Abstract

As a functional coating, the wear-resistant Cr coating is of considerable importance in metal plating. In the present paper, S235 steel samples were electrodeposited with 5 µm thick Cr coating at current densities of 15, 27 and 40 A dm−2. Nanoindentation was performed to measure the hardness of samples with electroplated Cr coating. Under the defined electroplating process conditions, the Cr coating hardness varied as a function of current density: the minimum average HIT value of 11.4 GPa was measured at a current density of 15 A dm−2 and the maximum average HIT value of 12.9 GPa was measured at 40 A dm−2. Tribological characteristics of coated samples were determined using the ball-on-disc tribo-method with surface evaluation of tribo-track on the confocal and electron microscope. The Cr coating deposited at 15 A dm−2 had the lowest wear resistance with a wear rate of 12.76 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1. The Cr coating deposited at 40 A dm−2 had the highest wear resistance on the sample with a wear rate of 3.84 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1.

1. Introduction

Over the last years, electrodeposition procedures have repeatedly demonstrated the variability of material selection to form coatings on different material surfaces. Various metals and alloys can be electroplated to improve product durability, resistance to wear and corrosion, and overall aesthetic appearance [1,2]. Electrolytic deposition using direct current (DC electroplating) has many advantages, which makes it one of the most widely used deposition procedures in research and industry [1,3]. This is due to the low cost, technological process speed, possibility to coat different substrates, controlled alloy composition, purity of produced coatings and obtaining of a structure ranging from micrometers to nanometers [4,5,6].

Chrome plating offers a number of advantages that make it the preferred choice in many industrial applications. Chrome plating has quickly evolved into a widely used industrial process. The main reason for this is its excellent surface properties: such as high hardness coupled with high wear resistance, resistance to moisture, chemicals and other corrosive agents [7]. Chromium has excellent thermal stability, enabling hard chrome-plated surfaces to withstand elevated temperatures without degradation or loss of functional properties [8]. Furthermore, hard chromium demonstrates remarkable resistance to atmospheric corrosion [9] and tribocorrosion [10] and exhibits good corrosion resistance in diverse environments such as citric acid, nitric acid, sodium chloride, and copper sulfate solutions [11]. According to Alemayehu A. et al. [12] Cr-based coatings can be considered as a long-term solution to problems of high-temperature corrosion on the heat-exchange walls of boiler pressure parts. According to their research, low carbon steel (ASTM A283GC mild steel) was the most susceptible to corrosion, while chromium-plated steel had the highest resistance to hot corrosion at tested temperatures (from 200 to 800 °C).

Cr coating finds its use not only in the energetic industry, but also in aerospace, automotive, chemical and electrical industries, fluid energetic, mining, tool and mould coating applications. Chrome plating is also an effective method for repairing and reconditioning of worn or damaged components [13].

Traditional hard chrome plating methods can have a significant environmental impact if not properly managed. As stated in the document [14] Cr(VI) is highly toxic and carcinogenic and poses serious health risks. The use of Cr(VI) compounds has been restricted and strictly regulated in the EU since September 2017. However, specific applications, including hard chrome plating, remain exempt under controlled conditions and temporary authorizations.

In its statement [15], the European Chemicals Agency proposed to apply a ban on Cr(VI) substances, except for categories such as electroplating on plastic substrate, electroplating on metal substrate, use of primers and other slurries, other surface treatments, and others, if they meet defined limits for worker exposure and emissions to the environment.

The changing nature of industry is also defining new environmental solutions, leading to innovative developments in hard chrome plating. The greater the demand for high-performance surfaces, the more likely it is that hard chrome plating facilities will be equipped with new techniques and technologies addressing environmental concerns while providing industrial clients with high-quality, consistent products [16,17].

As outlined, due to its good wear resistance, Cr coating is a material used in various industrial applications [10]. The effect of Cr coating on its wear behavior depends on the initial surface condition of coated material. The wear is controlled by the formation and stability of the tribo-layer formed during the contact between the surfaces of the tribo-pair [18,19]. The tribo-layer represents a mechanically mixed layer composed of materials originating from both sliding counterparts—the body and the counter body. When tribo-layers are present on the worn surfaces, particularly those differing in composition from the base metallic alloy, changes in their wear behavior can be expected. Since tribo-oxides inevitably form under atmospheric conditions, the tribo-layers formed at higher current densities, which lead to increased hardness and improved wear resistance, are generally referred to as tribo-oxide layers [20].

The aim of this study was to analyze the effect of current density during the electrodeposition of Cr coatings on their mechanical and tribological properties. A detailed analysis enabled the identification of specific areas of surface damage and provided a comprehensive description of the wear nature and extent. This approach contributed to a better understanding of the wear mechanisms of Cr coatings produced under different deposition parameters. It is hypothesized that an increase in current density leads to higher hardness and enhanced wear resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

As experimental material, samples with electroplated Cr coating were used. The Cr coating was deposited on the S235 steel substrate. The chemical composition of steel is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of S235 steel according to EN 10025-2/04 [21].

S235 steel is classified as an unalloyed structural steel with a defined yield strength of 235 MPa. The substrate surface was prepared by a standard grinding process using a ceramic wheel to achieve a surface roughness of Ra 0.5–0.6 μm. For the degreasing process, an alkaline industrial detergent was applied manually and subsequently rinsed with deionized (DI) water.

According to [22], grinding is one of the most widely used substrate mechanical pre-treatment prior to electroplating under operating conditions. Individual steel samples were connected to a DC electric current source and immersed in electrolyte. The electrolyte composition with the main components concentrations is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Electrolyte composition.

The role of H2SO4 (sulfate ions) is to act as a catalyst and activator in the chrome plating process. It promotes the reduction of Cr6+ to metallic chromium (Cr0) on the cathode during the plating process. Additives used are alkyl sulfonic acids. Their role is to increase the hardness and the number of microcracks (by inducing internal stress) in the deposited layer.

The steel samples (designated as CR15, CR27 and CR40) were electroplated with the current density values different for each sample. They did not change with time once the desired value was reached. The electroplating process parameters for preparation of individual Cr coatings for tested samples are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Electroplating parameters for steel samples.

2.2. Experimental Methods

The microstructure of the Cr coating surface was examined using a TESCAN VEGA scanning electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV. The surface morphology was revealed and visualized by acid etching and polishing with an OP-U suspension.

Surface micro geometry, represented by the Ra value (mean arithmetic profile deviation according to ISO 21920-3 [23]) for the surfaces of samples CR15, CR27 and CR40 after coating, was determined using the confocal microscope.

The nanoindentation hardness test was used to measure the hardness of 5.0 µm thick electroplated Cr. An average hardness value of HIT was obtained. An Anton Paar NHT2 (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) device was used to measure hardness H (in GPa). A Berkovich indenter (Antor Paar TriTec SA, Corcelles, Switzerland) was used, with a maximum load of 20 mN (in order to maintain the penetration depth of maximum 10% of the thickness of the Cr coating). The evaluation of the measurements was carried out according to the Oliver and Pharr method [24]. for samples at temperatures of 23 °C (RT) In all measurements, the load lasted for a maximum value of 20 s, holding time at peak load 5 s and unloading time 20 s.

The tribological characteristics of samples with galvanic Cr obtained at different current densities were determined using the ball-on-disc method on the Bruker UMT-3 Tribometer. The test specimen was a 6 mm diameter ball, which was made of 100 Cr6 material (W.1.3505). The ball hardness was 714 HV0.5. The tribo-test parameters are given in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ball-on-disc test parameters on Tribometer Brucker UMT-3.

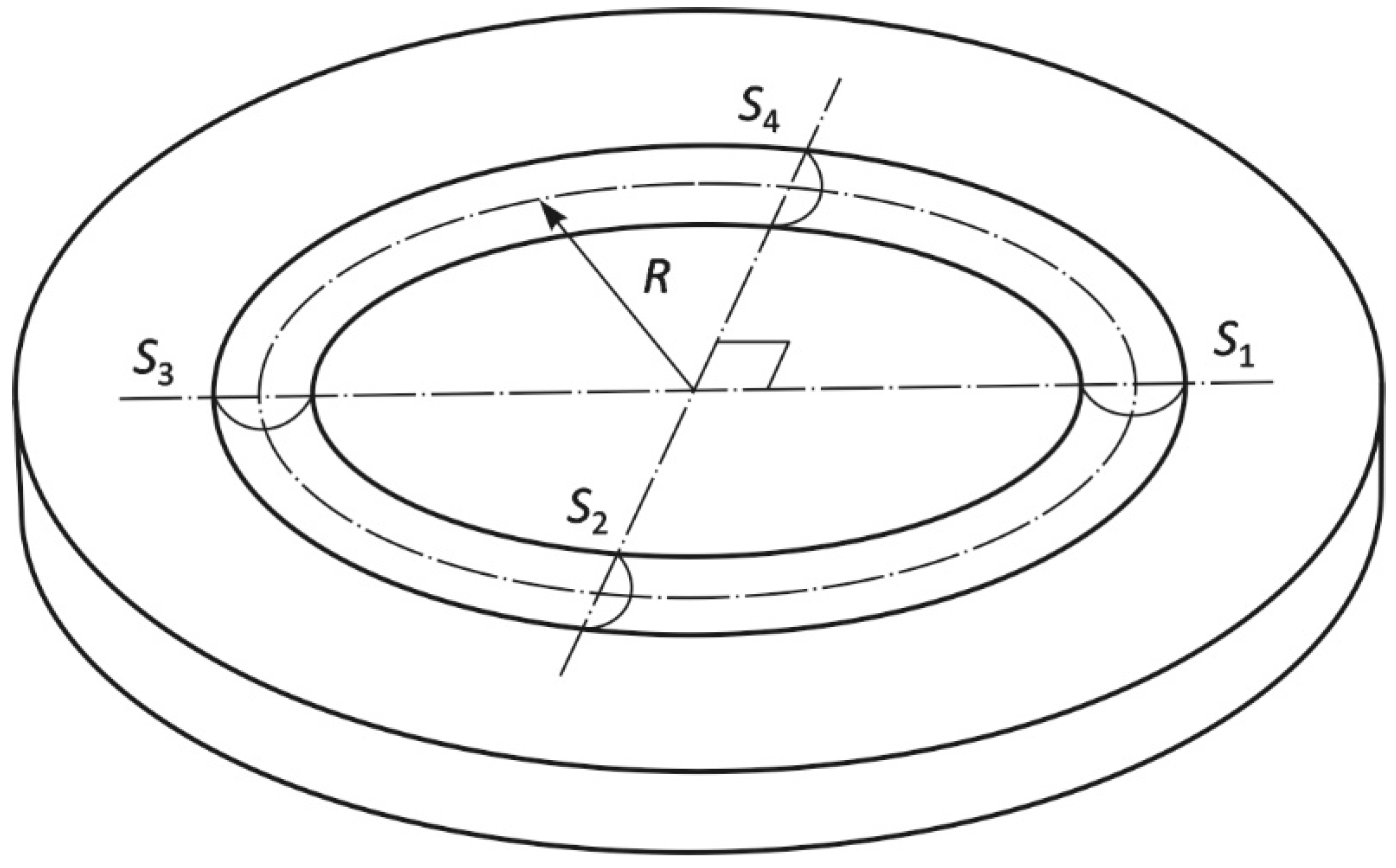

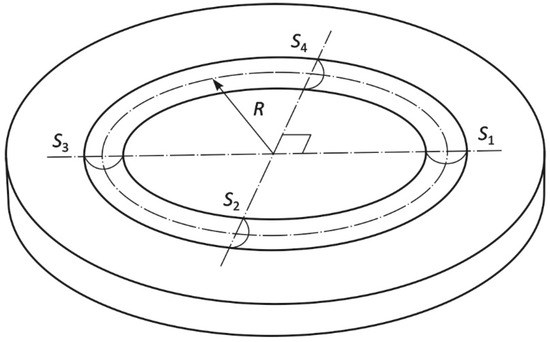

The electroplated Cr coating surface was analyzed by the Neox PLu Sensofar (Sensofar, Barcelona, Spain) confocal microscope after the ball-on-disc test. Based on the obtained topography of tribological track, it was possible to determine not only the maximum depth of the track, but also the size of the four cross-sectional areas required for calculation of the volume loss (m3) from the equation:

where R is radius of the tribological track (m), S1 to S4 are four cross-sectional areas on the tribological track (m2). Using the volume loss, magnitude of the pressing force and length of the test specimen path, the wear rate w (m3 (Nm)−1) was calculated according to the equation:

where, Vdisc is volume loss from the tested sample surface (m3), L is the specimen path (m), Fp is force applied to the specimen (N) [25,26].

Figure 1 shows the scheme with marked analyzed areas S1–S4 according to ISO 20808 [27]. Fine ceramics (advanced ceramics, advanced technical ceramics)—Determination of friction and wear characteristics of monolithic ceramics by ball-on-disc method [27]. The cross-sectional profiles of the wear track were measured at four positions (S1–S4), spaced 90° apart, using a contact stylus profilometer or similar instrument.

Figure 1.

Scheme with marked analyzed areas S1–S4.

Surface evaluation included documentation of the tribo-track and its analysis using the ZEISS EVO MA15 scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and EDS analysis with the Oxford Instruments X-Max analyzer (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK).

3. Results and Discussion

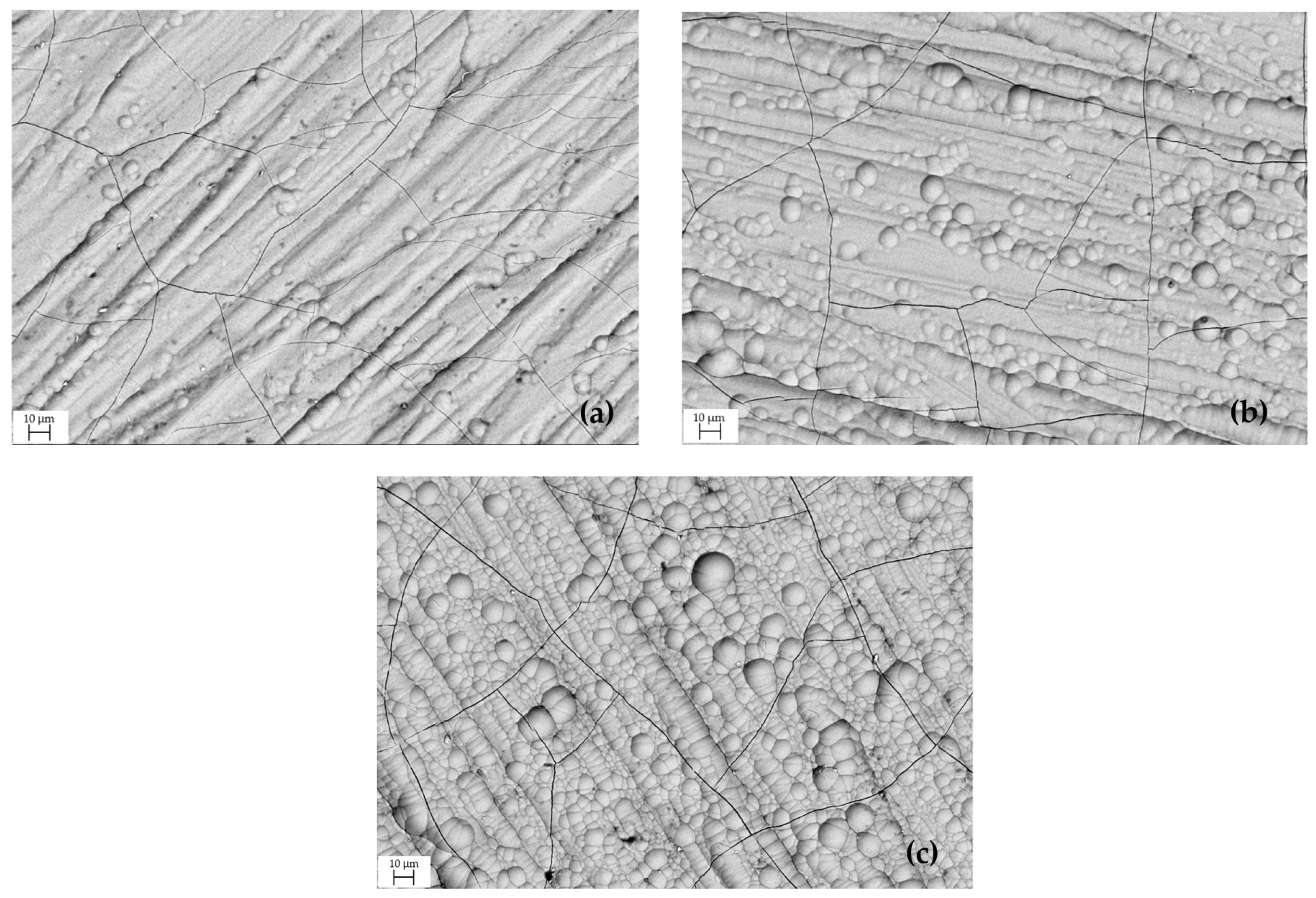

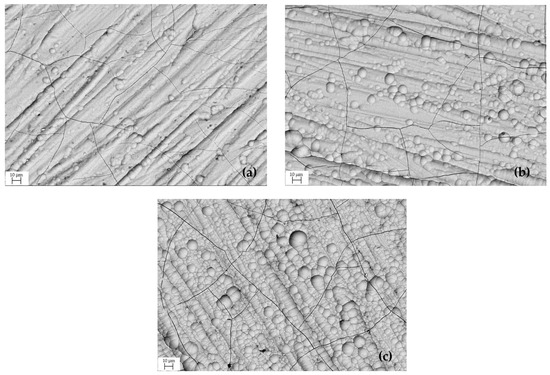

SEM characterization was performed to analyze the surface morphology of Cr coatings deposited at galvanic process current densities 15, 27 and 40 A dm−2, Figure 2. The hard chromium layer was formed on the steel substrate at a high nucleation rate, which led to the formation of spheres. Higher current density promotes a higher rate of reactions that produce a higher number of Cr ions [28]. Cr coatings often show a highly defective surface. These defects were mainly caused by internal stress created in the coating during deposition. The microcracks are thin and shorter than the thickness of the coating [10,29,30].

Figure 2.

Surface morphology of Cr coating obtained at current density: (a) 15 A dm−2, (b) 27 A dm−2, (c) 40 A dm−2.

The adhesion of the Cr coating is significantly affected by current density. Excessive current density reduces the adhesion strength of the coating to the substrate. In combination with the long coating time, during which a large amount of H2 gas is produced at the cathode and released, this may disrupt the adhesion of Cr ions onto the coated product [28,31]. The origin of the tensile residual stress is mainly attributed to the presence of gases incorporated together with the chromium. The high level of stress is relieved by local cracking during electroplating, when the mechanical strength of the deposited Cr layer is exceeded. Cracking occurs periodically and progresses in depth, further reducing the stress in the previously deposited layers. This phenomenon is limited at the interface by the bond with the substrate and at the surface by the absence of new microcracks or their propagation [32,33].

The depth, width, and density of microcracks are influenced by several factors. The results show that the residual stress and crack networks are affected by the current density used during deposition. Coatings with high tensile residual stress tend to have low crack density. Stress relaxation is associated with the formation of microcracks and consequently with the reduction of residual stresses generated during the deposition process.

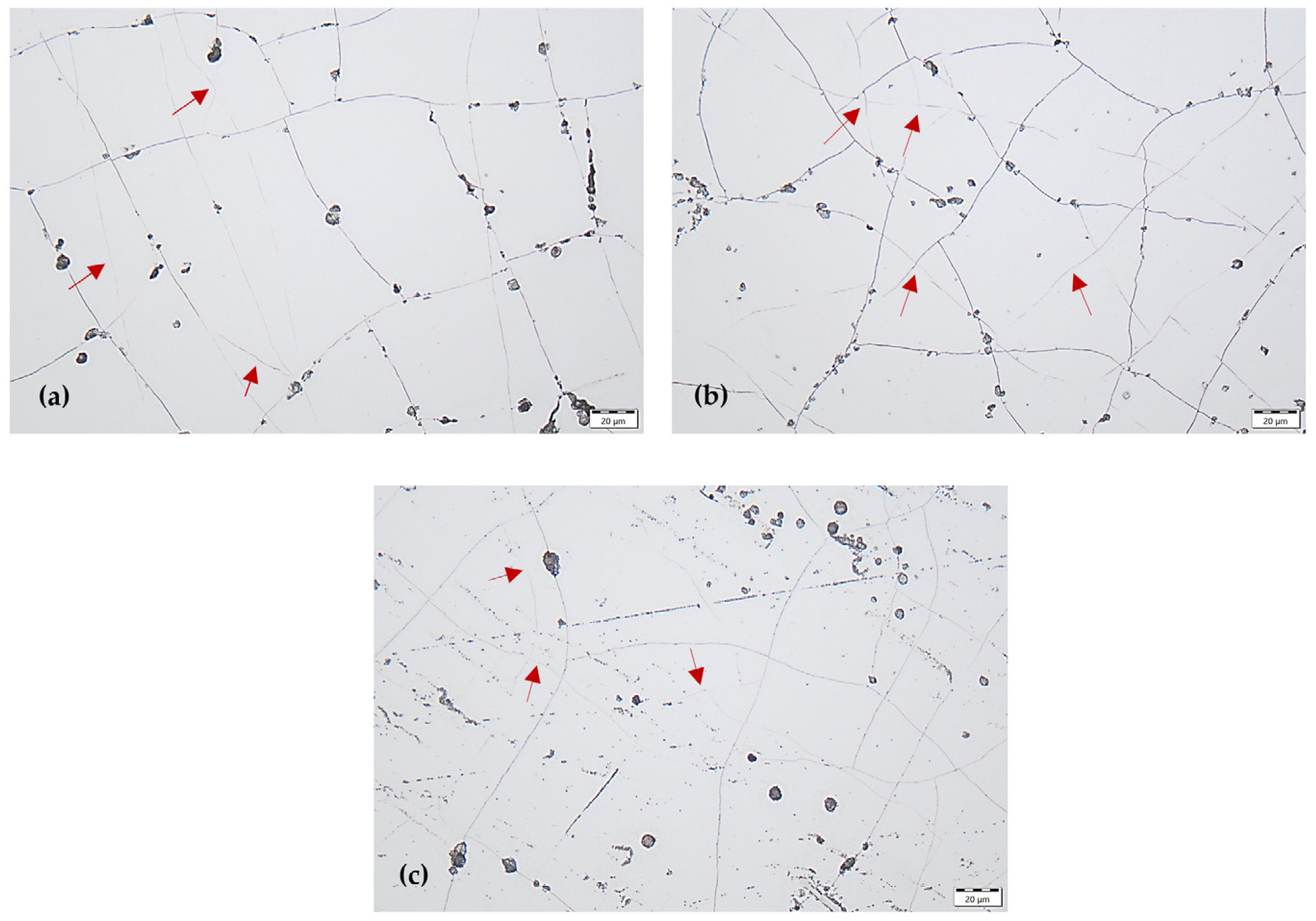

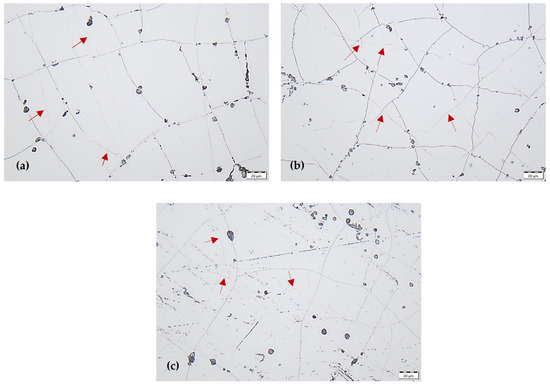

After the surface morphology was revealed by etching and polishing, surface microcracks became visible. In general, a microcrack structure with a high density of shallow, narrow microcracks is preferred, as such a Cr coating typically exhibits greater wear and corrosion resistance, improved lubricity, and lower stress [34].

The structure of the coating was also partially revealed and it was possible to identify some grain boundaries (columns boundaries) of the coating. The grain size of the Cr coating varied depending on the current density. At the lowest current density of 15 A dm−2, the largest grains were observed (some grain boundaries are indicated by arrows in Figure 3a). At the highest current density of 40 A dm−2, the Cr coating exhibited the finest-grained microstructure (some grain boundaries are indicated by arrows in Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Surface morphology of Cr coating by marking some grain boundaries with arrows, obtained at current density with: (a) 15 A dm−2, (b) 27 A dm−2, (c) 40 A dm−2.

The hardness of hard chrome is related to grain size and residual stress, and is not directly dependent on crack density [35].

The coating micro geometry has a significant influence on its tribological properties [36]. The average values of the mean arithmetic deviation of the Cr coating Ra surface profile obtained from 10 measurements on the measured section length of 15 mm are given in Table 5. The sample surface corresponds to micro geometry of the ground steel surface before Cr coating application, with a roughness of Ra = 0.5–0.6 µm. After deposition of the coating, the roughness (Ra) increased only slightly, according to Table 5. This slight increase in roughness of galvanic coatings is attributed, in this case, to the presence of Cr spheres on the surface (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Average Ra of Cr coating sample surface.

The average hardness HIT values from 10 measurements are given in Table 6. Based on the measured values, it is evident that under the defined electroplating process conditions (electrolyte temperature and composition, current density and deposition time), the Cr coating hardness increased with increasing current density. As reported by studies [37,38], higher current density affects the formation of a higher number of nucleation sites with suppression of their growth. This results in a finer structure of the electrodeposited coating with higher hardness according to the Hall-Petch relation analogy [28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Table 6.

Average values of hardness HIT Cr coatings.

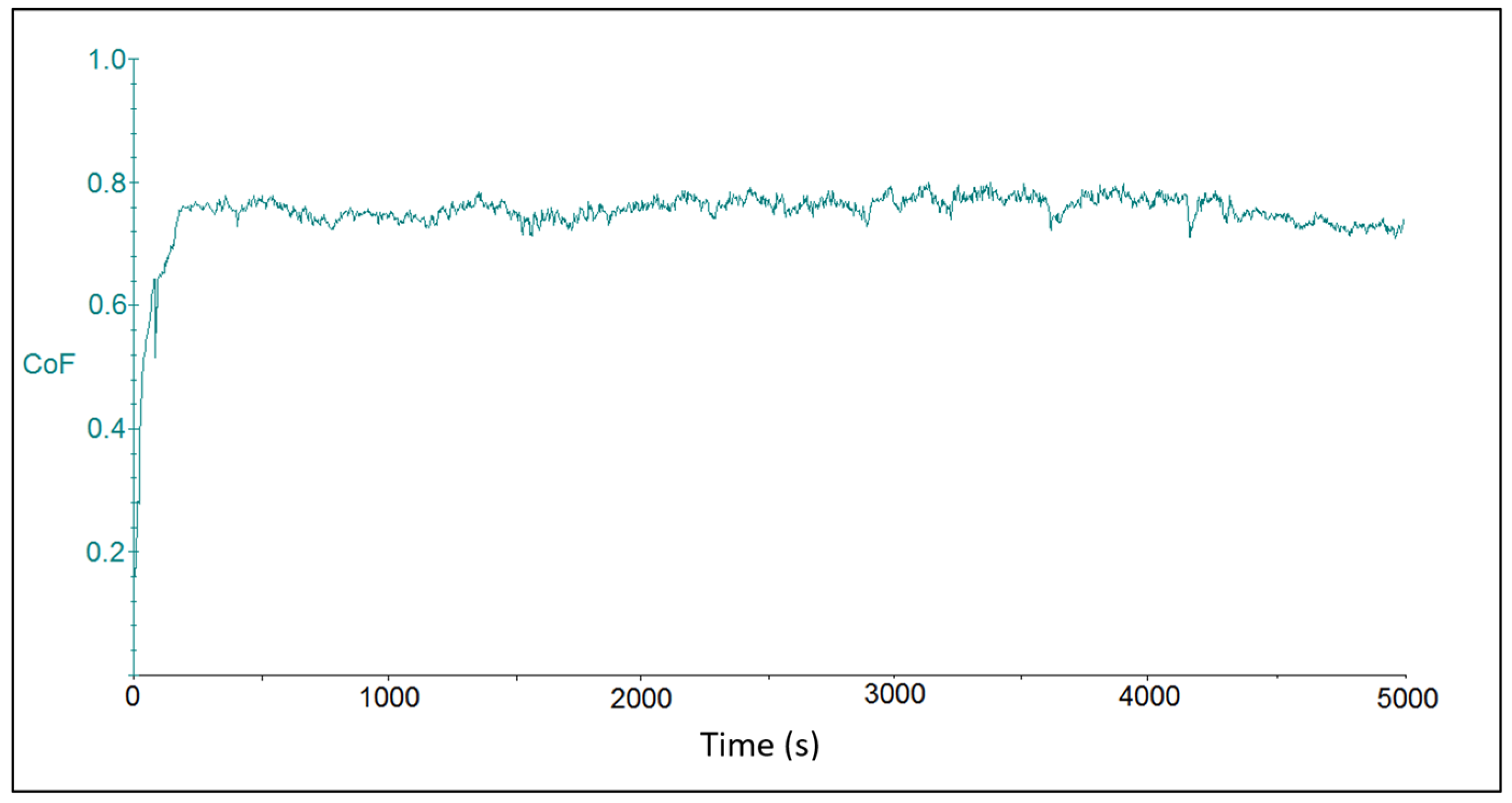

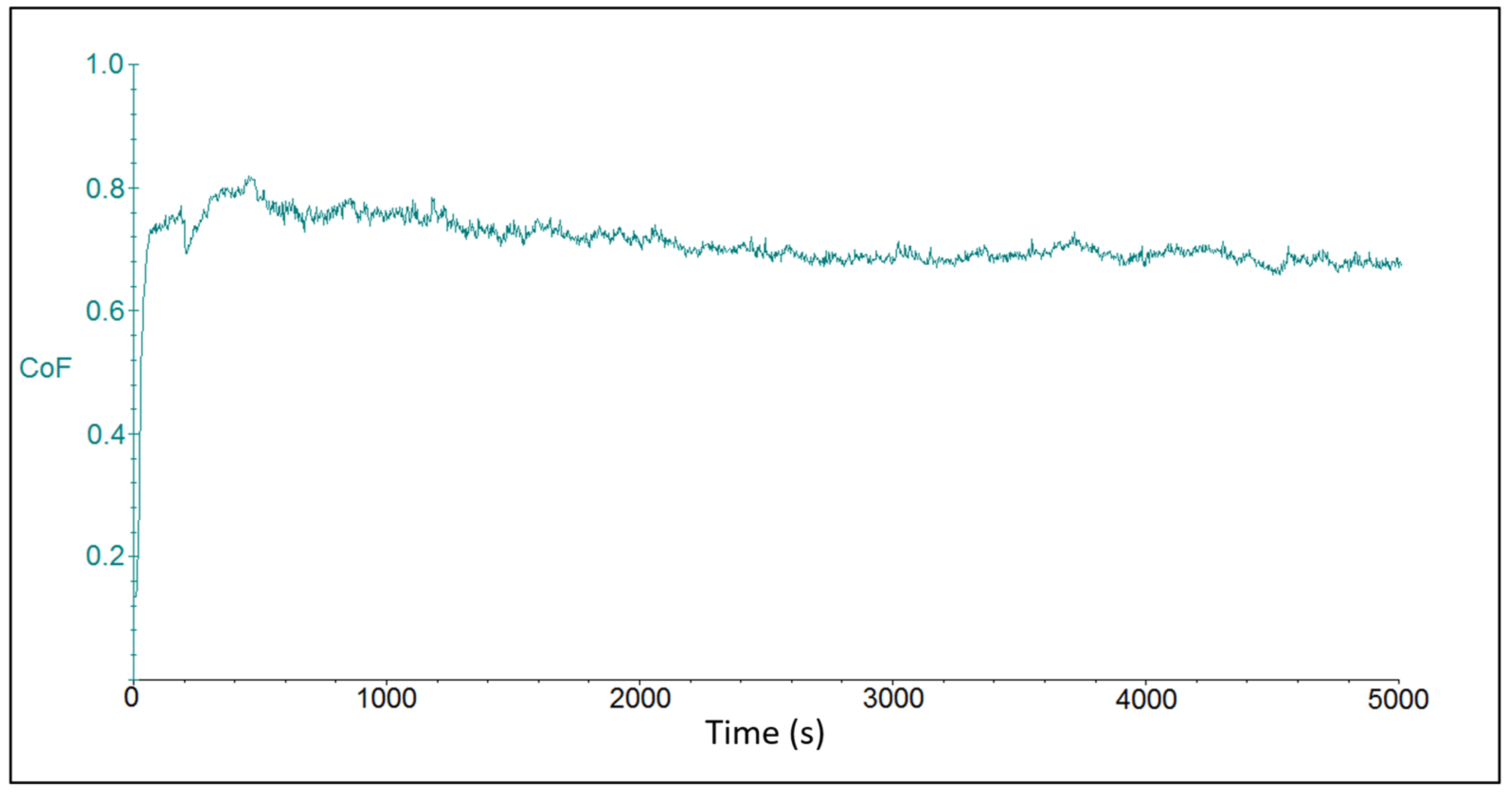

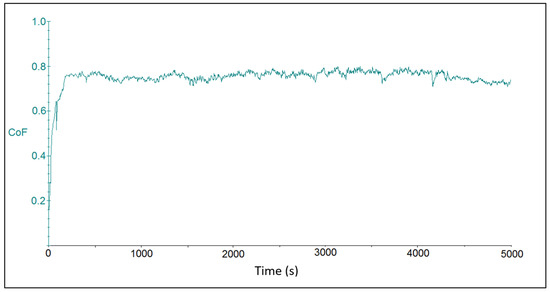

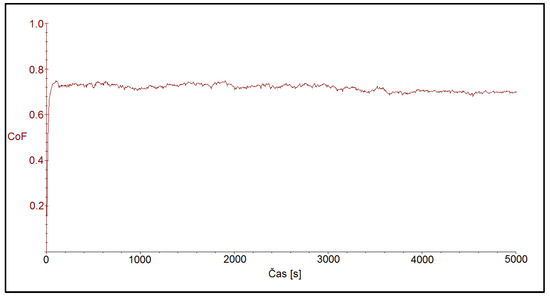

The tribotest output was represented by friction coefficient waveforms for the individual chromium coating samples. Figure 4 shows the course of the friction coefficient for sample CR15. Due to the initial material transfer, the friction coefficient increased at the beginning of the tribo-test. After a rapid increase in its value after about 100 s of the test duration, the progression continued in a more steady-state mode. The average value of the friction coefficient was at 0.726 ± 0.106. The oscillations on waves that were observed on the curve could be attributed to artifacts that resulted from elastic and plastic deformation zones on the coating surface and were related to setting of the contact force at the beginning of the tribo-test during the “micro stick-slip” motion of the ball body. The “drift effect” at the contact between the ball and the coating surface was related to elastic-plastic deformation of rough surfaces, i.e., the relative displacement was elastic (reversible) at first and then transitioned to plastic (irreversible) stage [42].

Figure 4.

Time dependence on the friction coefficient for sample CR15 with coating deposited at the current density of 15 A dm−2.

In addition to the friction coefficient, the important evaluation criteria are the depth and width of the track after the tribo-sample was applied to the coating surface and the amount of material loss after wear.

The tribo-track can be very irregular in width and depth and thus it is not always possible to give characteristics to its dimensions. The solution is to measure the track at multiple locations, and then average values can be obtained [43].

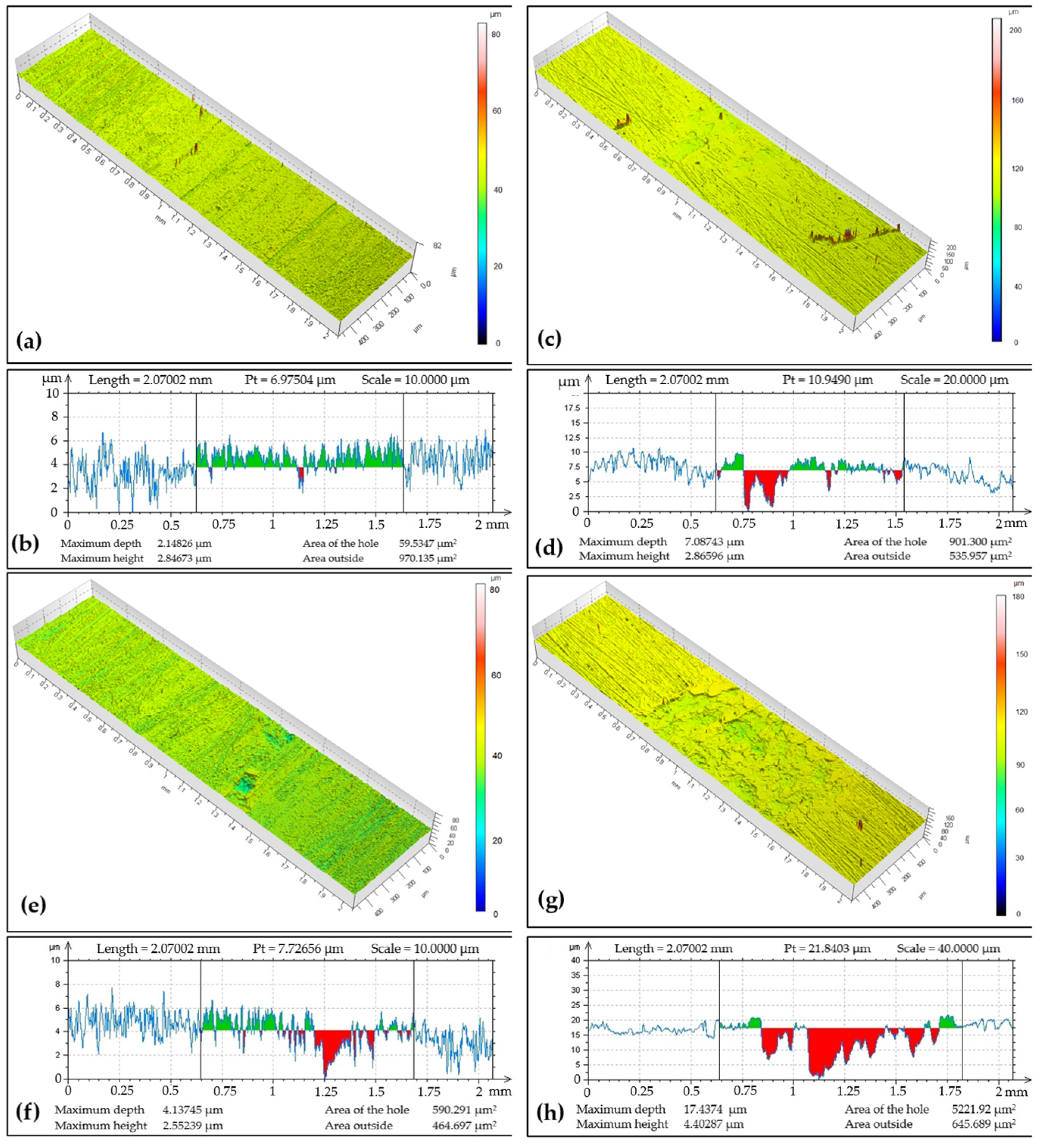

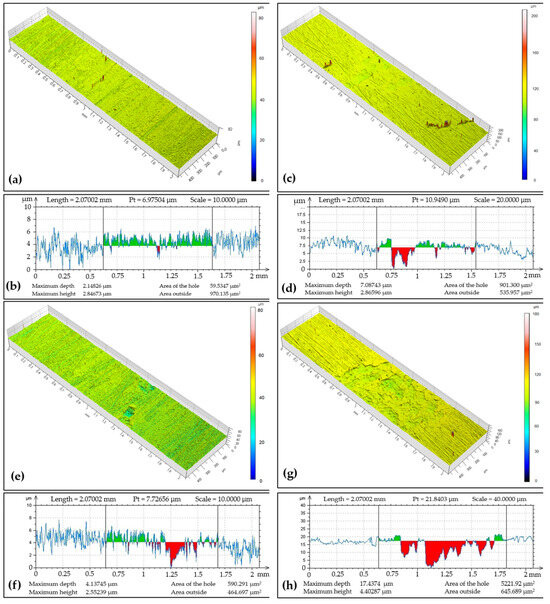

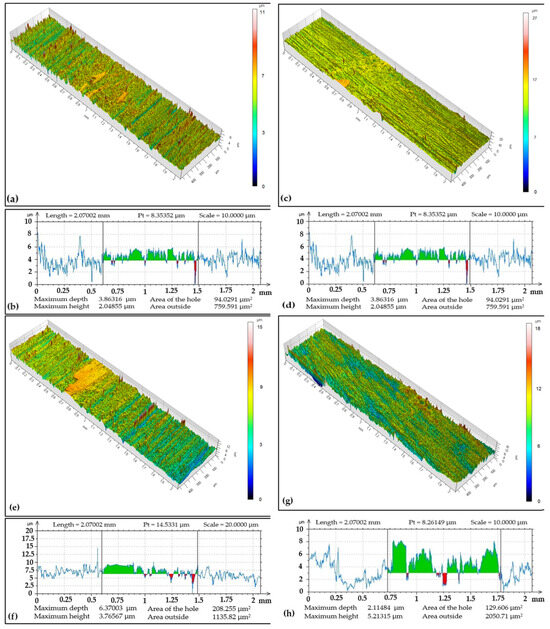

The tribo-track topography on the CR15 coating after ball-on-disc testing from four locations on its surface is documented in Figure 5. In the image, it can be seen at which point the chromium coating was lost by the force applied by the tribo-ball. The tribo-track width and max depth varied for each of the documented locations, with track widths ranging from 0.92 to 1.18 mm. The Cr coating regrinding recorded, for example, in the widest tribo-track at documented location S4, was at 17.44 µm with a cross-sectional area of 5221.92 µm2. In the narrowest documented tribo-track at location S2, the regrinding was at a level of 7.09 µm with a cross-sectional area an order of magnitude lower, namely 901.3 µm2. The wear rate was 12.76 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1.

Figure 5.

Sample CR15: (a) surface topography at cross-section point S1, (b) topographic curve from S1, (c) surface topography at cross-section point S2, (d) topographic curve from S2, (e) surface topography at cross-section point S3, (f) topographic curve from S3, (g) surface topography at cross-section point S4, (h) topographic curve from S4.

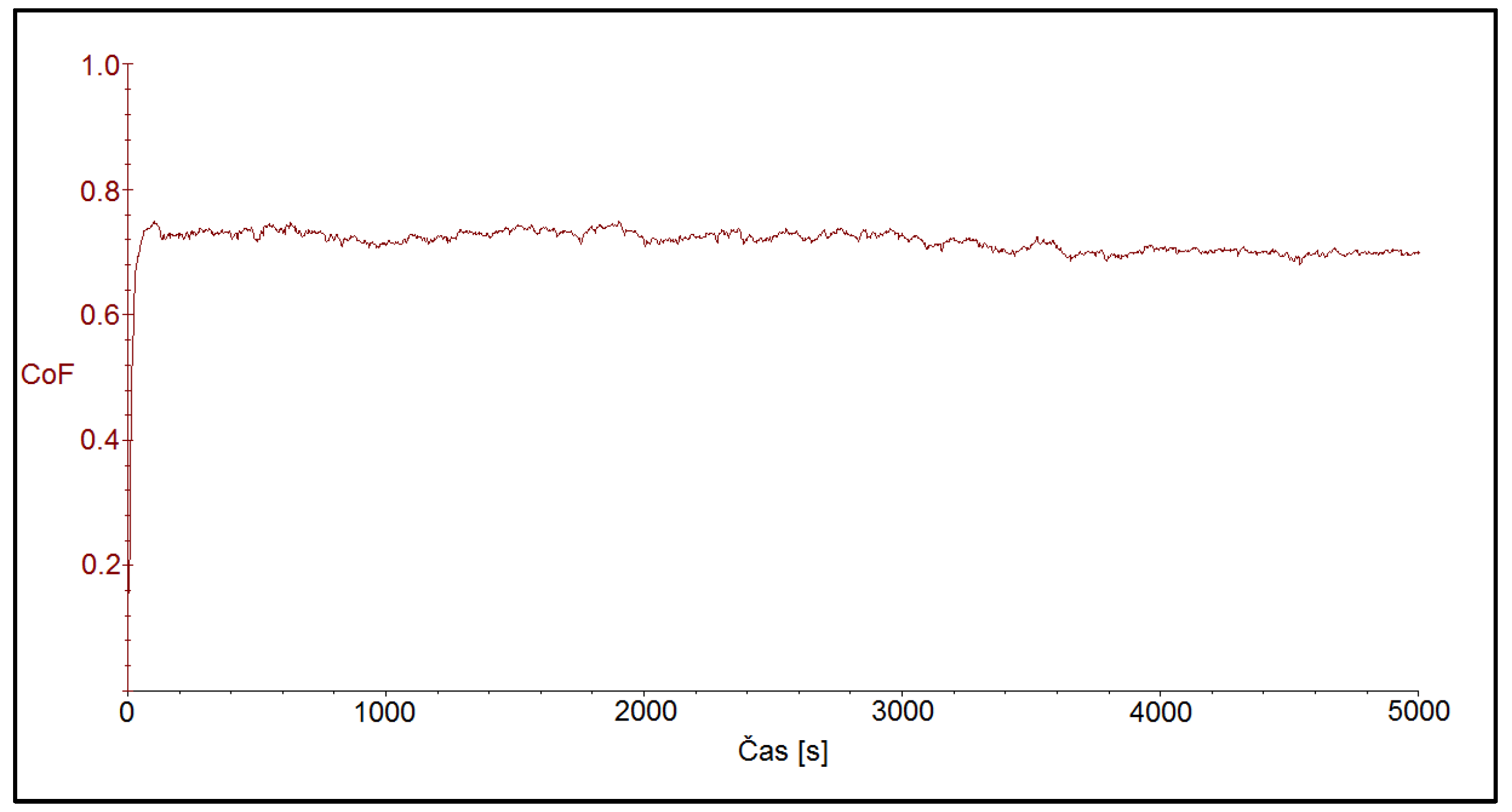

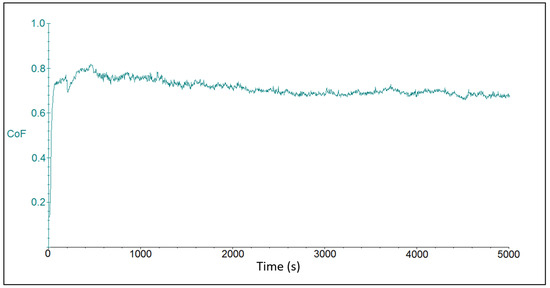

Figure 6 documents the tribo-coefficient of the CR27 sample. As in the previous case, on the CR15 coating, larger friction coefficient oscillations were visible in the first part of the test, for a longer period of about 500 s. The average friction coefficient value during the whole test was at 0.716 ± 0.152.

Figure 6.

Time dependence of friction coefficient for the CR27 sample with the coating deposited at the current density of 27 A dm−2.

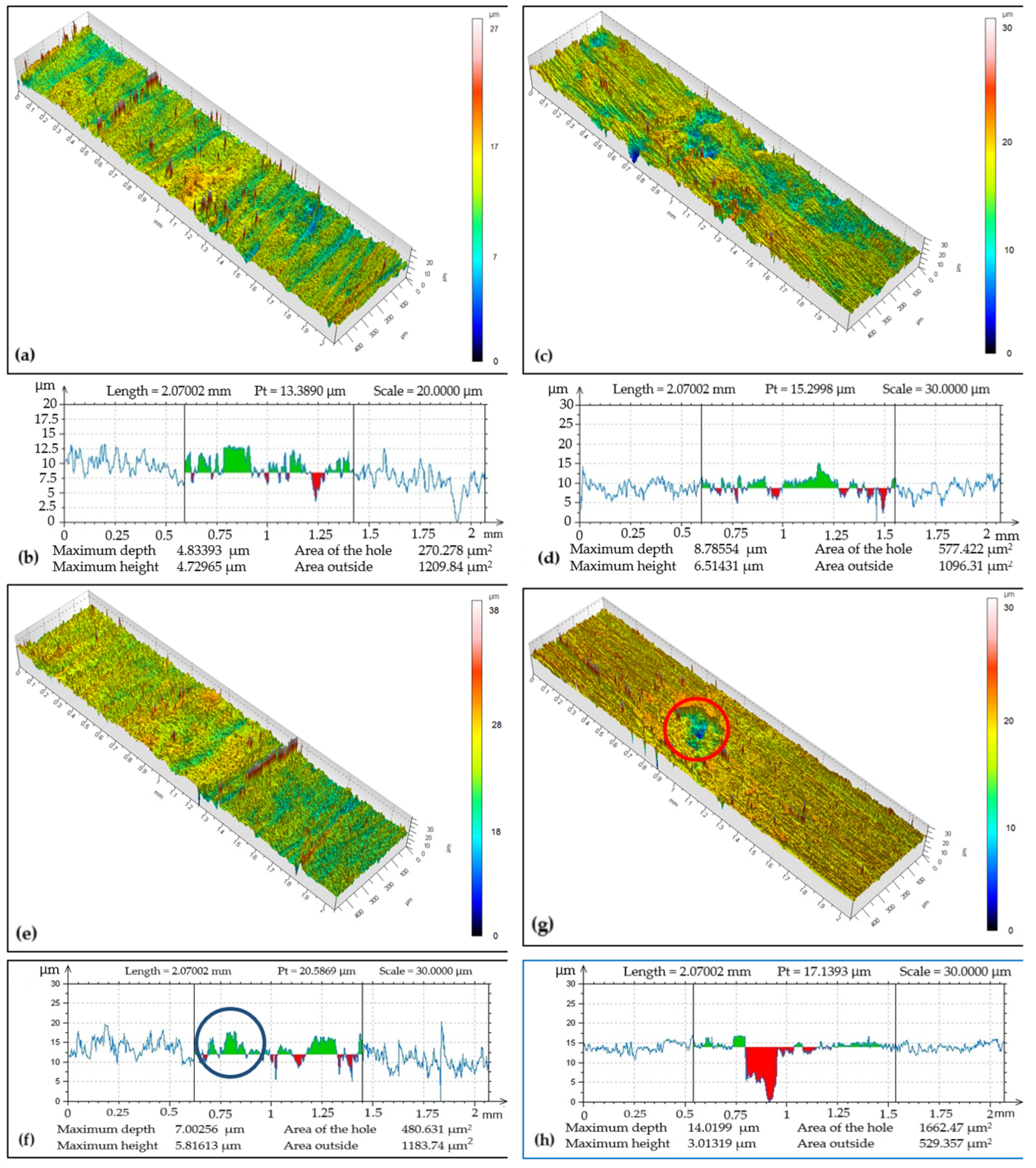

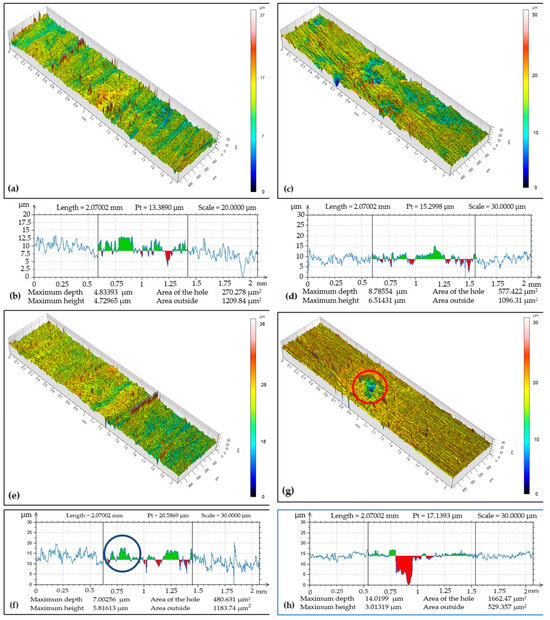

Tribo-track analysis on the CR27 coating at locations S1 to S4 of its surface in Figure 7 showed that the width and max depth of the tribo-tracks were different compared to the CR15 coating. While the track width ranged from 0.82 to 0.98 mm, the tribo-track depth reached a maximum of 14.02 µm at location S4 with a cross-sectional area of 1662.47 µm2 and a minimum of 4.83 µm at the documented location S1 with a cross-sectional area of 270.28 µm2. The wear rate was 4.80 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1. The coating was abraded down to the substrate at the analyzed locations. The cross-sectional area (red spot marked in a circle in Figure 7f) characterizes the chromium coating loss and is needed for the calculation of the volume loss w. The increase in the amount of chromium coating (green spot marked in the circle in Figure 7g) in the tribo-track is attributed to the abraded chromium coating that was transferred by the test specimen and adhered to the surface of the tribo-track during adhesive wear.

Figure 7.

Sample CR27: (a) surface topography at cross-section point S1, (b) topographic curve from S1, (c) surface topography at cross-section point S2, (d) topographic curve from S2, (e) surface topography at cross-section point S3, (f) topographic curve from S3, (g) surface topography at cross-section point S4, (h) topographic curve from S4.

Figure 8 shows the friction coefficient after ball-on-disc test on the CR40 sample. Also in this case, the start of the tribo-test was accompanied by an increase in the friction coefficient in a very short time, less than 100 s, to later steady-state values, which were at 0.710 ± 0.112.

Figure 8.

Time dependence of friction coefficient for the CR40 sample with the coating deposited at the current density of 40 A dm−2.

In this case the oscillations, compared to the CR15 and CR27 coatings, were smaller.

Contact area of the antibodies, i.e., ball and coating surface at the documented locations was in a narrower range (compared to CR15 and CR27 coatings), namely from 0.8 to 0.9 mm, Figure 9. The Cr coating regrinding to the substrate with the greatest depth of 6.37 µm occurred in the S3 area with a cross-sectional area of 208.25 µm2. The smallest track depth was 1.41 µm in the S2 area with a cross-sectional area of 191.08 µm2. The wear rate was 3.84 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1, i.e., lower compared to CR15 and CR27 coatings.

Figure 9.

Sample CR40: (a) surface topography at cross-section point S1, (b) topographic curve from S1, (c) surface topography at cross-section point S2, (d) topographic curve from S2, (e) surface topography at cross-section point S3, (f) topographic curve from S3, (g) surface topography at cross-section point S4, (h) topographic curve from S4.

After analyzing all the surface topography images and their associated curves, the volume loss (according to relation (1)) for each sample of respective electroplated Cr coating types was calculated based on the size of cross-section areas and the tribo-track radius. Using the volume loss, contact force magnitude, and the test specimen track length, the wear rate for each type of Cr coating was obtained (according to relation (2)).

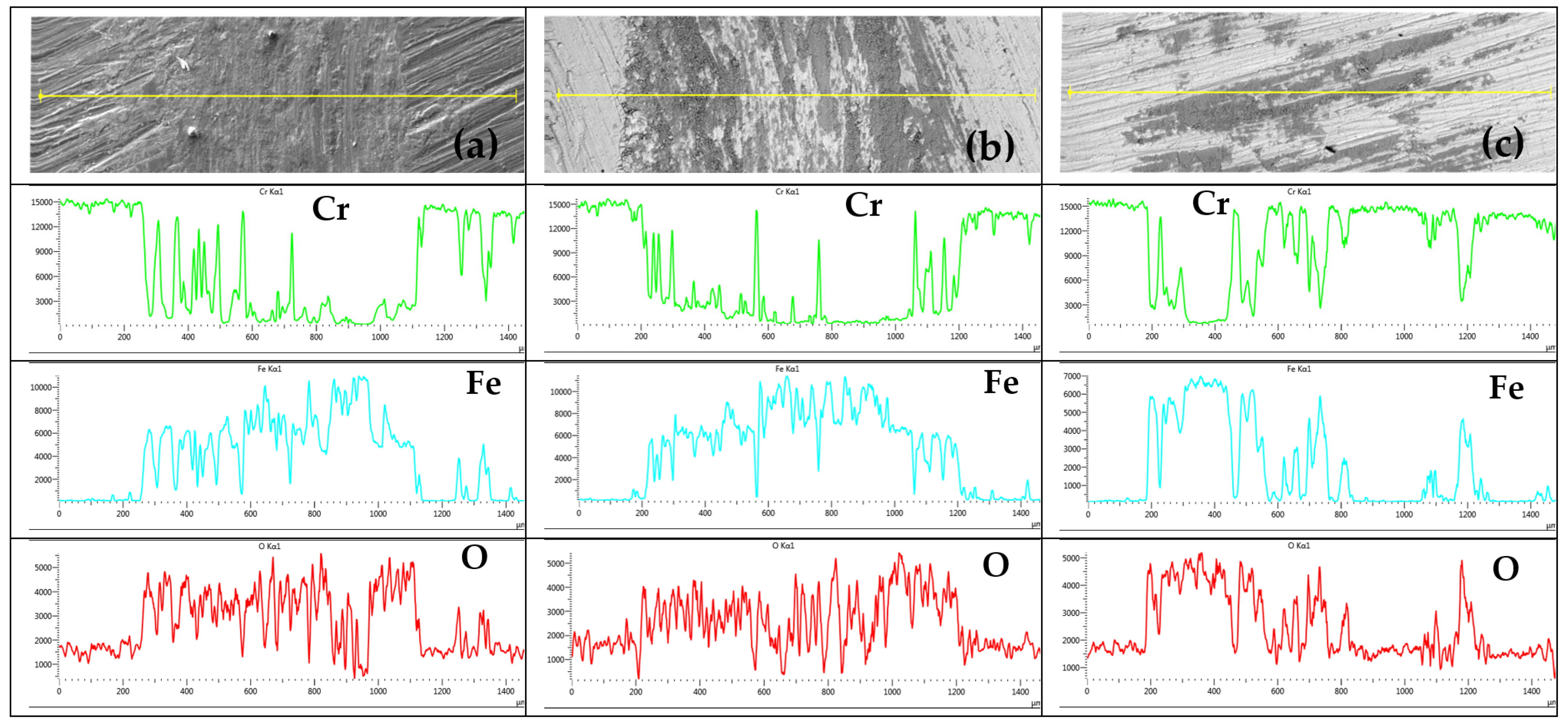

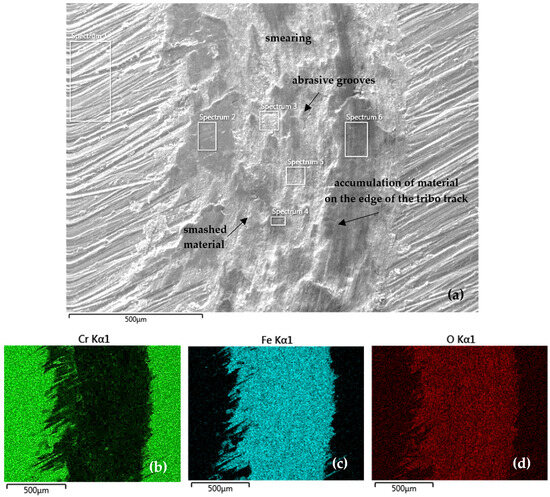

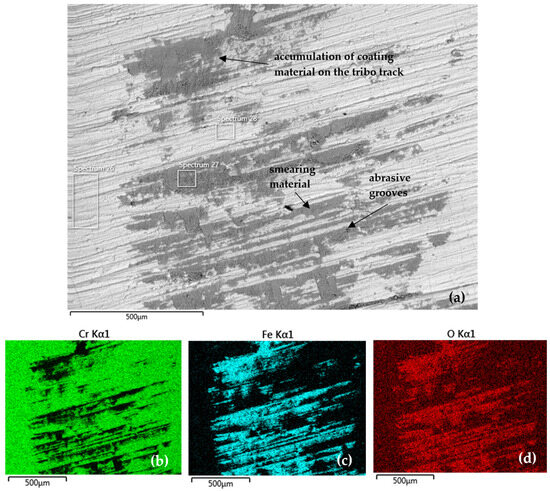

A more detailed analysis of the tribo-track surface with distribution of the analyzed elements was carried out on the SEM microscope using EDS analysis. Figure 10 documents the tribo-track on the CR15 sample surface from the S1 area (as per Figure 5). In the tribo-track center, the smashed coating and substrate material and abrasive grooves can be seen after the contact between the steel tribo-ball and the coating surface. At the tribo-track edges there is a mix of coating (Cr) and steel substrate (Fe and Si) materials. During the tribo-test, tribo-oxides were formed and thus oxygen is also part of the surface, as confirmed by the EDS map of elemental distribution in Figure 10d.

Figure 10.

(a) SEM analysis of the tribo-track CR15 sample surface from the S1 area (according to Figure 5) and (b–d) map of the analyzed element distribution.

Table 7 shows the quantitative EDS SEM analysis from S1 location on the CR15 sample (according to Figure 5). Along the track edges (Spectra 2 and 6 in Table 7), a higher Cr fraction (mainly in Spectrum 2), namely 11.3 wt %, is found. In the track center (Spectrum 3–5) it was mainly Fe oxides, with Cr contents ranging from 2.2 to 3.4 wt % and also Si from steel, at 0.3 wt %. As confirmed by the EDS map of element distribution, a substantial tribo-track part was represented by Fe oxides, mainly in the areas after the coating was ground through to the steel base.

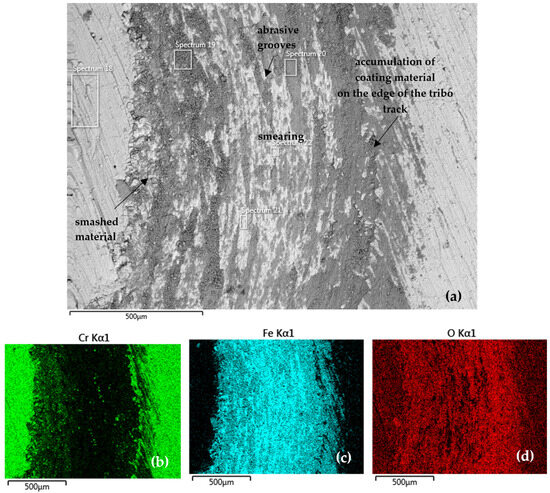

Figure 11 documents the tribo-track on the CR27 sample surface from the S1 area (according to Figure 7). Both coating and substrate material were accumulated along the tribo-track edge (Spectrum 19 in Table 8). The tribo-track center (Spectrum 20–22 in Table 8) was mainly composed of Fe oxides. With such a low oxygen content (Spectrum 21 and 22), the presence of pure Fe can also be assumed. The distribution maps of the analyzed elements showed a slightly higher proportion of Cr in the central region (Figure 11b) compared to the CR15 coating.

Figure 11.

(a) SEM analysis of the tribo-track CR27 sample surface from the S1 area (according to Figure 7) and (b–d) map of the analyzed element distribution.

Table 8 further indicates that a high proportion of Cr, more than 23 wt %, was found along the track edges (Spectrum 19). When the material was redistributed in the tribo-test, the representation of each element in the tribo-track varied, with the Cr content in the central part of the track ranging from 0.7 to 2.9 wt %.

Figure 12 documents the tribo-track on the CR40 sample surface from the S2 area (as shown in Figure 9) and the distribution map of the analyzed elements, also in the S2 area. At this location, the tribo-track on the CR40 sample surface showed the smallest regrinding depth of 1.41 µm Cr coating with the smallest cross-sectional area, namely 191.08 µm2.

Figure 12.

(a) SEM analysis of the tribo-track CR40 sample surface from the S2 area (according to Figure 9) and (b–d) map of the analyzed element distribution.

Quantitative EDS SEM analysis (Table 9) showed the highest Cr content (Spectrum 28) in the central tribo-track area compared to CR15 and CR27. It was 15.7 wt % (Spectrum 27) in coating damage in the tribo-track. Oxygen was part of the tribo-oxides formed as result of the frictional heat applied to the wear coating surface.

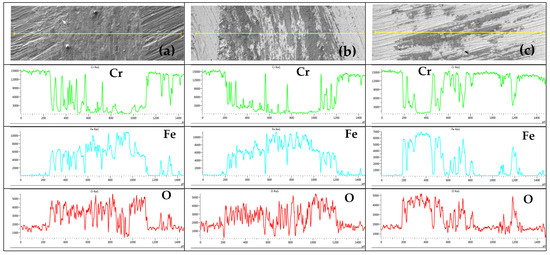

The distribution course of observed elements on the tribo-track surface at S1 location for samples CR15 and CR27 and at S2 location for sample CR40 is shown in Figure 13. The Cr profile showed the most uniform distribution in the CR40 tribo-track. For CR15 and CR27, the Cr distribution was more localized in narrow regions. Fe and oxygen complemented Cr with the greatest symmetry in the CR40 coating. In the case of CR15 and CR27, Fe and O distribution (compared to Cr distribution) indicated a greater proportion of mixing between the coating material and the substrate.

Figure 13.

Distribution course of the analyzed elements Cr, Fe and O on the tribo-track surface at S1 location on the sample: (a) CR15, (b) CR27, (c) surface at S2 location on CR40.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effect of current density on mechanical and tribological properties of Cr coating was investigated. The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- Electrolytic deposition at increasing current density from 15, 27 to 40 A dm−2 led to an increase in the average hardness HIT of the chromium coating with the values; 11.4 ± 1.8 GPa, 11.9 ± 1.2 GPa and 12.9 ± 2.2 GPa. The coating produced at the highest current density exhibited the highest HIT. The formation of a higher number of nucleation sites at higher current density led to a finer microstructure of the electrodeposited coating with higher hardness;

- The tribo-test showed that at the lowest current density of 15 A dm−2, the friction coefficient was 0.7257 ± 0.106, with the wear rate of 12.76 × 10−15 m3. The Cr coating obtained at the highest current density of 40 A dm−2 had the friction coefficient of 0.7161 ± 0.052 with the wear rate an order of magnitude lower, namely 4.80 × 10−15 m3 (Nm)−1;

- The tribo-track topography on the surface of analyzed locations S1–S4 showed that while on the coating deposited at a current density of 15 A dm−2 the regrinding was performed down to the steel substrate in the widest tribo-track at the level of 17.44 µm with the penetration area of 5221.92 µm2, on the Cr coating obtained at a current density of 40 A dm−2 the regrinding was performed in the widest track to a depth of 6.37 µm with the penetration area of 208.25 µm2;

- A more detailed scanning electron microscope analysis showed that when the tribo-ball was applied to the Cr coating surface, the redistribution of the coating material and the substrate took place. This process led to reduction of Cr content mainly in the central region of the tribo-track, accumulation of coating and substrate material around the track edges, especially for coatings deposited at lower current densities: 15 and 27 A dm−2. The coating obtained at the current density of 40 A dm−2 had areas of almost no disturbance in the documented central part of the tribo-track with minimal Cr loss;

- The tribo-track formation for each type of Cr coating was accompanied by tribo-oxides formation on its surface.

For each type of Cr coating, it was ground down to the steel substrate to a lesser or greater extent. However, the wear resistance of the investigated types of electroplated Cr coatings increased analogically, as well as the hardness, with increasing current density.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., G.B. and A.M.; methodology, M.H. and G.B.; software, D.C. and M.V.; validation, M.H., G.B. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M. and P.H.; investigation, M.H., G.B., D.C., M.V. and M.T.; resources, M.H.; data curation, M.H. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., G.B. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, M.H., G.B., A.M., P.H. and M.T.; visualization, G.B., D.C. and M.V.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, M.H. and G.B.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency, grant no. VEGA 1/0267/25.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Giurlani, W.; Zangari, G.; Gambinossi, F.; Passaponti, M.; Salvietti, E.; Di Benedetto, F.; Caporali, S.; Innocenti, M. Electroplating for Decorative Applications: Recent Trends in Research and Development. Coatings 2018, 8, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliofkhazraei, M.; Walsh, F.C.; Zangari, G.; Köçkar, H.; Alper, M.; Rizal, C.; Magagnin, L.; Protsenko, V.; Arunachalam, R.; Rezvanian, A.; et al. Development of electrodeposited multilayer coatings: A review of fabrication, microstructure, properties and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampke, T.; Steger, H.; Zacher, M.; Steinhäuser, S.; Wielage, B. Status quo und Trends der Galvanotechnik. Mater. Werkst. 2008, 39, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezayat, M.; Saghafi Yazdi, M.; Damous Zandi, M.; Azami, A. Tribological and corrosion performance of electrodeposited Ni–Fe/Al2O3 coating. Results Surf. Interfaces 2022, 9, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Wang, J.; Lian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Song, A.; Shi, L. A Study on the Influence of the Electroplating Process on the Corrosion Resistance of Zinc-Based Alloy Coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugua, E.C.; Ujah, C.O.; Asadu, C.O.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Ekwueme, B.N. Electroplating in the modern era, improvements and challenges: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, M. Tribological characterization of electrolytic hard chrome coatings. Acta Mech. Slovaca 2021, 25, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.N.; Lohchab, A.; Singh, D.; Kumar, R.R.; Gaur, P.; Yadav, B.K. Experimental studies on the effect of chromium plating on the mechanical properties of SAE 4140 steel. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 2488–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualnoun Ajeel, D.; Waadulah, H.M.; Sultan, D.A. Effects of H2SO4 and HCl Concentration on the Corrosion Resistance of Protected Low Carbon Steel. Al-Rafidain Eng. 2012, 20, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedrizzi, L.; Rossi, S.; Bellei, F.; Deflorian, F. Wear–corrosion mechanism of hard chromium coatings. Wear 2002, 253, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.R. Corrosion of Electroplated Hard Chromium. In ASM Handbook Corrosion: Materials; Cramer, S.D., Covino, B.S., Jr., Eds.; ASM International: Almere, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 13B, ISBN 978-0-87170-707-9. [Google Scholar]

- Alemayehu, A.; Beyene, E.; Batu, T.; Tirfe, D. Analysis of high temperature oxidation characteristic of chrome-plated, nickel-plated and non-plated mild steels. Adv. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2023, 40, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenson, E. The Future of Hard Chrome. Finishing and Coating. 2023. Available online: https://finishingandcoating.com/index.php/plating/1560-the-future-of-hard-chrome (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- European Commission. Environmental Friendly and Safer Chromium-Free Process for Hard Coatings. LIFE20-ENV-IT-000494. 2023. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE20-ENV-IT-000494/environmental-friendly-and-safer-chromium-free-process-for-hard-coatings (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- European Chemicals Agency. ECHA Proposes Restrictions on Chromium VI Substances to Protect Health. 2023. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/-/echa-proposes-restrictions-on-chromium-vi-substances-to-protect-health (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- DVS Enterprises. Hard Chrome Plating Through Decades: Analyzing Trends & Shifts. 2024. Available online: https://www.dvsenterprises.co.in/hard-chrome-plating-through-decades-analyzing-trends-shifts/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- CPP Prema. Chromium Plating: Functioning and Industrial Use. 2024. Available online: https://cpp-prema.pl/en/chromium-plating-functioning-and-industrial-use/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Mekicha, M.A.; de Rooij, M.B.; Matthews, D.T.A.; Pelletier, C.; Jacobs, L.; Schipper, D.J. The effect of hard chrome plating on iron fines formation. Tribol. Int. 2020, 142, 106003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar-Nouri, Z.; Matthews, D.; Bolt, H.; de Rooij, M. The impact of surface cracks and surface roughness in the performance of hard chromium coatings in cold rolling applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2025, 27, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Cui, X.H.; Wang, S.Q. Investigation on tribo-layers and their function of a titanium alloy during dry sliding. Tribol. Int. 2016, 94, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 10025-2:2004; Hot Rolled Products of Structural Steels—Part 2: Technical Delivery Conditions for Non-Alloy Structural Steels. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Lozrt, J.; Votava, J.; Kumbár, V.; Polcar, A. Analysis of corrosion-mechanical properties of electroplated and hot-dip zinc coatings on mechanically pre-treated steel substrate. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21920-3:2021; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile—Part 3: Specification Operators. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Oliver, W.C.; Pharr, G.M. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 1992, 7, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Gao, J.; Si, C.; Yao, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y. Tribological properties of TiN coating on cotton picker spindle. Coatings 2023, 13, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.A.; Akbarzadeh, S.; Paint, Y.; Vitry, V.; Olivier, M.-G. Comparison of tribological characteristics of AA2024 coated by plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) sealed by different sol–gel layers. Coatings 2023, 13, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20808; Fine Ceramics (Advanced Ceramics, Advanced Technical Ceramics)—Determination of Friction and Wear Characteristics of Monolithic Ceramics by Ball-on-Disc Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Hasanah, I.U.; Priadi, D.; Dhaneswara, D. The effect of current density and hard chrome coating duration on the mechanical and tribological properties of AISI D2 steel. J. Mater. Explor. Find. 2023, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silman, H. Protective and decorative coatings for metals: A wide ranging survey of inorganic and mechanical processes, properties and applications. In Electroplating; Finishing Publications: Chester, UK, 1978; ISBN 978-0-904477-03-0. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, R.; Walmsley, A. Chromium Plating; Finishing Publications: Chester, UK, 1980; ISBN 0904477045. [Google Scholar]

- Lausmann, G.A. Electrolytically Deposited Hardchrome. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1996, 86–87 Pt 2, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, J.; Dias, A.; François, M.; Lebrun, J.L. Residual Stresses and Crystallographic Texture in Hard-Chromium Electroplated Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1997, 96, 148–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.P.; Dang, H.T.; Nguyen, N.P.L.; Le, C.C.; Dang, T.N. Study on Microcracks’ Density and Residual Stress of the Hard Chrome Electroplating Layer in AISI 1045 Steel. Can. Metall. Q. 2024, 64, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broitman, E.; Jahagirdar, A.; Rahimi, E.; Meeuwenoord, R.; Mol, J.M.C. Microstructural, Nanomechanical, and Tribological Properties of Thin Dense Chromium Coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploypech, S.; Metzner, M.; dos Santos, C.B.; Jearanaisilawong, P.; Boonyongmaneerat, Y. Effects of Crack Density on Wettability and Mechanical Properties of Hard Chrome Coatings. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2019, 72, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viáfara, C.C.; Sinatora, A. Influence of hardness of the harder body on wear regime transition in a sliding pair of steels. Wear 2009, 267, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamburg, Y.D.; Zangari, G. Theory and Practice of Metal Electrodeposition; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9669-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kanani, N. Electroplating: Basic Principles, Processes and Practice, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 117–131. ISBN 1856174514. [Google Scholar]

- Allahyarzadeh, M.H.; Ashrafi, A.; Golgoon, A.; Roozbehani, B. Effect of pulse plating parameters on the structure and properties of electrodeposited Ni–Mo films. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 175, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Nagumo, M.; Umemoto, M. The Hall-Petch relationship in nanocrystalline materials. Mater. Trans. JIM 1997, 38, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, J.; Jiang, Q. Hall-Petch relationship in nanometer size range. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 361, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.M.; Hu, X.H.; Zhang, W.J. Experimental comparison of five friction models on the same test-bed of the micro stick-slip motion system. Mech. Sci. 2015, 6, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raab, A.E.; Berger, E.; Freudenthaler, J.; Leomann, F.; Walch, C. ZnAlMg hot-dip galvanised steel sheets–tribology and tool wear. BHM Berg Hüttenmänn. Monatsh. 2012, 157, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).