagram, aluminum cannot form intermetallic compounds with gallium, which is further corroborated by the XRD patterns of the sintered samples. It can be clearly observed from Figure 3 that the Al (111) peak in the Al-Ga sintered samples shifts toward the lower 2θ direction. The Bragg equation (d = nλ/2sinθ) reveals an inverse relationship between crystal plane spacing (d) and 2θ angle: larger interplanar spacing corresponds to smaller 2θ values. The observed 2θ shifts between the Al-Ga sintered samples and pure aluminum suggest differences in crystal lattice parameters, which can be attributed to Al-Ga solid solution formation in the Al-Ga samples during the sintering process.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of sintered samples with different gallium contents.

Refinement was applied to the patterns of sintered samples in the 2θ range of 25−95°. Table 1 summarizes the resulting crystallographic parameters and R-factors. Consequently, XRD patterns confirm gallium dissolution into the aluminum matrix, inducing solid solution strengthening through lattice distortion. This also contributes to one of the underlying factors enhancing the strength of the Al-Ga sintered samples described below.

Table 1.

Refinement results of sintered samples.

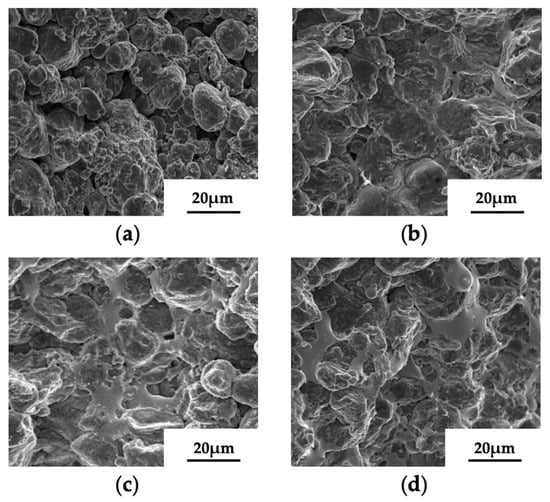

Figure 4 shows the microstructures of sintered samples with different gallium contents. It can be found that many pores are distributed in the pure aluminum sample, while the pores of the sintered Al-Ga samples are fewer. This indicates that for the pure aluminum sample, the particles merely maintain physical contact, demonstrating the absence of good metallurgical bonding. It is well recognized that capillary force is the key driving force for particle bonding to form 3D structures. The construction of sandcastles is a classic case of binding particles via the formation of capillary bridges. In this process, water is transported into the gaps among sand particles via capillary force, enabling loose sand particles to consolidate into stable 3D objects. During the sintering process, the gallium particles in the Al-Ga samples transformed into molten gallium. Owing to the capillary pressure in the gaps among aluminum particles, the molten gallium actively infiltrated into these gaps. Beyond acting as a “liquid bridge” to connect adjacent aluminum particles, the molten gallium rapidly spread across particle surfaces under thermal activation, forming interconnected liquid networks that facilitated particle coalescence. Thus, for the Al-Ga samples, the formation of sintered necks has commenced, accompanied by a transition of interparticle contact from mechanical interlocking to effective metallurgical bonding. As sintering and diffusion times are incrementally prolonged, the sintered necks expand gradually, and the interparticle metallurgical bonding is effectively enhanced via atomic diffusion.

Figure 4.

The surface topography of sintered samples with different gallium contents: (a) pure aluminum sample; (b) Al-5Ga sample; (c) Al-10Ga sample; (d) Al-15Ga sample.

Figure 5 shows the relative densities of the sintered samples with different compositions. As the gallium content increased, the relative densities of the sintered samples increased. As shown in Figure 4, it can be found that the pure aluminum sample contained numerous pores, while the number of pores in the sintered Al-Ga samples was smaller. As the gallium content increased, more liquid phases formed during sintering, and the liquid phases filled the pores in the samples. Thus, the relative densities increased.

Figure 5.

The relative densities of the sintered samples with different compositions.

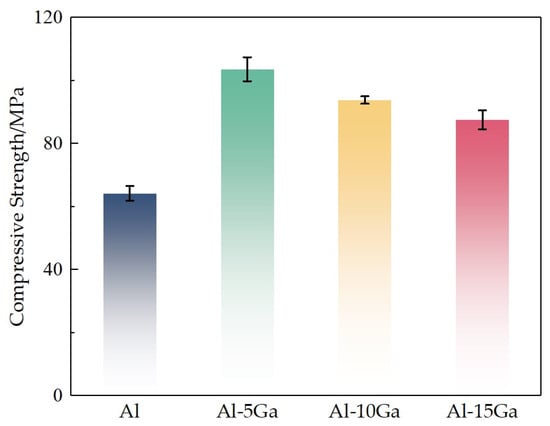

3.3. Compressive Strength

Figure 6 shows the compressive strength of sintered samples. As the gallium content increases, the compressive strength of sintered samples increases first and thereafter decreases. The results show that the compressive strength of pure Al and Al-5Ga samples is 64 MPa and 104 MPa, respectively. The compressive strength of the Al-5Ga alloy has increased by 62.5% compared with that of pure aluminum. It is easy to understand that the enhanced compressive strength of sintered samples prepared with mixed powder can be attributed to three synergistic mechanisms, namely the reduction in pores via gallium filling, the improved metallurgical bonding induced by gallium in the microstructure, and the solid solution strengthening through lattice distortion.

Figure 6.

The compressive strength of sintered samples.

Intergranular failure occurs at unusually low stress levels when aluminum alloy is in contact with liquid gallium [18,19,20,21]. This phenomenon is known as liquid metal embrittlement (LME). Hence, as shown in Figure 6, due to the liquid metal embrittlement, excessive gallium can lead to a decrease in the strength of the samples. In view of this contradiction in the choice of gallium addition, there has to be a trade-off between liquid metal diffusion sintering and embrittlement phenomenon.

The compressive strength of the samples in this work and data of Al matrix composites reported in the literature are summarized in Table 2 [22,23,24]. It can be seen that although the sintering temperature in this work is as low as 623 K, the compressive strength of the Al-5Ga samples is close to the data reported in the literature. This indicates that sintering of aluminum powder at its 2/3 Tm via liquid metal sintering is feasible.

Table 2.

Comparison of the mechanical properties of base aluminum materials.

3.4. Mechanism of Sintering Process

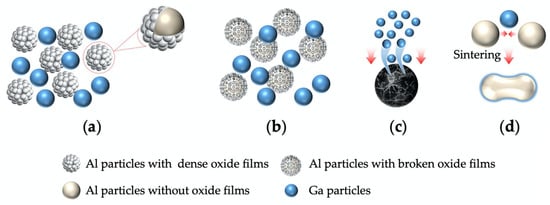

Figure 7 shows the sintering process of mixed gallium and aluminum particles. As shown in Figure 7a, there is a dense oxide film on the surface of aluminum particles. Studies by Ferchaud et al. [17] indicate that gallium has the effect of disrupting the oxide film on the aluminum surface. This has also been confirmed by studies conducted by Skachov et al. [25]. As shown in Figure 7b, the dense oxide film on the surface of aluminum particles is broken due to the action of gallium. Furthermore, Skachov et al. [25] found that after liquid gallium or its alloys spread on the aluminum surface, they activate aluminum, prevent it from forming a protective oxide film, and penetrate into the aluminum matrix. Therefore, as shown in Figure 7c, during sintering gallium penetrates the aluminum grain boundaries, replacing them with a liquid gallium-rich layer. As shown in Figure 7d, rupturing the oxide layer on aluminum also exposes active bare aluminum, which facilitates the formation of diffusion paths via “liquid bridges” formed between adjacent particles. These paths accelerate atom migration, thus initiating the formation of sintered necks.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of gallium and aluminum mixed particles sintering process: (a) During initial sintering, there is a dense oxide film on the surface of aluminum particles; (b) During sintering, the dense oxide film on the surface of aluminum particles is broken due to the action of gallium; (c) During sintering, gallium penetrates the aluminum grain boundaries; (d) Sintering necks are formed between aluminum particles.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Aluminum powder can be easily sintered at 623 K, two-thirds of the melting point of aluminum, via sonication-assisted mixing and liquid metal sintering strategy.

- (2)

- When the sintering temperature is as low as two-thirds of the melting point of aluminum, the compressive strength of the Al-5Ga alloy increases by 62.5% compared with that of pure aluminum.

- (3)

- Gallium can disrupt the Al2O3 film on the aluminum surface, thereby promoting the mutual diffusion between aluminum and gallium atoms and the formation of the Al (Ga) solid solution, which in turn enables aluminum particles to form good metallurgical bonding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.; methodology, J.P.; software, J.P.; validation, T.W. and S.Z.; formal analysis, J.P.; investigation, J.P.; resources, T.W. and S.Z.; data curation, J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, T.W.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, T.W. and S.Z.; project administration, T.W. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, T.W. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marczyk, J.; Hebda, M. Effect of the Particle Size Distribution of Irregular Al Powder on Properties of Parts for Electronics Fabricated by Binder Jetting. Electronics 2023, 12, 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbiec, D.; Jurczyk, M.; Levintant-Zayonts, N.; Mościcki, T. Properties of Al–Al2O3 composites synthesized by spark plasma sintering method. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2015, 15, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Prashanth, K.G.; Zhang, W.W.; Scudino, S.; Eckert, J. Removing the oxide layer in a nanostructured aluminum alloy by local shear deformation between nanoscale phases. Powder Technol. 2019, 343, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimiana, M.; Ehsani, N.; Parvinb, N.; Baharvandi, H. The effect of particle size, sintering temperature and sintering time on the properties of Al–Al2O3 composites, made by powder metallurgy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 5387–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Kunimoto, S.; Ishii, T.; He, L.; Onda, T.; Chen, Z. Improved mechanical properties of mechanically milled Mg2Si particles reinforced aluminum-matrix composites prepared by hot extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 871, 144904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, F.; Dossi, S.; Paravan, C.; Deluca, L.T.; Liljedahl, M. Activated aluminum powders for space propulsion. Powder Technol. 2015, 270, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczyk, J.; Ostrowska, K.; Hebda, M. Influence of binder jet 3D printing process parameters from irregular feedstock powder on final properties of Al parts. Adv. Powder Technol. 2022, 11, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menapace, C.; Cipolloni, G.; Hebda, M.; Ischia, G. Spark plasma sintering behaviour of copper powders having different particle sizes and oxygen contents. Powder Technol. 2016, 291, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Maleksaeedi, S.; Sapari, M.A.B.; Nai, M.L.S.; Meenashisundaram, G.K.; Gupta, M. Additive manufacturing of magnesium–zinc–zirconium (ZK) alloys via capillary-mediated binderless three-dimensional printing. Mater. Des. 2019, 16, 107683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Maleksaeedi, S.; Nai, M.L.S.; Gupta, M. Towards additive manufacturing of magnesium alloys through integration of binderless 3D printing and rapid microwave sintering. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 29, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Duarte, J.M.; Estrada-Guel, I.; Garay-Reyes, C.G.; Perez-Bustamante, R.; Romero-Romero, M.; Carreno-Gallardo, C.; Martínez-Sanchez, R. Influence of process conditions on the mechanical and microstructural features of milled Al sintered with rapid heating. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Deng, Z.; Shou, D.; Gong, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, B.; Yuan, C. Effect of sintering temperature on the microstructure and properties of Al–7.5Cu–1Si alloy. Mater. Res. Express. 2024, 11, 036507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Qu, X.; Yin, H.; Feng, Z.; Tang, M.; Yan, Z.; Tan, Z. Effects of Sintering Temperature on Densification, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Al-Based Alloy by High-Velocity Compaction. Metals 2021, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Bishop, D.P.; Kipouros, G.J. Sinterability and characterization of commercial aluminum powder metallurgy alloy Alumix 321. Powder Technol. 2015, 279, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, Z.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Yan, H.; Liu, W. Microstructure and tensile properties of aluminum powder metallurgy alloy prepared by a novel low-pressure sintering. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadi, A.A.; Saindrenan, G.; Wallach, E.R. Flux-free diffusion brazing of aluminium-based materials using gallium. In Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Bäch, Switzerland, 2002; Volume 396, pp. 1579–1584. Available online: https://www.scientific.net/MSF.396-402.1579 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ferchaud, E.; Christien, F.; Barnier, V.; Paillard, P. Characterisation of Ga-coated and Ga-brazed aluminium. Mater. Charact. 2012, 67, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolman, D.G. A review of recent advances in the understanding of liquid metal embrittlement. Corrosion 2019, 75, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Li, Y.W.; Hu, C.Z.; Xue, S.K.; Xiang, C.Y.; Luo, J.; Yu, Z.Y. The interfacial structure underpinning the Al-Ga liquid metal embrittlement: Disorder vs. order gradients. Scr. Mater. 2021, 204, 114149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, M.; Bhatia, M.A.; Tschopp, M.A.; Srolovitz, D.J.; Solanki, K.N. Atomic-scale analysis of liquid-gallium embrittlement of aluminum grain boundaries. Acta Mater. 2014, 73, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birbilis, N.; Zhang, R.; Lim, M.L.C.; Gupta, R.K.; Davies, C.H.J.; Lynch, S.P.; Kelly, R.G.; Scully, J.R. Quantification of sensitization in AA5083-H131 via imaging Ga-embrittled fracture surfaces. Corrosion 2013, 69, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, V.; Kumar, V.; Bansal, S.A.; Prakash, C.; Ubaidullah, M.; Shaikh, S.F.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Shankar, S. Fabrication of efficient aluminium/graphene nanosheets (Al-GNP) composite by powder metallurgy for strength applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3402–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senel, M.C.; Gurbuz, M. Investigation on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of B4C/Graphene Binary Particles Reinforced Aluminum Hybrid Composites. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 2438–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, A.; Senel, M.C. Tribological Properties and Microstructures of Tungsten Carbide and Few-Layer Graphene-Reinforced Aluminum-Based Composites. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2024, 77, 445–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skachkov, V.M.; Pasechnik, L.A.; Bibanaeva, S.A.; Medyankina, I.S.; Sabirzyanov, N.A. Two types of the effect of gallium on aluminums. Russ. Metall. 2023, 2023, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).