Advances in Strategies for In Vivo Directed Evolution of Targeted Functional Genes

Abstract

1. Introduction

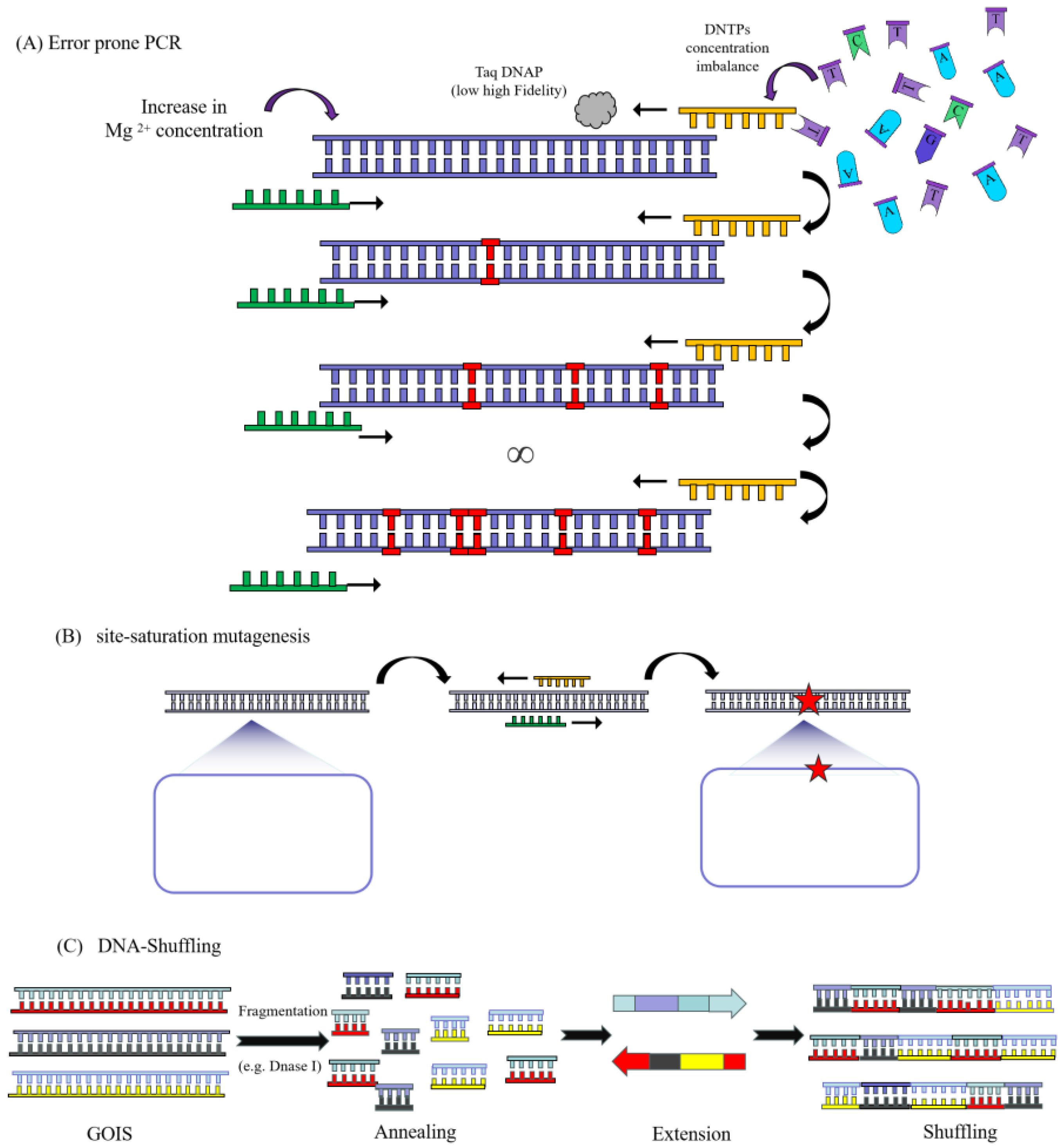

2. In Vivo Targeted Gene Hypermutation

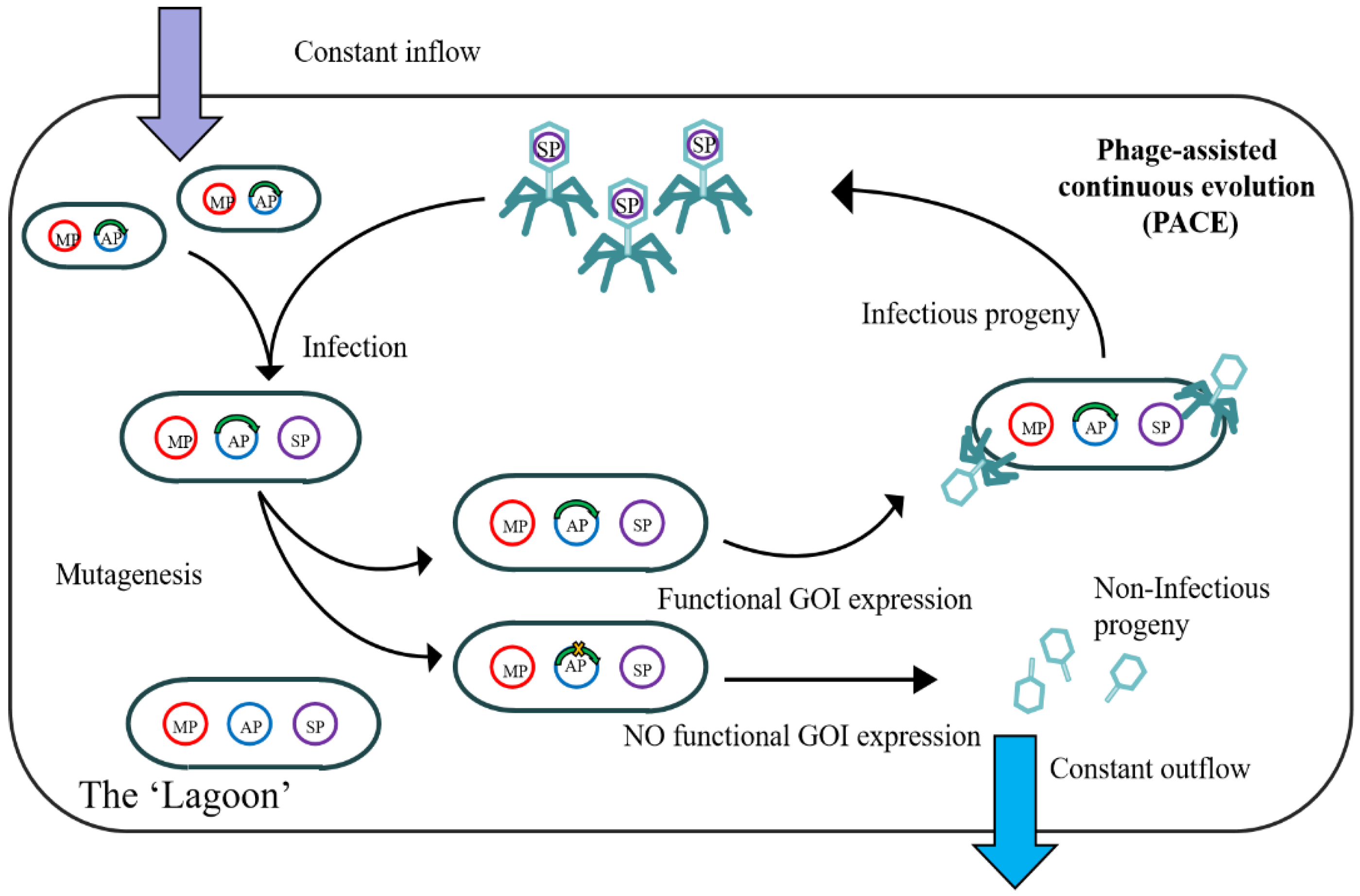

2.1. Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution

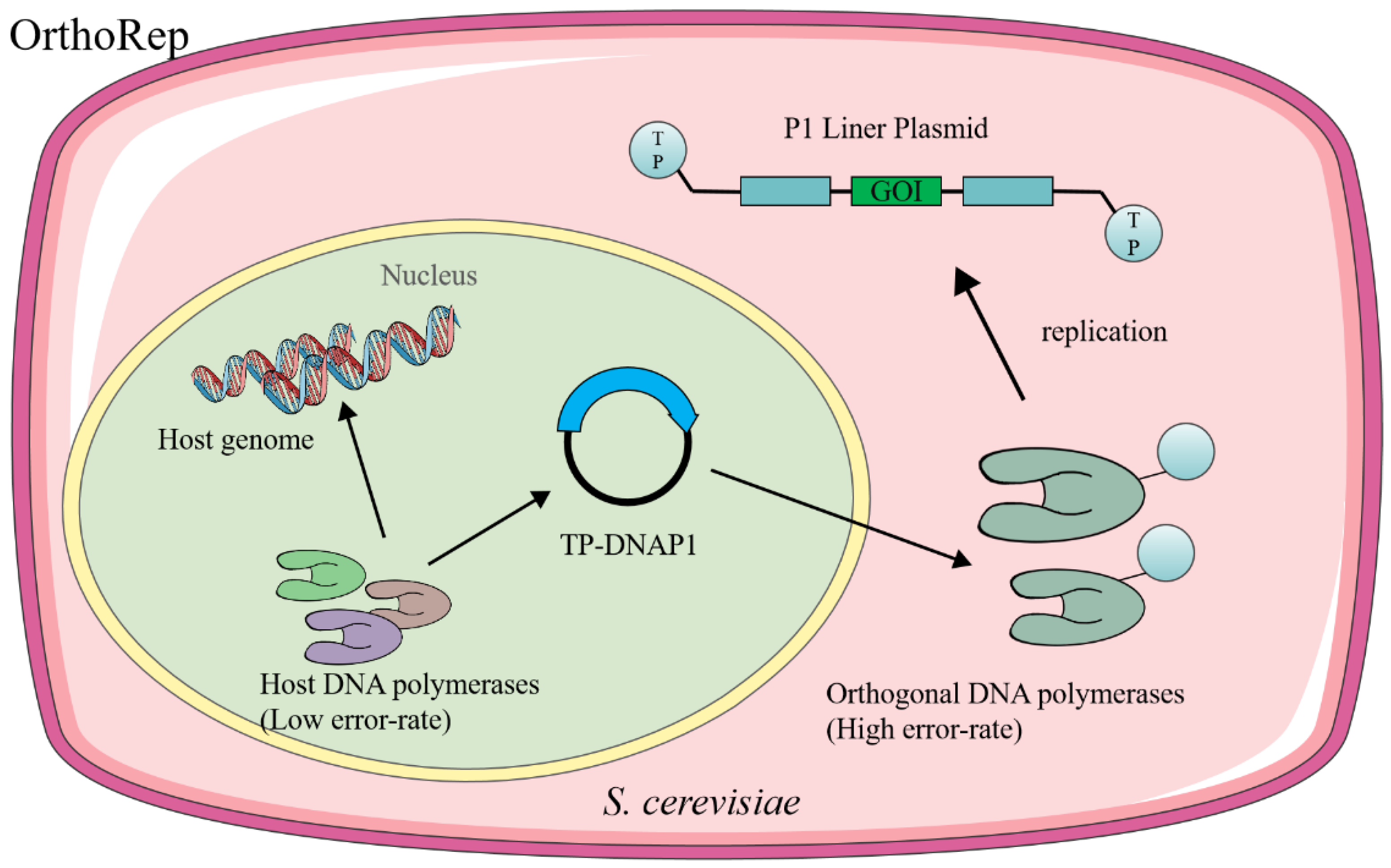

2.2. Orthogonal DNA Replication Systems

2.2.1. Yeast Orthogonal System: OrthoRep

2.2.2. Bacterial Orthogonal Systems

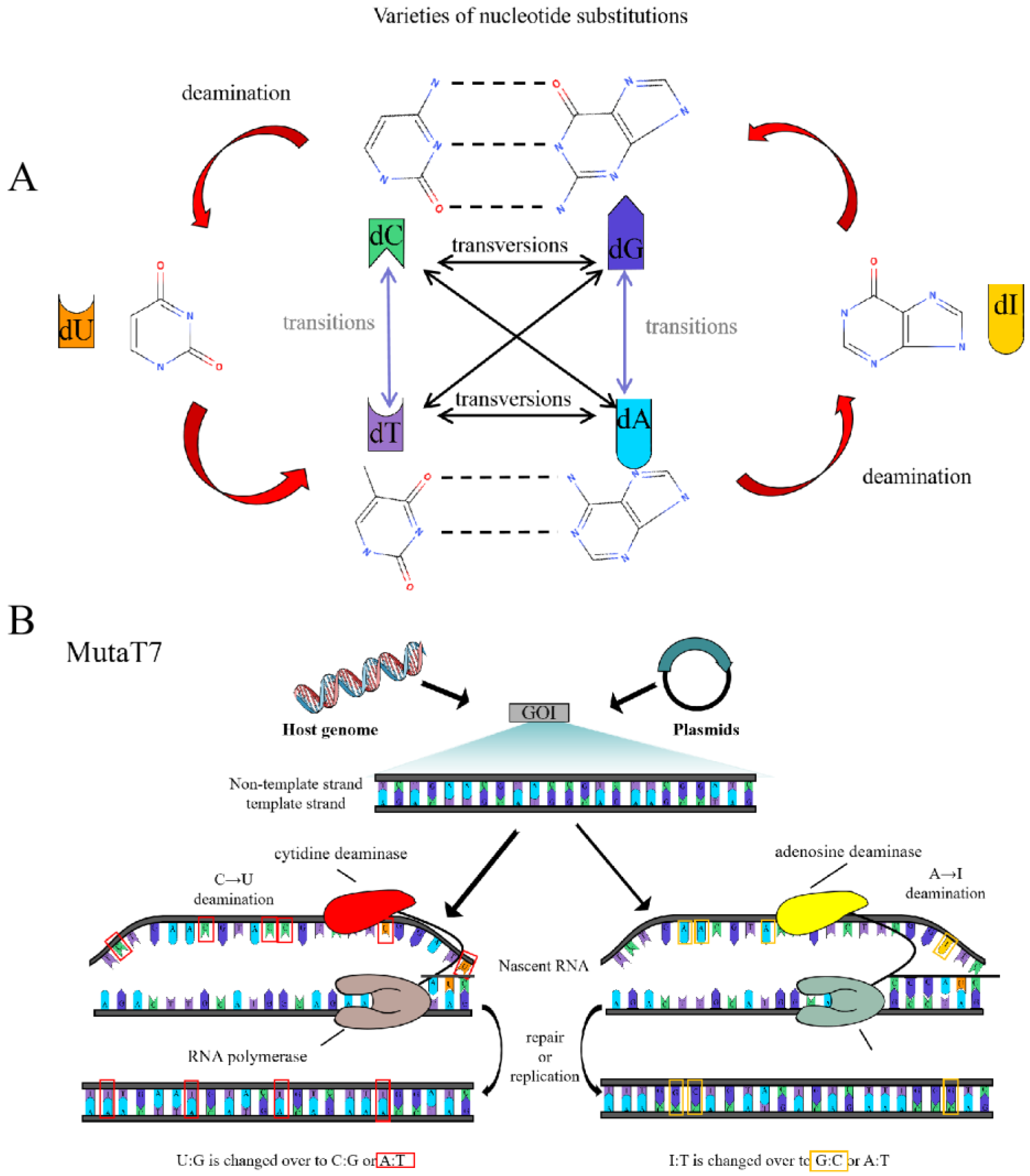

3. Heterologous Polymerase-Mediated Targeted Hypermutation

3.1. Transcriptional Targeted Mutation System

3.2. Retron-Mediated Evolution Systems

| Host | Mutation Rate (Substitutions per Base) | Evolution Speed (Days) | Fold | Target Gene Length Capacity | Mutational Spectrum | Mutator Module | Feature | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MutaT7 | E. coli | 6.7 ×10−6 | 7–15 | 38,000 | 10 kb | C→T | rApo1, UGI | High targeting, low off-target mutations, suitable for multi-KB regions, and dependent on Δung or UGI. | [68] |

| eMutaT7 | E. coli | 9.4 × 10−5 | 1−2 | 340,000 | 5 kb | C→T | PmCDA1 | Strong gene specificity, adjustable induction, low cytotoxicity, and dependent on the T7 promoter. | [69] |

| eMutaT7transition | E. coli | 3.6 × 10−5 | 2−3 | 130,000 | 5 kb | C:G→T:A, A:T→G:C | PmCDA1, TadA-8e | It can target multiple genes, but long-term culture is prone to recombination. | [70] |

| T7-DIVA | E. coli | 10−1 | 2−3 | 100,000 | 2 kb | C:G→T:A, A:T→G:C | pmCDA1, TadA, crRNA | dCas9 defines the mutation boundary, cross-bacterial/eukaryotic host potential, but relies on genomic integration. | [71] |

| CgMutaT7 | C. glutamicum | 1 × 10−5–1.2 × 10−5 | 10−15 | 12,000 | 1.8 kb | C→T | PmCDA1, UGI | Adapt to specific hosts and fill the gap in tools. However, the target length is insufficient and the evolution cycle is relatively slow. | [72] |

| BS-MutaT7A, BS-MutaT7C | B. subtilis | 1.2 × 10−5, 5.8 × 10−5 | 3−10 | 7000 folds and 37,000 | 5 kb | A:T→G:C, C:G→T:A | TadA8e, PmCDA1 | It is suitable for the evolution of long segments of genes and has high sustainability. However, the system needs to be screened and adapted. | [73] |

| OTM | E. coli, H. bluephagenesis | 3.9 × 10−4 | 1 | 1,500,000 | 5 kb | A:T→G:C, C:G→T:A | PmCDA1, TadA8e, UGI | High orthogonality but dependent on specific phage promoters. | [74] |

| TRIDENT | S. cerevisiae | >10−3 | 1−11 | 10,000,000 | 3 kb | Wide | PmCDA1, yeTadA1.0, Msh6p and Apn2p | High mutation specificity, needs genomic modification, exogenous promoter-dependent. | [76] |

| TRACE | Human Embryonic Kidney 293T cells | >10−3 | 3−7 | 14.7–31 | 2 kb | C→T, G→A | AID*Δ, UGI | Human cell-applicable, with continuous mutation, dynamically controllable; relies on genomic integration, narrow mutation spectrum. | [77] |

| Retroelement | E. coli | 6.3 × 10−7 | 1−2 | 390 | 100 bp | wide | EP-T7RNAP | Supports insertion/deletion/multi-point programming editing, but the editing length is short and depends on specific strains. | [80] |

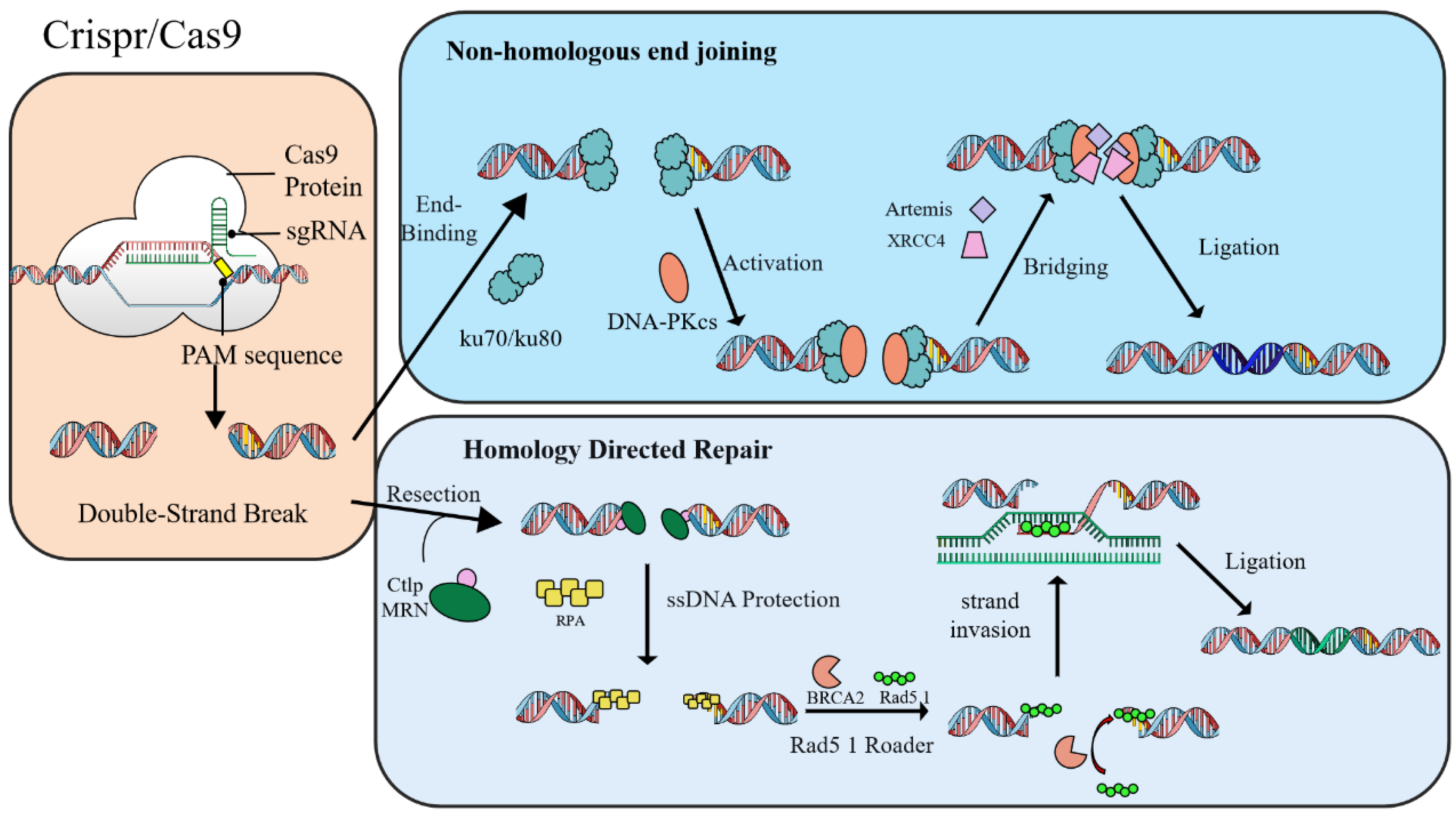

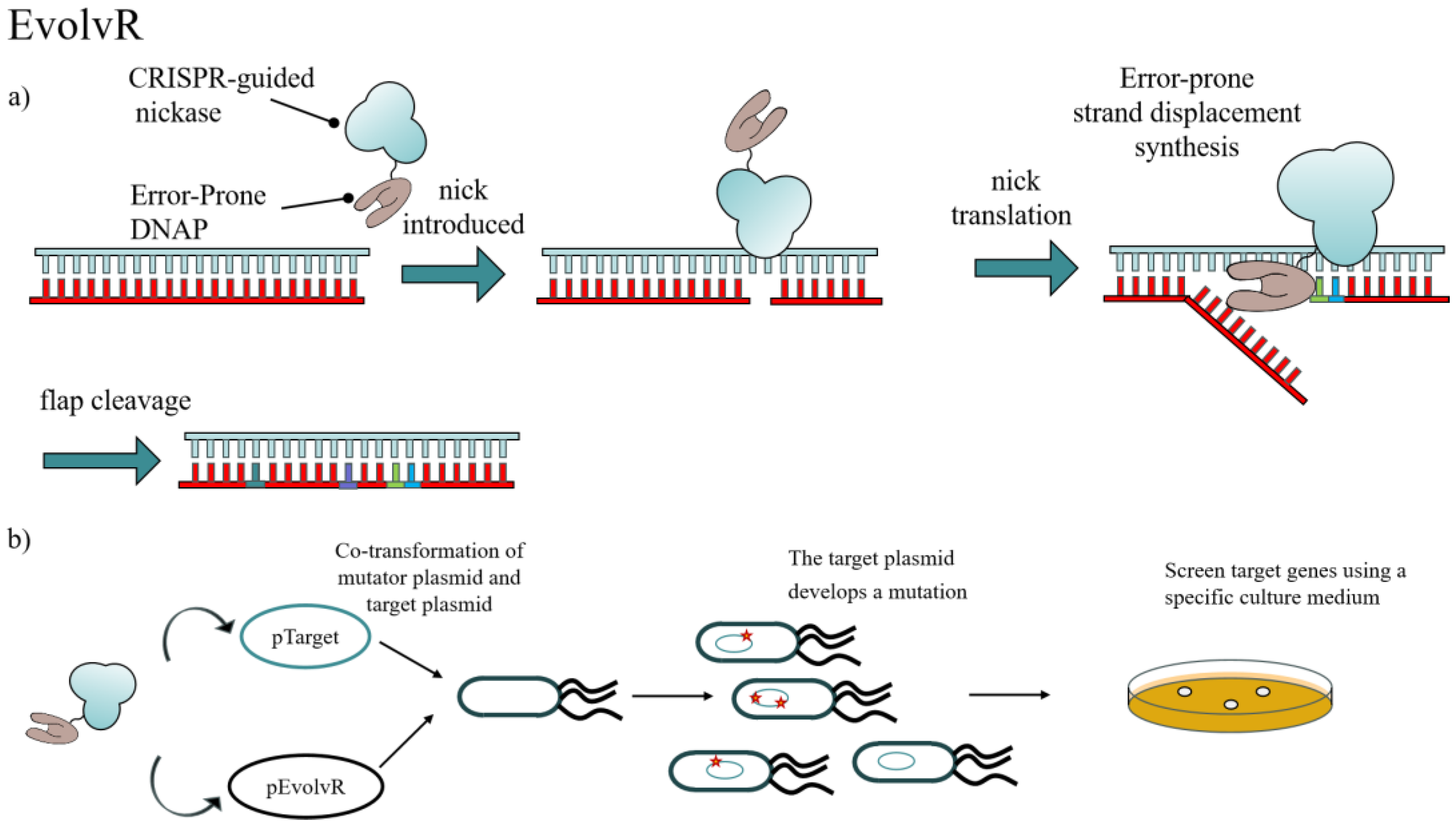

3.3. CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Continuous Evolution Systems

4. Applications of In Vivo Chromosomal Hypermutation

4.1. Directed Evolution of Enzymes

4.2. Directed Evolution of Target Genes for Improved Strain Performance

| Evolution System | Evolved Target | Performance Metric | Improvement/Final Performance | Evolution Duration | Selection Pressure | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PACE | T7 RNA Polymerase | Activity on T3 promoter | >200-fold increase | 8 days (200 generations) | Promoter swapping | [40] |

| PANCE | aaRs | Combining binding affinity and catalytic efficiency | tRNAPyl binding affinity and catalytic efficiency improved by up to 10-fold | 72–84 h | Phage survival | [43] |

| ALT-PANCE | Pyrrolysine pathway | Intracellular Pyl level | 4.5-fold increase | 34–40 rounds | Reduced BocK, increased amber codons | [48] |

| IntePACE | PhiC31 Serine Integrase | Recombination efficiency | 15.4- to 70.2-fold increase over initial mutant | 212 h | Split-pIII system | [49] |

| IntePACE | Bxb1 Serine Integrase | Recombination efficiency in HEK293T cells | 80% integration efficiency | 9 days | Split-pIII system | [49] |

| OrthoRep | Dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR) | Pyrimethamine resistance | 87% populations (78/90) adapted to 3 mM | 87 generations | Gradient pyrimethamine (100 μM to 3 mM) | [50] |

| BacORep | Methanol assimilation pathway | Methanol consumption | 7.4-fold increase (to 8.3 g/L) | 20 passages | Methanol as sole carbon source | [56] |

| EcORep | tetA | Tigecycline resistance | 150-fold increase (to 37 μg/mL) | 12 days | Gradient antibiotic | [60] |

| T7-ORACLE | TEM β-lactamase | Resistance to aztreonam & cephalosporins | 5000-fold increase | <1 week | Antibiotic gradient | [63] |

| OrthoRep | Mucinivorans hirudinis THI4 | Growth rate in thiamine-free medium | Show similar activity to yeast THI4 | Several weeks | Thiamine-free MOPS minimal medium | [67] |

| eMutaT7 | TEM β-lactamase | Cefotaxime (CTX) MIC | 10,000-fold increase | 32 h (8 rounds) | Gradient CTX concentration | [68] |

| eMutaT7 | DegP protease | Growth at 44 °C | Restored function of impaired mutant | 32 h | Gradient temperature (37 °C to 44 °C) | [68] |

| eMutaT7transition | TEM β-lactamase | Cefotaxime (CTX) MIC | >10,000-fold increase (to 4000 μg/mL) | 48 h | Gradient CTX concentration | [70] |

| CgMutaT7 | XylA | Enzyme activity | 23.68% increase | 246 h | Growth rate | [72] |

| BsMutaT7 | tetK | Tigecycline resistance | MIC increased from 0.25 to 8 μg/mL | 10 days | Gradient antibiotic | [73] |

| TRIDENT | Dihydrofolate reductase | Pyrimethamine resistance | 98% populations (177/180) resistant to 3 mM | 11 days (5 rounds) | 3 mM pyrimethamine | [76] |

| OTM | RpoD | Cell growth in 6 g/L L-arginine | 84% increase in cell mass | <24 h | High L-arginine concentration | [74] |

| TRACE | MEK1 | Resistance to selumetinib/trametinib | Survival under 1 μM inhibitor | 3 days mutagenesis + 2 weeks selection | 1 μM inhibitor | [77] |

| EvolvR | rpsL/rpsE | Spectinomycin resistance | Growth at 1000 μg/mL | 36 h | Dual antibiotic selection | [89] |

| targeted mutagenesis toolkit | CAN1 | CAN formation rate | From WT background (-10−6) to 10−2, 104-fold improvement | 2 days | SD-Arg+Can agar plates (60 mg/L canavanine, arginine depletion) | [91] |

| CoMuTER | SEC14 | Resistance to NPPM antifungals | Growth in 3 μM NPPM 481 (no growth in control) | 48 h | 3 μM NPPM | [92] |

| sgRNA transient expression | natural product biosynthetic gene clusters | Echinocandin B (ECB) production | ECB production: From 52.3 mg/L to 120 mg/L, 2.3-fold improvement | 24 days | Screening for colonies with reduced byproducts and enhanced ECB production | [93] |

| OrthoRep | aaRS | Relative Readthrough Efficiency (RRE) Limit of Detection (LOD) for ncAA concentration ncAA-dependent fluorescence ratio | RRE: Exhibited 2.42 to 31.26-fold increase LOD: Reduced 29 to 8500-fold ncAAs: 13 identified with functional variants in E. coli | Several weeks | FACS with ratiometric reporter | [94] |

| PACE | TEV Protease | Cleavage of HPLVGHM sequence | Activity comparable to wild-type on native substrate | 2500 generations | Phage survival coupled to cleavage | [96] |

| PACE, PANCE | ABE (TadA) | Deamination kinetics | 590-fold increase | 25 generations + 84 h | Phage survival | [97] |

| BE-PACE | CBE | Editing efficiency at marginal GC sites | Better than APOBEC1, eliminated GC preference | Hundreds of hours | Phage survival | [99] |

| PANCE | Bacillus methanolicus methanol dehydrogenase 2 | In vitro enzyme kinetic parameters and the assimilation rate of methanol to the central metabolite | 3.5-fold Vmax boost and 2-fold higher methanol assimilation | 70 generations | Methanol concentration gradient | [100] |

| PACE | Bicyclomycin biosynthetic gene cluster | Increase the yield t of BCM | BCM yield in E. coli: 20-fold increase (0.03→0.6 μg/mL) | 216 h | Split-pIII system | [101] |

| PACE | CRISPR-associated transposases

(CAST) | Gene integration efficiency, transgenic expression level | 420-fold more active than wild-type | 296 h of PACE + 76 PANCE passages | Transposition activity is coupled with phage proliferation | [102] |

| OrthoRep | tryptophan synthase β-subunit | Standalone tryptophan synthesis activity, Thermoadaptation signatures | Gained standalone function in yeast, enriched mesophilic amino acid replacements; | 3 months | gradually reducing exogenous tryptophan and indole supply | [103] |

| OrthoRep | Prime Editor | Base editing efficiency | Editing efficiency is 3.5-folds that of PEmax | Several weeks | Histidine-deficient medium and long fragment insertion screening | [104] |

| OrthoRep | Thermotoga maritima HisA | Growth rate | Supports the growth of yeast under histidine free conditions | 600 h | Histidine concentration gradually decreased | [105] |

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Movahedpour, A.; Ahmadi, N.; Ghalamfarsa, F.; Ghesmati, Z.; Khalifeh, M.; Maleksabet, A.; Shabaninejad, Z.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Savardashtaki, A. β-Galactosidase: From its source and applications to its recombinant form. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Fu, R.; Wei, F. Microbial proteases and their applications. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1236368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naim, M.; Mohammat, M.F.; Mohd Ariff, P.N.A.; Uzir, M.H. Biocatalytic approach for the synthesis of chiral alcohols for the development of pharmaceutical intermediates and other industrial applications: A review. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2024, 180, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.L.; Wu, W.K.; Nie, G.B.; Li, J.X.; Fang, X.; Sheng, Y.G.; Wang, M.M.; Zheng, Q.Y.; Guo, X.X.; Huang, J.F.; et al. A dirigent protein redirects extracellular terpenoid metabolism for defense against biotic challenges. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlgemuth, R. Enzyme Catalysis for Sustainable Value Creation Using Renewable Biobased Resources. Molecules 2024, 29, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Prieto-Vivas, J.E.; Voordeckers, K.; Bi, C.; Verstrepen, K.J. Mutagenesis techniques for evolutionary engineering of microbes—Exploiting CRISPR-Cas, oligonucleotides, recombinases, and polymerases. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 884–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Salazar, A.; Chen, I.A. In vitro evolution: From monsters to mobs. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, R580–R583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korendovych, I.V. Rational and Semirational Protein Design. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1685, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, S.C.; Knight, A.M.; Arnold, F.H. Design and evolution of enzymes for non-natural chemistry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Rocha, C.G.; Ferla, M.; Reetz, M.T. Directed Evolution of Proteins Based on Mutational Scanning. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1685, 87–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeymer, C.; Hilvert, D. Directed Evolution of Protein Catalysts. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf-Bryfogle, J.; Teets, F.D.; Bahl, C.D. Toward complete rational control over protein structure and function through computational design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 66, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Fan, T.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Yu, C.; Nie, S.; Qi, Y.; Zheng, W.M.; Han, J.; Fan, Z.; et al. Accurate and efficient protein sequence design through learning concise local environment of residues. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ouyang, X.; Meng, S.; Zhao, B.; Liu, L.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Shi, T.; et al. Rational multienzyme architecture design with iMARS. Cell 2025, 188, 1349–1362.e1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupec, M.; Culka, M.; Machara, A.; Macháček, S.; Bím, D.; Svatoš, A.; Rulíšek, L.; Pichová, I. Understanding desaturation/hydroxylation activity of castor stearoyl Δ(9)-Desaturase through rational mutagenesis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Talley, J.; Haynie, C.; Ebbert, J.; Kubalek, C.; Argyle, M.; Allen, D.; Heaps, W.; Green, T.; Chipman, D.; et al. Advancing Luciferase Activity and Stability beyond Directed Evolution and Rational Design through Expert Guided Deep Learning. Biorxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, W.; Hong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, P. Machine learning-assisted rational design and evolution of novel signal peptides in Yarrowia lipolytica. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2025, 10, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, W.; Pu, Z.; Yu, H. Rational design of enzyme activity and enantioselectivity. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1129149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Luo, X.; Shen, W.; Cao, Y.; Peplowski, L.; Chen, X. Development of thermostable sucrose phosphorylase by semi-rational design for efficient biosynthesis of alpha-D-glucosylglycerol. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7309–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jiao, L.; Shen, J.; Chi, H.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; Lu, F.; Zhu, P. Enhancing the Catalytic Activity of Type II L-Asparaginase from Bacillus licheniformis through Semi-Rational Design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Xu, L.; Cheng, K.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Z. Enhancing the imidase activity of BpIH toward 3-isobutyl glutarimide via semi-rational design. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Guan, J.; Nie, Y. Semi-Rational Design of L-Isoleucine Dioxygenase Generated Its Activity for Aromatic Amino Acid Hydroxylation. Molecules 2023, 28, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeiros-Borja, C.E.; Surpeta, B.; Brezovsky, J. Recent advances in user-friendly computational tools to engineer protein function. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, T.; Lin, F. [Semi-rational design improves the catalytic activity of butyrylcholinesterase against ghrelin]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao = Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 4228–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jameel, A.; Xing, X.H.; Zhang, C. Advanced strategies and tools to facilitate and streamline microbial adaptive laboratory evolution. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.S.; Rix, G.; Mengiste, A.A.; Alvarez, B.; Seo, D.; Chen, H.; Hurtado, J.; Zhang, Q.; Donato García-García, J.; Heins, Z.J.; et al. In vivo hypermutation and continuous evolution. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Deng, Y.; Yang, G.Y. Growth-coupled high throughput selection for directed enzyme evolution. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 68, 108238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, F.H. Directed Evolution: Bringing New Chemistry to Life. Angew. Chem. 2018, 57, 4143–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nearmnala, P.; Thanaburakorn, M.; Panbangred, W.; Chaiyen, P.; Hongdilokkul, N. An in vivo selection system with tightly regulated gene expression enables directed evolution of highly efficient enzymes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Á.; Vila, J.C.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Diaz-Colunga, J.; Estrela, S.; Rebolleda-Gomez, M. Directed Evolution of Microbial Communities. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2021, 50, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpay, B.A.; Desai, M.M. Effects of selection stringency on the outcomes of directed evolution. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellés Vidal, L.; Isalan, M.; Heap, J.T.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. A primer to directed evolution: Current methodologies and future directions. RSC Chem. Biol. 2023, 4, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Feng, M.; Xia, H. In vitro generation of genetic diversity for directed evolution by error-prone artificial DNA synthesis. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, P. Current Status and Applications of Adaptive Laboratory Evolution in Industrial Microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Khey, J.; Kazlauskas, R.J.; Travisano, M. Plasmid hypermutation using a targeted artificial DNA replisome. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, abg8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conners, R.; León-Quezada, R.I.; McLaren, M.; Bennett, N.J.; Daum, B.; Rakonjac, J.; Gold, V.A.M. Cryo-electron microscopy of the f1 filamentous phage reveals insights into viral infection and assembly. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taslem Mourosi, J.; Awe, A.; Guo, W.; Batra, H.; Ganesh, H.; Wu, X.; Zhu, J. Understanding Bacteriophage Tail Fiber Interaction with Host Surface Receptor: The Key “Blueprint” for Reprogramming Phage Host Range. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, J.; Young, R. Phage Lysis: Multiple Genes for Multiple Barriers. Adv. Virus Res. 2019, 103, 33–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiyama, T.; Ichii, T.; Yomo, T.; Ichihashi, N. Automated in vitro evolution of a translation-coupled RNA replication system in a droplet flow reactor. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.M.; Wang, T.; Liu, D.R. Phage-assisted continuous and non-continuous evolution. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 4101–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Jian, X.; Xing, X.; Zhang, C. In vivo continuous evolution of metabolic pathways for chemical production. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xue, P.; Cao, M.; Yu, T.; Lane, S.T.; Zhao, H. Directed Evolution: Methodologies and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12384–12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Miller, C.; Guo, L.T.; Ho, J.M.L.; Bryson, D.I.; Wang, Y.S.; Liu, D.R.; Söll, D. Crystal structures reveal an elusive functional domain of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoudjane, S.; Golas, S.; Ather, O.; Hammerling, M.J.; DeBenedictis, E. A Practical Guide to Phage- and Robotics-assisted Near-continuous Evolution. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2024, 203, e65974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBenedictis, E.A.; Chory, E.J.; Gretton, D.W.; Wang, B.; Golas, S.; Esvelt, K.M. Systematic molecular evolution enables robust biomolecule discovery. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.P.; Heins, Z.J.; Miller, S.M.; Wong, B.G.; Balivada, P.A.; Wang, T.; Khalil, A.S.; Liu, D.R. High-throughput continuous evolution of compact Cas9 variants targeting single-nucleotide-pyrimidine PAMs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Lai, W.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C.; He, X.; Zhao, G.; Fu, X.; Liu, C. Exploiting spatial dimensions to enable parallelized continuous directed evolution. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.M.L.; Miller, C.A.; Smith, K.A.; Mattia, J.R.; Bennett, M.R. Improved pyrrolysine biosynthesis through phage assisted non-continuous directed evolution of the complete pathway. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, B.E.; Gupta, S.; Sato, R.; Waller, D.F.; Stoytchev, I.; Short, J.E.; Sharek, L.; Tran, C.T.; Badran, A.H.; Owens, J.B. Directed evolution of hyperactive integrases for site specific insertion of transgenes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Arzumanyan, G.A.; Obadi, M.K.A.; Javanpour, A.A.; Liu, C.C. Scalable, Continuous Evolution of Genes at Mutation Rates above Genomic Error Thresholds. Cell 2018, 175, 1946–1957.e1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzumanyan, G.A.; Gabriel, K.N.; Ravikumar, A.; Javanpour, A.A.; Liu, C.C. Mutually Orthogonal DNA Replication Systems In Vivo. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Ravikumar, A.; Liu, C.C. Tunable Expression Systems for Orthogonal DNA Replication. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 2930–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulk, A.M.; Williams, R.L.; Liu, C.C. Rapidly Inducible Yeast Surface Display for Antibody Evolution with OrthoRep. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 2629–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, M.; Pospíšek, M.; Novák, J.; Mrvová, S.; Krásný, L.; Vopálenský, V. Transcription apparatus of the yeast virus-like elements: Architecture, function, and evolutionary origin. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudek, A.; Krawczyk, P.S.; Mroczek, S.; Tomecki, R.; Turtola, M.; Matylla-Kulińska, K.; Jensen, T.H.; Dziembowski, A. Global view on the metabolism of RNA poly(A) tails in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Zhao, R.; Guo, H.; Yan, K.; Wang, C.; Lu, C.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Du, G.; et al. Engineered bacterial orthogonal DNA replication system for continuous evolution. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 1504–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nies, P.; Westerlaken, I.; Blanken, D.; Salas, M.; Mencía, M.; Danelon, C. Self-replication of DNA by its encoded proteins in liposome-based synthetic cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipe, D.M.; Prichard, A.; Sharma, S.; Pogliano, J. Replication Compartments of Eukaryotic and Bacterial DNA Viruses: Common Themes Between Different Domains of Host Cells. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2022, 9, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntynen, S.; Sundberg, L.R.; Oksanen, H.M.; Poranen, M.M. Half a Century of Research on Membrane-Containing Bacteriophages: Bringing New Concepts to Modern Virology. Viruses 2019, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Rehm, F.B.H.; Czernecki, D.; Gu, Y.; Zürcher, J.F.; Liu, K.C.; Chin, J.W. Establishing a synthetic orthogonal replication system enables accelerated evolution in E. coli. Science 2024, 383, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.K.; Ito, J. Initiation of bacteriophage PRD1 DNA replication on single-stranded templates. J. Mol. Biol. 1991, 222, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.L.; Liu, C.C. Accelerated evolution of chosen genes. Science 2024, 383, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, C.S.; Sondermann, P.; Rong, C.; Gillis, T.G.; Ban, Y.; Wang, C.; Dik, D.A.; Schultz, P.G. An orthogonal T7 replisome for continuous hypermutation and accelerated evolution in E. coli. Science 2025, 389, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkotoky, S.; Murali, A. The highly efficient T7 RNA polymerase: A wonder macromolecule in biological realm. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, C.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Linhardt, R.J. Bacteriophage T7 transcription system: An enabling tool in synthetic biology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.G.; Mancuso, C.P.; Kiriakov, S.; Bashor, C.J.; Khalil, A.S. Precise, automated control of conditions for high-throughput growth of yeast and bacteria with eVOLVER. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, J.D.; Van Gelder, K.; Joshi, J.; Bathe, U.; Leong, B.J.; Bruner, S.D.; Liu, C.C.; Hanson, A.D. Using continuous directed evolution to improve enzymes for plant applications. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.L.; Papa, L.J., 3rd; Shoulders, M.D. A Processive Protein Chimera Introduces Mutations across Defined DNA Regions In Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11560–11564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, S. Gene-specific mutagenesis enables rapid continuous evolution of enzymes in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.; Koh, B.; Eom, G.E.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, S. A dual gene-specific mutator system installs all transition mutations at similar frequencies in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.; Mencía, M.; de Lorenzo, V.; Fernández, L. In vivo diversification of target genomic sites using processive base deaminase fusions blocked by dCas9. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; You, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, M.; Rao, Z. Continuous Evolution of Protein through T7 RNA Polymerase-Guided Base Editing in Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth. Biol. 2025, 14, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Lv, X.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y. T7 RNA polymerase-guided base editor for accelerated continuous evolution in Bacillus subtilis. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2025, 10, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, X.; Ding, J.; Chen, G.Q. An orthogonal transcription mutation system generating all transition mutations for accelerated protein evolution in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengiste, A.A.; McDonald, J.L.; Nguyen Tran, M.T.; Plank, A.V.; Wilson, R.H.; Butty, V.L.; Shoulders, M.D. MutaT7(GDE): A Single Chimera for the Targeted, Balanced, Efficient, and Processive Installation of All Possible Transition Mutations In Vivo. ACS Synth. Biol. 2024, 13, 2693–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, A.; Jamil, O.K.; Kong, D.; Sockolosky, J.T.; Smolke, C.D. Polymerase-guided base editing enables in vivo mutagenesis and rapid protein engineering. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, S.; Padula, S.; Lesman, D.; Griswold, K.; Lin, A.; Zhao, T.; Marshall, J.L.; Chen, F. Efficient, continuous mutagenesis in human cells using a pseudo-random DNA editor. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inouye, M. The first demonstration of the existence of reverse transcriptases in bacteria. Gene 2017, 597, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.J.; Ellington, A.D.; Finkelstein, I.J. Retrons and their applications in genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 11007–11019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.J.; Morrow, B.R.; Ellington, A.D. Retroelement-Based Genome Editing and Evolution. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 2600–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.G.; Goodman, D.B.; Wannier, T.M.; Kaur, D.; Farzadfard, F.; Lu, T.K.; Shipman, S.L.; Church, G.M. High-throughput functional variant screens via in vivo production of single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2018181118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zuo, S.; Shao, Y.; Bi, K.; Zhao, J.; Huang, L.; Xu, Z.; Lian, J. Retron-mediated multiplex genome editing and continuous evolution in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 8293–8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzadfard, F.; Gharaei, N.; Citorik, R.J.; Lu, T.K. Efficient retroelement-mediated DNA writing in bacteria. Cell Syst. 2021, 12, 860–872.e865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Li, J. The evolving CRISPR technology. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaoka, Y.; Berman, J.R.; Cooper, S.B.; Mayerl, S.J.; Chan, A.H.; Zhang, B.; Karlin-Neumann, G.A.; Conklin, B.R. Systematic quantification of HDR and NHEJ reveals effects of locus, nuclease, and cell type on genome-editing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, T.S.; Billon, P.; Diedenhofen, G.; Hayward, S.B.; Taglialatela, A.; Cai, K.; Huang, J.-W.; Leuzzi, G.; Cuella-Martin, R.; Palacios, A.; et al. Stimulation of CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair by an engineered RAD18 variant. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, A.; Malik, F.; Andrabi, K.I. Expansion of the CRISPR/Cas Genome-Sculpting Toolbox: Innovations, Applications and Challenges. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2021, 25, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, A.J.; d’Oelsnitz, S.; Ellington, A.D. Synthetic evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, S.O.; Tou, C.J.; Wong, E.B.; Modavi, C.; Schaffer, D.V.; Dueber, J.E. CRISPR-guided DNA polymerases enable diversification of all nucleotides in a tunable window. Nature 2018, 560, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tou, C.J.; Schaffer, D.V.; Dueber, J.E. Targeted Diversification in the S. cerevisiae Genome with CRISPR-Guided DNA Polymerase I. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 1911–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrekas, C.; Limeta, A.; Siewers, V.; David, F. Targeted In Vivo Mutagenesis in Yeast Using CRISPR/Cas9 and Hyperactive Cytidine and Adenine Deaminases. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 2278–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Prieto-Vivas, J.E.; Cautereels, C.; Gorkovskiy, A.; Steensels, J.; Van de Peer, Y.; Verstrepen, K.J. A Cas3-base editing tool for targetable in vivo mutagenesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, Q.; Pang, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Guo, D.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Cytidine-Base-Editor Mediated Continuous In Vivo Evolution in Aspergillus nidulans. ACS Synth. Biol. 2025, 14, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhata, Y.; Rix, G.; Van Deventer, J.A.; Liu, C.C. Directed evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases through in vivo hypermutation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.H.; Miller, S.M.; Geurts, M.H.; Tang, W.; Chen, L.; Sun, N.; Zeina, C.M.; Gao, X.; Rees, H.A.; Lin, Z.; et al. Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature 2018, 556, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.S.; Rees, H.A.; Liu, D.R. Phage-assisted continuous evolution of proteases with altered substrate specificity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.F.; Zhao, K.T.; Eton, E.; Lapinaite, A.; Newby, G.A.; Thuronyi, B.W.; Wilson, C.; Koblan, L.W.; Zeng, J.; Bauer, D.E.; et al. Phage-assisted evolution of an adenine base editor with improved Cas domain compatibility and activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, D.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Xu, N.; Ding, C.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, C.; Bi, C.; et al. Targeted C-to-T and A-to-G dual mutagenesis system for RhtA transporter in vivo evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e0075223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuronyi, B.W.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Yeh, W.H.; Zheng, C.; Newby, G.A.; Wilson, C.; Bhaumik, M.; Shubina-Oleinik, O.; Holt, J.R.; et al. Continuous evolution of base editors with expanded target compatibility and improved activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, T.B.; Woolston, B.M.; Stephanopoulos, G.; Liu, D.R. Phage-Assisted Evolution of Bacillus methanolicus Methanol Dehydrogenase 2. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.W.; Badran, A.H.; Collins, J.J. Continuous bioactivity-dependent evolution of an antibiotic biosynthetic pathway. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, I.P.; Lampe, G.D.; Eitzinger, S.; Miller, S.M.; Berríos, K.N.; McElroy, A.N.; King, R.T.; Stringham, O.G.; Gelsinger, D.R.; Vo, P.L.H.; et al. Programmable gene insertion in human cells with a laboratory-evolved CRISPR-associated transposase. Science 2025, 388, eadt5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rix, G.; Williams, R.L.; Hu, V.J.; Spinner, A.; Pisera, A.O.; Marks, D.S.; Liu, C.C. Continuous evolution of user-defined genes at 1 million times the genomic mutation rate. Science 2024, 386, eadm9073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, Y.; Böck, D.; Ivașcu, A.; Mathis, N.; Rothgangl, T.; Ioannidi, E.I.; Blaudt, A.C.; Tidecks, L.; Vadovics, M.; Muramatsu, H.; et al. Enhancing prime editor activity by directed protein evolution in yeast. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Wong, B.G.; Ravikumar, A.; Arzumanyan, G.A.; Khalil, A.S.; Liu, C.C. Automated Continuous Evolution of Proteins in Vivo. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Host | Mutation Rate (Substitutions per Base) | Evolution Speed (Days) | Fold | Target Gene Length Capacity | Mutational Spectrum | Mutator Module | Feature | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoRep | S. cerevisiae | 1 × 10−5 | 7–14 | 100,000 | 18 kb | wide | TP-DNAP1 | High eukaryotic mutation rate but narrow yeast-only host range. | [50] |

| BacORep | B. thuringiensis | 6.82 × 10−7 | 3–14 | 6700 | 15 kb | wide | mutant O-DNAP | Stable in Gram-positive bacteria yet low mutation rate. | [56] |

| EcORep | E. coli | 9.13 × 10−7 | 5–12 | 1020 | 16.5 kb | wide | Error-prone ODNAP | Tunable E. coli copy number, needs helper plasmids for transformation. | [60] |

| T7-ORACLE | E. coli | 1.7 × 10−5 | <7 | 100,000 | 13 kb | wide | Error-prone T7RNAP | Ease of use in E. coli, but a lack of inducible replisome control. | [63] |

| Host | Mutation Rate (Substitutions per Base) | Evolution Speed (Days) | Fold | Target Gene Length Capacity | Mutational Spectrum | Mutator Module | Feature | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EvolvR | E. coli | 7.77 × 10−4 | 4–5 | 7,770,000 | 350 bp | Wide | Nickase, Error-prone DNAP | Adjustable mutation rate, multiple targeting, non-cytotoxic, but dependent on bacterial PolI and requiring codon optimization to reduce off-target. | [89] |

| yEvolvR | S. cerevisiae | 1.24 × 10−6 | 2–3 | 12,434 | 60 bp | Wide | Error-prone E. coli DNAP | Eukaryotic host adaptation, dual gRNA multi-targeting, and full nucleotide mutation, but the bacterial PolI has limited activity in yeast. | [90] |

| targeted mutagenesis toolkit | S. cerevisiae | 1–2 × 10−3 | 1 | 10,000 | 14–20 bp | C:G→T:A, A:T→G:C | dCas9-AID*Δ, dCas9-TadA8e, dCas9-TadA8eV106W | gRNA multiplexing (Csy4-mediated) enhances efficiency, especially for proximal gRNAs. | [91] |

| CoMuTER | S. cerevisiae | 3 × 10−4 | 7–8 | 350 | 55 kbp | C:G→T:A | Cas3-base editor | The large target range is sufficient to cover the entire metabolic pathway, but only the mutation spectrum is single and the deaminase is inherently low off-target. | [92] |

| sgRNA transient expression | Aspergillus nidulans NRRL 8112 | 9.34 × 10−2 | 24 | 9,340,000 | 20 bp | C→T | CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine-base editor + combinatorial sgRNA library | Transient sgRNA expression system (pUC vector) enables easy library construction. | [93] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Yin, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, K. Advances in Strategies for In Vivo Directed Evolution of Targeted Functional Genes. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121127

Wu H, Yin L, Chen J, Wang X, Chen K. Advances in Strategies for In Vivo Directed Evolution of Targeted Functional Genes. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121127

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Hantong, Lang Yin, Jingwen Chen, Xin Wang, and Kequan Chen. 2025. "Advances in Strategies for In Vivo Directed Evolution of Targeted Functional Genes" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121127

APA StyleWu, H., Yin, L., Chen, J., Wang, X., & Chen, K. (2025). Advances in Strategies for In Vivo Directed Evolution of Targeted Functional Genes. Catalysts, 15(12), 1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121127