Abstract

Fisetin (3,3′,4′,7-tetrahydroxyflavone) is a naturally occurring flavonol in fruits and vegetables. It exhibits diverse biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, senolytic, and lipid-lowering properties. This review explores the molecular mechanisms underlying fisetin’s hepatoprotective effects and evaluates its potential application in Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease (IFALD), a severe complication associated with total parenteral nutrition (TPN). IFALD is characterized by inflammation, cholestasis, steatosis, oxidative stress, and dysregulated lipid and bile acid metabolism. Fisetin modulates several key signaling pathways, including NF-κB, Nrf2, AMPK, and SIRT1, leading to reduced inflammatory cytokine expression, enhanced antioxidant defenses, and improved lipid homeostasis. Fisetin shows potential anti-fibrotic and microbiota-modulating effects. More importantly, fisetin is recognized as a potent senolytic agent, selectively activating pro-apoptotic pathways in senescent cells, which are known sources of inflammation and tissue damage. However, despite its promising pharmacological profile, the poor bioavailability of fisetin remains a significant limitation, particularly for parenteral use. Emerging drug delivery systems such as liposomes and nanoparticles offer potential solutions. Given its broad spectrum of beneficial effects and favorable safety profile, fisetin represents a compelling candidate for future studies in the prevention and management of IFALD.

1. Introduction

Fisetin is a naturally occurring flavonol that has attracted increasing attention due to its diverse biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective, and senolytic properties [1]. Recent reviews and experimental studies published within the past three years have expanded the understanding of fisetin’s biological properties, highlighting its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, metabolic, and senotherapeutic potential [2,3,4]. In particular, recent work has demonstrated that fisetin improves insulin sensitivity, reduces hepatic lipid accumulation, modulates redox signaling, and attenuates inflammatory responses in metabolic liver disorders [5,6]. These new findings strengthen the rationale for investigating fisetin as a therapeutic candidate in liver diseases with inflammatory and metabolic components.

The pleiotropic biological actions of fisetin are attributable to its ability to modulate multiple conserved cellular pathways. Its antioxidant effects arise from direct radical-scavenging activity mediated by hydroxyl groups on the flavone backbone, as well as indirect antioxidant responses through activation of the Nrf2 pathway [7,8]. Fisetin’s anti-inflammatory properties are driven mainly by suppression of NF-κB signaling and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation [9]. Neuroprotective effects result from its capacity to reduce ROS accumulation, stabilize mitochondrial function, and modulate ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathways [10]. Importantly, fisetin exerts senolytic activity by selectively inducing apoptosis in senescent cells through coordinated inhibition of NF-κB and activation of p53, thereby reducing SASP secretion [3].

Additionally, fisetin has shown promise in a variety of other liver pathologies, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [11,12,13,14], alcoholic liver disease (ALD) [5,6], drug-induced liver injury (DILI) [15,16,17], and hepatic fibrosis [11], further supporting its broad hepatoprotective profile. In the following sections, we will discuss how these diverse mechanisms of fisetin intersect with the pathophysiological features of Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease (IFALD), emphasizing its potential therapeutic relevance in this specific liver condition. IFALD is a form of liver dysfunction associated with total parenteral nutrition (TPN) administration. Typically developing after approximately two weeks of TPN, IFALD affects nearly half of adult patients undergoing prolonged parenteral nutrition [18]. It is characterized by inflammation, cholestasis, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis, frequently accompanied by dyslipidemia and impaired bile acid homeostasis [19]. Clinically, IFALD manifests through elevated serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and total bilirubin [20]. Numerous strategies have been explored to mitigate IFALD, including modifications to lipid emulsions (e.g., fish oil-based formulations) [21], bile acid modulators, and the administration of antibiotics [21,22]. Although several preventive and therapeutic strategies are currently tested in clinical practice—including UDCA, optimized lipid emulsions, and infection management—none provide consistently effective or comprehensive protection against IFALD. Therefore, the condition still lacks a definitive, broadly effective therapy.

This review aims to evaluate the role of fisetin in the context of liver diseases with inflammatory and metabolic components and assess its potential therapeutic application in preventing and treating IFALD.

2. Fisetin Overview

Fisetin (3,3′,4′,7-tetrahydroxyflavone) is a naturally occurring flavonol in various fruits and vegetables, including apples, strawberries, grapes, tomatoes, onions, and cucumbers. Among these, strawberries are considered one of the richest natural sources, containing up to 160 μg/g of fisetin [1,23]. Its widespread presence in edible plants contributes to its accessibility as a dietary supplement and a subject of pharmacological interest.

Chemically, fisetin is characterized by a flavone backbone with four hydroxyl groups at positions 3, 7, 3′, and 4′. Its molecular formula is C15H10O6, and its structure consists of two benzene rings (A and B) connected via a three-carbon bridge, forming a closed pyrone ring (C). The hydroxyl groups enhance its antioxidant properties by enabling free radical scavenging and metal ion chelation [24,25]. This structure also facilitates interactions with various cellular targets, which underlie many of fisetin’s biological activities [1].

Fisetin has attracted increasing attention due to its diverse biological properties, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant [24], neuroprotective [10], anti-aging [3], and anti-cancer effects [26]. Despite these promising activities, its clinical utility is limited by poor water solubility, high lipophilicity, and low oral bioavailability. After oral administration, fisetin is rapidly metabolized through phase II processes, primarily via glucuronidation and sulfation in the liver and intestines, resulting in the predominance of conjugated metabolites in plasma [27].

Notably, fisetin is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and can cross the blood–brain barrier, making it an attractive candidate for neuroprotective therapies. However, its limited systemic availability has prompted the development of various formulation strategies to enhance absorption and biological efficacy, including fisetin-loaded nanoparticles, liposomes, and inclusion complexes with cyclodextrins [23]. These delivery systems improve solubility, protect fisetin from metabolic degradation, and facilitate more efficient transport across biological membranes [1]. While the mechanisms governing fisetin’s cellular uptake and distribution are not fully understood, they likely involve interactions with specific transporter proteins [10].

Preclinical toxicological studies suggest that fisetin has a favorable safety profile. Animal studies have shown low acute toxicity and minimal adverse effects at therapeutically relevant doses. Higher doses may cause gastrointestinal discomfort or hepatic stress, though these effects have been observed mainly in rodent models [3].

Preclinical studies indicate that fisetin has a favorable safety profile. In rodent models, oral doses ranging from 10 to 100 mg/kg/day and intraperitoneal doses of 10 to 40 mg/kg were well tolerated, with minimal adverse effects [5,6,15,16,17,28]. Human supplementation studies typically employ oral doses between 20 and 100 mg/day, with ongoing clinical trials investigating senolytic activity using intermittent high-dose regimens (e.g., 20 mg/kg/day for 2–3 days) [4]. Reported adverse effects are rare and generally limited to mild gastrointestinal discomfort. However, higher parenteral doses may increase hepatic metabolism and transient hepatocellular stress, underscoring the need for optimized formulation strategies for intravenous delivery.

Fisetin has not demonstrated mutagenic, genotoxic, or carcinogenic properties in standard laboratory assays. In vitro research further supports its safety, showing no significant cytotoxicity in non-cancerous cell lines at physiologically relevant concentrations. Nonetheless, fisetin may exhibit pro-oxidant behavior at higher doses or alter the activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes, suggesting potential interactions with other compounds. Importantly, recent studies have indicated that fisetin successfully targets some senescent cells in humans, particularly reducing the number of senescent peripheral blood mononuclear cells and thereby reducing levels of senescent-associated secretory phenotypes (SASP) [29]. There are also several pending clinical trials for a variety of human diseases [4]. However, there is a continuous need to improve understanding of the detailed mechanism of action, as well as to enhance bioavailability and stability during treatment.

The extensive attention in basic and clinical research suggests that fisetin shows strong potential as a nutraceutical and therapeutic agent. However, further comprehensive studies, particularly in humans and sensitive populations such as pregnant individuals or those with liver dysfunction, are essential to fully establish its long-term safety and tolerability [30].

3. Methodology

A literature review was conducted to summarize and critically discuss current evidence on the effects of fisetin in the context of liver function and hepatic pathology. The literature search was performed on 13 January 2025, using the PubMed and Scopus databases. In PubMed, all available fields were searched, whereas in Scopus the search was limited to titles, abstracts, and keywords. The search strategy included combinations of the following terms: “fisetin” AND “liver”, “fisetin” AND “hepatotoxicity”, “fisetin” AND “liver injury”, “fisetin” AND “cholestasis”, as well as terms related to inflammation and oxidative stress.

The search was restricted to original research articles published in English between 2015 and 2025. Studies were considered eligible if they investigated fisetin as a single bioactive compound in relation to hepatoprotection, liver injury, or liver-related molecular and cellular mechanisms, and if they reported measurable biochemical, molecular, or histological outcomes. Review articles, conference abstracts, commentaries, and studies in which fisetin was administered in combination with other compounds without the possibility of isolating its individual effects were excluded. Additionally, studies that did not directly address hepatic mechanisms or focused primarily on hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury, with limited mechanistic relevance to the scope of this review, were not considered.

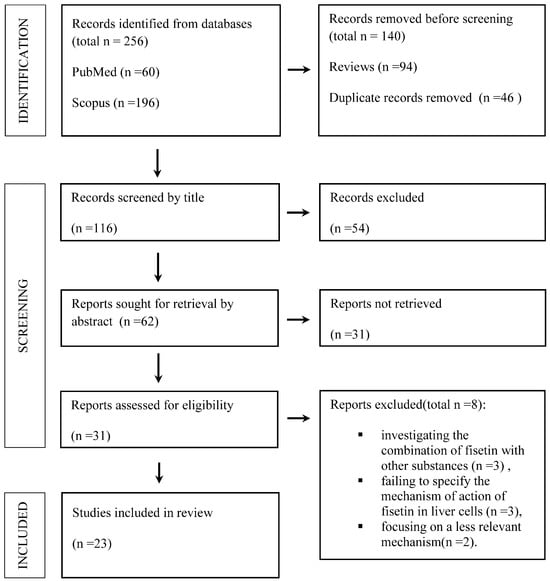

A total of 256 records were retrieved from the initial database search (60 from PubMed and 196 from Scopus). After the removal of duplicate entries and non-eligible publication types, the remaining studies were examined for relevance. Screening of titles and abstracts allowed for the exclusion of clearly unrelated articles, and a subset of publications was subsequently assessed in full text. During full-text evaluation, several studies were excluded because fisetin was administered in combination with other agents, the hepatic mechanism of action was not sufficiently defined, or the experimental focus was limited to ischemia–reperfusion injury with marginal relevance to the objectives of this review. An overview of the literature search and study selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flowchart showing the results of screening and literature searches.

4. Molecular Basis of Fisetin’s Hepatoprotective Activity

Fisetin exhibits a multifaceted hepatoprotective profile, targeting several key pathological processes associated with liver injury (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of research on fisetin’s hepatoprotective properties.

4.1. Inhibition of NF-κB and Inflammatory Signaling

Fisetin inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of inflammation. It downregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-18 [31,34,37,38,40], and reduces levels of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [34]. Additionally, fisetin interferes with the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex, further mitigating hepatic inflammatory responses [39,41].

4.2. Senolytic Action Through Induced Apoptosis

In response to intra- or extracellular stress, cells can enter a state of senescence, recognized as a stable cell cycle arrest through upregulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors including p16INK4a, p21CIP1/WAF1, and p15INK4b. Despite cell cycle arrest, senescent cells produce and secrete SASP, composed mainly of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1, IL-8, TNF-α, PAI-1, and CXCL-2. Fisetin exhibits senolytic activity by inducing apoptosis through various signaling pathways, but in vitro studies showed that it targets senescent cells selectively with no pro-apoptotic action in non-senescent, healthy cells [44]. It was shown that in senescent cells, fisetin simultaneously inhibits the NF-κB pathway and activates the p53 signaling pathway. The other signaling pathways associated with apoptosis induced by fisetin also involve inhibition of HSF1 activity, ERK1/2 activation, and targeting the PI3K pathway. Previous rodent studies showed that the senolytic action of fisetin improves lifespan and healthspan in mice [44].

4.3. Activation of Nrf2 and Antioxidant Defense

Fisetin activates the Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2) pathway [39], leading to increased expression of antioxidant enzymes including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) [43], superoxide dismutase (SOD), NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) [36], and glutathione-related enzymes (GPX1, GSR, GSH) [32,33,34]. This enhances the liver’s capacity to counteract oxidative stress and maintain redox homeostasis.

4.4. Regulation of Lipid Metabolism via AMPK, SIRT1, and PPAR Pathways

Fisetin regulates lipid homeostasis by activating AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [42] and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). These pathways suppress lipogenic transcription factors such as sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1C (SREBP-1C) and enzymes like stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1) [12,28]. Concurrently, fisetin promotes fatty acid β-oxidation via upregulation of PPARα and reduces cholesterol biosynthesis by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) and Acyl-CoA: Cholesterol Acyltransferase (ACAT) [11].

4.5. Anti-Fibrotic Action Through TGF-β Pathway Suppression

Fisetin attenuates fibrotic progression by downregulating transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1) and associated fibrosis markers, including alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9), and their inhibitors. These effects limit extracellular matrix deposition and hepatic scarring [5,16].

4.6. Modulation of Gut Microbiota Composition

Fisetin positively influences the gut microbiome by enhancing the abundance of beneficial microbial species, such as Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium breve. These changes contribute to improved gut barrier function and reduced translocation of endotoxins like lipopolysaccharides (LPS), alleviating liver inflammation and promoting systemic metabolic health [35]. Together, these mechanisms establish fisetin as a promising candidate for treating liver diseases characterized by inflammation, oxidative stress, dyslipidemia, and fibrosis.

The following section will contextualize these molecular actions within the complex pathogenesis of IFALD, with particular attention to the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial stress, and impaired antioxidant defenses—hallmarks of parenteral nutrition-induced liver injury.

Beyond the mechanisms summarized above, several recent studies further support fisetin’s hepatoprotective potential. Fisetin has been shown to suppress ER stress by reducing GRP78 signaling and restoring mitochondrial membrane potential [36]. It also regulates autophagy, a key survival pathway in hepatotoxic injury, by promoting LC3-II conversion and inhibiting mTOR activation in APAP-induced liver damage models [17]. Additionally, fisetin attenuates hepatocyte apoptosis by modulating the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and caspase-3 activity, thereby limiting parenchymal cell loss [34]. Together, these mechanisms highlight the broad spectrum of cytoprotective effects of fisetin in hepatic injury.

In addition, fisetin influences several interconnected signaling networks that collectively contribute to hepatoprotection. Beyond inhibiting NF-κB activation by suppressing IKKβ phosphorylation and stabilizing IκBα, fisetin enhances the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 by preventing Keap1-mediated degradation. Through AMPK and SIRT1 activation, increase the AMP/ATP ratio, promotes fatty acid β-oxidation, and suppresses lipogenesis. Moreover, by modulating p53–p21 signaling and reducing SASP-related cytokines, fisetin exhibits senolytic properties that may alleviate chronic inflammation within hepatic tissue. These complementary actions underline the multifactorial nature of fisetin’s hepatoprotective profile.

5. Pathomechanism of IFALD

The pathological mechanisms underlying IFALD are complex and multifactorial. Several factors contribute to its development, including phytosterols, central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), gut dysbiosis, oxidative stress, and prolonged inflammation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors leading to the development of IFALD.

Phytosterols, present in the vegetable oils (primarily soybean oil) used in parenteral nutrition (PN) emulsions, are a key PN-dependent factor. These compounds structurally resemble cholesterol and disrupt its metabolism by inhibiting the liver’s farnesoid X receptor (FXR), leading to increased production of bile acids and triglycerides. Excess bile acids are usually exported via hepatic bile transporters into the intestinal lumen, where they activate intestinal FXR, triggering a negative feedback loop (mediated by FGF19 and FGFR4) that suppresses further bile acid synthesis [45]. However, in the presence of LPS, a second important factor, this balance is disturbed.

LPS induces liver inflammation by binding to TLR4 receptors on Kupffer cells, activating the NF-κB pathway, and promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Inflammatory conditions impair the function of bile acid transporters, hindering bile acid efflux from the liver, disrupting the negative feedback mechanism, and contributing to intrahepatic cholestasis. LPS can originate from bloodstream infections associated with central venous catheters or gut dysbiosis, both of which are common in patients receiving PN. Reduced or absent enteral feeding promotes gut microbial imbalances, favoring the overgrowth of Gram-negative bacteria, such as Bacteroidaceae and Enterobacteriaceae, which further increases endotoxin production and hepatic injury. Prolonged PN use is associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-6, and the profibrotic factor TGF-β [46]. The lipid emulsions used in PN, particularly those rich in omega-6 fatty acids, contribute significantly to this inflammatory state. Omega-6 fatty acids are precursors for pro-inflammatory eicosanoids and can directly stimulate cytokine production. Furthermore, omega-6-rich emulsions may mimic LPS activity by activating the TLR4 signaling pathway [47]. Studies have demonstrated that LPS stimulation downregulates FXR mRNA levels in the liver [51], removing its normal suppressive effect on NF-κB and thereby amplifying inflammation [52]. Higher levels of TNF-α and IL-6 have been documented in animals receiving PN [19], reinforcing the link between PN and liver inflammation. Oxidative stress is another central mechanism in IFALD pathogenesis. In the setting of TPN, excessive ROS production overwhelms the hepatocyte antioxidant defenses, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Lipid-rich PN formulations, particularly those high in omega-6 fatty acids, exacerbate oxidative stress by promoting lipid peroxidation and activating pro-inflammatory pathways.

Studies have shown that PN reduces the expression of genes involved in antioxidant defense, including Gstp1, Gstm1, Nqo1, Ho-1, and Gclc, in mice receiving Intralipid-based emulsions [48]. In neonatal pig models, TPN was associated with GPX1 hypermethylation and decreased mRNA expression of GPX1, GCLC, and galactosylceramide sulfotransferase (GSase). In contrast, supplementation with glutathione (GSH) prevented these changes and enhanced the expression of Nrf2 and SOD2 [49]. These findings suggest that PN-induced oxidative stress results from excessive nutrient infusion and suppression of endogenous antioxidant systems, contributing to hepatic steatosis, cholestasis, and fibrosis. Parenteral nutrition also disrupts lipid and bile acid metabolism. PN-fed animals exhibit increased hepatic lipid accumulation, which is associated with the upregulated expression of lipogenic genes such as SREBP-1C, FAS, LPL, and SCD1 [50]. Persistent inflammation and oxidative stress further drive the progression from steatosis to liver fibrosis. Elevated levels of TGF-β and MMP-9 in the context of IFALD contribute to extracellular matrix remodeling and fibrogenesis, ultimately leading to irreversible liver damage [53].

6. The Potential Role of Fisetin in Preventing and Treating IFALD

As noted in the Introduction Section, treatment strategies for IFALD are limited. Many strategies for preventing and treating IFALD have been explored, and these generally involve modifying the PN regimen. Such modifications include adjusting the duration of nutrition and changing the composition of the PN solution, often by incorporating fish oil-based lipid emulsions.

However, none of these nutritional strategies are considered universally effective or sufficient on their own. Pharmacological therapies, such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) or ursodiol, phenobarbital, metronidazole, erythromycin, and cholecystokinin-octapeptide, have also been investigated. Although these drugs were tested in various clinical trials, none are currently established or widely used as standard pharmacological treatments for IFALD [54,55].

IFALD involves chronic activation of inflammatory pathways, notably via NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6 [46,51]. Fisetin mitigates this response by suppressing NF-κB activation and the subsequent expression of downstream cytokines. Its additional inhibition of TGF-β signaling suggests a role in halting or reversing fibrosis. The particular advantage of fisetin lies in its ability to simultaneously target the inflammatory, oxidative, metabolic, and fibrotic components of IFALD. This multimodal approach is particularly relevant given the multifactorial pathogenesis of the disease, in which interventions targeting a single mechanism often fail to provide sufficient clinical benefit.

Central to this pathology is oxidative stress, driven by the excessive production of ROS. TPN formulations rich in omega-6 fatty acids exacerbate ROS generation and lipid peroxidation, overwhelming hepatic antioxidant defenses and inducing mitochondrial and ER stress. Fisetin counters these effects by activating the Nrf2 pathway, which enhances the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1, SOD, GPX1, and glutathione-related proteins. This response restores redox balance and protects hepatocytes from ROS-mediated injury, potentially slowing the progression toward cholestasis and fibrosis.

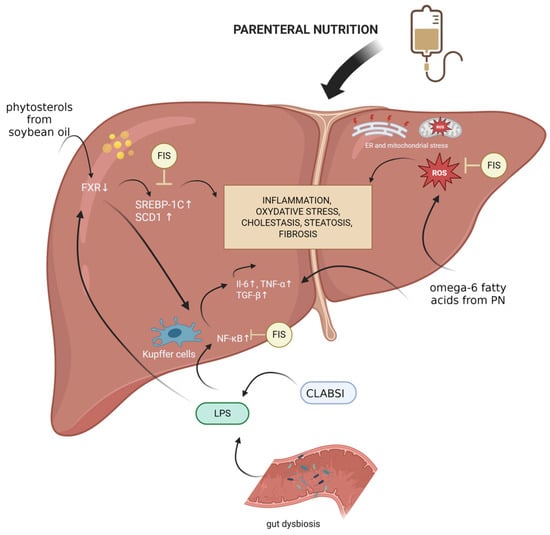

Dysregulated bile acid metabolism, a hallmark of IFALD, results partly from phytosterol-mediated suppression of FXR signaling. While fisetin does not directly activate FXR [56], it modulates downstream metabolic pathways, such as AMPK activation and SREBP inhibition, thereby supporting bile acid and lipid homeostasis. This indirect modulation may offer therapeutic benefits in cases where FXR signaling is impaired (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms underlying IFALD development and fisetin’s potential protective effects. Created with BioRender.com. Abbreviations: CLABSI, central line-associated bloodstream infection; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FIS, fisetin; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; IL-6, interleukin-6; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PN, parenteral nutrition; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SCD1, stearyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1; SREBP-1C, Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1c; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor.

Moreover, fisetin’s influence on the gut–liver axis is of growing interest. By promoting the growth of beneficial microbial species and enhancing gut barrier integrity, fisetin may reduce endotoxin translocation and Kupffer cell activation—important contributors to systemic and hepatic inflammation during TPN. Additionally, by just removing an excess of senescent cells from either the gut or the liver tissue, Fisetin can promote a favorable environment for improved gut biosis and a healthier liver due to suppressed SASP secretion within these two organs.

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a natural hydrophilic bile acid, has been investigated for conditions such as cholestatic liver disease and IFALD. While UDCA has shown some beneficial effects in IFALD, robust evidence supporting its efficacy in this setting is still limited. Its primary actions involve reducing the toxicity of the bile acid pool and exerting cytoprotective effects, partly through inhibition of apoptosis [57,58]. In comparison, fisetin appears to have a more favorable safety profile and a broader spectrum of pleiotropic activities, including pronounced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, which makes it a particularly attractive candidate for further investigation relative to UDCA. Compared with existing therapeutic approaches such as UDCA or fish oil-based lipid emulsions, fisetin offers a wider mechanistic profile, combining anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, metabolic, anti-fibrotic, and senolytic effects that may provide complementary or enhanced benefits in the multifactorial context of IFALD.

These pleiotropic actions suggest that fisetin may complement or even surpass existing therapies, particularly given the multifactorial pathogenesis of IFALD.

Fisetin’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and metabolic regulatory actions collectively address key pathogenic drivers of IFALD, highlighting its potential as a multi-target therapeutic agent in this challenging clinical setting.

7. Consideration of Supplying Fisetin to Patients Fed Parenterally

Many studies on fisetin have primarily focused on its oral administration. Compared to oral administration, fisetin exhibits different behavior when administered intravenously. Following an intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg in rats, fisetin is rapidly biotransformed in the liver into fisetin sulfates through conjugation. In contrast, following oral administration at a dose of 50 mg/kg, a portion of fisetin remains unmetabolized in the systemic circulation. This suggests that fisetin undergoes less sulfation in the intestinal enterocytes than in hepatocytes, with glucuronidation being the dominant pathway after oral intake [27].

In cancer studies involving mice, intravenous administration of a fisetin nanoemulsion showed relatively higher toxicity. However, compared to intraperitoneal administration of free fisetin, the nanoemulsion significantly increased plasma concentrations of the compound, indicating improved bioavailability through this method [59].

According to data retrieved from the ClinicalTrials.gov registry, current clinical trials involving fisetin include 20 interventional studies focused primarily on its senolytic, anti-inflammatory, and functional health-supporting properties. Most trials investigate healthy aging, frailty, and multimorbidity in older adults, assessing whether fisetin can reduce the burden of senescent cells, improve mobility, decrease inflammation, and enhance overall physical function (e.g., NCT07195318, NCT06431932, NCT03675724). Additional studies explore its use in vascular conditions such as peripheral arterial disease and endothelial dysfunction, as well as in rehabilitation following cancer treatment, particularly among breast cancer survivors, where fisetin is evaluated for its potential to reduce fatigue and support functional recovery. Fisetin is also being investigated in orthopedic conditions, including carpal tunnel syndrome and knee osteoarthritis, as well as in several COVID-19 studies examining its ability to mitigate inflammatory complications in older adults. Overall, current clinical trials on fisetin focus predominantly on aging-related conditions, inflammation, rehabilitation, and vascular or orthopedic disorders. Importantly, no clinical trials have yet examined its effects on liver diseases, indicating a clear gap in the existing evidence base and suggesting a promising direction for future research.

Although most available studies investigating fisetin have been conducted in animal or in vitro models, emerging human data provide additional insights into its pharmacological behavior. Clinical studies evaluating fisetin in the context of aging, inflammatory conditions, viral infections, and cancer suggest that the compound is generally well-tolerated; however, its low oral bioavailability remains a significant challenge. Fisetin undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism, resulting in rapid glucuronidation and sulfation. For this reason, recent research has focused on alternative routes of administration and advanced delivery systems. Nanoemulsions, solid lipid nanoparticles, liposomal encapsulation, and cyclodextrin complexes have all been shown to improve solubility, stability, and systemic exposure. These technologies may be particularly relevant for potential therapeutic applications in IFALD, where enhanced bioavailability and controlled delivery are essential. Future studies should compare these formulations directly in both preclinical and clinical settings to identify the most effective strategy for fisetin delivery.

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The available evidence highlights fisetin as a promising natural compound with broad hepatoprotective activity. Its multifaceted effects—including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-fibrotic, lipid-regulating, and microbiota-modulating actions—have been demonstrated across diverse models of liver injury. These mechanisms are highly relevant to the complex and multifactorial pathogenesis of intestinal failure-associated liver disease (IFALD), a serious complication of prolonged parenteral nutrition. Fisetin modulates key molecular pathways such as NF-κB, Nrf2, AMPK, and SIRT1, thereby counteracting oxidative stress, suppressing pro-inflammatory mediators, improving lipid and bile acid homeostasis, and attenuating fibrotic remodeling. Moreover, its influence on gut microbiota composition may provide an additional benefit by supporting gut–liver axis homeostasis.

This review synthesizes current knowledge on fisetin’s molecular actions and contextualizes these mechanisms within IFALD pathophysiology, offering a comprehensive mechanistic and translational perspective. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The available evidence is predominantly preclinical and derives from heterogeneous experimental models with substantial variability in dosing regimens, endpoints, and study design; importantly, no clinical trials have evaluated fisetin specifically in IFALD to date. In addition, as a narrative review, this work does not include a quantitative synthesis or a formal risk-of-bias assessment.

Despite these constraints, fisetin remains a biologically active and generally safe compound whose clinical utility is currently limited mainly by poor water solubility and low systemic bioavailability. Recent advances in drug delivery systems—including nanoformulations and liposomal encapsulation—may help overcome these barriers and facilitate more effective (including parenteral) administration. Future work should prioritize standardized experimental approaches, clinically relevant in vivo models that better reflect the clinical course of IFALD, and early-phase clinical studies to validate fisetin’s efficacy, safety, and optimal delivery strategies. Overall, fisetin warrants further investigation as a potential therapeutic agent for preventing and treating IFALD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., M.S. and V.K.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., M.S., M.M.M. and V.K.-K.; writing—review and editing, M.B., M.S., M.M.M. and V.K.-K.; supervision, M.S. and V.K.-K.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out as part of the OPUS project no. 2022/45/B/NZ7/01056 funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, under a research grant awarded to Maciej Stawny.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CXCL-2 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| GPX1 | glutathione peroxidase 1 |

| GSase | galactosylceramide sulfotransferase |

| GSH | glutathione |

| GSR | glutathione reductase |

| Gstm1 | glutathione S-transferase Mu 1 |

| Gstp1 | glutathione S-transferase Pi 1 |

| HO-1 | heme-oxygenase 1 |

| HSF1 | heat shock factor protein 1 |

| FAS | fatty acid synthase |

| FGFR4 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 |

| FGFR19 | fibroblast growth factor 19 |

| FXR | farnesoid X receptor |

| IFALD | Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-18 | interleukin-18 |

| LPL | lipoprotein lipase |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MMP-2 | matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP-9 | matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H Quinone oxidoreductase 1 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| p53 | tumor protein p53 |

| PAI-1 | plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PN | parenteral nutrition |

| PPARα | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alfa |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SASP | senescent associated secretory phenotypes |

| SCD1 | stearyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2 |

| SREBP-1c | sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alfa |

| TPN | total parenteral nutrition |

References

- Mehta, P.; Pawar, A.; Mahadik, K.; Bothiraja, C. Emerging Novel Drug Delivery Strategies for Bioactive Flavonol Fisetin in Biomedicine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.W.; Bhatwadekar, A.D. Senolytics in the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 896907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsallabi, O.; Patruno, A.; Pesce, M.; Cataldi, A.; Carradori, S.; Gallorini, M. Fisetin as a Senotherapeutic Agent: Biopharmaceutical Properties and Crosstalk between Cell Senescence and Neuroprotection. Molecules 2022, 27, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavenier, J.; Nehlin, J.O.; Houlind, M.B.; Rasmussen, L.J.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; Andersen, O.; Rasmussen, L.J.H. Fisetin as a Senotherapeutic Agent: Evidence and Perspectives for Age-Related Diseases. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2024, 222, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koneru, M.; Sahu, B.D.; Kumar, J.M.; Kuncha, M.; Kadari, A.; Kilari, E.K.; Sistla, R. Fisetin Protects Liver from Binge Alcohol-Induced Toxicity by Mechanisms Including Inhibition of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Oxidative Stress. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 22, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, W.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Dietary Fisetin Supplementation Protects Against Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, W.; Feng, X.; Yang, F.; Qin, H.; Wu, S.; Hou, D.-X.; Chen, J. Nrf2–ARE Signaling Acts as Master Pathway for the Cellular Antioxidant Activity of Fisetin. Molecules 2019, 24, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Syed, D.N.; Ahmad, N.; Mukhtar, H. Fisetin: A Dietary Antioxidant for Health Promotion. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molagoda, I.M.N.; Athapaththu, A.M.G.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Park, C.; Jin, C.-Y.; Kang, C.-H.; Lee, M.-H.; Kim, G.-Y. Fisetin Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome by Suppressing TLR4/MD2-Mediated Mitochondrial ROS Production. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.U.; Samanta, S.; Dash, R.; Karpiński, T.M.; Habibi, E.; Sadiq, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Bungau, S. The Neuroprotective Effects of Fisetin, a Natural Flavonoid in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on the Role of Oxidative Stress. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1015835, Erratum in Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1095648. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1095648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-S.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kwon, E.-Y. Fisetin Alleviates Hepatic and Adipocyte Fibrosis and Insulin Resistance in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Ge, C.; Qin, Y.; Gu, T.; Lv, J.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Lou, D.; Li, Q.; Hu, L.; et al. Activated TNF-α/RIPK3 Signaling Is Involved in Prolonged High Fat Diet-Stimulated Hepatic Inflammation and Lipid Accumulation: Inhibition by Dietary Fisetin Intervention. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minxuan, X.; Sun, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhan, J.; Long, T.; Xiong, M.; Li, H.; Kuang, Q.; Tang, T.; Qin, Y.; et al. Fisetin Attenuates High Fat Diet-Triggered Hepatic Lipid Accumulation: A Mechanism Involving Liver Inflammation Overload Associated TACE/TNF-α Pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 53, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaballah, H.H.; El-Horany, H.E.; Helal, D.S. Mitigative Effects of the Bioactive Flavonol Fisetin on High-fat/High-sucrose Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 12762–12774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayali, A.; Bora, E.; Acar, H.; Yilmaz, G.; Erbaş, O. Fisetin Ameliorates Methotrexate Induced Liver Fibrosis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 28, 3112–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fadaly, A.A.; Afifi, N.A.; El-Eraky, W.; Salama, A.; Abdelhameed, M.F.; El-Rahman, S.S.A.; Ramadan, A. Fisetin Alleviates Thioacetamide-Induced Hepatic Fibrosis in Rats by Inhibiting Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C.; Wang, T.; Lu, J.; Wu, C.; Chen, L.; Jin, M.; Hu, H.; Ji, G.; et al. Fisetin Prevents Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury by Promoting Autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żalikowska-Gardocka, M.; Niewada, M.; Niewiński, G.; Iżycka, M.; Ratyńska, A.; Żurek, M.; Nawrot, A.; Przybyłkowski, A. Early Predictors of Liver Injury in Patients on Parenteral Nutrition. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 51, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Teckman, J. Controversies in the Mechanism of Total Parenteral Nutrition Induced Pathology. Children 2015, 2, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Maeng, S.A.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, Y.S.; Yoo, J.-J. Parenteral Nutrition-Induced Liver Function Complications: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Prognosis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaloga, G.P. Phytosterols, Lipid Administration, and Liver Disease During Parenteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr 2015, 39, 39S–60S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Guthrie, G.; Stoll, B.; Chacko, S.; Lin, S.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Dawson, H.; Pastor, J.J.; et al. Selective Agonism of Liver and Gut FXR Prevents Cholestasis and Intestinal Atrophy in Parenterally Fed Neonatal Pigs. J. Lipid Res. 2025, 66, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak, J.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Fisetin—In Search of Better Bioavailability—From Macro to Nano Modifications: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antika, L.D.; Dewi, R.M. Pharmacological Aspects of Fisetin. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jash, S.K.; Mondal, S. Bioactive Flavonoid Fisetin—A Molecule of Pharmacological Interest. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 2, 89–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, Y.; Nie, S.; Zhou, S.; Gao, X.; Chen, G. Biological Effects and Mechanisms of Fisetin in Cancer: A Promising Anti-Cancer Agent. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, C.-S.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Kuo, S.-C.; Hou, Y.-C.; Chao, P.-D.L. Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics of 3,3′,4′,7-Tetrahydroxyflavone (Fisetin), 5-Hydroxyflavone, and 7-Hydroxyflavone and Antihemolysis Effects of Fisetin and Its Serum Metabolites. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, C.-J.; Wei, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Wang, C.-L.; Huang, W.-C. Fisetin Protects Against Hepatic Steatosis Through Regulation of the Sirt1/AMPK and Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Signaling Pathway in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambright, W.S.; Duke, V.R.; Goff, A.D.; Goff, A.W.; Minas, L.T.; Kloser, H.; Gao, X.; Huard, C.; Guo, P.; Lu, A.; et al. Clinical Validation of C12FDG as a Marker Associated with Senescence and Osteoarthritic Phenotypes. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, E.N.; Soysal, Y. Molecular and Therapeutic Effects of Fisetin Flavonoid in Diseases. J. Basic Clin. Health Sci. 2020, 4, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugan, R.A.; Cadirci, E.; Un, H.; Cinar, I.; Gurbuz, M.A. Fisetin Attenuates Paracetamol-Induced Hepatotoxicity by Regulating CYP2E1 Enzyme. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2023, 95, e20201408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Pan, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; You, L.; Jia, Y.; Hu, C. Protective Effect of 7,3′,4′-Flavon-3-Ol (Fisetin) on Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity In Vitro and In Vivo. Phytomedicine 2019, 58, 152865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaer, D.F.E.; Halim, H.I.A.E. The Possible Ameliorating Role of Fisetin on Hepatic Changes Induced by Fluoxetine in Adult Male Albino Rats: Histological, Immunohistochemical, and Biochemical Study. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2023, 11, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umar, M.; Muzammil, S.; Zahoor, M.A.; Mustafa, S.; Ashraf, A.; Hayat, S.; Ijaz, M.U. Fisetin Attenuates Arsenic-Induced Hepatic Damage by Improving Biochemical, Inflammatory, Apoptotic, and Histological Profile: In Vivo and In Silico Approach. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1005255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez-Reyes, S.; Bernal-Gámez, M.; Domínguez-Chávez, J.; Mondragón-Vásquez, K.; Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Ordaz, G.; Granados-Portillo, O.; Coutiño-Hernández, D.; Barrera-Gómez, P.; Torres, N.; et al. The Effects of Novel Co-Amorphous Naringenin and Fisetin Compounds on a Diet-Induced Obesity Murine Model. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Kuang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhu, L.; Ge, C.; Tan, J.; Wang, B. Fisetin Represses Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in NAFLD through Suppressing GRP78-Mediated Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 90, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, W.; Qian, F. Fisetin Alleviates Sepsis-Induced Multiple Organ Dysfunction in Mice via Inhibiting P38 MAPK/MK2 Signaling. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsuraih, M.; O’Hara, S.P.; Woodrum, J.E.; Pirius, N.E.; LaRusso, N.F. Genetic or Pharmacological Reduction of Cholangiocyte Senescence Improves Inflammation and Fibrosis in the Mdr2 Mouse. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Sun, L.; Pan, J.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, C.; Zeng, F.; Tian, M.; Wu, S. A Targeted Nanosystem for Detection of Inflammatory Diseases via Fluorescent/Optoacoustic Imaging and Therapy via Modulating Nrf2/NF-κB Pathways. Small 2021, 17, 2102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Ge, C.; Qin, Y.; Gu, T.; Lou, D.; Li, Q.; Hu, L.; Tan, J. Multicombination Approach Suppresses Listeria Monocytogenes-Induced Septicemia-Associated Acute Hepatic Failure: The Role of iRhom2 Signaling. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1800427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huard, C.A.; Gao, X.; Dey Hazra, M.E.; Dey Hazra, R.-O.; Lebsock, K.; Easley, J.T.; Millett, P.J.; Huard, J. Effects of Fisetin Treatment on Cellular Senescence of Various Tissues and Organs of Old Sheep. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.-L.; Huang, Z.-T.; Luo, Y.-H.; Mou, T.; Li, T.-T.; Li, Z.-T.; Wei, X.-F.; Wu, Z.-J. Fisetin Mitigates Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Regulating GSK3β/AMPK/NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathway. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2021, 20, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gao, B.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, J. Protective Effects of Fisetin on Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Through Alleviation of Apoptosis and Oxidative Stress. Arch. Med. Res. 2021, 52, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y.Y.; Melos, K.I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Fisetin Is a Senotherapeutic That Extends Health and Lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abi-Aad, S.-J.; Lovell, M.; Khalaf, R.T.; Sokol, R.J. Pathogenesis and Management of Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 2025, 45, 066–080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kasmi, K.C.; Anderson, A.L.; Devereaux, M.W.; Fillon, S.A.; Harris, K.J.; Lovell, M.A.; Finegold, M.J.; Sokol, R.J. Toll-like Receptor 4–Dependent Kupffer Cell Activation and Liver Injury in a Novel Mouse Model of Parenteral Nutrition and Intestinal Injury. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.W.; Kwon, M.-J.; Choi, A.M.K.; Kim, H.-P.; Nakahira, K.; Hwang, D.H. Fatty Acids Modulate Toll-like Receptor 4 Activation through Regulation of Receptor Dimerization and Recruitment into Lipid Rafts in a Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 27384–27392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci-Da Silva, C.; Zhan, L.; Shen, J.; Kong, B.; Campbell, M.J.; Memon, N.; Hegyi, T.; Lu, L.; Guo, G.L. Effects of Total Parenteral Nutrition on Drug Metabolism Gene Expression in Mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungala Lengo, A.; Mohamed, I.; Lavoie, J.-C. Glutathione Supplementation Prevents Neonatal Parenteral Nutrition-Induced Short- and Long-Term Epigenetic and Transcriptional Disruptions of Hepatic H2O2 Metabolism in Guinea Pigs. Nutrients 2024, 16, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Yang, I.; Kong, B.; Shen, J.; Gorczyca, L.; Memon, N.; Buckley, B.T.; Guo, G.L. Dysregulation of Bile Acid Homeostasis in Parenteral Nutrition Mouse Model. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 310, G93–G102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Shigenaga, J.; Moser, A.; Feingold, K.; Grunfeld, C. Repression of Farnesoid X Receptor during the Acute Phase Response. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 8988–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-D.; Chen, W.-D.; Wang, M.; Yu, D.; Forman, B.M.; Huang, W. Farnesoid X Receptor Antagonizes Nuclear Factor κB in Hepatic Inflammatory Response. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1632–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor-Clerigues, A.; Marti-Bonmati, E.; Milara, J.; Almudever, P.; Cortijo, J. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fibrotic Profile of Fish Oil Emulsions Used in Parenteral Nutrition-Associated Liver Disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafirovska, M.; Zafirovski, A.; Rotovnik Kozjek, N. Current Insights Regarding Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease (IFALD): A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secor, J.D.; Yu, L.; Tsikis, S.; Fligor, S.; Puder, M.; Gura, K.M. Current Strategies for Managing Intestinal Failure-Associated Liver Disease. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 20, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, P.; Sun, H.; Cui, S.; Ao, L.; Cui, M.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. Dual-Function Natural Products: Farnesoid X Receptor Agonist/Inflammation Inhibitor for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Therapy. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 22, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Chang, L.-W.; Wang, J.; Xie, M.; Chen, L.-L.; Liu, W. Ursodeoxycholic Acid Prevention on Cholestasis Associated with Total Parenteral Nutrition in Preterm Infants: A Randomized Trial. World J. Pediatr. 2022, 18, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotb, M.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Ursodeoxycholic Acid Toxicity & Side Effects: Ursodeoxycholic Acid Freezes Regeneration & Induces Hibernation Mode. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8882–8914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelle, H.; Crauste-Manciet, S.; Seguin, J.; Brossard, D.; Scherman, D.; Arnaud, P.; Chabot, G.G. Nanoemulsion Formulation of Fisetin Improves Bioavailability and Antitumour Activity in Mice. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 427, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.