Abstract

Background: Energy drink [ED] consumption is common among young adults and has been linked to adverse health effects and risky behaviors. This study compared medical and non-medical university students to assess whether health education influences knowledge, consumption, and attitudes toward EDs. Although medical and non-medical students are not minors, their opinions on the national ban on EDs sales to individuals under 18 provide valuable insight into attitudes toward regulation. Material and Methods: A cross-sectional online survey was conducted among 871 students (42.1% medical, 57.9% non-medical). The questionnaire assessed demographics, ED consumption, knowledge, motivations, and regulatory attitudes. It was pilot-tested on 30 students to ensure clarity, and internal consistency was confirmed (Cronbach’s α = 0.78 for knowledge; α = 0.81 for attitudes). Non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U, Kruskal–Wallis) and chi-square analyses compared groups. Results: Participants’ mean age was 22.1 years; most were female (73.2%). Medical students demonstrated significantly better knowledge of ED ingredients (simple sugars, B vitamins, L-carnitine, electrolytes; p < 0.01) and adverse effects (e.g., irritability, dizziness, nausea; p < 0.05). However, ED consumption frequency did not differ between medical and non-medical students. The main reasons for ED use were energy and concentration; social motives were less frequent. Female students more often supported the ban on ED sales to minors and additional advertising restrictions (p < 0.001), while overall confidence in enforcement was low. Conclusions: Despite greater awareness, medical students consume EDs at rates comparable to non-medical students. Educating medical students on safe caffeine use is crucial, since shift work may promote stimulant intake. Combining targeted education with stronger enforcement could enhance the impact of regulatory policies and reduce risky consumption among young adults.

1. Introduction

Over the past three decades, energy drinks [EDs] have become one of the fastest growing segments of the global beverage market. Their wide availability and intensive marketing have made them particularly popular among adolescents and young adults, who now represent the largest consumer group [1,2,3,4]. EDs are increasingly recognized as a public health concern due to their growing consumption among young people worldwide [5].

EDs are widely consumed by young people. Their use often begins in adolescence and is more prevalent among males and physically active individuals. It is frequently associated with behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use, as well as adverse health effects including palpitations, whereas marketing campaigns tend to emphasize supposed improvements in cognition and performance benefits while underestimating associated risks [6,7,8].

ED consumption is associated with lifestyle factors and irregular dietary behaviors, with sociodemographic characteristics including male gender, unmarried status, and enrollment in non-medical fields of study [9,10,11]. Students facing intensive academic demands may also rely on EDs to cope with fatigue and maintain alertness, despite their association with adverse health outcomes including sleep problems, migraines, and cardiovascular complications [12]. Among university students, knowledge of these products is often limited, attitudes remain ambivalent, and reported motives for use include prolonging wakefulness, enhancing study capacity, and increasing energy levels [13].

Medical students may differ from non-medical students in both their knowledge of ED ingredients and their attitudes toward potential health risks, indicating that the field of study could influence patterns of use and perceptions [11,12,13]. Although EDs are often consumed by students to improve concentration and academic performance, the scientific evidence for such benefits is weak, and growing concerns highlight their potential negative consequences for mental health and overall well-being, reinforcing the need for further research [6,14]. Research among university students has shown that ED use is shaped not only by individual motives and perceived benefits but also by social influences, misinformation about product content, and the easy accessibility of these beverages [15]. High rates of ED use have also been observed among medical students, with study-related demands and the need for energy as the main motives, and mass media and peers serving as key sources of information [16].

Recent evidence from Poland shows that while public awareness of the health risks associated with EDs is relatively high and support for age-related sales restrictions is strong, many individuals doubt the effectiveness of such measures in limiting access among minors [4]. In response to these concerns, Poland has introduced nationwide regulations governing the sale and distribution of EDs. A key step was the 2023 amendment to the Public Health Act, which came into force on 1 January 2024. Under this law, the sale of EDs to individuals under 18 years of age is prohibited, and their distribution is banned in schools as well as through vending machines. Retailers are authorized to request proof of age when necessary. The Act also provides an official definition of an “energy drink” and requires clear product labeling, aiming to support consumer awareness and facilitate enforcement. However, despite this legal framework, questions remain regarding the effectiveness of enforcement measures and the actual availability of EDs to minors [3,17].

The study aimed to assess ED consumption and related attitudes among students in the Mazovia region of Poland. Specifically, the objectives were to examine (1) the frequency and motives of ED use, (2) students’ knowledge of their health effects, and (3) opinions regarding the recently introduced sales ban and the potential need for additional restrictions, with a particular focus on differences between medical and non-medical students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire and Study Measures

This cross-sectional survey was conducted among university students, including both medical and non-medical faculties, in the Mazovia region of Poland between 1 and 20 July 2025. Medical students were selected as a key group because, as future healthcare professionals, they are exposed to high academic demands, stress, and irregular schedules that may predispose them to stimulant use. Data were collected using an anonymous online questionnaire distributed via multiple social media platforms, including student forums and university groups. Participation in the study was voluntary and preceded by informed consent obtained electronically after participants read a statement outlining the study aims, anonymity, and their right to withdraw at any time. Eligibility criteria included being enrolled as a student at a higher education institution located in Mazovia at the time of the study. The questionnaire included sections on sociodemographic characteristics, consumption patterns of ED, knowledge of their composition and potential adverse effects, and attitudes toward legal regulations concerning these products. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland (decision number AKBE/139/2025).

The study used an author-developed questionnaire designed based on a review of previous surveys investigating energy drink consumption, motivations for use, and regulatory attitudes [4,5,9,11,13]. Although informed by prior research, the instrument was original and tailored to the Polish context, including new items addressing the awareness of the recent national ban on energy drink sales to minors. It comprised sections on sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, consumption behaviors, and attitudes toward legal regulations concerning EDs. Content validity was verified by three academic experts in public health prior to pilot testing. Prior to data collection, the questionnaire was pilot-tested on 30 students not included in the final sample to assess clarity and completion time. Minor modifications were made to improve comprehensibility. Internal consistency of the main multi-item sections was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which showed satisfactory reliability (knowledge α = 0.78; attitudes α = 0.81). Knowledge of ED was assessed through questions regarding awareness of specific ingredients (e.g., caffeine, taurine, guarana, simple sugars, B vitamins, L-carnitine, electrolytes) and potential adverse health effects (e.g., irritability, nausea, dizziness, sleep problems, increased blood pressure, impaired coordination). Consumption behaviors were measured by asking whether respondents had ever consumed EDs, the age of initiation, frequency of consumption, and whether they combined EDs with other substances such as alcohol, coffee, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, dietary supplements, or psychoactive substances. Additional questions concerned the reasons for consumption, including motivation related to studying, concentration, energy boost, leisure activities, or social situations. Attitudes toward legal regulations were assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = definitely not, 5 = definitely yes). Respondents were asked whether they supported the national ban on the sale of EDs to individuals under 18, whether they perceived the ban as effective in reducing availability, and whether they supported additional restrictions such as advertising limitations. For some analyses, answers “definitely yes” and “mostly yes” were combined to indicate agreement. Sociodemographic data included gender (female, male, other, prefer not to answer), age (years), place of residence (rural area, town ≤ 20,000 residents, city 20,000–99,999 residents, city 100,000–499,999 residents, city ≥ 500,000 residents), type and year of study program (bachelor, master, integrated master’s), mode of study (full-time, part-time), and self-assessed financial situation (very good, good, moderate, poor, very poor). The selected sociodemographic variables are commonly included in studies examining energy drink consumption and related behaviors, which allows for meaningful comparison with previous findings.

2.2. Sample Size and Recruitment

Recruitment followed a convenience sampling approach, with open access to the online survey link. Although non-random sampling may lead to self-selection bias, efforts were made to minimize this risk by disseminating the survey widely across various student groups representing different fields of study. A minimum required sample size was estimated using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) for the chi-square test (medium effect size, α = 0.05, power = 0.80), indicating a threshold of 384 participants [18]. The final sample of 871 students substantially exceeded this number, ensuring adequate statistical power.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, which indicated the need for non-parametric methods for several variables. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and presented as means with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables and as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. To examine differences between medical and non-medical students, as well as across sociodemographic groups, non-parametric tests were applied. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups (e.g., male vs. female students), while the Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc pairwise comparisons was applied for comparisons across more than two groups (e.g., place of residence). The median test was additionally employed to assess differences in central tendency. Associations between categorical variables were examined using chi-square (χ2) tests of independence. Binary logistic regression models were applied to identify sociodemographic predictors of knowledge, consumption, and attitudes toward ED regulations. The enter method was used, and multicollinearity was checked with variance inflation factors (VIF < 2). Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For all analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

The study sample consisted of 871 university students, including 367 (42.1%) medical students and 504 (57.9%) non-medical students. The mean age was 22.1 years (SD = 3.05; range: 18–45). Most respondents were female (73.2%, n = 638), while 25.3% (n = 220) identified as male; 0.8% (n = 7) reported “other,” and 0.7% (n = 6) preferred not to disclose their gender. The majority of participants resided in very large cities (>500,000 inhabitants, 66.8%). Smaller shares lived in rural areas (10.2%), small towns of up to 20,000 inhabitants (5.4%), medium-sized cities of 20,000–100,000 (10.9%), and large cities of 100,000–500,000 (6.7%). In terms of financial situation, 28.7% described their household status as very good, 59.4% as good, 9.9% as moderate, and 2.1% as poor or very poor. Regarding education, 37.7% of students were pursuing bachelor’s studies, 21.2% master’s studies, and 41.1% integrated master’s programs. Most were full-time students (85.3%), with the remainder studying part-time (14.7%). Distribution by year of study was as follows: first year 23.1%, second year 26.1%, third year 23.0%, fourth year 15.6%, fifth year 9.4%, and sixth year 2.9%. Detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the study population, including age, gender, field of study, and place of residence, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group.

3.2. Frequency and Patterns of Energy Drinks Consumption

Overall, 75.2% of university students reported consuming EDs at least occasionally, while 24.8% indicated that they never consumed them. The most common frequencies of consumption were 2–3 times per week 14.2%, once per month 13.9%, and less than once every three months 14.5%. Daily or almost daily intake was reported by 9.2% of respondents. When comparing fields of study, 75.8% of medical students and 73.2% of non-medical students reported ED use. This difference was not statistically significant. The frequency of ED consumption did not differ significantly between medical and non-medical students. Gender-based comparisons showed that male students reported significantly more frequent ED consumption than females (p < 0.05).

Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the co-consumption of EDs with alcohol, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, dietary supplements, or psychoactive substances. However, medical students reported combining EDs with coffee more frequently than non-medical students (16.6% vs. 10.7%; χ2 = 6.47; p = 0.011). Most students reported first trying energy drinks between the ages of 15 and 18 years (37.7%), while nearly one-third (29.8%) consumed them before the age of 15. Among medical students, 41.4% first consumed energy drinks between ages 15–18 and 42.0% before 15, compared with 58.6% and 58.0% among non-medical students, respectively. Non-medical students thus tended to start slightly earlier, though the difference was not statistically significant.

3.3. Motivations for Consumption of Energy Drinks

The most common motivations for energy drink (ED) consumption were increased energy (63.1%), improved concentration while studying (37.3%), and taste (37.4%), followed by using EDs as a coffee substitute (32.0%). Statistical analysis (Mann–Whitney U test with continuity correction) revealed that medical students more frequently reported energy enhancement (Z = 2.48; p = 0.013) and improved concentration (Z = 4.69; p < 0.001) as reasons for ED use compared with non-medical students. No significant differences were found for leisure or socially driven motives, such as peer pressure.

3.4. Knowledge About Energy Drinks

When asked about the safe daily dose of caffeine for healthy adults, only 31.3% of students correctly identified the recommended limit of 400 mg. A further 25.4% indicated 200 mg, and 8.1% selected 100 mg, while 35.3% declared that they did not know the correct answer. Regarding caffeine content, medical students significantly more often selected the correct value referring to the maximum recommended daily intake of caffeine for adults (400 mg) compared to non-medical students (p < 0.001).

Comparisons between medical and non-medical students revealed significant differences in knowledge of certain ED ingredients. Medical students were more likely to correctly identify simple sugars, B vitamins, L-carnitine, and electrolytes (p < 0.01). No significant differences were observed for caffeine, taurine, guarana, ginseng, or artificial colorants.

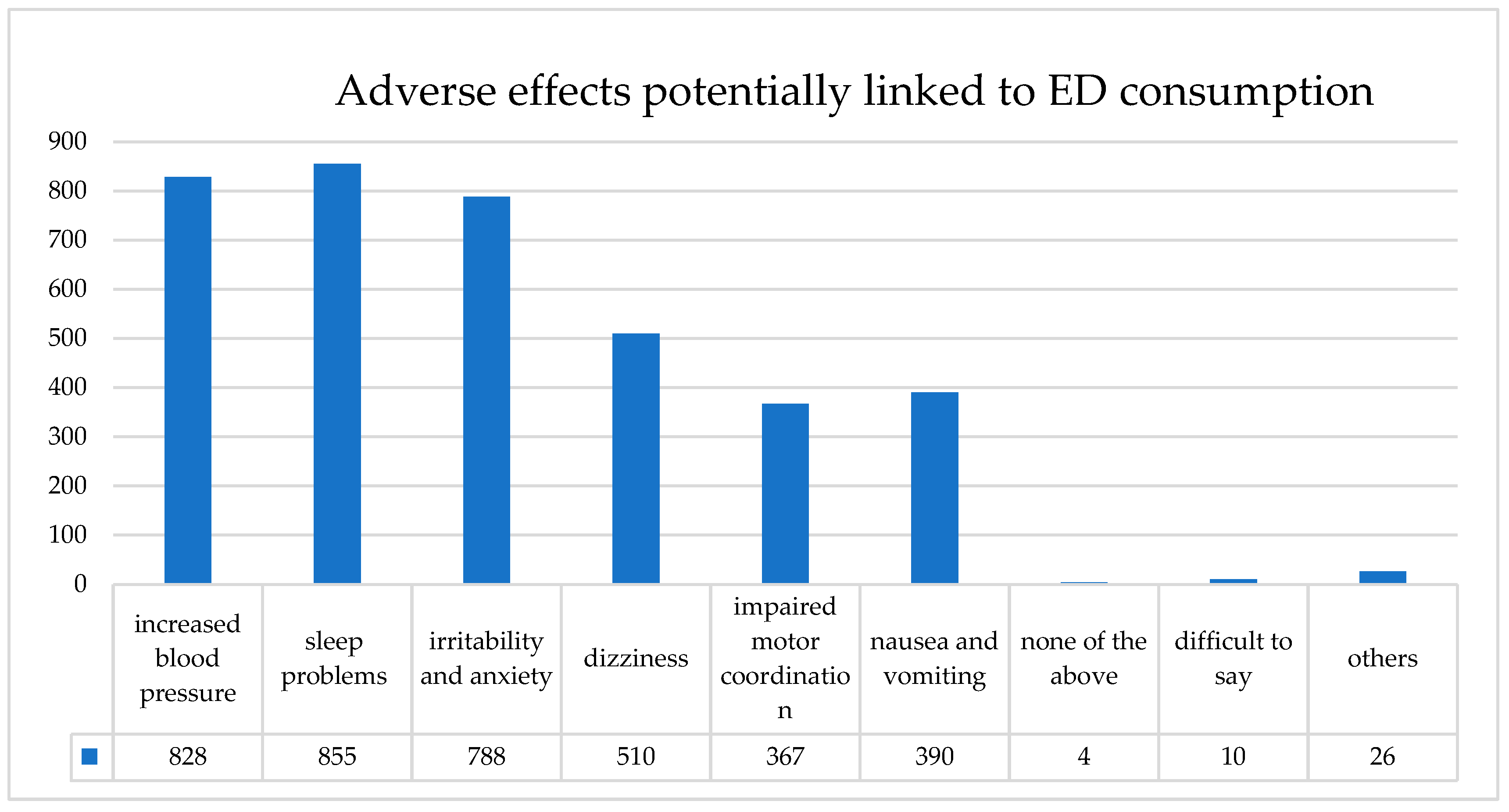

Moreover, medical students demonstrated greater awareness of adverse effects of ED consumption, including irritability, dizziness, nausea, and impaired coordination (p < 0.05). The most frequently reported adverse effects among all respondents were sleep problems (98.2%), increased blood pressure (95.1%), and irritability and anxiety (90.4%), followed by dizziness (58.5%), nausea and vomiting (44.8%), and impaired motor coordination (42.1%) (Figure 1). No significant differences were noted for increased blood pressure or sleep problems.

Figure 1.

Self-reported adverse effects potentially associated with ED consumption among university students (n = 871). The most frequently indicated effects were sleep problems (98.2%), increased blood pressure (95.1%), and irritability and anxiety (90.4%) (multiple responses possible).

3.5. Attitudes Toward Energy Drink Regulations and Sociodemographic Differences

Support for the legal ban on the sale of EDs to minors was high in both study groups. Gender was significantly associated with regulatory attitudes: female students were more likely than male students to support the ban (U = 53,143.5; Z = 6.09; p < 0.001) and to endorse additional restrictions such as advertising limitations (U = 47,437.5; Z = 7.40; p < 0.001). However, no significant gender differences were observed in perceptions of the ban’s effectiveness in reducing minors’ access to EDs (p = 0.81).

Place of residence was not significantly associated with support for the ban (H(4, n = 871) = 4.16; p = 0.385; χ2 = 0.00; p = 1.000) or with perceptions of its effectiveness (H(4, n = 871) = 7.74; p = 0.102; χ2 = 4.88; p = 0.300). Nonetheless, pairwise comparisons indicated that students from rural areas were more supportive of additional restrictions compared to those from small towns (p = 0.017) and large cities (p = 0.039).

Other sociodemographic variables, including year and type of study program, financial situation, and study mode (full-time vs. part-time), were not significantly associated with attitudes toward EDs regulations. The comparison of attitudes by gender is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of attitudes toward ED regulations between female and male students.

4. Discussion

The findings indicate that medical students demonstrated higher awareness of ED ingredients and potential adverse effects than non-medical students, particularly with respect to caffeine, simple sugars, B vitamins, L-carnitine, and electrolytes, while knowledge about taurine, guarana, and ginseng remained similar across groups. It has been reported that while students generally acknowledge caffeine and sugar in EDs, their understanding of additional ingredients such as amino acids and B vitamins remains limited, including among those in medical fields [11,19].

A study among university students in Jordan showed that higher knowledge scores were associated with studying a medical major [13]. Likewise, evidence from Italy indicated that students of life sciences courses were more likely to be ED users and had greater awareness of their ingredients and related behaviors [9]. These results suggest that the field of study plays an important role in shaping the awareness of ED contents.

Analysis of consumption behaviors did not reveal significant differences between medical and non-medical students in terms of the frequency of ED use, nor in the co-consumption of these products with alcohol, cigarettes, or other psychoactive substances. The only distinction observed was a higher tendency among medical students to combine EDs with coffee, while the reported age of initiation was similar across groups. Comparable findings were reported in a Saudi study, where gender and field of study emerged as determinants of ED consumption, although not all behavioral aspects differed consistently between groups [11]. Likewise, research among Jordanian students has shown that although knowledge about EDs varies by academic discipline, actual consumption practices often remain similar, with motives such as staying awake or enhancing study performance prevailing across groups [13]. These results suggest that while medical education may increase awareness of potential risks, it does not necessarily translate into markedly different consumption patterns when compared to non-medical peers.

In the present study, medical students were more likely to indicate energy and concentration as primary motives for consuming EDs, whereas leisure and socially driven motives did not differ significantly between groups, suggesting similar behavioral patterns in this domain. Similar patterns have been observed in other research, where study-related demands were identified as a predominant reason for ED consumption among medical students [7].

Among the analyzed sociodemographic variables, gender emerged as the strongest factor differentiating attitudes toward regulation, whereas other factors such as year and mode of study or financial situation were not of significant importance. Similar findings were reported in previous studies, where gender emerged as a key determinant of ED use and related attitudes, while other sociodemographic variables such as academic year or financial status showed weaker associations [20,21,22,23,24,25].

A high level of support for the ban on the sale of EDs to individuals under the age of 18 was observed in both groups. However, sociodemographic analysis revealed gender differences. Female students were more likely than males to support the ban as well as additional restrictions, such as advertising limitations. With regard to the perceived effectiveness of the ban, no significant differences were noted by gender or place of residence. Nevertheless, a more detailed analysis indicated that students from rural areas expressed stronger support for additional restrictions compared to those living in small and large cities. Similar gender-based differences were reported in a recent nationally representative study of adults in Poland, where women were significantly more likely than men to perceive EDs as harmful to health (85.6% vs. 80.1%; p = 0.02), to support the sales ban to minors (89.5% vs. 84.4%; p = 0.01), and to endorse additional restrictions such as advertising bans (74.4% vs. 61.9%; p < 0.001). These findings are consistent with the results of the present study, suggesting that gender-related differences in attitudes towards EDs regulation extend beyond student populations and may reflect broader societal patterns [4].

The observed patterns of ED use among future health professionals highlight the importance of addressing potentially unhealthy consumption habits early in training and integrating targeted health education to promote safer behaviors [26]. Given the evidence linking ED use among nurses to poorer sleep quality, reduced sleep duration, and higher stress levels, it is particularly important to monitor and address ED consumption among medical students, as their future professional roles in demanding clinical environments may predispose them to increased intake of these beverages [27,28,29]. Moreover, greater attention from policymakers is needed to strengthen regulations on the advertising of EDs and other high-caffeine beverages, to which adolescents and young adults including future healthcare providers are widely exposed. Increasing knowledge about EDs and their possible risks could also decrease their consumption by the general public, further supporting preventive efforts [30,31]. Other research has also shown that medical students tend to demonstrate better knowledge of energy drink ingredients compared with non-medical students, yet this awareness does not necessarily translate into lower consumption [32,33]. Awareness campaigns and educational programs targeting both medical and non-medical students could help improve understanding of energy drink ingredients, associated risks, and safe consumption practices [34]. Increasing knowledge about how excessive ED use can affect concentration, sleep, and overall well-being may help promote healthier study habits and reduce reliance on stimulants during academic activities [35]. The findings of this study emphasize the importance of addressing energy drink use within medical education. As future healthcare professionals, medical students will be responsible for counseling patients on healthy lifestyle behaviors, including the risks of caffeine-containing beverages.

Limitations

Given the cross-sectional design, findings reflect associations and do not allow causal inference. The use of self-reported data may introduce recall bias and social desirability bias. Moreover, convenience sampling via social media may limit generalizability, as students more engaged online could be overrepresented. These limitations were partially mitigated through pilot testing of the tool, reliability checks, wide distribution across diverse study groups, and an adequately powered sample size. In addition, the presented group may not fully reflect the structure of the academic population in Poland. Women were overrepresented in the sample (approximately 74%) compared to national statistics, where they constitute around 58% of students according to Statistics Poland (GUS) [36]. This imbalance may partly reflect a greater willingness of female students to participate in surveys.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that although medical students are more aware of ED ingredients and risks, their consumption patterns remain similar to non-medical students. Energy and concentration remain the main reasons for use, while social motives are less common. Students widely support the ban on sales to minors but doubt its effective enforcement; gender differences most strongly shape regulatory attitudes. These findings highlight the need to complement legislation with targeted health education, especially within medical curricula, as future shift-based work may increase stimulant use, and with effective monitoring to strengthen policy impact and reduce risky consumption among young adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.-T. and A.S.; methodology, P.M.-T. and A.S.; software, T.K.; validation, A.S., formal analysis, P.M.-T.; investigation, J.K. and E.A.; resources, J.K. and E.A.; data curation, T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.-T.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, T.K.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, P.M.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and by the Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Warsaw, Poland (decision number AKBE/139/2025, approval date 24 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study while collecting data via the CAWI method.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study will be available upon request from interested researchers. If the data cannot be made publicly available in a trusted repository, the reason for this will be specified in the Data Availability Statement. Further information and materials necessary for the reproduction of the experiment can be obtained by contacting the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nadeem, I.M.; Shanmugaraj, A.; Sakha, S.; Horner, N.S.; Ayeni, O.R.; Khan, M. Energy Drinks and Their Adverse Health Effects: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Health 2021, 13, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, K.R.; Svatikova, A. Cardiovascular and Autonomic Responses to Energy Drinks-Clinical Implications. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mularczyk-Tomczewska, P.; Gujski, M.; Koweszko, T.; Szulc, A.; Silczuk, A. Regulatory Efforts and Health Implications of Energy Drink Consumption by Minors in Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e947124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mularczyk-Tomczewska, P.; Lewandowska, A.; Kamińska, A.; Gałecka, M.; Atroszko, P.A.; Baran, T.; Koweszko, T.; Silczuk, A. Patterns of Energy Drink Use, Risk Perception, and Regulatory Attitudes in the Adult Polish Population: Results of a Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, J.L.; Munsell, C.R.; Harris, J.L. Energy drinks: An emerging public health hazard for youth. J. Public Health Policy 2013, 34, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira Batista, D.R.; CSilva, K.V.; Torres, M.; Pires da Costa, W.; Monfort-Pañego, M.E.; Silva, P.R.; Noll, M. Effects of energy drinks on mental health and academic performance of university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussabekova, Z.; Tukinova, A. Consumption of energy drinks among medical university students in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2024, 36, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlu, A.; Oral, B.; Gunay, O. Consumption of energy drinks among Turkish University students and its health hazards. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protano, C.; Valeriani, F.; De Giorgi, A.; Angelillo, S.; Bargellini, A.; Bianco, A.; Bianco, L.; Caggiano, G.; Colucci, M.E.; Coniglio, M.A.; et al. Consumption of Energy Drinks among Italian University students: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, S.; Kawasaki, H.; Cui, Z. Use of Caffeine-Containing Energy Drinks by Japanese Middle School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study of Related Factors. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, A.; Alabbad, M.H.; AlMussalam, M.Z.; AlMusalmi, A.M.; Alealiwi, M.M.; Alresasy, A.; Alyaseen, H.N. Determinants of energy drinks consumption among the students of a Saudi University. J. Fam. Community Med. 2019, 26, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyeneng, L.G.; Pilusa, M.L. Prevalence of fatigue and consumption of energy drinks consumption among nursing students studying part-time. Health SA 2024, 29, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiab, S.; Barakat, M.; Nassar, R.I.; Abutaima, R.; Alsughaier, A.; Thaher, R.; Odeh, F.; Abu Dayyih, W. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of energy drinks consumption among university students in Jordan. J. Nutr. Sci. 2023, 12, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalese, M.; Benedetti, E.; Cerrai, S.; Colasante, E.; Fortunato, L.; Molinaro, S. Alcohol versus combined alcohol and energy drinks consumption: Risk behaviors and consumption patterns among European students. Alcohol 2023, 110, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozayel, M.; Ghaddar, A.; Farhat, G.; Nasreddine, L.; Kara, J.; Jomaa, L. Energy drinks consumption and perceptions among University Students in Beirut, Lebanon: A mixed methods approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Bhombal, S.T.; Jawaid, A.; Zaki, S. Energy drinks consumption practices among medical students of a Private sector University of Karachi, Pakistan. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2015, 65, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ustawa z Dnia 11 Września 2015 r o Zdrowiu Publicznym (tj, Dz. U. z 2022 r. poz. 1608 z późn. zm.). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220001608 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasem, N.W.; Al-Omoush, O.M.; Al Ammouri, Z.M.; Alnobani, N.M.; Abdallah, M.M.; Khateeb, A.N.; Habash, M.H.; Hrout, R.A. Energy drink consumption among medical students in Jordan—prevalence, attitudes, and associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.K.; Kim, K.M. Energy drink consumption patterns and associated factors among nursing students: A descriptive survey study. J. Addict. Nurs. 2015, 26, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouja, C.; Kneale, D.; Brunton, G.; Raine, G.; Stansfield, C.; Sowden, A.; Sutcliffe, K.; Thomas, J. Consumption and effects of caffeinated energy drinks in young people: An overview of systematic reviews and secondary analysis of UK data to inform policy. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubcikova, J.; Kolarcik, P.; Madarasova Geckova, A.; Reijneveld, S.A.; van Dijk, J.P. Regular energy drink consumption is associated with the risk of health and behavioural problems in adolescents. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, N.S.; Pasch, K.E. Energy drink consumption is associated with unhealthy dietary behaviours among college youth. Perspect. Public Health 2015, 135, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R. Ban on sale of energy drinks to children. BMJ 2018, 362, k3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.L.; Munsell, C.R. Energy drinks and adolescents: What’s the harm? Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J. Influence of Psychosocial Factors on Energy Drink Consumption in Korean Nursing Students: Never-consumers versus Ever-consumers. Child. Health Nurs. Res. 2019, 25, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, M.R.; Chilton, J.M.; El-Saidi, M.; Duke, G.; Haas, B.K. Nurses Consuming Energy Drinks Report Poorer Sleep and Higher Stress. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 42, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, M.R.; Gipson, C.S.; El-Saidi, M. Caffeine Consumption Habits, Sleep Quality, Sleep Quantity, and Perceived Stress of Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nurse Educ. 2022, 47, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Yang, I.S. Korean nurses’ energy drink consumption and associated factors. Nurs. Health Sci. 2023, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, N.; Soliman, A.T.; Elsedfy, H.; Di Maio, S.; El Kholy, M.; Fiscina, B. Caffeinated energy drink consumption among adolescents and potential health consequences associated with their use: A significant public health hazard. Acta Biomed. 2017, 88, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaiea, G.M.; Altebainawi, A.F.; Alshammari, T.M. Energy drinks and population health: Consumption pattern and adverse effects among Saudi population. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrees, A.E.; Altalhi, T.M.; Al-Halabi, S.K.; Alshehri, H.A.; Altalhi, H.H.; Althagafi, A.M.; Koursan, S.M. Energy drink consumption among medical students of Taif University. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 3950–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Borle, A.L.; Mandal, I.; Arora, E.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, T.; Singh, M.; Baghel, S. Practices Towards Energy Drink Consumption Among the Students of a Medical College in New Delhi, India. Cureus 2025, 17, e79819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faqeeh, S.; Mansour, S.E.; Darwish, R.; Alhariri, N.; Alsebai, H.; Alkalbani, K.; A Saleh, M.; Hussein, A. Prevalence, Knowledge, and Attitudes of Energy Drink Consumption Among University Students in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e83073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.; Ali, H.; Jamil, D.; Ahmed, R.; Kalo, N.; Saeed, N.; Abdullah, G. Effects of Energy Drink Consumption on Specific Cardiovascular and Psycho-Behavioral Parameters Among Medical Students at the University of Zakho. Cureus 2024, 16, e67790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS). Higher Education in the Academic Year 2024/2025; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2025. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5488/8/11/1/szkolnictwo_wyzsze_w_roku_akademickim_2024-2025.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).