Boosting Photocatalysis: Cu-MOF Functionalized with g-C3N4 QDs for High-Efficiency Degradation of Congo Red

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Result and Discussion

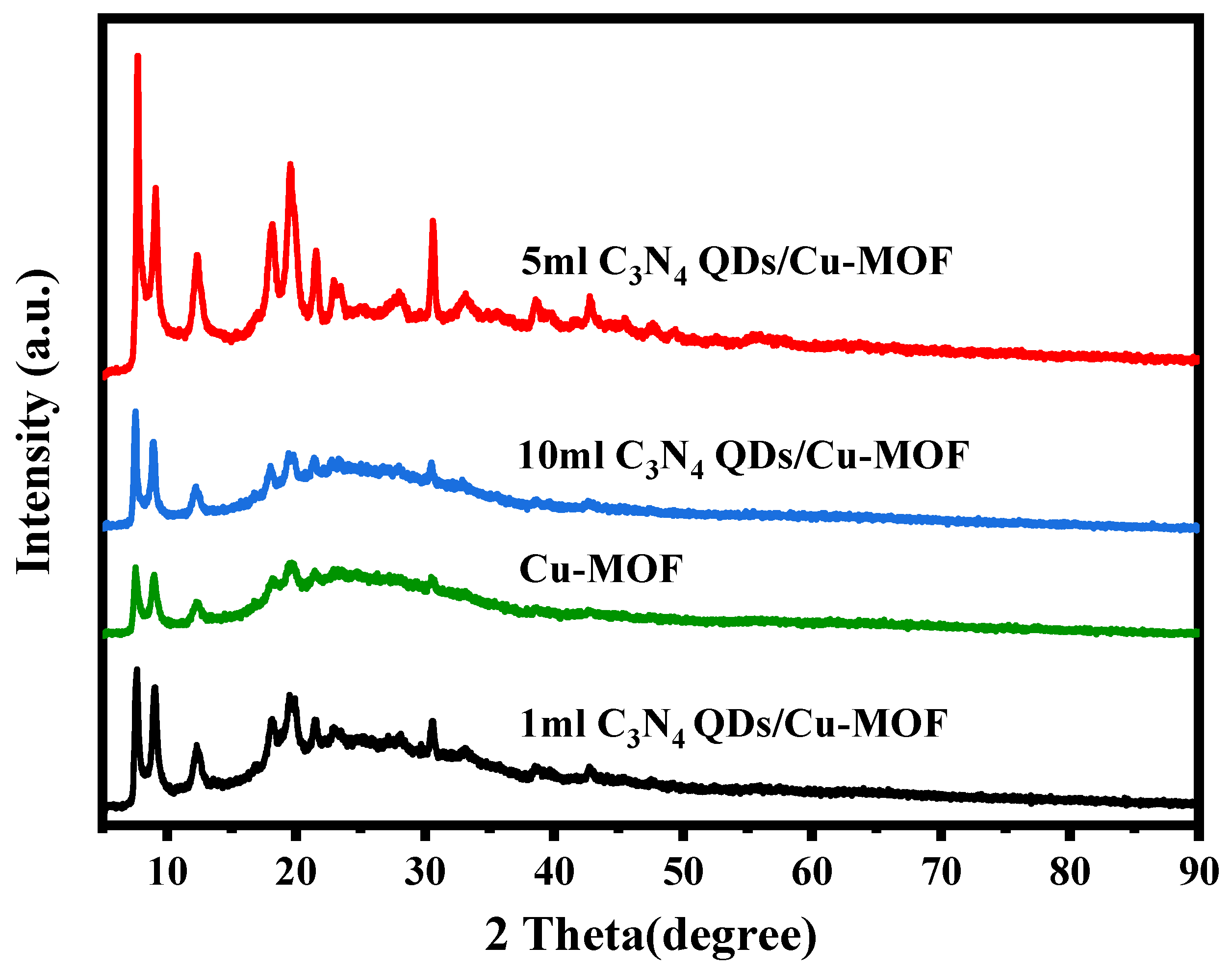

2.1. Characterization

2.2. Photoluminescence Spectra and Photoelectric Properties

2.3. Analysis of Photodegradation Performance

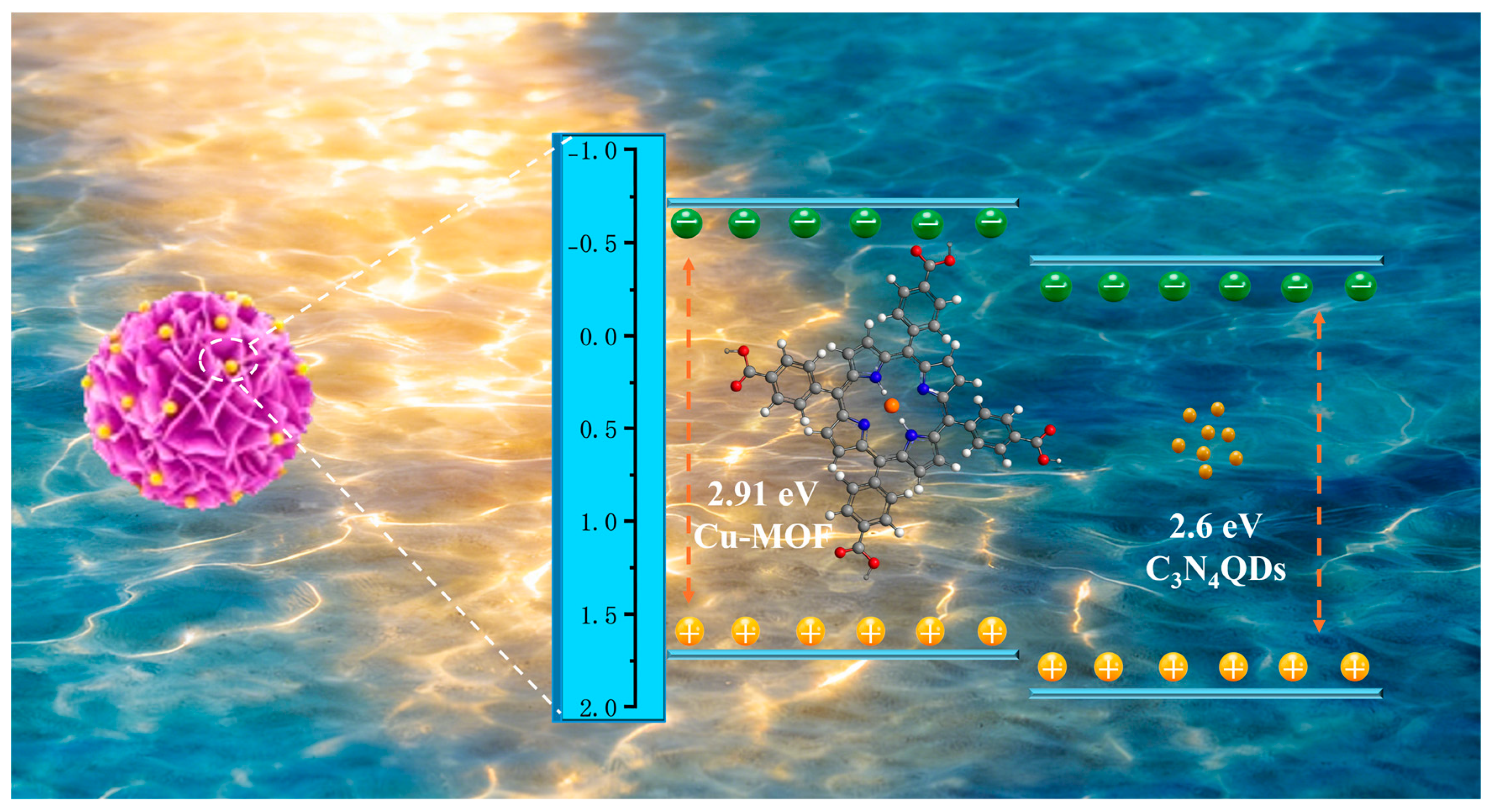

2.4. Photocatalytic Degradation Mechanism

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials and Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of Tcpp

3.3. Preparation of Cu-Tcpp

3.4. Synthetic Copper-Based Mof

3.5. Synthesis of C3N4QDs

3.6. Preparation of Cu-Mof/C3N4QDs

3.7. The Electrochemical and Photoelectrochemical Measurements

3.8. Light Degradation Performance Test

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skorjanc, T.; Shetty, D.; Trabolsi, A. Pollutant removal with organic macrocycle-based covalent organic polymers and frameworks. Chem 2021, 7, 882–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S.; Horcajada, P. Metal-Organic Frameworks for the Removal of Emerging Organic Contaminants in Water. Chem. Rev. 2020, 16, 8378–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, X. Persistent organic pollutant cycling in forests. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, L.; Long, T.; Geng, C.; Tian, X. Migration and remediation of organic liquid pollutants in porous soils and sedimentary rocks: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 21, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lu, Y.-L.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Cheng, P.; Yang, S.; Shi, W. Efficient Recognition and Removal of Persistent Organic Pollutants by a Bifunctional Molecular Material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 145, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Fourmentin, M.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Mapelli, F.; Fenyvesi, É.; Vieira, M.G.A.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C.; et al. Removal of emerging contaminants from wastewater using advanced treatments. A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1333–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, B.; Singh, A.K.; Kim, H.; Lichtfouse, E.; Sharma, V.K. Treatment of organic pollutants by homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton reaction processes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandclément, C.; Seyssiecq, I.; Piram, A.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P.; Vanot, G.; Tiliacos, N.; Roche, N.; Doumenq, P. From the conventional biological wastewater treatment to hybrid processes, the evaluation of organic micropollutant removal: A review. Water Res. 2017, 111, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, X.-X.; Lv, Y.-K. Functionalized metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in environment. Chemosphere 2019, 242, 125144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Fajardo, A.R.; Iglesias, B.A. Supported porphyrins for the photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in water: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 20, 731–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusain, R.; Gupta, K.; Joshi, P.; Khatri, O.P. Adsorptive removal and photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using metal oxides and their composites: A comprehensive review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 272, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwaan, H.A.; Atwee, T.M.; Azab, E.A.; El-Bindary, A.A. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of Acid Red 57 using synthesized ZnO nanowires. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2018, 66, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dossoki, F.I.; Atwee, T.M.; Hamada, A.M.; El-Bindary, A.A. Photocatalytic degradation of Remazol Red B and Rhodamine B dyes using TiO2 nanomaterial: Estimation of the effective operating parameters. Desalination Water Treat. 2021, 233, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwaan, H.A.; Atwee, T.M.; Azab, E.A.; El-Bindary, A.A. Photocatalytic degradation of organic dyes in the presence of nanostructured titanium dioxide. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1200, 127115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Tian, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; He, Z. Recent advances of photocatalytic coupling technologies for wastewater treatment. Chin. J. Catal. 2023, 54, 88–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lin, H.; Hou, R.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhi, R.; Lu, X.; Tang, Y.; Chen, F. Modulating the microenvironment of catalytic interface with functional groups for efficient photocatalytic degradation of persistent organic pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 479, 147800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fei, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Li, B.; Shen, L.; Lin, H. MOF-Based Photocatalytic Membrane for Water Purification: A Review. Small 2023, 20, 2305066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.-S.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. Photodegradation of seven bisphenol analogues by Bi5O7I/UiO-67 heterojunction: Relationship between the chemical structures and removal efficiency. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2020, 277, 119222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, H.; Cordova, K.E.; O’Keeffe, M.; Yaghi, O.M. The chemistry and applications of metal-organic frameworks. Science 2013, 341, 1230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, J.; Liu, D.; Kang, R.; Yu, G.; Deng, S. Synthesis of mixed-linker Zr-MOFs for emerging contaminant adsorption and photodegradation under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroto, S.; Miyake, Y.; Shinokubo, H. Synthesis and Functionalization of Porphyrins through Organometallic Methodologies. Chem. Rev. 2016, 117, 2910–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, L.; Chu, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Ma, R.; Li, B.; Shen, L.; et al. Recent Advancement in 2D Metal–Organic Framework for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2419433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhou, E.; Tai, X.; Zong, H.; Yi, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, P.; Xu, H.; Jiang, Z. g-C(3)N(4) S-Scheme Homojunction through Van der Waals Interface Regulation by Intrinsic Polymerization Tailoring for Enhanced Photocatalytic H(2) Evolution and CO(2) Reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202425439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, S.; Xiong, W.; Yang, C.; Johannessen, B.; Liu, R.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Gu, Q.; Leung, M.K.H.; Shang, J. Atomically Dispersed Iron Metal Site in a Porphyrin-Based Metal–Organic Framework for Photocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9670–9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Su, R.; Lv, G.; Wang, Z.; Gao, B.; Zhou, W. Enhanced degradation of bisphenol F in a porphyrin-MOF based visible-light system under high salinity conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 132106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.-W.; Cong, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.; Che, L. Developing fine-tuned metal-organic frameworks for photocatalytic treatment of wastewater: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 433, 133605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, C.; Mou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H. Linker regulation of iron-based MOFs for highly effective Fenton-like degradation of refractory organic contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hu, G.; Dou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, M.; Feng, H.; Feng, Y.-S. Z-scheme promoted interfacial charge transfer on Cu/In-porphyrin MOFs/CdIn2S4 heterostructure for efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 354, 129220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulou, M.; Keller, V.; Christoforidis, K.C. Cu-Metalated Porphyrin-Based MOFs Coupled with Anatase as Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction: The Effect of Metalation Proportion. Energies 2024, 17, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ge, S.; Wu, M.; Jiang, J.; Fan, W.; Debecker, D.P.; Rezakazemi, M.; Zhang, Z. Progress in advanced MOF-derived materials for the removal of organic and inorganic pollutants. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 530, 216474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, J.; Sheng, G.; Deng, W.Q.; Wu, H. Concentration-Adaptive Electrocatalytic Urea Synthesis from CO2 and Nitrate via Porphyrin and Metalloporphyrin MOFs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202513441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, M.; Sengottuvelu, D.; Nouranian, S.; Al-Ostaz, A. Graphitic Carbon Nitride Quantum Dots (g-C3N4 QDs): From Chemistry to Applications. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. A critical review on graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-based materials: Preparation, modification and environmental application. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 453, 214338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxele, S.R.; Nyokong, T. Time-dependent characterization of graphene quantum dots and graphitic carbon nitride quantum dots synthesized by hydrothermal methods. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2022, 121, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-R.; Meng, W.-M.; Wang, R.-Y.; Chen, F.-L.; Li, T.; Wang, D.-D.; Wang, F.; Zhu, S.-E.; Wei, C.-X.; Lu, H.-D.; et al. Engineering highly graphitic carbon quantum dots by catalytic dehydrogenation and carbonization of Ti3C2Tx-MXene wrapped polystyrene spheres. Carbon 2022, 190, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Han, W.; Xie, M.; Yang, J.; Jing, L. Synthesis of SPR Au/BiVO4 quantum dot/rutile-TiO2 nanorod array composites as efficient visible-light photocatalysts to convert CO2 and mechanism insight. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yue, L.; Liu, T.; Lan, Q.; Cao, X.; Xing, B. Photocatalytic inactivation of harmful algae Microcystis aeruginosa and degradation of microcystin by g-C3N4/Cu-MOF nanocomposite under visible light. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 313, 123515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; Liang, X.; Dong, X.; Zhang, X. Supporting carbon quantum dots on NH2-MIL-125 for enhanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants under a broad spectrum irradiation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 467–468, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Deng, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J.; Sheng, H. Facilitated Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction in Aerobic Envi-ronment on a Copper-Porphyrin Metal–Organic Framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, X.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Shen, A.; Ye, M.; Wang, W. Copper porphyrin MOF/graphene oxide composite membrane with high efficiency electrocatalysis and structural stability for wastewater treatment. J. Membr. Science 2024, 695, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Peng, B.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Li, B.; Tian, J.; Liu, Z.; Tai, Y. Bifunctional coupled metal covalent organic framework MCOF-FeCu is used to implement bionic leaves. Fuel 2025, 400, 135787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liang, R.; Zhou, C.; Yan, G.; Wu, L. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs)/noble metal co-decorated MIL-53(Fe) as difunctional photocatalysts for the simultaneous removal of Cr(VI) and dyes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 255, 117725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lv, S.; Shen, Z.; Tian, P.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Novel ZnCdS Quantum Dots Engineering for Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 13805–13814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chang, H.; Zhong, J.; Lu, J.; Ma, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, Z.; Yin, G. Facile synthesis of ZnCdS quantum dots via a novel photoetching MOF strategy for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 330, 125258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liang, Y.; Yang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xu, S.; Han, C. Reinforced AgFeO2-Bi4TaO8Cl p-n heterojunction with facet-assisted photocarrier separation for boosting photocatalytic degradation of ofloxacin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 322, 124333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Lv, K. Enhanced Visible Photocatalytic Oxidation of NO by Repeated Calcination of g-C3N4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, M.J. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) synthesis and heterostructures, principles, mechanisms, and recent advances: A critical review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 32708–32728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaitha, P.M.; Shamsa, K.; Murugan, C.; Bhojanaa, K.B.; Ravichandran, S.; Jothivenkatachalam, K.; Pandikumar, A. Graphitic carbon nitride nanoplatelets incorporated titania based type-II heterostructure and its enhanced performance in photoelectrocatalytic water splitting. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanksha; Kundu, S.; Dhariwal, N.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, V.; Singh, A.K.; Thakur, S. Coordinated environmental and hydrogen energy resilience: A chronological insight into dual functional photocatalysts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 541, 216782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Lv, C.; Xiong, Y.; Li, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, F.; Yuan, H.; You, B.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Heterojunction configuration-specific photocatalytic degradation of methyl orange and methylene blue dyes using ZnO-based nanocomposites. J. Adv. Res. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Du, T.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Song, W.; Meng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, Z. Recent progress in zeolite-based photocatalysts: Strategies for improving photocatalytic performance. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1035, 181573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guselnikova, O.; Postnikov, P.; Pershina, A.; Svorcik, V.; Lyutakov, O. Express and portable label-free DNA detection and recognition with SERS platform based on functional Au grating. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 470, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-A.; Jou, S.; Mao, T.-Z.; Huang, B.-R.; Huang, Y.-T.; Yu, H.-C.; Hsieh, Y.-F.; Chen, C.-C. Silicon- and oxygen-codoped graphene from polycarbosilane and its application in graphene/n-type silicon photodetectors. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 464, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | wt% | |

|---|---|---|

| Cu | 9.8 | 0.5 |

| N | 5.0 | 0.5 |

| O | 43.1 | 0.5 |

| C | 42.1 | 0.5 |

| Sample | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Aperture (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-MOF | 112.257 | 0.4487 | 74.6 |

| 1 mL C3N4QDs/Cu-MOF | 230.059 | 0.3265 | 28.4 |

| 5 mL C3N4QDs/Cu-MOF | 273.335 | 0.3981 | 29.1 |

| 10 mL C3N4QDs/Cu-MOF | 111.225 | 0.3265 | 44.8 |

| Photocatalyst | Light Source | Pollutant | Degradation Efficiency | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CQDs/NH2-MIL-125 | 300 W Xenon lamp | RhB | 95% | [52] |

| g-C3N4/Cu-MOF | 300 W Xenon lamp | Microcystic toxins | 90% | [37] |

| CQDs/MIL-53(Fe) | 500 W Xenon lamp | RhB + Cr(VI) | 98% | [42] |

| g-C3N4/TiO2 | 350 W Xenon lamp | Methyl orange | 90% | [53] |

| g-C3N4 QDs/Cu-MOF | 300 W Xenon lamp | Congo Red | 96.6% | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wu, K. Boosting Photocatalysis: Cu-MOF Functionalized with g-C3N4 QDs for High-Efficiency Degradation of Congo Red. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121169

Wang Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, Shi Y, Liu Q, Wu K. Boosting Photocatalysis: Cu-MOF Functionalized with g-C3N4 QDs for High-Efficiency Degradation of Congo Red. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121169

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuhao, Yuan Yang, Xinyue Zhang, Yajie Shi, Qiang Liu, and Keliang Wu. 2025. "Boosting Photocatalysis: Cu-MOF Functionalized with g-C3N4 QDs for High-Efficiency Degradation of Congo Red" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121169

APA StyleWang, Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, X., Shi, Y., Liu, Q., & Wu, K. (2025). Boosting Photocatalysis: Cu-MOF Functionalized with g-C3N4 QDs for High-Efficiency Degradation of Congo Red. Catalysts, 15(12), 1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121169