Effect of Solar Irradiation on the Electrooxidation of a Dye Present in Aqueous Solution and in Real River Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

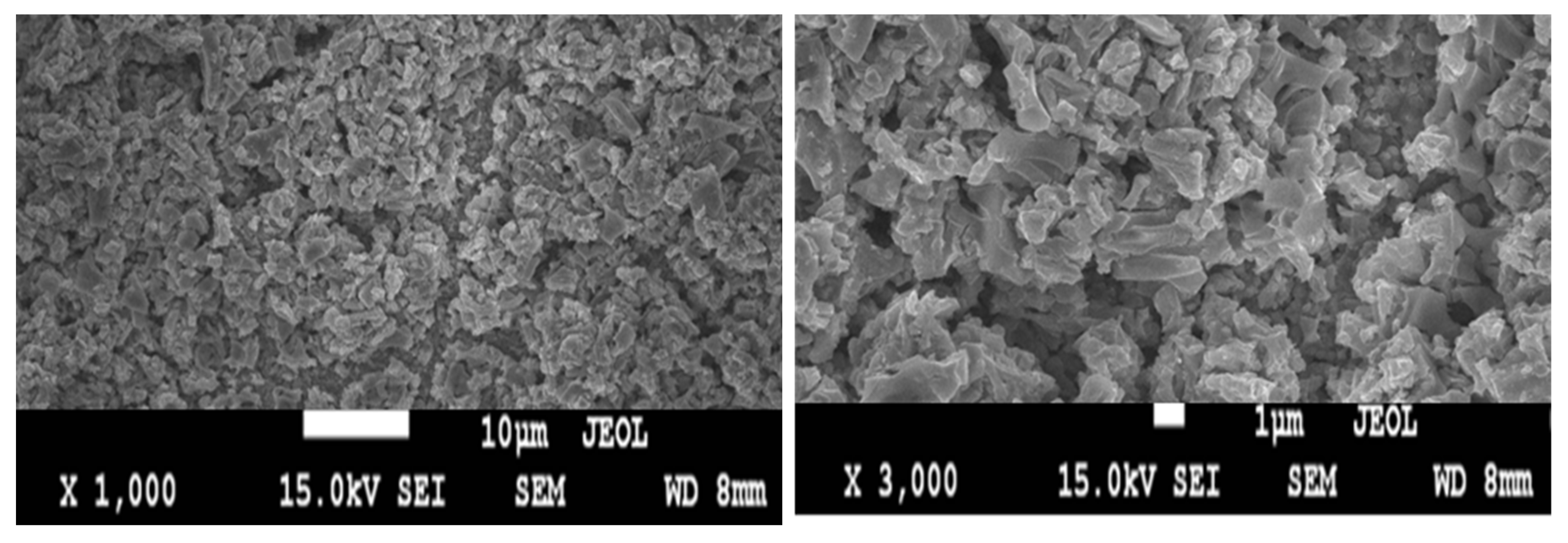

2.1. Anode Surface Characterization and Structural Analysis

2.2. Electrochemical Anode Characterization

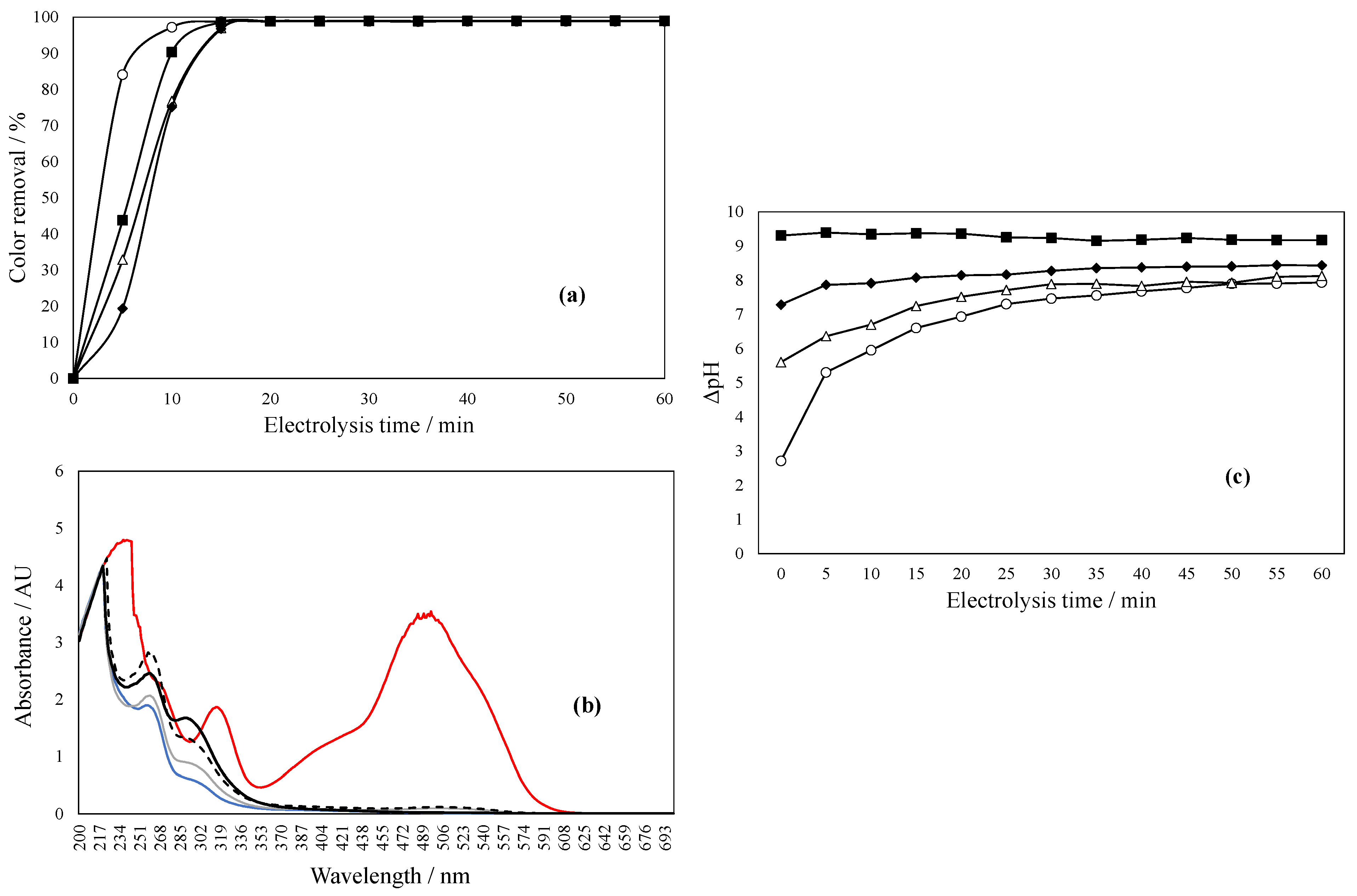

2.3. pH Effect During Dye Degradation

2.4. Current Density Effect During Dye Degradation

2.5. NaCl Concentration Effect During Dye Degradation

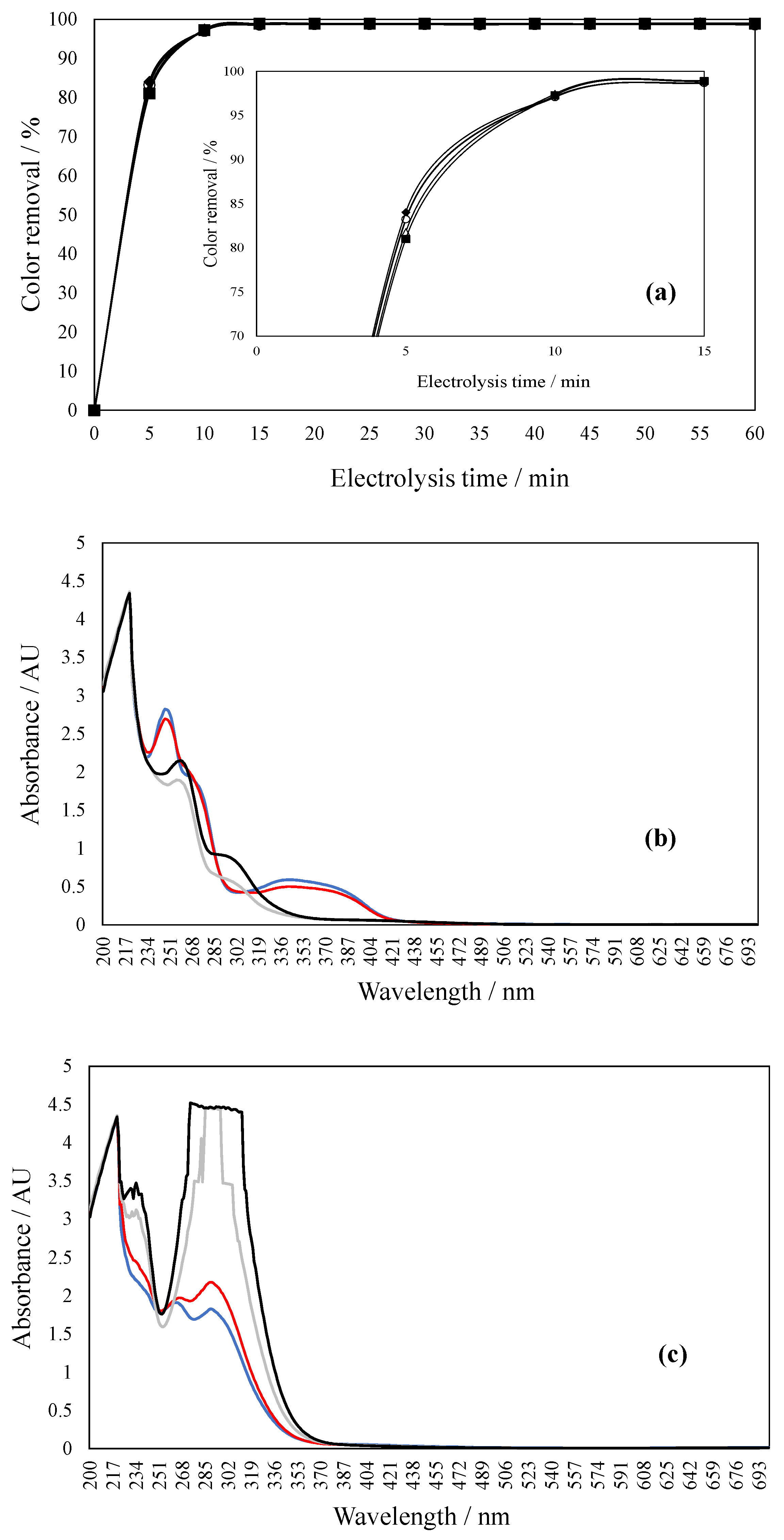

2.6. Optimal Conditions Under Ambient Temperature for Dye Degradation

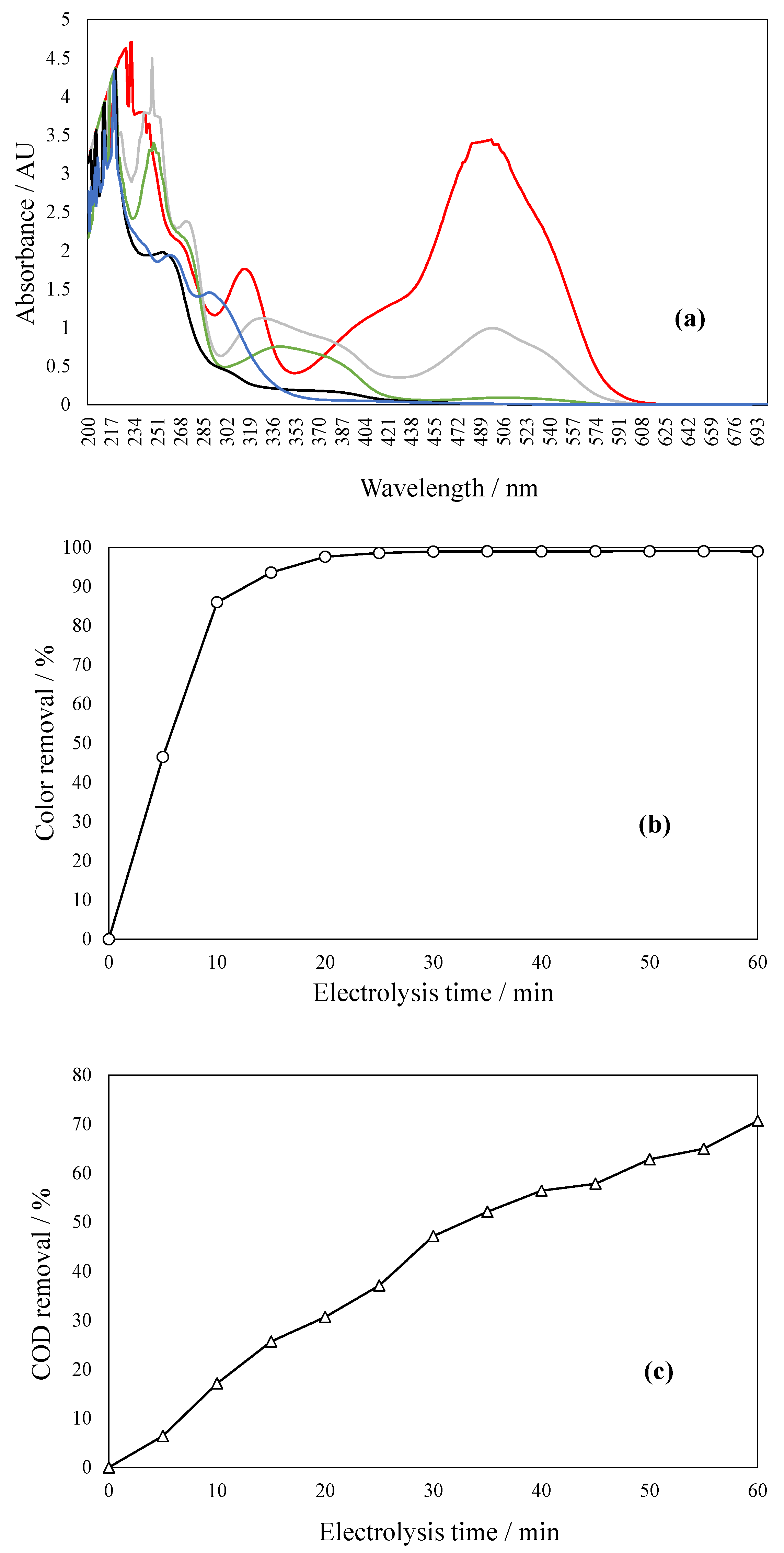

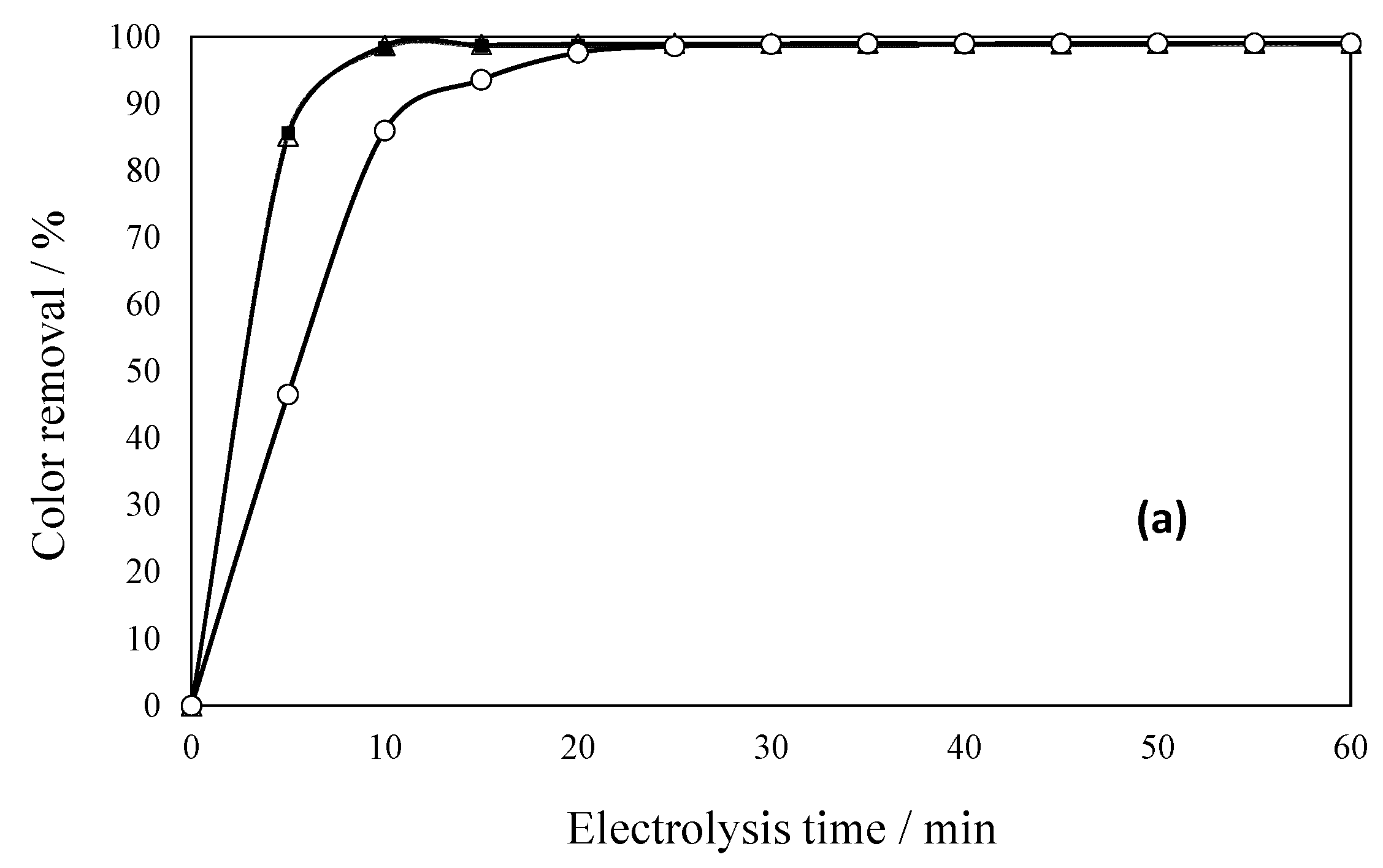

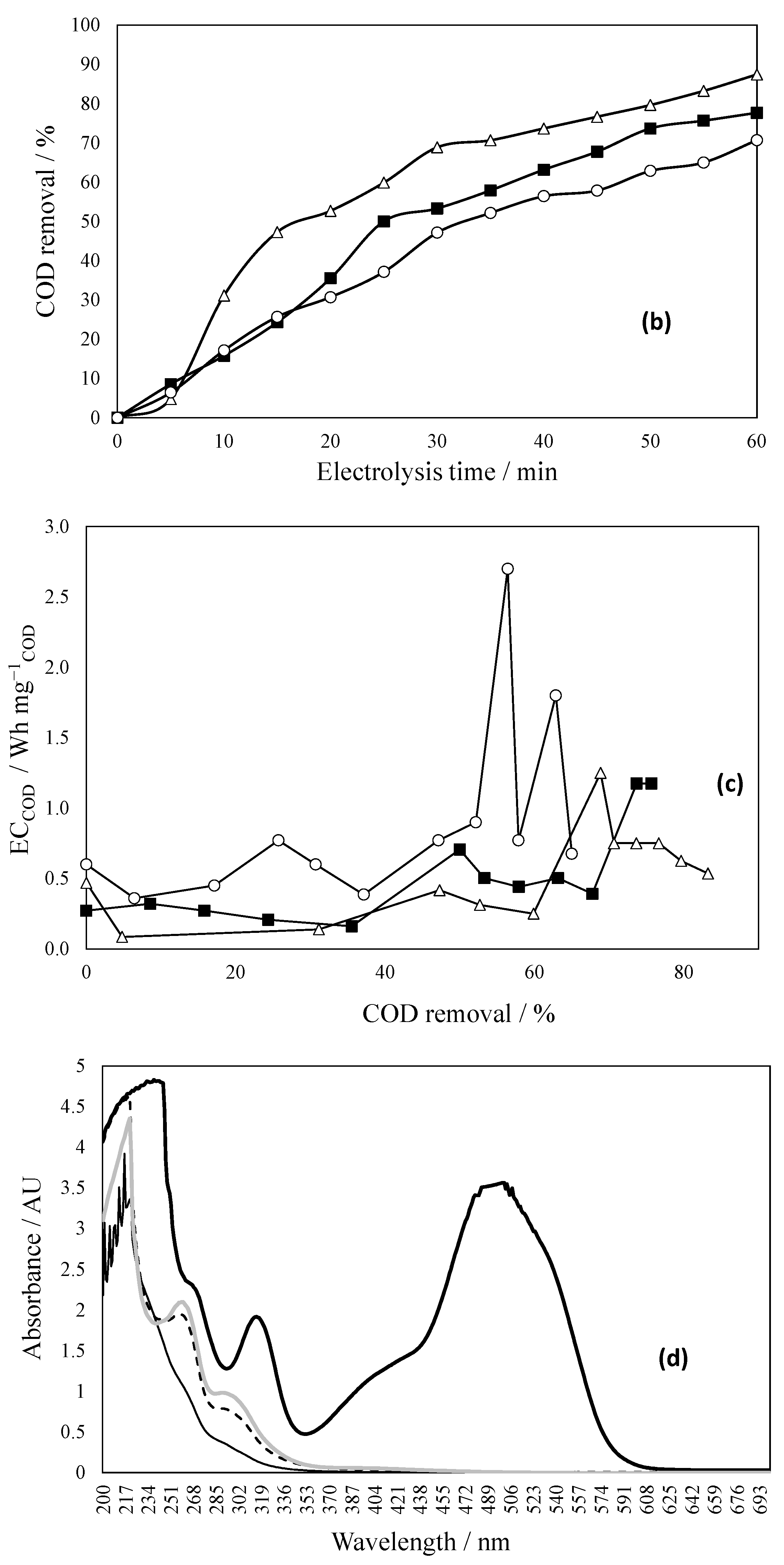

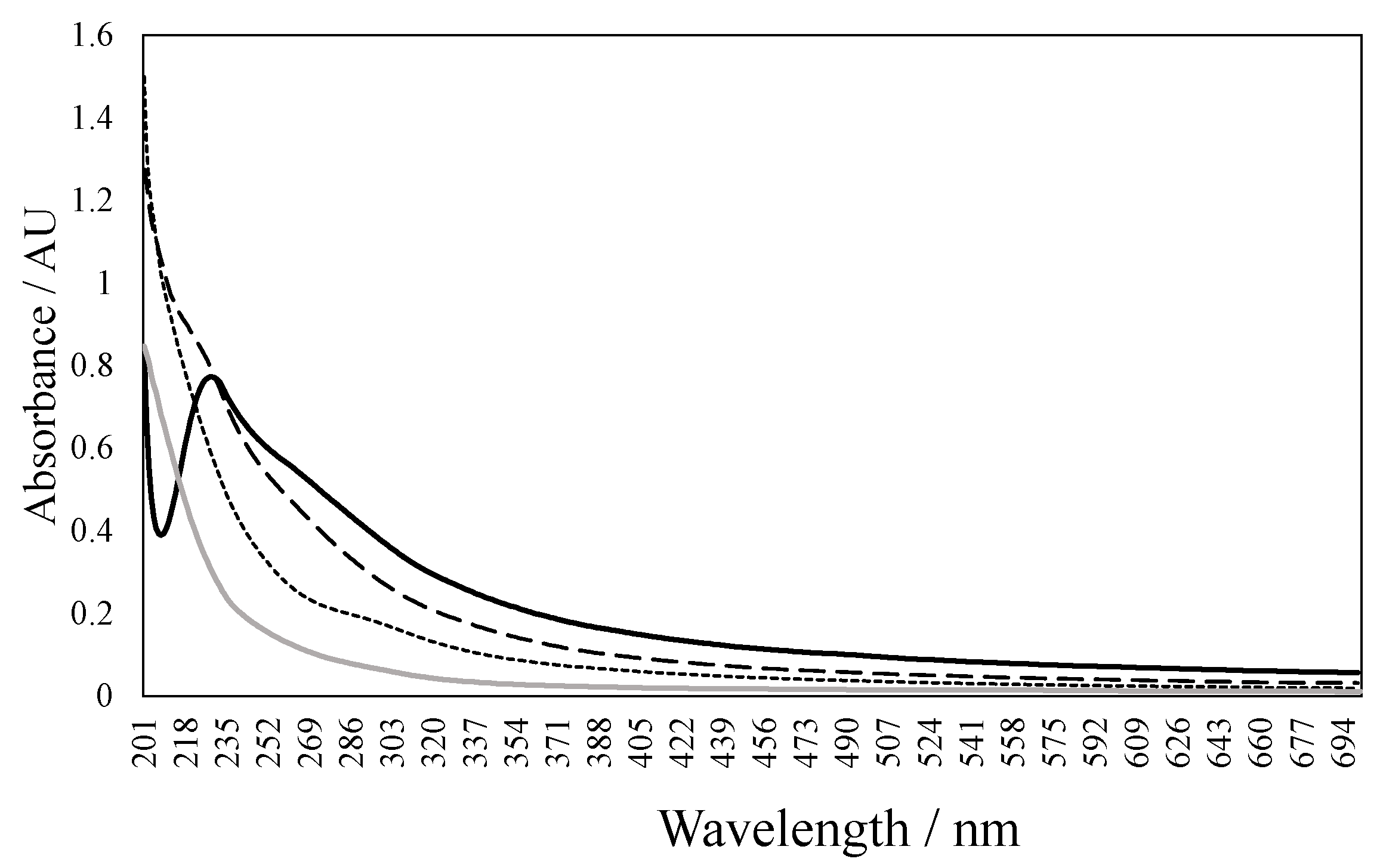

2.7. Effect of Solar Radiation on Dye Effluent Degradation

- (a)

- Thermal enhancement, whereby the gradual rise in solution temperature (from ambient to ~50 °C) improves molecular motion and diffusion rates. This reduces external mass-transfer limitations and facilitates more effective interaction between dye molecules and reactive sites at the electrode surface, enhancing COD removal from 71% to 77.6%.

- (b)

- Photo activation involves UV and near-UV solar radiation which stimulates direct photolysis of dye chromophores and promotes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), via photochemical reactions in water or through excitation of surface-bound species. Even in the absence of photocatalysts, dyes such as azo compounds may undergo bond cleavage upon UV exposure, particularly in the presence of auxiliary oxidants or chloride ions that yield secondary oxidants (e.g., Cl•, Cl2•−, HOCl). This results in a significantly improved degradation pathway, increasing COD removal to 87.4% and making the treated water visually transparent [36,37]. The combined effect of thermally enhanced diffusion and photo-induced oxidation mechanisms highlights the advantages of using natural solar energy for water treatment applications.

- (c)

- The architecture of the Ti|RuO2–ZrO2–Sb2O5 anode enables solar irradiation to promote the generation and extraction of useful carriers, thereby enhancing the formation of reactive oxidizing species and improving pollutant degradation efficiency. The inclusion of ZrO2 and Sb2O5 increases the dispersion of the active layer, decreases crystallite size, and improves coating morphology, resulting in a larger electroactive area [24]. Although RuO2 is not a classical semiconductor capable of generating electron–hole pairs from direct band-to-band excitation, under illumination it acts as an efficient conductive co-catalyst. RuO2 facilitates the extraction and transport of photogenerated carriers arising from interfacial or electrolyte-induced photo-processes, thus minimizing recombination and enhancing the overall electro-photocatalytic activity [38].

2.8. Evaluation of Electrooxidation Coupled to Solar Radiation on Real Wastewater Degradation

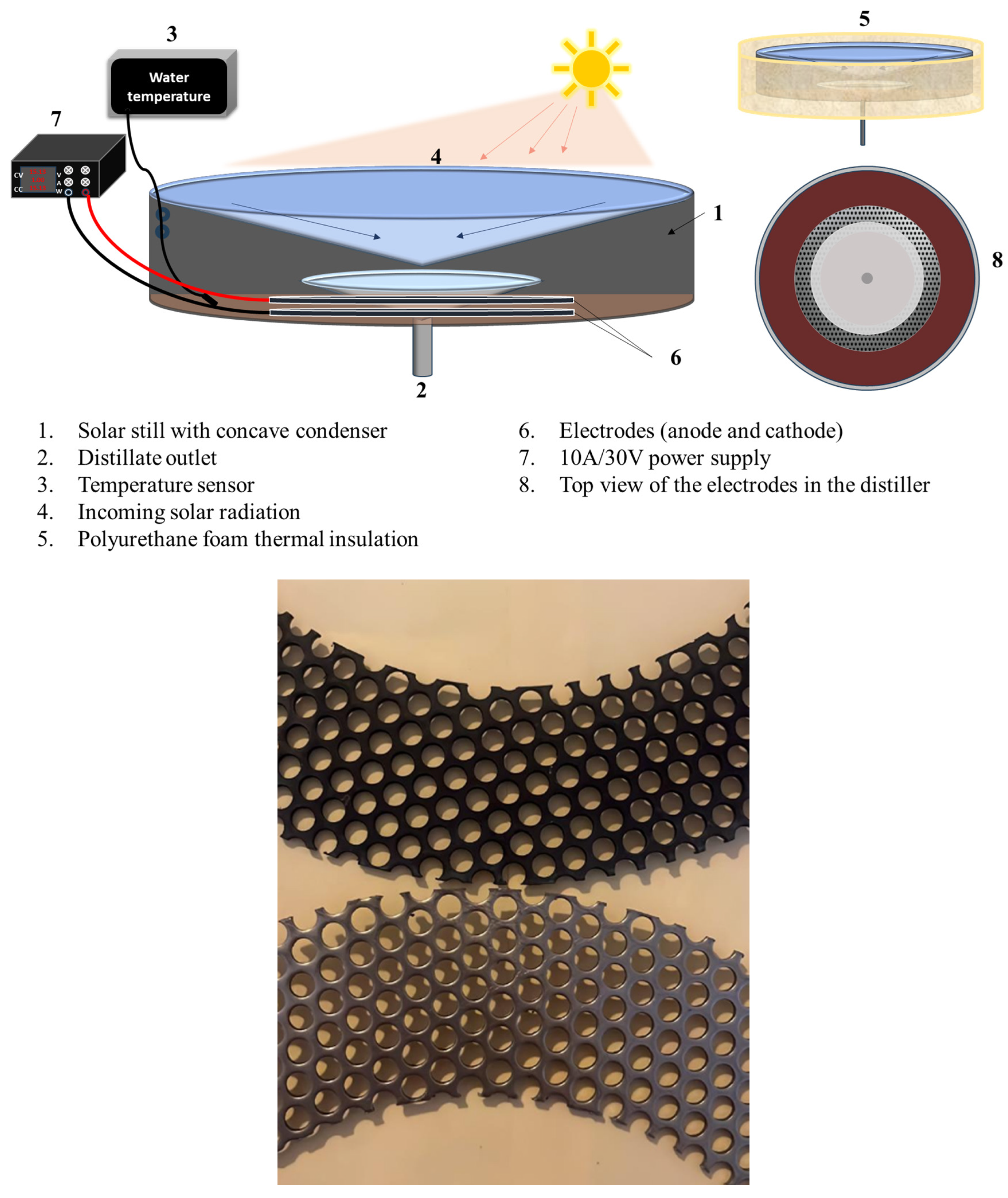

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Anode Preparation, Characterization and Morphological Studies

3.3. Experimental Setup

3.4. Dye Mineralization in the EO Process

3.5. Monitoring of Color Removal

3.6. Monitoring of Degradation by Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

3.7. Real Wastewater Treatment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Treviño-Reséndez, J.; Medel, A.; Cárdenas, J.; Meas, Y. Electrooxidation using SnO2–RuO2–IrO2|Ti and IrO2–Ta2O5|Ti anodes as tertiary treatment of oil refinery effluent. Appl. Res. 2024, 3, e202300038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Espinoza, J.D.; Mijaylova-Nacheva, P.; Avilés-Flores, M. Electrochemical carbamazepine degradation: Effect of the generated active chlorine, transformation pathways and toxicity. Chemosphere 2018, 192, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, W.; Feng, C.; Chen, N.; Chen, H.; Kuang, P.; Deng, Y.; Ma, L. Electrochemical oxidation of aniline using Ti/RuO2-SnO2 and Ti/RuO2-IrO2 as anode. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 128734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; García-García, V.; Expósito, E.; Aldaz, A.; Montiel, V. Electrochemical treatment of wastewater from almond industry using DSA-type anodes: Direct connection to a PV generator. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 123, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddouh, A.; El Ibrahimi, B.; Rguitti, M.M.; Mohamed, E.; Hussain, S.; Bazzi, L. Electrochemical removal of methylene bleu dye in aqueous solution using Ti/RuO2–IrO2 and SnO2 electrodes. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1852–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Jia, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Dong, F.; Zhou, S. Dimensionally stable Ti/SnO2-RuO2 composite electrode based highly efficient electrocatalytic degradation of industrial gallic acid effluent. Chemosphere 2019, 224, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Huang, X.; Ma, J.; Wu, F.; Zhou, T. Ti/Ruo2-Iro2-Sno2 anode for electrochemical degradation of pollutants in pharmaceutical wastewater: Optimization and degradation performances. Sustainability 2021, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouladvand, I.; Asl, S.K.; Hoseini, M.G.; Rezvani, M. Characterization and electrochemical behavior of Ti/TiO2–RuO2–IrO2–SnO2 anodes prepared by sol–gel process. J. Solgel Sci. Technol. 2019, 89, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.R.; Botta, C.M.R.; Espindola, E.L.G.; Olivi, P. Electrochemical treatment of tannery wastewater using DSA® electrodes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Goyes, R.E.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Ostos, C.; Torres-Palma, R.A.; González, I. The Effects of ZrO2 on the Electrocatalysis to Yield Active Chlorine Species on Sb2O5-Doped Ti/RuO2 Anodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, H818–H825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González–Fuentes, M.A.; Bruno–Mota, U.; Méndez–Albores, A.; Teutli–Leon, M.; Medel, A.; Agustín, R.; Feria, R.; Hernández, A.A.; Méndez, E. Synthesis and Characterization of Uncracked IrO2-SnO2-Sb2O3 Oxide Films Using Organic Precursors and Their Application for the Oxidation of Tartrazine and Dibenzothiophene. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2021, 16, 210327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchou, F.E.; Zazou, H.; Afanga, H.; El Gaayda, J.; Akbour, R.A.; Lesage, G.; Rivallin, M.; Cretin, M.; Hamdani, M. Electrochemical oxidation treatment of Direct Red 23 aqueous solutions: Influence of the operating conditions. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 1501–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisymeon, E.; Dimou, A.; Mantzavinos, D.; Katsaounis, A. Electrochemical oxidation of model compounds and olive mill wastewater over DSA electrodes: 1. The case of Ti/IrO2 anode. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 167, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, E.; Fernández-Zayas, J.L.; Porta-Gándara, M.A. Current Status of Theoretical and Practical Research of Seawater Single-Effect Passive Solar Distillation in Mexico. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, T.; Sathyamurthy, R.; Denkenberger, D.; Lee, S.J. Solar Distillation Meets the Real World: A Review of Solar Stills Purifying Real Wastewater and Seawater; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosillo-Villalobos, J.J. Destilación solar, ITESO, 16. Tlaquepaque, Jalisco, 1989. Available online: https://rei.iteso.mx/items/02bb8b46-4fb7-4c75-9517-b2209022815a (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Minmin, G.; Liangliang, Z.; Connor-Kangnuo, P.; Ghim-Wei, H. Solar Absorber Material and System Designs for Photothermal Water Vaporization towards Clean Water and Energy Production. Energy Env. Sci. 2019, 12, 841–864. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, C.H.Z.; Ramírez-Cerón, M.; Cancino-Rojas, X.; Barbosa, E.M.; Arredondo-Velázquez, M.; Hernández-López, J.M. Solar irradiance statistical analysis in Mexico City from 2018 to 2021. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.13934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NREL. NSRDB: National Solar Radiation Database. Available online: https://nsrdb.nrel.gov/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- El Messaoudi, N.; Miyah, Y.; Singh, N.; Gubernat, S.; Fatima, R.; Georgin, J.; El Mouden, A.; Saghir, S.; Knani, S.; Hwang, Y. A critical review of Allura Red removal from water: Advancements in adsorption and photocatalytic degradation technologies, and future perspectives. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyles, C.; Sobeck, S.J.S. Photostability of organic red food dyes. Food Chem. 2020, 315, 126249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.; Gosetti, F.; Marengo, E.; Llompart, M.; Garcia-Jares, C. Study of photostability of three synthetic dyes commonly used in mouthwashes. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Garcia, A.; Barrera-Diaz, C.E.; Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Ávila-Córdoba, L.I. Low-Cost Solar Still System with Concave Condensing Cover for the Distillation of Synthetic Water Polluted with Allura Red Dye. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Goyes, R.E.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Ostos, C.; Ferraro, F.; Torres-Palma, R.A.; Gonzalez, I. Microstructural and electrochemical analysis of Sb2O5 doped-Ti/RuO2-ZrO2 to yield active chlorine species for ciprofloxacin degradation. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 213, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sánchez, C.; Robles, I.; Godínez, L.A. Review of recent developments in electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: Application to remove dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 12611–12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilaji, S.; Narenkumar, J.; Das, B.; S, S.; Rajakrishnan, R.; Sathishkumar, K.; Rajamohan, R.; Rajasekar, A. Electrochemical oxidation of azo dyes degradation by RuO2–IrO2–TiO2 electrode with biodegradation Aeromonas hydrophila AR1 and its degradation pathway: An integrated approach. Chemosphere 2023, 345, 140516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro-Ayo, R.; Pérez, T.; Lanza, M.R.V.; Brillas, E.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Santos, A.J.D. New electrochemical reactor design for emergent pollutants removal by electrochemical oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 458, 142551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Production and contribution of hydroxyl radicals between the DSA anode and water interface. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 23, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, C.; Waite, T.D. Hydroxyl radicals in anodic oxidation systems: Generation, identification and quantification. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Panizza, M. Electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants for wastewater treatment. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2018, 11, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Direct and Mediated Anodic Oxidation of Organic Pollutants. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6541–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.N.; Yuen, M.L.; Ramli, R.A. Photocatalysis of dyes: Operational parameters, mechanisms, and degradation pathway. Green Anal. Chem. 2025, 12, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Hsu, Y.-H. Effects of Reaction Temperature on the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 with Pd and Cu Cocatalysts. Catalysts 2021, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, I.; Kanelli, M.; Ariese, F.; van Bommel, M.R. Parameters that affect the photodegradation of dyes and pigments in solution and on substrate—An overview. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 210, 110999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, Z.A.; Mecha, A.C.; Mwasiagi, J.I. Enhanced solar photodegradation of reactive blue dye using synthesized codoped ZnO and TiO2. Discov. Chem. 2025, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaaboul, F.; Canle, M.; Haoufazane, C.; Santaballa, J.A.; Hammouti, B.; Azzaoui, K.; Jodeh, S.; Hadjadj, A.; El Hourch, A. Sunlight-Driven Photodegradation of RB49 Dye Using TiO2-P25 and TiO2-UV100: Performance Comparison. Coatings 2024, 14, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, T.; Babot, O.; Thomas, L.; Olivier, C.; Redaelli, M.; D’aRienzo, M.; Morazzoni, F.; Jaegermann, W.; Rockstroh, N.; Junge, H.; et al. New Insights into the Photocatalytic Properties of RuO/TiO Mesoporous Heterostructures for Hydrogen Production and Organic Pollutant Photodecomposition. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 7006–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Díaz, J.P.; Ortega-Escobar, H.M.; Ramírez-Ayala, C.; Flores-Magdaleno, H.; Sánchez-Bernal, E.I.; Can-Chulim, Á.; Mancilla-Villa, O.R. Concentración de nitrato, fosfato, boro y cloruro en el agua del río Lerma. Ecosis. Recur. Agropec. 2019, 6, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Lu, J.; Hu, B.; Huang, Q. Formation of chlorate and perchlorate during electrochemical oxidation by Magnéli phase Ti4O7 anode: Inhibitory effects of coexisting constituents. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöllig, H.; Remmele, A.; Fritzsche, C.; Morgenroth, E.; Udert, K.M. Formation of Chlorination Byproducts and Their Emission Pathways in Chlorine Mediated Electro-Oxidation of Urine on Active and Nonactive Type Anodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11062–11069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Thao, T.T.; Kim, J.-H.; Hwang, I. Effects of the formation of reactive chlorine species on oxidation process using persulfate and nano zero-valent iron. Chemosphere 2020, 250, 126266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-H.; Kang, S.-F.; Wu, F.-A. Hydroxyl radical scavenging role of chloride and bicarbonate ions in the H2O2/UV process. Chemosphere 2001, 44, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NMX-AA-008-SCFI; Análisis de Agua.-Medición del pH en Aguas Naturales, Residuales y Residuales Tratadas.-Método de Prueba. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2016.

- NMX-AA-030/2-SCFI; Determinación de la Demanda Química de Oxígeno en Aguas Naturales, Residuales y Residuales Tratadas-Método de Prueba-Parte 2–Determinación del Índice de la Demanda Química de Oxígeno–método de Tubo Sellado a Pequeña Escala. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2011.

- NMX-AA-038-SCFI; Análisis de Agua–Determinación de Turbiedad en Aguas Naturales, Residuales y Residuales Tratadas–método de Prueba. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2001.

- NMX-AA-093-SCFI; Determinación de la conductividad electrolítica-método de prueba. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Ciudad de México, México, 2000.

| Sample | % COD Removal | pH | Color (Pt-Co Scale) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lerma River | - | 7.23 | 424 |

| LRP1 (pH 2–3, 0.05 NaCl, 5 mA cm−2) | 23% | 7.3 | 200 |

| LRP2 (pH 7–8, 5 mA cm−2) | 15% | 7.85 | 183 |

| LRP3 (pH 2–3, 5 mA cm−2) | 47% | 7.5 | 102 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos-García, A.; Barrera-Díaz, C.E.; Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Vazquez-Arenas, J.; Ávila-Córdoba, L.I. Effect of Solar Irradiation on the Electrooxidation of a Dye Present in Aqueous Solution and in Real River Water. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121171

Ramos-García A, Barrera-Díaz CE, Frontana-Uribe BA, Vazquez-Arenas J, Ávila-Córdoba LI. Effect of Solar Irradiation on the Electrooxidation of a Dye Present in Aqueous Solution and in Real River Water. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121171

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-García, Anabel, Carlos E. Barrera-Díaz, Bernardo A. Frontana-Uribe, Jorge Vazquez-Arenas, and Liliana I. Ávila-Córdoba. 2025. "Effect of Solar Irradiation on the Electrooxidation of a Dye Present in Aqueous Solution and in Real River Water" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121171

APA StyleRamos-García, A., Barrera-Díaz, C. E., Frontana-Uribe, B. A., Vazquez-Arenas, J., & Ávila-Córdoba, L. I. (2025). Effect of Solar Irradiation on the Electrooxidation of a Dye Present in Aqueous Solution and in Real River Water. Catalysts, 15(12), 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121171