Surface Fatigue Behavior of Duplex Ceramic Composites Under High-Frequency Impact Loading with In Situ Accelerometric Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation and Sample Description

2.2. Surface Fatigue Test

2.3. In Situ Vibration Monitoring and Sensor Configuration

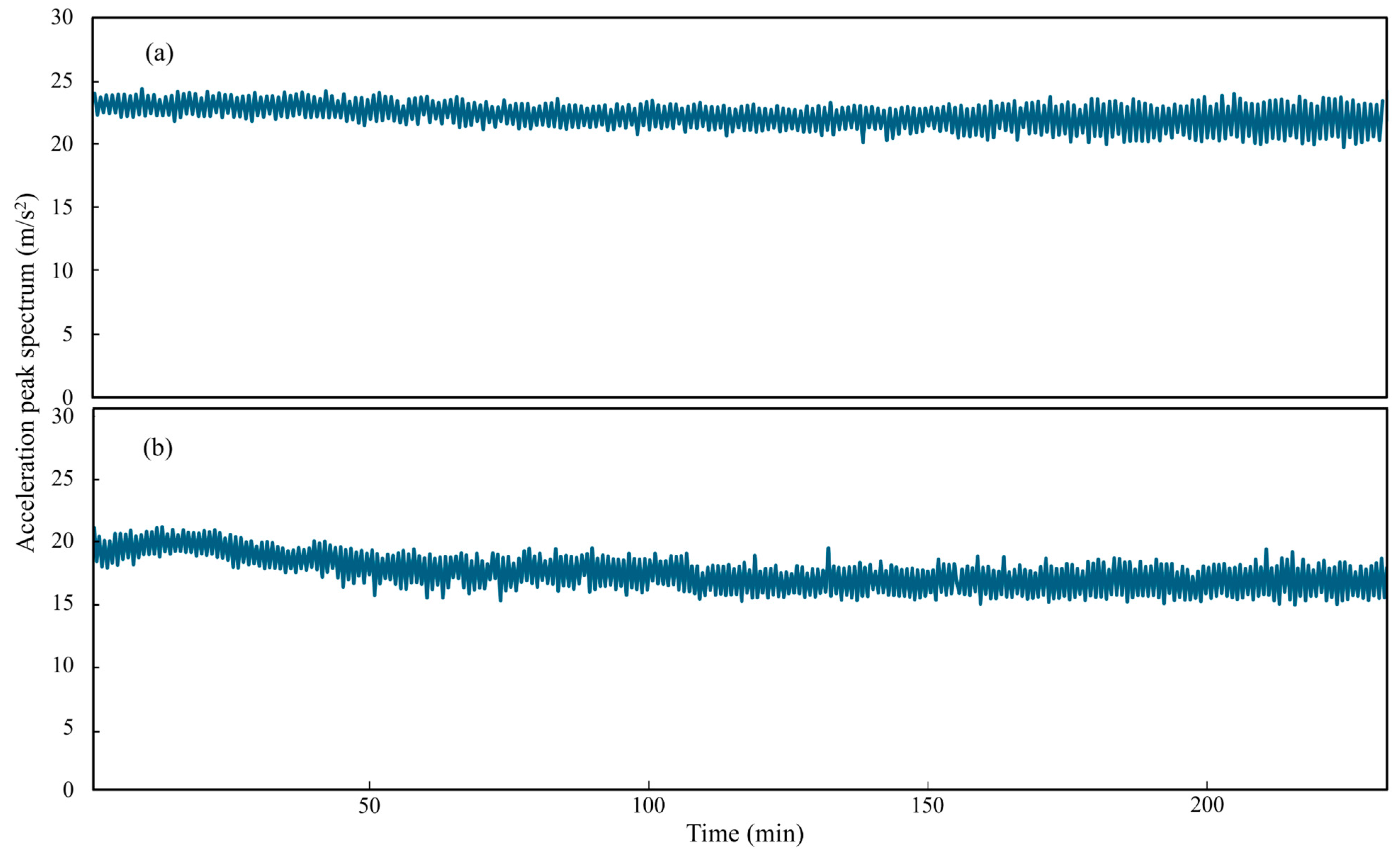

- Acceleration–time signals: Full-range time-domain acceleration data were recorded for the entire surface fatigue test duration (500,000 impacts). These signals allowed the tracking of vibrational changes over time and identification of transient events such as microcrack initiation or progressive surface damage.

- Frequency-domain (FFT) analysis: Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was applied to 10-s segments of the velocity data collected during the stabilized surface fatigue phase (approximately after 30,000 revolutions). This analysis enabled detection of characteristic frequency shifts, peak intensity variations, and damping behavior indicative of surface fatigue damage accumulation.

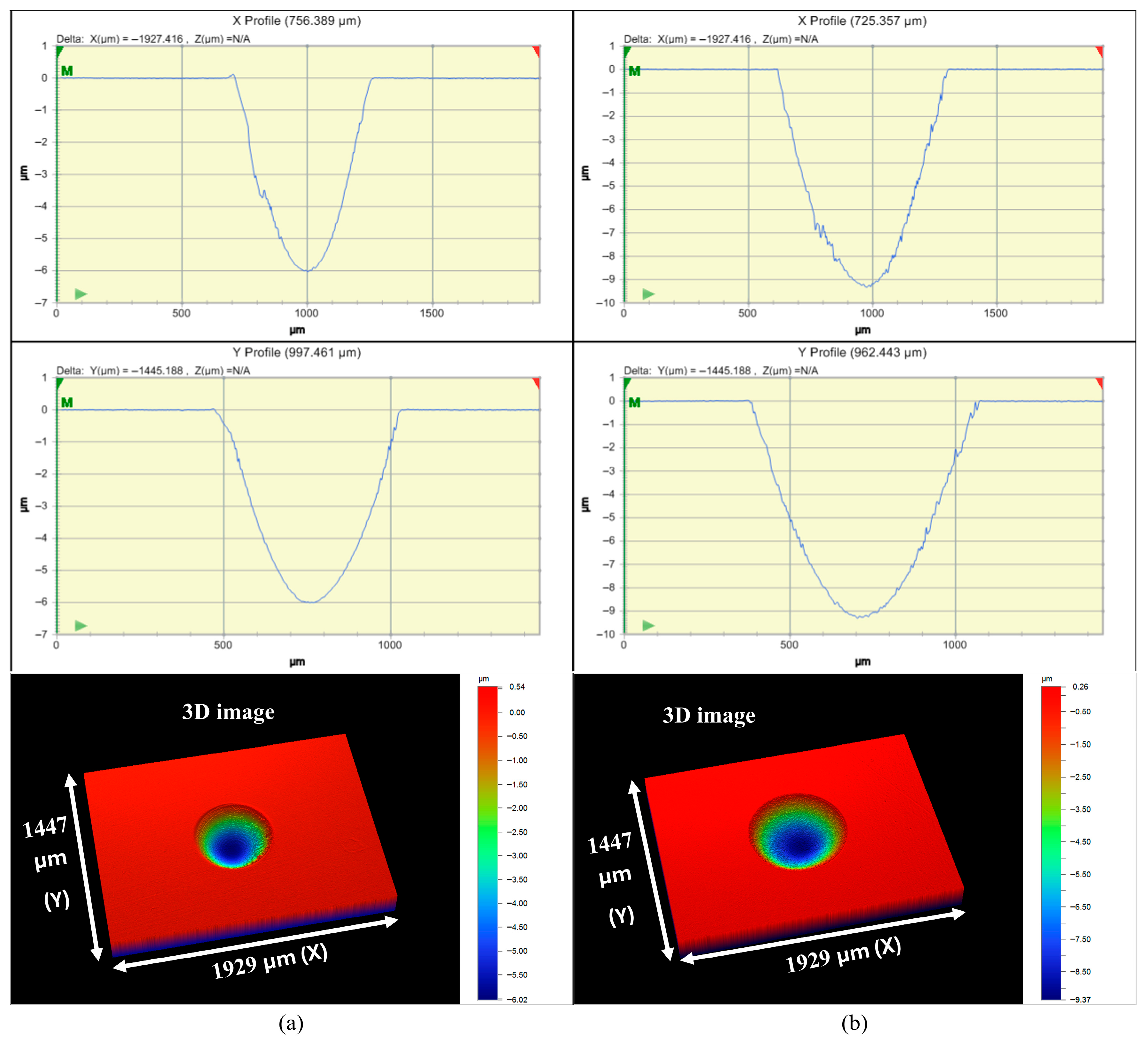

2.4. Surface Fatigue Wear Loss (Net Missing Volume)

2.5. Post-Surface Fatigue Characterization and Destruction Mechanisms

3. Results

4. Discussion

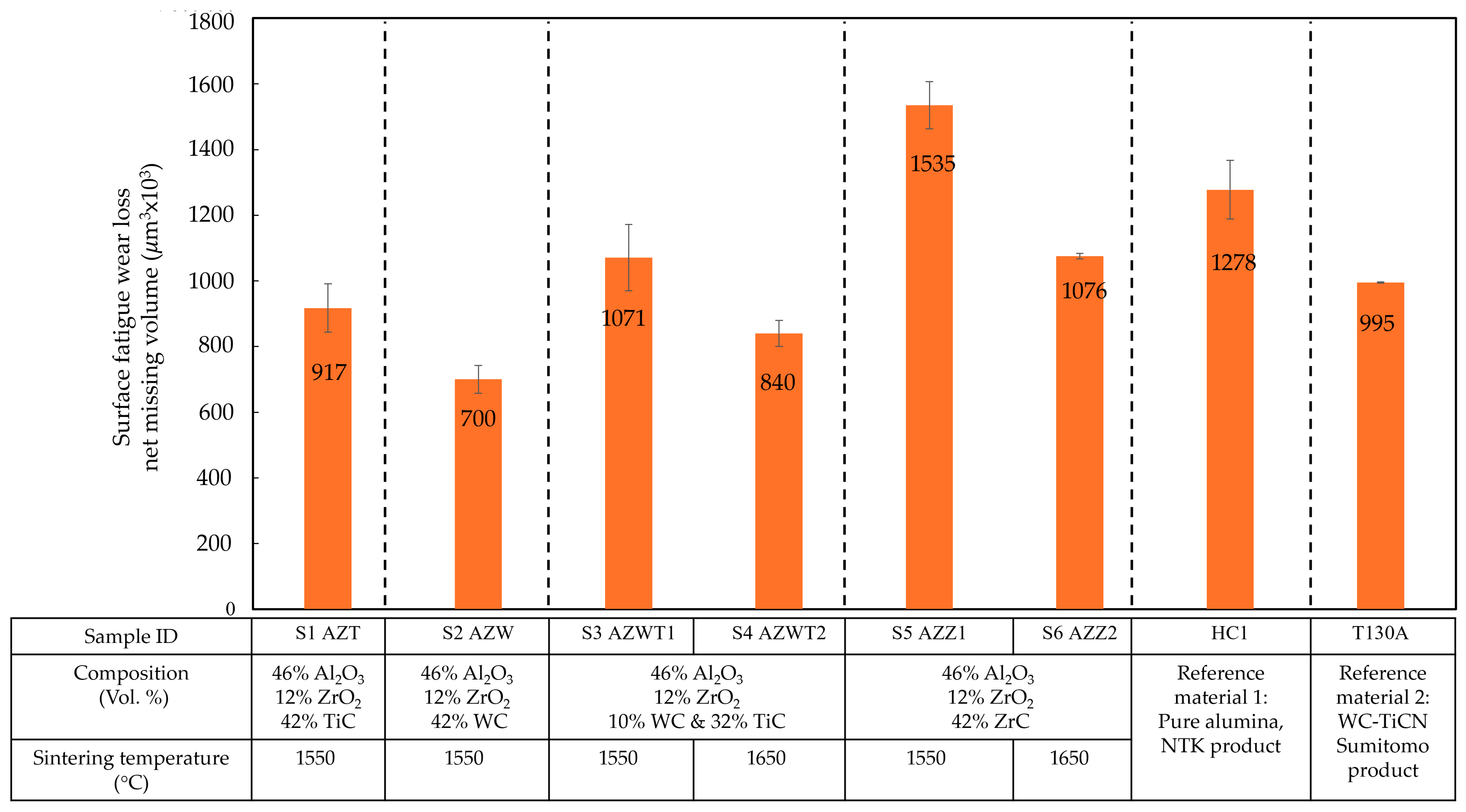

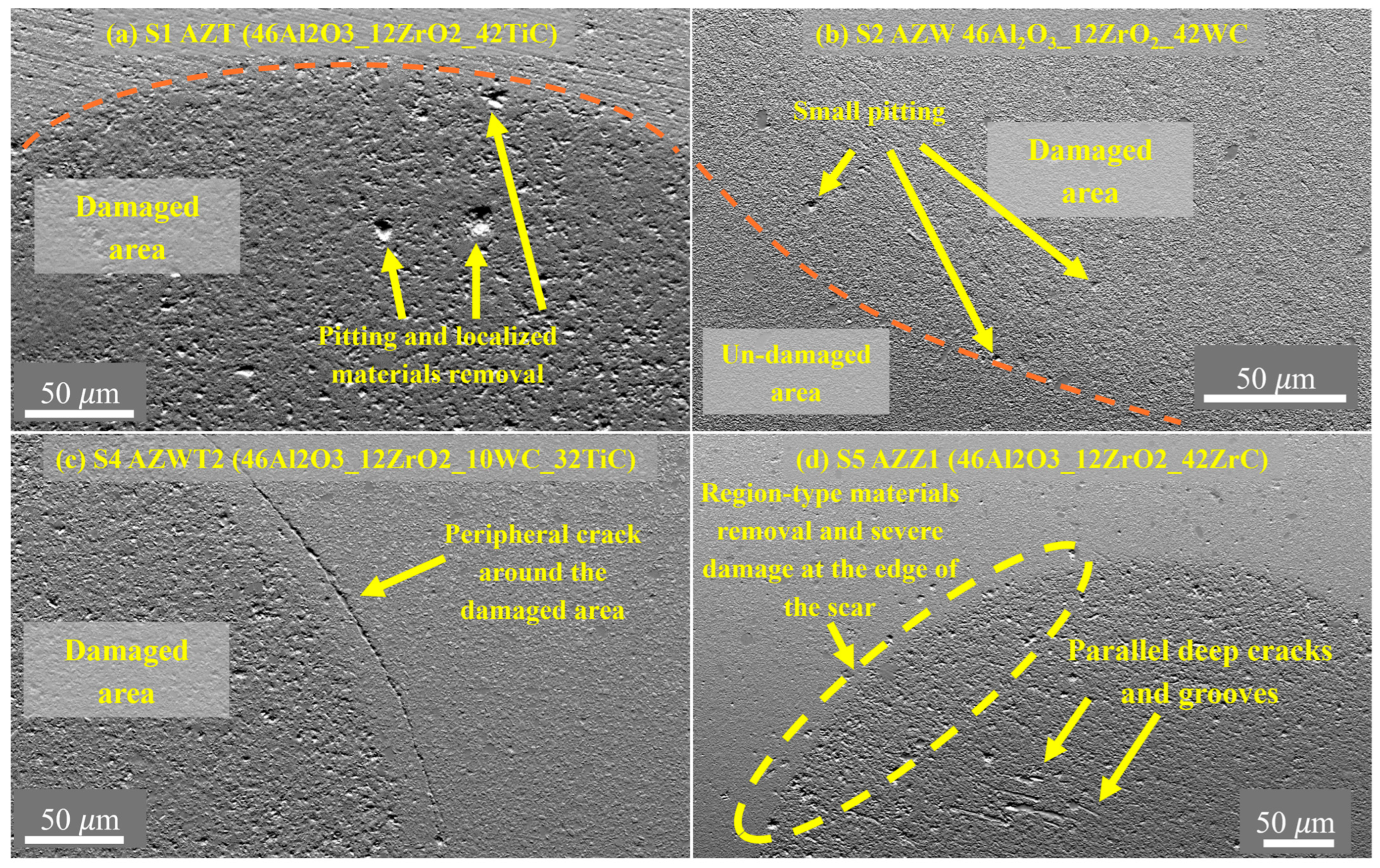

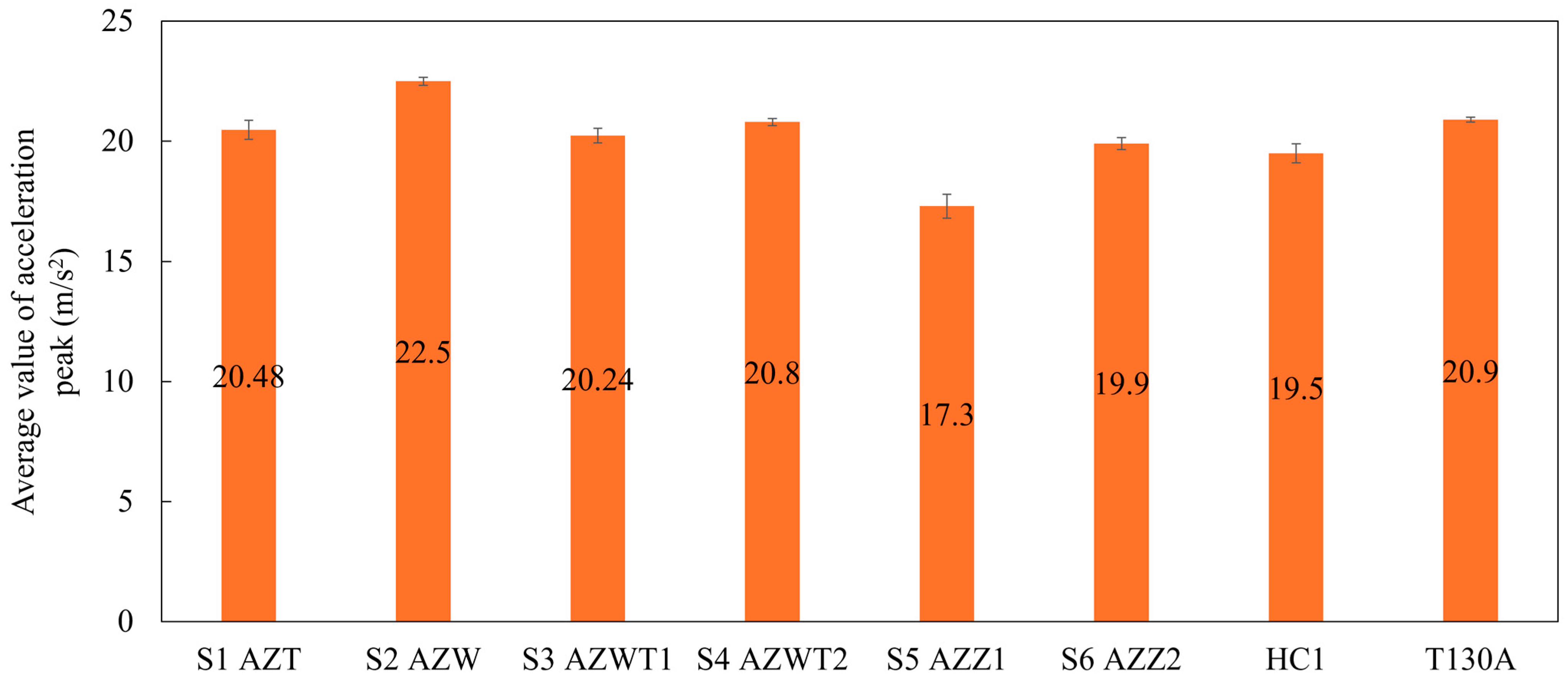

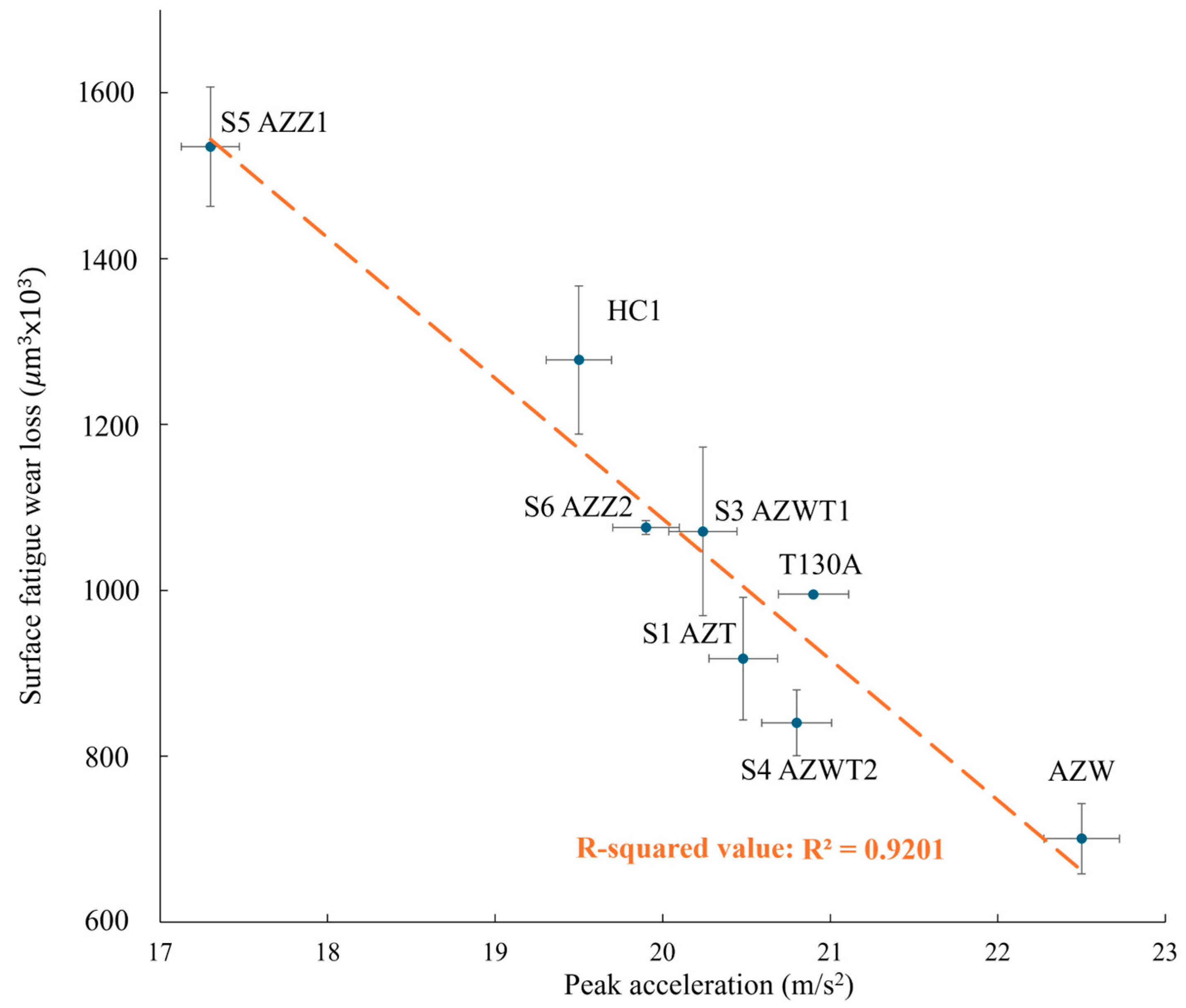

- WC-TiC systems (AZWT1 vs. AZWT2): Increasing the sintering temperature from 1550 °C (S3) to 1650 °C (S4) enhances relative density (99.0% → 99.6%) and Young’s modulus (378 GPa → 387 GPa), leading to improved cyclic impact resistance. Surface fatigue wear loss decreases (1071 µm3 × 103 → 840 µm3 × 103), while acceleration (20.24 m/s2 → 20.80 m/s2) and FFT (2.18 m/s2 → 2.60 m/s2) increase. Besides this densification effect, SEM observations indicate that at the lower sintering temperature (AZWT1), there is more pile-up of debris due to higher porosity than AZWT2. In contrast, the higher temperature condition (AZWT2) produces a more cohesive oxide–carbide network, allowing the mixed WC-TiC structure to redistribute impact stresses more effectively and to shield the Al2O3-ZrO2 oxide structure from catastrophic damage. Even at fixed carbide composition (10 vol.% WC + 32 vol.% TiC), increasing the integrity and continuity of the duplex network via higher sintering temperatures significantly improves surface fatigue behavior by enhancing elastic stiffness and reducing the number of weak interfaces that can act as crack initiation sites. Although the higher sintering temperature causes phase size coarsening (Table 1), this effect does not significantly influence the surface fatigue performance of the AZWT composites.

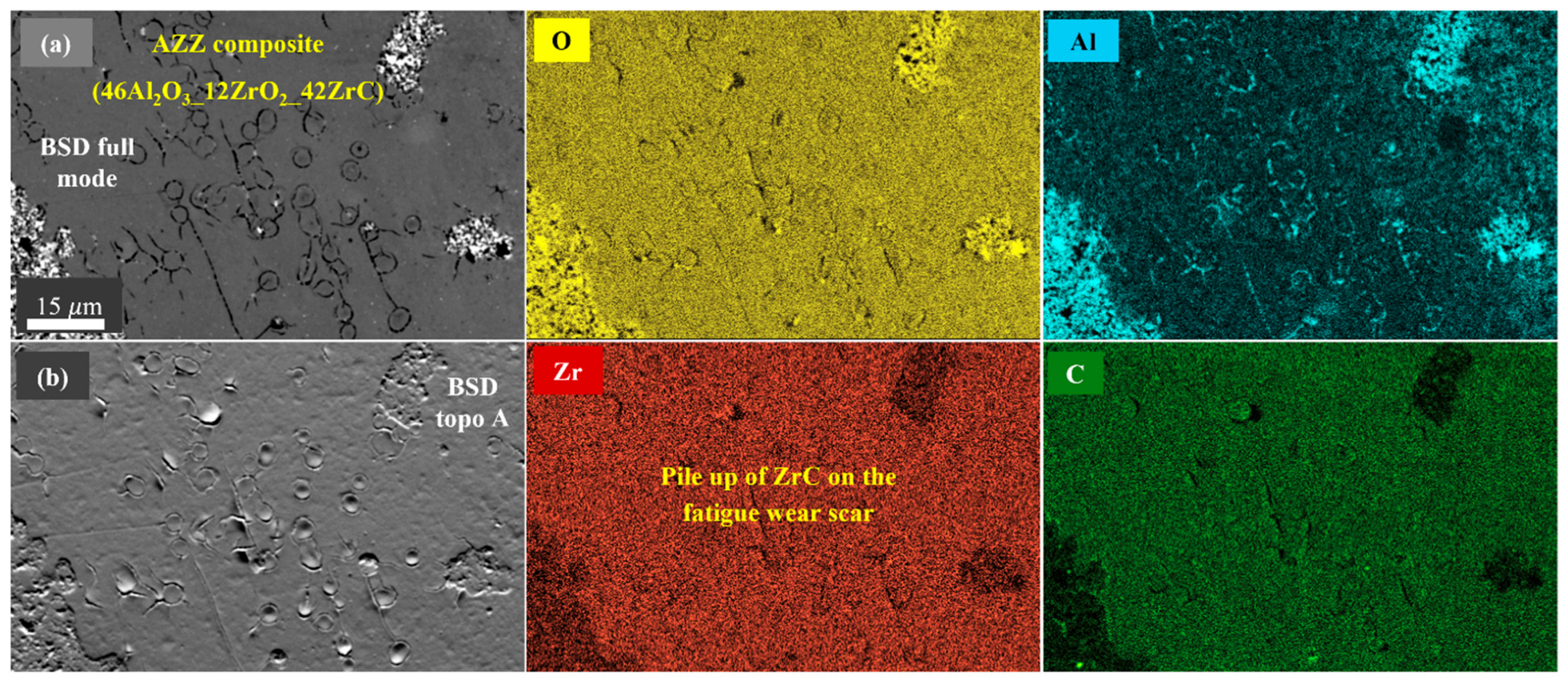

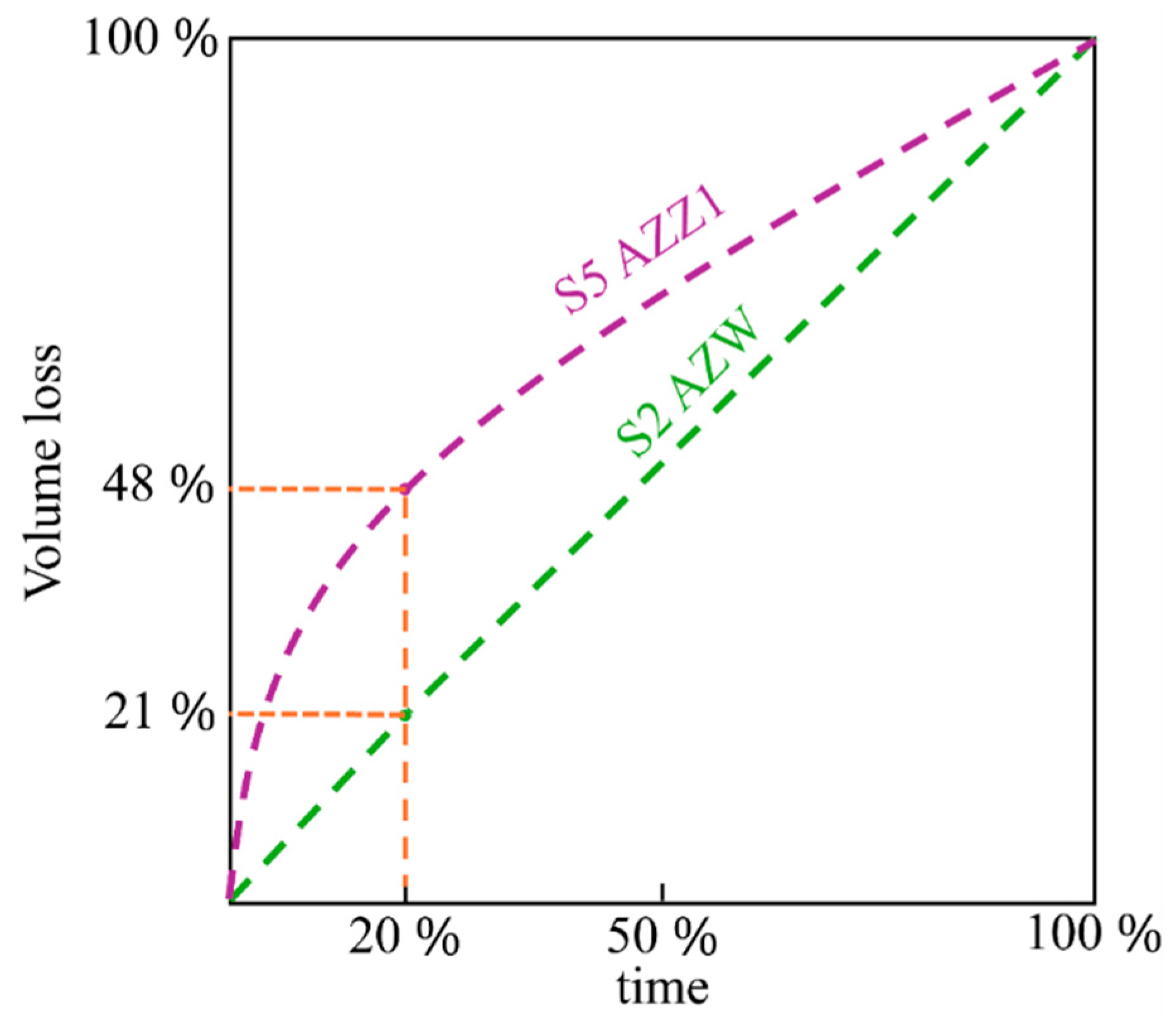

- ZrC systems (AZZ1 vs. AZZ2): Moving from 1550 °C (S5) to 1650 °C (S6) modestly improves density (97.00% → 97.60%) and, likewise, improves surface fatigue resistance: wear 1535 µm3 × 103 → 1076 µm3 × 103, acceleration 17.30 m/s2 → 19.9 m/s2, FFT 1.30 m/s2 → 2.50 m/s2. An increase in relative density improves the structural continuity and reduces the porosity between particles, thereby enhancing the material’s ability to store and release impact energy elastically and to maintain the intensity of the FFT peak. Meanwhile, the larger ZrC phase size in AZZ2 reduces the overall ZrC/oxide interfacial area and the density of sharp triple junctions, thereby mitigating local stress concentrations and delaying interface decohesion. However, ZrC-based composites (AZZ1 and AZZ2) have inferior surface fatigue performance as a result of their composition and relative densities. The ZrC phase has a higher melting point [35] and sintering temperature than WC and TiC, and forms a more brittle, less continuous structure in ceramic–ceramic composites. As a result, ZrC-rich composites show earlier interface decohesion, extensive materials removal, and deep groove formation due to surface fatigue tests, especially in AZZ1. Even when densification is improved by increasing the sintering temperature (AZZ2), which reduces surface fatigue wear loss to 1076 × 103 μm3, the surface fatigue resistance of ZrC-based systems remains clearly lower than that of WC- or TiC-containing composites.

- Across compositions at a ~99.90% density (AZT vs. AZW): Despite similar densification (99.90%), AZW clearly outperforms AZT (with lower surface fatigue wear loss at 700 µm3 × 103 vs. 917 µm3 × 103 and higher acceleration at 22.50 m/s2 vs. 20.48 m/s2). The good behavior of AZW can be attributed to the different mechanical and interfacial characteristics of WC compared with TiC [36]. WC has a higher elastic modulus and hardness and forms a stiffer [37], more effective load-bearing structure within the Al2O3-ZrO2 matrix, which promotes efficient stress transfer and limits local plasticity or microcracking under high-frequency impact loadings. The higher acceleration and FFT amplitude measured for AZW, therefore, reflect a more elastic, rebound-dominated response, whereas the lower dynamic response and higher surface fatigue wear loss of AZT indicate greater conversion of impact energy into microstructural damage and surface degradation.

5. Conclusions

- The Al2O3-ZrO2-WC composite exhibited the lowest surface fatigue wear volume with a shallow, smooth scar and the highest vibration response. Stable acceleration indicated steady material loss during cyclic loading.

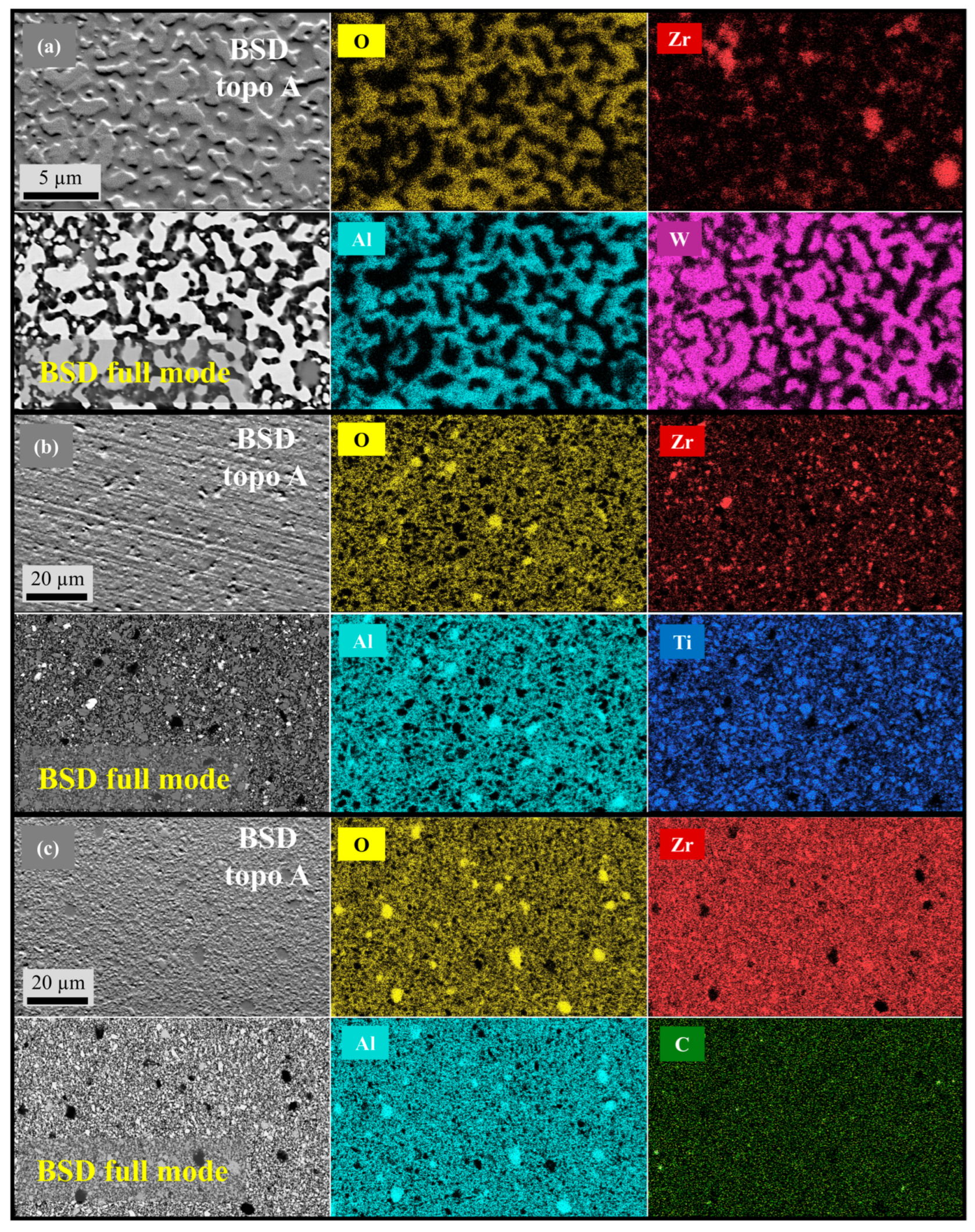

- SEM and EDS analyses confirmed that a continuous duplex interpenetrating structure ensures efficient redistribution of impact stresses, promotion of crack deflection, and delaying damage initiation.

- Peak acceleration emerged as a reliable, real-time indicator of surface fatigue evolution. A strong inverse correlation was observed between mean peak acceleration and surface fatigue wear volume, with higher acceleration amplitudes consistently associated with reduced material loss. In contrast, other dynamic metrics such as velocity amplitude, kurtosis, and crest factor offered limited discriminatory power under the present testing conditions, highlighting the strong sensitivity of acceleration-based monitoring for tracking cyclic impact damage.

- FFT analysis revealed that intact materials maintained strong frequency peaks, whereas degraded surfaces exhibited a dampened frequency intensity, reflecting structural damage.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| EDS | Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy |

| DIPCCs | Duplex Interpenetrating Ceramic Composites |

| BSD | Backscattered Electron Detector |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| SPS | Spark Plasma Sintering |

| Acc | Acceleration |

| AZT | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% TiC composites |

| AZW | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% WC composites |

| AZWT | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-10% WC-32% TiC composites |

| AZZ | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% ZrC composites |

References

- Su, B.; Lu, C.; Li, C. Current Status of Research on Hybrid Ceramic Ball Bearings. Machines 2024, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian Hutchings, P.S. Tribology: Friction and Wear of Engineering Materials; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-H.; Lee, C.-H. Chemical–Mechanical Super-Polishing of Al2O3 (0001) Wafer for Epitaxial Purposes. Crystals 2025, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imariouane, M.; Saâdaoui, M.; Labrador, N.; Reveron, H.; Chevalier, J. Impact Resistance of Yttria- and Ceria-Doped Zirconia Ceramics in Relation to Their Tetragonal-to-Monoclinic Transformation Ability. Ceramics 2025, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassios, K.G.; Matikas, T.E. Assessment of Fatigue Damage and Crack Propagation in Ceramic Matrix Composites by Infrared Thermography. Ceramics 2019, 2, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Stiller, T.; Hausberger, A.; Pinter, G.; Grün, F.; Schwarz, T. Correlation of Tribological Behavior and Fatigue Properties of Filled and Unfilled TPUs. Lubricants 2019, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žmak, I.; Jozić, S.; Ćurković, L.; Filetin, T. Alumina-Based Cutting Tools—A Review of Recent Progress. Materials 2025, 18, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, K.K. Ceramic Matrix Composites. In Composite Materials; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 249–292. [Google Scholar]

- Elgazzar, A.; Zhou, S.-J.; Ouyang, J.-H.; Liu, Z.-G.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-M. A Critical Review of High-Temperature Tribology and Cutting Performance of Cermet and Ceramic Tool Materials. Lubricants 2023, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariminejad, A.; Auriemma, F.; Antonov, M.; Klimczyk, P.; Hussainova, I. Wear Resistance Analysis of Duplex Interpenetrating Ceramic Composites via In-Situ Vibration Monitoring. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2026, 134, 107454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2024/1252 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 April 2024 Establishing a Framework for Ensuring a Secure and Sustainable Supply of Critical Raw Materials and Amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020 (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/oj/eng (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kariminejad, A.; Klimczyk, P.; Antonov, M.; Hussainova, I. From Scrap to Product: The Effect of Recycled Tungsten Carbide and Alumina Content on the Mechanical Properties of Oxide-Carbide Duplex Ceramic Composite. Proc. Est. Acad. Sci. 2025, 74, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuynck, M.; Erauw, J.-P.; Van der Biest, O.; Delannay, F.; Cambier, F. Densification of Alumina by SPS and HP: A Comparative Study. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 32, 1957–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Yoshida, H.; Porwal, H.; Sakka, Y.; Reece, M. Highly Transparent α-Alumina Obtained by Low Cost High Pressure SPS. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandhan, P.; Raphel, A.; Murugasami, R.; Kumaran, S. Spark Plasma Sintering—An Overviews. In Powder Metallurgy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chuvildeev, V.N.; Panov, D.V.; Boldin, M.S.; Nokhrin, A.V.; Blagoveshchensky, Y.V.; Sakharov, N.V.; Shotin, S.V.; Kotkov, D.N. Structure and Properties of Advanced Materials Obtained by Spark Plasma Sintering. Acta Astronaut. 2015, 109, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokita, M. Progress of Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Method, Systems, Ceramics Applications and Industrialization. Ceramics 2021, 4, 160–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygren, M. SPS Processing of Nano-Structured Ceramics. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2007, 14, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, A.; Liu, F. Effect of Cyclic Loading on the Surface Microstructure Evolution in the Pearlitic Rail. Coatings 2023, 13, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhou, J.; Wu, T.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Z. Review and Assessment of Fatigue Delamination Damage of Laminated Composite Structures. Materials 2023, 16, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffa, A.; Palmieri, M.; Morettini, G.; Zucca, G.; Crocetti, F.; Cianetti, F. Development and Validation of a Low-Cost Device for Real-Time Detection of Fatigue Damage of Structures Subjected to Vibrations. Sensors 2023, 23, 5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, A.; Nobile, R. In Situ Fatigue Damage Monitoring by Means of Nonlinear Ultrasonic Measurements. Metals 2023, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanssini, M.; de Aguirre, P.C.C.; Compassi-Severo, L.; Girardi, A.G. A Review on Vibration Monitoring Techniques for Predictive Maintenance of Rotating Machinery. Eng 2023, 4, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnar, G.; Burdzik, R.; Wieczorek, A.N.; Konieczny, Ł. Multidimensional Data Interpretation of Vibration Signals Registered in Different Locations for System Condition Monitoring of a Three-Stage Gear Transmission Operating under Difficult Conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-D.; Shang, D.-G.; Zuo, L.-X.; Qu, L.-F.; Hou, G.; Hao, G.-C.; Shi, F.-T. Vibration Fatigue Life Prediction Method for Needled C/SiC Composite Based on Frequency Response Curve with Low Signal Strength. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 168, 107407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Bocchetta, G.; Botta, F.; Scorza, A. Accuracy Characterization of a MEMS Accelerometer for Vibration Monitoring in a Rotating Framework. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoriev, M.V.; Kotelnikov, N.L.; Buyakova, S.P.; Kulkov, S.N. The Structure and Properties of Composites Al2O3-ZrO2-TiC for Use in Extreme Conditions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1683, 020061. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chai, J.; Shen, T.; Wang, Z. Mechanical and Friction Properties of Al2O3-ZrO2-TiC Composite with Varying TiC Contents Fabricated by Spark Plasma Sintering. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Li, Y. Study on High Temperature Sintering Processes of Selective Laser Sintered Al2O3/ZrO2/TiC Ceramics. Sci. Sinter. 2009, 41, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NTK Cutting Tools, HC1 Grade. Available online: https://ntkcuttingtools.com/products/cast-iron-grade/hc1hw2/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Sumitomo, T130A (Replaced by T1500A). Available online: https://www.sumitool.com/en/products/cutting-tools/inserts/grades/t1000a-t1500a.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kumar, R.; Antonov, M.; Klimczyk, P.; Mikli, V.; Gomon, D. Effect of CBN Content and Additives on Sliding and Surface Fatigue Wear of Spark Plasma Sintered Al2O3-CBN Composites. Wear 2022, 494–495, 204250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.J. On the Nature of Running-In. Tribol. Int. 2005, 38, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.J. Running-in: Art or Engineering? J. Mater. Eng. 1991, 13, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Pei, B.; Han, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z. Microstructure and Properties of Pressureless-Sintered Zirconium Carbide Ceramics with MoSi2 Addition. Materials 2024, 17, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pi, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Du, K. Evaluation Method of Interface Bonding Strength of Cemented Carbide with Additives. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M. Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Properties of TiC-Containing WC-Based Cemented Carbides Prepared by Pressureless Melt Infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 35115–35126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiilakoski, J.; Langlade, C.; Koivuluoto, H.; Vuoristo, P. Characterizing the Micro-Impact Fatigue Behavior of APS and HVOF-Sprayed Ceramic Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 371, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpferle, J.; Röttger, A.; Theisen, W. Fatigue and Surface Spalling of Cemented Carbides under Cyclic Impact Loading–Evaluation of the Mechanical Properties with Respect to Microstructural Processes. Wear 2017, 390–391, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample * | Composition (Vol.%) | Sintering Temperature (°C) | Average Phase Size (μm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al2O3 | ZrO2 | WC | TiC | ZrC | |||

| S1 AZT | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% TiC | 1550 | 2.6 | 1.7 | - | 2.1 | - |

| S2 AZW | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% WC | 1550 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | - | - |

| S3 AZWT1 | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-10% WC-32% TiC | 1550 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.6 | - |

| S4 AZWT2 | 1650 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.2 | - | |

| S5 AZZ1 | 46% Al2O3-12% ZrO2-42% ZrC | 1550 | 2.4 | 1.8 | - | - | 2.6 |

| S6 AZZ2 | 1650 | 3.9 | 2.8 | - | - | 3.5 | |

| HC1 | Reference material: pure alumina, ceramic turning insert, and NTK product [30] | ||||||

| T130A | Reference material: WC-TiCN cermet and Sumitomo product [31] | ||||||

| Sample | Surface Fatigue Mechanisms and Damage (Post-Test) | Vibration Response (Acceleration Peak; FFT ~35 Hz) | Surface Fatigue Wear Loss vs. Acceleration (Figure 13) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 AZT | Localized material removal; limited cracking (Figure 8a). | 20.48 m/s2; 2.45 m/s2 → moderately stiff/low damping. | Mid–high Acc; mid–low surface fatigue wear loss (917 µm3 × 103). |

| S2 AZW | Small, localized removal only at high SEM mag.; shallow scar (~6 µm; ~600 µm diameter). Duplex interpenetrating, coherent interfaces (Figure 14). | 22.5 m/s2; 2.70 m/s2 → highest stiffness/elastic rebound; stable and steady material loss. | Highest Acc; lowest surface fatigue wear loss (700 µm3 × 103) → best performance. |

| S3 AZWT1 | Typical surface fatigue scar; pile-up of debris; damage lower than AZZ but higher than AZW; density-limited continuity. | 20.24 m/s2; 2.18 m/s2 → more damping and energy dissipation than AZWT2. | Lower Acc; higher surface fatigue wear loss (1701 µm3 × 103) vs. S4. |

| S4 AZWT2 | Improved Young’s modulus and hardness vs. S3; pile-up of debris; peripheral cracks. | 20.80 m/s2; 2.60 m/s2 → stiffer than S3 after higher-T sintering. | Higher Acc; lower surface fatigue wear loss (840 µm3 × 103) than S3. |

| S5 AZZ1 | Severe edge damage, region-type materials removal, parallel deep grooves and cracks; (>9 µm depth; ~700 µm dia) ZrC pile up/debris (Figure 5 and Figure 8d). | 17.30 m/s2; 1.30 m/s2 → strong damping from early microcracking; low Acc value from start with fluctuating until the end of the test. | Lowest Acc; highest surface fatigue wear loss (1535 µm3 × 103). |

| S6 AZZ2 | Less severe than S5; densification mitigates cracking; ZrC pile-up/debris. | 19.90 m/s2; 2.50 m/s2 → stiffer than S5. | Higher Acc; lower surface fatigue wear loss (1076 µm3 × 103) than S5. |

| HC1 | ZrO2 pile-up in the scar (EDS) indicating preferential transfer/exposure. | 19.50 m/s2; 1.75 m/s2 → moderate damping. | Mid–low Acc; mid–high surface fatigue wear loss (1278 µm3 × 103). |

| T130A | General surface fatigue scar; ZrO2 pile-up at the center and at the edge of the scar; moderate fatigue wear loss relative to others. | 20.90 m/s2; 2.60 m/s2 → relatively stiff/elastic response. | Mid–high Acc; mid surface fatigue wear loss (995 µm3 × 103). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kariminejad, A.; Antonov, M.; Klimczyk, P.; Hussainova, I. Surface Fatigue Behavior of Duplex Ceramic Composites Under High-Frequency Impact Loading with In Situ Accelerometric Monitoring. Crystals 2025, 15, 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121036

Kariminejad A, Antonov M, Klimczyk P, Hussainova I. Surface Fatigue Behavior of Duplex Ceramic Composites Under High-Frequency Impact Loading with In Situ Accelerometric Monitoring. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121036

Chicago/Turabian StyleKariminejad, Arash, Maksim Antonov, Piotr Klimczyk, and Irina Hussainova. 2025. "Surface Fatigue Behavior of Duplex Ceramic Composites Under High-Frequency Impact Loading with In Situ Accelerometric Monitoring" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121036

APA StyleKariminejad, A., Antonov, M., Klimczyk, P., & Hussainova, I. (2025). Surface Fatigue Behavior of Duplex Ceramic Composites Under High-Frequency Impact Loading with In Situ Accelerometric Monitoring. Crystals, 15(12), 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121036