Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay to Assess Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Melanoma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Study Design

2.2. Biospecimen Collection

2.3. Personalized ctDNA Assay Using Multiplex PCR-Based NGS Workflow

2.4. Statistical Analysis

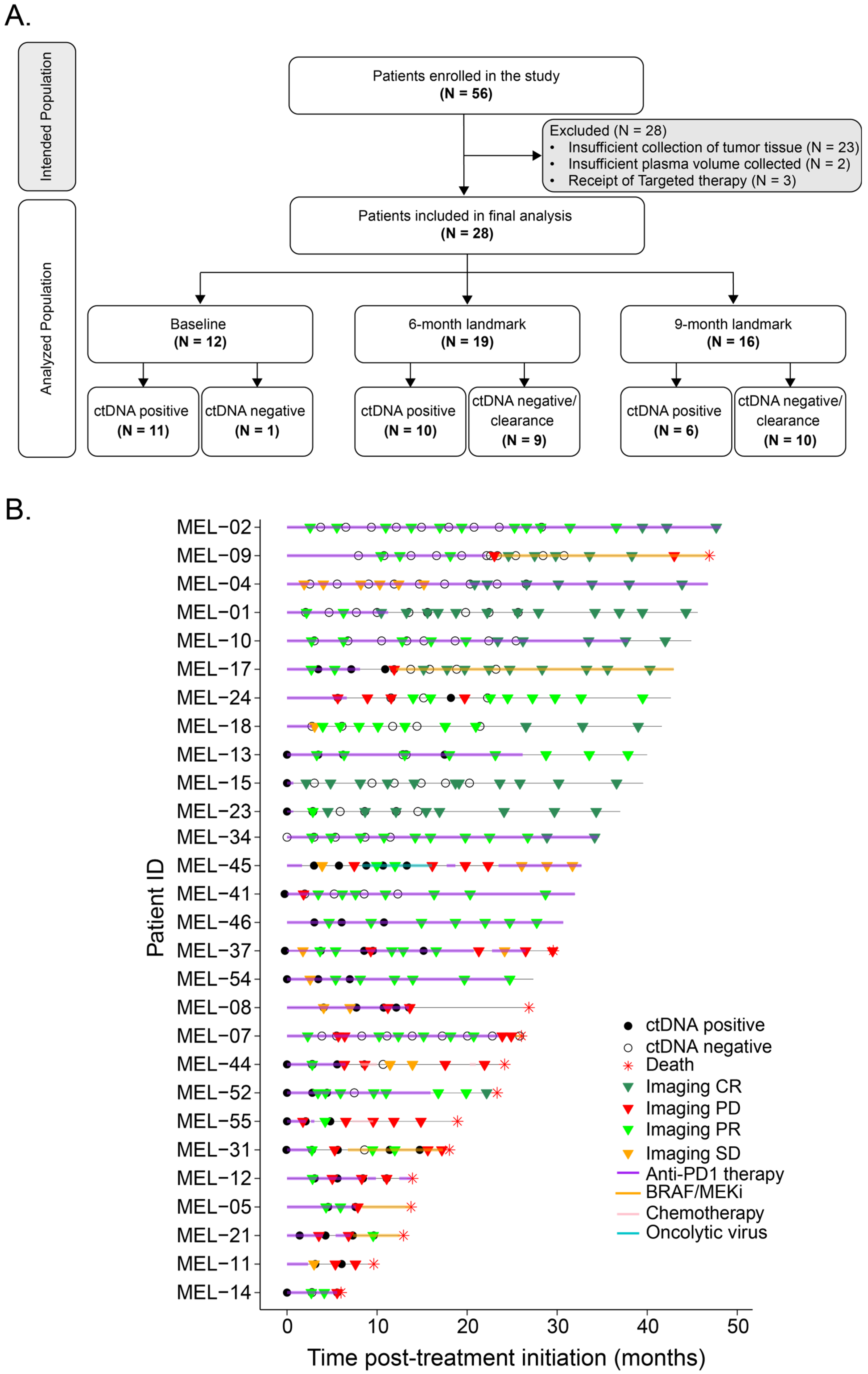

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Tumor Characteristics

3.2. ctDNA Dynamics Are Predictive of Response to First-Line Anti-PD-1-Based Treatment

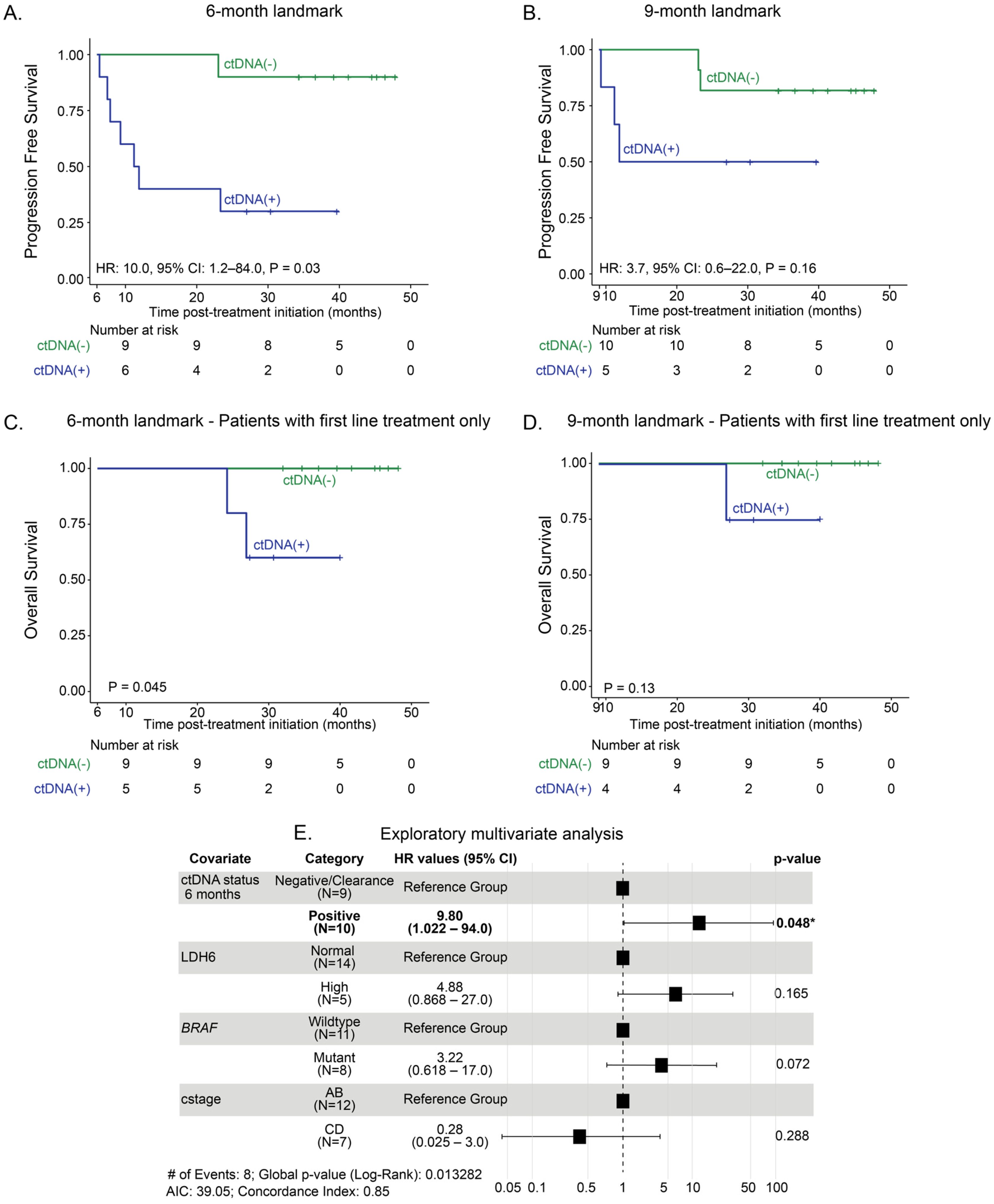

3.3. Landmark Analysis at 6 Months and 9 Months: Association Between ctDNA Status and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Anti-PD-1-Based Therapy

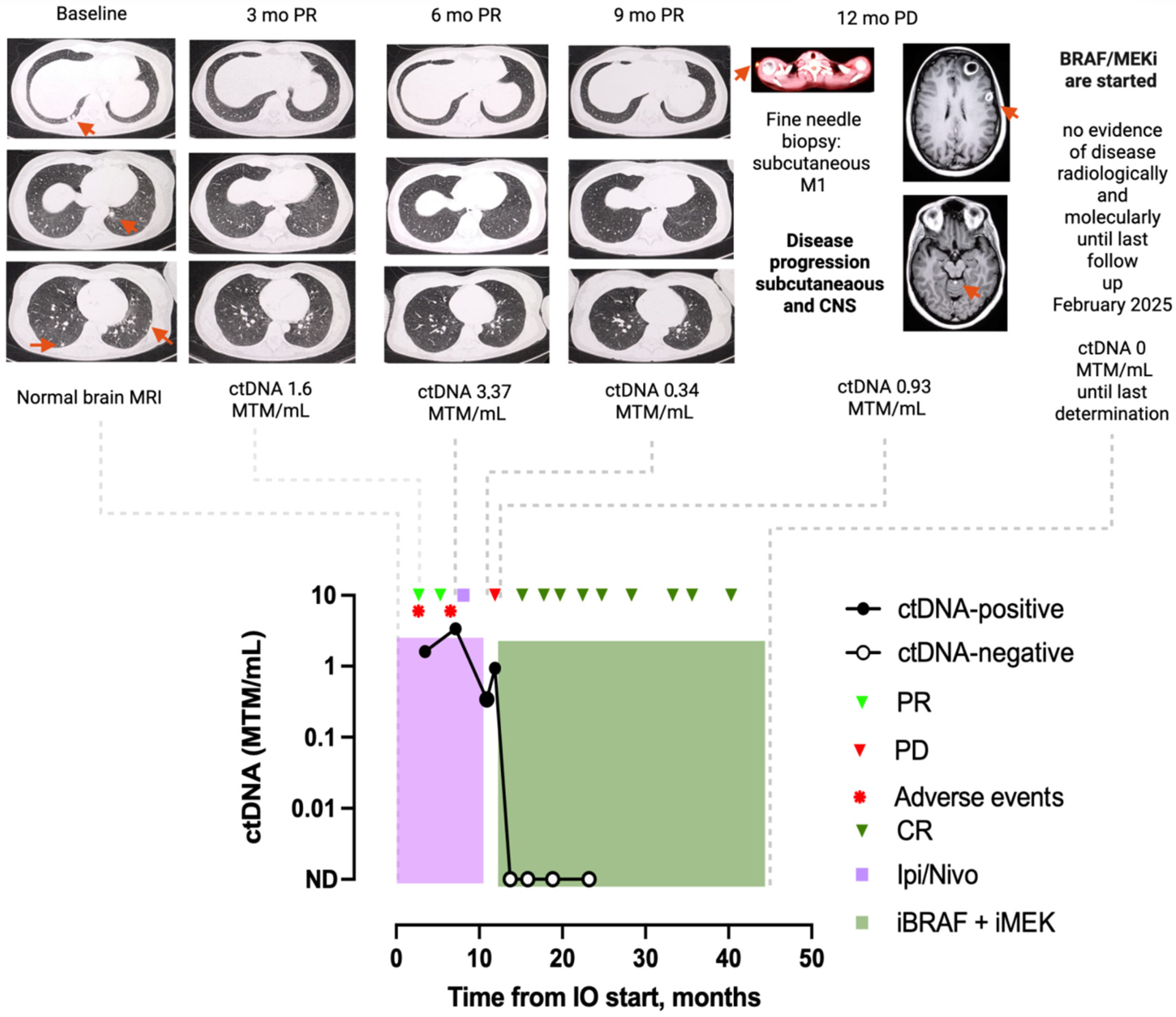

3.4. Clinical Case Examples

3.4.1. Patient 1: Case MEL-17

3.4.2. Patient 2: Case MEL-15

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| MRD | Molecular residual disease |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD-1 | programmed cell death-1 |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte activation gene 3 |

| irAEs | Immune-related adverse events |

| CR | Complete response |

| PR | Partial response |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| SD | Stable disease |

| FFPE | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| WES | Whole-exome sequencing |

References

- Ascierto, P.A.; Long, G.V.; Robert, C.; Brady, B.; Dutriaux, C.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; Mortier, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Rutkowski, P.; McNeil, C.; et al. Survival Outcomes in Patients with Previously Untreated BRAF Wild-Type Advanced Melanoma Treated with Nivolumab Therapy: Three-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Phase 3 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 187–194, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4514; Erratum in JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Carlino, M.S.; McNeil, C.; Ribas, A.; Grob, J.J.; Schachter, J.; Nyakas, M.; Kee, D.; Petrella, T.M.; Blaustein, A.; et al. Seven-Year Follow-Up of the Phase III KEYNOTE-006 Study: Pembrolizumab Versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3998–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Queirolo, P.; Dummer, R.; Butler, M.O.; Hill, A.G.; et al. CheckMate 067 Investigators. Final, 10-Year Outcomes with Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, E.J.; Stephen Hodi, F.; Tawbi, H.; Schadendorf, D.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Gutierrez, E.C.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; et al. Nivolumab plus relatlimab in advanced melanoma: RELATIVITY-047 4-year update. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 225, 115547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, T.; Ottaviano, M.; Arance, A.; Blank, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Donia, M.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Gogas, H.; et al. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guideline Melanoma: Cutaneous; Version 2.2025; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025.

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; Brochez, L.; Del Marmol, V.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment—Update 2024. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 215, 115153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitmajer, M.; Flatz, L. Precision medicine in cutaneous melanoma—A comprehensive review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 37, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmamed, M.F.; Fernandez-Landazuri, S.; Rodriguez, C.; Zarate, R.; Lozano, M.D.; Zubiri, L.; Perez-Gracia, J.L.; Martin-Algarra, S.; Gonzalez, A. Quantitative cell- free circulating BRAFV600E mutation analysis by use of droplet digital PCR in the follow-up of patients with melanoma being treated with BRAF inhibitors. Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Long, G.V.; Boyd, S.; Lo, S.; Menzies, A.M.; Tembe, V.; Guminski, A.; Jakrot, V.; Scolyer, R.A.; Mann, G.J.; et al. Circulating tumour DNA predicts response to anti-PD1 antibodies in metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seremet, T.; Jansen, Y.; Planken, S.; Njimi, H.; Delaunoy, M.; El Housni, H.; Awada, G.; Schwarze, J.K.; Keyaerts, M.; Everaert, H.; et al. Undetectable circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels correlate with favorable outcome in metastatic melanoma patients treated with anti-PD1 therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cao, M.; Mayo de Las Casas, C.; Jordana Ariza, N.; Manzano, J.L.; Molina-Vila, M.Á.; Soriano, V.; Puertolas, T.; Balada, A.; Soria, A.; Majem, M.; et al. Early evolution of BRAFV600 status in the blood of melanoma patients correlates with clinical outcome identifies patients refractory to therapy. Melanoma Res. 2018, 28, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vila, C.; Teixido, C.; Aya, F.; Martín, R.; González-Navarro, E.A.; Alos, L.; Castrejon, N.; Arance, A. Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA in Liquid Biopsy: Current Techniques and Potential Applications in Melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaini, M.C.; Catoni, C.; Poggiana, C.; Pigozzo, J.; Piccin, L.; Leone, K.; Scarabello, I.; Facchinetti, A.; Menin, C.; Elefanti, L.; et al. A multiparameter liquid biopsy approach allows to track melanoma dynamics and identify early treatment resistance. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.; Ramtohul, T.; Rampanou, A.; Sandoval, J.L.; Houy, A.; Servois, V.; Mailly-Giacchetti, L.; Pierron, G.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Cassoux, N.; et al. Prospective assessment of circulating tumor DNA in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma treated with tebentafusp. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlan, F.; Blanchet, B.; Kramkimel, N.; Puszkiel, A.; Golmard, J.L.; Noe, G.; Dupin, N.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Vidal, M.; Taly, V.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Measurement by Picoliter Droplet-Based Digital PCR and Vemurafenib Plasma Concentrations in Patients with Advanced BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. Target. Oncol. 2017, 12, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Stewart, A.; Diefenbach, R.J.; Gonzalez, M.; Menzies, A.M.; Blank, C.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Rizos, H. Circulating tumour DNA dynamics predict recurrence in stage III melanoma patients receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.M.; Long, G.V.; Garrett, J.; Atkinson, V.; Santinami, M.; Schadendorf, D.; Hauschild, A.; Millward, M.; Mandala, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; et al. Clinical validation of droplet digital PCR assays in detecting BRAFV600-mutant circulating tumour DNA as a prognostic biomarker in patients with resected stage III melanoma receiving adjuvant therapy (COMBI-AD): A biomarker analysis from a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, C.; Gatidis, S.; Kelemen, O.; Schütz, L.; Bonzheim, I.; Muyas, F.; Martus, P.; Admard, J.; Armeanu-Ebinger, S.; Gückel, B.; et al. Tumour-informed liquid biopsies to monitor advanced melanoma patients under immune checkpoint inhibition. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forschner, A.; Battke, F.; Hadaschik, D.; Schulze, M.; Weißgraeber, S.; Han, C.T.; Kopp, M.; Frick, M.; Klumpp, B.; Tietze, N.; et al. Tumor mutation burden and circulating tumor DNA in combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma—Results of a prospective biomarker study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbreteau, G.; Vallée, A.; Knol, A.C.; Théoleyre, S.; Quéreux, G.; Varey, E.; Khammari, A.; Dréno, B.; Denis, M.G. Circulating Tumor DNA Early Kinetics Predict Response of Metastatic Melanoma to Anti-PD1 Immunotherapy: Validation Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, G.V.; Tang, H.; Desai, K.; Wang, S.; Del Vecchio, M.; Larkin, J.; Ritchings, C.; Huang, S.P.; Baden, J.; Balli, D.; et al. Pretreatment and on-treatment ctDNA and tissue biomarkers predict recurrence in patients with stage IIIB–D/IV melanoma treated with adjuvant immunotherapy: CheckMate 915. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genta, S.; Araujo, D.V.; Hueniken, K.; Pipinikas, C.; Ventura, R.; Rojas, P.; Jones, G.; Butler, M.O.; Saibil, S.D.; Yu, C.; et al. Bespoke ctDNA for longitudinal detection of molecular residual disease in high-risk melanoma patients. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, S.V.; Yang, S.Y.C.; Iafolla, M.A.J.; Liu, Z.; Hansen, A.R.; Bedard, P.L.; Lheureux, S.; Spreafico, A.; Razak, A.A.; Shchegrova, S.; et al. Personalized circulating tumor DNA analysis as a predictive biomarker in solid tumor patients treated with pembrolizumab. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Z.; Krinshpun, S.; Kalashnikova, E.; Sudhaman, S.; Ozturk Topcu, T.; Nichols, M.; Martin, J.; Bui, K.M.; Palsuledesai, C.C.; Malhotra, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA-based molecular residual disease detection for treatment monitoring in advanced melanoma patients. Cancer 2023, 129, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, T.; Henriksen, T.V.; Christensen, E.; Sharma, S.; Salari, R.; Sethi, H.; Knudsen, M.; Nordentoft, I.; Wu, H.T.; Tin, A.S.; et al. Analysis of Plasma Cell-Free DNA by Ultradeep Sequencing in Patients with Stages I to III Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1124–1131, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0528; Erratum in JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Attard, G.; Bidard, F.C.; Curigliano, G.; De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Diehn, M.; Italiano, A.; Lindberg, J.; Merker, J.D.; Montagut, C.; et al. ESMO recommendations on the use of circulating tumour DNA assays for patients with cancer: A report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.M.; Wiggins, J.M.; Corless, B.C.; Long, G.V.; Flaherty, K.T.; Schadendorf, D.; Nathan, P.D.; Robert, C.; Ribas, A.; Davies, M.A.; et al. Circulating tumour DNA in patients with advanced melanoma treated with dabrafenib or dabrafenib plus trametinib: A clinical validation study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Walker, A.; Gagnon, R.; Mazumdar, J.; Casey, M.; Long, G.V.; Schadendorf, D.; Flaherty, K.; Kefford, R.; Hauschild, A.; Hwu, P.; et al. Correlation of BRAF Mutation Status in Circulating-Free DNA and Tumor and Association with Clinical Outcome across Four BRAFi and MEKi Clinical Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.R.M.; Karasaki, T.; Abbott, C.W.; Li, B.; Veeriah, S.; Al Bakir, M.; Liu, W.K.; Huebner, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, C.; Pawlik, P.; et al. Longitudinal ultrasensitive ctDNA monitoring for high-resolution lung cancer risk prediction. Cell 2025, 188, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic, N (%) | Analyzed, N = 28 | Enrolled, N = 56 | p Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 63.61 (29–98) | 66.54 (29–98) | 0.085 |

| Sex, male | 12 (42.9) | 27 (48.2) | 0.926 |

| ECOG 2 | 0.087 | ||

| 0 | 18 (64.3) | 35 (62.5) | |

| 1 | 10 (35.7) | 18 (32.1) | |

| 2 | 0 (0) | 3 (5.4) | |

| M stage (AJCCv8) | 0.0612 | ||

| IVA | 11 (39.3) | 16 (28.6) | |

| IVB | 6 (21.4) | 9 (16.1) | |

| IVC | 4 (14.3) | 16 (28.8) | |

| IVD | 7 (25) | 15 (26.8) | |

| Number of disease sites | 0.289 | ||

| <3 | 23 (82.1) | 40 (71.4) | |

| ≥3 | 5 (17.9) | 16 (28.6) | |

| LDH levels | 0.233 | ||

| ≤ULN 3 | 21 (75) | 40 (71.4) | |

| >ULN | 7 (25) | 16 (28.6) | |

| Mutational status 4 | |||

| BRAF-non mutant | 16 (57.1) | 33 (58.9) | 0.684 |

| BRAFV600 | 12 (42.9) | 22 (39.3) | 0.677 |

| NRAS mutant | 5 (27.8) | 12 (21.4) | 0.397 |

| Efficacy 5 | 0.0177 | ||

| SD | 3 (10.7) | 6 (10.7) | |

| PR | 15 (53.5) | 29 (51.8) | |

| CR | 7 (25) | 11 (19.6) | |

| PD | 3 (10.7) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Current treatment | 0.575 | ||

| AntiPD1 + antiCTLA4 | 12 (42.9) | 18 (32.1) | |

| AntiPD1 + other | 7 (25) | 14 (25) | |

| AntiPD1 alone | 9 (32.1) | 21 (37.5) | |

| BRAF/MEKi | 0 (0) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Previous anti-PD1-based therapy | 0.454 | ||

| Adjuvant setting | 5 (100) | 9 (75) | |

| Metastatic setting | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | |

| Previous BRAF/MEKi therapy | 0.743 | ||

| Adjuvant setting | 1 (12.5) | 1 (10) | |

| Metastatic setting | 7 (87.5) | 9 (90) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Vila, C.; Teixido, C.; Martín, R.; Aya, F.; Sudhaman, S.; Budde, G.L.; González-Navarro, E.A.; Alos, L.; Castrejon, N.; Ortiz, J.B.; et al. Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay to Assess Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233804

Martínez-Vila C, Teixido C, Martín R, Aya F, Sudhaman S, Budde GL, González-Navarro EA, Alos L, Castrejon N, Ortiz JB, et al. Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay to Assess Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233804

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Vila, Clara, Cristina Teixido, Roberto Martín, Francisco Aya, Sumedha Sudhaman, Griffin L. Budde, Europa Azucena González-Navarro, Llucia Alos, Natalia Castrejon, J. Bryce Ortiz, and et al. 2025. "Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay to Assess Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Melanoma" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233804

APA StyleMartínez-Vila, C., Teixido, C., Martín, R., Aya, F., Sudhaman, S., Budde, G. L., González-Navarro, E. A., Alos, L., Castrejon, N., Ortiz, J. B., Krainock, M., Liu, M. C., & Arance, A. (2025). Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay to Assess Long-Term Clinical Benefit in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. Cancers, 17(23), 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233804