Cross-Sectional Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Physical Activity, Satisfaction with Physical Education, and Bicycle Use Among Primary School Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Variables and Instruments

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Data, Physical Activity Outside School, and Bicycle Ownership and Use

2.2.2. MD Adherence

2.2.3. Satisfaction with PE Classes

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Variables

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Physical Activity Outside School, Bicycle Ownership and Use, MD Adherence, and Satisfaction with PE by Sex

3.3. Comparative Analysis of MD Adherence by Physical Activity Outside School, Bicycle Ownership and Use, and Satisfaction with PE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission: European Education and Culture Executive Agency. Physical Education and Sport at School in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/49648 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Martín-Flórez, J.; Romero-Martín, M.R.; Chivite-Izco, M. La educación física en el sistema educativo español. REEFD 2015, 411, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanal, J.; Cheval, B.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Paumier, D. Developmental relations between motivation types and physical activity in elementary school children. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 43, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; Goldfield, G.; Connor-Gorber, S. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard, E.L.; Obling, K.; Maindal, H.T.; Rasmussen, C.; Overgaard, K. Unprompted vigorous physical activity is associated with higher levels of subsequent sedentary behaviour in participants with low cardio-respiratory fitness: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2019, 19, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloigne, M.; Loyen, A.; Van Hecke, L.; Lakerveld, J.; Hendriksen, I.; De Bourdheaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Donnelly, A.; Ekelund, U.; Brug, J.; et al. Variation in population levels of sedentary time in European children and adolescents according to cross-European studies: A systematic literature review within DEDIPAC. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, H.L.; Buro, A.W.; Ikan, J.B.; Wang, W.; Stern, M. School-level factors associated with obesity: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1016–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.P.; Andersen, L.B.; Byrne, N.M. Physical activity and obesity in children. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 866–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åman, J.; Skinner, T.C.; de Beaufort, C.E.; Swift, P.G.F.; Aanstoot, H.J.; Cameron, F. Associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior, and glycemic control in a large cohort of adolescents with type 1 diabetes: The Hvidoere Study Group on Childhood Diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2009, 10, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinckard, K.; Baskin, K.K.; Stanford, K.I. Effects of Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo-Carrascosa, D.P.; García-Hermoso, A.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Sánchez-López, M.; Martínez-Vizcaino, V. Effectiveness of school-based physical activity programmes on cardiorespiratory fitness in children: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. Estudio Aladino 2023: Estudio Sobre la Alimentación, Actividad Física, Desarrollo Infantil y Obesidad en España 2023; Ministerio de Derechos Sociales, Consumo y Agenda 2030: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lirola, M.-J.; Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Mercader, I.; Fernandez Campoy, J.M.; del Pilar Díaz-López, M. Physical Education and the Adoption of Habits Related to the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2021, 13, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinel-Martínez, C.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Castro-Sánchez, M.; Espejo-Garcés, T.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Pérez-Cortés, A. Diferencias de género en relación con el Índice de Masa Corporal, calidad de la dieta y actividades sedentarias en niños de 10 a 12 años. Retos 2017, 31, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Braithwaite, R.E.; Biddle, S.J.; van Sluijs, E.M.; Atkin, A.J. Associations between sedentary behaviour and physical activity in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: At a Glance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Revelles, A.B. El tiempo en la clase de educación física: La competencia docente tiempo. Deporte Act. Física Para. Todos 2008, 4, 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sprengeler, O.; Buck, C.; Hebestreit, A.; Wirsik, N.; Ahrens, W. Sports Contribute to Total Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity in School Children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1653–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; Cuesta-Valera, P.; Zamorano-García, D.; Simón-Piqueras, J.A. Health-based physical education in an elementary school: Effects on physical self-concept, motivation, fitness and physical activity. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Physical Education-as-Health Promotion: Recent Developments and Future Issues. Educ. Health 2018, 36, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Tambalis, K.D.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Psarra, G.; Sidossis, L.S. Concomitant Associations between Lifestyle Characteristics and Physical Activity Status in Children and Adolescents. J. Res. Health Sci. 2019, 19, e00439. [Google Scholar]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Cherni, Y.; Panaet, E.A.; Alexe, C.I.; Ben Saad, H.; Vulpe, A.M.; Alexe, D.I.; Chelly, M.-S. Mini-Trampoline Training Enhances Executive Functions and Motor Skills in Preschoolers. Children 2025, 12, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Peris, A.; Lizandra, J.; Cebriá-Carrión, S.; Evangelio-Caballero, C. Sensitivity about Sedentarism in Physical Education from a Hybridization of two pedagogical models. ENSAYOS 2022, 37, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, C.; Avolio, E.; Galluccio, A.; Caparello, G.; Manes, E.; Ferraro, S.; Caruso, A.; De Rose, D.; Barone, I.; Adornetto, C.; et al. Nutrition Education Program and Physical Activity Improve the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet: Impact on Inflammatory Biomarker Levels in Healthy Adolescents from the DIMENU Longitudinal Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 685247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G.; Peralta, L.R. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Haas, N.A.; Dalla-Pozza, R.; Jakob, A.; Oberhoffer, F.S.; Mandilaras, G. Energy Drinks and Adverse Health Events in Children and Adolescents: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Martín, G.; Tárraga-López, P.J.; López-Gil, J.F. Cross-Sectional Association between Perceived Physical Literacy and Mediterranean Dietary Patterns in Adolescents: The EHDLA Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, G.; Bach, A.; Serra-Majem, L. Obesity and the Mediterranean diet: A systematic review of observational and intervention studies. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabthymer, R.H.; Karii, L.; Livesay, K.; Lee, M.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Millar, R.; McFadyen, S.; Barry, S.; Castañer Niño, O.; Fitó Colomer, M.; et al. Effect of Mediterranean diet on mental health outcomes: A systematic review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2025, 39, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Falo, E.M.; Sánchez-Moreno, C.; Esteban, A.; Alburquerque, J.J.; Garaulet, M. Calidad de la dieta «antes y durante» un tratamiento de pérdida de peso basado en dieta mediterránea, terapia conductual y educación nutricional. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Floody, P.; Cofré-Lizama, A.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Jerez-Mayorga, D.; Martínez-Salazar, C.; Caamaño-Navarrete, F. Perception of obese schoolchildren regarding their participation in the Physical Education class and their level of self-esteem: Comparison according to corporal status. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiba, G.; Gacek, M.; Wojtowicz, A.; Majer, M. Level of knowledge regarding health as well as health education and pro-health behaviours among students of physical education and other teaching specialisations. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 11, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciana, J.; Mayorga-Vega, D.; Martínez-Baena, A.; Hagger, M.S.; Liukkonen, J.; Yli-Piipari, S. Effect of self-determined motivation in physical education on objectively measured habitual physical activity: A trans-contextual model. Kinesiology 2019, 51, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; García-Calvo, T.; Contreras, O. Perfiles motivacionales en Educación Física: Una aproximación desde la teoría de las Metas de Logro 2x2. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisterer, S.; Jekauc, D. Students’ Emotional Experience in Physical Education—A Qualitative Study for New Theoretical Insights. Sports 2019, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adank, A.M.; Van Kann, D.H.H.; Borghouts, L.B.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Vos, S.B. That’s what I like! Fostering enjoyment in primary physical education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2024, 30, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The ‘‘what’’ and ‘‘why’’ of goal pursuits: Human need and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtiniemi, M.; Sääkslahti., A.; Watt, A.; Jaakkola, T. Associations among Basic Psychological Needs, Motivation and Enjoyment within Finnish Physical Education Students. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 18, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C.; Archer, J. Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 1988, 80, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Correlates of achievement goal orientations in physical education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2003, 39, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gråstén, A.; Watt, A.P. A motivational model of physical education and links to enjoyment, knowledge, performance, total physical activity and body mass index. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2017, 16, 318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Jaitner, D.; Rinas, R.; Becker, C.; Niermann, C.; Breithecker, J.; Mess, F. Supporting Subject Justification by Educational Psychology: A Systematic Review of Achievement Goal Motivation in School Physical Education. Front. Educ. 2019, 4, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.; Gråstén, A.; Quay, J.; Kokkonen, M. Contribution of motivational climates and social competence in physical education on overall physical activity: A self-determination theory approach with a creative physical education twist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercê, C.; Pereira, J.V.; Branco, M.; Catela, D.; Cordovbil, R. Training programmes to learn how to ride a bicycle independently for children and youths: A systematic review. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2023, 28, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, R. Is active commuting the answer to population health? Sports Med. 2008, 38, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrador-Colmenero, M.; Pérez-García, M.; Ruiz, J.R.; Chillón, P. Assessing Modes and Frequency of Commuting to School in Youngsters: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 26, 291–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Børrestad, L.B.; Østergaard, L.; Andersen, L.B.; Bere, E. Associations Between Active Commuting to School and Objectively Measured Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, S.; Mountfort, A.; Hopkins, D.; Flaherty, C.; Williams, J.; Brook, E.; Wilson, G.; Moore, A. Built Environment and Active Transport to School (BEATS) Study: Multidisciplinary and Multi-Sector Collaboration for Physical Activity Promotion. Retos 2015, 28, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Bauman, A.; de Geus, B.; Krenn, P.; Reger-Nash, B.; Kohlberger, T. Health benefits of cycling: A systematic review. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.B.; Wedderkopp, N.; Kristensen, P.; Möller, N.C.; Froberg, K.; Cooper, A.R. Cycling to School and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Longitudinal Study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, C.; Sandercock, G. Aerobic Fitness and Mode of Travel to School in English Schoolchildren. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sicilia, A.; Ferriz, R.; Trigueros, R.; González-Cutre, D. Adaptación y validación española del Physical Activity Class Satisfaction Questionnaire (PACSQ). Univ. Psychol. 2014, 13, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, B.; Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. How many children and adolescents in Spain comply with the recommendations on physical activity? J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2008, 48, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, R.H.O.; Werneck, A.O.; Martins, C.L.; Barboza, L.L.; Tassitano, R.M.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Jesus, G.M.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Tesler, R.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; et al. Global prevalence and gender inequalities in at least 60 min of self-reported moderate-to-vigorous physical activity 1 or more days per week: An analysis with 707,616 adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Álvarez, L.; Velázquez-Buendía, R.; Martínez-Gorroño, M.E.; Garoz-Puerta, I. Lifestyle and Physical Activity in Spanish Children and Teenagers: The Impact of Psychosocial and Biological Factors. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2009, 14, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, L.; Salali, G.D.; Andersen, L.B.; Hallal, P.C.; Northstone, K.; Sardinha, L.B.; Dyble, M.; Bann, D. Gender differences in the distribution of children’s physical activity: Evidence from nine countries. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, L.; Timperio, A.; Veitch, J.; Carver, A. Individual, social and neighbourhood correlates of cycling among children living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, R.; Ahern, A. Students’ and parents’ perceptions of barriers to cycling to school—An analysis by gender. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ruiz, V.; Jiménez-Mejías, E.; Amezcua-Prieto, C.; Luna del Castillo, J.D.; Jiménez-Moleón, J.J.; Lardelli-Claret, P. Asociación de la edad y el sexo con la intensidad de la exposición al uso de la bicicleta en España, 1993–2009. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2014, 37, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.; Goodman, A.; van Sluijs, E.; Millett, C.; Laverty, A.A. Cycle training and factors associated with cycling among adolescents in England. J. Transp. Health 2020, 16, 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Ramos, E.; Tomaino, L.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Gómez, S.F.; Wärnberg, J.; Osés, M.; González-Gross, M.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S.; et al. Trends in Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Spanish Children and Adolescents across Two Decades. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaccarino Idelson, P.; Scalfi, L.; Valerio, G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-López, M.; Ruiz-Juan, F.; García-Montes, M.E. Relación entre satisfacción en Educación Física y práctica deportiva extraescolar. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2011, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz González, V.; Gómez-López, M.; Granero-Gallegos, A. Relación entre la satisfacción con las clases de Educación Física, su importancia y utilidad y la intención de práctica del alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Rev. Complut. Educ. 2019, 30, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Patón, R.; Rodríguez-Negro, J.; Muíño-Piñeiro, M.; Mecías-Calvo, M. Gender and Educational Stage Differences in Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs and Enjoyment: Evidence from Physical Education Classes. Children 2024, 11, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón-Colorado, J.; Maneiro-Dios, R.; Garrote-Jurado, R.; Moral-García, J.E. Motivation in Physical Education class according to sex, age, level of physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Sport TK-EuroAm. J. Sport Sci. 2025, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, C.; Guzmán-Guzmán, I.P.; Latorre-Román, P.Á.; Párraga-Montilla, J.; Palomino-Devia, C.; Reyes-Oyola, F.A.; Paredes-Arévalo, L.; Leal-Oyarzún, M.; Obando-Calderón, I.; Cresp-Barria, M.; et al. Association between the Sociodemographic Characteristics of Parents with Health-Related and Lifestyle Markers of Children in Three Different Spanish-Speaking Countries: An Inter-Continental Study at OECD Country Level. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunda, M.; Gilic, B.; Sekulic, D.; Matic, R.; Drid, P.; Alexe, D.I.; Cucui, G.G.; Lupu, G.S. Out-of-School Sports Participation Is Positively Associated with Physical Literacy, but What about Physical Education? A Cross-Sectional Gender-Stratified Analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic among High-School Adolescents. Children 2022, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Boys | 45.8% (n = 159) |

| Girls | 53.6% (n = 186) | |

| Engagement in out-of-school physical activity | Yes | 71.2% (n = 247) |

| No | 28.8% (n = 100) | |

| Having and using the bicycle | Yes | 75.5% (n = 262) |

| No | 24.5% (n = 85) | |

| MD adherence | Low-quality diet | 15.3% (n = 53) |

| Needs improvement | 54.5% (n = 189) | |

| Optimal diet | 30.3% (n = 105) |

| Satisfaction with PE | M | SD | |

| PE Overall Satisfaction | 6.11 | 1.20 | |

| Teaching | 6.18 | 1.46 | |

| Relaxation | 5.95 | 1.48 | |

| Cognitive development | 6.31 | 1.48 | |

| Health and Fitness Improvement | 6.16 | 1.45 | |

| Interaction with Others | 6.08 | 1.47 | |

| Normative Success | 5.63 | 1.67 | |

| Fun and Enjoyment | 6.23 | 1.66 | |

| Mastery Experiences | 6.24 | 1.56 | |

| Recreational Experiences | 6.09 | 1.39 |

| Sex | Sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||

| Engagement in out-of-school physical activity | Yes | 78.3% (n = 126) | 65.1% (n = 121) | 0.009 * |

| No | 21.7% (n = 35) | 34.9% (n = 65) | ||

| Having and using the bicycle | Yes | 80.7% (n = 130) | 71.0% (n = 132) | 0.045 * |

| No | 19.3% (n = 31) | 29.0% (n = 54) | ||

| MD adherence | Low-quality diet | 16.1% (n = 26) | 14.5% (n = 27) | 0.914 |

| Needs improvement | 54.0% (n = 87) | 54.8% (n = 102) | ||

| Optimal diet | 29.8% (n = 48) | 30.6% (n = 57) | ||

| Sex | Levene’s Test | t-Test Sig. (Two-Tailed) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | ||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | Sig. | ||

| PE Overall Satisfaction | 6.04 | 0.09 | 6.18 | 0.08 | 0.140 | 0.907 | 0.314 |

| Teaching | 6.13 | 0.11 | 6.23 | 0.10 | 0.236 | 0.627 | 0.549 |

| Relaxation | 5.87 | 0.11 | 6.02 | 0.10 | 0.414 | 0.520 | 0.351 |

| Cognitive development | 6.23 | 0.11 | 6.38 | 0.10 | 0.186 | 0.667 | 0.353 |

| Health and Fitness improvements | 6.01 | 0.12 | 6.28 | 0.10 | 0.212 | 0.645 | 0.090 |

| Interaction with others | 6.04 | 0.11 | 6.10 | 0.10 | 0.018 | 0.893 | 0.708 |

| Normative Succes | 5.79 | 0.12 | 5.49 | 0.12 | 1.458 | 0.228 | 0.094 |

| Fun and enjoyment | 6.14 | 0.13 | 6.31 | 0.11 | 0.407 | 0.524 | 0.346 |

| Mastery Experiences | 6.05 | 0.13 | 6.40 | 0.10 | 2.196 | 0.139 | 0.037 * |

| Recreational Experiences | 6.01 | 0.11 | 6.15 | 0.09 | 0.074 | 0.786 | 0.333 |

| MD Adherence | Cramer’s V | Sig. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Quality Diet | Needs Improvement | Optimal Diet | ||||

| Engagement in out-of-school physical activity | Yes | 15.4% (n = 38) | 53.0% (n = 131) | 31.60% (n = 78) | 0.043 | 0.663 |

| No | 15.0% (n = 15) | 58.0% (n = 58) | 27.00% (n = 27) | |||

| Having and using the bicycle | Yes | 15.3% (n = 40) | 51.5% (n = 135) | 33.20% (n = 87) | 0.117 | 0.092 |

| No | 15.3% (n = 13) | 63.5% (n = 54) | 22.20% (n = 18) | |||

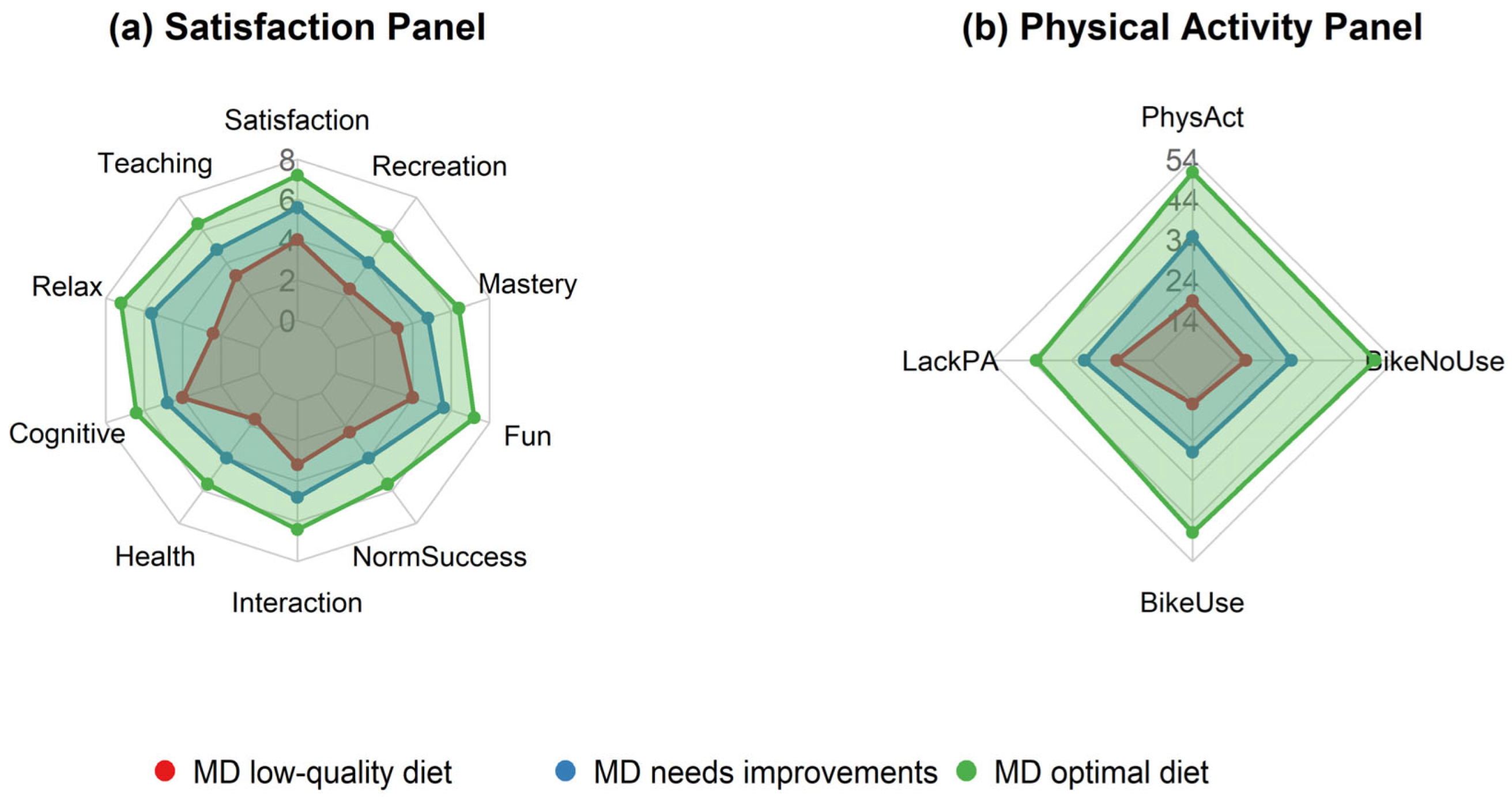

| MD Adherence | F | η2 | Sig. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Quality Diet | Needs Improvement | Optimal Diet | Total | ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| PE Overall Satisfaction | 5.68 | 1.07 | 6.09 | 1.21 | 6.38 | 1.18 | 6.11 | 1.20 | 6.267 | 0.035 | 0.002 *** |

| Teaching | 5.56 | 1.45 | 6.21 | 1.42 | 6.45 | 1.44 | 6.18 | 1.46 | 6.949 | 0.039 | 0.001 *** |

| Relaxation | 5.39 | 1.50 | 5.87 | 1.52 | 6.37 | 1.29 | 5.95 | 1.48 | 8.529 | 0.047 | 0.000 *** |

| Cognitive development | 5.64 | 1.61 | 6.33 | 1.44 | 6.62 | 1.40 | 6.31 | 1.48 | 7.832 | 0.044 | 0.000 *** |

| Health and Fitness Improvement | 5.67 | 1.35 | 6.15 | 1.48 | 6.41 | 1.41 | 6.16 | 1.45 | 4.734 | 0.027 | 0.009 *** |

| Interaction with Others | 5.86 | 1.39 | 5.98 | 1.50 | 6.36 | 1.43 | 6.08 | 1.47 | 2.887 | 0.017 | 0.057 |

| Normative Success | 5.79 | 1.55 | 5.59 | 1.67 | 5.62 | 1.74 | 5.63 | 1.67 | 0.279 | 0.002 | 0.757 |

| Fun and Enjoyment | 5.79 | 1.49 | 6.20 | 1.71 | 6.50 | 1.60 | 6.23 | 1.66 | 3.290 | 0.019 | 0.038 *** |

| Mastery Experiences | 5.89 | 1.58 | 6.15 | 1.61 | 6.58 | 1.41 | 6.24 | 1.56 | 4.134 | 0.023 | 0.017 *** |

| Recreational Experiences | 5.65 | 1.24 | 6.06 | 1.37 | 6.36 | 1.46 | 6.09 | 1.39 | 4.717 | 0.027 | 0.010 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moreno-Rosa, G.; San Román-Mata, S.; del Pino-Morales, C.Á.; Castro-Sánchez, M. Cross-Sectional Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Physical Activity, Satisfaction with Physical Education, and Bicycle Use Among Primary School Children. Nutrients 2026, 18, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030497

Moreno-Rosa G, San Román-Mata S, del Pino-Morales CÁ, Castro-Sánchez M. Cross-Sectional Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Physical Activity, Satisfaction with Physical Education, and Bicycle Use Among Primary School Children. Nutrients. 2026; 18(3):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030497

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Rosa, Guillermo, Silvia San Román-Mata, Carmen África del Pino-Morales, and Manuel Castro-Sánchez. 2026. "Cross-Sectional Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Physical Activity, Satisfaction with Physical Education, and Bicycle Use Among Primary School Children" Nutrients 18, no. 3: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030497

APA StyleMoreno-Rosa, G., San Román-Mata, S., del Pino-Morales, C. Á., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2026). Cross-Sectional Associations Between Mediterranean Diet Adherence, Physical Activity, Satisfaction with Physical Education, and Bicycle Use Among Primary School Children. Nutrients, 18(3), 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18030497