Abstract

The photocatalytic reduction of CO2 in aqueous media offers a sustainable route for solar-to-fuel conversion, yet remains challenged by CO2’s thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness, low solubility, and competitive hydrogen evolution. Here, we investigate the interplay between ionic liquids (ILs), photocatalyst supports, and additive composition in directing product selectivity among CO, CH4, and H2. Using imidazolium acetate as a benchmark, we demonstrate that ILs not only pre-activate CO2 but can also undergo decomposition pathways under illumination, notably Kolbe-type reactions leading to methane formation from acetate rather than from CO2. Comparative studies of Pd-decorated TiO2 and g-C3N4 nanosheets reveal distinct behaviors driven by their interfacial interactions with the imidazolim-based ionic liquid: weak interaction with TiO2 strongly promotes hydrogen evolution, whereas strong coupling with g-C3N4 synergizes with C1C4ImOAc to trigger acetate-derived Kolbe reactivity. The systematic evaluation of alternative salts confirms the determinant role of anion basicity and medium-pH-basic anions facilitate CO2 activation, whereas weakly basic or non-coordinating anions favor water splitting. Overall, these results clarify the dual role of ionic liquids as both CO2 activators and sacrificial agents, and highlight design principles for improving product selectivity and efficiency in aqueous CO2 photoreduction systems.

1. Introduction

The ever-increasing levels of atmospheric CO2 and the global demand for sustainable energy solutions have driven intense research into the direct conversion of CO2 into value-added fuels using solar energy [1]. Among the available strategies—photovoltaic systems, photoelectrochemical cells, and photocatalysis—the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 stands out as most promising, as it does not rely on carbon-based external energy sources [2,3,4,5]. However, its efficiency remains limited due to three fundamental challenges: the thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness of CO2, and its low solubility in reaction (aqueous) media. The first one-electron reduction of CO2 to CO2•− is both sluggish and energetically demanding (E° = −1.90 V vs. NHE at pH 7), often giving way to the competitive hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

To overcome these limitations, imidazolium-based ionic liquids (Im-ILs) have emerged as multifunctional media that promote CO2 activation and selectivity [6,7]. Their ability to absorb CO2, lower reduction overpotentials, suppress HER, and stabilize reactive intermediates makes them highly valuable for photocatalysis [8,9]. Notably, certain basic anions in Im-ILs can facilitate carbene formation via deprotonation at the C2 position, enabling the generation of CO2-activating zwitterionic species [10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

Our previous work has shown that among various Im-ILs, only C1C4ImOAc is capable of pre-activating CO2 in bare or diluted media and under ambient pressure, a prerequisite for selective CO formation under our reaction conditions. Moreover, bare Im-ILs enhance charge separation in photocatalysts by inhibiting electron–hole recombination, thereby prolonging the lifetime of photoinduced carriers. Im-ILs can even function as organocatalysts and photosensitizers, contributing to electron transfer directly, as evidenced by correlations between CO production and both UV–vis absorption properties and Kamlet–Taft β parameters [14]. In highly diluted systems (xH2O > 0.99), the ionic nature of the Im-ILs evolves from contact ion pairs (CIP) to solvent-separated ion pairs (SIP) [17,18,19], modifying their reactivity from CO2 activation to a solvent one [14]. These solvent–anion interactions—quantified by Kamlet–Taft β values—are crucial for modulating H+ availability, thereby influencing CO2 reduction pathways, particularly via hydrogen carbonate intermediates.

In this context, we report herein the role of Im-ILs in diluted aqueous media and assess their effect in the presence of heterogeneous photocatalysts, which, to our knowledge, has never been reported. Specifically, we explore the photocatalytic CO2 reduction using nanosheet (NS) architectures, such as NS-TiO2/Pd and NS-g-C3N4/Pd, selected for their high surface area, exposed active sites, short charge migration distances [13,20,21,22], and possible surface doping [23]. By maintaining constant morphology and cocatalyst (Pd), we focus solely on the influence of the support material and the Im-IL environment.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Photocatalyst Supports

2.1.1. NS-TiO2 and NS-TiO2/Pd

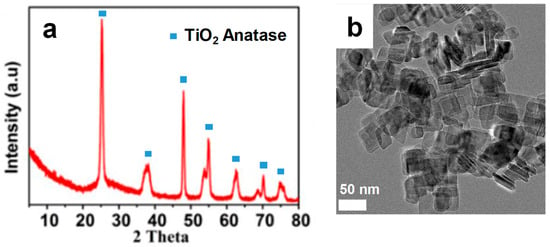

Rectangular TiO2 nanosheets (NS-TiO2) were synthesized via a hydrothermal route using hydrofluoric acid, following procedures reported in the literature [22]. The obtained material exhibited high crystallinity as anatase, as confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Figure 1a), with diffraction peaks corresponding to the anatase phase (JCPDS 21-1272). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the rectangular nanoplatelet morphology (Figure 1b), and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area was measured at 91 m2·g−1, significantly larger than that of commercial P25, indicating the formation of high-surface-area anatase nanosheets.

Figure 1.

XRD (a) and TEM image (b) of NS-TiO2.

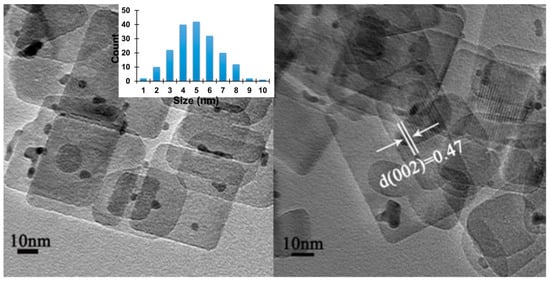

In situ deposition of palladium nanoparticles was then carried out on NS-TiO2 in aqueous medium. While the low Pd loading (~1 wt%) precluded the observation of Pd reflections in the XRD pattern (Figure S1), HRTEM imaging demonstrated uniform dispersion of Pd nanoparticles across the nanosheet surfaces (Figure 2). The mean particle size was in the 4–5 nm range (Figure 2), and the lattice spacing of 0.47 nm, observed along the top and bottom facets, was consistent with the (002) planes of anatase TiO2. These results confirm the successful preparation of Pd-decorated TiO2 nanosheets (NS-TiO2/Pd), combining high surface area with well-dispersed metallic cocatalyst nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

HRTEM images of in situ loading of Pd onto NS-TiO2 in H2O.

2.1.2. NS-g-C3N4 and NS-g-C3N4/Pd

Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4), an n-type polymeric semiconductor with appealing optical and structural properties [24,25,26], was prepared in nanosheet form (NS-g-C3N4) using melamine as a precursor and ammonium chloride as a bubble-forming agent, as reported in our previous work [15]. The high-temperature condensation of melamine yielded exfoliated nanosheets with a porous structure, as confirmed by TEM (Figure S2b). XRD analysis revealed the characteristic reflections at 13.1° and 27.4°, corresponding, respectively, to the in-plane (100) structure and the interlayer (002) stacking (JCPDS 87-1526) (Figure S2a). The weakening of the (100) peak indicated a partial disruption of interlayer interactions, consistent with the exfoliated morphology observed by microscopy.

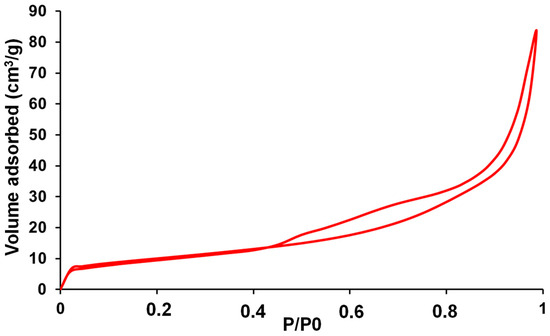

The synthesis yielded NS-g-C3N4 as a yellow powder with 13.2% efficiency, and the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area was measured at 36 m2·g−1. The adsorption isotherm displays a Type IV(a) profile, according to the IUPAC classification, which is characteristic of mesoporous materials (Figure 3). At intermediate pressures (approximately 0.4 < P/P0 < 0.8), a noticeable hysteresis loop appears between the adsorption and desorption branches, suggesting that the material possesses mesopores with a slit-like or cylindrical geometry, depending on the specific shape of the loop (commonly H3 or H4 types). At high relative pressures (P/P0 > 0.8), the sharp increase in the adsorbed volume reflects the filling of larger mesopores and interparticle voids. Overall, the isotherm confirms that the sample exhibits a mesoporous structure with a significant surface area and well-developed pore network, consistent with materials such as graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4).

Figure 3.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherm of NS-g-C3N4.

The deposition of Pd nanoparticles onto the g-C3N4 nanosheets was achieved in situ (NS-g-C3N4/Pd). XRD patterns of the composite showed only the characteristic g-C3N4 reflections, with no distinct Pd peaks, reflecting the low Pd content (Figure S3a). However, STEM and TEM images combined with EDX mapping confirmed the presence of Pd nanoparticles homogeneously dispersed on the nanosheets (Figure S3b–d). The Pd particle size distribution was narrow, with an average diameter of ~2 nm. Elemental analysis indicated a Pd content of 2.74 wt%, in agreement with the target loading. These features underline the successful preparation of NS-g-C3N4/Pd, where the two-dimensional semiconductor sheets served as a high-surface-area support for finely dispersed Pd nanoparticles.

2.2. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2

The dataset presented in Table 1 provides valuable insights into product selectivity during photocatalytic experiments in the presence of both photocatalysts (NS-g-C3N4/Pd & NS-TiO2/Pd) and C1C4ImOAc or salts diluted in H2O.

Table 1.

Photocatalytic data in the presence of ionic liquid or salts diluted in H2O *.

Three major trends can be extracted.

- The central role of imidazolium acetate (C1C4ImOAc): In the absence of a heterogeneous photocatalyst, C1C4ImOAc alone produces CO selectively (0.44 μmol·h−1), consistent with its demonstrated ability to act as a homogeneous photocatalyst [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. This confirms that the imidazolium cation functions as a photosensitizer while the acetate anion activates the solvent, leading to alkylcarbonate or bicarbonate intermediates [14]. When combined with NS-g-C3N4/Pd, the selectivity shifts from CO toward CH4 (0.38 μmol·h−1), underlining that the coexistence of heterogeneous and homogeneous pathways can alter the reduction mechanism (entry 2). In this hybrid system, the pre-activated C1C4Im–CO2 species may be reduced further than CO, thereby promoting C–H bond formation. The results obtained under argon confirm that the two phenomena take part in CH4 production, since its production decreases drastically but does not become zero (entry 3). Furthermore, it appears that the protic character of the cation or the presence of a proton due to acid conditions strongly enhances CH4 production (entries 4–5).

- The decisive influence of photocatalyst composition: A striking contrast emerges between NS-g-C3N4/Pd and NS-TiO2/Pd. The former, when combined with C1C4ImOAc, supports CO2 reduction but with altered selectivity (favoring CH4 over CO) (entry 2). The latter, however, overwhelmingly drives hydrogen evolution (entries 6 and 7), with H2 yields exceeding several thousand μmol·gPd−1·h−1 in the presence of salts such as CholineNTf2 or LiNTf2 (entries 14–15). This divergence illustrates that TiO2 strongly promotes proton reduction, while g-C3N4, in synergy with IL-mediated pre-activation, can direct electrons toward C–C bond chemistry and deeper CO2 reduction pathways. Surprisingly, under argon and in the presence of C1C4ImOAc, NS-TiO2/Pd affords higher amounts of CO, CH4, and H2, while H2 remains the dominant product (entry 8). No CO, CH4, and H2 are produced in the absence of palladium (Table S1, entries S5–S7).

- The impact of pH and additive nature: The correlation between solution pH, anion basicity, and selectivity is particularly revealing. At neutral to slightly acidic pH (≈5–6), imidazolium acetate affords CO or CH4, whereas alkaline conditions (>8) are detrimental: both KHCO3 and Na2CO3 completely suppress CO2 reduction and H2 production (entries 11 and 12), in line with the accumulation of inactive carbonate species. Salts such as NaOAc, operating around pH 8.1, bias the reaction toward methane (1.89 μmol·h−1) but with substantial co-production of H2 (entry 9), suggesting that basic acetate stabilizes pathways leading to C–H bond formation but destabilizes selective CO formation. Non-coordinating or weakly basic anions (NTf2− in CholineNTf2 or LiNTf2) promote massive hydrogen evolution, confirming that only sufficiently basic anions can activate CO2. These observations are in full agreement with the mechanistic picture outlined in [14], where the Kamlet–Taft β parameter (anion basicity) was shown to positively correlate with CO2 reduction efficiency. No CO, CH4, and H2 are produced in the absence of a photocatalyst (Table S1, entries S1–S4).

3. Discussion

Both supports—NS-TiO2 and NS-g-C3N4—were successfully synthesized with controlled morphology and surface properties. NS-TiO2 exhibits high crystallinity, large specific surface area, and well-defined anatase nanoplatelets, while NS-g-C3N4 displays a porous, exfoliated layered structure with weakened interlayer interactions. The deposition of Pd nanoparticles was effective in both systems, yielding nanoscale particles uniformly distributed on the support surfaces. However, the Pd content and average particle size differed: ~1 wt% Pd with slightly larger nanoparticles (4–5 nm) on NS-TiO2 versus 2.74 wt% Pd with narrowly distributed 2 nm nanoparticles on NS-g-C3N4. These structural differences are expected to significantly influence photocatalytic performance, with NS-TiO2/Pd favoring H2 evolution due to its strong affinity for proton reduction, and NS-g-C3N4/Pd promoting selective CO2 activation pathways in synergy with ionic liquids.

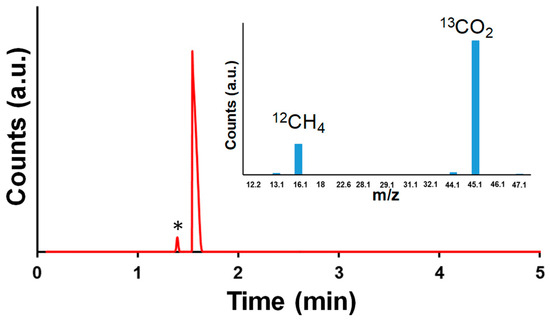

The photocatalytic behavior of diluted imidazolium-based ionic liquids (ILs) in aqueous solution was first evaluated in the absence of heterogeneous catalysts. In line with previous findings, selective CO production was observed with C1C4ImOAc (0.44 μmol·h−1), significantly higher than with other imidazolium salts such as C1C4ImO2CF3, C1C4ImBF4, or C1C4ImCl. This trend directly correlates with the Kamlet–Taft β parameter of the anion: the acetate anion, with its high hydrogen-bond basicity, strongly interacts with water molecules and facilitates CO2 activation, leading to the highest CO yields. Such results are consistent with the conclusions that both anion basicity and solution pH are critical determinants of CO2 reduction efficiency. When Pd-loaded nanosheet photocatalysts were introduced, the product distribution shifted significantly. With NS-g-C3N4/Pd in the presence of C1C4ImOAc, methane was selectively generated instead of CO. However, isotope-labeling experiments with 13CO2 revealed that the detected CH4 did not originate from CO2 reduction but possibly from the photodecomposition of acetate species (Figure 4). This conclusion is supported by the absence of the m/z = 17 ion peak corresponding to 13CH4 in the GC–MS spectrum, confirming that no methane derived from labeled 13CO2 was formed under these conditions. Control reactions under argon confirmed the same outcome, indicating that acetic acid (formed from OAc-based imidazolium) was the main source of CH4. The mechanism can be rationalized by the Kolbe-type decarboxylation reaction: oxidation of acetate anions (h+ + CH3COO− → CH3• + CO2), followed by reduction of methyl radicals (CH3• + H+ + e− → CH4) [27,28]. This pathway highlights the key role of acetate photodecomposition in methane production, rather than direct CO2 photoreduction [29,30].

Figure 4.

GC-MS data of reaction between C1C4ImOAc (in diluted aqueous solution) and NS-g-C3N4/Pd under 13CO2 atmosphere and UV–visible irradiation (* arises from residual air present in the set-up).

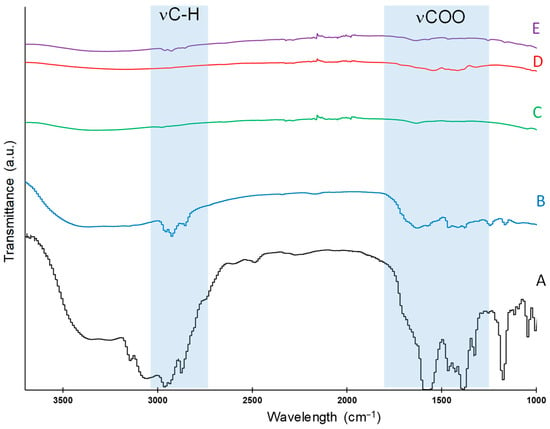

In contrast, NS-TiO2/Pd exhibited dual reactivity: both CO2 reduction and H2O splitting occurred concomitantly. With C1C4ImOAc, CH4 was again observed alongside CO and H2, under both CO2 and argon atmospheres. Under a CO2 atmosphere and in the presence of NaOAc, CO production becomes zero (entry 9), showing that the imidazolium cation in the ionic liquid plays a crucial role in CO2 photoreduction, and that methane production does indeed stem from the presence of acetate ligands. This is confirmed by the use of the trifluoroacetate anion CF3COO−, which also stops methane production under the same conditions, yielding only H2 (entry 10). DRIFT spectroscopy of NS-TiO2/Pd powders before (Figure 5C) and after reaction with diluted aqueous solution of C1C4ImOAc (Figure 5A,B) confirmed the strong surface coordination of acetate anions, as evidenced by characteristic stretching vibration ν(COO) between 1400 and 1700 cm−1, supporting their direct participation in photocatalytic processes. The DRIFT spectrum of NS-TiO2/Pd powder in the presence of the dilute C1C4ImOAc solution also shows ν(C-H) stretching vibration bands around 3000 cm−1, characteristic of the imidazolium cation, which therefore might also interact with the photocatalyst surface. To confirm the chemisorption of the imidazolium cation, these bands are totally absent in the presence of acetic acid (Figure 5D) but are weakly present using C1C4ImCl (Figure 5E), demonstrating that imidazolium can interact with the photocatalytic support but only in synergy with the anion. It has already been shown that an Im-IL coating of TiO2/Metal nanoparticles can drastically increase hydrogen production because of band gap change, enhancement of charge transfer between the photocatalyst and the electrolyte, and prevention of the recombination of photogenerated electron–hole pairs [8,31,32]. Although in our case, the quantities of ionic liquid used are not sufficient to achieve a uniform coating of the photocatalyst surface, the performances in H2 production are exceptional (between 3000 and 3500 μmol-gPd−1-h−1) compared with literature values (around 100 and 500 μmol-gPd−1-h−1 for TiO2/Pt [32] and TiO2/Au [31] nanomaterials, respectively).

Figure 5.

DRIFT spectra (A) of C1C4ImOAc, (B) of NS-TiO2/Pd after reaction with diluted aqueous solution of C1C4ImOAc, (C) of NS-TiO2/Pd, (D) of NS-TiO2/Pd after reaction with diluted aqueous solution of HOAc, and (E) of NS-TiO2/Pd after reaction with diluted aqueous solution of C1C4ImCl.

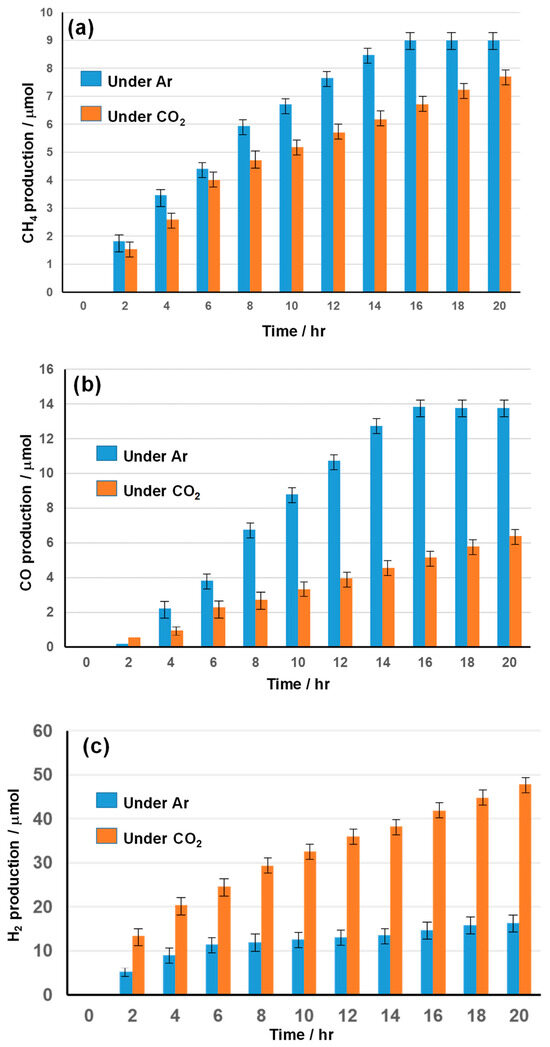

Kinetic monitoring over 20 h of NS-TiO2/Pd in diluted C1C4ImOAc showed that CH4 and CO formation were favored under argon (Figure A1a,b), while H2 evolution dominated under CO2 (Figure A1c), suggesting that the photo-Kolbe reaction (that produces CH4 and CO2) and CO2 photoreduction (that produces CO) pathways compete under these conditions.

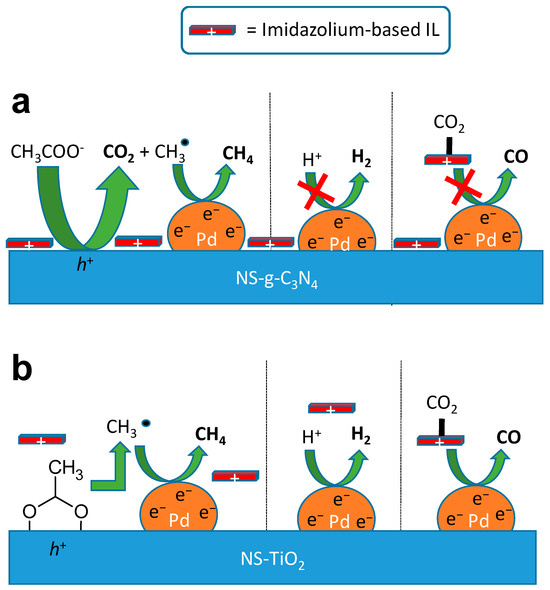

The nature of the support was then found to play a decisive role in governing reactivity. For NS-g-C3N4, strong π–π interactions between the nanosheet and the imidazolium cation generate a hydrophobic, positively charged surface layer that suppresses proton reduction (HER) while enhancing CO2 solubility and acetate adsorption. The latter can undergo oxidation to yield CO2 and CH3• radicals, which are subsequently reduced to CH4—thus diverting the pathway away from CO2 reduction (entry 2). The positive surface potential further repels protons, inhibiting H2 evolution. Moreover, as the small fraction of Im-ILs remains confined near the surface, their limited availability likely prevents effective CO2 pre-activation, thereby hindering CO formation (Figure 6a). In contrast, TiO2 exhibits weaker interaction with the imidazolium cation but a stronger affinity for the acetate anion through acetic acid coordination. This promotes CH4 formation via the photo-Kolbe reaction. Because the TiO2 surface is not positively charged, proton reduction becomes feasible, while the presence of imidazolium/carbon species in solution enables parallel CO2 photoreduction. Consequently, Kolbe decomposition of acetate, direct CO2 activation, and HER can occur simultaneously—accounting for the coexistence of CH4, CO, and H2 in the product mixture. Additional experiments with alternative anions further confirmed their decisive influence on photocatalytic behavior. Carbonate and bicarbonate salts (KHCO3, Na2CO3) completely suppressed activity, consistent with the known inhibitory effect of alkaline conditions on CO2 reduction. In contrast, the use of trifluoroacetate anion selectively inhibited CO and CH4 formation, emphasizing the essential role of the protic cationic component in driving H2 evolution (Figure 6b). Choline-based salts markedly enhanced hydrogen production, particularly in the presence of the NTf2− anion (entries 13 and 14), demonstrating that low-basicity anions favor water reduction pathways over CO2 activation. Remarkably, for TiO2 combined with NTf2− salts, an exceptionally high yield of H2 was observed, suggesting a specific surface interaction between TiO2, Pd, and NTf2−. This strong synergetic effect points to a distinct interfacial mechanism that warrants further investigation to unravel its exact contribution to hydrogen generation.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the proposed mechanisms, highlighting the interplay between the imidazolium-based ionic liquid and the surface of the 2D photocatalysts (a) NS-g-C3N4/Pd and (b) NS-TiO2/Pd and its impact on CO2 photoreduction.

In conclusion, the overall photocatalytic behavior arises from a decisive interplay between the nature of the support, the ionic liquid composition, and their interfacial interactions. The electronic structure and surface charge of the support dictate charge-transfer dynamics and product selectivity, while the choice of anion and cation modulates proton availability and reaction pathways. Specifically, π–π interactions on NS-g-C3N4/Pd favor CH4 formation and suppress HER, whereas TiO2 surfaces enable concurrent CO2 reduction, acetate oxidation, and H2 evolution. Moreover, anion basicity governs the competition between water reduction and CO2 activation, with NTf2− salts promoting exceptional H2 production through synergistic TiO2–Pd–anion coupling.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The ionic liquids 1-butyl-3-methyl-imidazolium acetate (C1C4ImOAc, 95%), 1-butyl-3-methyl-imidazolium trifluroacetate (C1C4ImCF3CO2, 95%), and Choline bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (CholineNTf2, 99%) were supplied by Iolitec Company (Heilbronn, Baden-Württemberg, Germany), dried overnight under high vacuum (10−5 M bar) at room temperature, and then stored in an Ar-filled MBRAUN glovebox (the concentration of both H2O and O2 lower than 0.5 ppm) (MBRAUN France, Merignac, France). The potassium hydrogen carbonate (KHCO3, 98%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 99.5%), ethylene glycol (EG, 75%), sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 99.6%), melamine (99%), Ti(OBu)4 (TBOT, 97%), hydrofluoric acid in water solution (HF, 40%), acetic acid (CH3COOH, 99.7%), Choline Chloride (CholineCl, 99%), Bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide lithium salt (LiNTf2, 99.99%), and palladium chloride (PdCl2, 99%) were purchased from Merck–Sigma Aldrich (Saint Louis and Burlington, MA, USA). CO2 (99.995%) gas was supplied from Air Liquid (Paris, France). All of them were used without further purification.

Nanosheet 2D-TiO2: The rectangular TiO2 nanosheets were synthesized by a hydrothermal route in the presence of hydrofluoric acid solution [22]. Hydrofluoric acid solution (3 mL of 40 wt% in H2O, 0.07 mol HF) was dropped into Ti(OBu)4 (TBOT) (25 mL, 0.073 mol) under stirring for 2 h until the mixture became a gel. Afterwards, the gel was transferred into a dried Teflon autoclave with a capacity of 50 mL and kept at 180 °C for 36 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the powder was separated by high-speed centrifugation, then washed with ethanol and distilled water (15 mL) several times and dried in the oven at 50 °C for 10 h. Afterwards, the powder was dispersed in aqueous NaOH solution (0.1 M) and further stirred for 8 h at room temperature. After being recovered by high-speed centrifugation, the solid was washed with distilled water and ethanol several times (15 mL), and then dried at 80 °C for 6 h. In the end, 3.4 g of white powder (yield = 59%) were isolated and noted as NS-TiO2.

Nanosheet 2D-TiO2/Pd: The Pd-NPs loading of NS-TiO2 (40 mg, 0.5 mol) was dispersed in ethylene glycol (EG) (20 mL) under ultrasonic, and a solution of PdCl2 (0.04 mL, 0.09 M) was added dropwise. Then, a solution of NaOH/EG (0.5 M) was rapidly added to adjust the pH of the mixed solution to around 10–10.5, followed by the slow addition of an aqueous solution of NaBH4 (25 mL, 2.0 mg·mL−1). The total mixture was kept under stirring at room temperature for 8 h. Finally, the NS-TiO2/Pd nanosheets were centrifuged and washed repeatedly with ethanol and ultra-pure water (15 mL). The resulting product was dried at 60 °C for 10 h. The theoretical loading of Pd onto NS-TiO2 is around 1 wt%. The product was denoted as NS-TiO2/Pd.

The preparation of the nanosheets NS-g-C3N4 and NS-g-C3N4/Pd by in situ loading of Pd onto g-C3N4 synthesized in H2O was previously reported [15]. The elemental analysis of this sample yielded a Pd mass concentration of 2.74%, with an average size of the Pd nanoparticles around 2 nm.

4.2. Characterizations

Solution NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE III 300 MHz with BBFO probe (Z gradient) using Topspin software 4.5.0 (Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany). The 1H and 13C NMR data were collected at room temperature on a Bruker AC 300 MHz spectrometer with the resonance frequency at 300.13 MHz for the 1H nucleus and 75.47 MHz for the 13C nucleus. The spectra were obtained at 298 K unless otherwise specified. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) referenced to CD2Cl2 or (CD2)3SO as external reference capillary. (CD2Cl2, δ 5.32 ppm for 1H, 53.84 for 13C; (CD2)3SO, δ 2.5 ppm for 1H, 39.52 for 13C).

Solid-state NMR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Avance III spectrometer, equipped with an 11.74 T wide-bore magnet operating at Larmor frequencies of 500.13 MHz for 1H and 125.72 MHz for 13C. The polypropylene Z-1500 sample was packed into a 4 mm ZrO2 rotor and rotated at magic angle spinning (MAS) rates of 12 KHz, using a conventional 4 mm HX probe. The PP Z-1500 sample was ground into smaller pieces in order to achieve stable spinning of the NMR rotor. For CP MAS spectrum, transverse magnetization was obtained from 1H using contact pulse duration of 2 ms, recycle delay of 5 s, and 2028 scans. SPINAL 64 1H decoupling was applied during acquisition. The DD MAS experiment was recorded with a recycle delay of 5 s and 3072 scans. The chemical shifts were referenced to the TMS using adamantine as an external standard. All results shown have been recorded at room temperature at 12 kHz MAS frequency.

The mass spectrometry analyses were performed using an ion trap (AmaZon SL, Bruker) equipped with an electrospray ion source (ESI) operated in positive or negative ion mode. Samples were prepared in 1 mg/mL in CH2Cl2 and diluted by 100 in a solvent mix of 46.1% methanol, 38.4% dichloromethane, 15.4% ultra-pure Elga water, and 0.1% formic acid, before being injected at 10 µL/min into the mass spectrometer.

The infrared spectra were obtained by diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectroscopy on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet TM iS TM 50 IR-TF spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The spectra were recorded from 4000 to 400 cm−1 at room temperature.

The elemental analysis of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen was recorded on a Thermo Scientific FlashSmartTM Elemental Analyzer. The elemental analysis of Pd was carried out by ICP-AES (Icap 6500 DUO-Thermo Scientific) by the Crealins Company (6NAPSE group, Lyon, France) at Villeurbanne.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed on a PANalyticalX’Pert Pro diffractometer equipped with an X’Celerator Scientific detector and a Cu anticathode (Kα1/Kα2) (Malvern Panalytical, Limeil-Brévannes, France). Intensities were collected at 150 K by means of the CrysAlisPro software v43.22a. Reflection indexing, unit-cell parameters refinement, Lorentz-polarization correction, peak integration, and background determination were carried out with the CrysalisPro software.

Electron microscopy analyses were carried out at the Centre Technologies of Microstructures (CTµ), a platform of the Université Claude Bernard Lyon1, Villeurbanne, France. A drop of a water dispersion was deposited on a copper grid (200 mesh), and the solvent was allowed to evaporate. Samples were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at room temperature with a JEOL (Peabody, MA, USA) 2100F high-resolution microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 200 Kv (JEOL Europe SAS, Croissy-sur-seine, France). The specimen holder was tilted at 15° (with respect to the energy-dispersive detector). HAADF-STEM was carried out at the Centre Technologies of Microstructures (CTµ), a platform of the Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France. A drop of a water dispersion was deposited on a carbon grid (200 mesh), and the solvent was allowed to evaporate. Samples were observed by HAADF-STEM at room temperature with a JEOL 2100F high-resolution microscope.

Textural properties were investigated by determining the specific surface areas of materials using the Micrometrics ASAP 2020 system, which is based on the BET method (Micromeritics France SA, Merignac, France). Prior to measurement, solids were desorbed at 423 K (150 °C) for 3 hrs. Nitrogen (N2) gas was used as adsorptive gas and relative pressure (P/P0) was varied from 0.019 to 0.986.

4.3. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 in Diluted Ionic Liquid

All reactions were carried out under CO2 atmosphere (CO2 bubbling) and UV-vis irradiation (MAX-303 Xenon light source 300 W, 300–600 nm using UV-VIS mirror module, Asahi Spectra Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), at room temperature. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 was performed in a 25 mL Pyrex glass tube, and a glass flask was connected by a tee joint for vacuum, CO2, or Argon purging and gas sampling in the system. Typically, 6 mg of NS-TiO2/Pd or of NS-g-C3N4/Pd, 3 mL H2O and 0.4 mmol of selected ILs or salts were added in the 25 mL glass Pyrex tube, under ultrasonic for 10 min to mix all of them well, then, with CO2 or Argon bubbling for 45 min without any light, later, the reactor was vacuumed and purged 3 times with CO2 or Argon at 1 bar pressure. The stirred medium was exposed to UV-vis irradiation for 4 or 20 h, after 2 gas syringes (2 × 500 µL) containing a Hamilton sample lock valve were removed for multinuclear NMR, TCD, and FID of GC analyses, respectively.

The gas analyses were performed with a gas chromatograph (HP 6890) equipped with an HP-PLOT Mole sieve column (TCD) and a GS-carbon PLOT column (JetanizerTM/FID) to detect the production of CO, H2, and other possible reduction products. A standard calibration curve was made to quantify the CO yield. Calibration curve for CO and CH4 was determined following the equation Y(mol) = 3.23 × 1011X − 2.68 × 10−10 and Y(mol) = 3.77 × 10−11X for H2. The GCMS analysis was performed in an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) 6850 (GC)/5975C (MS) under EI (electron impact) mode. The GCMS was equipped with a PoraBond Q column; the oven was kept at 60 °C during the analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the central role of ionic liquids, and in particular, C1C4ImOAc, in governing photocatalytic reactivity under aqueous UV–vis irradiation. In the absence of a heterogeneous catalyst, C1C4ImOAc enables selective CO formation via CO2 pre-activation, confirming its dual role as both photosensitizer and activator, in agreement with previous reports. When coupled with nanosheet photocatalysts, however, new reactivity emerges: in g-C3N4 systems, methane is predominantly formed through the photo-Kolbe decomposition of acetate, while in TiO2 systems, multiple pathways coexist, combining CO2 reduction, H2O splitting, and acetate photodecomposition. From a mechanistic standpoint, these findings clarify the origin of methane in such systems, ruling out CO2 as the primary carbon source under certain conditions. The results also underline the sensitivity of CO2 photoreduction to the interplay between photocatalyst surface properties, ionic liquid structure, and reaction medium. Anion basicity and pH emerge as decisive factors: alkaline environments or low-basicity anions suppress carbon product formation and enhance H2 evolution.

Looking ahead, several directions arise. First, suppressing the competing photo-Kolbe reaction will be essential to distinguish genuine CO2 reduction from acetate photodecomposition. Strategies may include tailoring OAc–based IL structures to avoid strong interaction with g-C3N4 surface (i.e., steric hindrance) or to enhance its affinity with water (i.e., introduction of –OH group) in order to increase its availability in solution for the photoreduction of CO2. For metal-based support, a less basic anion than OAc must be used in order to avoid strong surface interaction. Second, engineering photocatalyst surfaces to modulate IL–support interactions could also provide selective control over electron transfer pathways. For TiO2, introducing cocatalysts or defect engineering may mitigate its strong bias toward hydrogen evolution. These findings highlight that mastering the support–electrolyte (ionic liquid) interface is the key to directing multi-electron photocatalytic processes—offering a powerful strategy to rationally design next-generation hybrid systems for selective CO2 photoconversion and solar fuel, as well as hydrogen, production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121128/s1, Figure S1: XRD of in situ loading Pd-NPs onto NS-TiO2 in H2O; Figure S2: XRD (a) and TEM images (b) of synthesized g-C3N4; Figure S3: Powder XRD pattern (a), HAADF-STEM (b) and TEM images (c,d) of NS-g-C3N4/Pd Inset (c): Pd nanoparticles histogram from [15]. Table S1: Photocatalytic data in the presence of ionic liquid or salts diluted in H2O.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and C.C.S.; methodology, S.D. and C.C.S.; validation, S.D., C.C.S. and K.-C.S.; formal analysis, Y.P.; investigation, Y.P., P.-Y.D. and K.-C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P. and C.C.S.; writing—review and editing, S.D. and C.C.S.; supervision, S.D. and C.C.S.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The PhD scholarship for Yulan PENG has been funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Kinetic study of NS-TiO2/Pd in diluted C1C4ImOAc under argon (Ar) or CO2. Production (a) of CH4, (b) of CO, and (c) of H2.

References

- Garcia, J.A.; Villen-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez-Maroto, J.M.; Paz-Garcia, J.M. Technical analysis of CO2 capture pathways and technologies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.L.; Baruch, M.F.; Pander, J.E.; Hu, Y.; Fortmeyer, I.C.; Park, J.E.; Zhang, T.; Liao, K.; Yan, Y.; Shaw, T.W.; et al. Light-driven heterogeneous reduction of carbon dioxide: Photocatalysts and photoelectrodes. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12888–12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Peng, B.; Peng, T. Recent advances in heterogeneous photocatalytic CO2 conversion to solar fuels. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7485–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Mohamed, A.R.; Ong, W.-J. Z-scheme photocatalytic systems for carbon dioxide reduction: Where are we now? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 56, 22894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisreutinger, S.N.; Schmidt-Mende, L.; Stolarczyk, J.K.; Kumaravel, V.; Bartlett, J.; Pillai, S.C. Photoelectrochemical conversion of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) into fuels and value-added products. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 486–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.A.; Salehi-Khojin, A.; Thorson, M.R.; Zhu, W.; Whipple, D.T.; Kenis, P.J.A.; Masel, R.I. Ionic Liquid–Mediated Selective Conversion of CO2 to CO at Low Overpotentials. Science 2011, 334, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.A.; Haan, J.L.; Mukherjee, P.; Braunschweig, B.; Zhu, W.; Salehi-Khojin, A.; Dlott, D.D.; Masel, R.I. In Situ Spectroscopic Examination of a Low Overpotential Pathway for Carbon Dioxide Conversion to Carbon Monoxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 15307–15312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Leal, B.C.; Lozano, P.; Monteiro, A.L.; Migowski, P.; Scholten, J.D. Ionic Liquids in Metal, Photo-, Electro-, and (Bio)Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 329–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.I.; Dupont, J. Thermo- and Photocatalytic Activation of CO2 in Ionic Liquids Nanodomains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, L.; Bica-Schröder, K. Photocatalytic Carbon Dioxide Reduction with Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zeng, L.; Huang, L. Understanding the Roles of Ionic Liquids in Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 5546–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, R. Ionic Liquid-Catalyzed CO2 Conversion for Valuable Chemicals. Molecules 2024, 29, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Huang, H.; Bai, L.; Zhao, X.; Qu, B.; Xiong, L.; Bai, F.; Tang, J.; Jing, L.; et al. Improving CO2 Photoconversion with Ionic Liquid and Co-Catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2713. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Szeto, K.C.; Santini, C.C.; Daniele, S. Ionic Liquids as homogeneous photocatalyst for CO2 reduction in protic solvents. Chem. Engin. J. Adv. 2022, 12, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Szeto, K.C.; Santini, C.C.; Daniele, S. Study of the Parameters Impacting the Photocatalytic Reduction of Carbon Dioxide in Ionic Liquids. Chem. Photo. Chem. 2021, 5, 721–726. [Google Scholar]

- Qadir, M.I.; Zanatta, M.; Gil, E.S.; Stassen, H.K.; Gonçalves, P.; Neto, B.A.; Dupont, J. Photocatalytic Reverse Semi-Combustion Driven by Ionic Liquids. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordness, O.; Brennecke, J.F. Ion Dissociation in Ionic Liquids and Ionic Liquid Solutions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12873–12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, M.; Roth, C.; Kubatzki, F.; Ludwig, R. Formation of “quasi” contact or solvent-separated ion pairs in the local environment of probe molecules dissolved in ionic liquids. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J. On the Solid, Liquid and Solution Structural Organization of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2004, 15, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhu, M. Ultrathin two-dimensional semiconductors for photocatalysis in energy and environment applications. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 6147–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, C.; Long, R.; Xiong, Y. Photocatalyst design based on two-dimensional materials. Mat. Today Chem. 2019, 11, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Kuang, Q.; Jin, M.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, L. Synthesis of titania nanosheets with a high percentage of exposed (001) facets and related photocatalytic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3152–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yan, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, X.; Yan, P.; Li, H. Photoinduced Zn-Air Battery-Assisted Self-Powered Sensor Utilizing Cobalt and Sulfur Co-Doped Carbon Nitride for Portable Detection Device. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2408293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.; Sohail, M.; Shah Syed, J.A.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Mohammed, M.H.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Taha, T.A.; Al-Salem, H.S.; Alenad, A.M.; Amin, M.A.; et al. Recent Advancement of the Current Aspects of g-C3N4 for its Photocatalytic Applications in Sustainable Energy System. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D. High-Efficiency g-C3N4 Based Photocatalysts for CO2 Reduction: Modification Methods. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2022, 4, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azofra, L.M.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Sun, C. A DFT study of planar vs. corrugated graphene-like carbon nitride (g-C3N4) and its role in the catalytic performance of CO2 conversion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 18507–18514. [Google Scholar]

- Kraeutler, B.; Jaeger, C.D.; Bard, A.J. Direct observation of radical intermediates in the photo-Kolbe reaction-heterogeneous photocatalytic radical formation by electron spin resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 4903–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ni, X.; Chen, W.; Weng, Z. The observation of photo-Kolbe reaction as a novel pathway to initiate photocatalytic polymerization over oxide semiconductor nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2008, 195, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lou, S.N.; Ohno, T. Photocatalytic Reforming of Acetic Acid into Methane over Pt/TiO2. Mater. Lett. 2023, 347, 134552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, T.; Kawai, T.; Hashimoto, K. Heterogeneous photocatalytic reactions of organic acids and water. New reaction paths besides the photo-Kolbe reaction. J. Phys. Chem. 1984, 88, 2344–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodembusch, F.S.; Albuquerque, B.L.; Gonçalves, W.D.; Morais, J.; Baptista, D.L.; de Moraes Lisbôa, A.; Dupont, J. Photocatalytic effects on Au@TiO2 confined in BMIm.NTf2 ionic liquid for hydrogen evolution reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 31629–31642. [Google Scholar]

- Can, E.; Uralcan, B.; Yildirim, R. Enhancing charge transfer in photocatalytic hydrogen production over dye-sensitized Pt/TiO2 by ionic liquid coating. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 10931–10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).