2D Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Hybrid Heterostructures: Single Crystals, Thin Films and Exfoliated Flakes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Crystal Growth and Characterization

2.1. Starting Materials

2.2. Synthesis

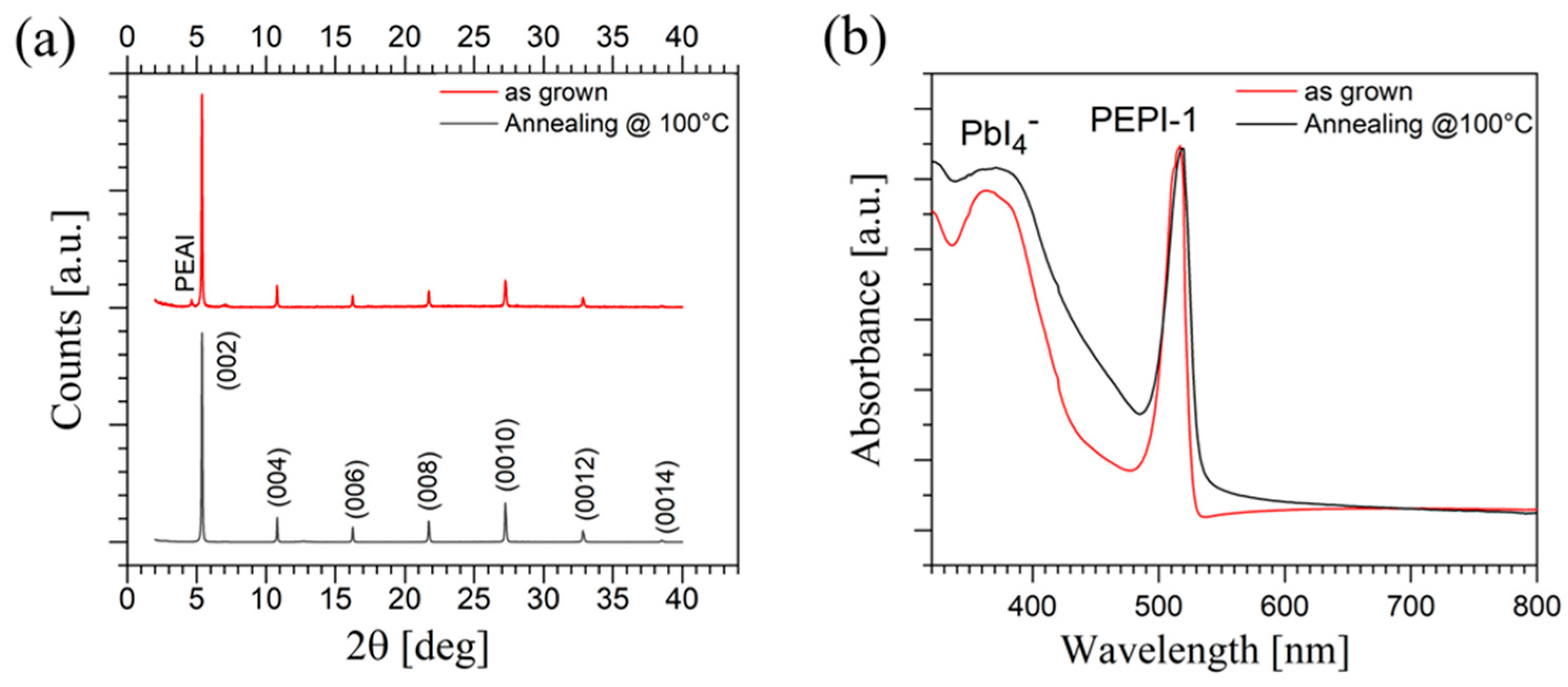

2.3. X-Ray Characterization

2.4. Optical Characterization

3. Exfoliated Flakes and Ultra-Thin Films

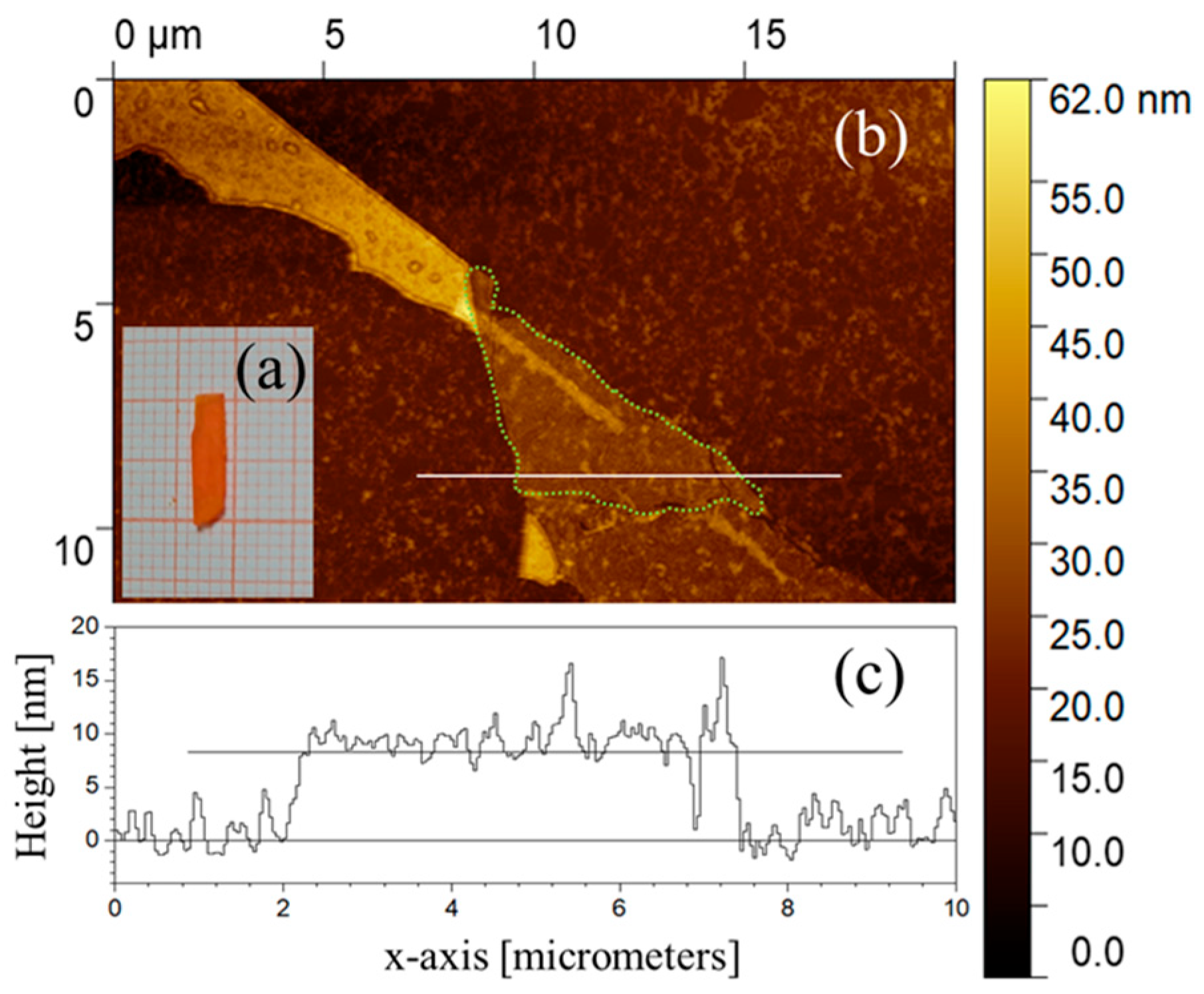

3.1. Mechanically Exfoliated Flakes

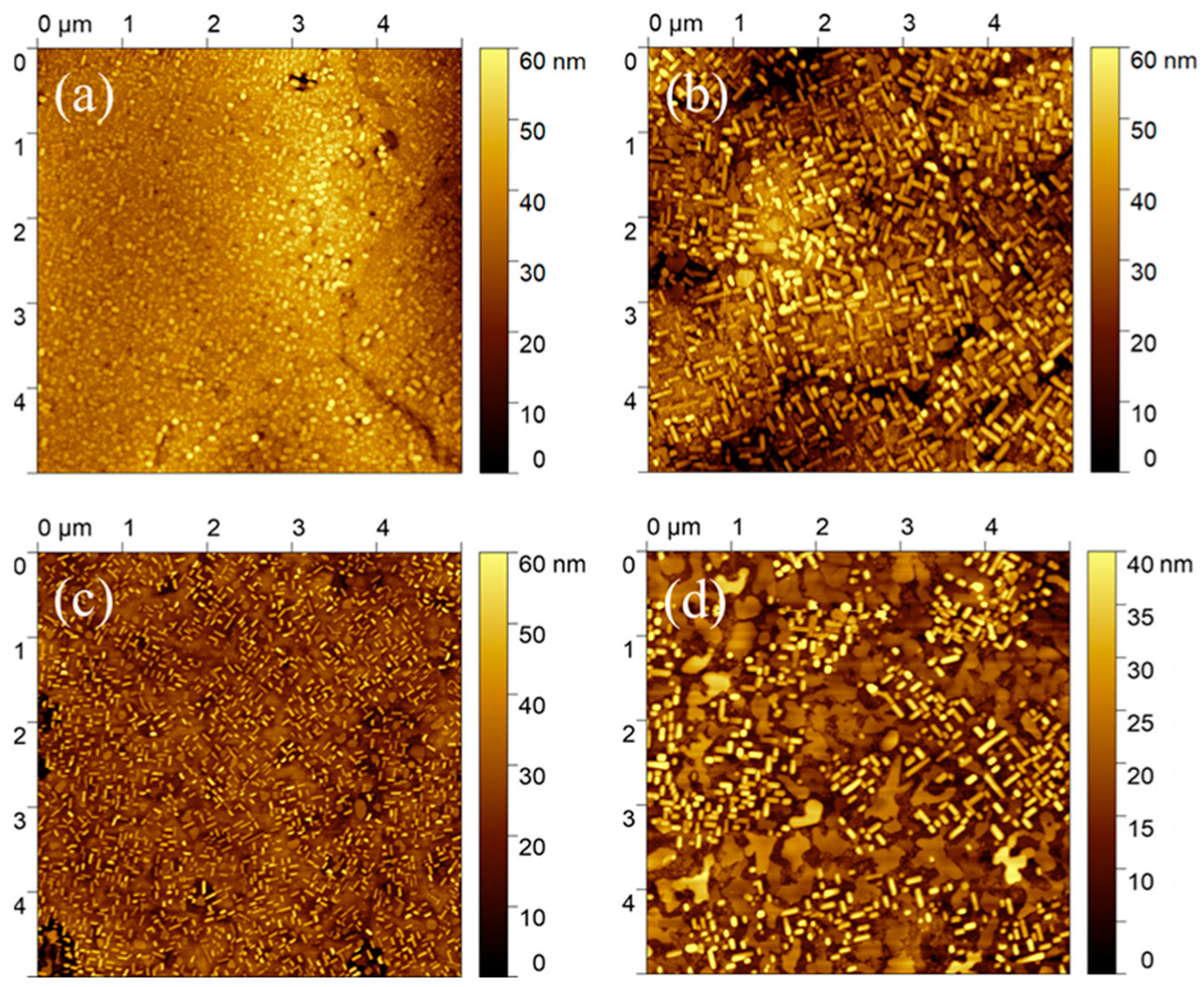

3.2. Spin Coating Thin and Ultra-Thin Films

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiarella, F.; Zappettini, A.; Licci, F.; Borriello, I.; Cantele, G.; Ninno, D.; Cassinese, A.; Vaglio, R. Combined experimental and theoretical investigation of optical, structural, and electronic properties of CH3NH3SnX3 thin films (X = Cl,Br). Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 045129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, B.; Lu, D.; Wang, T.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; Dong, X.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, N.; Fu, Q.; et al. Ultralong carrier lifetime exceeding 20 µs in lead halide perovskite film enable efficient solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2212126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.-W.; Jung, H.S.; Shin, H.; Park, N.-G. High-Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7867–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Reo, Y.; Park, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, A.; Noh, Y.-Y. Fabrication of high-performance tin halide perovskite thin-film transistors via chemical solution-based composition engineering. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 20, 1915–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shooshtari, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Pahlavan, S.; Rivera-Sierra, G.; Jiménez Través, M.; Serrano-Gotarredona, T.; Bisquert, J.; Linares-Barranco, B. Advancing Logic Circuits with Halide Perovskite Memristors for Next-Generation Digital Systems. SmartMat 2025, 6, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Liu, C.-K.; Loi, H.-L.; Yan, F. Perovskite-Based Phototransistors and Hybrid Photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1903907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Anaya, M.; Abfalterer, A.; Stranks, S.D. Halide Perovskite Light-Emitting Diode Technologies. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2002128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Leaños, A.L.; Cortecchia, D.; Saggau, C.N.; Martani, S.; Folpini, G.; Feltri, E.; Albaqami, M.D.; Ma, L.; Petrozza, A. Lasing in Two-Dimensional Tin Perovskites. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 20671–20679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.M.; Teuscher, J.; Miyasaka, T.; Murakami, T.N.; Snaith, H.J. Efficient Hybrid Solar Cells Based on Meso-Superstructured Organometal Halide Perovskites. Science 2012, 338, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitzi, D.B. Progress in Inorganic Chemistry; Karlin, K.D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 48. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, R.; Paul, G.; Pal, A.J. Quantum Confinement and Dielectric Deconfinement in Quasi-Two-Dimensional Perovskites: Their Roles in Light-Emitting Diodes. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2022, 17, 054045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, O.; Chernikov, A.; Norman, Z.M.; Zhong, Y.; Velauthapillai, A.; van der Zande, A.; Owen, J.S.; Heinz, T.F. Excitons in ultrathin organic-inorganic perovskite crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 045414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, M.; Magdaleno, A.J.; Alcázar-Cano, N.; Meléndez, M.; Lubbers, T.J.; Walraven, S.W.; Pakdel, S.; Prada, E.; Delgado-Buscalioni, R.; Prins, F. Exciton diffusion in two-dimensional metal-halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Two-Dimensional Hybrid Halide Perovskites: Principles and Promises. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Li, H.; Aladamasy, M.H.; Frasca, C.; Abate, A.; Zhao, K.; Hu, Y. Advances in the Synthesis of Halide Perovskite Single Crystals for Optoelectronic Applications. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2683–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fateev, S.A.; Petrov, A.A.; Ordinartsev, A.A.; Grishko, A.Y.; Goodilin, E.A.; Tarasov, A.B. Universal strategy of 3D and 2D hybrid perovskites single crystal growth via in situ solvent conversion. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 9805–9812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, M.; Abdellah, M.; Pullerits, T.; Zheng, K.; Liang, Z. Implementing an intermittent spin-coating strategy to enable bottom-up crystallization in layered halide perovskites. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muddam, R.S.; Wang, S.; Raj, N.P.M.J.; Wang, Q.; Wijesinghe, P.; Payne, J.; Dyer, M.S.; Bowen, C.; Jagadamma, L.K. Self-Poled Halide Perovskite Ruddlesden-Popper Ferroelectric-Photovoltaic Semiconductor Thin Films and Their Energy Harvesting Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2425192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La-Placa, M.G.; Gil-Escrig, L.; Guo, D.; Palazon, F.; Savenije, T.J.; Sessolo, M.; Bolink, H.J. Vacuum-Deposited 2D/3D Perovskite Heterojunctions. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2893–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, H.A.; White, L.R.W.; De Luca, D.; Ahmad, R.; Bruno, A. Thermally Evaporated Metal Halide Perovskites for Optoelectronics. ACS Appl. En. Mater. 2025, 8, 7769–7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, F.; Ferro, P.; Licci, F.; Barra, M.; Biasiucci, M.; Cassinese, A.; Vaglio, R. Preparation and transport properties of hybrid organic–inorganic CH3NH3SnBr3 films. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 86, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hong, E.; Zhang, X.; Deng, M.; Fang, X. Perovskite-Type 2D Materials for High-Performance Photodetectors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lin, G.; Xiong, X.; Zhou, W.; Luo, H.; Li, D. Fabrication of single phase 2D homologous perovskite microplates by mechanical exfoliation. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Chaturvedi, A.; Zhou, J.; Hu, P.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Ultrathin Ruddlesden–Popper Perovskite Heterojunction for Sensitive Photodetection. Small 2019, 15, 1902890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Deschler, F.; Gao, S.; Friend, R.H.; Cheetham, A.K. Chemically diverse and multifunctional hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Li, D. Robust Interlayer Coupling in Two-Dimensional Perovskite/Monolayer Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Heterostructures. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 10258–10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Blancon, J.C.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wong, J.; Yan, E.; Lin, Y.R.; Crochet, J.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Jariwala, D.; et al. Giant Enhancement of Photoluminescence Emission in WS2-Two-Dimensional Perovskite Heterostructures. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 4852–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, R.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yong, J.Z.; Yu Wong, C.P.; Eda, G.; et al. Optoelectronic Properties of a van der Waals WS2 Monolayer/2D Perovskite Vertical Heterostructure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 45235–45242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, X.; Zheng, B.; Qi, Z.; Ma, C.; Fu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Hautzinger, M.P.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Ultrahigh-Performance Optoelectronics Demonstrated in Ultrathin Perovskite-Based Vertical Semiconductor Heterostructures. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7996–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lai, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, W. Van der Waals MoS2/Two-Dimensional Perovskite Heterostructure for Sensitive and Ultrafast Sub-Band-Gap Photodetection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 3356–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Yin, J.; Ho, K.-T.; Ouellette, O.; De Bastiani, M.; Murali, B.; El Tall, O.; Shen, C.; Miao, X.; Pan, J.; et al. Ultralow Self-Doping in Two-dimensional Hybrid Perovskite Single Crystals. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4759–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, K.-Z.; Tu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Zauscher, S.; Mitzi, D.B. Two-Dimensional Lead(II) Halide-Based Hybrid Perovskites Templated by Acene Alkylamines: Crystal Structures, Optical Properties, and Piezoelectricity. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 9291–9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadio, A.; Sabino, F.P.; Freitas, A.L.M.; Felez, M.R.; Dalpian, G.M.; Souza, J.A. Comparing the Cubic and Tetragonal Phases of MAPbI3 at Room Temperature. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 7533–7544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesuele, F.; Nivas, J.J.; Fittipaldi, R.; Altucci, C.; Bruzzese, R.; Maddalena, P.; Amoruso, S. Analysis of Nascent Silicon Phase-Change Gratings Induced by Femtosecond Laser Irradiation in Vacuum. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahil, M.; Ansari, R.M.; Prakash, C.; Islam, S.S.; Dixit, A.; Ahmad, S. Ruddlesden–Popper 2D Perovskites of Type (C6H9C2H4NH3)2(CH3NH3)n−1PbnI3n+1 (n = 1–4) for Optoelectronic Applications. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Connor, B.A.; Karunadasa, H.I. Tuning the Luminescence of Layered Halide Perovskites. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3104–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoumpos, C.C.; Soe, C.M.M.; Tsai, H.; Nie, W.; Blancon, J.-C.; Cao, D.H.; Liu, F.; Traoré, B.; Katan, C.; Even, J.; et al. High Members of the 2D Ruddlesden-Popper Halide Perovskites: Synthesis, Optical Properties, and Solar Cells of (CH3(CH2)3NH3)2(CH3NH3)4Pb5I16. Chem 2017, 2, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splendiani, A.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Kim, J.; Chim, C.Y.; Galli, G.; Wang, F. Emerging Photoluminescence in Monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, W.; Eiden, A.; Prakash, G.V.; Baumberg, J.J. Exfoliation of self-assembled 2D organic inorganic perovskite semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 171111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, G.; Xi, X.; Yang, G.; Hu, L.; Zhu, B.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Annealing Engineering in the Growth of Perovskite Grain. Crystals 2022, 12, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamied, M.M.; Song, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Long, H.; Wang, K.; Wang, B.; Lu, P. Improved photoemission and stability of 2D organic-inorganic lead iodide perovskite films by polymer passivation. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 42LT01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, K.; Dhami, T.S. Optical absorption spectra of lead iodide nanoclusters. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 13055–13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciccarelli, F.; Barra, M.; Carella, A.; De Luca, G.M.; Gesuele, F.; Chiarella, F. 2D Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Hybrid Heterostructures: Single Crystals, Thin Films and Exfoliated Flakes. Crystals 2025, 15, 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121024

Ciccarelli F, Barra M, Carella A, De Luca GM, Gesuele F, Chiarella F. 2D Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Hybrid Heterostructures: Single Crystals, Thin Films and Exfoliated Flakes. Crystals. 2025; 15(12):1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121024

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiccarelli, Fabrizio, Mario Barra, Antonio Carella, Gabriella Maria De Luca, Felice Gesuele, and Fabio Chiarella. 2025. "2D Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Hybrid Heterostructures: Single Crystals, Thin Films and Exfoliated Flakes" Crystals 15, no. 12: 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121024

APA StyleCiccarelli, F., Barra, M., Carella, A., De Luca, G. M., Gesuele, F., & Chiarella, F. (2025). 2D Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Hybrid Heterostructures: Single Crystals, Thin Films and Exfoliated Flakes. Crystals, 15(12), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15121024