Highlights

- Flexitarian diets limit animal product consumption without eliminating them entirely.

- Flexitarian diets may be more feasible than strict vegetarian/vegan diets.

- Most food-based dietary guidance globally does not discuss flexitarian diets.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: A dietary pattern that simply reduces animal-based foods may be more acceptable to consumers than strict vegetarian or vegan diets. The objective of this investigation was to identify the most consistently used definitions of “flexitarian” dietary patterns, or dietary patterns with a reduced amount of animal foods. Then, sets of food-based dietary guidance (FBDG) from different countries and regions were evaluated to determine whether their guidance could accommodate flexitarian diets. Methods: Literature searches yielded 86 total results on flexitarian eating after screening by title/abstract, full text availability, and English language. Definitions of “flexitarian” were extracted from each article then reviewed and summarized. FBDGs available in English were downloaded from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website. Guidance related to reduced animal product diets was extracted from FBDGs for eating patterns closest to 2000 kcal. Results: The summary definition of flexitarian included eating at least one animal product (dairy, eggs, meat, or fish) at least once per month but less than once per week. FBDGs from n = 42 countries or regions were downloaded and data extracted. Only FBDG from Sri Lanka explicitly describe a “semi-vegetarian” eating pattern, though n = 12 FBDGs describe a vegetarian pattern and n = 14 recommend reducing meat or animal food and/or choosing meat/dairy alternatives. Conclusions: Following a flexitarian dietary pattern in terms of reducing or limiting red meat is feasible and even implicitly recommended by the official dietary guidance of several countries. Most FBDGs examined did not include recommendations to decrease dairy or fish intake.

1. Introduction

Despite a burgeoning interest in plant-based eating, few people adopt restrictive plant-based eating patterns such as vegetarian or vegan diets [1]. Consumer insights research indicates that, in 2024, more Americans reported following eating patterns with reduced animal foods than more strictly defined vegetarian or vegan diets [2]. While only 2% of consumers indicate that they follow vegan diets and 3% of consumers report following a vegetarian diet, 5% of American consumers followed “flexitarian” diets [2]. The reasons for following more plant-oriented dietary patterns varies, though most consumers (55%) follow these patterns to be healthier, because they enjoy plant-foods more (38%), or to improve animal welfare (33%) [2].

Including plant-based foods and reducing animal-based foods in the diet has also been a common topic in food based dietary guidance (FBDG) that addresses sustainability as a basis for diet recommendations [3]. The shift to recommending plant-based diets as an environmental mitigation strategy happened within the span of about 10 years. Several countries have introduced environmental sustainability into their FBDGs since 2010, when the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) released a report entitled “Sustainable diets and Biodiversity” [4]. This report noted that dietary changes were not frequently discussed in the climate change literature, and it recommended the global development and adoption of “sustainable diets” [4]. Accordingly, by 2016, an updated FAO report indicated that four countries explicitly discussed environmental sustainability in their official FBDGs (Brazil, Qatar, Sweden, and Germany) [5]. When a review of the inclusion of environmental sustainability in dietary guidance was published in 2022 [3], 37 countries with guidance translatable into English mentioned environmental sustainability out of 83 total sets of FBDGs. Most of these countries are located in Europe and Central Asia or Latin America and the Caribbean [3].

“Flexitarian” dietary patterns have been defined as a potential strategy for consumers to reduce their animal food intake without removing it completely. Broadly, the term “flexitarian” describes dietary patterns with animal-source food intake somewhere between vegan or vegetarian diets and omnivorous diets. This term does not have a specific definition or quantifiable properties and, therefore, can apply to dietary patterns with a variety of animal intakes. Because there is no formal or even colloquial definition, “flexitarian” patterns are primarily self-defined. There are several terms similar to “flexitarian” also utilized in the nutrition science literature, including “semi-vegetarian,” “flexible vegetarian,” “meat-reducers,” and “reducetarian,” among others [6,7,8].

Despite the interest in plant-based eating that still includes some animal-source foods [9], relatively little research has been dedicated to defining flexitarian dietary patterns, especially patterns that include lower amounts of animal-sourced foods but still meet nutrient needs for average consumers. The term “flexitarian” was mentioned in the popular press in the early 2000s [10] but did not become a mainstream term until 2010 when registered dietitian Dawn Jackson Blatner published The Flexitarian Diet: The Most Vegetarian Way to Lose Weight, Be Healthier, Prevent Disease, and Add Years to Your Life [11]. Blatner describes the diet as mostly plant-based food but with the flexibility to include meat occasionally [11]. She also describes flexitarian eating as a “casual vegetarian” diet, identifying three “levels” of adherence [11]. Beginner flexitarians have two meatless days per week, advanced flexitarians limit meat intake to three or four days a week, and expert flexitarians avoid meat on five out of seven days per week. An early use of the term “flexitarian” in the peer-reviewed literature mentions Blatner’s role in identifying this unique dietary pattern and the importance of differentiating between individuals who eat meat frequently and those who eat meat occasionally, noting that prior studies have largely ignored the flexitarian subgroup and/or subsumed them into a larger group with omnivores [12].

Our hypothesis was that, to date, there is not a commonly used parameter specifying the amount of animal foods in “flexitarian” diets. Furthermore, we hypothesized that FBDGs do not explicitly use the terms “flexitarian,” “semi-vegetarian,” or “reducetarian” to describe recommended diets. The objectives of this study were twofold:

- Identify the most used definitions of “flexitarian” dietary patterns in the scientific literature and develop draft quantitative parameters;

- Assess dietary guidance available in English to see how well guidance from the food-based dietary guidance (FBDG) of different countries aligns with most common definitions of “flexitarian” in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining Flexitarian Diets

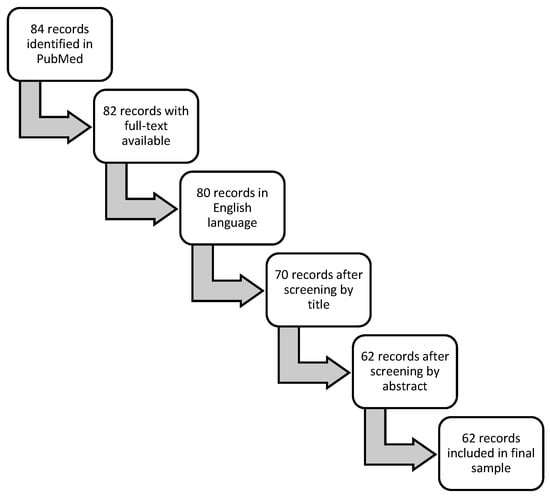

A PubMed search in September 2023 of the term “flexitarian” yielded 84 manuscripts, and n = 62 of these manuscripts were included in the final review (Supplementary Materials). Only full-text articles available in the English language that were relevant to this topic as determined by title and abstract review were included. Figure 1 provides an overview of the search structure. This search protocol was not registered.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of records selection process for articles defining “flexitarian” among the scientific literature published in PubMed.

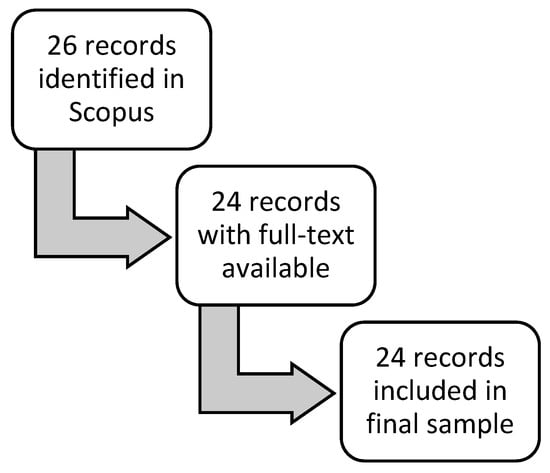

A second search was conducted with Scopus in June 2025 to find additional literature that may have been published prior to September 2023 but was not captured in the original PubMed search. The full search strategy can be found in the Supplementary Materials. Figure 2 provides a graphical illustration of this secondary literature search.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of records selection process for articles defining “flexitarian” among the scientific literature published in Scopus.

2.2. Finding FBDGs to Include

The FAO maintains a webpage with links to FBDGs available in 100 countries [13]. This webpage was utilized to identify countries with dietary guidance available in English, a strategy that has been employed in previous research efforts [3]. A copy of each set of FBDG listed on the webpage that was available in English was downloaded and documented.

Data was extracted from each file, including country name, year of dietary guidance, sex/age recommendations for each dietary pattern including approximately 2000 kcal, and servings of each of nine food groups (vegetables, fruits, grains, dairy, meat and eggs, seafood/fish, legumes/pulses, nuts/seeds, and oils/fats) within a recommended dietary pattern closest to 2000 kcal. For instance, Afghani dietary guidance had patterns at 1300, 2200, and 2800 kcal, so data on the 2200 kcal pattern was extracted for this analysis [14]. One member of the research team conducted the initial data extraction, and a second re-searcher reviewed each entry for accuracy and completion. Any disputes between the first and second researchers were resolved after review by a third researcher.

With each set of FBDGs that recommended multiple eating patterns or styles, the most common or “base” pattern was used in this analysis. For example, the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020 DGA) included Healthy U.S.-Style, Healthy Vegetarian, and Healthy Mediterranean Dietary Patterns [15], so this analysis used the Healthy U.S.-Style Dietary Pattern for comparisons. Guidelines germane to flexitarian-style diets were noted (e.g., eat small amounts of animal foods, mention vegetarian diets as an option, replace meat with alternates), as was flexibility within the guidelines to follow a flexitarian dietary pattern as defined by the literature identified in the PubMed and Scopus searches. Two sets of guidelines provided recommendations for an entire geographic region rather than a specific country (e.g., the Nordic Nutrition guidance [16] and the Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living [17]). Although these sets of guidance were included in this analysis, throughout this manuscript, FBDGs are described as “country-specific.”

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

Data extracted from the n = 86 final studies include the term(s) used within them for dietary patterns with fewer animal products and the definition of those dietary patterns (Table 1). The most common two terms used by these studies for diets with few animal foods were “flexitarian (n = 58) or “semi-vegetarian” (n = 47), with fewer studies using the term “meat-reducers” (n = 9), and only one study each using the terms “reducetarian,” “flexible vegetarian,” “low meat-eater,” “demi-vegetarian,” “casual vegetarians,” “vegivores,” or “flexi-semi-vegetarian.”

Table 1.

Descriptions and terminology used for dietary patterns containing small amounts of animal foods in the scientific literature by geographical location.

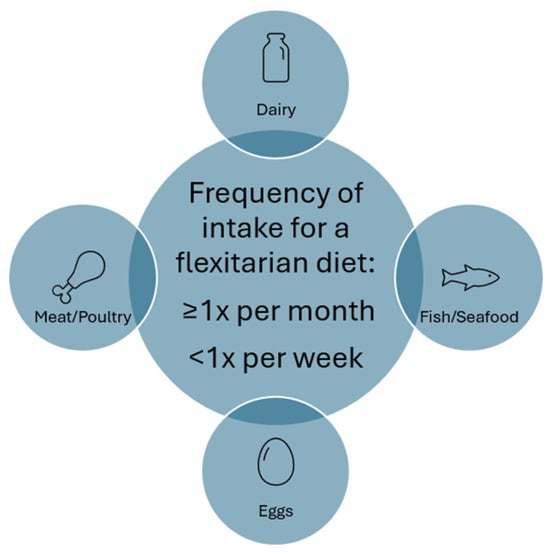

Synthesizing the descriptions and definitions of dietary patterns lower in animal products (that did not remove animal food categories completely), there were few specific quantitative descriptions provided. Part of the benefit of a “flexitarian” diet over a strict vegetarian or vegan diet comes from its inherent flexibility. To provide structure for analyzing global FBDGs, the below four items summarize the limits on animal foods mentioned by some of the studies and will be used to identify FBDG that can accommodate a flexitarian diet:

- Consume dairy products at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume eggs at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume meat and/or poultry products at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume fish and/or seafood at least once per month but less than once per week.

Figure 3 provides a graphical illustration of this summary definition.

Figure 3.

Summary of intake frequency of animal foods within a flexitarian diet as defined by literature review in PubMed and Scopus.

3.2. Flexitarian Diets in FBDGs

A total of n = 52 FBDGs contained guidance in English and were downloaded for data extraction. Some FBDGs did not contain quantitative guidance or recommendations for specific dietary patterns. These guidelines, which included FBDG from Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Brazil, Canada, Dominica, Guyana, Namibia, Nigeria, Saint Lucia, and Thailand, were removed from consideration. Cambodia’s guidelines [99] were developed specifically for school-aged children and China’s most recent 2022 guidelines were not available for download, so these FBDGs were also excluded.

Fiji published country-specific guidelines in 2013 [100], and new guidelines were published for the Pacific Community in 2018 [17]. The Pacific Community encompasses 27 member countries and territories, including American Samoa, Australia, Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, France, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Pitcairn Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, United Kingdom, U.S., Vanuatu, and Wallis and Futuna as well as Fiji. Both sets of these guidelines were included, as it was not clear whether the Pacific Community guidelines was intended to replace the 2013 guidelines specific to Fiji. The total number of FBDGs included in this analysis was n = 42.

None of the FBDGs explicitly named a “flexitarian” eating style; however, dietary guidance from Sri Lanka described a “semi-vegetarian” dietary pattern as part of a list of “Types of Vegetarian Diets” [101]. This pattern was defined as a “mainly plant based diet” that “may include fish/egg/poultry, milk and milk products occasionally or in small quantities” [101]. Several other FBDGs explicitly mentioned vegetarian patterns (n = 12) or reducing meat or animal food and/or choosing meat/dairy alternatives (n = 14). Spanish guidelines from 2022 recommended limiting meat consumption to “a maximum of 3 servings of meat per week” [102]. German guidelines (2024) also recommended limiting intake of meat and sausage and emphasized choosing a diet that is plant-based and animal-based, indicating the ability to follow a flexitarian dietary pattern within their recommendations [103]. Sri Lankan guidelines recommended of protein sources come from plants and of protein sources come from animals [101].

FBDGs (n = 28) from many countries indicated the possibility to follow recommendations within flexitarian definitions with some animal products. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s guidelines [104] recommended that dairy foods be consumed daily and do not provide a quantitative recommendation for egg consumption. These guidelines recommended that meat and substitutes (cooked lean meat, poultry, fish, egg, dry beans, peanut butter) be consumed daily, meaning that beans or legumes could be consumed in lieu of meat and fish. Therefore, it would be feasible to follow a flexitarian dietary pattern following these guidelines by consuming meat, poultry, fish, and seafood less than once per week but more than once per month even though not explicitly recommended. However, a flexitarian approach could not be adopted with dairy foods within the parameters of these guidelines [104]. Flexitarian diets may also be possible with a similar approach using guidance from Afghanistan [14], Australia [105], Belgium [106], Bulgaria [107], Barbados [108], England [109], Fiji [100], Georgia [110], Ghana [111], Ireland [112], Israel [113], Oman [114], Japan [115], Kenya [116], Lebanon [117], the Netherlands [118], New Zealand [119], Nordic countries [16], Norway [120], the Pacific Community [17], the Philippines [121], Qatar [122], Sierra Leone [123], Sweden [124], and Zambia [125]. Diet pattern examples in India’s 2024 guidance [126] focus on vegetarian diets, which meet the definition for flexitarian diets with respect to meat/poultry, fish/seafood, and eggs.

Reducing animal-based food intake was not feasible with other sets of FBDG. Albanian guidance recommended daily consumption of one portion of meat or fish as well as an egg or a portion of cheese in addition to three portions of other dairy foods (milk or yogurt) daily [127]. Similarly, a flexitarian diet would not be possible following guidance from Bangladesh [128] or Ethiopia [129], as both countries recommended daily consumption of dairy as well as poultry, meat, fish, or eggs.

Following a flexitarian dietary pattern may be feasible within the parameters of FBDGs from Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, South Africa, Seychelles, and Belize, but would require reducing intake of one or two animal-based foods and consuming more of other animal-based foods. Jamaica recommended daily intake from an animal food source [130], as did guidance from Saint Kitts and Nevis [131] and St. Vincent and the Grenadines [132]. These guidelines grouped all animal foods (dairy, eggs, meat, and fish) into a single category and recommended consuming 4–8 daily servings from this category. South Africa’s Food-Based Dietary Guidelines [133] also stated that “fish, chicken, lean meat and eggs can be eaten daily” but established weekly limits on each of these categories (no more than 560 g red meat, 3–4 eggs, or 2–3 portions of fish). Some countries such as the Seychelles [134] did not have quantitative recommendations for eggs or meat but recommended three daily servings of dairy and five weekly servings of fish. It would be similarly difficult to follow a flexitarian diet using recommendations from Belize [135], which recommended seven small daily portions of meat, eggs, or seafood/fish.

An overview of the dietary guidance reviewed, and a summary of their quantitative animal food recommendations, can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recommendations for servings of animal-source foods in global food-based dietary guidance (all guidance is provided in daily recommended amounts and applicable to the general adult population ages 19+ unless otherwise specified).

4. Discussion

Use of the term “semi-vegetarian” in the literature nearly as frequently as the term “flexitarian” as well as its use in Sri Lankan FBDG indicates that there may be broader acceptance of that term in the scientific literature than “flexitarian.” However, there is still little known or understood about the vegetarian and vegan population, much less how much of the population chooses to define their diets as lower in animal foods as opposed to being strict vegetarians or vegans [138]. Consumers may sometimes or often choose vegetarian meals without defining their dietary pattern in a specific way. Choosing to reduce meat or other animal foods on one day of the week as with “Meatless Mondays” [139] and similar efforts [25] does not meet the definitions used in this analysis for a flexitarian diet but, at least for U.S. consumers, might still decrease meat intake from estimated intake of 104 g/day based on previous analyses from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [140].

Some version of a flexitarian dietary pattern reduced in meat or poultry foods aligns with dietary guidance in several countries; however, few countries have guidance that allows for a flexitarian dietary pattern with limited dairy intake. Many countries recommend daily intake of dairy foods [141]. Some countries (Barbados, Belize, Fiji, Ghana, Jamaica, Pacific Community, Saint Kitts and Nevis, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and Sierra Leone) in this study recommend consuming dairy foods as part of a broader “animal foods” group including meat, eggs, poultry, and sometimes fish and do not include a specific “dairy foods” group. Each of these countries still recommends daily intake of the animal foods group. England’s Eatwell Guide includes a section of dairy and alternatives (milk, cheese, yogurt, and soya drink) but does not specify that these foods need to be consumed with a specific frequency [109].

Notably, the dairy groups of some countries do also include some plant-based alternatives that provide similar nutrients to milk, cheese, yogurt, and other nutrient-dense dairy foods. Australia and Oman recommend fortified plant-based drinks (soy, rice, oat), Lebanon recommends calcium-fortified soy milk or orange juice, and New Zealand and the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations list fortified plant-based milk alternatives like soy, rice, oat, and nut milk as nutritional equivalents for dairy foods in the diet. Fiji and Israel note soy milk that is unsweetened and, in the case of Israel’s guidelines, free of additives, can be an alternative beverage [100,113]. Qatar includes fortified soy and almond drinks as dairy alternatives, England lists unsweetened and fortified soy milk as an option, and the U.S. is unique in listing both fortified soy milk and soy yogurt as part of its dairy group [15,109,122]. Other countries include food sources of calcium and vitamin D as dairy alternatives instead of beverages. Georgia’s guidelines recommend that people who cannot drink milk choose to eat more dark green vegetables and nutrient-dense grains while Lebanon recommends fortified cereals, and Qatar lists chickpeas as alternate sources of calcium and vitamin D. Sweden recommends sardines as well as plant-based alternative beverages, nuts, and leafy greens as options to provide some of the nutrients found in dairy foods.

Limiting intake of red meat, poultry, and sometimes eggs to a certain number of servings per week was a much more frequent recommendation in the sets of dietary guidance analyzed. Reducing intake of one or both foods may be a more acceptable entry to flexitarian dietary patterns than reducing dairy foods. Germany, Bulgaria, Israel, Sweden, the Netherlands, Norway, Qatar, Spain, England, and South Africa provide quantitative limits for red meat consumption in their guidelines, amounts ranging from <70 g/day of red meat (England) to <350 g of meat per week (Nordic recommendations) to South Africa’s <560 g per week or <90 g per day of red meat. The U.S. recommends 26 ounce-equivalents (oz-eq) of meats, poultry, and eggs weekly in the Healthy U.S.-Style Dietary Pattern, which when divided into 5 to 6.5 oz-eq for daily consumption, amounts to eating meat or poultry about four times per week [15]. India recommends consuming fewer than three eggs per week, Bulgaria recommends up to three servings per week of meat and eggs, and Spain recommends two to four eggs per week. In contrast, Belgium recommends choosing eggs, legumes, fish, or poultry as substitutes for red meat, and Kenyan guidelines suggest that consumers aim to eat meat, eggs, seafood, and fish at least twice per week. Some guidelines (Zambia and Kenya) have animal foods groups that include insects [116,125] and/or caterpillars [125], which were widely discussed as potential options for less environmentally impactful sources of protein in the late 2010s [142,143]. Few locations frame recommendations for animal-source food in terms of minimum intake. A few exceptions include Kenyan guidance that recommends eating “lean meat, fish and seafood, poultry, insects or eggs at least twice a week” and the Seychelles guidance that recommends eating fish “at least 5 days” per week [116,134].

Several countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, England, Germany, Israel, Lebanon, the Netherlands, Nordic, Norway, Oman, Qatar, Seychelles, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the U.S., and Zambia) explicitly recommend eating one or more servings of fish on a weekly basis. Some of these countries (Sweden, Nordic, Norway, Lebanon, England, Zambia) further specify that at least one weekly serving of fish should come from an oily/fatty fish like salmon or herring. There could be multiple reasons for the limits and recommendations on meat, eggs, and fish/seafood intake, depending on the country and regional context. Newer guidelines, such as Zambia’s guidance from 2021, reference the Global Burden of Disease study as presented in the EAT-Lancet report [144]. This report proposes guidance for diets that support both human and planetary health with recommendations intended to be flexible for different cultural traditions and food availability and accessibility. The 2019 EAT-Lancet report proposed global dietary recommendations include reducing animal food intake for environmental reasons, listing ranges for protein sources that start at 0 (zero) for beef and lamb, pork, poultry, eggs, fish, and most legumes as well [144].

5. Limitations

FBDGs may have been updated in some countries since the writing of this manuscript. An initial list of countries and their guidance was gathered in spring 2024. In March 2025, a search of all guidelines published prior to 2020 was conducted to ensure no newer guidance was missed. India and Oman’s 2024 guidelines were among those collected in the more recent search. In addition, it was noted that English language versions of all FBDGs were not readily available for download online, including guidance from Malaysia and China. Turkey was scheduled to have new guidance published in 2014 per the FAO WHO website, but a new link has not been provided, so the 2006 version was used for this analysis.

In addition, it was not always clear how some guidance may have been translated to the English language. Some of the subtleties of recommendations may have been lost in the technical translation process. For instance, Albanian guidance for adults recommends a portion of meat, fish, or eggs be consumed daily. However, earlier in the document, meat is described as part of a food group that also includes cooked peas, peanut butter, kidney beans, and nuts. It is not clear whether the recommendation for adults to consume meat, eggs, and fish could also incorporate these vegetarian protein sources [127]. This analysis may have missed subtleties in recommendations from different sets of FBDGs, too, as it is not always clear how the guidance is intended to be applied. Food group recommendations can be reported in a summary table, separate tables, or simply mentioned in the text, and it is not always clear which guidance should take precedent when there are slight differences among them.

Because information on specific dietary parameters (e.g., number of servings of specific animal-source foods) and recommendations often required perusal of entire FBDG reports, it was not possible to utilize FBDGs unavailable in English in this analysis due to the researchers’ lack of fluency in other languages. This necessarily limits the interpretation of the results as they are not entirely representative of all countries that release FBDGs. According to the FAO, approximately 100 countries have FBDGs, and a previous analysis found FBDG for 90 countries [13,145]; therefore, this analysis with only 42 countries represents < 50% of available FBDGs.

As noted earlier, some guidance does not use portions or food groups, and these FBDGs, including those from Canada (2019) and Brazil (2015), were not included in this analysis. Canada’s 2019 guidance largely does not include portions or food groups in their recommendations [146] with the exceptions of vegetables and fruits, protein foods, and whole-grain foods [147]. While not included in this analysis, as a working link was not available on the FAO webpage, this approach to dietary guidance that does not include specific servings and recommendations was also utilized by Brazil in 2015 [148].

The definitions used to establish the parameters of flexitarian diets for this study may be more prescriptive than the term is meant to convey. A 2021 review of flexitarian diet studies noted that variable definitions are inherent to the concept of flexitarianism [46]. A search of only two databases (PubMed and Scopus) for articles that include the term “flexitarian” will have missed journals not indexed in those databases as well as articles that address reduced meat, fish, or dairy diets that, in effect, also discuss flexitarian eating patterns. Finally, the search protocols were not pre-registered, which could have introduced additional bias into the literature search, further limiting the applicability of these findings.

6. Conclusions

Following a flexitarian dietary pattern in terms of reducing or limiting red meat is feasible and even implicitly recommended by the official dietary guidance of several countries. However, only one country (Sri Lanka) refers to this reduced animal product diet as “semi-vegetarian,” and no countries utilize the term “flexitarian” in their guidance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17142369/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—J.M.H.; Data curation—J.M.H., K.R. and A.J.S.; Formal analysis—J.M.H. and K.R.; Methodology—J.M.H.; Project Administration—J.M.H. and A.J.S.; Resources—K.R.; Writing—original draft—J.M.H. and A.J.S.; Writing—review and editing—J.M.H., K.R. and A.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by USDA Agricultural Research Service project grant #3062-10700-003-000D.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kyra Jessen, Kylie Swanson, and Grant Dahly, who compiled and assisted in the literature review and in the analysis of global FBDGs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020 DGA); FBDG (food-based dietary guidance); FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization); IFIC (International Food Information Council); UN (United Nations).

References

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Food Information Council. 2024 Food and Health Survey; International Food Information Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- James-Martin, G.; Baird, D.L.; Hendrie, G.A.; Bogard, J.; Anastasiou, K.; Brooker, P.G.; Wiggins, B.; Williams, G.; Herrero, M.; Lawrence, M.; et al. Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: A global review. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e977–e986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity: Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.G.; Garnett, T. Plates, Pyramids, and Planets; Food Climate Research Network: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, E.J. Flexitarian diets and health: A review of the evidence-based literature. Front. Nutr. 2017, 3, 231850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.A.; White, S.K. Young adults’ experiences with flexitarianism: The 4Cs. Appetite 2021, 160, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.C.; Alchin, C.; Anastasiou, K.; Hendrie, G.; Mellish, S.; Litchfield, C. Exploring the Intersection Between Diet and Self-Identity: A Cross-Sectional Study With Australian Adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, H.; Larpin, C.; de Mestral, C.; Guessous, I.; Reny, J.-L.; Stringhini, S. Vegetarian, pescatarian and flexitarian diets: Sociodemographic determinants and association with cardiovascular risk factors in a Swiss urban population. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, J.K. Fakin ‘bacon’ phony bologna and sham ham: Beef consumption has declined 15 percent over the past 20 years, according to the USDA. What’s making up to this decline? Maybe it’s and imposter. Food Process. 2005, 66, S22. [Google Scholar]

- Blatner, D.J. The Flexitarian Diet: The Mostly Vegetarian Way to Lose Weight, Be Healthier, Prevent Disease, and Add Years to Your Life; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USAC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forestell, C.A.; Spaeth, A.M.; Kane, S.A. To eat or not to eat red meat. A closer look at the relationship between restrained eating and vegetarianism in college females. Appetite 2012, 58, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/nutrition-education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Afghans; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; Ministry of Public Health (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan; Ministry of Education (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan, 2016.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Blomhoff, R.; Andersen, R.; Arnesen, E.K.; Christensen, J.J.; Eneroth, H.; Erkkola, M.; Gudanaviciene, I.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Høyer-Lund, A.; Lemming, E.W.; et al. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Public Health Division of the Pacific Community. Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living: A Handbook for Health Professionals and Educators; Pacific Community: Nouméa, New Caledonia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.; Quinton, S. The inter-relationship between diet, selflessness, and disordered eating in Australian women. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.J.; Oldmeadow, C.; Mishra, G.D.; Garg, M.L. Plant-based dietary patterns are associated with lower body weight, BMI and waist circumference in older Australian women. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Ding, D.; Gale, J.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Banks, E.; Bauman, A.E. Vegetarian diet and all-cause mortality: Evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort—The 45 and Up Study. Prev. Med. 2017, 97, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooker, P.G.; Hendrie, G.A.; Anastasiou, K.; Woodhouse, R.; Pham, T.; Colgrave, M.L. Marketing strategies used for alternative protein products sold in Australian supermarkets in 2014, 2017, and 2021. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1087194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtain, F.; Grafenauer, S. Plant-based meat substitutes in the flexitarian age: An audit of products on supermarket shelves. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakin, B.C.; Ching, A.E.; Teperman, E.; Klebl, C.; Moshel, M.; Bastian, B. Prescribing vegetarian or flexitarian diets leads to sustained reduction in meat intake. Appetite 2021, 164, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, S.; Powers, J.; Brown, W.J. How does the health and well-being of young Australian vegetarian and semi-vegetarian women compare with non-vegetarians? Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. From meatless Mondays to meatless Sundays: Motivations for meat reduction among vegetarians and semi-vegetarians who mildly or significantly reduce their meat intake. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groeve, B.; Hudders, L.; Bleys, B. Moral rebels and dietary deviants: How moral minority stereotypes predict the social attractiveness of veg*ns. Appetite 2021, 164, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, J.B.; Silva, Y.d.O.; Santos, S.S.; Dionísio, A.P.; de Sousa, P.H.M.; Garruti, D.d.S. Plant-based gastronomic products based on freeze-dried cashew fiber. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, U.M.; Gibson, R.S. Dietary intakes of adolescent females consuming vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous diets. J. Adolesc. Health 1996, 18, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švarc, P.L.; Jensen, M.B.; Langwagen, M.; Poulsen, A.; Trolle, E.; Jakobsen, J. Nutrient content in plant-based protein products intended for food composition databases. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 106, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Reay, D.S.; Higgins, P. Potential of Meat Substitutes for Climate Change Mitigation and Improved Human Health in High-Income Markets. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapila, A.; Michel, F.; Jouppila, K.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Piironen, V. Millennials’ Consumption of and Attitudes toward Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives by Consumer Segment in Finland. Foods 2022, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Päivärinta, E.; Itkonen, S.T.; Pellinen, T.; Lehtovirta, M.; Erkkola, M.; Pajari, A.-M. Replacing animal-based proteins with plant-based proteins changes the composition of a whole Nordic diet—A randomised clinical trial in healthy Finnish adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torfadottir, J.E.; Aspelund, T. Flexitarian diet to the rescue. Laeknabladid 2019, 105, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, N.; Huneau, J.-F.; Mariotti, F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Eve, A.; Granda, P.; Legay, G.; Cuvelier, G.; Delarue, J. Consumer acceptance and sensory drivers of liking for high plant protein snacks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3983–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousset, C.; Gregorio, E.; Marais, B.; Rusalen, A.; Chriki, S.; Hocquette, J.-F.; Ellies-Oury, M.-P. Perception of cultured “meat” by French consumers according to their diet. Livest. Sci. 2022, 260, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessler-Kaufmann, J.B.; Meule, A.; Holzapfel, C.; Brandl, B.; Greetfeld, M.; Skurk, T.; Schlegl, S.; Hauner, H.; Voderholzer, U. Orthorexic tendencies moderate the relationship between semi-vegetarianism and depressive symptoms. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, A.; Mueller, M.; Schneider, I.; Hahn, A. Application of a modified healthy eating index (HEI-Flex) to compare the diet quality of flexitarians, vegans and omnivores in Germany. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seel, W.; Reiners, S.; Kipp, K.; Simon, M.C.; Dawczynski, C. Role of Dietary Fiber and Energy Intake on Gut Microbiome in Vegans, Vegetarians, and Flexitarians in Comparison to Omnivores-Insights from the Nutritional Evaluation (NuEva) Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, M.A. What makes a plant-based diet? a review of current concepts and proposal for a standardized plant-based dietary intervention checklist. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 76, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bánáti, D. Flexitarianism—The sustainable food consumption? Élelmiszervizsgálati Közlemények 2022, 68, 4075–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, J.; Vasas, D.; Ahmed, M. Comparative Analysis of Flexitarian, Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: A Review. Élelmiszervizsgálati Közlemények 2023, 69, 4382–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.A.; Meyer, R.; Donovan, S.M.; Goulet, O.; Haines, J.; Kok, F.J.; Van’t Veer, P. Perspective: Striking a Balance between Planetary and Human Health-Is There a Path Forward? Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagevos, H. Finding flexitarians: Current studies on meat eaters and meat reducers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: A review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestell, C.A. Flexitarian Diet and Weight Control: Healthy or Risky Eating Behavior? Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukid, F.; Rosell, C.M.; Rosene, S.; Bover-Cid, S.; Castellari, M. Non-animal proteins as cutting-edge ingredients to reformulate animal-free foodstuffs: Present status and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6390–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, F. Meat as a Pharmakon: An Exploration of the Biosocial Complexities of Meat Consumption. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 87, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, M.; Swanepoel, A.C. The effect of plant-based diets on thrombotic risk factors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2021, 131, 16123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Styrbæk, K. Design and ‘umamification’ of vegetable dishes for sustainable eating. Int. J. Food Des. 2020, 5, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiel, U.; Landau, N.; Fuhrer, A.E.; Shalem, T.; Goldman, M. The Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatricians in Israel Towards Vegetarianism. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, P.; Rossano, R.; Larocca, M.; Trotta, V.; Mennella, I.; Vitaglione, P.; Ettorre, M.; Graverini, A.; De Santis, A.; Di Monte, E.; et al. Anti-inflammatory nutritional intervention in patients with relapsing-remitting and primary-progressive multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.; Marescotti, M.E.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A. Validation of the Dietarian Identity Questionnaire (DIQ): A case study in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliceri, D.; Spinelli, S.; Dinnella, C.; Prescott, J.; Monteleone, E. The influence of psychological traits, beliefs and taste responsiveness on implicit attitudes toward plant- and animal-based dishes among vegetarians, flexitarians and omnivores. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekema, R.; Tyszler, M.; van ‘t Veer, P.; Kok, F.J.; Martin, A.; Lluch, A.; Blonk, H.T.J. Future-proof and sustainable healthy diets based on current eating patterns in the Netherlands. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Meer, M.; Fischer, A.R.; Onwezen, M.C. Same strategies–different categories: An explorative card-sort study of plant-based proteins comparing omnivores, flexitarians, vegetarians and vegans. Appetite 2023, 180, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, B.; Jouppila, K.; Sandell, M.; Knaapila, A. No meat, lab meat, or half meat? Dutch and Finnish consumers’ attitudes toward meat substitutes, cultured meat, and hybrid meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 108, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaren, O.; Mackay, L.; Schofield, G.; Zinn, C. Novel Nutrition Profiling of New Zealanders’ Varied Eating Patterns. Nutrients 2017, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.A. Motivations, barriers, and strategies for meat reduction at different family lifecycle stages. Appetite 2020, 150, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, N.A.; Worthington, A.; Li, L.; Conner, T.S.; Bermingham, E.N.; Knowles, S.O.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Hannaford, R.; Braakhuis, A. Adherence and eating experiences differ between participants following a flexitarian diet including red meat or a vegetarian diet including plant-based meat alternatives: Findings from a 10-week randomised dietary intervention trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1174726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realini, C.E.; Driver, T.; Zhang, R.; Guenther, M.; Duff, S.; Craigie, C.R.; Saunders, C.; Farouk, M.M. Survey of New Zealand consumer attitudes to consumption of meat and meat alternatives. Meat Sci. 2023, 203, 109232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famodu, A.A.; Osilesi, O.; Makinde, Y.O.; Osonuga, O.A. Blood pressure and blood lipid levels among vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and non-vegetarian native Africans. Clin. Biochem. 1998, 31, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Bugge, A.B.; Morseth, M.S.; Pedersen, J.T.; Henjum, S. Dietary Habits and Self-Reported Health Measures Among Norwegian Adults Adhering to Plant-Based Diets. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 813482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwaśniewska, M.; Pikala, M.; Grygorczuk, O.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Stepaniak, U.; Pająk, A.; Kozakiewicz, K.; Nadrowski, P.; Zdrojewski, T.; Puch-Walczak, A.; et al. Dietary Antioxidants, Quality of Nutrition and Cardiovascular Characteristics among Omnivores, Flexitarians and Vegetarians in Poland-The Results of Multicenter National Representative Survey WOBASZ. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguerol, A.T.; Pagán, M.J.; García-Segovia, P.; Varela, P. Green or clean? Perception of clean label plant-based products by omnivorous, vegan, vegetarian and flexitarian consumers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spendrup, S.; Hovmalm, H.P. Consumer attitudes and beliefs towards plant-based food in different degrees of processing—The case of Sweden. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Dietary change scenarios and implications for environmental, nutrition, human health and economic dimensions of food sustainability. Nutrients 2019, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, C.F.; Tini, G.; Vassallo, I.; Godin, J.P.; Su, M.; Jia, W.; Beaumont, M.; Moco, S.; Martin, F.P. Vegan and Animal Meal Composition and Timing Influence Glucose and Lipid Related Postprandial Metabolic Profiles. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1800568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northstone, K.; Emmett, P.M. Dietary patterns of men in ALSPAC: Associations with socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics, nutrient intake and comparison with women’s dietary patterns. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capper, J. A sustainable future isn’t vegan, it’s flexitarian. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Buckland, N.J. Perceptions about meat reducers: Results from two UK studies exploring personality impressions and perceived group membership. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio-Mateas, M.A.; Bester, A.; Klimenko, N. Impact of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives on the Gut Microbiota of Consumers: A Real-World Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestell, C.A.; Nezlek, J.B. Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2018, 57, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, W.J.; McGrievy, M.E.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M. Dietary adherence and acceptability of five different diets, including vegan and vegetarian diets, for weight loss: The New DIETs study. Eat. Behav. 2015, 19, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Davidson, C.R.; Wilcox, S. Does the type of weight loss diet affect who participates in a behavioral weight loss intervention? A comparison of participants for a plant-based diet versus a standard diet trial. Appetite 2014, 73, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Wirth, M.D.; Shivappa, N.; Wingard, E.E.; Fayad, R.; Wilcox, S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Hébert, J.R. Randomization to plant-based dietary approaches leads to larger short-term improvements in Dietary Inflammatory Index scores and macronutrient intake compared with diets that contain meat. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotillard, A.; Cartier-Meheust, A.; Litwin, N.S.; Chaumont, S.; Saccareau, M.; Lejzerowicz, F.; Tap, J.; Koutnikova, H.; Lopez, D.G.; McDonald, D. A posteriori dietary patterns better explain variations of the gut microbiome than individual markers in the American Gut Project. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.C. Plant-Based Diets: A Primer for School Nurses. NASN Sch. Nurse 2021, 36, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Guinard, J.X. The flexitarian flip™: Testing the modalities of flavor as sensory strategies to accomplish the shift from meat-centered to vegetable-forward mixed dishes. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, R.; Forde, C.G. Unintended consequences: Nutritional impact and potential pitfalls of switching from animal-to plant-based foods. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.A.; Malone, T.; McFadden, B.R. Beverage milk consumption patterns in the United States: Who is substituting from dairy to plant-based beverages? J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11209–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Kurzer, A.; Cienfuegos, C.; Guinard, J.-X. Student consumer acceptance of plant-forward burrito bowls in which two-thirds of the meat has been replaced with legumes and vegetables: The Flexitarian Flip™ in university dining venues. Appetite 2018, 131, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L., III; Welland, D. Intake of 100% Fruit Juice Is Associated with Improved Diet Quality of Adults: NHANES 2013–2016 Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, F.L.; Lloren, J.I.C.; Haddad, E.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Knutsen, S.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Plasma, Urine, and Adipose Tissue Biomarkers of Dietary Intake Differ Between Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Diet Groups in the Adventist Health Study-2. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penniecook-Sawyers, J.A.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Beeson, L.; Knutsen, S.; Herring, P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of breast cancer in a low-risk population. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Sabaté, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian dietary patterns are associated with a lower risk of metabolic syndrome: The adventist health study 2. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Fraser, G. Vegetarian diets and the incidence of cancer in a low-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y.; Knutsen, S.F.; Knutsen, R.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Fan, J.; Beeson, W.L.; Sabate, J.; Hadley, D.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Penniecook, J.; et al. Are strict vegetarians protected against prostate cancer? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Butler, T.; Yan, R.; Fraser, G.E. Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Stewart, K.; Oda, K.; Batech, M.; Herring, R.P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkholder-Cooley, N.; Rajaram, S.; Haddad, E.; Fraser, G.E.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K. Comparison of polyphenol intakes according to distinct dietary patterns and food sources in the Adventist Health Study-2 cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Rowe, S.; Bonnell, C.; Dalton, P. Consumer acceptance of plant-forward recipes in a natural consumption setting. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiloglou, M.F.; Pascual, P.E.; Scuccimarra, E.A.; Plestina, R.; Mainardi, F.; Mak, T.N.; Ronga, F.; Drewnowski, A. Assessing the Quality of Simulated Food Patterns with Reduced Animal Protein Using Meal Data from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miassi, Y.E.; Dossa, F.K.; Zannou, O.; Akdemir, Ş.; Koca, I.; Galanakis, C.M.; Alamri, A.S. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting the choice of food diet in West Africa: A two-stage Heckman approach. Discov. Food 2022, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phnom Penh Minister of Health. Development of Recommended Dietary Allowance and Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for School-Aged Children in Cambodia; Phnom Penh Minister of Health: Phnom Penh, CambodiaT, 2017.

- National Food and Nutrition Centre. Food & Health Guidelines for Fiji; National Food and Nutrition Centre: Suva, FijiThi, 2013.

- Ministry of Health Nutrition Division. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Sri Lankans: Practitioner’s Handbook; Ministry of Health Nutrition Division: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2021.

- García, E.L.; Lesmes, I.B.; Perales, A.D.; Moreno-Arri-bas, V.; Portillo Baquedano, M.P.; Rivas Velasco, A.M.; Fresán Salvo, U.; Tejedor Romero, L.; Ortega Porcel, F.B.; Aznar Laín, S.; et al. Report of the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) on sustainable dietary and physical activity recommendations for the Spanish population. Rev. Com. Científico AESAN 2022, 36, 11–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Dietary Society (DGE). Eat and Drink Well—Recommendations of the German Nutrition Society (DGE); German Dietary Society: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- General Directorate of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Saudis: The Healthy Food Palm; General Directorate of Nutrition: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2012.

- Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Providing the Scientific Evidence for Healthier Australian Diets; Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Superior Health Council. Dietary Guidelines for the Belgian Adult Population; Superior Health Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Center of Public Health Protection. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Adults in Bulgaria; National Center of Public Health Protection: Sofia, BulgariaT, 2006.

- Barbados Mnistry of Health. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Barbados; National Nutrition Centre, Ministry of Health Ladymeade Gardens: Bridgetown, Barbados, 2017.

- Public Health England. A Quick Guide to the Government’s Healthy Eating Recommendations; Office for Health Improvement and Disparities: London, UK, 2016.

- Public Health Department, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affaires, World Health Organization. Healthy Eating—The Main Key to Health (FBDG-for Georgia); Public Health Department, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affaires, World Health Organization: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2005.

- Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Ghana: National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—2023; University of Ghana School of Public Health: Accra, Ghana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Ireland—Department of Health. Healthy Food for Life—The Healthy Eating Guidelines 2015–2016; Healthy Ireland—Department of Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2015.

- The Israeli Ministry of Health, Nutrition Department. Nutritional Recommendations. 2019. Available online: https://efsharibari.health.gov.il/media/1906/nutritional-recommendations-2020.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- World Health Organization; Sultanate of Oman. The Omani Guide for Healthy Eating; Department of Nutrition, Ministry of Health Oman: Muscat, Oman, 2024.

- Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top; Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Tokyo, Japan, 2010.

- Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health. National Guidelines for Healthy Diets and Physical Activity; Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017.

- The American University of Beirut. Lebanon: Food-Based Dietary Guidelines; The Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences; American University of Beirut: Beirut, Lebanon, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Dutch Dietary Guidelines 2015; Health Council of The Netherlands: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020.

- National Council for Nutrition. The Norwegian Dietary Guidelines; Norwegian Directorate of Health: Oslo, Norway, 2012.

- Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (FNRI-DOST). Nutritional Guidelines for Filipinos (NGF); Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (FNRI-DOST): Manila, Philippines, 2012.

- The Supreme Council of Health-State of Qatar. Qatar Dietary Guidelines; The Supreme Council of Health-State of Qatar: Doha, Qatar, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Healthy Eating; Government of Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, German Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- National Food Agency. The Swedish Dietary Guidelines: Find Your Way to Eat Greener, Not Too Much and Be Active; National Food Agency: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Zambia Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Technical Recommendations; Ministry of Agriculture: Lusaka, Zambia, 2021.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—India. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/india/en/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Department of Public Health Tirana. Recommendations on Healthy Nutrition in Albania; Department of Public Health Tirana: Tirana, Albania, 2008.

- Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM). Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh; Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Federal Government of Ethiopia. Ethiopia: Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—2022; Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Federal Government of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022.

- Ministry of Health Jamaica. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Jamaica; Ministry of Health Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica, 2015.

- Health Promotion Unit-Ministry of Health, Social Service, Community Development, Culture and Gender Affairs. Food Based Dietary Guidelines—St. Kitts & Nevis; Ministry of Health, Social Services, Community Development, Culture and Gender Affairs: Basseterre, St. Kitts & Nevis, 2010.

- Ministry of health, Wellness and the Environment. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment: Kingstown, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, 2021.

- Department of Health; Nutrition Society of South Africa. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa; Department of Health: Pretoria, Gauteng; Nutrition Society of South Africa: Brits, Gauteng, 2013.

- Nutrition Unit of the Ministry of Health. The Seychelles Dietary Guidelines; Nutrition Unit of the Ministry of Health: Victoria, Seychelles, 2006.

- Ministry of Health-Belize. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Belize; Ministry of Health Belize: Belmopan, Belize, 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7cacbe3e-be9d-4b33-8153-62a07ff21206/content (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- National Institute of Nutrition, India. Dietary Guidelines for Indians; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Turkey. Dietary Guidelines for Turkey: Adequate and Balanced Nutrition; Hacettepe University Department of Nutrition and Dietetics: Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, S.; Guest, N.S.; Landry, M.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Pawlak, R.; Rozga, M. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns for Adults: A Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Neu, P.; Berg, P.; Harding, J.; McKenzie, S.; Ramsing, R. The origins and growth of the Meatless Monday movement. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1283239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Taillie, L.S.; Jaacks, L.M. How Americans eat red and processed meat: An analysis of the contribution of thirteen different food groups. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, J.M.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Slavin, J.L. Dairy foods: Current evidence of their effects on bone, cardiometabolic, cognitive, and digestive health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, A.M. Insect Protein: A Sustainable and Healthy Alternative to Animal Protein? J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiking, H.; de Boer, J. Protein and sustainability—The potential of insects. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Canada’s Dietary Guidelines; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Lavigne, S.E.; Lengyel, C. A new evolution of Canada’s Food Guide. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 53, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil, Secretariat of Health Care, Primary Health Care Department. Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population; Ministry of Health of Brazil: Brasília, Brazil; São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/dietary_guidelines_brazilian_population.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).