Abstract

Background: Energy-dense non-essential snacks are subject to 8% excise tax in Mexico. Objectives: To model the impact on diet quality of (1) replacing energy-dense snacks with pistachios and (2) adding small amounts of pistachios to the diet. Methods: Data came from the Mexico National Health and Nutrition survey (ENSANUT, by its Spanish acronym) 2012 (n = 7132) and 2016 (n = 14,764). Dietary intakes were collected using a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Substitution analyses replaced energy-dense snack foods with equicaloric amounts of pistachios (Model 1) or with mixed nuts/seeds (Model 2). Additional analyses (Model 3) added small amounts of pistachios (10–28 g) to the daily diet. Added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat along with protein fiber, vitamins, and minerals were the main nutrients of interest. Dietary nutrient density was assessed using the Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF9.3) Index. Separate modeling analyses were performed for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 and for children and adults. Results: Energy-dense foods, mostly sweet, accounted for about 20% of daily energy. Modeled diets with pistachios and mixed nuts/seeds were much lower in added sugars (<8% of dietary energy) and in sodium (<550 mg/day) and were higher in protein, fiber, mono- and polyunsaturated fats, potassium, and magnesium (p < 0.05). Significant improvements in dietary quality held across all socio-demographic strata. Adding small amounts of pistachios (10–28 g) to the diet (Model 3) increased calories but also led to better diets and higher NRF9.3 dietary nutrient density scores. Conclusions: Modeled diets with pistachios replacing energy-dense snack foods had less added sugars and sodium and more protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Adding small amounts of pistachios also led to better diets. Pistachios are a healthy snack and can be an integral component of healthy diets.

1. Introduction

Tree nuts are nutrient-dense foods with many recognized health benefits [,]. Pistachios, almonds, walnuts, and pecans are valuable dietary sources of healthy fats, plant-based proteins, dietary fiber, and a wide range of vitamins and minerals, notably vitamin E, magnesium, zinc, copper, and selenium [,,]. Tree nuts also contain phytosterols and polyphenols with antioxidant properties and well-established benefits for cardiometabolic health [,,,]. Dietary guidelines in the US and in Mexico recommend consuming more nuts as a part of a healthy, balanced, and sustainable diet [,]. Nuts are also prominently featured in the EAT-Lancet Planetary Health Diet [], with a recommended consumption as high as 50 g per day.

Most nuts, including peanuts, have a high energy density in excess of 275 kcal/100 g []. In January 2014, Mexico introduced an 8% excise tax on processed “non-essential energy-dense foods”, defined as those with ≥275 kcal per 100 g [,]. The list included chips, cakes, pastries, frozen desserts, sweets, chocolates, and similar snack items. Energy-dense pistachios and other nuts were subject to the 8% tax, if packaged and sold as non-essential, energy-dense foods. The tax covered those tree nuts, ground nuts, and seeds that contained high levels of added sugars, salt, or fat, as well as other ingredients or additives not typically found in whole nuts []. The concern was that salted or flavored nuts may have contributed added sugars or salt to the diet []. In an effort to reduce the consumption of added sugars, an excise tax was also imposed on beverages with low energy density but high added sugars content [].

The excise tax was based on a single energy density threshold of ≥275 kcal/100 g and not on nutrient content. Energy density is calculated as calories per 100 g (kcal/100 g), whereas nutrient density is typically calculated in terms of nutrients per 100 g, per 100 kcal, or per serving []. In general, energy density and nutrient density are inversely linked. However, tree nuts are an exception to the general rule, being both energy-dense and nutrient-rich []. Low-sugar fortified ready-to-eat (RTE) cereals are another exception, since they contain both energy and essential nutrients. The well-established Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) Index has consistently given high nutrient density scores to tree nuts, including pistachios, almonds, and walnuts [].

This diet modeling study explored the impact on diet quality metrics of replacing energy-dense foods, many categorized as taxed snacks, with pistachios and with mixed nuts/seeds. The first goal was to identify typical energy-dense snacks that were subject to tax, such as chips, cakes, pastries, frozen desserts, sweets, chocolates, and other such items in the ENSANUT nutrient composition database. To identify populations at greatest need for potential interventions, analyses were conducted across diverse socio-demographic strata. This was carried out to identify subgroups that would most benefit from adopting healthier snacks. Further analyses modeled the likely impact on diet quality of adding small amounts of pistachios to everyday diets of children and adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 Population Samples

The present analyses were based on two cycles of the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey (ENSANUT, by its acronym in Spanish) 2012 and 2016 [,]. ENSANUT is the only nationally representative, multistage probabilistic survey of nutrition and health in Mexico. The ENSANUT database contains socio-demographic information and some health data. Analyses were conducted separately for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 survey waves and separately for children and adults.

Sex was registered as female/male. Socioeconomic status (SES), used by the ENSANUT as an index of household wellbeing, was constructed by analyzing key components related to household characteristics and ownership of household items. For the present analyses, the standardized variable was categorized into SES tertiles (low, medium, and high) for each survey year (2012 and 2016) []. The geographic zones were North, Center, South, and Mexico City. Area of residence (urban/rural) was defined according to the number of inhabitants: <2500 for rural and ≥2500 for urban localities. The distribution of respondents who completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) by socio-demographic strata are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Participant sample characteristics for ENSANUT 2012 and ENSANUT 2016 and for total 2012–2016 waves by socio-demographic variables.

2.2. The ENSANUT Food Frequency Questionnaire

Dietary intakes were collected using a previously used and validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) []. Participants were excluded if their food consumption exceeded 3 standard deviations (SD) from the mean; if their total energy intake was <500 kcal/day or >5000 kcal/day; or if their protein or fiber intake-to-requirement ratios were greater than 3 SD from the mean, or if their energy intakes were greater than 4 SD from the mean. Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded.

The FFQ instruments used in ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 surveys listed 127 principal food items from multiple food groups. Nutritional data tables used to calculate energy and nutrient intakes are available from the Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (INSP) at https://insp.mx/informacion-relevante/bam-bienvenida (last access: 29 October 2025).

Relevant to the present modeling study were chips, cakes, pastries, frozen desserts, sweets, chocolates, and other items, many of which had energy density >275 kcal/100 g and fell into the category of taxable non-essential snacks. A full list of taxable FFQ items (provided in Table 2) was established using prior National Health Institute (INSP) papers and government data. Pistachios and other nuts were not a part of the ENSANUT FFQ and were not listed in the FFQ nutrient composition database. Their nutrient composition is provided for comparison purposes.

Table 2.

Nutrient composition of taxed food categories.

2.3. Nutrient Composition of Pistachio Snacks and Mixed Nuts/Seed Snacks

Composite nutrient profiles for pistachios and for mixed nuts/seeds were created for use in substitution analyses. Those profiles were based on the relative amounts consumed in the 24 h food recalls in ENSANUT 2016. Pistachios were dry roasted pistachios and unsalted pistachios. Mixed nuts were peeled roasted peanuts, pumpkin seeds, pecans, sesame seeds, and almonds. Mean consumption in g/day (shown in Table 3) was as follows: pumpkin seed (Semilla de calabaza): 32.46 g/day; pecan nut (Nuez): 27.74 g/day; sesame seed (Ajonjolí): 5.23 g/day; and almonds (Almendras): 1.57 g/day.

Table 3.

Weights used to develop nutrient profiles for replacement snacks in Model 1 (pistachios) and Model 2 (mixed nuts/seeds).

2.4. Substitution Modeling (Models 1 and 2) and Addition Modeling (Model 3)

Modeling analyses were conducted to determine the impact of replacing energy-dense snack type foods with isocaloric amounts of pistachios and mixed nuts/seeds on the nutrient content of modeled diets.

Two substitution models were constructed. Substitution Model 1 replaced energy-dense solid snacks with equicaloric amounts of pistachios. Substitution Model 2 replaced energy-dense solid snacks with an equicaloric mix of nuts and seeds as recommended by the Mexico Dietary Guidelines []. Beverages and healthy snacks (e.g., nuts, vegetables, fruits) were not replaced. We expected to see improvements in dietary nutrients of public health concern, that is, for reductions in added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat; for higher dietary protein and fiber; and for a higher diet quality overall. We also expected to see greater amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids, more plant proteins, and higher levels of several vitamins and minerals.

In addition, Model 3 added small amounts (from 10 g to 28 g) of pistachios to the observed diets of teenagers (ages 16–19 y) and adults (age ≥ 20 y). Addition modeling for children respected the Mexican Dietary Guidelines. For the <5 y age group, Model 3 added 10 g of pistachios for both girls and boys. For the 5–11 y age group, Model 3 added 13 g of pistachios to the observed diets for girls and 15 g for boys. For the 12–15 y age group, Model 3 added 18 g of pistachios to diets of girls and 26 g to diets of boys, as recommended by the 2023 Mexican Dietary Guidelines.

2.5. Diet-Level Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) Diet Quality Score

Diet quality was assessed in two ways. First, the observed and modeled diets were compared on the content of added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat. Additional analyses were conducted for the two diets’ content of protein, fiber, and selected vitamins and minerals. Second, the classic diet level NRF9.3 score, calculated for 2000 kcal, was used to assess nutrient density of the observed and the modeled diets. The diet level NRF9.3 score was based on two sub-scores NR9 and LIM. The NR9 sub-score was based on 9 nutrients to encourage: protein, fiber, calcium, iron, potassium, magnesium, vitamin A, vitamin C, and vitamin D. The final score was given by the sum of % percent daily values (DV) of the 9 nutrients to encourage minus the sum of excess (in %) for the 3 nutrients to limit (added sugars, saturated fatty acids, and sodium). In other words, NRF9.3 = NR9 − LIM.

2.6. Plan of Analysis

Separate substitution modeling analyses were conducted for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 and for children and adults. Comparisons, based on t-tests and one way ANOVA tests, were made between added sugars and sodium content of the observed and in the isocaloric modeled diets, Models 1 and 2. Further analyses examined protein, fiber, and nutrient content of the observed and modeled diets for the total population and by age group (children, adults). Separate addition modeling analyses (Model 3) were conducted for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 and for children and adults. Those analyses also examined protein, fiber, and nutrient content of the observed and modeled diets for the total population and by age group (children, adults).

To assess the differential impact of replacing snacks with pistachios or with nuts/seeds across socio-demographic groups, separate modeling analyses were conducted for populations stratified by sex, age group (children ages 0–4 y, 5–11 y, and 12–19 y and adults 20–30 y, 31–50 y, 51–70 y, and >70 y); socioeconomic status (low, medium, and high); and for rural and urban area of residence. Model performance was tested using mean difference t-tests with respect to the observed diets with analyses adjusted for the ENSANUT complex survey design. Data provided were means, standard errors (SE), and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Significance level for differences among groups was set at 0.001. All analyses were survey weighted to account for the ENSANUT survey design and reflect the behaviors of the Mexican population. Analyses were conducted in Stata 18 (College Station, TX, USA) statistical package and R-Studio.

3. Results

3.1. Observed ENSANUT 2012 Data for Children and Adults

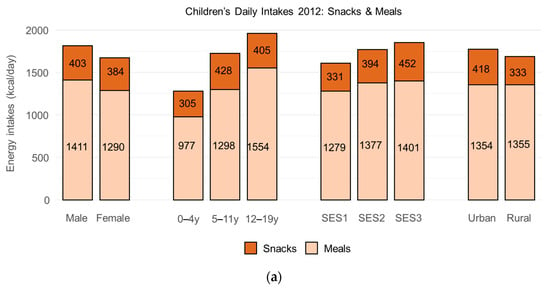

ENSANUT 2012 daily energy intakes for children are shown in Figure 1a; the corresponding data for adults are in Figure 1b. Mean energy intake for children was 1750 kcal/day (1815 kcal/day for boys and 1674 kcal/day for girls). Higher daily energy intakes were associated with male sex, higher age group, higher SES, and urban residence (all p < 0.001). Mean energy intake for adults was 1806 kcal/day (2013 kcal/day for males and 1614 kcal/day for females). Higher energy intakes were associated with male sex, younger age group, higher SES, and urban residence (all p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Daily energy intakes by food category for children (a) and adults (b) by socio-demographic strata in ENSANUT 2012.

Energy-dense foods in the taxed snack categories, shown in Figure 1a,b, accounted for 22.7% of dietary energy for children and 16.6% of energy for adults. Calories from energy-dense foods were higher for older children and were associated with higher household incomes and urban residence. Calories from energy-dense foods were higher for younger adults and were associated with higher household incomes and urban residence.

Dietary intakes of energy (kcal/day), added sugars (g/day), and sodium (mg/day) are shown in Table 4. Data are shown separately for children and for adults. Mean intake of added sugars for children was 63.2 g/day (equivalent to 253 kcal energy from added sugars). Mean sodium intake was 2149 mg/day. Higher intakes of added sugars and sodium were associated with male sex, older age group, higher SES, and urban residence (all p < 0.001). Mean intake of added sugars for adults was 58.3 g/day (equivalent to 233 kcal energy from added sugars). Mean sodium intake was 2210 mg/day. Higher intakes of added sugars and sodium were likewise associated with male sex, younger age group, higher SES, and urban residence (all p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Energy (kcal/day), added sugars (g/day), and sodium (mg/day) in observed diets of children and adults by socio-demographics. ENSANUT 2012.

3.2. Substitution Modeling (Models 1 and 2) and Addition Modeling (Model 3)

Table 5 shows that the modeled diets in ENSANUT 2012 were lower in added sugars, sodium and saturated fat (all p < 0.001) and also lower in carbohydrates (p < 0.001). The modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, potassium, and magnesium (p < 0.001). The modeled diets were higher in total fat, mostly MUFA and PUFA, both of which were significantly higher than in the observed diets. The amount of saturated fat was lower in Model 1 and not significantly higher in Model 2. These results for Models 1 and 2 were significant for both children and adults.

Table 5.

ENSANUT 2012. The observed and modeled data of children (1–19 years) and adults (≥20 y). Substitution Models 1 and 2.

Table 6 shows the results for Addition Model 3. Model 3 added pistachios to existing diets of children (1–19 years) and adults (≥20 y). The amounts of pistachios added to the diet depended on age group and were consistent with the Mexican Dietary Guidelines. Model 3 added 28 g of pistachios to the modeled diet for adults; 15 g and 13 g for males and females age 4–19 y; and 10 g of pistachios for children 0–4 y. Table 6 shows that the modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, MUFA and PUFA, and potassium and magnesium. Since this was addition modeling (as opposed to isocaloric substitution), calories increased, and the amounts of added sugars and sodium remained the same—i.e., addition of pistachios did not increase either added sugars or sodium in the modeled diet. Saturated fat was not significantly higher for children.

Table 6.

ENSANUT 2012. Addition Model 3 observed and modeled data of children (1–19 y) and adults (>19 y).

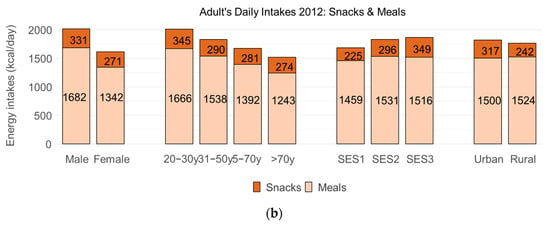

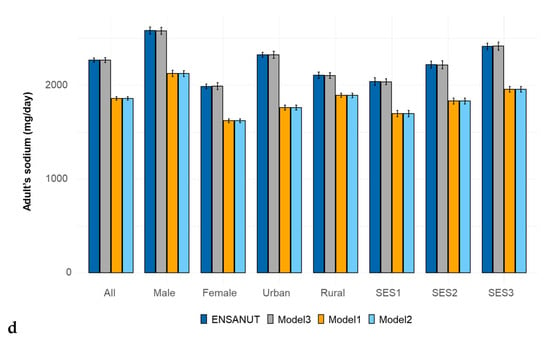

Figure 2 shows the reduction in added sugars (a) and sodium (b) for children and adults in Substitution Models 1 and 2 and Addition Model 3 in ENSANUT 2012.

Figure 2.

Reductions in added sugars (a), sodium (b) for children and added sugars (c), sodium (d) for adults, achieved by isocaloric substitution and addition modeling in ENSANUT 2012 by demographic variables.

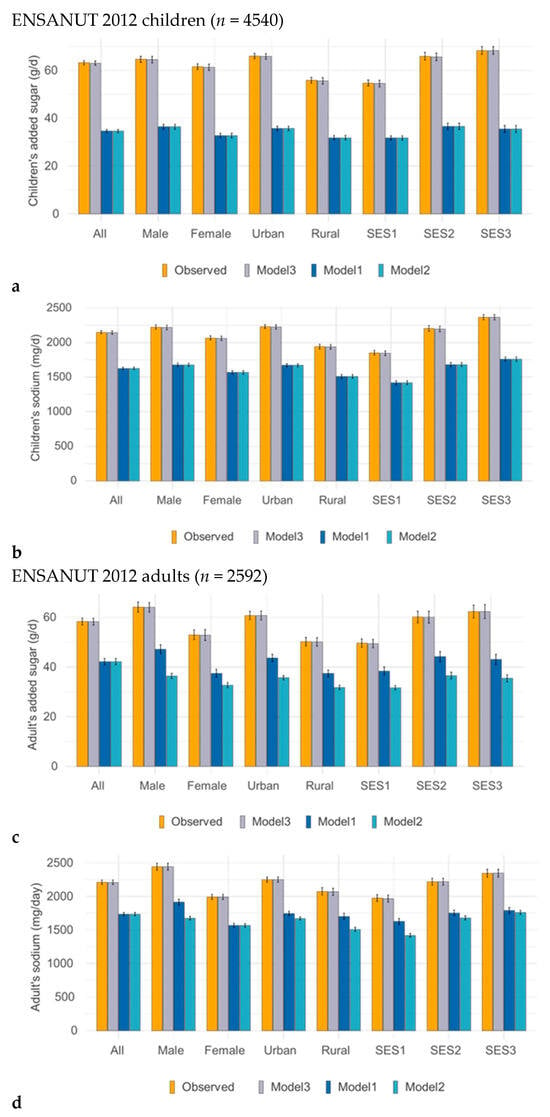

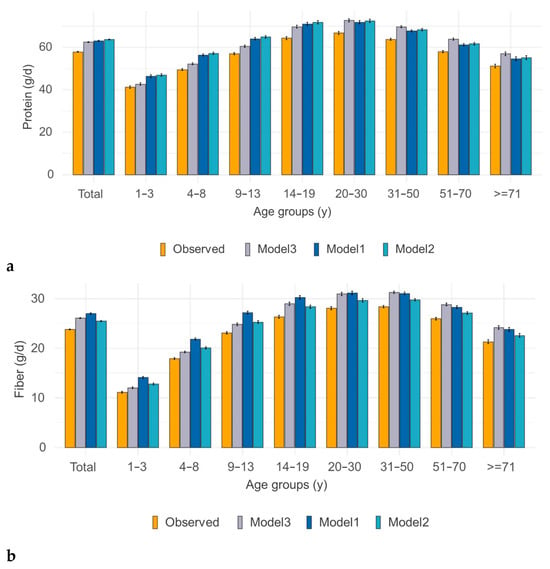

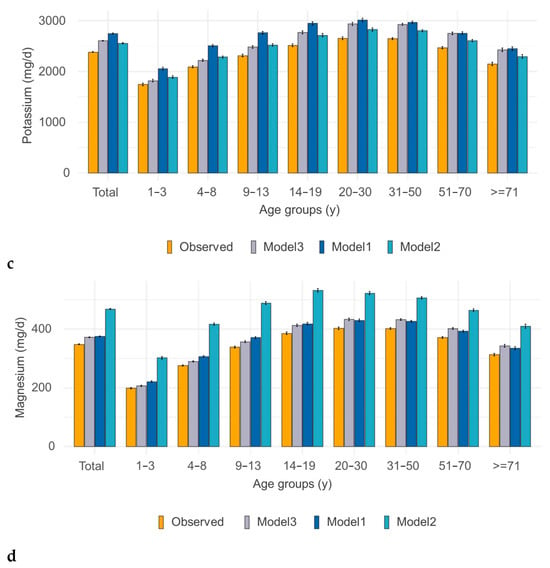

Levels of nutrients of interest were changed following isocaloric substitution in modeled ENSANUT 2012 diets. There were observed increases in protein, fiber, and magnesium, as well as in potassium and vitamin E. There was not much change in vitamin C or calcium. There was a slight reduction in vitamin A and iron at younger age—a likely consequence of replacing sweetened cereal-based snacks made with fortified flour. To show how diets improved for all age groups, Figure 3 shows observed and modeled nutrient values for protein, fiber, potassium, and magnesium by age group for both children and adults.

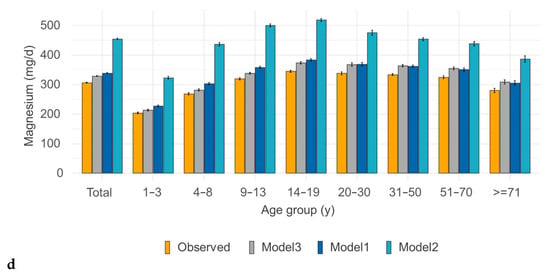

Figure 3.

Changes in protein (a), fiber (b), potassium (c), and magnesium (d) content of modeled diets from observed consumption by type of model: Model 1 (pistachios), Model 2 (mixed nuts/seeds), and Model 3 (adding 28 g of pistachios). ENSANUT 2012.

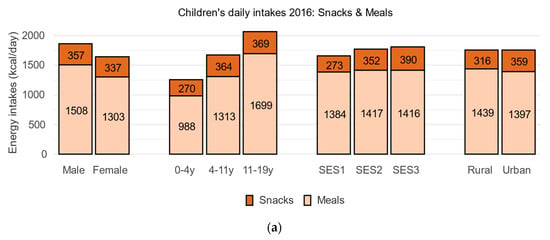

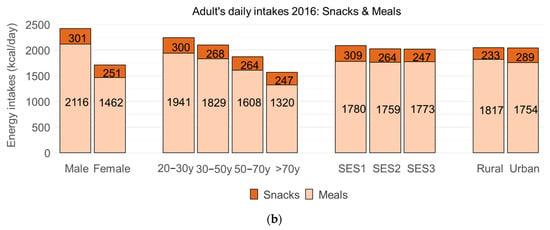

3.3. Observed ENSANUT 2016 Data for Children and Adults

Figure 4 shows energy intakes by food category for children and adults in ENSANUT 2016. Mean energy intake for children was 1757 kcal (1866 kcal/day for boys and 1641 kcal/day for girls). Higher daily energy intakes were associated with male sex, higher age group, and higher SES (all p < 0.001). The urban/rural distinction (prominent in ENSANUT 2012) was no longer observed. Mean energy intake for adults was 2045 kcal/day (2417 kcal/day for males and 1713 kcal/day for females). Higher energy intakes were associated with male sex and younger age groups. Higher SES and urban residence were no longer associated with higher energy intakes.

Figure 4.

Energy intakes (kcal/day) from meals and solid snacks (see Table 2) in the ENSANUT 2016 data for children (a) and adults (b).

Energy-dense foods in the snacks category accounted for 19.8% of dietary energy for children (a decline from 22.7% in 2012) and 14.7% for adults (a decline from 16.6%). Among children, energy-dense foods contributed more energy to diets of older children and were associated with higher household incomes. Among adults, energy-dense foods provided more energy for younger adults and were associated with lower household incomes and rural residence—a reversal of the pattern observed in 2012 ENSANUT.

Table 7 shows dietary intakes of energy (kcal/day), added sugars (g/day), and sodium (mg/day) from ENSANUT 2016. Data are shown separately for children and for adults. Mean intake of added sugars among children was 58.0 g/day (equivalent to 232 kcal energy from added sugars. Mean sodium intake was 2035 mg/day. Higher intakes of sugar among children followed the same trend and the urban/rural distinction was no longer observed. Higher intakes of sodium were associated with male sex, older age group, higher SES, and urban residence (<0.001).

Table 7.

ENSANUT 2016: Characteristics of observed diets for children and adults.

Mean intake of added sugars among adults was 62.7 g/day (251 kcal energy from added sugars). Mean sodium intake was 2270 mg/day. Higher intakes of added sugars among adults were associated with male sex, younger age group, and urban residence but not higher SES. Higher sodium intakes were associated with male sex, younger age, higher SES, and urban residence.

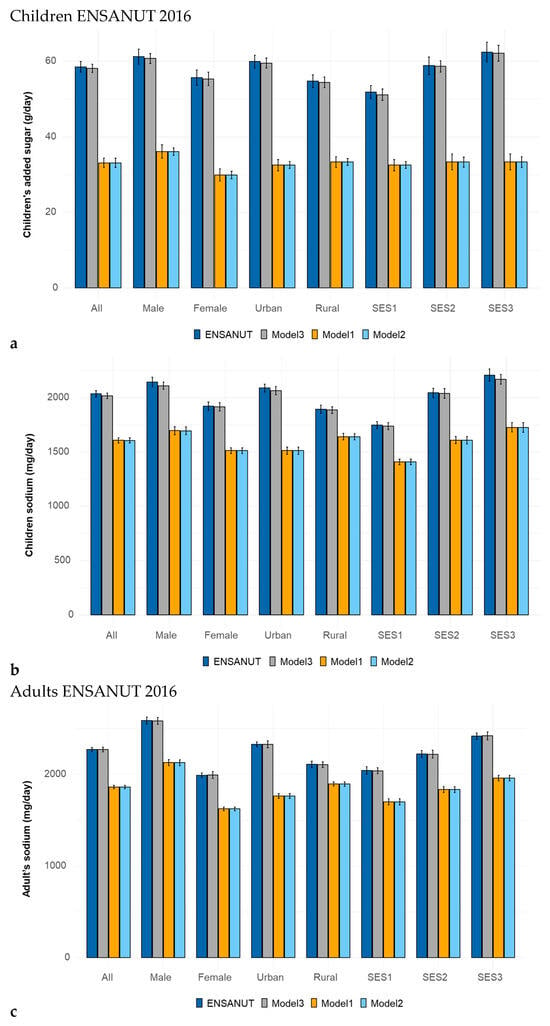

3.4. ENSANUT 2016 Substitution Modeling (Models 1 and 2) and Addition Modeling (Model 3)

Table 8 shows that the modeled diets for children in ENSANUT 2016 were not only lower in added sugars and sodium—but also lower in carbohydrates (see Model 1 and Model 2). The modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, mono- and polyunsaturated fat, potassium, and magnesium. Although total fat was higher, that increase was accounted for by mono- and polyunsaturated fats. The amount of saturated fat was lower in Model 1 and not significantly higher in Model 2.

Table 8.

ENSANUT 2016. The observed and modeled data of children (1–19 years) and adults (≥20 y).

Table 8 also shows that the modeled diets for adults in ENSANUT 2016 were not only lower in added sugars and sodium—but also lower in carbohydrates (see Model 1 and Model 2). The modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, mono- and polyunsaturated fat, potassium, and magnesium. Although total fat was higher, that increase was accounted for by mono- and polyunsaturated fats. The amount of saturated fat was lower in Model 1 and not significantly higher in Model 2.

Table 9 shows the results for Addition Model 3, which added pistachios to existing diets of children (1–19 years) and adults (>19 y). The amounts of pistachios followed the Mexican Dietary Guidelines and ranged from 10 g of pistachios for children <4 y to 28 g for adults. Table 9 shows that the modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, MUFA and PUFA, and potassium and magnesium. Since this was addition modeling (as opposed to isocaloric substitution), calories increased, and the amounts of added sugars and sodium remained the same—i.e., addition of pistachios did not increase either added sugars or sodium in the modeled diet. Saturated fat was not significantly higher for children.

Table 9.

ENSANUT 2016. The observed and Model 3 (addition) diets of children (1–19 years) and adults (>19 y).

Figure 5 shows the reduction for children in added sugars (a) and sodium (b) and for adults in added sugar (c) and sodium (d) in ENSANUT 2016. Shown are data for observed diets and for Substitution Model 1 and Model 2 and the Addition Model 3.

Figure 5.

Changes in added sugars (a) and sodium (b) for children and added sugars (c) and sodium (d) for adults following isocaloric substitution and addition modeling (Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3) in ENSANUT 2016 by demographic variables. Data are shown separately for children and for adults.

Figure 6 shows how selected nutrient intakes in modeled ENSANUT 2016 diets changed following isocaloric substitution. There was an increase in protein, fiber, potassium, and magnesium, similar to the results obtained with modeling ENSANUT 2012.

Figure 6.

Nutrient intake changes in protein (a), fiber (b), potassium (c), and magnesium (d) content of modeled diets from original consumption by type of model: Model 1 (pistachios), Model 2 (mixed nuts), and Model 3 (adding 28 g). ENSANUT 2016.

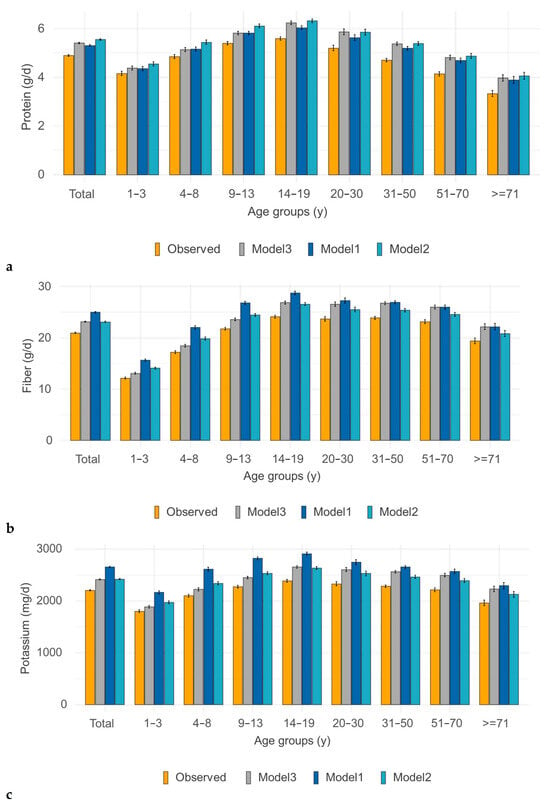

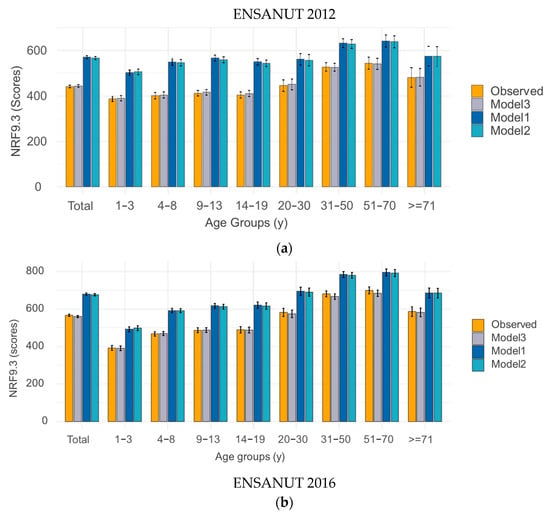

3.5. NRF 9.3 Measures of Modeled Dietary Nutrient Density: ENSANUT 2012 and 2016

The diet level NRF9.3 nutrient density scores for the observed and modeled diets are shown in Figure 7. The data are shown by age group for both children and adults. Separate analyses were conducted for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 databases.

Figure 7.

Nutrient-Rich Food Index (NRF9.3) by age group, (a) ENSANUT 2012 and (b) ENSANUT 2016. Model 1 (pistachios), Model 2 (mixed nuts), and Model 3 (adding 28 g).

To measure the total impact of the substitution models on diet quality, the NRF9.3 was examined (see Figure 7). Based on the observed diets for ENSANUT 2012, the population mean value was 441.41 (95% CI 435.03, 447.80). For both models, NRF9.3 mean values were significantly higher, 570.11 for Model 1 (pistachios) and 566.22 for Model 2 (mix). The value for Model 3 (adding 28 g) is 443.94. For all age groups, the NRF9.3 score was significantly higher in both Model 1 and Model 2 as compared to observed diets. The effect was particularly profound among children and adolescents. The values from Model 3 were not significantly different to the observed diets. The results of Model 1 tended to be modestly stronger than for Model 2, but not significantly different.

Similarly, the observed population mean diet value was 566.88 (95% CI 560.63, 573.14). For both models, NRF9.3 mean values were significantly higher, 679.77 for Model 1 (pistachios) and 677.26 for Model 2 (mixed nuts). The value for Model 3 (adding 28 g) is 679.77. As with the ENSANUT 2012 results, the NRF9.3 score for all age groups was significantly higher in both Model 1 and Model 2 as compared to observed diets. Again, the effect was particularly profound among children and adolescents, and the values from Model 3 were not significantly different to the observed diets. The results of Model 1 tended to be modestly stronger than for Model 2, but not significantly different.

The data clearly show significant improvements in diet quality that were achieved by replacing energy-dense foods (very high in added sugars) by pistachios and by mixed nuts and seeds. Greatest improvements were realized in diets of children and adolescents, suggesting that these groups would gain the most from replacing the usual snack foods with pistachios or with mixed nuts/seeds. Similar effects were obtained for ENSANUT 2012 and 2016. Adding small amounts of pistachios to the diet did not lead to modeled diets with more added sugars or sodium. The NRF9.3 scores were not significantly different.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The present analyses of ENSANUT 2012 and 2016 dietary intake data showed that energy-dense solid foods falling in the category of taxed snacks, provided 22.7% of energy in the diets of children and 16.5% in the diets of adults in 2013. By 2016 those percentages were reduced to 19.6% for children and 13.4% for adults. There were also reductions in added sugars from 2012 to 2016: from 14.4% of energy to 13.3% for children and from 12.9% to 12.3% for adults. Sodium intakes remained above 2000 mg/day.

Substitution modeling analyses replaced energy-dense foods with isocaloric amounts of pistachios or mixed nuts/seeds. Modeled diets with pistachios and mixed nuts/seeds were much lower in added sugars (down to <8% of dietary energy) and lower in sodium (<550 mg/day). These improvements were significant for children and adults and held across socio-demographic groups. Diets of children and adolescents were improved the most.

The modeled diets were higher in protein, fiber, mono- and polyunsaturated fats, and potassium and magnesium (p < 0.05). These improvements were significant for children and for adults and held across all socio-demographic strata. We did not find a decrease in vitamin C or calcium, since beverages (juice and milk) were not replaced in substitution analyses. On the other hand, Models 1 and 2 (but not Model 3) had less vitamin A. The major sources of vitamin A in Mexico are fortified milk and red and orange vegetables.

Overall diet quality, assessed using the NRF9.3 nutrient density score, was improved across all age groups with the greatest benefits observed for children and for young adults. Similar results were obtained when snacks were replaced with mixed nuts, mostly peanuts and seeds; however, the results for pistachios were stronger.

Adding small amounts of pistachios (from 10 g to 28 g) to the diet (Model 3) also led to higher quality diets as indicated by higher NRF9.3 scores. The additions (no longer isocaloric) were guided by the Mexican dietary guidelines. Even small amounts of pistachios improved diet quality without adding any sugar or sodium.

4.2. Pistachios in the Context of the Excise Tax

In January 2014, Mexico implemented an 8% excise tax on non-essential energy-dense foods (NEDFs)—defined as packaged products containing at least 275 kcal per 100 g, such as snacks, cookies, candies, and ice cream [,]. The goal was to avoid excess calories, and excess dietary fat, sugar, and salt. The taxed energy-dense snacks also included salted tree nuts, packaged and sold as snacks. Yet unsalted tree nuts including pistachios, are a desirable high-quality snack. They are unique in being both energy-dense and nutrient-rich.

The present analyses provide evidence to support the position that pistachios are a healthy snack that could be used to improve dietary quality overall. Indeed, pistachios could be considered an “essential food” based on Mexico Dietary Guidelines, EAT-Lancet recommendations, and approved health claims. Our modeled diets indicate that pistachios could become a source of macro- and micronutrients that could be incorporated into public food programs. Further investigation is needed to determine the economic accessibility of pistachios, which is traditionally thought to be expensive. Pistachios are good candidates for consumption as minimally processed dried oilseeds with lower probability of generating allergic reactions, compared to peanuts which are widely available and consumed in Mexico [].

4.3. Observed Improvements in the ENSANUT Diets Between 2012 and 2016

The overall quality of diets in Mexico improved between 2012 and 2016. There was a decline in energy intakes from energy-dense foods that was observed among both children and adults. Percent energy from added sugars declined as well. There was less of a socioeconomic gradient in diet quality, suggesting fewer social disparities in access to sufficient dietary energy and to recommended nutrients. Whether this was directly related to the excise tax is hard to determine. Other studies suggest that in the first year after implementation, purchases of taxed foods dropped by about 5.1% per person per month []. However, no changes were observed in rural areas, suggesting the tax’s impact is weaker outside urban centers []. The present data point to an interesting finding—by 2016 higher consumption of energy-dense snack foods was now associated with lower incomes and rural residence.

4.4. What Are the Implications for Public Health Policy?

As of early 2025, Mexico has banned the sale of any products with warning labels in schools, including many taxed items []. The warning-label system (black stop-sign seals for high-calorie, sugar, fat, and sodium content) continues to be phased in.

However, the Mexican policy is to promote the consumption of nuts and seeds that are both energy-dense and nutrient-rich. The Mexican general guidelines for the sale of foods in schools, launched in 30 September 2024 [], which include a table listing the diverse foods allowed in schools: desserts made from seeds and/or whole grains (without added fat or sugar) such as natural popcorn, amaranth dulce de leche (with minimal added sugar), mixed nuts, walnuts, almonds, cranberries, or prunes and snacks made from natural seeds (without salt and without frying) such as peanuts, dehydrated beans and lentils, and pumpkin seeds. The Health Department is preparing to implement the Mexican Dietary Guidelines to further promote the consumption of recommended food groups, including nuts and seeds.

Nuts and seeds are recommended by dietary guidelines in multiple countries [], including US and Mexico. This has implications for public health guidance and for public health policy. First, nuts and seeds are recommended by all dietary guidelines, including US and Mexico. Tree nuts are high in protein, fiber, and healthy fats and are reported to have positive effects on health []. In this study we specifically show that pistachios (unlike typical sweet or salty snacks) have zero added sugars and little sodium. They are also high in protein, fiber, and healthy fats. Tree nuts, including pistachios, belong with healthy snacks and, in terms of Mexican policies, are already viewed as an essential component of a healthy diet.

On the other hand, taxation on food and non-alcoholic beverages are employed to promote healthier diets and combat the high prevalences of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases. The evidence shows that in different countries, the taxation of high-fat, salt, or sugar foods had an effect on decreasing their sales, or purchases, and intakes []. Mexico is a pioneer in Latin America in implementing these types of policies, finding a positive effect in reducing purchases and consumption of these energy-dense foods. Despite these positive results, another simulation study suggests that these taxes could be higher to further contribute to reducing the prevalence of obesity []. If the tax on these foods is higher and larger quantities of them are replaced with nuts and seeds, as well as other healthy foods, it could contribute more quickly to reducing obesity. Helping to include this food group in the daily diet by improving access would have public health benefits.

4.5. Limitations

The study had limitations. The semi-quantitative FFQ is a relatively crude tool for assessing habitual diets; however, it is useful for providing snapshots of dietary intakes for large and representative populations. Self-reported dietary intakes suffer from under-reporting and bias. The energy-dense foods, falling into the taxed snacks category, were not necessarily eaten as snacks. Unlike 24 h dietary recalls, FFQ instruments do not capture information about mealtimes and the temporal distribution of intakes. Even though the identified foods were of high energy density and contained added sugars and sodium, specific excise taxes may have varied within product categories. As a result, the present comparison is between energy-dense foods, many falling into the category of non-essential taxed snacks, and pistachios and mixed nuts/seeds. Even though solid energy-dense snacks were replaced with solid energy-dense pistachios, substitution modeling does not take consumer attitudes or individual food preferences into account. Nutrient density analyses were based on the available nutrients; there were no data on other phytochemicals that are present in pistachios and tree nuts. Further investigation is needed on the nutrient quality of pistachios as compared to other competing healthy snacks. Finally, the most recent available ENSANUT data were for 2016; more recent data are expected to become available shortly. Future studies are needed to document the barriers to higher pistachio and walnut consumption, not just the economic ones, and to investigate whether there are differences by population group or some other characteristic. We need to replicate the analyses with more recent dietary data and compare the results with different dietary information collection instruments (frequency of consumption vs. 24-h recall).

5. Conclusions

Dietary guidelines in Mexico are moving toward the acceptance of tree nuts as valuable components of a healthy diet. Recommendations for schools already include mixed nuts (walnuts, almond), dried fruits, (cranberries or prunes), peanuts and pumpkin seeds (without salt or fat), and pulses. There is every reason to include pistachios and mixed nuts and seeds on the list of recommended healthy snacks with a potential to improve the quality of the overall diet. A diet based on dietary guidelines, which include nuts and seeds, is necessary to meet the requirements of various vitamins and minerals of the different age groups. Replacing the energy from ultra-processed foods with that from nuts and seeds is a dual-purpose alternative, as it would reduce the consumption of critical nutrients such as sugar, sodium, and added fats and improve the vitamin and mineral profile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.V. and A.D.; Data curation, S.R.-R.; Formal analysis, A.M.V. and S.R.-R.; Funding acquisition, A.D.; Investigation, S.R.-R. and M.C.M.-Z.; Methodology, A.M.V., S.R.-R., A.E.P.G., M.C.M.-Z. and A.D.; Project administration, A.M.V. and A.D.; Resources, A.M.V. and A.D.; Software, L.M.M.; Supervision, A.M.V. and A.D.; Validation, A.M.V., S.R.-R., A.E.P.G. and M.C.M.-Z.; Visualization, L.M.M.; Writing—original draft, A.D.; Writing—review and editing, A.M.V., S.R.-R. and A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from American Pistachio Growers grants to the Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla (UPAEP) (06142024) and the University of Washington.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data is described in the following: ISSN 0036-3634 and doi:10.21149/8593. The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

A.M.V., A.P.G. and L.M.M. are with UPAEP and UDLAP and have no conflict of interest to declare. S.R.-R. and M.C.M.-Z. are with the National Institute of Public Health of Mexico and have no conflict of interest to declare. A.D. is the original developer of the Naturally Nutrient-Rich (NNR) and the Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) nutrient profiling models and is or has been a member of scientific advisory panels for BEL, Lesaffre, Nestlé, FrieslandCampina Institute, National Pork Board, and Carbohydrate Quality Panel supported by Potatoes USA. A.D. has worked with Ajinomoto, Ayanabio, FoodMinds, KraftHeinz, Lesaffre, Meiji, MS-Nutrition, Nutrition Impact LLC, Nutrition Institute, PepsiCo, Samsung, and Soremantec on quantitative ways to assess nutrient density of foods. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Higgs, J.; Styles, K.; Carughi, A.; Roussell, M.A.; Bellisle, F.; Elsner, W.; Li, Z. Plant-Based Snacking: Research and Practical Applications of Pistachios for Health Benefits. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Hernández-Alonso, P.; Jenkins, D.J.; Kendall, C.W.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Nut Consumption and Type 2 Diabetes Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, L.; Neag, E.; Cadar, O.; Kovacs, M.H.; Becze, A.; Senila, M. Chemical, Nutritional and Antioxidant Characteristics of Different Food Seeds. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijssen, K.M.R.; Chavez-Alfaro, M.A.; Joris, P.J.; Plat, J.; Mensink, R.P. Effects of Longer-Term Mixed Nut Consumption on Lipoprotein Particle Concentrations in Older Adults with Overweight or Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Pons, C.; Sala-Vila, A.; Cofán, M.; Serra-Mir, M.; Roth, I.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Domènech, M.; Ortega, E.; Rajaram, S.; Sabaté, J.; et al. Effects of Walnut Consumption for 2 Years on Older Adults’ Bone Health in the Walnuts and Healthy Aging (WAHA) Trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Mataix, J. Fatty Acid Composition of Nuts—Implications for Cardiovascular Health. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnesen, E.K.; Thorisdottir, B.; Bärebring, L.; Söderlund, F.; Nwaru, B.I.; Spielau, U.; Dierkes, J.; Ramel, A.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Åkesson, A. Nuts and Seeds Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Type 2 Diabetes and Their Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67, 10-29219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Li, J.; Hu, F.B.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Tobias, D.K. Effects of Walnut Consumption on Blood Lipids and Other Cardiovascular Risk Factors: An Updated Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Neyman, S.M.; Zohoori, N.; Broughton, K.S.; Miketinas, D.C. Association of Tree Nut Consumption with Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Health Outcomes in US Adults: NHANES 2011–2018. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 102007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- SSA; INSP; GISAMAC; UNICEF. 2023 Guías Alimentarias Saludables y Sostenibles Para La Población Mexicana; SSA: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara de Diputados del, H. Congreso de la Unión Ley Del Impuesto Especial Sobre Producción y Servicios; Cámara de Diputados: Mexico City, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-F, M.; Batis, C.; Rivera, J.A.; Colchero, M.A. Reduction in Purchases of Energy-Dense Nutrient-Poor Foods in Mexico Associated with the Introduction of a Tax in 2014. Prev. Med. 2019, 118, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colchero, M.A.; Zavala, J.A.; Batis, C.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Cambios En Los Precios de Bebidas y Alimentos Con Impuesto En Áreas Rurales y Semirrurales de México. Salud Pública México 2017, 59, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. The Nutrient Rich Foods Index Helps to Identify Healthy, Affordable Foods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1095S–1101S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, M.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Franco-Núñez, A.; Villalpando, S.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Gutiérrez, J.P.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.Á. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2012: Diseño y cobertura. Salud Pública México 2013, 55, S332–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, M.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Méndez Gómez-Humarán, I.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.Á.; Hernández-Ávila, M. Diseño Metodológico de La Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición de Medio Camino 2016. Salud Pública México 2017, 59, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Ramírez-Silva, I.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Jiménez-Aguilar, A.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Validity of a Food Frequency Questionnaire to Assess Food Intake in Mexican Adolescent and Adult Population. Salud Pública México 2016, 58, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, V.; Huang, H.J.; Akarsu, A.; Shilovskiy, I.; Elisyutina, O.; Khaitov, M.; Van Hage, M.; Linhart, B.; Focke-Tejkl, M.; Valenta, R.; et al. From allergen molecules to molecular immunotherapy of nut allergy: A hard nut to crack. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 742732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogbe, W.; Akaichi, F.; Rungapamestry, V.; Revoredo-Giha, C. Effectiveness of Implemented Global Dietary Interventions: A Scoping Review of Fiscal Policies. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Federal para la Protección contra Riesgos Sanitarios Modificación a la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM 051 SCFI SSA1. 2010. Available online: http://www.gob.mx/cofepris/acciones-y-programas/manual-de-la-modificacion-a-la-norma-oficial-mexicana-nom-051-scfi-ssa1-2010-272744?state=published (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Diario Oficial de la Federación Lineamientos Para La Preparación, Distribución y Expendio de Alimentos y Bebidas Dentro de Toda Escuela Del Sistema Educativo Nacional. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5740005&fecha=30/09/2024#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Cámara, M.; Giner, R.M.; González-Fandos, E.; López-García, E.; Mañes, J.; Portillo, M.P.; Rafecas, M.; Domínguez, L.; Martínez, J.A. Food-based dietary guidelines around the world: A comparative analysis to update AESAN scientific committee dietary recommendations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polmann, G.; Badia, V.; Danielski, R.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Block, J.M. Nuts and nut-based products: A meta-analysis from intake health benefits and functional characteristics from recovered constituents. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 5021–5047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, E.; Gressier, M.; Li, D.; Brown, T.; Mounsey, S.; Olney, J.; Sassi, F. Effectiveness and policy implications of health taxes on foods high in fat, salt, and sugar. Food Policy 2024, 123, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junquera-Badilla, I.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Reyes-García, A.; Colchero, M.A.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. Expected benefits of increasing taxes to nonessential energy-dense foods in Mexico: A modeling study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).