Thermal Stress Effects on Band Structures in Elastic Metamaterial Lattices for Low-Frequency Vibration Control in Space Antennas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geometries and Materials

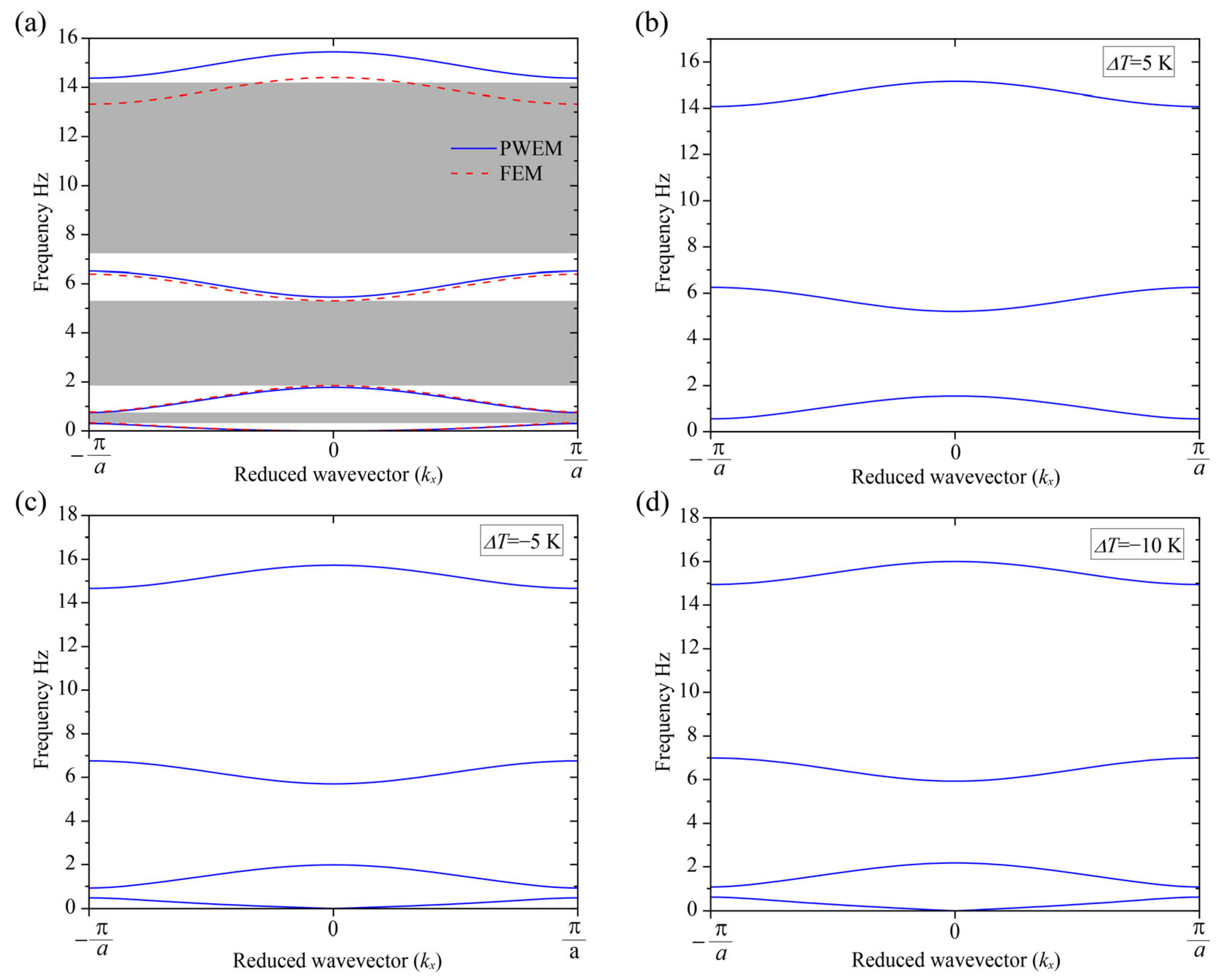

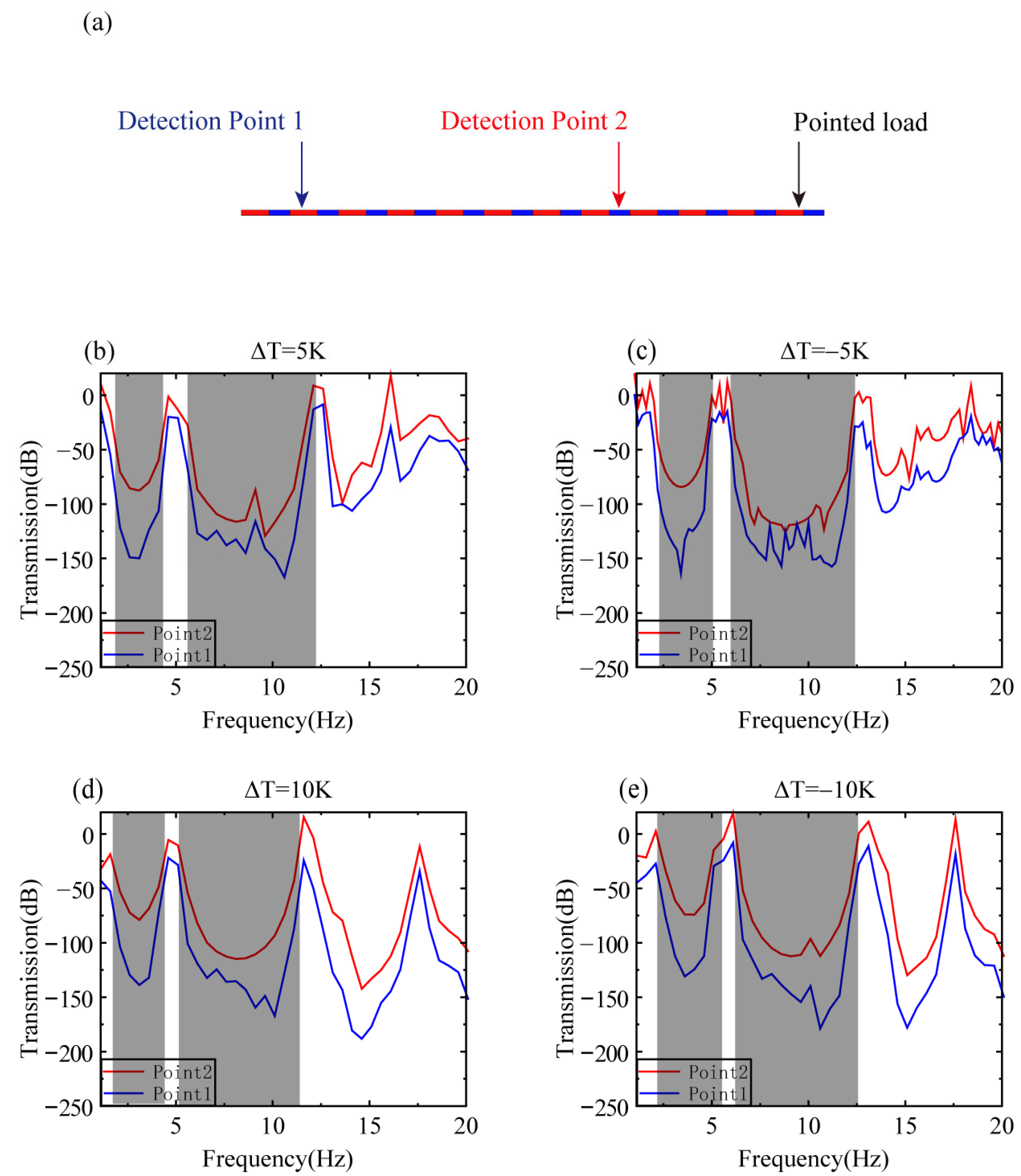

3. One-Dimensional EM Beam

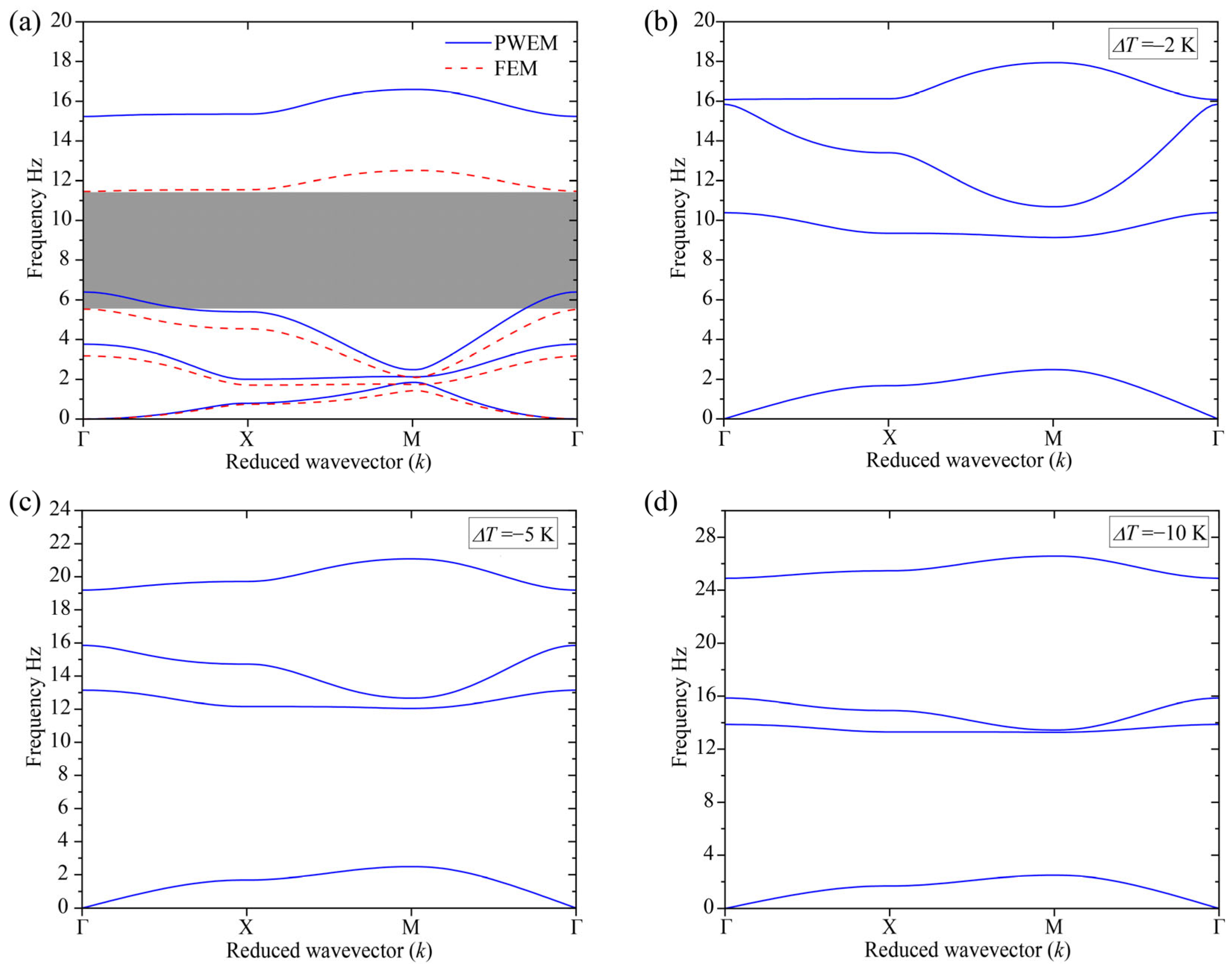

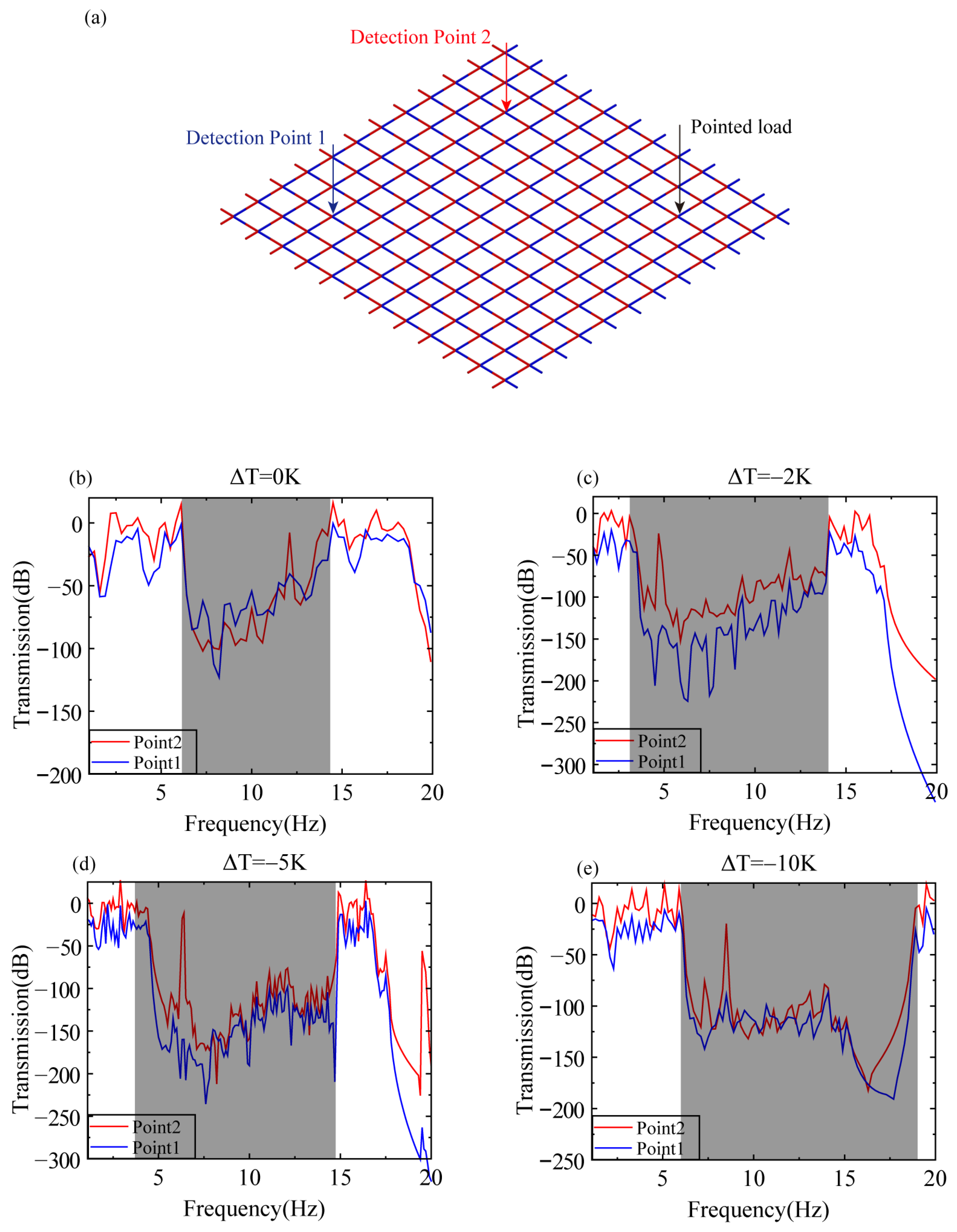

4. Two-Dimensional EM Lattice

4.1. Two-Dimensional Square EM Lattice

4.2. Two-Dimensional Rectangular EM Lattice

5. Method Verification

5.1. One-Dimensional EM Beam

5.2. Two-Dimensional EM Lattice

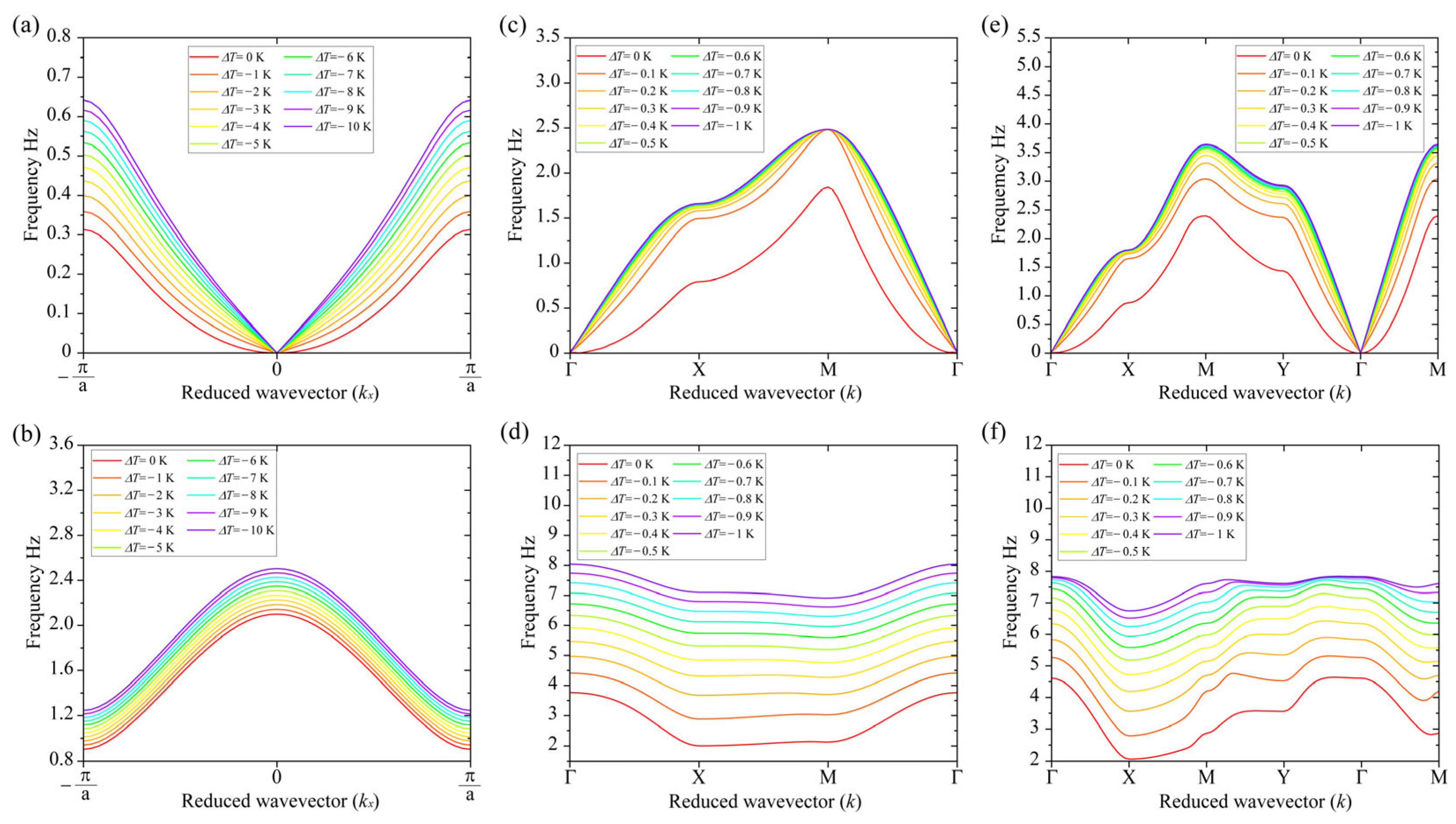

6. Bands and Band Gap Variations Versus Temperature Differences

6.1. Band Variations of EM Lattices

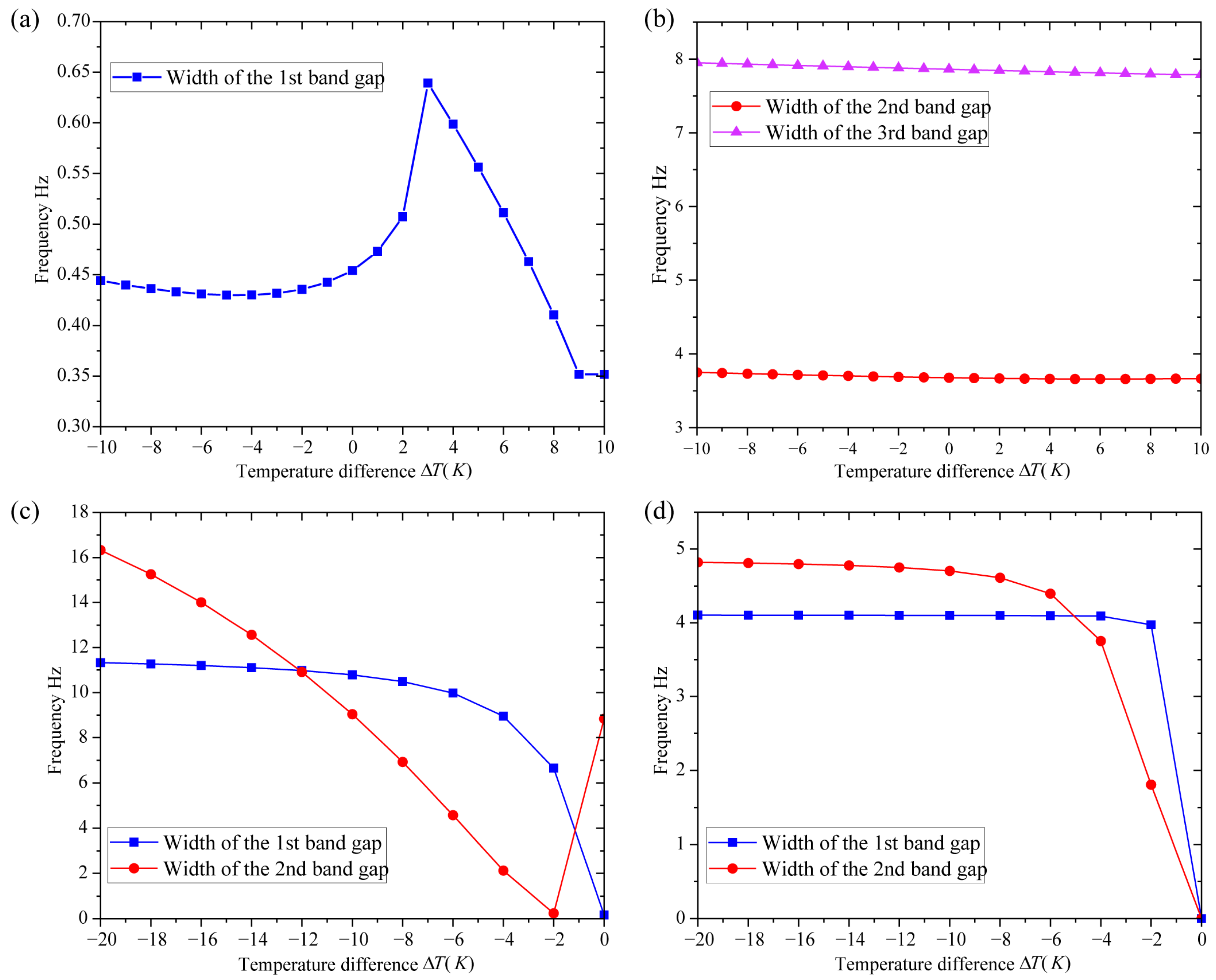

6.2. Bandwidth Variations of EM Lattices

7. Sensitivity Analysis of Band Structure to Temperature Difference

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| EM | Elastic Metamaterial |

References

- Ma, X.; Li, T.; Ma, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, C.; Zheng, S.; Cui, Q.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Guo, H.; et al. Recent advances in space-deployable structures in China. Engineering 2022, 17, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Y. Advances in spacecraft micro-vibration suppression methods. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2023, 138, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, T. Design Method of High Precision Perimeter Truss Antenna on Board. Chin. Space Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Research on Active Control Strategy for Large-Scale Cable Net Structures Based on Wave Theory; Beijing Institute of Technology: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. Vibration Analysis and Suppression of Space Deployable Flexible Antennas; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tong, A.; Wu, N.; Liu, Y. Thermally-induced vibration of a solar sail in earth orbit. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2019, 40, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z. Analysis of Thermal Deformation of Composite Material Truss Structures; Harbin Institute of Technology: Harbin, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, Y. Review of Research on Thermally Induced Dynamic Responses of Large-Scale Space Structures. Space Electron. Technol. 2020, 17, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Cao, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J. Dynamic modeling and vibration control of a large flexible space truss. Meccanica 2022, 57, 1017–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Schmidt, R.; Qin, X. Active vibration control of piezoelectric bonded smart structures using PID algorithm. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2015, 28, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, H.Z.; Cong, D.C.; Han, J.W. Active structural control based on lqg/ltr method. Eng. Mech. 2006, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Guo, Y.; Li, C. Independent Modal Space Optimal Control Method for Vibration of Flexible Space Structures. Flight Control. Detect. 2019, 2, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.K.; Liang, L.; Zheng, G.T.; Huang, W.H. Dynamic Design of Octostrut Platform for Launch Stage Whole-Spacecraft Vibration Isolation. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2005, 42, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, J.; Ge, X. Research on Vibration Suppression of Flexible Spacecraft Based on Fuzzy PD Control. Comput. Simul. 2022, 39, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, M.; Cao, X. Non-singular terminal second-order sliding mode control of spacecraft on disturbance observer. Control Theory Appl. 2023, 40, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Shan, X.; Hou, W.; Wang, C.; Sun, K.; Xie, T. A novel piezoelectric-based active-passive vibration isolator for low-frequency vibration system and experimental analysis of vibration isolation performance. Energy 2023, 278, 127870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Li, H.; Tang, Y. Novel vibration control method of acoustic black hole plates using active–passive piezoelectric networks. Thin Walled Struct. 2023, 186, 110705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ge, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Fang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Dong, L.; Xu, M. Vibration control scheme and its experimental verification for large spacecraft antenna. Spacecr. Eng. 2018, 27, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabolghasemi, A.; Akbarzadeh, A.H.; Rodrigue, D.; Therriault, D. Thermal conductivity of architected cellular metamaterials. Acta Mater. 2019, 174, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y.; Jiang, G.S.; Wang, Z. Progress in researches of phononic crystal and the application perspectives. Shengxue Jishu 2006, 25, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.H.; Han, X.Y.; Wang, G. Review of phononic crystals. J. Funct. Mater. 2003, 34, 364–367. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Lacarbonara, W.; Cheng, L. Advances in nonlinear acoustic/elastic metamaterials and metastructures. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 113, 23787–23814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Yang, Z.; Chan, C.T.; Sheng, P. Locally Resonant Sonic Materials. Science 2000, 289, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Peng, W.; Song, J. Thermal tuning of band structures in a one-dimensional phononic crystal. J. Appl. Mech. 2014, 81, 041008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Chu, D.; Yang, F.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhuang, Z. Characteristics of band gap and low-frequency wave propagation of mechanically tunable phononic crystals with scatterers in periodic porous elastomeric matrices. J. Appl. Mech. 2021, 88, 051001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Wu, F.G.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.W. Phononic crystal multi-channel low-frequency filter based on locally resonant unit. Acta Phys. Sin. 2014, 63, 24301-024301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Experimental investigation of vibration damper composed of acoustic metamaterials. Appl. Acoust. 2017, 119, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ahn, C.H.; Lee, J.W. Vibro-acoustic metamaterial for longitudinal vibration suppression in a low frequency range. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 144, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, J.; Zhang, K. Multi-Stable Mechanical Mematerials for Band Gap Tuning. J. Dyn. Control. 2023, 21, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.G.; Wu, T.T. Temperature effect on the bandgaps of surface and bulk acoustic waves in two-dimensional phononic crystals, Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2005, 52, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.J.; Wu, D.J. Temperature effects on the band gaps of Lamb waves in a one-dimensional phononic-crystal plate (L). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, K.L.; Leung, C.W.; Lau, S.T.; Choy, S.H.; Chan, H.L.W. Thermal tuning of phononic bandstructure in ferroelectric ceramic/epoxy phononic crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 193501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Z. Thermal tuning of Lamb wave band structure in a two-dimensional phononic crystal plate. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Zhang, X.; Wu, F.; Yao, Y.; Cheng, C.; Huang, P. Temperature effects on the defect states in two-dimensional phononic crystals. Phys. Lett. A 2014, 378, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Li, F.M.; Kishimoto, K.; Wang, Y.S.; Huang, W.H. Wave localization in randomly disordered layered three-component phononic crystals with thermal effects. Arch. Appl. Mech. 2010, 80, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahryari, B.; Mirabolghasemi, A.; Eskandari, S.; Chen, X.; Deü, J.; Ohayon, R.; Mohany, A.; Kalamkarov, A.; Akbarzadeh, A. Conformally perforated shellular metamaterials with tunable thermomechanical and acoustic properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2506062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, K.; Yang, L.; Zhao, R. Generalized thermoelastic band structures of Rayleigh wave in one-dimensional phononic crystals. Meccanica 2018, 53, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, K.; Yang, L.; Zhao, R.; Shi, X.; Tian, K. Effect of thermal stresses on frequency band structures of elastic metamaterial plates. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 413, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y. Thermal stress effects on the flexural wave bandgap of a two-dimensional locally resonant acoustic metamaterial. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 195101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.M. The Lamb wave bandgap variation of a locally resonant phononic crystal subjected to thermal deformation. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 055109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.M. The band gap variation of a two dimensional binary locally resonant structure in thermal environment. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 015002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Cai, T.; Li, Y. Flexural wave manipulation and energy harvesting characteristics of a defect phononic crystal beam with thermal effects. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 035103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelif, A. Phononic Crystals; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 10, pp. 971–978. [Google Scholar]

- Xue-Feng, Z.; Sheng-Chun, L.; Tao, X.; Tie-Hai, W.; Jian-Chun, C. Investigation of a silicon-based one-dimensional phononic crystal plate via the super-cell plane wave expansion method. Chin. Phys. B 2010, 19, 044301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigalas, M.M.; Economou, E.N. Elastic waves in plates with periodically placed inclusions. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 75, 2845–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Tamura, S. Surface acoustic waves in two-dimensional periodic elastic structures. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.C.; Wu, T.T. Efficient formulation for band-structure calculations of two-dimensional phononic-crystal plates. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2006, 74, 144303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miranda, E.J.P., Jr.; dos Santos, J.M.C. Flexural wave band gaps in phononic crystal Euler-Bernoulli beams using wave finite element and plane wave expansion methods. Mater. Res. 2018, 20 (Suppl. S2), 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.A.N.; Ni, Z.; Han, L.; Zhang, Z.M.; Chen, H.Y. Study of improved plane wave expansion method on phononic crystal. Optoelectron. Adv. Mater. Rapid Commun. 2011, 5, 870–873. [Google Scholar]

- Komkov, V.; Choi, K.K.; Haug, E.J. Design Sensitivity Analysis of Structural Systems; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shirzadkhani, R.; Eskandari, S.; Akbarzadeh, A. Non-fourier thermal wave in 2D cellular metamaterials: From transient heat propagation to harmonic band gaps. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 205, 123917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.D.; Guo, X.; Liu, T.; Su, X. Synchronization of broadband energy harvesting and vibration mitigation via 1:2 internal resonance. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 301, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aluminum | Silicone Rubber | |

|---|---|---|

| Mass density [kg/m3] | 2799 | 1300 |

| Young’s modulus [N/m2] | 7.21 × 1010 | 1.18 × 105 |

| Poisson ratio | 0.3 | 0.468 |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion [K−1] | 21.7 × 10−6 | 250 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Li, M.; Han, Z.; Fadi, C.; Wang, K.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Wu, Y. Thermal Stress Effects on Band Structures in Elastic Metamaterial Lattices for Low-Frequency Vibration Control in Space Antennas. Crystals 2025, 15, 937. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110937

Wang S, Li M, Han Z, Fadi C, Wang K, Shen Y, Wang X, Li X, Wu Y. Thermal Stress Effects on Band Structures in Elastic Metamaterial Lattices for Low-Frequency Vibration Control in Space Antennas. Crystals. 2025; 15(11):937. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110937

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shenfeng, Mengxuan Li, Zhe Han, Chafik Fadi, Kailun Wang, Yue Shen, Xiong Wang, Xiang Li, and Ying Wu. 2025. "Thermal Stress Effects on Band Structures in Elastic Metamaterial Lattices for Low-Frequency Vibration Control in Space Antennas" Crystals 15, no. 11: 937. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110937

APA StyleWang, S., Li, M., Han, Z., Fadi, C., Wang, K., Shen, Y., Wang, X., Li, X., & Wu, Y. (2025). Thermal Stress Effects on Band Structures in Elastic Metamaterial Lattices for Low-Frequency Vibration Control in Space Antennas. Crystals, 15(11), 937. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15110937