Abstract

High-fat diets are known to contribute to metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, partly through alterations in gut microbiota composition. However, the impact of dietary fat on gut microbiota depends on fat composition, with both the degree of saturation and chain length of fatty acids playing essential roles in modulating microbial populations. Saturated long-chain fatty acids have been shown to promote the production of trimethylamine (TMA), a precursor of trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), an emerging gut microbiota-derived biomarker associated with cardiovascular disease. These effects occur through multiple mechanisms, including increased colonic oxygen levels and taurine-conjugated bile acids, which promote pathways that favor TMA-producing bacteria. In contrast, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids exert beneficial effects by altering pH and supporting SCFA-producing bacteria, thereby reducing levels of TMA-producing bacteria. Given the influence of gut microbial communities and their metabolites on the onset of metabolic disorders, dietary strategies that modulate the microbiota and its metabolic products through optimized fatty acid composition represent promising therapeutic approaches for preventing conditions such as cardiovascular disease.

1. Introduction

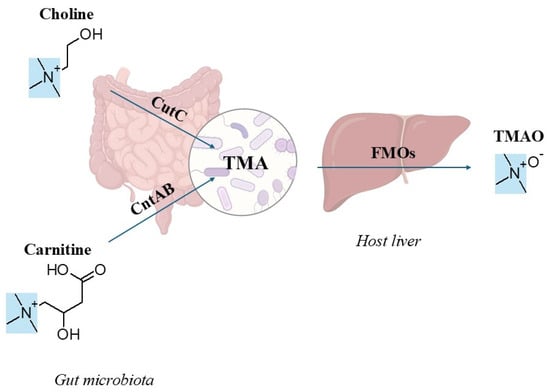

Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), gut microbiota-derived metabolite, is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and may serve as a biomarker for heart failure [1]. However, the underlying mechanisms remain complex and poorly understood [2], partly because circulating TMAO levels are influenced by diet, the gut microbiome composition, and host metabolism. Studies in humans, animals, and cell models demonstrate that elevated plasma TMAO levels adversely affects multiple organs, particularly the heart, liver, and kidneys [2,3,4,5,6,7]. As the kidneys primarily eliminate TMAO from the body, impaired renal function may both intensify its harmful effects [8], and elevate TMAO levels, complicating causal interpretations [2]. TMAO production is a metaorganismal process in which gut bacteria convert dietary precursors into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized to TMAO in the host liver, facilitated by flavin monooxygenase (FMO) enzymes (Figure 1) [9,10,11]. Choline and carnitine are the major dietary precursors for gut microbiota-dependent synthesis of TMAO [12]. Phosphatidylcholine, the primary dietary source of choline, is plentiful in foods of both plant and animal origin, while carnitine is mainly present in red meat [4,12]. It is well established that gut microbiota is essential for converting these metabolites into TMA, as gnotobiotic mice (which lack microbiota) do not produce TMA. Additionally, treating conventional mice with antibiotics significantly reduced TMA formation. When gnotobiotic mice are colonized with choline-metabolizing bacteria, cecal TMA production increases [13]. These TMA-producing bacteria harbor genes encoding enzymes essential for TMA synthesis, including choline-TMA lyase (CutC), carnitine monooxygenase (CntAB), glycine betaine reductase (GrdH), and TMAO reductases (collectively TorA) [14,15,16,17]. Recently, the YeaW/X enzyme complex (dioxygenase and oxidoreductase) was proposed as a third major pathway that directly converts γ-butyrobetaine (γBB) to TMA [18].

Figure 1.

Trimethylamine (TMA), a tertiary amine (highlighted in blue), is a common structural component of nearly all trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) precursors. Excess dietary precursors, primarily choline and carnitine, are metabolized into TMA by gut microbial enzymes (CutC: choline-TMA lyase; CntAB: carnitine monooxygenase). TMA undergoes oxidation in the host liver by flavin monooxygenases (FMOs) to form TMAO. (The chemical structures were drawn with ChemSketch, Version 14.01; Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc. (ACD/Labs): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012.).

Gene clusters involved in TMA production within the gut microbiota are generally found in both obligate anaerobes from the Clostridia class (Firmicutes) and facultative anaerobes from the Enterobacteriaceae family (Proteobacteria) [17,19]. In vitro studies using bacterial isolates from the human intestinal tract revealed that certain strains produced TMA only when choline was provided, as demonstrated by stable isotope tracer experiments [20]. In contrast, carnitine did not serve as a TMA precursor under the same experimental conditions. Carnitine conversion to TMA requires oxygen-dependent enzymes, which were initially discovered in Acinetobacter species and later identified in other gut bacteria. However, given the anaerobic nature of the intestinal environment, the activity of these enzymes is likely constrained [21]. Alternatively, a plausible anaerobic pathway for TMA production from carnitine has been proposed. In this pathway, carnitine is first converted to γBB, which is then converted to TMA. This multistep process appears to require cooperation among different gut commensals, with the obligate anaerobe Emergencia timonensis identified as a key bacterium capable of converting γBB into TMA. Thus, E. timonensis may play a crucial role in TMA production following carnitine consumption in humans [22].

The predominantly anaerobic gut environment favors anaerobic TMA-producing pathways, particularly those mediated by TorA, CutC, and GrdH. Among these, TorA was the most frequently observed, suggesting an active cycle between TMAO and TMA in the gut environment. However, since dietary TMAO primarily originates from marine fish, choline remains the main dietary precursor of TMA. Therefore, the CutC pathway is the primary route of TMA production in the gut. GrdH-like pathways are limited because the energy-demanding synthesis of glycine betaine makes its breakdown metabolically unfavorable in the gut [15].

Although anaerobic choline metabolism is known to play a significant role in CVD, the identity of the key gut microbes involved remained uncertain until the recent discovery of a gene cluster in Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Desulfovibrio alaskensis that mediates this pathway [23]. This finding aligns with earlier work showing that CutC was first identified in the anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacterium D. desulfuricans [24]. Diet further shapes this metabolic axis [25]. Western dietary patterns, characterized by high intake of animal proteins and saturated fats, not only increase circulating and urinary levels of the TMA-derived metabolite TMAO but also shift gut microbial composition [26]. Consistent with this, Manor et al. [27] reported that individuals consuming animal-based diets and those with symptomatic CVD exhibit higher gut abundance of Desulfovibrio, which was positively associated with elevated TMAO levels.

Beyond digestion and barrier protection, the gut also functions as an endocrine organ. Enteroendocrine cells release hormones in response to luminal and neuronal signals. These cells secrete serotonin (5-HT), which influences motility, secretion, and central nervous system function. They also secrete glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which regulate insulin secretion, satiety, and motility. Together, these gut-derived hormones coordinate digestion, appetite, and systemic metabolism, highlighting the important role of the gut microbiota in human physiology [28]. Dietary components that are not readily absorbed in the small intestine serve as substrates for the gut microbiota [29], which directly influences its composition and metabolic processes, potentially affecting TMAO metabolism [30]. Therefore, diet is a significant determinant of the structure, diversity, and functional activity of gut microbiota [31,32,33]. Previous studies have shown that a diet high in saturated fat increases the risk of metabolic disorders, including obesity and heart disease, through the microbiota [34,35,36]. The general trend in the literature suggests that diets high in saturated fatty acids are commonly associated with a characteristic high-fat diet (HFD) profile, marked by obesity. In contrast diets abundant in polyunsaturated fatty acids tend to exert beneficial effects [37]. To explore this topic further, this review specifically examined how various dietary fat types influence gut microbiota-derived TMAO.

2. Association of Dietary Habits with the Human Gut Microbiota

The relationship between the gut microbiota and diet is established early in life and persists throughout life. Early-life nutrition, especially breastfeeding, plays a crucial role in gut microbiota development [38]. Breastfeeding strongly correlates with increased Bifidobacterium abundance [39,40,41], a key component of healthy infant microbiota, along with Lactobacillus species [42]. Breast milk contains oligosaccharides, including lactose and more than 1000 distinct non-digestible molecules that serve as ideal substrates for bacterial fermentation. Preterm infants typically show altered microbial profiles dominated by Proteobacteria, but breast milk feeding specifically increases Bifidobacterium populations, indicating how the non-digestible sugars in breast milk selectively promote beneficial bacterial species. As infants transition to solid foods, their microbiota adapts to broader range of energy substrates, enhancing carbon metabolism capacity [43]. Because multiple factors, such as nutrition, surroundings, time of year, and personal well-being, influence it, defining a standard or typical microbiota profile for the general population is practically impossible [38]. Despite this variability, human microbiota can be categorized into three distinct enterotypes based on predominant genera: Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Ruminococcus [31], with Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes representing the most abundant phyla in human fecal samples [44]. These enterotypes are shaped mainly by long-term dietary patterns. Diets high in protein and animal faty are associated with increased levels of Bacteroides, whereas carbohydrate-focused diets are associated with increased levels of Prevotella. Interestingly, these enterotypes appear to be independent of external elements such as age, sex, body mass index, or place of residence and are primarily influenced by diet and genetics [45].

Recent studies suggest that enterotypes may lie on a spectrum rather than being distinct categories, but they remain useful tool for exploring overall microbiota diversity [46]. When participants were grouped into previously identified enterotypes based on their fecal microbial profiles, those with an enterotype dominated by the genus Prevotella (n = 4) exhibited significantly higher plasma TMAO levels than those with an enterotype marked by a higher abundance of the genus Bacteroides (n = 49) [3]. Although this finding supports a potential connection between enterotypes and microbial TMA generation, caution is warranted when interpreting or generalizing the results. Notably, only four samples in the study belonged to the Prevotella group, and the Ruminococcus enterotype was entirely absent [3].

3. High-Fat Diets Modify Gut Microbiota and Influence TMAO Production

HFDs alter the gut microbiota composition, notably increasing the proportion of Firmicutes relative to Bacteroidetes [47,48]. While this elevated ratio is often considered a marker of obesity in animals and humans, obese individuals generally show lower bacterial diversity compared to lean counterparts. This suggests that compositional changes at the family, genus, or species level may have a greater impact than the phylum-level ratio alone [49]. Thus, relying solely on the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio may oversimplify the complex relationship among microbial diversity, composition, and health outcomes. Instead of a single universally healthy microbiota state, multiple beneficial microbiota profiles may exist, each characterized by distinct microbial communities. For example, the relationship between Bacteroidetes abundance and microbiota diversity is non-linear in humans [50]. Beyond taxonomic shifts, microbiota composition is closely linked to host clinical markers and lifestyle factors, with specific host-microbe interactions playing a pivotal role. Gut microbiota contributes to various diet-induced metabolic disorders, including cardiovascular disease [1,11], obesity [51,52], insulin resistance [52,53], and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [54,55,56]. HFDs increase cardiovascular disease risk partly through gut microbial production of TMA [19]. While gene clusters involved in choline metabolism are widespread among the gut microbiota [23], only facultative anaerobes tend to proliferate in individuals consuming HFDs [19]. By comparing the effects of high-fat and low-fat diets, researchers found that dietary choline (1%) provided Escherichia coli a CutC-dependent growth benefit in mice fed HFDs, whereas this effect was absent in mice fed a low-fat diet. This suggests that E. coli strains carrying the cut operon metabolize choline under conditions induced by HFD-mediated alterations in the intestinal environment [19]. In contrast to high-fat Western diets, the Mediterranean dietary pattern demonstrates multiple protective mechanisms against TMAO-exacerbated atherosclerosis and gut barrier dysfunction [57,58]. The Mediterranean diet is characterized by two key components that synergistically promote cardiovascular and gut health: n-3-rich fatty acids from regular fish consumption and abundant dietary fiber from plant-based foods, including vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, and nuts. These fibers elevate fecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations as gut bacteria ferment host-indigestible carbohydrates. The resulting short-chain fatty acids strengthen the intestinal barrier and reduce systemic inflammation [57,59].

4. Do All Fatty Acids Have the Same Impact?

Fatty acids (FAs) serve as crucial energy sources, undergoing mitochondrial β-oxidation and catabolism through the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Beyond energy production, FAs are vital components of cell membrane phospholipids. The specific FA composition of cell membranes varies across cell types, membrane structures, and phospholipid classes, influenced by diet, metabolism, hormonal conditions, cell activation states, and genetics. This composition affects the physical properties of membranes, including fluidity and structural order, which in turn regulate the function and mobility of proteins within the membrane [60].

FAs exhibit significant diversity in their carbon chain lengths and degree of saturation [61]. By chain length, FAs are classified as short-chain (2−4 carbons), medium-chain (6−12 carbons), and long-chain (>12 carbons) fatty acids (SCFAs, MCFAs, and LCFAs, respectively) [62]. LCFAs, particularly C16 and C18, are the most abundant in mammalian cells. By saturation, FAs are classified as saturated (SFAs, no double bonds), monounsaturated (MUFAs, one double bond), or polyunsaturated (PUFAs, multiple double bonds). PUFAs are further divided into omega-3 (n-3) and omega-6 (n-6) families based on the position of the final double bond relative to the carboxyl end [61]. SCFAs (C4–C6) and MCFAs (C8–C12) can freely diffuse across the mitochondrial membranes, allowing direct accessing to the mitochondrial matrix. In contrast, LCFAs (C14–C20) cannot cross mitochondrial membranes unaided and require a carnitine-dependent transport system [63]. The transport of LCFAs into mitochondria involves a shuttle mechanism known as the carnitine cycle, which relies on three key enzymes: carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT1), carnitine acylcarnitine translocase (CACT), and carnitine palmitoyltransferase II (CPT2). Although these enzymes are located in different regions of the mitochondria, all three enzymes require carnitine as a cofactor [63,64].

FA composition varies by dietary source [65]. Animal-derived fats are typically high in SFAs [66], while marine sources like fish oils are rich in n-3 PUFAs [67]. Vegetable oils display diverse FA profiles depending on plant species: olive oil is abundant in MUFAs, whereas sunflower and flaxseed oils are rich in PUFAs [68]. Palm oil contains 40–50% saturated fat, predominantly palmitic acid (16:0), making it significantly more saturated than olive or sunflower oils [69]. MCFAs comprise over 50% of the lipid content in coconut and palm kernel oils, but only 14–15% in cow milk, where levels vary with breed, pasture type, and season [70]. This diversity in FA composition reflects the unique characteristics and potential health impacts of each dietary source [68].

Common sources of dietary fats in HFDs, including plant oils (corn, peanut, soybean, sunflower) and animal fats (lard), generally increase Firmicutes and decrease Bacteroidetes, though their impact on gut microbiota alpha diversity varies. This variation may significantly influence health outcomes, as specific FA types can independently alter microbial composition [71]. Factors such as saturation level and carbon chain length appear to play key roles in shaping microbial communities [72]. Diets high in saturated FAs have been linked to reduced microbial diversity and richness, as well as decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes [73]. Mice fed lard-based HFD exhibit Firmicutes and reduced Bacteroidetes [73,74], a pattern also observed with palm oil-based HFDs [75]. In contrast, diets high in unsaturated FAs, such as fish oil, promote greater microbial diversity and richness while increasing Bacteroidetes [75]. Liu et al., (2012) [76] showed that SFAs more strongly altered gut microbiota profiles than n-3 or n-6 PUFAs, notably causing a significant Bacteroidetes reduction characteristic of obesity.

Although the exact mechanisms are not fully understood, n-3 FAs appear to support gut health by increasing lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-suppressing bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus while reducing inflammatory LPS-producing Enterobacteria [77,78,79]. Similarly, diets rich in MUFAs, such as those containing olive oil, are known to beneficially modify gut microbiota composition by expanding commensal bacterial populations [77,80]. Medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) also protect against LPS-induced endotoxemia. Rats fed MCTs daily for one week survived subsequent intravenous LPS administration, while corn oil-fed rats did not, highlighting MCTs’ anti-inflammatory benefits [70].

The effect of dietary FAs on TMAO has been demonstrated in multiple studies [9,12,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91], as summarized in Table 1. In animal studies, SFAs from palm oil (rich in palmitic acid, 16:0), lard (high in oleic acid, 18:1n-9, and palmitic acid, 16:0), butter, and egg yolk-derived phosphatidylcholine promote TMA-producing bacteria such as E. coli and Desulfovibrio [19,24,82,92,93]. MUFAs are generally associated with reduced TMAO levels [80,88], though this may reflect bioactive compounds in oil rather than the fatty acids themselves [81,94]. Andújar-Tenorio et al. (2022) [80] compared the effects of different HFDs in mice fed standard chow, butter-enriched chow (representing saturated fats), or extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO)-enriched chow (representing unsaturated fats). After 12 weeks, butter-fed mice exhibited higher Desulfovibrio abundance than EVOO-fed mice. EVOO’s protective effects may be partly attributed to its 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB) content, a choline analog that inhibits microbial TMA lyases without bactericidal activity. In polymicrobial systems including intestinal contents and human feces, DMB reduces TMA production and lowers TMAO concentrations in mice consuming high-choline or carnitine diets [81].

n-3 PUFAs from fish oil, linseed oil, and Symplectoteuthis oualaniensis-derived phosphatidylcholine lower TMAO levels, increase SCFA-producing bacteria, and reduce Desulfovibrionaceae in animal studies [84,88,95]. However, n-3 PUFAs from krill oil, n-3-enriched eggs, and Mediterranean diet interventions showed neutral effects on TMAO in human clinical trials [85,86,96]. This animal–human discrepancy likely reflects greater variability in human baseline gut microbiota composition, genetic factors, and lifestyle habits that may mask FA-specific effects, whereas animal studies provide more controlled conditions [97,98]. n-6 PUFAs from sunflower oil and soybean phosphatidylcholine either increased TMAO or showed neutral effects in animal studies [89]. Transgenic mice expressing FAT-2 (converting MUFAs to n-6 PUFAs) exhibited higher choline and TMAO levels with increased Enterobacteriaceae and depleted Bifidobacteriaceae compared to wild-type and FAT-1 mice (converting n-6 to n-3 PUFAs), suggesting that n-6 PUFA effects on TMAO depend on the n-6/n-3 ratio [90]. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, inhibit microbial TMA production by downregulating TMA-lyase genes (CutC, CntA) and reducing TMA-producing bacteria (Escherichia fergusonii and Anaerococcus hydrogenalis) in vivo and in vitro models [9]. Mechanisms by which FAs influence gut microbiota and TMAO formation are outlined in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of dietary fats and oils on TMAO and gut microbiota.

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of dietary fats and oils on TMAO and gut microbiota.

| Fat/Oil/FA Source | Main FA Composition | Model | Main Findings on TMA-Producing Bacteria and TMAO | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palm oil | Palmitic acid (16:0) (SFA) | In vivo (animal) | Increased E. coli abundance, which is associated with higher TMAO production | [19,92] |

| Lard | Oleic acid (18:1n-9) (MUFA), Palmitic acid (16:0) (SFA) | In vivo (animal) | Promoted Desulfovibrio growth, a bacterium linked to elevated TMAO | [24,93] |

| Butter | Palmitic acid (16:0), Stearic acid (18:0) (SFA) | In vivo (animal) | Increased Desulfovibrio abundance compared to EVOO-fed mice | [24,80] |

| Extra-virgin olive oil | Oleic acid (18:1n-9) (MUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Reduced Desulfovibrio abundance; possibly due to DMB-mediated inhibition of microbial TMA lyases, leading to decreased TMA and TMAO production | [24,80] |

| Sodium butyrate supplement | Butyrate (C4:0) (SCFA) | In vitro; In vivo (animal) | Suppressed TMA formation by downregulating TMA-lyase genes (CutC, CntA), reduced E. fergusonii and A. hydrogenalis, lowered TMAO, and alleviated HFD-induced atherosclerosis | [9] |

| Sandalwood seed oil | Oleic acid (18:1n-9) (MUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Reduced plasma TMAO compared to sunflower oil (rich in linoleic acid, an n-6 PUFA) | [88,89] |

| Fish oil | EPA (20:5n-3), DHA (22:6n-3) (n-3 PUFAs) | In vivo (animal) | Lowered TMAO levels, increased SCFA-producing bacteria and Bifidobacterium, reduced Desulfovibrionaceae, and protected against TMAO-aggravated atherosclerosis | [83,88] |

| Linseed oil | α-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3) (n-3 PUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Reduced TMAO levels compared to sunflower oil and promoted SCFA-producing bacteria | [88,89] |

| Sunflower oil | Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (n-6 PUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Increased TMAO levels compared to sandalwood seed oil, fish oil, and linseed oil | [88,89] |

| Phosphatidylcholine from S. oualaniensis | EPA, DHA (n-3 PUFAs) | In vivo (animal) | Prevented HFD-induced increase in serum TMAO | [84] |

| Phosphatidylcholine from soy-bean | Linoleic acid (18:2n-6) (n-6 PUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Showed neutral effects on TMAO compared with HFD control | [84] |

| Phosphatidylcholine from egg yolk | Palmitic acid (16:0), Stearic acid (18:0) (SFA) | In vivo (animal) | Elevated serum TMAO compared with HFD control | [84] |

| Chicken protein hydrolysate (CPH) ± chicken oil | Oleic acid (18:1n-9) (MUFA) | In vivo (animal) | Increased plasma TMAO and total carnitines in both CPH and CPH + chicken oil groups compared to control diet; unclear whether oleic acid alone drives this effect | [87] |

| Krill oil supplement | EPA:DHA (n-3 PUFAs enriched phospholipid) | In vivo (human, clinical) | Improved cardiovascular risk markers (TAGs, lipoproteins, FA profile, redox balance), but did not affect plasma TMAO or carnitine | [85] |

| n-3–enriched eggs | α-Linolenic acid (18:3n-3), EPA, DHA (n-3 PUFAs) | In vivo (human, clinical) | Increased plasma choline and betaine levels, but did not alter TMAO | [86] |

| Mediterranean diet | 1:2:5 ratio of n-3 PUFA:SFA:MUFA | In vivo (human, clinical) | Found no significant changes in plasma TMAO or TMAO-to-precursor ratios in either the Mediterranean diet group or the Healthy Eating comparison group, despite both groups having elevated fasting levels at baseline | [96] |

| High- vs. low-SFA diets with protein variation | SFA; red meat, white meat, non-meat) | In vivo (human, clinical) | Revealed no effect of SFA content on TMAO, but red meat consumption increased TMAO via higher carnitine intake and reduced renal excretion | [12] |

| Western diet (WD) | SFA | In vivo (animal) | Showed a pronounced rise in plasma TMAO in mice fed a Western diet for 8 weeks compared with those on a standard diet | [91] |

Table 2.

Potential mechanisms by which different fatty acids influence gut microbiota and TMAO formation.

Table 2.

Potential mechanisms by which different fatty acids influence gut microbiota and TMAO formation.

| FA Class | FA Type | Potential Mechanism | Impact on TMAO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated | Short-chain FAs | Direct Effects:

| Decrease |

| Long-chain FAs | Direct Effects:

| Increase | |

| Unsaturated | Poly-unsaturated FAs (n-3) | Direct Effects:

| Decrease |

5. Potential Mechanism

While most FAs are absorbed early in the digestive tract, excess amounts reach the colon, where they can alter the composition of the intestinal microbial community [107]. Unlike long-chain FAs (LCFA), short- and medium-chain FAs (SCFA and MCFA) are efficiently absorbed by intestinal epithelial cells through passive diffusion due to their shorter chain length and higher water solubility [70], minimizing colonic accumulation and microbial disruption.

Gut dysbiosis from HFDs occurs primarily through altered oxygen and energy availability [93,103,104]. The colon’s normally hypoxic environment favors beneficial anaerobes while limiting facultative anaerobes such as Enterobacteriaceae [108]. HFDs impair enterocyte mitochondrial function and oxygen consumption, increasing luminal oxygen and nitrate levels [19]. This shift favors facultative anaerobes such as E. coli while suppressing obligate anaerobic bacteria [19], elevating the Gram-negative to Gram-positive bacterial ratio [66]. Enhanced LPS release from Gram-negative bacteria stimulates inflammation, further promoting proinflammatory microbial populations. This dysbiotic profile specifically shows diminished obligate anaerobic Firmicutes and elevated facultative anaerobic Enterobacteriaceae levels [103]. Some commensal bacteria, like E. coli, exploit inflammatory conditions by using nitric oxides as an energy source, gaining a competitive advantage [109]. This Enterobacteriaceae expansion increases bacterial conversion of choline into TMA, the precursor to TMAO [19]. HFDs rich in saturated fat may also facilitate TMAO production by increasing the availability of organic sulfur to sulfate-reducing bacteria, such as Desulfovibrionaceae, including Desulfovibrio [93]. When dietary fat is consumed, the liver synthesizes bile acids [110], producing taurine- or glycine-conjugated bile acids that are released into the duodenum to facilitate lipid absorption in the small intestine. During intestinal transit, most bile acids undergo deconjugation [111,112], releasing taurine and thereby increasing sulfur availability for sulfate-reducing organisms [93,104]. Furthermore, hydrophobic bile acids compromise intestinal barrier integrity, potentially allowing microbial metabolites to enter the bloodstream [112], such as TMA.

Another mechanism by which FAs may alter gut microbiota composition is through their antimicrobial properties [99]. Their potency depends on chain length, degree of saturation, and the position of double bonds [107,113,114]. SFAs are generally more effective at shorter chain lengths, while MUFAs and PUFAs tend to exhibit greater activity at longer chain lengths. SCFAs display pH-dependent antimicrobial activity, disrupting energy metabolism primarily in Gram-negative bacteria [99]. Higher SCFA concentrations reduce pH, favoring Bifidobacteriaceae and Lactobacillaceae over Enterobacteriaceae [99,113]. SCFAs suppress pathogenic bacteria, preventing dysbiosis and inflammation [25,100,101], while reducing nitric oxide production that drives TMA lyase expression [19]. Colonic acidification also limits bile acid solubility, reducing colonocytes toxicity [113]. Notably, SCFA and TMAO production are inversely related, as HFDs elevate TMAO while suppressing SCFA synthesis [115]. MCFAs (particularly lauric acid) and n-3 PUFAs (EPA and DHA) display antimicrobial properties against Gram-positive bacteria by compromising cell membranes [70,114]. While these antimicrobial effects of SCFAs, MCFAs, and n-3 PUFAs may contribute to preventing gut dysbiosis and inflammation [25,100,101], and potentially reduce TMA lyase expression [20], direct experimental evidence directly linking fatty acid-induced antimicrobial effects to reduced TMAO levels is lacking. n-3 PUFAs also counteract dysbiosis through anti-inflammatory effects that enhance SCFA-producing microorganisms and inhibit LPS production [83,116,117], a key driver of gut inflammation [118]. Additionally, n-3 PUFA supplementation increases probiotic genera such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus while reducing Enterobacteriaceae [105].

Dietary fats also shape gut microbiota through circadian regulation. Gut microbiota display diurnal oscillations that regulate the intestinal clock [119], with SCFAs fluctuating across the day and influencing clock gene expression (PER2, PER3, ARNTL). HFDs disrupt these rhythms by reducing oscillations in SCFA-producing taxa, altering circadian control of lipid metabolism [120]. Circadian disruption from light exposure and feeding patterns thus represents another pathway linking dietary fat–microbiota interactions contribute to metabolic disorders.

6. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Regulating Flavin Monooxygenase 3 Under HFD Conditions

Several studies demonstrate that high-fat diets (HFDs) increase hepatic flavin monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) expression through gut microbiota-dependent mechanisms [3,121]. Research in mice showed that HFD combined with oral carnitine significantly elevated FMO3 expression and plasma TMAO levels compared to HFD alone, while subcutaneous carnitine did not produce this effect indicating that gut microbial metabolism is essential for FMO3 upregulation [121]. A large clinical study (>2500 participants) confirmed that elevated plasma carnitine predicts increased cardiovascular events and mortality only in individuals with high TMAO levels, establishing TMAO as a critical pro-atherosclerotic factor [3].Further research confirmed the microbiota-dependent nature of FMO3 regulation by demonstrating that polyphenolic compounds (corilagin, gallocatechin gallate, epigallocatechin gallate) reduce FMO3 expression by binding microbial CutC protein and inhibiting TMA production [94]. These findings underscore the gut microbiota’s central role in FMO3/TMAO pathways and suggest that targeting microbial enzymes may offer therapeutic strategies for TMAO-related metabolic disorders.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

HFDs significantly alter gut microbiota composition, often leading to metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease. The degree of FA saturation and chain lengths appear to be key determinants of their gut microbiota-modulating effects. While saturated LCFAs have been shown to promote TMA-producing microbial populations, SCFAs and n-3 PUFAs reduce these microbes, indicating that both the type and quantity of dietary FAs significantly influence gut microbiota composition and related disorders. A clearer understanding of how dietary fatty acids affect gut microbiota and metabolic health requires future studies focusing on several key areas. First, more controlled experimental designs are needed where diet composition remains consistent except for the FA type being studied. This can be achieved through FA supplementation rather than using whole oils or fat sources that contain multiple bioactive components. For example, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB), a natural component of olive oil and structural analog of choline, inhibit TMA formation by targeting microbial TMA lyases, raising questions about MUFA findings when olive oil is used as the source. Moreover, certain oils contain polyphenols that independently influence gut microbiota, highlighting the need to control these additional variables. Second, research on the effects of MCFAs and their effects on TMAO levels remains limited despite their growing use in ketogenic diets and MCT-based nutrition. Third, dose–response relationships must be established through well-designed human trials to characterize the dose-dependent effects of different fatty acids on TMAO production and identify thresholds for beneficial or harmful effects. Addressing these gaps is essential for developing targeted dietary and therapeutic strategies to improve metabolic health.

Author Contributions

E.K.: Conceptualization; writing; original draft; investigation. P.B.: Review & editing; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study does not involve any animal or human study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The support and resources provided by Istanbul Technical University Graduate School are gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L. The Gut Microbiome and Its Role in Cardiovascular Diseases. Circulation 2017, 135, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretts, A.M.; Hazen, S.L.; Jensen, P.; Budoff, M.; Sitlani, C.M.; Wang, M.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; DiDonato, J.A.; Lee, Y.; Psaty, B.M.; et al. Association of Trimethylamine N -Oxide and Metabolites With Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2213242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota Metabolism of L-Carnitine, a Nutrient in Red Meat, Promotes Atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Koeth, R.A.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbial Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine and Cardiovascular Risk. New Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Buffa, J.A.; Agatisa-Boyle, B.; Li, X.S.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Trimethylamine N -Oxide (TMAO) Pathway Contributes to Both Development of Renal Insufficiency and Mortality Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gua, C.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y. Increased Circulating Trimethylamine N-Oxide Contributes to Endothelial Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Chronic Kidney Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2071–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppen, E.G.; Garcia, E.; Connelly, M.A.; Jeyarajah, E.J.; Otvos, J.D.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Dullaart, R.P.F. TMAO Is Associated with Mortality: Impact of Modestly Impaired Renal Function. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Le, G.; Xie, Y. Dietary Methionine Restriction Alleviates Choline-Induced Tri-Methylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) Elevation by Manipulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bras, A. Targeting the Gut to Protect the Heart. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut Flora Metabolism of Phosphatidylcholine Promotes Cardiovascular Disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bergeron, N.; Levison, B.S.; Li, X.S.; Chiu, S.; Xun, J.; Koeth, R.A.; Lin, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Impact of Chronic Dietary Red Meat, White Meat, or Non-Meat Protein on Trimethylamine N-Oxide Metabolism and Renal Excretion in Healthy Men and Women. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 40, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisel, S.H.; Warrier, M. Trimethylamine N. -Oxide, the Microbiome, and Heart and Kidney Disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Jameson, E.; Crosatti, M.; Schäfer, H.; Rajakumar, K.; Bugg, T.D.H.; Chen, Y. Carnitine Metabolism to Trimethylamine by an Unusual Rieske-Type Oxygenase from Human Microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4268–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameson, E.; Doxey, A.C.; Airs, R.; Purdy, K.J.; Murrell, J.C.; Chen, Y. Metagenomic Data-Mining Reveals Contrasting Microbial Populations Responsible for Trimethylamine Formation in Human Gut and Marine Ecosystems. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, S.; Heidrich, B.; Pieper, D.H.; Vital, M. Uncovering the Trimethylamine-Producing Bacteria of the Human Gut Microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho-Wolino, K.S.; de FCardozo, L.F.M.; de Oliveira Leal, V.; Mafra, D.; Stockler-Pinto, M.B. Can Diet Modulate Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Production? What Do We Know so Far? Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3567–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Levison, B.S.; Culley, M.K.; Buffa, J.A.; Wang, Z.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Smith, J.D.; et al. γ-Butyrobetaine Is a Proatherogenic Intermediate in Gut Microbial Metabolism of L-Carnitine to TMAO. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Zieba, J.K.; Foegeding, N.J.; Torres, T.P.; Shelton, C.D.; Shealy, N.G.; Byndloss, A.J.; Cevallos, S.A.; Gertz, E.; Tiffany, C.R.; et al. High-Fat Diet–Induced Colonocyte Dysfunction Escalates Microbiota-Derived Trimethylamine N -Oxide. Science 2021, 373, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, K.A.; Vivas, E.I.; Amador-Noguez, D.; Rey, F.E. Intestinal Microbiota Composition Modulates Choline Bioavailability from Diet and Accumulation of the Proatherogenic Metabolite Trimethylamine- N -Oxide. mBio 2015, 6, e02481-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quareshy, M.; Shanmugam, M.; Townsend, E.; Jameson, E.; Bugg, T.D.H.; Cameron, A.D.; Chen, Y. Structural Basis of Carnitine Monooxygenase CntA Substrate Specificity, Inhibition, and Intersubunit Electron Transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-K.; Panyod, S.; Liu, P.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Kao, H.-L.; Chuang, H.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zou, H.-B.; Kuo, H.-C.; Kuo, C.-H.; et al. Characterization of TMAO Productivity from Carnitine Challenge Facilitates Personalized Nutrition and Microbiome Signatures Discovery. Microbiome 2020, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-del Campo, A.; Bodea, S.; Hamer, H.A.; Marks, J.A.; Haiser, H.J.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Balskus, E.P. Characterization and Detection of a Widely Distributed Gene Cluster That Predicts Anaerobic Choline Utilization by Human Gut Bacteria. mBio 2015, 6, e00042-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, S.; Balskus, E.P. Microbial Conversion of Choline to Trimethylamine Requires a Glycyl Radical Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 21307–21312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, D.; Jiang, R.; Ge, L.; Tong, C.; Xu, K. Associations among Dietary Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, the Gut Microbiota, and Intestinal Immunity. Mediators Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 8879227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, N.; Arboleya, S.; Allison, J.; Kaliszewska, A.; Higarza, S.G.; Gueimonde, M.; Arias, J.L. The Relationship between Choline Bioavailability from Diet, Intestinal Microbiota Composition, and Its Modulation of Human Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, O.; Zubair, N.; Conomos, M.P.; Xu, X.; Rohwer, J.E.; Krafft, C.E.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Magis, A.T. A Multi-Omic Association Study of Trimethylamine N-Oxide. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lim, J. The Emerging Role of Gut Hormones. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. Influence of Foods and Nutrition on the Gut Microbiome and Implications for Intestinal Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Miller, M.; Rhyne, J.; Wang, Z.; Hazen, S.L. Differential Effect of Short-Term Popular Diets on TMAO and Other Cardio-Metabolic Risk Markers. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M.; Raes, J.; Pelletier, E.; Le Paslier, D.; Yamada, T.; Mende, D.R.; Fernandes, G.R.; Tap, J.; Bruls, T.; Batto, J.-M.; et al. Enterotypes of the Human Gut Microbiome. Nature 2011, 473, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deehan, E.C.; Yang, C.; Perez-Muñoz, M.E.; Nguyen, N.K.; Cheng, C.C.; Triador, L.; Zhang, Z.; Bakal, J.A.; Walter, J. Precision Microbiome Modulation with Discrete Dietary Fiber Structures Directs Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 389–404.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-Microbiota-Targeted Diets Modulate Human Immune Status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyaz, S.; Chung, C.; Mou, H.; Bauer-Rowe, K.E.; Xifaras, M.E.; Ergin, I.; Dohnalova, L.; Biton, M.; Shekhar, K.; Eskiocak, O.; et al. Dietary Suppression of MHC Class II Expression in Intestinal Epithelial Cells Enhances Intestinal Tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1922–1935.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadaideh, K.S.; Carmody, R.N. Host-Microbial Interactions in the Metabolism of Different Dietary Fats. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, R.; Parhofer, K.G.; Woenckhaus, M.; Wrede, C.E.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Schölmerich, J.; Bollheimer, L.C. Defining High-Fat-Diet Rat Models: Metabolic and Molecular Effects of Different Fat Types. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006, 36, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; D’Angelo, S. Gut Microbiota Modulation Through Mediterranean Diet Foods: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients 2025, 17, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, J.C.; Farzan, S.F.; Hibberd, P.L.; Karagas, M.R. Normal Neonatal Microbiome Variation in Relation to Environmental Factors, Infection and Allergy. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2012, 24, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, A.; Neu, J.; Riezzo, G.; Raimondi, F.; Martinelli, D.; Francavilla, R.; Indrio, F. Gastrointestinal Function Development and Microbiota. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2013, 39, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrazza, R.M.; Neu, J. The Altered Gut Microbiome and Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Clin. Perinatol. 2013, 40, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, M.L.; Starkweather, A.R. Antenatal Microbiome. Nurs. Res. 2015, 64, 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapp, M.; Aurora, N.; Herrera, L.; Bhatia, M.; Wilen, E.; Wakefield, S. Gut Microbiota’s Effect on Mental Health: The Gut-Brain Axis. Clin. Pract. 2017, 7, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siezen, R.J.; Kleerebezem, M. The Human Gut Microbiome: Are We Our Enterotypes? Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 550–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking Long-Term Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Raes, J. Microbiology Meets Big Data: The Case of Gut Microbiota-Derived Trimethylamine. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karačić, A.; Renko, I.; Krznarić, Ž.; Klobučar, S.; Liberati Pršo, A.-M. The Association between the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio and Body Mass among European Population with the Highest Proportion of Adults with Obesity: An Observational Follow-Up Study from Croatia. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yin, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Yin, Y.; Tan, B.; Chen, J. Supplementation With Lycium Barbarum Polysaccharides Reduce Obesity in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice by Modulation of Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 719967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and Disease Markers Correlate with Gut Microbiome Composition across Thousands of People. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckhed, F.; Ding, H.; Wang, T.; Hooper, L.V.; Koh, G.Y.; Nagy, A.; Semenkovich, C.F.; Gordon, J.I. The Gut Microbiota as an Environmental Factor That Regulates Fat Storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15718–15723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeevi, D.; Korem, T.; Zmora, N.; Israeli, D.; Rothschild, D.; Weinberger, A.; Ben-Yacov, O.; Lador, D.; Avnit-Sagi, T.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; et al. Personalized Nutrition by Prediction of Glycemic Responses. Cell 2015, 163, 1079–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michail, S.; Lin, M.; Frey, M.R.; Fanter, R.; Paliy, O.; Hilbush, B.; Reo, N.V. Altered Gut Microbial Energy and Metabolism in Children with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Hyun, J. Altered Lipid Metabolism as a Predisposing Factor for Liver Metastasis in MASLD. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-J.; Lee, H.; Chanda, D.; Thoudam, T.; Kang, H.-J.; Harris, R.A.; Lee, I.-K. The Role of Pyruvate Metabolism in Mitochondrial Quality Control and Inflammation. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-Level Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Beneficially Impacts the Gut Microbiota and Associated Metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ma, W.; Rinott, E.; Ivey, K.L.; Shai, I.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; et al. The Gut Microbiome Modulates the Protective Association between a Mediterranean Diet and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anto, L.; Blesso, C.N. Interplay between Diet, the Gut Microbiome, and Atherosclerosis: Role of Dysbiosis and Microbial Metabolites on Inflammation and Disordered Lipid Metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 105, 108991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2015, 39, 18S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassa, T.; Kihara, A. Metabolism of Very Long-Chain Fatty Acids: Genes and Pathophysiology. Biomol. Ther. 2014, 22, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panth, N.; Abbott, K.A.; Dias, C.B.; Wynne, K.; Garg, M.L. Differential Effects of Medium- and Long-Chain Saturated Fatty Acids on Blood Lipid Profile: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; D’Apolito, O.; Garofalo, D.; Paglia, G.; Dello Russo, A. Profiling of Acylcarnitines and Sterols from Dried Blood or Plasma Spot by Atmospheric Pressure Thermal Desorption Chemical Ionization (APTDCI) Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2011, 1811, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereyra, A.S.; McLaughlin, K.L.; Buddo, K.A.; Ellis, J.M. Medium-Chain Fatty Acid Oxidation Is Independent of L-Carnitine in Liver and Kidney but Not in Heart and Skeletal Muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2023, 325, G287–G294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, K.; Iacob, B.-C.; Bodoki, E.; Oprean, R. Investigating the Thermal Stability of Omega Fatty Acid-Enriched Vegetable Oils. Foods 2024, 13, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praagman, J.; Beulens, J.W.; Alssema, M.; Zock, P.L.; Wanders, A.J.; Sluijs, I.; van der Schouw, Y.T. The Association between Dietary Saturated Fatty Acids and Ischemic Heart Disease Depends on the Type and Source of Fatty Acid in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Netherlands Cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Hussain, M.; Jiang, B.; Zheng, L.; Pan, Y.; Hu, J.; Khan, A.; Ashraf, A.; Zou, X. Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Metabolism and Health Implications. Prog. Lipid Res. 2023, 92, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.S.; Maki, K.C.; Calder, P.C.; Belury, M.A.; Messina, M.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Harris, W.S. Perspective on the Health Effects of Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Commonly Consumed Plant Oils High in Unsaturated Fat. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Neelakantan, N.; Wu, Y.; Lote-Oke, R.; Pan, A.; van Dam, R.M. Palm Oil Consumption Increases LDL Cholesterol Compared with Vegetable Oils Low in Saturated Fat in a Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1549–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, S.; Karelis, A.; Bergeron, K.-F.; Mounier, C. Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Health: The Potential Beneficial Effects of a Medium Chain Triglyceride Diet in Obese Individuals. Nutrients 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Wang, Q.; Yi, S.; Liu, X.; Jin, H.; Xu, J.; Wen, G.; Zhu, J.; Tuo, B. The Source of the Fat Significantly Affects the Results of High-Fat Diet Intervention. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, P.; Deng, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, P.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, M. Impact of Dietary Fatty Acid Composition on the Intestinal Microbiota and Fecal Metabolism of Rats Fed a High-Fructose/High-Fat Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolters, M.; Ahrens, J.; Romaní-Pérez, M.; Watkins, C.; Sanz, Y.; Benítez-Páez, A.; Stanton, C.; Günther, K. Dietary Fat, the Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Health—A Systematic Review Conducted within the MyNewGut Project. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2504–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, M.; Pang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, L. Structural Resilience of the Gut Microbiota in Adult Mice under High-Fat Dietary Perturbations. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, N.; Derrien, M.; Bosch-Vermeulen, H.; Oosterink, E.; Keshtkar, S.; Duval, C.; de Vogel-van den Bosch, J.; Kleerebezem, M.; Müller, M.; Van Der Meer, R. Saturated Fat Stimulates Obesity and Hepatic Steatosis and Affects Gut Microbiota Composition by an Enhanced Overflow of Dietary Fat to the Distal Intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G589–G599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Hougen, H.; Vollmer, A.C.; Hiebert, S.M. Gut Bacteria Profiles of Mus Musculus at the Phylum and Family Levels Are Influenced by Saturation of Dietary Fatty Acids. Anaerobe 2012, 18, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, E.; O’ Doherty, R.M.; Murphy, E.F.; Wall, R.; O’ Sullivan, O.; Nilaweera, K.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Cotter, P.D.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. Impact of Dietary Fatty Acids on Metabolic Activity and Host Intestinal Microbiota Composition in C57BL/6J Mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, R.; Tremaroli, V.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Cani, P.D.; Bäckhed, F. Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota and Dietary Lipids Aggravates WAT Inflammation through TLR Signaling. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, A.N.; Tingö, L.; Brummer, R.J. The Potential Effects of Probiotics and ω-3 Fatty Acids on Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andújar-Tenorio, N.; Prieto, I.; Cobo, A.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.M.; Hidalgo, M.; Segarra, A.B.; Ramírez, M.; Gálvez, A.; Martínez-Cañamero, M. High Fat Diets Induce Early Changes in Gut Microbiota That May Serve as Markers of Ulterior Altered Physiological and Biochemical Parameters Related to Metabolic Syndrome. Effect of Virgin Olive Oil in Comparison to Butter. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0271634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Roberts, A.B.; Buffa, J.A.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Org, E.; Gu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zamanian-Daryoush, M.; Culley, M.K.; et al. Non-Lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell 2015, 163, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, C.; García-Cañas, V. Dietary Bioactive Ingredients to Modulate the Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolite TMAO. New Opportunities for Functional Food Development. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6745–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Hao, W.; Kwek, E.; Lei, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Ma, K.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ho, H.M.; He, W.-S.; et al. Fish Oil Is More Potent than Flaxseed Oil in Modulating Gut Microbiota and Reducing Trimethylamine- N. -Oxide-Exacerbated Atherogenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13635–13647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Du, L.; Randell, E.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Li, D. Effect of Different Phosphatidylcholines on High Fat Diet-Induced Insulin Resistance in Mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berge, R.K.; Ramsvik, M.S.; Bohov, P.; Svardal, A.; Nordrehaug, J.E.; Rostrup, E.; Bruheim, I.; Bjørndal, B. Krill Oil Reduces Plasma Triacylglycerol Level and Improves Related Lipoprotein Particle Concentration, Fatty Acid Composition and Redox Status in Healthy Young Adults—A Pilot Study. Lipids Health Dis. 2015, 14, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.A.; Shih, Y.; Wang, W.; Oda, K.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabaté, J.; Haddad, E.; Rajaram, S.; Caudill, M.A.; Burns-Whitmore, B. Egg N-3 Fatty Acid Composition Modulates Biomarkers of Choline Metabolism in Free-Living Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarian Women of Reproductive Age. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloysius, T.A.; Tillander, V.; Pedrelli, M.; Dankel, S.N.; Berge, R.K.; Bjørndal, B. Plasma Cholesterol- and Body Fat-Lowering Effects of Chicken Protein Hydrolysate and Oil in High-Fat Fed Male Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Shi, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Li, D. Sandalwood Seed Oil Improves Insulin Sensitivity in High-Fat/High-Sucrose Diet-Fed Rats Associated with Altered Intestinal Microbiota and Its Metabolites. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9739–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Li, K.; Liu, Y.; Hettiarachichi, D.S.; Sunderland, B.; Li, D. Sandalwood Seed Oil Ameliorates Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Regulating the JNK/NF-ΚB Inflammatory and PI3K/AKT Insulin Signaling Pathways. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 2312–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliannan, K.; Li, X.-Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Q.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hao, L.; Xie, S.; Kang, J.X. Multi-Omic Analysis in Transgenic Mice Implicates Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Imbalance as a Risk Factor for Chronic Disease. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zheng, X.; Feng, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. Gut Microbiota-Dependent Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide Contributes to Cardiac Dysfunction in Western Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laugerette, F.; Furet, J.-P.; Debard, C.; Daira, P.; Loizon, E.; Géloën, A.; Soulage, C.O.; Simonet, C.; Lefils-Lacourtablaise, J.; Bernoud-Hubac, N.; et al. Oil Composition of High-Fat Diet Affects Metabolic Inflammation Differently in Connection with Endotoxin Receptors in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E374–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Wolf, P.G.; Carbonero, F.; Zhong, W.; Reid, T.; Gaskins, H.R.; McIntosh, M.K. Intestinal and Systemic Inflammatory Responses Are Positively Associated with Sulfidogenic Bacteria Abundance in High-Fat–Fed Male C57BL/6J Mice. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Huang, C.; Gao, F.; peng Hu, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, J.; et al. Polyphenols from Hickory Nut Reduce the Occurrence of Atherosclerosis in Mice by Improving Intestinal Microbiota and Inhibiting Trimethylamine N-Oxide Production. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, T.; Gao, X.; Xue, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. Fish Oil Affects the Metabolic Process of Trimethylamine N-Oxide Precursor through Trimethylamine Production and Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase Activity in Male C57BL/6 Mice. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 56655–56661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, L.E.; Djuric, Z.; Angiletta, C.J.; Mitchell, C.M.; Baugh, M.E.; Davy, K.P.; Neilson, A.P. A Mediterranean Diet Does Not Alter Plasma Trimethylamine N. -Oxide Concentrations in Healthy Adults at Risk for Colon Cancer. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2138–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J.; et al. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 789–802.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.L.; Ericsson, A.C. Microbiota and Reproducibility of Rodent Models. Lab Anim. 2017, 46, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaw, L.J.; Jäger, A.K.; van Staden, J. Antibacterial Effects of Fatty Acids and Related Compounds from Plants. South Afr. J. Bot. 2002, 68, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J. Fiber and Prebiotics: Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Chen, C.; Fu, J.; Zhu, L.; Shu, J.; Jin, M.; Wang, Y.; Zong, X. Dietary Fatty Acids in Gut Health: Absorption, Metabolism and Function. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-Gut Microbiota Metabolic Interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigottier-Gois, L. Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The Oxygen Hypothesis. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devkota, S.; Wang, Y.; Musch, M.W.; Leone, V.; Fehlner-Peach, H.; Nadimpalli, A.; Antonopoulos, D.A.; Jabri, B.; Chang, E.B. Dietary-Fat-Induced Taurocholic Acid Promotes Pathobiont Expansion and Colitis in Il10−/− Mice. Nature 2012, 487, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi Saravi, S.S.; Bonetti, N.R.; Pugin, B.; Constancias, F.; Pasterk, L.; Gobbato, S.; Akhmedov, A.; Liberale, L.; Lüscher, T.F.; Camici, G.G.; et al. Lifelong Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acid Suppresses Thrombotic Potential through Gut Microbiota Alteration in Aged Mice. iScience 2021, 24, 102897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Shi, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Bifidobacterium Breve and Bifidobacterium Longum Attenuate Choline-Induced Plasma Trimethylamine N-Oxide Production by Modulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, M.; Caesar, R. Dietary Lipids, Gut Microbiota and Lipid Metabolism. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2019, 20, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGruttola, A.K.; Low, D.; Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016, 22, 1137–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell 2014, 157, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocvirk, S.; O’Keefe, S.J.D. Dietary Fat, Bile Acid Metabolism and Colorectal Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 73, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Fujita, Y.; Hagio, M.; Ishizuka, S.; Ogura, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Fukiya, S.; Yokota, A. Bile Acid is a Responsible Host Factor for High-Fat Diet-Induced Gut Microbiota Alterations in Rats: Proof of the “Bile Acid Hypothesis. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2025, 44, 2024–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, L.K.; Holma, R.; Eggert, A.; Korpela, R. A Novel Mechanism for Gut Barrier Dysfunction by Dietary Fat: Epithelial Disruption by Hydrophobic Bile Acids. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G227–G234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinck, J.E.; Sinha, A.K.; Laursen, M.F.; Dragsted, L.O.; Raes, J.; Uribe, R.V.; Walter, J.; Roager, H.M.; Licht, T.R. Intestinal PH: A Major Driver of Human Gut Microbiota Composition and Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 639–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casillas-Vargas, G.; Ocasio-Malavé, C.; Medina, S.; Morales-Guzmán, C.; Del Valle, R.G.; Carballeira, N.M.; Sanabria-Ríos, D.J. Antibacterial Fatty Acids: An Update of Possible Mechanisms of Action and Implications in the Development of the next-Generation of Antibacterial Agents. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, X.; Cheng, R.; Shen, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Jiang, G.; Wen, L.; Li, X.; Peng, X.; Liao, Y.; et al. High-Fat Diet Induces Sarcopenic Obesity in Natural Aging Rats through the Gut–Trimethylamine N-Oxide–Muscle Axis. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 70, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, G. Microbiota, a New Playground for the Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Cardiovascular Diseases. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocellin, M.C.; Camargo, C.d.Q.; Fabre, M.E.d.S.; Trindade, E.B.S.d.M. Fish Oil Effects on Quality of Life, Body Weight and Free Fat Mass Change in Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Triple Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 31, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between Lipopolysaccharide and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, V.; Gibbons, S.M.; Martinez, K.; Hutchison, A.L.; Huang, E.Y.; Cham, C.M.; Pierre, J.F.; Heneghan, A.F.; Nadimpalli, A.; Hubert, N.; et al. Effects of Diurnal Variation of Gut Microbes and High-Fat Feeding on Host Circadian Clock Function and Metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotti, S.; Dinu, M.; Colombini, B.; Amedei, A.; Sofi, F. Circadian Rhythms, Gut Microbiota, and Diet: Possible Implications for Health. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, N.; Gao, J.; Li, H.; Cai, W.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Niu, X.; Yang, G.; Zhou, X.; et al. The Effect of Different l-Carnitine Administration Routes on the Development of Atherosclerosis in ApoE Knockout Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).