Abstract

This study investigated the hierarchical structuring of *BEA zeolite using 0.2 M sodium hydroxide followed by 0.5 M hydrochloric acid (T-NaOH-HCl). Tungsten trioxide (WO3) was then impregnated at different loadings (5, 10, 15, and 20 wt.%) onto the hierarchized materials (BEA-T). The modified zeolites were subsequently used as catalysts for the dehydration of ethanol (230 and 250 °C) and 1-propanol (230 °C). The hierarchization treatment increased the Si/Al ratio (from 13 to 39), decreased relative crystallinity by 15%, and reduced the average crystal-domain size (from 18 to 10 nm). After the NaOH–HCl treatment (BEA-T), the mesopore area increased by 7%, the mesopore volume by 19%, and the total pore volume by 12%. Conversely, the BET specific surface area and micropore volume decreased, indicating effective hierarchization of the *BEA zeolite. XRD, FT-IR and Raman confirmed the presence of monoclinic WO3 on the BEA-T surface. MAS NMR analyses of 27Al and 29Si indicated that the T-NaOH-HCl treatment slightly increased the population of tetrahedral Al environments. The high conversion and selectivity from the dehydration of ethanol and 1-propanol can be attributed to a moderate reduction in the acidity of *BEA zeolite and tunned mesoporosity. Based on TON, catalysts with 10% and 20% WO3 stood out in dehydration tests.

1. Introduction

The year 2023 was marked by record levels of production and consumption following the COVID-19 pandemic. Crude oil consumption, for example, surpassed 100 million barrels per day for the first time in history, and the use of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel also returned to 2019 levels and has continued to grow [1]. Due to the current high demand, refineries have sought to maximize chemical yields while minimizing energy consumption. Zeolites such as USY and ZSM-5 are widely used in catalytic cracking processes, which makes studies focused on enhancing the performance and selectivity of these materials of great industrial interest [2]. The *BEA zeolite, first synthesized in 1967 by the Mobil Oil Corporation, possesses wide pores, a high silica content, and acts as an adsorbent with high catalytic activity [3]. It has a three-dimensional framework composed of intersecting channels and large micropores (0.55 × 0.55 nm along the [001] plane and 0.66 × 0.67 nm along the [100] plane), formed by 12-membered rings and typically exhibiting a Si/Al ratio between 12 and 30 [4]. This zeolite may display intergrowth of several distinct but closely related polymorphs, including the chiral polymorph A and the achiral polymorphs B and C [5].

One of the current challenges in zeolite research involves the development of materials with hierarchical pore structures, which can combine the intrinsic catalytic properties of microporous zeolites with improved molecular access and transport through secondary meso- and macropores [6,7,8]. Post-synthesis routes used to prepare hierarchical zeolites often involve demetallation or delamination through acid, alkaline, or fluoride leaching, offering high versatility, low cost, good pore connectivity, and potential scalability [9]. Chemical leaching can induce dealumination or desilication by selectively removing framework aluminum or silicon atoms from the zeolite structure, thereby generating secondary intracrystalline mesopores and amorphous regions within the crystalline framework [10]. The use of base and acid leaching as a post-synthetic modification can preserve crystallinity, allowing better access to micropores. Groen et al. [11] showed that successive steam and alkaline treatment on ZSM-5 resulted in a limited mesoporosity development (80 m2 g−1) and a limited Si extraction. An alkaline treatment (0.2 M NaOH aqueous solution) of HBEA [6] resulted on extensive silicon extraction at mild treatment conditions, reducing microporous on half and acid properties at 338 K, while the alkaline treatment at 298 K hardly induced any new mesoporosity. On the other hand, when *BEA zeolite was submitted to an acid leaching procedure (HCl and HNO3) [12], all kinds of extra-framework impurities from aluminum clusters to silica-alumina debris were removed or passivated [10].

Additionally, the introduction of new catalytically active species, such as metal oxides, into zeolites has been used to reduce coke accumulation on active sites [10]. Among metal oxides, tungsten trioxide (WO3) can act as a photocatalyst [13], facilitating reactions such as the degradation of organic pollutants in water and the oxidation of hydrocarbons. It can also be employed as a catalyst support material, where its morphology, structure, and acidity play crucial roles [14]. WO3-impregnated materials exhibit strong performance in surface reactions involving acid sites (Brønsted and Lewis) and demonstrate significant adsorption properties due to the presence of oxygen vacancies [15]. Said et al. studied WO3 supported on HZSM-5 and HY, showing that these composites are effective catalysts for the non-oxidative dehydrogenation of ethanol to acetaldehyde [16].

Among catalytic applications, biomass conversion plays a crucial role, as it is the only renewable carbon source for producing valuable chemicals such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) from sugars like fructose or glucose through dehydration reactions [17,18]. The dehydration of C2+ alcohols to olefins is essential for manufacturing basic chemicals, synthetic resins, fibers, and rubbers, and serves as a precursor process for ethylene production, which underpins industries such as pharmaceuticals, dyes, agrochemicals, and plastics [19,20,21]. This route also represents an important pathway for utilizing non-petroleum feedstocks, including biomass-derived alcohols and coal-based chemical by-products.

Several articles in the literature separately report post-synthesis treatments using either bases (usually NaOH) or acids (HCl, HNO3, etc.) [6,11,12]. In this contribution, we present a combined approach (NaOH followed by HCl) to tailor the porous and acidic properties of BEA zeolite and its WO3-impregnated form. The objective of the present study was to prepare *BEA zeolite with a hierarchical pore structure using a post-synthesis treatment with sodium hydroxide followed by hydrochloric acid (T-NaOH-HCl). The hierarchical BEA zeolite was then impregnated with tungsten trioxide (WO3) to introduce catalytically active acid sites for its application in the dehydration of ethanol (at 230 °C and 250 °C) and 1-propanol (at 230 °C). To evaluate the structure of the modified materials, elemental analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), pore and specific surface area analysis, solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance with magic-angle spinning (27Al and 29Si MAS NMR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and pyridine adsorption followed by FT-IR spectroscopy were employed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Elemental and XRD Analyses

Elemental analysis of Si, Al, and W revealed the composition of the catalysts and is shown in Table 1. It can be observed that after the treatment of the BEA zeolite, the Si/Al ratio increased, which confirms the dealumination of the parent zeolite. Additionally, the impregnation of WO3 was efficient, and the theoretical and actual loadings were very close. Thus, the samples will be referred to from here on by their theoretical values for greater clarity.

Table 1.

Total Si/Al ratio, WO3 quantity and relative crystallinity (C) of the catalysts.

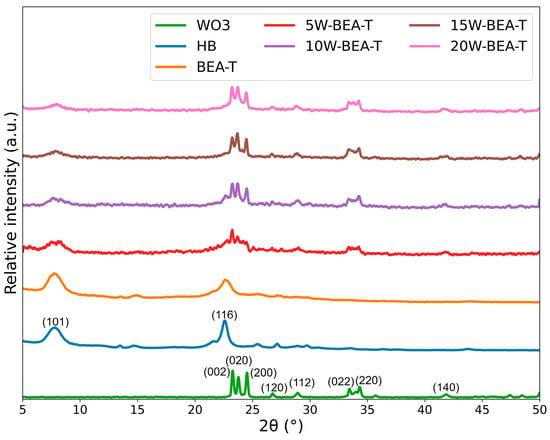

The XRD pattern of the BEA zeolite, characterized by both broad and narrow peaks, reflects structural disorder caused by stacking faults resulting from the intergrowth of two polymorphs (44% chiral and 56% achiral). Characteristic diffraction peaks were observed at 7.80° (101) and 22.50° (116) (Figure 1) [17]. The random stacking fault of polymorphs leads to a structure that is not well defined in the XRD pattern. The loss of crystallinity from HB to BEA-T (15%) is relatively small (Table 1, column 4) and comparable to the loss of microporous area (15%) and volume (17%) (Table 2). Relative crystallinity, calculated based on the total area of all characteristic peaks, showed a 15% reduction after treatment with T-NaOH-HCl, and WO3 impregnation led to an additional 20–30% decrease compared to HB. Incorporating more than 10 wt.% of another metal can help prevent significant collapse of the zeolitic structure by occupying silanol nests [22,23].

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of WO3, HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

Table 2.

Textural parameters for the catalysts.

The calcined material (550 °C) after WO3 impregnation exhibited a greenish-yellow color, corresponding to the monoclinic phase of WO3 (JCPDS 43-1035) as the only crystalline phase of this oxide. This phase revealed distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 23.2°, 23.5°, 24.0°, 26,7°, 28.7°, 33.6°, 34,3°, and 41,9° in the XRD pattern of WO3-loaded catalysts, suggesting that a WO3 crystalline species was successfully supported. These peaks were attributed to the (002), (020), (200), (120), (112), (022), (220) and (140) lattice planes, respectively [16], indicating limited dispersion of WO3 species, and they became more intense with increasing WO3 loading on the BEA zeolite [13,16]. A reduction in the average crystalline domain size (D) of HB from 18 nm to 10 nm was observed after hierarchization (BEA-T). After WO3 impregnation, D of HB increased to approximately 15 nm. Additionally, the WO3 crystallites domain deposited on BEA ranged from 15 nm (5W-BEA-T) to 50 nm (20W-BEA-T). In contrast to pure WO3 crystallites (with domains of ~70 nm), the supported materials consisted of smaller nanocrystals deposited on the surface of the agglomerated hierarchical BEA zeolite [16], as observed by SEM (vide Section 2.6).

2.2. FT-IR and Raman Spectroscopies

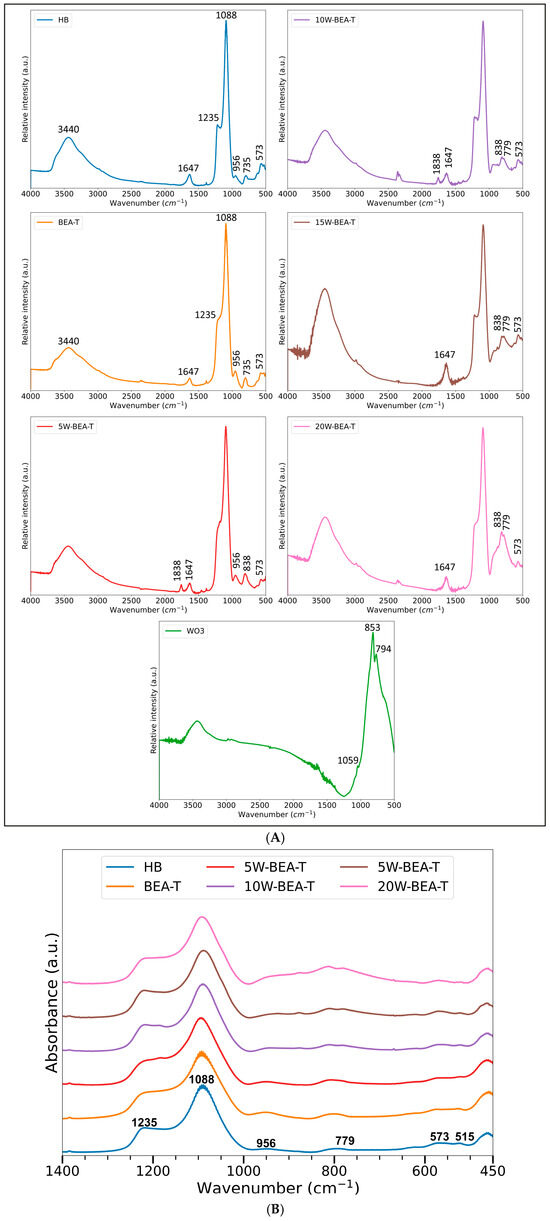

Infrared (FT-IR) results (Figure 2A,B) showed bands corresponding to *BEA zeolite samples at the following wavenumbers: 573 cm−1 and a small band at 515 cm−1 (vibrational modes of five- and six-membered rings), 779 cm−1 (external symmetric stretching vibration of oxygen in T-O-T bonds), 956 cm−1 (vibration of Si-O bonds), 1088 cm−1 (internal Si-O-T stretching vibration of the zeolite framework where T is a tetrahedral atom like Al or Si), 1235 cm−1 (external vibration of the framework structure or vibrations of guest molecules adsorbed within the zeolite pores), 1647 cm−1 (angular bending vibration of adsorbed or occluded water molecules (H-O-H) and 3440 cm−1 (stretching vibrations of hydroxyl groups of physically adsorbed water molecules) [17,24]. It should be noted that the small bands at approximately 3000, 1838, and 1400 cm−1 are likely due to organic impurities introduced during pellet preparation.

Figure 2.

(A) FT-IR spectra (4000 to 500 cm−1) of: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, 20W-BEA-T, and WO3. (B) FT-IR spectra (1400 to 450 cm−1) of: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

The spectrum of pure WO3 shows typical absorptions at 853 and 794 cm−1 corresponding to stretching vibrations of the W-O-W (tungsten-oxygen-tungsten) bridging oxygen bonds [16]. WO3 impregnation on BEA-T clearly reveals the presence of this species on the BEA-T surface through increased vibrational intensities at 838 and 779 cm−1. The shift of these bands to lower wavenumbers indicates a significant interaction between WO3 and the BEA-T surface, as evidenced by the 15 cm−1 shift to lower wavenumbers, which weakens the W-O-W bond. The band at 1235 cm−1 is sensitive to the overall structure and the presence of extra-framework species or cations. This band is generally assigned to the external asymmetric stretching vibration of the T-O-T (Si-O-Si or Si-O-Al) and when WO3 is introduced via impregnation, the tungsten species (e.g., tungstate ions, W=O groups) interact chemically and physically with the zeolite surface and internal channels. This interaction can involve the formation of new Si-O-W or Al-O-W bonds or the coordination of W species near existing Si-O-Al sites which alter the local electron density and bond angles of the adjacent framework linkages.

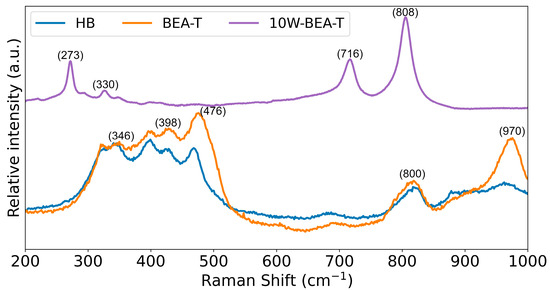

The Raman spectrum of HB (Figure 3) shows the vibrational modes of oxygen in the TO4 tetrahedra that make up the zeolitic structure. The band at 346 cm−1 corresponds to interlayer vibrations of five-membered rings; the band at 398 cm−1 corresponds to interlayer vibrations of six-membered rings; and the bands at 476 and 500 cm−1 are attributed to interlayer vibrations of four-membered rings, indicating the distinct spectral features of the HB structure [25]. The band at approximately 800 cm−1 is related to the symmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si linkages in the zeolitic framework, while the band at 970 cm−1 is associated with Si–O stretching vibrations that are sensitive to the Si/Al ratio. The Raman spectrum of BEA-T is similar to that of the HB sample, except for an increase in the relative intensity of the 970 cm−1 band, which was also observed in the FT-IR spectrum and is consistent with the increase in Si/Al ratio obtained by elemental analysis, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of: HB (blue), BEA-T (orange), and 10W-BEA-T (violet).

On the other hand, the Raman spectrum of 10W-BEA-T shows four main bands: 330 and 273 cm−1, assigned to bending vibrations, and 808 and 716 cm−1, attributed to stretching modes of W–O–W bonds present in WO3 nanocrystals. The band at 716 cm−1 is also associated with the formation of crystalline WO3 [16,26]. The zeolite bands in the Raman spectrum almost disappeared when WO3 was impregnated on the BEA-T, primarily due to strong electronic and structural interactions between the WO3 species and the zeolite framework, and potentially self-absorption effects [16,26]. Also, scattering from crystalline metal oxides is very intense and probably contributes to quenching (or lowering) any signals from different supports (amorphous or crystalline). The impregnating solution (ammonium tungstate) interacts with the hydroxyl groups and Brønsted acid sites within the BEA-T and on its external surface. The tungsten species anchor onto these sites, often replacing protons in the Si-OH+-Al sites. The formation of W-O-Si or W-O-Al bonds and the subsequent calcination process (which decomposes the precursor to WO3) lead to a significant change in the local crystal structure of the zeolite framework. Zeolite Raman bands are primarily associated with the bending and stretching vibrations of the T-O-T linkages (T = Si, Al) within the characteristic 5-membered ring that form the BEA zeolite framework. These structural alterations, caused by the incorporation of the large WO3 species, interfere with these specific vibrational modes, leading to a significant decrease in intensity or the complete disappearance of the characteristic peaks. Increasing WO3 loading, followed by calcination process might perturb the long-range crystalline order of the BEA-T framework, causing a certain degree of amorphization. Amorphous materials produce broad Raman signals compared to the sharp, intense peaks of a highly crystalline material. The new, potentially intense, Raman bands of the formed WO3 species (at ~800 cm−1 and 700 cm−1) can mask the underlying, often weaker, zeolite framework bands. Changes in the surface morphology and particle size of the material after impregnation and calcination can also affect the scattering properties and, consequently, the observed Raman intensity.

2.3. Main Textural Properties Determined by N2 Adsorption/Desorption Isotherms

Textural properties were analyzed using N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms obtained at −196 °C and t-plot curves (Figures S1 and S2). All samples exhibited a combination of predominantly type I(a) (microporous solid) and type IV(a) isotherms, with a hysteresis loop appearing at higher relative pressures (P/P0 > 0.7; Figure S1), indicating the presence of a secondary mesoporous structure (Table 2). Assuming that the total area obtained by the BET method includes the microporous, mesoporous, and external surface areas, and that the created mesoporosity can be both intra- and intercrystalline, the mesoporous area was calculated as the external surface area, as previously reported for BEA catalysts [6]. After the NaOH–HCl treatment (BEA-T), the mesopore area increased by 7%, the mesopore volume by 19%, and the total pore volume by 12%. Conversely, the specific surface area (SBET) and micropore volume (VMicro) decreased by 15 and 17%, respectively, indicating effective hierarchization of the *BEA zeolite. This trend was also observed for Nb-BEA catalysts [17]. On the other hand, WO3 nanoparticles exhibited a type II isotherm with an H3 hysteresis loop, according to the IUPAC classification, which are characteristic of nonporous solids composed of non-rigid aggregates of plate-like particles and possessing low surface area [27,28]. The presence of hysteresis also indicates the existence of mesopores or macropores.

The isotherms of the WO3 catalysts show similar characteristics of *BEA zeolite, i.e., a combination of types I(a) and IV(a). The incorporation of WO3 clusters into zeolite led generally to a reduction in all measured textural parameters of the HB and BEA-T support, suggesting that tungsten species adhered to the zeolite surface and partially filled the pores. This suggests that impregnating the HB zeolite after hierarchization results in the formation of extra-framework WO3 species, with surface layer thickness dependent on tungsten loading, as previously reported [16]. The decreasing microporous area and volume of the WO3 catalysts is also indicative that an overlayer of WO3 is formed on the BEA-T surface and partially blocks microporous accessibility.

The scenario that can be envisioned for the supported WO3 suggests that WO3 species, including the monoclinic nanocrystalline phase, partially cover the surface of the BEA-T zeolite. This partial coverage is evidenced by several analytical methods, such as XRD, FT-IR, Raman, and N2 adsorption/desorption. If there were a complete, homogeneous coverage of the zeolite surface, all textural properties would be similar to those of pure WO3, which was not observed. From the point of view of WO3, its dispersion within the zeolite includes the formation of agglomerates; however, these agglomerates still lead to an increase in accessibility to the newly created acidic sites, as discussed in the acidity section (see Section 2.5).

Furthermore, diffusional limitations were mitigated through the combination of intrinsic microporosity and auxiliary mesoporosity generated by inter- and intra-crystalline structuring, likely driven by silicon and aluminum dissolution mechanisms. This is an important issue, since the catalytic behavior of WO3–BEA-T composites could achieve optimal performance, which depends on both the mesoporosity and acidity, as will be discussed later.

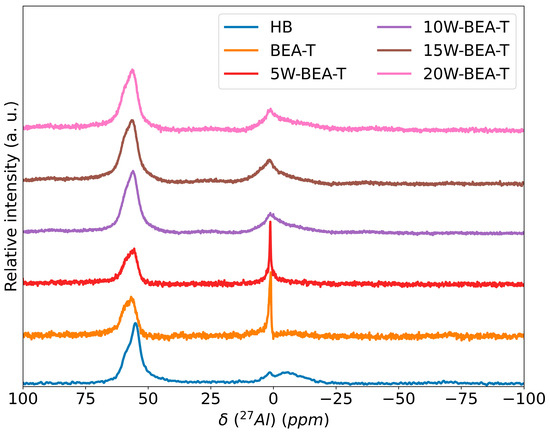

2.4. Solid State (MAS) 27Al and 29Si NMR Spectroscopy

The MAS NMR spectra of 27Al (Figure 4) exhibit signals corresponding to tetrahedral aluminum (Al-Td, 40–80 ppm), extra-framework pentacoordinate aluminum species, and octahedral aluminum environments (Al-Oh, −22 to 22 ppm), corroborating the XRD and FT-IR results, which indicate the preservation of the *BEA zeolite structure. This detailed spectral analysis confirms the integrity of the BEA-T zeolite while also revealing the specific nature of any extra-framework species formed during treatment. The intense signal at 1.4 ppm observed for BEA-T and 5W-BEA-T is attributed to octahedrally coordinated Al species with fewer associated water molecules, whereas the signal broadening in this region for the 10W-BEA-T to 20W-BEA-T samples suggests a higher degree of hydration in the catalyst structure [29,30]. The 27Al NMR data corroborate the presence of the 970 cm−1 Raman band on BEA-T, indicating the structural defects (silanol groups) that form when aluminum is removed from the framework. This removed aluminum often relocates to extra-framework positions, where in the presence of water, it adopts a six-coordinate (octahedral) configuration, giving rise to the signal at approximately 0 ppm in the spectrum. Therefore, both signals arise from the same process of dealumination and the subsequent formation of hydrated, extra-framework aluminum species.

Figure 4.

27Al MAS NMR spectra of: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

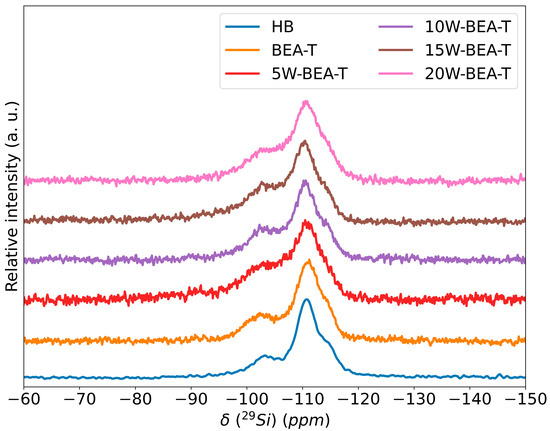

Table 3 presents the relative distribution of Q4 [Si(0Al)] and Q3 [Si(1Al)] silicon environments, based on the deconvolution of 29Si MAS NMR spectra, as well as the tetrahedral and octahedral aluminum environments determined from 27Al MAS NMR spectral deconvolution [29]. Hydrolytic cleavage of Si–O–Al bonds results in the formation of Si–O− defects, leading to a reduction in Q4 signals (−111, −115 ppm) and an increase in Q3 signals (−102 ppm) observed in the 29Si MAS NMR spectra (Figure 5).

Table 3.

Relative distribution (%) of tetrahedral (Al-Td) and octahedral (Al-Oh) aluminum species, and silicon environments Q3 and Q4, according to 27Al and 29Si MAS NMR spectra.

Figure 5.

29Si MAS NMR spectra of: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

On the other hand, the tetrahedral aluminum species increased after the alkaline–acid treatment, followed by impregnation with a small amount of WO3 (5W-BEA-T). This was accompanied by a reduction in octahedral aluminum species, likely due to the HCl washing step, which removed deposited EFAL species (Figure 4) [17,29].

The 29Si MAS NMR spectra (Figure 5) of BEA-T showed that the Q3 signal at −102 ppm remained virtually unchanged compared to the HB sample. Likewise, the Q4 environments at −111 ppm and −115 ppm were not affected, even after the addition of tungsten.

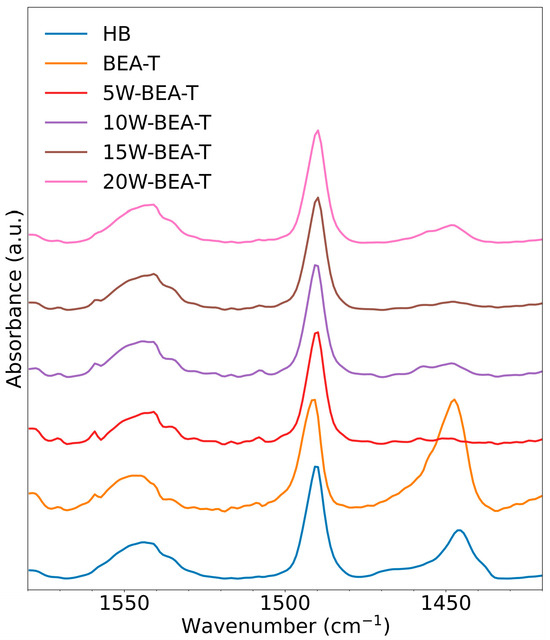

2.5. Acidity of the Catalysts Determined by Pyridine Adsorption

Dealumination followed by WO3 impregnation affected both the quantity (Table 4) and strength of the acid sites, increasing the population of weak acid sites (WAS) (Figure 6) and thus enabling the design of an efficient catalyst for the low-temperature dehydration of ethanol to ethylene. After post-synthesis treatment, the total quantity of adsorbed pyridine (NPy, mmol/g) on the catalysts obtained by pyridine-TPD (TG/DTG) analysis decreased because pyridine molecules preferentially interact with stronger Brønsted acid sites, as these interactions have a more negative associated free energy (Table 4). Infrared spectra of the samples collected after gaseous pyridine adsorption showed that the HB zeolite displayed higher band intensity in the region between 1580 and 1420 cm−1 (Figure 6). These bands correspond to the interaction of pyridine with Brønsted acid sites (1544 cm−1), Lewis acid sites (1445 cm−1), and a combined interaction band at 1490 cm−1, attributed to both acid site types [10,17]. The BEA-T sample showed an intense Lewis band, consistent with the signal around 0 ppm of the 27Al MAS NMR spectrum. Lewis acid sites may also originate from aluminum-based species such as Al3+, Al(OH)2+, Al(OH)2+, AlOOH, Al(OH)3 and Al2O3 which feature coordinatively unsaturated surface sites. Extra-framework aluminum species can significantly enhance the stability and catalytic performance of zeolites. Zhao et al. [30] demonstrated the reversible transformation between octahedrally and tetrahedrally coordinated framework aluminum in the BEA zeolite, highlighting the dynamic nature of aluminum speciation in these materials. In addition, Choi et al. [31] reported that mesoporous WO3 predominantly exposes Lewis acid sites, which are associated with isolated and coordinatively unsaturated W(VI) centers. In contrast, Brønsted acid sites are primarily dependent on the presence of polytungstate polymeric species.

Table 4.

Total quantity of adsorbed pyridine (NPy) on the catalysts obtained by Py-TPD (TG/DTG) analysis. The error is ±0.02 mmol/g.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of pyridine adsorbed on: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

The WO3 impregnated on BEA-T interacts with the surface of the zeolite, particularly at Lewis sites. Lewis acid sites are EFAL species or aluminum atoms with a lower coordination number (defects) on the surface or within the structural framework. The samples with 5 and 10% WO3/BEA-T showed a partial suppression of the Lewis acid band (1445 cm−1), which can be ascribed to the likely interaction of WO3 species with these EFAL species on the surface of BEA-T. WO3 itself has Lewis and Brønsted acid sites, and it tends to increase the quantity of these sites with increasing loading (15 and 20% WO3). Thus, pyridine interacts mainly with the W(VI) Lewis sites of WO3, which increase with higher WO3 loading, reflecting the increase in the Lewis bands in the FT-IR spectra. Certainly, pyridine also interacts with Brønsted sites that are also present, originating from either WO3 or the zeolite.

2.6. Analyses by SEM Micrographs

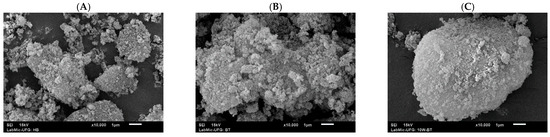

The morphologies of HB, BEA-T, and 10W-BEA-T (the sample that exhibited the best catalytic performance in dehydration reactions, vide next section) were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the qualitative results are shown in Figure 7. The SEM micrographs revealed that HB consists of highly aggregate particles with a rough surface morphology and with uniform crystalline structures resembling rounded grains, as reported in the literature [23].

Figure 7.

SEM images of: (A) HB, (B) BEA-T, and (C) 10W-BEA-T.

Treatment with NaOH and HCl was employed to modify the zeolite material. The use of NaOH primarily acts on the superficial Si–O bonds, resulting in minor structural deformation of the zeolite. This step introduces limited changes to the overall morphology by breaking select silicon-oxygen linkages on the external surface. Subsequently, HCl treatment selectively removes extra-framework aluminum species from the structure. Importantly, this process does not cause severe damage to the microporous framework of the zeolite. As a result, the material maintains morphological characteristics similar to the parent zeolite, with the combined chemical treatments facilitating controlled modification while preserving the essential microporous architecture [32]. It was observed that there was a shrinking in the particle size and the creation of intercrystalline mesoporosity in BEA-T in agreement to textural parameters (Table 2). This enhanced accessibility of the new acid sites and faster diffusion of products improved the catalyst’s performance.

The SEM images of WO3 showed loosely aggregated plate-like nanoparticles, consistent with the literature [27]. The 10W-BEA-T catalyst exhibited a rough morphology with granular crystals, and particle size remained largely unchanged after modification when compared to the parent zeolites. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirmed the presence of tungsten (W) (Figure S3).

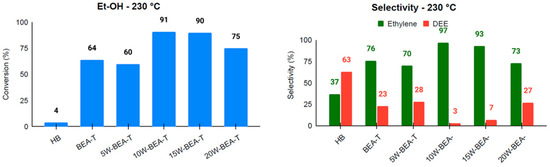

2.7. Ethanol and 1-Propanol Catalytic Dehydrations

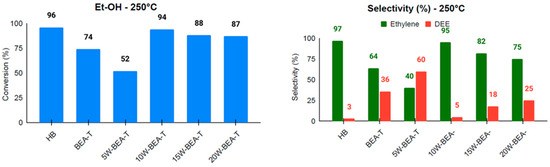

Catalysis has become a highly relevant technology in achieving the goals of sustainable chemistry [33], and zeolites, especially *BEA-type structures, have been widely used as catalysts in various research areas focused on sustainability. To enhance these catalytic processes, it is anticipated that zeolite hierarchization will facilitate the diffusion of reactants, promote the release of products, and improve access to catalytic sites. Previous studies from our group involving the hierarchization of *BEA zeolite using ammonium hexafluorosilicate under solid-state conditions have shown the generation of secondary mesopores and enhanced ethanol diffusion to catalytically active sites, resulting in the conversion of ethanol into two main products: ethylene and diethyl ether [10]. Accordingly, the ethanol dehydration reaction was carried out at 230 °C and 250 °C, and the conversion and selectivity results are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. The results are described from the viewpoint of three parameters: ethanol conversion, ethylene selectivity, and TON (turnover number) for ethylene formation (Table S1). Compared to HBEA, at 230 °C, the BEA-T catalyst showed a significant improvement in all three parameters, while at 250 °C the selectivity and TON for ethylene underwent a decrease. This is consistent with both the decrease in total acid sites and the creation of additional mesopores in BEA-T, since the diffusion of reactants and products might have compensated for the loss of acidity in the acid-catalyzed reaction. The higher temperature likely led to the loss in selectivity because it promoted side reactions in the BEA-T zeolite, which has more Lewis acid sites.

Figure 8.

Conversion and selectivity for ethanol dehydration at 230 °C for the catalysts: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

Figure 9.

Conversion and selectivity for ethanol dehydration at 250 °C for the catalysts: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

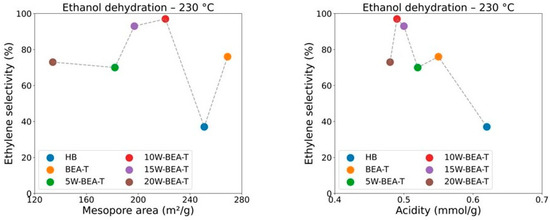

The impregnation of WO3 onto hierarchized BEA generated materials with a lower total number of accessible sites, as determined by Py-TPD, and likely weaker acid sites (WAS), as also observed for Nb2O5–BEA-T catalysts [17] and α-Fe2O3-BEA catalysts [34]. The results for both reaction temperatures, 230 and 250 °C, clearly showed an enhancement trend in all three parameters, with a maximum activity for 10W-BEA-T (at 230 °C: 91% ethanol conversion, 97% selectivity to ethylene, TON = 0.95; at 250 °C: 94% ethanol conversion, 95% selectivity to ethylene, TON = 1.64). The BEA-T zeolite exhibited an increased Si/Al ratio after treatment and WO3 impregnation, indicating that dealumination took place. The surface of BEA-T anchored WO3 species that contributed to both Brønsted and Lewis acid sites. Therefore, the observed high selectivity toward ethylene during the catalytic dehydration of ethanol can be attributed to two key factors. First, a moderate reduction in the acidity of the zeolite material, which created a more controlled catalytic environment, minimizing excessive side reactions. Second, controlled tuning of the mesoporous area appears to play an important role by enhancing the spatial environment needed to facilitate more efficient diffusion of ethylene molecules. These combined effects allowed for improved access to active sites and promoted the effective release of ethylene from the catalyst structure, resulting in the notable selectivity observed in the reaction. The correlation between ethylene selectivity and either mesoporous area or the number of acid sites supports this idea, showing maximum activity for the catalyst with 10 wt.% WO3 loading (Figure 10). In addition, a performance test using the 10W-BEA-T catalyst with 50 ethanol pulses at 230 °C showed a decrease to 85% ethanol conversion and 79% ethylene selectivity. The ethylene selectivity was about 17% lower than after a single pulse, likely due to coke buildup on the catalyst surface. CHN analysis confirmed around 1% carbon residue on the catalyst after 50 pulses, supporting this explanation for deactivation.

Figure 10.

Correlations between ethylene selectivity and mesopore area or acidity of the catalysts.

The catalytic dehydration of 1-propanol has been extensively studied due to its importance in producing valuable chemicals such as olefins and ethers [35]. A substantial body of research has examined the mechanistic pathways involved in this reaction, with particular attention to how catalyst composition influences product distribution [36]. It is widely accepted that a combination of active site accessibility and acidity plays a decisive role in directing the reaction pathway. Among these, Brønsted acid sites typically play a critical role in enabling the transformation of 1-propanol into either olefins or ethers.

The dehydration process generally begins with the adsorption of 1-propanol onto the catalyst surface, forming an alkoxy intermediate. This is followed by the elimination of water through an E1 (unimolecular elimination) mechanism, leading to the formation and subsequent desorption of propene. A key step in this mechanism involves the stabilization of a carbocation-like transition state, which is considered the primary factor influencing the rate of unimolecular dehydration. Improved stabilization of this intermediate generally results in higher selectivity toward olefin (propene) formation [37,38,39]. Alternative reaction pathways may involve the formation of dimers or trimers of adsorbed 1-propanol, which are favored under certain pressure conditions.

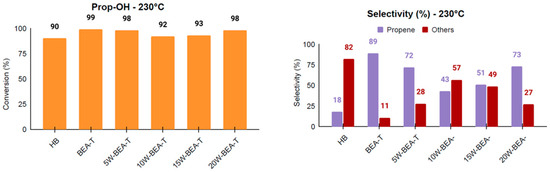

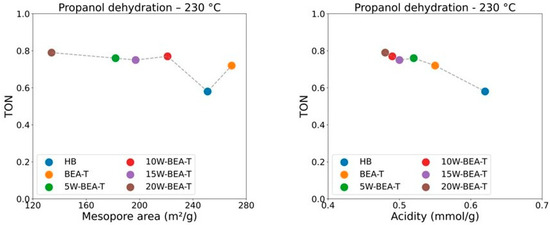

For the 1-propanol dehydration reaction at 230 °C, BEA-T exhibited the highest performance, achieving 99% conversion and 89% selectivity to propene (Figure 11), which confirms the importance of increased mesopore formation as a key factor in enhancing propene selectivity. Given that 1-propanol is a larger molecule than ethanol, the superior performance of the BEA-T catalyst can likely be attributed to its higher total pore volume, which may enhance the stabilization and accommodation of multimeric intermediates within the zeolitic framework during the reaction. However, when taking the TON into consideration (Table S2), an increase in WO3 loading on BEA-T resulted in the best activities, with the 20% loading being the most active. Again, the correlation between propene selectivity and either mesoporous area or the number of acid sites (Figure 12) supports this behavior, showing maximum activity for 20W-BEA-T, which demonstrates that these factors are critical in contributing to the improved performance of the WO3-supported catalysts.

Figure 11.

Conversion and selectivity for propanol dehydration at 230 °C for the catalysts: HB, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, and 20W-BEA-T.

Figure 12.

Correlations between propene TON and mesopore area or acidity of the catalysts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Hierarchization of *BEA Zeolite and Impregnation of WO3

Ammonium-form BEA zeolite NH4BEA, obtained from Zeolyst International (CP814E, Kansas City, KS, USA), with a mole ratio of SiO2/Al2O3 = 25, was calcined at 550 °C for 8 h, resulting in the formation of a proton-form sample (HB). The hierarchization procedure treated HB with a 0.2 M sodium hydroxide solution (97%, Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), under magnetic stirring at 75 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the mixture was washed with deionized water (75 °C for 1 h) and the resulting material was treated with a 0.5 M hydrochloric acid solution (37%, Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) under the same conditions as the basic treatment. The material was washed again, and the resulting zeolite was dried (120 °C for 12 h) and calcined (550 °C for 8 h). The impregnation of tungsten oxide into the hierarchical *BEA zeolite was obtained by aqueous impregnation. The sample was dried (200 °C for 4 h) under vacuum to remove adsorbed water molecules and based on the mass of the dry materials, the amount of ammonium tungstate (NH4)10H2(W2O7)6 (99.99%, Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to be used (5, 10, 15, and 20 wt.%) was determined. The solutions containing tungsten and zeolite were placed under magnetic stirring at 90 °C until complete evaporation of the solvent. Finally, the resulting materials were kept dry in an oven (120 °C for 12 h), followed by calcination (550 °C for 8 h). Table 5 presents the nomenclature used to identify the different samples.

Table 5.

Nomenclature used for studying *BEA zeolite.

3.2. Experimental Methods of Characterization

3.2.1. Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were collected using a PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer (Malvern, UK) equipped with a copper anode (Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 40 kV and 45 mA. Scans were performed over the 2θ range of 2° to 60°, with a scan rate of 2° min−1 and a step size of 0.02°.

The relative crystallinity (%C) of the samples was determined by comparing their diffraction patterns to that of a standard HB zeolite. This involved integrating the area under the characteristic peaks between 5° and 60° (2θ), following Equation (1).

3.2.2. Elemental Analysis

Elemental analysis of silicon, aluminum, and tungsten was performed using a Shimadzu EDX-720 energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (EDXRF) spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan). Samples were prepared using polypropylene film and analyzed under vacuum conditions using a rhodium (Rh) X-ray target, with an operating voltage range of 15–50 kV, to determine the total Si/Al molar ratio.

3.2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Infrared spectra were collected using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer (Madison, WI, USA), with 512 scans at 4 cm−1 resolution, analyzing the 4000–430 cm−1 range. Samples typically involved 0.6 wt.% of the catalyst mixed into dried, high-purity (>99%) Merck (Rahway, NJ, USA) KBr pellets. Samples typically consisted of pellets with 0.6 wt.% of the catalyst mixed with dried, high-purity KBr (>99%, Merck, São Paulo, Brazil).

3.2.4. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectra were acquired using a LabRAM HR Evolution spectrometer (Horiba, Palaiseau, France) under ambient conditions (25 °C). A 795 nm excitation laser was employed at a power setting of 9 mW. Each spectrum was recorded over 64 accumulations, with a spectral resolution of 2 cm−1.

3.2.5. Textural Properties

Textural data were obtained by gaseous physisorption of N2 at low temperature (−196 °C) in a Micromeritics analyzer (ASAP 2020C, Norcross, GA, USA). Prior to analysis, samples were degassed with evacuation (target pressure of 50 μm Hg) at 300 °C for 4 h.

The main parameters obtained from the analysis of the isotherms were: specific surface area (SBET), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), in the range of 0.01 < P/P0 < 0.1; micropore area (SMicro) and micropore volume (VMicro), calculated using the t-plot method of Harkins and Jura; total pore volume (Vp), determined from desorption at P/P0 = 0.99, according to the Gurvitch Rule; mesoporous area (SMeso = SBET − SMicro) and mesoporous volume (VMeso = Vp − VMicro).

3.2.6. Microscopy Analysis

SEM imaging was conducted on a JEOL JSM instrument (Peabody, MA, USA) under high vacuum at 15 kV, using a secondary electron detector (LED, Low Energy Detector) to capture images at magnifications from 100× to 10,000×. The SEM microscope was equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) from Thermo Scientific NSS Spectral.

3.2.7. Solid-State 27Al and 29Si Magic Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Solid-state NMR spectra were acquired for the catalysts using a Bruker Avance III HD Ascend spectrometer (14.1 T, 600 MHz for 1H, Billerica, MA, USA), equipped with 2 mm or 4 mm CP/MAS probes, employing magic angle spinning (MAS) technique. Catalysts were packed into 4 mm zirconia rotors, and specific acquisition parameters were applied for each nucleus: (i) 27Al MAS NMR (156.4 MHz) was recorded at a spinning rate of 10 kHz, using a 0.4 µs pulse duration (π/20) and a 1 s recycle delay, over 2000 scans. Spectra were referenced to hexa(aqua)aluminum(III) trichloride, [Al(H2O)6]Cl3 (δ = 0 ppm); (ii) 29Si MAS NMR (119.3 MHz) was recorded at a spinning rate of 10 kHz, with a 4.25 µs pulse duration (π/2) and a 20 s recycle delay, over 3072 scans, referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS), Si(CH3)4 (δ = 0 ppm).

The relative distribution of aluminum atoms in the zeolite framework was determined from the 27Al MAS NMR spectra, distinguishing between octahedral (AlOh) and tetrahedral (AlTd) coordination environments, using Equation (2). The framework Si/Al molar ratio was calculated based on the deconvolution of 29Si MAS NMR spectra, using Equation (3).

The 29Si spectra, which identify silicon environments such as Q4, Q3, Q2, and Q1, were deconvoluted using a Gaussian–Lorentzian fitting function implemented in Python (Version: 3.9.7 (default, 16 September 2021, 16:59:28), Wilmington, DE, USA), with a line broadening (LB) of 10.

The intensity ISi(Al) represents the NMR signal corresponding to silicon atoms bonded to n aluminum atoms, with the intensity being proportional to the population of such silicon environments. The total number of silicon atoms (numerator in the Si/Al ratio) is calculated as the sum of all Si(nAl) species observed. According to Löwenstein’s rule, which prohibits the formation of Al–O–Al linkages in zeolite frameworks, each aluminum atom is tetrahedrally coordinated by four silicon atoms. Consequently, each Si(nAl) environment corresponds to one-fourth of an aluminum atom, and the total number of aluminum atoms (denominator) is calculated as ¼ × Σ[n × ISi(nAl)]. This relationship is used to estimate the framework Si/Al ratio based on the relative intensities obtained from the deconvoluted 29Si MAS NMR spectra.

3.2.8. Acidity of the Catalysts

To evaluate acidity via pyridine adsorption, approximately 20 mg of catalyst was loaded into an aluminum crucible placed inside a borosilicate glass tube. The sample was dehydrated under a nitrogen (N2) flow at 300 °C for 1 h using a tubular furnace (Thermolyne, model F21100, Waltham, MA, USA). After cooling to 150 °C, gaseous pyridine (>99.8%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was passed over the sample for 1 h, followed by an additional 1-h purge at 150 °C in N2 (5.0 grade, White Martins, São Paulo, Brazil) to remove physiosorbed pyridine. Subsequently, the sample was cooled and immediately prepared as an approximately 6 wt.% catalyst/KBr mixture for FT-IR analysis. The total quantity of acid sites was calculated by Py-TPD (via TG/DTG), which has been described elsewhere [18].

3.2.9. Catalytic Dehydration Reactions

Ethanol (99.5%, Neon, Suzano, São Paulo, Brazil) or 1-propanol PA (99.5%, Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) dehydration reactions were evaluated by three injections of alcohol under 10 mg of catalyst in a pulse microreactor coupled to a gas chromatograph with flame ionization detector (Shimadzu GC-FID, model 2010, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a Shimadzu CBP1 PONA column (M50-042, 50 m × 0.15 m × 0.33 μm). The reactions were carried out at 250 °C under the following conditions: alcohol injection volume: 0.5 μL; pressure: 95.6 kPa; total flow: 6 mL/min; column flow: 0.1 mL/min; linear velocity: 6.4 cm/s; purge flow: 1 mL/min; split ratio: 49; column temperature: 35 °C; flame temperature: 250 °C. The performance of the catalysts in the ethanol reaction was evaluated after a sequence of 50 pulses of 0.5 μL each, followed by the analysis of conversion and selectivity.

The calculations for reactant conversion and product selectivity (ethylene (EE), dimethyl ether (DME), and propene (PP)) were determined using Equations (4)–(7), where n represents the molar quantity of the reactant. The reported values are the average of the three pulses.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the hierarchization of *BEA zeolite followed by surface modification with tungsten trioxide (WO3) and its effects on catalytic performance in the dehydration of ethanol and 1-propanol. The hierarchical structure was achieved via sequential post-synthetic treatments using 0.2 M sodium hydroxide and 0.5 M hydrochloric acid (referred to as T-NaOH-HCl) forming BEA-T. After this treatment, WO3 was impregnated onto the BEA-T zeolite at loadings of 5, 10, 15, and 20 wt.%. Hierarchization induced several notable structural and textural changes. The SiO2/Al2O3 molar ratio increased from 25 to 39, indicating silica enrichment. Relative crystallinity decreased by 15%, and the average crystalline domain size was reduced from 18 nm to 10 nm. The mesoporous surface area increased from 251 to 269 m2/g, and the total pore volume increased from 0.90 to 1.01 cm3/g. A slight increase in tetrahedrally coordinated aluminum was also observed by 27Al and 29Si MAS NMR. WO3 crystallites on BEA-T ranged from 11 nm (5W-BEA-T) to 50 nm (20W-BEA-T), in contrast to bulk WO3 (70 nm), suggesting nanocrystal dispersion on the zeolite surface (a conclusion further supported by SEM analysis).

Catalytic testing for ethanol dehydration at 230 °C and 250 °C revealed that the catalyst impregnated with 10 wt.% WO3 exhibited the highest performance, achieving 94% conversion and 95% selectivity to ethylene at 250 °C. At 230 °C, the same material achieved 91% conversion and 97% selectivity to ethylene. In contrast, for 1-propanol dehydration at 230 °C, the BEA-T sample (without WO3) outperformed all others, reaching 99% conversion and 89% selectivity to propene. However, based on TON calculations, 20 wt.% WO3/BEA-T was the best catalyst, highlighting the importance of the relative active sites in these reactions. The high conversion and selectivity observed in the dehydration of both ethanol and 1-propanol can be attributed to a moderate reduction in the acidity of the BEA zeolite and tuned mesoporosity. Thus, these results highlight the complementary roles of hierarchical structuring and WO3 functionalization in tuning acidity and improving catalytic performance for alcohol dehydration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121170/s1, Figure S1. N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms (at −196 °C) of the catalysts: HBEA, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, 20W-BEA-T, and WO3; Figure S2. T-plot curves based on N2 adsorption/desorption data of the catalysts: HBEA, BEA-T, 5W-BEA-T, 10W-BEA-T, 15W-BEA-T, 20W-BEA-T, and WO3; Figure S3. EDS analyses from the SEM images of the catalysts: (A) H-BEA, (B) BEA-T, and (C) 10W/BEA-T; Table S1. Dehydration of ethanol (230 and 250 °C), conversion (Conv), selectivity for ethylene (Sel Ety) and turnover number (TON) for ethanol conversion (mole converted ethanol/mole acid sites) calculated after one pulse of ethanol; Table S2. Dehydration of 1-propanol (230 °C), conversion (Conv), selectivity (Sel) for propene (Sel Prp) and turnover number (TON) for 1-propanol conversion (mole converted 1-propanol/mole acid sites) calculated after one pulse of 1-propanol.

Author Contributions

D.d.S.V. conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing. R.C.F. conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing—review & editing. W.H.R.d.C. data curation, investigation, methodology. J.A.D. conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—review & editing. S.C.L.D. conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq (Grants 308693/2022-1 and 305397/2025-7); Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, CAPES (Grant 001); Decanato de Pesquisa e Inovação (DPI) and Instituto de Química (IQ) from Universidade de Brasília (DPI/IQ/UnB); Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAPDF) (Grants 00193-000001176/2021-65 and 00193-00001144/2021-60); Fundação de Empreendimentos Científicos e Tecnológicos (FINATEC); Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos, FINEP/CTPetro/CTInfra; Petrobras. APC was provided by University of Brasília-Brazil and MDPI.

Data Availability Statement

All data are within the article and the Supplementary Materials. Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Richieli Vieira (commercial development coordinator, PQ Silicas Brazil) for providing *BEA zeolite (CP814E*). In addition, we would like to thank Tatiane Oliveira dos Santos from Laboratório Multiusuário de Microscopia de Alta Resolução (LabMic) at IF/UFG-Brazil for Raman and SEM/EDX measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy, 73rd ed.; Energy Institute: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alabdullah, M.A.; Shoinkhorova, T.; Dikhtiarenko, A.; Ould-Chikh, S.; Rodriguez-Gomez, A.; Chung, S.; Alahmadi, A.O.; Hita, I.; Pairis, S.; Hazemann, J.; et al. Understanding Catalyst Deactivation during the Direct Cracking of Crude Oil. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 5657–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yan, W.; Xu, R. Chiral Zeolite Beta: Structure, Synthesis, and Application. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treacy, M.M.J.; Newsam, J.M. Two New Three-Dimensional Twelve-Ring Zeolite Frameworks of Which Zeolite Beta is a Disordered Intergrowth. Nature 1988, 332, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; El-Hiti, G.A. Use of Zeolites for Greener and More Para-Selective Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Reactions. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 1579–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Abelló, S.; Villaescusa, L.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Mesoporous Beta Zeolite Obtained by Desilication. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 114, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.; Machoke, A.G.; Schwieger, W. Catalytic Test Reactions for the Evaluation of Hierarchical Zeolites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3313–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verboekend, D.; Mitchell, S.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Hierarchical Zeolites Overcome All Obstacles: Next Stop Industrial Implementation. Chimia 2013, 67, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-H.; Sun, M.-H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Xie, Z.; Su, B.-L. Hierarchically Structured Porous Materials: From Nanoscience to Catalysis, Separation, Optics, Energy, and Life Science. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11194–11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadares, D.S.; Carvalho, W.H.R.; Fonseca, A.L.F.; Machado, G.F.; Silva, M.R.; Campos, P.T.A.; Dias, J.A.; Dias, S.C.L. Different Routes for the Hierarchization of *BEA Zeolite, Followed by Impregnation with Niobium and Application in Ethanol and 1-Propanol Dehydration. Catalysts 2025, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Moulijn, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Decoupling mesoporosity formation and acidity modification in ZS-5 zeolites by sequential desilication-dealumination. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 87, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberg, D.M.; Hausmann, H.; Hölderich, W.F. Dealumination of zeolite bea by acid leaching: A new insight with two-dimensional multi-quantum and cross polarization 27Al MAS NMR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 3128–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, F.; Courtois, X.; Duprez, D. Tungsten-Based Catalysts for Environmental Applications. Catalysts 2021, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, W.V.; Nutt, M.O.; Wong, M.S. Supported Metal Oxides and the Surface Density Metric. In Catalyst Preparation, Science & Engineering; Regalbuto, J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Chapter 11; pp. 251–282. [Google Scholar]

- Tohdee, K.; Semmas, S.; Nonthawong, J.; Praserthdam, P.; Pungpo, P.; Jongsomjit, B. Characteristics and Catalytic Properties of WO3 Supported on Zeolite A-Derived from Fly Ash of Sugarcane Bagasse via Esterification of Ethanol and Lactic Acid. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 49, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.; Riad, M. Catalysts for the Non-Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethanol Supported by WO3-Based Micro-Mesoporous Composites. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 205, 112789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadares, D.S.; Clemente, M.C.H.; Freitas, E.; Martins, G.A.V.; Dias, J.A.; Dias, S.C.L. Niobium on BEA Dealuminated Zeolite for High Selectivity Dehydration Reactions of Ethanol and Xylose into Diethyl Ether and Furfural. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.P.V.; Campos, P.T.A.; Paiva, M.F.; Linares, J.J.; Dias, S.C.L.; Dias, J.A. Dehydration of Fructose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural: Effects of Acidity and Porosity of Different Catalysts in the Conversion, Selectivity, and Yield. Chemistry 2021, 3, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, S.; Gao, H.; Wen, D. Metal-Modified Zeolites for Catalytic Dehydration of Bioethanol to Ethylene: Mechanisms, Preparation, and Performance. Catalysts 2025, 15, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xiao, Z.; Guo, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Feng, M.; Zou, J.; Li, G.; Wang, D. Advancements in Catalyst Design and Reactor Engineering for Efficient Olefin Synthesis from Alcohol (C2+) Dehydration. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 321, 122719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, M.A.; Clemente, M.C.H.; Martins, G.A.V.; Da Silva, L.C.C.; Fantini, M.C.A.; Dias, S.C.L.; Dias, J.A. Silver Salts of 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid Supported on SBA-15: Effect of Enhanced Specific Surface Area on Ethanol Dehydration. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2025, 51, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstens, D.; Smeyers, B.; Waeyenberg, J.V.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Sels, B.F. State of the Art and Perspectives of Hierarchical Zeolites: Practical Overview of Synthesis Methods and Use in Catalysis. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2004690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, P.; Bekhti, S.; Kunkes, E.; Iemhoff, A.; Bottke, N.; Vos, D.E.; Meng, X.; Xiao, F.; et al. Needle-like Hierarchical Beta Zeolite Synthesis via Postsynthetic Morphology Control in the Presence of Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide for Catalytic Dehydration of Sorbitol. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Rigolet, S.; Michelin, L.; Paillaud, J.; Mintova, S.; Khoerunnisa, F.T.; Daou, J.; Ng, E. Facile and Fast Determination of Si/Al Ratio of Zeolites Using FTIR Spectroscopy Technique. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 311, 110683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailova, B.; Valtchev, V.; Mintova, S.; Faust, A.-C.; Petkova, N.; Bein, T. Interlayer stacking disorder in zeolite beta family: A Raman spectroscopic study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Lin, C.-K. Fabrication and optical properties of Ti-doped W18O49 nanorods using a modified plasma-arc gas-condensation technique. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2009, 27, 2170–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulhakem, O.; Rezki, B. In Situ Growth of Tungstite (WO3·H2O) on Microporous and Mesoporous Silicas for Enhanced Oxygen-Evolving Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2025, 129, 10518–10530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestakova, P.; Martineau, C.; Mavrodinova, V.; Popova, M. Solid State NMR Characterization of Zeolite Beta Based Drug Formulations Containing Ag and Sulfadiazine. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 81957–81964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xu, S.; Hu, M.Y.; Bao, X.; Peden, C.H.F.; Hu, J. Investigation of Aluminum Site Changes of Dehydrated Zeolite H-Beta during a Rehydration Process by High-Field Solid-State NMR. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 1410–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Lee, E.; Jin, M.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, J.M.; Jeon, J.K. Catalytic Properties of Highly Ordered Crystalline Nanoporous Tungsten Oxide in Butanol Dehydration. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014, 14, 8828–8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yamamoto, S.; Sugiyama, S.; Matsuoka, O.; Kohmura, K.; Honda, T.; Banno, Y.; Nozoye, H. Dissolution of Zeolite in Acidic and Alkaline Aqueous Solutions as Revealed by AFM Imaging. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 18474–18482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.M.; Paiva, M.F.; de França, J.O.C.; Dias, S.C.L.; Dias, J.A. Synthesis and Properties of *BEA Zeolite Modified with Iron(III) Oxide. Inorganics 2025, 13, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis and Sustainable (Green) Chemistry. Catal. Today 2003, 77, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, T.K.; Pham, T.L.M.; Vu, K.B.; Busca, G. (Bio)Propylene production processes: A critical review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte, J.; Nachtergaele, P.; Mahmoud, M.; Vleeming, H.; Thybaut, J.W.; Poissonnier, J.; Dewulf, J. Developing Circularity, Renewability and Efficiency Indicators for Sustainable Resource Management: Propanol Production as a Showcase. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 379, 134843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, M.S.; Camaioni, D.M.; Gutiérrez, O.Y.; Glezakou, V.A.; Govind, N.; Huthwelker, T.; Zhao, R.; Rousseau, R.; Fulton, J.L.; et al. Self-Organization of 1-Propanol at H-ZSM-5 Brønsted Acid Sites. JACS Au 2023, 3, 2487–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, Y.; Shi, H.; Mu, L.; Liu, Y.; Mei, D.; Camaioni, D.M.; Lercher, J.A. Dehydration Pathways of 1-Propanol on HZSM-5 in the Presence and Absence of Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 15781–15794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, M.E.; Amsler, J.; Spiske, L.; Plessow, P.N.; Asare, T.; Carravetta, M.; Raja, R.; Cox, P.A.; Studt, F.; Armstrong, L.M. Combining Theoretical and Experimental Methods to Probe Confinement within Microporous Solid Acid Catalysts for Alcohol Dehydration. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 5955–5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).