Abstract

C6F12O has been recognized as an environmentally friendly substitute applied in the fire protection, insulation equipment, and refrigeration industry. The stability and catalytic decomposition characteristics of C6F12O in the presence of metals are crucial for evaluating the applicability of such alternatives across different scenarios and recycling treatment. In this study, the adsorption and decomposition mechanisms of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces have been investigated based on the density functional theory (DFT). The adsorption structures and energies of C6F12O and its key dissociation products are investigated to obtain the most stable adsorption configurations. Additionally, the projected density of states (PDOS) and electron density difference calculations are performed to explore the electronic properties of the adsorption systems. Four major dissociation reactions involving the C-C bond breakage of C6F12O that occurred on Cu surfaces are examined individually, with comparisons made to the corresponding homolytic reactions of free C6F12O. The results indicate that Cu surfaces exhibit a promising catalytic effect for C6F12O decomposition, which depends on both the kind of surfaces and the reaction pathway. Furthermore, most decomposition pathways of C6F12O on Cu surfaces are exothermic and C6F12O tends to decompose into C5F9O and CF3 under the Cu catalytic effect.

1. Introduction

Fluorine-containing substances such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) with their excellent thermodynamic performance, radical capture, and insulating ability are widely applied in fire protection [,], the refrigeration industry [], and gas-insulated equipment []. However, HFCs and SF6 are recognized as strong greenhouse gases with a high global warming potential (GWP) and long atmospheric lifetime (ALT) [,,,]. Heptafluoropropane (also called HFC 227ea) is one of the most widely used fire suppressants with the GWP up to 3350 and the ALT 38.9 years, and, for the GWP of the insulating gas, the SF6 is 23,500 and ALT is 3200 years. These greenhouse gases are scheduled to phase out according to the Kyoto Protocol (1997) [] and the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol (2016) []. Hence, seeking environmentally friendly substitutes is of great importance [,]. In recent years, C6F12O (perfluro-2-methyl-3-pentanone, also called FK-5112, trade name Novec 1230 or Novec 649) has drawn much attention due to its environmentally friendly performance, and low GWP (approximately 1) and ALT (2 weeks). And its approximately nontoxicity, noncombustility, and outstanding thermodynamic and insulation performance has made C6F12O a promising substitute for HFCs and SF6 in these fields [,,,,].

In practical application, the stability of such a working fluid during storage and transport is of great importance for system operation. However, unwanted incidents such as discharge or being overheated may induce decomposition, which may lead to function failure and both environment and toxicity issues as reported in previous studies [,,]. Moreover, the decomposition of C6F12O can also occur through photolysis, hydration, and hydrolysis [,]. The decomposition pathways of C6F12O have been investigate both through experiments and theoretical ways. Zhang et al. [] studied the decomposition products of C6F12O and N2 mixed gas under AC voltage by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry; the breakage of the C-C bond as the initial decomposition pathway was obtained through density functional theory (DFT). This dissociation mechanism of C6F12O was also found in overheated scenes by experiment and DFT analysis []. Besides, our previous work [,] examined the initial decomposition pathways that, mainly, through the break of C-C bonds by ReaxFF molecular dynamic simulations, further determined the dissociation mechanism of C6F12O.

Although some studies have explored the stability of the fluid itself and its decomposition mechanism, C6F12O inevitably interacts with container materials during storage and operation. Given that certain metal components act as effective adsorbents and catalysts, the aforementioned decomposition process may be accelerated. Compatibility thus emerges as a critical issue, as it impacts not only material corrosion but also working fluid stability. In terms of adsorption, Li et al. [] studied the interaction between C6F12O and metals (Cu, Al, and Ag) through both experiment and DFT calculation, which found that the interaction between C6F12O and Cu, and Al introduces fluorine to the metal surface and generates some byproducts, and the interaction mechanism between C6F12O and Cu, and Al is chemical adsorption. Similarly, the interaction between C5F12O and Al (1 1 1) and Ag (1 1 1) was also studied by the DFT method and the interaction between Al (1 1 1) is chemical adsorption, which is stronger than physical interaction as C5F12O interacts with Ag (1 0 0) []. Zhang et al. [] studied the decomposition of C5F9O and conducted the DFT calculations to investigate the compatibility of the decomposition products with Cu and Al. Furthermore, regarding the catalytic effects on the decomposition of the metals in contact with the working fluid, Cui et al. [] analyzed the adsorption and decomposition of SF6 on α-Al2O3 (0 0 0 1) through a DFT study and found that α-Al2O3 has certain catalytic properties. Huo et al. [] investigated the catalytic mechanisms of Cu (1 1 1), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 0 0) surfaces on HFO-1336mzz (Z) decomposition through DFT calculations, finding that Cu could obviously promote the dissociation of HFO-1336mzz (Z) and the Cu (1 0 0) surface has the highest catalytic activity while the Cu (1 1 1) surface has the lowest. Zhang et al. []. investigated the compatibility between the C6F12O-air gas mixture and copper and aluminum through experiments, and the results showed that C6F12O-air is incompatible with heated copper, resulting in the decomposition reactions, and the metal acts as a catalyst that could decrease the energy barrier of C6F12O. In addition to stability concerns, environmental considerations highlight that the catalytic decomposition of C6F12O after long-term use—including its recovery and treatment—will also emerge as a critical research topic in the future. Since previous studies have shown that metals may exert a catalytic effect on the decomposition of fluorine-containing substances, it is imperative that we explore the catalytic decomposition mechanism of C6F12O on metal surfaces.

In this work, considering that copper is a widely used material in application scenarios of C6F12O, the catalytic effect of Cu on the decomposition of different substances has been extensively investigated via DFT calculations [,,,,], which shows this method is a powerful tool for illustrating the mechanism of surface reactions at the molecular level. The DFT method has been applied to explore the adsorption and catalytic decomposition mechanism of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces. Four initial dissociation reactions involving C-C bond breakage are considered to investigate the catalytic decomposition mechanism of C6F12O first, and then the adsorption configurations of C6F12O, the relative dissociation products, and co-absorbed species on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are determined. Finally, four decomposition pathways of C6F12O on these surfaces are calculated compared to the pathways of free C6F12O to illuminate the catalytic decomposition mechanism of C6F12O on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces.

2. Results

2.1. Adsorption

2.1.1. Adsorption of C6F12O and Products on Cu (1 0 0) Surface

Three typical adsorption sites (top, bridge, and hole) on the Cu (1 0 0) surface are considered for C6F12O and its decomposition products. The most stable adsorption states and the corresponding adsorption energies, configurations, and key bond length for each species absorbed on the Cu (1 0 0) surface are listed in Table 1. The most stable adsorption structures of C6F12O and the relevant products on the Cu (1 0 0) surface are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Adsorption site, configuration, bond length, and energy for C6F12O and its decomposition species on Cu (1 0 0).

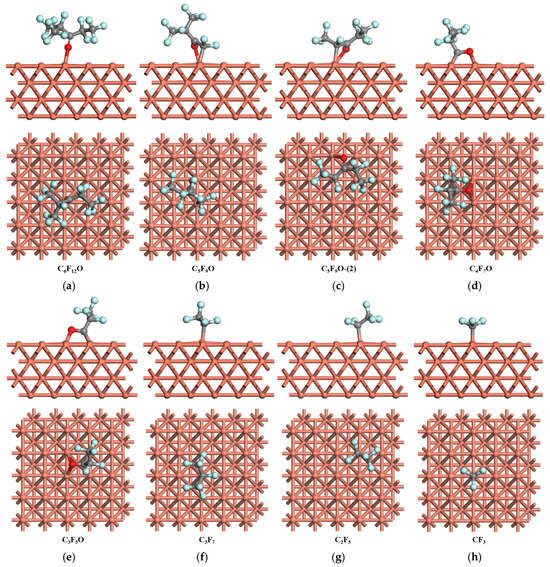

Figure 1.

The most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O and the relevant products on Cu (1 0 0) surface. Color code: carbon—gray, oxygen—red, fluorine—blue, Cu—orange.

As for obtaining the most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O, several initial geometric structures of C6F12O are built where the molecule with different orientations is placed on different sites of the surface, considering the particular functional groups in the molecule [,,]. After geometric optimization calculations of the three different adsorption sites (top, bridge, and hole) on the Cu (1 0 0) surface, the most stable adsorption structure is the O atom adsorbed on the top site of the Cu (1 0 0) surface, as shown in the Figure 1a, which is consistent with the previous studies [,] and the electrostatic potential and dipole moment analysis of C6F12O. The O atom bonding with the Cu atom with the bond length of 2.005 Å and the O atom has a little movement from the top site after interaction. The adsorption energy reaches 1.02 eV.

The initial geometric structures of the dissociation species of C6F12O through the breakage of the C-C bond are established by the C atom with an unpaired electron paralleled to the different adsorption sites of the metal surface. There are two isomers of C5F9O: one is (CF3)2CF2COCF2 (C5F9O), the other is CF3CF2COCF2CF3 (C5F9O-(2)). For C5F9O, the most stable adsorption structure on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is shown in Figure 1b. C5F9O adsorbed on the Cu (1 0 0) surface through C-Cu and O-Cu has a relatively lower absorption energy, 2.07 eV, and the bond length of C-Cu is 2.040 Å and O-Cu 2.102 Å. Meanwhile, its isomer C5F9O-(2) adsorbs on the top site of the Cu (1 0 0) surface through C-Cu and O-Cu with an adsorption energy of 2.55 eV. The bond length of C-Cu is 2.093 Å and that of O-Cu is 2.132 Å, as shown in Figure 1c.

C4F7O prefers to absorb on the bridge site of the Cu (1 0 0) surface through the C=O bond, by which C interacts with two Cu atoms forming a C-Cu bond and O with another two Cu atoms forming an O-Cu bond, as shown in Figure 1d. The length of the C-Cu bonds is 2.030 and 2.022 Å, respectively, and that of the O-Cu bonds 2.131 and 2.111 Å, respectively. The adsorption energy of the most stable structure is 2.62 eV. The most stable adsorption structure of C3F5O on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is the C=O adsorbed on the bridge site (shown in Figure 1e), similar to C4F7O. The adsorption energy is 2.52 eV. The length of the C-Cu bonds is 2.020 and 2.026 Å, respectively, and the length of the O-Cu bonds is 2.123 and 2.109 Å, respectively.

Three initial adsorption structures have been considered for C3F7, C2F5, and CF3, and the most stable adsorption structures are the species residing on the top site of the Cu (1 0 0) surface forming C-Cu bonds, as shown in Figure 1f–h. The length of the C-Cu bond of C3F7, C2F5, and CF3 is 2.051 Å, 1.996 Å, and 1.977 Å, respectively. The adsorption energy of CF3 is 3.19 eV, which is the largest among these three species, and the adsorption energy of C3F7 and C2F5 is 2.38 and 2.23 eV, respectively. Though CF3 could adsorb on the bridge sites forming two C-Cu bonds, the adsorption energy is lower, which is not as stable as the top site adsorption.

2.1.2. Adsorption of C6F12O and Products on Cu (1 1 0) Surface

Four typical adsorption sites (top, hole, short bridge, and long bridge) on the Cu (1 1 0) surface are considered for C6F12O and the decomposition products. The most stable adsorption states and the corresponding adsorption energies, configurations, and key bond length for each species absorbed on the Cu (1 1 0) surface are listed in Table 2. The most stable adsorption structures of C6F12O and the relevant products on the Cu (1 1 0) surface are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Adsorption site, configuration, bond length, and energy for C6F12O and its decomposition species on Cu (1 1 0).

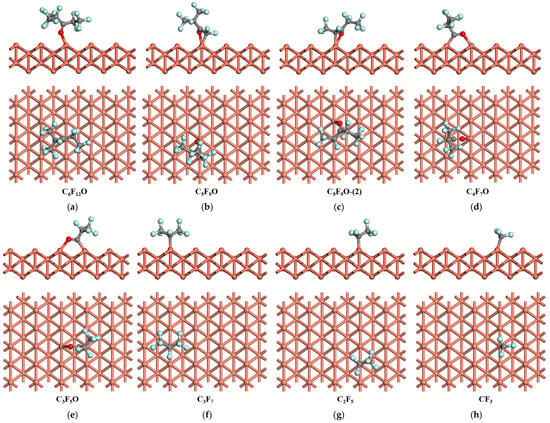

Figure 2.

The most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O and the relevant products on Cu (1 1 0) surface.

For the adsorption of C6F12O on the Cu (1 1 0) surface, the most stable adsorption configuration is the one where C6F12O adsorbs on the top site, with the length of the O-Cu bond being 1.967 Å. The calculated adsorption energy of C6F12O is 1.21 eV, as shown in Figure 2a. The adsorption of C5F9O and C5F9O-(2) on the Cu (1 1 0) surface is similar to the Cu (1 0 0) surface, which C5F9O prefers to adsorb on the top site through C-Cu and O-Cu bonds (Figure 2b,c). For C5F9O, the adsorption energy on the top site is 2.26 eV and the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds is 2.012 and 2.072 Å, respectively, while the adsorption energy for C5F9O-(2) is 2.76 eV and the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds is 2.068 and 2.073 Å, respectively. Both C4F7O and C3F5O tend to absorb on the long bridge site of the Cu (1 1 0) surface through C=O bonds (Figure 2d,e). The adsorption energy of C4F7O on the long bridge site of the Cu (1 1 0) surface is 2.81 eV with the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds being 1.919 and 2.060 Å, respectively. And the adsorption energy of C3F5O on the Cu (1 1 0) surface is 2.67 eV with the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds being 1.925 and 2.067 Å, respectively. For C3F7, C2F5, and CF3, after geometric optimization, the most stable adsorption configurations are those where these species adsorb on the top site of Cu (1 1 0), forming C-Cu bonds, as shown in Figure 2f–h. The length of the C-Cu bonds is 2.032, 1.979, and 1.967 Å, respectively, and the adsorption energy of the most stable adsorption structures is 2.59, 2.35, and 3.32 eV.

2.1.3. Adsorption of C6F12O and Products on Cu (1 1 1) Surface

Four typical adsorption sites (top, bridge, hcp, and fcc) on the Cu (1 1 1) surface are considered for C6F12O and its decomposition products. The most stable adsorption states and the corresponding adsorption energies, configurations, and key bond length for each species absorbed on the Cu (1 1 1) surface are listed in Table 3. The most stable adsorption structures of C6F12O and the relevant products on the Cu (1 1 1) surface are shown in Figure 3.

Table 3.

Adsorption site, configuration, bond length, and energy for C6F12O and its decomposition species on Cu (1 1 1).

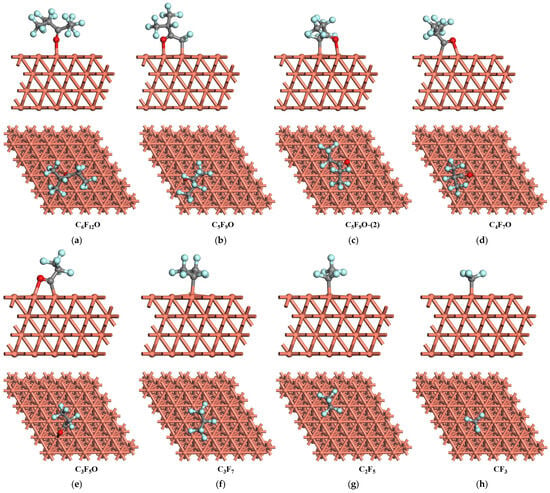

Figure 3.

The most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O and the relevant products on Cu (1 1 1) surface.

For the Cu (1 1 1) surface, the most stable adsorption configuration of C6F12O is that the molecule binds to the top site of the surface forming an O-Cu bond with a length of 2.090 Å as shown in Figure 3a. The calculated adsorption energy is 0.93 eV. The adsorption configuration of C5F9O and C5F9O-(2) on the Cu (1 1 1) surface is similar to that on the Cu (1 0 0) and Cu (1 1 0) surface. The species reside on the top site of the surface, forming C-Cu and O-Cu bonds (Figure 3b,c). For C5F9O, the adsorption energy is 1.77 eV with the length of C-Cu and O-Cu being 2.045 and 2.136 Å, respectively, while the adsorption energy for C5F9O-(2) is 2.23 eV and the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu is 2.090 and 2.129 Å, respectively. C4F7O and C3F5O would absorb on the bridge site of the Cu (1 1 1) surface (Figure 3d,e). The adsorption energy of C4F7O on the bridge site of the Cu (1 1 1) surface is 2.35 eV with the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds being 1.919 and 2.191 Å, respectively. Meanwhile, the adsorption energy of C3F5O on the Cu (1 1 1) surface is 2.21 eV with the length of the C-Cu and O-Cu bonds being 1.925 and 2.181 Å, respectively. C3F7, C2F5, and CF3 tend to reside on the top site of the Cu (1 1 1) surface, forming C-Cu bonds after geometry optimization, as shown in Figure 3f–h. The length of the C-Cu bond of each species is 2.080, 2.013, and 1.993 Å respectively, and the adsorption energy of the most stable adsorption configurations is 2.15, 2.06, and 3.06 eV.

2.2. Co-Adsorption

As the dissociation reactions of C6F12O occurs on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces, the co-adsorption configurations and adsorption energies of decomposition products including C5F9O + CF3, C5F9O-(2) + CF3, C4F7O + C2F5, and C3F5O + C3F7 have been studied to obtain the final states in the dissociation reactions of C6F12O on the metal surfaces.

The co-adsorption energy () for the dissociation species adsorbed on Cu surfaces could be defined as follows:

where , , , and represent the total energy of the radical A and B, the Cu slab, and co-adsorption structure ().

Considering the initial co-adsorption structures in the geometry optimization calculations, the corresponding dissociation species are placed adjacently and at the most stable adsorption site on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces [,]. For example, for the co-adsorption of C5F9O + CF3 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface, the initial structure is that C5F9O is placed on the top site and CF3 on the adjacent top site according to the calculation results before.

The optimized co-adsorption structures after calculations are shown in Figure 4, and the most stable co-adsorption sites, the corresponding co-adsorption energies, and the sum of the separated adsorption energies, Esum, are listed in Table 4. After geometry optimizations of each configuration, the co-adsorption structures mainly maintain their initial states, except for some tiny movement around the adsorption sites due to the repulsive interaction between the related species.

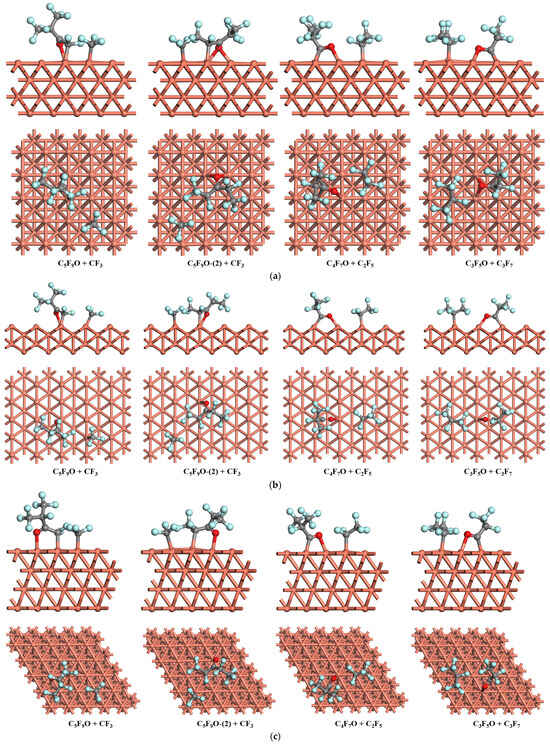

Figure 4.

Optimized co-adsorption on the Cu surfaces: (a) Cu (1 0 0), (b) Cu (1 1 0), and (c) Cu (1 1 1).

Table 4.

Adsorption site and energy for C6F12O and its decomposition species on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1).

From Table 4, it can be found that most of the co-adsorption energies are a little less than the sum of the corresponding separated adsorption energies, which may indicate the presence of interaction energies between the co-adsorbed species as well as tiny differences in the interaction strength of these species with the Cu surfaces.

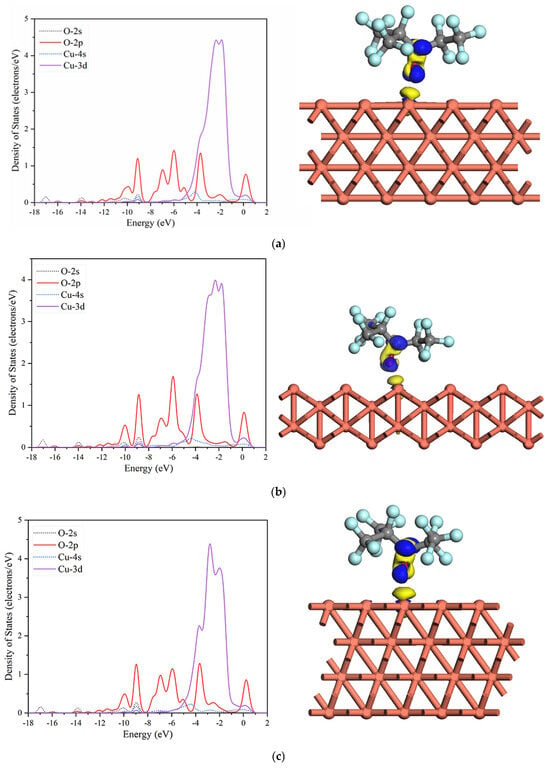

2.3. Electronic Properties of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) Surfaces

To understand the interaction between C6F12O and different copper surfaces, the PDOS on the atomic orbitals of the O atom and the nearest Cu atom and the electron density difference for the most stable adsorption structures are calculated as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

PDOS and charge density difference isosurfaces of the most stable adsorption structures of C6F12O (the blue and yellow regions represent positive and negative values) in 0.03 isovalue: (a) Cu (1 0 0), (b) Cu (1 1 0), and (c) Cu (1 1 1).

It can be found that the PDOS of C6F12O on the different Cu surfaces is similar. From −10.6 to −8.2 eV and −0.5 to 1 eV, the density of states (DOS) is mainly contributed by the 2p orbital of the O atom. From −4.5 to −0.7 eV, the DOS is primarily contributed by the Cu 3d orbital. A large overlap between the O 2p orbital and the Cu 3d orbital is observed in the energy range of −4.5 to −0.7 eV and −0.5 to 1 eV, which indicates that the formation of the adsorption bonds is mainly due to the mixing between the O 2p orbital and Cu 3d orbital. The overlap in the energy range of −10.6 to −8.2 eV is attributed to the hybridization among the O 2s, O 2p, Cu 4s, and Cu 3d orbitals. Moreover, some slight peaks are observed nearby −14, −16, and −17 eV, which comes from the mixing between O 2s and O 2p.

The electron density difference of the most stable adsorption structure is also analyzed, as shown in Figure 5. The blue and yellow represent the electron accumulation and depletion region, respectively. It can be found that some electrons mainly transfer from the Cu atom to the O atom and the electron density in the vicinity of the O atom increases after the adsorption, which means that Cu surfaces acts as the electron donor and the O atom acts as the electron acceptor and may bind with the Cu atom.

According to the analysis of the electronic properties through the PDOS and electron density difference, the interaction between the O atoms in the C6F12O and Cu surfaces is relatively strong, which could be regarded as chemisorption.

2.4. Decomposition of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) Surfaces

In this section, the dissociation reactions including the breakage of C-C bonds at different positions of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are fully investigated, respectively. The decomposition pathways of C6F12O are listed as follows:

C6F12O → C5F9O + CF3

C6F12O → C5F9O-(2) + CF3

C6F12O → C4F7O + C2F5

C6F12O → C3F5O + C3F7

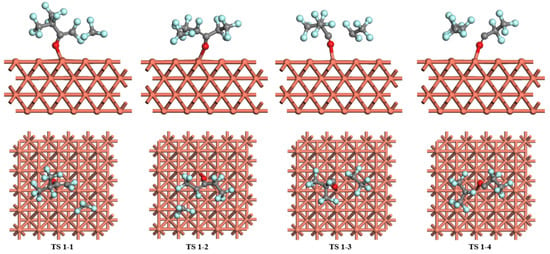

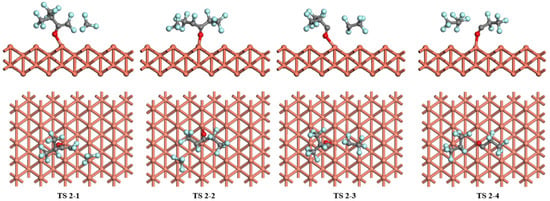

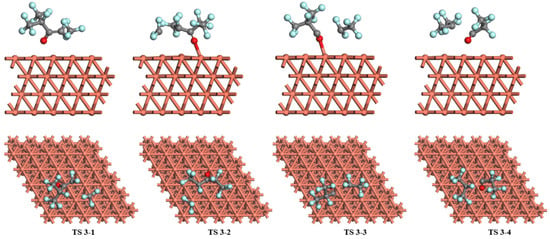

The most stable adsorption configurations of C6F12O on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are chosen as the initial reactants, and the products are the most stable co-adsorption structures of the corresponding dissociation species. The calculated energy barrier (Eb) and the reaction energy () of each dissociation reaction pathway are listed in Table 5. The related transition states (TS) of each reaction are shown in Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

Table 5.

Energy of C6F12O decomposition reactions pathways on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces.

Figure 6.

The transition states of C6F12O dissociation on the Cu (1 0 0) surface.

Figure 7.

The transition states of C6F12O dissociation on the Cu (1 1 0) surface.

Figure 8.

The transition states of C6F12O dissociation on the Cu (1 1 1) surface.

For the dissociation of C6F12O on the Cu (1 0 0) surface, the most stable adsorption configuration where C6F12O adsorbs on the top site is chosen as the initial reactant, then the reactant would decompose into small species through the breakage of C-C bonds as shown in Figure 6. In pathway 1, C6F12O dissociates into the C5F9O and CF3 via TS 1-1. The angle of the C-O-Cu bond decreases from 173.1° to 112.3° in TS 1-1, which means the C-O bond is closer to the Cu (1 0 0) surface. The length of the O-Cu bond is about 2.196 Å compared to the 2.005 Å in the initial state. After TS 1-1, C5F9O adsorbs on the top site of the surface, forming O-Cu and C-Cu bonds. The energy barrier and reaction energy of pathway 1 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is 2.25 and 0.03 eV, respectively. Pathway 2 is where C6F12O decomposes into C5F9O-(2) and CF3 through the breakage of the C-C bond at the other end of C6F12O. In TS 1-2, the initial O-Cu bond has been broken and C5F9O-(2) absorbs on the Cu (1 0 0) surface forming the O-Cu bond. After TS 1-2, C5F9O-(2) moves to the bridge site and CF3 moves to the top site. The energy barrier of the reaction is 2.49 eV, which is a little higher than pathway 1, and pathway 2 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is exothermic, the reaction energy of which is −0.42 eV. In pathway 3, C6F12O dissociates into C4F7O and C2F5 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface through TS 1-3 where the distance between the dissociated C atoms increases from 1.531 to 2.747 Å. The bond length of O-Cu changes from 2.005 to 2.039 Å. Passing through TS 1-3, the dissociated C4F7O would move to the hole site and C2F5 to the top site. The energy barrier of pathway 3 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is 3.56 eV, and the reaction energy is −0.50 eV, which is also exothermic. For pathway 4, it starts from the most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O occupying the top site via the O atom on the Cu (1 0 0) surface, then the breakage of the C-C bond leads to the co-adsorption of C3F5O and C3F7 via TS 1-4. The O-Cu bond is stretched to 2.141 Å and the angle of C-O-Cu decreases from 173.1° to 132.2°. After TS 1-4, C3F7 adsorbs on the adjacent top sites forming the C-Cu bond and C3F5O adsorbs on the hole sites with the C-O almost parallel to the surface. The energy barrier of pathway 4 on the Cu (1 0 0) surface is 3.70 eV and the reaction energy is −0.59 eV, which indicates this pathway is an exothermic reaction.

For the dissociation of C6F12O on the Cu (1 1 0) surface, the four pathways mentioned before are fully investigated as shown in Figure 7. The most stable adsorption structure of C6F12O on the Cu (1 1 0) surface is selected as the initial reactant of each pathway. In pathway 1, the cleavage of the C-C bond in C6F12O generates C5F9O and CF3 species through TS 2-1, where the distance of the dissociated C atoms increases from 1.564 to 2.903 Å. The angle of C-O-Cu changes to 127.3° from the initial state, 140.2° which indicates that C5F9O is much closer to the surface in TS 2-1. Then, C5F9O adsorbs on the top site of the Cu (1 1 0) surface, forming C-Cu and O-Cu bonds, and CF3 resides on the top site. The energy barrier and the reaction energy of pathway 1 are 2.77 eV and −0.12 eV, respectively. In pathway 2, C6F12O decomposes into C5F9O-(2) and CF3 via TS 2-2. C5F9O-(2) moves to the bridge site of the Cu (1 1 0) surface through O-Cu bonds in TS 2-2, and then it adsorbs on the top site of the surface similar to CF3. Pathway 2 has an energy barrier of 2.57 eV and a reaction energy of −0.57 eV. As C6F12O dissociates to C4F7O and C2F5 (pathway 3) via TS 2-3 on the Cu (1 1 0) surface, the angle of C-O-Cu decreases from 140.2° to 124.8° in TS 2-3 with the length of the O-Cu bond rising to 2.126 Å. The distance between the dissociated C atoms is 3.127 Å compared with 1.518 Å at the beginning. Passing through TS 2-3, C4F7O adsorbs on the long bridge site and C2F5 adsorbs on the top site. Pathway 3 needs to conquer the energy barrier of 3.48 eV with an exothermic value of −0.71 eV. In pathway 4, the breakage of the C-C bond forming C3F5O and C3F7 needs to overcome the energy barrier of 3.36 eV via TS 2-4. The distance of breakage of C atoms increases to 3.369 Å in TS 2-4. Similar to the products of pathway 3, C3F5O finally binds at the long bridge site and C3F7 binds at the top site, and the reaction energy of pathway 4 is −0.84 eV.

For the dissociation of C6F12O on the Cu (1 1 1) surface (Figure 8), the most stable structure that C6F12O adsorbs on the top site of the surface is chosen as the initial reactant for each pathway. The breakage of the C-C bond forms the C5F9O and CF3 species (pathway 1) via TS 1. The distance between the dissociated C atoms rises to 3.238 Å in TS 3-1 while the C-C bond length in C6F12O is 1.561 Å. In TS 3-1, the decomposition fragments are not bonding with the Cu atoms in the surface, and the length of the Cu-Cu bond below the O atom increases from 2.572 to 2.596 Å. After TS 3-1, C5F9O and CF3 move to the top sites forming O-Cu and C-Cu bonds. The energy barrier of the pathway 1 is 2.75 eV and the reaction energy is 0.32 eV, meaning this reaction is endothermic. As for pathway 2, the length of the O-Cu bond increases from 2.090 to 2.211 Å and the distance between dissociated C atoms increases from 1.574 to 2.936 Å in TS 3-2. Passing through TS 3-2, CF3 and C5F9O adsorb on the top sites of the surface. The energy barrier of this reaction is 2.92 eV and the reaction energy is 0.27 eV, which is also an endothermic reaction. In pathway 3, C6F12O dissociates into C4F7O and C2F5 on the Cu (1 1 1) surface, which need to conquer the energy barrier of 3.59 eV with an exothermic value of −0.15 eV. The bond length of O-Cu is 2.163 Å in TS 3-3 while it is 2.090 Å in the initial state, and the distance of separated C atoms increases to 2.749 Å. After TS 3-3, C2F5 moves to the top site, and C4F7O resides on the bridge site of the surface with the length of C-Cu being 1.929 Å and O-Cu 2.148 Å. For pathway 4, C6F12O decomposes into C3F5O and C3F7 on the Cu (1 1 1) surface via TS 3-4. In TS 3-4, the species are not bonded with Cu atoms on the surface. The distance between the O-Cu bond increases from 2.090 to 2.252 Å, and the distance between the dissociated C atoms rises to 2.594 Å. C3F7 and C3F5O would finally reside on the top site and bridge site of the surface after TS 3-4. The energy barrier and the reaction energy of pathway 4 on the Cu (111) surface are 3.50 and −0.23 eV, respectively.

Compared to the dissociation energies of the free C6F12O molecule in Table 5, the energy barriers of dissociation reactions (pathway 1 and 2) on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are much lower, which indicates the catalytic activity of Cu surfaces in the decomposition of C6F12O. The decomposition pathways of C6F12O on Cu surfaces are mainly exothermic except for the dissociation reactions of pathway 1 and 2 on the Cu (1 1 1) surface. Moreover, different from free C6F12O decomposing, the energy required for pathway 1 and 2 is lower than pathway 3 and 4 on the Cu surfaces, indicating that C6F12O tends to dissociate through pathway 1 and 2, where the Cu (1 0 0) surface exhibits a better catalytic effect.

3. Methods

A generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange correlation function [] is employed in all DFT calculations [,]. A double numerical plus polarization (DNP) basis set and density functional semicore pseudopotential (DSPP) [] are utilized, where DSPP accounts for the relativistic effects of transition atoms. Van der Waals interactions are described via the Grimme method [,]. The Brillouin zone is sampled by a 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack mesh of the k-point [] with a Methfessel–Paxton smearing of 0.003 Ha. The convergence criteria for energy, maximum force, and maximum displacement are 2 × 10−5 Ha, 4 × 10−3 Ha/Å, and 5 × 10−3 Ha, respectively, with a self-consistent field (SCF) convergence accuracy of 1 × 10−6 Ha.

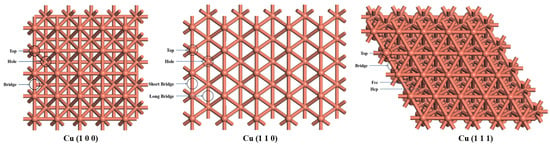

The Cu bulk structure is optimized first and the Cu lattice parameter is 3.61 Å, which is correlated with the experiment result of 3.62 Å [], showing the reliability of the computational method. Considering the balance between the accuracy and computational cost, the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are modeled with a (5 × 5) supercell with a four-layer plate (100 Cu atoms in a cell) compared with the previous studies [,]. The vacuum layer of 20 Å is added between the plates to avoid the periodic interactions. Moreover, the atoms of the bottom two layers are fixed while the upper two layers are relaxed. There are three adsorption sites of the Cu (1 0 0) surface, the top, bridge, and hole; four adsorption sites of the Cu (1 1 0) surface, the top, long bridge, short bridge, and hole; and four adsorption sites of the Cu (1 1 1) surface, the top, bridge, hcp, and fcc, as shown in Figure 9. The adsorption energy () for the substances adsorbed on the Cu surfaces are calculated as follows:

where and represent the total energy of the Cu slab and adsorbate, and represents the total energy of substances adsorbed on the slab.

Figure 9.

The absorption sites of Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surface: from top views.

The charge density difference in the adsorption structures of C6F12O is calculated as the following equation:

where and represent the total density of the Cu slab and C6F12O, and represents the total density of the C6F12O molecule adsorbed on the slab.

The projected density of states (PDOS) is also explored to further analyze the electronic properties and interaction mechanism between the C6F12O and Cu surfaces.

The transition states (TSs) are searched by the complete LST/QST method for the initial decomposition pathways [,,,,]. For the decomposition reactions occurring on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces, the reaction energy () and activation energy () are defined as follows:

where , , and are the total energies of the product (co-adsorbed state), reactant (C6F12O adsorbed state), and transition state, respectively.

To evaluate the catalytic effect of the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces on C6F12O decomposition, the energy of the initial decomposition pathways () of C6F12O is calculated at the same calculation level for comparison, which is defined as follows:

where and are the total energies of C6F12O and its decomposition products.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the adsorption and dissociation of C6F12O on the Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are systematically investigated through DFT calculations. The main conclusions are listed as follows:

The most stable adsorption structures for C6F12O, C5F9O, C5F9O-(2), C4F7O, C3F5O, C3F7, C2F5, and CF3 on Cu surfaces are determined: most of these species, except for C4F7O and C3F5O, prefer to adsorb on the top site of the surfaces. On the Cu (1 0 0) surface, C4F7O and C3F5O prefer to adsorb on the hole site while these species tend to reside on the long bridge and bridge site of the Cu (1 1 0) and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces, respectively. The adsorption energies of each species on the Cu surfaces are obtained and the adsorption energy of the dissociation species is much higher than C6F12O, especially for CF3, indicating a relatively strong interaction with Cu surfaces.

The interaction between the C6F12O and Cu surfaces is relatively strong, which belongs to chemical adsorption according to the PDOS and charge density difference analysis. Moreover, the metal surfaces act as the electron donor and C6F12O would gain electrons through the electronic analysis.

The reaction barriers of some C-C bond decomposition pathways (pathway 1 and pathway 2) via thermodynamically stable intermediates on Cu (1 0 0), Cu (1 1 0), and Cu (1 1 1) surfaces are lower than the dissociation energies of C6F12O alone, which indicates the promising catalytic effect of Cu on the decomposition of C6F12O.

The decomposition pathways of C6F12O on Cu surfaces are mainly exothermic except for the dissociation reactions of pathway 1 and 2 on the Cu (1 1 1) surface. C6F12O tends to dissociate through pathway 1 and 2 on Cu surfaces, which is different from free C6F12O decomposing. The Cu (1 0 0) surface has a better catalytic effect on pathway 1 and 2.

The results also provide a molecular-level analysis of the storage compatibility and stability of C6F12O, as well as the potential post-treatment pathway via catalytic pyrolysis after long-term service in practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; Methodology, H.X.; Validation, S.L.; Formal analysis, H.X.; Investigation, H.X.; Resources, S.L. and H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.X.; Writing—review & editing, S.L. and H.Z.; Supervision, H.Z.; Project administration, H.Z.; Funding acquisition, H.X. and S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFC3010203-5), the Civil Aircraft Scientific Research Project of the Ministry of Industry, Information Technology (BB2320000048), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (WK5290000003), and Anhui Province New-era Education Quality Project, Graduate Education (2022xscx010).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The numerical calculations in this paper have been carried out on the supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China and Hefei advanced computing center. During the preparation of this study, we would like to thank Lvyuan Hao from the School of Chemistry and Materials Science, University of Science and Technology of China, for his kind assistance and valuable discussions regarding the calculation work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xing, H.; Lu, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H. Review on Research Progress of C6F12O as a Fire Extinguishing Agent. Fire 2022, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, R.; Owens, J.; Luckarift, H. Formation and detection of hydrogen fluoride gas during fire fighting scenarios. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 127, 103489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayyab, A.K.S.; Navarro-Esbri, J.; Mota-Babiloni, A. Energy, exergy, and environmental (3E) analysis of a compound ejector-heat pump with low GWP refrigerants for simultaneous data center cooling and district heating. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 133, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Yan, C.; Jia, P.F.; Cao, W. Adsorption and sensing behaviors of SF(6)decomposed species on Ni-doped C3N monolayer: A first-principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, N.; Kalair, A.R.; Khan, N.; Haider, A.; Saleem, Z.; Saleem, M.S. Natural and synthetic refrigerants, global warming: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieffel, Y.; Irwin, T.; Ponchon, P.; Owens, J. Green Gas to Replace SF6 in Electrical Grids. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2016, 14, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.O.; Sherman, N.J.; Carvalho, S.; Gonzalez, M. The global search and commercialization of alternatives and substitutes for ozone-depleting substances. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2018, 350, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, J.B.; Cox, R.A.; Ravishankara, A.R. Atmospheric degradation of ozone depleting substances, their substitutes, and related species. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3704–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyoto Protocol. UNFCCC Website. 1997, pp. 230–240. Available online: http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php (accessed on 1 January 2011).

- Heath, E.A. Amendment to the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer (Kigali amendment). Int. Leg. Mater. 2017, 56, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabie, M.; Franck, C.M. Assessment of Eco-friendly Gases for Electrical Insulation to Replace the Most Potent Industrial Greenhouse Gas SF6. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Xiao, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, D. Insight into the decomposition mechanism of C6F12O-CO2 gas mixture. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lan, J.; Tian, S.; Rao, X.; Li, X.; Yuan, Z.; Jin, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X. Study of compatibility between eco-friendly insulating medium C6F12O and sealing material EPDM. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1244, 130949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Bohdal, T. Heat and flow investigation of NOVEC649 refrigerant condensation in pipe minichannels. Energy 2020, 209, 118447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.-R.; Lin, W.-J. Supercritical heat transfer of NOVEC 649 refrigerant in horizontal minichannels. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 117, 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Cheng, Y.; Lu, S.; Tao, N.; Zhang, H. A reactive molecular dynamics study of the pyrolysis mechanism of C6F12O. Mol. Phys. 2021, 119, e1976425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.P.; Lei, Z.C.; Miao, Y.L.; Yao, Q.; Tang, J. Reaction Thermodynamics of Overthermal Decomposition of C6F12O. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering, Budapest, Hungary, 26–30 August 2019; Németh, B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D.A.; Young, C.J.; Hurley, M.D.; Wallington, T.J.; Mabury, S.A. Atmospheric degradation of perfluoro-2-methyl-3-pentanone: Photolysis, hydrolysis and hydration. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8030–8036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-de-Mera, Y.; Aranda, A.; Notario, A.; Rodriguez, A.; Rodriguez, D.; Bravo, I. Photolysis study of fluorinated ketones under natural sunlight conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 22991–22998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Tian, S.S.; Xiao, S.; Deng, Z.T.; Li, Y.; Tang, J. Insulation Strength and Decomposition Characteristics of a C6F12O and N-2 Gas Mixture. Energies 2017, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; Lu, S.; Tao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H. Insight into C6F12O fire suppression mechanism on coaxial n-heptane flame: Combined experimental and ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.; Chen, D.; Cui, Z.; Tang, J. Insight Into the Compatibility Between C6F12O and Metal Materials: Experiment and Theory. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 58154–58160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Z.; Xiao, S.; Tang, J. Theoretical study on the interaction between C5-PFK and Al (1 1 1), Ag (1 1 1): A comparative study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 464, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, J.; Yang, T.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Li, C.; Deng, Y. Thermal and electrical decomposition products of C5F10O and their compatibility with Cu (1 1 1) and Al (1 1 1) surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 513, 145882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, D. Adsorption and decomposition of SF6 molecule on α-Al2O3 (0 0 0 1) surface: A DFT study. Adsorption 2019, 25, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, E.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Dang, C. Dissociation mechanisms of HFO-1336mzz(Z) on Cu(1 1 1), Cu(1 1 0) and Cu(1 0 0) surfaces: A density functional theory study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 443, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, F.; Tian, S.; Chen, D.; Xiao, S.; Tang, J. Thermal compatibility properties of C6F12O-air gas mixture with metal materials. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 125024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Qin, P.; Fang, T. Decomposition mechanism of formic acid on Cu (111) surface: A theoretical study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 396, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yao, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, G.; Chen, Y. Insights into the mechanism of acetic acid hydrogenation to ethanol on Cu(111) surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 412, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, C.-J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Competitive C–C and C–H bond scission in the ethanol oxidation reaction on Cu(100) and the effect of an alkaline environment. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 15444–15453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xie, S.; Wu, S.; Cui, H. Adsorptions of C5F10O decomposed compounds on the Cu-decorated NiS2 monolayer: A first-principles theory. Mol. Phys. 2023, 121, e2163715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Rao, X.; Li, D.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y. Theoretical study on the compatibility of C4F7N decomposition products with metal oxides: First-principles. J. Fluor. Chem. 2025, 283–284, 110417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Qin, P.; Fang, T. Mechanism of ammonia decomposition on clean and oxygen-covered Cu (111) surface: A DFT study. Chem. Phys. 2014, 445, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 7756–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delley, B. An all—electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delley, B. Hardness conserving semilocal pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 155125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNellis, E.R.; Meyer, J.; Reuter, K. Azobenzene at coinage metal surfaces: Role of dispersive van der Waals interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 205414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monkhorst, H.J.; Pack, J.D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5188–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumble, J. (Ed.) CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 102nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Halgren, T.A.; Lipscomb, W.N. The synchronous-transit method for determining reaction pathways and locating molecular transition states. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1977, 49, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Miao, B.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Mechanism of C–C and C–H bond cleavage in ethanol oxidation reaction on Cu2O(111): A DFT-D and DFT+U study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 26210–26220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).