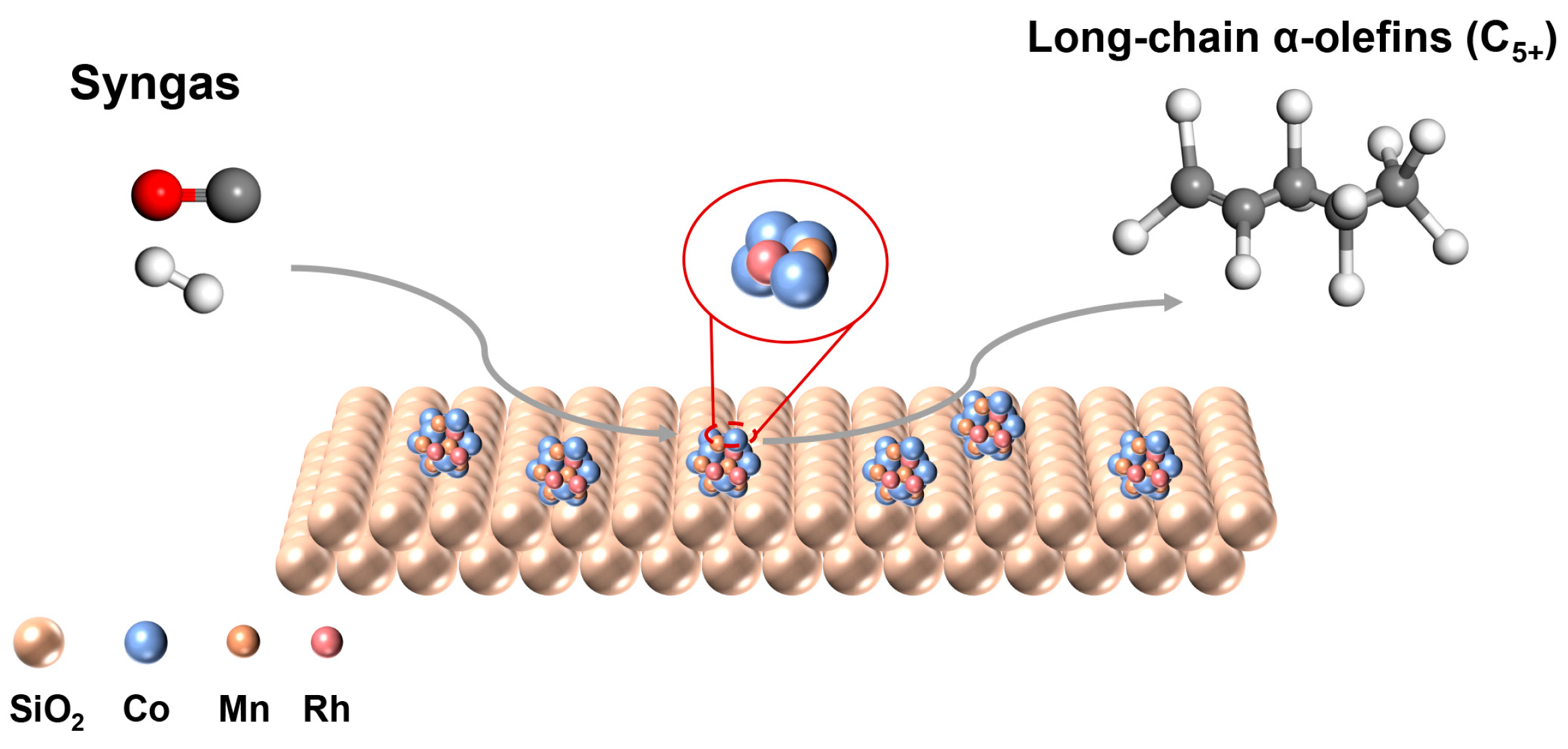

The Conversion of Syngas to Long-Chain α-Olefins over Rh-Promoted CoMnOx Catalyst

Abstract

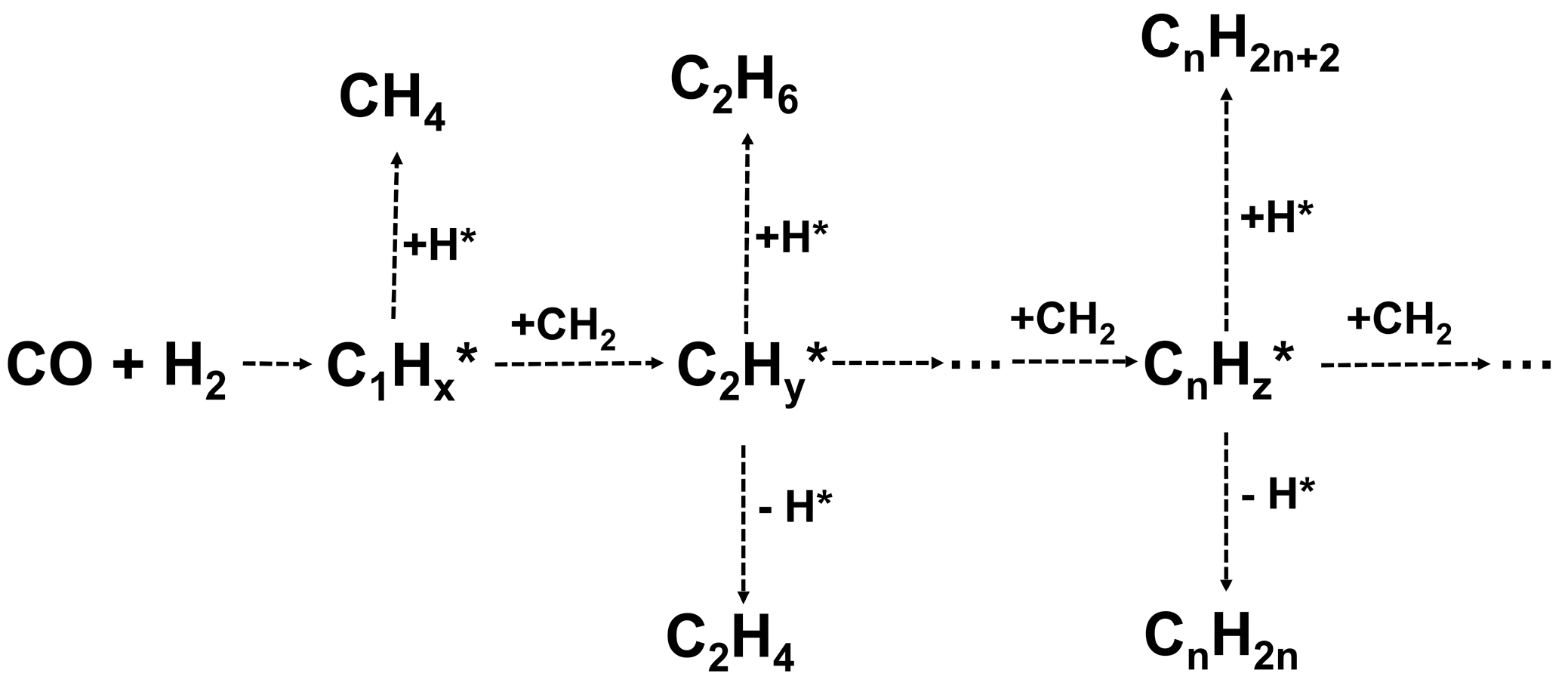

1. Introduction

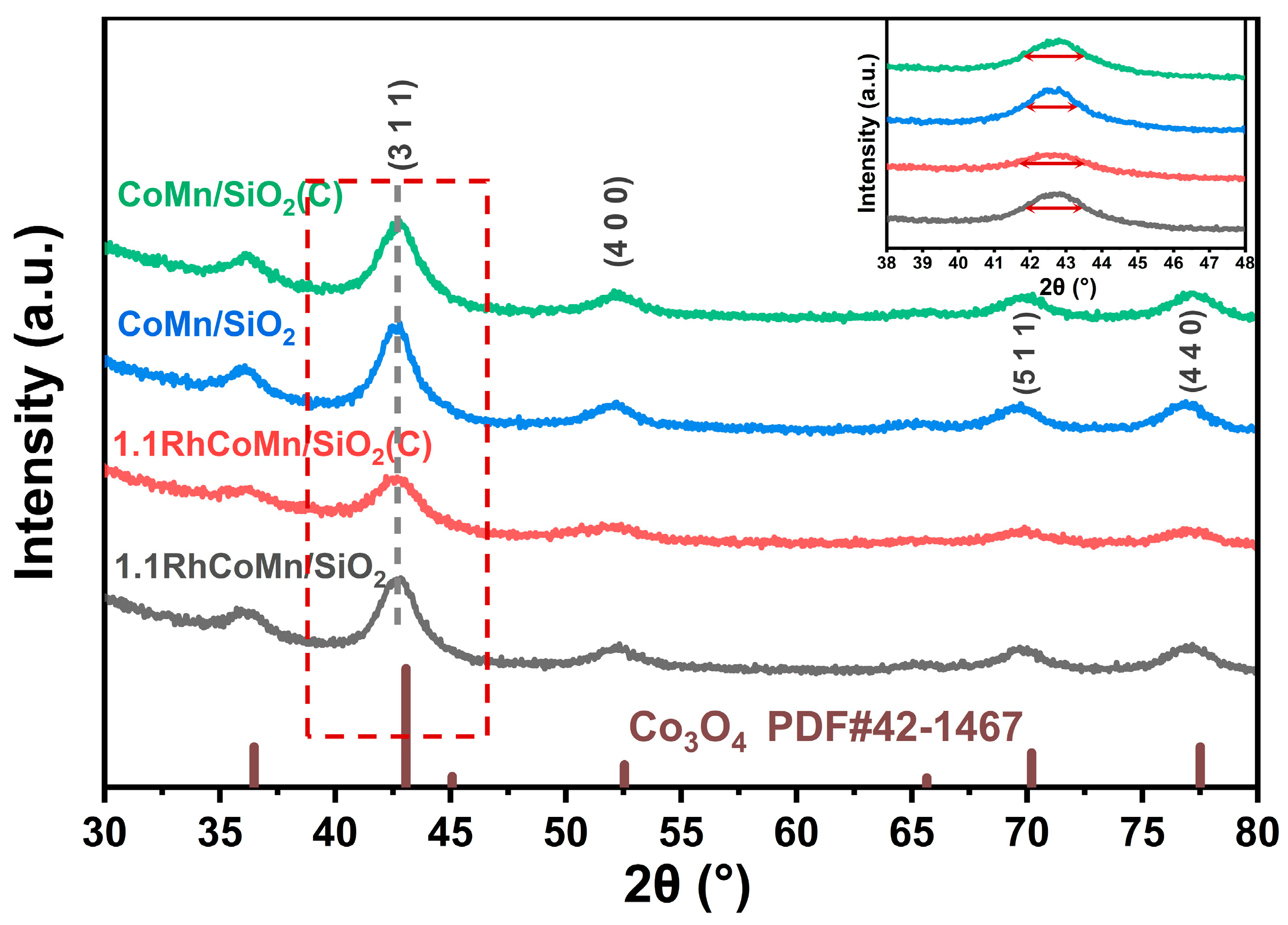

2. Results and Discussion

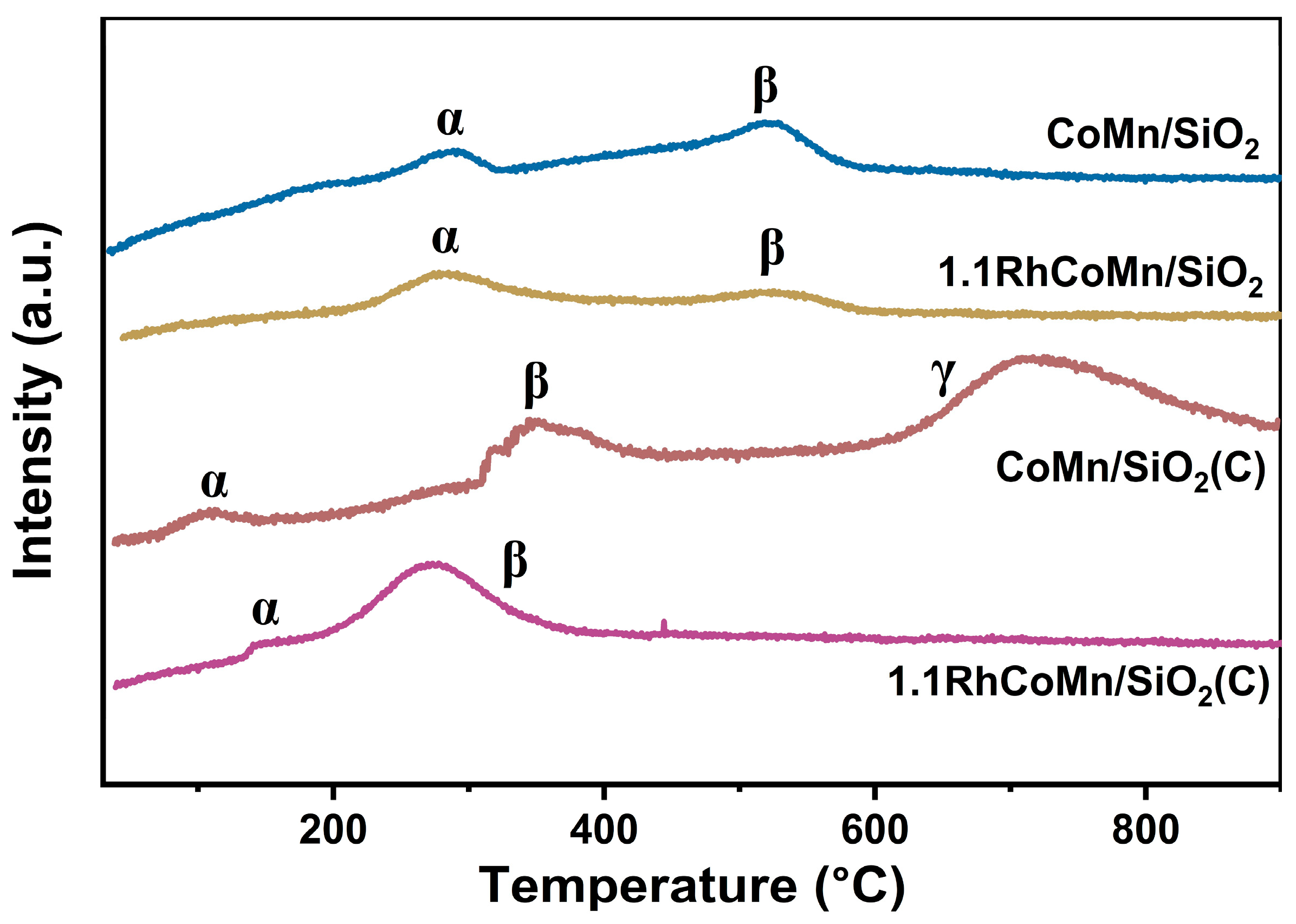

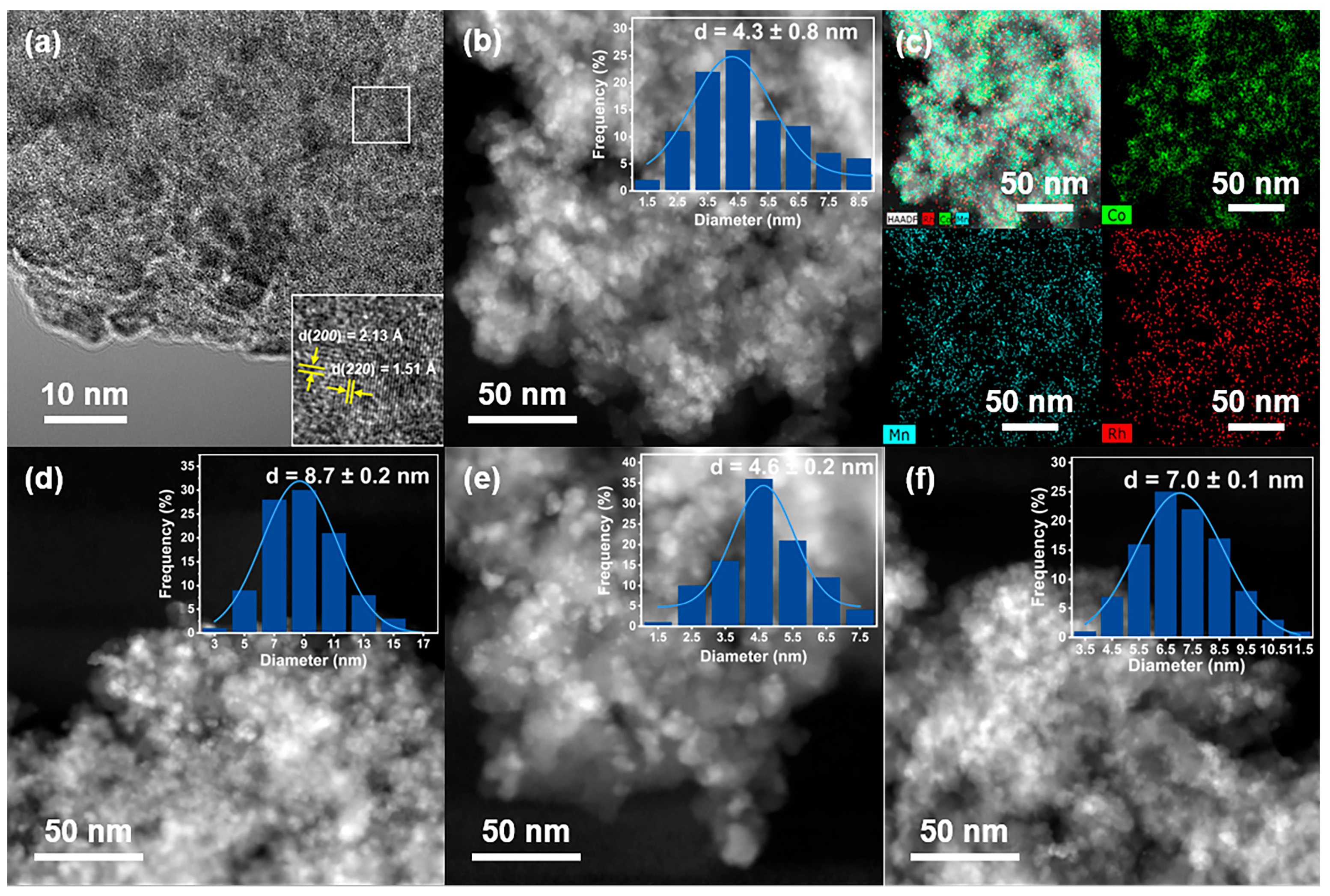

2.1. Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization

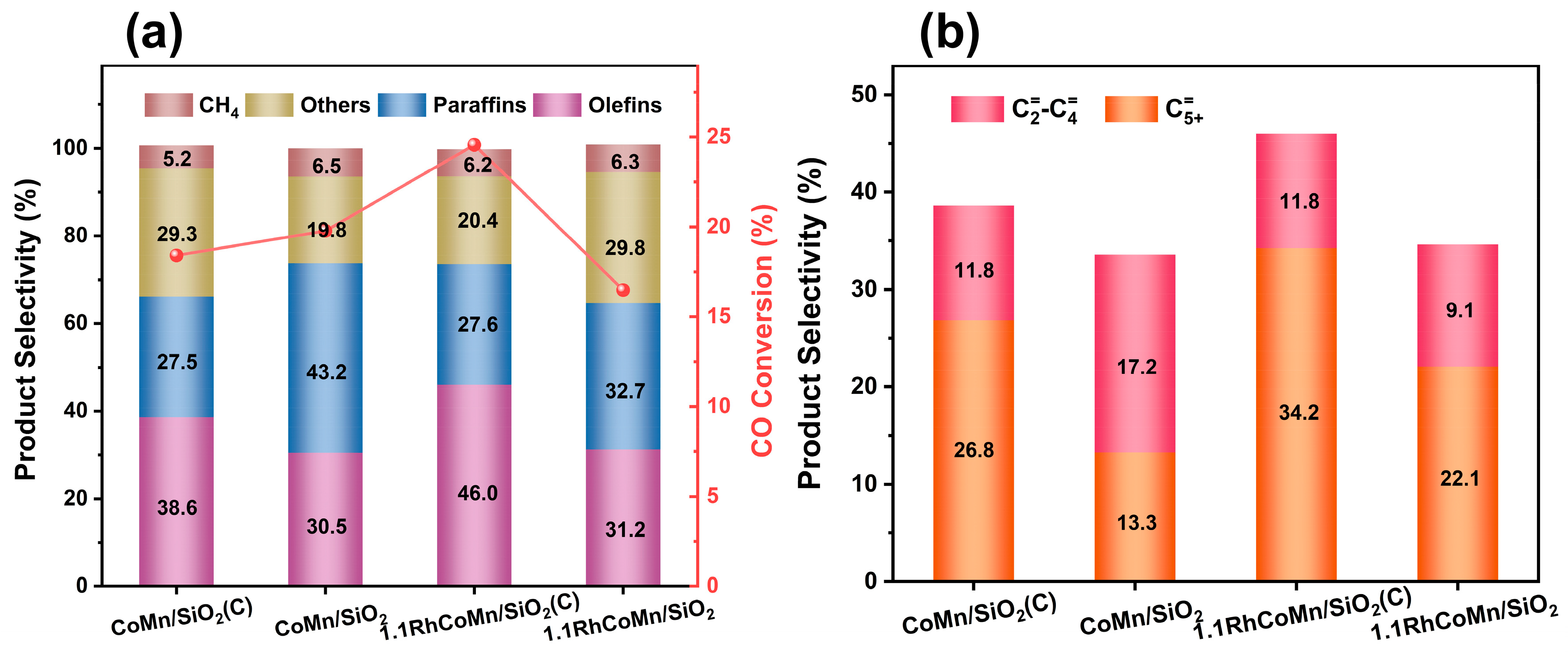

2.2. Catalytic Performance Evaluation

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis of Catalysts

3.2. Characterization Methods

3.3. Catalytic Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skupinska, J. Oligomerization of alpha-olefins to higher oligomers. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 613–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. Inorganic Solid Acids and Their Use in Acid-Catalyzed Hydrocarbon Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 559–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.-W.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Development of direct conversion of syngas to unsaturated hydrocarbons based on Fischer-Tropsch route. Chem 2021, 7, 3027–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Cheng, K.; Kang, J.; Zhou, C.; Subramanian, V.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. New horizon in C1 chemistry: Breaking the selectivity limitation in transformation of syngas and hydrogenation of CO2 into hydrocarbon chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3193–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Lin, T.; Yu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wu, M.; Sun, Y. Advances in direct production of value-added chemicals via syngas conversion. Sci. China Chem. 2017, 60, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhang, K.; He, P.; Chang, H.Y.; Zhang, M.; Yan, T.; Zhang, X.J.; Li, Y.W.; Cao, Z. Reactive Intermediate Confinement in Beta Zeolites for the Efficient Aerobic Epoxidation of α-Olefins. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202419900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, P.; Xie, Y.; Dai, Y.; Tang, K.; Huang, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, Y.; He, P.; Wang, J. Enhancement of propane activation and aromatization through DME participation over Ga modified HZSM-5. Fuel 2025, 401, 135854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, A.; Dietel, T.; Kretschmer, W.P.; Kempe, R. A broadly tunable synthesis of linear α-olefins. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, W. Oligomerization of Ethylene to α-Olefins: Discovery and Development of the Shell Higher Olefin Process (SHOP). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 12492–12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvis, H.M.T.; de Jong, K.P. Catalysts for Production of Lower Olefins from Synthesis Gas: A Review. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 2130–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förtsch, D.; Pabst, K.; Groß-Hardt, E. The product distribution in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis: An extension of the ASF model to describe common deviations. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 138, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; An, Y.; Yu, F.; Gong, K.; Yu, H.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhong, L. Advances in Selectivity Control for Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis to Fuels and Chemicals with High Carbon Efficiency. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12092–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, H. Short history and present trends of Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 1999, 186, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Kang, J.; Wang, Y. Development of Novel Catalysts for Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis: Tuning the Product Selectivity. ChemCatChem 2010, 2, 1030–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakov, A.Y.; Chu, W.; Fongarland, P. Advances in the Development of Novel Cobalt Fischer−Tropsch Catalysts for Synthesis of Long-Chain Hydrocarbons and Clean Fuels. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1692–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Q.; Gao, X.; Xia, H.; Lai, X.; Fan, S.; Zhao, T.-S. Fischer-Tropsch synthesis over methyl modified Fe2O3@SiO2 catalysts with low CO2 selectivity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 232, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Yang, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhu, M.; Han, Y.-F. Syngas to olefins with low CO2 formation by tuning the structure of FeCx-MgO-Al2O3 catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 137167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Xu, C.; Gao, R.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Li, W.; Fu, X.; Jia, C.; Xie, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. Highly Tunable Selectivity for Syngas-Derived Alkenes over Zinc and Sodium-Modulated Fe5C2 Catalyst. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9902–9907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, G.; Wen, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ding, M. A hydrophobic FeMn@Si catalyst increases olefins from syngas by suppressing C1 by-products. Science 2021, 371, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, K.; Kizilkaya, A.C.; López-Luque, I.; Pfänder, N.; Bartsch, M.; Concepción, P.; Prieto, G. Design of Cobalt Fischer–Tropsch Catalysts for the Combined Production of Liquid Fuels and Olefin Chemicals from Hydrogen-Rich Syngas. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4784–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejía, C.H.; van Deelen, T.W.; de Jong, K.P. Activity enhancement of cobalt catalysts by tuning metal-support interactions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, Z.; Tišler, Z.; Rubáš, V. Recent advances in Fischer-Tropsch synthesis using cobalt-based catalysts: A review on supports, promoters, and reactors. Catal. Rev. 2020, 63, 512–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Filot, I.A.W.; Pestman, R.; Hensen, E.J.M. Mechanism of Cobalt-Catalyzed CO Hydrogenation: 2. Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8061–8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Bell, A.T. Effects of Lewis acidity of metal oxide promoters on the activity and selectivity of Co-based Fischer–Tropsch synthesis catalysts. J. Catal. 2016, 338, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Liu, P.; Gong, K.; An, Y.; Yu, F.; Wang, X.; Zhong, L.; Sun, Y. Designing silica-coated CoMn-based catalyst for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis to olefins with low CO2 emission. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 299, 120683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Yu, F.; An, Y.; Qin, T.; Li, L.; Gong, K.; Zhong, L.; Sun, Y. Cobalt Carbide Nanocatalysts for Efficient Syngas Conversion to Value-Added Chemicals with High Selectivity. Accounts Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.Ø.; Svenum, I.-H.; Blekkan, A. Mn promoted Co catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch production of light olefins – An experimental and theoretical study. J. Catal. 2018, 361, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltes, T.E.; Espinosa-Alonso, L.; de Smit, E.; D’sOuza, L.; Meyer, R.J.; Weckhuysen, B.M.; Regalbuto, J.R. Selective adsorption of manganese onto cobalt for optimized Mn/Co/TiO2 Fischer–Tropsch catalysts. J. Catal. 2010, 270, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, G.; Radstake, P.; Falke, U.; Oosterbeek, H.; Kuipers, H.; Vandillen, A.; Dejong, K. Investigation of promoter effects of manganese oxide on carbon nanofiber-supported cobalt catalysts for Fischer–Tropsch synthesis. J. Catal. 2006, 237, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Contreras, H.G.; Martínez-Hernández, A.; Boix, A.A.; Fuentes, G.A.; Torres-García, E. Effect of Mn on Co/HMS-Mn and Co/SiO2-Mn catalysts for the Fischer-Tropsch reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 244, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, D.M.; Johnson, G.R.; Bustillo, K.C.; Bell, A.T. Scanning Nanobeam Diffraction and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy Characterization of a Model Mn-Promoted Co/Al2O3 Nanosphere Catalyst for Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12071–12079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, G.L.; Bitter, J.H.; Kuipers, H.P.C.E.; Oosterbeek, H.; Holewijn, J.E.; Xu, X.; Kapteijn, F.; van Dillen, A.J.; de Jong, K.P. Cobalt Particle Size Effects in the Fischer−Tropsch Reaction Studied with Carbon Nanofiber Supported Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3956–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, F.; Grandjean, D.; de Groot, F.M.F.; Stephan, O.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Combined EXAFS and STEM-EELS study of the electronic state and location of Mn as promoter in Co-based Fischer–Tropsch catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Sun, X.; Jin, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Song, F.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Zhao, T.; et al. Microstructure Evolution of a Co/MnO Catalyst for Fischer-Tropsch Synthesis Revealed by In Situ XAFS Studies. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinse, A.; Aigner, M.; Ulbrich, M.; Johnson, G.R.; Bell, A.T. Effects of Mn promotion on the activity and selectivity of Co/SiO2 for Fischer–Tropsch Synthesis. J. Catal. 2012, 288, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.-L.; Liu, X.; Niu, Y.; Yang, G.-Q.; Bao, J.; Song, Y.-H.; Yan, Y.-F.; Du, N.; Shui, M.-L.; Zhu, K.; et al. Long-chain α-olefins production over Co-MnOx catalyst with optimized interface. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2024, 346, 123783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Fan, Q.-Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Q.; He, S.; Yue, L.; Tang, Y.; Nguyen, L.; Yu, X.; You, Y.; et al. Iridium boosts the selectivity and stability of cobalt catalysts for syngas to liquid fuels. Chem 2022, 8, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; He, P. Boosting the Production of Glycolic Acid from Formaldehyde Carbonylation via the Bifunctional PdO/ZSM-5 Catalyst. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 17671–17680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, T.; Hou, H.; Yin, J.; Wan, H.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, F.; Wei, Y.; Dong, M.; et al. Regioselective hydroformylation of propene catalysed by rhodium-zeolite. Nature 2024, 629, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, B.; Qin, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; et al. High-Density W Single Atoms in Two-Dimensional Spinel Oxide Break the Structural Integrity for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 32249–32262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y.; Ma, K.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Tian, Z.; Kang, Z.; et al. Identifying and Interpreting Geometric Configuration-Dependent Activity of Spinel Catalysts for Water Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 19163–19172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.J.; Klabunde, K.J.; Sherwood, P.M.A. XPS studies of solvated metal atom dispersed (SMAD) catalysts. Evidence for layered cobalt-manganese particles on alumina and silica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Li, R.; Qu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Wang, J.; Du, X.; Liu, C.; Feng, X.; Ning, Y.; Mu, R.; et al. Oxide Support Inert in Its Interaction with Metal but Active in Its Interaction with Oxide and Vice Versa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 13210–13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.X.; Wang, Z.L.; Lin, T.G.; Zhu, X.B.; Luo, B.; Hu, H.; Xing, W.; Yan, Z.F.; Wang, L.Z. Lithiation-Induced Vacancy Engineering of Co3O4 with Improved Faradic Reactivity for High-Performance Supercapacitor. Adv. Func. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Hou, H.; Wu, C.; Cai, Y.; Yin, A.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, P.; Xu, J. Unraveling the molecular mechanism for enhanced gas adsorption in mixed-metal MOFs via solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2312959121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Lv, L.; Ding, Y.; Tian, D.; Wang, S. Insights into the Reactive and Deactivation Mechanisms of Manganese Oxides for Ozone Elimination: The Roles of Surface Oxygen Species. Langmuir 2021, 37, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, G.; Martínez, A.; Concepción, P.; Moreno-Tost, R. Cobalt particle size effects in Fischer–Tropsch synthesis: Structural and in situ spectroscopic characterisation on reverse micelle-synthesised Co/ITQ-2 model catalysts. J. Catal. 2009, 266, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulavchenko, O.A.; Afonasenko, T.N.; Ivanchikova, A.; Murzin, V.Y.; Kremneva, A.M.; Saraev, A.A.; Kaichev, V.V.; Tsybulya, S. In Situ Study of Reduction of MnxCo3-xO4 Mixed Oxides: The Role of Manganese Content. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 16518–16528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.H.; Cheong, J.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Shim, Y.S.; Park, J.Y.; Seo, H.K.; Dae, K.S.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, I.D.; Yuk, J.M. Graphene Liquid Cell Electron Microscopy of Initial Lithiation in Co3O4 Nanoparticles. Acs Omega 2019, 4, 6784–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Du, G. Revealing the electrochemical conversion mechanism of porous Co3O4 nanoplates in lithium ion battery by in situ transmission electron microscopy. Nano Energy 2014, 9, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dou, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hou, H.; Meira, D.M.; Liu, L.; He, P. Tuning the size and spatial distribution of Pt in bifunctional Pt-zeolite catalysts for direct coupling of ethane and benzene. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lögdberg, S.; Lualdi, M.; Järås, S.; Walmsley, J.C.; Blekkan, A.; Rytter, E.; Holmen, A. On the selectivity of cobalt-based Fischer–Tropsch catalysts: Evidence for a common precursor for methane and long-chain hydrocarbons. J. Catal. 2010, 274, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

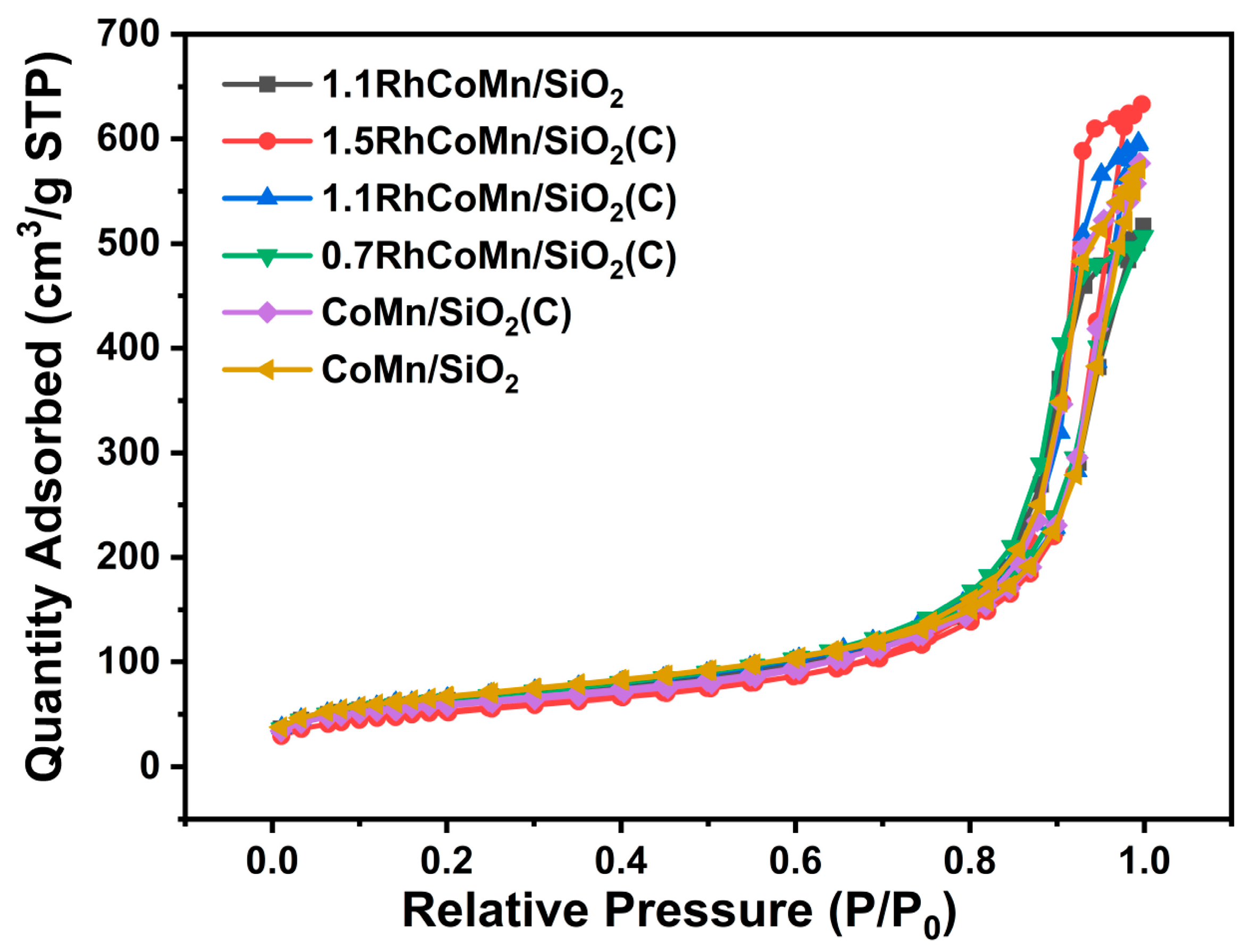

| Catalysts | Surface Area (m2·g−1) | ICP Elemental Analysis (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | External | Micro | Co | Mn | Rh | |

| CoMn/SiO2 | 222 | 174 | 48 | 13.0 | 0.25 | |

| CoMn/SiO2(C) | 190 | 165 | 25 | 12.9 | 0.25 | |

| 0.7RhCoMn/SiO2(C) | 228 | 185 | 43 | 12.9 | 0.24 | 0.69 |

| 1.1RhCoMn/SiO2(C) | 229 | 194 | 35 | 13.0 | 0.25 | 1.10 |

| 1.5RhCoMn/SiO2(C) | 213 | 165 | 48 | 13.2 | 0.26 | 1.53 |

| 1.1RhCoMn/SiO2 | 238 | 184 | 54 | 13.1 | 0.26 | 1.11 |

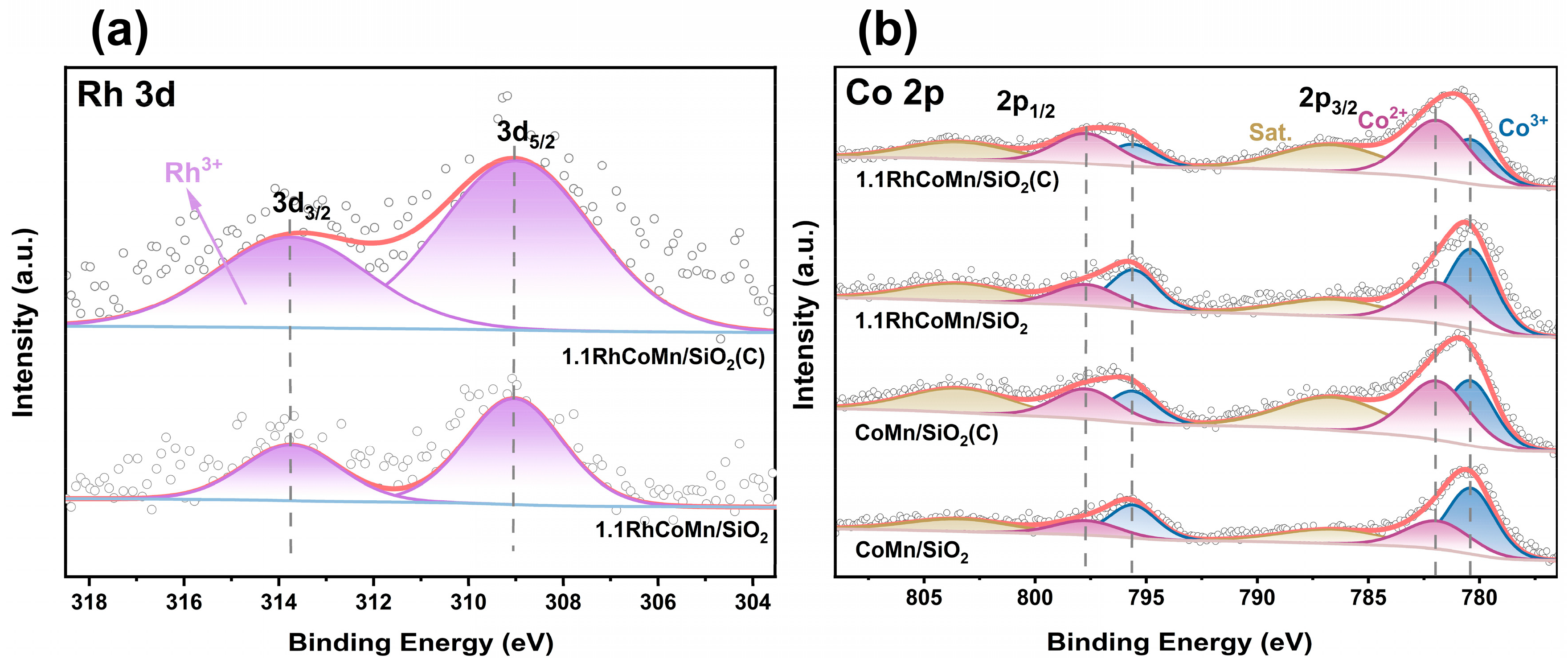

| Catalysts | Co2+ Area (%) | Co3+ Area (%) | Co2+/Co3+ Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoMn/SiO2 | 36 | 64 | 1:1.8 |

| CoMn/SiO2(C) | 55 | 45 | 1.2:1 |

| 1.1RhCoMn/SiO2 | 41 | 59 | 1:1.5 |

| 1.1RhCoMn/SiO2(C) | 64 | 36 | 1.8:1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, Y.; Cao, X.; Qian, F.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; He, P.; Cao, Z.; Song, C. The Conversion of Syngas to Long-Chain α-Olefins over Rh-Promoted CoMnOx Catalyst. Catalysts 2025, 15, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121122

Dai Y, Cao X, Qian F, Li X, Zhang L, He P, Cao Z, Song C. The Conversion of Syngas to Long-Chain α-Olefins over Rh-Promoted CoMnOx Catalyst. Catalysts. 2025; 15(12):1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121122

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Yuting, Xuemin Cao, Fei Qian, Xia Li, Li Zhang, Peng He, Zhi Cao, and Chang Song. 2025. "The Conversion of Syngas to Long-Chain α-Olefins over Rh-Promoted CoMnOx Catalyst" Catalysts 15, no. 12: 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121122

APA StyleDai, Y., Cao, X., Qian, F., Li, X., Zhang, L., He, P., Cao, Z., & Song, C. (2025). The Conversion of Syngas to Long-Chain α-Olefins over Rh-Promoted CoMnOx Catalyst. Catalysts, 15(12), 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal15121122