Abstract

For growth control of graphene, observation techniques, particularly those allowing in situ imaging during synthesis, are essential. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a conventional surface observation method capable of in situ imaging of graphene segregation or growth in chemical vapor deposition, as well as ex situ imaging of synthesized materials. However, secondary electron (SE) emission from graphene is not fully understood, and the contrast formation mechanism of the monolayer material remains unclear. This review summarizes the SEM imaging of graphene, with a focus on SE contrast mechanisms under different conditions. The monolayer graphene layer does not greatly affect SE emission. Its SE contrast is brought from the charging effect, oxidation effect, or attenuation effect of backscattered electron (BSE) from the substrate. Characteristics of SE detectors, such as energy window, acceptance angle, and detected SE/BSE ratio, also contribute to the graphene contrast formation.

1. Introduction

Graphene is a two-dimensional material, consisting of a monolayer of carbon atoms arranged in an sp2-bonded honeycomb structure []. Materials derived from graphene have received significant attention because of their excellent physical, mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties [,,]. Various attempts have been made to synthesize large-scale graphene or to control the number of graphene layers [,,]. For these investigations, observation techniques for the monolayer material—particularly those allowing in situ imaging of dynamic growth processes—are essential, as well as theoretical studies of molecular-level growth mechanisms [,].

Graphene research accelerated after Novoselov et al. demonstrated the production of monolayer graphene by exfoliating graphite, showing that monolayer graphene on a 300 nm SiO2 film is visible under an optical microscope for convenient sample preparation []. However, this optical method only works with specific SiO2 thicknesses and is ineffective for observing graphene growth on metals, though radiation-mode optical microscopy, which uses the difference in the radiation intensity between Cu and graphene, has been used for in situ imaging []. Optical microscopes are further limited by visible light resolution, so electron microscopes have been applied to graphene imaging. Low-energy electron microscopy (LEEM) has been used to observe graphene at high temperatures under ultrahigh vacuum conditions, either during segregation on metal surfaces [,,,] or during thermal decomposition of SiC []. LEEM’s need for a high bias voltage of the specimen limits its use in vapor-phase growth with gases, and its small field of view (<100 μm) is not ideal for monitoring large-area graphene formation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is a conventional surface observation technique and is widely used for the morphology evaluation of specimens []. Nevertheless, SEM has been demonstrated to have sensitivity to monoatomic layers []. Surface sublimation processes in ultrahigh vacuum [,,] and growth processes in molecular beam epitaxy [,,,] have been successfully captured with atomic-layer resolutions.

Ex situ SEM imaging of monolayer graphene has been documented since 2010 [,,,,,,,,], including efforts to improve image contrast [,,,]. SEM was also used for in situ imaging of graphene segregation processes on metal surfaces [,,,] and even for chemical vapor deposition (CVD) processes [,,,,,,]. SEM is currently recognized as a method for imaging graphene. However, graphene, composed of carbon atoms in an atomic-thick layer, presents a non-trivial secondary electron (SE) contrast formation mechanism. Additionally, in situ SEM is conducted at elevated temperatures of 800–1000 °C, leading to differences in graphene contrast compared to ex situ imaging. This review summarizes the SEM imaging of graphene, emphasizing the mechanisms of contrast formation for both ex situ and in situ conditions. Papers are selected based on their relevance to SEM images, which may differ from the original focus of the works.

The contents of this review are as follows.

- Introduction

- Types of SEM Instrument Used for Graphene Imaging

- Ex Situ Imaging of Graphene

- 3.1

- Graphene on SiO2

- 3.2

- Graphene on metals

- 3.3

- Effect of metal oxidation

- 3.4

- Effect of layer stacking

- In Situ Imaging of Graphene

- 4.1

- Segregation process

- 4.2

- Chemical vapor deposition process

- 4.3

- Graphene contrast in in situ observation: Effect of detector

- Challenges and Perspectives

- Conclusions

2. Types of SEM Instruments Used for Graphene Imaging

In SEM, secondary electrons (SEs) are generated by inelastic scattering of the incident electron beam with the target atoms. SEs have kinetic energies of less than 50 eV with a most probable energy of 2−5 eV, while backscattered electrons (BSEs) have a wide energy spectrum up to the primary electron energy (zero-loss peak). The energy and emission angle ranges of detected SEs and BSEs are highly dependent on the SEM instrument type. Here, typical SEM instruments are introduced to better understand the graphene SEM images.

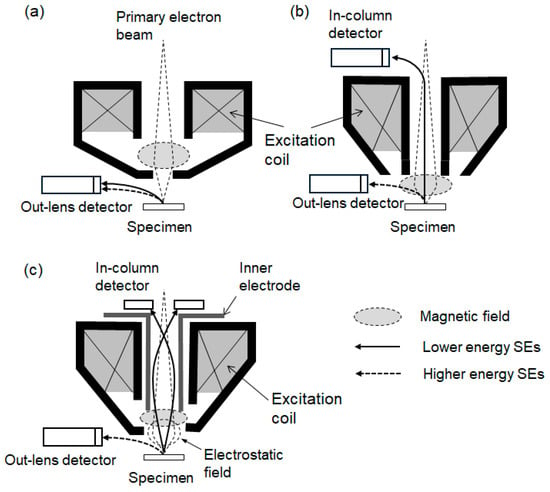

The SEM instrument types can be classified by the objective lens shape, as schematically shown in Figure 1. One is (a) an out-lens type in which the specimen is placed outside the magnetic pole piece of the objective lens, and no magnetic field leaks to the specimen surface. This type is most often used in SEM. The second is (b) a snorkel lens or semi-in-lens type in which the specimen is placed in a leaky magnetic field of the objective lens, and specimens can be observed with a shorter working distance than that of the out-lens type, which is suitable for obtaining a high resolution with a lower primary electron energy. The third is (c) combining a magnetic lens with an electrostatic retarding field (magnetic–electrostatic compound lens type), which is also used to improve the focus of electron beams at low primary electron energies. Because graphene is an atomic-thick layer, SEM observation with a low primary electron energy, 0.1–2 keV, is preferable. Thus, the snorkel lens type and the magnetic–electrostatic compound lens type are often used. Note that those lens shapes in Figure 1 are only schematic. Examples of more realistic illustrations for the snorkel lens and the magnetic–electrostatic compound lens can be found in [,], respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of objective lens types of SEM instrument: (a) out-lens type, (b) snorkel lens (semi-in-lens) type, and (c) magnetic–electrostatic compound lens type.

There is another type in which the specimen is placed between the magnetic pole pieces, like transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and exposed to a magnetic field with a strong lensing effect (in-lens type), allowing high resolution. However, the narrow gap between the magnetic pole pieces limits the specimen thickness and area, and the tilt angle during observation. This is not suitable for in situ observation. This type is not discussed in the present review.

The acceptance windows of the energy and emission angle of SEs and BSEs are strongly dependent on the objective lens type because the effect of magnetic and electrostatic fields is different among them. In the out-lens type, the Everhardt–Thornley detector (E-T detector) [], a scintillator–photomultiplier combination, is used as the SE detector. SEs are accelerated to the scintillator with a bias of 10 kV without a magnetic field, and thus the energy window and acceptance angle are generally wide. The in-column detectors of the snorkel lens and the magnetic–electrostatic compound lens also use a scintillator–photomultiplier combination for SE intensity measurements, but the energy of collected SEs is filtered by the objective lens.

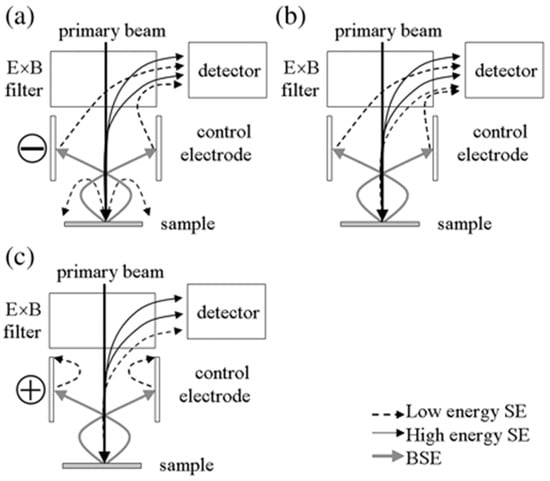

In the snorkel lens, SEs can pass through the objective lens due to the leaky magnetic field, moving upward in a spiral orbit due to the Lorentz force. The E × B system (Wien filter), comprising orthogonal electrostatic and magnetic fields, deflects SEs to the detector without influencing the primary beam (through-the-lens detector). Figure 2 shows the detection system of a snorkel lens-type instrument, Hitachi S-4800 []. There is a control electrode, and by changing its voltage (Vc), detection of SEs as well as BSEs is controlled, thus energy-filtered images or SE and BSE mixed images can be produced. When Vc < 0 V (a) or Vc = 0 V (b), the control electrode works as a conversion electrode to convert BSEs emitted at high angles into low-energy SEs. These SEs carry contrast information characteristic of BSEs.

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of a Hitachi S-4800 SEM instrument with a through-the-lens detector. (a) A high-pass energy-filtering system, (b) an energy-filtering system at Vc = 0 V, and (c) a normal SE detection system. Reprinted with permission from [].

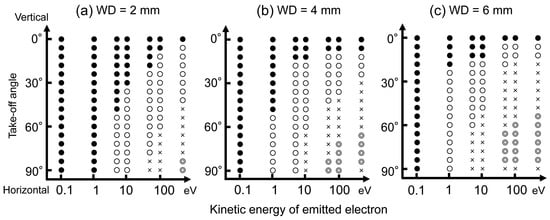

In the magnetic–electrostatic compound lens type, low-energy SEs are accelerated into the lens by the electrostatic field and detected by an annular-shaped in-column (in-lens) detector. Higher-energy SEs emitted with high angles are corrected by an out-lens detector (E-T detector). The ratio of SEs collected by each detector depends on the working distance (WD) between the bottom of the lens and the specimen surface. Tandokoro et al. analyzed acceptance of the in-lens detector and E-T detector for a magnetic–electrostatic compound lens, Gemini system [], by the electron trajectory simulation []. Figure 3 shows the result of the simulation. At WD = 4 and 6 mm, which are typical distances, the in-lens detector captures low-energy SEs (1−10 eV) in a wide range of take-off angles (open circles), while the E-T detector captures > 10 eV SEs emitted at high take-off angles (double circles).

Figure 3.

Acceptance plot generated by trajectory simulation for the Gemini system. Double circles (◎): reaching the E-T detector; open circles (○): reaching the in-lens detector; closed circles (●): going through a hole in the in-lens detector; crosses (×): hitting the pole piece or wall of the SEM chamber. Reprinted with permission from [].

The papers cited in this review are listed in Table 1, along with the SEM instrument used and the type of objective lens. They are categorized by whether they were ex situ or in situ observations and by the type of substrate material. Though some papers contain multiple SEM images, the SEM images of interest are listed as the Figure numbers in the table.

Table 1.

Papers reporting SEM imaging of graphene.

3. Ex Situ Imaging of Graphene

3.1. Graphene on SiO2

On an insulating substrate, the SE contrast of graphene is affected by charging of the substrate surface. A graphene overlayer acts as a conducting layer, reducing the charging effect as well as supplying electrons to the insulator surface. The charging state of the insulating surface depends on the SE yield δ as a function of primary electron energy: if δ > 1, the surface is positively charged, resulting in suppression of SE emission, while for δ < 1, the surface is negatively charged, resulting in enhancement of SE emission []. The charging state is also affected by the primary electron penetration depth. Electron–hole pairs are created in the primary electron penetration range, which induces conductivity. For a thin-layer insulator on a conductive substrate, such as SiO2/Si, a primary electron penetration depth larger than the insulator layer thickness reduces the charging effect []. The SE energy shifts depending on the charging state, and the acceptance energy window is different between E-T and in-column detectors. Therefore, the SE image contrast varies with those factors in a complex manner. Here, we will see three cases.

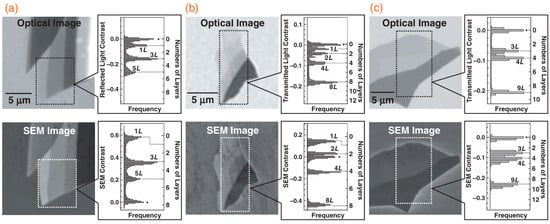

Hiura et al. reported SE imaging of few-layer graphene flakes by an E-T detector []. The graphene flakes were mechanically exfoliated from natural graphite and attached to the surface of a 300 nm-thick SiO2 layer, and thus the number of graphene layers in the flake could be evaluated by optical microscopy. They showed that the contrast of SE images changed discretely depending on the number of graphene layers (Figure 4a). The SE image is the brightest for monolayer graphene and becomes darker with an increase in the number of graphene layers. They obtained similar layer number contrasts of few-layer graphene on mica (b) and sapphire substrates (c).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the counting of layers by optical microscopy and by SEM for graphene on various substrates: SiO2/Si (a), mica (b), and sapphire (c). For each Figure, the upper and lower panels show optical and SEM images, respectively, along with a histogram of the distribution of graphene layers within the rectangular area indicated by a dotted line. An asterisk at zero contrast indicates a substrate peak. All SEM images were observed at 1 kV. Reprinted with permission from [].

Zhou et al. reported similar results of correlation between the SE contrast and graphene layer thickness on a 285 nm-thick SiO2 layer using an in-column detector []. They showed that the distributions of the SE contrast (defined as the intensity difference between graphene and its substrate) had a Gaussian profile with most probable values of (18 ± 1)% and (26 ± 2)% for monolayer and bilayer graphene, respectively. They also reported that the absolute values of the maximized contrasts, as well as the separation of the two distributions, were instrument-independent between Carl Zeiss Supra (type III) and FEI Strata DB235 (type I). Furthermore, the authors showed that the work function of few-layer graphene could be quantified by extracting the SE attenuation contributions from the layer-dependent SE contrast [].

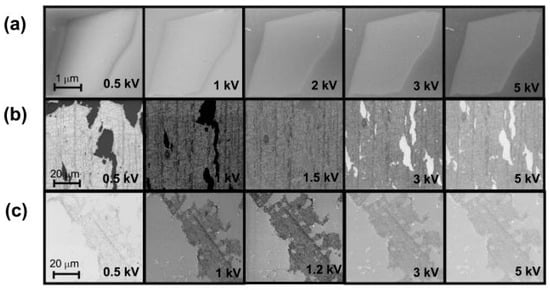

Kochal et al. used an in-column (in-lens) SE detector and evaluated image contrasts of monolayer graphene prepared by exfoliation and CVD growth on different substrates (Figure 5) []. For the exfoliated flake on a 300 nm-thick SiO2 layer (a), the graphene flake appears brighter than the surrounding SiO2 at all primary energies. This is different from the case of a multilayer graphene flake, where it appeared darker than SiO2 for 3–10 kV []. The bright contrast of monolayer graphene is consistent with the case shown in Figure 4a. However, quantitative comparison of the image contrast is difficult because the characteristics of the in-lens detector (Figure 5) and the E-T detector (Figure 4) differ largely.

Figure 5.

In-lens images of (a) exfoliated monolayer graphene on SiO2/Si substrate, (b) CVD-grown monolayer graphene on SiO2/Si substrate, and (c) CVD-grown monolayer graphene on TiOx/Si substrate, for different primary energies. Reprinted with permission from [].

An interesting contrast change is reported for CVD-grown large-area graphene on a 300 nm-thick SiO2 layer (Figure 5b). The SE image brightness of monolayer graphene changed from bright to dark depending on the primary electron energy. As the authors discussed, this contrast change is explained in a manner like the case of carbon nanotubes on a SiO2 layer []: electron supply through electron-beam-induced current (EBIC) in SiO2 plays a crucial role. When the primary electron penetration depth is thinner than the SiO2 layer thickness, the bare SiO2 surface appears dark because of positive charging due to SE emission, while on the graphene-covered surface, electrons are supplied from graphene to the SiO2 surface, recovering intrinsic SE emission []. The same mechanism can be applied to the bright images of the monolayer part of the few-layer graphene flake in Figure 4. When the primary electron penetration depth is larger than the SiO2 layer thickness (3 and 5 kV cases), electrons are supplied from the silicon substrate, too, and thus the bare surface of the SiO2 surface appears bright. It is interesting that the bare SiO2 regions appear much brighter than the graphene-covered surface at 3 and 5 kV. This suggests negative charging of the bare SiO2 surface.

When the SiO2 layer was replaced with a 350 nm TiOx layer, which was a high-k dielectric, CVD-grown graphene always appeared darker than the TiOx surface (Figure 5c). The authors attributed it to screening of surface charge by the high-k material and reducing EBIC.

3.2. Graphene on Metals

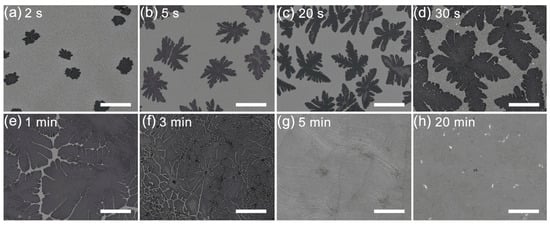

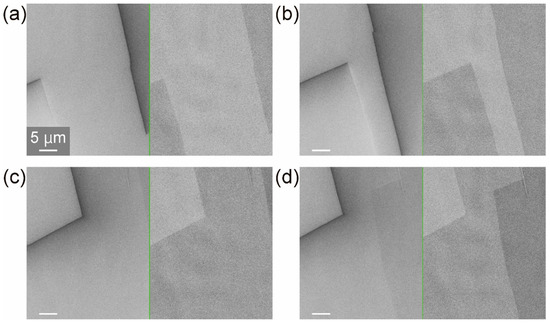

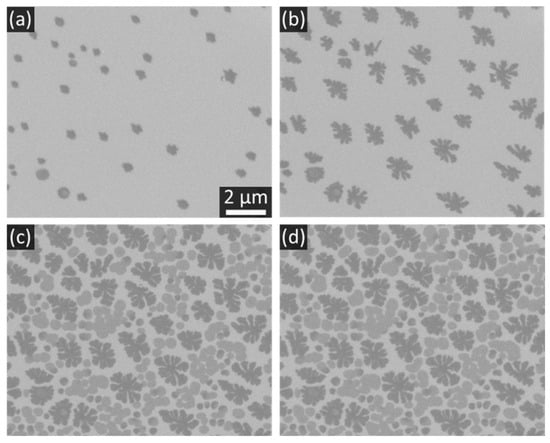

Although SEM images of graphene grown on a Cu foil by CVD can be found in several papers published in 2011 [,,], the measurement conditions are not shown. The monolayer graphene appears darker than the Cu surface in all cases. Typical images are presented in Figure 6, which were observed by interrupting the CVD growth at various times to investigate the graphene growth process []. Dendritic island growth is clearly seen. After completion of one monolayer (5 and 20 min), the SE images appear brighter than those of shorter growth times. This is not due to an increase in graphene layer numbers because the paper reports self-limiting growth of monolayer graphene on the Cu surface, but probably due to the image brightness setting and contrast when SE images were acquired.

Figure 6.

SEM images of as-grown graphene on a copper surface with different CVD growth times. The scale bars are 5 μm. Reprinted with permission from [].

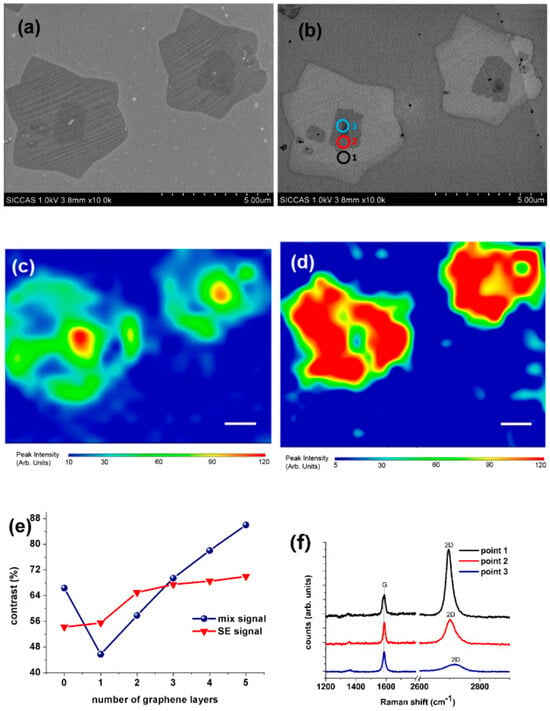

Yang et al. used a snorkel lens-type SEM instrument to characterize the number of graphene layers on Cu surfaces []. They utilized SE signals and BSE signals. By adding 15% of BSE, they could enhance the image contrast change for different numbers of graphene layers. Figure 7 shows SE image (a), mixed SE/BSE image (b), and corresponding Raman mapping of the G peak (c) and 2D peak (d) (Raman spectra are shown in (f)). It is known that the ratio of the 2D peak intensity to the G peak intensity depends on the number of graphene layers []: the ratio is about 2, 1, and 0.5 for mono-, bi-, and three-layer graphene, respectively. While the SE image of graphene appears darker than the Cu surface as is other references, the SE/BSE image contrast varies with the number of graphene layers (Figure 7e). The SE image can distinguish monolayer graphene from few-layer graphene, but the contrast remains almost the same for bilayers and more layers.

Figure 7.

SEM images of isolated few-layer graphene domains of (a) the SE mode and (b) the mixed SE/BSE mode, respectively. Raman mapping of (c) G peak and (d) 2D peak (scale bar 1 m). (e) Curves of average contrast showing the difference between two-mode images. (f) Raman spectra of different points in the SEM image in (b). Reprinted with permission from [].

3.3. Effect of Metal Oxidation

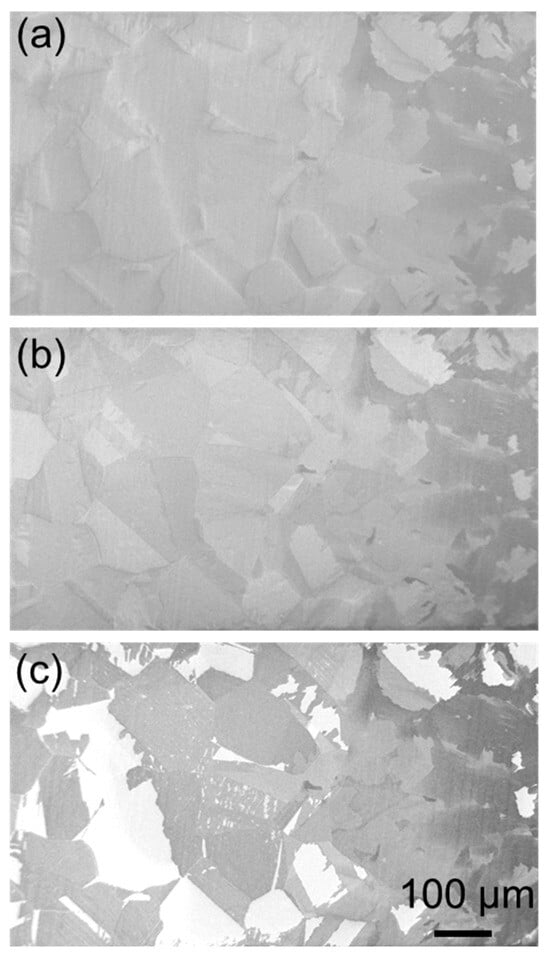

The contrast difference between the Cu surface and monolayer graphene is reversed in Figure 7a,b, the former was SE, and the latter was mixed SE/BSE images. In principle, BSE signals vary sensitively to the atomic number of the target material, and thus increasing the number of graphene layers causes a decrease in the BSE signal intensity. However, the Cu surface exhibits a darker contrast than the mono-layer graphene in Figure 7b. The authors of [] attributed this to oxidation of the bare Cu surface, which led to a lower mean atomic number []. Indeed, oxidation of metal surfaces affects SE emission, too. The bright SE contrast of the Cu surfaces in Figure 6 and Figure 7a, compared to the monolayer graphene-covered regions, is caused by oxidation of the Cu surface. The SE yield of air-exposed metal is higher than that of clean metal []. A graphene overlayer is known to prevent oxidation of the substrate surface []. Therefore, a graphene-covered surface always appears darker than the bare metal surface for ex situ SEM observations. This fact was confirmed by an in situ SEM observation []. Figure 8 shows SE images of a poly-crystalline Ni surface at an elevated temperature (T ≈ 850 °C) during graphene segregation (a), room temperature without exposure to air (b), and room temperature after exposure to air (c). Due to the temperature gradient during heating, the temperature was lower at the right-hand side, resulting in thicker layers of graphene. Thus, the right-hand side of Figure 8a appears darker. Before air exposure shown in Figure 8b, it is difficult to distinguish the bare Ni surface from the graphene-covered regions because of the electron channeling contrast of polycrystal Ni grains. After air exposure shown in Figure 8c, brighter regions appear, which is the result of oxidation of bare Ni surfaces. Obviously, a thin graphene layer does not greatly affect SE emission except for thicker layer regions, which reduce SE emission. A similar contrast change by air exposure is also reported for graphene on a Cu substrate [].

Figure 8.

SEM image contrast for different numbers of layers of graphene on polycrystalline Ni observed at (a) an elevated temperature during carbon segregation, (b) room temperature without exposure to air, and (c) room temperature after exposure to air. In (a), the temperature was lower at the right-hand side, resulting in thicker layers of graphene. The bright regions in (c) correspond to the bare Ni surface. Reprinted with permission from [].

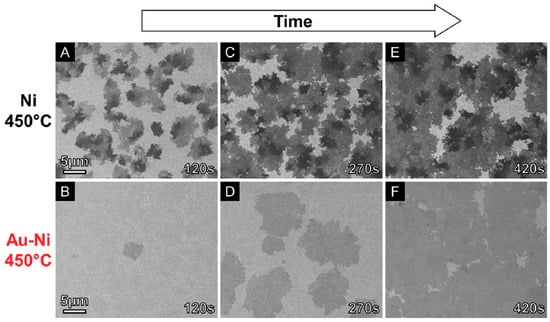

An interesting comparison of SE image contrasts can be found in [] for graphene on Ni and Au-Ni substrates (Figure 9). The graphene contrast on the Au-Ni substrate is not so clear as that on the Ni surface. This might be attributed to the difference in susceptibility to oxidation between these substrates. Au-Ni is reported to provide significant resistance to corrosion [].

Figure 9.

SEM images of as-grown graphene on Ni (A,C,E) and Au(5 nm)-Ni (B,D,F). CVD growth was performed at 450 °C in C2H2 (2 × 10−4 Pa). Reprinted with permission from [].

3.4. Effect of Layer Stacking

In Figure 7 and Figure 8, SE images of graphene-covered regions become darker with an increase in the number of graphene layers. Basically, the SE yield δ of carbon (graphite) is lower than that of metals. For example, δ values at 1 keV primary energy are ≈0.7, ≈1, and ≈1 or higher for C, Cu, and Ni []. However, for the supported graphene layers on a substrate material, the primary electrons backscattered from the substrate material enhance SE emission in the graphene layers. This effect is shielded by thicker graphene layers []. Furthermore, the work function of few-layer graphene increases with an increase in layer numbers, from 4.3 eV for monolayer graphene to 4.6 eV for four-layer graphene and thicker layers [,]. Thus, the SE yield is the highest for monolayer graphene, decreases with an increase in layer numbers, and finally, becomes that of graphite. The same mechanism can be applied to the contrast change in few-layer graphene on SiO2 (Figure 4). Another example of layer contrast will be shown in Figure 18 for few-layer graphene on Pt.

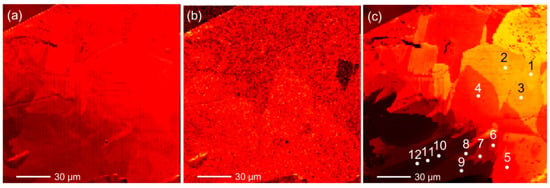

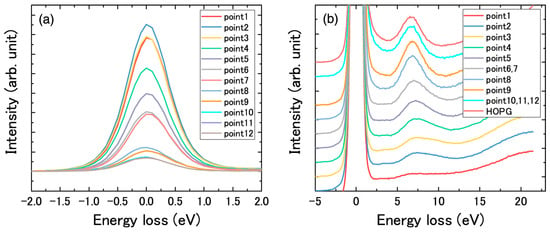

For BSE imaging, attenuation of the metal-origin signal by graphene layers is a dominant factor. Shima et al. used a scanning Auger electron microprobe and performed reflection electron energy loss spectroscopy (REELS) of backscattered electrons from a graphene-covered Ni substrate. Figure 10 shows SE (a), C KLL Auger electron (≈280 eV) (b), and zero-loss peak of backscattered electron (1.5 keV) (c) images obtained at the same position []. The graphene layer thickness varied from zero to more than 10 layers, but the contrast changes in the SE and C KLL images were small. In contrast, the contrast of the zero-loss peak varied in a wide range.

Figure 10.

(a) Secondary-electron, (b) C KLL, and (c) energy-filtered zero-loss peak images obtained by the hemispherical electron analyzer. The numbers in (c) indicate the analysis points. Reprinted with permission from [].

REELS spectra taken at points 1–12 in Figure 10c are shown in Figure 11 for the zero-loss peaks (a), and the energy loss peaks for π–π* transitions (b) (data collected at points 6 and 7, and points 10, 11, and 12 are merged into one line because they are considered to have the same number of layers). Points 1, 2, and 3 in Figure 10c were identified as the bare Ni surface, monolayer graphene, and bilayer-graphene-covered surfaces, respectively. With an increase in the layer number, the intensity of the zero-loss peak decreased, and that of the π–π* loss peak increased. The zero-loss peak represents the backscattered electrons from Ni and is attenuated by the graphene layers via inelastic scattering such as π–π* excitation. The intensities of zero-loss and π–π* loss peaks were well correlated with the number of graphene layers up to nine layers (≈3 nm) [].

Figure 11.

(a) Zero-loss peaks and (b) energy loss spectra containing π–π* loss peak (≈7 eV) from various analysis points in Figure 10c. The spectrum from HOPG is also shown in (b). Reprinted with permission from [].

4. In Situ Imaging of Graphene

4.1. Segregation Process

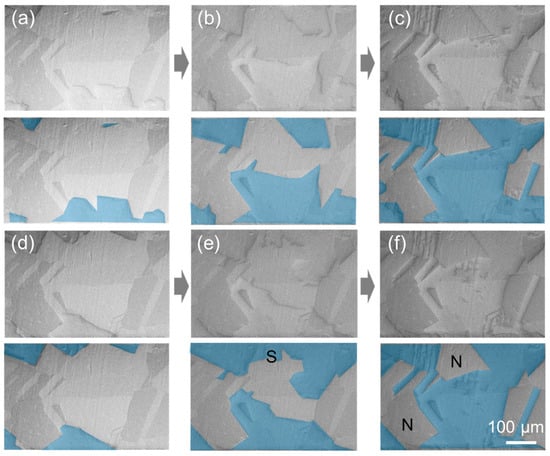

Surface segregation of graphene occurs when carbon-doped metals are cooled from high temperatures [,]. Since segregation can be induced in high vacuum, SEM is suitable for observation. Monolayer graphene segregation on Ni surfaces was observed with an in-column SE detector of Carl Zeiss LEO 1530 VP [,]. Figure 12 shows monolayer graphene segregation process on a poly-crystalline Ni surface at temperature T ≈ 850 °C []. Because the Ni grain contrast hinders recognition of graphene domains, graphene-covered regions are highlighted with shading in the lower panels. The contrast of the graphene domain is almost the same as that of the Ni surface, but their edges appear clearly. There are two types of edge contrasts: dark edges facing downward in the micrograph and bright edges facing upward in the micrograph.

Figure 12.

Successive in situ SEM images observed during graphene segregation at T ≈ 850 °C. The dissolution and segregation of carbon were repeated twice: (a–c) first cycle; (d–f) second cycle. The interval between (a/d) and (b/e) was 0.5 min, and (b/e) and (c/f) was 10 min. The lower panels of each cycle highlight graphene-covered regions with shading. Reprinted with permission from [].

In Figure 12, the dissolution and segregation of carbon were repeated twice, and graphene extended to a similar extent at each cycle. Graphene did not expand into specific grains (denoted as N), or even when small graphene sheets were present on these grains, they soon shrank (denoted as S). These grains were identified as (100) grains by electron backscatter diffraction. To cover (100) grains with graphene, further lowering of temperature was needed [].

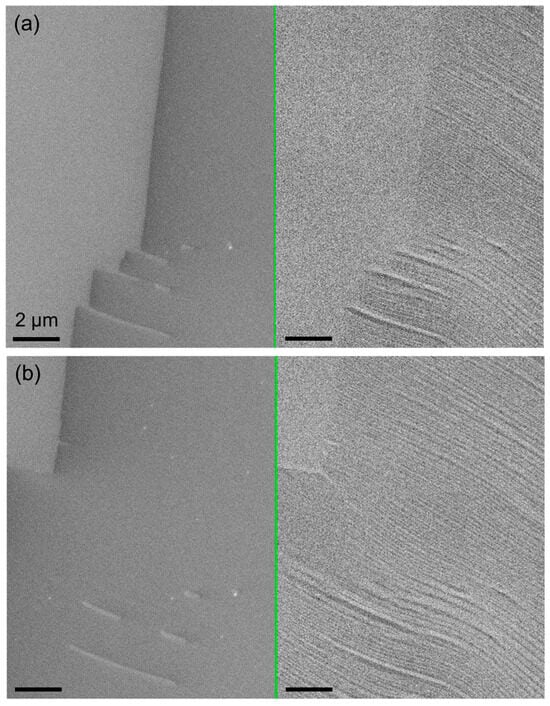

These edge contrasts are more clearly seen on a large Ni(111) grain. Figure 13 shows successive SE images observed during graphene segregation on a Ni(111) grain []. In each panel, left and right images were obtained by the in-column and out-lens detectors, respectively. During observation, two domains of monolayer graphene proceeded from the left and right ends of the view field, as seen in (a) and (b), and then merged in the center in (c). The second layer (indicated as BL) appeared in (d). The edge contrast of monolayer graphene appears as either bright (for the right edge) or dark (for the upper and left edges). The dark contrast extends into the graphene layer as far as 5 μm from the edge. Apart from the edge regions, the brightness of the graphene-covered region is almost the same as that of the bare Ni surface. On the other hand, no such edge contrasts appear in the SE image acquired with the out-lens detector, while the graphene-covered regions appear more clearly, as a darker contrast. The darker area seen in Figure 13d is the second layer of graphene segregated underneath the first layer. Although this second layer can also be recognized in the SE image acquired with the in-column detector, the contrast is less prominent, and the edge contrast is absent. The differences in the SE images of graphene between the two types of detectors presumably stem from the difference in the energy ranges detected. Lower energy SEs are mainly collected by the in-column detector, whereas the remaining higher-energy portion is collected by the out-lens detector [].

Figure 13.

In situ SEM images of the graphene segregation process (a–d) on a wide Ni(111) grain surface observed at T ≈ 800 °C. SE images simultaneously acquired with the in-column (left half) and out-lens (right half) detectors are shown. The labels Ni, ML, and BL in the right images in (a,d) denote nickel, monolayer, and bilayer, respectively. Reprinted from [] under CC-BY 4.0 license.

The difference in performance between the in-column and out-lens detectors is not only the contrast of graphene layers but also the topographic sensitivity. Figure 14 shows in situ observation of the step-bunching process on a vicinal Ni gain surface, comparing the images obtained with the in-column detector and out-lens detector in the same way as Figure 13 []. On the graphene-covered region, which appears darker in the in-column detector image (left panel), stripes corresponding to the step bunching are seen in the out-lens detector image (right panel), where wider and brighter lines are (111) facets and darker lines are step-bunched regions. As the graphene-covered region increased, the step bunching (or faceting) proceeded from right to left in the images. Those stripes cannot be observed by the in-column detector.

Figure 14.

In situ SEM images of graphene segregation on a vicinal Ni grain surface. (a) The surface observed during graphene segregation at T ≈ 800 °C. The left and right images were obtained simultaneously with an in-column detector and out-lens detector, respectively. (b) The same area observed 106 s after (a). Graphene segregation proceeded from right to left in the images. Reprinted with permission from [].

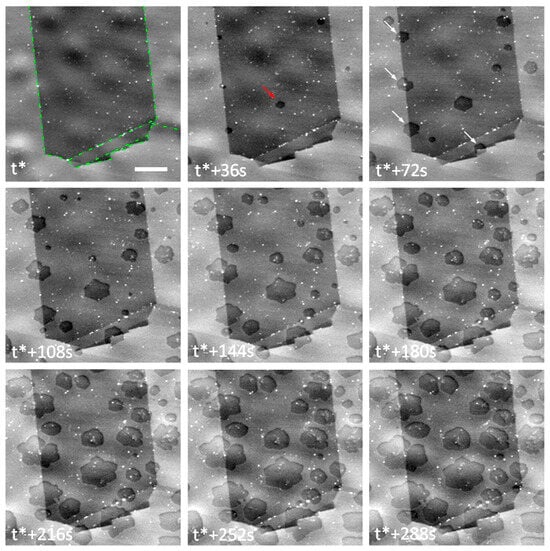

4.2. Chemical Vapor Deposition Process

Real-time in situ imaging for chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of graphene was performed by environmental SEM (ESEM), FEI Quantum 200, which was equipped with a standard E-T detector [,,,,]. In the gaseous modes, the electron column was kept under lower pressure than the specimen chamber, thus SE imaging could be performed during CVD growth. The first real-time ESEM images were reported for graphene growth on Cu during C6H6 (1–5 × 10−1 Pa) exposure at 900 °C together with in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) which was separately performed at the BESSY II synchrotron facility []. In the SE images, graphene nucleation and lateral growth were recorded. Graphene islands appeared darker than the Cu surface. Similar images were reported by the same group, which were observed during C2H4 (2–4 × 10−2 Pa) exposure at 1000 °C []. Figure 15 shows a series of SE images capturing the appearance and growth of graphene sheets on the Cu surface. Grain boundaries in the copper foil are highlighted by green dotted lines in the top left image, which appear darker than other grains due to electron channeling. White arrows highlight nucleation events at grain boundaries. Graphene exhibits a darker contrast than the Cu surface. Detailed analysis of the areal growth of a single flake marked by the red arrow is shown in Figure 4 of []. It is reported that under experimental conditions, the production rate of carbon species by C2H4 decomposition on the Cu surface is lower than their total rate of consumption with nucleation and growth, thus the growth mode changes from attachment-limited to surface-diffusion-limited growth. This change together with accumulation of defects and partial etching of graphene flakes affects the graphene flake shape transformation from initial hexagonal to those at later times. Furthermore, because the loss of Cu due to sublimation is substantial at 1000 °C, the growing graphene sheets cover the Cu surface and lead to hill shapes surrounded by valleys of the uncovered Cu surface [].

Figure 15.

In situ SEM images recorded at 1000 °C during CVD growth. t* corresponds to the induction period from C2H4 dosing until the first nucleation events can be detected. The scale bar is 5 μm. Reprinted with permission from [].

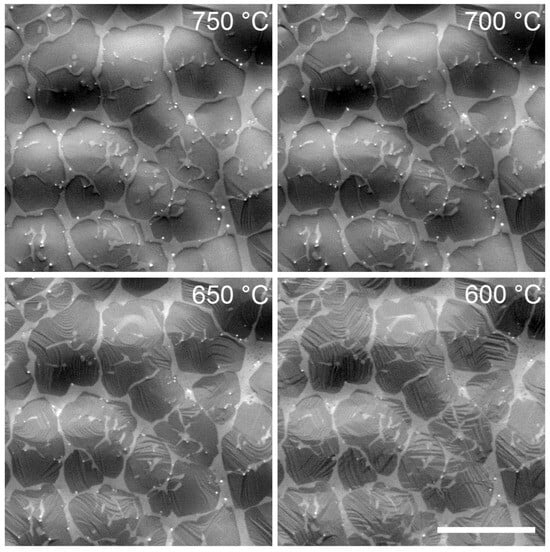

This paper also reports on the in situ SEM images recorded during cooling (Figure 16) []. The faceting of the graphene-covered Cu surface can be seen below 700 °C. The graphene-covered regions have hill shapes, as discussed above, and transform to low-energy graphene–copper interfaces and step bunches during cooling. This is a similar phenomenon to that on the Ni surface shown in Figure 14. The difference in the faceting temperature between Cu and Ni is due to the difference in the surface energy of these metals. A quantitative analysis of graphene-induced faceting in terms of the crystal lattice matching between graphene and metal surface can be found in [].

Figure 16.

In situ SEM images recorded during cooling, showing distinct morphological changes in the Cu surface underneath graphene during cooling. The scale bar is 10 μm. Reprinted with permission from [].

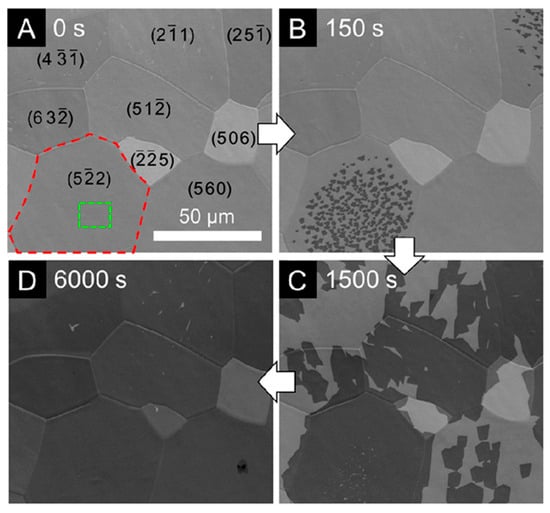

The same group reported in situ SE images of graphene CVD growth on polycrystalline Pt surfaces [,] and single-crystalline Pt(111) surfaces [] at 900 °C. In these papers, graphene exhibits a darker contrast compared to the substrate surface, but the SE image of graphene islands looks flat without edge contrasts, as shown in Figure 17. In this Figure, graphene nucleation first occurs on some Pt grains, and they grow with time and merge with the other domains (B and C). The nucleation of new graphene domains occurs on other Pt grains later (C), while no nucleation events are observed on some grains, like the (4 1) grain, and they are covered with graphene due to the expansion from adjacent Pt grains across boundaries (C and D). The grain-orientation dependent variation in incubation time was attributed to variations in the precursor dissociation rate and/or graphene nucleation barrier affected by the density of grain surface structures such as atomic steps []. The evolution of areal graphene coverage with time is discussed for the regions marked with red (the entire grain) and green (the center of the grain) boxes in A [].

Figure 17.

Graphene growth evolution on polycrystalline Pt. (A–D) Sequence of in situ SEM images of Pt (25 μm) during C2H4 (∼10−2 Par) exposure at 900 °C, acquired 0 s (A), 150 s (B), 1500 s (C), and 6000 s (D) after precursor introduction. The approximate orientations of the Pt grains are indicated in (A). Reprinted with permission from [].

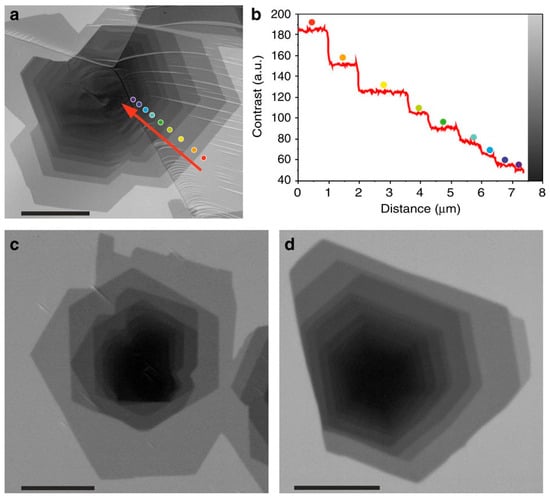

The stacking sequence of few-layer graphene on a polycrystalline Pt foil was traced during C2H4 CVD at 900 °C (Figure 18) []. The SE image in Figure 18a exhibits stepwise variation in the contrast, which corresponds to the stacking of individual graphene layers, starting with the brightest first layer in contact with the Pt substrate. Figure 18b shows the contrast change along the red arrow in Figure 18a. The contrast steps can be distinguished up to nine layers. Figure 18c shows SE images of layer stacking with 30° rotation, while Figure 18d shows the case of stacking while keeping hexagonal shapes. The authors attributed the hexagonal shape distortion in Figure 18d to strong interaction with Pt step edges on the left.

Figure 18.

The SEM image (a) shows a few-layer graphene stack. Along the red arrow, the brightness in the SE image changes with each additional layer. (b) Line plot showing the change in contrast along the red arrow in (a). The different colored dots along the arrow are intended to assist in the assignment between layer number and gray value. (c) Vertical layer stacking showing a 30° rotation between successive layers. (d) Hexagonal layer stacking. The shape is distorted by interaction with the Pt surface. Scale bars, 5 mm (a); 2 mm (c,d). Reprinted from [] under CC-BY 4.0 license.

The contrast step in Figure 18b is large up to the fourth layers, but it becomes smaller for larger numbers of layers. As discussed in Section 3.4, the larger steps up to four layers are due to the work function change depending on the number of graphene layers. Also, the electron backscattering coefficient difference between platinum and carbon contributes to the few-layer graphene contrast. The effect of backscattered electrons is attenuated exponentially with the layer thickness []. However, the contrast change extends to a much deeper region compared to those obtained by the in-column detector (Figure 8) or by the hemispherical electron analyzer (Figure 10a). The layer sensitivity is similar to the case of a zero-loss peak on the Ni surface shown in Figure 10c. For thicker layers, a BSE detection range of the E-T detector might contribute to the contrast change, like the zero-loss peak image.

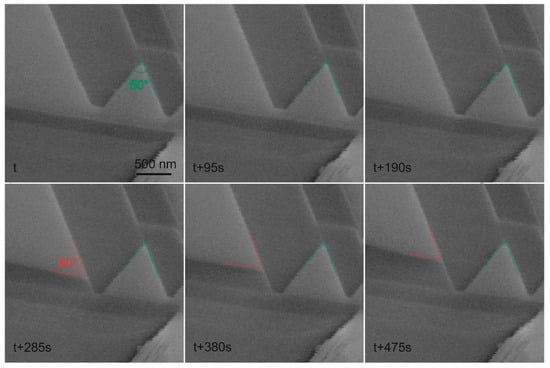

Those SE contrasts of monolayer graphene on Cu and Pt (Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18) are uniform over the graphene layer, including edge parts, though slightly darker edges can be recognized at the upper side of graphene domains on Cu in Figure 15 and Figure 16. On the other hand, SE images of graphene domains on Rh(111) exhibit different contrasts. As shown in Figure 19 [], the monolayer graphene domain has bright edges facing toward the left side and dark edges facing toward the right side of the micrograph. Except for orientations, the edge contrast of graphene domains on Rh, shown in Figure 19, and on Ni, shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, is similar.

Figure 19.

Sequence of in situ SEM images recorded during the coalescence of aligned domains on Rh(111). The green and red lines highlight the intersection corner with angles of 60°. Conditions of growth: 900 °C on Rh(111) at a total pressure of 4.2 × 10−2 Pa (C2H4/H2 = 1:10). Reprinted with permission from [].

4.3. Graphene Contrast in In Situ Observation: Effect of Detector

Only two research groups published in situ observation results: one used a Gemini-type SEM instrument, Carl Zeiss LEO 1530 VP with an in-column detector, and another used a SESM instrument, FEI Quantum 200 with an E-T detector. The reported SE contrasts seem different depending on the instrument type and the substrate species.

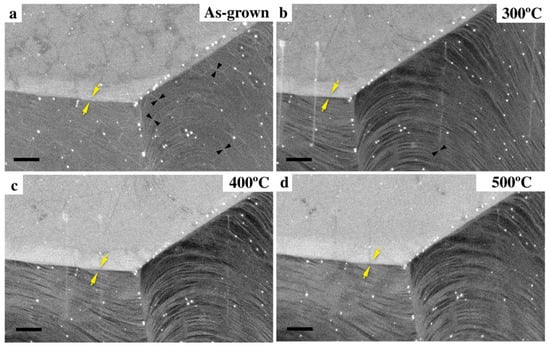

For monolayer graphene on a Ni substrate observed with the in-column detector, peculiar edge contrasts appear at elevated temperatures (Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14). However, these edge contrasts disappeared at room temperature. In Figure 8, which compares SE images observed at an elevated temperature (a) and at room temperature (b), the edge contrasts can be recognized in (a) around the Ni bare surfaces, which appear bright after oxidation, but these surfaces appear flat without edge contrasts in (b). Apart from the edge contrasts, monolayer graphene itself does not exhibit a clear contrast to the substrate surface. Such edge contrasts were absent for graphene on a Cu substrate (Figure 20) []. On the upper Cu grain in (a), graphene domain boundaries are seen as darker lines, but they become faint at 300 °C and disappear at 400 °C. The grain boundaries of graphene, denoted by black arrows in (a), also show a similar behavior. Thus, monolayer graphene on a Cu substrate could not be observed with the in-column detector at elevated temperatures.

Figure 20.

Morphology changes in graphene on Cu substrate by vacuum heating. (a) As-grown graphene on Cu substrate. (b) 300 °C. (c) 400 °C. (d) 500 °C. Yellow arrows and black triangles indicate the grain boundaries of Cu and graphene, respectively. The length of the scale bar is 1 μm. Reprinted with permission from [].

In contrast, monolayer graphene could be observed on a Cu-In alloy with the in-lens detector, as shown in Figure 21, with a darker contrast []. These are not real-time imaging but observed during growth interruption, keeping the temperature (800 °C). Dark flakes in Figure 21a,b are 3D (amorphous-like) carbon islands, and the less-dark flakes in Figure 21c,d are 2D graphene islands. Different from the Ni surface, no prominent edge contrasts were observed. The reason why the peculiar edge contrasts appear only on a Ni surface is unknown, but it might be related to the sensitivity of the in-column detector to specific energies and take-off angles of SEs. The in-column detector accepts SEs emitted with high take-off angles (i.e., grazing angles to the surface) [], which might cause enhanced edge contrasts. The narrow energy window of the detector might be responsible for the variation with the substrate materials, with varying work function and surface conductivity. The wide contrast change that extends to 5 μm from the edge suggests that some potential gradient occurs near the graphene edge (Figure 13).

Figure 21.

In situ SEM images of the initial growth of islands on the solid Cu–In alloy surface. In situ CVD was carried out for 20 min before observing SEM images of (a–d). The carbon source gas, consisting of C2H5OH and H2, flowed into the SEM chamber at 15 Pa at T ≈ 800 °C. Reprinted with permission from [].

An E-T detector, on the other hand, has a wider energy window and take-off angle acceptance because a high extraction voltage is used for collecting SEs. It also detects BSEs emitted within the solid angle seen from the specimen, which depends on the instrument setup. As shown in Figure 7, adding BSE enhances the graphene contrast. Although the exact reason for the high contrast SE images of monolayer graphene obtained by the FEI Quantum 200 is not clear, the characteristics of its E-T detector should be responsible for it. From the comparison between Figure 14 (Carl Zeiss LEO 1530 VP) and Figure 16 (FEI Quantum 200), it is obvious that the E-T detector of FEI Quantum 200 accepts higher-energy SEs as well.

The out-lens detector of the Carl Zeiss LEO 1530 VP is also a kind of E-T detector, but it detects SEs that were not collected by the in-column detector. Thus, its characteristics are different from the E-T detector of the FEI Quantum 200. Nevertheless, the SE image obtained by the out-lens detector shows clearer mono- and bi-layer graphene contrast compared to the in-column detector (Figure 13d). This also demonstrates the effect of the energy window.

5. Challenges and Perspectives

In this review, we discussed the formation mechanisms of graphene SE contrasts. For ex situ imaging, the differences in charging and oxidation states between graphene and substrate materials are responsible for the SE image contrast formation. These are rather large effects in SE emission. On the other hand, charging and oxidation are absent on metal surfaces at elevated temperatures during graphene segregation or CVD growth. The direct SE emission from graphene, as well as the attenuation of substrate-origin SEs, is regarded as small for monolayer graphene. Nevertheless, monolayer graphene could be clearly imaged by the E-T detector of FEI Quantum 200. Quantitative evaluations of SE/BSE emission and attenuation effects are necessary to uncover the physics of graphene imaging by SEM. There have been some attempts to study the SE yields and energy spectra emitted from graphene-coated metals [,,]. However, as discussed in this review, the effect of oxidation as well as surface contamination should be considered. In situ measurements using as-grown specimens are desirable. Furthermore, the temperature and substrate material effects of edge contrast remain unexplored.

For the application of SEM to graphene in situ imaging, energy filtering of SEs is an important technique to enhance the contrast. The implementation of an energy filter to collect higher-energy secondary electrons has been reported to enhance layer contrast []. An interesting approach might be the use of SEs emitted from suspended graphene or other monolayer materials to probe the unoccupied energy states of the material. Theoretically, angle-resolved SE emission spectra are demonstrated to reflect the unoccupied band structure of the atomic sheets []. Angle-resolved measurements of SEs are a possible direction for future development.

6. Conclusions

SEM has been used as an effective method for imaging graphene. However, the SE contrast of graphene is not straightforward. Monolayer graphene itself does not have a large effect on SE emission. The SE contrast depends on the SEM instrument type, in particular, the objective lens and SE detector types, as well as the observation environment. For ex situ SEM observations, charging of the insulating substrate is a dominant factor for conductive graphene imaging, while the difference in oxidation between bare and graphene-covered regions creates SE contrast of graphene on metals. For in situ observations of graphene segregation or CVD at elevated temperatures, characteristics of SE detectors, such as energy window, acceptance angle, and detected SE/BSE ratio, play an important role in graphene contrast formation. An in-lens detector might enhance edge contrasts of graphene, while an E-T detector might enhance the graphene/substrate contrast. It also depends on the substrate material: a flat contrast on Cu, Pt, Ni-Au, and Cu-In, while prominent edge contrasts for Ni and Pd. The instrument types used for in situ SEM observations are still limited, so more systematic research is needed to clarify SE image formation mechanisms for monolayer materials.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Tokyo University of Science for granting him access to online journals as a visiting professor.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSE | Backscattered electron |

| CVD | Chemical vapor deposition |

| SE | Secondary electron |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

References

- Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.J.; Tung, V.C.; Kaner, R.B. Honeycomb Carbon: A Review of Graphene. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urade, A.R.; Lahiri, I.; Suresh, K.S. Graphene Properties, Synthesis and Applications: A Review. JOM 2023, 75, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Yun, S.J.; Won, Y.S.; Oh, C.S.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, Y.H. Large-scale synthesis of graphene and other 2D materials towards industrialization. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ruoff, R.S. Growth of Single-Layer and Multilayer Graphene on Cu/Ni Alloy Substrates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 800–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tau, O.; Lovergine, N.; Prete, P. Adsorption and decomposition steps on Cu(111) of liquid aromatic hydrocarbon precursors for low-temperature CVD of graphene: A DFT study. Carbon 2023, 206, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau, O.; Lovergine, N.; Prete, P. Molecular decomposition reactions and early nucleation in CVD growth of graphene on Cu and Si substrates from toluene. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optics + Photonics 2024-Nanoscience + Engineering Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–23 August 2024; Volume 13114. [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Yiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasawa, T.; Saiki, K. Radiation-mode optical microscopy on the growth of graphene. Nat. Commun. 2015, 7, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginova, E.; Nie, S.; Thürmer, K.; Bartelt, N.C.; McCarty, K.F. Defects of graphene on Ir(111): Rotational domains and ridges. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 085430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, P.; Sadowski, J.T.; Sutter, E. Graphene on Pt(111): Growth and substrate interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 245411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wofford, J.M.; Nie, S.; McCarty, K.F.; Bartelt, N.C.; Dubon, O.D. Graphene Islands on Cu Foils: The Interplay between Shape, Orientation, and Defects. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4890–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odahara, G.; Hibino, H.; Nakayama, N.; Shimbata, T.; Oshima, C.; Otani, S.; Suzuki, M.; Yasue, T.; Koshikawa, T. Macroscopic Single-Domain Graphene Growth on Polycrystalline Nickel Surface. Appl. Phys. Express 2012, 5, 035501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, H.; Kageshima, H.; Nagase, M. Epitaxial few-layer graphene: Towards single crystal growth. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 374005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, L. Scanning Electron Microscopy: Physics of Image Formation and Microanalysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Tomita, M. Atomic Configuration Dependent Secondary Electron Emission from Reconstructed Silicon Surfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1993, 62, 3276–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Hibino, H.; Ogino, T.; Aizawa, N. Sublimation of Si(111) Surface in Ultrahigh Vacuum. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, R10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnie, P.; Homma, Y. Dynamics, Interactions, and Collisions of Atomic Steps on Si(111) in Sublimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 2737–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Hibino, H.; Kunii, Y.; Ogino, T. Transformation of surface structures on vicinal Si(111) during heating. Surf. Sci. 2000, 445, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Osaka, J.; Inoue, N. In-situ Observation of Monolayer Steps During Molecular Beam Epitaxy of Gallium Arsenide by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 33, L563–L566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Homma, Y. Imaging of Layer by Layer Growth Processes During Molecular Beam Epitaxy of GaAs on (111)A Substrates by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73, 3079–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnie, P.; Homma, Y. Nucleation and step flow on ultraflat silicon. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, 8313–8317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Finnie, P.; Uwaha, M. Morphological Instability of Atomic Steps Observed on Si(111) Surfaces. Surf. Sci. 2001, 492, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiura, H.; Miyazaki, H.; Tsukagoshi, K. Determination of the Number of Graphene Layers: Discrete Distribution of the Secondary Electron Intensity Stemming from Individual Graphene Layers. Appl. Phys. Express 2010, 3, 095101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochat, V.; Pal, A.N.; Sneha, E.S.; Sampathkumar, A.; Gairola, A.; Shivashankar, S.A.; Raghavan, S.; Ghosh, A. High contrast imaging and thickness determination of graphene with in-column secondary electron microscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 014315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fox, D.S.; Maguire, P.; O’Connell, R.; Masters, R.; Rodenburg, C.; Wu, H.; Dapor, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Quantitative secondary electron imaging for work function extraction at atomic level and layer identification of graphene. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.W.; Warner, J.H. Hexagonal Single Crystal Domains of Few-Layer Graphene on Copper Foils. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Kim, S.; Kawamoto, N.; Rappe, A.M.; Johnson, A.T.C. Growth Mechanism of Hexagonal-Shape Graphene Flakes with Zigzag Edges. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9154–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, G.H.; Günes, F.; Bae, J.J.; Kim, E.S.; Chae, S.J.; Shin, H.-J.; Choi, J.-Y.; Pribat, D.; Lee, Y.H. Influence of Copper Morphology in Forming Nucleation Seeds for Graphene Growth. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4144–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weatherup, R.S.; Bayer, B.C.; Blume, R.; Ducati, C.; Baehtz, C.; Schloegl, R.; Hofmann, S. In Situ Characterization of Alloy Catalysts for Low-Temperature Graphene Growth. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4154–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Gao, L.; Sun, J. A facile method to observe graphene growth on copper foil. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 475705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Kumamoto, A.; Kim, S.; Chen, X.; Hou, B.; Chiashi, S.; Einarsson, E.; Ikuhara, Y.; Maruyama, S. Self-Limiting Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of Monolayer Graphene from Ethanol. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 10755–10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, M.; Kato, H.; Shihommatsu, K.; Homma, Y. Determination of absolute number of graphene layers on nickel substrate with scanning Auger microprobe. Appl. Phys. Express 2020, 13, 015502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamada, K.; Kato, K.; Hibino, H.; Homma, Y. In situ scanning electron microscopy of graphene growth on polycrystalline Ni substrate. Surf. Sci. 2012, 606, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momiuchi, Y.; Yamada, K.; Kato, H.; Homma, Y.; Hibino, H.; Odahara, G.; Oshima, C. In situ scanning electron microscopy of graphene nucleation during segregation of carbon on polycrystalline Ni substrate. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 455301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihommatsu, K.; Takahashi, J.; Momiuchi, Y.; Hoshi, Y.; Kato, H.; Homma, Y. Formation Mechanism of Secondary Electron Contrast of Graphene Layers on a Metal Substrate. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 7831–7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, E.; Shihommatsu, K.; Takahashi, J.; Kato, H.; Homma, Y. Characterization of Au intercalation at the interface of graphene/polycrystalline Ni substrate. Surf. Sci. 2020, 700, 121613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidambi, P.R.; Bayer, B.C.; Blume, R.; Wang, Z.-J.; Baehtz, C.; Weatherup, R.S.; Willinger, M.-G.; Schloegl, R.; Hofmann, S. Observing Graphene Grow: Catalyst−Graphene Interactions during Scalable Graphene Growth on Polycrystalline Copper. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 4769–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Weinberg, G.; Zhang, Q.; Lunkenbein, T.; Klein-Hoffmann, K.; Kurnatowska, M.; Plodinec, M.; Li, Q.; Chi, L.; Schloegl, R.; et al. Direct Observation of Graphene Growth and Associated Copper Substrate Dynamics by In Situ Scanning Electron Microscopy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 1506–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Dong, J.; Cui, Y.; Eres, G.; Timpe, O.; Fu, Q.; Ding, F.; Schloegl, R.; Willinger, M.-G. Stacking Sequence and Interlayer Coupling in Few-layer Graphene Revealed by In Situ Imaging. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherup, R.S.; Shahani, A.J.; Wang, Z.-J.; Mingard, K.; Pollard, A.J.; Willinger, M.-G.; Schloegl, R.; Voorhees, P.W.; Hofmann, S. In Situ Graphene Growth Dynamics on Polycrystalline Catalyst Foils. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 6196–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Dong, J.; Li, L.; Dong, G.; Cui, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wei, W.; Blume, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, L.; et al. The Coalescence Behavior of Two-Dimensional Materials Revealed by Multiscale In Situ Imaging during Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1902–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yamada, C.; Homma, Y. Scanning electron microscopy imaging mechanisms of CVD-grown graphene on Cu substrate revealed by in situ observation. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 54, 050301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, Y.; Takahashi, J.; Wang, H.; Kato, H.; Homma, Y. Crossover of 2D graphene and 3D carbon island growth on Cu-In alloy surface. Surf. Sci. 2018, 670, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Sunaoshi, T.; Yamazawa, Y. Voltage contrast imaging with energy filtered signal in a field-emission scanning electron microscope. Ultramicroscopy 2020, 209, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaksch, H.; Martin, J.P. High-resolution, low-voltage SEM for true surface imaging and analysis. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1995, 353, 378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Everhardt, T.E.; Thornley, R.F. Wide-band detector for micro-microampere low-energy electron currents. J. Sci. Instrum. 1960, 37, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, D.; Hamada, K.; Kawasaki, Y. Energy-filtered imaging in a scanning electron microscope for dopant contrast in InP. J. Electron Microsc. 2010, 59 (Suppl. 1), S183–S187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandokoro, K.; Nagoshi, M.; Kawano, T.; Sato, K.; Tsuno, K. Low-voltage SEM contrasts of steel surface studied by observations and electron trajectory simulations for GEMINI lens system. Microscopy 2018, 67, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, D.C.; Joy, C.S. Dynamic Charging in the Low Voltage SEM. Microsc. Microanal. 1995, 1, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nagase, M.; Takagi, D. Mechanism of bright selective imaging of single-walled carbon nanotubes on insulators by scanning electron microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 1750–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S.; et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilleret, H.; Scheuerlein, C.; Taborelli, M. The secondary-electron yield of air-exposed metal surfaces. Appl. Phys. A 2003, 76, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.S.; Brown, L.; Levendorf, M.; Cai, W.W.; Ju, S.Y.; Edgeworth, J.; Li, X.S.; Magnuson, C.W.; Velamakanni, A.; Piner, R.D.; et al. Oxidation Resistance of Graphene-Coated Cu and Cu/Ni Alloy. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, J.; Huang, D.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, L.; Fan, X. Effect of Deposition Parameters for Ni-Au Coatings on Corrosion Protection Properties of 2A12 Aluminum Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.G.H.; El-Gomati, M.M.; Assa’d, A.M.D.; Zadražil, M. The Secondary Electron Emission Yield for 24 Solid Elements Excited by Primary Electrons in the Range 250–5000 eV: A Theory/Experiment Comparison. Scanning 2008, 30, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.C.; Patil, H.R.; Blakely, J.M. Equilibrium segregation of carbon to a nickel (111) surface: A surface phase transition. Surf. Sci. 1974, 43, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, M.; Blakely, J.M. Carbon monolayer phase condensation on Ni(111). Surf. Sci. 1979, 82, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.; Ueyama, T.; Kamei, K.; Kato, H.; Homma, Y. Experimental and theoretical studies on the surface morphology variation of a Ni substrate by graphene growth. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 024302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, P.; Cupolillo, A.; Pisarra, M.; Sindona, A.; Caputi, L.S. Primary energy dependence of secondary electron emission from graphene adsorbed on Ni(111). Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 183102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, X.-S.; Liu, W.-H.; Wang, H.-G.; Li, Y.-D. Secondary electron emission of graphene-coated copper. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2017, 73, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.K.A.; Mankowski, J.; Dickens, J.C.; Neuber, A.A.; Joshia, R.P. Calculations of secondary electron yield of graphene coated copper for vacuum electronic applications. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 015325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Watanabe, K. Time-dependent first-principles study of angle-resolved secondary electron emission from atomic sheets. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 075406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).