Abstract

Diet plays a central role in shaping the composition and metabolic activity of the oral microbiota, thereby influencing both oral and systemic health. Disturbances in this delicate host–microbe balance, triggered by dietary factors, smoking, poor oral hygiene, or antibiotic use, can lead to microbial dysbiosis and increase the risk of oral diseases such as periodontitis, as well as chronic systemic disorders including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and certain cancers. Among dietary contaminants, exposure to toxic heavy metals such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), nickel (Ni), and arsenic (As) represents an underrecognized modifier of the oral microbial ecosystem. Even at low concentrations, these elements can disrupt microbial diversity, promote inflammation, and impair metabolic homeostasis. Saliva has recently emerged as a promising, non-invasive biofluid for monitoring nutritional status and early metabolic alterations induced by diet and environmental exposures. Salivary biomarkers, including metabolites, trace elements, and microbial signatures, offer potential for assessing the combined effects of diet, microbiota, and toxicant exposure. This review synthesizes current evidence on how diet influences the oral microbiota and modulates susceptibility to heavy metal toxicity. It also examines the potential of salivary biomarkers as integrative indicators of nutritional status and metabolic health, highlights methodological challenges limiting their validation, and outlines future research directions for developing saliva-based tools in personalized nutrition and precision health.

1. Introduction

The human oral cavity harbors more than 700 microbial species, classified into 185 genera and 12 major bacterial phyla. Of this diverse community, approximately 54% of species have been fully characterized, 14% have been cultivated but remain unnamed, and about 32% are known only from DNA-based signatures (“phylotypes”) and have not yet been cultured or fully described [1,2]. As the entry point of the digestive tract, the oral microbiome influences nutrient absorption, metabolism, and immune function [3]. Dysbiosis of this microbial ecosystem is associated not only with oral diseases but also with systemic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and increased mortality risk [4,5].

Dietary patterns strongly influence the composition and function of the oral microbiota [6]. Studies comparing distinct dietary groups, including vegetarians, individuals following a Western diet, traditional farmers, and hunter-gatherers, demonstrate marked differences in oral microbial communities [7,8,9,10]. Using 16S rRNA sequencing, researchers have shown that the relative abundance of key taxa such as Neisseria and Haemophilus varies substantially according to dietary habits. Hunter-gatherer populations, who consume larger amounts of animal protein, display higher levels of several oral pathogens [11], whereas vegetarian diets induce broad shifts across multiple taxonomic levels, including changes in both oral pathogens and respiratory-associated microbes. Thus, diet also shapes microbial function; for instance, dietary transitions have been linked to adaptations such as vitamin B5 autotrophy and urease-mediated pH regulation [12].

Despite progress in oral health research, conventional diagnostic approaches remain retrospective and limited in their ability to detect early or subclinical disease, emphasizing the need for non-invasive, reproducible biomarkers capable of identifying active biological processes before irreversible tissue damage occurs [13]. Saliva has emerged as an especially promising diagnostic medium because it can be collected easily and non-invasively while reflecting both local oral conditions and systemic physiology [14]. However, the translational application of salivary biomarkers is currently constrained by substantial methodological heterogeneity, including differences between stimulated and unstimulated saliva collection, circadian variation, sample handling, and analytical platforms [15,16,17]. In parallel, advances in oral microbiome research have shifted the field from a pathogen-focused view to a broader ecological framework, recognizing microbial community imbalance, rather than specific pathogens alone, as a central driver of inflammation and tissue destruction [18].

Recent findings indicate that the oral ecosystem can display dynamic responses to physiological and environmental influences, although longitudinal studies suggest that, in the absence of disease or changes in oral hygiene, oral microbial communities remain relatively stable over time [19,20]. A study conducted by Sarkar et al. demonstrated that the salivary microbiome and salivary cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) exhibit circadian oscillations in healthy adults, with specific bacterial taxa fluctuating in synchrony or anti-phase with inflammatory markers. These observations underscore the potential of saliva as a non-invasive tool for monitoring temporal biological patterns in oral and systemic health [21].

Despite its remarkable diversity, the oral microbiome remains underexplored in relation to its role in maintaining health and its involvement in non-infectious diseases [22]. Alterations in oral microbial composition have been linked to obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and Metabolic Syndrome, suggesting that obesity-related changes may drive dysbiosis and contribute to metabolic dysfunction [23]. Salivary biomarkers have increasingly gained attention as potential indicators of metabolic status [24,25,26,27]. Their non-invasive nature and ability to reflect both local and systemic physiology make them promising tools for detecting early metabolic alterations and assessing individual susceptibility to metabolic dysfunction [28,29].

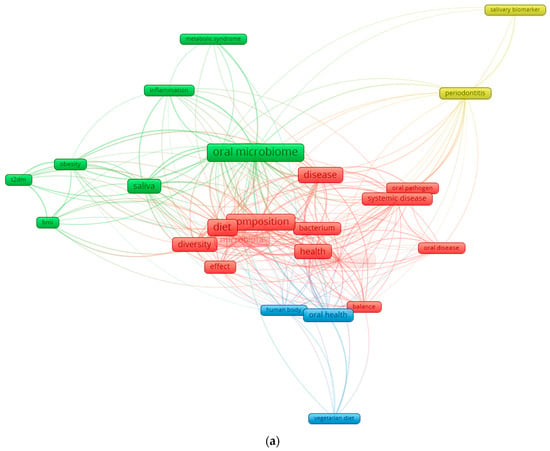

Although the current literature increasingly recognizes the role of diet in shaping the oral microbiota and influencing metabolic health, one important factor remains largely overlooked: the impact of dietary heavy metals on oral dysbiosis. Food-borne exposure to toxic metals, well known for disrupting the gut microbiome and metabolic pathways [30,31,32,33], is rarely integrated into studies of the oral microbiome, despite emerging evidence that these contaminants can alter microbial composition, promote oral pathogens, and modulate inflammatory and metabolic responses [34]. This conceptual gap is also evident in the bibliometric analysis where diet-, microbiota-, and metabolism-related terms are well represented, while heavy metals are almost entirely absent, highlighting a clear deficiency in the current research landscape.

Literature Search Strategy

This narrative review was informed by a structured, non-systematic literature search conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, covering studies published primarily between 2000 and 2025. Search terms included combinations of keywords such as “oral microbiome,” “diet,” “nutrition,” “saliva,” “salivary biomarkers,” “metabolic health,” “obesity,” and “heavy metals.” Bibliometric mapping and keyword network analyses were used to identify dominant research themes and knowledge gaps relevant to the aims of this review.

In this context, the primary objective of this review is to synthesize and critically appraise current evidence on how diet acts as a major upstream determinant of oral microbiota composition and function. Building on this foundation, we examine how diet-associated microbial alterations are reflected in salivary biomarkers and explore their potential relevance for systemic metabolic health. Secondary topics, including the role of dietary and environmental heavy metals, are discussed as emerging and exploratory factors that may further modulate oral microbial ecology and salivary biomarker profiles. By establishing this hierarchical framework, diet → oral microbiota → salivary biomarkers → systemic implications, this review aims to provide a coherent integrative perspective, highlight key knowledge gaps, and identify translational challenges relevant to personalized nutrition and precision health. In this review, the terms “eubiosis” and “dysbiosis” denote balanced versus disrupted microbial community states, respectively. The term “healthy diet” refers to fiber-rich, minimally processed dietary patterns, whereas “Western diet” denotes dietary patterns high in refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and ultra-processed foods. Figure 1 illustrates the current research landscape and underscores the need for this integrated perspective.

Figure 1.

Keyword co-occurrence network in the field of diet–oral microbiota research. (a) illustrates the global keyword co-occurrence network derived from recent literature on oral microbiota, diet, and health. Node size reflects the frequency of each keyword, while the color gradient represents the average publication year (from dark blue for earlier terms to yellow for more recent ones). Core concepts such as oral microbiome, diet, microbiota, saliva, health, and disease form the central structure of the network, indicating their dominant role in the field. Additional clusters highlight established themes (e.g., periodontitis, systemic disease) as well as emerging topics such as vegetarian diet and metabolic syndrome. (b) focuses exclusively on the connections of the keyword “diet.” This subnetwork isolates all terms directly linked to diet, revealing its relationships with microbiota composition, saliva, diversity, oral health, obesity, T2DM, and body mass index (BMI). The high density of links underscores the central role of dietary patterns in shaping oral microbial ecology and in modulating systemic metabolic pathways. By separating the global and diet-specific networks, the figure highlights both the broader research landscape and the specific influence of diet within it.

2. Oral Microbiota Composition

At birth, the oral microbiota is initially composed of a limited number of early colonizing genera, most commonly including Streptococcus and other facultative anaerobes; however, the relative abundance and taxonomic composition vary considerably depending on population, geographic region, delivery mode, feeding practices, and methodological approaches. As infancy progresses, additional genera such as Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Lactobacillus may increase in abundance, although this developmental trajectory is not uniform across studies [35,36,37]. Staphylococcus peaks around three months of age and then declines, concurrent with a rise in Gemella, Granulicatella, Haemophilus, and Rothia species. With tooth eruption, the oral ecosystem undergoes a major ecological transition, gradually incorporating higher abundances of Fusobacteriota, Synergistetes, Tenericutes, Saccharibacteria (TM7), and SR1 phyla as individuals progress toward adulthood [38].

The mature human oral cavity hosts a highly diverse microbial ecosystem composed of bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses, organized within complex biofilms that contribute to oral homeostasis [39,40]. Most bacterial members belong to the major phyla Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Chlamydia, Euryarchaeota, Fusobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Tenericutes, with additional, low-abundance groups such as Chloroflexi, Chlorobi, GN02, Synergistetes, SR1, TM7, and WPS-2—are also present. Among these, GN02, SR1, and TM7 are classified within the Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR), whose members influence the structural organization and functional dynamics of the oral microbial network, with implications for diseases such as periodontitis and halitosis [41]. Microbial species support oral and systemic health by preventing pathogenic colonization, contributing to nutrient metabolism, and regulating immune responses [42]. However, when this ecological balance is disrupted, the resulting dysbiosis can promote the development of both oral diseases and systemic disorders [43,44].

3. Diet Influence on Oral Microbiota

Oral health is influenced by various internal and external factors throughout life [45]. The adaptability of the oral cavity is shaped by host-related factors such as genetics, age, immune function, and lifestyle, as well as environmental factors including diet, pH, gingival crevicular fluid, and saliva [46,47], to modulate the diversity and composition of the oral microbiota [48]. It should be noted that antibiotic exposure, use of antiseptic mouth rinses, tobacco consumption, oral disease, and oral hygiene practices represent the primary drivers of oral microbiome variation, whereas diet acts predominantly as a modulator of microbial structure [20].

Recent evidence consolidates diet as one of the strongest modulators of oral microbial structure. Metin et al. [49] reviewed clinical evidence suggesting that healthier dietary patterns, characterized by higher intake of plant-based foods and fiber and lower consumption of refined sugars and processed foods, are associated with improved oral and periodontal health outcomes, including lower plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation. Although microbial taxa were not directly assessed, these findings indirectly support a link between diet quality and a more favorable oral environment. Similarly, Angarita-Díaz et al. [50] synthesizing studies comparing high- versus low-sugar intake through 16S rRNA sequencing, found that high sugar consumption significantly reduces microbial diversity and shifts community composition toward Streptococcus, Scardovia, Veillonella, Rothia, Actinomyces, and Lactobacillus. Specifically, frequent sugar exposure tended to favor acidogenic/aciduric bacteria at the expense of others, indicating a diet-induced dysbiosis rather than a stable, balanced microbiome [51]. Conversely, dietary fiber appears to exert beneficial effects. Kondo et al. [52] demonstrated that an eight-week high-fiber, low-fat dietary intervention in metabolically at-risk individuals significantly improved periodontal parameters, including reductions in probing depth, clinical attachment loss, and bleeding on probing, alongside improvements in systemic metabolic markers (body weight, HbA1c, hs-CRP). Although microbiota composition was not directly assessed, the findings suggest that fiber-rich diets can indirectly support a more balanced oral ecosystem by reducing inflammation and improving host metabolic status .

Antioxidants also contribute to maintaining oral ecological stability. Malcangi et al. [53] reports that dietary or supplemental intake of natural antioxidants supports endogenous antioxidant systems, protecting oral mucosal tissues from oxidative stress. Natural antioxidants modulate immune responses and the redox environment of the oral cavity, thereby helping limit the detrimental effects of pathogenic biofilms and chronic inflammation .

Additional functional foods and nutrients, including mangosteen (rich in xanthones and vitamin C), vitamin D, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and polyphenols, have been investigated as potential adjuncts for oral health. Available evidence, largely derived from small clinical trials and in vitro or short-term interventions, suggests possible benefits for oral inflammatory status and microbial balance; however, robust microbiome-based clinical data remain limited due to short trial durations and small sample sizes.

Fermented lingonberry juice used as a mouthwash for six months has demonstrated reductions in pathogenic species and increases in beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus [54]. Plant-based diets, including vegetarian and vegan patterns, may reduce periodontitis risk through higher fiber intake and lower pro-inflammatory saturated fats, though vegan diets may increase susceptibility to dental erosion and caries due to lower calcium, vitamin B12 intake, and reduced salivary pH [55,56,57]. Dietary influences on the oral microbiota also include the role of fermented foods and probiotic-containing products [58,59]. Nutrients introduced through meals act as substrates for oral bacteria, shaping which species can thrive in the oral cavity. Fermented foods enriched with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have well-established benefits for gut microbial balance and systemic health, and Lactobacillus species in particular can inhibit cariogenic pathogens such as Streptococcus mutans [60]. Experimental evidence further shows that fermented Japanese mugwort (Yomo gyutto) increases salivary secretion and alters the oral microbiota in mice, suggesting that certain fermented foods may exert dual effects on both oral and gut microbial communities [61].

Additionally, patterns of habitual food intake appear to influence the salivary microbiota. Hansen et al. [62] in a study of 160 healthy adults comparing vegans and omnivores, found subtle but significant differences in beta-diversity and in specific microbial taxa. Vegans exhibited higher abundances of commensals such as Neisseria subflava, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Rothia mucilaginosa, whereas omnivores displayed higher levels of Prevotella melaninogenica and Streptococcus species [62]. Dietary components including medium-chain fatty acids, marine mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, and dietary fiber were associated with both taxonomic and predicted functional variation, and several salivary bacteria correlated with systemic inflammatory markers, linking dietary patterns, oral microbiota, and host inflammation [63,64].

Dietary and Environmental Metal Exposure and Oral Microbiota Interactions

In the context of nutrition, dietary and environmental metal exposure can be conceptualized as an extension of diet-related inputs, reflecting not only food choices but also food quality, processing, and environmental contamination along the food chain. Beyond macronutrients and bioactive dietary compounds, environmental and dietary contaminants such as heavy metals have emerged as additional modulators of the oral microbiome [65,66]. From a dietary perspective, metal exposure reflects both food-related and environmental pathways. Dietary intake through contaminated food and drinking water represents a major chronic exposure route in the general population, whereas occupational or environmental exposures (e.g., air, soil) may contribute more substantially in specific settings (e.g., contamination of vegetables and irrigation water from polluted environments) [67]. The relative contribution of these pathways depends on dietary patterns, food sourcing, processing, and local environmental conditions. These metals can enter the body not only through smoking or environmental pollution but also through contaminated foods such as crops grown in polluted soils, cereals, fish and seafood, drinking water, and certain processed products [68,69,70]. Heavy metal exposure has been linked to microbiome-mediated conditions such as caries and gingival inflammation [71]. Salivary concentrations of metals such as antimony, arsenic, and mercury are associated with distinct microbial shifts; notably, elevated antimony correlates with higher levels of Lactobacillus spp., a genus strongly associated with acidogenic metabolism and caries development [72,73]. Exposure to additional metals, including chromium, nickel, and copper, has been associated with shifts in the relative abundance of genera such as Capnocytophaga, Neisseria, Aggregatella, Streptococcus, Campylobacter, Selenomonas, and Prevotella, reflecting structural alterations in the microbial community [74]. The salivary microbiome responds to environmental exposures such as metals, which bacteria need for metabolism but which can become toxic at elevated levels [75]. Because of this dual role, metal exposure can alter microbial composition and potentially affect oral health [76]. Importantly, most available evidence reflects associative findings, and relatively few studies distinguish between acute high-dose exposure and chronic low-dose exposure in otherwise healthy individuals [74,77]. Chronic dietary exposure through contaminated drinking water, soil-derived crops, seafood, or certain processed foods may induce subtle but persistent shifts in oral microbial communities without overt clinical disease [78]. Dietary context may further modulate these effects, as processed foods may increase exposure to contaminants and reduce microbial resilience, whereas whole-food diets may partially buffer metal-associated dysbiosis. Population-level observations from environmentally contaminated regions suggest that long-term metal exposure can disrupt microbial community structure and functional balance, yet studies integrating environmental contamination, dietary patterns, and oral microbiome profiling remain scarce [79]. Addressing these gaps will be essential for clarifying dose–response relationships and translational relevance.

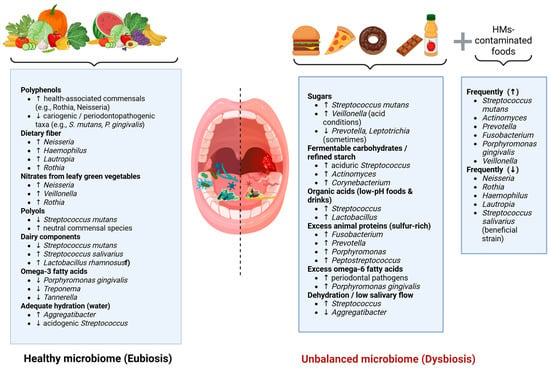

Unlike blood or urine, where reference guidelines exist, there are no established standards for interpreting salivary metal levels. Still, saliva is a promising biomarker for assessing metal exposure, especially when the oral cavity is the main target of toxicity. Although some studies have measured metals like lead, mercury, iron, magnesium, and zinc in saliva, research in this area remains limited [80]. A summary of how dietary components shape the oral microbiome is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual overview of dietary and environmental factors associated with modulation of the oral microbiome, based on the evidence discussed throughout the manuscript. Beneficial dietary factors (left) promote eubiosis by supporting health-associated oral bacteria, whereas sugars, fermentable carbohydrates, acidic foods, excessive animal proteins, omega-6 fatty acids, and low salivary flow (right) shift the microbiota toward dysbiosis. Heavy-metal-contaminated foods additionally contribute to pathogenic microbial profiles. Arrows indicate the direction of microbial changes (increase or decrease), while dashed lines represent the transition between eubiosis and dysbiosis.

4. Oral Microbiota and Nutritional Metabolism

The oral microbiota can influence the gastrointestinal tract through several mechanisms [81,82,83]. Oral bacteria may directly colonize the gut, disrupt microbial balance and affect digestive processes, including key functions such as butyrate production [48,83]. Periodontal pathogens can also enter the bloodstream, disseminate systemically, and contribute to diseases such as colorectal cancer; however, the frequency and clinical relevance of this process in humans remain unclear. In addition, microbial metabolites originating in the oral cavity may circulate through the blood, triggering low-grade inflammation and promoting chronic digestive disorders. Increasing evidence supports these pathways, suggesting that oral bacteria play a significant role in gut dysbiosis and systemic health [84,85].

Obesity is characterized by chronic low-grade inflammation that links it to metabolic diseases. This obesity-associated inflammation often referred to as “metainflammation” is especially evident in adipose tissue and involves inflammatory pathways that regulate metabolic homeostasis [86]. Supporting evidence includes findings that anti-inflammatory therapies improve metabolic outcomes, while weight loss reduces systemic inflammation [87,88]. The gut microbiome shows characteristic alterations in obesity, but growing data indicate that oral dysbiosis may also contribute to inflammatory processes in obesity, promoting metainflammation within adipose tissue and aggravating metabolic dysfunction [89].

Although the effects of diet and nutritional status on the gut microbiome and metabolome are well documented, their impact on the oral microbiome remains less thoroughly explored [90,91]. Nonetheless, existing evidence shows clear differences in oral microbial composition between obese and non-obese individuals, suggesting a potential role of oral bacteria in obesity [92,93]. Many dietary components, macronutrients, micronutrients, and pre/probiotics, as well as dietary patterns such as Mediterranean or low-carbohydrate diets, are known to influence gut microbiota and disease risk, but considerably less is known about how these factors shape the oral microbiome [94].

This knowledge gap is notable because diet is a major determinant of oral health and plays a crucial role in the development of dental caries and periodontal disease (PD). PD affects 20–50% of the global population and, in susceptible individuals, may contribute to or exacerbate systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. These conditions also reduce quality of life and impose substantial economic burdens on healthcare systems [95].

Burcham et al. [96] profiled the oral microbiome of adults (20–57 years) and children (8–9 years) using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Children exhibited higher evenness and Shannon diversity compared with adults. In adults, oral hygiene habits were the strongest determinants of microbiome variation, whereas in children, weight status and biological sex showed significant associations. The genus Treponema was more frequently detected in adults who had not visited a dentist recently and in obese children. Moreover, individuals from the same family shared more similar oral microbiomes than unrelated individuals, suggesting the combined influence of shared environment and behaviors, alongside potential host genetic contributions .

Yue et al. [97] reported that the oral microbiome produces and modifies various fatty acids, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which can influence the local oral environment. Animal studies show that oral inoculation with Porphyromonas gingivalis increases total free fatty acid (FFA) levels in tongue tissue and plasma and alters plasma FFA profiles, potentially via upregulation of de novo fatty-acid synthesis pathways. However, there is currently no definitive human evidence demonstrating that these microbial metabolites enter systemic circulation or directly regulate plasma FFA levels. Because elevated FFAs contribute to insulin resistance and are consistently observed in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), it is plausible that oral microbiome–derived metabolites may indirectly exacerbate insulin resistance by influencing FFA metabolism . The same authors further demonstrated that the oral microbiome can aggravate high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced insulin resistance. Oral inoculation with periodontal pathogens (P. intermedia, F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis) worsened insulin resistance and glucose intolerance associated with HFD, partly through antibody responses directed against P. gingivalis LPS. Additional experiments showed that P. gingivalis can increase insulin secretion and HOMA-IR even without elevating circulating FFAs, suggesting multiple mechanisms of metabolic disruption. Moreover, oral bacteria can increase serum branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), activating the mTOR–S6K1 pathway and impairing insulin signaling. Overall, the oral microbiome may promote HFD-induced insulin resistance through immune-mediated pathways and microbial metabolites, although validating these findings in humans will require more advanced and integrative models [97]. When the association between salivary microbiome composition and metabolic syndrome in adults was examined, Silva et al. identified specific microbial alterations correlating with clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome, suggesting that the salivary microbial profile may serve as a potential non-invasive biomarker for metabolic status. Collectively, these findings support the value of the oral microbiome as an accessible indicator of systemic metabolism and cardiometabolic risk [23].

5. Salivary Biomarkers of Nutritional Health

Nutritional status reflects an individual’s health condition as determined by the intake, absorption, and utilization of nutrients [98]. Its assessment is traditionally complex, requiring a combination of anthropometric measurements, clinical examination, dietary evaluation, blood analyses interpreted alongside medical history, and consideration of environmental factors that influence eating behaviors [99]. Deviations from expected values, such as abnormal biochemical markers or insufficient nutrient intake, may signal risks of malnutrition, iron-deficiency anemia, osteoporosis, or type 2 diabetes if timely nutritional interventions are not implemented [100]. Gathering accurate dietary information remains challenging. Common dietary assessment tools, such as food frequency questionnaires, 24-h recall, and food diaries, are subjective, prone to recall bias, and often affected by errors in portion estimation [101]. In this context, dietary biomarkers can address many of these limitations by providing objective indicators that complement self-reported data. Biomarkers offer a more reliable link between nutrient intake, nutritional status, and disease risk, and they are increasingly used in the detection, monitoring, and diagnosis of various health conditions [102].

Saliva contains a diverse repertoire of biomolecules, including electrolytes, hormones, cytokines, oxidative stress markers, enzymes, and microbial products [103]. Recent studies demonstrate that salivary biomarkers can reflect both nutritional imbalances and metabolic dysfunction [104]. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), for example, salivary profiles encompassing oxidative stress markers, inflammatory cytokines, microRNAs, calprotectin, PSMA7, α-amylase, and antioxidant enzymes display distinct patterns across disease activity, saliva type (stimulated vs. unstimulated), and IBD subtype. Elevated IL-1β, α-amylase, and malondialdehyde (MDA), along with reduced glutathione and FRAP, have been associated with active disease. Moreover, salivary cytokines and secretory IgA correlate with the abundance of IBD-associated oral taxa such as Prevotella, Haemophilus, Streptococcus, and Veillonella, underscoring the diagnostic value of integrating salivary biomarkers with microbiome profiling [105]. In sports and metabolic physiology, salivary biomarkers have shown similar promise. Campos et al. [106] reported that saliva can reliably capture fluctuations in immune, endocrine, oxidative stress, and muscle-damage biomarkers, although the authors emphasized the need for methodological standardization and individualized reference frameworks before broad clinical application .

Additional evidence supports the relevance of specific salivary analytes for nutritional monitoring. For example, Logan et al. identified several salivary biomarkers with strong potential for reflecting nutritional status and dietary intake, including glucose, vitamin D, calcium, total antioxidant capacity (TAC), nitrate/nitrite, and fluoride. Salivary glucose correlated with serum glucose in individuals with type 2 diabetes; salivary calcium was higher in post-menopausal women, particularly those with reduced bone mineral density; and salivary vitamin D showed promise in reflecting serum vitamin D levels in healthy volunteers. Nonetheless, the evidence remains limited and heterogeneous, and salivary markers cannot yet fully replace traditional nutritional or dietary assessments [102,107].

Saliva is also emerging as a useful medium for assessing oxidative stress. Biomarkers such as vitamin C, MDA, α-amylase, and antioxidant enzymes have been shown to reflect exercise-induced oxidative stress, suggesting that salivary assays may provide a practical alternative to blood-based redox monitoring. Although research in this area remains preliminary, existing findings highlight saliva’s utility in capturing diet- and lifestyle-related physiological changes [108].

Salivary inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers have further demonstrated diagnostic potential in endocrine disorders. Opydo-Szymaczek et al. [109] reported that TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, uric acid, and testosterone exhibited high diagnostic accuracy for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), with pronounced elevations even among normal-weight adolescents. These results indicate that salivary biomarkers can detect low-grade inflammation and androgen dysregulation independent of adiposity, supporting their use in early, non-invasive screening of metabolic–inflammatory disturbances . Similarly, a recent systematic review revealed that individuals with metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO) consistently exhibit increased salivary concentrations of inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers, including 8-OHdG, IL-6, IL-8, resistin, TNFR1, PTX-3, AEA, OEA, TNF-α, and sICAM-1, suggesting that saliva may serve as an accessible indicator of obesity-related metabolic dysfunction and cardiometabolic risk [24]. Finally, salivary markers of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism show strong translational potential. In individuals with type 1 diabetes, salivary glucose, triglycerides, and cholesterol correlate significantly with corresponding serum levels, indicating that saliva can partially reflect systemic metabolic disturbances. These findings highlight salivary glucose and lipid markers as promising adjuncts to conventional blood-based assessments for monitoring glycemic control and dyslipidemia [110].

6. Integration of Diet, Oral Microbiota and Salivary Biomarkers in Nutritional Health Evaluation

Integrating information derived from diet, the oral microbiota, and salivary biomarkers offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how nutritional factors shape metabolic and inflammatory processes within the oral cavity [93]. Dietary intake directly modulates the availability of metabolic substrates for oral bacteria, driving shifts in microbial community structure and altering the production of key metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), lactate, volatile compounds, and free fatty acids [46]. These microbiota-mediated changes are subsequently mirrored in the salivary biochemical profile through measurable variations in metabolic, inflammatory, and antioxidant markers [111]. Consequently, saliva emerges as an integrative biological matrix capable of capturing both nutritional status and the host’s biological responses to dietary exposures.

Recent advances in salivary metabolomics further demonstrate that diet-induced alterations in oral microbial activity leave detectable metabolic signatures in saliva, strengthening its role as a non-invasive medium for integrating dietary exposures, microbial dysbiosis, and host inflammatory or metabolic responses [112]. This multidimensional perspective underscores the value of saliva not only as a reflection of local oral ecology but also as a window into systemic nutritional and metabolic adaptations.

Table 1 synthesizes evidence from population-based studies investigating how dietary exposures, ranging from macronutrient intake, sugar consumption, and meal timing to adherence to specific dietary patterns, modulate salivary biomarkers, oral microbial composition, and clinical oral health indicators across diverse demographic and geographic contexts. The included studies span children, adolescents, adults, and older populations, covering both healthy individuals and groups with specific conditions (e.g., obesity, type 2 diabetes, celiac disease). Reported salivary biomarkers include pH, flow rate, microbial diversity, inflammatory markers, metabolic compounds, and fatty acid profiles. Collectively, these findings highlight the capacity of dietary habits to alter oral and salivary biology, supporting the use of saliva as a non-invasive tool for monitoring diet–microbiome–health interactions.

Table 1.

Studies Evaluating the Impact of Dietary Factors on Salivary Biomarkers and Oral Health Outcomes.

7. Conclusions

Diet and environmental exposures exert profound and multidirectional effects on the oral microbiota, shaping not only local ecological dynamics but also broader metabolic and inflammatory responses with systemic relevance. The evidence reviewed demonstrates that dietary patterns rich in sugars and fermentable carbohydrates promote microbial dysbiosis, acidogenic metabolic activity, and reduced microbial diversity, whereas fiber-rich, plant-based and antioxidant-rich diets support a more balanced, health-associated oral ecosystem. At the same time, exposure to toxic heavy metals, including cadmium, lead, mercury, nickel and arsenic, emerges as an underappreciated disruptor of oral microbial homeostasis, capable of altering microbial structure, promoting inflammatory signaling, and impairing metabolic regulation even at low concentrations.

Saliva has proven to be a highly informative, non-invasive biological matrix that captures these complex interactions. Its composition integrates dietary inputs, microbial metabolic activity, host inflammatory responses and environmental toxicant exposure, making it a promising tool for early detection of nutritional imbalances and metabolic disturbances. Salivary biomarkers ranging from metabolites and oxidative stress indicators to inflammatory cytokines, trace metals and microbial signatures offer unique potential for real-time monitoring of diet–microbiome interactions and individualized metabolic risk. However, despite its promise, the translational implementation of saliva-based diagnostics remains limited by methodological heterogeneity, lack of standardized collection and analytical protocols, and insufficient longitudinal validation.

Overall, the integration of diet, oral microbiota composition, and salivary biomarkers offers a powerful conceptual and methodological framework for understanding how nutritional and environmental factors shape metabolic health. Strengthening this triadic model will advance early prevention, personalized nutritional interventions, and a deeper mechanistic understanding of the oral cavity as a sentinel for systemic well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.-N., A.L. and M.C.; methodology, L.A.-N. and A.L.; software, L.A.-N., validation A.L. and M.C.; formal analysis, L.A.-N.; investigation L.A.-N., A.L. and M.C.; resources, L.A.-N.; data curation, A.L. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.-N.; writing—review and editing, A.L. and M.C.; visualization, A.L. and M.C.; supervision, M.C., project administration, M.C., funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this narrative review. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bakr, M.M.; Caswell, G.M.; Al Ankily, M.; Zeitoun, S.I.; Ahmed, N.; Meer, M.; Shamel, M. Composition and Interactions of the Oral–Gastrointestinal Microbiome Populations During Health, Disease, and Long-Duration Space Missions: A Narrative Review. Oral 2025, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, J.; Du, N.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Q.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Meng, L.; Liu, X. Salivary Microbiome and Metabolome Analysis of Severe Early Childhood Caries. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghi, L.; DiMassa, V.; Harrington, A.; Lynch, S.V.; Kapila, Y.L. The Oral Microbiome: Role of Key Organisms and Complex Networks in Oral Health and Disease. Periodontol. 2000 2021, 87, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, W.; Qi, G.; Zhou, B.; Sun, Y. Diet-Microbiome Synergy: Unraveling the Combined Impact on Frailty through Interactions and Mediation. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.E.; Coffman, J.A.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Oral Pathogens’ Substantial Burden on Cancer, Cardiovascular Diseases, Alzheimer’s, Diabetes, and Other Systemic Diseases: A Public Health Crisis—A Comprehensive Review. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Anderson, A.; Woelber, J.P.; Karygianni, L.; Wittmer, A.; Hellwig, E. Examining the Composition of the Oral Microbiota as a Tool to Identify Responders to Dietary Changes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, A.; Modi, A.; Innocenti, G.; Zaro, V.; Conati Barbaro, C.; Ronchitelli, A.; Boschin, F.; Cavazzuti, C.; Dellù, E.; Radina, F.; et al. Ancient Oral Microbiomes Support Gradual Neolithic Dietary Shifts towards Agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassalle, F.; Spagnoletti, M.; Fumagalli, M.; Shaw, L.; Dyble, M.; Walker, C.; Thomas, M.G.; Bamberg Migliano, A.; Balloux, F. Oral Microbiomes from Hunter-gatherers and Traditional Farmers Reveal Shifts in Commensal Balance and Pathogen Load Linked to Diet. Mol. Ecol. 2018, 27, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Dipalma, G.; Guglielmo, M.; Palumbo, I.; Campanelli, M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; de Ruvo, E.; Palermo, A.; Di Venere, D.; Inchingolo, A.M. Correlation between Vegetarian Diet and Oral Health: A Systematic Review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 28, 2127–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, M.L.S.; Grote, V.; Baik, J.; Atallah, M.; Amato, K.R.; Ring, M. Effects of Vegetable and Fruit Juicing on Gut and Oral Microbiome Composition. Nutrients 2025, 17, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobon, B.; Musciotto, F.; Mira, A.; Greenacre, M.; Schlaepfer, R.; Aguileta, G.; Astete, L.H.; Ngales, M.; Latora, V.; Battiston, F.; et al. The Making of the Oral Microbiome in Agta Hunter–Gatherers. Evol. Hum. Sci. 2023, 5, e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Xuan, S.; Wang, Z. Oral Microbiota: A New View of Body Health. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2019, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, C.-M.; Radu, C.C.; Zaha, D.C. Salivary and Microbiome Biomarkers in Periodontitis: Advances in Diagnosis and Therapy—A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surdu, A.; Foia, L.G.; Luchian, I.; Trifan, D.; Tatarciuc, M.S.; Scutariu, M.M.; Ciupilan, C.; Budala, D.G. Saliva as a Diagnostic Tool for Systemic Diseases—A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ou, Y.; Fan, K.; Liu, G. Salivary Diagnostics: Opportunities and Challenges. Theranostics 2024, 14, 6969–6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, Y.Z.; Slavish, D.C. Measuring Salivary Markers of Inflammation in Health Research: A Review of Methodological Considerations and Best Practices. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 124, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Mumuni, A.N.; Tuason, R.T.S.; Maki, K.A. Methodological Considerations in Saliva-Based Biomarker Research: Addressing Patient-Specific Variability in Translational Research Protocols. Curr. Protoc. 2025, 5, e70235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.S.; Kong, E.F.; Rizk, A.M.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A. The Oral Microbiome: A Lesson in Coexistence. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presutti, L.; Gueningsman, M.C.; Fredericksen, B.; Smith, A.; Taylor, R.; Tuckett, A.; Folsom, C.; Wainwright, R.; Klena, C.; Ericsson, A.C.; et al. Exploring the Interplay Between Fatigue and the Oral Microbiome: A Longitudinal Approach. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, M.; Kato-Kogoe, N.; Sakaguchi, S.; Fukui, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Inoue, K.; Nakano, H.; Motooka, D.; Nakano, T.; et al. Comparative Evaluation of Microbial Profiles of Oral Samples Obtained at Different Collection Time Points and Using Different Methods. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 2779–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Kuehl, M.N.; Alman, A.C.; Burkhardt, B.R. Linking the Oral Microbiome and Salivary Cytokine Abundance to Circadian Oscillations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjandrawinata, R.R.; Amalia, N.; Tandi, Y.Y.P.; Athallah, A.F.; Afif Wibowo, C.; Aditya, M.R.; Muhammad, A.R.; Azizah, M.R.; Humardani, F.M.; Nojaid, A.; et al. The Forgotten Link: How the Oral Microbiome Shapes Childhood Growth and Development. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1547099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.J.F.; da Silva, C.V.F.; Cardoso, A.M.; de Oliveira Santos, E. Exploring Clinical Parameters and Salivary Microbiome Profiles Associated with Metabolic Syndrome in a Population of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 175, 106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habobe, H.A.; Pieters, R.H.H.; Bikker, F.J. Investigating the Salivary Biomarker Profile in Obesity: A Systematic Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, V.; Luchian, I.; Goriuc, A.; Budala, D.G.; Bida, F.C.; Cojocaru, C.; Butnaru, O.-M.; Virvescu, D.I. Salivary Biomarkers Identification: Advances in Standard and Emerging Technologies. Oral 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Chen, X.; Fu, Y. Salivary Analysis: An Emerging Paradigm for Non-invasive Healthcare Diagnosis and Monitoring. Interdiscip. Med. 2023, 1, e20230009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaderi, H.; Hegazi, F.; Al-Mulla, F.; Chiu, C.-J.; Kantarci, A.; Al-Ozairi, E.; Abu-Farha, M.; Bin-Hasan, S.; Alsumait, A.; Abubaker, J.; et al. Salivary Biomarkers as Predictors of Obesity and Intermediate Hyperglycemia in Adolescents. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 800373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, P.; Lin, Y.; Hu, S.; Cui, L. Saliva Metabolomics: A Non-Invasive Frontier for Diagnosing and Managing Oral Diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongiovanni, P.; Meroni, M.; Casati, S.; Goldoni, R.; Thomaz, D.V.; Kehr, N.S.; Galimberti, D.; Del Fabbro, M.; Tar-taglia, G.M. Salivary biomarkers: Novel noninvasive tools to diagnose chronic inflammation. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Y.; Pang, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, T. Toxic and Essential Metals: Metabolic Interactions with the Gut Microbiota and Health Implications. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1448388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezazadegan, M.; Forootani, B.; Hoveyda, Y.; Rezazadegan, N.; Amani, R. Major Heavy Metals and Human Gut Microbiota Composition: A Systematic Review with Nutritional Approach. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anchidin-Norocel, L.; Iatcu, O.C.; Lobiuc, A.; Covasa, M. Heavy Metal–Gut Microbiota Interactions: Probiotics Modulation and Biosensors Detection. Biosensors 2025, 15, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, J.A.; Choo-Kang, C.; Wang, L.; Issa, L.; Gilbert, J.A.; Ecklu-Mensah, G.; Luke, A.; Bedu-Addo, K.; Forrester, T.; Bovet, P.; et al. Toxic Metals Impact Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Risk in Five African-Origin Populations. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Luo, B.; Ruan, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Metal Exposure on the Structure and Co-Occurrence Patterns of the Oral Microbiota of Residents around a Mining Area. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1264619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcickiewicz, J.; Jamka, M.; Walkowiak, J. A Potential Link Between Oral Microbiota and Female Reproductive Health. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olate, P.; Martínez, A.; Sans-Serramitjana, E.; Cortés, M.; Díaz, R.; Hernández, G.; Paz, E.A.; Sepúlveda, N.; Quiñones, J. The Infant Oral Microbiome: Developmental Dynamics, Modulating Factors, and Implications for Oral and Systemic Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzidic, M.; Collado, M.C.; Abrahamsson, T.; Artacho, A.; Stensson, M.; Jenmalm, M.C.; Mira, A. Oral Microbiome Development during Childhood: An Ecological Succession Influenced by Postnatal Factors and Associated with Tooth Decay. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2292–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zuo, T.; Frey, N.; Rangrez, A.Y. A Systematic Framework for Understanding the Microbiome in Human Health and Disease: From Basic Principles to Clinical Translation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, J.J.; Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Bosco, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K. Oral Microbiome: A Review of Its Impact on Oral and Systemic Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.L.; Mark Welch, J.L.; Kauffman, K.M.; McLean, J.S.; He, X. The Oral Microbiome: Diversity, Biogeography and Human Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, C.; Song, Z. The Oral Microbiota: Community Composition, Influencing Factors, Pathogenesis, and Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 895537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra Nayak, S.; Latha, P.B.; Kandanattu, B.; Pympallil, U.; Kumar, A.; Kumar Banga, H. The Oral Microbiome and Systemic Health: Bridging the Gap Between Dentistry and Medicine. Cureus 2025, 17, e78918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, T. Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease: Maintaining a Healthy, Balanced Ecosystem and Reversing Dysbiosis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonocito, S.; Polizzi, A.; Isola, G. The Impact of Diet and Nutrition on the Oral Microbiome. In Oral Microbiome; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Berezovsky, B.; Bencko, V. Oral Health in a Context of Public Health: Prevention-Related Issue. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonov, G.E.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Livantsova, E.N.; Starodubova, A.V. The Complicated Relationship of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Oral Microbiome: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, R.R. Biofilm Architecture and Dynamics of the Oral Ecosystem. BioTechnologia 2024, 105, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostanghadiri, N.; Kouhzad, M.; Taki, E.; Elahi, Z.; Khoshbayan, A.; Navidifar, T.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Oral Microbiota and Metabolites: Key Players in Oral Health and Disorder, and Microbiota-Based Therapies. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1431785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, Z.E.; Tengilimoglu-Metin, M.M.; Oğuz, N.; Kizil, M. Is Inflammatory Potential of the Diet Related to Oral and Periodontal Health? Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7155–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angarita-Díaz, M.d.P.; Fong, C.; Bedoya-Correa, C.M.; Cabrera-Arango, C.L. Does High Sugar Intake Really Alter the Oral Microbiota?: A Systematic Review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2022, 8, 1376–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennert, C.; Reinmuth, A.; Bremer, K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Karygianni, L.; Hellwig, E.; Vach, K.; Ratka-Krüger, P.; Wittmer, A.; Woelber, J.P. An Oral Health Optimized Diet Reduces the Load of Potential Cariogenic and Periodontal Bacterial Species in the Supragingival Oral Plaque: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Microbiologyopen 2020, 9, e1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, K.; Ishikado, A.; Morino, K.; Nishio, Y.; Ugi, S.; Kajiwara, S.; Kurihara, M.; Iwakawa, H.; Nakao, K.; Uesaki, S.; et al. A High-Fiber, Low-Fat Diet Improves Periodontal Disease Markers in High-Risk Subjects: A Pilot Study. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcangi, G.; Patano, A.; Ciocia, A.M.; Netti, A.; Viapiano, F.; Palumbo, I.; Trilli, I.; Guglielmo, M.; Inchingolo, A.D.; Dipalma, G.; et al. Benefits of Natural Antioxidants on Oral Health. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstens, R.; Ng, Y.Z.; Pettersson, S.; Jayaraman, A. Balancing the Oral–Gut–Brain Axis with Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappe, C.L.; Lutzenberger, S.; Goebler, K.; Meier, S.; Jeitler, M.; Michalsen, A.; Dommisch, H. Effect of a Whole-Food Plant-Based Diet on Periodontal Parameters in Patients With Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Secondary Sub-Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 52, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galchenko, A. V Impact Of Vegetarianism and Veganism On Oral Health. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 8, 2265–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Li, T.; Xie, S.; Huang, S. Dietary Inflammatory Index Mediates the Association between Planetary Health Diet Index and Periodontitis. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchingolo, F.; Inchingolo, A.M.; Malcangi, G.; De Leonardis, N.; Sardano, R.; Pezzolla, C.; de Ruvo, E.; Di Venere, D.; Palermo, A.; Inchingolo, A.D.; et al. The Benefits of Probiotics on Oral Health: Systematic Review of the Literature. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarlucea-Jerez, M.; Monnoye, M.; Chambon, C.; Gérard, P.; Licandro, H.; Neyraud, E. Fermented Food Consumption Modulates the Oral Microbiota. npj Sci. Food 2024, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Mannaa, M. Fermented Foods as Functional Systems: Microbial Communities and Metabolites Influencing Gut Health and Systemic Outcomes. Foods 2025, 14, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagakubo, D.; Kaibori, Y. Oral Microbiota: The Influences and Interactions of Saliva, IgA, and Dietary Factors in Health and Disease. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.H.; Kern, T.; Bak, E.G.; Kashani, A.; Allin, K.H.; Nielsen, T.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O. Impact of a Vegan Diet on the Human Salivary Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeler, M.; Ellero-Simatos, S.; Birkner, T.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Olsson, L.; Brolin, H.; Loeber, U.; Kraft, J.D.; Polizzi, A.; Martí-Navas, M.; et al. The Interplay between Dietary Fatty Acids and Gut Microbiota Influences Host Metabolism and Hepatic Steatosis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rudkowska, I. Dietary Lipids, Gut Microbiota, and Their Metabolites: Insights from Recent Studies. Nutrients 2025, 17, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porru, S.; Esplugues, A.; Llop, S.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M. The Effects of Heavy Metal Exposure on Brain and Gut Microbiota: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pei, S.; Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Ruan, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhang, L.; Niu, J.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Heavy Metal Exposure on the Species Diversity, Functional Diversity, and Network Structure of Oral Mycobiome. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feyisa, G.; Mekassa, B.; Merga, L.B. Human Health Risks of Heavy Metals Contamination of a Water-Soil-Vegetables Farmland System in Toke Kutaye of West Shewa, Ethiopia. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Andronic, O.; Lăcraru, A.-E.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Negrei, C.; Olteanu, G. Assessing Heavy Metal Contamination in Food: Implications for Human Health and Environmental Safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, D.; Słowik, J.; Chilicka, K. Heavy Metals and Human Health: Possible Exposure Pathways and the Competition for Protein Binding Sites. Molecules 2021, 26, 6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, F.; Binte Abdullah, R.; Nur E Alam, M.; Anik, A.H. Unsafe to Eat? A Systematic Review of Heavy Metal Contamination in Urban Street Foods: Sources, Risks, and Regional Disparities. Meas. Food 2025, 20, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, C.J.; Cao, K.L.; Hughes, T.; Kumar, P.; Austin, C. How Does the Early Life Environment Influence the Oral Microbiome and Determine Oral Health Outcomes in Childhood? BioEssays 2021, 43, 2000314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, G.; Li, Y.; He, X.; Cowan, A.; Tanner, A.C.R. The Evolving Microbiome of Dental Caries. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademe, D.; Admassu, D.; Balakrishnan, S. Analysis of Salivary Level Lactobacillus spp. and Associated Factors as Determinants of Dental Caries amongst Primary School Children in Harar Town, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Pei, S.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Luo, B.; Ruan, Y.; et al. The Impact of Interactions between Heavy Metals and Smoking Exposures on the Formation of Oral Microbial Communities. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1502812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qi, T.; Yao, L.; Wang, W.; Yu, F.; Yan, Y.; Salama, E.-S.; Su, S.; Bai, M. Influence of Environmental Factors on Salivary Microbiota and Their Metabolic Pathway: Next-Generation Sequencing Approach. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Li, T.; Yu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, S.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Effects of Subchronic Oral Toxic Metal Exposure on the Intestinal Microbiota of Mice. Sci. Bull. 2017, 62, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarquoy, J. Trace Metals in Modern Technology and Human Health: A Microbiota Perspective on Cobalt, Lithium, and Nickel. Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.; Bakulski, K.M.; Goodrich, J.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Marazita, M.L.; Foxman, B. Low Levels of Salivary Metals, Oral Microbiome Composition and Dental Decay. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Liao, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, L. Metal(Loid)-Gut Microbiota Interactions and Microbiota-Related Protective Strategies: A Review. Environ. Int. 2024, 192, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Juan, H.; Alvaro, P.-F. Mineral and Trace Element Analysis of Saliva from Patients with BMS: A Cross-Sectional Prospective Controlled Clinical Study. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2014, 43, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xin, Y.; Zong, W.; Li, X. The Role of Oral Microbiota in Digestive System Diseases: Current Advances and Perspectives. J. Oral Microbiol. 2025, 17, 2566403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Cui, J.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. The Oral-Gut Microbiota Axis: A Link in Cardiometabolic Diseases. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Yuan, Y.; Xie, Q.; Dong, Z. Relationship between Human Oral Microbiome Dysbiosis and Neuropsychiatric Diseases: An Updated Overview. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 471, 115111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Cheng, L.; You, Y.; Tang, C.; Ren, B.; Li, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X. Oral Microbiota in Human Systematic Diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.; Hernández-Lemus, E. Periodontal Inflammation and Systemic Diseases: An Overview. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 709438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; Saltiel, A.R. Inflammatory Links between Obesity and Metabolic Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, C.; Avenell, A. The Effect of Dietary Weight-loss Interventions on the Inflammatory Markers Interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha in Adults with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Calderon, J.R.; Cuellar-Tamez, R.; Castillo, E.C.; Luna-Ceron, E.; García-Rivas, G.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L. Metabolic Shift Precedes the Resolution of Inflammation in a Cohort of Patients Undergoing Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schamarek, I.; Anders, L.; Chakaroun, R.M.; Kovacs, P.; Rohde-Zimmermann, K. The Role of the Oral Microbiome in Obesity and Metabolic Disease: Potential Systemic Implications and Effects on Taste Perception. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menafra, D.; Proganò, M.; Tecce, N.; Pivonello, R.; Colao, A. Diet and Gut Microbiome: Impact of Each Factor and Mutual Interactions on Prevention and Treatment of Type 1, Type 2, and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Hum. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 38, 200286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihelgas, S.; Ehala-Aleksejev, K.; Adamberg, S.; Kazantseva, J.; Adamberg, K. The Gut Microbiota of Healthy Individuals Remains Resilient in Response to the Consumption of Various Dietary Fibers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefura, T.; Zapała, B.; Gosiewski, T.; Skomarovska, O.; Dudek, A.; Pędziwiatr, M.; Major, P. Differences in Compositions of Oral and Fecal Microbiota between Patients with Obesity and Controls. Medicina 2021, 57, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, J.; Gund, M.; Becker, S.L.; Hannig, M.; Rupf, S.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Keller, A.; Molano, L.-A.G.; Keller, V. Joint Bacterial Traces in the Gut and Oral Cavity of Obesity Patients Provide Evidence for Saliva as a Rich Microbial Biomarker Source. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Aljabri, M.Y.; Dawood, T.; Khan, S.S.; Gupta, B.; Vempalli, S.; Hassan, A.A.-H.A.-A.; Elamin, N.M.H. Exploring the Interplay: Oral–Gut Microbiome Connection and the Impact of Diet and Nutrition. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2024, 13, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, M.; Drab, Z.; Dąbrowska, M.; Samborowska, E.; Żeber-Lubecka, N.; Kulecka, M.; Klupa, T.; Gregorczyk-Maga, I. Impact of Diet and Nutritional Status on Gingival Crevicular Fluid Metabolome and Microbiome in People with Type 1 Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcham, Z.M.; Garneau, N.L.; Comstock, S.S.; Tucker, R.M.; Knight, R.; Metcalf, J.L.; Miranda, A.; Reinhart, B.; Meyers, D.; Woltkamp, D.; et al. Patterns of Oral Microbiota Diversity in Adults and Children: A Crowdsourced Population Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Fan, Y.; Shan, G.; Chen, X. Oral Microbiome Contributions to Metabolic Syndrome Pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1630828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiten, D.J.; Combs, G.F.; Steiber, A.L.; Bremer, A.A. Perspective: Nutritional Status as a Biological Variable (NABV): Integrating Nutrition Science into Basic and Clinical Research and Care. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Youn, S.; Min, J.W.; Ko, E.J. Nutritional Status Evaluation and Intervention in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: Practical Approach. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogova, S.; Plotnikova, O.; Kalishev, M.; Nukeshtayeva, K.; Bolatova, Z.; Galayeva, A. Diabetes, Iron-Deficiency Anemia, and Endocrine, Nutritional, and Metabolic Disorders in Children: A Socio-Epidemiological Study in Urban Kazakhstan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.L. Overview of Dietary Assessment Methods for Measuring Intakes of Foods, Beverages, and Dietary Supplements in Research Studies. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 70, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.; Wallace, S.M.; Woodside, J.V.; McKenna, G. The Potential of Salivary Biomarkers of Nutritional Status and Dietary Intake: A Systematic Review. J. Dent. 2021, 115, 103840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, L.T.; Mandal, C.K.; Patolsky, F. Body Biofluids for Minimally-Invasive Diagnostics: Insights, Challenges, Emerging Technologies, and Clinical Potential. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, e03096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakanaka, A.; Kuboniwa, M.; Katakami, N.; Furuno, M.; Nishizawa, H.; Omori, K.; Taya, N.; Ishikawa, A.; Mayumi, S.; Tanaka Isomura, E.; et al. Saliva and Plasma Reflect Metabolism Altered by Diabetes and Periodontitis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 742002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balto, H.; Al-Hadlaq, S.; Alhadlaq, A.; El-Ansary, A. Gum-Gut Axis: The Potential Role of Salivary Biomarkers in the Diagnosis and Monitoring Progress of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Saudi Dent. J. 2023, 35, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.M.; Costa, G.V.A.M.; Lopes, G.B.; Rodrigues, E.M.F.; Castro, G.B.M. de O Uso de Biomarcadores Salivares Para Monitorização Das Alterações Metabólicas Ocasionadas Pelo Exercício Físico—Uma Revisão Da Literatura. Res. Soc. Dev. 2024, 13, e1513645943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.; Wallace, S.M.; Woodside, J.; McKenna, G. Salivary Biomarkers of Nutritional Status: A Systematic Review. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Omaye, S. Use of Saliva Biomarkers to Monitor Efficacy of Vitamin C in Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opydo-Szymaczek, J.; Wendland, N.; Formanowicz, D.; Blacha, A.; Jarząbek-Bielecka, G.; Radomyska, P.; Kruszyńska, D.; Mizgier, M. A Pilot Study of the Role of Salivary Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of PCOS in Adolescents Across Different Body Weight Categories. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheprasova, A.A.; Popov, S.S.; Pashkov, A.N.; Verevkin, A.N.; Kryl’skii, E.D.; Mittova, V.O. Oxidative Status, Carbohydrate, and Lipid Metabolism Indicators in Saliva and Blood Serum of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2022, 9, 5233–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-S.; Kook, J.-K.; Park, S.-N.; Lim, Y.K.; Choi, G.H.; Kim, S.; Ji, S. Salivary Microbiota Reflecting Changes in Subgingival Microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, R.; Hu, S.; Cui, L. Advancements and Challenges in Salivary Metabolomics for Early Detection and Monitoring of Systemic Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan Gönül, B.; Delikan, E.; Çiçek, B.; Yılmaz Cankılıç, M. Associations of Salivary Microbiota with Diet Quality, Body Mass Index, and Oral Health Status in Turkish Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, S.; Zilm, P.; Jamieson, L.; Santiago, P.H.R.; Ketagoda, D.H.K.; Weyrich, L. The Influence of Diet, Saliva, and Dental History on the Oral Microbiome in Healthy, Caries-Free Australian Adults. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Estebaranz, N.; Muñoz-González, C.; Gil-Valcárcel, A.M.; Calvo López-Dávalos, P.; Martín-Vacas, A.; Paz-Cortés, M.M.; Aragoneses, J.M. Salivary Microbiota Profile in Adult and Children Population According to Active Dentin Caries: A Metagenomic Preliminary Analysis. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1599925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaalan, A.; Lee, S.; Feart, C.; Garcia-Esquinas, E.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Lopez-Garcia, E.; Morzel, M.; Neyraud, E.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Streich, R.; et al. Alterations in the Oral Microbiome Associated With Diabetes, Overweight, and Dietary Components. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 914715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommi, S.; Manzoor, M.; Engberg, E.; Agrawal, N.; Lakka, T.A.; Leinonen, J.; Kolho, K.-L.; Viljakainen, H. The Composition and Functional Capacities of Saliva Microbiota Differ Between Children With Low and High Sweet Treat Consumption. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Monson, K.R.; Peters, B.A.; Whittington, J.M.; Um, C.Y.; Oberstein, P.E.; McCullough, M.L.; Freedman, N.D.; Huang, W.-Y.; Ahn, J.; et al. Altered Salivary Microbiota Associated with High-Sugar Beverage Consumption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, D.; Cosi, A.; Valloreo, R.; Fulco, D.; Tieri, M.; Alberi Auber, L.; D’Ercole, S. Association between Salivary/Microbiological Parameters, Oral Health and Eating Habits in Young Athletes. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2025, 22, 2443018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercolini, D.; Francavilla, R.; Vannini, L.; De Filippis, F.; Capriati, T.; Di Cagno, R.; Iacono, G.; De Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. From an Imbalance to a New Imbalance: Italian-Style Gluten-Free Diet Alters the Salivary Microbiota and Metabolome of African Celiac Children. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 18571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, M.; Erbiti, S.; Delgado, A.; Cardenas, I.L. Evaluation of Oral Microbiota in Undernourished and Eutrophic Children Using Checkerboard DNA-DNA Hybridization. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, K.; Hornemann, S.; Rudovich, N.; Weber, D.; Grune, T.; Kramer, A.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Pivovarova-Ramich, O. Saliva Samples as A Tool to Study the Effect of Meal Timing on Metabolic And Inflammatory Biomarkers. Nutrients 2020, 12, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.