Abstract

Background: Dementia is a growing global public health concern and identifying modifiable risk and protective factors is crucial for its prevention. Fruits and vegetables, due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, may offer neuroprotective benefits. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of adequate fruit and vegetable consumption and its association with dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) in individuals aged 50 years and older. Methods: This cross-sectional, population-based study analysed data from 2865 participants in the second wave (2019–2021) of the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSI-Brazil). CIND was defined as a global cognitive Z-score ≤ −1.5, and dementia as cognitive decline with impairment in at least one instrumental activity of daily living. Adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and both combined (FV) was defined as daily intake on all seven days of the week. Associations were assessed using multivariate Poisson regression models, with prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Results: The study sample consisted of 2865 participants. The prevalence of adequate fruit consumption was 58.08% (95% CI: 56.3–59.9), vegetables 44.14% (95% CI: 42.31–45.9), and FV 32.18% (95% CI: 30.5–33.9). Adequate vegetable consumption was significantly associated with CIND (PR: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.07–0.50; p < 0.001), while adequate fruit consumption was associated with higher prevalence of CIND (PR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.22–1.77) and FV (PR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.07–1.58; p = 0.003). No significant association was observed between fruit, vegetable, and FV consumption and dementia. Conclusions: Adequate vegetable and combined FV consumption were protective against CIND, though not associated with dementia. Nonetheless, overall adequate intake remains low in older Brazilian adults.

1. Introduction

The ageing process is a global and complex issue in public policy related to geriatrics, driven by an increase in age-related diseases such as neurodegenerative conditions, notably dementias [1,2,3]. The decline of cognitive functions characterises cognitive impairment, which can progress into various types of dementia [4,5]. Currently, around 55 million people are affected by dementia, and projections suggest that by 2050, this number could rise to 139 million cases [6].

Several factors are associated with an increased risk of dementia, including diabetes, hypertension, low education levels, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol abuse, traumatic brain injury, air pollution, dietary habits, and low social participation [7,8,9,10]. However, food consumption variables are less studied but hold significant potential as both risk and protective factors for dementia, particularly fruits and vegetables, because of their rich content of vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols that may help prevent dementia [10,11,12,13].

Vitamins and polyphenols found in fruits and vegetables play a crucial role in reducing neurotoxicity and mitigating free radical damage, thereby reducing oxidative stress. These compounds act as natural anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic agents, in addition to improving cerebral perfusion. These effects contribute to improved cognitive function, including memory, locomotor speed, sensory processing, and information processing [14,15,16].

There are a few studies worldwide exploring the association of fruit and vegetable consumption with dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) in older adults [17,18,19,20,21]. In Brazil, only one study examined the possible association with cognitive performance [22]. Given the biological plausibility of the neuroprotective effects of fruits and vegetables and the scarcity of evidence in South America, we hypothesised that adequate daily consumption would act as a protective factor against dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND). Therefore, the objectives of this research were: (I) to describe the prevalence of adequate fruit and vegetable consumption; (II) to investigate their association with dementia and CIND in individuals aged 50 years and older.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional design using data from a nationally representative survey on the ageing of the Brazilian population aged 50 years and over, the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSI-Brazil) [23]. Data from the second wave (2019–2021) were analysed, comprising 9949 participants residing in rural and urban areas across the five regions of Brazil. Data collection was carried out through individual home interviews, using questionnaires that addressed sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, physical and mental health, as well as physical tests and measurements [24].

Individuals aged 50 years and older were selected, including those who responded directly or whose answers were provided by a family member or close friend. Participants who reported having or using medications for Parkinson’s disease or severe psychiatric disorders were excluded, as well as those who answered “I do not know” or did not respond to questions related to cognitive function.

2.2. Sociodemographic Variables

The sociodemographic variables analysed included sex, age, self-reported race/skin colour, income, and education. Sex was categorised as female or male. Age was stratified into three groups: 50–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years or older. Self-declared skin colour was classified according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics as White, Brown, and Black/Others, with “Others” being individuals who identified as Asian or Indigenous due to the small sample size. Individual income was divided into quartiles of 25%, using the detailed command variable for classification. Education was categorised into three groups: illiterate (no formal education), up to elementary school (up to seven years of study), and high school or higher education (eight or more years of study).

2.3. Lifestyle Variables

Lifestyle variables included living with a partner (yes or no), smoking (never smoker and former/current smoker), and excessive alcohol consumption (weekly intake of ≥14 standard drinks or four standard drinks per day for men, and ≥7 standard drinks per week or three standard drinks per day for women) [25]. Sedentary behaviour was defined as an inactive level of physical activity, involving individuals who engaged in walking and moderate/vigorous exercise for less than 150 min per week [26].

2.4. Morbidities

Obesity was defined according to Silveira et al. (2020) [27], who evaluated the accuracy of BMI cut-off points for older adults in Brazil, a population comparable to this study. In this model, obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 for men and BMI ≥ 26.6 kg/m2 for women [27]. Systemic arterial hypertension was diagnosed based on systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure measurements ≥ 140/90 mmHg [28]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 8-item Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-8), which assigns scores between 0 and 8. Scores ≥ 4 were considered indicative of depressive symptoms [29,30]. Chronic conditions, including diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease, were identified through self-report, considering prior medical diagnosis and/or the use of specific medications for these morbidities [24].

2.5. Outcomes: CIND and Dementias

The assessment of cognitive function was divided into different questions covering five cognitive subdomains, each with varying scores. Temporal orientation was assessed by the correct recognition of the day, month, year, and day of the week, with scores ranging from 0 to 4 points. Semantic verbal fluency was measured by the number of animals mentioned by the participant within one minute, with scores ranging from 0 to 20 points. Episodic memory was assessed through the “10-word list test” for immediate and delayed recall, with scores ranging from 0 to 20 points. Prospective memory was analysed based on the participant’s ability to remember to write his/her name at the end of the test, as previously instructed by the interviewer, with scores ranging from 0 to 4 points. Semantic memory was assessed through questions related to general and political knowledge, with scores ranging from 0 to 4 points [31].

Global cognitive function was assessed in two stages. First, for each cognitive subdomain, the scores were standardized by calculating the Z-score using the formula: Z-score = (individual score − subdomain mean) divided by the subdomain standard deviation. Then, the arithmetic mean of these standardized Z-scores was obtained across all assessed subdomains. From this final mean, the overall cognitive Z-score was calculated, again applying the standardization formula described above [31,32,33]. For individuals unable to complete the questionnaire of cognitive domains, a close friend or family member completed the 16-item Brazilian version of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE). A Likert scale from 1 to 5 was used to evaluate each question, considering the changes observed in the participant over the past two years [34].

CIND was defined as a global cognitive Z score of ≤−1.5 standard deviations. The diagnosis of dementia was established based on two criteria: (1) a global cognitive Z score of <−1.5 standard deviations accompanied by impairment in one or more instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), including financial management, use of transportation, telephone/cell phone, and medication administration; or (2) IQCODE score of ≥3.4 [31].

2.6. Fruits and Vegetables Consumption

The adequate frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption was defined as daily consumption over the seven days of the week [35,36]. Fruit consumption was assessed through a self-reported questionnaire on fruits and natural juices, with the questions: “How many days of the week do you usually consume fruit?” and “How many days of the week do you usually consume natural fruit juice?”. Vegetable consumption was measured by the question: “How many days of the week do you usually consume vegetables (such as cabbage, carrots, chayote, eggplant, zucchini, lettuce, tomatoes)?”. For both, adequate consumption corresponded to 7 points. The sum of the answers to these questions, totalling 14 points, was considered indicative of adequate consumption of fruits and vegetables combined (FV).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Bivariate analysis was conducted to evaluate the prevalence and association of fruit and vegetable consumption and FV with sociodemographic variables (sex, age group, skin colour, income, education, and living with a partner), lifestyles (smoking, excessive alcohol consumption and sedentary behaviour), and morbidities (obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, depression, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases), as well as the two primary outcomes (CIND and dementia). These variables were selected because they represent well-established modifiable risk factors for dementia reported in the literature [10]. The prevalence ratio (PR) was calculated using Poisson regression, with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). To determine the PR of morbidity variables, the ‘no’ category served as the reference. Conversely, for the other sociodemographic variables and lifestyles, the category representing the best scenario was used as the reference.

For the multivariate analysis, two models were conducted to examine the association between adequate fruit, vegetable, and FV consumption and the outcomes of CIND and dementia. Associations were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05. Variables with a p-value less than 0.20 in the bivariate analysis were included [37] in the multivariate analysis at the following levels: Model 1, adjusted for sociodemographic variables, and Model 2, adjusted for Model 1 plus lifestyle and morbidity factors. Before conducting the analyses, the database was calibrated using the svyset command according to the sampling structure and recommendations provided by the ELSI-Brazil study documentation, incorporating information on primary sampling units (PSUs), strata, and survey weights. Considering the complex sampling design, all analyses were then performed with the svy prefix in Stata/MP 12.1 to ensure population-representative estimates.

3. Results

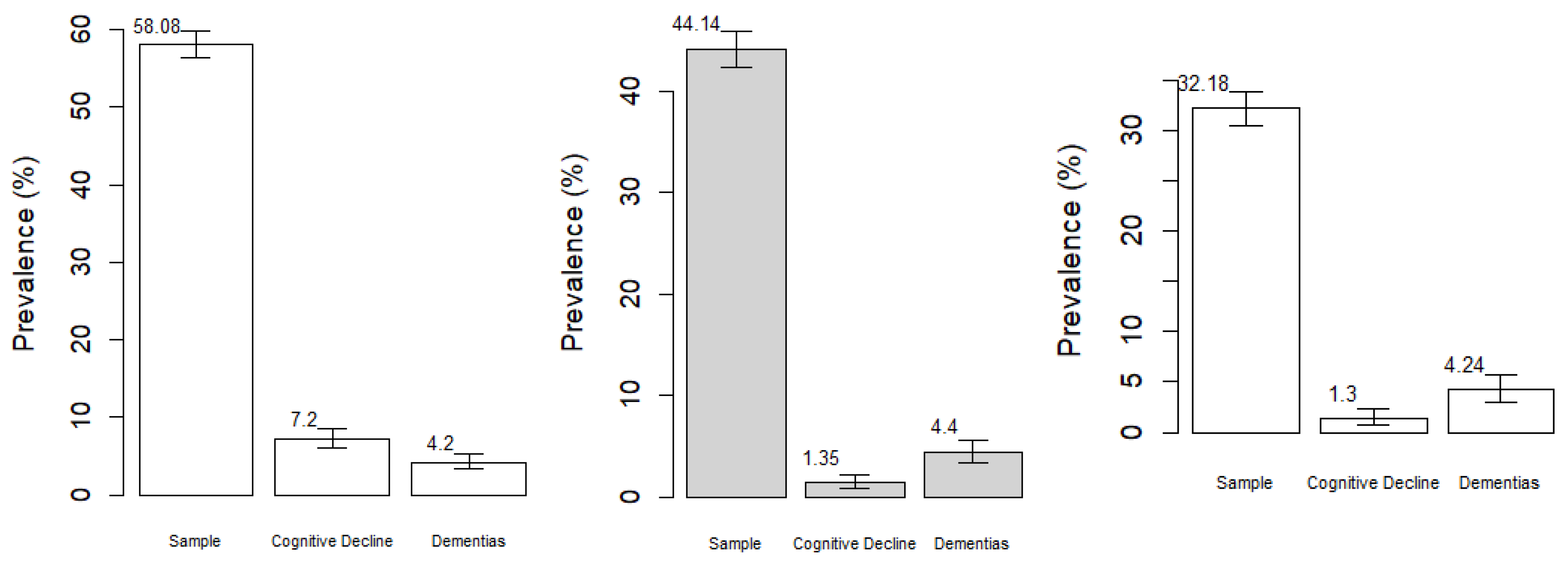

After applying the eligibility criteria, the sample included 2865 participants. The prevalence of adequate fruit consumption was 58.08% (95% CI: 56.3–59.9), with 7.2% (95% CI: 6.01–8.6) classified as CIND and 4.2% (95% CI: 3.34–5.35) as having dementia. Adequate vegetable consumption showed a prevalence of 44.14% (95% CI: 42.31–45.9), with 1.35% (95% CI: 0.8–2.1) presenting CIND and 4.2% (95% CI: 3.34–5.35) dementia. For combined adequate fruit and vegetable consumption, the prevalence was 32.18% (95% CI: 30.5–33.9), with 1.3% (95% CI: 0.67–2.3) exhibiting CIND and 4.24% (95% CI: 3.03–5.75) dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and FV in the sample and according to the occurrence of dementias and cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) in adults aged 50 years or older in Brazil (n = 2865).

In the bivariate analysis, adequate fruit consumption was associated with sex, skin colour, and education (p < 0.05). Age group, smoking, obesity, and diabetes mellitus were added to the multivariate model. Adequate vegetable consumption was associate with skin colour, education, and diabetes mellitus, with sex, depression, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease included in the multivariate analysis. Adequate FV consumption was associated with sex, education, and diabetes mellitus, and the multivariate model additionally considered age group, skin colour, per capita income, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and cerebrovascular disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence and association between adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and FV with sociodemographic variables, lifestyle, and morbidities among Brazilians aged 50 years and older (n = 2865).

CIND was associated with inadequate FV consumption (p < 0.001) and adequate fruit consumption (p = 0.014). When stratifying by frequency, CIND was associated with vegetable consumption on 0 to 4 days/week and 5 to 6 days/week (p < 0.001), and with fruit consumption on 5 to 6 days/week and 7 days/week (p = 0.004). No statistically significant associations were observed between dementias and adequate consumption of fruits and FV (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence and association between the frequencies of consuming fruits, vegetables, and FV with dementia and cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) in Brazilians aged 50 years or older (n = 2865).

In the multivariate analysis, adequate fruit consumption was a risk factor for CIND in Model 1 adjusted for sociodemographic variables and in Model 2 adjusted for lifestyle and morbidity variables (Table 3). Adequate fruit consumption was also associated with individuals aged 65 to 74 years and those with higher educational levels. Adequate vegetable consumption, in contrast, was a protective against CIND in both models and was associated with older age, white and black/other skin colour, secondary/higher education, hypertension, and depression. Adequate FV consumption was inversely associated with CIND in Model 1 (PR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.07–0.057; p = 0.003) and Model 2 (PR: 0.20; 95% CI: 0.07–1.58; p = 0.003) and was related to individuals aged 50–64 and 65–75 years, those in the second income quartile, with elementary and secondary/higher education, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the association between adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and FV with cognitive impairment no dementia (CIND) in Brazilians aged 50 years or older, according to two adjustment models (n = 2865).

After adjustments for sociodemographic, lifestyle, and morbidity variables, dementia was not associated with adequate fruit, vegetables or FV consumption (Table 4). In Model 1, adequate fruit consumption was associated with being female, aged 65 and 74 years, and having elementary or secondary/higher education. Adequate vegetable consumption was associated with individuals aged 65 to 74 and 75 or older, black/other skin colour, and elementary or secondary/higher education. In Model 2, it was additionally associated with hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Adequate FV consumption was associated with being female, aged 50 to 64 and 65 to 74 years, elementary or secondary/higher education, obesity and cerebrovascular disease (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of the association between adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and FV with dementias in Brazilians aged 50 years or older, based on two adjustment models (n = 2865).

4. Discussion

The current study investigates the relationship between fruit consumption and the incidence of age-related cognitive decline in a representative sample of the Brazilian population. Our findings highlight an association between lower vegetable consumption and a diagnosis of CIND. Conversely, daily fruit consumption was linked to CIND. Other variables, such as gender, education, and skin colour, were also related to adequate FV consumption. Finally, the occurrence of dementia was not associated with FV consumption. Our data provides important insights into the connection between dietary habits and the development of age-related cognitive decline.

The 32.18% prevalence of adequate FV consumption in this sample differs from the main nationally representative studies on the topic, which reported a 12.9% prevalence of appropriate consumption of these foods [38]. In low- and middle-income countries, the study using the first wave of the WHO Study of Global Ageing (SAGE) found prevalence rates of adequate fruit and vegetable consumption of 9.1% in China, 5.4% in Ghana, 3.3% in India, 9.7% in Mexico, 17.9% in Russia, and 7.8% in South Africa among individuals over 60 years old [39]. Currently, the WHO recommends a minimum consumption of 400 g/day of fruits and vegetables, mainly for preventing chronic diseases [40]. The differences between countries highlight the importance of sociocultural factors in shaping the population’s eating habits.

A small number of studies have investigated the association between fruit, vegetable, and FV consumption. The CIND observed in this study aligns with the findings of two studies conducted in older Chinese adults, which reported that vegetable intake [41], and especially the combined consumption of fruits and vegetables [42], decreased the risk of mild cognitive impairment. This highlights the importance of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of these foods, which inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines and protect synaptic connections from free radical damage in neuronal tissues [43].

The finding that fruit consumption is a risk factor and vegetable consumption is protective against CIND is intriguing and may result from several potential factors. One possibility is the increased time needed for food preparation. In this case, subclinical changes in functionality would favour the consumption of fruit, which requires no preparation, over adequate vegetable intake, which involves more complex steps such as washing, cooking, and others [44]. Furthermore, increased intake of fruits and fruit juices, which have a high glycaemic index, is linked to greater insulin and glucose spikes, triggering the development of insulin resistance and other mechanisms that ultimately cause increased inflammation, higher oxidative stress, and neuronal signalling dysfunction [45], and decreased the odds of pre-frailty [46].

However, when the exposure variables, in this case fruit and vegetable consumption, are obtained from questionnaires answered by close respondents rather than the participant themselves, the measurement of exposure becomes more susceptible to error. Even when the participant answers themselves, measurement error can still occur due to memory bias, especially among individuals with cognitive decline, who may not accurately recall the amount of food consumed throughout the week. In linear models, such classification errors can result in significant biases, including overestimation or underestimation of the associations between exposure and outcome [47].

No significant association was found between adequate fruit, vegetable, and FV consumption and the occurrence of dementia. Similar results were observed in a study conducted in the Netherlands with older adults, which also found no significant relationship between vegetable consumption and the risk of dementia [48], as well as in a study conducted in the United Kingdom with adults and older adults, which found no consistent association between varied fruit and vegetable consumption and a lower risk of dementia [49]. In contrast, data from the Framingham Heart Study demonstrated that cumulative consumption of flavonoid-rich fruits, starting in middle age, was associated with a 44% reduction in the risk of dementia from all causes [50].

The low prevalence of individuals diagnosed with dementia in this study sample may also, in part, explain the lack of an observed association. This observation highlights the instrumental differences used by the study to measure cognitive domains. Thus, creating harmonized protocols, such as the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP) initiative, could be an advantage for calibrating these measures and the validity of dementia estimates, even contributing to comparison with similar studies from other countries [51]. Despite the limited power, these association estimates can be valuable for future studies, strengthening scientific transparency and avoiding publication bias.

Adequate consumption of fruits, vegetables, and FV was associated with higher education, especially among those with the highest educational attainment. These findings were also reported in a cross-sectional study of fruit and vegetable intake among adults conducted across 21 European countries [52] and in a Brazilian study involving individuals aged 60 and above [53]. People with less education tend to be more influenced by factors like price, ease of access, and satiety, which can lower their likelihood of purchasing nutritionally rich foods such as fruits and vegetables [54].

While younger-old adults have higher overall vegetable intake, the oldest-old are more likely to achieve adequate vegetable consumption than adequate fruit consumption. This distinction is corroborated by another study conducted within the first wave of the same ELSI-Brazil study [22], which demonstrated higher vegetable consumption among older adults, as well as by a Chinese study that reported higher fruit consumption among younger adults [38]. Furthermore, in this study, individuals who self-identified as white consumed adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables compared to those of mixed race, Black, Asian, or Indigenous skin colour. These skin colour-related differences may be influenced by socioeconomic and demographic conditions that limit access to and promotion of these foods. In the Brazilian context, the mixed-race population is particularly vulnerable to these limitations [55].

It was observed that individuals with hypertension, DM, and obesity had adequate consumption of fruits and vegetables, which may serve as a protective factor against CIND and the development of dementia. Although, this finding may reflect a reverse causality bias, where the outcome precedes and results from the exposure, inherent to the cross-sectional design of the study and to outcomes with long preclinical or subclinical periods, since the temporal order between exposure and outcome cannot be established [56]. And this condition may be reflected in individuals with chronic diseases who frequently receive nutritional guidance from health professionals to adopt healthier eating habits, including increasing the intake of these foods as part of the management of their condition.

This study has some limitations, such as: (I) risk of reverse causality; (II) potential for recall bias in dietary assessment; (III) the variable related to fruit and vegetable consumption did not include detailed information on the type, quality, or preparation methods of these foods, which could have limited a more precise analysis of their effects on cognitive outcomes; (IV) the low prevalence of dementia may have reduced the statistical power for detecting a possible association; (V) possible selection bias due to exclusion of participants with missing cognitive assessments.

For future research, it is recommended that longitudinal studies be conducted to monitor individuals over time, thereby addressing the limitations inherent in cross-sectional studies. Additionally, it is recommended that nutritional assessment tools be improved, given the complexity of dietary habits and their potential role as protective factors against CIND. Large-scale studies with nationally representative samples could provide stronger evidence. Successfully increasing fruit and vegetable intake among older adults depends on coordinated national policies that promote consumption and make access affordable.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of sufficient fruit consumption was just over 50%. In contrast, the levels of sufficient vegetable and FV consumption were quite low, indicating the low consumption of these foods among the Brazilian population. The association between sufficient vegetable and FV consumption served as a protective factor against CIND. No connection was found between sufficient fruit and vegetable consumption and dementia. The population’s dietary habits and their influence on cognitive health can help identify risk and protective factors related to CIND and dementia, supporting the development of preventive strategies and encouraging healthy and cognitively active ageing.

Author Contributions

E.A.S. conceived the study and supervised all stages of the project. A.M.d.S.R., E.A.S. and C.d.O. contributed to the formulation of the study design and the development of the protocol. A.M.d.S.R. was responsible for data analysis, curation, and visualization. A.M.d.S.R., G.S.A., C.d.O. and E.A.S. wrote the original manuscript, with contributions and critical input from all authors. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

ELSI-Brazil was supported by the Brazilian Ministry of Health: DECIT/SCTIE (Grants: 404965/2012-1 and TED 28/2017); COPID/DECIV/SAPS (Grants: 20836, 22566, 23700, 25560, 25552, and 27510).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (FIOCRUZ) (protocol number 34649814.3.0000.5091 and 9 June 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil). Researchers can access the dataset upon registration and approval through the official ELSI-Brazil website https://elsi.cpqrr.fiocruz.br (accessed on 25 May 2025). The study is conducted in accordance with national and international ethical standards, and all data are anonymized to ensure participant confidentiality. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Juan, S.M.A.; Adlard, P.A. Ageing and Cognition. In Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Ageing: Part II Clinical Science; Harris, J.R., Korolchuk, V.I., Eds.; Subcellular Biochemistry; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 91, pp. 107–122. ISBN 978-981-13-3680-5. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-13-3681-2_5 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Kritsilis, M.; Rizou, S.V.; Koutsoudaki, P.; Evangelou, K.; Gorgoulis, V.; Papadopoulos, D. Ageing, Cellular Senescence and Neurodegenerative Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Departament of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Divisions. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Treichler, E.B.H.; Jeste, D.V. Cognitive decline in older adults: Applying multiple perspectives to develop novel prevention strategies. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2016, 22, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil Ministério da Saúde. Relatório Nacional sobre a Demência: Epidemiologia, (Re)conhecimento e Projeções Futuras; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2024/setembro/relatorio-nacional-sobre-a-demencia-estima-que-cerca-de-8-5-da-populacao-idosa-convive-com-a-doenca (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446, Erratum in Lancet 2023, 402, 1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02043-3.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adoukonou, T.; Yoro-Zohoun, I.; Gnonlonfoun, D.D.; Amoussou, P.; Takpara, C.; Agbetou, M.; Guerchet, M.; Preux, P.-M.; Houinato, D.; Ouendo, E.-M. Prevalence of Dementia among Well-Educated Old-Age Pensioners in Parakou (Benin) in 2014. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2020, 49, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Ford, C.N.; Leurgans, S.E.; Beck, T.; Desai, P.; Dhana, K.; Evans, D.A.; Halloway, S.; Holland, T.M.; Krueger, K.R.; et al. Dietary Sugar Intake Associated with a Higher Risk of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 95, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Hao, M.; Xia, Y.; Huang, H.; Høj Jørgensen, T.S.; Agogo, G.O.; Wang, L.; et al. Associations of Midlife Dietary Patterns with Incident Dementia and Brain Structure: Findings from the UK Biobank Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Rest, O.; Berendsen, A.; Haveman-Nies, A.; de Groot, L. Dietary Patterns, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek Rivan, N.F.; Shahar, S.; Fakhruddin, N.N.I.N.M.; You, Y.X.; Che Din, N.; Rajikan, R. The effect of dietary patterns on mild cognitive impairment and dementia incidence among community-dwelling older adults. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 901750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cui, K.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, Z.; Song, R.; Qi, X.; Xu, W. Effect of Polyphenols on Cognitive Function: Evidence from Population-based Studies and Clinical Trials. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 1190–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Micek, A.; Mena, P.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F.; Castellano, S.; Grosso, G. Dietary (Poly)phenols and Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, 2300472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska, O. The Neuroprotective Potential of Polyphenols in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Food Sci. Nutr. Cases 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberger-Gateau, P.; Raffaitin, C.; Letenneur, L.; Berr, C.; Tzourio, C.; Dartigues, J.F.; Alperovitch, A. Dietary patterns and risk of dementia: The Three-City cohort study. Neurology 2007, 69, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, E.R.; Cadar, D.; Steptoe, A.; Ajnakina, O. Interplay between polygenic propensity for ageing-related traits and the consumption of fruits and vegetables on future dementia diagnosis. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.F.; Andel, R.; Small, B.J.; Borenstein, A.R.; Mortimer, J.A.; Wolk, A.; Johansson, B.; Fratiglioni, L.; Pedersen, N.L.; Gatz, M. Midlife Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Risk of Dementia in Later Life in Swedish Twins. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, R.; Yamagishi, K.; Iso, H.; Ishihara, J.; Yasuda, N.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Sawada, N. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Risk of Disabling Dementia: Japan Public Health Center Disabling Dementia Study. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 1842–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngabirano, L.; Samieri, C.; Feart, C.; Gabelle, A.; Artero, S.; Duflos, C.; Berr, C.; Mura, T. Intake of Meat, Fish, Fruits, and Vegetables and Long-Term Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 68, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, N.G.; Bertola, L.; Ferri, C.P.; Suemoto, C.K. Rural-urban disparities in fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive performance in Brazil. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2023, 45, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Costa, M.F.; De Andrade, F.B.; Souza, P.R.B.D.; Neri, A.L.; Duarte, Y.A.D.O.; Castro-Costa, E.; De Oliveira, C. The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSI-Brazil): Objectives and Design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Costa, M.F.; De Melo Mambrini, J.V.; Bof De Andrade, F.; De Souza, P.R.B.; De Vasconcellos, M.T.L.; Neri, A.L.; Castro-Costa, E.; Macinko, J.; De Oliveira, C. Cohort Profile: The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSI-Brazil). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 52, e57–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking Levels Defined. 2023. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-drinking-patterns (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Pardini, R.; Matsudo, S.; Matsudo, V.; Araújo, T.; Andrade, E.; Braggion, G.; Andrade, G.; Oliveira, L.; Figueira-Junior, A.; Raso, V. Validation of the International Physical Activity Questionaire (IPAQ version 6): Pilot study in Brazilian young adults. Rev. Bras. Ciência Mov. 2001, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, E.A.; Pagotto, V.; Barbosa, L.S.; Oliveira, C.D.; Pena, G.D.G.; Velasquez-Melendez, G. Acurácia de pontos de corte de IMC e circunferência da cintura para a predição de obesidade em idosos. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, N.R.C.; Burnens, M.P.; Whelton, P.K.; Angell, S.Y.; Jaffe, M.G.; Cohn, J.; Espinosa Brito, A.; Irazola, V.; Brettler, J.W.; Roccella, E.J.; et al. Diretrizes de 2021 da Organização Mundial da Saúde sobre o tratamento medicamentoso da hipertensão arterial: Repercussões para as políticas na Região das Américas. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2022, 46, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.; Carey, D.; O’Halloran, A.M.; Kenny, R.A.; Kennelly, S.P. Validation of the 8-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in a cohort of community-dwelling older people: Data from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, W.V.; Zimmer, E.R.; Bieger, A.; Coelho, B.; Pascoal, T.A.; Chaves, M.L.F.; Amariglio, R.; Castilhos, R.M. Subjective cognitive decline in Brazil: Prevalence and association with dementia modifiable risk factors in a population-based study. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2022, 14, e12368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, L.; Suemoto, C.K.; Aliberti, M.J.R.; Gomes Gonçalves, N.; Pinho, P.J.d.M.R.; Castro-Costa, E.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Ferri, C.P. Prevalence of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment No Dementia in a Large and Diverse Nationally Representative Sample: The ELSI-Brazil Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.B.D.; Anderle, P.; Goulart, B.N.G.D. Association between self-perceived hearing status and cognitive impairment in the older Brazilian population: A population-based study. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2023, 28, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, N.G.; Avila, J.C.; Bertola, L.; Obregón, A.M.; Ferri, C.P.; Wong, R.; Suemoto, C.K. Education and cognitive function among older adults in Brazil and Mexico. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2023, 15, e12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Jacomb, P.A. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychol. Med. 1989, 19, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, Ministry of Health. Vigitel Brasil 2016: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico: Estimativas sobre Frequência e Distribuição Sociodemográfica de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas nas Capitais dos 26 Estados Brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2016; Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2017; 160p, ISBN 978-85-334-2479-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (Brazil). Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population, 2nd ed.; Ministry of Health: Brasília, Brazil, 2014; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, K.J.; Greenland, S.; Lash, T.L. Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bolbinski, P.; Nascimento-Souza, M.A.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Peixoto, S.V. Consumption of fruits and vegetables among older adults: Findings from the ELSI-Brazil study. Cad. Saúde Pública 2023, 39, e00158122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, C.M.; Lamb, K.E.; McNaughton, S.A. Cross-sectional associations between fruit and vegetable intake and successful ageing across six countries: Findings from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; p. 160. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y.; Deng, J.; Jiang, K.; Shi, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wu, R.; Zhou, A.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y. Correlation between Vegetable and Fruit Intake and Cognitive Function in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study in Chongqing, China. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, A.; Wang, M.; Xu, L. Increased Intake of Vegetables and Fruits Improves Cognitive Function among Chinese Oldest Old: 10-Year Follow-Up Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrattan, A.M.; McGuinness, B.; McKinley, M.C.; Kee, F.; Passmore, P.; Woodside, J.V.; McEvoy, C.T. Diet and Inflammation in Cognitive Ageing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2019, 8, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, L.M.R.; Almeida, L.F.F.; Machado, C.J.; Pessoa, M.C.; Duarte, M.S.L.; Franceschini, S.C.C.; Ribeiro, A.Q. Food Consumption and Characteristics Associated in a Brazilian Older Adult Population: A Cluster Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 641263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli Ceccarelli, D.; Solerte, S.B. Unravelling Shared Pathways Linking Metabolic Syndrome, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, and Sarcopenia. Metabolites 2025, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ygnatios, N.T.M.; De Oliveira, C.; Mambrini, J.V.D.M.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Torres, J.L. Daily fruit or vegetable consumption and frailty among older adults: Findings from the ELSI-Brazil and ELSA cohorts. Geriatr. Nur. 2025, 62, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stayner, L.; Pearce, N.; Nøhr, E.; Freeman, L.B.; Deffner, V.; Ferrari, P.; Freedman, L.S.; Kogevinas, M.; Kromhout, H.; Lewis, S.; et al. Information Bias: Misclassification and Mismeasurement of Exposure and Outcome; IARC Scientific Publications, No. 171; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2024; Chapter 4. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK612868 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- de Crom, T.O.E.; Blekkenhorst, L.; Vernooij, M.W.; Ikram, M.K.; Voortman, T.; Ikram, M.A. Dietary nitrate intake in relation to the risk of dementia and imaging markers of vascular brain health: A population-based study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Cheng, B.; Li, X.; Xia, J.; Gou, Y.; Kang, M.; Hui, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Liu, C.; et al. Association of dietary diversity, genetic susceptibility, and the risk of incident dementia: A prospective cohort study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 12, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Jacques, P.F.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Young, B.; Gurnani, A.S.; Au, R.; Hwang, P.H. Flavonoid-Rich Fruit Intake in Midlife and Late-Life and Associations with Risk of Dementia: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.L.; Li, C.; Briceño, E.M.; Arce Rentería, M.; Jones, R.N.; Langa, K.M.; Manly, J.J.; Nichols, E.; Weir, D.; Wong, R.; et al. Harmonisation of later-life cognitive function across national contexts: Results from the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocols. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e573–e583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stea, T.H.; Nordheim, O.; Bere, E.; Stornes, P.; Eikemo, T.A. Fruit and vegetable consumption in Europe according to gender, educational attainment and regional affiliation—A cross-sectional study in 21 European countries. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E.A.; Martins, B.B.; Abreu, L.R.S.D.; Cardoso, C.K.D.S. Baixo consumo de frutas, verduras e legumes: Fatores associados em idosos em capital no Centro-Oeste do Brasil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 3689–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgambato, M.R.; Lignani, J.D.B.; Pires, C.A.; Ribeiro, E.C.D.S.A.; Domingos, T.B.; Ferreira, A.A.; Sichieri, R.; Oliveira, L.G.D.; Salles-Costa, R. Inequalities in food acquisition according to the social profiles of the head of households in Brazil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 4303–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Jesus, A.C.D.S.D.; Jesus, J.G.L.D.; Madruga, M.F.; Souza, T.N.; Louzada, M.L.D.C. Diferenças no consumo alimentar da população brasileira por raça/cor da pele em 2017–2018. Rev. Saúde Pública 2023, 57, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, L.M.; Brenowitz, W.D.; Meyer, O.L.; Hoermann, S.; Renne, J. Methods to Address Self-Selection and Reverse Causation in Studies of Neighborhood Environments and Brain Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.