Recent Advances in MoS2-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Structural Features, and Electrochemical Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Modification Techniques

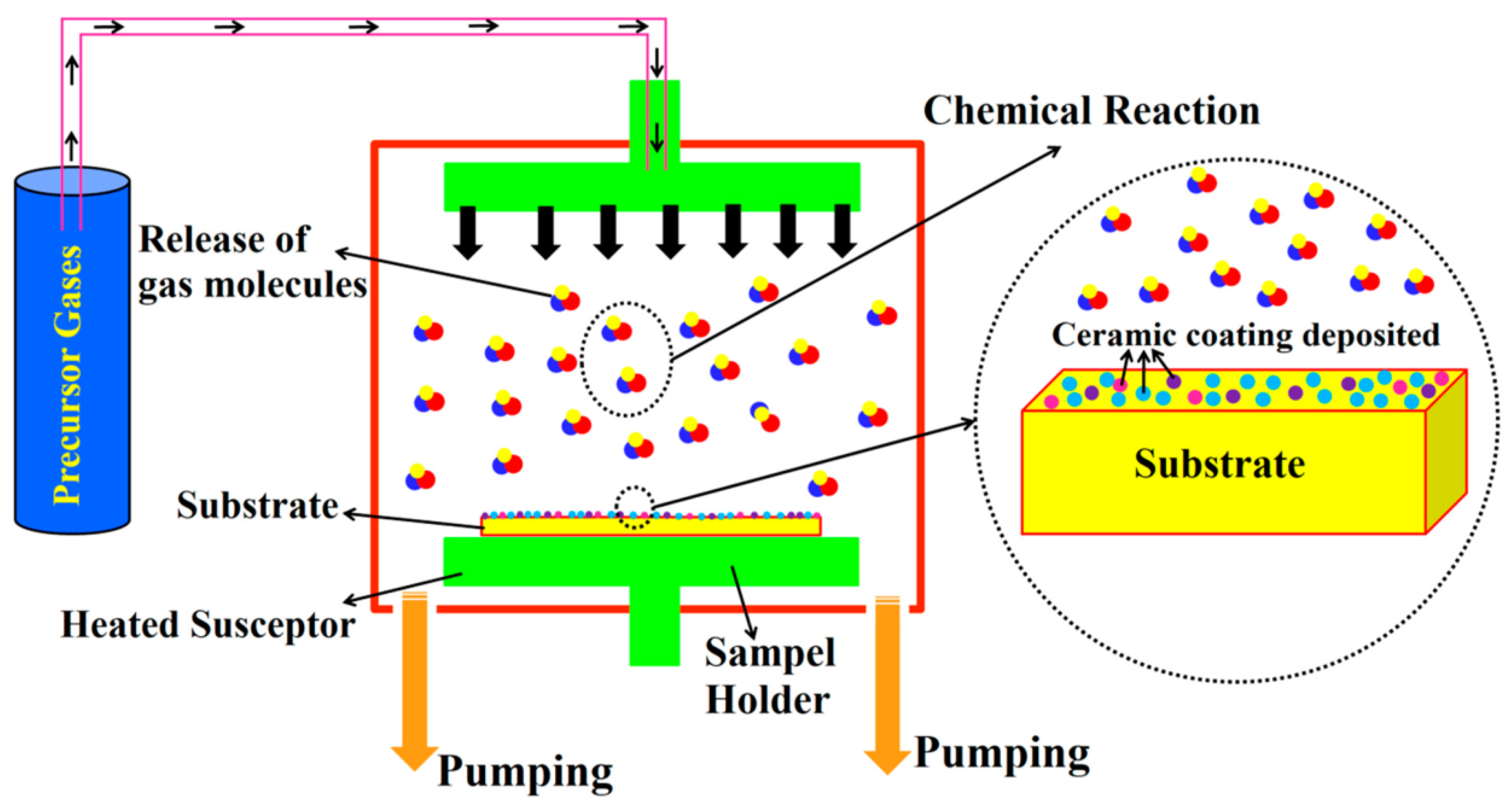

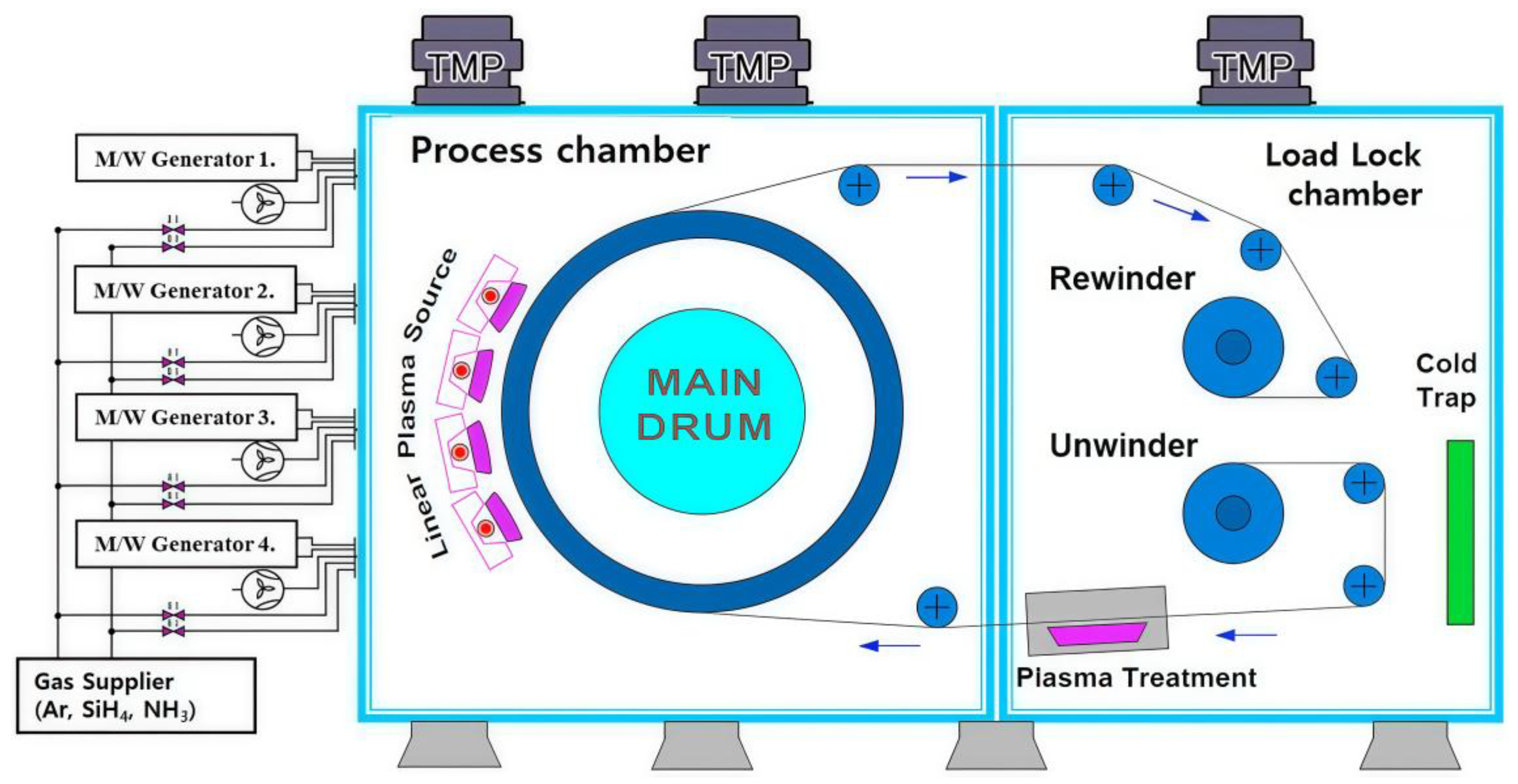

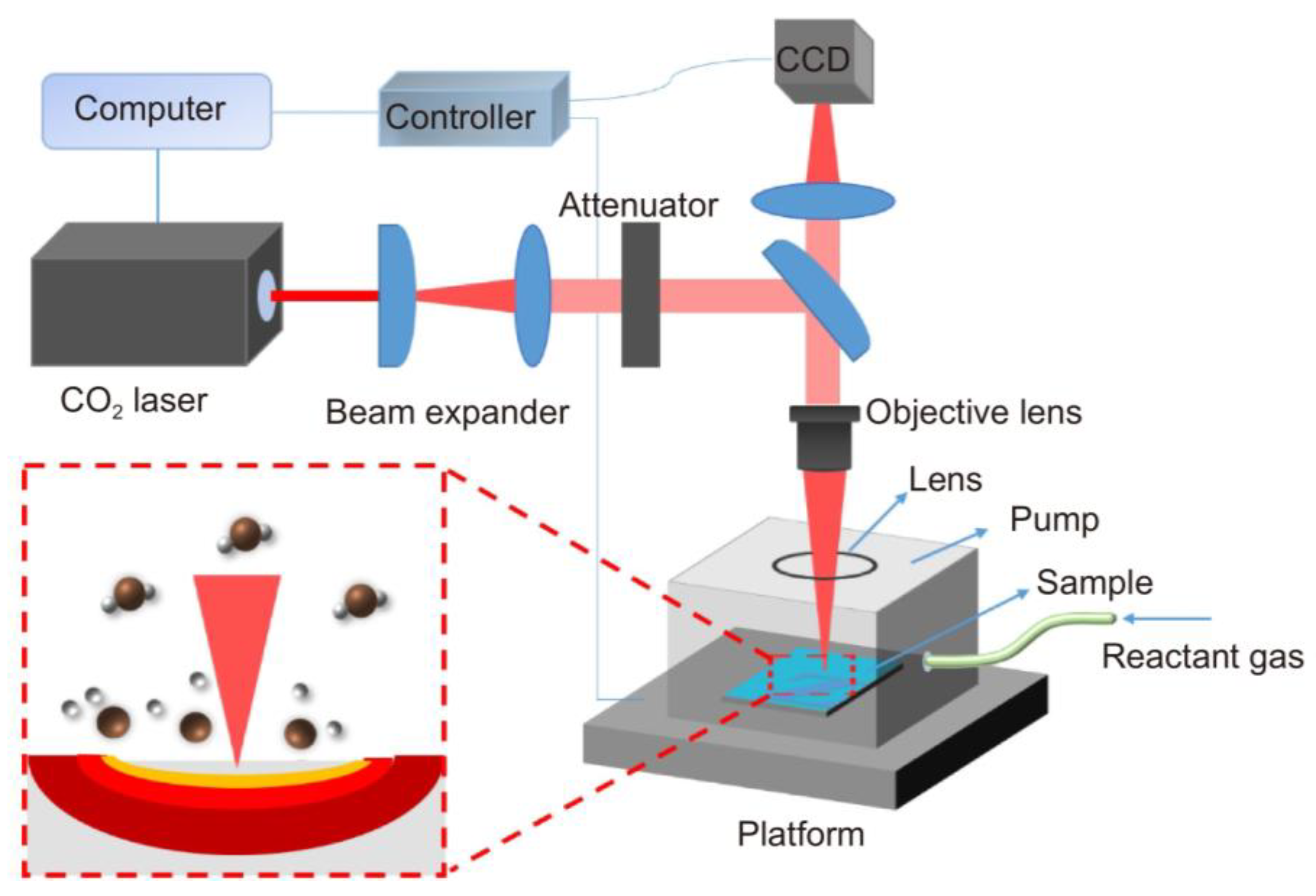

3. The Variety of CVD Methods and Their Role in Creating Functional Coatings

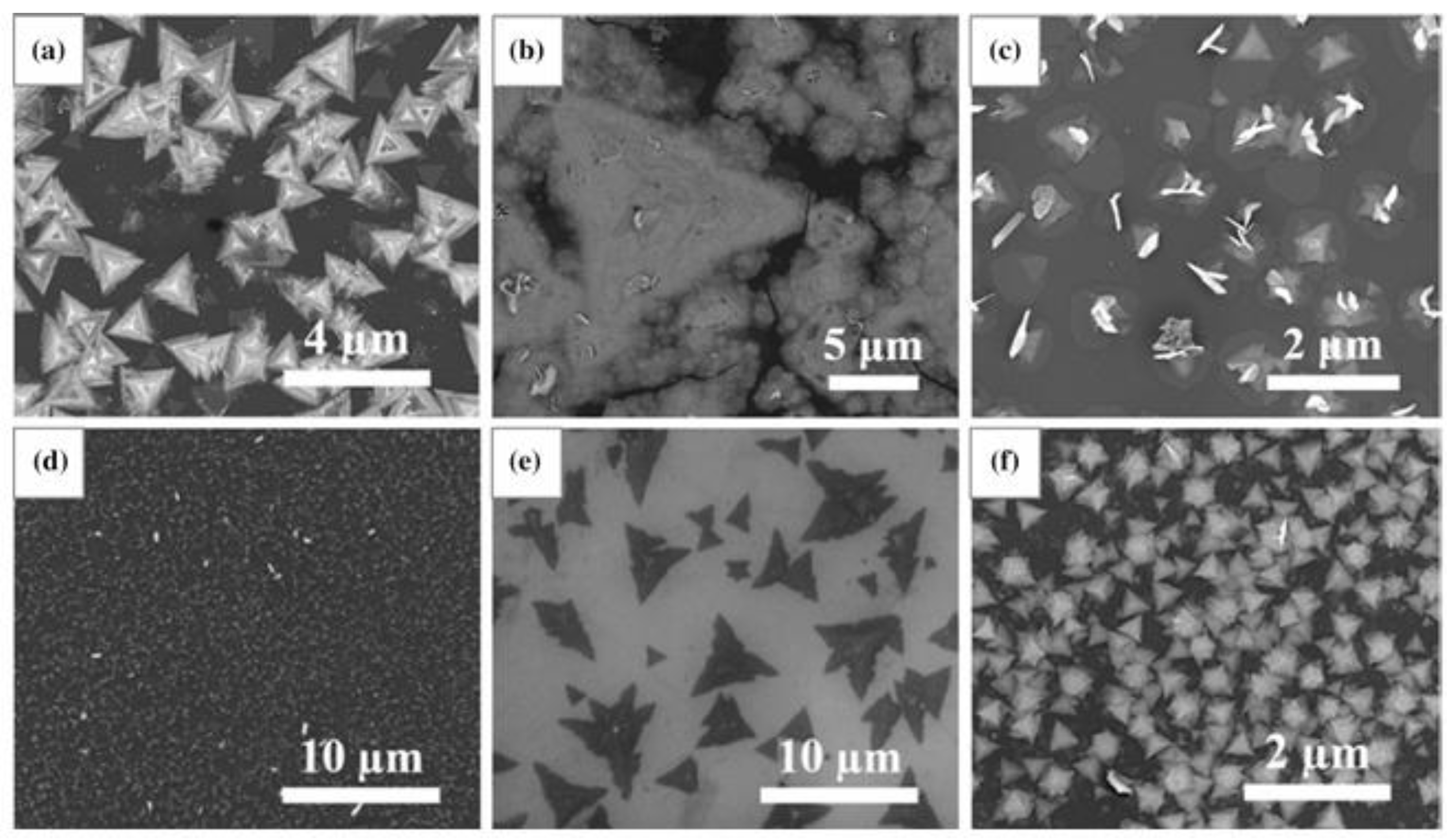

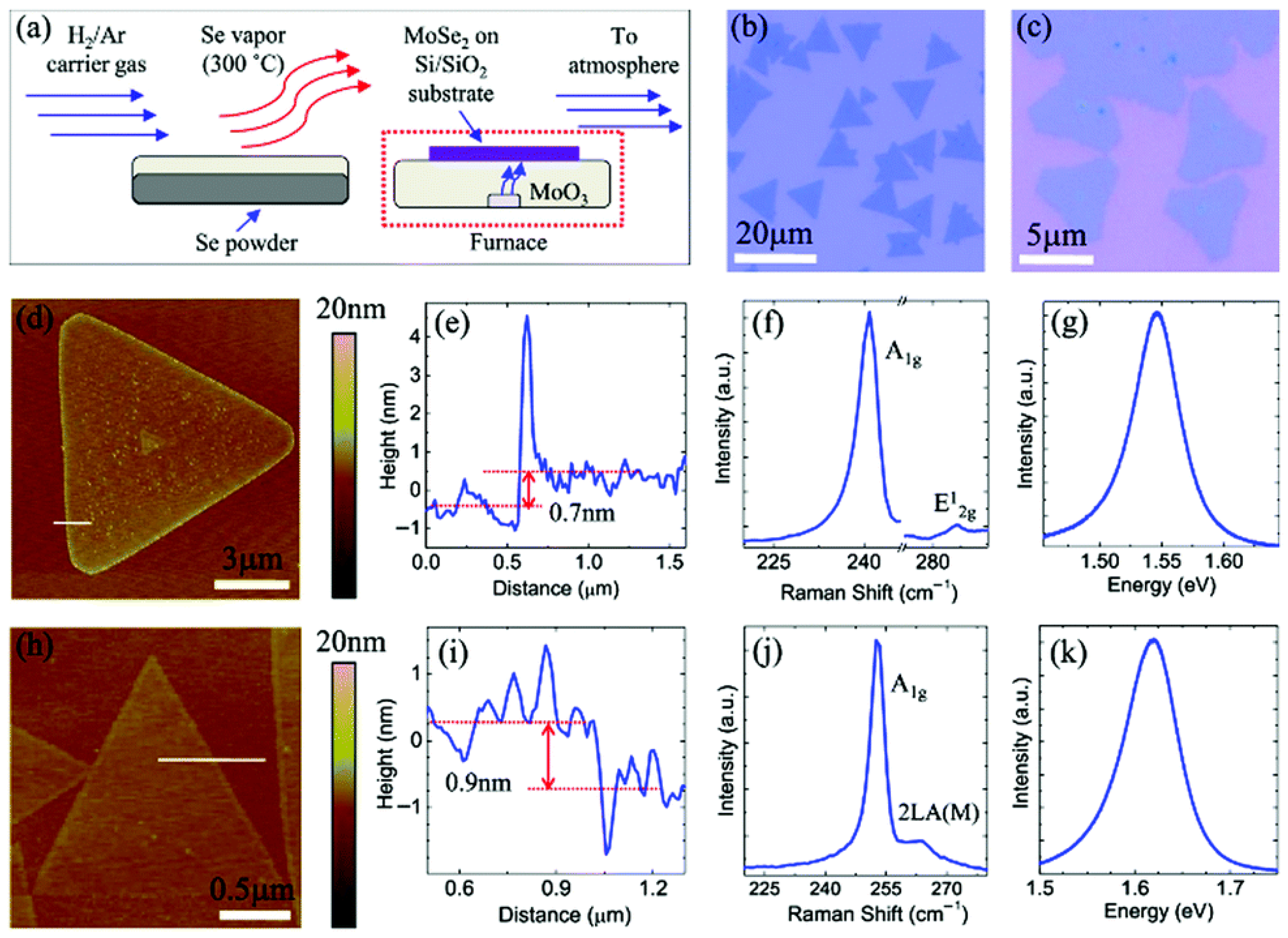

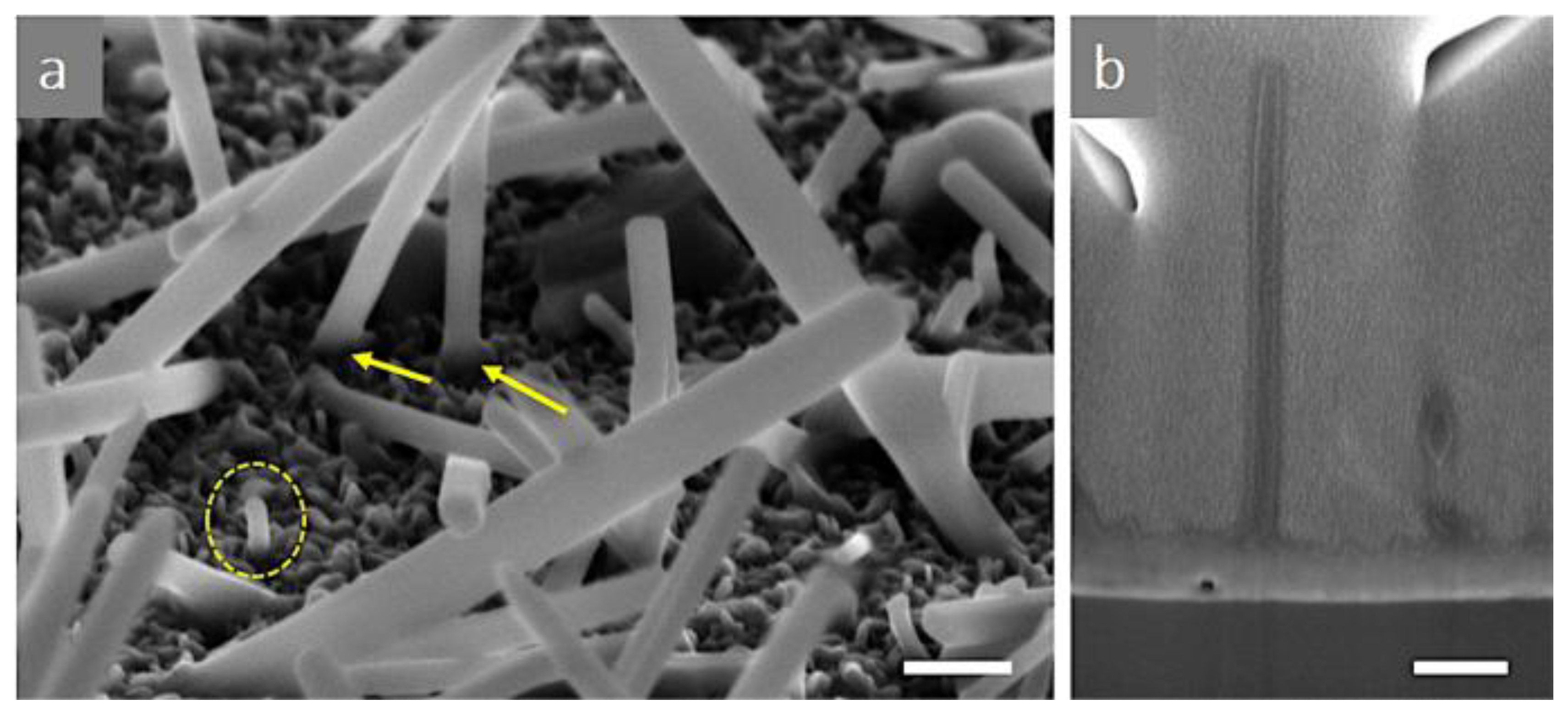

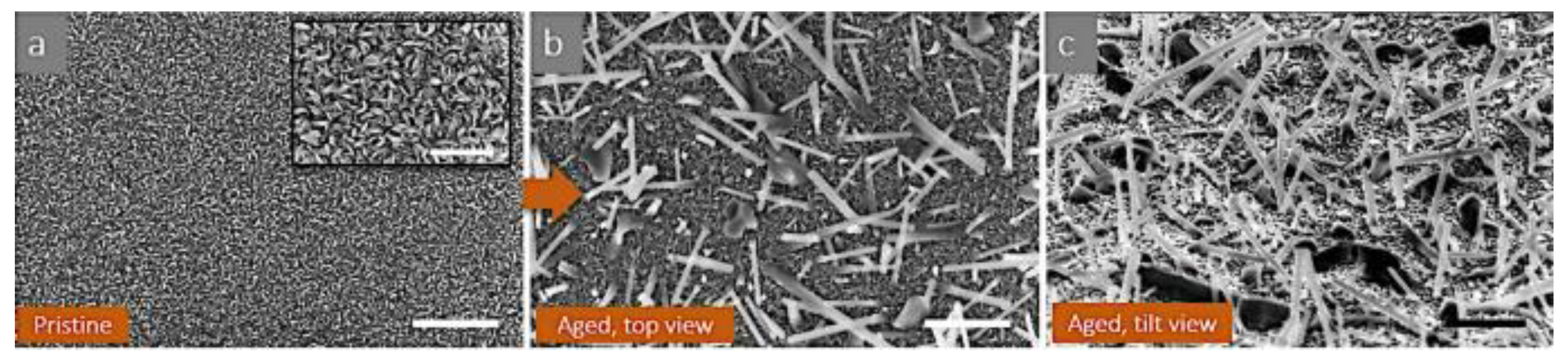

4. Morphological Evolution and Structural Features of CVD-Grown MoS2: The Influence of Growth Parameters, Substrate, and Holding Time

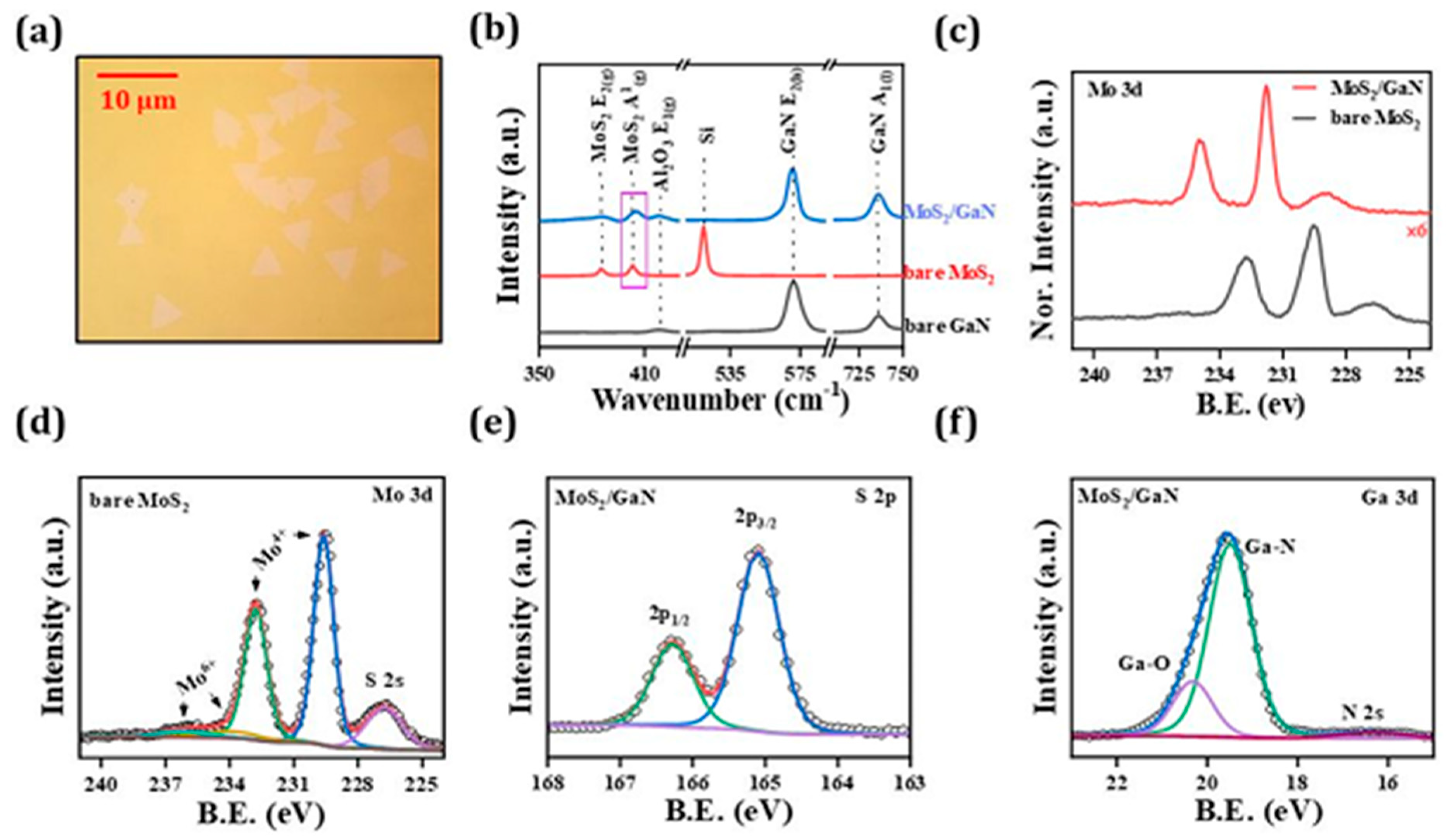

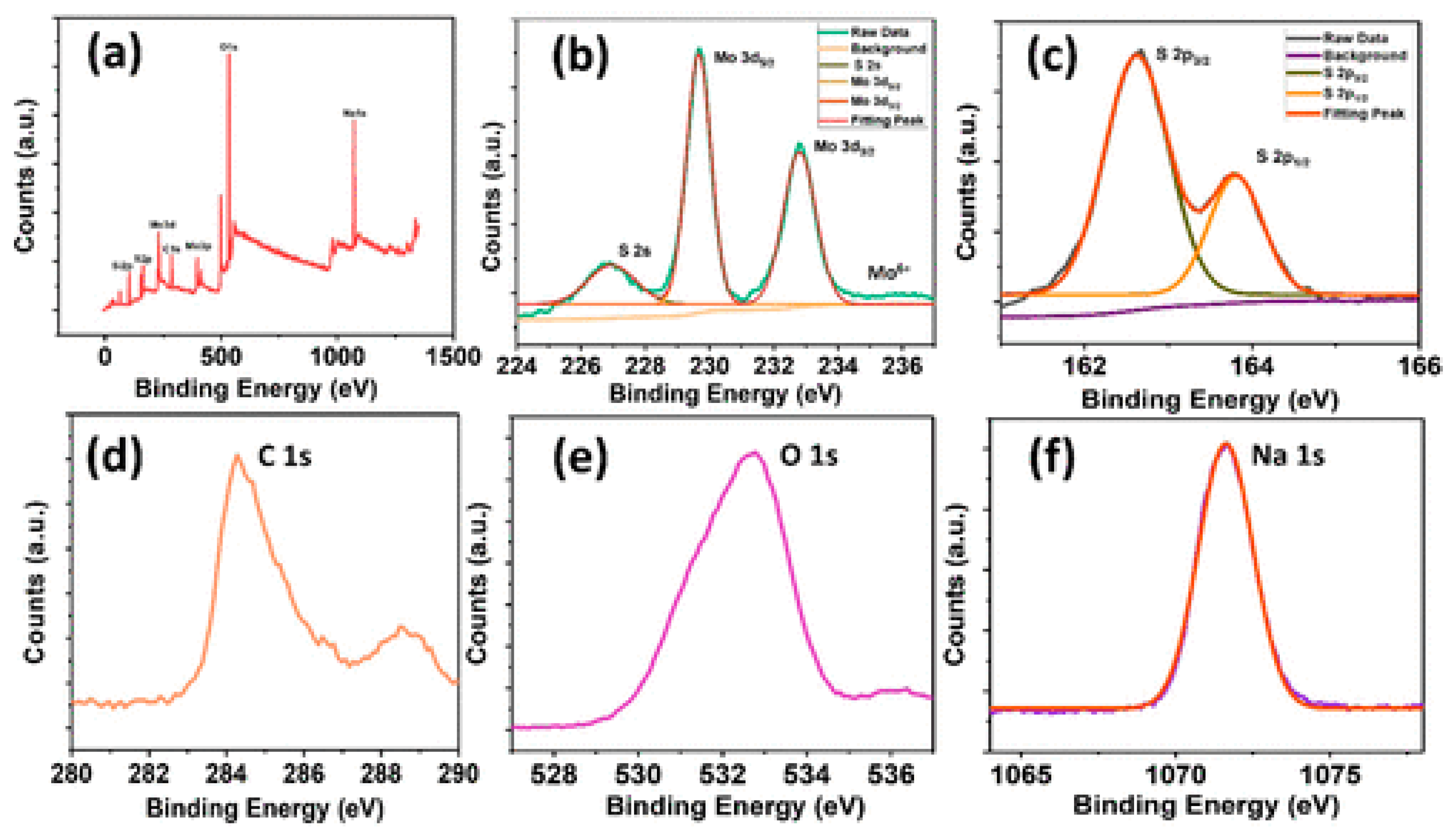

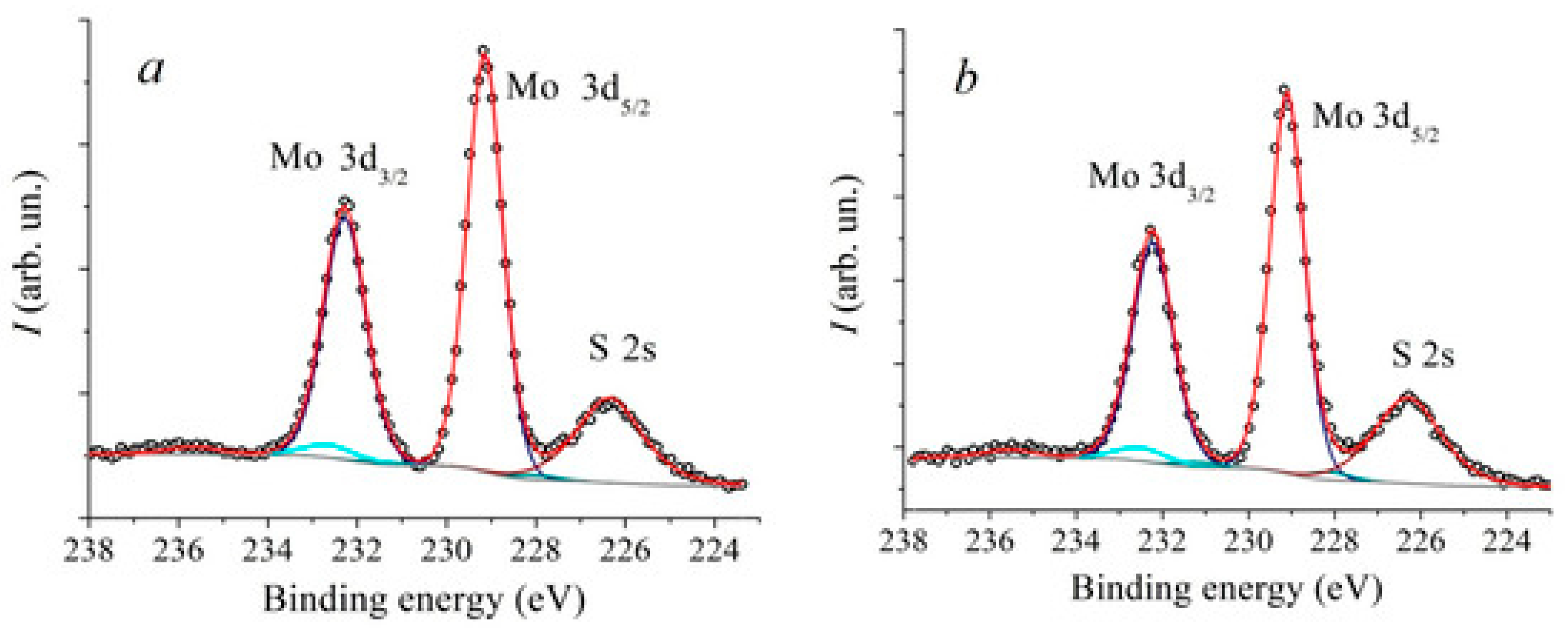

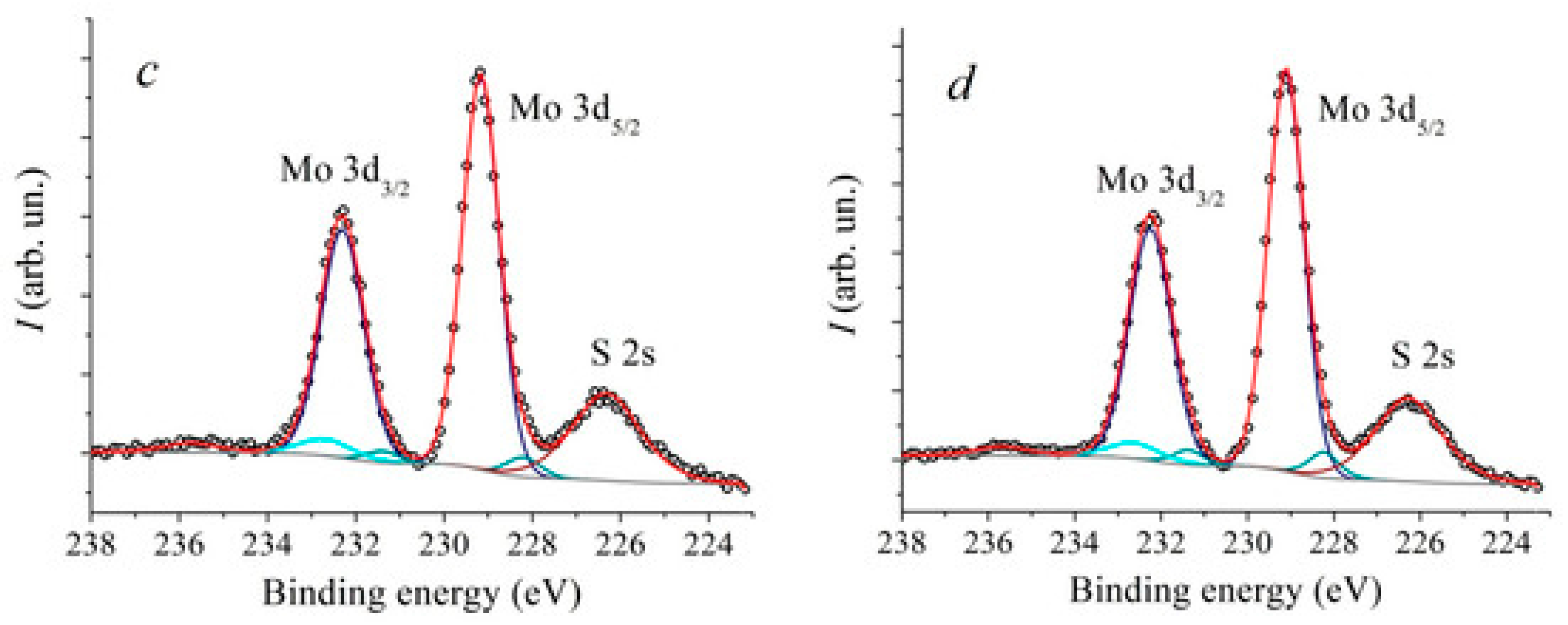

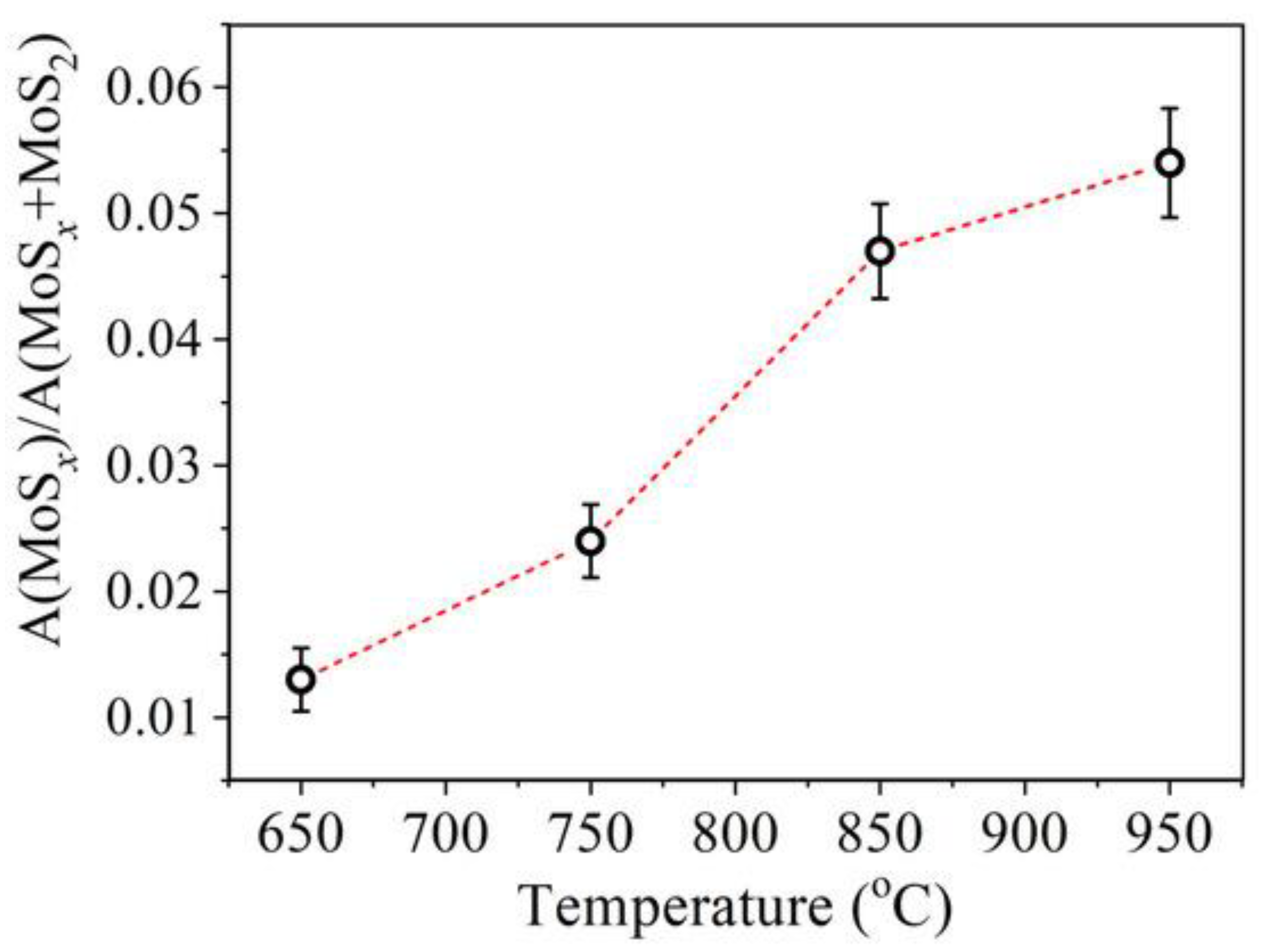

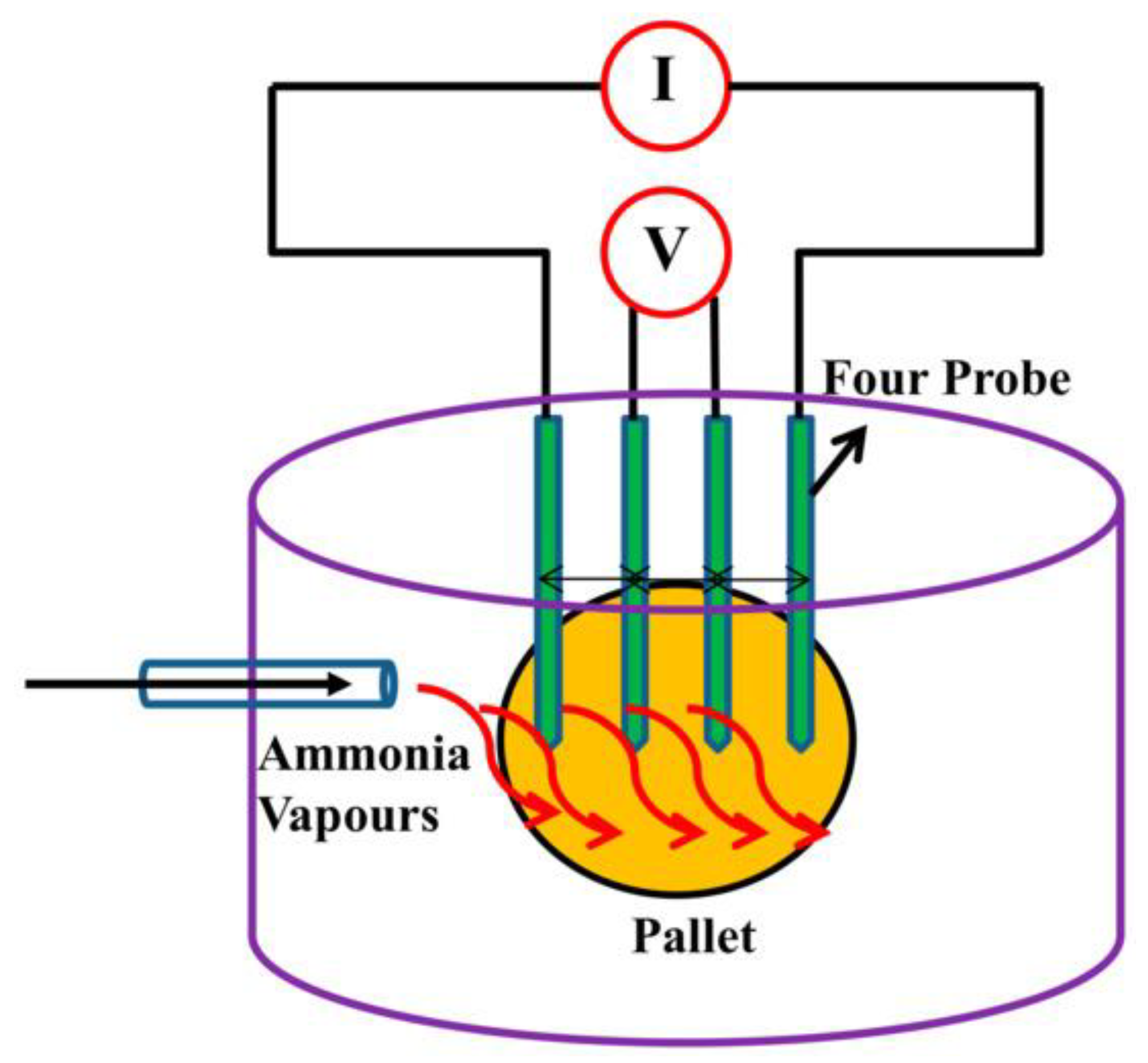

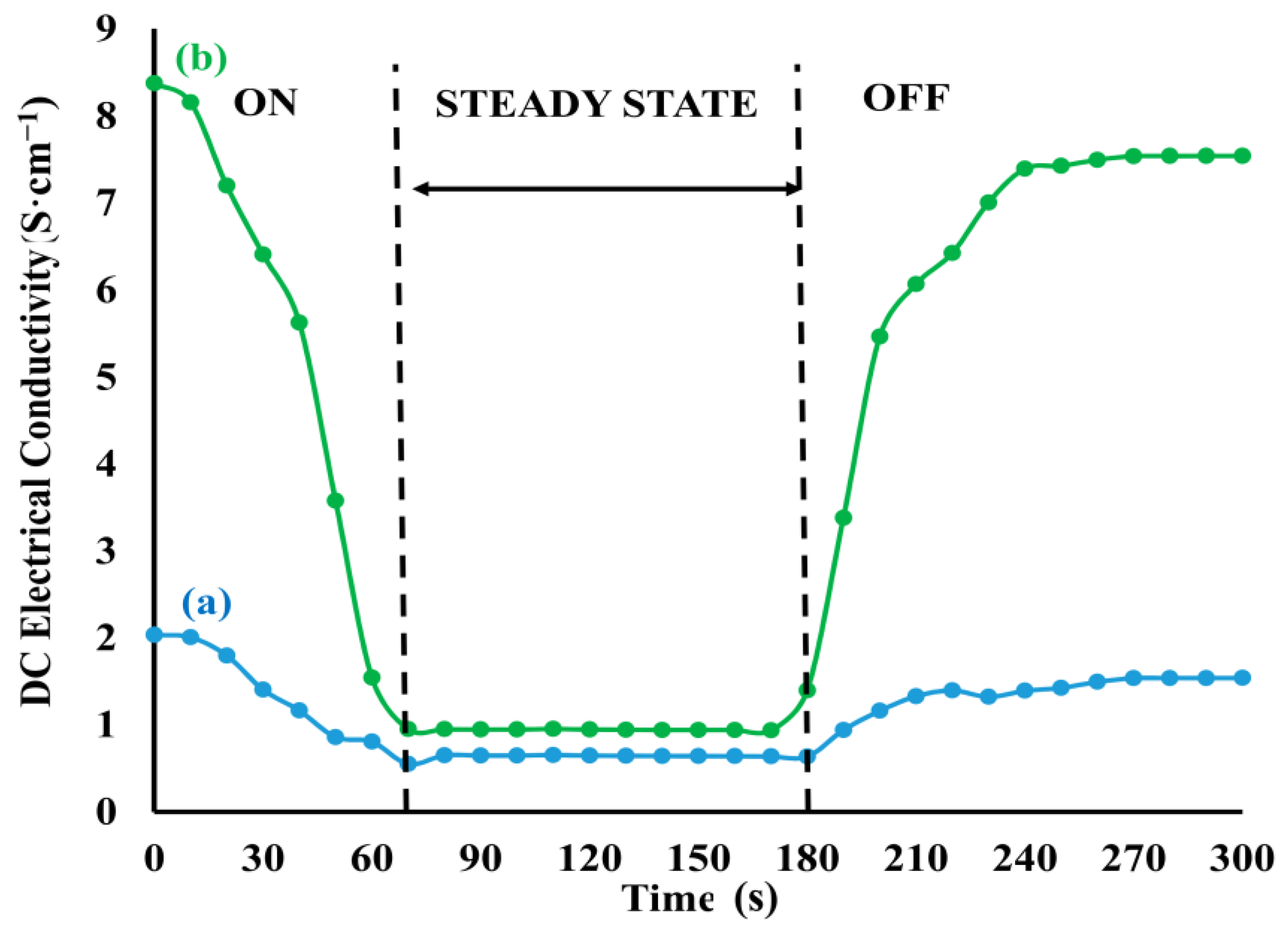

5. XPS Investigation of Defect States, Oxidation, and Interfacial Chemistry in MoS2 Heterostructure

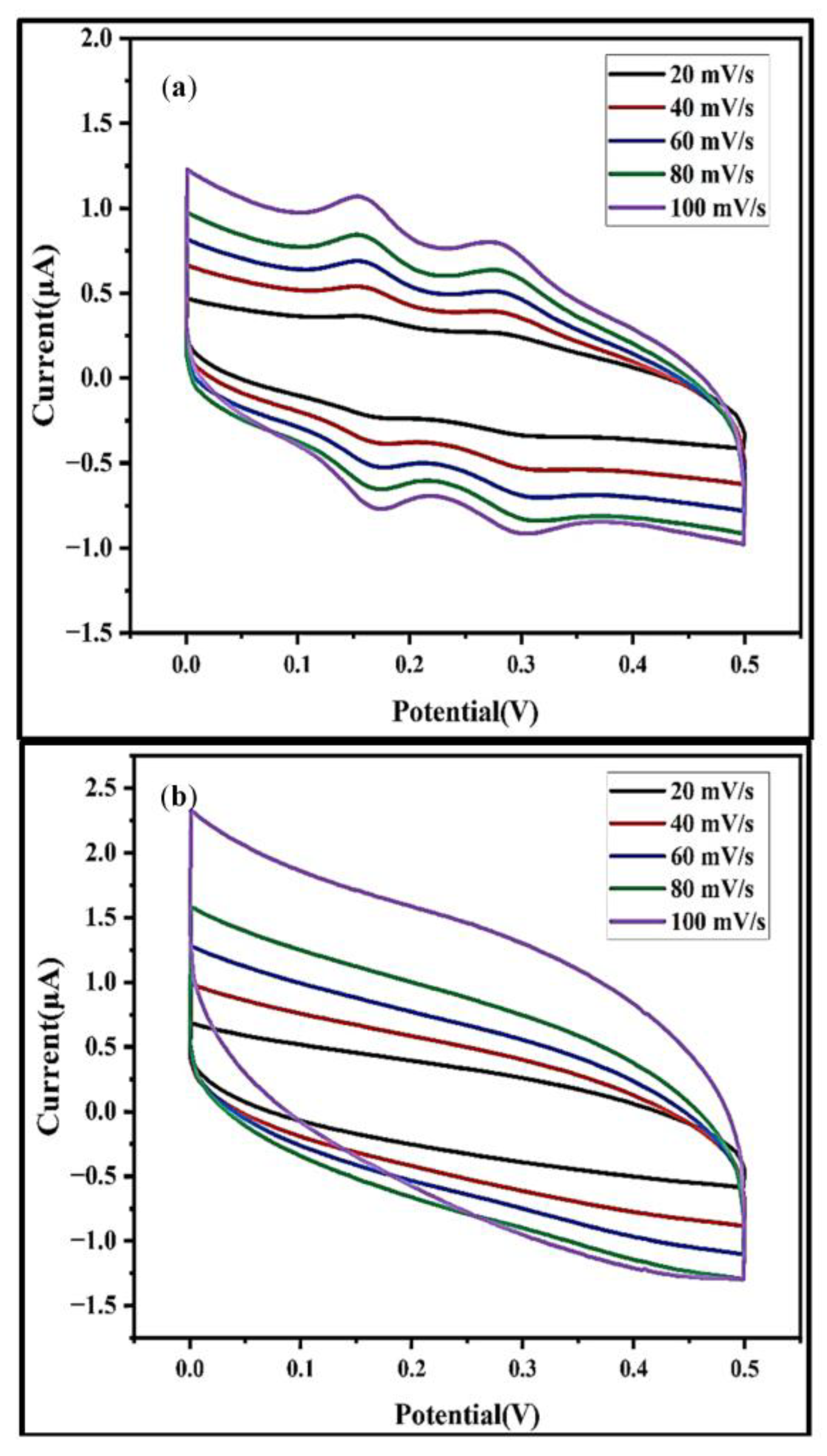

6. Investigation of DC Conductivity, Gas Sensing, and Electrochemical Behavior of MoS2 Nanocomposites

7. Challenges and Future Directions

- Managing Structural Imperfections and Layer Consistency.

- Scaling Up and Ensuring Consistency in Deposition Techniques.

- Optimizing Interfaces and Adhesion.

- Ensuring Durability in Various Environments and Operating Conditions.

- Integrating Analysis and Data-Driven Refinement.

- Tailoring Designs for Specific Applications and Identifying Niche Uses.

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- Synthesis method and associated growth conditions;

- (2)

- Defect chemistry and stoichiometric deviations;

- (3)

- Environmental stability during storage and operation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chong, K.; Zou, Y.; Wu, D.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Pulsed Laser Re-Melting Supersonic Plasma Sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr Coatings for Regulating Microstructure, Hardness, and Corrosion Properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 418, 127258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, X.L.; Fu, H.G.; Sun, S.T.; Lin, J.; Guo, X.Y.; Lei, Y.P. Microstructure and Performance of Nb-Bearing Ni60A-Cr3C2 Coatings Manufactured by Laser Cladding. Surf. Eng. 2020, 36, 1294–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghimeresht, E.; Markocsan, N.; Nylen, P. Microstructural Characteristics and Corrosion Behavior of HVAF-and HVOF-Sprayed Fe-Based Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 318, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Pan, H.; Yuan, C.; Chen, X. Research on Remanufacturing Strategy for 45 Steel Gear Using H13 Steel Powder Based on Laser Cladding Technology. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 49, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, J.; Grewal, J.S.; Gupta, P. Analysis of D-gun Sprayed Coating on Medium Carbon Steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 21, 1403–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanchenko, O.; Porkuian, O.; Kharlamov, Y.; Sokolov, V.; Krol, O. Research of Features of Oxide Coatings Deposition by D-gun Spraying. In Innovations in Mechanical Engineering II, Proceedings of the International Conference Innovation in Engineering, Minho, Portugal, 28–30 June 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhai, H.; Li, W.; Cui, S.; Ning, W.; Qiu, X. Dry Sliding Wear Behaviors of Fe-Based Amorphous Metallic Coating Synthesized by D-gun Spray. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2020, 537, 120018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallad, S.A.; Banapurmath, N.R.; Hunashyal, A.M.; Shettar, A.S. Study of the Effect of Nanocomposite Thin Film Coating on Cutting Tool Tip for Tribological Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzi, M.; Mousavi Anijdan, S.H.; Asadian, M. The Effect of Substrate Temperature on Microstructural Evolution and Hardenability of Tungsten Carbide Coating in Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2018, 15, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Mariano, J.; Lau, K.H.; Alvarez, E.; Malhotra, R. Coatings for Corrosion Protection of Porous Substrates in Gasifier Components. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 202, 2794–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfini, A.; Vricella, A.; Bueno Morles, R.; Pastore, R.; Micheli, D.; Gugliermetti, F.; Marchetti, M. CVD Nano-Coating of Carbon Composites for Space Materials Atomic Oxygen Shielding. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2017, 3, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Sun, W. Microstructure and Growth Behavior of HfC Ceramic Coating Synthesized by Low Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 705, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Anijdan, S.H.; Sabzi, M.; Asadian, M.; Jafarian, H.R. Effect of Sub-Layer Temperature during HFCVD Process on Morphology and Corrosion Behavior of Tungsten Carbide Coating. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2019, 16, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, H.W.; Chromik, R.R.; Hassani, S.; Klemberg-Sapieha, J.E. In Situ Tribology of Nanocomposite Ti-Si-C-H Coatings Prepared by PE-CVD. Wear 2011, 272, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ji, H.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. Reconfiguring Nucleation for CVD Growth of Twisted Bilayer MoS2 with a Wide Range of Twist Angles. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stueber, M.; Albers, U.; Leiste, H.; Ulrich, S.; Holleck, H.; Barna, P.B.; Kovacs, A.; Hovsepian, P.; Gee, I. Multifunctional Nanolaminated PVD Coatings in the System Ti-Al-N-C by Combination of Metastable fcc Phases and Nanocomposite Microstructures. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006, 200, 6162–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilarasan, T.R.; Rajendran, R.; Rajagopal, G.; Sudagar, J. Effect of Surfactants on the Coating Properties and Corrosion Behaviour of Ni-P-Nano-TiO2 Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 276, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzi, M.; Mersagh Dezfuli, S. Deposition of Al2O3 Ceramic Film on Copper-Based Heterostructured Coatings by Aluminizing Process: Study of the Electrochemical Responses and Corrosion Mechanism of the Coating. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2019, 16, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cho, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jan, A.; Wong, K.T.; Nemani, S.D.; Yieh, E.; Kummel, A.C. Selective Pulsed Chemical Vapor Deposition of Water-Free TiO2/Al2O3 and HfO2/Al2O3 Nanolaminates on Si and SiO2 in Preference to SiCOH. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 15471–15481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafailov, P.; Mehandzhiev, V.; Sveshtarov, P.; Blagoev, B.; Terziyska, P.; Avramova, I.; Kirilov, K.; Ranguelov, B.; Avdeev, G.; Petrov, S.; et al. Atomic Layer Deposition Growth and Characterization of Al2O3 Layers on Cu-Supported CVD Graphene. Coatings 2024, 14, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Ito, A. High-Light-Yield and Fast-Response β-Ga2O3-Al2O3 Thick-Film Scintillators Epitaxially Grown via Chemical Vapor Deposition. Mater. Lett. 2024, 365, 136721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, P.; Ghasemi, R.; Torabi, S.; Mirjani, B.; Memari, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Khaledi, H. Characterization and High-Temperature Fretting Wear Resistance of HVOF-Sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr, CoCrWC and CoCrWNiC Hardfacing Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2022, 31, 2157–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Hussain, T.; McCartney, D.G. High-Temperature Oxidation of HVOF Thermally Sprayed NiCr-Cr3C2 Coatings: Microstructure and Kinetics. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 6808–6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, L.M. Application of Hardmetals as Thermal Spray Coatings. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 49, 350–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, D. Structural Characteristics and Wear, Oxidation, Hot Corrosion Behaviors of HVOF Sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr Hardmetal Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 457, 129319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, F.; Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; Deng, W.; An, B.; Chu, F.; Zhang, G.; Li, S.; et al. Enhanced Performance of a CVD MoS2 Photodetector by Chemical in Situ n-Type Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11234–11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, J.; Tan, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhong, Z. Combined Post-Treatment Approach for Improving the Surface Integrity of CVD α-Al2O3 Coating and the Tool Wear Resistance. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 39488–39498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.; Barry, S.T.; Sundqvist, J. Green CVD—Toward a Sustainable Philosophy for Thin Film Deposition by Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2021, 39, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, N.E.; De Paula, C.; Bent, S.F. Understanding Chemical and Physical Mechanisms in Atomic Layer Deposition. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 040902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Hernández, M.Á.; Cano-Díaz, G.S.; Vivaldo-Lima, E.; Rosas-Aburto, A.; Hernández-Luna, M.G.; Martinez, A.; Palacios-Alquisira, J.; Mohammadi, Y.; Penlidis, A. A Review on the Synthesis, Characterization, and Modeling of Polymer Grafting. Processes 2021, 9, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón, S.; Rodríguez-González, V. Photocatalytic TiO2 Thin Films and Coatings Prepared by Sol-Gel Processing: A Brief Review. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2022, 102, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq Ur Rehman, M.; Chen, Q.; Braem, A.; Shaffer, M.S.; Boccaccini, A.R. Electrophoretic Deposition of Carbon Nanotubes: Recent Progress and Remaining Challenges. Int. Mater. Rev. 2021, 66, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichou, H.; Arrousse, N.; Berdimurodov, E.; Aliev, N. Exploring the Advancements in Physical Vapor Deposition Coating: A Review. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 2024, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ren, G.-K.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Shi, Y. Facilitating Complex Thin Film Deposition by Using Magnetron Sputtering: A Review. JOM 2022, 74, 3069–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Sankapal, S.R.; Almuntaser, F.M.A. Dip Coating: Simple Way of Coating Thin Films. In Simple Chemical Methods for Thin Film Deposition; Sankapal, B.R., Ennaoui, A., Gupta, R.B., Lokhande, C.D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; El-Demellawi, J.K.; Kim, H.; Alshareef, H.N. MXene Printing and Patterned Coating for Device Applications. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukong, V.T.; Ukoba, K.; Jen, T.C. Review of Self-Cleaning TiO2 Thin Films Deposited with Spin Coating. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 3525–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, A.; Basha, G.M.T.; Venkateshwarlu, B. A Brief Review on Cold Spray Coating Process. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 22, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machkih, K.; Oubaki, R.; Makha, M. A Review of CIGS Thin Film Semiconductor Deposition via Sputtering and Thermal Evaporation for Solar Cell Applications. Coatings 2024, 14, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, D.; Sharif, R.; Nasir, R.; Awad, A.; Mannan, H.A. A Review on Coatings through Thermal Spraying. Chem. Pap. 2024, 78, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.; Adhikari, S. Use of Biomaterials for 3D Printing by Fused Deposition Modeling Technique: A Review. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, P.; An, H.; Peng, P.; McLean, B.; Ding, F. Achievements and Challenges of Graphene Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabongo, G.L.; Mothudi, B.M.; Dhlamini, M.S. Advanced Development of Sustainable PECVD Semitransparent Photovoltaics: A Review. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 762030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhou, T.; Ma, W.; Xu, C.; Ren, W. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Layered Two-Dimensional MoSi2N4 Materials. Science 2020, 369, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bute, A.; Jena, S.; Kedia, S.; Udupa, D.V.; Singh, K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Sinha, S. Boron Carbide Thin Films Deposited by RF-PECVD and PLD Technique: A Comparative Study Based on Structure, Optical Properties, and Residual Stress. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 258, 123860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.M.; Ehsan, M.A.; Suleiman, R.K.; Hakeem, A.S. Fabrication and Characterization of Nanostructured AACVD Thin Films on 316L SS as Surface Protective Layers in Simulated Body Fluid. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 4301–4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Trainor, N.; McKnight, T.V.; Graves, A.R.; Wu, Z.; Xu, L.; Redwing, J.M. Metal-Organic Chemical Vapour Deposition for 2D Chalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2025, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, K.K. Designing Organic and Hybrid Surfaces and Devices with Initiated Chemical Vapor Deposition (iCVD). Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2306665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Diaz, P.J.; Esqueda-Barrón, Y.; Baas-López, J.M.; Cuentas-Gallegos, A.K.; Pacheco-Catalán, D.E. Synthesis of Manganese Oxide Thin Films Deposited on Different Substrates via Atmospheric Pressure-CVD. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 494, 131440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversa, A.; Marchese, G.; Bassini, E. Directed Energy Deposition of AISI 316L Stainless Steel Powder: Effect of Process Parameters. Metals 2021, 11, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahighi, R.; Panahi, M.; Akhavan, O.; Mansoorianfar, M. Pressure-Engineered Electrophoretic Deposition for Gentamicin Loading within Osteoblast-Specific Cellulose Nanofiber Scaffolds. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 272, 125018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Xiang, G. Mn-Doped SiGe Thin Films Grown by UHV/CVD with Room-Temperature Ferromagnetism and High Hole Mobility. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 2826–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, A.S.; Alexandrov, S.E. A Study of the Influence of Process Parameters of AP PECVD on the Mechanical Properties of Silica-Like Films Deposited on Polycarbonate. Silicon 2025, 17, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.L.A.; Centurion, H.A.; Torres, J.A.; Gonçalves, R.V.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Riberio, C.; Nogueira, F.G. Enhancing Nb2O5 Activity for CO2 Photoreduction through Cu Nanoparticles Cocatalyst Deposited by DC-Magnetron Sputtering. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 53, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiford, J.A.; Oyakhire, S.T.; Bent, S.F. Applications of Atomic Layer Deposition and Chemical Vapor Deposition for Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 1997–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plujat, B.; Glénat, H.; Bousquet, A.; Frézet, L.; Hamon, J.; Goullet, A.; Thomas, L. SiCN:H Thin Films Deposited by MW-PECVD with Liquid Organosilicon Precursor: Gas Ratio Influence versus Properties of the Deposits. Plasma Process. Polym. 2020, 17, 1900138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wu, W.; Wei, F.; Chen, Q. Three Elements for the Preparation of Vertical Graphene by RF-PECVD Method. FlatChem 2021, 30, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ru, X.; Ruan, T.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H. Performance of Heterojunction Solar Cells with Different Intrinsic a-Si:H Thin Layers Deposited by RF- and VHF-PECVD. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 25327–25331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlanuly, Y.; Christy, D.; Van Nong, N.; Kondo, H.; Alpysbayeva, B.; Nemkayeva, R.; Hori, M. Synthesis of Carbon Nanowalls on the Surface of Nanoporous Alumina Membranes by RI-PECVD Method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 523, 146533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassim, S.; Abbas, A.; Al-Shakban, M.; Ahmed, L. Chemical Vapour Deposition of CdS Thin Films at Low Temperatures from Cadmium Ethyl Xanthate. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 2533–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B. Corrosion Resistance of Non-Stoichiometric Gadolinium Zirconate Fabricated by Laser-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cheng, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Ma, J.; Yao, Y.; Hao, Y. Investigation of the Surface Optimization of β-Ga2O3 Films Assisted Deposition by Pulsed MOCVD. Scr. Mater. 2022, 213, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Kuang, T.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Y.; Lin, S.; Wang, L. Effect of Pretreatment Strategy on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Cutting Performance of Diamond Coated Hardmetal Tools Using HFCVD Method. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2021, 101, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari Gharahcheshmeh, M. Fabrication of Conjugated Conducting Polymers by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Method. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Sato, K.; Kawahara, K. Gas Permeation Property of Silicon Carbide Membranes Synthesized by Counter-Diffusion Chemical Vapor Deposition. Membranes 2020, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.W.; Gleason, K.K.; Yang, R. Advanced Morphological Control of Polymeric Surfaces Using Initiated Chemical Vapor Deposition (iCVD). Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2417620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Li, B.; Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Li, D. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Si3N4f/BN Composites with BN Interphase Prepared by Chemical Vapor Deposition of Borazine. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katamune, Y.; Arikaw, D.; Mori, D.; Izumi, A. Formation of Phosphorus-Incorporated Diamond Films by Hot-Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition Using Organic Phosphorus Solutions. Thin Solid Film. 2019, 677, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzi, M.; Mousavi Anijdan, S.H.; Shamsodin, M.; Farzam, M.; Hojjati-Najafabadi, A.; Feng, P.; Park, N.; Lee, U. A Review on Sustainable Manufacturing of Ceramic-Based Thin Films by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): Reactions Kinetics and the Deposition Mechanisms. Coatings 2023, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Afzaal, M.; Helliwell, M.; Malik, M.A.; O’Brien, P.; Raftery, J. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Indium Selenide and Gallium Selenide Thin Films from Mixed Alkyl/Dialkylselenophosphorylamides. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 4205–4210. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/cm0310420 (accessed on 12 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Konar, R.; Nessim, G.D. A Mini-Review Focusing on Ambient-Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition (AP-CVD) Based Synthesis of Layered Transition Metal Selenides for Energy Storage Applications. Mater. Adv. 2022, 3, 4471–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.; Acharya, S.; Golden, A.; Yang, E.; Stanchu, H.; Chang, G.-E.; Sun, G.; Du, W.; Yu, S.-Q. In-Situ Real-Time Monitoring of GeSn Growth Using UHV-CVD to Achieve High-Quality Material with Lasing at 2250 nm and 100 K. Opt. Mater. Express 2025, 15, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, J. Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications; Hussain, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, A.H.; Mishra, A.K.; Gallucci, F.; Kim, J.H.; Ulbricht, M.; Coclite, A.M.; Hosseini, S.S. Advances in Surface Modification and Functionalization for Tailoring the Characteristics of Thin Films and Membranes via Chemical Vapor Deposition Techniques. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongrom, S.; Tirawanichakul, Y.; Munsit, N.; Deangngam, C. One-Step Microwave Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (MW-PECVD) for Transparent Superhydrophobic Surface. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 311, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, F.; Wu, G.; Kovalenko, V.S.; Yao, J. Research Progress of Laser-Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition. Opto-Electron. Eng. 2022, 49, 210333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, N.S.; Kotbi, A.; Kaja, K.; Jouiad, M. Long-Term Aging of CVD Grown 2D-MoS2 Nanosheets in Ambient Environment. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deokar, G.; Rajput, N.S.; Li, J.; Deepak, F.L.; Ou-Yang, W.; Reckinger, N.; Bittencourt, C.; Colomer, J.-F.; Jouiad, M. Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of Graphene on 3C-SiC/Si Substrates. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Qiu, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, H.; Wu, S.; Jia, D.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, P. Controlled Growth of Six-Point Stars MoS2 by Chemical Vapor Deposition and Its Shape Evolution Mechanism. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 395601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Rong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Pacios, M.; Bhaskaran, H.; He, K.; Warner, J.H. Shape Evolution of Monolayer MoS2 Crystals Grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 6371–6379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Shim, G.W.; Seo, S.-B.; Choi, S.-Y. Effective Shape-Controlled Growth of Monolayer MoS2 Flakes by Powder-Based Chemical Vapor Deposition. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, J.; Srinivasan, B.M.; Zhang, G.; Yang, M.; Chai, J.; Wang, S.; Chi, D.; Zhang, Y.-W. Revealing the Grain Boundary Formation Mechanism and Kinetics during Polycrystalline MoS2 Growth. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 46090–46100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şar, H.; Özden, A.; Demiroğlu, İ.; Sevik, C.; Perkgoz, N.K.; Ay, F. Long-Term Stability Control of CVD-Grown Monolayer MoS2. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2019, 13, 1800687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernardou, D. Special Issue: Advances in Chemical Vapor Deposition. Materials 2020, 13, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanai, G.S.; Pal, S.; Pal, P.; Yadav, B.S.; Garg, P.; Gupta, S.; Ansari, S.; Gupta, B.K. New Insight into the Growth of Monolayer MoS2 Flakes Using an Indigenously Developed CVD Setup: A Study on Shape Evolution and Spectroscopy. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 5429–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Nguyen, V.H.; Riaz, M.; Nasir, N.; Kumar, S.; Park, H.M.; Jung, J.; Seo, Y. NaCl-Assisted Temperature-Dependent Controllable Growth of Large-Area MoS2 Crystals Using Confined-Space CVD. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 30074–30086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Lu, J.; Yang, P. Substrate Effects on the CVD Growth of MoS2 and WS2. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Shenoy, V.B.; Tang, M.; Lou, J. Towards Controlled Synthesis of 2D Crystals by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). Mater. Today 2020, 40, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkić, A.; Bajo, J.; Supina, A.; Radatović, B.; Vujičić, N. Effects of CVD Growth Parameters on Global and Local Optical Properties of MoS2 Monolayers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.03498. [Google Scholar]

- Arnault, J.C.; Saada, S.; Ralchenko, V. Chemical Vapor Deposition Single-Crystal Diamond: A Review. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 2022, 16, 2100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, A.; Fuchtbauer, H.G.; Tuxen, A.K.; Walton, A.S.; Andersen, M.; Porsgaard, S.; Besenbacher, F.; Hammer, B.; Lauritsen, J.V. In Situ Detection of Active Edge Sites in Single-Layer MoS2 Catalysts. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9322–9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.A.; Gilmore, R.; Lenardi, C.; Gissler, W. XPS Investigation of Preferential Sputtering of S from MoS2 and Determination of MoSx Stoichiometry from Mo and S Peak Positions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1999, 150, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lim, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sarkar, S.; Ramsden, H.; Li, Y.; Yan, H.; Phuyal, D.; Gauriot, N. Room-Temperature Photoluminescence Mediated by Sulfur Vacancies in 2D Molybdenum Disulfide. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 13545–13553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H. Theoretical Photoionization Cross Sections from 1 to 1500 keV; UCRL-51326; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: Livermore, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, M.; Lu, S. Light-Stimulated Low-Power Artificial Synapse Based on a Single GaN Nanowire for Neuromorphic Computing. Photonics Res. 2023, 11, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Sangwan, V.K.; Jariwala, D.; Wood, J.D.; Park, S.; Chen, K.-S.; Shi, F.; Ruiz-Zepeda, F.; Ponce, A.; Jose-Yacaman, M. Vliyanie Stekhiometrii na Opticheskie i Elektricheskie Svoystva MoS2, Poluchennogo Metodom CVD. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10551–10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata Subbaiah, Y.P.; Saji, K.J.; Tiwari, A. Atomically Thin MoS2: A Versatile Nongraphene 2D Material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 2046–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyarati, A.; Kumar, A.; El Yumin, A.A.; Rudolf, P. Photoemission Spectroscopic Study of Structural Defects in MoS2 Grown by Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 10384–10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, C.; Song, J. Study on the Catalyst Effect of NaCl on MoS2 Growth in a Chemical Vapor Deposition Process. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 5337–5344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Moun, M.; Sharma, M.; Barman, A.; Kapoor, A.K.; Singh, R. Substrate-Dependent 2D Nucleation Growth of MoS2 Assisted by NaCl. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 538, 148201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yan, H.; Brus, L.E.; Heinz, T.F.; Hone, J.; Ryu, S. Anomalous Lattice Vibrations of Single- and Few-Layer MoS2. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.K.; Dhar, S.; Choudhury, T.H.; Shivashankar, S.A.; Raghavan, S. A Predictive Approach to CVD of Crystalline Layers of TMDs: The Case of MoS2. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 7802–7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greben, K.; Arora, S.; Harats, M.G.; Bolotin, K.I. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Defect-Related Excitons in TMDCs. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 2544–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, N.B.; Francis, B.; Rao, M.S.R.; Ryu, B.D.; Chandramohan, S.; Eswaran, S.K. Rapid Wafer-Scale Fabrication with Layer-by-Layer Thickness Control of Atomically Thin MoS2 Films Using Gas-Phase Chemical Vapor Deposition. APL Mater. 2019, 7, 081113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalanyan, B.; Kimes, W.A.; Beams, R.; Stranick, S.J.; Garratt, E.; Kalish, I.; Davydov, A.V.; Kanjolia, R.K.; Maslar, J.E. Rapid Wafer-Scale Growth of Polycrystalline 2H-MoS2 by Pulsed Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 6279–6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, J.; Kalaiezhily, R.K.; Shinde, N.; Bharathi, K. In Situ X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study: Effect of Inert Ar Sputter Etching on the Core-Level Spectra of the CVD-Grown Tri-Layer MoS2 Thin Films. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 15956–15966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan, I.; Husain, A.; Khan, A.; Asiri, A.M. Electrical Conductivity Based Ammonia Sensing Properties of Polypyrrole/ MoS2 Nanocomposite. Polymers 2020, 12, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Byon, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Molybdenum Disulfide Nanoflowers and Nanosheets. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 710462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olichwer, N.; Leib, E.W.; Halfar, A.H.; Petrov, A.; Vossmeyer, T. Cross-Linked Gold Nanoparticles on Polyethylene: Resistive Responses to Tensile Strain and Vapors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 6151–6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, G.; Yamaguchi, H.; Voiry, D.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Chhowalla, M. Photoluminescence from Chemically Exfoliated MoS2. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.-P.; Chen, S.; Deng, H.; Scanlon, M.D.; Gumy, F.; Lee, H.J.; Momotenko, D.; Amstutz, V.; Cortés-Salazar, F.; Pereira, C.M.; et al. Conductive Gold Nanoparticle Mirrors at Liquid/Liquid Interfaces. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9241–9248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yuan, K.; Huang, F. Effect of Vanadium Doping on the Thermoelectric Properties of MoS2. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 903, 163921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiselvi, T.; Praveena, C.; Sridevi, V.; Venmathi Maran, B.A.; Kimura, M. Synergistic Effect in MoS2 Nanosheets-Biochar Nanocomposites with Enhanced Surface Area and Electrical Conductivity for Energy Storage Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B.; Ruoff, R.S. Chemical Vapor Deposition of Graphene on Thin-Metal Films. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Kruse, P. Conductive Forms of MoS2 and Their Applications in Energy Storage and Conversion. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 126517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; He, H.; Song, Q.; Wang, B.; Lv, W.; Yang, Q.-H.; Zhi, L. Rational Design of MoS2 Graphene Nanocables: Towards High Performance Electrode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Wei, Y.; Chen, J.; Long, D.; Ling, L.; Li, Y.; Shi, J. Melamine-Assisted One-Pot Synthesis of Hierarchical Nitrogen-Doped Carbon@MoS2 Nanowalled Core-Shell Microspheres and Their Enhanced Li-Storage Performances. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindumadhavan, K.; Srivastava, S.K.; Mahanty, S. MoS2-MWCNT Hybrids as a Superior Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, H.; Ma, J. Growth of MoS2@C Nanobowls as a Lithium-Ion Battery Anode Material. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 92506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Dong, D.; Wen, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z. Microwave Synthesized Self-Standing Electrode of MoS2 Nanosheets Assembled on Graphene Foam for High-Performance Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 660, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yu, K.; Song, H.; Li, H.; Tan, Y.; Fu, H.; Li, C.; Lei, X.; Zhu, Z. Preparation of Hollow Microsphere Onion-like Solid Nanosphere MoS2 Coated by a Carbon Shell as a Stable Anode for Optimized Lithium Storage. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wan, W.; Huang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, H.H.; Zhang, X.X. Hierarchical MoS2 Nanosheet/Active Carbon Fiber Cloth as a Binder-Free and Free-Standing Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingappan, N.; Van, N.H.; Lee, S.; Kang, D.J. Growth of Three-Dimensional Flower-like MoS2 Hierarchical Structures on Graphene/Carbon Nanotube Network: An Advanced Heterostructure for Energy Storage Devices. J. Power Sources 2015, 280, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tan, J.; Nong, H.; Liu, B.; Cheng, H.-M. Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of Two-Dimensional Compound Materials: Controllability, Material Quality, and Growth Mechanism. Acc. Mater. Res. 2020, 2, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, Z.; Huo, J.; Ma, Z.; Dou, S.; Wang, S. SiO2-Directed Surface Control of Hierarchical MoS2 Microspheres for Stable Lithium-Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 74012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhan, X.; Zhu, W.; Qi, S.; Braun, P.V. Carbon-Free, High-Capacity and Long Cycle Life 1D-2D NiMoO4 Nanowires/Metallic 1T-MoS2 Composite Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 44593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, T.; Fang, Q.; Xie, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, S.; Khalil, A.; Tao, S. Vertical 1T-MoS2 Nanosheets with Expanded Interlayer Spacing Edged on a Graphene Frame for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Ma, Y.; Yang, L.; Hafez, A.M.; Zhu, H. Ion Transport Nanotube Assembled with Vertically Aligned Metallic MoS2 for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1702779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, N.B.; Ryu, B.D.; Meganathan, K.; Francis, B.; Hong, C.-H.; Chandramohan, S.; Eswaran, S.K. Large-Scale Atomically Thin Monolayer 2H-MoS2 Field-Effect Transistors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 7898–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yap, C.C.R.; Tay, B.K.; Edwin, T.H.T.; Olivier, A.; Baillargeat, D. From Bulk to Monolayer MoS2: Evolution of Raman Scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Modification Techniques | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

| CVD | Gas-phase deposition using precursors and reactants | Deposition of CNTs, oxides, anticorrosion coatings | High uniformity, good adhesion, high deposition rate | High temperatures, toxic precursors, high cost | [28] |

| ALD | Sequential precursor delivery, reaction occurs only on the surface | Nanostructures, membranes, electronics | Atomic-level thickness control, excellent uniformity and conformality | Slow process, expensive and highly reactive precursors | [29] |

| Grafting | Chemical attachment of functional groups or monomers to the surface | Polymer membranes, improved hydrophilicity | Introduction of new functionalities, high selectivity | Only applicable to functional polymers, scale-up difficulty, high cost | [30] |

| Sol–gel | Conversion of precursor solutions (metal alkoxides) into oxide films | Photocatalysis, filtration, TiO2 membranes | Simplicity, porosity control, potential for nanostructuring | Possible cracking during drying, sometimes low stability, long process | [31] |

| Physical Modification Techniques | |||||

| Method | Key Features | Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

| EPD | Deposition of charged particles on an electrode under an electric field | Ceramic coatings, membranes | Fast deposition, uniformity, thickness control | Requires conductive substrate, limited materials | [32] |

| PVD (Physical Vapor Deposition) | Vapor-phase reactions at high temperature | CNTs, oxides, anticorrosion coatings | Uniformity, high adhesion, fast deposition rate | High temperature, toxic precursors, high cost | [33] |

| Sputtering | Deposition of Ar+ ions from a target onto a substrate (PVD) | Thin films, electronics | Versatility, low temperature, no precursors | Low deposition rate, expensive equipment, sometimes poor adhesion | [34] |

| Dip coating | Immersion of substrate into solution followed by solvent evaporation | Polymer membranes, LbL assembly | Simplicity, reproducibility, multilayer capability | Non-uniform coating, low quality, dependent on conditions | [35] |

| Meyer rod coating | Deposition using a rod (doctor blade) | Gas separation membranes, MMM | Thickness control (100 nm–10 μm), high reproducibility | Requires viscosity optimization, defects at low viscosity | [36] |

| Spin coating | Uniform spreading of solution by spinning | GO, PDMS membranes | Simplicity, low cost, high uniformity | Only for small samples, not scalable | [37] |

| Spray coating | Suspension spraying under pressure | Ceramic and polymer membranes | Simplicity, minimizes pore penetration, no intermediate layer | Lower permeability, requires viscosity control | [38] |

| Thermal evaporation | Evaporation of material in vacuum and deposition onto substrate | Metals, organic coatings | Simplicity, cheaper than PVD | Difficult for membranes, limited adhesion, non-uniform on complex shapes | [39] |

| Thermal spraying | Spraying molten particles (plasma, HVOF, etc.) | Anticorrosion coatings, mechanical protection | High deposition rate, coating strength | High porosity, low adhesion, requires powerful energy sources | [40] |

| Blending | Mixing functional polymers and nanoparticles with a matrix | UF/MF membranes, composites | Simplicity, improves hydrophilicity, mechanical strength, antifouling | Affects bulk, not just surface; compatibility issues | [41] |

| Method | Conditions/Features | Applications | Materials/Examples | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP-CVD | ~1 atm, high deposition rate | Graphene devices, turbine blades, electronics | Graphene zeolite Al2O3 SiO2 | [49] |

| LP-CVD | Reduced pressure, heating without carrier gas | Uniform coatings, membranes, semiconductors | SLG SiC Al2O3 MoS2 | [50] |

| HP-CVD | Pressure > 1 atm | Smooth layers, H2-selective membranes | SiO2 TMOS | [51] |

| UHV-CVD | Extremely low pressure, low T | Epitaxial growth of Si, SiGe | Si SiGe | [52] |

| AP-PECVD | Atmospheric pressure, no vacuum | Low-cost coatings, large samples | Polymer layers | [53] |

| DC-PECVD | Direct current plasma | Carbon coatings, fuel cells | a-C:H, steel | [54] |

| iPE-CVD | Initiator at low power | Polymer films, functional coatings | PNIPAAm, PHEMA | [55] |

| MW-PECVD | Microwave plasma, high power | Barrier layers, superhydrophobic coatings | SiNx:H, PDMS | [56] |

| RF-PECVD | Plasma at 13.56 MHz | DLC films, PVDF modification | DLC, PET, PVDF | [57] |

| VHF-PECVD | Frequency > RF, high deposition rate | Gas-impermeable coatings, solar cells | SiNx, Si | [58] |

| RI-PECVD | Radical injection (H) | Carbon nanowalls | CNWs Al2O3 | [59] |

| AA-CVD | Aerosol precursors, ~1 atm | Use of non-volatile precursors | Oxides, metals | [60] |

| LCVD | Laser heating, high rate | Local coatings, mask repair | Re, Au, Pt | [61] |

| MOCVD | Metal–organic precursors, low T | Electronics, corrosion resistance | SnOx:F Cu MoS2 Ag | [62] |

| HFCVD | Hot filament (2000 °C), H2 + hydrocarbons | Diamond and carbon coatings | Diamond nanoparticles | [63] |

| OCVD | Monomer oxidation | Conductive polymers, sensors | PEDOT PANI, etc. | [64] |

| CDCVD | Diffusion of precursor and oxidizer toward each other | Silica membrane synthesis | SiO2 MoS2 | [65] |

| iCVD | Radical polymerization at low T | Functional coatings on polymers | Polymer membranes | [66] |

| Structure | Electrode Materials | Fabrication Methods | Capacity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocable webs | MoS2 + Graphene | Unique side to face contact mode | 1150 mA h g−1 | [114] |

| Core–shell microsphere | MoS2 + N-doped carbon | One pot hydrothermal synthesis | 856 mA h g−1 | [115] |

| Nanobundle | MoS2 + MWCNT | Dry grinding process using a mortar and pestle | 1214 mA h g−1 | [116] |

| Nanobowl | MoS2 + C | Solvothermal synthesis | 1164.4 mA h g−1 | [117] |

| Flowerlike nanosheet | MoS2 + 3D Graphene foam | Hydrothermal synthesis | 1127 mA h g−1 | [118] |

| Hollow microsphere with onion-like solid nanosphere | MoS2 + C | One step hydrothermal synthesis | 1107 mA h g−1 | [119] |

| Hierarchical nanofiber | MoS2 + active carbon cloth | Simple dissolution and sintering method | 971 mA h g−1 | [120] |

| Flowerlike network | MoS2 + rGO + MWCNT | Hydrothermal synthesis | 1275 mA h g−1 | [121] |

| Sandwich like nanosheet | MoS2 + N-doped carbon | Self-polymerizing and carbonization process | 1239 mA h g−1 | [122] |

| Nanowires | 1D−2D NiMoO4 Nanowires + Metallic 1T MoS2 Composite | Hydrothermal method using blade and spray coating. | 941 mA h g−1 | [123] |

| Nanosheets | Vertically aligned 1T-MoS2 on a graphene frame | Solvothermal method | 666 mAh g−1 | [124] |

| Nanotubes | Metallic MoS2 | Solvothermal method | 1150 mAh g−1 | [125] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omashova, G.; Tussupzhanov, A.; Ramankulov, S.; Katpayeva, K.; Baltabaeyeva, D.; Mussakhan, N.; Kaldar, B. Recent Advances in MoS2-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Structural Features, and Electrochemical Applications. Crystals 2025, 15, 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121037

Omashova G, Tussupzhanov A, Ramankulov S, Katpayeva K, Baltabaeyeva D, Mussakhan N, Kaldar B. Recent Advances in MoS2-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Structural Features, and Electrochemical Applications. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121037

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmashova, Gaukhar, Aidyn Tussupzhanov, Sherzod Ramankulov, Karakoz Katpayeva, Dilnoza Baltabaeyeva, Nurken Mussakhan, and Berik Kaldar. 2025. "Recent Advances in MoS2-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Structural Features, and Electrochemical Applications" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121037

APA StyleOmashova, G., Tussupzhanov, A., Ramankulov, S., Katpayeva, K., Baltabaeyeva, D., Mussakhan, N., & Kaldar, B. (2025). Recent Advances in MoS2-Based Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Structural Features, and Electrochemical Applications. Crystals, 15(12), 1037. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121037