Abstract

This work describes the straightforward synthesis of a novel heterogeneous palladium catalyst immobilized on magnetic Janus-type silica particles coated with an amphiphilic ionic liquid (IL) layer. The material was prepared via a one-pot process wherein TEOS (tetraethoxysilane) and a bis(triethoxysilane) IL precursor are combined to form hollow shells. The IL motifs are selectively located on the outer surface of the hollow particles and serve as centers for the immobilization of palladium species on the material’s surface. The outer surface also hosts magnetic nanoparticles in close proximity to the palladium sites. Thanks to the uniform coverage of the surface with the amphiphilic IL functionality, the material exhibits a well-balanced wettability with reaction components of different polarities. The catalyst’s activity was tested in the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction of terminal acetylenes and iodobenzene derivatives in water as the solvent. The results show that the mixed palladium–iron oxide catalyst exhibits higher activity than materials containing either immobilized palladium or iron oxide alone, suggesting a synergistic effect in this reaction. Additionally, the reaction proceeds well in the absence of expensive organic ligands and commonly employed additives such as copper co-catalysts or phase transfer catalysts. Furthermore, the material was also used in the oxidative Sonogashira coupling reaction of phenylboronic acid and phenylacetylene. The catalyst can be easily separated using an external magnet and can be reused several times. The feasibility of producing diphenylacetylene on a gram scale via the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction was also investigated.

1. Introduction

Immobilizing metal complexes on insoluble supports is an effective way to improve the sustainability of catalytic reactions [,,]. Unlike homogeneous catalysts, which are often difficult to recover from reaction mixtures, heterogeneous catalysts can be easily separated by filtration, centrifugation, or magnetic attraction [,,]. This significantly reduces contamination with toxic metal impurities. Therefore, the immobilization of such catalysts on the surface of insoluble and inert supports [,] appears to be advantageous from both economic and environmental perspectives. Organic polymers [,,,] and mesoporous (organo) silica materials [,,,,,,,,,,,,,] are two major groups of support materials that have been widely used to prepare various types of immobilized catalysts, even in large amounts. Despite the advantages of immobilized catalysts, there are some limitations, such as lower reaction rates compared to homogeneous catalysts and sometimes problems with the reproducibility of the reactions. Therefore, ongoing efforts to improve the efficiency of heterogeneous catalysts are important.

Two recent and successful examples in this context are Janus-type [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] and atom-sized heterogeneous metal catalysts [,,,]. These catalysts have led to promising advances in several chemical transformations, particularly due to their adaptability to different reaction media. For example, Pickering emulsions can be effectively stabilized using only small amounts of Janus-type materials [,]. Nevertheless, despite many positive features of Janus-type materials, they still suffer from complex synthesis routes and the use of expensive reagents.

Hollow nano- and micro-architectures are another class of materials with intriguing catalytic properties []. The void space within these compounds provides versatile properties such as an improved selectivity for chemical reactions (by manipulating the porosity of the shell) or a multi-functionalization of the material with catalytically active species, as well as organic groups to adjust the surface polarity for various organic reactions. However, hollow (Janus) catalysts are generally considered difficult to prepare, and there has been limited progress towards their large-scale synthesis. We have recently reported a one-pot process for preparing Janus organic–inorganic hybrid hollow particles that avoids these drawbacks. Using a relatively simple “hollow particle strategy”, we have synthesized a series of Janus-type catalysts, which have shown high efficiency and excellent compatibility with a wide range of reaction media [,,,]. The process results in particles whose inner surface is covered with hydrophobic organosilica moieties, while their outer surface is covered with hydrophilic organosilica IL moieties []. While the crushed hollow particles exhibit interesting properties in the formation of Pickering emulsions, the robust intact, IL-functionalized hollow microstructure Janus particles themselves are promising candidates for use in heterogeneous catalysis []. Unlike conventional dense silica particles, such organic–inorganic hybrid hollow particles have a lower density and can therefore be better dispersed in the reaction medium. Due to the direct effect of the immobilized IL on the polarity and functionality of the material, it can act as a suitable partner for the electrostatic immobilization of other compounds, as an NHC (N-heterocyclic carbene) ligand for catalytically active metal sites, and/or as a stabilizer for nanoparticles on the surface [,]. Therefore, we consider hollow shell IL-functionalized Janus particles to be ideal supports for heterogeneous catalysts. However, apart from some reports on organic polymer compounds [,,], applications of other hollow Janus-type particles, such as silica-based ones, have not yet been adequately developed. Combining such a material with paramagnetic nanoparticles immobilized on its surface greatly simplifies material recovery through magnetic separation with a minimized loss of material [,,,,,,,].

The Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction is a powerful and versatile tool for C–C bond formation and has therefore found widespread application [,,,,,,]. There have been reports of Sonogashira reactions conducted in aqueous media, but these require additives, such as copper co-catalysts, toxic co-solvents, expensive and oxygen-sensitive phosphine ligands, or molecular phase transfer catalysts [,,,,,,,,,], which increase the cost of the process and have a negative environmental impact. Furthermore, using copper compounds as co-catalysts can lead to the formation of undesirable homocoupling products from the acetylene substrates via Glaser coupling [,,]. Consequently, the most widely used protocols for Sonogashira reactions still rely on homogeneous palladium catalysts and expensive ligands in organic solvents [,,,,,,,,]. To develop the Sonogashira coupling reaction in a more economical and less hazardous way, Bolm and co-workers investigated palladium-free protocols using iron [] and copper catalysts [] in the presence of diamine ligands. They demonstrated that the selection of ligands and metal precursors remarkably impacts the efficiency of the reaction. However, these systems require relatively high reaction temperatures [,] and/or longer reaction times [].

There is clear potential to further optimize this important chemical transformation in terms of sustainability. For example, Verpoort and co-workers have developed a visible-light-induced Sonogashira protocol involving a mesoporous polyazobenzene–palladium(II) composite [] that enables the coupling of a wide variety of substrates in water.

In this study, we report on the synthesis of a heterogeneous Sonogashira coupling catalyst consisting of immobilized palladium species on hollow and magnetic Janus-type silica particles. Not only do magnetic iron oxide particles facilitate an easy catalyst separation, they also enhance the catalytic activity of palladium, as previously reported in the literature [,,]. Despite the cooperativity between the iron oxide particles and the palladium species during the reaction, the unique properties of the hollow Janus-type silica particles are also crucial for achieving high catalytic activity in water. This is the first time that a heterogeneous catalyst has been used for an oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction—an alternative to the classical Sonogashira reaction—between phenylacetylene and phenylboronic acid.

2. Results

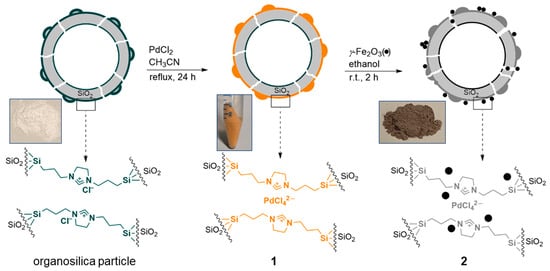

The preparation of catalyst 2 is shown schematically in Figure 1. First, hollow Janus-type silica spheres with a uniformly distributed imidazolinium-based IL layer on their external surface were prepared []. [PdCl4]2− was then immobilized on these particles by refluxing them with PdCl2 in an acetonitrile solution [], resulting in the formation of material 1. A stable anchoring of the surface functionalities was achieved through a combination of covalent bonds (the immobilized IL ligand) and electrostatic interactions (the [PdCl4]2− immobilization). The latter also ensured good dispersion of the palladium on the particles’ outer surface. Material 1 was dispersed in ethanol and added to an ethanolic suspension of iron oxide nanoparticles prepared by a well-established method that has been published by our group some years ago []. Finally, the solvent was evaporated and the material was dried to yield catalyst 2 as a grey powder (see the Section 3 for details).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of the hollow mesoporous silica Janus catalyst 2 modified with IL groups, palladium (II) species, and γ-Fe2O3 (•) nanoparticles.

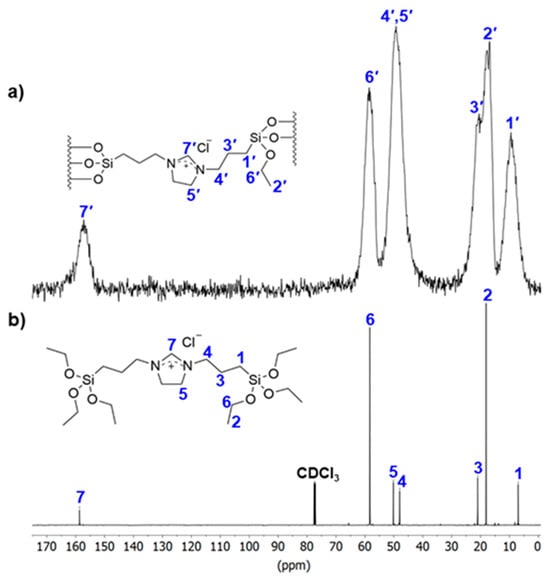

Comparing the solid-state CP-MAS 13C NMR spectrum of material 1 with the high-resolution 13C NMR spectrum of the IL precursor (Figure 2) shows that the immobilized organic ligand remains stable during preparation. All resonances observed in the solid-state spectrum are also present in the corresponding high-resolution spectrum. Notably, a single resonance at around 160 ppm (7 and 7′) indicates the preservation of the imidazolinium ring. The relative intensities of the ethoxy resonances have decreased due to the condensation reactions occurring between the IL precursor and the surface. As expected, based on the reaction conditions, the solid-state 13C NMR spectrum shows no indication of N-heterocyclic carbene species formation. In the solid-state 29Si CP-MAS NMR spectrum of material 1 (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information), the signals at about −102 and −111 ppm are assigned to Si(OSi)3OH (Q3) and Si(OSi)4 (Q4) species in the silica material framework, while additional signals at about −55 and −60 ppm are assigned to C-Si(OSi)2OH (T2) and C-Si(OSi)3 (T3) species, demonstrating the preservation of the C-Si bonds of the linker units.

Figure 2.

A comparison of (a) the solid-state CP-MAS 13C NMR spectrum of material 1 and (b) the high-resolution 13C NMR spectrum of the IL precursor recorded in CDCl3.

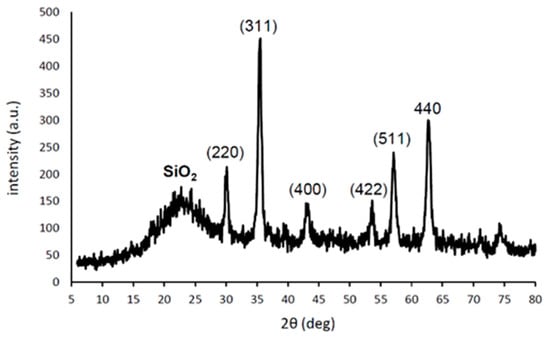

Figure 3 shows the powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern of catalyst 2. This demonstrates the crystalline nature of the iron oxide particles, which remain unchanged after their immobilization on the surface of the Janus hollow silica particles. The positions and the relative intensities of all the iron oxide particle reflections (mainly γ-Fe2O3) are in perfect agreement with previous reports [,]. More intense and narrower reflections were observed here, corresponding to somewhat larger crystallites. The diameter of the iron oxide crystallites was calculated to be about 12.5 nm using the Debye–Scherrer equation. The broad reflection around 2θ = 23° is due to amorphous silica [].

Figure 3.

PXRD pattern of catalyst 2; all reflections are assigned to γ-Fe2O3 unless otherwise stated.

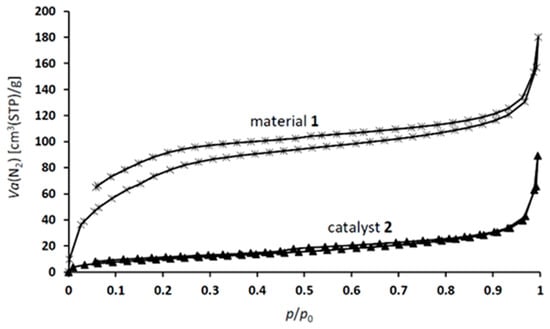

The N2 physisorption isotherms of material 1 exhibit type-IV profiles with the characteristic H4-type hysteresis loop of mesoporous materials. Catalyst 2 shows a similar isotherm with minor deviations (Figure 4) []. Based on these findings, the specific surface area (SBET) and pore volume of material 1 were calculated to be 220 m2·g−1 and 0.24 cm3·g−1, respectively. For catalyst 2, these values are reduced to 35 m2·g−1 and 0.1 cm3·g−1, respectively.

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of material 1 and catalyst 2.

According to the BJH data, the average pore diameter of material 1 is 2.6 nm, while that of catalyst 2 is 9.1 nm. The decrease in the specific surface area and the pore volume, and the simultaneous increase in the average pore diameter can be explained by the preferential occupation of some small-diameter pores (or pore entrances) by nanosized iron oxide nanoparticles (see Figure 1). Accordingly, the observed “average” pore diameter in catalyst 2 is higher than that in material 1.

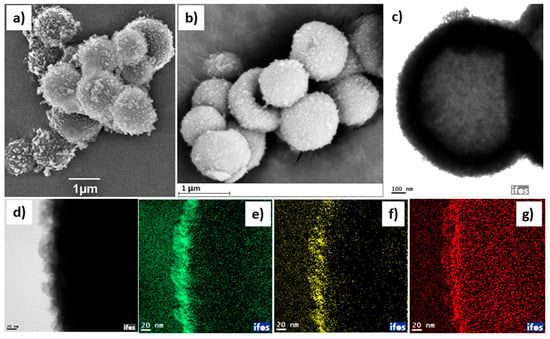

The morphology of the prepared materials was investigated using SEM analysis. Figure S2 (in the Supporting Information) shows that the pristine hollow silica particles with no IL functionalities have a smooth surface, whereas the outer surface of material 1 (Figure 5a) and catalyst 2 (Figure 5b) is rough, indicating the deposition of the IL on the hollow Janus-type silica particles [].

Figure 5.

SEM images of (a) material 1 and (b) catalyst 2. (c) TEM image of catalyst 2. (d) TEM elemental mapping of the selected area of the outer surface of catalyst 2 for (e) carbon (C), (f) chlorine (Cl), and (g) iron (Fe). Scale bars: (a,b) 1 μm, (c) 100 nm, and (d–g) 20 nm.

It is worth noting that the iron oxide nanoparticles are too small to be detected by the SEM analysis. Details of the elemental composition of the surface of catalyst 2 were obtained using EDX elemental mapping in combination with the SEM analysis (see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). The EDX analysis reveals the presence of all the constituent elements of the IL as well as of the immobilized metal-derived species. However, the corresponding iron peak has a relatively low intensity in this analysis. One possible explanation for this observation is the penetration of the dispersed nanosized iron oxide into the interstices of the uneven surface of the catalyst, which hinders proper detection by “surface scanning” during EDX analysis. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) elemental mapping images reveal the catalyst’s hollow geometry (Figure 5c), displaying the distribution of the selected metallic and non-metallic elements across its surface. The amount of palladium is too low to be detected here. However, elemental analysis using atomic absorption spectroscopy revealed the presence of 1.2 wt.% of palladium and 10 wt.% of iron in catalyst 2.

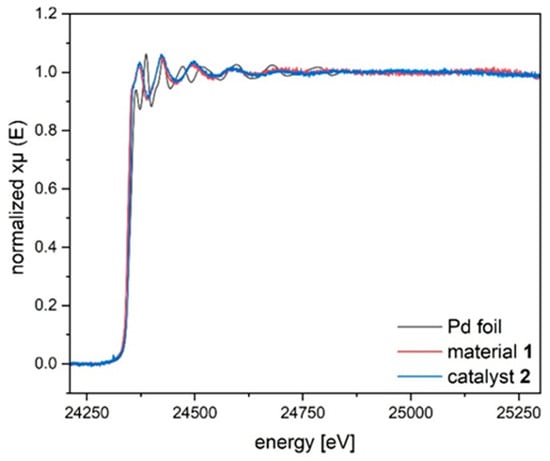

Further structural information on the palladium species, present on material 1 and catalyst 2, was obtained by recording X-ray absorption spectra at the palladium K edge (24.350 keV). The samples were prepared as pellets and measured at room temperature in transmission mode. Compared to the Pd foil reference, the increased white line intensities already indicate that palladium is present in an oxidized state for both materials (Figure 6). Furthermore, the oscillatory patterns of both materials are almost identical, suggesting that the local environments around the palladium centres are very similar.

Figure 6.

Normalized X-ray absorption spectra at the Pd K-edge for material 1 and catalyst 2 compared to the Pd reference foil.

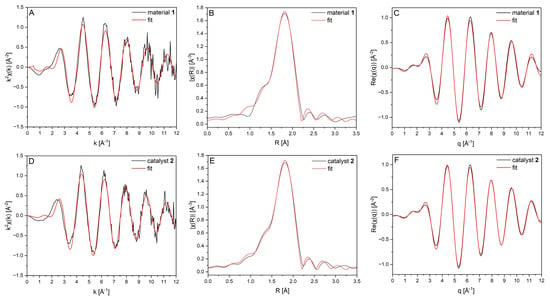

To gain a better understanding, the EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure) data were fitted using a single scattering path of Pd–Cl based on a PdCl42− model. Figure 7 shows the k-, R-, and q-space along with the corresponding fit results for both materials. The data confirm that the EXAFS features are nearly identical, indicating that there are no significant structural differences in the direct Pd environment of the two materials. The coordination number (N) for the Pd–Cl path was determined to be 3.79 ± 0.26 for material 1 and 3.84 ± 0.21 for material 2 (Table 1), which is consistent with the square planar coordination in PdCl42−. The fitted Pd–Cl interatomic distances (Table 1) were 2.31 ± 0.001 Å for material 1 and 2.31 ± 0.005 Å for material 2, respectively. These values match the reference value of 2.31 Å. Including an additional Pd–Pd path did not significantly improve the fit: This confirmed the absence of metallic palladium clusters or nanoparticles in both samples. In summary, these results suggest that the coordination sphere of material 1 remained unchanged upon conversion into material 2.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the experimentally obtained spectra at the Pd K-edge and the corresponding best fit results (red) of material 1 (black, (A–C)) and catalyst 2 (black, (D–F)) based on a PdCl42− model. EXAFS spectra (A,D), Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra (B,E), and the back transformation thereof (C,F).

Table 1.

Coordination numbers and experimental interatomic distances for materials 1 and catalyst 2 by EXAFS analysis, compared to expected distances for a PdCl42− fit model.

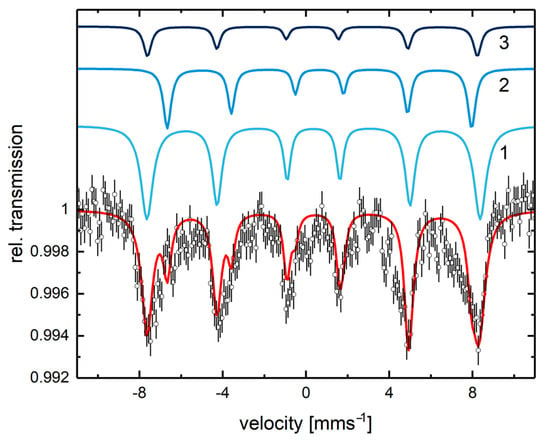

Mössbauer spectroscopy was used as a complementary method to elucidate the nature of the iron sites in the immobilized iron nanoparticles (without palladium, see Figure S4 and Table S1 in the Supporting Information) and in catalyst 2 (Figure 8). The results showed no difference in the signals of the two samples. As magnetically split Mössbauer spectra were observed at room temperature with no superparamagnetic doublets, the iron oxide nanoparticles must be at least approximately 15 nm in diameter. This is slightly larger, but still consistent, with the result obtained from the XRD analysis (12.5 nm, calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation). The analysis of the Mössbauer spectrum using three magnetic sextets indicates that the composition of the iron oxide particles in catalyst 2 is approximately 62% maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) and 38% magnetite (Fe2+Fe3+2O4) [].

Figure 8.

Mössbauer spectrum of catalyst 2 recorded at room temperature. The red line is the sum of the components 1, 2, and 3. Component 1 has an isomer shift of = 0.37 mms−1, no quadrupole splitting, and a magnetic hyperfine field of Bhf = 49.6 T. This component dominates the spectrum with a relative area of 62%. The line widths of the symmetric sextet are 0.80, 0.60, and 0.45 mms−1. Component 2 displays an isomer shift of = 0.65 mms−1 and a magnetic hyperfine field of Bhf = 45.3 T and accounts for 23% of the simulated spectrum. Line widths have been taken as 0.50, 0.45, and 0.40 mms−1. Component 3 has = 0.31 mms−1, Bhf = 49.1 T, and a relative area of 11% with taken as 0.50, 0.45, and 0.40 mms−1. These parameters are typical for magnetite with components 2 and 3 representing its B and A sites, respectively.

Having clarified the detailed structural identity, we investigated the activity of catalyst 2 in the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction in water. To test our hypothesis regarding the presence of cooperativity between iron and palladium, we compared the activities of catalyst 2, material 1, and a sample containing pure iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles immobilized on hollow silica particles for the coupling of phenylacetylene and iodobenzene (see Table 2, entries 1–3). The best result was obtained with the bimetallic catalyst 2 (Table 2, entry 1), which showed almost complete conversion of the starting material. The reaction with the non-magnetic material 1 proceeded with lower activity (Table 2, entry 2), and no significant conversion was observed when immobilized iron oxide on hollow silica nanoparticles was used as the catalyst. It is worth noting that the use of α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles as a catalyst for the Sonogashira coupling reaction in ethylene glycol at 150 °C has previously been reported in the literature [].

Table 2.

Comparison of the activity of various catalysts in the Sonogashira coupling of iodobenzene with phenylacetylene in water.

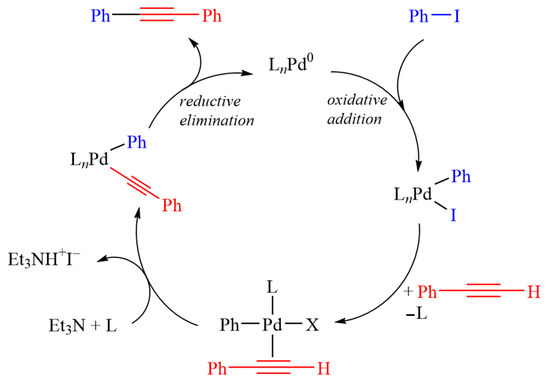

Based on EXAFS and Mössbauer spectroscopy, there is no direct interaction between palladium and iron. Therefore, the nature of the observed synergy in catalytic activity is presumably not related to the presence of bimetallic Pd–Fe species. However, the active palladium and iron species may cooperate separately during the reaction, although the exact mechanism of this phenomenon is yet unclear. One plausible explanation for the reaction mechanism is that iron sites, present around oxygen vacancies of the iron oxide nanoparticles [], assist in activating iodobenzene [], and consequently accelerate the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction [,,,]. A general proposed reaction mechanism is shown in Figure 9. Mechanistically, the copper-free Sonogashira coupling proceeds through the same oxidative addition, transmetalation, and reductive elimination steps as the traditional version, but the terminal alkyne is directly activated by palladium rather than by copper.

Figure 9.

A general proposed mechanism for the Sonogashira coupling reaction.

Next, commercial, dense silica gel particles were modified with the IL, palladium, and γ-Fe2O3 as described above and used as the catalyst. We found that the yield of diphenylacetylene was significantly lower (Table 2, entry 4), which demonstrates the crucial role of the hollow material architecture of catalyst 2 in the reaction. Crushed particles of catalyst 2 (i.e., Janus nanosheets, Table 2, entry 5) do not exhibit superior activity for the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction. In a final experiment, we used Janus nanosheets with hydrophobic bridging ethyl groups on the inner surface and IL/Pd-γ-Fe2O3 functionalities on the outer surface. This material is more hydrophobic on the inner surface than catalyst 2, but despite being more complicated to synthesize, it only slightly improved the yield of the coupling product by a few percent (Table 2, entry 6). Further attempts to improve the reaction outcome focused on varying the base. K2CO3 (2 equiv.) and pyrrolidine (3 equiv.) gave 14% and 67% of diphenylacetylene, respectively. Increasing the reaction temperature to 85 °C reduced the yield of diphenylacetylene to 74%, probably due to the formation of some by-products. Furthermore, no improvement in yield was obtained by carrying out the reaction under an inert nitrogen atmosphere (86%).

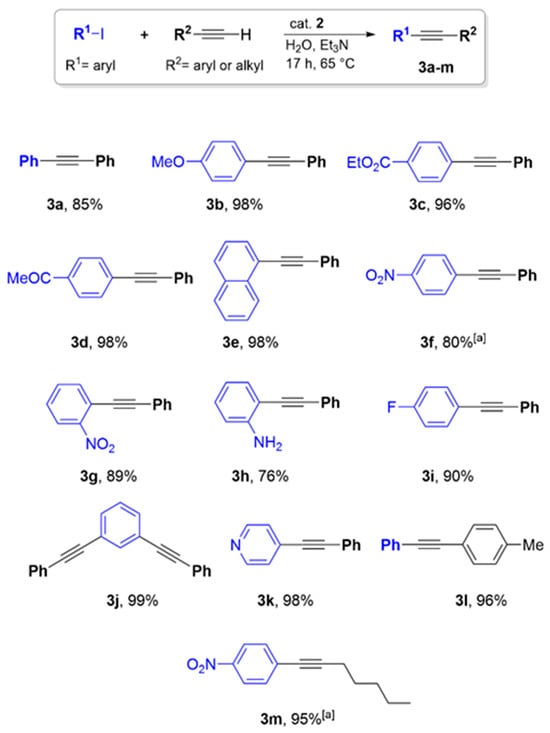

Figure 10 summarizes the results of our investigation into the scope of catalyst 2 in C(sp2)–C(sp) bond formation through the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction in water. A wide range of substrates could successfully be converted to the corresponding products with high yields, including aryl iodides featuring electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups, even in the ortho position of the phenyl ring. Additionally, the reaction of 1,3-diiodobenzene and the heterocyclic compound 4-iodopyridine with phenylacetylene afforded the corresponding products in excellent yields. Reactions of iodobenzene with the substituted phenylacetylene, 4-ethynyltoluene, and with the generally less reactive aliphatic compound 1-heptyne gave yields of 96% and 95%, respectively. Attempts to use bromobenzenes and phenyltriflate as the substrates were unsuccessful, due to the significant difference in activity between iodo- and bromobenzene compounds in this reaction.

Figure 10.

Scope of the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction of various substrates over catalyst 2 in water. Reaction conditions: Aryl iodide (1 mmol), acetylene derivatives (1 mmol), catalyst 2 (30 mg, containing 1.2 wt.% Pd), Et3N (3 mmol), and H2O (5 mL). [a] Yield determined by 1H NMR since the product could not be separated from the unreacted starting material. For isolated yields, a ±5% deviation can be considered.

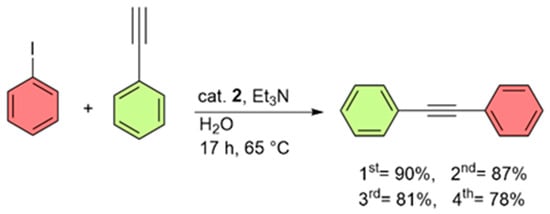

Exemplarily, catalyst recovery experiments were carried out for the Sonogashira cross-coupling of iodobenzene and phenylacetylene in water (Figure 11). At the end of each reaction cycle, catalyst 2 could easily be separated using an external magnet and reused for four runs without significant loss of activity. Encouraged by the facile magnetic separation of catalyst 2, we investigated a gram-scale synthesis of diphenylacetylene using 20 mmol of each substrate. The result showed a yield of 96% (3.43 g of diphenylacetylene, see Figure S5 in the Supporting Information).

Figure 11.

Recycling of catalyst 2 for the Sonogashira cross-coupling of iodobenzene and phenylacetylene; yields from 1st to 4th run are given; reaction conditions: iodobenzene (4 mmol), phenylacetylene (4 mmol), catalyst 2 (120 mg, containing 1.2 wt.% Pd), Et3N (12 mmol), and H2O (20 mL). For isolated yields, a ±5% deviation can be considered.

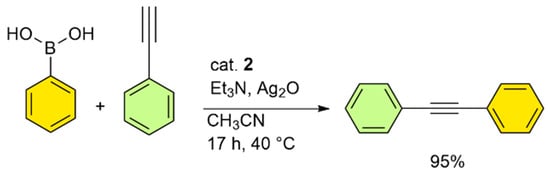

It should be noted that an equimolar ratio of the starting materials was used in all cases, and an excess of one of the reactants was not necessary here. The scope and efficiency of catalyst 2 were further studied for an oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction. Here, two nucleophiles are coupled in the presence of metallic catalysts [,,,,,,]. For the oxidative Sonogashira reaction, mainly homogeneous gold catalysts are used in combination with phosphine ligands [,,,] or Selectfluor® [,,] to oxidize gold(I) to gold(III) species. As an alternative, a method based on Pd(OAc)2 in combination with Ag2O has been published, but this was only applicable to electron-poor terminal alkynes [].

Our initial attempts to react phenylboronic acid and phenylacetylene in an aqueous solution, as described in Figure 10, gave no noticeable product, even when 1 equiv. of silver(I) oxide (Ag2O) was used. Interestingly, the reaction proceeded efficiently in acetonitrile under mild thermal conditions, yielding 95% of diphenylacetylene (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling of phenylboronic acid and phenylacetylene with catalyst 2. Reaction conditions: Phenylboronic acid (1.2 mmol), phenylacetylene (1 mmol), catalyst 2 (30 mg, containing 1.2 wt.% Pd), Et3N (3 mmol), Ag2O (1.5 mmol), CH3CN (5 mL). For isolated yields, a ±5% deviation can be considered.

The efficiency of catalyst 2 in the oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction is compared with results published in the literature (Table 3). Unlike the classical Sonogashira reaction, the oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling has not yet been well developed. Homogeneous gold complexes, such as the very expensive JohnPhos AuCl (Table 3, entry 5), are often employed in this reaction. It was found that catalyst 2 is highly active compared to other systems. The other advantages of catalyst 2 are a simple protocol and a low reaction temperature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a magnetically separable heterogeneous palladium catalyst being used for the oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction.

Table 3.

Comparison of the oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling catalyzed by catalyst 2 with literature results.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Information and Instruments

All chemicals and solvents were purchased from chemical suppliers and used without further purification. Dry pentane was used to purify the ionic liquid precursor. Solid-state 13C and 29Si CP-MAS NMR spectra were measured on a 500 MHz BRUKER Avance III spectrometer (BRUKER BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a 4 mm tube under cross-polarization conditions and a spinning frequency of 11,000 Hz for both carbon and silicon nuclei and with scan numbers of 20,000 (13C) and 2500 (29Si). High-resolution 1H and 13C NMR analyses were carried out on 400 MHz BRUKER DPX spectrometers. The SEM analysis was performed on a JSM-6490LA JEOL instrument (JEOL Germany GmbH, Freising, Germany) as well as a Zeiss Supra 40 VP instrument (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). EDX was performed using a Thermo Scientific Noran System Six (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) with a resolution of 130 eV. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were obtained by using a JEOL 2010 device in analytical design (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a LaB6 cathode, operating at 197 kV. The instrument was equipped with a Gatan imaging filter “863 GIF Tridiem” (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). TEM imaging was performed in the energy-filtered mode (EFTEM). The “Digital Micrograph 3” software (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) was used for acquisition and analysis of TEM images. Elemental analyses were performed with an Elementar Vario Micro Cube device (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Nitrogen physisorption measurements were performed on a BELSORP MAX from Microtrac Retzsch (Microtrac Retzsch GmbH, Haan, Germany) with sample activation in vacuum for 20 h at 130 °C prior to the measurement. Data evaluation was carried out using the BEL Master version 7.3.2.0 software. XRD analysis was performed with a Siemens D 5005 powder diffractometer with CuKα radiation in the 2θ range from 4° to 80° with a step width of 2θ = 0.04° and an accumulation time of 10 s for step 1. The iron oxide nanoparticles were prepared according to our established protocol []. The bis(triethoxysilane)-containing ionic liquid (IL) precursor was prepared according to our previously described method []. XAS experiments were performed at the PETRA III extension beamline P65 at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, Germany, with an energy range of 4–44 keV. Measurements were performed at the Pd K-edge (24,350 eV) using a Si(311) C-type double crystal monochromator and a beam current of 100 mA with a ring energy of 6.08 GeV. The samples were placed in glass capillaries without dilution, and spectra were recorded as continuous scans in both fluorescence and transmission modes at ambient temperature and pressure in the range of −150 to 1000 eV around the edge in 180 s. Evaluation was performed using the Demeter software package (Institut Laue-Langevin, Grenoble, France) on the fluorescence data of the individual samples. Mössbauer spectra were recorded in transmission mode at room temperature with no external magnetic field. The source of Mössbauer radiation was a radioactive 57Co electrodeposited in a Rh matrix with an activity of 56 MBq at the time of measurements. The source was mounted on a Mössbauer drive performing the constant acceleration mode. Γ-Quanta transmitted through the sample were detected with a proportional counter connected to a multichannel analyzer using 512 channels in the time-scale mode. All devices were from WissEl GmbH (Wissenschaftliche Elektronik GmbH, Starnberg, Germany). The powder samples were prepared in a sample holder 3D-printed using an optically transparent copolyester (Ultimaker CPE+-Filament). The software used for calculating the Mössbauer spectra was a Microsoft Excel plug-in, vinda []. Magnetic sextets with Lorentzian line shape were used for the analysis. The line widths are given as full widths at half maximum (FWHM). The quadrupole splitting (QS) was taken as zero in all cases.

3.2. Synthesis of the Functionalized Silica Particles

0.644 g (1.77 mmol) of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 215.6 mL of H2O, and 0.45 mL of aqueous ammonia solution (25% by weight) were added to a 500 mL flask, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. The second flask, containing a solution of 0.5 mL of n-decane and 102 g of ethanol, was then added to the first flask. This mixture was stirred for 10 min and then was placed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min at 35 °C. Next, 19.2 mmol (4.00 g, 4.26 mL) of tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) was added to this solution, and the mixture was stirred at 700 rpm at 35 °C for 60 min. Then, 2 mmol (1.03 g) of the IL derivative was diluted in 1 mL of ethanol, and the solution was added dropwise to this mixture, while continuing the stirring for 23 h at the same temperature. At the end of the reaction, the white solid was collected by centrifugation (2 min at 5000 rpm) and was washed several times with ethanol. The CTAB surfactant was removed according to the previously reported procedure [,], and the material was then dried in an oven at 80 °C for 18 h to yield 2.06 g of a pale-yellow powder. Elemental analysis: C: 11.14%, H: 2.93%, N: 2.22%. For the crushed particles (Table 1, entry 5), the material was crushed according to the procedure described in ref. [].

3.3. Procedure for the Preparation of Material 1 []

1.0 g of hollow silica particles was dispersed in 40 mL of acetonitrile, and the suspension was placed in an ultrasonic bath at room temperature for 10 min. A solution of PdCl2 (80 mg) in acetonitrile (40 mL) was then added dropwise to the dispersed hollow particle suspension. The mixture was stirred for 24 h at the reflux temperature (82 °C). At the end of the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, then the particles were separated by centrifuge, washed with acetonitrile (4 × 10 mL), and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 18 h to yield 1.0 g of a light brown powder. Elemental analysis: C: 11.19%, H: 3.51%, N: 2.00%.

3.4. Synthesis of Catalyst 2

0.50 g of the hollow silica-Pd material 1 was dispersed in 30 mL of ethanol, and the suspension was placed in an ultrasonic bath at room temperature for 10 min. Then, 0.15 g of the maghemite (γ-Fe2O3) was completely dispersed in 20 mL of ethanol under ultrasonic conditions. The ethanolic suspension of γ-Fe2O3 was then added dropwise to the stirred suspension of the silica–Pd material in ethanol. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h, followed by evaporation of the solvent in a rotary evaporator to yield 0.64 g of dry gray powder. Elemental analysis: C: 13.10%, H: 2.51%, N: 1.62%, Pd: 1.19 wt.%, and Fe: 10.04 wt.%.

3.5. Procedure for the Sonogashira Cross-Coupling Reaction

In a 10 mL flask, 30 mg of catalyst 2 was dispersed in 5 mL of H2O and sonicated for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath. Then, 1 mmol aryl iodide, 3 mmol (0.42 mL, 0.3 g) triethylamine, and 1 mmol of the acetylene derivative were added to the flask, and the resulting mixture was stirred for the appropriate time and at the given temperature. At the end of the reaction, it was cooled to room temperature, extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL), and the combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was then removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using n-hexane/ethyl acetate as the eluent to yield the pure product.

3.6. Procedure for the Oxidative Sonogashira Cross-Coupling Reaction

In a 10 mL flask, 30 mg of catalyst 2 was dispersed in 5 mL of CH3CN and then sonicated for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath. Then, 1 mmol (0.1 g) of phenylacetylene, 1.2 mmol (146 mg) of phenylboronic acid, 1.2 mmol (348 mg) of Ag2O, and 3 mmol (0.42 mL, 0.3 g) of triethylamine were added to the flask, and the resulting mixture was stirred for 17 h at 40 °C. At the end of the reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. Then, the solvent was removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using n-hexane as the eluent to give the pure product.

3.7. Recycling Experiment

In a 25 mL flask, 120 mg of catalyst 2 was dispersed in 20 mL of H2O and sonicated for 10 min in an ultrasonic bath. Then, 4 mmol of iodobenzene, 12 mmol of triethylamine, and 4 mmol of the acetylene derivative were added to the flask, and the resulting mixture was stirred at the appropriate time and temperature. At the end of each reaction cycle, the flask was cooled to room temperature. The catalyst was then isolated in the flask by using an external magnet. The solution was decanted into a 100 mL flask. The remaining catalyst was further washed with Et2O (3 × 20 mL), and the combined organic solution was dried over anhydrous MgSO4. The solvent was then removed under vacuum, and the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography using n-hexane/ethyl acetate as eluent to give the pure product.

4. Conclusions

This study describes the synthesis of a magnetically separable palladium catalyst, decorated on Janus-type hollow silica particles, for the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction. The catalyst exhibits high activity, which can be attributed to the following material properties: (i) a certain degree of cooperativity between the palladium and iron oxide sites in the reaction, (ii) a uniform and site-isolated distribution of palladium within the ionic liquid layer that prevents agglomeration of the active species, (iii) the unique structure of the hollow particles, particularly their low density that promotes efficient dispersion within the reaction mixture, and (iv) the accessibility of the active species on the outer surface of the hollow silica particles that exhibit well-balanced surface wettability. As discussed, the anisotropic “Janus architecture” does not significantly contribute to achieving high catalytic activity.

Unlike previous reports, which required the Sonogashira reaction to be carried out under anhydrous conditions [,] or in an inert atmosphere [,,], our catalytic system is highly compatible with both water and air and can operate at near-ambient temperatures. The catalyst also exhibits exceptional activity in the oxidative Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction, opening up new avenues for the development of cost-effective, eco-friendly heterogeneous catalysts for this process. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a catalytic application of periodic mesoporous silica Janus particles in a carbon-carbon bond formation reaction.

This work provides valuable insights into the rational design of water-compatible, bimetallic, heterogeneous catalysts. These catalysts offer additional benefits such as ease of separation and potential for large-scale synthesis. Furthermore, it promotes the development of efficient catalytic systems by facilitating synergy between active species in Janus-type materials. Employing this type of catalyst in various coupling reactions, as well as tuning its activity toward less reactive substrates, emerges as one of the major upcoming challenges of this work. Further topological surface analyses of the catalyst are currently being conducted in our research group.

Supplementary Materials

The supporting information for this article can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/catal15121123/s1. Figure S1. Solid-state 29Si CP-MAS NMR spectrum of material 1; Figure S2. The SEM image of the pristine hollow silica particles with no IL functionalities; Figure S3. EDX elemental mapping of catalyst 2 in combination with the SEM analysis; Figure S4. HR-TEM elemental mapping of catalyst 2; Figure S5. HR-TEM images of compound 2; Figure S6. HR-TEM images of compound 2; selected regions for elemental mapping; Figure S7. Mössbauer spectrum of material 1. The solid lines are simulations with the parameters given in Table S1; Table S1: Mössbauer parameters as obtained from the analysis of the Mössbauer spectrum shown in Figures S5 and S6; Figure S8. Separation of the catalyst using an external magnet. Small amounts of the catalyst, which are on the flask are also washed with distilled water during the catalyst collection; Figure S9. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S10. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S11. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S12. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S13. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S14. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S15. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S16. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S17. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S18. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S19. 1H NMR in CDCl3 (mixture with unreacted 1-Iodo-4-nitrobenzene); Figure S20. 13C NMR in CDCl3 (mixture with unreacted 1-Iodo-4-nitrobenzene); Figure S21. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S22. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S23. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S24. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S25. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S26. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S27. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S28. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S29. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S30. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S31. 1H NMR in CDCl3; Figure S32. 13C NMR in CDCl3; Figure S33. 1H NMR in CDCl3 (mixture with unreacted 1-iodo-4-nitrobenzene); Figure S34. 13C NMR in CDCl3 (mixture with unreacted 1-iodo-4-nitrobenzene).

Author Contributions

M.V.; conceptualization and data interpretation, preparation of the catalyst, reaction optimization, separation and purification of the products, drawings, writing the original draft, preparation of the Supporting Information, F.R.; reaction setup, separation and purification, review and editing the manuscript, X.Q.; preparation of the catalyst, optimization, M.A.M.T., P.H. and V.S.; Mössbauer spectroscopy analysis and the relevant data interpretations, A.O.; N2 adsorption–desorption analysis, W.K.; N2 adsorption–desorption analysis, XRD and XAS analysis, A.D. and J.L.; TEM analysis; S.S.; XAS analysis, W.R.T. supervision, review and editing the manuscript, data interpretation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung (project “Smart batch processes”) and the research initiative NanoKat. Prof. Fatemeh Rajabi thanks the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for financial support. DESY (Hamburg, Germany) is acknowledged for providing beamtime to perform X-ray spectroscopy.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the support of Marc Hein and Barbara Güttler from Leibniz-Institut für Verbundwerkstoffe (Kaiserslautern) for the SEM and EDX analyses. Julia Leandro (RPTU) is acknowledged for carrying out the XRD analysis. We acknowledge DESY (Hamburg), a member of the Helmholtz Association HGF, for the provision of experimental facilities at Petra III, and we would like to thank Edmund Welter for assistance in using beamline P65 (proposal I-20231314).

Conflicts of Interest

Anna Demchenko, Johannes L’huillier were employed by the company Institut für Oberflächen-und Schichttechnik IFOS GmbH, Trippstadter-Str.120, 67663 Kaiserslautern, Germany. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Dedication

In memory of our former laboratory colleague, Dr. Sarah Reeb, who passed away far too soon on 3 June 2025.

References

- Shelke, Y.G.; Yashmeen, A.; Gholap, A.V.A.; Gharpure, S.J.; Kapdi, A.R. Homogeneous Catalysis: A Powerful Technology for the Modification of Important Biomolecules. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 2991–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, T.A.; Dabrowski, J.A.; Gagné, M.R. Homogeneous Catalysis for the Production of Low-Volume, High-Value Chemicals from Biomass. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Daw, P.; Milstein, D. Homogeneous Catalysis for Sustainable Energy: Hydrogen and Methanol Economies, Fuels from Biomass, and Related Topics. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 385–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shylesh, S.; Schünemann, V.; Thiel, W.R. Magnetically Separable Nanocatalysts: Bridges Between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3428–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shylesh, S.; Wang, L.; Demeshko, S.; Thiel, W.R. Facile Synthesis of Mesoporous Magnetic Nanocomposites and Their Catalytic Application in Carbon–Carbon Coupling Reactions. ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 1543–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shylesh, S.; Wang, L.; Thiel, W.R. Palladium(II)-Phosphine Complexes Supported on Magnetic Nanoparticles: Filtration-Free, Recyclable Catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, E.; Schneller, T.; Auer, F.; Mayer, H.A. Chemistry in Interphases—A New Approach to Organometallic Syntheses and Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2154–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Thiel, W.R. Janus Interphase Catalysts for Interfacial Organic Reactions. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 315, 113735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaglia, M.; Puglisi, A.; Cozzi, F. Polymer-Supported Organic Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3401–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, I.C.; Hammond, C.; Buchard, A. Polymer-supported metal catalysts for the heterogeneous polymerisation of lactones. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 5894–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Motahharifar, N.; Ghorbannezhad, F.; Bidgolia, N.S.S.; Baran, T.; Varma, R.S. Recent advances in polymer supported palladium complexes as (nano)catalysts for Sonogashira coupling reaction. Mol. Catal. 2020, 480, 110645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Vafaeezadeh, M.; Akhavan, P.F. N-Heterocyclic Carbene–Pd Polymers as Reusable Precatalysts for Cyanation and Ullmann Homocoupling of Aryl Halides: The Role of Solvent in Product Distribution. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Recent advanced development of metal-loaded mesoporous organosilicas as catalytic nanoreactors. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 6827–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Hashemi, M.M. Efficient fatty acid esterification using silica supported Brønsted acidic ionic liquid catalyst: Experimental study and DFT modeling. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 250, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Vafaeezadeh, M. SBA-15 functionalized sulfonic acid containing a confined hydrophobic and acidic ionic liquid: A highly efficient catalyst for solvent-free thioacetalization of carbonyl compounds at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 23207–23211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Vafaeezadeh, M. SBA-15-functionalized sulfonic acid confined acidic ionic liquid: A powerful and water-tolerant catalyst for solvent-free esterifications. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3327–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, U.; Brunel, D.; Corma, A. Catalysis using multifunctional organosiliceous hybrid materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 4083–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corma, A.; Das, D.; García, H.; Leyva, A. A periodic mesoporous organosilica containing a carbapalladacycle complex as heterogeneous catalyst for Suzuki cross-coupling. J. Catal. 2005, 229, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleizão, C.; Gigante, B.; Das, D.; Álvaro, M.; Garcia, H.; Corma, A. Periodic mesoporous organosilica incorporating a catalytically active vanadyl Schiff base complex in the framework. J. Catal. 2004, 223, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Williams, C.T. Recent advances in the applications of mesoporous silica in heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 5765–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschmeyer, T.; Rey, F.; Sankar, G.; Thomas, J.M. Heterogeneous catalysts obtained by grafting metallocene complexes onto mesoporous silica. Nature 1995, 378, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minakata, S.; Komatsu, M. Organic Reactions on Silica in Water. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Ganji, N.; Pourshiani, O.; Thiel, W.R. Periodic mesoporous organosilicas (PMOs): From synthesis strategies to applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 125, 100896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Seifert, A.; Thiel, W.R. Mesoporous MCM-41 Materials Modified with Oxodiperoxo Molybdenum Complexes: Efficient Catalysts for the Epoxidation of Cyclooctene. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 2174–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shylesh, S.; Wagner, A.; Seifert, A.; Ernst, S.; Thiel, W.R. Cooperative Acid–Base Effects with Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles: Applications in Carbon–Carbon Bond-Formation Reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 7052–7062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shylesh, S.; Wagener, A.; Seifert, A.; Ernst, S.; Thiel, W.R. Mesoporous Organosilicas with Acidic Frameworks and Basic Sites in the Pores: An Approach to Cooperative Catalytic Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Thiel, W.R. Task-Specific Janus Materials in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202206403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Wan, C.; Wang, M.; Lin, Z. Strictly Biphasic Soft and Hard Janus Structures: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5524–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Lin, Z. Stimuli-responsive Janus mesoporous nanosheets towards robust interfacial emulsification and catalysis. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 3242–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, Y.; Deng, R.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Z. Recent advances in scalable synthesis and performance of Janus polymer/inorganic nanocomposites. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 124, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, J.; Tang, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Tan, R. Thermo-Switchable Pickering Emulsion Stabilized by Smart Janus Nanosheets for Controllable Interfacial Catalysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 14144–14157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, S.; Pi, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Tan, R. Ionic liquid-functionalized amphiphilic Janus nanosheets afford highly accessible interface for asymmetric catalysis in water. J. Catal. 2021, 395, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tang, Z.; Fu, W.; Wang, W.; Tan, R.; Yin, D. An ionic liquid-functionalized amphiphilic Janus material as a Pickering interfacial catalyst for asymmetric sulfoxidation in water. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Breuninger, P.; Lösch, P.; Wilhelm, C.; Ernst, S.; Antonyuk, S.; Thiel, W.R. Janus Interphase Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Materials: Novel Water-Friendly Heterogeneous Catalysts. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2304–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Wilhelm, C.; Breuninger, P.; Ernst, S.; Antonyuk, S.; Thiel, W.R. A Janus-type Heterogeneous Surfactant for Adipic Acid Synthesis. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2695–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Shen, K.; Qu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, Z. Inorganic Janus Nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2379–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, N.; Sun, D.; Yang, Z. Janus Composite Particles and Interfacial Catalysis Thereby. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2023, 44, 2300280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Hou, Y.; Meng, Q.B.; Zhang, G.; Liang, F.; Song, X. Heteropoly acids-functionalized Janus particles as catalytic emulsifier for heterogeneous acylation in flow ionic liquid-in-oil Pickering emulsion. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 570, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, F. Preparation of Janus-type catalysts and their catalytic performance at emulsion interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 490, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Saynisch, R.; Lösch, A.; Kleist, W.; Thiel, W.R. Fast and Selective Aqueous-Phase Oxidation of Styrene to Acetophenone Using a Mesoporous Janus-Type Palladium Catalyst. Molecules 2021, 26, 6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Schaumloffel, J.; Lösch, A.; De Cuyper, A.; Thiel, W.R. Dinuclear Copper Complex Immobilized on a Janus-Type Material as an Interfacial Heterogeneous Catalyst for Green Synthesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 33091–33101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Thiel, W.R. Atomically-Dispersed Metal Heterocatalysts: A Practical Step Toward Sustainability. ChemNanoMat 2023, 9, e202300399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.; Vorobyeva, E.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. The Multifaceted Reactivity of Single-Atom Heterogeneous Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15316–15329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhao, X.; Lu, T.-B.; Yuan, M.; Wang, M. Graphdiyne-Based Single-Atom Catalysts with Different Coordination Environments. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202219242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptal, V.B.; Ruta, V.; Bajada, M.A.; Vilé, G. Single-Atom Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202219306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedovets, D.; Li, Q.; Leclercq, L.; Nardello-Rataj, V.; Leng, J.; Zhao, S.; Pera-Titus, M. Multiphase Microreactors Based on Liquid–Liquid and Gas–Liquid Dispersions Stabilized by Colloidal Catalytic Particles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202107537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Yu, C.; Wei, Q.; Liu, D.; Qiu, J. Pickering Emulsion Catalysis: Interfacial Chemistry, Catalyst Design, Challenges, and Perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202115885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, G.; Tüysüz, H.; Duyckaerts, N.; Knossalla, J.; Wang, G.-H.; Schüth, F. Hollow Nano- and Microstructures as Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14056–14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Weber, K.; Demchenko, A.; Lösch, P.; Breuninger, P.; Lösch, A.; Kopnarski, M.; Antonyuk, S.; Kleist, W.; Thiel, W.R. Janus Bifunctional Periodic Mesoporous Organosilica. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichaita, W.; Polpanich, D.; Tangboriboonrat, P. Review on Synthesis of Colloidal Hollow Particles and Their Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 20880–20901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Thiel, W.R. Periodic Mesoporous Organosilica Nanomaterials with Unconventional Structures and Properties. Chem. Eur. J. 2023, 29, e202204005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ahmed, A.; Yu, B.; Cong, H.; Shen, Y. Preparation, application and development of poly(ionic liquid) microspheres. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 362, 119706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Tokuda, M.; Suzuki, T.; Minami, H. Preparation of Poly(ionic liquid) Hollow Particles with Switchable Permeability. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Miras, H.N.; Song, Y. Self-Organization of Ionic Liquid-Modified Organosilica Hollow Nanospheres and Heteropolyacids: Efficient Preparation of 5-HMF Under Mild Conditions. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2526–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, K.S.M.; Mamone, P.; Dörr, G.; Bauer, T.O.; Brodyanski, A.; Wagner, C.; Kopnarski, M.; Taylor, R.N.K.; Demeshko, S.; Meyer, F.; et al. Facile Synthesis of Monodisperse Maghemite and Ferrite Nanocrystals from Metal Powder and Octanoic Acid. J. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 1430–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Medina, M.D.; Prinsen, P.; Li, H.; Shih, K.; Romero, A.A.; Luque, R. Continuous-Flow Synthesis of Supported Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Efficient Isoeugenol Conversion into Vanillin. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Guan, J. Applications of Magnetic Nanomaterials in Heterogeneous Catalysis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 4681–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Zou, H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Shia, Z.; Qiu, S. Yolk–shell Fe3O4@SiO2@PMO: Amphiphilic magnetic nanocomposites as an adsorbent and a catalyst with high efficiency and recyclability. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallat, Y.; Jum’h, I.; Al Bsoul, A.; Jumah, R.; Telfah, A. Photocatalytic Degradation Dynamics of Methyl Orange Using Coprecipitation Synthesized Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonogashira, K. Development of Pd–Cu catalyzed cross-coupling of terminal acetylenes with sp2-carbon halides. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 653, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonogashira, K.; Tohda, Y.; Hagihara, N. A convenient synthesis of acetylenes: Catalytic substitutions of acetylenic hydrogen with bromoalkenes, iodoarenes and bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975, 16, 4467–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, R.; Nájera, C. The Sonogashira Reaction: A Booming Methodology in Synthetic Organic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 874–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, I.; Mujahid, A.; Rasool, N.; Rizwan, K.; Malik, A.; Ahmad, G.; Shah, S.A.A.; Rashid, U. Palladium and Copper Catalyzed Sonogashira cross Coupling an Excellent Methodology for C-C Bond Formation over 17 Years: A Review. Catalysts 2020, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, H.; Hierso, J.-C. Palladium-Based Catalytic Systems for the Synthesis of Conjugated Enynes by Sonogashira Reactions and Related Alkynylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 834–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukhani, M.; Panahi, F.; Khalafi-Nezhad, A. Supported Palladium on Magnetic Nanoparticles–Starch Substrate (Pd-MNPSS): Highly Efficient Magnetic Reusable Catalyst for C–C Coupling Reactions in Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, S.; Zeraatkar, Z.; Zarifi, F. Pd complex of an NNN pincer ligand supported on γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 magnetic nanoparticles: A new catalyst for Heck, Suzuki and Sonogashira coupling reactions. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 7076–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, I.; Chakraborty, J.; Khan, A.; Arshad, M.N.; Azum, N.; Rab, M.A.; Asiri, A.M.; Alamry, K.A.; Verpoort, F. Conjugated mesoporous polyazobenzene–Pd(II) composite: A potential catalyst for visible-light-induced Sonogashira coupling. J. Catal. 2019, 377, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, H.; Li, R.; Tao, Y.; Guo, X.; Anderson, E.A.; Whiting, A.; Wu, N. Synthesis of Sulfonamide-Based Ynamides and Ynamines in Water. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 1938–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jv, J.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Dong, Y. Porous organic polymer with in situ generated palladium nanoparticles as a phase-transfer catalyst for Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction in water. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 21671–21678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Mondal, P.; Roy, A.S.; Tuhina, K. Suzuki and Sonogashira Cross-Coupling Reactions in Water Medium with a Reusable Poly(N-vinylcarbazole)-Anchored Palladium(II) Complex. Synthesis 2010, 2010, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Smith, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Takale, B.S.; Gallou, F.; Lipshutz, B.H. Sustainable HandaPhos-ppm Palladium Technology for Copper-Free Sonogashira Couplings in Water under Mild Conditions. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipshutz, B.H.; Chung, D.W.; Rich, B. Sonogashira Couplings of Aryl Bromides: Room Temperature, Water Only, No Copper. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3793–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Dai, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z. Copper-Free Sonogashira Coupling Reaction with PdCl2 in Water under Aerobic Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struwe, J.; Ackermann, L.; Gallou, F. Recent progress in copper-free Sonogashira-Hagihara cross-couplings in water. Chem Catal. 2023, 3, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajer, F.; Heravi, M.M.; Zadsirjan, V.; Poormohammad, N. Copper-free Sonogashira cross-coupling reactions: An overview. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 6885–6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, R.; Nájera, C. Recent advances in Sonogashira reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5084–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, C. Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Acetenylbenzols. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1869, 2, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, C. Untersuchungen über einige Derivate der Zimmtsäure. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1870, 154, 137–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, P.; Livingston, R.C.; Diederich, F. Acetylenic Coupling: A Powerful Tool in Molecular Construction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 2632–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekarrao, K.; Kaishap, P.P.; Gogoi, S.; Boruaha, R.C. Palladium-Catalyzed One-Pot Sonogashira Coupling, exo-dig Cyclization and Hydride Transfer Reaction: Synthesis of Pyridine-Substituted Pyrroles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, Y.B.; Volov, A.N.; Tomilova, L.G. Palladium(II) phthalocyanines efficiently promote phosphine-free Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction at room temperature. J. Catal. 2020, 391, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, Y.B.; Volov, A.N.; Tomilova, L.G. Palladium(II) octaalkoxy- and octaphenoxyphthalocyanines: Synthesis and evaluation as catalysts in the Sonogashira reaction. J. Catal. 2019, 373, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martek, B.A.; Gazvoda, M.; Urankar, D.; Košmrlj, J. Designing Homogeneous Copper-Free Sonogashira Reaction through a Prism of Pd–Pd Transmetalation. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 4938–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urgaonkar, S.; Verkade, J.G. Ligand-, Copper-, and Amine-Free Sonogashira Reaction of Aryl Iodides and Bromides with Terminal Alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5752–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, F.; Guo, M.; Xu, J.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z. A Copper- and Amine-Free Sonogashira Reaction Employing Aminophosphines as Ligands. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5428–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholinejad, M.; Bahrami, M.; Nájera, C.; Pullithadathil, B. Magnesium oxide supported bimetallic Pd/Cu nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for Sonogashira reaction. J. Catal. 2018, 363, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xu, G.; Yuan, J.; Ye, S.; Chen, L.; Lv, Q.; Luo, G.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; et al. An efficient nanocluster catalyst for Sonogashira reaction. J. Catal. 2021, 401, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, R.G.; Köhler, K.; Krauter, J.G.E.; Pietsch, J. Pd/C as a Highly Active Catalyst for Heck, Suzuki and Sonogashira Reactions. Synlett 2002, 2002, 1118–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carril, M.; Correa, A.; Bolm, C. Iron-Catalyzed Sonogashira Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4862–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Johansson, A.J.; Zuidema, E.; Bolm, C. Mechanistic Insights into Copper-Catalyzed Sonogashira–Hagihara-Type Cross-Coupling Reactions: Sub-Mol% Catalyst Loadings and Ligand Effects. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 8144–8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Lim, J.; Peng, C.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Zou, J. Pd/Fe2O3 with Electronic Coupling Single-Site Pd–Fe Pair Sites for Low-Temperature Semihydrogenation of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, A.J.R.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; McEwen, J. Enhanced Fe2O3 Reducibility via Surface Modification with Pd: Characterizing the Synergy within Pd/Fe Catalysts for Hydrodeoxygenation Reactions. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3381–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ayman, K.M.; Hensley, A.J.R.; Gu, M.; Engelhard, M.H.; McEwen, J.; Wang, Y. Synergistic Catalysis between Pd and Fe in Gas Phase Hydrodeoxygenation of m-Cresol. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 3335–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Zhong, C.; Tada, M.; Iwasawa, Y. Immobilized metal ion-containing ionic liquids: Preparation, structure and catalytic performance in Kharasch addition reaction. Chem. Commun. 2005, 2005, 2506–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaeezadeh, M.; Hashemi, M.M. Simple and green oxidation of cyclohexene to adipic acid with an efficient and durable silica-functionalized ammonium tungstate catalyst. Catal. Commun. 2014, 43, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakal, S.; Garlisi, C.; Özcan, L.; Bellardita, M.; Palmisano, G. (Photo)catalyst Characterization Techniques: Adsorption Isotherms and BET, SEM, FTIR, UV–Vis, Photoluminescence, and Electrochemical Characterizations. In Heterogeneous Photocatalysis; Marcì, G., Palmisano, L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 87–152, Chapter 4. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, N.N.; Gibb, T.C. Mössbauer Spectroscopy; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kataria, M.; Pramanik, S.; Kaur, N.; Kumar, M.; Bhalla, V. Ferromagnetic α-Fe2O3 NPs: A potential catalyst in Sonogashira–Hagihara cross coupling and hetero-Diels–Alder reactions. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Bai, F. Disentangling the role of oxygen vacancies on the surface of Fe3O4 and γ-Fe2O3. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2660–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, T.; Shi, F.; Ma, H.; Wang, B.; Dai, X.; Cui, X. Constructing multiple active sites in iron oxide catalysts for improving carbonylation reactions. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivančič, A.; Košmrlj, J.; Gazvoda, M. Elucidating the reaction mechanism of a palladium-palladium dual catalytic process through kinetic studies of proposed elementary steps. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ke, J.; Xu, H.; Lei, A. Synergistic Catalysis in the Sonogashira Coupling Reaction: Quantitative Kinetic Investigation of Transmetalation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1527–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Ta, L.T.; Huang, Y.; Su, H.; Lin, Z. Incorporating Domain Knowledge and Structure-Based Descriptors for Machine Learning: A Case Study of Pd-Catalyzed Sonogashira Reactions. Molecules 2023, 28, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazvoda, M.; Virant, M.; Pinter, B.; Košmrlj, J. Mechanism of copper-free Sonogashira reaction operates through palladium-palladium transmetallation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Li, D.; Yang, R.; Xia, Z. Base-assisted transmetalation enables gold-catalyzed oxidative Sonogashira coupling reaction. iScience 2024, 27, 108531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Peng, Y.; Cui, L.; Zhang, L. Gold-Catalyzed Homogeneous Oxidative Cross-Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3112–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wei, W.; Xie, Y.; Lei, Y.; Li, J. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Electron-Poor Terminal Alkynes with Arylboronic Acids under Ligand-Free and Aerobic Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 5635–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Zhang, J. Au(I)/Au(III)-catalyzed Sonogashira-type reactions of functionalized terminal alkynes with arylboronic acids under mild conditions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basha, K.S.; Balamurugan, R. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective Hydroarylation of Propiolic Acid with Arylboronic Acids. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 4803–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Shi, W.; Lei, A. Bond Formations between Two Nucleophiles: Transition Metal Catalyzed Oxidative Cross-Coupling Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1780–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnlaugsson, H.P. Spreadsheet based analysis of Mössbauer spectra. Hyperfine Interact. 2016, 237, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ye, M.; Xue, Y.; Yin, G.; Wang, D.; Huang, J. Sonogashira coupling catalyzed by the Cu(Xantphos)I–Pd(OAc)2 system. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 3137–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhar, P.R.; Subhas, M.S.; Roy, M.; Roy, S.; Kantam, M.L. Copper-Free Sonogashira Coupling of Acid Chlorides with Terminal Alkynes in the Presence of a Reusable Palladium Catalyst: An Improved Synthesis of 3-Iodochromenones (=3-Iodo-4H-1-benzopyran-4-ones). Helv. Chim. Acta 2008, 91, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Jin, B.; Bora, P.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gallou, F.; Reilly, J.; Lipshutz, B.H. Sonogashira Couplings Catalyzed by Fe Nanoparticles Containing ppm Levels of Reusable Pd, under Mild Aqueous Micellar Conditions. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.; Bhunia, B.K.; Mandal, G.; Nag, B.; Jaiswal, C.; Mandal, B.B.; Kumar, A. Room-Temperature, Copper-Free, and Amine-Free Sonogashira Reaction in a Green Solvent: Synthesis of Tetraalkynylated Anthracenes and In Vitro Assessment of Their Cytotoxic Potentials. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 16907–16926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).